Abstract

Objective. To determine the extent and manner in which global health education is taught at US PharmD programs.

Methods. A pre-tested 40-question electronic survey instrument was developed and sent to each of the 127 accredited or candidate-status US doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs.

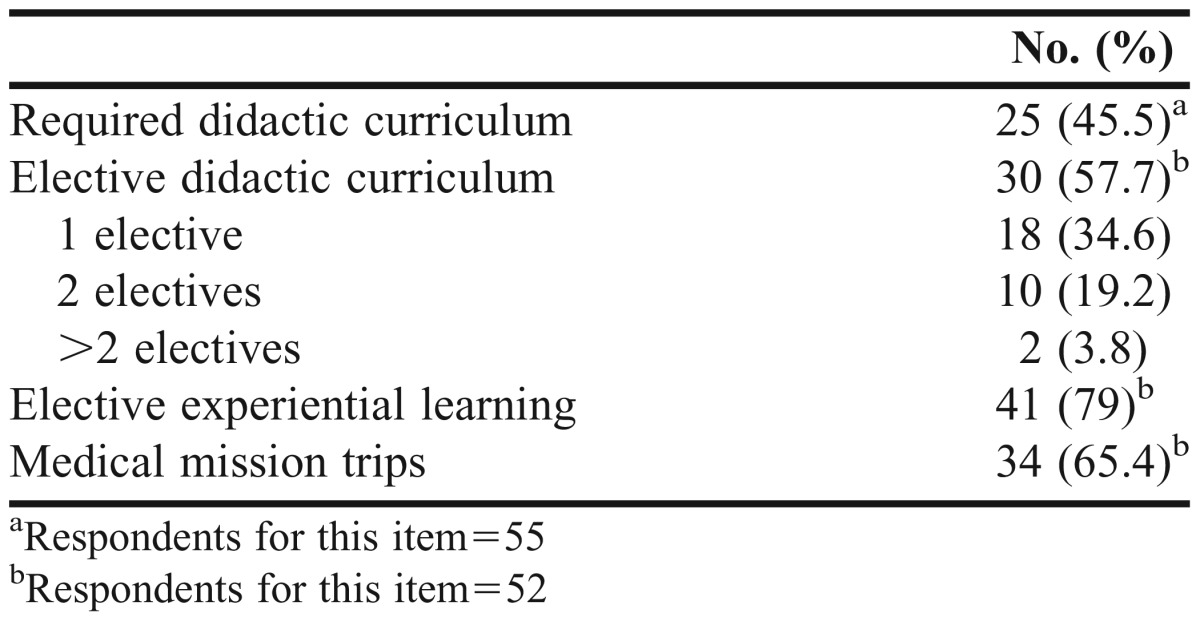

Results. Twenty-eight public and 27 private PharmD programs responded to the survey (43.3%). Twenty-five (45.5%) programs had integrated global health topics into their required didactic curriculum, and 30 of 52 programs (57.7%) offered at least one standalone global health elective course. Of the 52 programs that provided details regarding experiential education, 41 (78.8%) offered introductory and/or advanced pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs and/or APPEs) in global health, and 34 (65.4%) programs offered medical mission trips.

Conclusion. Doctor of pharmacy programs participating in global health education most commonly educate students on global health through experiential learning, while inclusion of required and elective coursework in global health was less common. To adequately prepare students for an increasingly global society, US PharmD programs should consider expanding global health education.

Keywords: Global health, pharmacy education, international, experiential education, global education

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, both national and international professional organizations have advocated for the advancement of the pharmacist’s role in global health. Global Health is defined as “an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people involved. Global health emphasizes transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions; involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration; and is a synthesis of population-based prevention with individual-level clinical care.”1 In the United States, the 2009-2010 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Research and Graduate Affairs Committee called for an expansion of student-pharmacist involvement in global health.2 Then, in 2012, with the goal of expanding the profession’s involvement in global health, AACP’s strategic plan called for an increase in professional student and faculty experiences on a local, national, and global scale.3 AACP and the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) have since developed special interest groups in global health, which may help to facilitate this call.4,5 Additionally, AACP holds membership in the Global Alliance for Pharmacy Education (GAPE), who in partnership with the Accreditation Council of Pharmacy Education (ACPE) is on a mission to advance the quality of pharmacy and pharmaceutical education worldwide.4 On an international scale, the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) is collaborating with the World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization on a Global Pharmacy Action Plan to: “expand the role of pharmacists in public health; allow for a global exchange and analysis of experiences; and, appropriately train pharmacists to assist with globalization of the profession.”6

There are many benefits for global health pharmacy education, and a number of PharmD programs in the United States are already engaged through elective didactic coursework and experiential education.7-10 Studies in the medical education field have shown that international experiential opportunities can improve a student’s clinical skills and knowledge of tropical diseases, increase student self-reported cultural competence, promote positive views on health care in developing countries among students, and increase the percentage of medical students that serve in a multicultural/underserved environment following graduation.11-13 Global education, particularly in the area of experiential learning, where students may train in a foreign country, can be used as a means to teach and assess cultural competency.14 Both the 2013 Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Outcomes and the 2016 ACPE draft standards integrate cultural sensitivity within their respective documents.15,16 Establishing global partnerships intended to expand global pharmacy educational opportunities may therefore help PharmD programs to better meet the CAPE Outcomes and ACPE standards in this area. Although not clearly stated in the CAPE or ACPE guidelines, advancement in global education is a priority across many other health disciplines and can fit within the context of Domains 3 (Approach to Practice and Care) and 4 (Personal and Professional Development), particularly in the areas of cultural sensitivity, professionalism, and self-awareness.17 This has been outlined in a recent publication by the AACP’s Global Pharmacy Education Special Interest Group (GPE-SIG) in which global and international experiences were linked to the CAPE 2013 outcomes, which may assist with adequately preparing all graduates for the changing demographics and globalization of the United States.18

Due to the paucity of data available detailing pharmacy education in the area of global health education, the purpose of this study was to assist schools and colleges of pharmacy in planning when initially considering integrating or expanding global health content into the PharmD curriculum. The primary objective of our survey-based study was to determine the extent to which global health education and experiences are taught in US schools and colleges of pharmacy; the secondary objective was to characterize the types of global health education and experiences.

METHODS

A 40-question electronic survey instrument was designed to collect information on didactic and experiential curricula in global health. Survey questions were categorized into the following sections: demographics; required didactic coursework in global health; elective coursework in global health; experiential education in global health or international settings; and, medical mission trips. If the PharmD program included either required didactic coursework or elective coursework, additional information was collected regarding the topics that are taught, the extent to which they are taught, and at what stage in the curriculum they are taught. The global health topics included within the survey were identified via the educational training modules posted on the Consortium of Universities for Global Health website and through a Medline search (1996-present) using the following key terms: pharmacy, pharmacy education, medical education, global health, and international health.19,20 Relevant articles were reviewed for descriptions of course/class content. Respondents were provided with a free textbox where they could address additional topics. The survey was validated on face and content by a faculty expert. The faculty member was asked to assess the clarity of question composition and whether the design of the survey instrument adequately addressed the study’s primary and secondary objectives. The survey instrument was revised based on the faculty member’s feedback.

An electronic hyperlink to the survey instrument was e-mailed to faculty members at 127 accredited and candidate-status PharmD programs in the United States, as identified via the ACPE website.21 Programs were excluded if they were located outside of the United States or if they had not been granted candidate or full accreditation status prior to the 2014-2015 academic year. Faculty members were identified through the AACP GPE-SIG member list (purchased from AACP). If a PharmD program did not have a SIG representative, pharmacy school websites were reviewed to identify contact information for faculty members having an interest in the following areas (in order of preference): global health; experiential education; pharmacy practice. Other staff and faculty positions were evaluated on a case-by-case basis. The survey instrument was distributed on July 22, 2014. To enhance the survey response rate, two reminder emails were sent: the first to the contacts on the original e-mail list at week two and the second to nonresponding PharmD programs at week four. The survey was open for eight weeks and closed on September 18, 2014. Common definitions used in the context of global/international health were provided. SurveyMonkey (Portland, OR) was used to collect responses.

In the event that multiple responses were received from a single program, responses were combined. Conflicting responses were resolved by the authors using predefined criteria based on the individual respondent’s position, with order of preference given to faculty members considered to best understand their program’s global health didactic curriculum and experiential learning program (in order): faculty member specializing in global health, department chair, experiential education director, pharmacy practice faculty member, assistant or associate dean, and dean. Conflicts with total class enrollment and/or full-time equivalent (FTE) status was averaged. When information was available, schools and colleges of pharmacy websites were used to resolve conflicts. Data were analyzed using Excel 2013 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and MYSTAT 12, version 12.02 (SYSTAT Software Inc., San Jose, CA). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the results, and the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to conduct subgroup analyses. Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the impact of several items (FTE, public vs private, having “global” in the mission statement, presence of a global health office, and years in existence) on the integration of global health into required coursework, presence of a global health elective course, global-health experiential learning, and availability of medical mission trips. This study was deemed exempt by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board in June 2014.

RESULTS

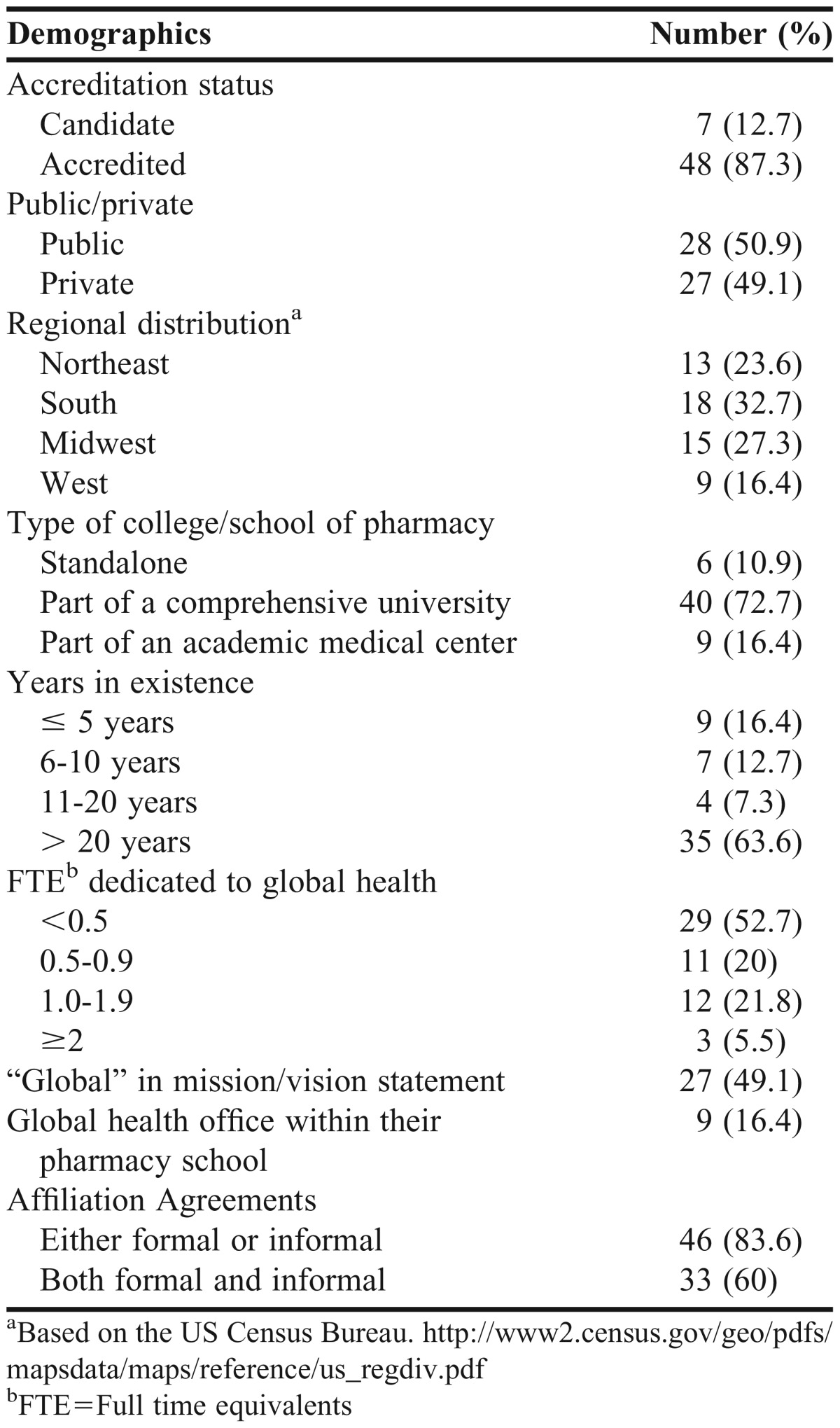

Fifty-five of 127 US PharmD programs responded to the survey (response rate=43.3%). Multiple responses were received from 15 programs, and these data were combined using the predefined criteria. The demographic characteristics of the responding programs are listed in Table 1. The distribution of responding public and private schools was similar, and PharmD programs from each of the geographic regions within the US were represented. Our distribution based on accreditation status, public/private, and regional distribution was similar to that of the academy and therefore generalizable. The Northeast region had the highest response rate (54%), followed by the Midwest (47%), West (39%), and South (38%). The mean±SD class size for the responding programs was 120.2±52.6 students.

Table 1.

Demographics of US PharmD Programs Participating in Global Health Survey (n=55)

The median number of faculty FTE dedicated to global health at responding programs was 0.4 (interquartile range [IQR], 0-1). Programs that did include “global” in their mission/vision statement were more likely to dedicate at least 1.0 FTE to global health (78.6% vs 42.9%, p<.05). Six programs with global health offices also integrated the term “global” into their mission/vision statement.

Of the 25 programs with a required curricula in global health, 14 offer both (required and elective) but only 22 of the 25 that offer it in the required curricula responded. (Table 2). In contrast, among the 30 programs that did not include global health topics in their required curriculum, 16 (53.3%) offered an elective course. Of the 30 programs that indicated they did not integrate global health into their program’s required didactic curriculum, only seven (23.3%) indicated having plans to do so in the future. The inclusion of global health in the required didactic curriculum was independent of FTEs, public/private status, years of existence, the integration of “global” in the program’s mission/vision statement, or the presence of a global health office within the school. However, there was a greater than 10% difference in the number of schools that dedicated at least 0.5 FTE to global health (57.7% vs 33.3%, p>.05) and those that had “global” in their mission/vision statement (51.7% vs 34.6%, p>.05).

Table 2.

Curriculum Structure of US Doctor of Pharmacy Programs Offering Global Health Education

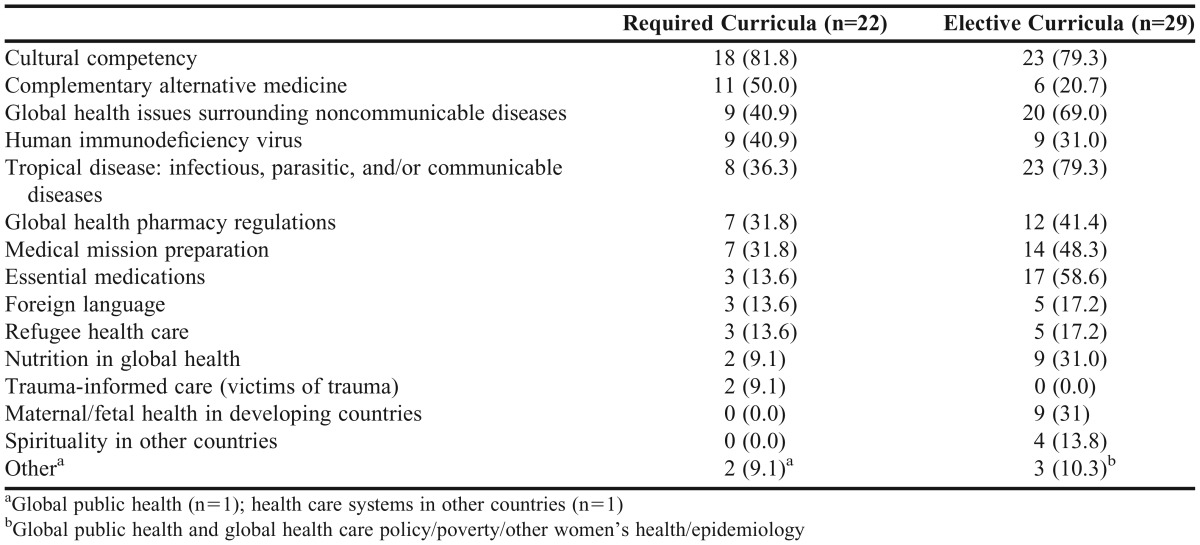

The time dedicated to global health topics ranged from 1 to 15 contact hours (mean±SD, 5.5±3.7 hours; median, 5 hours; IQR, 3.5-6 hours). Although global health topics were most frequently introduced to students as part of the required didactic curriculum during the first professional year (68.2%), the concentration of teaching global health topics were in the first (38.1%) and third (38.1%) professional (P1 and P3) years, while the second professional (P2) year was less frequently cited (23.8%). The global health topics taught as part of required didactic curricula are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Global Health Topics in Curricula Across US Doctor of Pharmacy Programs

Of the 22 programs that did not offer a standalone global health elective, only 5 (22.7%) indicated having plans to offer one in the future. Programs that dedicated at least 0.5 FTE to global health (75.0% vs 42.3%, p<.05) and those that had been in existence for at least 10 years (66.7% vs 37.5%, p<.05) were more likely to offer at least one elective in this area. The inclusion of a global health elective was independent of public/private status, the integration of “global” in the program’s mission/vision statement, and the presence of a global health office within the school. However, there was a greater than 10% difference in the number of schools having “global” within their mission or vision statement (65.4% vs 48.0%, p>.05) and those that had a global health office (66.7% vs 55.8%, p>.05).

Global health elective courses are taught most commonly as didactic coursework (60.4%), international fieldwork (23.3%), and local fieldwork (7%). Fieldwork is defined as practical application or research in an international or local setting.22 Only one responding program indicated that elective coursework was a “shared” activity with an international college or school. All programs that had more than one elective reportedly offer at least one of them in a didactic format, while seven (58.3%) offered the course as an international experience. The number of credit hours dedicated to global health topics within elective courses ranged from 1 to 11 hours (mean±SD), 3.1±2 hours; median, 2.5 hours; IQR, 2-3 hours). Global health elective courses were most commonly offered during the P2 and P3 years (86.7% each year), although 43.3% and 33.3% of programs offered these courses to P1 and fourth professional year (P4) students, respectively. Sixty-seven percent of global health elective courses were offered to 20 students or less. Table 3 summarizes the global health topics taught within elective coursework.

The availability of international or global health pharmacy practice experiences in experiential education among responding programs increased gradually from the P1 to the P3 year (12.2% to 29.3%), and then considerably in the P4 year (90.2%). All programs that indicated offering IPPEs (as non-core elective hours) and/or APPEs did so internationally, with 11 offering experiences in more than one setting (ie, local, national, and/or international). Of the 12 respondents that did not offer IPPEs or APPEs in global health, five (41.7%) indicated having plans to do so, mostly in the form of APPEs. The inclusion of international and/or global IPPEs and APPEs was not influenced by the number of FTEs dedicated to global health, the school’s public/private status, the integration of “global” in the program’s mission/vision statement, the presence of a global health office within the school, or the number of years the school has been in existence; however, there was a greater than 10% difference in the number of schools that dedicated at least 0.5 FTE to global health (88.0% vs 69.2%, p>.05), those that had “global” in their mission/vision statement (84.6% vs 72.0%, p>.05), and those having a global health office (88.9% vs 76.7%, p>.05). Although the difference was not significant, a greater number of programs that integrated global health into their required didactic or elective curriculum offered international or global experiential education opportunities (didactic: 95.2% vs 71%; elective: 86.7% vs 68.2%, p>.05). Of the 30 programs that offered elective coursework, only four (13.3%) did not offer experiential learning opportunities.

Medical mission trips were most commonly made available to students either every 12 months (50%) or every 6 months (31.4%) (Table 2). At responding schools, the number of students who participated in each medical mission trip ranged from 2 to 20 (mean±SD, 6.7±4.2 students; median, 5 students; IQR, 4-10 students). All of the 33 responding programs offered international medical mission trips, while fewer offered regional (21.2%) or national (18.2%) trips. The typical length of a medical mission trip ranged from fewer than 7 days to more than 14 days. Twenty-four of 32 (75.0%) programs offered course credit for students engaging in medical mission trips. The availability of medical mission trips at programs was not influenced by the number of FTEs (76.0% vs. 57.7%) dedicated to global health, the school’s public/private status, the integration of “global” in the program’s mission/vision statement, the presence of a global health office within the school, or the number of years the school has been in existence; however, there was a greater than 10% difference in the number of schools having “global” within their mission/vision statement (76.9% vs 56.0%, p>.05).

DISCUSSION

Published surveys on international and global education in pharmacy have predominately focused on the prevalence of affiliation agreements and the types of international and global experiences offered to students.8,23,24 Our survey expands on these studies by characterizing the integration of and extent of international and global health in the curricula of PharmD programs across the United States. Overall, our results indicate that global health education in US PharmD programs is not commonplace, particularly within required didactic coursework. That said, the majority of programs have integrated global health education within electives and experiential education at their schools, thereby reaching those students who are most interested in the topic.

Given the amount of content that must be taught within the PharmD curriculum, it can be difficult for some schools to dedicate time for global health education, particularly since neither the ACPE standards nor the CAPE educational outcomes directly mention global health in their recommendations.15,16 Therefore, it is not surprising that few schools integrate it (or dedicate time for it) into their required and elective curricula, or that there is significant variability in contact hours dedicated to this content within required curricula. However, schools that have been established for 10 or more years were more likely to offer an elective course, which may be in part because of their historical experience in global health, resources being dedicated to the area, and potentially interdisciplinary collaborations (which were not addressed in this survey). For those that do not, it may be due to the lack of limited resources, different priorities, or low interest in or urgency for developing global coursework. Global health may also be a focus of certain schools: 13 programs offered both required and elective didactic coursework, all of which offered IPPE and/or APPE experiences. Consideration should be given for how schools will prepare PharmD students for an increasingly global society. A global health elective offers a viable alternative for programs that are unable to establish global health into their required curriculum to the degree they desire. It may also serve as a means for thoughtfully preparing students who are planning to travel abroad for global health educational experiences. This survey and the AACP Global Pharmacy Education SIG’s report can assist schools and colleges with planning an initial or expanding their outcome-based global health curriculum. Content within didactic and elective areas should be carefully considered so as to allow for integration of and transition to experiential learning.

Our survey demonstrated that topics in the required curriculum focused on complementary and alternative medicine, cultural competency, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Table 3). Although these topics are global in nature, they are also prevalent in North America and other developed countries, and most are part of the ACPE Standards 2016, which explains why they may have been included.16 A recommended list of global health topics that should be taught in PharmD curricula does not exist, and variations in themes across programs may be specific to the host countries with which colleges and schools of pharmacy have partnerships and/or affiliation agreements.

An increase in the number of global and international programs across US schools of pharmacy was observed in our survey.23,24 Compared to the 2007 (response rate 67%) and 2010 (response rate 73%) AACP surveys, which indicated that 62% and 48% of schools, respectively, had formal affiliation agreements (unpublished data), our study revealed 73% of responding programs have such an agreement in place. This is not surprising given the high level of interest in international work in undergraduate training and an increase in study abroad programs. Agreements such as these can help facilitate international and global experiential learning.

This study demonstrated that global health is commonly integrated into experiential learning and medical mission trips. Since experiential learning is often interdisciplinary or interprofessional in nature, and global health is interdisciplinary in nature, it seems natural to teach students in the international and global setting.25 The CAPE guidelines (Guidance for Standards 2016) allow for international, elective APPE experiences, which along with an increase in affiliation agreements across US PharmD programs, may facilitate expansion of experiential education as an avenue to educate interested students. However, the availability of these experiences and the cost that is associated with them will likely limit the number of students who are able to engage in such an experience. For those students fortunate enough to do so, didactic coursework should be made available to help prepare them for the patients they will serve.

Local experiences with refugees, immigrants, and Native Americans could provide areas for increased engagement within global health and could include a larger number of students by minimizing cost and eliminating some of the complexities usually associated with international travel.26,27 Topics such as ethics, cultural competency, dietary habits, traditional medicines, viewpoints on Western medicine, language concerns, at risk diseases (due to their country of origin) can provide students with similar experiences. Traditionally, engagement in medical mission trip work has been viewed as a “service” activity. However, our survey data indicate that medical mission trips are offered for course credit at the majority of schools. Future research should investigate how medical mission trips are structured and how to best allocate course credit to students.

Our study indicated that schools that dedicate at least 0.5 FTEs to global health more commonly offer elective coursework in global health. And, although the difference was not significant, schools that dedicate the above FTEs to global health also offer required didactic coursework at a higher rate. Our study also revealed that schools that integrate the term “global” into their mission or vision offered required and elective coursework, international and global experiential education, and medical mission trips at a higher rate than those schools that did not, although the difference was not significant. Because schools integrating the term “global” as part of their mission or vision value this area of practice, one would expect those schools to integrate global health education into their curriculum at a higher rate. If a school values “global health,” it is important that their mission or vision statements reflect this, as doing so may help recruit students and faculty members interested in this area and may be used to justify dedicated faculty time for advancing global health initiatives. Schools that are interested in adding or expanding global health education should consider dedicating at least 0.5 FTEs to this area, which can be used to advance global health initiatives, including but not limited to introducing or expanding global health coursework and creating a global health office. Although our survey was not designed to address this, there exists variability in international training sites, school resources, and university policies/procedures, which can all impede a program’s ability to standardize global health. Efforts should be made to guide colleges and schools of pharmacy in developing these experiences. The AACP GPE-SIG white papers can assist schools with best practices for global health APPEs.28,29

The primary limitation to our study is the relatively low response rate of 43%, increasing the risk for nonresponse bias. This is not surprising, as a decline in survey participation studies has been noted over the years.30 Although we used survey methodologies to increase the response rate, a multi-modal approach (eg, through telephone calls, mailings, or incentives) may have been beneficial. The response rate did vary regionally, and our data are likely better representative of schools located in the Northeast and Midwest than those in the rest of the country. When assessing nonresponders, survey demographics were similar in respect to accreditation, public or private, and geographical location status. Some faculty members interested in or experienced in international or global education may have been missed if they were not members of the GPE-SIG, while other faculty members who do hold membership in this SIG may be members merely because they have an interest in global health, not necessarily because they are actively involved or aware of global health activities on their campus. Additionally, although definitions were provided within each section of the survey, some questions may have been subjective, thus introducing the risk for response bias (ie, what one respondent views as “global health” another may not). Since global health offerings vary in content and structure at pharmacy schools, our approach may not have captured all facets of global health education. Future research should assess the presence and impact of established relationships between global health student organizations (such as the student International Pharmaceutical Federation) and their respective schools of pharmacy, teaching modalities in the area of global health didactic education, and structure of the global health experiential learning setting.

CONCLUSION

In order to increase pharmacy involvement in global health, PharmD programs should consider integrating (or expanding) global health didactic curricular content. For those programs unable to adequately integrate the topic into their required didactic curriculum, elective coursework provides a viable alternative. Whether it is in the context of required or elective coursework, didactic education can be used to prepare students planning to engage in international or global experiences. Efforts should be made to integrate elective coursework and experiences with the ACPE Standards and CAPE Guidelines. As the GPE-SIG has drafted standards, best practices, and a strategic plan, US colleges and schools of pharmacy should consider an outcomes-based approach to their international and global health experiences for optimal student learning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Thomas Buckley, RPh, MPH, for assisting with the survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1993–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Audus KL, Moreton JE, Normann SA, et al. Going global: the report of the 2009-2010 Research and Graduate Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):Article S8. doi: 10.5688/aj7410s8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy strategic plan. 2012; http://www.aacp.org/about/Pages/StrategicPlan.aspx. Accessed March 21, 2014.

- 4.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Global Alliance for Pharmacy Education (GAPE). http://www.gapenet.org/en-US/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed January 23, 2015.

- 5.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Practice and research networks. http://www.accp.com/about/prns.aspx. Accessed March 21, 2014.

- 6.Anderson C, Bates I, Beck D, et al. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce: enabling concerted and collective global action. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 127. doi: 10.5688/aj7206127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Addo-Atuah J, Dutta A, Kovera C. A global health elective course in a PharmD curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10):Article 187. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cisneros RM, Jawaid SP, Kendall DA, et al. International practice experiences in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(9):Article 188. doi: 10.5688/ajpe779188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werremeyer AB, Skoy ET. A medical mission to Guatemala as an advanced pharmacy practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(8):Article 156. doi: 10.5688/ajpe768156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steeb DR, Overman RA, Sleath BL, Joyner PU. Global experiential and didactic education opportunities at US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(1):Article 7. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godkin M, Savageau J. The effect of medical students’ international experiences on attitudes toward serving underserved multicultural populations. Fam Med. 2003;35(4):273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta AR, Wells CK, Horwitz RI, Bia FJ, Barry M. The International Health Program: the fifteen-year experience with Yale University’s internal medicine residency program. Am J Trop Med. 1999;61(6):1019–1023. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Hunt DD, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):342–347. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connell MB, Rodriguez de Bittner M, Poirier T, et al. Cultural competency in health care and its implications for pharmacy part 3A: emphasis on pharmacy education, curriculums, and future directions. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(12):e347–367. doi: 10.1002/phar.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree (draft standards 2016). https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2015.

- 16.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC launches new global health education initiative to enhance opportunities for medical students and faculty worldwide. https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/349278/071513.html. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 18.Gleason SE, Covvey JR, Abrons JP, et al. Connecting global/international pharmacy education to the CAPE 2013 outcomes: a report from the global pharmacy education special interest group. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/cape/Documents/GPE_CAPE_Paper_November_2015.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2016.

- 19.Patterson BY. An advanced pharmacy practice experience in public health. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5):Article 125. doi: 10.5688/aj7205125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Consortium of Universities for Global Health. Global health training modules. http://cugh.org/resources/educational-modules. Accessed March 21, 2014.

- 21.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Preaccredited and accredited professional programs of colleges and schools of pharmacy. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/shared_info/programsSecure.asp. Accessed March 21, 2014.

- 22.Merson MH, Black RE, Mills AJ. Global Health: Diseases, Programs, Systems, and Policies. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sagraves R, Alexandria V. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Survey of US colleges/schools of pharmacy concerning international education and research relationships [unpublished raw data]. 2007.

- 24. Sagraves R, Alexandria V. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Survey of current global affiliations of US colleges and schools of pharmacy [unpublished raw data]. 2010.

- 25.Merson MH, Page KC. The dramatic expansion of university engagement in global health: implications for US policy. A report of the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) global health policy center. 2009; https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/Univ_Engagement_in_GH.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2015.

- 26.American Academy of Family Physicians. Global health: recommended curricular guidelines for family medicine residents. AAFP Number 287. http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint287_Global.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- 27.Brock TP, Le PV, Shoeb M. Teaching global health ethics using simulation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:Article 111. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dornblaster EK, Ratka A, Gleason SE, et al. Current practices in global/international advanced pharmacy practice experiences: preceptor and student considerations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(3):Article 39. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alsharif NZ, Dakkuri A, Abrons JP, et al. Current practices in global/international advanced pharmacy practice experiences: home/host country or site/institution considerations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe80338. Article 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheehan KB. E-mail survey response rates: a review. J Compu-Mediated Com. 2001;6(2) [Google Scholar]