Abstract

Recent studies have demonstrated that the Na+/K+-ATPase is not only an ion pump, but also a membrane receptor that confers the ligand-like effects of cardiotonic steroids (CTS) such as ouabain on protein kinases and cell growth. Because CTS have been implicated in cardiac fibrosis, this study examined the role of caveolae in the regulation of Na+/K+-ATPase function and CTS signaling in cardiac fibroblasts. In cardiac fibroblasts prepared from wild-type and caveolin-1 knockout [Cav-1(−/−)] mice, we found that the absence of caveolin-1 did not affect total cellular amount or surface expression of Na+/K+-ATPase α1 subunit. However, it did increase ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake. While knockout of caveolin-1 increased basal activities of Src and ERK1/2, it abolished activation of these kinases induced by ouabain but not angiotensin II. Finally, ouabain stimulated collagen synthesis and cell proliferation in wild type but not Cav-1(−/−) cardiac fibroblasts. Thus, we conclude that caveolae are important for regulating both pumping and signal transducing functions of Na+/K+-ATPase. While depletion of caveolae increases the pumping function of Na+/K+-ATPase, it suppresses CTS-induced signal transduction, growth, and collagen production in cardiac fibroblasts.

Keywords: Na+/K+-ATPase, caveolae, ouabain, cardiac fibrosis, digitalis signaling

INTRODUCTION

Na+/K+-ATPase, the biochemical correlate of the physiological Na+ pump, is a plasma membrane-embedded protein that enzymatically breaks down cellular ATP in order to actively transport Na+ and K+ ions against their electrochemical gradients. The accumulated energy derived from this process is utilized to perform numerous tasks such as the regulation of cell volume, pH and resting transmembrane potential [1]. The ion pumping function of Na+/K+-ATPase is specifically inhibited by ouabain and other compounds that belong to a class of exogenous and endogenous cardenolides and bufadienolides collectively known as cardiotonic steroids (CTS).

Besides the classical pumping activity, a pool of cellular Na+/K+-ATPase has been shown to perform nonpumping functions [2]. The nonpumping Na+/K+-ATPase resides in caveolae [3], small membrane invaginations rich in cholesterol, sphingolipids and the marker protein caveolin. It is known that caveolae cluster receptors and signaling molecules together and thus play an important role in regulating the efficiency of signal transduction [4]. Highly relevant to the present study, caveolae have been shown to regulate both pumping and signal transducing functions of Na+/K+-ATPase in cultured cells. For instance, in vitro depletion of either cholesterol or caveolin-1 in LLC-PK1 cells reduces CTS-induced activation of protein kinase cascades whereas it increases Na+ pump activity [2,5].

Many research groups have demonstrated that the same CTS involved in blocking the pumping function are responsible for triggering Na+/K+-ATPase-mediated signal transduction pathways through a series of protein-protein interactions, generating diverse biological effects [6-10]. For instance, CTS stimulate the activation of protein kinases such as Src and ERK1/2, the generation of reactive oxygen species and consequently fibrosis in the heart [12-14].

Cardiac fibroblasts represent a large fraction of the myocardial tissue. Indeed, although cardiac myocytes account for 75% of the whole volume of myocardium, they do not represent more than 40% of myocardial cells. The remainder 60% is composed mostly of fibroblasts [14]. Although they were thought to be inert cells, we now know that they contribute to structural, biochemical, mechanical and electrical properties of the heart. They are associated with myocardial remodeling [15] and are considered target cells for endogenous CTS. We have shown that CTS produce cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in vivo. In vitro, we showed that the underlying molecular mechanism is CTS-induced collagen synthesis in rat cardiac fibroblasts through Na+/K+-ATPase-mediated signaling [11,13]. Interestingly, cardiac fibroblasts only express caveolin-1, thus knockout of caveolin-1 abolishes the formation of caveolae in these cells. Therefore, to further study the role of caveolae in the regulation of Na+/K+-ATPase functions and to test whether the knockout of caveolin-1 is sufficient to abolish ouabain-induced signal transduction and growth regulation, we investigated the pumping and signaling functions of Na+/K+-ATPase and ouabain-induced collagen synthesis in isolated cardiac fibroblasts from Cav-1(−/−) mice. Our findings demonstrate that lack of caveolae enhances Na+ pump activity but reduces Na+/K+-ATPase-mediated signaling function in cardiac fibroblasts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of cardiac fibroblasts

Adult wild type (C57BL/6J) and Cav-1(−/−) (Cav1tm1Mls/J) mice (Jackson Laboratory, USA) were heparinized and anesthetized with pentobarbital. Hearts were rapidly excised, cannulated and subjected to retrograde perfusion with Joklik’s medium plus 0.06% collagenase type 2. Dissociated cardiac cells were centrifuged for 2 min at 500 rpm to remove cardiomyocytes [16]. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged for 7 min at 1,500 rpm. The pellet was suspended and seeded in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and amphotericin B (2.5 μg/ml). After 2 h of incubation, the medium was replaced by fresh medium without amphotericin B. Attached cells were allowed to grow until confluence and verified as cardiac fibroblasts by positive staining for vimentin but negative for von Willebrand factor, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain and sarcomeric tropomyosin. Unless otherwise stated, cardiac fibroblasts were used up to the third passage and were serum-starved overnight before treatments.

Ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake

The Na+ pump activity was estimated by ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake. Wild type and Cav-1(−/−) primary fibroblasts were cultured in 12-well plates and incubated for 10 min in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 20 μM monensin in the absence or presence of 1 mM ouabain at 37 °C. T he assay began with the addition of 1 μCi 86Rb+/well and was stopped after 10 min by washing each well once with 3 ml of ice-cold 100 mM MgCl2 and twice with 2 ml of the same solution. Cells were lysed for 45 min at 37 °C with 10% trichloroac etic acid. The soluble fraction was measured for 86Rb+ radioactivity using a liquid scintillation counter. The TCA-precipitated protein was dissolved in 0.1 N NaOH/0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution for Lowry protein assay. Na+/K+-ATPase-mediated 86Rb+ uptake was determined as the difference between the uptake measured in the presence or absence of 1 mM ouabain [2]. The ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake was about 80% of total activity.

Western blot analysis

Wild type and Cav-1(−/−) cardiac fibroblasts were treated for 5 min with different concentrations of ouabain or Angiotensin II (100nM), washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with ice-cold modified radioimmune precipitation assay buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 nM okadaic acid and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Cell lysates were nutated for 30 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 10 min. Supernatant samples (15 μg protein/lane) were subjected to electrophoresis on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and separated proteins were transferred onto Optitran membranes. Membranes were blocked with 4% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline solution plus 0.05% Tween 20 for 1 h followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with one of the following primary monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies in blocking solution: anti-Na+/K+-ATPase α1 subunit (α6F, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, USA), anti-Na+/K+-ATPase α2 subunit (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA), anti-Na+/K+-ATPase α3 subunit (Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO, USA), anti-phosphoERK1/2, anti-ERK1/2 (clone C-14), anti-actin (clone C-11) and anti-caveolin-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). After 1 h incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-goat or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), Immunoreactivity was detected using chemiluminescence (Pierce, USA) and scanned images were analyzed by ImageJ software (NIH, USA).

Na+-dependence of ouabain-sensitive ATPase activity

Microsomes from mouse kidney medullas were prepared as described previously [16]. Na+/K+-ATPase activity was measured as a function of Na+ concentration by determination of inorganic phosphate released after incubation for 20 min at 37 °C in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 1mM MgCl2, 20mM KCl, 1mM EGTA, 5mM NaN3, 2 mM MgATP and different concentrations of NaCl (0-100 mM). Each assay was done in the presence or absence of 1 mM ouabain, and the ouabain-sensitive component was considered as Na+/K+-ATPase activity. Pi was measured with Malachite Green, using the Biomol Green reagent (BIOMOL Research Laboratories, PA). Na+ curve fitting was done using Prism software v5.03 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA)

Biotinylation of plasma membrane proteins

The following procedures were performed at 4°C as described [2,17]. Confluent cardiac fibroblasts were washed twice with ice-cold PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and incubated twice with 1.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-ss-biotin in biotinylation buffer containing 2 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl, sucrose 250 mM and 10 mM triethanolamine (pH 9.0) for 25 min. Soluble – sulfo-NHS-ss-biotin was washed out by means of two rinses with PBS followed by 20 min of quenching with PBS plus 100 mM glycine. Then, cells were lysed with lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) for 60 min, centrifuged at 16,000 xg for 10 min and the supernatant was incubated with immobilized streptavidin-agarose beads in lysis buffer overnight with end-to-end rotation. The suspension was spun down and the supernatant collected as unbound fraction. The pellet was washed twice with lysis buffer, followed by high salt (0.1% Triton X-100, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5) and no salt buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5). Bound proteins were recovered by re-suspending the pellet in Laemmli loading buffer and incubating for 30 min at 55°C.

Cell immunostaining

After two washes with PBS, cardiac fibroblasts grown on glass coverslips were fixed with pre-chilled methanol for 15 min, washed again with PBS and blocked with Image-iT FX signal enhancer (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at room temperature. Rabbit polyclonal anti-Src [pY418] (1:100, BioSource, USA) with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS was used for overnight incubation at 4°C, followed by incubation with anti-rabbit IgM Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:100, Invitrogen, USA) for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. Coverslips were mounted using Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and were visualized with a Leica DM IRE2 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Densitometric analysis from at least 5 different microscopic fields from each coverslip was carried out using ImageJ software.

Cell proliferation

Assessment of proliferative response was performed as previously reported by Abramovitz et al. [18]. Briefly, primary cultures of wild type and Cav-1(−/−) cardiac fibroblasts were seeded at the average number of 7-8.5 × 103 cells/ml. After 24 h, the medium was changed from 10% to 5% FBS DMEM in the absence or presence of ouabain. After 5 days, cells were trypsinized and counted with a Neubauer hemocytometer.

[3H]Proline incorporation

Collagen synthesis was assessed in confluent wild type and Cav-1(−/−) cardiac fibroblasts as described by Elkareh et al [11], with modifications. Cells were incubated with different concentrations of ouabain for 24 h. Twelve hours before the end of ouabain treatment, [3H]proline (1 μCi/ml) was added. Fibroblasts were then washed three times with ice-cold PBS and proteins were precipitated with 10% TCA for 30 min at 4°C. Elution was performed with 0.1 N NaOH/0.2% SDS solution and an aliquot was used to count the radioactivity using a liquid scintillation counter.

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as mean ± SE of at least three independent experiments. Student’s t test was performed and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Cav-1 knockout increases Na+ pump activity in cardiac fibroblasts

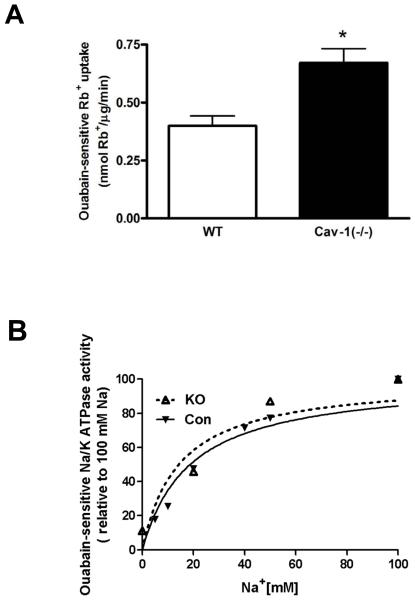

The presence of two interchangeable but functionally separable pools of Na+/K+-ATPases, one performing the conventional ion pumping and the other mediating noncanonical (e.g., signaling) functions, has been demonstrated in cultured cells [2]. Moreover, caveolae integrity appears to be a key factor for controlling the formation of these two pools of Na+/K+-ATPases. Specifically, the pumping activity of Na+/K+-ATPase is increased in LLC-PK1 cells by depletion of cholesterol or knockdown of caveolin-1 [2]. Consistently, we found that the absence of caveolin-1 in vivo resulted in a significant increase in maximal ouabain-sensitive Rb+ uptake in cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 1A). To rule out a change in intracellular Na+ concentration, the assay was performed in the presence of the ionophore monensin (20 μm) to clamp intracellular Na+ and ensure maximal capacity of active uptake in all conditions as we did previously [2]. Because knockout of caveolin-1 could alter other regulatory mechanisms of Na+/K+-ATPase, we further assessed the Na+-dependent activation of ATPase. The kidney microsomes were used because the amount of cardiac fibroblasts was limited. As depicted in Fig. 1B, the ouabain-sensitive Na+/K+-ATPase activities from WT and cav-1(−/−) kidney preparations showed the same Na+-dependence, suggesting that this important characteristic of the enzyme kinetics was not altered.

Figure 1.

A. Increased Na+/K+-ATPase pumping activity in cardiac fibroblasts from caveolin-1 knockout mice [Cav-1(−/−)]. Primary fibroblasts were assayed for ouabain-sensitive Rb+ uptake for 10 min after treatment with 20 μM monensin. Data are means ± SE of 5 different preparations. * p < 0.05. B. Na,K-ATPase activity as a function of Na+ concentration in kidney microsomes from WT or cav-1 (−/−) mice. Data are means ± SE of 4 different preparations. Na+ Km were 19.6±1.2 mM and 15.3 ±2.7 mM for WT and cav-1(−/−), respectively.

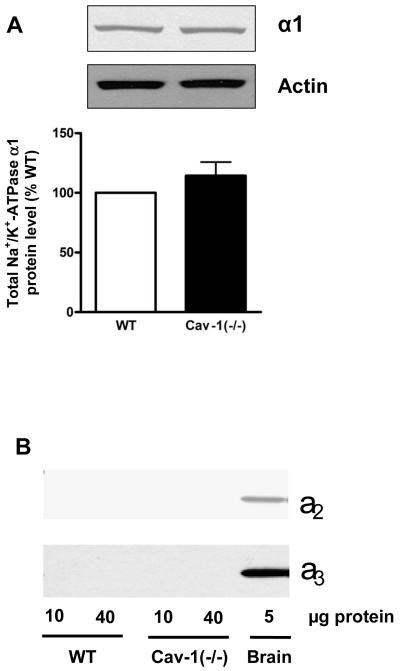

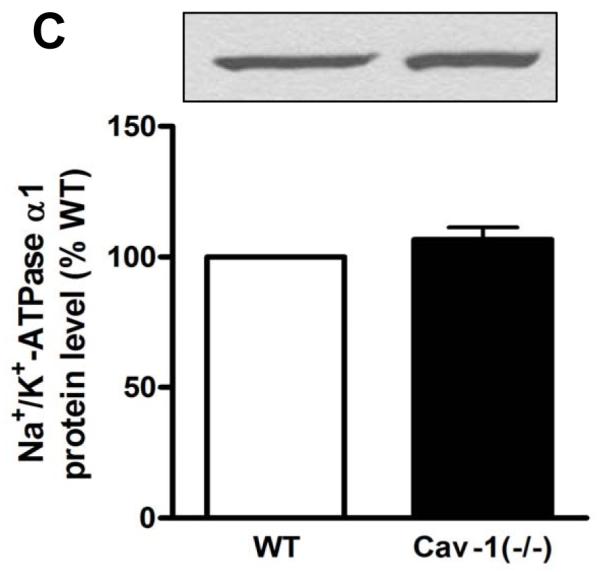

A large body of evidence indicates that an intracellular pool of Na+/K+-ATPase exists in distinct cell types [2,19] and Rb+ uptake technique only assesses the activity of pumps present in the plasma membrane. Thus, the higher Na+ pump activity seen in Cav-1(−/−) fibroblasts could be a consequence of a higher Na+/K+-ATPase density in these cells. Since rodent fibroblasts contain only the α1 subunit isoform of Na+/K+-ATPase [20,21], the expression of this isoform was examined by immunoblot. As depicted in Fig. 2A, there was no difference in the total amount of α1 between wild type and Cav-1(−/−) cells. Control experiments confirmed the absence of other α subunit isoforms in both WT and cav1(−/−) fibroblasts (Fig 2B). Moreover, we detected comparable amounts of α1 in biotinylated fractions (Fig. 2C) from wild type and Cav-1(−/−) fibroblasts, indicating that the increase in ouabain-sensitive Rb+ uptake was not due to an increased surface expression of Na+/K+-ATPase. Taken together, these findings suggest that knockout of Cav-1 may increase the ion pumping activity of Na+/K+-ATPase that are already present at the plasma membrane in cardiac fibroblasts.

Figure 2.

Na+/K+-ATPase α1 subunit protein expression in cardiac fibroblasts from caveolin-1 knockout mice [Cav-1(−/−)]. Western blot assay for total cell lysates of primary fibroblasts probed with anti-Na+/K+-ATPase α1, α2 and α3 antibodies (A and B). Wild type mouse brain homogenate was used as a positive control (B). Western blot assay for biotinylated fraction of primary fibroblasts with anti-Na+/K+-ATPase α1 (C). Representative immunoblots are shown, and quantitative data ( α1/actin ratios in 2A or biotinylated α1 in 2C) are depicted as % of wild type (WT) value, corresponding to mean ± SE of 3 to 5 different preparations.

Cav-1 knockout attenuates ouabain-induced signaling in cardiac fibroblasts

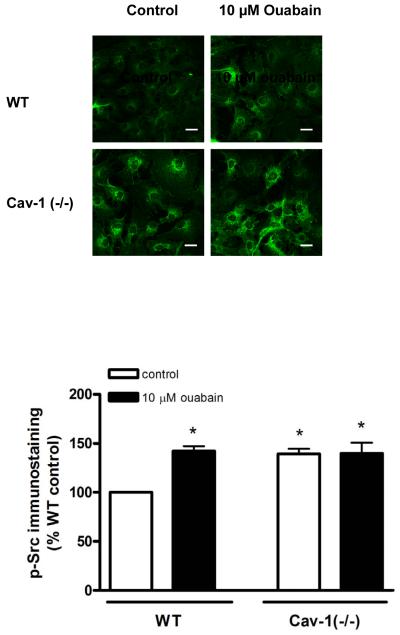

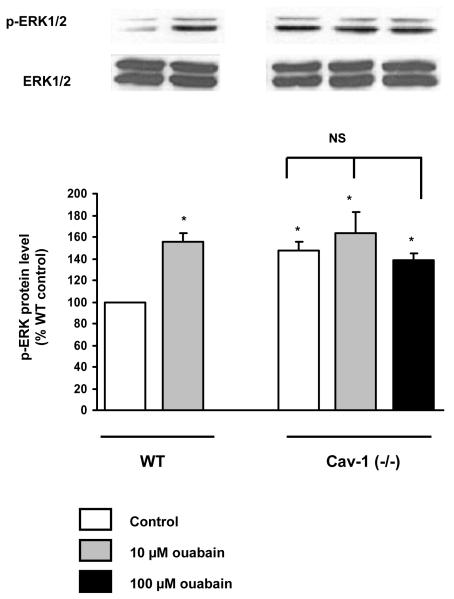

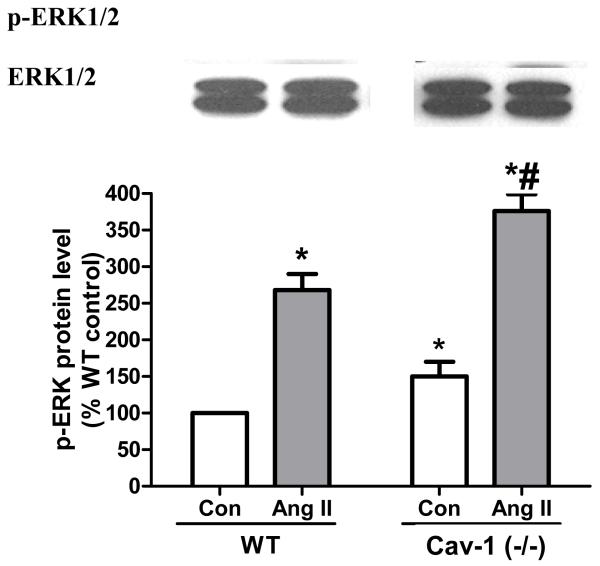

Considering that caveolae are important for Na+/K+-ATPase-mediated signal transduction, we investigated whether ouabain was able to stimulate Src and ERK1/2, two sets of essential protein kinases down-stream from the activation of the CTS receptor Na+/K+-ATPase, in Cav-1(−/−) fibroblasts. Previous works revealed that activation of these kinases takes place within 5 min following an exposure to μM concentrations of ouabain [22-24]. Using immunostaining technique with anti-Src [pY418] antibody, we found that 5 min treatment with 10 μM ouabain significantly increased the amount of active Src in wild type mouse cardiac fibroblasts, but not in Cav-1(−/−) cells (Fig. 3). Likewise, 10 μM ouabain induced ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 4A). In contrast, no activation was detected for Cav-1(−/−) cardiac fibroblasts, even when ouabain concentration was raised to 100 μM. Total ERK1/2 expression did not exhibit any significant difference among the experimental groups studied. In contrast, 5 min incubation with 100 nM Angiotensin II, another well-known activator of ERK1/2 pathway, resulted in a strong increase in phospho ERK1/2 signal in cav1−/− fibroblasts, comparable to that observed in WT cells ( Figure 4B). Our results also indicate that adult Cav-1(−/−) fibroblasts presented an increased basal activity of Src and ERK1/2 when compared to the wild type cells, which is in agreement with the suppressive role of caveolin on these kinases [25-27].

Figure 3.

Immunocytostaining of phosphorylated Src in ouabain-treated cardiac fibroblasts from caveolin-1 knockout mice [Cav-1(−/−)]. Serum-starved primary fibroblasts were treated for 5 min with 10 μM ouabain, fixed and immunostained with anti-Src [pY418] antibody. (A) Representative images of primary cultured fibroblasts are shown. Bar, 20 μM. (B) Quantitative data depicted as % of wild type (WT) control value, corresponding to mean ± SE of densitometric analysis from at least 5 different microscopic fields (at least 10 cells/field) from each coverslip of 3 to 4 different cell batches. * p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Effect of ouabain (A) and angiotensin II (B) on phosphorylated ERK1/2. Serum-starved primary fibroblasts were treated for 5 min with the indicated dose of ouabain or 100 nM Angiotensin II, and total cell lysates were assayed for Western blot with anti-phosphoERK1/2 and anti-ERK1/2 antibodies. Representative immunoblots (p-ERK1/2 and ERK1/2) and quantitative data (p-ERK1/2 levels as estimated by the p-ERK1/2/ERK1/2 ratios) depicted as % of wild type (WT) value are shown. Values are mean ± SE of 3 to 7 different preparations * p < 0.05 vs WT control. # p< 0.05 vs cav-1 (−/−) control. NS, not significant.

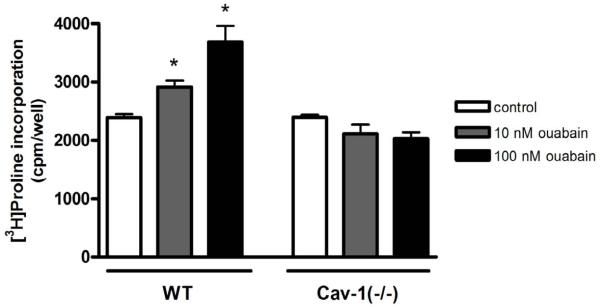

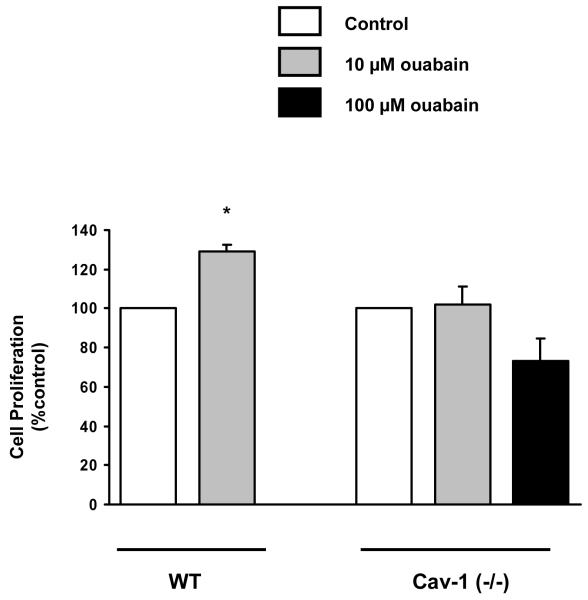

Cav-1 knockout reduces ouabain-induced collagen production and proliferation in cardiac fibroblasts

Several cellular functions are clearly mediated by Na+/K+-ATPase signaling [3]. Critical to fibroblast function in various tissues including the heart, CTS promote collagen synthesis [11] and cell proliferation [18] in rodent cells at concentrations that hardly affect Na+ pumping activity. Because caveolin-1 knockout inhibited the agonist effect of ouabain on Src and ERK1/2 kinases, we examined how it would affect fibroblast function. Based on prior studies [12], we used [3H]proline incorporation to assess the effect of ouabain on collagen production. As depicted in Fig. 5, ouabain at nM concentrations was sufficient to stimulate [3H]proline incorporation in mouse cardiac fibroblasts as it did in primary cultures of rat cardiac fibroblasts [12]. However, it failed to do so in cardiac fibroblasts from Cav-1(−/−) mice. Similarly, ouabain (10 μM) increased the proliferation of these cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 6). On the other hand, it showed no effect on cell growth in fibroblasts from Cav-1(−/−) mice even when ouabain concentration was raised to 100 μM (Fig. 6). Taken together, these findings indicate that the blunted signaling resulted in an impaired functional outcome.

Figure 5.

Collagen synthesis examined by [3H]proline incorporation in ouabain-treated cardiac fibroblasts from caveolin-1 knockout mice [Cav-1(−/−)]. Serum-starved primary fibroblasts were treated for 24 h with 10 or 100 nM ouabain and [3H]proline incorporation was measured. Data are means ± SE of 4 different preparations. * p < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Proliferation of ouabain-treated cardiac fibroblasts from caveolin-1 knockout mice [Cav-1(−/−)]. Primary fibroblasts in 5% fetal bovine serum were treated with 1 or 10 μM ouabain and counted after 5 days. Data are depicted as % of control value and correspond to mean ± SE of 4 different preparations. * p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Recent works have uncovered the importance of caveolin-1/caveolae for the assembly and function of Na+/K+-ATPase signalosome [2,5,28-30]. In these studies, in vitro approaches in immortalized cell lines were used to produce short-term reduction of cholesterol or caveolin-1 cell content. Here we took advantage of the availability of the Cav-1 knockout mouse model to functionally evaluate the proposed roles of caveolin/caveolae in the formation of two different pools of Na+/K+-ATPases as well as CTS signaling in regulation of cardiac fibrosis. In cardiac fibroblasts, a cell type that expresses Cav-1 but not Cav-2 or 3 isoform, we confirm that caveolin/caveolae regulate both pumping and signaling functions of Na+/K+-ATPase and bring the first ex vivo evidence for the functional impact of the disruption of caveolae in CTS-regulation of fibroblast growth and collagen production.

Our first set of experiments aimed to explore whether the ion pumping function of Na+/K+-ATPase would be affected by caveolin-1 knockout. Although such alteration was seen in vitro, it has been suggested that compensatory mechanisms could counteract caveolin deletion in vivo [31]. Hence, it was important to verify that our prior in vitro findings made in renal epithelial cell lines hold true in primary cultures of cardiac fibroblasts from genetically altered animals. Our results indicate that the absence of caveolin-1 in vivo does not affect total or plasma membrane abundance of Na+/K+-ATPase α1 isoform in cardiac fibroblasts. This is an important observation because different proteins including caveolin-2, endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthase have their expression changed in Cav-1(−/−) mice [27,32]. We also demonstrated that the maximal Na+ pump activity is significantly increased in these cells. These findings are consistent with the notion that cells contain a pool of non-pumping Na+/K+-ATPase in caveolae and that disruption of caveolae can convert this pool into pumping Na+ pumps.

Next, we examined the CTS-induced signal transduction in Cav-1(−/−) cardiac fibroblasts. The activation of Src/ERK1/2 was used as an indicator of the well characterized protein kinase cascade triggered by CTS [22]. Mouse fibroblasts express only the relatively insensitive Na+/K+-ATPase α1 isoform, and the ouabain IC50 to inhibit maximal Na+/K+-ATPase pumping activity in rodent fibroblasts is ≥ 100 μM [11,20,33,34]. In fibroblasts from wild-type mice, we observed the activation of Src/ERK1/2 by 10 μM ouabain as reported in other ouabain-resistant cells like rat cardiomyocytes, rat A7r5 cells and rat cardiac fibroblasts [11,22]. In contrast, we did not detect any stimulation of this molecular pathway by ouabain in Cav-1(−/−) fibroblasts. Because Angiotensin II-induced activation of ERK pathway was preserved in cav-1(−/−) fibroblasts (figure 4B), we concluded that the defect was not due to a general alteration of ERK signaling in cav1−/− fibroblasts. Rather, the defect is most likely the result of one of two possible alterations of Na+/K+-ATPase function induced by cav1 knockout. The first one would be a decrease in ouabain affinity of the Na+/K+-ATPase receptor itself, and the second a deficiency in the signaling response to ouabain exposure. Because [3H] ouabain binding studies cannot be adequately used to study the low affinity Na+/K+-ATpase receptor in rodent, a change in ouabain binding property cannot be completely excluded in the present study. However, based on our previous studies in ouabain-sensitive-cav-1 knock-down pig kidney cells [2] and the well-established role of caveolin 1 in ouabain signaling [5], the absence of ouabain-induced ERK activation observed in cav-1(−/−) fibroblasts strongly suggests that ouabain signaling is inhibited in the absence of cav-1 in vivo.

On the other hand, basal Src and ERK1/2 are hyperactivated in Cav-1(−/−) cardiac fibroblasts. The negative regulatory effects of caveolin-1 on these protein kinases have been previously described [25-27]. To our knowledge, however, this is the first report of Src hyperactivation in Cav-1(−/−) mouse cells. In addition, the conversion of signaling into pumping Na+/K+-ATPase caused by knocking out caveolin-1 may also contribute to the observed increase in basal activities of these kinases. We reported that the interaction between the Na+/K+-ATPase and Src controls the basal Src activity by keeping the kinase in an inactive state in the absence of ouabain [35,36]. Hence, graded knockdown of Na+/K+-ATPase, which favors the disappearance of nonpumping Na+/K+-ATPases and preserves the pool of pumping enzymes in the cell [2], increases the levels of active cellular Src and ERK1/2 [36,37]. This seems to be also true when Na+/K+-ATPase is down-regulated in vivo [38,39]. Thus, any procedure that affects signaling Na+/K+-ATPase or caveolin expression may alter the kinase activity, providing a further degree of complexity to these signal transducing pathways.

The impairment of ouabain-evoked regulation of cardiac fibroblast function was further assessed by collagen production and cell proliferation. In line with what was observed with Src and ERK1/2, low concentrations of ouabain stimulated proline incorporation and proliferative growth in cells from wild type but not from cav-1 (−/− animals. These responses induced by ouabain, at similar concentration ranges, corroborate what was described by Abramowitz et al [18] for rat vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and Elkareh et al [11] for rat cardiac fibroblast collagen synthesis. It is important to note that, unlike the acute (5-10 min) effect of ouabain on Src and ERK, the long-term effects on proline incorporation occur at much lower (nM vs μM) ouabain concentration. Although many laboratories have reported such left-shifts of the dose-response curves under prolonged ouabain exposure (11, 18, 40, 41), the underlying mechanism remains unclear. In apparent contradiction, the other long term effect reported here (cell proliferation) is detectable upon exposure to μM rather than nM concentrations of ouabain. This observation raises the interesting possibility that the proliferative effect may result from the combined effects of a prolonged ouabain exposure on both Na+/K+-ATPase activity and signaling. In other words, it is important to keep in mind that some of the physiological effects of cardiotonic steroids, such as the proliferative effect on cardiac fibroblasts reported here, may be ultimately dependent on the downstream change in cellular metabolism or ion concentrations in addition to Na+ pump-dependent signaling.

In conclusion, we report here that complete ablation of caveolin-1/caveolae by in vivo genetic knockout increments Na+/K+-ATPase pumping function while depressing its signaling function in cardiac fibroblasts. Even though the precise mechanism by which disruption of caveolae leads to decreased signaling and increased ion-pumping activity of Na,K-ATPase remains to be established, the data support the hypothesis of the existence of two inter-changeable pools of the enzyme in living cells, one that performs ion transport and the other that mediates a signaling cascade through protein-protein interactions. Given the role of CTS in cardiac fibrosis, it will be of great interest to verify whether the systemic effects of CTS on cardiac structure and function would be affected in Cav-1(−/−) animals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-36573 and GM-78565, awarded by the United States Public Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services. L.E.M.Q. is recipient of postdoctoral fellowship from CNPq (Brazil). The authors wish to thank Mrs. Xiaochen Zhao for the assistance with the primary cell culture.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: none declared

References

- [1].Kaplan JH. Biochemistry of Na,K-ATPase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:511–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.102201.141218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liang M, Tian J, Liu L, Pierre S, Liu J, Shapiro J, et al. Identification of a pool of non-pumping Na/K-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10585–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Xie Z, Cai T. Na+-K+-ATPase-mediated signal transduction: from protein interaction to cellular function. Mol Interv. 2003;3:157–68. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.3.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Patel HH, Murray F, Insel PA. Caveolae as organizers of pharmacologically relevant signal transduction molecules. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:359–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.121506.124841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wang H, Hass M, Liang M, Cai T, Tian J, Li S, et al. Ouabain assembles signaling cascades through the caveolar Na+/K+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17250–59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Xie Z, Askari A. Na+/K+-ATPase as a signal transducer. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:2434–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu J. Ouabain-induced endocytosis and signal transduction of the Na/K-ATPase. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2056–63. doi: 10.2741/1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nesher M, Shpolansky U, Rosen H, Lichtstein D. The digitalis-like steroid hormones: New mechanisms of action and biological significance. Life Sci. 2007;80:2093–107. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schoner W, Scheiner-Bobis G. Endogenous cardiac glycosides: Hormones using the sodium pump as signal transducer. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Aperia A. New roles for an old enzyme: Na,K-ATPase emerges as an interesting drug target. J Intern Med. 2007;261:44–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Elkareh J, Kennedy DJ, Yashaswi B, Vetteth S, Shidyak A, Kim EG, et al. Marinobufagenin stimulates fibroblast collagen production and causes fibrosis in experimental uremic cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2007;49:215–24. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252409.36927.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Elkareh J, Periyasamy SM, Shidyak A, Vetteth S, Schroeder J, Raju V, et al. Marinobufagenin induces increases in procollagen expression in a process involving protein kinase C and Fli-1: implications for uremic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1219–26. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90710.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kennedy DJ, Vetteth S, Periyasamy SM, Kanj M, Fedorova L, Khouri S, et al. Central role for the cardiotonic steroid marinobufagenin in the pathogenesis of experimental uremic cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2006;47:488–95. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000202594.82271.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Camelliti P, Borg TK, Kohl P. Structural and functional characterisation of cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Camelliti P, Green CR, Kohl P. Structural and functional coupling of cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:132–49. doi: 10.1159/000092566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu L, Askari A. The β-subunit of cardiac Na+/K+-ATPase dictates the concentration of the functional enzyme in caveolae. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C569–78. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00002.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu L, Li J, Liu J, Yuan Z, Pierre SV, Qu W, et al. Involvement of Na+/K+-ATPase in hydrogen peroxide-induced hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1548–56. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Abramowitz J, Dai C, Hirschi KK, Dmitrieva RI, Doris PA, Liu L, et al. Ouabain- and marinobufagenin-induced proliferation of human umbilical vein smooth muscle cells and a rat vascular smooth muscle cell line, A7r5. Circulation. 2003;108:3048–53. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101919.00548.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wolitzky BA, Fambrough DM. Regulation of the (Na++K+)-ATPase in cultured chick skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:9990–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brodsky JL. Characterization of the (Na++K+)-ATPase from 3T3-F442A fibroblasts and adipocytes. Isozymes and insulin sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10458–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Brodsky JL, Guidotti G. Sodium affinity of brain Na+-K+-ATPase is dependent on isozyme and environment of the pump. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:C803–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.5.C803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Haas M, Askari A, Xie Z. Involvement of Src and epidermal growth factor receptor in the signal transducing function of Na+/K+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27832–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tian J, Gong X, Xie Z. Signal-transducing function of Na+-K+-ATPase is essential for ouabain’s effect on [Ca2+]i in rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H1899–907. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kometiani P, Li J, Gnudi L, Kahn BB, Askari A, Xie Z. Multiple signal transduction pathways link Na+/K+-ATPase to growth-related genes in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15249–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Li S, Couet J, Lisanti MP. Src tyrosine kinases, Gα subunits, and H-Ras share a common membrane-anchored scaffolding protein, caveolin. Caveolin binding negatively regulates the auto-activation of Src tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29182–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Engelman JA, Chu C, Lin A, Jo H, Ikezu T, Okamoto T, et al. Caveolin-mediated regulation of signaling along the p42/44 MAP kinase cascade in vivo. A role for the caveolin-scaffolding domain. FEBS Lett. 1998;428:205–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cohen AW, Park DS, Woodman SE, Williams TM, Chandra M, Shirani J, et al. Caveolin-1 null mice develop cardiac hypertrophy with hyperactivation of p42/44 MAP kinase in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C457–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00380.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Liu L, Mohammadi K, Aynafshar B, Wang H, Li D, Liu J, et al. Role of caveolae in signal-transducing function of cardiac Na+/K+-ATPase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C1550–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00555.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu J, Liang M, Liu L, Malhotra D, Xie Z, Shapiro JI. Ouabain-induced endocytosis of the plasmalemmal Na/K-ATPase in LLC-PK1 cells requires caveolin-1. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1844–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yuan Z, Cai T, Tian J, Ivanov AV, Giovannucci DR, Xie Z. Na/K-ATPase tethers phospholipase C and IP3 receptor into a calcium-regulatory complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4034–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Le Lay S, Kurzchalia TV. Getting rid of caveolins: phenotypes of caveolin-deficient animals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:322–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Razani B, Engelman JA, Wang XB, Schubert W, Zhang XL, Marks CB, et al. Caveolin-1 null mice are viable but show evidence of hyperproliferative and vascular abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38121–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lamb JF, MacKinnon MG. Effect of ouabain and metabolic inhibitors on the Na and K movements and nucleotide contents of L cells. J Physiol. 1971;213:665–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Russo JJ, Manuli MA, Ismail-Beigi F, Sweadner KJ, Edelman IS. Na+-K+-ATPase in adipocyte differentiation in culture. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C968–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.6.C968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tian J, Cai T, Yuan Z, Wang H, Liu L, Haas M, et al. Binding of Src to Na+/K+-ATPase forms a functional signaling complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:317–26. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liang M, Cai T, Tian J, Qu W, Xie ZJ. Functional characterization of Src-interacting Na/K-ATPase using RNA interference assay. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19709–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512240200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cai T, Wang H, Chen Y, Liu L, Gunning WT, Quintas LEM, et al. Regulation of caveolin-1 membrane trafficking by the Na/K-ATPase. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1153–69. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Li Z, Xie Z. The Na/K-ATPase/Src complex and cardiotonic steroid-activated protein kinase cascades. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:635–44. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chen Y, Cai T, Wang H, Li Z, Loreaux E, Lingrel JB, et al. Regulation of intracellular cholesterol distribution by Na/K-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14881–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Saunders R, Scheiner-Bobis G. Ouabain stimulates endothelin release and expression in human endothelial cells without inhibiting the sodium pump. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:1054–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Li J, Zelenin S, Aperia A, Aizman O. Low doses of ouabain protect from serum deprivation-triggered apoptosis and stimulate kidney cell proliferation via activation of NF-kappaB. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1848–57. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]