Abstract

Background:

American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines recommend a basal bolus correction insulin regimen as the preferred method of treatment for non–critically ill hospitalized patients. However, achieving ADA glucose targets safely, without hypoglycemia, is challenging. In this study we evaluated the safety and efficacy of basal bolus subcutaneous (SubQ) insulin therapy managed by providers compared to a nurse-directed Electronic Glycemic Management System (eGMS).

Method:

This retrospective crossover study evaluated 993 non-ICU patients treated with subcutaneous basal bolus insulin therapy managed by a provider compared to an eGMS. Analysis compared therapy outcomes before Glucommander (BGM), during Glucommander (DGM), and after Glucommander (AGM) for all patients. The blood glucose (BG) target was set at 140-180 mg/dL for all groups. The safety of each was evaluated by the following: (1) BG averages, (2) hypoglycemic events <40 and <70 mg/dL, and (3) percentage of BG in target.

Result:

Percentage of BG in target was BGM 47%, DGM 62%, and AGM 36%. Patients’ BGM BG average was 195 mg/dL, DGM BG average was 169 mg/dL, and AGM BG average was 174 mg/dL. Percentage of hypoglycemic events <70 mg/dL was 2.6% BGM, 1.9% DGM, and 2.8% AGM treatment.

Conclusion:

Patients using eGMS in the DGM group achieved improved glycemic control with lower incidence of hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL and <70 mg/dl) compared to both BGM and AGM management with standard treatment. These results suggest that an eGMS can safely maintain glucose control with less hypoglycemia than basal bolus treatment managed by a provider.

Keywords: computerized insulin algorithm, diabetes, Glucommander, glycemic management, hypoglycemia, and subcutaneous insulin

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), a basal bolus plus correction insulin regimen is the preferred treatment for non–critically ill patients with good nutritional intake, and use of sliding scale insulin alone is strongly discouraged.1 Current guidelines for inpatient glycemic control recommend a goal of 140-180 mg/dl in the intensive care unit (ICU), with an acceptable range of 110-140 mg/dl in selected populations, and a preprandial goal of 140 mg/dl for those inpatients that are not critically ill.1,2 All guidelines agree that maximal inpatient glucose goals should remain below 180 mg/dl.1-3

Previous studies have demonstrated safe and effective basal bolus strategies with typically 50% of total daily required insulin dose as basal/long acting insulin, and remainder as rapid/short acting insulin with meals and/or as supplemental scale.4,5 The ability to demonstrate acceptable hypoglycemia rates during insulin therapy is of concern to clinicians due to the association of hypoglycemia with increased mortality, length of stay, and hospital complications in non–critically ill patients.6 Further insulin titration by health care providers has been based on paper protocols or clinical judgment without considering important clinical parameters such as renal insufficiency, nutritional intake, diabetes status, and glycemic target range.

Despite these guidelines and recommendations, the widespread use of sliding scale insulin as the primary treatment for patients with hyperglycemia has persisted due in part to the challenges of implementing basal/bolus methodologies.7,8 Even when basal bolus strategies are implemented, staffing concerns, variability in such available services, dose titration inertia, and the highly specialized nature of insulin use can make attaining adequate glycemic target ranges with subcutaneous insulin difficult.9

Due to the challenges of hospital management of hyperglycemia with insulin, emerging technologies using commercial computer-guided insulin dosing software are being explored in the diabetes field. Several commercially available programs have FDA clearance and have been studied for efficacy and safety for intravenous (IV) insulin guidance in hospitalized patients including Glucommander™ (Glytec, Waltham, MA), EndoTool System™ (MD Scientific LLC, Charlotte, NC), and GlucoStabilizer™ (Medical Decision Network, Charlottesville, VA).10-17

These technologies are now expanding to include subcutaneous (SubQ) insulin therapy. Glucommander and EndoTool System are FDA cleared for SubQ insulin therapy in US hospitals and GlucoTab™ (Joanneum Research GmbH, Graz, Austria) is currently being investigated in clinical trails.18 Glucommander is the first and only FDA-cleared comprehensive Electronic Glycemic Management System (eGMS) to demonstrate safety and efficacy of computerized software with SubQ insulin in previous studies.19-24

Methods

This retrospective observational crossover study evaluated the safety and efficacy of basal bolus SubQ insulin therapy managed by providers compared to a nurse-directed eGMS using Glucommander, an insulin-dosing algorithm integrated within the hospitals electronic health record. GM is an FDA-cleared class II medical device for inpatient IV insulin management, IV to SubQ transition, SubQ insulin management, and outpatient SubQ insulin management.

The study included 993 non–critically ill patients (Table 1) across 9 different hospitals, and included general medical/surgical units, cardiovascular units, emergency departments, and critical care. The demographics and clinical characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. Patients were treated with SubQ insulin therapy using eGMS and provider-managed basal bolus (PMBB) before and/or after eGMS during the inpatient admission. The analysis included 3 treatments windows: before GM BGM, during GM DGM, and after GM AGM.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Patients.

| Variable | All groups |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 993 |

| Sex | |

| Male, n (%) | 477 (48) |

| Female, n (%) | 516 (52) |

| Age (years) | 64 |

| Body weight (kg) | 93.8 |

| A1c | 8.2 |

BGM and AGM SubQ insulin therapy was directed by providers utilizing a computerized basal/bolus order set. Initial doses were prescribed by according to body weight in kilogram (kg) or customized at the provider’s discretion and titrated daily by provider order as needed. The prescribed target glucose range was 140-180 mg/dl. Basal insulin was given once or twice daily and prandial insulin was given before meals 3 times daily. Correction insulin was administered using a low, medium or high scale based on BMI for each patient. Administration details in each order set indicated to hold scheduled prandial insulin if the patient was not eating and to give basal insulin if the patient was not eating. There were no instructions for patients with partial meal intake.

DGM patients were initiated on eGMS SubQ insulin by provider order using a weight-based total daily dose of 0.3, 0.5, or 0.7 units per kg to calculate basal and prandial insulin doses or a custom initial dose of prandial and bolus insulin. Correction insulin was also calculated for each patient by the eGMS. The prescribed target glucose range was 140-180 mg/dl. Basal insulin was ordered once or twice daily and prandial insulin was ordered before meals. Correction insulin was recommended as needed for hyperglycemia by eGMS before meals, at bedtime, or during any random BG checks. All daily titrations for basal, prandial insulin, and correction insulin doses were calculated by eGMS until the patient was removed from therapy and managed by the provider. Insulin dose adjustments DGM did not require an additional order from the provider.

Nurses accessed the eGMS through the electronic health record to receive insulin dose recommendations for prandial, basal, and correction insulin. Basal insulin was recommended daily to the nurse through the eGMS and titrated up or down based on the glycemic target of 140-180 mg/dl. The eGMS recommended full, partial, or held prandial insulin doses through a series of on-screen prompts to the nurse. Correction insulin was recommended by the eGMS if the patient’s BG was above the prescribed target glucose range, and the correction scale adjusted daily for each patient based on individualized insulin sensitivity. If prandial and correction insulin were recommended simultaneously, eGMS calculated the total dose recommended and displayed this for the nurse to administer to the patient.

Statistical Methodology

The mean with a measure of variability is reported. A sample preliminary test for the equality of variances indicates that the variances of the groups were significantly different. Therefore, a 2-sample t-test was performed that does not assume equal variance. The P value from the t-tests of the observed sample groups determined statistical 95% significance. For all analyses, reported P values are 2-sided, and P values.05 were considered significant. Mountain States Health Alliance Quality Analysis using QI Macros SPC version 2010.06 performed all statistical analyses.

Results

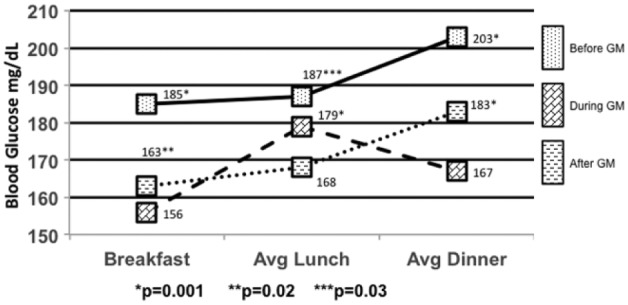

In the BGM group average first BG was 208 mg/dL with an average last BG reading of 214 mg/dL, while hypoglycemia <40 mg/dL was 0.14% and <70 mg/dL was 2.6%. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner for the BGM patients were 185, 187, and 203 mg/dL with an overall BG average of 195 mg/dL. The percentage of BG > 180 mg/dL was 51% and 47% of BGs were in the prescribed target range.

In the DGM group average first BG was 203 mg/dL with an average last BG reading of 172 mg/dL, while hypoglycemia <40 mg/dL was 0.06% and <70 mg/dL was 1.9%. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner for the BGM patients were 156, 179, and 167 mg/dL with an overall BG average of 169 mg/dL. The percentage of BG > 180 mg/dL was 36% and 62% of BGs were in the prescribed target range.

In the AGM group average first BG was 176 mg/dL with an average last BG reading of 181 mg/dL, while hypoglycemia <40 mg/dL was 0.24% and <70 mg/dL was 2.8%. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner for the BGM patients were 163, 168, and 183 mg/dL with an overall BG average of 169 mg/dL. The percentage of BG > 180 mg/dL was 36% and 62% of BGs were in the prescribed target range.

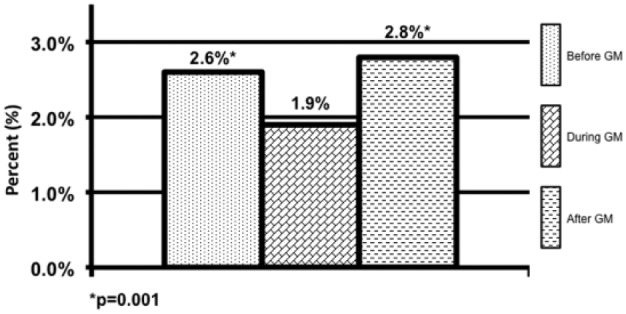

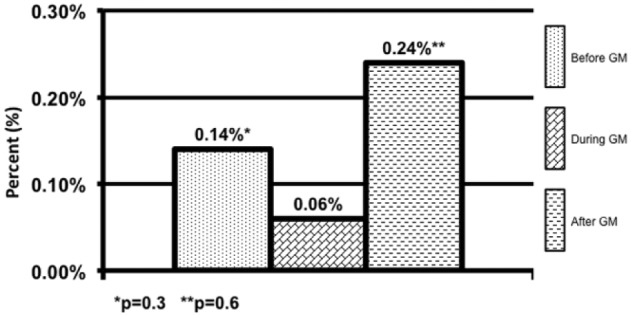

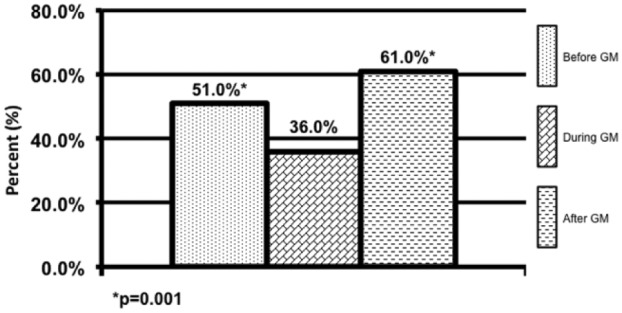

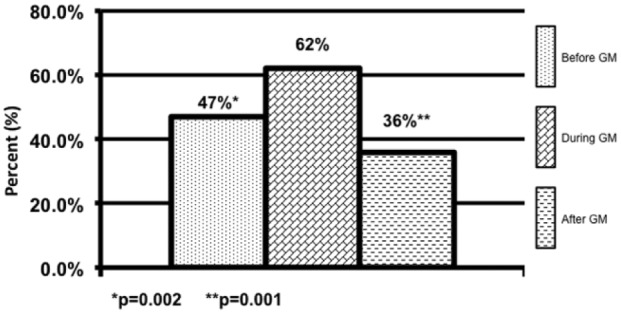

Patients in the DGM group had less mild to moderate hypoglycemia <70 mg/dL 1.9% compared to 2.6% (P = .001) and 2.8% (P = .001) (Figure 1). The DGM group experienced less severe hypoglycemia <40 mg/dl than both the BGM and AGM groups 0.06% compared to 0.14% (P = .38) and 0.24% (P = .565) (Figure 2). The percentage of BG >180 mg/dL was lower in the DG at 36% compared to both BGM and AGM groups at 51% (P = .001) and 61% (P = .001) (Figure 3). The percentage of BG in the prescribed target range of 140-180 mg/dL was higher in the DGM group 62% compared to BGM (P = .002) and AGM 47% and 36% (P = .001) (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Hypoglycemic events <70 mg/dL.

*P = .001.

Figure 2.

Hypoglycemic events <40 mg/dL.

*P = .3. **P = .6.

Figure 3.

Hyperglycemic events >180 mg/dL.

*P = .001.

Figure 4.

Blood glucose in target 140-180 mg/dL.

*P = .002. **P = .001.

The average BG for the DGM group was 169 mg/dL compared to BGM 195 mg/dL (P = .001) and AGM at 174 mg/dL (P = .01) (Figure 5). The average breakfast BG for DGM was 156 mg/dL compared to BGM 185 mg/dL (P = .001) and AGM 163 mg/dL (P = .02) (Figure 5). The average lunch BG for DGM was 179 mg/dL compared to BGM 187 mg/dL (P = .03) and AGM 168 mg/dL (P = .001) with significance toward the AGM group (Figure 5). The average dinner BG for DGM was 167 mg/dL compared to BGM 203 mg/dL (P = .001) and AGM 183 mg/dL (P = .001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mealtime blood glucose averages.

*P = .001. **P = .02. ***P = .03.

Demographics were identical for all 3 groups because of the crossover nature of the study methodology. Mean A1c was 8.2, mean age 64 years, 52% were female, 48% were male, and the mean weight 93.8 kg. Duration of therapy for BGM was 1.2 days, DGM 4.5 days, and AGM 4.2 days.

Discussion

Our data indicate that an eGMS can be safely and effectively used for basal bolus insulin therapy in the hospital setting. Basal bolus insulin therapy is the recommended treatment for non–critically ill patients, however, there has been a lack of clinical inertia due to many barriers with implementing these regimens as a standard of care in today’s hospitals. Some of the challenges include a lack of experts such as endocrinologists, diabetologists, and certified diabetes educators, which can lead to in education deficits and knowledge gaps. Others include confusion with complex order sets as well as workflow difficulties, specifically regarding coordination of the timing of meal tray delivery, blood glucose checks and insulin administration. Use of an eGMS to standardize ordering processes and automate nursing workflow may help clinicians combat many of these challenges.

In basal/bolus insulin order sets, for example, rapid acting insulin analogues have different indications, which can lead to confusion among nursing staff relative to insulin administration. In the study, the eGMS demonstrated the potential to reduce confusion and potential for error through a series of on-screen prompts to ensure the correct prandial and correction doses are calculated. The nurse simply administered the insulin as recommended. The PMBB orders used in the BGM and AGM groups had rapid acting insulin is prescribed for both prandial and correctional insulin dosing and scheduled during meal times. The administration instructions state to “hold prandial insulin if patient is not eating” and “give correction insulin per scale if above glycemic target.” Nurses must understand which insulin is appropriate to give, and then perform a calculation at the bedside to add up the total insulin dose given to the patient, which can result in mathematical errors.

The eGMS provides recommendations for full, partial, or held insulin doses through a series of on-screen prompts to the nurse regarding the patient’s nutritional status. For example, patients who are made NPO for a procedure or surgery will automatically have prandial insulin held by the glycemic management system, while correction insulin may be recommended if the patient is above the glycemic target. In the PMBB there were no instructions for patients who have poor appetites and may be eating partial meals. If instructions had been included, they would have the potential to be complex and would require hand calculation by the nurse at the bedside.

Others challenges with basal/bolus insulin therapies are related to insulin titration, which include missed opportunities to titrate up or down based on glycemic target ranges or confusion with insulin titration calculations. Overbasalization of patients may be occurring in hospitals today more than is recognized, and can contribute to hypoglycemia in the inpatient setting overbasalization can result in low fasting blood glucose levels, and ultimately hypoglycemia. In addition, if basal insulin is not titrated effectively, patients who are eating may experience hypoglycemia if they are suddenly made NPO or have other alterations in eating patters during the inpatient stay even if the prandial insulin is held.1,2,17 These errors with basal insulin titration contribute to the fear of inpatient hypoglycemia among clinicians today and can lead to inappropriate holding of basal insulin, despite instructions to “administer basal insulin even if the patient is not eating.”17

eGMSs are able to fully automate insulin titration without daily ordering intervention from providers. Basal insulin is automatically titrated to a prescribed glucose target based on fasting blood glucose levels, preventing overbasalization of patients. In addition to recommending full, partial, or held insulin doses through a series of on-screen prompts to the nurse regarding the patient’s nutritional status, computerized glycemic management systems will titrate prandial doses to prescribed glycemic targets as well. As with basal insulin titrations, these adjustments to prandial insulin doses are fully automated and therefore do not require daily provider intervention.

One of the main limitations of this study is the retrospective nature of the analysis, which did not allow for unequivocal evidence of superiority of eGMS to PMBB insulin. The crossover design did allow for a direct comparison of provider versus computerized management of basal bolus insulin doses for the same patient. Further prospective studies are needed to determine conclusively the efficacy and safety of eGMS versus provider-managed SubQ insulin.

Conclusion

This retrospective crossover analysis investigated the efficacy and safety of glycemic control for patients who were treated on SubQ basal bolus insulin managed by a provider and before and/or after managed by an eGMS. The complexity of basal/bolus order sets coupled with a lack of diabetes expertise in hospitals is a compounding factor that can result in confusion and ultimately poor patient outcomes and even medical errors. Our study indicates that patients managed with eGMS had a significant reduction in hypoglycemic events while maintaining an average blood glucose level during treatment less than 180 mg/dL and achieving 24-42% more patients in the prescribed glucose target range of 140-180 mg/dL. The same patients that were managed by providers before and/or after eGMS did not have an average blood glucose during treatment less than 180 mg/dL and also had significantly higher hypoglycemia. There is growing evidence that adoption of computer-based algorithms, if implemented safely, could potentially reduce the need for personnel, minimize titration inertia and reduce variation in care in this arena.16,17

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ADA, American Diabetes Association; AGM, after Glucommander; BG, blood glucose; BGM, before Glucommander; BMI, body mass index; DGM, during Glucommander; eGMS, Electronic Glycemic Management System; GM, Glucommander; ICU, intensive care unit; NPO, nil per os; IV, intravenous; PMBB, provider-managed basal bolus; SubQ, subcutaneous.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: RSM, ABH, MM, and RB are full-time employees of Glytec.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Cefalu WT, Bakris G, Blonde L, et al. Clinical considerations for use of initial combination therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(suppl 1):S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moghissi E, Korytkowski M, DiNardo M, et al. Consensus: inpatient hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(4):353-369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korytkowski MT, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non–critical care setting: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(1):16-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Zisman A, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 Trial). Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2181-2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 Surgery). Diabetes Care. 2011;34:256-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turchin A, Matheny ME, Shubina M, et al. Hypoglycemia and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes hospitalized in the general ward. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1153-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirsch IB. Sliding scale insulin—time to stop sliding. JAMA. 2009;301:213-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Umpierrez G, Palacio A, Smiley D. Sliding scale insulin use: myth or insanity? Am J Med. 2007;120(7):563-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maynard G. Best practices for interdisciplinary care management. SHM survey. Diabetes Spectr. 2014. August 2014;27(3):197-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tanenberg R. Seven-year outcome data from a computer-guided inpatient glucose management system. Paper presented at: 73rd ADA Scientific Sessions; 2013; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eppley M, Serr G. Hyperglycemia in hospital: the pharmacist’s role. Hosp Pharm. 2009;44(7):594-603. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris C, Greene D. Guardian-of-glucose. Nurs Manage. 2009;40(5):18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Juneja R, Roudebush C, Kumar N, Macy A, Golas A, Wall D. Utilization of a computerized intravenous insulin infusion program to control blood glucose in the intensive care unit. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9(3):232-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Juneja R, Roudebush C, Nasraway S, et al. Computerized intensive insulin dosing can mitigate hypoglycemia achieve tight glycemic control when glucose measurement is performed frequently and on time. Crit Care. 2009;13(5):R163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Umpierrez G, Pasque F, Peng L, et al. Randomized controlled tiral of intensive versus conservative glucose control in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: GLUCO-CABG Trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1665-1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aloi J, Mulla C, Ullal J, Lieb D. Improvement in inpatient glycemic care: pathways to quality. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(4):18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mulla C, Lieb D, McFarland R, Aloi J. Tides of change: improving glucometrics in a large multihospital health care system.J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9(3):602-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neubauer KM, Mader JK, Holl B, et al. Standardized glycemic management with a computerized workflow and decision support system for hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes on different wards. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17:685-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davidson P, Bode B, Clarke J, Hebblewhite H. A nursing-directed computer program, which re-adjust SubQ multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin, lowers mean BG in hospital patients. Paper presented at: AACE; 2012; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mabrey M, Ullal J, McFarland R, et al. eGlycemic management system safely achieves prescribed glycemic targets with a low incidence of hypoglycemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction in the hospital. Paper presented at: AACE; 2015; Nashville, TN. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aloi J, Chidester P, Ullal J, Henderson A, McFarland R. eGlycemic management system safely maintains glycemic targets with a low incidence of hypoglycemia for non-diabetic CV surgical patients in the hospital setting. Paper presented at: AACE; 2015; Nashville, TN. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aloi J, Booth R, McFarland R, Ulla J, Mabrey M. Use of eGlycemic management system safely achieves optimal SubQ glycemic control with low hypoglycemia in patients without diabetes. Paper presented at: ADA; 2015; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ullal J, Mabrey M, Henderson A, McFarland R, Booth R, Aloi J. Use of eGlycemic management system provides safe and effective glycemic control of stroke patients requiring SubQ insulin in the hospital setting. Paper presented at: DTM; 2015; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mabrey M, Aloi J, Chidester P, Ullal J, Henderson A, McFarland R. Use of eGlycemic management solution by Glytec to identify and improve glycemic care for SHF patients. Paper presented at: IHDM; 2015; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]