ABSTRACT

Viruses use the cellular machinery of their hosts for replication. It has therefore been proposed that the nucleotide and dinucleotide compositions of viruses should match those of their host species. If this is upheld, it may then be possible to use dinucleotide composition to predict the true host species of viruses sampled in metagenomic surveys. However, it is also clear that different taxonomic groups of viruses tend to have distinctive patterns of dinucleotide composition that may be independent of host species. To determine the relative strength of the effect of host versus virus family in shaping dinucleotide composition, we performed a comparative analysis of 20 RNA virus families from 15 host groupings, spanning two animal phyla and more than 900 virus species. In particular, we determined the odds ratios for the 16 possible dinucleotides and performed a discriminant analysis to evaluate the capability of virus dinucleotide composition to predict the correct virus family or host taxon from which it was isolated. Notably, while 81% of the data analyzed here were predicted to the correct virus family, only 62% of these data were predicted to their correct subphylum/class host and a mere 32% to their correct mammalian order. Similarly, dinucleotide composition has a weak predictive power for different hosts within individual virus families. We therefore conclude that dinucleotide composition is generally uniform within a virus family but less well reflects that of its host species. This has obvious implications for attempts to accurately predict host species from virus genome sequences alone.

IMPORTANCE Determining the processes that shape virus genomes is central to understanding virus evolution and emergence. One question of particular importance is why nucleotide and dinucleotide frequencies differ so markedly between viruses. In particular, it is currently unclear whether host species or virus family has the biggest impact on dinucleotide frequencies and whether dinucleotide composition can be used to accurately predict host species. Using a comparative analysis, we show that dinucleotide composition has a strong phylogenetic association across different RNA virus families, such that dinucleotide composition can predict the family from which a virus sequence has been isolated. Conversely, dinucleotide composition has a poorer predictive power for the different host species within a virus family and across different virus families, indicating that the host has a relatively small impact on the dinucleotide composition of a virus genome.

KEYWORDS: dinucleotide bias, evolution

INTRODUCTION

The nucleotide composition of genomes is not uniform. This is clearly manifest in the variation in dinucleotide frequencies between organisms, which do not match the frequencies predicted from overall nucleotide composition. Most notably, the frequency of the TpA dinucleotide is suppressed across all animal genomes, with the exception of mitochondrial DNA, while the CpG dinucleotide is suppressed in most vertebrates including mitochondrial genomes (1, 2). Such dinucleotide biases evidently have a phylogenetic component. For example, CpG is underrepresented in most eukaryotes but not in invertebrates or prokaryotes (3), and the frequency of this dinucleotide is seemingly higher in fish than in humans (4). Importantly, these differences in dinucleotide bias can be thought of as a distinctive genomic “signature” of specific taxonomic groups, in turn providing important information on the mechanisms of molecular evolution (5).

The expected dinucleotide frequency in a sequence is simply the product of the corresponding nucleotide frequencies, such that in an unbiased sequence the observed dinucleotide frequency equals the expected frequency and the odds ratio (observed/expected) is 1. If the odds ratio is lower or higher than 1, the corresponding dinucleotide can be regarded as either under- or overrepresented, respectively (3). A variety of theories have been put forward to explain common dinucleotide biases. For example, it has been suggested that the underrepresentation of TpA may be a consequence of avoiding mutations that lead to stop codons, as two of the three stop codons start with a TpA dinucleotide. In addition, TpA is part of the TATA box, so the uncontrolled occurrence of TpA could lead to incorrect gene regulation (2, 6). TpA suppression is also stronger in coding than in noncoding DNA sequences, likely because the transcribed counterpart UpA is susceptible to RNase cleavage that may destabilize the RNA molecule (7). The CpG suppression in vertebrates is thought to be partially due to cytosine methylation (1, 3, 8), although it may also be constrained by other aspects of DNA conformation, such as secondary structure and dinucleotide stacking energies (4, 9–12).

Similar dinucleotide biases are found in viral genomes, with major differences among viral species. For example, while the frequency of CpG is in the normal range in large DNA viruses, small DNA viruses have a low CpG content. This is most extreme in the case of polyomaviruses, which show a CpG odds ratio of approximately 0.2 (10, 13). Similarly, most RNA viruses show an underrepresentation of CpG, with a notable exception being rubella virus, which has an exceptionally high GC content (70%) and hence a normal CpG odds ratio (14).

A variety of theories have been put forward to explain the variation in dinucleotide biases among RNA viruses. Given their potential impact on fitness, dinucleotide composition may represent a specific form of host adaptation. This is supported by several studies showing that the dinucleotide composition of viruses generally matches that of their hosts (15–17). For example, the base composition of iridoviruses matches that of the host tRNA population (18), and it was recently shown that host-induced methylation is the major factor shaping CpG depletion patterns in human and simian immunodeficiency viruses (19). In addition, the dinucleotide frequency has been shown to change following cross-species transmission events, such as the marked decrease in CpG frequency as influenza A virus jumps from birds to humans (20, 21). Studies of influenza viruses and picornaviruses indicate that the innate immune response might recognize RNA-specific CpG motifs, such that the suppression of CpG in viruses could assist immune evasion (22–24). In contrast, other studies have suggested that dinucleotide bias in viruses simply reflects background mutation pressure. For instance, CpG suppression has been linked to overall GC content independent of position within codons, which is compatible with the impact of neutral mutation pressure (25, 26).

Given that viruses are dependent on the hosts for replication, utilizing the cellular apparatus for translation, it might be expected that viruses should have the same overall nucleotide composition as their hosts and hence exhibit similar dinucleotide biases (27). Importantly, if the dinucleotide composition of a virus matches that of its host, then it could comprise a simple means to predict the true hosts for viral sequences generated in the increasing number of metagenomic studies. As a case in point, Kapoor et al. used the dinucleotide composition of uncharacterized picorna-like viral sequences isolated from a human to determine the true viral host, concluding that these were in fact derived from arthropods (28). Biases in dinucleotide frequency also directly effect codon usage, in turn influencing the efficiency of viral replication (29, 30). Indeed, experimentally changing codon preferences in virus genomes can have a major impact on the efficiency of replication in a host, a strategy that has been exploited as a means of virus attenuation (31–35). Therefore, if viruses that infect the same hosts have similar dinucleotide compositions (irrespective of their virus family), then viruses that infect multiple hosts, such as those that are transmitted by arthropod vectors, should in theory exhibit weaker dinucleotide bias (26).

While considerable attention has been directed toward revealing the extent to which biases in nucleotide composition and codon usage in RNA viruses are shaped by the host, far less attention has been given to the impact of virus phylogeny (i.e., evolutionary history) on dinucleotide usage (36–38). In particular, it is unclear whether viruses that are from the same family but infect different host species exhibit a nucleotide composition that better reflects their viral phylogenetic history (i.e., their historical contingency) or the host that they infect. A strong association with virus phylogeny may limit the ability to accurately predict host species from virus dinucleotide composition alone. To address this question, we analyzed viral sequences from 20 families of animal RNA viruses isolated from different vertebrate and arthropod hosts and evaluated which of two factors, “host” or “family,” had the larger influence in shaping virus dinucleotide composition. In addition, we estimated the extent to which the dinucleotide composition of a virus sequence can be used to predict its virus family and virus-host association.

RESULTS

RNA viruses exhibit substantial variation in dinucleotide composition.

Our final data set included 10 positive-sense single-stranded RNA [ssRNA(+)] and eight negative-sense single-stranded RNA [ssRNA(−)] virus families, as well as two families of double-stranded RNA virus, all of which infect animal hosts. Importantly, we excluded virus sequences for which the host association was poorly described or that were isolated from dead-end hosts in which there is no onwards transmission. The Bunyaviridae had the largest data size (221 component data sets) and the Filoviridae the smallest, with only six data sets.

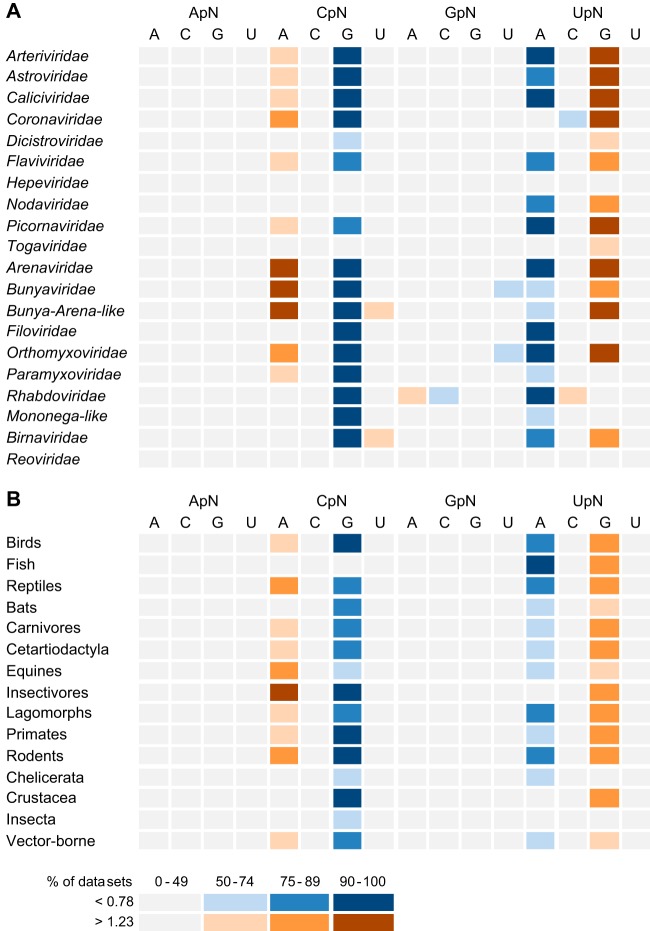

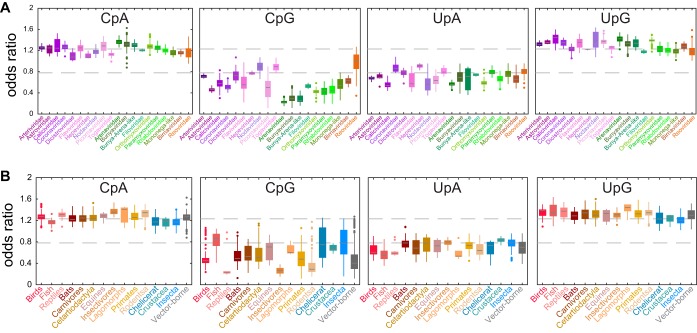

We first compared the odds ratios for the 16 dinucleotides across the different virus families. Karlin and Mrazek showed that dinucleotide odds ratios below 0.78 can be regarded as indicating underrepresented dinucleotides, whereas values above 1.23 indicate overrepresented dinucleotides (3). Figure 1A provides a schematic view of the proportion of data sets per virus family that show an over- or underrepresentation of the 16 dinucleotide odds ratios. This shows that the dinucleotides ApA, ApC, ApG, and ApU, as well as CpC, GpG, and UpU, have no overall bias in any of the virus families studied here, as the odds ratios for these dinucleotides are within the normal range for at least 50% of the component data sets. In contrast, CpG and UpA are largely underrepresented, while CpA and UpG are largely overrepresented across the data sets studied here (as was also the case for the different host categories [Fig. 1B, see below]). However, there are important differences between virus families. Figure 2A shows the distribution of these four dinucleotide odds ratios across the virus families. This reveals that CpG is underrepresented in all ssRNA(−) virus families, as well as in the Arteri-, Astro-, Calici-, Corona-, Dicistro-, Flavi-, and Picornaviridae families of ssRNA(+) viruses, while the three remaining families of ssRNA(+) virus (Hepe-, Noda-, and Togaviridae) overall have normal odds ratios for this dinucleotide. In the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) viruses, CpG is underrepresented in the Birnaviridae but not in the Reoviridae. Also of note is that the Coronaviridae have a low odds ratio for UpC and a normal value for UpA, while most other families have an underrepresentation of UpA (Fig. 1A). In addition, while most RNA viruses have an overrepresentation of UpG, the Hepeviridae, Filoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, mononega-like viruses, and Reoviridae generally have normal odds ratios for this dinucleotide. Interestingly, the Hepeviridae and the Reoviridae have the most homogenous dinucleotide composition of the virus families studied here, as none of the 16 dinucleotides odds ratios are biased (although individual data sets might show some under- or overrepresentation of one or two dinucleotides [Fig. 2A]).

FIG 1.

Schematic depiction of the dinucleotide odds ratio bias across the animal RNA virus data sets analyzed here. The figure shows both dinucleotide underrepresentation (cool colors) and overrepresentation (warm colors). The degree of under- or overrepresentation is depicted by the different shadings: light, 50 to 74% of component virus data sets; medium, 75 to 89%; dark, 90 to 100%. (A) Virus families; (B) host categories.

FIG 2.

Dinucleotide odds ratios. The figure shows observed over expected ratios (odds ratios) from the aggregated set of 1,024 data sets for the four dinucleotides CpA, CpG, UpA, and UpG. Dinucleotides are regarded as underrepresented if the odds ratio is below 0.78 and overrepresented if it is over 1.23 (dashed lines). Boxplots show the 25 to 75% data range and the median, whiskers indicate the 99.3% data coverage, and outliers are shown as dots. (A) ssRNA(+) viruses are in purple shades (Arteriviridae, Astroviridae, Caliciviridae, Coronaviridae, Dicistroviridae, Flaviviridae, Hepeviridae, Nodaviridae, Picornaviridae, and Togaviridae), ssRNA(−) viruses are in green shades (Arenaviridae, Bunyaviridae, bunya-arena-like, Filoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, and mononega-like), and dsRNA viruses are in red shades (Birnaviridae and Reoviridae). (B) Data sets from nonmammalian vertebrates are shown in pink colors (“Birds,” “Fish,” and “Reptiles”), those from mammalian hosts are shown in brown colors (“Bats,” “Carnivores,” “Cetartiodactyla,” “Equines,” “Insectivores,” “Lagomorphs,” “Primates,” and “Rodents”), those from arthropod hosts are shown in blue colors (“Chelicerata,” “Crustacea,” and “Insecta”), and vector-borne viruses were grouped into their own category and shown in gray.

Using the same data sets, we compared the dinucleotide odds ratios among the different host categories (Fig. 1B). The virus sequences studied here were isolated from 15 different host categories, including mammals, other vertebrates, and arthropods (where there is no known involvement of vertebrate hosts in transmission). In addition, five of the virus families contained viruses transmitted by arthropod vectors (i.e., the host category “Vector-borne”). Similar to the results by virus family, the odds ratios of the ApA, ApC, ApG, and ApU dinucleotides as well as those of the four GpN dinucleotides were generally normal across all host categories, as were CpC, CpU, UpC, and UpU (Fig. 1B). In contrast, and as expected given the results by virus family, CpG and UpA are underrepresented in most host groups, while CpA and UpG are usually overrepresented. Interesting exceptions are CpG, which is in the normal range in “Fish,” UpA, which is unbiased in “Insectivores,” “Crustacea,” and “Insecta” (although 49% of the “Insecta” data sets show an underrepresentation of UpA [Fig. 2B]), and UpG, which is in the normal range in “Chelicerata” and “Insecta” (Fig. 2B). The CpA odds ratios were even more heterogeneous, as this dinucleotide is unbiased in “Fish,” “Bats,” “Chelicerata,” “Crustacea,” and “Insecta” but is overrepresented in the other host categories.

Virus dinucleotide composition shows a stronger association with virus family than with host.

We next investigated whether biases in dinucleotide odds ratio could be used as a predictive marker of virus family or host. For this we used a linear discriminant analysis, where the odds ratios of all 16 dinucleotides were used to predict the data sets into either viral families or host categories. We compared the true-positive prediction rate using the dinucleotide odds ratios to a random proportional representation based model (which estimates the baseline true prediction rate without dinucleotide information) to quantify the increase in predictive power offered by dinucleotide odds ratios. We also calculated the correctly predicted data sets (sensitivity) for each category separately and compared this to the false-discovery rate (FDR), which is the percentage of falsely predicted data sets. The dinucleotide odds ratios can be considered useful for prediction if the model with their inclusion shows a large increase in predictive power from the baseline random model and also minimizes the FDR. Here, we use the values 80% for sensitivity rate and 20% for the FDR as a threshold for “good” predictive power.

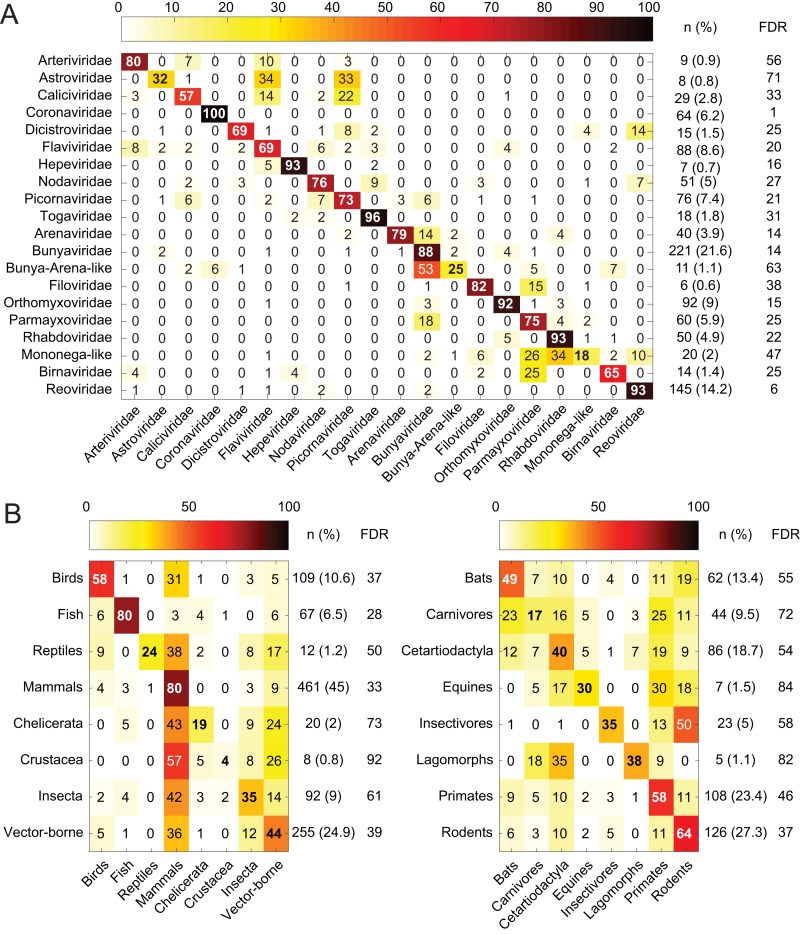

These results show that with inclusion of dinucleotide odds ratios the model predicts 81% of the data to the correct virus family, a very large improvement to the value of 10% observed in the baseline random model. Figure 3A shows the confusion plot of the discriminant analysis as a heat map for each individual virus family (sensitivity) (for example, 73% of the data from the Picornaviridae were correctly assigned to this family) as well as the FDR, which in this case shows that 21% of the data predicted to belong to the Picornaviridae were not from this family. It also shows how many data sets were predicted into a false virus family. For example, 34% of the Astroviridae were incorrectly predicted into the Flaviviridae and 33% into the Picornaviridae. From this analysis, the strongest sensitivity was observed in the case of the Coronaviridae (100% sensitivity and 1% FDR), while the lowest sensitivity rate was observed in the diverse mononega-like group of viruses, for which only 18% of the data sets were correctly predicted (47% FDR). Also of note was that only 25% of the bunya-arena-like viruses were predicted correctly, although 53% of these data sets were falsely predicted into the closely related Bunyaviridae. Overall, the sensitivity was high (≥80%) and the FDR was low (≤20%) in five of the virus families analyzed here, i.e., the Corona-, Hepe-, Bunya-, Orthomyxo-, and Reoviridae. The Hepeviridae had a very high sensitivity rate of 93%, which is striking as only 0.7% of the aggregated data sets belong to this virus family. The other two families with similar data set sizes had poor prediction rates: the Arteriviridae had a sensitivity rate of 80% but an FDR of 56%, while the Astroviridae had a higher FDR than sensitivity rate.

FIG 3.

Confusion plots for the discriminant analysis of dinucleotide odds ratios across virus families and virus hosts. The heat maps show the mean percentages of data sets that were predicted into each category. Rows represent the true categories and columns the predicted categories. The correctly predicted sensitivities for each category are shown in bold and positioned along the diagonal. Dark red and black indicate high sensitivity rates and yellow and white low sensitivity rates. On the right side of the heat maps the number of data sets per category (n) and the false-discovery rate (FDR) are indicated. (A) Heat map for the virus families. Overall, 81% of the data were predicted correctly, compared to 10% with the baseline random model. (B) Heat map for the virus host separated by subphylum/class (left) and mammalian orders (right). For the analysis at the subphylum/class level, 62% of the data were predicted correctly overall, compared to 29% with the baseline random model. In the case of the mammalian orders, 32% of the data were predicted correctly, compared to 12% with the baseline random model.

For the virus hosts, we first compared the two different phyla present in the data. While the model largely failed to predict the “Arthropoda” (45% sensitivity), it seemingly performed well for the “Chordata,” with a 95% sensitivity rate. However, the model including the dinucleotide odds ratios had an improvement of only 13% compared to the random model, i.e., 87% compared to 74%. Hence, the high sensitivity rate for the “Chordata” may largely reflect the unequal data set sizes between these groups, with 84% of the sequences from the “Chordata” and only 16% from the “Arthropoda.”

We next performed the same analysis at the level of animal subphylum/class, that is, by analyzing the categories “Birds,” “Fish,” “Reptiles,” “Mammals,” “Chelicerata,” “Crustacea,” “Insecta,” and “Vector-borne” (Fig. 3B, left plot). In this case, dinucleotide odds ratios correctly predicted the host subphylum/class group 62% of the time, representing an increase of 33% compared to the random model. Only the host categories “Fish” and “Mammals” had a sensitivity rate of at least 80%, and the FDR was also relatively high in both these cases (28% and 33%, respectively). Notably, many of the data sets from the six categories were falsely predicted into the category “Mammals,” so that dinucleotide composition cannot always be considered characteristic for these hosts. “Crustacea” showed the worst sensitivity rate, with only 4% of the data sets predicted correctly and an FDR of 92%. Finally, at the most precise host taxonomic level, we considered individual orders of mammals separately, i.e., “Bats,” “Carnivores,” “Cetartiodactyla,” “Equines,” “Insectivores,” “Lagomorphs,” “Primates,” and “Rodents” (Fig. 3B, right plot). Strikingly, only 32% of the mammalian hosts were predicted correctly using dinucleotide odds ratios, an increase of 20% compared to the random model. In addition, none of the eight mammalian host categories had a high sensitivity rate, with values ranging from 17% to 64%, and six of the mammalian categories (as well as “Reptiles,” “Chelicerata,” Crustacea,” and “Insecta”) had an FDR higher than the true positive prediction rate, indicating the poor predictive power of dinucleotide odds ratios in these cases.

A canonical plot for the eight subphylum/class host categories is shown in Fig. 4. The three categories of arthropod hosts exhibit considerable overlap, whereas the “Mammals,” “Birds,” and “Fish” data sets present more distinctive patterns. Notably, the “Vector-borne” data sets overlap those in other taxonomic groups, particularly “Mammals.” Indeed, because vector-borne viruses infect a range of hosts, such that it is not a “host-specific” category per se, it is possible that its inclusion has lowered the predictive power of odds ratios. However, the removal of vector-borne viruses from this analysis did not improve sensitivity rates by a meaningful amount, and there was almost no increase in predictive power (34%, compared to 33% with the vector-borne viruses included).

FIG 4.

Canonical score plot of the host categories by class. The figure shows a scatterplot of the two linear discriminant functions that explain the largest amount of variability from the linear discriminant analysis (50% and 19% for LD1 and LD2, respectively).

Weak association between dinucleotide composition and host species within a virus family.

We also determined whether the dinucleotide composition differs between different hosts within a single virus family. To do this, we chose those virus families with overlapping host ranges and compared the dinucleotide odds ratios between the different hosts within each of these families. Accordingly, we performed a discriminant analysis for five families that do not include vector-borne data sets (Caliciviridae, Coronaviridae, Picornaviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, and Paramyxoviridae) and that share the host categories “Birds,” “Carnivores,” “Cetartiodactyla,” “Primates,” and “Rodents” (Table 1). The overall prediction rate was poor for hosts in all virus families, and the sensitivity for the individual categories was low for most hosts, with the exception of “Birds.” This host category had a high sensitivity in the Orthomyxoviridae (86% and FDR of 13%), although the majority of this data set comprised avian influenza viruses. Likewise, “Birds” showed a high sensitivity rate of 94% in the Coronaviridae (FDR, 27%), although only 6.2% of the sequences in this family came from avian hosts. However, the overall true positive prediction rate increased by only 6% and 33% compared to the random model for the Orthomyxoviridae and Coronaviridae, respectively. None of the other host categories had a high sensitivity rate, and the model performed poorly in predicting the correct host category for any host in the Caliciviridae, Picornaviridae, and Paramyxoviridae.

TABLE 1.

Discriminant analysis of dinucleotide odds ratios per host across different viral familiesa

| Virus family and host | Number in data set (%) | True positive prediction rate (sensitivity) | False discovery rate (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Families without vector-borne species | |||

| Caliciviridae | |||

| Carnivores | 9 (31) | 36 | 54 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 5 (17.2) | 18 | 82 |

| Lagomorphs | 4 (13.8) | 53 | 51 |

| Primates | 8 (27.6) | 58 | 42 |

| Rodents | 3 (10.3) | 87 | 30 |

| Overall correct, 43% (random model, 20%) | |||

| Coronaviridae | |||

| Birds | 4 (6.2) | 94 | 27 |

| Bats | 24 (37.5) | 53 | 29 |

| Carnivores | 7 (10.9) | 42 | 62 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 17 (26.6) | 78 | 31 |

| Primates | 7 (10.9) | 23 | 77 |

| Rodents | 5 (7.8) | 59 | 26 |

| Overall correct, 57% (random model, 24%) | |||

| Picornaviridae | |||

| Birds | 2 (2.6) | 31 | 87 |

| Carnivores | 5 (6.6) | 25 | 76 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 27 (35.5) | 63 | 29 |

| Equines | 1 (1.3) | NAb | NA |

| Primates | 33 (43.4) | 76 | 25 |

| Rodents | 8 (10.5) | 20 | 79 |

| Overall correct, 59% (random model, 32%) | |||

| Orthomyxoviridae | |||

| Birds | 73 (79.3) | 86 | 13 |

| Fish | 1 (1.1) | NA | NA |

| Carnivores | 6 (6.5) | 17 | 87 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 6 (6.5) | 10 | 92 |

| Equines | 2 (2.2) | 4 | 97 |

| Primates | 4 (4.3) | 14 | 84 |

| Overall correct, 70% (random model, 64%) | |||

| Paramyxoviridae | |||

| Birds | 12 (20) | 50 | 29 |

| Bats | 12 (20) | 59 | 48 |

| Carnivores | 5 (8.3) | 14 | 91 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 7 (11.7) | 24 | 71 |

| Primates | 18 (30) | 48 | 50 |

| Rodents | 6 (10) | 29 | 70 |

| Overall correct, 42% (random model, 18%) | |||

| With vector-borne species | |||

| Bunyaviridae | |||

| Bats | 3 (1.4) | NA | NA |

| Insectivores | 23 (10.4) | 33 | 57 |

| Rodents | 64 (29) | 75 | 26 |

| Vector borne | 131 (59.3) | 91 | 13 |

| Overall correct, 79% (random model, 44%) | |||

| Flaviviridae | |||

| Bats | 3 (3.3) | 32 | 79 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 8 (8.7) | 82 | 30 |

| Primates | 10 (10.9) | 79 | 34 |

| Rodents | 6 (6.5) | 38 | 39 |

| Chelicerata | 5 (5.4) | 16 | 81 |

| Insecta | 18 (19.6) | 59 | 21 |

| Vector borne | 42 (45.7) | 99 | 7 |

| Overall correct, 76% (random model, 27%) | |||

| Reoviridae | |||

| Birds | 11 (7.6) | 19 | 81 |

| Fish | 9 (6.2) | 26 | 68 |

| Reptiles | 2 (1.4) | 3 | 98 |

| Bats | 10 (6.9) | 26 | 70 |

| Carnivores | 7 (4.8) | 29 | 77 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 13 (9) | 18 | 83 |

| Equines | 3 (2.1) | 29 | 77 |

| Primates | 8 (5.5) | 29 | 41 |

| Rodents | 6 (4.1) | 7 | 94 |

| Chelicerata | 5 (3.4) | 58 | 37 |

| Crustacea | 3 (2.1) | 56 | 52 |

| Insecta | 26 (17.9) | 26 | 61 |

| Vector borne | 42 (29) | 65 | 46 |

| Overall correct, 34% (random model, 14%) | |||

| Rhabdoviridae | |||

| Fish | 9 (18) | 64 | 29 |

| Bats | 9 (18) | 64 | 50 |

| Carnivores | 3 (6) | 24 | 86 |

| Insecta | 3 (6) | 25 | 75 |

| Vector borne | 26 (52) | 69 | 18 |

| Overall correct, 60% (random model, 33%) | |||

| Togaviridae | |||

| Fish | 3 (16.7) | 86 | 49 |

| Primates | 1 (5.6) | NA | NA |

| Vector borne | 14 (77.8) | 79 | 9 |

| Overall correct, 75% (random model, 62%) |

The table shows how many data sets were assigned correctly to their host according to their dinucleotide odds ratios. The overall correct prediction rate and the results using a random model are also shown.

NA, not applicable due to small sample size.

Finally, we used the discriminant analysis to predict the virus host for the five virus families that are commonly transmitted by arthropod vectors (Bunyaviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Flaviviridae, Reoviridae, and Togaviridae) (Table 1). Here, the Flaviviridae and Bunyaviridae had an excellent sensitivity rate for the host category “Vector-borne,” as 99% and 91% of the corresponding data sets were predicted to the correct virus family (FDRs of 7% and 13%, respectively), although the other host categories exhibited a low sensitivity rate in these two families. The Togaviridae also show the highest sensitivity for the category “Vector-borne” (79%; FDR, 9%). None of the host categories had a high sensitivity rate in the Rhabdoviridae and Reoviridae. However, it is noteworthy that the overall positive prediction rates increased only marginally compared to those for the random model in all five of these families of vector-borne viruses, with the best result in the Flaviviridae, which showed a true positive prediction rate of 76%, compared to 27% for the random model (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Animal genomes are biased in their dinucleotide composition, and the strong underrepresentation of CpG and TpA dinucleotides is particularly well documented (1). Viral genomes seemingly exhibit similar biases, as, for example, CpG and UpA underrepresentation occurs in most single-stranded RNA viruses and small DNA viruses (10, 14). While it is often assumed that viruses simply follow the dinucleotide bias patterns of their host (15, 16), the true impact of the host taxon has been rarely studied. Here, we compared the dinucleotide odds ratios of a diverse set of RNA viruses to determine whether the specific host species a virus infects or the family to which a virus belongs is the more important factor in shaping viral dinucleotide composition.

We find that the dinucleotides CpG and UpA are generally underrepresented in 16 and 15 of the 20 virus families examined here, respectively, while CpA and UpG are overrepresented in 11 and 14 virus families, respectively. Previous studies suggested that the overrepresentation of CpA and UpG is a compensation for the underrepresentation of CpG and UpA (14, 39), although we observed that these do not always go hand in hand, as in the case of Coronaviridae (Fig. 1A). Perhaps of most note is the underrepresentation of CpG, which was thought to be less common in both invertebrate genomes (3) and invertebrate-specific viruses (17, 40, 41) than in vertebrates. It is possible that the underrepresentation of CpG in vertebrate viruses in part reflects selection to evade components of the innate immune response that are able to recognize CpG-rich sequences, such as Toll-like receptor-mediated recognition pathways (42). In contrast, antiviral responses in invertebrates are more often mediated by RNA interference, which would not predict selection for low CpG levels (43, 44). Indeed, we see that some of the “Insecta”-specific and “Chelicerata”-specific viruses have normal CpG odds ratios. However, there was strong CpG suppression in other arthropod-specific viruses. For example, some of the newly discovered bunya-arena-like and mononega-like viruses isolated from “Chelicerata” and “Insecta” have the lowest CpG odds ratios in our data (values as low as 0.2), and all data sets from “Crustacea” show an underrepresentation of CpG. Interestingly, “Fish” is the only host category that exhibits an overall unbiased CpG odds ratio, although this largely reflects the fact that 54% of the “Fish” viruses are from Nodaviridae, which has a normal CpG odds ratio.

Previous studies proposed a correlation between overall GC content and CpG dinucleotide suppression, such that genomes with high GC content have a normal CpG ratio (14, 45). We see here that the Hepeviridae and Nodaviridae, which have the highest GC contents (mean 55.6% and 54.1%, respectively), indeed have a normal CpG odds ratio. However, the opposite is not necessarily true; that is, sequences with normal or low GC contents do not necessarily have low CpG odds ratios. For example, the Arenaviridae, Bunyaviridae, and bunya-arena-like viruses have the lowest median CpG dinucleotide odds ratios (0.2, 0.29, and 0.25, respectively), yet their GC contents are not the lowest among the viruses analyzed here (median values, 39.5% to 42.3%). Likewise, while the Arteri-, Calici-, and Flaviviridae have a GC content similar to that of the Togaviridae (median of 52% for all families), only the first two virus families exhibit a clear CpG dinucleotide underrepresentation. Hence, GC content alone does not explain the differences in CpG bias between different families. It is therefore likely that dinucleotide composition also reflects aspects of genome secondary structure, such as the stem-loop structures required for replication that are often shared among viruses within a family (1, 14, 46).

While the results of the individual dinucleotide odds ratios are complex, dinucleotide composition is generally a good predictor of the family to which a specific virus belongs, as the linear discriminant model predicted 81% of the data to the correct virus family, a large improvement from the baseline random model. Furthermore, the sensitivities for the individual families were high compared to the false-discovery rates. Of most note was that a sensitivity of 100% was achieved for the Coronaviridae, implying that the dinucleotide composition for this virus family is unique. Indeed, coronaviruses have an atypical nucleotide bias characterized by low levels of C and high levels of U nucleotides, most likely due to cytosine deamination (38, 47, 48), and the Coronaviridae are the only family that show an underrepresentation of UpC but not UpA.

In contrast, the discriminant analysis shows that dinucleotide frequencies have a relatively poor association with virus hosts, as only 62% of the data were allocated to the true host subphylum/class, an increase in predictive power of only 33% compared to the random model. Hence, the dinucleotide odds ratios from sequences isolated from a specific host are not always distinct enough to separate them from other hosts. This is true for vertebrate and invertebrate hosts as well as for vector-borne viruses; indeed, for many host categories, the false-discovery rate was higher than the sensitivity rate. However, it was also the case that there were important differences between host groups that to some extent reflect taxonomic rank. In particular, low sensitivity rates were observed in all lower taxonomic categories, that is, mammalian orders, perhaps reflecting the relative ease with which mammalian viruses are able to cross species boundaries (49). In contrast, deeper divergences and less host jumping facilitate the evolution of more distinctive dinucleotide compositions. Indeed, the combined category “Mammals” had a sensitivity rate of 80%, as did the broad grouping of “Fish.” However, such distinctive dinucleotide compositions were not observed with “Reptiles” (24% sensitivity) and in the three arthropod subphyla, which in turn explains the overall low true-positive prediction power of dinucleotide odds ratios at the level of host subphylum/class.

There was also little evidence for host dependency within individual virus families. The dinucleotide odds ratios improved the true positive prediction rate marginally for all the families analyzed here, and the best result was found for the Flaviviridae, with an increase in predictive power of only 49%. This is surprising, as previous studies have found an association between dinucleotide composition and host. For example, while it was previously shown that codon usage in foot-and-mouth-disease virus in pigs was different from that in other hosts (50), we found that dinucleotide composition fails to reliably predict any host in the Picornaviridae. In contrast, we do find a good positive prediction rate for “Birds” in the Coronaviridae and Orthomyxoviridae, although for the latter it is important to note that “Birds” represented 70% of the data and the overall sensitivity increased by only 6% compared to that of the random model. As well as host dependency, it is possible that dinucleotide biases are also shaped by differences in tissue or cell tropism, particularly as tRNA levels may differ by tissue type (51). Unfortunately, an analysis of the impact of cell tropism on dinucleotide bias was beyond the scope of the current study.

Vector-borne RNA viruses are of special interest. Given their alternation between two very distinctive host types, in might be expected that they will not show a specific host correlation in their dinucleotide bias. However, previous studies have generated conflicting results. For example, it was reported that synonymous codon usage in vector-borne viruses reflected their natural (reservoir) but not dead-end hosts (52). In addition, flaviviruses mimic aspects of the dinucleotide composition of their hosts, such that there is a major difference in dinucleotide composition between vertebrate-specific viruses and invertebrate-specific viruses (41), while a recent study showed that dengue virus exhibits a preference for codon pairs that are present in both humans and mosquitoes (34). However, it has also been suggested that dinucleotide bias in vector-borne viruses is shaped more by mutation pressure than by host adaptation (53). In the case of the Bunyaviridae, Flaviviridae, and Togaviridae, we found that the dinucleotide odds ratios are a good predictor for the host category “Vector-borne,” although this was not true for the Rhabdoviridae and Reoviridae. Likewise, none of the other (non-vector-borne) host groups had a high sensitivity rate in any of these virus families, and the overall prediction rate increase was low in all the virus families analyzed. Moreover, the sensitivity rate of the “Vector-borne” category in comparisons across all the virus families studied here was low. Hence, vector-borne viruses generally do not possess a dinucleotide composition that is distinctive compared to that of non-vector-borne viruses, instead showing greater similarity to viruses of the same family.

Despite some important exceptions, our study shows that viruses that infect the same host taxonomic group can have highly heterogeneous dinucleotide compositions, with viruses of the same virus family generally sharing similar dinucleotide compositions. Hence, the lack of a consistently strong host association might reflect the fact that dinucleotide bias is largely dependent on specific virological factors, such as RNA secondary structure (1, 2). Thus, although it might be possible to use dinucleotide odds ratios to successfully assign a specific virus sequence to a host taxon, particularly those of higher taxonomic rank such as arthropods compared to vertebrates, caution should clearly be exercised when performing such predictions on sequence data alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequence data.

Complete viral genome sequences from RNA viruses were downloaded from NCBI (GenBank) and separated according to virus family and the host species from which they were isolated. For the analyses performed here, we utilized animal viruses only, that is, those isolated from vertebrates or arthropod hosts. Importantly, our study examined dinucleotide compositions at three different host taxonomic levels. The first comprised those hosts that reflect different animal phyla: the Arthropoda and the Chordata. Second, we examined hosts at the level of animal subphylum or class. These were the subphyla Chelicerata, Crustacea, and Hexapoda from the phylum Arthropoda and the classes Aves (birds), Actinopterygii (fish), Reptilia (reptiles), and Mammalia (mammals) from the phylum Chordata. As we have only insect-specific viruses from the Hexapoda, for simplicity they are referred to here as the “Insecta.” Finally, because most of our sequences came from mammals, we also analyzed dinucleotide biases at the level of mammalian orders, namely, “Bats,” “Carnivores,” “Cetartiodactyla,” “Equines” (as equines were the only members of the Perissodactyla available), “Insectivores,” “Lagomorphs,” “Primates,” and “Rodents.” Importantly, all sequences from vector-borne viruses, defined as being passed between vertebrate and invertebrate hosts in a single transmission cycle, were classified into their own host category, “Vector-borne.” We excluded sequences that were isolated from dead-end hosts (i.e., where there is no evidence of onward transmission in that host), as well as all sequences from host categories represented by fewer than five sequences or present in only a single virus family (which led to the exclusion of any data from the Bornaviridae, Iflaviridae, Roniviridae, and Picobirnaviridae). Finally, as some virus data sets were very large (e.g., influenza A virus from primates), we randomly selected 1,000 sequences from each to reduce the data load.

The final data set comprised 29,310 complete genome sequences from 20 families of animal RNA viruses: Arteriviridae, Astroviridae, Caliciviridae, Coronaviridae, Dicistroviridae, Flaviviridae, Hepeviridae, Nodaviridae, Picornaviridae, and Togaviridae for single-stranded ssRNA(+) RNA viruses, Arenaviridae, Bunyaviridae, Filoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, and Rhabdoviridae for ssRNA(−) viruses, and Birnaviridae and Reoviridae for dsRNA viruses. The data set also included sequences from recently discovered viruses isolated from arthropods that formed a monophyletic group with the Flaviviridae (also known as “flavi-like” viruses) or assigned to two new groups referred to here as the “bunya-arena-like” and “mononega-like” viruses (54, 55). The accession numbers, corresponding virus family and host category, and dinucleotide frequencies are provided in Tables S1 to S3 in the supplemental material.

Dinucleotide odds ratio measurements.

The dinucleotide composition of viral coding sequences was determined using the packages ape, ade4, and seqinr in R (56–58). Observed over expected dinucleotide ratios (odds ratios) were calculated as previously described using the formula ρXY = ƒXY/ƒXƒY, in which ƒX and ƒY represent the frequencies of the nucleotides X and Y, respectively, and ƒXY is the frequency of the corresponding dinucleotide (3). Following the lead of Karlin and Mrazek, odds ratios below 0.78 were regarded as underrepresented and ratios above 1.23 as overrepresented dinucleotides (3). To prevent a strong sampling bias in the host categories, we aggregated data from the same virus species (or genotype and serotype where applicable) isolated in the same host category and used the mean dinucleotide odds ratios for subsequent analyses. To obtain the dinucleotide odds ratios across the complete viral genome, we grouped the individual segments from those viruses with segmented genomes. This resulted in 1,024 data sets, which are summarized in Table 2, while the raw data are found in Table S4 in the supplemental material.

TABLE 2.

Number of data sets per virus family and host category used in the discriminant analysis

| Virus family | Genomea | No. of data sets after aggregationb |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmammalian vertebrates |

Mammalia |

Arthropoda |

Vector borne | |||||||||||||

| Birds | Fish | Reptiles | Bats | Carnivores | Cetartiodactyla | Equines | Insectivores | Lagomorphs | Primates | Rodents | Chelicerata | Crustacea | Insecta | |||

| Arteriviridae | + | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||||

| Astroviridae | + | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Caliciviridae | + | 9 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Coronaviridae | + | 4 | 24 | 7 | 17 | 7 | 5 | |||||||||

| Dicistroviridae | + | 3 | 12 | |||||||||||||

| Flaviviridae | + | 3 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 14 | 42 | ||||||||

| Hepeviridae | + | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Nodaviridae | + | 38 | 2 | 11 | ||||||||||||

| Picornaviridae | + | 2 | 5 | 27 | 1 | 33 | 8 | |||||||||

| Togaviridae | + | 3 | 1 | 14 | ||||||||||||

| Arenaviridae | − | 10 | 3 | 27 | ||||||||||||

| Bunyaviridae | − | 3 | 23 | 64 | 131 | |||||||||||

| Bunya-arena-like | − | 4 | 7 | |||||||||||||

| Filoviridae | − | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Orthomyxoviridae | − | 73 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |||||||||

| Paramyxoviridae | − | 12 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 18 | 6 | |||||||||

| Rhabdoviridae | − | 9 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 26 | ||||||||||

| Mononega-like | − | 6 | 14 | |||||||||||||

| Birnaviridae | ds | 2 | 7 | 5 | ||||||||||||

| Reoviridae | ds | 11 | 9 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 26 | 42 | ||

+, positive-sense RNA virus; −, negative-sense RNA virus; ds, double-stranded RNA virus.

See Table S4 in the supplemental material for a full description of the aggregated data sets.

LDA.

A linear discriminate analysis (LDA) was used to create a model that predicts either the virus family or host category from dinucleotide odds ratios alone. LDA is a pattern recognition analysis that creates “linear determinants” that are functions of the dinucleotide odds ratios and uses these determinants to predict outcome category (i.e., viral family or host category). This model was compared to a “random” model that predicted outcome category based on the proportional data set size of each viral family or host category. For example, under the random model, if a host A represents 80% of the data, each sequence has an 0.8 probability of being predicted as host A. This random model is used to show the increase in predictive power provided by the LDA model. To determine the sensitivity for individual categories (i.e., the proportion of sequences correctly classified [true-positive prediction rate]) and false-discovery rate (FDR) (i.e., the proportion of sequences incorrectly classified into a category), a bootstrapping approach was used, where half the data set was randomly selected to train the discriminant analysis and the other half used to test predictive measures. This was repeated 1,000 times and the mean sensitivity and FDRs over the 1,000 bootstraps presented. LDA was carried out in R version 3.3.1 using the lda function.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02381-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burge C, Campbell AM, Karlin S. 1992. Over- and under-representation of short oligonucleotides in DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:1358–1362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlin S, Ladunga I, Blaisdell BE. 1994. Heterogeneity of genomes: measures and values. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:12837–12841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlin S, Mrazek J. 1997. Compositional differences within and between eukaryotic genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:10227–10232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabbari K, Bernardi G. 2004. Cytosine methylation and CpG, TpG (CpA) and TpA frequencies. Gene 333:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlin S, Burge C. 1995. Dinucleotide relative abundance extremes: a genomic signature. Trends Genet 11:283–290. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)89076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travers AA, Schwabe JW. 1993. Spurring on transcription? Curr Biol 3:898–900. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90231-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutler E, Gelbart T, Han JH, Koziol JA, Beutler B. 1989. Evolution of the genome and the genetic code: selection at the dinucleotide level by methylation and polyribonucleotide cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:192–196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bird AP. 1986. CpG-rich islands and the function of DNA methylation. Nature 321:209–213. doi: 10.1038/321209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nussinov R. 1984. Strong doublet preferences in nucleotide sequences and DNA geometry. J Mol Evol 20:111–119. doi: 10.1007/BF02257371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karlin S, Doerfler W, Cardon LR. 1994. Why is CpG suppressed in the genomes of virtually all small eukaryotic viruses but not in those of large eukaryotic viruses? J Virol 68:2889–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gentles AJ, Karlin S. 2001. Genome-scale compositional comparisons in eukaryotes. Genome Res 11:540–546. doi: 10.1101/gr.163101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yakovchuk P, Protozanova E, Frank-Kamenetskii MD. 2006. Base-stacking and base-pairing contributions into thermal stability of the DNA double helix. Nucleic Acids Res 34:564–574. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shackelton LA, Parrish CR, Holmes EC. 2006. Evolutionary basis of codon usage and nucleotide composition bias in vertebrate DNA viruses. J Mol Evol 62:551–563. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rima BK, McFerran NV. 1997. Dinucleotide and stop codon frequencies in single-stranded RNA viruses. J Gen Virol 78:2859–2870. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-11-2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su MW, Lin HM, Yuan HS, Chu WC. 2009. Categorizing host-dependent RNA viruses by principal component analysis of their codon usage preferences. J Comput Biol 16:1539–1547. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2009.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahir I, Fromer M, Prat Y, Linial M. 2009. Viral adaptation to host: a proteome-based analysis of codon usage and amino acid preferences. Mol Syst Biol 5:311. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng X, Virk N, Chen W, Ji S, Ji S, Sun Y, Wu X. 2013. CpG usage in RNA viruses: data and hypotheses. PLoS One 8:e74109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai CT, Lin CH, Chang CY. 2007. Analysis of codon usage bias and base compositional constraints in iridovirus genomes. Virus Res 126:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alinejad-Rokny H, Anwar F, Waters S, Davenport MP, Ebrahimi D. 2016. Source of CpG depletion in the HIV-1 genome. Mol Biol Evol doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenbaum BD, Levine AJ, Bhanot G, Rabadan R. 2008. Patterns of evolution and host gene mimicry in influenza and other RNA viruses. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000079. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabadan R, Levine AJ, Robins H. 2006. Comparison of avian and human influenza A viruses reveals a mutational bias on the viral genomes. J Virol 80:11887–11891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01414-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenbaum BD, Rabadan R, Levine AJ. 2009. Patterns of oligonucleotide sequences in viral and host cell RNA identify mediators of the host innate immune system. PLoS One 4:e5969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaunt E, Wise HM, Zhang H, Lee LN, Atkinson NJ, Nicol MQ, Highton AJ, Klenerman P, Beard PM, Dutia BM, Digard P, Simmonds P. 2016. Elevation of CpG frequencies in influenza A genome attenuates pathogenicity but enhances host response to infection. eLife 5:e12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkinson NJ, Witteveldt J, Evans DJ, Simmonds P. 2014. The influence of CpG and UpA dinucleotide frequencies on RNA virus replication and characterization of the innate cellular pathways underlying virus attenuation and enhanced replication. Nucleic Acids Res 42:4527–4545. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright F. 1990. The ‘effective number of codons’ used in a gene. Gene 87:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins GM, Holmes EC. 2003. The extent of codon usage bias in human RNA viruses and its evolutionary origin. Virus Res 92:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00309-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaney JL, Clark PL. 2015. Roles for synonymous codon usage in protein biogenesis. Annu Rev Biophys 44:143–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-034333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Lipkin WI, Zaidi S, Delwart E. 2010. Use of nucleotide composition analysis to infer hosts for three novel picorna-like viruses. J Virol 84:10322–10328. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00601-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belalov IS, Lukashev AN. 2013. Causes and implications of codon usage bias in RNA viruses. PLoS One 8:e56642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunec D, Osterrieder N. 2016. Codon pair bias is a direct consequence of dinucleotide bias. Cell Rep 14:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mueller S, Papamichail D, Coleman JR, Skiena S, Wimmer E. 2006. Reduction of the rate of poliovirus protein synthesis through large-scale codon deoptimization causes attenuation of viral virulence by lowering specific infectivity. J Virol 80:9687–9696. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00738-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman JR, Papamichail D, Skiena S, Futcher B, Wimmer E, Mueller S. 2008. Virus attenuation by genome-scale changes in codon pair bias. Science 320:1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.1155761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mueller S, Coleman JR, Papamichail D, Ward CB, Nimnual A, Futcher B, Skiena S, Wimmer E. 2010. Live attenuated influenza virus vaccines by computer-aided rational design. Nat Biotechnol 28:723–726. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen SH, Stauft CB, Gorbatsevych O, Song Y, Ward CB, Yurovsky A, Mueller S, Futcher B, Wimmer E. 2015. Large-scale recoding of an arbovirus genome to rebalance its insect versus mammalian preference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:4749–4754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502864112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nougairede A, De Fabritus L, Aubry F, Gould EA, Holmes EC, de Lamballerie X. 2013. Random codon re-encoding induces stable reduction of replicative fitness of Chikungunya virus in primate and mosquito cells. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003172. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu W, Zhou T, Ma J, Sun X, Lu Z. 2004. Analysis of synonymous codon usage in SARS coronavirus and other viruses in the Nidovirales. Virus Res 101:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong EH, Smith DK, Rabadan R, Peiris M, Poon LL. 2010. Codon usage bias and the evolution of influenza A viruses. Codon usage biases of influenza virus. BMC Evol Biol 10:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkhout B, van Hemert F. 2015. On the biased nucleotide composition of the human coronavirus RNA genome. Virus Res 202:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M, Chen SS. 2011. The tendency to recreate ancestral CG dinucleotides in the human genome. BMC Evol Biol 11:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Upadhyay M, Samal J, Kandpal M, Vasaikar S, Biswas B, Gomes J, Vivekanandan P. 2013. CpG dinucleotide frequencies reveal the role of host methylation capabilities in parvovirus evolution. J Virol 87:13816–13824. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02515-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lobo FP, Mota BE, Pena SD, Azevedo V, Macedo AM, Tauch A, Machado CR, Franco GR. 2009. Virus-host coevolution: common patterns of nucleotide motif usage in Flaviviridae and their hosts. PLoS One 4:e6282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedersen G, Andresen L, Matthiessen MW, Rask-Madsen J, Brynskov J. 2005. Expression of Toll-like receptor 9 and response to bacterial CpG oligodeoxynucleotides in human intestinal epithelium. Clin Exp Immunol 141:298–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kingsolver MB, Huang Z, Hardy RW. 2013. Insect antiviral innate immunity: pathways, effectors, and connections. J Mol Biol 425:4921–4936. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Leung FCC. 2004. DNA structure constraint is probably a fundamental factor inducing CpG deficiency in bacteria. Bioinformatics 20:3336–3345. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karlin S, Ladunga I. 1994. Comparisons of eukaryotic genomic sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:12832–12836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pyrc K, Jebbink MF, Berkhout B, van der Hoek L. 2004. Genome structure and transcriptional regulation of human coronavirus NL63. Virol J 1:7. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woo PC, Wong BH, Huang Y, Lau SK, Yuen KY. 2007. Cytosine deamination and selection of CpG suppressed clones are the two major independent biological forces that shape codon usage bias in coronaviruses. Virology 369:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davies TJ, Pedersen AB. 2008. Phylogeny and geography predict pathogen community similarity in wild primates and humans. Proc Biol Sci 275:1695–1701. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou JH, Gao ZL, Zhang J, Ding YZ, Stipkovits L, Szathmary S, Pejsak Z, Liu YS. 2013. The analysis of codon bias of foot-and-mouth disease virus and the adaptation of this virus to the hosts. Infect Genet Evol 14:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dittmar KA, Goodenbour JM, Pan T. 2006. Tissue-specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS Genet 2:e221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Velazquez-Salinas L, Zarate S, Eschbaumer M, Lobo FP, Gladue DP, Arzt J, Novella IS, Rodriguez LL. 2016. Selective factors associated with the evolution of codon usage in natural populations of arboviruses. PLoS One 11:e0159943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moratorio G, Iriarte A, Moreno P, Musto H, Cristina J. 2013. A detailed comparative analysis on the overall codon usage patterns in West Nile virus. Infect Genet Evol 14:396–400. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li CX, Shi M, Tian JH, Lin XD, Kang YJ, Chen LJ, Qin XC, Xu J, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. 2015. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. eLife 4:e05378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shi M, Lin XD, Vasilakis N, Tian JH, Li CX, Chen LJ, Eastwood G, Diao XN, Chen MH, Chen X, Qin XC, Widen SG, Wood TG, Tesh RB, Xu J, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. 2016. Divergent viruses discovered in arthropods and vertebrates revise the evolutionary history of the Flaviviridae and related viruses. J Virol 90:659–669. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. 2004. APE: Analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20:289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dray S, Dufour AB. 2007. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J Stat Softw 22:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Charif D, Lobroy JR. 2007. SeqinR 1.0-2: a contributed package to the R project for statistical computing devoted to biological sequences retrieval and analysis, p 207–232. In Bastolla U, Porto M, Roman HE, Vendruscolo M (ed), Structural approaches to sequence evolution: molecules, networks, populations. Springer Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.