Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to examine whether the Big Five personality factors could predict who thrives or chokes under pressure during decision-making. The effects of the Big Five personality factors on decision-making ability and performance under social (Experiment 1) and combined social and time pressure (Experiment 2) were examined using the Big Five Personality Inventory and a dynamic decision-making task that required participants to learn an optimal strategy. In Experiment 1, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis showed an interaction between neuroticism and pressure condition. Neuroticism negatively predicted performance under social pressure, but did not affect decision-making under low pressure. Additionally, the negative effect of neuroticism under pressure was replicated using a combined social and time pressure manipulation in Experiment 2. These results support distraction theory whereby pressure taxes highly neurotic individuals' cognitive resources, leading to sub-optimal performance. Agreeableness also negatively predicted performance in both experiments.

Keywords: personality, decision-making, performance pressure

‘Choking under pressure’ refers to the phenomenon whereby people underperform in high stakes situations relative to their level of performance without pressure (e.g., Baumeister, 1984; Beilock & Carr, 2005; Markman, Maddox, & Worthy, 2006). In the context of decision-making, choking under pressure occurs when individuals make effective decisions in low-pressure situations but sub-optimal decisions under pressure. Thus, their decision-making performance decreases as the level of pressure increases. Trait activation theory, which proposes that specific trait-relevant situational cues can be used to predict behavioral responses to those situations, may help explain how specific traits may elicit different behaviors in low- and high-pressure contexts (Tett & Guterman, 2000). Responses depend on both the relevance of a situation to a trait and the strength of the trait evoked. Thus, certain traits are more likely to emerge if a situation strongly evokes them (Lievens et al., 2006).

Performance pressure often occurs in high-stakes success or failure situations, and consequently, these situations may activate certain traits, such as anxiety, narcissism, and fear of negative evaluation, that may in turn affect individual performance. For example, anxiety for test-taking or competitions has been shown to lead to decrements in performance in those situations, even though anxious individuals may be highly competent in low-pressure contexts (e.g., Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001; Beilock & Carr, 2005; Martens, Vealey, & Burton, 1995). Fear of negative evaluation has also been shown to increase anxiety and decrease performance under pressure in athletes (Mesagno, Harvey, & Janelle, 2012). Moreover, low levels of narcissism have been associated with poor performance under pressure on both physical and cognitive tasks (Wallace & Baumeister, 2002). While previous research has examined how personality influences performance under pressure, it is less clear how personality would affect performance in the decision-making domain specifically. In the present study, we examine the important question of ‘who chokes under pressure’ by focusing on how individual differences in personality might affect decision-making under pressure.

The Big Five personality model, comprising the factors of openness, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism, is the most widely used classification of personality in psychological research (John & Srivastava, 1999). In decision-making domains, the Big Five model has been studied in the context of delay discounting, reward sensitivity, gambling, and risk-taking (e.g., Hirsh, Moriscano, Peterson, 2008; Mecca, 2003; Nicholson, Soane, Fenton-O'Creevy, & Willman, 2005; Ostaszewski, 1996), though little is known regarding how the Big Five personality model plays a role in decision-making under pressure. However, one theoretical approach to examine choking under pressure during decision-making is offered by distraction theory, which proposes that pressure-filled situations distract attention away from the task, leading to poorer performance (Lewis & Linder, 1997). In contrast to explicit monitoring theory which applies in the context of proceduralized skills (Baumeister, 1984), distraction theory is relevant to cognitive processes, such as decision-making (Lewis & Linder, 1997). According to research on distraction theory, pressure generates mental distractions that decrease available working memory (WM) resources that should be allotted to cognitively demanding tasks (Beilock & Carr, 2005; Beilock et al., 2004). In the context of decision-making, individuals who are preoccupied by the pressure component of a decision may be more likely to have reduced cognitive resources available to make an optimal decision.

In regard to the Big Five traits, previous research has established that neuroticism is positively associated with anxiety and that this relationship is mediated by thoughts of rumination and worry (Muris et al., 2005). Furthermore, anxiety has been shown to create intrusive thoughts that disrupt math problem solving ability by taxing WM resources (Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001). Additional support for the detrimental effect of distraction theory on performance has shown that high-pressure situations also create mental distractions that compete for and diminish WM resources that are allocated to the task in low-pressure situations (Beilock & Carr, 2004). Therefore, under pressure more neurotic individuals should have higher levels anxiety and pressure-related intrusive thoughts that may occupy WM resources, leading to performance decrements as a result of decreased WM capacity in high-pressure situations compared to low-pressure situations. This theory offers a potential mechanism by which neurotic individuals may fail when they most need to succeed.

Besides neuroticism, little work has related personality with both pressure and decision-making contexts. As a result, there are few inferences we can draw about the relationship between choking under pressure during decision-making and openness, extraversion, or agreeableness. With regard to conscientiousness, previous work with the N-back task showed that highly conscientious individuals are more focused on performance tasks, but are less effective at applying skills they learn to other tasks (Studer-Luethi Jaeggi, Buschkuehl, & Perrig, 2012). As distraction theory suggests, pressure may increase cognitive load and consume that focus and attention, leading to decrements in performance, or ‘choking’, compared to pressure-free situations. However, based on previous research with performance pressure and distraction theory, neuroticism was predicted to be the most likely trait to affect decision-making behavior under pressure.

In order to assess decision-making performance, we utilize a reflective decision-making task in which the optimal strategy involves foregoing an option with larger immediate rewards on each trial in favor of an option that provides larger delayed rewards. Prior work using this task has shown that performing a concurrent dual WM-demanding task impairs decision-making performance whereby individuals selected the immediately rewarding option more, indicating that the task is WM dependent and that WM distraction could cause performance decrements (Worthy, Otto, & Maddox, 2012). By utilizing this task we can examine whether certain personality characteristics may make individuals more vulnerable to distraction of WM resources when placed under pressure, which would result in preference for the immediately rewarding option, and consequently impaired performance, on the task.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 used a dynamic decision-making task that has been previously used to study individuals’ ability to find a decision strategy when the task involved choosing between immediate and long-term benefits of each option (Gureckis & Love, 2009; Worthy, Gorlick, Pacheco, Schnyer, & Maddox, 2011; Worthy et al., 2012). This task is choice history-dependent in that the rewards they receive are dependent on their decisions made on previous trials. We used a social pressure manipulation that has been used extensively in previous work with both between- and within-subjects designs, and has been shown to impair performance in cognitively demanding tasks (Beilock & Carr, 2005; Beilock et al., 2004; DeCaro, Thomas, Albert, & Beilock, 2011; Markman et al., 2006; Worthy, Markman, & Maddox, 2009). It has also been shown to enhance WM distraction (DeCaro et al., 2011), and we predicted that WM distraction would hurt performance on the task given prior work that has found a negative effect of WM load in the same task (Worthy et al., 2012). Participants were instructed that if they reached a certain performance criterion on the task, then both they and a (fictitious) partner would earn a monetary bonus, but if they failed to reach their goal neither would receive the bonus. This manipulation was designed to mirror the effect of common sources of real-word pressure, including monetary incentives, peer pressure, and social evaluation in decision-making contexts.

Method

Participants

One hundred and twenty-seven (76 female, 51 male) undergraduate students at Texas A&M University participated in the experiment for course credit. Participants were randomly assigned to either the low-pressure (n=63) or high-pressure (n=64) condition.

Measures

Big Five Inventory

The 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI) consisted of statements regarding openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Participants were asked to indicate, using a 5-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree), the degree to which each statement described their personality (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991). The BFI has been shown to have high internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha ranging from .79 - .88 for each of the five personality traits (M=.83), and has strong convergent validity with other Big Five personality scales, including the Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; r=.73) and the Trait Descriptive Adjectives questionnaire (TDA; r=.81; John & Srivastava, 1999).

Decision-Making Task

The dynamic decision-making task entailed selecting between immediate and long-term benefits (Gureckis & Love, 2009; Worthy, Gorlick, Pacheco, Schnyer, & Maddox, 2011; Worthy et al., 2012). In the task, participants repeatedly chose between two options that provide points on each trial in attempt to maximize the number of points gained over the course of the experiment. The Increasing option gave a smaller immediate reward on each trial, but caused delayed rewards for both options to increase. In contrast, the Decreasing option gave a larger immediate reward, but caused delayed rewards for both options to decrease. Point values increased or decreased by five-point increments for each option. Participants started the task with 55 points if choosing the Increasing option first which increased to a maximum value of 80 points if repeatedly selected. Similarly, participants started the task with 65 points for the Decreasing option, which decreased a minimum value of 40 points (Table 1).

Table 1.

Points Earned on the Decision-Making Task by Selecting the Increasing or Decreasing Options

| Increasing Option Selections | Decreasing Option Selections | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing Option | Decreasing Option | Increasing Option | Decreasing Option |

| 55 | 65 | 55 | 65 |

| 55 | 65 | 55 | 65 |

| 60 | 70 | 50 | 60 |

| 60 | 70 | 50 | 60 |

| 65 | 75 | 45 | 55 |

| 65 | 75 | 45 | 55 |

| 70 | 80 | 40 | 50 |

| 70 | 80 | 40 | 50 |

| 75 | 85 | 35 | 45 |

| 75 | 85 | 35 | 45 |

| 80 | 90 | 30 | 40 |

| 80 | 90 | 30 | 40 |

| 80 | 90 | 30 | 40 |

Note. Pattern of points earned in the Increasing-Optimal task for the Increasing and Decreasing options if the Increasing option is repeatedly selected (left) or if the Decreasing option is repeatedly selected (right). Participants begin with 55 points for the Increasing option and 65 points for the Decreasing option. If the Increasing option is repeatedly selected, individuals will earn 80 points on each trial after the first ten trials. If the Decreasing option is repeatedly selected, individuals will earn 40 points on each trial after the initial ten trials. Thus repeatedly selecting the Increasing option leads to a 40 point advantage compared to the Decreasing option. Switching between decks follows the same pattern.

The optimal strategy was to select the Increasing option because it led to larger cumulative reward, despite always giving a smaller immediate reward on each trial. Participants were also shown the foregone reward for the unchosen option, or the points they would have received if they had selected the other option, on each trial (Byrne & Worthy, 2013; Otto & Love, 2010). This made the higher immediate rewards provided by the Decreasing option more salient and increased task difficulty. For example, if they earned 40 points by selecting the Decreasing option, they were informed that they would have received only 30 points had they selected the Increasing option.

Procedure

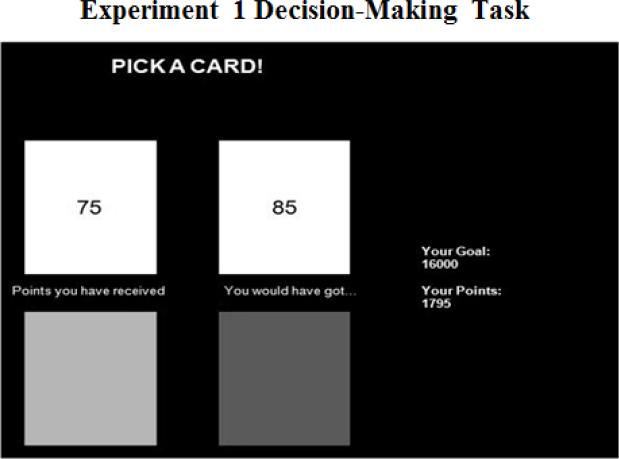

All participants completed the experiment on PC computers using Psychtoolbox for Matlab (version 2.5). Participants first completed the BFI and were then given instructions for the two-option dynamic decision-making task described above. Participants in both pressure conditions were instructed that they would need to repeatedly select from one of two decks, and both decks would provide between 0 and 100 points on each draw. Participants were told that they should try to do their best to earn as many points as possible and were given a goal of earning at least 16,000 points by the end of the task, which corresponded to selecting the optimal Increasing option on 80% of trials. All participants viewed the points earned for each selection, and the points they would have received for selecting the other option (Figure 1). Participants completed 250 trials of the decision-making task. They were not informed about the number of trials or the length of the task, however. The proportion of trials in which the Increasing option was selected was recorded for each participant.

Figure 1.

Sample screenshot from the decision-making task in Experiment 1.

In addition to the decision-making task instructions, participants in the high pressure condition were also told that they were paired with another participant in the experiment, and if both they and their (fictitious) partner met the goal of earning 16,000 points, then both of them would receive an $8 bonus. However, if either of them failed to reach the goal, then neither they nor their partner would earn the bonus. Then, they were informed that their partner had already achieved the goal, so whether or not they both earned the bonus depended solely on the participant's performance. No partner actually existed, but this hypothetical scenario was meant to place half of participants in the pressure condition. Participants also completed a post-task question indicating the importance of performing at a high level on the task using a 1 (not at all) – 7 (extremely) scale. Individuals who did indeed reach the goal by the end of the task were compensated with an $8 check.

Results

Tests for Personality Differences

In order to establish that the low and high-pressure groups were similar in regard to each of the five personality factors, we conducted independent samples t-tests for each factor with pressure condition as the predictor. Since there were five tests, one for each variable, and we did not have a priori predictions for differences between the two groups, we performed a Bonferroni correction to control for Type 1 error. Results indicated that none of the personality factors were significantly different between pressure conditions, p>.01.

For the post-task question, individuals in the low-pressure condition reported feeling that their performance was less importance (M=4.68, SD=2.42) than those in the high-pressure condition (M=5.17, SD=2.14), though this difference was not statistically significant1.

Correlational Analyses

Correlational analyses were performed between the Big Five Personality factors and performance within each condition on the decision-making task as measured by the average proportion of Increasing option selections across all 250 trials (Table 2). In the low-pressure condition, none of the Big Five personality factors were significantly correlated with performance. In the pressure condition, however, conscientiousness, r= −.27, p<.05, and neuroticism, r=−.34, p<.01, were both negatively correlated with performance in the decision-making task.

Table 2.

Correlations between each of the Big Five personality-factors and average proportion of Increasing option selections in Experiment 1

| Mean | s.n | O | C | E | A | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Pressure Condition | |||||||

| 0 | 34.52 | 5.82 | |||||

| C | 32.59 | 5.58 | −.12 | ||||

| E | 27.94 | 5.08 | .08 | .22 | |||

| A | 36.38 | 4.64 | −.04 | .40** | .11 | ||

| N | 23.98 | 5.84 | .28* | −.38** | −.31** | −.30** | |

| Average Increasing | .45 | .31 | .11 | .04 | .12 | .04 | −0.10 |

| High-Pressure Condition | |||||||

| O | 35.92 | 5.89 | |||||

| C | 32.86 | 5.40 | .14 | ||||

| E | 27.52 | 6.69 | −.01 | .12 | |||

| A | 36.80 | 5.50 | .07 | .36** | .19 | ||

| N | 21.13 | 6.81 | −.05 | −.23 | −.27* | −.37** | |

| Average Increasing | .34 | .32 | −.03 | −.27* | −.01 | −.12 | −0.34** |

Note. Means and standard deviations for, and correlation between each of the Big Five personality factors and the average Increasing option selected during the decision-making task in each condition in Experiment 1 (O represents Openness, C represents Conscientiousness, E represents Extraversion, A represents Agreeableness, N represents Neuroticism).

indicates significance at the p = .01 level.

indicates significant at the p = .05 level.

Regression Analyses

Next, a two-step hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed. In the first step we tested whether pressure condition (dummy-coded as 0 for low pressure and 1 for high pressure) and Big Five personality traits predicted decision-making performance. The first-step model predicting performance from pressure and single-order personality terms approached significance, R2=.10, F(6, 120)=2.14, p=.054. Condition negatively predicted performance, β=−.43, p=.02, indicating poorer performance under pressure than under no pressure. Of the personality factors, neuroticism, β=−.25, p=.01, negatively predicted performance on the task, and conscientiousness, β=−.16, p=.09, also showed a negative trend towards significance. None of the other personality factors were significant.

The addition of the interaction terms accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in decision-making performance, ΔR2=.06, F(11, 115)=1.96, p=.04. In addition, we found a significant pressure condition X Neuroticism interaction, β=−.45, p=.02 (Table 3). To identify the locus of the interaction, separate multiple regressions were performed within the low and high pressure conditions While neuroticism did not have a significant relationship with performance in the low pressure condition, higher levels of neuroticism were associated with decreased performance in the high pressure task, β=−.50, p<.01. The pressure condition X agreeableness interaction also trended towards significance, β=−.33, p=.08. Like with neuroticism, while agreeableness did not predict decision-making performance in the low pressure condition, higher levels of agreeableness were associated with a decline in performance under high pressure, although this effect was not significant, β=− .18, p=.17. No other pressure condition by personality interaction terms were significant.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients for Experiment1

| β | S.E. | |

|---|---|---|

| Condition | −.43* | .18 |

| O | .07 | .09 |

| C | −.16 | .10 |

| E | .01 | .09 |

| A | −.07 | .10 |

| N | −.25 | .09 |

| Condition by O | −.12 | .18 |

| Condition by C | .08 | .13 |

| Condition by E | −.23 | .19 |

| Condition by A | −.33 | .19 |

| Condition by N | −.45* | .19 |

Note. Standardized beta coefficients and standard errors for the multiple regression of condition, the Big Five factors, and condition by Big Five factor interaction terms predicting performance on the decision-making task as measured by the average Increasing option selected in Experiment 1 [O represents Openness, C represents Conscientiousness, E represents Extraversion, A represents Agreeableness, N represents Neuroticism).

** indicates significance at the p = .01 level.

indicates significant at the p = .05 level.

Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 indicated that higher levels of neuroticism predicted reduced selection of the optimal Increasing option compared to individuals with lower levels of trait neuroticism. A negative correlation between conscientiousness and performance in the high pressure condition was also observed, although this factor did not reach significance in the regression model. Moreover, the pressure condition by agreeableness interaction trended towards significance in the regression analysis whereby more agreeable individuals tended to select the optimal Increasing options less often than individuals scoring lower on agreeableness; however, this interaction failed to reach significance, and consequently the interpretation of this finding is limited. Based on these results, it appears that under social pressure individuals with higher levels of neuroticism perform more poorly than individuals lower in trait neuroticism, indicating that they are more susceptible to pressure, and specifically, to making sub-optimal decisions while under pressure. As previous research with agreeableness and decision-making has been limited, we did not have specific predictions for agreeableness and performance pressure in this experiment. Thus, we cannot make strong conclusions regarding the effect of agreeableness on decision-making under pressure.

In order to replicate the effect of neuroticism and further examine the role of conscientiousness and agreeableness on performance under pressure during decision-making, a second experiment was conducted. In Experiment 2 we sought to determine whether the results of Experiment 1 can be extended to other forms of pressure, rather than social pressure specifically.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, the task conditions were the same as in Experiment 1 but with an added time pressure constraint. We added this constraint to mirror many real-world situations where a task must be completed within a given period of time or by a deadline. Adding time pressure to the task allows us to determine if the results from Experiment 1 replicate and test whether personality factors can influence performance under pressure under both social and time pressure during decision-making. We did not include a low-pressure condition in Experiment 2 and focused exclusively on how personality affected performance under pressure.

Method

Participants

Sixty-five (37 female, 28 male) undergraduate students at Texas A&M University participated in the experiment for course credit.

Measures and Procedure

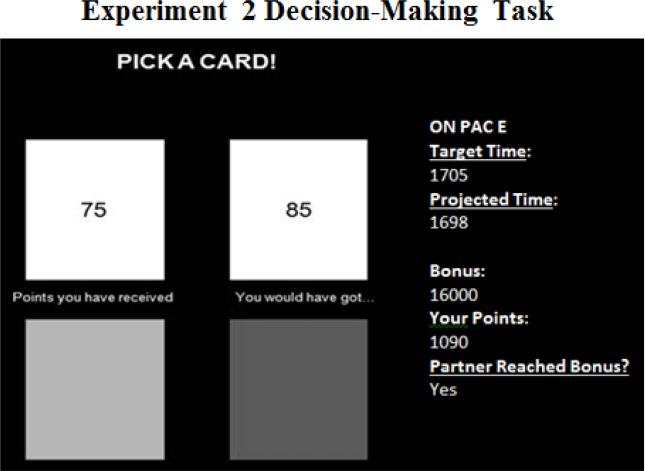

As in Experiment 1, participants completed the BFI followed by the dynamic decision-making task. The decision-making task was identical to Experiment 1; however, the pressure manipulation was modified. Participants were given the same social pressure manipulation as in Experiment 1. In addition, participants were informed that they would only have a limited time to complete the experiment. They were told that based on the performance of previous participants they would be required to complete the experiment in 1705 seconds, or just over 28 minutes.2 Participants were also informed that if they failed to complete the experiment within the time limit, neither they nor their partner would receive the bonus. Thus, in order to reach the bonus, participants were instructed that they had to not only earn the goal amount of points, but also complete the experiment within the time limit. While completing the experiment, participants were informed of their progress in regard to points and time after each deck selection. The amount of points they earned and the goal (16,000 points) were available on the screen as well as the target time (1705 seconds) and their projected time. If the projected time was less than the target time, the participants were shown the words “On Pace” in green letters to show that they were on pace to earn the bonus. If the projected time was greater than the target time, however, they were shown “Behind Pace” in red letters to indicate that they were behind pace to earn the bonus (Figure 2). Therefore, participants were able to track their progress and success in terms of both the social and time pressure manipulations throughout the duration of the decision-making task.

Figure 2.

Sample screen shot of the decision-making task in Experiment 2. Participants were shown the points they earned, the goal needed to reach the bonus, the foregone reward information, and their projected time of task completion. If projected time was less than the target time, participants were shown that they were “on pace”, and if the projected time was greater than the target time, they were shown that they were “behind pace”.

Results

Correlational Analyses

Correlational analyses were performed between the Big Five Personality factors, total completion time, and performance on the decision-making task across all 250 trials (Table 4). Three individuals were above two standard deviations (292 seconds) of the mean (1699 seconds) for total completion time and were excluded from analysis to eliminate individuals who were not focusing on or attentive to the task. Agreeableness was negatively correlated with decision-making performance, r=−.29, p<.05. There were also negative relationships between performance and neuroticism, r=−.16, and conscientiousness, r=−.16, although neither reached significance.

Table 4.

Correlation between the Big Fire personality factors and average Increasing option selections in Experiment2

| Mean | S.D. | O | C | E | A | N | Completion Time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | 34.87 | 6.47 | ||||||

| C | 32.75 | 5.82 | −.09 | |||||

| E | 27.62 | 7.46 | .22 | .03 | ||||

| A | 35.7 | 4.91 | −.06 | .26* | .14 | |||

| N | 21.84 | 6.52 | −.13 | −.21 | −.23 | −.31* | ||

| Completion Time | 1670 | 55.73 | −.08 | .07 | .06 | .27* | .11 | |

| Average Increasing | .39 | .34 | −.07 | −.16 | .04 | −.29* | −.16 | −.62** |

Note. Means and standard deviations for, and correlation between, each of the Big Five personality factors, total completion time and the average Increasing option selected during the decision-making task in Experiment 2 [O represents Openness, C represents Conscientiousness, E represents Extraversion, A represents Agreeableness, N represents Neuroticism).

indicates significance at the p = .01 level.

indicates significant at the p = .05 level.

Regression Analyses

A multiple regression analysis was performed to test if the Big Five personality traits predicted decision-making performance (Table 5). The overall model was significant, R2=.19, F(5, 55)=2.61, p<.05. Neuroticism, β=−.31, p<.05, and agreeableness, β=−.36, p<.01, both negatively predicting decision-making performance under social and time pressure.

Table 5.

Regression Coefficients for Experiment2

Note. Standardized beta coefficients and standard errors for the multiple regression of the Big Five factors and the decision-making task as measured by the average Increasing option selected in Experiment 2 [O represents Openness, C represents Conscientiousness, E represents Extraversi on, A represents Agreeableness, N represents Neuroticism).

indicates significance at the p = .01 level.

indicates significant at the p = .05 level.

For the post-task question, participants reported feeling that the importance of their performance similar to that of the high-pressure condition in Experiment 1 (M=5.05, SD=2.13).

Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 replicate the findings of Experiment 1 for neuroticism, indicating that individuals higher in neuroticism are more likely to choke under combined social and time pressure during decision-making in addition to social pressure alone, as Experiment 1 indicated. Although results from Experiment 1 raised the possibility that conscientiousness may predict performance under social pressure, Experiment 2 findings showed that conscientiousness did not predict performance when time pressure was added into the decision-making task. Consequently, we cannot make clear conclusions about conscientiousness, and more research is needed to probe the link between conscientiousness and choking under pressure. Agreeableness also predicted performance under time pressure and was correlated with, though was not significantly predictive of, performance in Experiment 1. While prior research has shown that more agreeable individuals are less risk-taking (Nicholson et al., 2005), the results of the present study are the first to suggest that trait agreeableness may be associated with choking under pressure in decision-making contexts. Additionally, one limitation of Experiment 2 is that the control condition compared to was from Experiment 1, and the findings should thus be interpreted with regard to this caveat.

General Discussion

Across two experiments we found a strong inverse relationship between self-reported levels of neuroticism and performance under pressure in decision-making scenarios. Additionally, while a preliminary finding in Experiment 1 emerged showing a possible negative association between conscientiousness and decision-making performance under pressure, this finding was not supported by further analyses or replicated in Experiment 2. We also observed a marginally significant effect of agreeableness predicting decision-making deficits under pressure in Experiment 1, which was supported by Experiment 2 results. The findings of the present investigation are in line with both our hypothesis and prior research with neuroticism and distraction theory; neurotics tended to select the less WM-taxing, immediately rewarding option under pressure, instead of keeping track of the rewards offered by options on previous trials to figure out the best strategy. The results were not only observed under social pressure alone, but were also replicated when social pressure was combined with a time pressure manipulation. Consistent with distraction theory, it appears that the increased anxiety associated with neuroticism may increase pressure-related intrusive thoughts that decrease WM resources. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that under pressure highly neurotic individuals are more likely to ‘choke’ because the pressure load taxes their cognitive resources and allows for more impulsive behavior. Consequently, neurotic individuals may benefit from trying to reduce their stress/anxiety levels under pressure in order to make more effective decisions. It is important, however, that stress reduction techniques lead to an automatic reduction of stress levels, so as not to interfere with working memory capacity.

The finding that high agreeableness is associated with decrements in decision-making performance under social pressure alone and combined social and time pressure is unanticipated but provides novel insight into the relationship of agreeableness and decision-making. In accordance with trait activation theory, it is possible that performance pressure in decision-making contexts may provide a situation that elicits anxiety in highly agreeable individuals. While distraction theory has not been associated with trait agreeableness, our results suggest the possibility that pressure-induced anxiety may tax WM resources in more agreeable individuals. However, given our lack of a priori predictions about the association between agreeableness and decision-making under pressure, the effect we observed should be considered exploratory and examined in future work. As expected from prior research, neither extraversion nor openness impacted decision-making performance under pressure. Future studies aimed at individual differences in decision-making should consider the difference between individual and group decision-making, especially if extraversion is being examined since it is an interpersonal trait and this experiment focused on individual decisions.

Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation to the study design is that the social pressure manipulation comprised a monetary incentive component that was absent from the low-pressure condition. The results of our study, therefore, do not provide definitive conclusions distinguishing the effects of monetary incentives from social pressure, and future work should be aimed at disentangling the role of personality in response to financial and social pressure independently. However, because this manipulation has been used in several previous studies, including those with both between- and within-subjects designs (Beilock & Carr, 2005; Beilock et al., 2004; DeCaro et al., 2011; Markman et al., 2006; Worthy, Markman, & Maddox, 2009), it appears to remain a valid induction of high-pressure situations.

Additionally, in Experiment 1 we observed different group means for neuroticism between the low- and high-pressure conditions. While this could have skewed the results, it is important to note that the mean level of neuroticism for the low-pressure condition was higher than the high-pressure condition. Future work examining the relationship between personality and performance pressure should also consider including pressure manipulation checks to examine perception of pressure and affective states such as anxiety or mood, testing for differences in working memory capacity between personality groups, and using a within-subjects design to account for group differences. Finally, it is important to note that these results may not apply to all high-pressure situations, but may be limited to the decision-making domain.

It is clear there are individual differences that contribute to choking under pressure during decision-making. The business people, public officials, and test-takers that are all-too-familiar with the phenomenon of choking during decision-making may have neurotic or agreeable tendencies that contribute to their sub-optimal performance in high pressure decision-making situations. Although different in talent and ability, ‘chokers’ may share some similar personality traits that help answer the question of who chokes under pressure during decision-making.

Footnotes

While there were not significant differences in self-reported pressure between conditions, the mean of the low-pressure condition was higher than that reported in previous studies (Beilock et al., 2004).Participants may have perceived more pressure to perform well in the decision-making task we used than in the working memory and category-learning tasks used in prior studies because they were given a specific goal (Beilock et al., 2004; Beilock & Carr, 2005; DeCaro, Thomas, Albert, & Beilock, 2011; Markman et al., 2006; Worthy, Markman, & Maddox, 2009).

This amount of time was derived by requiring participants to respond, on average, within 500ms on each trial. In Experiment 1, across both conditions, participants average responses times were approximately 680ms per trial, and there was no difference between low and high pressure conditions. Thus, participants in Experiment 2 had to make decisions about 25% faster than participants in Experiment 1.

References

- Ashcraft MH, Kirk EP. The relationships among working memory, math anxiety, and performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.130.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. Choking under pressure: self-consciousness and paradoxical effects of incentives on skillful performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:610–620. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilock SL, Carr TH. When high-powered people fail: Working memory and “choking under pressure” in math. Psychological Science. 2005;16:101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilock SL, Kulp CA, Holt LE, Carr TH. More on the fragility of performance: Choking under pressure in mathematical problem solving. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General. 2004;133:584–599. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne K, Worthy DA. Do narcissists make better decisions? An investigation of narcissism and dynamic decision-making performance. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;55:112–117. [Google Scholar]

- DeCaro MS, Thomas RD, Albert NB, Beilock SL. Choking under pressure: Multiple routes to skill failure. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General. 2011;140:390–406. doi: 10.1037/a0023466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureckis TM, Love BC. Learning in noise: Dynamic decision-making in a variable environment. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 2009;53:180–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh JB, Morisano D, Peterson JB. Delay discounting: Interactions between personality and cognitive ability. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:1646–1650. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. The Big Five Inventory: Versions 4a and 54, Institute of personality and social research. University of California; Berkeley, CA.: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lievens F, Chasteen CS, Day EA, Christiansen ND. Large-scale investigation of the role of trait activation theory for understanding assessment center convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:247–258. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Linder DE. Thinking about choking? Attentional processes and paradoxical performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:937–944. doi: 10.1177/0146167297239003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman AB, Maddox WT, Worthy DA. Choking and excelling under pressure. Psychological Science. 2006;17:944–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens R, Vealey RS, Burton D. Competitive anxiety in sport. Human kinetics. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Mecca DN. The relationship between pathological gambling and the Big-Five personality factors. Central Connecticut State University; New Britain, CT: 2003. Unpublished master's thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Mesagno C, Harvey JT, Janelle CM. Choking under pressure: The role of fear of negative evaluation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2012;13:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Roelofs J, Rassin E, Franken I, Mayer B. Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety and depression. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:1105–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson N, Soane E, Fenton-O'Creevy M, Willman P. Personality and domain-specific risk taking. Journal of Risk Research. 2005;8:157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ostaszewski P. The relation between temperament and rate of temporal discounting. European Journal of Personality. 1996;10:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Otto AR, Love BC. You don't know what you're missing: When information about foregone rewards impedes dynamic decision making. Judgment and Decision-Making. 2010;5:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Studer-Luethi B, Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Perrig WJ. Influence of neuroticism and conscientiousness on working memory training outcome. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;53:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Tett RP, Guterman HA. Situation trait relevance, trait expression, and cross- situational consistency: Testing a principle of trait activation. Journal of Research in Personality. 2000;34:397–423. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace HM, Baumeister RF. The performance of narcissists rises and falls with perceived opportunity for glory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:819–834. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.5.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthy DA, Gorlick MA, Pacheco JL, Schnyer DM, Maddox WT. With age comes wisdom: Decision-making in younger and older adults. Psychological Science. 2011;22:1375–1380. doi: 10.1177/0956797611420301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthy DA, Markman AB, Maddox WT. Choking and excelling under pressure in experienced classifiers. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2009;71:924–935. doi: 10.3758/APP.71.4.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthy DA, Otto AR, Maddox WT. Working-memory load and temporal myopia in dynamic decision-making. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2012;386:1640–1658. doi: 10.1037/a0028146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]