Abstract

Background

Positive psychological constructs, such as optimism, are associated with greater participation in cardiac health behaviors and improved cardiac outcomes. Positive psychology interventions, which target psychological well-being, may represent a promising approach to improving health behaviors in high-risk cardiac patients. However, no study has assessed whether a positive psychology intervention can promote physical activity following an acute coronary syndrome.

Objective

In this article we will describe the methods of a novel factorial design study to aid the development of a positive psychology-based intervention for acute coronary syndrome patients, and aim to provide preliminary feasibility data on study implementation.

Methods

The Positive Emotions after Acute Cardiac Events III (PEACE III) study is an optimization study (planned N=128), subsumed within a larger Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) iterative treatment development project. The goal of PEACE III is to identify the ideal components of a positive psychology-based intervention to improve post-acute coronary syndrome physical activity. Using a 2×2×2 factorial design, PEACE III aims to: (1) evaluate the relative merits of using positive psychology exercises alone or combined with motivational interviewing, (2) assess whether weekly or daily positive psychology exercise completion is optimal, and (3) determine the utility of booster sessions. The study’s primary outcome measure is moderate-to-vigorous physical activity at 16 weeks, measured via accelerometer. Secondary outcome measures include psychological, functional, and adherence-related behavioral outcomes, along with metrics of feasibility and acceptability.

For the primary study outcome, we will use a mixed-effects model with a random intercept (to account for repeated measures) to assess the main effects of each component (inclusion of motivational interviewing in the exercises, duration of the intervention, inclusion of booster sessions) from a full factorial model controlling for baseline activity. Similar analyses will be performed on self-report measures and objectively-measured medication adherence over 16 weeks. We hypothesize that the combined positive psychology and motivational interviewing intervention, weekly exercises, and booster sessions will be associated with superior physical activity.

Results

Thus far, 78 participants have enrolled, with 72% of all possible exercises fully completed by participants.

Conclusion

The PEACE III study will help to determine the optimal content, intensity, and duration of a positive psychology intervention in post-acute coronary syndrome patients prior to testing in a randomized trial. The study is novel in its use of a factorial design within the MOST framework to optimize a behavioral intervention and the use of a positive psychology intervention to promote physical activity in high-risk cardiac patients.

Keywords: Positive psychology, multiphase optimization strategy, factorial design study

Introduction

Every year, over 1.3 million Americans experience an acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction or unstable angina).1 Of these, approximately 20% will be rehospitalized for heart disease or suffer mortality within the next year.2 Adherence to recommended post-acute coronary syndrome health behaviors—such as increasing physical activity, following a low-fat diet, and adhering to medication—is associated with substantially lower risk of recurrent events and mortality.3,4 However, the majority of patients are non-adherent to one or more of these recommendations.1,3,5

Positive psychological constructs, such as optimism, are associated with greater adherence to evidence-based recommendations for physical activity,6 diet,7,8 and medication,9 and lower rates of heart disease.10,11 Programs to cultivate positive cognitive and emotional experiences, termed positive psychology interventions, utilize short tasks focusing on constructs such as gratitude and optimism.12 These interventions have reduced distress and improved well-being across 6000 study participants,13 including patients with diabetes, hypertension, and HIV.14–16

There is an ongoing need for innovative, feasible, and effective methods of improving post-acute coronary syndrome health behaviors, and positive psychology interventions may provide a novel approach to increasing adherence and improving cardiac outcomes in this population. However, few studies have assessed whether such interventions can promote health behaviors,13,17 and prior to our pilot work,18 no study had evaluated these interventions in post-acute coronary syndrome patients. Importantly, positive psychology programs differ from somewhat-related interventions, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction and self-efficacy programs.19–21 Unlike those interventions, positive psychology: (a) directly targets constructs—positive affect, optimism, and mood—linked to physical activity and superior clinical outcomes in cardiac patients, (b) utilizes validated positive psychology exercises found effective in dozens of studies,22 and (c) is simple for patients and does not require extensive provider training23 or numerous in-person sessions for patients.19,23 These factors should make positive psychology distinctive, effective, and feasible.

To specifically adapt positive psychology programs for acute coronary syndrome patients, we are employing the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST),24 a systematic method for preparing, optimizing, and evaluating multi-component behavioral interventions. The goal of this strategy is to ensure that new behavioral treatment interventions are efficiently created and optimized prior to large efficacy trials. For example, one application might first involve a comparison of intervention components (e.g., pharmacotherapy) in complete or fractional factorial trials, followed by proof-of-concept trials of potential multicomponent interventions, prior to large efficacy trials. This method improves upon prior approaches that tested new interventions in large randomized trials with minimal optimization beforehand, and it has been used successfully to optimize behavioral interventions in non-cardiac populations.25

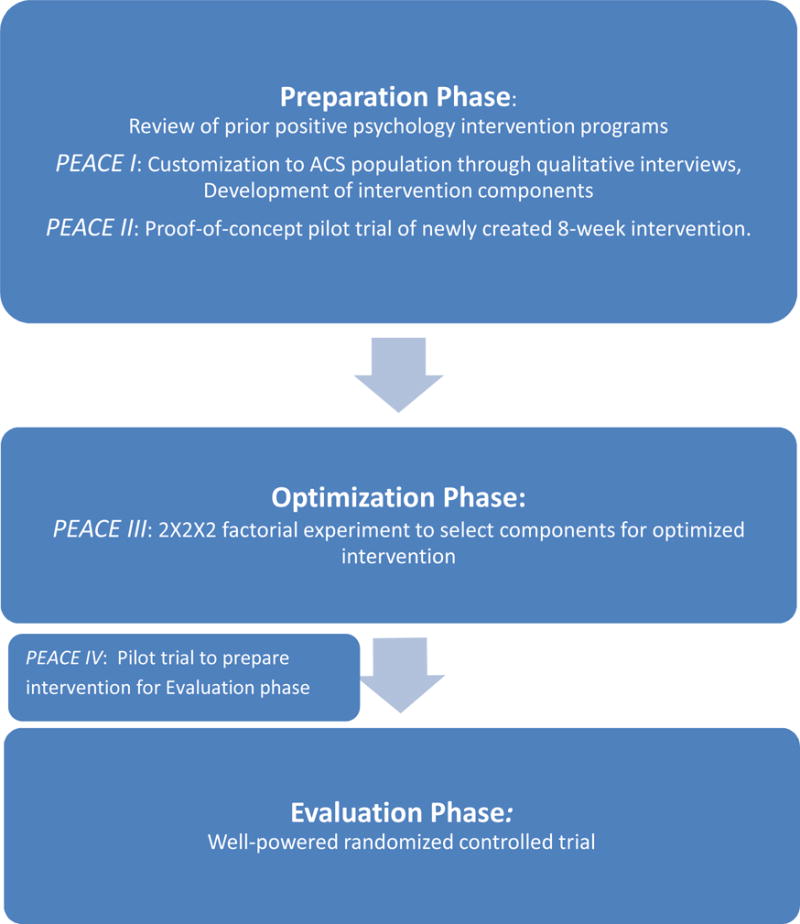

In the Positive Emotions in Acute Coronary Events (PEACE) project, we have used MOST to develop a strategy (Figure 1) to optimize a positive psychology-based intervention to promote physical activity in post-acute coronary syndrome patients. In the preparation phase, qualitative interviews (PEACE I) were performed to identify important intervention elements and customize the intervention to these patients,26 and we a conducted a proof-of-concept trial (PEACE II)27 to assess feasibility/acceptability and gather feedback about a core positive psychology-based intervention in post-acute coronary syndrome patients. PEACE III initiates the optimization phase as a next step ‘dose-finding’ trial in which the core intervention’s content, intensity, and duration is modified and tested to determine optimal approaches in these domains with respect to the promotion of physical activity.

Figure 1.

Steps of the Multiphase Optimization Strategic Testing (MOST) process17

Utilizing a randomized, complete factorial design with 8 study conditions, the PEACE III study will: 1) compare the relative merits of utilizing positive psychology exercises alone versus combining them with motivational interviewing, a well-established technique for facilitating behavioral change,28 2) assess whether daily or weekly exercise completion is superior, and 3) determine the utility of additional “booster” sessions after the initial 8-week intervention. The results of these three simultaneous embedded comparisons of physical activity will inform the selection of the optimal components for this intervention. Once the optimized intervention is identified, we will complete a pilot study (PEACE IV) in preparation for a future well-powered randomized controlled trial in an evaluation stage. In this report, we will describe the rationale, methodology, aims, analytic plan and preliminary feasibility results for the PEACE III trial.

Methods

Overview and preliminary work

PEACE III is a factorial design study aimed at assessing the components of a phone-delivered positive psychology based intervention to promote physical activity in post-acute coronary syndrome patients reporting low baseline activity. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to beginning study procedures.

To develop the core intervention, we reviewed prior positive psychology intervention programs in medical and non-medical populations.12,13,16,29 Next, we completed semi-structured qualitative interviews in 32 post-acute coronary syndrome patients in the PEACE I study. This work revealed that positive affect and optimism were associated with initiation and completion of physical activity,26 supporting use of a health behavior intervention that targets such constructs in this population. We also found that participants preferred a core intervention lasting 8 weeks (rather than the originally-planned 12) and completion of sessions by phone rather than in-person or over the internet, due to the logistical advantages and personal connection afforded by a phone-based program.

These findings informed the development of an 8-week phone based positive psychology intervention for acute coronary syndrome patients. In the PEACE II proof-of-concept trial (N=48), we assessed feasibility and accessibility of the intervention and compared psychological outcomes of the intervention group to those receiving treatment as usual. In treatment as usual, participants were free to receive any medical, rehabilitation, or mental health treatment, but no specific treatments were delivered. Feasibility and acceptability were assessed through exercise completion rates and participant ratings of ease/utility. Overall, 74% of intervention participants completed the majority of assigned exercises, and participants rated the ease (M=7.4/10; SD=2.1) and utility (M=8.1/10; SD=1.6) of the exercises highly. Compared to those receiving treatment as usual, those in the intervention group demonstrated greater improvements in positive affect, anxiety, and depression (effect size difference d=.47–.71).27

Following these promising results concerning the core intervention, the current PEACE III trial was developed as a “dose-finding” study to optimize the intervention’s effect on physical activity. Using a factorial design, we are testing three embedded comparisons: an intervention of solely positive psychology exercises versus a time-matched intervention combining positive psychology with motivational interviewing-based goal-setting, daily versus weekly positive psychology exercise frequency, and the presence versus absence of booster sessions.

We chose the positive psychology versus positive psychology-motivational interviewing comparison for several reasons. First, the former intervention would be simple and cost-effective, and involves constructs are linked with physical activity following an acute coronary syndrome.30 However, in some cases, psychological interventions alone have had limited effects on health behaviors in medically ill patients,16 while psychological interventions combined with specific behavioral interventions have had substantial effects.31 Motivational interviewing is appealing to combine with positive psychology, given that it has led to increased physical activity in patients with cardiac risk factors.32,33 It also integrates well with other treatments and has been successfully combined with additional interventions for weight control or health behaviors.34,35 However, used alone, it does not directly address positive constructs and has had only small-moderate effects on physical activity in cardiac and related conditions.32 Furthermore, specific subgroups may be less likely to benefit from motivational interviewing alone, such as those with low expectation of improvement or low overall optimism.36–38 The positive psychology component may however boost these factors and increase engagement in motivational interviewing.

On the other hand, though the combined and positive psychology-alone interventions are time-matched, the reduced time devoted to positive psychology skills in positive psychology-motivational interviewing may result in a lesser effect on psychological factors linked to physical activity, and a more singularly-focused positive psychology intervention may have greater efficacy. Furthermore, the positive psychology-alone intervention would have lower burden and cost compared to a combined intervention, and thus if positive psychology and positive psychology-motivational interviewing have very similar efficacy, we would likely select positive psychology.

Daily versus weekly completion of positive psychology activities was selected because more frequent completion of exercises could lead more quickly to improved well-being and stronger development of related skills. However, daily exercises may prove to be tedious or time-consuming in patients, and there is some evidence that intermittent completion of well-being-related tasks may have a greater effect than daily tasks.39 Finally, booster sessions to consolidate knowledge and behavior are increasingly used in health interventions,40–42 but they have had mixed results in behavioral intervention studies.43 Therefore, we aim to learn whether booster sessions are effective in consolidating skills during a vulnerable post-hospitalization period, or represent a sub-optimal burden on participants and resources.

To test these components, we will utilize a 2×2×2 complete factorial design, with a total of 8 conditions (Table 2), to assess which of these aspects of frequency, content, and duration are associated with the greatest improvement in accelerometer-measured physical activity at 16 weeks (the primary study outcome) in 128 post-acute coronary syndrome patients. Importantly, this is not an 8-arm trial; instead, the factorial design allows for the analysis of three embedded head-to-head trials (content/frequency/booster) with 64 participants in each group, collapsed across condition. Performing three separate experiments with N=128 for each outcome would provide no additional power to detect between group differences.

Table 2.

Treatment conditions

| Condition | Program Content | Exercise Frequency | Booster Sessions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PP only | Weekly | No |

| 2 | PP only | Daily | No |

| 3 | PP + MI | Weekly | No |

| 4 | PP + MI | Daily | No |

| 5 | PP only | Weekly | Yes |

| 6 | PP only | Daily | Yes |

| 7 | PP + MI | Weekly | Yes |

| 8 | PP + MI | Daily | Yes |

“PP only” = once weekly 30 minute phone call that reviews assigned PP reflective exercises (such as writing a letter of gratitude or performing kind acts).

“PP+MI” = a once weekly phone call with 15 minutes of PP review and 15 minutes of discussion of patient’s progress in an MI-basedgoal setting program (to increase physical activity). Participants in a PP+MI condition perform PP exercises identical in content to those with PP alone but in less depth in a shorter amount of time.

“Exercise frequency” = how frequently participants will complete the week’s positive psychology exercise.

“Booster sessions” = three additional sessions held every two weeks following the week 8 phone call.

Though the comparisons are largely at equipoise, we hypothesize that the combined intervention, weekly exercises, and the additional booster sessions will have greater effects on physical activity, given that existing evidence slightly favors each of these conditions.41,44,45

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Eligible patients are those suboptimal adherence to health behaviors admitted to inpatient cardiac units at one of two urban academic medical centers for an acute coronary syndrome. Diagnosis is based on established criteria used in similar prior studies.26,27,46 Adherence to diet, physical activity, and/or medication is determined using Medical Outcomes Study-Specific Adherence Scale47 items that inquire about the frequency of completing each behavior in the prior 4 weeks. Suboptimal adherence is defined as a total score of ≤14 on the three relevant items (maximum score of 18), or a total item score of 15 and a physical activity score of ≤5, as that is the primary study outcome. This cutoff score requires participants to have submaximal health behavior adherence, but allows inclusion of a majority of patients.

Exclusion criteria

Patients are excluded if they have: (1) cognitive deficits, determined via six-item cognitive screen,48 (2) medical conditions precluding interview or likely to be terminal within 6 months per chart review or the medical team, (3) inability to be physically active, or (4) inability to communicate in English (a future Spanish language intervention is planned).

Recruitment, enrollment, informed consent, and in-hospital session

Patients are identified via daily review of inpatient censuses, and those medically eligible are approached during hospitalization. For patients who agree to consider participation, a member of the study team describes potential risks/benefits, outlines study procedures, and performs assessments for exclusion criteria. For willing and eligible patients, study staff obtains written informed consent, and enrolled participants then complete baseline study outcome measures (Table 3). Next, participants are randomized to one of the eight study conditions, and the study interventionist provides the participant with the manual specific to that condition and conducts an initial in person session. This session includes an overview of positive psychology, introduction to the initial exercise, and instructions for post-discharge exercise completion.

Table 3.

Timeline of study assessments

| Outcome | Measure | Timing of Assessments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Weekly or biweekly phone calls | 8 weeks | 16 weeks* | ||

| PRIMARY AIM: Primary Outcome | |||||

| Physical activity (objective) | ActiGraph accelerometer | X | X | ||

| PRIMARY AIM: Secondary Outcomes | |||||

| Psychological Outcomes | |||||

| Positive affect | PANAS | X | X | X | |

| Optimism | LOT-R, LOT-R S | X | X | X | |

| Anxiety | HADS-A | X | X | X | |

| Depression | HADS-D | X | X | X | |

| Functional Outcomes | |||||

| Physical function | DASI | X | X | X | |

| Health-related quality of life | SF-12 | X | X | X | |

| Self-reported Adherence | |||||

| Health behavior adherence | MOS-SAS | X | X | X | |

| Physical activity | PAR | X | X | X | |

| Diet | MEDFICTS | X | X | X | |

| Medication adherence | SRMA | X | X | X | |

| Cigarette use | X | X | X | ||

| Objective Adherence | |||||

| Medication adherence | MEMSCap pill bottle | X** | |||

| SECONDARY AIM | |||||

| Feasibility | Number of sessions completed | X | |||

DASI=Duke Activity Status Index; HADS-A=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; LOT-R=Life Orientation Test-Revised; LOT-R S=Life Orientation Test-Revised State; MOS-SAS=Medical Outcomes Study Specific Adherence Scale; PAR=Modified Physical activity recall; MEDFICTS=Meats, Eggs, Dairy, Frying Foods, In baked goods, Convenience foods, Table fats, Snacks Dietary Assessment; PANAS=Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PSS-4=Perceived Stress Scale (4 item); SF-12=Short Form 12. SRMA=Self-reported medication adherence, a percentage-based self-reported adherence measure

16 weeks is primary study time point

Participants use MEMSCap daily throughout study; device is collected at 16 weeks.

Participants randomized to positive psychology-motivational interviewing additionally undergo an introductory motivational interviewing session focused on gathering baseline physical activity information and preparing for the goal-setting aspect of the program. All subsequent exercises are assigned and reviewed over the phone. Because positive psychology and positive psychology-motivational interviewing sessions are time matched (~30 minutes/session), the former involve more extensive discussions of the prior week’s exercises, emotions experienced, rationale for each activity, and focus on skill-building.

Randomization, study conditions and program content

Randomization and study conditions

After baseline measures are collected, participants are randomized in blocks of 16 to one of the eight study conditions using the Stata ralloc procedure. This ensures equal distribution of each condition across the study’s duration.

Program content

The positive psychology exercises (Table 1) were selected based on their performance in prior studies and PEACE I qualitative interview data.27,49 All phone sessions involve review of the prior week’s exercise, with a focus on expanding participants’ skill in expressing/experiencing positive emotions and integrating related skills (e.g., increasing awareness of positive events, using one’s strengths) into daily life. Interventionists also discuss the rationale and logistics for the following week’s exercise. Between phone sessions, participants complete and write about the exercises by describing their activity in detail, outlining its immediate psychological impact, and discussing the cognitive/emotional effects of writing about (and recalling) the activity. To ensure intervention consistency, the exercises are assigned in the same sequence for all participants.

Table 1.

Positive Psychology exercise content

| Exercise title | Participant task (Daily condition) | Participant Task (Weekly condition) |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1: Gratitude for Positive Events12 | Recall and write about a positive event daily | Recall and record three such events from the week |

| Week 2: Using Personal Strengths12 | Choose one or two personal strengths and use them each day for the next week | Choose a personal strength and find a new way to use it in the next 24 hours |

| Week 3: Expressions of Gratitude/Gratitude letter12 | Write expressions of gratitude once daily thanking a person for an act of kindness | Write a single letter of gratitude thanking a person for an act of kindness |

| Week 4: Capitalizing on Positive Events69 | Identify one good event daily and “boost” the positive feelings by sharing the event with others or celebrating it in some way | Recall three good events over the course of the week and “boost” the positive feelings as in the daily condition |

| Week 5: Remembering Daily Successes/Remembering Past Success12, 70 | Identify and record a success every day, focusing on the feelings evoked and the skills necessary for that success | Identify and record a single prior success, focusing on feelings and skills as in daily condition |

| Week 6: Enjoyable and meaningful activities71 | Complete an activity daily that varies between those that bring immediate boosts in mood and those that are more deeply meaningful | Perform a total of three such activities over the course of the week |

| Week 7: Humor in Everyday Life72 | Recall one funny event daily and describe why the event was amusing | Recall three funny things from the prior week and describe why they were amusing |

| Week 8: Performing Acts of Kindness73 and Next Steps | Complete and reflect on one act of kindness daily. Discuss ways to use skills from the program in daily life going forward | Complete and reflect on three acts of kindness in one day. Discuss ways to use skills from the program in daily life going forward |

Following review of the positive psychology exercise, participants receiving motivational interviewing review progress on their physical activity goal from the prior week, review related topics, and set goals for the next week, using worksheet based modules in the manual (sessions are summarized in Table 4). These sessions follow a 5A’s model (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange) related to physical activity at all sessions, and each session also has a specific area of focus (e.g., activity tracking, managing slips). Should participants express an inability, lack of need, or unwillingness to set activity goals, modules for dietary and medication adherence are used instead. This approach was informed by our qualitative interviews with acute coronary syndrome patients, who endorsed preferences for positive psychology and motivational interviewing delivered separately along with positive psychology content focused on global cultivation of positive states rather than specifically concerning their cardiac illness.26 The goal is to have the initial positive psychology session component promote optimism, well-being, and motivation leading into the motivational interviewing component.

Table 4.

Motivational interviewing intervention summary

| MI Summary | |

|---|---|

| 5A’s model | Interventionists: (a) Ask about progress on the prior cognitive (e.g., pros/cons of becoming active) or activity goal, (b) Advise about the benefits of activity on health and function, (c) Assess current stage of change and barriers/facilitators to change, (d) Assist with setting a goal, and (e) Arrange the next week’s phone session. |

|

| |

| Session-specific topics | Week 1: Introduce tools: discussion of importance & confidence of making a change in physical activity and pros & cons of specific goals. |

| Week 2: Introduce activity tracking. | |

| Week 3: Introduce ‘SMART’ (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-based) goals. | |

| Week 4: Brainstorm concrete and social resources to help with goal attainment. | |

| Week 5: Review activity barriers and facilitators experienced thus far. | |

| Week 6: Discuss managing ‘slips.’ (revisited in Week 8) | |

| Week 7: Review tips for success, including using a workout buddy and controlling stress | |

| Booster sessions: Discuss ongoing progress, relapse prevention, and long-term goals. | |

Participants randomized to booster conditions have additional sessions during weeks 10, 12, and 14. These sessions emphasize regular completion of 1–2 participant selected positive psychology skills, in addition to tips for integrating practice of these skills in daily life (e.g., how to utilize activities when under stress). Positive psychology-motivational interviewing participants receiving boosters also discuss current physical activity, set goals for the coming two weeks, and review appropriate motivational interviewing skills, including managing slips and setting attainable goals. See Supplemental Material for sample manual.

Study outcomes

Outcome assessment procedures (Table 3)

Self-report measures of psychological, medical, and adherence outcomes are obtained at baseline, 8 weeks, and 16 weeks. At 8 and 16 weeks, participants wear an Actigraph G3TX wireless accelerometer (Actigraph, Pensacola, FL) to measure physical activity, and throughout participation electronic pillcaps (MEMSCap; AARDEX, Sien, Switzerland) are used to assess medication adherence.

Because participants are enrolled in the hospital, pre-admission baseline physical activity cannot be obtained via accelerometer. Therefore, to control for baseline activity in study analyses, a modified version of the 7-day Physical Activity Recall scale50 was administered to assess moderate or greater activity (consistent with the primary study outcome) over the last 7-day period of typical activity. This measure has been used for 30+ years, correlates with accelerometry,51 and is sensitive to change.52 It is also completed at follow-up as a secondary outcome measure.

Data collection for baseline characteristics

Baseline data is obtained from participants, care providers, and the electronic medical record to characterize our study population. This includes data regarding medical history (prior acute coronary syndrome or coronary artery bypass graft, cardiac risk factors), current medical variables (admission diagnosis, renal function, left ventricular ejection fraction), medications, length of hospitalization, and sociodemographic data (age, gender, race/ethnicity, living alone).

Study outcome measures: Primary aim

Primary outcome measure: Moderate to vigorous physical activity

We selected moderate to vigorous physical activity, physical activity requiring at least moderate effort and resulting in a notable increase in heart rate (e.g., brisk walking, dancing), as our activity metric given its clear association with health outcomes, including mortality.53 This will be measured using the GT3X accelerometer, which has been extensively used in activity research and adequately discriminates between different intensities of activity.54,55 Devices are sent to patients at weeks 8 and 16, with instructions to wear the device for 10 days. Based on published work,56,57 minimum acceptable use is 4+ days with 8+ hours of recorded data. We will use previously-reported cutoffs (in counts/minute) for activity and non-wear time, including 1952 counts/minute for moderate to vigorous physical activity.58,59

Secondary outcome measures: Psychological outcomes

Positive affect (the primary psychological outcome given its links to cardiac outcomes and its responsiveness to change) is assessed with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, a frequently-used scale that inquires about affect “during the past few weeks.”60 Optimism is measured using the Life Orientation Test-Revised, an established six-item scale previously used in cardiac patients.61 Though designed to measure dispositional optimism, Life Orientation Test-Revised scores have been dynamic over weeks in response to a positive psychology intervention.62 Anxiety and depression are measured using the relevant subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, a well-validated instrument designed for medically-ill patients.63

Functional outcomes

The Duke Activity Status Index and Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 are used to assess physical function and health-related quality of life, respectively. The former has been extensively studied in cardiac patients64–66 and is reliable, valid, and responsive to change.67 The Short Form-12 has likewise been used in cardiac patients to assess health-related quality of life,68–70 and provides component scores for mental/physical components of this outcome.

Additional health behavior outcomes

For medication adherence, MEMSCaps are used throughout study participation to measure daily aspirin administration (or other once-daily cardiac medication in the very rare event that aspirin is not prescribed). MEMSCaps are well-validated71,72 and use a pill bottle with an accompanying cap that records opening/closing of the bottle.

Regarding self-reported health behavior adherence, the three Medical Outcomes Study-Specific Adherence Scale items used for eligibility assessment at baseline are repeated at 8 and 16 weeks as a study outcome measure. For dietary adherence, participants also complete the MEDFICTS scale,73 a National Cholesterol Education Program-developed scale inquiring about saturated fat. Medication adherence is additionally assessed using a two-item percentage-based self-report measure shown to correlate highly with pillcap measurement.74 Finally, cigarette use is determined by a team-developed four-item measure to assess 7-day point prevalence; such methods match longer-term assessments and are responsive to change.75,76

Study outcome measures: feasibility and acceptability (secondary aim)

To assess intervention feasibility, rates of session completion (completing both the prior week’s positive psychology activity and the phone session) and completion of study follow-up assessments (self-report assessments, accelerometers, and electronic pillcaps) are used. For acceptability, participants are asked weekly, “Overall, how helpful do you feel this exercise was?” on a Likert scale from 0 (not helpful) to 10 (very helpful); a question on ease of exercise completion uses the same scale. Participants likewise rate positive affect and optimism (0–10) immediately before and after completing the assigned positive psychology exercise for that week. These ratings are recorded by interventionists at weekly calls.

Statistical methods

Primary aim

Power considerations

With a sample size of 128 subjects and equal allocation to each treatment arm, 64 subjects will contribute to each treatment comparison, and 16 subjects will be allocated to each combination of three treatments. Using the full factorial analysis approach described in Collins et al, 77 we will have 80% power to detect treatment main effects based on effect coding equal to 0.5 times the residual standard deviation of daily moderate to vigorous physical activity minutes at the two sided 0.05 level, which corresponds to a moderate effect size for each of the main effects. The power was estimated based on a simulation study (R code available from author upon request), and the estimated power was the same in the presence or absence of treatment interactions in this model. Our final analysis will also control for baseline physical activity measured by the Physical Activity Recall, likely increasing the study’s power to detect group differences in this outcome. The p value will not be the sole criterion on which decisions (such as selecting conditions) are made, as we also consider magnitude of effect and burden/cost.

Primary outcome analyses

Moderate to vigorous physical activity at weeks 8 and 16 will be analyzed jointly using a random effects model with a random intercept for each participant. This model allows us to include participants who have some missing data rather than dropping such participants. The model will include main effects and interaction for each intervention, a main effect for time point and interactions between time point and each of the main effect and interaction terms for the interventions. In addition, we will include baseline activity measured via Physical Activity Recall. Sixteen weeks is the primary time point for all analyses, with 8 weeks secondary. Using this model, we will be able to assess the main effect of each of the three intervention components at each time point (e.g., boosters versus no boosters), and we will also be able to assess any interactions between the components. In terms of choosing the final intervention to investigate in later studies, we will follow a published framework for decision-making based on factorial experiments.77 Using this, we will assess the effect of each intervention and potential interactions using statistical significance, and will also consider effect size measures and patient burden. Given the exploratory nature of this component-testing/optimization trial, we will use the traditional p=.05 for significance.

Secondary outcome analyses

To assess the effect of each component on self-reported psychological/functional outcomes at 8 and 16 weeks, we will use an analysis of response profiles model with a categorical effect of time and an unstructured covariance matrix.78 We will include the baseline measurement of each outcome in the analysis and assume a common baseline across treatment groups, since participants are randomized; this approach provides the power advantages of an analysis of covariance model.79 As with the primary analysis, each intervention will be included in the model as a fixed effect in a full factorial model.

For objectively-assessed medication adherence, we will compare groups on medication adherence (% of days with single pillcap turn) at 16 weeks, controlling for baseline medication adherence (measured via the two-item self-report measure), using random effects models. All analyses will be repeated for the secondary 8-week time point.

Secondary aim (Feasibility/Acceptability)

For feasibility, we will calculate proportions of completed sessions and follow-up assessments. Likewise, for acceptability, descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) will be used to summarize ratings of exercise ease and utility. For pre-post differences in positive affect, generalized estimating equation models with an exchangeable working correlation structure and robust standard errors will be used to account for intra-participant correlation. The intervention will be considered feasible and acceptable if ≥70% of all sessions are completed, outcomes data (self-report and objective) is obtained in 80% of participants, and there are significant pre-post increases from baseline in positive affect (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule) at 16 weeks across all participants. Analyses will be performed using Stata 14.0 (College Station, TX), and all analyses will be two-tailed with p<.05 considered significant.

Results

Thus far, we have enrolled 78 participants, and the trial is on target to complete enrollment within 24 months, as originally projected. Study procedures have proven feasible thus far. Across all intervention groups, among the first 61 participants, the intervention has been well-accepted, with 72% (349/488) of possible exercises completed.

Comment

PEACE III contributes to the current literature in several novel ways. First, it is the first study to test the effects of positive psychology on secondary prevention in post-acute coronary syndrome patients, a major public health priority.80 Second, using a factorial design, PEACE III represents the optimization phase of a MOST-based strategy to carefully develop a positive psychology-based intervention through efficient resource use and continuous optimization. Multiphase trial designs are increasingly used for type II translational research, including the recent NIH ORBIT initiative81 to develop obesity prevention and reduction strategies. These methods of iterative development for behavioral interventions should allow for more systematic generation of effective interventions that can have a major public health impact. The optimized intervention from PEACE III will be examined in a pilot study (PEACE IV) in preparation for a subsequent well-powered randomized trial in the evaluation stage of the MOST process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project is funded via the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant number R01HL113272 to Dr. Jeff Huffman; time for manuscript development has also been supported by K23HL123607 to Dr. Christopher Celano.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeo KK, Fam JM, Lim ST, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics, 1-year readmission rates, cost and mortality amongst patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for stable angina, acute coronary syndromes and ST-elevation myocardial infarction. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:295. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow CK, Jolly S, Rao-Melacini P, et al. Association of diet, exercise, and smoking modification with risk of early cardiovascular events after acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2010;121:750–758. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.891523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gehi AK, Ali S, Na B, et al. Self-reported medication adherence and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the heart and soul study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1798–1803. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sud A, Kline-Rogers EM, Eagle KA, et al. Adherence to medications by patients after acute coronary syndromes. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1792–1797. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steptoe A, Wright C, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, et al. Dispositional optimism and health behaviour in community-dwelling older people: associations with healthy ageing. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(Pt 1):71–84. doi: 10.1348/135910705X42850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelloniemi H, Ek E, Laitinen J. Optimism, dietary habits, body mass index and smoking among young Finnish adults. Appetite. 2005;45:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giltay EJ, Geleijnse JM, Zitman FG, et al. Lifestyle and dietary correlates of dispositional optimism in men: the Zutphen Elderly Study. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leedham B, Meyerowitz BE, Muirhead J, et al. Positive expectations predict health after heart transplantation. Health Psychol. 1995;14:74–79. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen HN, Scheier MF, Greenhouse JB. Optimism and physical health: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:239–256. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9111-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tindle HA, Chang YF, Kuller LH, et al. Optimism, cynical hostility, and incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative. Circulation. 2009;120:656–662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seligman M, Steen T, Park N, et al. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Ann Psychol. 2005;60:410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moskowitz JT, Hult JR, Duncan LG, et al. A positive affect intervention for people experiencing health-related stress: development and non-randomized pilot test. J Health Psychol. 2012;17:676–692. doi: 10.1177/1359105311425275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogedegbe GO, Boutin Foster C, Wells MT, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:322–326. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohn MA, Pietrucha ME, Saslow LR, et al. An online positive affect skills intervention reduces depression in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Posit Psychol. 2014;9:523–534. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.920410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson M, Boutin-Foster C, Mancuso C, et al. Randomized controlled trials of positive affect and self-affirmation to facilitate healthy behaviors in patients with cardiopulmonary diseases. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huffman JC. Development of a positive psychology intervention for patients with acute cardiovascular disease. Psychosom Med. 2011;6:e14. doi: 10.4081/hi.2011.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopf S, Oikonomou D, Hartmann M, et al. Effects of stress reduction on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes patients with early kidney disease: results of a randomized controlled trial (HEIDIS) Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2014;122:341–349. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Heijden MM, Pouwer F, Romeijnders AC, et al. Testing the effectiveness of a self-efficacy based exercise intervention for inactive people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:331. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson LE. Mindfulness-based interventions for physical conditions: a narrative review evaluating levels of evidence. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012:651583. doi: 10.5402/2012/651583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, et al. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.University of Massachusetts Medical School. Mindfulness-based stress reduction 8-week program. http://www.umassmed.edu/cfm/stress-reduction/mbsr-8-week (Accessed 17 November 2015)

- 24.Collins LM, Kugler KC, Gwadz MV. Optimization of multicomponent behavioral and biobehavioral interventions for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S197–S214. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1145-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins LM, Baker TB, Mermelstein RJ, et al. The multiphase optimization strategy for engineering effective tobacco use interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:208–226. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9253-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huffman JC, DuBois CM, Mastromauro CA, et al. Positive psychological states and health behaviors in acute coronary syndrome patients: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1026–1036. doi: 10.1177/1359105314544135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huffman J, Millstein R, Mastromauro C, et al. A positive psychology intervention for patients with an acute coronary syndrome: treatment development and proof-of-concept trial. J Happiness Stud. 2015:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9681-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 3rd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huffman J, Mastromauro C, Boehm J, et al. Development of a positive psychology intervention for patients with acute cardiovascular disease. Heart Int. 2011;6:e14. doi: 10.4081/hi.2011.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huffman JC, Beale EE, Celano CM, et al. Effects of optimism and gratitude on physical activity, biomarkers, and readmissions after an acute coronary syndrome: The Gratitude Research in Acute Coronary Events Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:55–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Wexler DJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:625–633. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avery L, Flynn D, van Wersch A, et al. Changing activity behavior in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2681–2689. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma C, Zhou Y, Zhou W, et al. Evaluation of the effect of motivational interviewing counselling on hypertension care. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ismail K, Maissi E, Thomas S, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy and motivational interviewing for people with type 1 diabetes mellitus with persistent sub-optimal glycaemic control. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–101. doi: 10.3310/hta14220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith DE, Kratt PP, Mason DA. Motivational interviewing to improve adherence to a behavioral weight-control program for older obese women with NIDDM. A pilot study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:52–54. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goossens ME, Vlaeyen JW, Hidding A, et al. Treatment expectancy affects the outcome of cognitive-behavioral interventions in chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:18–26. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph CL, Havstad SL, Johnson D, et al. Factors associated with nonresponse to a computer-tailored asthma management program for urban adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2010;47:667–673. doi: 10.3109/02770900903518827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheier MF, Helgeson VS, Schulz R, et al. Moderators of interventions designed to enhance physical and psychological functioning among younger women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5710–5714. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyubomirsky S, Layous K. How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yates BC, Anderson T, Hertzog M, et al. Effectiveness of follow-up booster sessions in improving physical status after cardiac rehabilitation: health, behavioral, and clinical outcomes. Appl Nurs Res. 2005;18:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le HN, Perry DF, Stuart EA. Randomized controlled trial of a preventive intervention for perinatal depression in high-risk Latinas. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:135–141. doi: 10.1037/a0022492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mangels M, Schwarz S, Worringen U, et al. Evaluation of a behavioral-medical inpatient rehabilitation treatment including booster sessions: a randomized controlled study. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:356–364. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181925791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashby WA, Wilson GT. Behavior therapy for obesity: booster sessions and long-term maintenance of weight loss. Behav Res Ther. 1977;15:451–463. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(77)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: the architecture of sustainable change. Rev Gen Psychol. 2005;9:111–131. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martins RK, McNeil DW. Review of motivational interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1581–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiMatteo MR, Hays RD, Sherbourne CD. Adherence to cancer regimens: implications for treating the older patient. Oncology. 1992;6(2 Suppl):50–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, et al. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huffman JC, DuBois CM, Healy BC, et al. Feasibility and utility of positive psychology exercises for suicidal inpatients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71(2 Suppl):S1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blair SN, Haskell WL, Ho P, et al. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:794–804. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loprinzi PD, Loenneke JP, Ahmed HM, et al. Joint effects of objectively measured sedentary time and physical activity on all-cause mortality. Prev Med. 2016;90:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welk G. Physical activity assessments for health-related research. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Copeland JL, Esliger DW. Accelerometer assessment of physical activity in active, healthy older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2009;17:17–30. doi: 10.1123/japa.17.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cain KL, Conway TL, Adams MA, et al. Comparison of actiGraph accelerometers with the normal filter and the low frequency extension. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:51. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cain KL, Geremia CM. Accelerometer data collection and scoring manual for adult & senior studies. http://sallis.ucsd.edu/Documents/Measures_documents/Accelerometer_Data_Collection_and_Scoring_Manual_Updated_June. (2012, accessed 16 December 2015)

- 58.Choi L, Ward SC, Schnelle JF, et al. Assessment of wear/nonwear time classification algorithms for triaxial accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2009–2016. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318258cb36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Copeland JL, Esliger DW. Accelerometer assessment of physical activity in active, healthy older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2009;17:17–30. doi: 10.1123/japa.17.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McClure JB, Ludman E, Grothaus L, et al. Immediate and short-term impact of a motivational smoking intervention using a biomedical risk assessment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:394–403. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DuBois CM, Lopez OV, Beale EE, et al. Relationships between positive psychological constructs and health outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2015;195:265–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.05.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meevissen YM, Peters ML, Alberts HJ. Become more optimistic by imagining a best possible self: effects of a two week intervention. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ellis JJ, Eagle KA, Kline-Rogers EM, et al. Perceived work performance of patients who experienced an acute coronary syndrome event. Cardiology. 2005;104:120–126. doi: 10.1159/000087410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grodin JL, Hammadah M, Fan Y, et al. Prognostic value of estimating functional capacity with the use of the Duke Activity Status Index in stable patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2015;21:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wessel TR, Arant CB, Olson MB, et al. Relationship of physical fitness vs body mass index with coronary artery disease and cardiovascular events in women. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;292:1179–1187. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alonso J, Permanyer-Miralda G, Cascant P, et al. Measuring functional status of chronic coronary patients. Reliability, validity and responsiveness to clinical change of the reduced version of the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) Eur Heart J. 1997;18:414–419. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ni H, Toy W, Burgess D, et al. Comparative responsiveness of Short-Form 12 and Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2000;6:83–91. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2000.7869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garavalia LS, Decker C, Reid KJ, et al. Does health status differ between men and women in early recovery after myocardial infarction? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:93–101. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thombs BD, Ziegelstein RC, Stewart DE, et al. Usefulness of persistent symptoms of depression to predict physical health status 12 months after an acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kronish IM, Rieckmann N, Burg MM, et al. The psychosocial context impacts medication adherence after acute coronary syndrome. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:158–164. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9544-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ingerski LM, Hente EA, Modi AC, et al. Electronic measurement of medication adherence in pediatric chronic illness: a review of measures. J Pediatr. 2011;159:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gonzalez JS, Schneider HE, Wexler DJ, et al. Validity of medication adherence self-reports in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:831–837. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ, Naud S. Do point prevalence and prolonged abstinence measures produce similar results in smoking cessation studies? A systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:756–762. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO. A comparison of four self-report smoking cessation outcome measures. Addict Behav. 2004;29:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Collins LM, Trail JB, Kugler KC, et al. Evaluating individual intervention components: making decisions based on the results of a factorial screening experiment. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4:238–251. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0239-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. 2nd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu GF, Lu K, Mogg R, et al. Should baseline be a covariate or dependent variable in analyses of change from baseline in clinical trials? Stat Med. 2009;28:2509–2530. doi: 10.1002/sim.3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith SC, Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2011;124:2458–2473. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318235eb4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, et al. From ideas to efficacy: the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015;34:971–982. doi: 10.1037/hea0000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.