Abstract

Background

Ethics in health care and research is based on the fundamental principle of informed consent. However, informed consent in geriatric dentistry is not well documented. Poor health, cognitive decline, and the passive nature of many geriatric patients complicate this issue.

Methods

The authors completed this systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. The authors searched the MEDLINE PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library databases. The authors included studies if they involved participants 65 years or older and discussed topics related to informed consent beyond obtaining consent for health care. The authors explored informed consent issues in dentistry and other biomedical care and research.

Results

The authors included 80 full-text articles on the basis of the inclusion criteria. Of these studies, 33 were conducted in the United States, 30 addressed consent issues in patients with cognitive impairment, 29 were conducted in patients with medical issues, and only 3 involved consent related to dental care or research.

Conclusions

Informed consent is a neglected topic in geriatric dental care and research. Substantial knowledge gaps exist between the understanding and implementation of consent procedures. Additional research in this area could help address contemporary consent issues typically encountered by dental practitioners and to increase active participation from the geriatric population in dental care and research.

Practical Implications

This review is the first attempt, to the authors’ knowledge, to identify informed consent issues comprehensively in geriatric dentistry. There is limited information in the informed consent literature covering key concepts applicable to geriatric dentistry. Addressing these gaps could assist dental health care professionals in managing complex ethical issues associated with geriatric dental patients.

Keywords: Ethics, informed consent, competency, dental care, dental care for elderly patients, geriatrics, oral health, dental research

Informed consent is fundamental to the ethics of clinical care and research involving people. Although it is typically the ethical responsibility and legal duty of health care professionals to obtain valid informed consent from patients and research participants, consent is not always well interpreted or well documented in practice. Previous research results show that 40% to 80% of research participants who initially were judged to be capable of giving consent did not recall 1 or more required elements of the consent information.1,2 Obtaining informed consent is more than the act of a patient signing a document. It encompasses communication between participants and their care providers or research investigators. The overarching goal is to ensure that patients or study participants have full understanding of the clinical and research procedures that will be performed, including the expected risks and benefits and alternatives that are available to them; are given the opportunity to ask questions, discuss their choice, and have time to reflect; and provide a clear indication of their eventual decision.3

In dentistry, informed consent typically is viewed through a legal lens. It sometimes is seen as a challenge to customary practice or is viewed with uncertainty because it may not be clear whether a person can provide valid legal consent for treatment or participation in a study. Informed consent should include 5 basic elements:

-

▬

Capacity implies the physical and cognitive ability to participate fully in the informed consent process. Capacity involves the following: ability to comprehend the information provided by the dentist, ability to weigh the treatment options on the basis of one’s beliefs and values, and ability to reach an independent reasonable decision or choice.4

-

▬

Information should be disclosed to the patient about his or her dental problems and the nature, risks, and benefits of the proposed treatment and other treatment alternatives available to the patient, including nontreatment.5

-

▬

Comprehension or understanding of the consent process and information provided by the dentist is necessary for valid consent. The dentist must engage the patient actively in conversation, clarify the issues, answer questions, and verify that the patient has understood the information provided.4

-

▬

Ensuring voluntariness protects the participant’s right to make his or her own decisions. A consent decision should not be coerced or manipulated either by the dentist or by family members.6 Nevertheless, if the dentist thinks that the course chosen by the patient will do more harm than good to the patient, the dentist should communicate his or her concerns and reasons in an attempt to persuade the patient to reconsider.7 If the dentist knowingly fails to do so, it is a violation of the ethical principle of beneficence.

-

▬

Final decision or choice is essential to complete the act of giving consent. The decision about whether to give consent may be communicated orally or in writing, though in many contexts written documentation is required.

Obtaining informed consent can be especially challenging when it involves geriatric patients, who constitute a substantial and growing proportion of the population. The US Census Bureau projects that by 2030, more than 20% of the population will be 65 years or older compared with 13% in 2010.8 With a growing geriatric population that increasingly will retain their natural teeth, a larger number of older people will be seeking dental care in the upcoming years.

Many older adults have multiple comorbidities, somatic and psychosocial disabilities, and impaired decision-making capacity. Scholars have suggested that many people, possibly as a result of continuing perceptions of what a proper doctor-patient relationship is, prefer not to be involved in difficult decision-making processes regarding health care.9,10 Many find it too overwhelming to comprehend diagnostic information and treatment options, to weigh risks and benefits, and to reach a decision independently. They tend to rely on their health care provider or a trusted family member or caregiver to decide on their behalf.

Typically, the topic of informed consent is introduced to predoctoral dental students as theory. However, no standardized approach to teaching dental ethics has been established, and more education does not necessarily imply better understanding or ability to deal with ethical issues in professional life.11 The topic of informed consent in geriatric populations seeking dental care or participating in dental research has not been documented or studied widely. We aimed to explore systematically important issues that affect the informed consent process applicable to a geriatric population to help inform dental health care professionals providing dental care or conducting oral health research with older adults.

METHODS

We completed this systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.12 We developed 3 research questions to guide this systematic review:

-

▬

When is an elderly person capable of providing his or her own consent?

-

▬

Is the practice of obtaining informed consent in elderly patients for the provision of dental care or treatment different from that for other medical care?

-

▬

Is the practice of obtaining informed consent in elderly patients for participation in dental research different from that for other medical research?

Operational definitions

For the purposes of this review, we used the following operational definitions:

-

▬

Frail elderly are people with multiple comorbidities and functional disabilities at the somatic and psychosocial levels who need help with the activities of daily living.

-

▬

Capacity is the ability to understand and process the information provided and to reach an independent decision with respect to individual preferences and values.4 We classified participants as capable or noncapable on the basis of their ability to provide valid consent.

-

▬

Autonomy is self-governance, understood as the capacity to make one’s own decisions and the opportunity to do so voluntarily (without any outside coercion or manipulation).

-

▬

Comprehension and understanding is being able to understand, process, or retain the information provided by the care provider or research team.

-

▬

Geriatric assent involves actively engaging patients 65 years or older in any major decisions made by health care professionals or family members.

Study inclusion criteria

We selected studies if they included an elderly population (65 years or older) and discussed informed consent beyond noting that informed consent was obtained from the patient or participant. In addition, the article’s authors had to discuss the provision of dental care or dental treatment or other medical care (question 2) or dental research or medical or biomedical research (question 3). We excluded meeting or poster abstracts. To reflect potential conceptual changes as a result of the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005, we excluded articles published before 2005.

Search strategy

One of us, a medical librarian (A.A.L.), searched the MEDLINE PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO (American Psychological Association), and Cochrane Library (Wiley) databases in December 2015. We used a combination of controlled vocabulary terms (that is, Medical Subject Headings) and keywords to search for each of the concepts of interest: geriatric population, informed consent concepts, dental or medical research, and dental or medical care. We adapted the search strategies used for each database (see eTable 6, available online at the end of this article). We limited articles to English language only. Each research question contained its own set of search results. We reviewed each research question independently, so we did not remove the citations retrieved for each of the 3 research questions. We exported search results from each database to EndNote X7 (Clarivate Analytics) for citation management and removal of duplicate citations retrieved for each question, and we used Excel (Microsoft) for citation review. eTable 6 (available online at the end of this article) provides a detailed description of the search strategy.

Screening

Two of us (A.M., S.C.) completed a title and abstract screen of all retrieved citations in December 2015 by using the inclusion criteria for each research question. We selected those marked yes by both the reviewers for full-text review. A third reviewer (S.B.) reviewed citations marked yes by either of the 2 reviewers and no or “don’t know” by the second reviewer to determine inclusion. We included articles marked yes by the third reviewer for full-text review. Using the inclusion criteria, 2 of us (A.M., B.A.D.) retrieved and reviewed the full text of the included articles.

Data abstraction and management

For studies eligible for full-text review, 2 of us (A.M., B.A.D.) extracted data in the form of 5 data abstraction tables. Table 1 presents information about the article type, population age and setting, health condition, and consent topics discussed. Table 2 presents the issues of capacity assessment and declining capacity. In Table 3, we extracted data regarding elements and concepts of consent that included autonomy or voluntariness. In Table 4, we extracted data on patient understanding. In Table 5, we collected data on surrogates and geriatric assent. We used Excel (Microsoft) for data abstraction.

TABLE 1.

Number of articles included in the systematic review according to article type, location, and informed consent topic for cognitive, medical, and dental conditions.

| HEALTH CONDITION OR TOPIC | ARTICLE TYPE | GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION | INFORMED CONSENT TOPIC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | Survey | Essay | United States | Europe | Elsewhere | Capacity | Elements and Concepts | Understanding | Surrogates and Assent | |

| Cognitive | 19 | 4 | 6 | 16 | 9 | 4 | 19 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Physical and Medical | 24 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 22 | 18 | 19 |

| Dental | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Both Cognitive and Medical | 12 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 11 | 15 | 12 | 11 |

| Total | 57 | 7 | 16 | 33 | 35 | 12 | 39 | 56 | 49 | 49 |

TABLE 2.

Number of articles included in the systematic review according to decision-making capacity and capacity assessment for cognitive, medical, and dental conditions.

| HEALTH CONDITION OR TOPIC | KEY CONCEPTS OF CAPACITY DISCUSSED | CAPACITY MEASUREMENT INSTRUMENTS USED* | DISCUSSION OF DECREASING CAPACITY | APPLIED TO RESEARCH, USUAL CARE, OR BOTH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-Making Capacity: Definition and Factors Affecting It, Declining Capacity | Capacity Assessment | Standardized Tool | Questionnaires | None | Yes | No | Research | Care | Both | |

| Cognitive | 9 | 16 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 1 |

| Physical and Medical | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Dental | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Both Cognitive and Medical | 7 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 24 | 33 | 26 | 4 | 9 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 15 | 5 |

The investigators assessed capacity by using the following instruments: Assessment of Capacity for Everyday Decision-Making, Capacity to Consent to Treatment Instrument, Clinical Dementia Rating, Clock Drawing Test, Confusion Assessment Method, Delirium Rating Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly, MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool, Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Reversible Cognitive Dysfunction Scale, and University of California Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent.

TABLE 3.

Number of articles included in the systematic review according to elements and concepts of informed consent for cognitive, medical, and dental conditions.

| HEALTH CONDITION OR TOPIC |

CONCEPTS OF INFORMED CONSENT DISCUSSED |

KEY INFORMATION REQUIREMENTS FOR CONSENT DISCUSSED |

AUTOMONY DISCUSSED* |

CONSENT URGENCY | APPLIED TO RESEARCH, USUAL CARE, OR BOTH |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosure of Risk, Benefits, and Alternatives |

Assessment of Decision- Making Capacity |

Voluntariness or Choice Without Coercion |

Morbidity and Mortality |

Quality of Life |

Not Indicated |

Yes | Emergency | Nonemergency | Research | Care | Both | |

| Cognitive | 12 | 11 | 13 | 4 | 11 | 5 | 13 | 2 | 14 | 9 | 6 | 1 |

| Physical and Medical | 19 | 9 | 17 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 15 | 10 | 16 | 3 | 13 | 6 |

| Dental | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Both Cognitive and Medical | 14 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 12 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 48 | 32 | 43 | 16 | 36 | 16 | 43 | 15 | 45 | 24 | 25 | 7 |

Autonomy primarily focuses on the right to refuse.

TABLE 4.

Number of articles included in the systematic review according to patient understanding for cognitive, medical, and dental conditions.

| HEALTH CONDITION OR TOPIC | CONCEPTS OF UNDERSTANDING DISCUSSED | ASSESSING UNDERSTANDING AS IT RELATES TO INFORMED CONSENT | APPLIED TO RESEARCH, USUAL CARE, OR BOTH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prestudy Information or Pretreatment Information Provided | Decision Aids to Improve Understanding | Standardized Tool | Provider or Investigator Assessed | Questionnaires | Not Indicated | Research | Care | Both | |

| Cognitive | 17 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 2 |

| Physical and Medical | 18 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 4 |

| Dental | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Both Cognitive and Medical | 12 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 49 | 23 | 5 | 7 | 22 | 16 | 28 | 15 | 7 |

TABLE 5.

The number of articles included in the systematic review according to proxy or surrogates for cognitive, medical, and dental conditions.

| HEALTH CONDITION OR TOPIC | ROLE OF SUUROGATES | GERIATRIC ASSENT DISCUSSED | APPLIED TO RESEARCH, USUAL CARE, OR BOTH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proxy Decision Making: Best Interest Versus Substituted Judgment | Effect of Relatives or Companions on Decision Making and Understanding | Acquire Directly or Advance Directives | Not Discussed | Research | Care | Both | |

| Cognitive | 13 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

| Physical and Medical | 14 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 8 | 7 |

| Dental | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Both Cognitive and Medical | 10 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 38 | 28 | 29 | 20 | 21 | 19 | 9 |

RESULTS

Study identification and inclusion

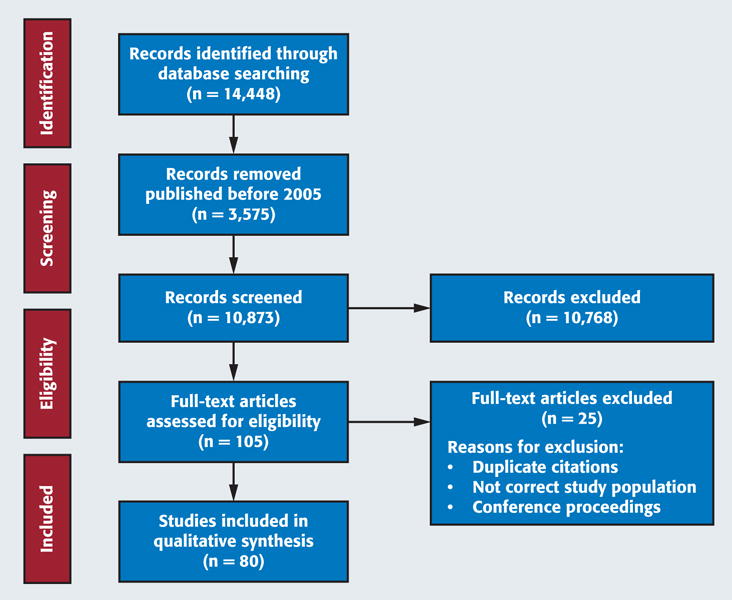

We identified 14,448 articles through electronic database searching (Figure). We excluded articles published before 2005 (n = 3,575). We screened titles and abstracts for 10,873 articles, and we excluded 10,768 on the basis of the inclusion criteria. Of the 105 remaining articles, we excluded 25 either for being duplicates or for not satisfying the inclusion criteria, resulting in a final set of 80 articles13–92 for full-text review (Table 1). We present an expanded description of the articles reviewed in eTables 1–5(available online at the end of this article).

Figure.

Flow diagram of the literature search and screening process. Source: Moher and colleagues.12

Article characteristics

Of the 80 articles, 16 were essay-type articles16,20,23,27,30,33,37,42,64,65,67,68,71,72,81,91; 7 were surveys18,19,46,47,73,75,85; and 57 were research articles consisting of case studies and case reports, follow-up studies, cross-sectional studies, case-control and cohort studies, randomized trials, and systematic reviews.13–15,17,21,22,24–26,28,29,31,32,34–36,38–41,43–45,48–63,66,69,70,74,76–80,82–84,86–90,92 The studies reviewed were from a variety of international settings: United States (n = 33); United Kingdom (n = 7); France (n = 5); the Netherlands (n = 5); Spain (n = 3); and Canada, Sweden, Finland, Germany, Switzerland, Turkey, Hong Kong, Scotland, Norway, Italy, South Africa, Israel, Korea, Austria, and Nigeria. Investigators in 29 studies discussed consent in patients with only medical conditions, 29 in patients with cognitive impairments only, and 19 in patients with both medical and cognitive issues or frail or vulnerable elderly (eTable 1, available online at the end of this article). Investigators in only 3 studies70,78,81 discussed consent issues related to dentistry (Table 1). Rubinos Lopez and colleagues70 discussed elements and understanding in a Spanish dental care unit; Taiwo and Kass78 discussed elements and concepts of informed consent and patient understanding of oral health research in Nigeria; and Van and colleagues81 focused on elements, capacity, surrogates, and assent in a group of cognitively impaired geriatric patients seeking dental care in the United States.

Investigators in 39 articles discussed capacity; 19 were in research settings, 15 were in clinical care settings, and 5 involved both research and care (Table 2). Investigators in 24 articles discussed decision-making capacity, and investigators in 33 articles discussed capacity assessment topics. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool (MacCAT) were the most commonly used capacity assessment tools, with MMSE mentioned in 23 articles and MacCAT in 13 articles (eTable 2, available online at the end of this article). The investigators mentioned declining capacity in 20 of the 39 articles with major emphasis on the concept of advance directives. Only 1 dental-related article focused on capacity.81 The authors discussed the importance of capacity evaluation in the dental office and suggested that a patient’s history and a long-standing patient-dentist relationship might help in detecting possible cognitive decline.

Table 3 presents key concepts of consent and autonomy discussed in the reviewed studies. Investigators in 48 articles discussed disclosure of risk, benefits, and alternatives. Investigators in 43 articles discussed patient autonomy; 3 were in dental settings.70,78,81 Arias15 and Basta16 stated that patients’ decisions always should be respected, and Davies and colleagues24 stated that patients should be made aware that they may withdraw from the research or treatment at any time, without any legal binding or penalty. Clayman and colleagues22 discussed autonomy-enhancing and autonomy-detracting behaviors of patient companions. Of the 3 studies in which the investigators discussed consent in dental settings, Taiwo and Kass78 stated that most of the patients in oral research settings in Nigeria were not aware of the concept of autonomy.

Investigators in more articles discussed patient understanding in the context of research (n = 28) than did those in the context of patient care (n = 15), and 7 articles were applicable to both research and care. Mostly researchers used questionnaires to assess patient understanding (Table 4). Investigators in 3 studies mentioned use of the MacCAT for Clinical Research understanding scale.38,62,66 Information provided to patients, physician’s communication with patients, role of medical staff, and patient companions are some of the factors that affect patient understanding.21,22,35 Investigators in 5 studies suggested educational intervention or computer-based tutorials to improve patient understanding.26,29,42,76,90 Other aids to decision making that could improve patient understanding are visual aids,33,37,38,42,79 audiotapes,33,37,38,42 photographs, diagrams, and vignettes.33,38,42 Investigators in 6 studies discussed readability level and level of vocabulary used in informed consent forms.37,42,53,56,76,79 Investigators in 1 dental research78 and 1 dental care article70 discussed patient understanding.

Table 5 presents details of studies presenting issues regarding the role of surrogates and assent in the decision-making process. Investigators in 38 articles discussed proxy decision making. Investigators in 28 articles discussed the effect of relatives or companions on decision making. Investigators discussed advance care planning, advance directives, and shared decision making under the topic of geriatric assent. Coverdale and colleagues23 proposed a 4-step approach to obtaining geriatric assent: identifying patient’s values and preferences, assessing plans of care in terms of safety and the patient’s values, protecting remaining autonomy, and cultivating the professional virtues of making decisions under conditions of risk.

DISCUSSION

The investigators in the 80 articles included in this systematic review discussed informed consent substantively—that is, beyond noting that consent was obtained from the patient or participant. However, investigators in only 3 of the 80 articles discussed consent related to dentistry in the geriatric population.70,78,81 Most of the studies included in this review focused on capacity assessment and patient understanding. Decision-making capacity, 1 of the principle pillars of valid informed consent, has 4 essential domains: understanding relevant information, appreciating and applying the information to one’s personal needs and circumstances, rational reasoning, and communicating a clear and consistent choice.30 Even though the MMSE and MacCAT for Clinical Research were the most studied capacity assessment tools, investigators in few studies reported using them in everyday practice. The tools were time-consuming to use and insufficient to determine the degree to which patients possess the capacity to provide valid consent.93 Investigators also have reported that agreement between methodology and use is poor.57 Overall, the practicality, efficiency, acceptability, affordability, and sustainability of capacity assessment tools in dentistry remain unexplored.

In addition to the lack of proper assessment tools, patient passivity and questionable, inconsistent capacity further complicate capacity assessment in the geriatric population.4 Cognitive impairments such as dementia, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and brain damage and medical conditions such as chronic comorbidities, terminal illness, aphasia, and visual and hearing impairments were some of the factors known to interfere with a patient’s ability to provide consent.37,43,81 The potential for declining capacity is another important issue in geriatric dental care and research. Investigators recommended initiatives such as advance care planning, shared decision making, and advance directives to address susceptibility to declining capacity.13,24,39 Van and colleagues81 discussed decision-making capacity, capacity assessment, and declining capacity in a dental care setting and recommended a medical referral for capacity evaluation if the dentist was unsure of the patient’s ability to consent to treatment. Assessing a patient’s ability to provide consent can be challenging for dentists under a variety of circumstances, including when capacity is affected by mental health status or is transient. The extent to which dental practitioners should become involved in legally declaring the patient capable or incapable or in seeking medicolegal counsel is still inconclusive.

Patients’ preferences and values have emerged as important considerations in the consenting process. Investigators identified communicating knowledge and proper understanding of the treatment or research procedures as factors essential to patient autonomy.40 In patients with mild cognitive impairment, investigators recommended geriatric assent, which entails engaging the patient in decision making to the maximum extent possible, to preserve patient autonomy.23,24,55 Pope and Sellers65 suggested obtaining geriatric assent in addition to following advance directives, living wills, and the decisions of surrogates. Although surrogates and proxy decision making were some of the most discussed issues in medical care and research involving the geriatric population, investigators in few articles discussed how and when to seek legal counsel.23,59,86 We did not find any literature specific to dental decision making by surrogates or using advance directives.

Patient autonomy should be preserved to the greatest extent possible. However, little attention has been paid to how to preserve autonomy within dentistry specifically. Investigators in only 2 articles addressed autonomy in the dental care setting, and investigators in 1 article addressed autonomy in dental research. Taiwo and Kass78 reported that oral health research participants in Nigeria had a poor understanding of the consent process. Most participants were unaware of the purpose or duration of the trial and the concept of patient or participant autonomy. Similar to findings about dental care among adults regardless of age, results of a 2015 survey administered to 52 patients in the United Kingdom indicated that most patients remained unaware that the consent process was intended to promote their autonomy and interests.94

Given that our review uncovered a limited number of articles in which the investigators discussed consent issues in geriatric dentistry, comparing geriatric consent issues between dentistry and medicine is difficult. Of the 3 studies in which the investigators discussed informed consent in geriatric dentistry, investigators in 2 focused on consent in dental care,70,81 and investigators in 1 discussed ethical issues in a dental research setting.78 Assessing the cognitive function of patients in a dental office could be challenging because of lack of appropriate assessment tools and time constraints. As with older patients in medical care settings, older patients in dental care settings more frequently chose to decline additional information about their treatment procedures.70 Rubinos Lopez and colleagues70 suggested that the patient should have 24 hours before any routine dental procedure to process the information provided in the consent form. Quality and quantity of information provided was also important. To ensure that patients have understood the relevant information, dental health care professionals were encouraged to ask questions to assess comprehension.81 Moreover, dental practitioners could pay attention to signs such as visible confusion and inconsistencies in the patient’s behavior, and if the patient’s decision-making capacity appeared questionable, family members or caregivers should be involved in the decision-making process.

There were a number of differences in how the 5 key concepts of informed consent (capacity, information, understanding, voluntariness, and choice) were addressed between the dental and medical articles we reviewed. Contrary to articles we found in the dental literature, articles involving patients with medical conditions generally addressed capacity assessment by comparing the different assessment tools available.13,15,32,38,87 The authors in most of these articles favored the MMSE and MacCAT over others. Investigators discussed concepts related to declining capacity and advance directives more thoroughly in the medical literature20,23,39,42,61,67 than in the dental literature. Investigators identified decision making and preserving patient autonomy as substantial ethical concerns arising in cases of medical emergencies.

Preserving autonomy by means of geriatric assent, advance care planning, surrogates and legal proxies, and shared decision making during medical emergencies were a number of the concepts discussed in the medical literature. Investigators rarely discussed these concepts as important issues affecting patient treatment during a dental emergency. Although investigators in some articles addressed issues arising from a conflict of interest between a patient with a medical or cognitive condition and his or her surrogate or proxy,55,72,74 there were no articles in which the investigators discussed these issues in the geriatric dentistry literature. Overall, in our review we found a paucity of articles discussing the topic of informed consent in geriatric dentistry. A limitation to this review is possible publication bias; however, we addressed this limitation by searching multiple databases and reviewing the bibliographies of key articles to ensure we had a collection of international research on these topics.

CONCLUSIONS

Although health care professionals and researchers recognize the importance of respecting patients’ personal beliefs, values, and preferences, findings from our review suggest that the topic of informed consent in geriatric dentistry rarely is studied or discussed in the literature. Furthermore, available information is insufficient to compare consent issues adequately in dental settings with those in other medical settings. Topic areas that could benefit from additional study and substantially improve knowledge in the field of dentistry include concepts of geriatric assent, shared decision making, and proxy decision making in dental care and research; factors affecting decision making and capacity among geriatric patients and study participants; practicality, acceptability, and affordability of the existing capacity assessment tools for use in dentistry; and appropriate involvement of medicolegal professionals in determining patients’ and participants’ decision-making capacity. Expanding information in these areas could assist dental health care professionals not only in understanding the ethical and legal issues regarding informed consent but also in increasing awareness of concepts that could facilitate active participation among the elderly in dental research and care.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and all authors were paid a salary by the National Institutes of Health.

The authors prepared this manuscript as a result of a call for papers exploring geriatric issues in dentistry by the American Dental Association’s Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations’ National Eldercare Advisory Committee in 2015. The authors acknowledge the committee for their guidance and comments.

ABBREVIATION KEY

- MacCAT

MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data related to this article can be found at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2016.11.019.

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Contributor Information

Dr. Amrita Mukherjee, Office of Science Policy and Analysis, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Ms. Alicia A. Livinski, National Institutes of Health Library, Office of Research Services, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Dr. Joseph Millum, Clinical Center Department of Bioethics and Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Dr. Steffany Chamut, Office of Science Policy and Analysis, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Dr. Shahdokht Boroumand, Office of Science Policy and Analysis, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Dr. Timothy J. Iafolla, Office of Science Policy and Analysis, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Dr. Margo R. Adesanya, Office of Science Policy and Analysis, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Dr. Bruce A. Dye, Office of Science Policy and Analysis, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, 31 Center Dr., Suite 5B55, Bethesda, MD.

References

- 1.Wendler D. Can we ensure that all research subjects give valid consent? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2201–2204. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent in cancer clinical trials: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358(9295):1772–1777. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Office of Biotechnology Activities, Office of Science Policy, National Institutes of Health. Informed Consent Guidance for Human Gene Transfer Trials Subject to the NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2014. Available at: http://osp.od.nih.gov/sites/default/files/resources/IC2013.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odom J, Odom S, Jolly D. Informed consent and the geriatric dental patient. Spec Care Dentist. 1992;12(5):202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1992.tb00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey BL. Informed consent in dentistry. JADA. 1985;110(5):709–713. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1985.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wetle T. Ethical issues in geriatric dentistry. Gerodontology. 1987;6(2):73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1987.tb00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beauchamp T. Informed Consent. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan HH. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz J. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capron AM. The real problem is consent for treatment, not consent for research. Am J Bioeth. 2013;13(12):27–29. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.856150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brondani MA, Rossoff LP. The “hot seat” experience: a multifaceted approach to the teaching of ethics in a dental curriculum. J Dent Educ. 2010;74(11):1220–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamis D, Martin FC, Treloar A, Macdonald AJ. Capacity, consent, and selection bias in a study of delirium. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(3):137–143. doi: 10.1136/jme.2002.000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexa O, Veliceasa B, Malancea R, Alexa ID. Postoperative cognitive disorder has to be included within informed consent of elderly patients undergoing total hip replacement. Revista Romana De Bioetica. 2013;11(4):38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arias JJ. A time to step in: legal mechanisms for protecting those with declining capacity. Am J Law Med. 2013;39(1):134–159. doi: 10.1177/009885881303900103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basta LL. End-of-life and other ethical issues related to pacemaker and defibrillator use in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2006;15(2):114–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1076-7460.2006.04818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bjorksten KS, Falldin K, Ulfvarson J. Custodian for elderly with memory impairment in Sweden: a study of 260 physicians’ statements to the court. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bravo G, Duguet AM, Dubois MF, Delpierre C, Vellas B. Substitute consent for research involving the elderly: a comparison between Quebec and France. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2008;23(3):239–253. doi: 10.1007/s10823-008-9070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bravo G, Kim SY, Dubois MF, Cohen CA, Wildeman SM, Graham JE. Surrogate consent for dementia research: factors influencing five stakeholder groups from the SCORES study. IRB. 2013;35(4):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks CL. Considering elderly competence when consenting to treatment. Holist Nurs Pract. 2011;25(3):136–139. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e3182157c19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buehrer TW, Rosenthal R, Stierli P, Gurke L. Patients’ views on regional anesthesia for elective unilateral carotid endarterectomy: a prospective cohort study. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29(7):1392–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clayman ML, Roter D, Wissow LS, Bandeen-Roche K. Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1583–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coverdale J, McCullough LB, Molinari V, Workman R. Ethically justified clinical strategies for promoting geriatric assent. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(2):151–157. doi: 10.1002/gps.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies K, Collerton JC, Jagger C, et al. Engaging the oldest old in research: lessons from the Newcastle 85+ study. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demarquay G, Derex L, Nighoghossian N, et al. Ethical issues of informed consent in acute stroke: analysis of the modalities of consent in 56 patients enrolled in urgent therapeutic trials. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19(2):65–68. doi: 10.1159/000083250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Vries R, Ryan KA, Stanczyk A, et al. Public’s approach to surrogate consent for dementia research: cautious pragmatism. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diener L, Hugonot-Diener L, Alvino S, et al. European Forum for Good Clinical Practice Geriatric Medicine Working Party Guidance synthesis: medical research for and with older people in Europe—proposed ethical guidance for good clinical practice: ethical considerations. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(7):625–627. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dreyer A, Forde R, Nortvedt P. Autonomy at the end of life: life-prolonging treatment in nursing homes—relatives’ role in the decision-making process. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(11):672–677. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.030668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn LB, Palmer BW, Keehan M, Jeste DV, Appelbaum PS. Assessment of therapeutic misconception in older schizophrenia patients with a brief instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):500–506. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn LB, Misra S. Research ethics issues in geriatric psychiatry. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32(2):395–411. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiazOrdaz K, Slowther AM, Potter R, Eldridge S. Consent processes in cluster-randomised trials in residential facilities for older adults: a systematic review of reporting practices and proposed guidelines. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003057. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duron E, Boulay M, Vidal JS, et al. Capacity to consent to biomedical research’s evaluation among older cognitively impaired patients: a study to validate the University of California Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent questionnaire in French among older cognitively impaired patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(4):385–389. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faes M, Van Iersel M, Rikkert MO. Methodological issues in geriatric research. J Nutr Health Aging. 2007;11(3):254–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flaherty ML, Karlawish J, Khoury JC, Kleindorfer D, Woo D, Broderick JP. How important is surrogate consent for stroke research? Neurology. 2008;71(20):1566–1571. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316196.63704.f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ford ME, Kallen M, Richardson P, et al. Effect of social support on informed consent in older adults with Parkinson disease and their caregivers. J Med Ethics. 2008;34(1):41–47. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.018192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fritsch J, Petronio S, Helft PR, Torke AM. Making decisions for hospitalized older adults: ethical factors considered by family surrogates. J Clin Ethics. 2013;24(2):125–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giampieri M. Communication and informed consent in elderly people. Minerva Anestesiol. 2012;78(2):236–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haberstroh J, Muller T, Knebel M, Kaspar R, Oswald F, Pantel J. Can the mini-mental state examination predict capacity to consent to treatment? GeroPsych. 2014;27(4):151–159. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, et al. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(9):778–787. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoover-Regan M, Becker T, Williams MJ, Shenker Y. Informed consent and research subject understanding of clinical trials. WMJ. 2013;112(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hon YK, Narayanan P, Goh PP. Extended discussion of information for informed consent for participation in clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD009835. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ilgili O, Arda B, Munir K. Ethics in geriatric medicine research. Turk Geriatri Derg. 2014;17(2):188–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivashkov Y, Van Norman GA. Informed consent and the ethical management of the older patient. Anesthesiology Clin. 2009;27(3):569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jefferson AL, Lambe S, Moser DJ, Byerly LK, Ozonoff A, Karlawish JH. Decisional capacity for research participation in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1236–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeste DV, Dolder CR, Nayak GV, Salzman C. Atypical antipsychotics in elderly patients with dementia or schizophrenia: review of recent literature. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13(6):340–351. doi: 10.1080/10673220500433247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karlawish J, Rubright J, Casarett D, Cary M, Ten Have T, Sankar P. Older adults’ attitudes toward enrollment of non-competent subjects participating in Alzheimer’s research. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):182–188. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim SY, Kim HM, McCallum C, Tariot PN. What do people at risk for Alzheimer disease think about surrogate consent for research? Neurology. 2005;65(9):1395–1401. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183144.61428.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korfage IJ, Fuhrel-Forbis A, Ubel PA, et al. Informed choice about breast cancer prevention: randomized controlled trial of an online decision aid intervention. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(5):R74. doi: 10.1186/bcr3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lansimies-Antikainen H, Pietila AM, Laitinen T, Kiviniemi V, Rauramaa R. Is informed consent related to success in exercise and diet intervention as evaluated at 12 months? DR’s EXTRA study. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lansimies-Antikainen H, Pietila AM, Kiviniemi V, Rauramaa R, Laitinen T. Evaluation of participant comprehension of information received in an exercise and diet intervention trial: the DR’s EXTRA study. Gerontology. 2010;56(3):291–297. doi: 10.1159/000254484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lansimies-Antikainen H, Laitinen T, Rauramaa R, Pietila AM. Evaluation of informed consent in health research: a questionnaire survey. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(1):56–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Legare F, Briere N, Stacey D, et al. Improving Decision making On Location of Care with the frail Elderly and their caregivers (the DOLCE study): study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:50. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0567-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lui VW, Lam LC, Luk DN, et al. Capacity to make treatment decisions in Chinese older persons with very mild dementia and mild Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(5):428–436. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819d3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mendyk AM, Labreuche J, Henon H, et al. Which factors influence the resort to surrogate consent in stroke trials, and what are the patient outcomes in this context? BMC Medl Ethics. 2015;16:26. doi: 10.1186/s12910-015-0018-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molinari V, McCullough LB, Coverdale JH, Workman R. Principles and practice of geriatric assent. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(1):48–54. doi: 10.1080/13607860500307829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moodley K, Pather M, Myer L. Informed consent and participant perceptions of influenza vaccine trials in South Africa. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(12):727–732. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.009910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moye J, Marson DC. Assessment of decision-making capacity in older adults: an emerging area of practice and research. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(1):3–11. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murray-Brown F, Davies L. A morbid reason for consent. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(3):303–305. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niewald A, Broxterman J, Rosell T, Rigler S. Documented consent process for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and implications for end-of-life care in older adults. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(2):94–97. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-100613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Offerman SR, Nishijima DK, Ballard DW, Chetipally UK, Vinson DR, Holmes JF. The use of delayed telephone informed consent for observational emergency medicine research is ethical and effective. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(4):403–407. doi: 10.1111/acem.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paillaud E, Ferrand E, Lejonc JL, Henry O, Bouillanne O, Montagne O. Medical information and surrogate designation: results of a prospective study in elderly hospitalised patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(3):274–279. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palmer BW, Jeste DV. Relationship of individual cognitive abilities to specific components of decisional capacity among middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(1):98–106. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perez-Carceles MD, Lorenzo MD, Luna A, Osuna E. Elderly patients also have rights. Journal of medical ethics. 2007;33(12):712–716. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.018598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Plawecki LH, Amrhein DW. When “no” means no: elderly patients’ right to refuse treatment. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(8):16–18. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20090706-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pope TM, Sellers T. Legal briefing: the unbefriended—making healthcare decisions for patients without surrogates (Part 2) J Clin Ethics. 2012;23(2):177–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini AL, Pretzer-Aboff I, et al. Reliability and validity of the evaluation to sign consent measure. Gerontologist. 2007;47(1):69–77. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ries NM. Ethics, health research, and Canada’s aging population. Can J Aging. 2010;29(4):577–580. doi: 10.1017/s0714980810000565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosin AJ, van Dijk Y. Subtle ethical dilemmas in geriatric management and clinical research. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(6):355–359. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.008532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosique I, Perez-Carceles MD, Romero-Martin M, Osuna E, Luna A. The use and usefulness of information for patients undergoing anaesthesia. Med Law. 2006;25(4):715–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rubinos Lopez E, Rodriguez Vazquez LM, Varela Centelles A, et al. Impact of the systematic use of the informed consent form at public dental care units in Galicia (Spain) Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13(6):E380–E384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmidt RJ. Informing our elders about dialysis: is an age-attuned approach warranted? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(1):185–191. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10401011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seppet E, Paasuke M, Conte M, Capri M, Franceschi C. Ethical aspects of aging research. Biogerontology. 2011;12(6):491–502. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sepucha KR, Fagerlin A, Couper MP, Levin CA, Singer E, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. How does feeling informed relate to being informed? The DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(5 suppl):77s–84s. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10379647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shah SGS, Farrow A, Robinson I. The representation of healthcare end users’ perspectives by surrogates in healthcare decisions: a literature review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23(4):809–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shin C, Park MH, Han CS, et al. Attitudes on clinical research participation of community living elders in Korea. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2012;4(3):168–173. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Williams BA, Barnes DE, Lindquist K, Schillinger D. Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):867–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suhonen R, Stolt M, Launis V, Leino-Kilpi H. Research on ethics in nursing care for older people: a literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2010;17(3):337–352. doi: 10.1177/0969733010361445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taiwo OO, Kass N. Post-consent assessment of dental subjects’ understanding of informed consent in oral health research in Nigeria. BMC Med Ethics. 2009;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thakkar SC, Frassica FJ, Mears SC. Accuracy, legibility, and content of consent forms for hip fracture repair in a teaching hospital. J Patient Saf. 2010;6(3):153–157. doi: 10.1097/pts.0b013e3181ed765c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Terranova C, Cardin F, Pietra LD, Zen M, Bruttocao A, Militello C. Ethical and medico-legal implications of capacity of patients in geriatric surgery. Med Sci Law. 2013;53(3):166–171. doi: 10.1177/0025802412473963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Van TT, Chiodo LK, Paunovich ED. Informed consent and the cognitively impaired geriatric dental patient. Tex Dent J. 2009;126(7):582–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Rookhuijzen AE, Touwen DP, de Ruijter W, Engberts DP, van der Mast RC. Deliberating clinical research with cognitively impaired older people and their relatives: an ethical add-on study to the protocol “Effects of Temporary Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in the Elderly (DANTE) with Cognitive Impairment”. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(11):1233–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Veelo DP, Spronk PE, Kuiper MA, Korevaar JC, van der Voort PH, Schultz MJ. A change in the Dutch directive on medical research involving human subjects strongly increases the number of eligible intensive care patients: an observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(11):1845–1850. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vellinga A, Smit JH, Van Leeuwen E, Van Tilburg W, Jonker C. Decision-making capacity of elderly patients assessed through the vignette method: imagination or reality? Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(1):40–48. doi: 10.1080/13607860512331334059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Verweij MF, van den Hoven MA. Influenza vaccination in Dutch nursing homes: is tacit consent morally justified? Med Health Care Philos. 2005;8(1):89–95. doi: 10.1007/s11019-004-0837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wechsler LR, Zaidi S. Practice issues in neurology. Continuum Lifelong Learn Neurol. 2008;14(6):141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Whelan PJ, Oleszek J, Macdonald A, Gaughran F. The utility of the Mini-Mental State Examination in guiding assessment of capacity to consent to research. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(2):338–344. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Whelan PJ, Walwyn R, Gaughran F, Macdonald A. Impact of the demand for ‘proxy assent’ on recruitment to a randomised controlled trial of vaccination testing in care homes. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(1):36–40. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Williams B, Irvine L, McGinnis AR, McMurdo ME, Crombie IK. When “no” might not quite mean “no”: the importance of informed and meaningful non-consent—results from a survey of individuals refusing participation in a health-related research project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:59. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wollinger C, Hirnschall N, Findl O. Computer-based tutorial to enhance the quality and efficiency of the informed-consent process for cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(4):655–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wrobel P, Dehlinger-Kremer M, Klingmann I. Ethical challenges in clinical research at both ends of life. Drug Inf J. 2011;45(1):89–105. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wynne JH, Lunney J, Ives D, et al. Perceptions of very old adults about informed care in medical encounters. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):612–614. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dunn LB, Nowrangi MA, Palmer BW, Jeste DV, Saks ER. Assessing decisional capacity for clinical research or treatment: a review of instruments. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1323–1334. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hajivassiliou EC, Hajivassiliou CA. Informed consent in primary dental care: patients’ understanding and satisfaction with the consent process. Br Dent J. 2015;219(5):221–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]