Abstract

Personal care product use is a well-established pathway of exposure for notable endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs), including phthalates, parabens, triclosan, benzophenone-3 (BP3), and bisphenol-A. We utilized questionnaire data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2012 cycles to examine associations between use of sunscreen and mouthwash and urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites and phenols in a nationally representative population of US adults (n=3,529). Compared to individuals who reported “Never” using mouthwash, individuals who reported daily use had significantly elevated urinary concentrations of mono-ethyl phthalate, methyl and propyl parabens, and BP3 (28, 30, 39, and 42% higher, respectively). Individuals who reported “Always” using sunscreen had significantly higher urinary concentrations of triclosan, methyl, ethyl, and propyl parabens, and BP3 (59, 92, 102, 151, and 510% higher, respectively) compared to “Never” users of sunscreen. Associations between exposure biomarkers and sunscreen use were stronger in women compared to men, and associations with mouthwash use were generally stronger in men compared to women. These results suggest sunscreen and mouthwash may be important exposure sources for EDCs.

Keywords: Personal care products, Exposure assessment, Human biomonitoring

INTRODUCTION

Chemicals used in personal care products are of concern to environmental health researchers and the public because of potential for widespread exposure, and because their inclusion in these products is largely unregulated. Some of these chemicals include phthalate diesters and phenols, such as benzophenone-3 (BP3), triclosan, and parabens—including methyl paraben (MP), ethyl paraben (EP), propyl paraben (PP), and butyl paraben (BP)—and, in some instances, bisphenol-A (BPA). Toxicology studies indicate that a number of these compounds may have endocrine disrupting properties or other physiologic consequences that could result in systemic effects in humans.1–7 Furthermore, exposure to these chemicals has been linked to a number of adverse health endpoints including chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes, and hypertension as reproductive outcomes like subfertility and endometriosis.8–12

Personal care product use is a well-established pathway of exposure to both phthalates and phenols. Phthalates are found in cosmetics, lotions, perfumes, deodorants, and nail polish. Individuals who use these products have significantly higher urinary concentrations of some phthalate metabolites, particularly the low molecular weight phthalates mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP), mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP), and mono-isobutyl phthalate (MiBP).13–15 Phenols are found in some of these products as well, particularly lotions, cleansers, cosmetics, soaps, and sunscreen.15 Some studies too have reported higher urinary concentrations in association with product use.16, 17 Exposure to these compounds through oral hygiene product and sunscreen use is studied less commonly, with the exception of BP3 which is a widely known UV filter.17–19 However, triclosan and parabens are utilized in a number of sunscreens and mouthwashes for their antimicrobial properties.20, 21 Additionally, phthalates may be used in these products as a vehicle for fragrances. While the capacity for absorption and/or ingestion of these compounds is established, very few studies have explored mouthwash and sunscreen specifically as exposure sources.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is commonly and effectively utilized to examine distributions of these chemicals in a nationally representative sample, as well as cross-sectional associations with adverse health outcomes or biomarkers of intermediate effects. While none of the study’s many questionnaires are specifically designed to assess product use, in the present analysis we identified two that assess use of mouthwash or sunscreen in a large subset of study participants from 2009–2012. In the present analysis we examine associations between urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites and phenols typically found in personal care products in association with self-reported use of these products. Furthermore, as personal care product use differs dramatically by gender, we explore differences in associations in males compared to females.

METHODS

Study population

NHANES is an ongoing cross-sectional study conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics that collects data every two years on demographic, anthropometric, dietary, and biologic characteristics in a nationally representative sample. Recruitment, specific features of study design, and the array of measures collected and biomarkers measured in collected specimens are described in detail on the NHANES website: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. For the present analysis we combined NHANES data from the 2009–2010 and 2011–2012 cycles.

Exposure biomarker measurement

Urine samples were collected in a subset of participants at a mobile examination center, frozen at −20 degrees C, and shipped on dry ice to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Personal Care Products Laboratory for analysis.22, 23 A panel of phthalate metabolites and environmental phenols were measured using high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) and on-line solid phase extraction (SPE) coupled to HPLC-isotope dilution MS/MS, respectively, by previously published protocols.22, 23 For phthalate analysis, urine samples first underwent enzymatic deconjugation from glucuronidated forms so that measured concentrations represent total urinary concentrations. For the present analysis we examined phthalate metabolites and environmental phenols that are commonly used in personal care products, including mono-benzyl phthalate (MBzP), MBP, MiBP, MEP, triclosan, BPA, MP, EP, PP, BP, and BP3. Levels below limit of detection (LOD) were replaced with the LOD divided by the square root of 2. Urinary creatinine concentrations, indicative of urine dilution, were assessed using an enzymatic reaction and measurement with a Hitachi Modular P Chemistry Analyzer.24

Product use data from questionnaires

As part of the NHANES study a variety of questionnaires are administered during home visits, prior to physical examination. We examined each questionnaire from the 2009–2010 cycle to identify questions related to personal care product use, and identified two surveys that contained questions reflective of individual-level mouthwash and sunscreen use. Mouthwash use was estimated from the Oral Health questionnaire. The variable used was a response to the question “Aside from brushing your teeth with a toothbrush, in the last seven days, how many days did you use mouthwash or other dental rinse product that you use to treat dental disease or dental problems?”25 This question was administered to participants ages 30+ for both 2009–2010 and 2011–2012 cycles. Responses were coded as a continuous variable (0 to 7 days). Participants who refused to answer this question or reported that they did not know were recoded as missing data. For the purposes of this analysis, responses were recoded as follows: “Always” (reported use 7 out of the last 7 days); “Sometimes” (reported use 1–6 out of the last 7 days); or “Never” (reported use 0 out of the last 7 days).

Sunscreen use was estimated from the Dermatology questionnaire, which was administered to a subset of participants ages 20–59 in both survey cycles. The variable used was a response to the question “Use sunscreen?” Responses were coded as a numeric variable (1–5) with numbers corresponding to the following responses: 1) Always; 2) Most of the time; 3) Sometimes; 4) Rarely; and 5) Never.26 We recoded responses as follows: “Always” (reported use Always); “Sometimes” (reported use Most of the time, Sometimes, or Rarely); and “Never” (reported use Never).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R version 3.1.027 and were adjusted for the complex NHANES survey design using appropriate weights created based on the smallest subsample examined, which in this case was the participants with urine samples analyzed for urinary phthalate metabolite and phenol concentrations.28 These analyses were performed using the R package ‘survey’ (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survey/survey.pdf). First we examined distributions of continuous covariates, including age, body mass index (BMI), and poverty income ratio (PIR) in the total population and by mouthwash and sunscreen use categories by calculating percentiles. Differences in continuous covariates by category were tested using generalized linear models. We also examined distributions of categorical covariates by looking at raw sample sizes and weighted proportions in the total population and within each product use category. Next we examined distributions of exposure variables by survey year, presenting unweighted number of samples below the limit of detection as well as weighted percentiles.

We examined the relationship between mouthwash or sunscreen use and urinary phthalate or phenol concentrations with linear regression models. Product use variables were modeled as categorical independent variables and continuous natural log-transformed exposure biomarkers were modeled as dependent variables. In secondary models mouthwash and sunscreen use variables were modeled continuously to test for significance of trends in exposure biomarker levels in association with increasing product use. Models were adjusted for covariates selected a priori based on known associations with urinary exposure biomarker concentrations. These adjustments were expected to improve model precision and to account for confounding by associations between covariates and product use. Fully adjusted models included natural log-transformed urinary creatinine (continuous), age (continuous), gender (categorical), race/ethnicity (categorical), PIR (an indicator of socioeconomic status; continuous), BMI (continuous), and survey year (categorical). Season at the time of questionnaire was reported only by 6-month period and thus was not included as a covariate in the analysis. Models adjusted for urinary creatinine only were examined for comparison purposes. Effect estimates from models and standard errors were transformed into percent change [%Δ] in exposure biomarker in association with the category of product use, with 95% confidence intervals [CI], for interpretability.

Because few studies previously have examined relationships for personal care product use in men, we additionally examined effect modification of these relationships by gender. We re-created the models above with the addition of an interaction term between gender and each product use variable, and created stratified models for men and women separately to quantify effect estimates within each gender.

RESULTS

From 2009–2012 there were 3,529 NHANES participants who had measurements for urinary phthalate metabolites and phenols and who responded to either the sunscreen or mouthwash use questions. For the mouthwash variable, the distribution of use was as follows: “Always” use (n=973, 34.3%); “Sometimes” use (n=654, 23.1%); and “Never” use (n=1,209, 42.6%). For the sunscreen variable, the distributions were: “Always” use (n=296, 12.1%); “Sometimes” use (n=1,051, 42.9%); “Never” use (n=1,101, 45.0%). Distributions of continuous and categorical covariates in subsets of the populations with mouthwash and sunscreen use questionnaire data available are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Notably, PIR was significantly lower, indicating lower socioeconomic status, in participants who reported “Always” using mouthwash compared to those who reported “Never” using mouthwash. Also, PIR was significantly lower in participants who reported “Never” using sunscreen compared to those who reported using sunscreen “Sometimes” or “Always.”

Table 1.

Median (range) of continuous covariates and N (weighted percent) of categorical covariates overall and by mouthwash use categories in NHANES 2009–2012.

| Mouthwash use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Overall | Never | Sometimes | Always | |

| N | 2836 (100) | 1209 (46.3) | 654 (25.0) | 973 (28.7) |

| Age | 51 (30, 80) | 50 (30, 80) | 51 (30, 80) | 51 (30, 80) |

| BMI | 27.8 (16.0, 84.9) | 27.5 (17.1, 67.3) | 27.3 (16.0, 84.9) | 28.4 (16.6, 69.0) |

| PIR | 3.23 (0, 5) | 3.23 (0, 5) | 3.52 (0, 5) | 2.63 (0, 5)* |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1459 (48.2) | 619 (44.8) | 360 (26.5) | 480 (28.7) |

| Female | 1377 (51.8) | 590 (47.8) | 294 (23.5) | 493 (28.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Mexican American | 369 (6.98) | 149 (39.6) | 92 (25.2) | 128 (35.3) |

| Other Hispanic | 282 (5.74) | 102 (36.3) | 59 (22.9) | 121 (40.8) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1264 (70.0) | 646 (50.3) | 296 (25.9) | 322 (23.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 610 (10.9) | 158 (27.9) | 135 (22.2) | 317 (49.9) |

| Other/Multi-racial | 311 (6.41) | 154 (50.4) | 72 (21.4) | 85 (28.3) |

| Survey year | ||||

| 2009–2010 | 1457 (48.4) | 650 (47.9) | 331 (23.8) | 476 (28.3) |

| 2011–2012 | 1379 (51.6) | 559 (44.9) | 323 (26.1) | 497 (29.0) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PIR, poverty income ratio.

Significant difference in continuous covariate in product use category compared to reference (“Never”).

Table 2.

Median (range) of continuous covariates and N (weighted percent) of categorical covariates overall and by sunscreen use categories in NHANES 2009–2012.

| Sunscreen use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Overall | Never | Sometimes | Always | |

| N | 2448 (100) | 1101 (34.8) | 1051 (51.1) | 296 (14.1) |

| Age | 40 (20, 59) | 41 (20, 59) | 39 (20, 59) | 42 (20, 59) |

| BMI | 27.3 (15.6, 84.9) | 28.4 (16.4, 84.9) | 27.0 (15.6, 61.8)* | 26.3 (16.0, 47.7)* |

| PIR | 2.91 (0, 5) | 1.74 (0, 5) | 3.58 (0, 5)* | 3.75 (0, 5)* |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1238 (49.3) | 685 (43.1) | 484 (50.0) | 69 (6.84) |

| Female | 1210 (50.7) | 416 (26.7) | 567 (52.0) | 227 (21.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Mexican American | 349 (8.92) | 196 (54.0) | 115 (34.8) | 38 (11.2) |

| Other Hispanic | 249 (6.95) | 111 (44.1) | 94 (37.8) | 44 (18.1) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1001 (63.9) | 278 (23.6) | 582 (60.8) | 141 (15.6) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 527 (12.2) | 388 (72.7) | 112 (21.8) | 27 (5.51) |

| Other/Multi-racial | 322 (8.01) | 128 (37.2) | 148 (47.4) | 46 (15.4) |

| Survey year | ||||

| 2009–2010 | 1301 (50.3) | 598 (36.6) | 545 (48.9) | 158 (14.5) |

| 2011–2012 | 1147 (49.7) | 503 (33.0) | 506 (53.2) | 138 (13.8) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PIR, poverty income ratio.

Significant difference in continuous covariate in product use category compared to reference (“Never”).

Table 3 shows urinary phthalate metabolite and phenol distributions in the study population by survey year. Generally, urinary concentrations were lower in participants from the 2010–2011 cycle compared to those from the 2009–2010 cycle, with the exception of BP3 which was slightly higher. In some instances the differences were striking, as for MEP (47% reduction in median urinary concentrations in the 2011–2012 vs. 2009–2010). This is consistent with trends observed previously for phthalates.29

Table 3.

Urinary phthalate metabolite and phenol distributions (in μg/L) by NHANES survey cycle (weighted).

| 2009–2010 (n=1830) | 2011–2012 (n=1699) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Phthalate | N (%) < LOD | Median (25th, 75th percentiles) | N (%) < LOD | Median (25th, 75th percentiles) |

| MBP | 10 (0.55) | 14.4 (6.71, 27.9) | 112 (6.59) | 8.20 (3.30, 18.2) |

| MiBP | 5 (0.27) | 7.56 (3.58, 14.5) | 20 (1.18) | 5.90 (2.90, 12.2) |

| MBzP | 11 (0.60) | 5.92 (2.58, 12.5) | 42 (2.47) | 4.00 (1.80, 9.60) |

| MEP | 0 (0) | 60.5 (23.2, 184) | 2 (0.12) | 32.0 (13.9, 105) |

|

| ||||

| Phenol | ||||

|

| ||||

| BP3 | 42 (2.30) | 16.8 (4.50, 88.4) | 44 (2.59) | 19.1 (4.70, 82.2) |

| Triclosan | 410 (22.4) | 11.5 (3.18, 63.3) | 492 (29.0) | 7.52 (1.63, 57.6) |

| BPA | 158 (8.63) | 1.80 (0.90, 3.50) | 195 (11.5) | 1.40 (0.70, 2.90) |

| Methyl PB | 8 (0.44) | 59.2 (16.1, 241) | 11 (0.65) | 48.8 (10.8, 188) |

| Ethyl PB | 848 (46.3) | 1.30 (0.71, 8.70) | 873 (51.4) | 0.71 (0.71, 7.10) |

| Propyl PB | 129 (7.05) | 7.70 (1.20, 49.9) | 106 (6.24) | 6.20 (1.00, 35.5) |

| Butyl PB | 1131 (61.7) | 0.14 (0.14, 0.80) | 1223 (72.0) | 0.14 (0.14, 0.40) |

Abbreviations: LOD, limit of detection; PB, paraben.

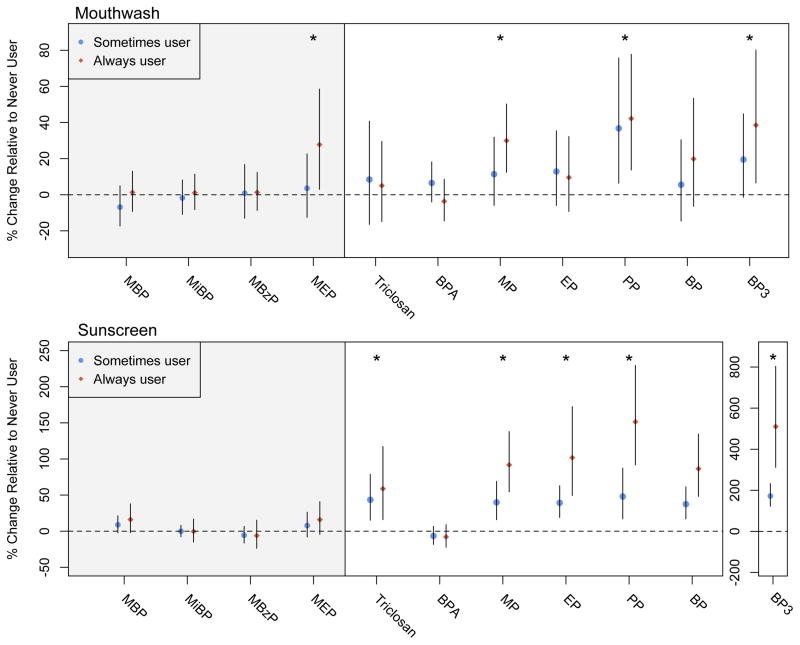

Percent change and 95% CI for urinary concentrations of exposure biomarkers for “Sometimes” or “Always” users of mouthwash or sunscreen, compared to “Never” users, are presented in Figure 1. Adjusted models of mouthwash use (n=2,522) showed that individuals who “Always” used mouthwash or dental rinse had significantly higher urinary concentrations of MEP (%Δ=27.8, 95% CI=2.98, 58.5), BP3 (%Δ=38.5, 95% CI=6.54, 80.2), MP (%Δ=30.0, 95% CI=12.4, 50.2), and PP (%Δ=42.2, 95% CI=13.7, 77.8) compared to individuals who “Never” used mouthwash. Trends in levels were significant across categories for each of these compounds (p<0.05), although only PP concentrations were significantly higher in “Sometimes” compared to “Never” users of mouthwash (%Δ=36.8, 95% CI=6.41, 75.7).

Figure 1.

Adjusteda percent change and 95% confidence intervals in urinary phthalate metabolite or phenol concentrations in participants reporting “Sometimes” or “Always” use of mouthwash or sunscreen compared to participants reporting “Never” use in NHANES 2009–2012.

*Denotes significant (p<0.05) trend for exposure biomarkers across product use categories.

aModels adjusted for urinary creatinine concentration, age, poverty income ratio, race/ethnicity, body mass index, and survey cycle.

Adjusted models of sunscreen use (n=2,225) showed that participants who “Always” used sunscreen had strikingly higher urinary concentrations of BP3 (%Δ=509.8, 95% CI=311.7, 803.2) compared to participants who “Never” use sunscreen (Figure 1). “Sometimes” users also had significantly higher levels compared to “Never” users (%Δ=172.1, 95% CI=122.8, 232.3), and the trend across categories was significant (p<0.001). Additionally, triclosan concentrations were significantly higher in participants who reported “Always” (%=58.7, 95%CI=16.0, 117.2) or “Sometimes” (%Δ=43.5, 95% CI=15.2, 78.7) using sunscreen (p trend=0.002). All of the parabens examined were significantly elevated in urine from “Always” and “Sometimes” users compared to “Never” users as well (ps for trend <0.01). No significant associations were observed between urinary phthalate metabolites and sunscreen use categories. Models adjusted for urinary creatinine only had slightly larger effect estimates but were generally similar to fully adjusted results (Supplementary Table S1).

When we examined associations stratified by participant gender, some distinct patterns emerged (Table 4). For mouthwash use, we observed generally that associations “Sometimes” or “Always” use of mouthwash and urinary exposure biomarkers were elevated in men compared to women. This was particularly true for MP, PP, and BP associations with “Always” use. Interaction terms between “Always” use and gender, however, did not attain statistical significance. For sunscreen use, we observed greater effect estimates for the associations between “Sometimes” or “Always” use of sunscreen and all exposure biomarkers in women compared to men, and interaction terms were statistically significant between “Always” use and gender for MEP and BP. No interactions were observed for MBP, MiBP, MBzP or BPA for either mouthwash or sunscreen use, and effect estimates were null in both men and women (data not shown).

Table 4.

Adjusteda percent change (95% confidence intervals) in urinary phthalate metabolite or phenol concentrations in participants reporting “Sometimes” or “Always” product use compared to participants reporting “Never” product use in males and females separately from NHANES 2009–2012.

| Men (n=1297) | Women (n=1225) | p (interaction) for Always use by genderb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mouthwash | Sometimes use | Always use | Sometimes use | Always use | |

| MEP | 5.11 (−16.3, 31.9) | 48.3 (10.3, 99.4)* | 2.53 (−17.0, 26.7) | 12.3 (−17.4, 52.8) | 0.19 |

| BP3 | 3.67 (−20.4, 35.1) | 37.0 (5.40, 78.2)* | 33.9 (−0.80, 80.7) | 34.7 (−10.0, 102) | 0.79 |

| Triclosan | −12.6 (−34.8, 17.0) | 19.2 (−13.2, 63.8) | 34.3 (−5.10, 90.0) | −8.88 (−35.5, 28.7) | 0.35 |

| Methyl PB | 3.98 (−20.0, 35.2) | 62.4 (27.9, 106)* | 18.4 (8.40, 29.3)* | 6.08 (−20.2, 40.9) | 0.07 |

| Ethyl PB | −5.35 (−20.7, 12.9) | 12.2 (−11.3, 41.9) | 34.3 (−3.60, 87.1) | 11.2 (−19.2, 53.0) | 0.58 |

| Propyl PB | 35.0 (−11.1, 105) | 79.9 (33.3, 143)* | 36.1 (−6.20, 97.5) | 17.1 (−21.2, 74.0) | 0.07 |

| Butyl PB | 1.41 (−10.2, 14.5) | 32.7 (6.60, 65.3)* | 9.86 (−25.8, 62.6) | 13.0 (−22.6, 64.9) | 0.23 |

|

| |||||

| Men (n=1122) | Women (n=1103) | p (interaction) for Always use by genderb | |||

|

| |||||

| Sunscreen | Sometimes use | Always use | Sometimes use | Always use | |

|

| |||||

| MEP | 7.79 (−11.4, 31.1) | −22.8 (−43.8, 6.00) | 14.2 (−9.90, 44.8) | 39.4 (10.4, 76.0)* | <0.01 |

| BP3 | 144 (76.7, 236)* | 357 (110, 896)* | 209 (125, 324)* | 588 (323, 1019)* | 0.42 |

| Triclosan | 23.9 (−11.1, 72.5) | 35.3 (−32.0, 169) | 75.2 (32.1, 132)* | 78.4 (24.2, 156)* | 0.44 |

| Methyl PB | 27.6 (−1.50, 65.3) | 39.7 (−25.0, 160) | 69.2 (33.2, 115)* | 134 (83.7, 198)* | 0.11 |

| Ethyl PB | 22.1 (3.40, 44.3)* | 97.6 (33.8, 192)* | 76.1 (35.4, 129)* | 119 (40.0, 242)* | 0.28 |

| Propyl PB | 39.5 (−0.60, 95.8) | 65.5 (−13.5, 217) | 84.2 (36.5, 149)* | 219 (132, 340)* | 0.06 |

| Butyl PB | 23.1 (9.90, 37.9)* | 42.3 (2.60, 97.5)* | 67.2 (26.8, 120)* | 131 (66.0, 221)* | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: PB, paraben.

Models adjusted for urinary creatinine concentration, age, poverty income ratio, race/ethnicity, body mass index, and survey cycle.

p values extracted from models with interaction term between product use category and gender and are reported for “Always” use by gender interactions only.

p<0.05 for association.

DISCUSSION

In a nationally representative US sample of 3,529 participants, we observed that self-reported use of sunscreen was associated with higher urinary concentrations of BP3, triclosan, and parabens. Additionally, self-reported mouthwash use was associated with higher urinary concentrations of MEP, BP3, and some parabens. Furthermore, we observed that the associations between sunscreen use and MEP and butyl PB exposure were significantly stronger in women. While this was an observational study and the associations are not necessarily causal, they suggest that sunscreen and mouthwash use are important sources of exposure to these non-persistent compounds.

Triclosan, parabens, and BP3 are FDA designated active ingredients,30 and can be found on labels for some sunscreens and oral hygiene products. Additionally, some studies have performed laboratory testing of personal care products to quantify concentrations of phthalates, phenols, and other chemical compounds. Rudel and colleagues published an extensive study in 2012 measuring 213 personal care products and testing for a panel of compounds of interest, including phthalates and BPA as well as triclosan, parabens, UV filters, and others.15 In sunscreens, they detected a number of phthalate diesters as well as BPA and some parabens, but not triclosan. Mouthwash or other oral hygiene products were not examined in this analysis.

A number of studies have examined biomarkers of these compounds or their metabolites in relation to personal care product use questionnaires with some notable limitations. First, most of these studies have examined pregnant women alone, and to our knowledge only one study—measuring phthalate metabolites only—included male participants.31 A second limitation to this body of literature is that studies seldom quantify oral care product usage.

From the studies examining urinary phthalate metabolites in relation to questions from product use questionnaires, the clearest finding has been for an association between use of fragrances, perfume, or cologne and urinary concentrations of MEP.31–36 Findings for other phthalate metabolites have been less consistent. In regard to sunscreen use, one study of pregnant mothers observed elevated urinary MBP and mono-methyl phthalate (MMP) concentrations in women reporting recent application;36 however two other studies observed no associations with phthalates.36,38–39 Sample sizes for these analyses were small (N=50–177), although two had repeated measures designs. In the present analysis we observed no association between sunscreen use and urinary phthalate metabolites, which is consistent with these generally null findings.

Two studies also examined urinary phthalate metabolites in association with mouthwash use; a study of mothers in Sweden observed lower levels of MBzP in mouthwash users, but no differences for other metabolites,37 and a study of Puerto Rican pregnant women observed no associations with phthalates.38 In our study we observed significantly higher urinary concentrations of MEP in participants who reported “Always” vs. “Never” use of mouthwash. Our ability to detect this association may have been due to the large sample size available for the present analysis, and our inclusion of male participants.

Fewer studies have examined associations between biomarkers of phenol exposure in relation to personal care product use. Specific to sunscreen use, two studies in women examined associations between phenols and self-reported use of sunscreen but did not detect significant associations.17, 35 In our analysis we observed increases in BP3, all parabens measured, and triclosan in participants with recent sunscreen use. While the findings for BP3 are expected,18 the significant increases in urinary paraben and triclosan concentrations in sunscreen users are novel. The application and necessity of these compounds in sunscreens may deserve additional scrutiny.

Only one study examined self-reported mouthwash use in relation to phenol exposure, observing higher urinary concentrations of BPA and BP3 in pregnant mouthwash users, but no significant differences for triclosan or parabens.17 Consistent with that study we observed higher BP3 exposure in NHANES participants reporting “Always” vs. “Never” use of mouthwash, but we did not observe associations with BPA. Also, we did not observe associations with triclosan, even though it is listed as an ingredient in some mouthwashes.20 Our novel findings of elevated MP and EP concentrations in “Always” compared to “Never” mouthwash users suggest that this may be a previously unnoticed but potentially important source of exposure to these compounds in the general US population.

In our sensitivity analyses we observed interesting differences in the associations between exposure biomarkers and mouthwash or sunscreen use in men and women examined separately. For mouthwash, associations were generally stronger between exposure biomarkers and use in men, although interaction terms were not statistically significant. This was particularly true for the parabens MP, PP, and BP as well as BP3. While these findings may be due to chance, they could also suggest that mouthwash use may be a more important route of exposure to these compounds in men compared to women. For sunscreen, associations were consistently stronger in women compared to men. This observation may be explained by greater quantities of sunscreen used in each application by women,39 greater measurement error in estimates for men because of the small sample size in “Always” users, and/or differences in reporting of product use in men compared to women.

A major advantage of this analysis was our ability to assess associations between urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites and phenols and personal care product use questions in a large and nationally representative US sample. This is the largest study of its kind to date and also addresses these associations in adult men. To our knowledge, only one other study has examined the relationship between personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolites in men and none have examined the relationship with phenols. These findings deserve corroboration in a study designed more specifically to address this research question, with particular attention to quantities of the product used.

Our analysis had several limitations, primarily due to the fact that this data was not collected with the specific intent of examining predictors of exposure. In most studies of personal care product use, questionnaires request information on use over the 24–48 hours prior to urine sample collection, because the compounds measured are metabolized and excreted from the human body relatively quickly (half-lives of 6–24 hours). Our “Always” estimates of sunscreen and mouthwash use likely reflect use over the last day; however “Sometimes” users may not have had any use during the relevant window of interest. Nevertheless, “Sometimes” users are more likely than “Never” users to have used mouthwash or sunscreen during this time frame which justifies our use of these data. Also, we did not have information on month of questionnaire and sample collection in this dataset. However, because phthalates and/or phenols are unlikely to be associated with seasonal variation—except through the sunscreen exposure route—it is unlikely that this would bias our analysis. Additionally, our analysis was limited by our ability to examine only these two types of products in our analysis. This leaves the potential for residual confounding from other personal care product use. Finally, although we were able to quantify frequency of use, the questionnaire data did not inform amount of mouthwash or sunscreen applied at each use or brand. Nonetheless, these limitations primarily would have added measurement error to our analysis, and thus would not have differentially biased our results.

In conclusion, we observed significantly higher urinary concentrations of some phthalate metabolites and phenols in individuals who reported using mouthwash or sunscreen in adult men and women from a nationally representative US sample. Specifically, for mouthwash, MEP, MP, PP, and BP3 were significantly higher in urine of participants reporting “Always” vs. “Never” use. These associations were strongest amongst male participants. Also, triclosan, all parabens, and BP3 were significantly higher in urine of participants who reported “Always” using sunscreen compared to participants who “Never” used sunscreen, and these associations were strongest in women. This is the largest study to date to report on use of these personal care products in relation to biomarkers of phthalate and phenol exposure, and among the first to examine associations in men alone. While these findings do not suggest that these products should or should not be utilized, they are important for characterizing exposure sources of these compounds and highlight mouthwash and sunscreen as potentially important sources of exposure in the adult US population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding support was provided by that National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, grant numbers: P42ES017198, R01ES018872, and P30ES017885.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Borch J, Metzdorff SB, Vinggaard AM, Brokken L, Dalgaard M. Mechanisms underlying the anti-androgenic effects of diethylhexyl phthalate in fetal rat testis. Toxicology. 2006;223:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tetz LM, Cheng AA, Korte CS, Giese RW, Wang P, Harris C, et al. Mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate induces oxidative stress responses in human placental cells in vitro. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2013;268:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krause M, Klit A, Blomberg Jensen M, Søeborg T, Frederiksen H, Schlumpf M, et al. Sunscreens: are they beneficial for health? An overview of endocrine disrupting properties of UV-filters. International journal of andrology. 2012;35:424–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dann AB, Hontela A. Triclosan: environmental exposure, toxicity and mechanisms of action. Journal of applied toxicology : JAT. 2011;31:285–311. doi: 10.1002/jat.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darbre PD, Harvey PW. Paraben esters: review of recent studies of endocrine toxicity, absorption, esterase and human exposure, and discussion of potential human health risks. Journal of applied toxicology : JAT. 2008;28:561–578. doi: 10.1002/jat.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koeppe ES, Ferguson KK, Colacino JA, Meeker JD. Relationship between urinary triclosan and paraben concentrations and serum thyroid measures in NHANES 2007–2008. The Science of the total environment. 2013;445–446:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watkins DJ, Ferguson KK, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, Meeker JD. Associations between urinary phenol and paraben concentrations and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. International journal of hygiene and environmental health. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.11.001.. e-pub ahead of print 2014/12/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatch EE, Nelson JW, Stahlhut RW, Webster TF. Association of endocrine disruptors and obesity: perspectives from epidemiological studies. International journal of andrology. 2010;33:324–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang IA, Galloway TS, Scarlett A, Henley WE, Depledge M, Wallace RB, et al. Association of urinary bisphenol A concentration with medical disorders and laboratory abnormalities in adults. Jama. 2008;300:1303–1310. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weuve J, Hauser R, Calafat AM, Missmer SA, Wise LA. Association of exposure to phthalates with endometriosis and uterine leiomyomata: findings from NHANES, 1999–2004. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118:825. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vélez MP, Arbuckle TE, Fraser WD. Female exposure to phenols and phthalates and time to pregnancy: the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) Study. Fertility and sterility. 2015;103:1011–1020. e1012. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meeker JD, Ehrlich S, Toth TL, Wright DL, Calafat AM, Trisini AT, et al. Semen quality and sperm DNA damage in relation to urinary bisphenol A among men from an infertility clinic. Reproductive toxicology. 2010;30:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koniecki D, Wang R, Moody RP, Zhu J. Phthalates in cosmetic and personal care products: concentrations and possible dermal exposure. Environmental research. 2011;111:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parlett LE, Calafat AM, Swan SH. Women’s exposure to phthalates in relation to use of personal care products. Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology. 2013;23:197–206. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG, Rudel RA. Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environmental health perspectives. 2012;120:935–943. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, Smith KW, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology. 2014;24:459–466. doi: 10.1038/jes.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meeker JD, Cantonwine DE, Rivera-González LO, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM, et al. Distribution, variability, and predictors of urinary concentrations of phenols and parabens among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. Environmental science & technology. 2013;47:3439–3447. doi: 10.1021/es400510g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krause M, Klit A, Blomberg Jensen M, Soeborg T, Frederiksen H, Schlumpf M, et al. Sunscreens: are they beneficial for health? An overview of endocrine disrupting properties of UV-filters. Int J Androl. 2012;35:424–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tibbetts J. Shining a Light on BP-3 Exposure: Sunscreen Chemical Measured in US Population. Environmental health perspectives. 2008;116:A306. doi: 10.1289/ehp.116-a306a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Urinary concentrations of triclosan in the U.S. population: 2003–2004. Environmental health perspectives. 2008;116:303–307. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Environmental Working Group. [Accessed 09/22/15];EWG’s Skin Deep Cosmetics Database. Available from: http://www.ewg.org/skindeep/

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) [Accessed 02/05/15];Laboratory Procedure Manual: Environmental Phenol. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_09_10/EPH_F_met_phenols_parabens.pdf.

- 23.NCHS. [Accessed 02/05/15];Laboratory Procedure Manual: Phthalate Metabolites. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_09_10/PHTHTE_F_met.pdf.

- 24.NCHS. [Accessed 02/05/15];Laboratory Procedure Manual: Urinary Creatinine. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/nhanes/nhanes_09_10/ALB_CR_F_met_creatinine.pdf.

- 25.NCHS. [Accessed 02/05/15];Sample Person Questionnaire: Oral Health. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/ohq.pdf.

- 26.NCHS. [Accessed 02/05/15];Sample Person Questionnaire: Dermatology. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/deq.pdf.

- 27.R Core Team. [Accessed 02/05/15];R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available from: http://www.R-project.org.

- 28.NCHS. [Accessed 02/05/15];Continuous NHANES web tutorial: Survey design factors. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/NHANES/SurveyDesign/intro.htm.

- 29.Zota AR, Calafat AM, Woodruff TJ. Temporal trends in phthalate exposures: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2010. Environmental health perspectives. 2014;122:235–241. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 09/22/15];Over-the-Counter (OTC) Related Federal Register Notices, Ingredient References, and other Regulatory Information. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ucm106368.htm.

- 31.Duty SM, Ackerman RM, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use predicts urinary concentrations of some phthalate monoesters. Environmental health perspectives. 2005:1530–1535. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romero-Franco M, Hernández-Ramírez RU, Calafat AM, Cebrián ME, Needham LL, Teitelbaum S, et al. Personal care product use and urinary levels of phthalate metabolites in Mexican women. Environment international. 2011;37:867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Just AC, Adibi JJ, Rundle AG, Calafat AM, Camann DE, Hauser R, et al. Urinary and air phthalate concentrations and self-reported use of personal care products among minority pregnant women in New York city. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology. 2010;20:625–633. doi: 10.1038/jes.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parlett LE, Calafat AM, Swan SH. Women’s exposure to phthalates in relation to use of personal care products. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology. 2013;23:197–206. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, Smith KW, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology. 2014;24:459–466. doi: 10.1038/jes.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buckley JP, Palmieri RT, Matuszewski JM, Herring AH, Baird DD, Hartmann KE, et al. Consumer product exposures associated with urinary phthalate levels in pregnant women. Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology. 2012;22:468–475. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsson K, Ljung Bjorklund K, Palm B, Wennberg M, Kaj L, Lindh CH, et al. Exposure determinants of phthalates, parabens, bisphenol A and triclosan in Swedish mothers and their children. Environ Int. 2014;73:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cantonwine DE, Cordero JF, Rivera-Gonzalez LO, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations among pregnant women in Northern Puerto Rico: distribution, temporal variability, and predictors. Environ Int. 2014;62:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright MW, Wright ST, Wagner RF. Mechanisms of sunscreen failure. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2001;44:781–784. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.113685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.