1. Introduction

Leg length discrepancy (LLD) has been a controversial issue among researchers and clinicians for many years. Its presence obviously is not in doubt, however, there is little consensus as to its many aspects, including the extent of LLD considered to be clinically significant, the prevalence, reliability and validity of the measuring methods, the effect of LLD on function and its role in various neuromusculoskeletal conditions.1 LLD can be caused by structural deformities originating from true bony leg length differences.2, 3, 4 Nevertheless, it can also be due to functional deformity derived from abnormal hip, knee, ankle and foot movements in each of the three planes of motion.2, 3, 5

LLD has been found to be a significant factor influencing several pathological and physiological conditions which affect function and quality of life.6, 7 For example, it has been suggested that LLD has a significant effect on pelvic and lower limb biomechanics, may cause pelvic obliquity in the frontal plane thus leading to functional scoliosis, posture deformation, gait asymmetry and low back pain, as well as gonarthrosis or coxarthrosis and other lower limbs symptoms.4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Moreover, LLD has also been correlated with gait deviations.15 The inconsistency in the literature regarding the effect and role LLD plays in several pathological conditions is due to poor reliability and validity of the measurement methods. In addition, it is impossible to confine the effect of LLD to pathological conditions where several other abnormal findings are also present.

1.1. Definition of LLD

1.1.1. There are basically two definitions of LLD

True leg length discrepancy (TLLD) is defined as the anatomical difference between the lengths of the two limbs between the proximal edge of the femoral head to the distal edge of the tibia which can be congenital or acquired. Congenital conditions include mild developmental abnormalities found at birth or childhood, whereas acquired conditions include trauma, fractures, orthopedic degenerative diseases and surgical disorders such as joint replacement. A systemic review evaluating the prevalence of LLD by radiographic measurements revealed that 90% of the normal population had some type of variance in bony leg length, with 20% exhibiting a difference of >9 mm.16

Functional leg length discrepancy (FLLD) is defined as a condition of asymmetrical leg length, not necessarily a result or compensation of a true bony length difference. FLLD may be caused by an alteration of lower limb mechanics, such as joint contracture, static or dynamic mechanical axis malalignment, muscle weakness or shortening. It is impossible to detect these faulty mechanics using a non-functional evaluation, such as radiography. FLLD can develop due to an abnormal motion of the hip, knee, ankle or foot in any of the three planes of motion.

1.2. Current accepted methods of measuring LLD

1.2.1. Imaging

Various imaging techniques have been used to measure true LLD.17, 18 Radiography is considered the gold standard for measuring LLD, with established techniques including full limb radiographs, scanograms, computerized digital radiographs and computerized tomography (CT). These methods are highly reliable and valid but they are also expensive and expose the subject to radiation, thus impractical to use in the routine clinical setting and not feasible for everyone. However, these measurements do not reveal the influence of dynamic lower limb malalignment on leg length.

1.2.2. Direct clinical method

The direct clinical method measures the distance (using a tape measure) between two anatomical points while lying in a supine position. Some authors 19, 20 have found that direct measurement, by averaging the distance of two tape measurements between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the medial malleolus, have an acceptable validity and reliability when used as a screening tool for assessing LLD compared to a CT. Woerman ± 10.1 between the ASIS to medial malleolus measurement and radiography.21 This is in agreement with another study that found the direct method to be inaccurate, with an estimated measuring error of ±8.6 mm.22 Furthermore, repeated measurements by the same examiner conflicted 12% as to diagnosing the side with the shorter limb, even when radiographic LLD was 25 mm.

1.2.3. Indirect clinical method

The indirect method measures LLD while standing, with lifts used to level the pelvis, preferably a pelvic leveling device.23 The height of the lifts needed to level the pelvis is the difference in leg length. This clinical method takes into account functional factors such as foot, knee and hip position. However, one of the disadvantages of this method is that if asymmetrical loading of the legs or inconsistent compensations occur while standing, a false positive result can result.21 Friberg et al. reported found the indirect method to be inaccurate and highly imprecise, with observer error being ±7.5 mm. The authors determined that, more than half (53%) of the observations were erroneous when the criterion of leg length inequality was 5 mm. Clinical methods also failed to determine the presence or absence of length inequality of >5 mm which occurred in 54 measurements (27% of the total). In 13% of the measurements, the observers erred in determining the longer leg, even when radiological readings accorded a leg length inequality of as much as 25 mm.22 Hanada et al. found the indirect method to be highly reliable and moderately valid, however they observed that the indirect method underestimated the induced LLD by 3.8 ± 10.3 mm and the radiologic measure by 5.1 ± 8.6 mm.24 However, Woerman, & Binder-Macleod reported that the mean difference between iliac crest palpation and block correction measurements compared to radiographic measurements was 2.2 ± 2.6 mm, concluding that the indirect method was the most accurate and precise clinical method for determining LLD.21

To summarize, the disagreement in the literature regarding the reliability and validity of these methods, where some authors favor the direct or indirect method, could be attributed to several potential sources of error such as: difficulty of palpating bony landmarks, anatomical bony asymmetry, bony anomalies of the ASIS and malleoli, excess soft tissue due to overweight and differences in leg circumference and angular deformities. In addition, another important factor that might lead to differences of opinion of this issue is the presence of biomechanical deviations. These deviations may lead to functional discrepancy such as joint contractures, static structural malalignment or dynamic deviation such as knee valgus or varus, abnormal hip adduction or knee flexion which limit the reliability and validity of these clinical methods, hence, a more functional and dynamic method is required.

To the best of our knowledge, to date, no method has as yet been proposed to meet the functional requirement. We propose a functional measurement approach utilized during walking, based on the kinematic outcome of the lower limb movement throughout the gait cycle. Herein, we introduce a new concept which provides a new insight into the detection of LLD and leads to a better understanding of the contribution of dynamic deviations to asymmetry.

2. Methods

2.1. Assessment of dynamic LLD during the gait cycle based on the conventional gait model

3D gait analysis acquires and converts images of a person walking, into quantifiable data describing the motions and forces involved.25 Briefly, the conventional gait model simplifies the complexity of human movement and renders this into simple concepts that both modern computers and the human mind can process.26 The underlying biomechanical model, is known by several names, ie Modified Helen Hayes (MHH), Kadaba, Newington, Gage or Davis.26, 27

This biomechanical modelling is based on the assumption that movements of the lower limbs can be represented by the movement of seven rigid segments: the pelvis, two thighs, two lower legs and two feet.26 These rigid segments are connected by joints assumed to be ball and socket joints with three degrees of freedom.28 The movements taking place in each joint are: flexion/extension, adduction/abduction, internal and external rotation. Markers are used to define the segments. The segments are defined by three points, with a position and an orientation in space.26 Markers are placed on the surface of the subject’s skin and aligned with specific bony landmarks and joint axis. When the subject walks along the central walkway (in the laboratory), the location of these markers are monitored with a 3D motion data capture system. The biomechanical model is hierarchical, meaning that the definition of the distal segment is based on the location of the proximal segment.28, 29, 30

2.2. Body segments and joint center location for measuring dynamic LLD during the gait cycle

2.2.1. Pelvis

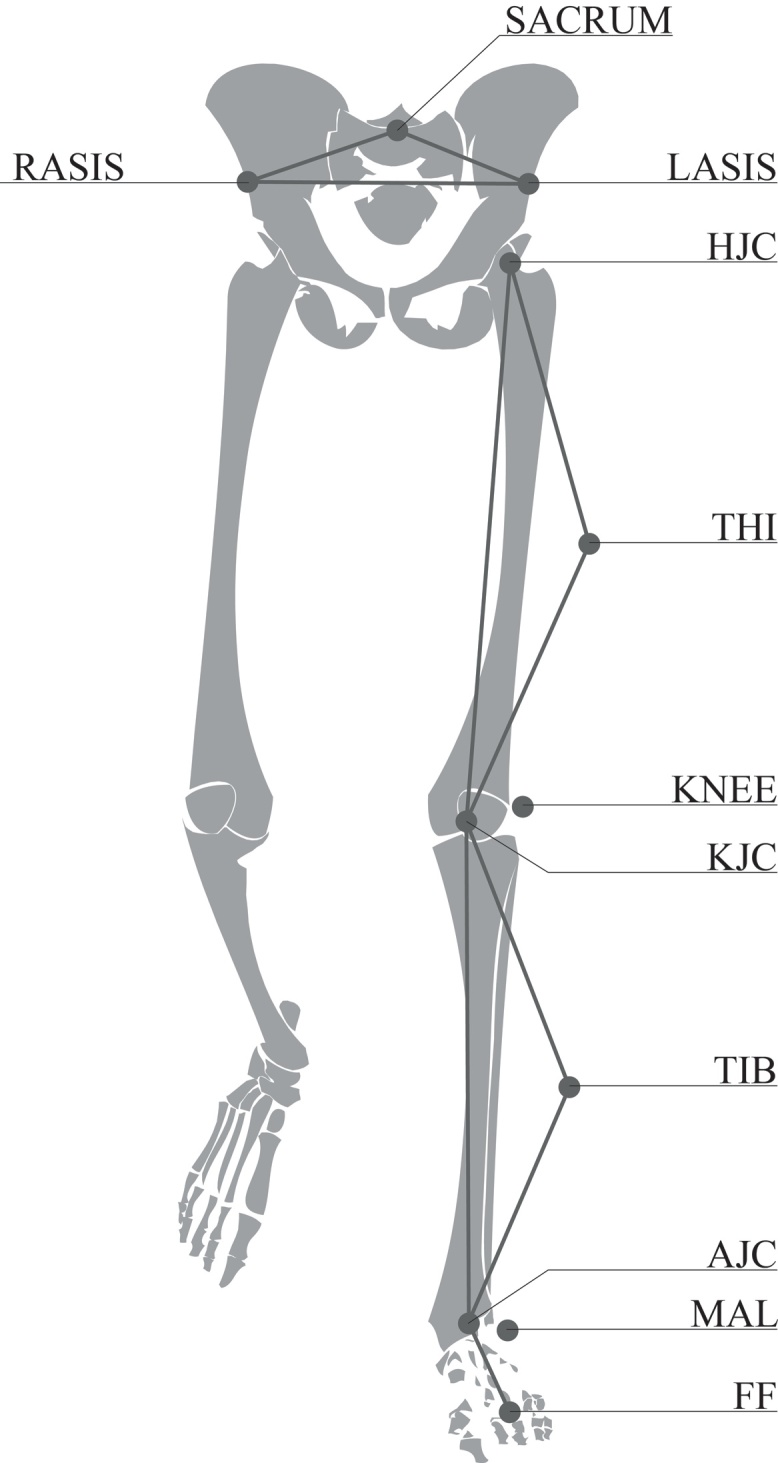

The pelvis segment coordinate system is defined by the waist markers − the axis between the two anterior superior spines, which is assumed to be parallel to the line between the hip joint centers (HJC). The third point defining the plane is the midpoint between the two posterior superior iliac spines on the sacrum (Fig. 1). Together these form the pelvis triangle specifying its position and orientation. The ASIS markers are also used to determine the lateral positions of the HJC within the pelvis segment.

Fig. 1.

Pelvis segment defined by two ASIS (LASIS, RASIS) and a sacral marker (SACRUM). Femur segment defined by the hip joint center (HJC), knee joint center (KJC) and lateral epicondyle marker (KNEE). Thigh marker (THI) defining plane of rotation. Tibia segment defined by knee joint center (KJC), ankle joint center (AJC) and lateral malleolus marker (MAL). Tibia marker (TIB) defining plane of rotation. Forefoot (FF) to AJC defining foot line.

2.2.2. Femur

The femoral segment is represented by a line through the knee joint axis defined by a marker placed on the lateral femur condyle and the calculated virtual marker assumed to be the HJC. The line and the point create a triangle for the femur, identifying its position and orientation.26 The thigh marker defines the plane of rotation (Fig. 1).

2.2.3. Tibia

The tibia segment is similarly represented, with a line passing through the ankle joint center (AJC) defined by a marker placed on the lateral malleolus and the virtual knee joint center. The tibia marker defines the plane of rotation. Together these form the tibia triangle identifying its position and orientation (Fig. 1).

2.2.4. Foot

The foot is represented as a one-dimensional unit vector, with a reference point at the AJC and at the forefoot marker (FF) placed along the foot axis, along the second ray and parallel to the plantar surface of the foot (Fig. 1). The position of each joint center is defined within its proximal segment. Joint centers are calculated according to marker placement and the subject’s anthropometric parameters.

Changes in lower extremity and pelvic alignment are captured and processed by a motion analysis system. Pelvic orientation is defined according to the laboratory’s zero reference point. Hip joint angles are defined as thigh with respect to pelvis movements; knee angle − as shank with respect to the thigh movements; and ankle angles − as foot with respect to shank movements.

Measuring dynamic leg length during the gait cycle takes into account the bony segmental length (foot segment, shank segment, thigh segment) and kinematic angles of the lower extremity in the sagittal, frontal and horizontal plane. Dynamic leg length is the effective length of the lower limb, measured by the distance from the HJC to the heel (HEEL), AJC or FF. Dynamic leg length will be compared to the contra lateral side.

2.3. A case report to test the feasibility of the method

An 18 year old male with a shorter left lower limb by 24 mm, revealed on a standing x-ray, underwent a gait laboratory evaluation using a motion analysis system (8 MX3 cameras, Vicon®, Oxford Metrics, UK), according to the PlugInGait biomechanical model31 to measure gait deviations in the lower extremities and pelvis. A thorough clinical and musculoskeletal evaluation included a lower extremity range of motion and anthropometric and skeletal alignment measurements. Thirteen reflective passive skin markers were placed on his pelvis and lower limbs according to the Helen Hayes protocol.32 Joint centers were calculated according to marker placement and the subject’s anthropometric parameters. Distance between the HJC and HEEL and the AJC and FF was measured. The average of the 3 walking trials’ data were sampled from six captured trials.

3. Results

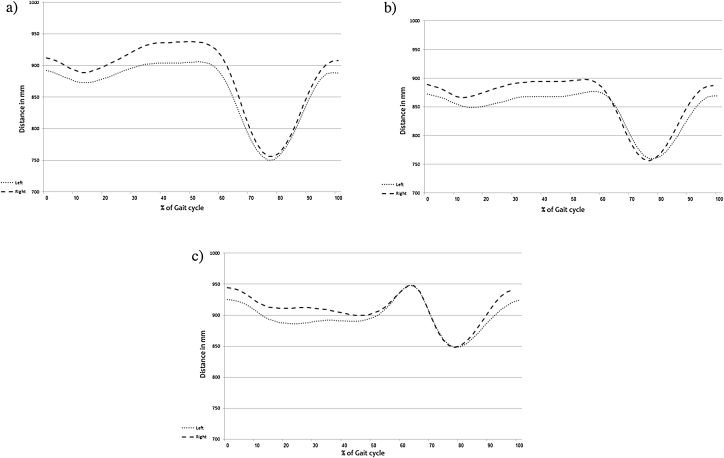

In the tested subject, we demonstrated the average change in leg length during the gait cycle from the HJC to HEEL and the AJC to the FF. It can be seen in Fig. 3 that the lower limb is functionally longer during the stance phase and subsequently shortens during the swing phase for clearance. Our results reveal a functionally shorter left lower limb, in concurrence with the x-ray findings. All dynamic measurements revealed a shorter left lower limb during the stance phase. Furthermore, the HJC to FF distance during the initial swing phase was symmetrical due to the compensatory ankle plantar flexion.

Fig. 3.

a. HJC to HEEL distance during the gait cycle; b. HJC to AJC distance during the gait cycle; c. HJC to FF distance during the gait cycle. Left side: Dotted line; Right side: Dashed line.

In normal gait, at heel initial contact to the footflat phase, the distance taken should be from the HJC to the HEEL (Fig. 2a). From the footflat to heel rise phase, HJC to any of the three points, could be selected as long as the comparison between the sides is consistent (Fig. 2b). However, at heel rise (Fig. 2c), the HJC to FF should be chosen. In addition, at mid swing phase (Fig. 2d), the FF marker is the most distal point and thus the distance to that point should be calculated.

Fig. 2.

Dynamic leg length during the gait cycle. Solid line represents distance from HJC to HEEL; dashed line represents distance from HJC to AJC and dotted line represents distance from HJC to FF. a: Left heel initial contact phase − distance to heel should be measured in this instance. b: Left mid stance phase. All three measurements could be chosen; however, according to the measument chosen, comparison to the contra lateral side should be done. c: Left heel rise phase − distance to FF should be measured. d: Left mid swing phase − distance to FF should be measured.

This approach provides a measurement for FLLD caused by pathological gait deviations. Depending on the gait deviations, a proper distance should be chosen, ie, if the patient made initial contact with the FF, the measurement would be taken from the HJC to the FF. In a knee flexion contracture or valgus deformity condition, the functional leg length of the HJC to the AJC during mid stance can approximate the degree of shortening during the stance phase and assist the clinician in determining the height of lift that will be needed for compensation.

4. Discussion

There are still differences of opinions as to the role LLD plays in musculoskeletal disorders and the recognized extent of LLD necessary to warrant corrective support such as a heel or shoe lift. Some investigators accept as much as 20–30 mm, while others define a significant discrepancy of 3–5 mm.33 This wide spectrum has triggered controversy in clinical decision-making as to which leg discrepancy is considered significant which might lead to biomechanical deformities or disturbing symptoms and thus needs to be addressed and corrected. The origin of this controversy is the various methods employed and their accuracy in determining the presence of FLLD.

Previous clinical methods have limited reliability and depending on them for determining the need for intervention, might be misleading. Imaging has a relatively high validity and reliability; however, it is expensive and exposes the subject to radiation. Moreover, these measurements are performed statically and might overlook the dynamic function of the subject. More comprehensive evaluations such as gait analysis can enhance accuracy and provide a detailed valid and reliable evaluation of deviations and the resultant change in the effective leg length.

Data representation of the kinematics and dynamic length of the lower extremities can be presented and the interpretation of the data can aid in recognizing the contribution of segmental alignment and joint movement on effective leg length and accordingly, decide if there is a need for intervention. According to the dynamic leg length and time of its occurrence in the gait cycle, a thorough understanding of the functional leg length should be ascertained and accordingly, determine more reliable conclusions prior to intervention.

The TLLD of the shorter left lower limb, by 24 mm, of our tested subject was also found in his dynamic measurement during the stance phase while walking. However, his dynamic LLD was more symmetrical during the swing phase, which appears to be due to compensatory strategies. Accordingly, this new concept of measuring LLD, based on a valid and reliable gait model, is feasible and we recommend further research to determine its reliability and validity as a functional dynamic measurement of LLD.

5. Conclusion

The detection of LLD should be based on the integration of static clinical measurements, imaging if available, and dynamic leg length during the gait cycle. The combination of these measurements can provide a more precise measurement and thus a more reliable recommendation for intervention.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. Phyllis Curchack Kornspan for her editorial services, and Mrs. Talia Herman for her editorial perspectives.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Brady R.J., Dean J.B., Skinner T.M., Gross M.T. Limb length inequality: clinical implications for assessment and intervention. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(5):221–234. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.5.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baylis W.J., Rzonca E.C. Functional and structural limb length discrepancies: evaluation and treatment. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1988;5(3):509–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danbert R.J. Clinical assessment and treatment of leg length inequalities. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1988;11(4):290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh M., Connolly P., Jenkinson A., O'Brien T. Leg length discrepancy–an experimental study of compensatory changes in three dimensions using gait analysis. Gait Posture. 2000;12(2):156–161. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amstutz H.C., Sakai D.N. Equalization of leg length. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;136:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iversen M.D., Chudasama N., Losina E., Katz J.N. Influence of self-reported limb length discrepancy on function and satisfaction 6 years after total hip replacement. J Geriatr Phys Ther (2001) 2011;34(3):148–152. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e31820e16dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitale M.A., Choe J.C., Sesko A.M. The effect of limb length discrepancy on health-related quality of life: is the ‘2 cm rule' appropriate? J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;15(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200601000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaron A.D., Eilert R.E. Results of the Wagner and Ilizarov methods of limb-lengthening. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(1):20–29. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Amico M. Scoliosis and leg asymmetries: a reliable approach to assess wedge solutions efficacy. Stud Health Technol Inf. 2002;88:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labaziewicz L., Nowakowski A. Scoliosis and postural defect. Pol Orthop Traumatol. 1996;61(3):247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose R., Fuentes A., Hamel B.J., Dzialo C.J. Pediatric leg length discrepancy: causes and treatments. Orthop Nurs. 1999;18(2):21–29. doi: 10.1097/00006416-199903000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stricker S., Hunt T. Evaluation of leg discrepancy in children. Pediatr Int. 2004;19:134–142. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young R.S., Andrew P.D., Cummings G.S. Effect of simulating leg length inequality on pelvic torsion and trunk mobility. Gait Posture. 2000;11(3):217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zabjek K.F., Leroux M.A., Coillard C. Acute postural adaptations induced by a shoe lift in idiopathic scoliosis patients. Eur Spine J. 2001;10(2):107–113. doi: 10.1007/s005860000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resende R.A., Kirkwood R.N., Deluzio K.J., Cabral S., Fonseca S.T. Biomechanical strategies implemented to compensate for mild leg length discrepancy during gait. Gait Posture. 2016;46:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knutson G.A. Anatomic and functional leg-length inequality: a review and recommendation for clinical decision-making Part I, anatomic leg-length inequality: prevalence, magnitude, effects and clinical significance. Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13:11. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey W.F., Yang M., Cooke T.D. Association of leg-length inequality with knee osteoarthritis: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(5):287–295. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabharwal S., Kumar A. Methods for assessing leg length discrepancy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(12):2910–2922. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0524-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neelly K., Wallmann H.W., Backus C.J. Validity of measuring leg length with a tape measure compared to a computed tomography scan. Physiother Theory Pract. 2013;29(6):487–492. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2012.755589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamaluddin S., Sulaiman A.R., Imran M.K., Juhara H., Ezane M.A., Nordin S. Reliability and accuracy of the tape measurement method with a nearest reading of 5 mm in the assessment of leg length discrepancy. Singapore Med J. 2011;52(9):681–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woerman A.L., Binder-Macleod S.A. Leg length discrepancy assessment: accuracv and precision in five clinical methods of evaluation*. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1984;5(5):230–239. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1984.5.5.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friberg O., Nurminen M., Korhonen K., Soininen E., Manttari T. Accuracy and precision of clinical estimation of leg length inequality and lumbar scoliosis: comparison of clinical and radiological measurements. Int Disabit Stud. 1988;10(2):49–53. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrone M.R., Guinn J., Reddin A., Sutlive T.G., Flynn T.W., Garber M.P. The accuracy of the Palpation Meter (PALM) for measuring pelvic crest height difference and leg length discrepancy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(6):319–325. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.6.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanada E., Kirby R.L., Mitchell M., Swuste J.M. Measuring leg-length discrepancy by the iliac crest palpation and book correction method: reliability and validity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(7):938–942. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.22622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perry J., Burnfield J. 2 ed. SLACK Incorporated; Thorofare, NJ: 2010. Gait Analysis Normal and Pathological Function. [Google Scholar]

- 26.2003. All You Ever Wanted to Know About the Conventional Gait Model but Were Afraid to Ask (CD-ROM) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirtley C. Elsevier; London: Churchill Livingstone: 2006. Clinical Gait Analysis: Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker R. Mac Keith Press; London: 2013. Measuring Walking A Handbook of Clinical Gait Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz M.H., Trost J.P., Wervey R.A. Measurement and management of errors in quantitative gait data. Gait Posture. 2004;20(2):196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker R. Gait analysis methods in rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2006;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kadaba M.P., Ramakrishnan H.K., Wootten M.E. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1990;8(3):383–392. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis R.B., Ounpuu S., Tyburski D., Gage J.R. A gait analysis data collection and reduction technique. Hum Mov Sci. 1991;10(5):575–587. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurney B. Leg length discrepancy. Gait Posture. 2002;15(2):195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]