Abstract

Objective

Ovarian anaplastic ependymoma is a rare gynecologic malignancy that poses diagnostic and treatment challenges. Treatment of sub-optimally debulked disease usually portends poor prognosis. Molecular testing of tumor specimen can identify more specific targets for additional therapy such as estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER/PR).

Case

A 29-year-old woman presented with incidental finding of large bilateral adnexal masses and elevated CA 125. Biopsy proved anaplastic ovarian ependymoma with high ER/PR expression. She underwent sub-optimal surgical debulking followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) which resulted in a partial response. Due to extensive residual disease she has been maintained on anastrozole for over fifteen months without increased tumor burden. Targeted somatic mutation testing was negative for all high risk clinically useful variants.

Conclusion

Aromatase inhibitors may be considered in patients with extra-axial anaplastic ependymoma and can produce prolonged stable disease.

Keywords: Aromatase inhibitor, Ovarian anaplastic ependymoma

Highlights

-

•

Ovarian anaplastic ependymoma is a rare gynecologic malignancy.

-

•

Histology shows perivascular rosettes, hypercellularity, and nuclear atypia.

-

•

Standard therapy includes surgical debulking followed by chemotherapy with BEP.

-

•

Molecular diagnostics can identify estrogen and progesterone receptor expression.

-

•

ER/PR expression can help direct treatment with aromatase inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, ependymomas are thought to originate from neuroectodermal tissue, most commonly from spinal tissue or in the cranium. However, rarely, these tumors can proliferate outside the central nervous system. It has been theorized that ependymomas in the pelvis can arise from pluripotent stem cells of müllerian origin or from an established ovarian teratoma (Stolnicu et al., 2011).

Ovarian anaplastic ependymoma is a rare malignancy that poses numerous diagnostic and treatment challenges. Pathologic diagnosis is challenging due to diverse histologic characteristics such as: papillary areas with psammoma bodies, pseudofollicles, trabeculae and microcysts. These features and others can lead to misdiagnosis as papillary serous, struma ovarii, granulosa cell, Sertoli-Leydig cell, and wolffian duct tumors. Although only approximately 30% of intracranial ependymoma are classified as malignant, the lack of a uniform histologic definition of anaplasia makes the prognostic significance controversial (Chamberlain, 2003). Anaplastic features include: hypercellularity, cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, frequent mitosis, pseudopalisading necrosis, endothelial proliferation and the hallmark characteristic perivascular rosettes (Reni et al., 2007). Additionally, treatment is challenging due to the aggressive nature of the malignancy which frequently recurs within a year of optimal cytoreduction.

A review of the literature demonstrates that treatment of extra-axial ependymomas has largely revolved around treatment modalities designed for malignant germ cell tumors including surgical debulking followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and targeted radiotherapy. This traditional first-line approach rests with the dogma that four courses of bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) is effective in treatment of patients with incompletely resected ovarian germ cell tumors and should be given to all such patients (Hinton et al., 2003).

2. Case

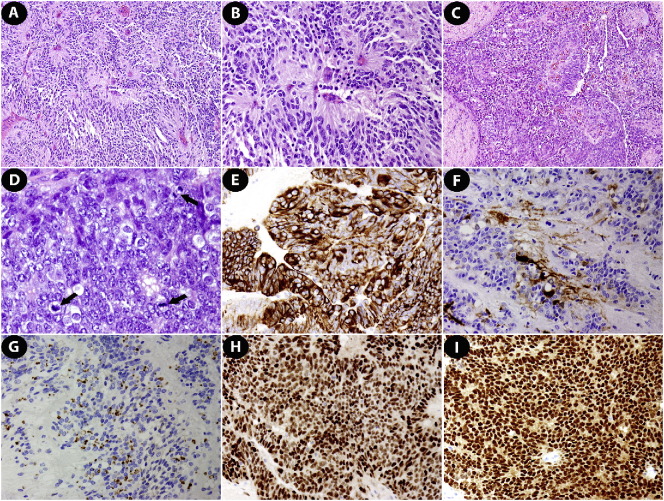

A 29-year-old female of middle eastern descent was incidentally diagnosed with a complex left ovarian pelvic mass in February 2015. This finding was identified during a hospitalization in Doha, Qatar for complications from elective breast augmentation. Pelvic ultrasound identified adnexal masses and MRI confirmed suspicion for malignancy. She presented to our facility in April 2015 for a second opinion regarding management. CT of the abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast revealed bilateral adnexal masses measuring approximately 14 x 11 cm on the right and 8 × 5.5 cm on the left which appeared inseparable from the uterus, extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis including a 6.3 cm implant in the hepatorenal space, supra and infracolic omental involvement and bilateral pleural effusions (Fig. 1). Tumor marker screen revealed significantly elevated CA-125 of 875 U/mL. In May 2015 she underwent diagnostic laparoscopy with a preoperative presumptive diagnosis of metastatic ovarian cancer. Resulting laparoscopic predictive score was 12 out of 14 (Fagotti et al., 2006). Peritoneal and omental biopsies of suspicious implants were also performed at that time. Review of the final pathology revealed anaplastic ependymoma of extra-axial type. Microscopic examination showed glioneoplasm with formation of prominent perivascular pseudorosettes and focal solid or papillary pattern. Moreover, psammoma bodies were present. The tumor had marked hypercellularity, nuclear atypia and elevated mitotic activity. Immunohistochemical stains revealed tumor cells positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (95% strong), estrogen receptor (90% strong), progesterone receptor (90% strong), S-100 (focal), WT-1 (focal), P53 (rare) and PAX-8 (patchy), and negative for Sal-like protein 4 (SALL4). Characteristically, the immunostain of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) exhibited perinuclear dot-like pattern in some well differentiated tumor cells (Liang et al., 2016) (Fig. 2). In June 2015 she underwent uncomplicated exploratory laparotomy, bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy, bilateral ureterolysis and infracolic omentectomy with debulking of approximately 90% of disease. The uterus was left in situ due to extensive adhesive disease and concern for injury to the bladder during dissection. Postoperatively she underwent four cycles of bleomycin, etoposide & cisplatin (BEP) adjuvant chemotherapy. CT scan in September 2015 revealed evidence of residual disease. Molecular testing was performed with a 50-gene somatic mutation analysis panel using PCR-based next generation sequencing developed by the Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and was negative for all high risk clinically useful variants (Appendix 1). She was started on anastrozole 1 mg daily. The most recent CT chest, abdomen and pelvis performed December 2016 reveals stable peritoneal carcinomatosis. CA-125 levels have also normalized and correlate with disease regression as exemplified (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Ovarian anaplastic ependymoma demonstrated on initial computed tomography (CT) scan at time of diagnosis. Bilateral adnexal masses (white arrows) and bulky pelvic disease (black arrow).

Fig. 2.

The anaplastic ependymoma exhibited perivascular pseudorosettes (A & B), papillary (C), and solid architectural patterns with multiple mitotic Figures (D, black arrows). Tumor cells were positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (E), S-100 (F), epithelial membrane antigen (G), ER (H) and PR (I). A–D, hematoxylin & eosin; E–I, immunohistochemistry; A & C: 100 ×; B & E–I: 200 ×; D: 400 ×.

Fig. 3.

CA 125 trend from time of initial diagnosis (4/2015), after tumor reducing surgery (6/2015) followed by BEP adjuvant chemotherapy (completed 9/2015) and then maintained on anastrozole 1 mg daily. Normal CA125 level 0–35 U/mL.

3. Discussion

The use of targeted hormonal therapy for estrogen and progesterone receptor (ER/PR) positive extra-axial ependymoma seems to have significant potential for adjudication of disease in carefully selected patients. Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor that prevents the peripheral conversion of androgens into estrogens. Although anastrozole has only been FDA approved to treat postmenopausal breast cancer, phase I and II trials have supported its safe use in recurrent endometrial cancer (Barakat et al., 2009). Interestingly, the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Ovarian Cancer, have identified use of anastrozole as a potentially active pharmacologic modality for use in hormonally responsive ovarian cancers such as low grade serous ovarian carcinoma and recurrent malignant sex cord stromal tumors (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2016). Dosages as low as 1 mg per day by mouth have proven efficacious at eliminating estradiol levels in the circulation to undetectable levels and higher levels of up to 1 mg/kg body weight do not impact adrenal corticosteroid production (Plourde et al., 1994). It should be noted that not all extra-axial ependymomas have ER/PR expression. Use of this strategy should be reserved for carefully selected patients.

Common side effects of anastrozole include asthenia, nausea, headache, hot flushes, and muscle pain although use is generally well tolerated. A recent large prospective placebo controlled study evaluated the efficacy and safety of anastrozole in the prevention of breast cancer in a group of high risk postmenopausal women (Cuzick et al., 2014). Musculoskeletal and vasomotor symptoms were significantly increased with anastrozole but also elevated in the placebo group. Frequency of carpal tunnel syndrome and dry eyes was significantly higher with anastrozole but still fairly rare. Incidence of hypertension was significantly increased in the anastrozole group however there were no significant differences between groups for cardiovascular events.

Our experience with anastrozole mirrors the success described by Deval, et al. in their published case report and has served as a promising therapeutic modality to halt ovarian anaplastic ependymoma tumor progression (Deval et al., 2014). Caution should be exercised not to attribute our success as a cure for anaplastic ovarian ependymoma as both case reports describe stability of pre-existing carcinomatosis and lack of recurrence at sites that underwent primary debulking but do not decrease tumor burden. Both reports also describe follow up time of only approximately one year, therefore overall survival data is still unknown with this therapy. However, in our case, the tumor burden is stable on CT imaging over the past year and CA-125 levels have down trended to normal levels. Although CA-125 levels have not been explicitly correlated with disease burden in extra-axial anaplastic ependymoma we found this test somewhat useful in this case.

The combination of paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin (TIP) has also been identified as another chemotherapeutic option in the setting of BEP resistant disease as described in a recent case report (Hino et al., 2016). This modality has achieved success in salvage treatment of testicular malignant germ cell tumors and its use has recently been extrapolated to ovarian ependymoma.

Ultimately, in the face of a new diagnosis of ovarian anaplastic ependymoma, careful histologic analysis of tumor specimens should be obtained to ensure that chemotherapy is targeted appropriately. The use of an aromatase inhibitor such as anastrozole should be strongly considered in patients who fail or do not tolerate chemotherapy, especially if the tumor has strong estrogen and progesterone receptor expression.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Molecular testing report of a 50-gene somatic mutation analysis panel using PCR-based next generation sequencing developed by the Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center which was negative for all high risk clinically useful variants.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors of this study have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Barakat R.R., Markman M., Randall M. Principles and practice of gynecologic oncology. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain M.C. Ependymomas. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2003;3:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s11910-003-0078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzick J., Sestak I., Forbes J.F., Dowsett M., Knox J., Cawthorn S., Saunders C., Roche N., Mansel R.E., Von Minckwitz G., Bonanni B., Palva T., Howell A. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deval B., Rousset P., Bigenwald C., Nogales F.F., Alexandre J. Treatment of ovarian anaplastic ependymoma by an aromatase inhibitor. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;123:488–491. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plourde P.V., Dyroff M., Dukes M. Arimidex: a potent and selective fourth-generation aromatase inhibitor. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1994;30:103–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00682745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagotti A., Ferrandina G., Fanfani F., Ercoli A., Lorusso D., Rossi M., Scambia G. A laparoscopy-based score to predict surgical outcome in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: a pilot study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006;13:1156–1161. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino M., Kobayashi Y., Wada M., Hattori Y., Kurahasi T., Nakagawa H. Complete response to paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin therapy in a case of ovarian ependymoma. Obs. Gynaecol. Res. 2016;42:1613–1617. doi: 10.1111/jog.13084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton S., Catalano P.J., Einhorn L.H., Nichols C.R., Crawford E.D., Vogelzang N., Trump D., Loehrer P.J. Cisplatin, etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in the treatment of disseminated germ cell tumors: final analysis of an intergroup trial. Cancer. 2003;97:1869–1875. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L., Olar A., Niu N., Jiang Y., Cheng W., Bian X., Yang W., Zhang J., Yemelyanova A., Malpica A., Zhang Z., Fuller G., Liu J. Primary glial and neuronal tumors of the ovary or peritoneum: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016;40:847–856. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network National Comprehensive Cancer. Ovarian cancer: including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer. NCCN Clin. Pract. Guid. Oncol. 2016;1:1–115. [Google Scholar]

- Reni M., Gatta G., Mazza E., Vecht C. Ependymoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007;63:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.03.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.03.004 S1040-8428(07)00057-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolnicu S., Furtado A., Sanches A., Nicolae A., Preda O., Hincu M., Nogales F.F. Ovarian ependymomas of extra-axial type or central immunophenotypes. Hum. Pathol. 2011;42:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Molecular testing report of a 50-gene somatic mutation analysis panel using PCR-based next generation sequencing developed by the Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center which was negative for all high risk clinically useful variants.