Abstract

Introduction

There are two main choices of anti-coagulation in cerebral venous thrombosis: Unfractionated heparin versus low molecular weight heparin. A consensus is yet to be reached regarding which agent is optimal. Therefore the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to identify which agent is most effective in treating CVT.

Methods

Databases Pubmed (MEDLINE), Google Scholar and hand-picked references from papers of interest were reviewed. Studies comparing the use of low molecular weight heparin and unfractionated heparin in adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of cerebral vein thrombosis were selected. Data was recorded for patient mortality, functional outcome and haemorrhagic complications of therapy.

Results

A total of 2761 papers were identified, 74 abstracts were screened, with 5 papers being read in full text and three studies suitable for final inclusion. A total of 179 patients were in the LMWH group and 352 patients were in the UH group. Mortality and functional outcome trended towards favouring LMWH with OR [95% CI] of 0.51 [0.23, 1.10], p = 0.09 and 0.79 [0.49, 1.26] p = 0.32 respectively. There was no difference in extra-cranial haemorrhage rates between either agent with a OR [95% CI] of 1.00 [0.29, 3.52] p = 0.99.

Conclusion

Trends towards improved mortality and improved functional outcomes were seen in patients treated with LMWH. No result reached statistical significance due to low numbers of studies available for inclusion. There is a need for further large scale randomized trials to definitively investigate the potential benefits of LMWH in the treatment of CVT.

Keywords: Cerebral venous thrombosis, Low molecular weight heparin, Unfractionated heparin, Meta-analysis

Highlights

-

•

3 studies were included for meta-analysis comparing LMWH and UH in the immediate management of CVT, a total of 179 and 372 patients in the LMWH and UH group respectively.

-

•

LMWH showed trends towards improved mortality and functional outcome.

-

•

Low number of clinical trials impeded analysis.

-

•

A high power randomized controlled trial is required to conclusively answer the question.

1. Introduction

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare but potentially devastating condition. CVT has an estimated incidence of 3–4 people per 1 million of the population and a pre-disposition to affect young females [1]. The main stay of treatment for CVT surrounds early recognition, and more recently trials have shown anti-coagulation with heparin either in unfractionated or low molecular weight forms can improve outcome in CVT despite the risk of haemorrhagic transformation [2].

A number of trials compared UH and LMWH in the setting of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the legs during the nineties [3], leading to the conclusion that LMWH is a suitable and safer alternative to UH in this cohort of patients. LMWH is now the established gold standard treatment in most units in the United Kingdom for DVT. A similar approach has been emerging in the treatment of CVT; examining LMWH and UH, however no clear consensus appears to have been reached. There are two main issues in terms of identifying if UH or LMWH is superior in the treatment of CVT: 1) the disease is relatively rare making randomised trials with sufficient power difficult 2) the risk of haemorrhagic transformation in CVT have made the use of anti-coagulation controversial in the past [4]. In 2012 a Cochrane review by Coutinho et al. demonstrated that anti-coagulation is safe in CVT, however there remains limited evidence as to which form of anti-coagulation is optimal [5].

LWMH has a number of benefits over UH. LMWH can be given in once or twice daily regimes without the need for activated partial thromboplastin time ratio (APTR) titration or a continuous intravenous infusion that is needed with UH. In addition to this they appear to have a better safety profile reducing the risks of heparin induced thrombocytopenia and bleeding theoretically having the potential to reduce the risk of haemorrhagic transformation [6]. However, LMWH does not provide the rapid onset of action and easy reversibility that is possible with UH.

Therefore we aim to report the results of the first combined systematic review and meta-analysis examining the use of LMWH versus UH in CVT. It is hoped that by compiling a number of trial results that it is possible to suggest which therapy is superior and safer in the treatment of CVT to guide further research and evidence.

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement. Pubmed and Google Scholar were searched for the terms “cerebral vein thrombosis” and “heparin” on the 23rd June 2016. References were hand-picked from papers which were read in full text. Inclusion criteria included papers comparing low molecular weight heparin with unfractionated in patients over 18 with CVT diagnosed by MR venography. Prospective studies were permitted to increase the power of the study. Papers not available in full text in English were excluded. Paper identification was undertaken by two independent reviewers AP and AQ and any disagreements were resolved by discussion until agreement was reached.

Outcomes for mortality, functional outcome and both intra-cranial and extra-cranial haemorrhage were analysed. All papers were evaluated for bias. All statistical analysis was undertaken using the Revman© software. If heterogeneity is low a fixed effects analysis will be used, if the results are varied a random effects analysis will be deemed more appropriate. Statistical significance is set at p = 0.05.

3. Results

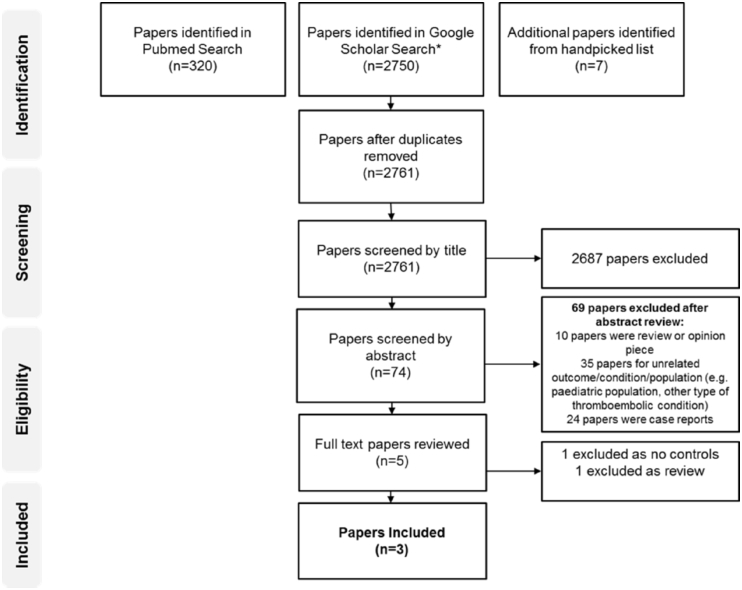

A total of 2761 non-duplicate papers were retrieved from our initial search. 74 abstracts were screened, with 5 papers were read in full text. Three papers were suitable for analysis published between 2010 and 2015 [7], [8], [9]; 1 prospective cohort study and two randomized controlled trials (see Fig. 1 for the search strategy protocol). In total 179 patients were treated with LMWH and 352 patients were treated in UH group (see Table 1 for the study characteristics). Two papers favoured the use of LMWH and one was equivalent.

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart depicting search strategy. 2761 non-duplicate papers were reviewed, with three studies undergoing final selection for inclusion.

Table 1.

Flow-chart depicting search strategy. 2761 non-duplicate papers were reviewed, with three studies undergoing final selection for inclusion.

| Paper (Location) | Study design | Numbers |

Anti-coagulation regime | Outcomes measured | Favours? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH | UH | |||||

| Coutinho et al., 2010 | Nonrandomized comparison of a prospective cohort study (ISCVT) | 119 | 302 | Worldwide cohort study – the LMWH or UH protocol was conducted as per local protocol |

Primary Outcome: MRS at 6 months Secondary Outcomes: Clinical worsening Extracranial haemorrhage, New Intracranial haemorrhage |

LMWH |

| Misra et al., 2012 (India) |

Randomized control trial (Non-blinded) | 34 | 32 |

LMWH: Delteparin 100 units/kg subcutaneous twice daily. UH: Loading dose of 80 units/kg bolus followed by 18 units/kg/hour to maintain and APTT of 1.5–2.5 for 14 days. Patients were then converted to oral anticoagulation (acenocoumarol) for 6 months or more depending on cause. |

Primary Outcome: In-hospital mortality Secondary Outcome: Barthel Index at 3 months |

LMWH |

| Afshari et al., 2015 (Iran) |

Randomized double blind trial | 26 | 18 |

LMWH: Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice a day UH: Loading dose of 80 units/kg followed by 18 units/kg/hour to maintain and aPTT of 65–85 s. Patients received 7–10 days of anti-coagulation and then were converted to oral anti-coagulation for 6 months. |

Primary Outcome: In-hospital mortality and neurological deficit assessed by the NIHSS at time of discharge and at one month. Secondary Outcome: Modified Rankin Scale at 30 day follow up, haemorrhagic complications (symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage requiring re-imaging or major extracranial haemorrhage) |

Equivalent |

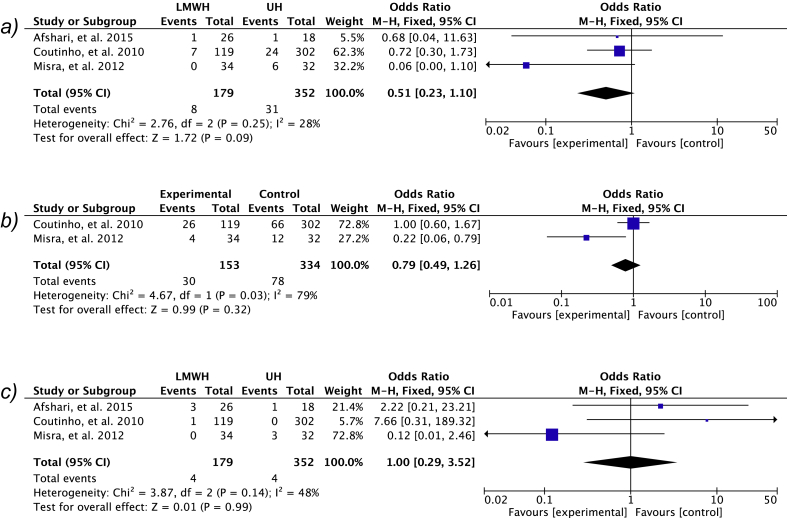

3.1. Mortality

All three studies were included for mortality analysis. Mortality was higher in the UH group in two of the studies and equivalent in the other. Meta-analysis of the data showed an OR [95% CI] of 0.51 [0.23, 1.10], p = 0.09 favouring LMWH (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis results for a) mortality b) functional outcome c) extra-cranial haemorrhage complications. A fixed effects analysis was used as heterogeneity was low.

3.2. Functional outcome

Afshari et al., were excluded for this part of the analysis as the data given was the average Modified Rankin Score (MRS) with standard deviations. The number of patients who did not make a complete functional recovery (demonstrated by and Barthel Index of 20/20 or a MRS of 0 was evaluated in both papers. Both studies demonstrate fewer incomplete recoveries in the LMWH however again this did not reach significance with a OR [95% CI] of 0.79 [0.49, 1.26] p = 0.32.

3.3. Complications

Rates of new intra-cranial haemorrhage were not included in the meta-analysis data as Misra et al. did not explicitly state the number of new intra-cranial haemorrhages in either group and there were no intra-cranial haemorrhages reported by Afshari et al. (2015). Coutinho et al. (2010) reported 10% and 16% new intra-cranial haemorrhages in the LMWH and UH groups respectively. All three papers reported rates of extra-cranial haemorrhages and these were all included for meta-analysis. There was no difference between the two groups in terms of overall extra-cranial haemorrhage events with a OR [95% CI] of 1.00 [0.29, 3.52] p = 0.99.

3.4. Bias and blinding

Only one trial was a randomized double-blind trial. The other trial whilst randomized was not blinded and the largest study of the three was a prospective cohort. All study outcomes were reported in full. Afshari et al. demonstrated the largest levels of patients lost to follow up, accounting for 18% of the total cohort.

4. Discussion

Low molecular weight heparin is rapidly overtaking unfractionated heparin as the anti-coagulant of choice in a number of thromboembolic diseases [10]. Volatility, expensiveness, and resource burden mean that UH is often a second line choice in such conditions. However, cerebral venous thrombosis remains a condition where there is no agreed anti-coagulant regime and both LMWH and UH are both commonly used with no concrete guidance as to which anti-coagulant is preferable. Therefore we report the results of the first meta-analysis comparing LMWH and UH in the treatment of CVT.

While we show trends towards improved mortality and functional outcomes in patients receiving LMWH with a relatively equivalent safety profile, any conclusions attempted to be drawn are significantly impeded by the limited number of studies on the subject. This is reflected in the inability to reach statistical significance for the differences seen in favour of LMWH for mortality and independence at long term follow up. Despite rigorous searches only a total 3 studies were able to be included with a total of 179 and 352 patients in the LMWH and UH groups respectively; a prospective cohort sub-set analysis, and two randomized controlled trials. Of the two trials only one attempted blinding investigators and patients, potentially weakening the strength of any conclusions (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Bias and blinding.

| Paper | Randomization technique | Participants blinded | Investigators blinded | Outcome reporting | Attrition bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coutinho et al. (2010) | Non-randomized | No blinding | No blinding | Both primary and secondary outcomes were reported fully. | 11 patients were lost to follow up in the LMWH group. 25 patients were lost to follow up in UH group. 9% and 8% respectively. |

| Misra et al. (2012) | Computer generated number allocation was used to randomize the patients | Participants were not blinded | Investigators were not blinded | Both primary and secondary outcomes were reported fully. | 1 patient lost to follow up in UH group |

| Afshari et al. (2015) | Computer generated number allocation was used to randomize patients. | Pre-printed medication codes were used to blind patients. | Investigators were blinded using pre-printed medication codes (However it is not stated whether blinding between IV and SC routes occurred). Treatment and evaluation was undertaken by different personnel. | Both primary and secondary outcomes were reported fully. | 8 patients were lost to follow up |

One of the key results from this meta-analysis is the finding that LMWH suggests to confer with an improved mortality in patients with CVT. In most of the trials much of the mortality associated with either of these treatments was on a background of haemorrhagic infarction which is associated with a poorer prognosis. Misra et al., showed that 6 patients in the UH group died as opposed to 0 in the LMWH. All patients who died had haemorrhagic infarction. It is not stated how many patients had haemorrhagic infarction in the two groups at presentation, however this may suggest that LMWH is safer in patients who have haemorrhagic infarction as opposed to showing that it is a superior anti-coagulant overall.

5. Conclusion

While the results of this meta-analysis suggest that LMWH displays trends towards lower mortality and improved functional outcome no statistical significance was reached likely due to the small number of studies available for inclusion. There was no evidence to suggest that LMWH is unsafe or increases the rate of haemorrhage in CVT. At best LMWH offers benefits in terms of outcomes over UH, at worst it is an equivalent but more convenient and more economic therapy in CVT. Ultimately, there is a need for further large scale randomized, effectively blinded trials comparing LMWH and UH and the fact that there is existing literature on this topic should not be off putting to future researchers looking to investigate this.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was required.

Funding

There was no funding provided for this research.

Author contribution

A. Qureshi – Writing the paper, data collection – first reviewer.

A. P. Perera – Study conception and design, statistical analysis – second reviewer.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of Interest are reported.

Guarantor

A. Perera.

Consent

Does not involve new recruitment of patients.

Registration of research studies

n/a.

References

- 1.Stam J. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1791–1798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra042354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einhaupl K.M., Villringer A., Mehraein S., Garner C., Pelllkofer R.L., Haberl R.L. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1991;2:597–600. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90607-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine M., Gent M., Hirsch J., Leclerc J., Anderson D., Weitz J. A comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin administered primarily at home with unfractionated heparin administered in hospital for proximal deep vein thrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334:677–681. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coutinho J.M., Stam J. How to treat cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. J. Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2010;8:877–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coutinho J.M., Sebastiann F.T.M., de Bruijin M.D., de Veber G., Stam J. Anticoagulation for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2012;43:e41–e42. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.111.648162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warkentin T.E., Levine M.N., Hirsh J., Horsewood P., Roberts R.S., Tech M., Gent M., Kelton J.G. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients treated with low-molecular-weight heparin or uncfractionated heparin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1330–1336. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutinho J.M., Ferro J.M., Canhao P., Barinagarrementeria F., Bousser M.G., Stam J. Unfractionated or low-molecular weight heparin for the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2010;41:2575–2580. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.588822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misra U.K., Kalita J., Chandra S., Kumar B., Bansal V. Low molecular weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012;19(7):1030–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afhari D., Nasrin M., Nasiri F., Razazian N., Bostani A., Sariaslani P. The efficacy and safery of low molecular weight heparin and unfractionated heparin in the treatment of cererbral venous sinus thrombosis. Neurosci. (Riyadh). 2015;20(4):357–361. doi: 10.17712/nsj.2015.4.20150375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merli G.J., Groce J.B. Pharmacological and clinical differences between low-molecular weight heparins: implications for prescribing practice and therapeutic interchange. Pharm. Ther. 2010;35(2):95–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]