Abstract

Objective

Serum sodium concentration is maintained by osmoregulation within normal range of 135-145 mmol/l. Previous analysis of data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed association of serum sodium with the 10-year risk scores of coronary heart disease and stroke. Current study evaluated the association of within-normal-range serum sodium with cardiovascular risk factors.

Approach and Results

Only participants who did not take cholesterol or blood pressure medications and had sodium within normal 135-145 mmol/l range were included (N=8617), and the cohort was stratified based on race, gender and smoking status. Multiple linear regression analysis of data from ARIC study was performed, with adjustment for age, blood glucose, insulin, glomerular filtration rate, body mass index, waist to hip ratio, and calorie intake. The analysis showed positive associations with sodium of total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio, apolipoprotein B, systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Increases in lipids and blood pressure associated with 10 mmol/l increase in sodium are similar to the increases associated with 7-10 years of aging. Analysis of sodium measurements made 3 years apart demonstrated that it is stable within 2-3 mmol/l explaining its association with long-term health outcomes. Furthermore, elevated sodium promoted lipid accumulation in cultured adipocytes suggesting direct causative effects on lipid metabolism

Conclusions

Serum sodium concentration is a cardiovascular risk factor even within the normal reference range. Thus, decreasing sodium to the lower end of the normal range by modification of water and salt intake is a personalizable strategy for decreasing cardiovascular risks.

Keywords: serum sodium, cholesterol, blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases, risk factors

Subject Codes: Cardiovascular Disease, Epidemiology, Risk Factors

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1, 2 Early identification of risk factors/biomarkers is important for timely implementation of preventive measures. Indeed, the identification and control of risk factors such as elevated blood glucose and cholesterol levels, as well as high blood pressure, have been successful in delaying development of CVDs. 3, 4

There is growing evidence that the small differences in plasma sodium between populations might have clinical consequences on health outcomes by directly or indirectly affecting vascular endothelial cells.5-9 Epidemiologic studies link high salt intake and conditions predisposing to dehydration, such as low water intake, diabetes and old age to increased risk of CVD 10-14. The underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. A common consequence of these conditions is elevation of plasma sodium. 11, 15-19 We previously demonstrated by multivariable analysis of data from Atherosclerosis Risk in Community (ARIC) study that serum sodium is positively associated with 10-year stroke risk score 6 and of the 10-year CHD risk score.7 Hypernatremia was associated with significantly increased mortality, largely from CVD, in the British Regional Heart Study.20 Also, higher levels of plasma sodium starting from 138 mmol/l were associated with higher risk of mortality in a healthy population with big increase of the risk when sodium level exceeded 145 mmol/l.21

For the current study we hypothesized that the association we found between serum sodium and 10-year CHD risk score that was retrospectively calculated for ARIC study participants might be due to its association with risk factors that have been identified in epidemiological studies and were used for the CHD risk estimation.22, 23 Elevated total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and blood pressure are associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and vascular death and are the main predictors of CHD risk.22-24 In the epidemiological studies mentioned above, major cardiovascular pathology occurred in people who had serum sodium outside of the normal range. The main objective of the present analysis was to determine if there is association of serum sodium with serum lipids and blood pressure even when the sodium is within the normal reference range. The ARIC study is optimal for such analysis since it was started at the time when cholesterol and blood pressure lowering medications were not widely used allowing true associations not obscured by ongoing treatments to be revealed. An additional important consideration for selecting subjects for the analysis was the requirement that their sodium concentration be within the normal range of 135-145 mmol/l so as to exclude people with ongoing acute or chronic abnormalities of water/salt balance that would obscure true long term associations of serum sodium with cardiovascular risk factors. After applying these filters, 8167 participants qualified, which is a large enough cohort for comprehensive analysis.

Materials and Methods

We used data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. The data were obtained from the NHLBI Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center. ARIC is a study of cardiovascular disease in a cohort of 15792 45- to 64-year-old black and white men and women sampled from four US communities in 1987–1989 25.

The plasma lipid measurements analyzed in the present study were low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, ratio of TC to HDL, and apolipoproteins AI and B. Other measurements included are blood glucose, blood insulin, body mass index, waist to hip ratio and calorie intake. Details of these measurements were reported in ARIC publications 25, 26. Serum sodium was measured by sodium selective electrode in plus LYTES Option of DACOS Analyzer (Coulter electronics, Inc). Manuals for ARIC plasma lipids, blood pressure, serum sodium and other measurements can be accessed online (https://www2.cscc.unc.edu/aric/cohort-manuals).

Since blood pressure and lipids levels are the main variables tested for association with serum sodium in our analysis, we excluded participants who took cholesterol (n=452) and blood pressure (n=4003) lowering medications. In order to exclude participants with water/salt balance abnormalities, only those with serum sodium within the normal range (135-145 mmol/l) were included. 8,617 participants remained for analysis.

For analysis of the association of serum sodium with serum lipids and blood pressure, we used data obtained during the baseline examination. Logarithmic transformation of HDL, ratio of TC to HDL and apolipoprotein A-I was used to improve the normality of their distributions (Fig IS). Multiple regression analysis 27-29 was used to assess the association of serum sodium with each of the risk factors separately: low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, ratio of total cholesterol to HDL, apolipoproteins A-I and B, and systolic and diastolic BP. Risk factors were treated as dependent variable and serum sodium level was treated as the predictor variable. Age was included in all regression models as second independent variable as it is a known predictor for the variables analyzed here.1 Six other confounding factors, blood glucose, insulin, glomerular filtration rate, body mass index, waist to hip ratio, and calorie intake, were also controlled for in some models to detect the serum sodium effect independent of these factors.

Detailed Materials and Methods are available in the online-only Data Supplement

Results

Positive association of serum sodium and levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol to HDL ratio, apolipoprotein B and blood pressure

In our previous analysis of data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Community (ARIC) study, we demonstrated that serum sodium concentration during the baseline examination was associated with 10-year CHD risk score 7 and 10-year stroke risk score 6 (the predicted 10 year risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke calculated for each participant by ARIC investigators, based on the study outcomes 22, 23, 30). We hypothesized for the present analysis that sodium might also be associated with some of the risk factors that were used in the calculations. Blood lipid composition and blood pressure are the most prominent factors, after adjustment for age, affecting risk of CHD 31, and blood pressure is most prominent factor for risk of stroke.30, 32 Therefore, we examined the relationship between sodium concentration and these risk factors, using multiple linear regressions adjusted for age.

Table IS presents the summary statistics (mean and standard deviation) of the risk factors analyzed and the demographics of the study participants included in the analysis. After exclusions of participants who took blood pressure and cholesterol lowering medications and those with serum sodium outside normal range of 135-145 mmol/l, 8617 remained for the analysis: 3164 white men, 3691 white women, 739 black men and 1021 black women. All groups had same average age of 52 years and mean serum sodium concentration of 141 mmol/l.

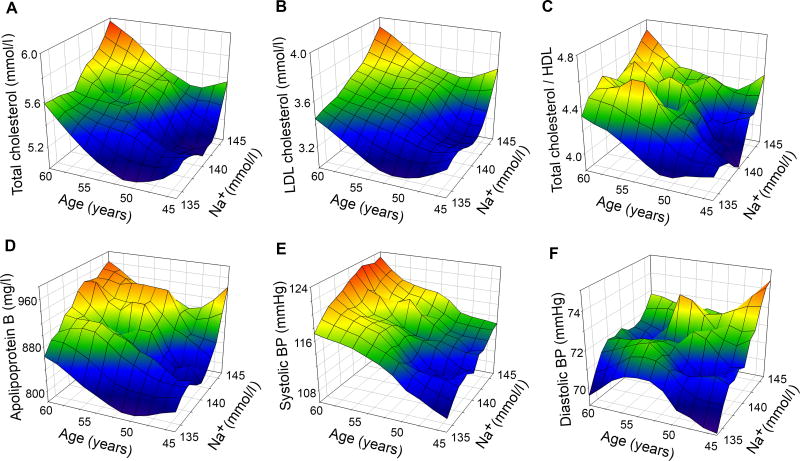

Multiple regression analysis indicates that total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio, and apolipoprotein B, as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressure, are each significantly associated with serum sodium level after adjusting for age (Table 1). Figure 1 contains 3D mesh graphs illustrating this relationship between serum sodium, age, and each of the risk factors. The graphs demonstrate that higher levels of serum sodium at all ages correspond to higher levels of total cholesterol (A), LDL-cholesterol (B), Total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio (C), apolipoprotein B (D), systolic BP (E) and diastolic BP (F). An increase of serum sodium from 135 mmol/l to 145 mmol/l is associated with a 4.2 mmHg increase in systolic BP (βNa= 0.42, 95% CI=0.25-0.59) and with a 2.5 mmHg increase of diastolic blood pressure (βNa = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.15-0.37). A similar increase in systolic BP is associated with a 7 year increase in age (βage = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.54-0.70). A 10 mmol/l increase in serum sodium is associated with 0.35 mmol/l (13.5 mg/dl) increase in total cholesterol (βNa= 0.035, 95% CI = 0.024-0.045), and a similar increase in cholesterol is associated with a 10 year increase in age (βage= 0.035, 95% CI = 0.030-0.040).

Table 1. Multiple regression analysis of association of the blood cholesterol, apolipoproteins and blood pressure with serum Na+ (mmol/l) and age (years).

See Table S2 for Gender and Race stratification.

Regression model: dependent variable = α + βNa ([serum Na]) + βage (age)

| Dependent variable | α | βNa | βage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| βNa (P value) | 95% confidence interval | βage (P value) | 95% confidence interval | ||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/l | -1.27 | 0.035** (6.82E-11) | 0.024 - 0.045 | 0.035** (6.1E-45) | 0.030 - 0.040 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/l | -3.02 | 0.036** (2.10E-12) | 0.026 - 0.046 | 0.028** (1.54E-33) | 0.024 - 0.033 |

| Ln(HDL) | -0.05 | 0.002 (n.s.) | -0.001 - 0.005 | -0.0004 (n.s.) | -0.002 - 0.001 |

| Ln(Total cholesterol/HDL) | 0.48 | 0.004* (0.025) | 0.0005 - 0.008 | 0.007** (4.86E-15) | 0.005 - 0.008 |

| Ln(Apolipoprotein A-I) | 6.96 | 0.001 (n.s) | -0.001 - 0.003 | 0.0008 (n.s.) | -0.0002 - 0.002 |

| Apolipoprotein B, mg/l | -653.6 | 8.42** (4.61E-9) | 5.60 - 11.23 | 7.23** (1.08E-27) | 5.93 - 8.52 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 25.9 | 0.42** (1.31E-06) | 0.25 - 0.59 | 0.62** (7.84E-55) | 0.54 - 0.70 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 38.3 | 0.25** (2.60E-06) | 0.15 - 0.37 | -0.05 (n.s.) | -0.10 - 0.004 |

P<0.05;

P<0.001;

n.s. - not significant

Note: participants who took cholesterol or blood pressure medications or had serum sodium outside 135-145 mmol/l range were excluded from the analysis

Figure 1. 3D Mesh Plots, visualising level of plasma cholesterol, apolipoproteins and Blood pressure as functions of serum sodium concentration and age observed in ARIC study participants.

Plasma sodium is positively associated with blood level of A) Total Cholesterol, B) LDL-cholesterol, C) Total Cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio, D) Apolipoprotein B, E) Systolic BP and F) Diastolic BP. See also Table 1 and Table IIS presenting results of the multivariable regression analysis.

Table IIS indicates that the association between serum sodium and blood pressure after adjustment for age is the most significant for black men (8 mmHg (βNa= 0.80, 95% CI = 0.12-1.50) per 10 mmol/l sodium) and lowest for black women (no significant association). Also, the relation between serum sodium and both cholesterol and apolipoprotein B levels is greater for white women than for white men. Among blacks, there is no significant relation of lipids with serum sodium except for the association of LDL cholesterol with serum sodium in men.

Having found positive association of blood lipid and of blood pressure with serum sodium (Fig 1, Table 1, table IS), we then looked for confounders that could be responsible for the observed associations. After adjustment for potential confounders available in ARIC study, such as blood glucose, blood insulin, glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), waist to hip ratio (WHR), body mass index (BMI) and caloric intake, serum sodium remained an independent predictor significantly associated with blood lipid and blood pressure both for the whole analyzed cohort (Table 2) and after stratification for Race and Gender (Table IIIS) as well, as for smoking status (Table 3).

Table 2. Multiple regression analysis of association of the blood lipids, apolipoprotein B and blood pressure with serum Na+ (mmol/l) adjusted by age, blood glucose and insulin, eGFR, waist to hip ratio, body mass index and calorie intake.

See Table S3 for Gender and Race stratification.

Regression model: Dependent variable = α + βNa ([Na]) + βage (age) + βglucose ([Glucose]) + βInsulin ([Insulin]) + βeGFR(eGFR) + βWHR (WHR) + βBMI (BMI) + βCalorie Intake (Calorie Intake). The table shows β coefficients and their significance for each predictor variable.

| Predictors | Dependent variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| TCH | LDL | Ln(TCH/HDL) | APB | SBP | DBP | |

| Constant (α) | -2.5 | -4.7 | -1.17 | -1358.5 | -31.3 | 11.1 |

| Serum Na+ | 0.040** | 0.038** | 5.4E-03** | 9.85** | 0.44** | 0.23** |

| Age | 0.028** | 0.019** | -5.5E-04 (n.s.) | 4.16** | 0.66** | -0.023 (n.s.) |

| Glucose | 0.047** | 0.030** | 0.017** | 14.3** | 0.81** | 0.033 (n.s.) |

| Insulin | -1.7E-04* | -2.6E-04** | 2.3E-06 (n.s.) | -0.038 (n.s.) | 5.0E-03** | 2.1E-03* |

| eGFR | -3.4E-03** | -4.2E-03** | -2.1E-03** | -1.10** | 0.21** | 0.118** |

| WHR | 0.91** | 2.07** | 1.92** | 689.1** | 13.1** | 10.8** |

| BMI | 2.1E-03 (n.s.) | 4.8E-03* | 4.6E-03** | 1.56* | 0.72** | 0.43** |

| Calorie Intake | -5.0E-05* | -3.3E-05* | 2.0E-05** | -6.8E-03 (n.s.) | 4.3E-04 (n.s.) | 3.1E-04* |

P<0.05;

P<0.001;

n.s. - not significant

Abbreviations and units of measure: Glucose, mmol/l; TCH – Total Cholesterol, mmol/L; HDL – HDL Cholesterol, mmol/L; APB – Apolipoprotein B, mg/L; Insulin, pmol/L; WHR - Waist-to-Hip Ratio; BMI – Body Mass Index in Kg/m2; Calorie Intake – total calorie intake from dietary and ethanol consumption, Kcal/day; SPB – Systolic Blood pressure, mmHg; DBP – Diastolic Blood Pressure, mmHg; eGFR – estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, mL/min

Note: participants who took cholesterol or blood pressure medications or had serum sodium outside 135-145 mmol/l range were excluded from the analysis

Table 3. Multiple regression analysis of association of the blood lipids, apolipoprotein B and blood pressure with serum Na+ (mmol/l) adjusted by age, blood glucose and insulin, eGFR, waist to hip ratio, body mass index and calorie intake: stratification by smoking status.

| Predictors | Dependent variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| TCH | LDL | Ln(TCH/HDL) | APB | SBP | DBP | |

| Non-smokers (N=6175): | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Constant (α) | -2.55 | -4.92 | -1.31 | -1405 | -32.5 | 6.1 |

| Serum Na+ | 0.038** | 0.036** | 0.005* | 0.51** | 0.27** | |

| Age | 0.033** | 0.024** | 0.001 (n.s.) | 5.5** | 0.60** | -0.058* |

| Glucose | 0.041** | 0.027** | 0.017** | 13.0** | 0.52** | -0.13 (n.s.) |

| Insulin | -1.3E-04 (n.s.) | -2.0E-04* | -1.7E-06 (n.s.) | -0.029 (n.s.) | 0.007** | 0.003** |

| eGFR | -7.1E-04 (n.s.) | -0.002 (n.s.) | -0.002** | -0.79* | 0.17** | 0.095** |

| WHR | 0.90** | 2.08** | 1.9** | 729.2** | 13.2** | 12.2** |

| BMI | 2.8E-03 (n.s.) | 0.006* | 0.005** | 2.4* | 0.73** | 0.43** |

| Calorie Intake | -3.0E-05 (n.s.) | -1.2E-05 (n.s.) | 2.3E-05** | -0.005 (n.s.) | 2.7E-04 (n.s.) | 2.8E-04 (n.s.) |

|

| ||||||

| Smokers (n=2394): | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Constant (α) | -2.69 | -4.42 | -0.75 | -1218 | -37.4 | 17.7 |

| Serum Na+ | 0.049** | 0.045** | 0.006* | 12.26** | 0.34* | 0.097 (n.s.) |

| Age | 0.019** | 0.009 (n.s.) | -0.005* | 1.1 (n.s.) | 0.81** | 0.044 (n.s.) |

| Glucose | 0.0638** | 0.042* | 0.016** | 17.4** | 1.67** | 0.48** |

| Insulin | -4.5E-04* | -6.1E-04* | 5.7E-05 (n.s.) | -0.075 (n.s.) | -0.008* | -0.004 (n.s.) |

| eGFR | -0.010** | -0.011** | -0.004** | -2.44** | 0.30** | 0.19** |

| WHR | 0.89* | 1.84** | 1.74** | 459.5** | 16.4* | 13.0** |

| BMI | 1.4E-03 (n.s.) | 0.008 (n.s.) | 0.008** | 2.16 (n.s.) | 0.62** | 0.30** |

| Calorie Intake | -8.9E-05* | -7.5E-05* | 9.0E-06 (n.s.) | -0.014 (n.s.) | 7.2E-04 (n.s.) | 4.3E-04 (n.s.) |

P<0.05;

P<0.001;

n.s. - not significant

Abbreviations and units of measure: Glucose, mmol/l; TCH – Total Cholesterol, mmol/L; HDL – HDL Cholesterol, mmol/L; APB – Apolipoprotein B, mg/L; Insulin, pmol/L; WHR - Waist-to-Hip Ratio; BMI – Body Mass Index in Kg/m2; Calorie Intake – total calorie intake from dietary and ethanol consumption, Kcal/day; SPB – Systolic Blood pressure, mmHg; DBP – Diastolic Blood Pressure, mmHg; eGFR – estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, mL/min

Note: participants who took cholesterol or blood pressure medications or had serum sodium outside 135-145 mmol/l range were excluded from the analysis

Long term stability of serum sodium

The ability of serum sodium concentration to serve as a predictor variable for future health outcomes such as CHD 7 and stroke 6 implies that it is stable for long enough to cause long-term effects. Serum sodium was recently proposed to be a long-term characteristic of individual persons.33 The conclusion was based on analysis of plasma sodium over a 10 year interval, using records from two large health plan-based cohorts. The analysis showed that serial plasma sodium values for any given individual tend to cluster around a patient-specific set point and that these set points vary between individuals.33 To examine the degree of stability of serum sodium among ARIC study participants we used the two serum sodium measurements made 3 years apart in visits 1 and visits 2 (Fig. 2). The significant positive correlation (r = 0.36 (95% CI: 0.34-0.37, P<0.0001) between visit 1 and visit 2 (Fig 2A) indicates that serum sodium concentration does not vary randomly, but is more or less stable in each person. We also compared the within-individual (WI) variance to the between-individual (BI) variance of serum sodium measured during the two visits. BI variance (5.62 (mmol/l)2) is much higher than the WI variance (1.78 (mmol/l)2), confirming that each person's serum sodium is relatively stable.

Figure 2. Serum sodium is stable in individuals over a long time.

Analysis of serum sodium of ARIC study participants measured in two visits 3 years apart. A) Assessment of long-term intraindividual variability of serum sodium concentration. Scatterplot depicting the correlation between serum sodium measured in each person during visit 1 versus that measured in the same person in visit 2. B, C) Degree of stability of serum sodium. B) Frequency distribution histogram of differences of serum Na+ concentration between the two visits. For 45% of ARIC participants the difference does not exceed 1 mmol/l, for 65% - 2 mmol/l and for 94% - 3 mmol/l. C) The difference of serum Na+ concentration between 2 visits versus the mean serum sodium of each person (mean±SD). The variability of serum Na is higher at the ends of normal range (SD increases from 2.5 mmol/l in the middle part of normal range to 3-4 mmol/l at 135 and 145 mmol/l).

Having confirmed that in individual ARIC study participants serum sodium is stable over the long term, we asked what range of serum sodium concentration the long term stability occurs over. Analysis of differences in sodium concentration between the two visits of each person demonstrates that for 45% of ARIC participants the difference does not exceed 1 mmol/l, for 65% - 2 mmol/l and for 94% - 3 mmol/l (Fig 2B). Variability of serum sodium is lowest in the middle part of the normal range and increases towards lower and higher ends of normal range. For 68% (1 SD) the difference between visits is 2.5 mmol/l if their mean serum sodium is 141 mmol/l, but it is 3.8 mmol/l if their mean serum sodium is 135 or 145 mmol/l. (Fig.2C)

Positive association of 10-year stroke risk score and of the 10-year CHD risk score with within-normal-range serum sodium

In our previous analysis of association of serum sodium with 10-year stroke risk score6 and of the 10-year CHD risk score7 participants with sodium levels outside normal range were included. We now checked if these associations are still present when only people with normal serum sodium levels are included. Analysis shown on Table IVS demonstrates that 10 years risk scores of CHD and stroke are still associated with serum sodium and this association is eliminated after adjustments for total cholesterol and blood pressure. This result suggests the possibility that blood lipids and blood pressure could be the mediating variables for these associations and that serum sodium could potentially serve as preventive target.

Direct effect of elevated extracellular sodium on lipid content of adipocytes

Having found a cross-sectional association of blood lipids with serum sodium concentration, we then asked if elevated extracellular sodium might directly affect lipid metabolism. We tested the effect of extracellular sodium on accumulation of lipids in cultured adipocytes. (Fig 3) After differentiating murine preadipose cells (3T3-L1) into adipocytes, we cultured them in media with sodium concentrations ranging from 135 mmol/l to 165 mmol/l. (Fig 3A and methods) Measurement of lipid content of the adipocytes throughout the process demonstrated that elevated sodium increases lipid accumulation (Fig 3B, 3C, 3D). Thus, elevated extracellular sodium directly increases adipocyte lipid content. To get some insight on whether observed effects of elevated sodium is specific to sodium itself or to hypertonicity that it creates 34, we examined effect of sorbitol on lipid accumulation. Similar to NaCl, elevation of tonicity of cell culture medium by sorbitol increased accumulation of lipids by adipocytes (Fig IIS) suggesting that increased tonicity rather than specific sodium effects might be responsible for observed changes in lipid metabolism.

Figure 3. Elevated extracellular sodium increases lipids accumulation in cultured adipocytes.

A ) Overview of adipocytes differentiation protocol. 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes were grown on 96 well plates. Differentiation to adipocytes was performed by changing the medium for 3 days to the medium supplemented with differentiation factors and containing different concentrations of sodium: 135, 145, 155 and 165 mmol/l. After 3 days, differentiation factors were removed and adipocytes were maintained in medium with different sodium concentrations. B) Representative images of adipocytes at day 6 and day 12 after differentiation start showing accumulation of lipid droplets. Cells maintained in medium with 145 mmol/l sodium accumulated more lipids than cells in 135 mmol/l sodium. C) Representative image of adipocytes stained with AdipoRed for quantification of lipids content. D) Time course of lipid accumulation in adipocytes maintained in media containing different concentrations of sodium. Lipids content is quantified as Integral Green Fluorescence from corresponding wells of 96 well plate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, N=5; *P<0.05; **P<0.01, unpaired, two-tailed t test relative to 135 mmol/l (significance level is similar for 145,155 and 165 mmol/l). See related Figure IIS.

Positive association of serum sodium with Body Mass Index (BMI) and Waist to Hip ratio in the ARIC study

The stimulation of lipid content of adipocytes by elevated extracellular sodium (Fig 3) suggested that serum sodium might be associated with BMI and WHR. Indeed, multivariate regression analysis in ARIC data shows positive association of BMI and WHR with serum sodium after adjustment for possible confounders such as age, blood glucose and calorie intake (Table 4). This result suggests that elevated serum and extracellular sodium concentration even within the normal range may stimulate accumulation of lipids in adipose tissue leading to increased BMI and WHR and to increased cardiovascular risk. It is worth noting that serum sodium remains a significant predictor of blood lipid level even after adjustment for BMI and WHR (Tables 1, 2, 3, IIIS).

Table 4. Multiple regression analysis of association of Body Mass Index (BMI) and Waist to Hip Ration (WHR) with serum Na+ (mmol/l) adjusted by age, blood glucose and calorie intake.

Regression model: Dependent variable = α + βNa ([Na]) + βage (age) + βglucose ([Glucose]) + βCalorie Intake (Calorie Intake). The table shows β coefficients and their significance for each predictor variable.

| Predictors | Dependent variables | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| BMI | WHR | |

| Constant (α) | 11.9 | 0.51 |

| Serum Na+, mmol/L | 0.092** | 1.3E-03** |

| Age, years | -0.034* | 2.9E-03** |

| Glucose, mmol/l | 0.612** | 0.009** |

| Calorie Intake, Kcal/day | 2.2E-04* | 1.6E-05** |

P<0.05;

P<0.001

Discussion

Sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) are the major electrolytes in plasma and extracellular fluids. Their concentration is maintained by osmoregulation within a normal reference range for serum sodium of 135- 145 mmol/l.35 Our previous analysis of data from the ARIC study showed that serum sodium was associated with 10-year risk scores of CHD7 and stroke.6 In the British Regional Heart Study, hypernatremia was associated with significantly increased mortality, largely from CVD.20 Also, higher levels of plasma sodium starting from 138 mmol/l were associated with higher risk of mortality in a healthy population with big increase of the risk when sodium level exceeded 145 mmol/l.21 In attempt to understand possible mechanisms behind these associations, in the present studies we analyzed association between serum sodium and traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as serum lipids and blood pressure that are the major contributors for risks of CHD and Stroke. 24 In the epidemiological studies mentioned above, major cardiovascular pathology occurred in people who had serum sodium outside of the normal range. To exclude such people in our current analysis, we included only people with sodium concentration within normal range. People who took cholesterol and blood pressure lowering medications were also excluded since such ongoing treatments could obscure true associations and decrease the power of the analysis. In this selective cohort, serum sodium was still associated with 10-year risk scores of CHD and stroke. (Table IVS)

Our analysis of the ARIC data in the present study reveals cross-sectional positive association of the traditional risk factors for cardiovascular diseases 24, such as total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio, apolipoprotein B and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure with serum sodium. Serum sodium was a significant predictor variable for them when adjusting only for age (Fig 1, Table 1, Table IIS). It remained a significant predictor after further adjusting for multiple possible confounders such as blood glucose, blood insulin, eGFR, BMI, WHR and calorie intake (Table 2) as well as after stratification based on race and gender (Table IIIS) or smoking status (Table 3). Blood lipids and blood pressure are major contributors to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis 36, 37, which is the underlying cause of the majority of cardiovascular events. Atherosclerosis and accumulation of plaques are life-long processes that start early in life. Total and LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and atherosclerosis gradually increase with age 1 until they are high enough to cause clinically-evident cardiovascular diseases. This makes age, itself, a very strong risk factor for CVDs.38 Our regression analysis reveals that 10 mmol/l higher serum sodium, which is within the normal range, increases plasma lipids and blood pressure as much as 7-10 years of aging. (Table 1)

Consistent with the possibility that higher serum sodium is a cardiovascular risk factor even within normal range that allows only 10 mmol/l variation, our analysis demonstrates that serum sodium is stable over long times in ARIC study participants (Fig 2), which is necessary if it is to serve as a predictor of future health outcomes such as CHD, stroke and overall mortality. 6, 7, 20, 21 Specifically, our analysis of two sodium measurements taken 3 years apart in the ARIC study shows that a majority of people maintain serum sodium concentration that is stable to within 2 mmol/l. (Fig 2) Such narrow range of sodium stability indicate that even within normal range people have opportunity to shift their serum sodium level by simple modifications of water/salt intake leading to changes in hydration status.

A major goal in fighting CVDs is finding modifiable factors that can delay the progression of preclinical atherosclerosis. Identification of high cholesterol and high blood pressure as cardiovascular risk factors and their control by blood pressure and cholesterol lowering medications, have succeeded in delaying development of CVDs 3, 4, 39 Our data imply that decreasing plasma sodium concentration even within normal range might also decrease risk of CVDs through its effects on blood lipid level and blood pressure. A limitation of cross-sectional analysis is that such analysis cannot by itself prove a causative effect of sodium on dependent variables. However, the data presented in Fig 3, show that elevation of extracellular sodium increases lipids in cultured adipocytes, indicating that extracellular sodium can serve as direct modulator of lipid metabolism. In addition, data accumulating in recent years indicates that elevated extracellular sodium has direct proinflammatory 5, 7, prothrombotic6 and stiffening 8 effects on the vascular endothelium, which could be involved in the associations revealed in current study. Since endothelial activation leads to the release of coagulation and inflammation mediators, contributing to the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis 40, 41, further studies of those mechanisms could help understand the associations found in the epidemiological studies.

The adverse cardiovascular effects of elevated extracellular sodium might potentially be related to the fact that sodium is a functionally impermeant solute, meaning that elevation of extracellular sodium is hypertonic. High sodium causes osmotic efflux of water from cells, leading to decreased cell volume and increased intracellular ionic strength. Adaptive cellular responses are activated to compensate for the dehydration and its consequences by the transcription factor NFAT5, which is activated by hypertonicity. Hypertonicity increases the expression of NFAT5 mRNA and protein, increases NFAT5 transcriptional activity, and mediates transcription of many NFAT5 target genes that are directly or indirectly involved in adaptation to high NaCl.42, 43 The expression of NFAT5 increases from mild water restriction that increases plasma sodium by as little as 5 mmol/l.6 Moreover, activated, NFAT5 binds to the promoter of the vWF gene, suggesting that it may be involved in the pro-thrombotic effects of increased extracellular sodium.6 Consistent with a pro-atherogenic effect of NFAT5, development of atherosclerosis is delayed in NFAT5+/−ApoE−/−mice.44 Further, NFAT5 increases in skin macrophages when high salt intake leads to sodium accumulation in the skin and is implicated in promotion of lymphatic growth and induction of salt-sensitive hypertension.45, 46 Accelerated lipid accumulation in cultured adipocytes by both elevated sodium and sorbitol shown in this study (Fig IIS), suggest that hypertonicity- induced NFAT5 signaling might be involved in regulation of lipid metabolism. More studies are needed to further elucidate the role of NFAT5 in the effects of elevated serum sodium on CVDs.

Serum sodium concentration is affected by water/salt balance and is an indicator of overall hydration. Factors affecting plasma sodium concentration also include, for example, diabetes and aging. Thus, both diabetes and aging predispose to dehydration, leading to increased plasma sodium concentration 15, 16, 18, 19 and both of them increase risk of CVDs 38, 47, again consistent with involvement of higher plasma sodium as a risk factor for CVD. In addition to direct effects of elevated sodium and resultant hypetonicity outlined above, other indirect factors could mediate associations detected in current study. For example, levels of AVP increases proportionally with extracellular osmolality, and recent studies are finding positive associations of AVP marker copeptin with increased risks of CVDs48-50. Deciphering the mechanisms involved may help identify new risk factors more proximal to the initial causes, help develop preventive measures, and target specific therapies.51 Life style-dependent factors affecting serum sodium concentration include the balance between water intake and excretion, affecting the general level of hydration 16, 52, as well as salt intake 17, 53, 54. Therefore, simple modification of water and salt consumption sufficient to lower plasma sodium could lower serum lipids and blood pressure and, thus, the rate of development of atherosclerosis and the long term risk of CVDs.

Perspective

Usually, little attention is paid to variation of serum sodium within its normal range. The associations found in the current study between traditional cardiovascular risk factors and serum sodium that exists even within the normal range suggest that it could be beneficial for everybody's long term health to shift serum sodium to the lower end of that range. Water and salt intake are the obvious variables, but recommendations for regulating them have not sufficed, so knowledge of additional measures could be helpful.

Plasma sodium concentration is rarely analyzed in epidemiological studies of normal subjects, even when effects of salt and water intake are investigated, probably due to its narrow normal range and lack of belief that variation within that range matters. Our analysis, however, demonstrates that plasma sodium is stable in individuals within 2-3 mmol/l over long time periods and is positively associated with cardiovascular risk factors even within normal range of 135-145 mmol/l. Thus, including an analysis of serum sodium concentration in epidemiological studies of cardiovascular effects of water and salt intake could facilitate interpretation of the results and help better understand how water-salt intake and their balance affect CVD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We analyzed data from Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

Serum sodium within normal range of 135-145 mmol/l is positively associated with serum lipids and blood pressure after controlling for age, blood glucose, insulin, glomerular filtration rate, body mass index, waist to hip ratio, and calorie intake and stratification based on race, gender and smoking status

Majority of ARIC study participants have serum sodium stable to within 2 mmol/l, that is prerequisite for risk factors with potential for long-term effects

Decreasing of serum sodium by modifications of dietary water and salt could be used as personalizable strategy for decreasing cardiovascular risks

Acknowledgments

Data from Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study were obtained from the NHLBI Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC). The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions and for providing the data to the BioLINCC repository.

Sources of Funding: The study was funded by Intramural Program of National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- CHD

Coronary Heart Diesease

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- WHR

waist to hip ratio

- NFAT5

Nuclear Factor of Activated T-Cells 5

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update a report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2015;131:E29–E322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim GB. Global burden of cardiovascular disease. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2013;10:59–59. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: Meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. Bmj-British Medical Journal. 2009;338 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward S, Jones ML, Pandor A, Holmes M, Ara R, Ryan A, Yeo W, Payne N. A systematic review and economic evaluation of statins for the prevention of coronary events. Health Technology Assessment. 2007;11:1–+. doi: 10.3310/hta11140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wild J, Soehnlein O, Dietel B, Urschel K, Garlichs CD, Cicha I. Rubbing salt into wounded endothelium: Sodium potentiates proatherogenic effects of tnf-alpha under non-uniform shear stress. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2014;112:183–195. doi: 10.1160/TH13-11-0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dmitrieva NI, Burg MB. Secretion of von willebrand factor by endothelial cells links sodium to hypercoagulability and thrombosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:6485–6490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404809111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dmitrieva NI, Burg MB. Elevated sodium and dehydration stimulate inflammatory signaling in endothelial cells and promote atherosclerosis. Plos One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oberleithner H, Riethmueller C, Schillers H, MacGregor GA, de Wardener HE, Hausberg M. Plasma sodium stiffens vascular endothelium and reduces nitric oxide release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:16281–16286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707791104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberleithner H, Peters W, Kusche-Vihrog K, Korte S, Schillers H, Kliche K, Oberleithner K. Salt overload damages the glycocalyx sodium barrier of vascular endothelium. Pflugers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology. 2011;462:519–528. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0999-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan J, Knutsen SF, Blix GG, Lee JW, Fraser GE. Water, other fluids, and fatal coronary heart disease - the adventist health study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:827–833. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.9.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He FJ, Macgregor GA. Salt intake, plasma sodium, and worldwide salt reduction. Ann Med. 2012;44(1):S127–S137. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2012.660495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manz F, Wentz A. The importance of good hydration for the prevention of chronic diseases. Nutrition Reviews. 2005;63:S2–S5. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.North BJ, Sinclair DA. The intersection between aging and cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research. 2012;110:1097–1108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox CS. Cardiovascular disease risk factors, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the framingham heart study. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2010;20:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowen LE, Hodak SP, Verbalis JG. Age-associated abnormalities of water homeostasis. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2013;42:349–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senay LC, Christen Ml. Changes in blood plasma during progressive dehydration. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1965;20:1136–&. [Google Scholar]

- 17.He FJ, Markandu ND, Sagnella GA, de Wardener HE, Macgregor GA. Plasma sodium: Ignored and underestimated. Hypertension. 2005;45:98–102. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000149431.79450.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maletkovic J, Drexler A. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2013;42:677–+. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. Primary care - hypernatremia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:1493–1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L, Papacosta O, Whincup P. Mild hyponatremia, hypernatremia and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in older men: A population-based cohort study. Nutrition Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2016;26:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh SW, Baek SH, An JN, Goo HS, Kim S, Na KY, Chae DW, Kim S, Chin HJ. Small increases in plasma sodium are associated with higher risk of mortality in a healthy population. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2013;28:1034–1040. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.7.1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Sharrett AR, Sorlie P, Couper D, Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Coronary heart disease risk prediction in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2003;56:880–890. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Duncan BB, Gilbert AC, Pankow JS Atherosclerosis Risk Communities S. Prediction of coronary heard disease in middle-ages adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2777–2784. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alagona P, Jr, Ahmad TA. Cardiovascular disease risk assessment and prevention current guidelines and limitations. Medical Clinics of North America. 2015;99:711–+. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams OD. The atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study - design and objectives. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharrett AR, Patsch W, Sorlie PD, Heiss G, Bond MG, Davis CE. Associations of lipoprotein cholesterols, apolipoprotein-a-i and apolipoprotein-b, and triglycerides with carotid atherosclerosis and coronary heart-disease - the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis. 1994;14:1098–1104. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.7.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakkee M, Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. Multivariable analysis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2014;134:e20–e20. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.132. quiz e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz MH. Multivariable analysis: A primer for readers of medical research. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138:644–650. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz MH. Multivariable analysis A practical guide for clinicians and public health researches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chambless LE, Heiss G, Shahar E, Earp MJ, Toole J. Prediction of ischemic stroke risk in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;160:259–269. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson PWF, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf PA, Dagostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Probability of stroke - a risk profile from the framingham-study. Stroke. 1991;22:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Duckart J, Slatore CG, Fu Y, Petrik AF, Thorp ML, Cohen DM. Individuality of the plasma sodium concentration. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2014;306:F1534–1543. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00585.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burg MB, Ferraris JD, Dmitrieva NI. Cellular response to hyperosmotic stresses. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87 doi: 10.1152/physrev.00056.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Water. PoDRIfEa. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate / appendix j: Serum electrolyte concentrations nhanes iii, 1988-94; pp. 558–563. 20001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao WH, Newman WP, Tracy RE, Wattigney WA, Bogaulas Heart S. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:1650–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman WP, Freedman DS, Voors AW, Gard PD, Srinivasan SR, Cresanta JL, Williamson GD, Webber LS, Berenson GS. Relation of serum-lipoprotein levels and systolic blood-pressure to early atherosclerosis - the bogalusa heart-study. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;314:138–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601163140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seals DR, Jablonski KL, Donato AJ. Aging and vascular endothelial function in humans. Clinical Science. 2011;120:357–375. doi: 10.1042/CS20100476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Law M, Wald N, Morris J. Lowering blood pressure to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke: A new preventive strategy. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England) 2003;7:1–94. doi: 10.3310/hta7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pober JS, Sessa WC. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2007;7:803–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramcharan KS, Lip GYH, Stonelake PS, Blann AD. The endotheliome: A new concept in vascular biology. Thrombosis Research. 2011;128:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burg MB, Ferraris JD, Dmitrieva NI. Cellular response to hyperosmotic stresses. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87:1441–1474. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00056.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grady CR, Knepper MA, Burg MB, Ferraris JD. Database of osmoregulated proteins in mammalian cells. Physiological reports. 2014;2 doi: 10.14814/phy2.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halterman JA, Kwon HM, Leitinger N, Wamhoff BR. Nfat5 expression in bone marrow-derived cells enhances atherosclerosis and drives macrophage migration. Frontiers in Physiology. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiig H, Schroder A, Neuhofer W, et al. Immune cells control skin lymphatic electrolyte homeostasis and blood pressure. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123:2803–2815. doi: 10.1172/JCI60113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Titze J. A different view on sodium balance. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2015;24:14–20. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duca L, Sippl R, Snell-Bergeon JK. Is the risk and nature of cvd the same in type 1 and type 2 diabetes? Current Diabetes Reports. 2013;13:350–361. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0380-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christ-Crain M, Fenske W. Copeptin in the diagnosis of vasopressin-dependent disorders of fluid homeostasis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2016;12:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bjornstad P, Maahs DM, Jensen T, Lanasp MA, Johnson RJ, Rewers M, Snell-Bergeon JK. Elevated copeptin is associated with atherosclerosis and diabetic kidney disease in adults with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 2016;30:1093–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riphagen IJ, Boertien WE, Alkhalaf A, Kleefstra N, Gansevoort RT, Groenier KH, van Hateren KJJ, Struck J, Navis G, Bilo HJG, Bakker SJL. Copeptin, a surrogate marker for arginine vasopressin, is associated with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes (zodiac-31) Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3201–3207. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balagopal P, de Ferranti SD, Cook S, Daniels SR, Gidding SS, Hayman LL, McCrindle BW, Mietus-Snyder ML, Steinberger J Council Nutr Phys Act M, Council Epidemiology p. Nontraditional risk factors and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease: Mechanistic, research, and clinical considerations for youth a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2011;123:2749–2769. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31821c7c64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Armstrong LE. Challenges of linking chronic dehydration and fluid consumption to health outcomes. Nutrition Reviews. 2012;70:S121–S127. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, Elliott P. Salt intakes around the world: Implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:791–813. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suckling RJ, He FJ, Markandu ND, Macgregor GA. Dietary salt influences postprandial plasma sodium concentration and systolic blood pressure. Kidney Int. 2012;81:407–411. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.