Abstract

Some prior research has examined pain-related variables based on prescription opioid dose, but data from studies involving patient-reported outcomes have been limited. This study examined the relationships between prescription opioid dose and self-reported pain intensity, function, quality of life, and mental health. Participants were recruited from two large integrated health systems, Kaiser Permanente Northwest (n=331) and VA Portland Health Care System (n=186). To be included, participants had to have musculoskeletal pain diagnoses and be receiving stable doses of long-term opioid therapy (LTOT). We divided participants into three groups based on current prescription opioid dose in daily morphine equivalent doses (MED): Low Dose (5 – 20 mg MED), Moderate Dose (20.1 – 50 mg MED), and Higher Dose (50.1 – 120 mg MED) groups. A statistically significant trend emerged where higher prescription opioid dose was associated with moderately-sized effects including greater pain intensity, more impairments in functioning and quality of life, poorer self-efficacy for managing pain, greater fear avoidance, and more healthcare utilization. Rates of potential alcohol and substance use disorders also differed among groups. Findings from this evaluation reveal significant differences in pain-related and substance-related factors based on prescription opioid dose.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal pain, Opioids, Chronic pain

Introduction

As the use of prescription opioid medications for the treatment of chronic pain has increased, so has the use of high doses of opioids.4,35 Concerns exist about the safety and misuse of opioid medications generally, as they are associated with side effects and adverse events, including constipation, fatigue, nausea, dizziness, vomiting, purposeful abuse, and diversion.3,19,25 Relative to other analgesics, opioids carry increased likelihood of cardiovascular events, fractures, accidents, and death.7,39,43 The dose of opioids is a contributing factor in particular adverse events including fractures and emergency room visits.7,39 Recent studies have highlighted the relationship between opioid dose and overdose, specifically indicating higher opioid doses are associated with elevated risk of overdose death.6,16,20 The benefits associated with use of higher doses of prescription opioids have not been clearly described.

Some prior research, using electronic medical record (EMR) data, reveals that patients prescribed high doses of opioids are more likely to have comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders.27,33 In a retrospective cohort study, researchers found that patients who had increases in prescription opioid dose were more likely to have a substance use disorder and have more frequent visits to primary care.22 A limitation of prior research is the reliance on data extracted from the EMR to identify demographic and clinical factors associated with opioid dose and dose escalation. Little information is available on patient-reported outcomes associated with prescription opioid dose.

The purpose of this analysis was to build on prior research by examining pain-related factors, quality of life, and mental health based on prescription opioid dose. Patient-reported data are needed to understand the relationships between prescription opioid dose and pain-related factors. Based on prior retrospective research, we hypothesized that patients prescribed the highest doses of opioid medications, relative to patients prescribed lower doses, would report more pain and functional impairment, mental health problems, and issues with current alcohol and substance use. Data for this analysis were collected during the baseline assessment as part of an ongoing longitudinal study designed to examine predictors and outcomes of prescription opioid dose escalation.

Materials and Methods

Settings

Study settings included Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) and the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPORHCS). KPNW is an integrated health plan in Oregon and southwest Washington states, and maintains two hospitals and more than 30 medical clinics that provide a full range of medical, mental health, and addiction treatment. The VAPORHCS is a Department of Veterans Affairs hospital and treatment system located in Portland, Oregon. The VAPORHCS provides a full range of patient care services through primary, tertiary, and long-term care in all areas of medicine. These settings were chosen to reflect a range of patient demographic and clinical factors.

Participants

Participants were eligible for inclusion in this study if they had documentation of one or more musculoskeletal pain diagnoses recorded in their medical record in the past 12 months. Musculoskeletal pain diagnoses were chosen because they comprise the majority of chronic pain conditions.21 Participants must also have received a stable dose of at least 90 consecutive days of opioid therapy.17,47 To confirm dose stability for each potential participant, we calculated an average daily morphine equivalent dose (MED) during the 90 days prior to recruitment. Each prescription was categorized by type and multiplied by a conversion factor to determine the equivalent milligram amount per day of morphine (codeine was multiplied by 0.1667, fentanyl x 3.6, hydrocodone x 1.0, hydromorphone x 4.0, meperidine x 0.1, methadone x 3.5, morphine x 1.0, oxycodone x 1.5, oxymorphone x 3, and tramadol x 0.2). For the purpose of this study, we defined a stable dose as having no more than a 10% change in monthly MED during a 90 consecutive day period. We felt this degree of change permitted modest increases in opioid doses intended for a short duration (e.g., following a dental procedure). The only other inclusion criterion was the ability to read and write in English.

Participants were excluded if they endorsed pending litigation or disability claim related to a pain condition, age younger than 18 years, a cancer diagnosis, were enrolled in an opioid substitution program in the prior year, lack of telephone access, or had a current opioid dose greater than 120 mg MED. The latter were excluded because of our larger prospective cohort study was focused on opioid dose escalation; at the time of study enrollment, institutional policies at KPNW limited opioid doses above a certain threshold, possibly resulting in site-specific differences in opportunities for dose escalation. We also excluded potential participants whose only opioid prescriptions were for tramadol or buprenorphine.

Study Procedures

Using administrative databases at both clinical sites, we identified potential study participants on the basis of past-year ICD-9-CM diagnoses and current prescription opioid medication use. We sent a personalized study invitation card to each participant. Cards described the study, provided study contact information, and included a prepaid postcard to indicate or decline interest in participation. Study staff followed up by phone to provide additional study details, answer questions, and conduct a brief screening. Those who met preliminary inclusion criteria and indicated interest were scheduled for a baseline visit that typically took place in-person.

During the study visit, participants provided informed consent and completed a battery of self-report questionnaires (described below). Participants received a $50 store gift card for participating in the study.

All study procedures were reviewed, approved, and monitored by the KPNW and VAPORHCS Institutional Review Boards. All participants provided informed consent to participate.

Measures

EMR-derived variables

Prescription opioid, clinical diagnostic, and past-year medical care utilization (e.g., primary care, specialty care, mental health care, substance use care) data were extracted from the EMR. Each participant was considered to have a diagnosis if they were diagnosed with the condition in a clinical setting one or more times in the prior year.

Self-report measures

Basic demographic characteristics that were assessed include age, gender, race, marital status, employment, socioeconomic status, and disability status. In order to quantify current opioid dose, all participants were asked to verify current opioid prescription data and were asked about potential opioid prescriptions from outside sources.

The Chronic Pain Grade (GPG) was used to assess pain intensity and pain-related function. The CPG is a commonly used and well-validated measure that provides global scores of pain intensity and functioning.18,42 Quality of life was measured with the Short-Form Health Survey, Version 2, (SF-12v2)50 a 12-item well-validated self-report measure of quality of life that is sensitive to change and has been used in numerous epidemiological studies. The SF-12v2 provides subscale scores on physical and mental health functioning; higher scores are associated with better functioning. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) was used to assess depressive symptoms.30 The PHQ is a brief, reliable, and psychometrically valid measure used to screen for depressive symptoms.29,44 For this study, we administered the PHQ-8, which removes a question assessing current suicidal ideation. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale is a brief self-report measure designed to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms, and has been validated as a robust predictor of the different anxiety disorders.28,44 The 3-item AUDIT-C8 was used to screen for current alcohol use disorder. In this study, a potential alcohol use disorder was indicated for scores ≥ 5 for men and ≥ 4 for women. The Drug Abuse Screening Test-10 (DAST-10)41 is a 10-item measure used to assess misuse of illicit substances. A potential substance use disorder was defined as a DAST-10 score ≥ 2.12 The Pain Medication Questionnaire is a self-report measure designed to assess beliefs and behaviors related to the misuse of pain medications.1 Studies of the PMQ suggest it has good psychometric properties.15,23 We administered the 23-item version. Higher scores reflect greater risk for misuse of prescription opioids.

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale was used to assess catastrophizing.45 The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire is a 10-item test designed to assess perceived self-efficacy to cope with chronic pain.36 The Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire is a 16-item self-report measure;49 we administered the 5-item subscale querying beliefs about physical activity.

All of the above measures were used in the current study because of their strong psychometric properties, frequent use in the pain and/or substance abuse literature, and empirical evidence of associations with the clinical conditions under study. Further, they measure constructs of the biopsychosocial model of chronic pain.

Data Analysis

For the purpose of these analyses, enrolled participants were divided into three groups based on current MED. Those prescribed opioid doses between 5 and 20 mg daily MED were classified in the “Low Dose” group, individuals prescribed 20.1 – 50 mg daily MED were classified in the “Moderate Dose” group, and those prescribed more than 50 mg daily MED were classified in the “Higher Dose” group. The categorization for the Higher Dose group is a lower opioid dose than used in prior studies examining differences in clinical characteristics based on opioid dose27,33, but consistent with recent research that have examined adverse effects based on dose.6,16,20 To compare the demographic characteristics among the three dose groups, one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for normally distributed continuous measures and Kruskal Wallis test for non-normal data distribution; chi-square tests were used for categorical measures. Trend tests were carried out to assess the presence of significant trend in rates of diagnostic and healthcare utilization data across the three dose groups. In order to estimate the clinical significance of group differences, effect sizes were calculated, using Cohen’s d, on variables that were statistically significant.40 All data analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4. The a priori alpha level for all inferential analyses was set at 0.05; all statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

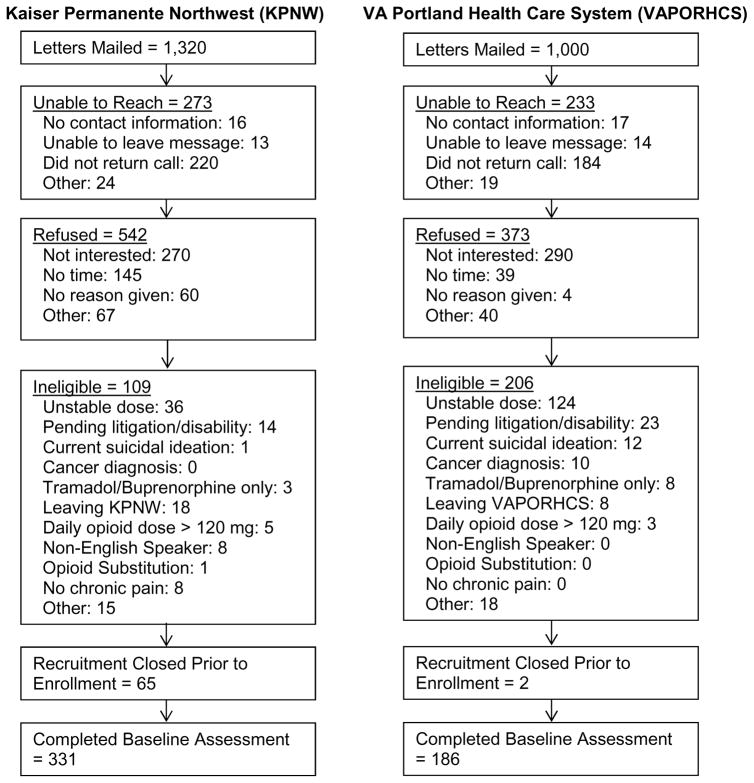

Figure 1 summarizes participants meeting study inclusion/exclusion criteria. Among 2,320 patients mailed study recruitment materials, 1,814 (78.2%) were contacted to screen for potential study inclusion, and 915 (50.4% of those contacted) declined. Of those patients who were contacted and expressed interest in participating, 315 (35.0%) were ineligible for the study and were excluded. We enrolled 517 participants (331 at KPNW and 186 at VAPORHCS).

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment flow.

We compared the demographic and pain-related variables between patients who did versus did not enroll in the study. The findings indicate that participants who did enroll were slightly older (59.4 years vs. 57.8 years), more often male (52.6% vs. 38.6%), and more likely to report non-white race/ethnicity (17.2% vs. 9.7%), compared with participants who were sent introductory letters but did not enroll in the study. There were no differences in enrollment rates based on average daily opioid dose or rate of pain-related diagnoses.

Among participants who enrolled in the study, the average age was 59 years; 47.4% were female. Most participants who enrolled reported white race/ethnicity (82.8%), and 57.1% were currently married or living with a partner. Nearly a quarter of the sample (24%) were currently receiving disability compensation, 29% reported a total household income less than $30,000. The average depression score on the PHQ-8 was 9.5 and 47% had a PHQ score > 10 suggesting high rates of clinically-significant depressive symptoms. As documented in the EMR, 5.8% of the sample had a current alcohol use disorder diagnosis and 4.3% had a diagnosis of a current substance use disorder. The largest proportion of participants (38.5%) were prescribed opioid doses between 5 and 20 mg daily MED (Low Dose Group); slightly fewer (36.8%) were prescribed 20.1 – 50 mg daily MED (Moderate Dose Group), and the reminder (24.8%) were prescribed more than 50 mg daily MED (Higher Dose Group).

The only demographic characteristic that significantly differed among the three dose-defined groups was working status. Participants in the Low Dose Group were significantly more likely to be currently working (41.2%) or retired (38.2%), whereas participants in the Moderate Dose and Higher Dose Group were more likely to be receiving disability benefits (31.1% and 29.7%, respectively). Participants in the Low Dose Group had the lowest rates of past-year arthritis diagnoses; rates of other musculoskeletal diagnoses did not show significant trend across the three dose groups. Based on diagnostic data from the EMR, there was a statistically significant trend for higher rates of depression and substance use disorders among patients in the Higher Dose group. No significant trend was observed on rates of other past-year psychiatric disorders. See Table 1 for a full summary of demographic characteristics and diagnostic data, based on average daily MED.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics and EMR-derived diagnoses based on prescription opioid dose.

| Low Dose Group (5 – 20 mg MED) n=199 |

Moderate Dose Group (20.1 – 50 mg MED) n=190 |

Higher Dose Group (50.1 – 120 mg MED) n=128 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.6 (12.0) | 58.9 (11.1) | 59.9 (10.7) | 0.501 |

| Female | 52.3% | 43.7% | 45.3% | 0.206 |

| White Race/Ethnicity | 85.4 | 81.6% | 80.5% | 0.402 |

| Education | 0.190 | |||

| High School or less | 19.1% | 20.5% | 22.7% | |

| Some College | 50.8% | 56.8% | 58.6% | |

| College Graduate or more | 30.2% | 22.6% | 18.8% | |

| Marital Status | 0.273 | |||

| Never married | 7.5% | 4.7% | 6.3% | |

| Widowed | 7.5% | 12.6% | 6.3% | |

| Divorced/Separated | 29.2% | 23.7% | 31.3% | |

| Married/Living with partner | 55.8% | 59.0% | 56.3% | |

| Employment Status | < 0.001 | |||

| Working | 41.2% | 34.7% | 24.2% | |

| Retired | 38.2% | 29.5% | 39.8% | |

| Unemployed | 8.0% | 4.7% | 6.3% | |

| Disabled | 12.6% | 31.1% | 29.7% | |

| Income | 0.425 | |||

| < $30,000 | 27.6% | 27.4% | 32.0% | |

| $30,000 – $69,999 | 42.2% | 46.3% | 48.4% | |

| $70,000 or more | 28.6% | 24.2% | 17.2% | |

| Arthritis | 54.3% | 67.4% | 65.6% | 0.021 |

| Back pain | 54.8% | 60.5% | 64.1% | 0.086 |

| Neck or joint pain | 53.8% | 56.8% | 46.1% | 0.243 |

| Depression | 31.7% | 34.2% | 43.0% | 0.044 |

| Bipolar disorder | 5.0% | 2.1% | 7.8% | 0.379 |

| PTSD | 15.6% | 14.2% | 15.6% | 0.964 |

| Other anxiety disorder | 15.1% | 18.4% | 20.3% | 0.210 |

| Nicotine use disorder | 16.6% | 20.0% | 24.2% | 0.090 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 5.0% | 5.8% | 7.0% | 0.454 |

| Other substance use disorder | 2.5% | 3.7% | 7.8% | 0.026 |

Note. Arthritis diagnoses included ICD-9-CM codes 712.xx, 714.xx – 716.xx, 720.xx, and 274.00; neck or joint pain diagnoses included 717.xx – 719.xx, 723.xx, and 729.xx; back pain diagnoses included 722.xx and 724.xx.

Scores of pain intensity showed a statistically significant quadratic trend with the increase of prescription opioid dose. This pattern was demonstrated by the significantly lower scores in the Low Dose (mean=59.9) group than the Moderate Dose (mean=64.5) group, and a slight decrease in mean pain intensity in the Higher Dose (mean=63.5) group (effect size between Moderate Dose and Low Dose groups was d = 0.32). The trend for escalating scores on pain disability was statistically significant, with participants in the higher dose groups reporting more disability than participants in the Low Dose group (effect size between High Dose and Low Dose groups was d = 0.36). The trend test also suggested poorer functioning on the SF-12v2 Physical Component score associated with higher opioid dose (effect size between High Dose and Low Dose groups was d = 0.45). There was no significant trend on the SF-12v2 Mental Component or other self-report measures of depression severity or anxiety (all p-values > 0.05). Trend tests on measures of self-efficacy for managing pain decreased (effect size between High Dose and Low Dose groups was d = 0.42) and fear avoidance beliefs about physical activity increased (effect size between High Dose and Low Dose groups was d = 0.39) as the opioid dose increased. There was no significant trend across the three dose groups on pain catastrophizing.

Participants in the Low Dose Group had the highest rates of problematic alcohol use on the AUDIT-C (21.1% vs 18.4% among Moderate Dose and 9.4% among Higher Dose; p = 0.008), but the lowest rates of potential substance use disorder on the DAST-10 (8.0% vs 14.2% among Moderate Dose and 19.5% among Higher Dose; p = 0.002). Table 2 summarizes differences among groups on self-reported clinical data.

Table 2.

Comparison of pain and mental health variables based on prescription opioid dose.

| Low Dose Group (5 – 20 mg MED) n=199 |

Moderate Dose (20.1 – 50 mg MED) n=190 |

Higher Dose (50.1 – 120 mg MED) n=128 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Intensity | 59.9 (14.0) | 64.5 (14.5) | 63.5 (13.6) | 0.013 |

| Pain Disability | 46.5 (24.7) | 52.1 (25.5) | 55.1 (23.1) | 0.002 |

| SF-12 Physical Composite Score | 35.3 (10.3) | 32.8 (10.8) | 30.8 (9.3) | <0.001 |

| SF-12 Mental Composite Score | 49.1 (10.8) | 48.2 (12.4) | 50.0 (10.3) | 0.571 |

| Depression Severity | 9.0 (5.7) | 9.9 (5.4) | 9.9 (5.5) | 0.121 |

| Anxiety Severity | 6.7 (5.6) | 6.7 (5.4) | 7.1 (5.6) | 0.499 |

| Potential Alcohol Use Disorder | 21.1% (42) | 18.4% (35) | 9.4% (12) | 0.008 |

| Potential Substance Use Disorder | 8.0% (16) | 14.2% (27) | 19.5% (25) | 0.002 |

| Risk for Prescription Opioid Misuse | 13.4 (7.6) | 14.5 (8.2) | 14.5 (7.8) | 0.483 |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale | 14.9 (11.3) | 15.6 (11.4) | 15.1 (11.8) | 0.795 |

| Pain Self-Efficacy | 38.0 (12.7) | 35.2 (13.2) | 32.7 (12.7) | <0.001 |

| Fear Avoidance Physical Activity | 13.5 (5.5) | 14.7 (5.8) | 14.6 (5.7) | 0.050 |

Trends in prior-year healthcare utilization data are presented in Table 3. There was a significant increasing trend in frequency of past-year primary care visits across the three dose groups (mean number of visits was 3.1 for Low Dose, 3.4 for Moderate Dose, and 4.1 for the High Dose groups). Those in the Higher Dose Group were also significantly more likely to have a past-year visit in the emergency room (34.4%) compared with patients in the Low Dose (24.1%) or Moderate Dose (26.8%) and in a specialty pain clinic (13.3% for Higher Dose group) compared with participants in the Low Dose (5.0%) or Moderate Dose (8.4%) groups. There was no significant trend among groups in likelihood of having a past-year visit in mental health, rehabilitation medicine, inpatient medicine, surgery, or substance abuse treatment (all p-values > 0.05).

Table 3.

Comparison of past-year healthcare utilization data based on prescription opioid dose.

| Low Dose Group (5 – 20 mg MED) n=199 |

Moderate Dose Group (20.1 – 50 mg MED) n=190 |

Higher Dose Group (50.1 – 120 mg MED) n=128 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Primary Care visits | 3.1 (2.0) | 3.4 (2.5) | 4.1 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Emergency Room visit | 24.1% | 26.8% | 34.4% | 0.050 |

| Specialty Pain Clinic visit | 5.0% | 8.4% | 13.3% | 0.009 |

| Mental Health visit | 25.1% | 24.2% | 32.8% | 0.165 |

| Rehabilitation Medicine visit | 22.1% | 30.0% | 21.9% | 0.824 |

| Inpatient Medical stay | 9.6% | 14.2% | 10.2% | 0.710 |

| Surgical visit | 19.1% | 17.9% | 17.2% | 0.653 |

| Substance Abuse Treatment | 2.5% | 0.5% | 2.3% | 0.743 |

Discussion

Findings from the present study are consistent with other research describing general clinical problems among patients who are prescribed LTOT.9 Overall, participants had high rates of comorbid psychopathology and problems with co-occurring alcohol and substance use. In addition, we conducted analyses of differences in demographic and clinical factors based on current prescription opioid dose, and found that as the dose of opioids increase, there is a significant trend towards higher scores of pain intensity (in quadratic pattern), greater pain-related disability, poorer physical functioning, lower self-efficacy for managing pain, and greater fear avoidance beliefs about physical activity (in quadratic pattern). Estimates of effect size suggest moderate differences among groups on these variables.

Consistent with prior research, the rates of past-year depressive disorder diagnoses, based on data from the EMR, were more common in the Higher Dose group.27,33 However, there were no significant differences in our study among groups on self-report measures of depression or anxiety severity. There are several factors that may account for differences between our findings and other research. The prior studies were conducted using data from 200427 and 2008,33 during an era with fewer constraints on opioid prescribing practices. In prior studies “High Dose” was classified as more than 100 mg MED27 or 180 mg MED,33 whereas the current study classified participants in the Higher Dose group if they had more than 50 mg MED, and participants were excluded from this study if their baseline MED was greater than 120 mg MED. Differences between current and prior findings may be due to secular changes in prescribing practices as new data on prescription opioids have emerged11 and clinicians have received updated guidelines for managing chronic pain.10,13,14 This study also compared differences among groups based on prescription opioid dose using well-validated and commonly utilized assessment measures (as opposed to extracting data from the EMR), which may have contributed to differences in research findings.

Co-occurring use of alcohol and illicit substances is a significant issue among patients prescribed LTOT, though this topic has not been well-studied and there remain many unanswered questions.34,48 In this study, there were inconsistent findings based on the method for assessing alcohol or substance use disorder. Data from the EMR suggested significant differences among groups in rates of diagnosed substance use disorders (with participants in the Higher Dose group having the highest rates), but no differences in rates of alcohol use disorders. However, based on self-report data patients in the Low Dose Group had the lowest rates of self-reported potential substance use disorder to a non-prescribed or illicit substance, yet the highest rates of potential alcohol use disorder. Conversely, patients in the Higher Dose group had the highest rates of self-reported potential substance use disorder and lowest rates of problematic alcohol use. This lack of consistency suggests different results based on the method of assessment and that there should be caution when drawing conclusions about alcohol and substance use disorder based on prescription opioid dose.

Patients prescribed higher doses may have lower rates of potential alcohol use disorder due to increasingly receiving reminders to avoid combining alcohol and prescription opioids.5 Higher rates of potential substance use disorder may be due to patients prescribed higher doses of opioids seeking alternative or adjunctive strategies for pain relief, such as marijuana, which may be viewed by participants as safer than other potential adjuncts.2,31 Unfortunately, the self-report measure of potential substance use disorder used in this study (the DAST-10) does not permit examination of use of specific substances. Additional data are needed to understand the clinical outcomes of combining prescription opioid medications with other non-prescribed or illicit substances, though prior research suggests that patients with a history of substance use disorder are less likely to have clinically significant gains in pain treatment.32

In this study, self-efficacy for managing pain was lowest among patients who were prescribed the highest doses of opioids. This suggests that patients who are prescribed higher doses of opioids have poorer expectations and confidence in their ability to perform tasks due to their pain.36 We also found a significant trend for fear avoidance beliefs about physical activity. As patients were prescribed higher doses of opioids, they were more likely to have negative thoughts about the potential impact of physical activity on pain and function. However, contrary to our hypotheses, there was not a significant trend for pain catastrophizing. Prior research demonstrates that pain self-efficacy, fear avoidance beliefs, and pain catastrophizing are robust predictors of treatment outcome.24,26,37,46 The results from our larger prospective cohort analysis will examine the extent to which these variables are predictive of, and able to identify outcomes following, prescription opioid dose escalation.

There are several limitations in the present data, which should be considered when interpreting the results. As described, the present results are cross-sectional, thereby limiting causal inference; however, this group is being followed prospectively, which will permit examination of associations over time. The present results do not address the clinical effectiveness or outcomes of prescription opioid medications. Additionally, cross-sectional studies may be prone to non-responder bias when enrolled participants differ from those who are eligible and invited to participate but do not enroll; compared with patients who were invited to participate in this study but did not enroll, participants who enrolled were older, more likely to be male, and more likely to report minority racial/ethnic status. These differences constrain the generalizability of our findings. Finally, we identified a seemingly unexpected finding, as patients in the Higher Dose group had the lowest rates of self-reported problematic alcohol use, yet the highest rates of self-reported problematic substance use. Further, these findings from self-report screening measures were not uniformly consistent with diagnostic data extracted from the EMR, suggesting potential concern about how potential alcohol and substance use disorders are assessed in this patient population. Future research is needed to better understand the interrelationships among pain, prescription opioid use, and alcohol and substance use disorders.

This study identified a cohort of patients already prescribed a stable dose of LTOT and identified a significant trend for poorer patient-reported pain outcomes based on higher prescription opioid doses. We also identified a statistically significant increasing trend toward more healthcare utilization as prescription opioid doses increase, including differences among groups in number of past-year visits to primary care, and whether patients were seen in the emergency room or specialty pain clinic. In contrast with prior research,27,33 those patients who were prescribed the highest doses of opioids did not differ on severity of depressive or anxiety symptoms, though differences in research methods may have contributed to the contrasting findings. Participants in the Higher Dose group had the lowest rates of self-reported problematic alcohol use, yet the highest rates of self-reported problematic substance use. Long-term follow-up from this cohort will permit examination of the impact of these variables on clinical outcomes.

Highlights.

We compared group differences based on prescription opioid dose.

Higher prescription opioid dose was associated with poorer levels of patient-reported pain outcomes and higher health care utilization.

Differences exist between groups in rates of self-reported alcohol and substance use disorders.

Perspective.

This study included 517 patients who were prescribed long-term opioid therapy and compared differences on pain and mental health-related variables based on prescription opioid dose. Findings reveal small to medium-sized differences on pain-related variables, alcohol and substance use, and healthcare utilization based on the dose of opioid prescribed.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by grant 034083 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. The work was also supported by resources from the VA Health Services Research and Development-funded Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care at the VA Portland Health Care System (CIN 13-404). Drs. Yarborough, Perrin, and Green have received grant support from Purdue Pharma LP, and the Industry PMR Consortium, a consortium of 10 companies working together to conduct FDA-required post-marketing studies that assess known risks related to extended-release, long-acting opioid analgesics. No other author reports having any potential conflict of interest with this study. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institute on Drug Abuse

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adams LL, Gatchel RJ, Robinson RC, Polatin P, Gajaraj N, Deschner M, Noe C. Development of a self-report screening instrument for assessing potential opioid medication misuse in chronic pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:440–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachhuber MA, Saloner B, Cunningham CO, Barry CL. Medical cannabis laws and opioid analgesic overdose mortality in the United States, 1999–2010. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174:1668–1673. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1943–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker WC, Gordon K, Edelman J, Kerns RD, Crystal S, Dziura JD, Fiellin LE, Gordon AJ, Goulet JL, Justice AC, Fiellin DA. Trends in any and high-dose opioid analgesic receipt among aging patients with and without HIV. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:679–686. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohnert AS, Bonar EE, Cunningham R, Greenwald MK, Thomas L, Chermack S, Blow FC, Walton M. A pilot randomized clinical trial of an intervention to reduce overdose risk behaviors among emergency department patients at risk for prescription opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohnert ASB, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, Ilgen MA, Blow FC. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315–1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MY, Edlund MJ, Martin BC, DeVries A, Sullivan MD. Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Int Med. 2010;170:1425–1432. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonnel MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C) Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell G, Nielsen S, Bruno R, Lintzeris N, Cohen M, Hall W, Larance B, Mattick RP, Degenhardt L. The Pain and Opioids in Treatment (POINT) study: Characteristics of a cohort using opioids to manage chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2015;156:231–242. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460303.63948.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Adler JA, Ballantyne JC, Davies P, Donovan MI, Fishbain DA, Foley KM, Fudin J, Passik SD, Pasternak GW, Portenoy RK, Rich BA, Roberts RG, Todd KH, Miaskowski Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Deyo RA. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: A systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:276–286. doi: 10.7326/M14-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cocco KM, Carey KB. Psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in psychiatric outpatients. Psychol Assess. 1998;10:408–414. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. [Accessed 4/1/11];VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. 2010 http://www.healthquality.va.gov/Chronic_Opioid_Therapy_COT.asp.

- 14.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescription opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowling LS, Gatchel RJ, Adams LL, Stowell AW, Bernstein D. An evaluation of the predictive validity of the Pain Medication Questionnaire with a heterogeneous group of patients with chronic pain. J Opioid Manag. 2007;3:257–266. doi: 10.5055/jom.2007.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Sullivan MD, Weisner CM, Silverberg MJ, Campbell CI, Psaty BM, Von Korff M. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:85–92. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris KM, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott AM, Smith BH, Smith WC, Chambers WA. Changes in chronic pain severity over time: The Chronic Pain Grade as a valid measure. Pain. 2000;88:303–308. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furlan AD, Sandoval JA, Mailis-Gagnon A, Tunks E. Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: A meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effects. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;174:1589–1594. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Less is more: Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:686–691. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater Persistent pain and well being: A World Health Organization study in primary care. JAMA. 1998;280:145–151. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henry SG, Wilsey BL, Melnikow J, Iosif AM. Dose escalation during the first year of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. Pain Med. 2015;16:733–744. doi: 10.1111/pme.12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes CP, Gatchel RJ, Adams LL, Stowell AW, Hatten A, Noe C, Lou L. An opioid screening instrument: Long-term evaluation of the utility of the Pain Medication Questionnaire. Pain Pract. 2006;6:74–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. Changes in beliefs, catastrophizing, and coping are associated with improvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:655–662. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: Systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain. 2004;112:372–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keefe FJ, Rumble ME, Scipio CD, Giordano LA, Perri LM. Psychological aspects of persistent pain: Current state of the science. J Pain. 2004;5:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobus AM, Smith DH, Morasco BJ, Johnson ES, Yang X, Petrik AF, Deyo RA. Correlates of high-dose opioid medication use for low back pain in primary care. J Pain. 2012;13:1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Int Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Annals. 2002;32:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas P. Cannabis as an adjunct to or substitute for opiates in the treatment of chronic pain. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2012;44:125–133. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2012.684624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morasco BJ, Corson K, Turk DC, Dobscha SK. Association between substance use disorder status and pain-related function following 12 months of treatment in primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain. J Pain. 2011;12:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Carr TP, Deyo RA, Dobscha SK. Clinical characteristics of veterans prescribed high doses of opioid medications for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2010;151:625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morasco BJ, Gritzner S, Lewis L, Oldham R, Turk DC, Dobscha SK. Systematic review of prevalence, correlates, and treatment outcomes for chronic non-cancer pain in patients with comorbid substance use disorder. Pain. 2011;152:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosher HJ, Krebs EE, Carrel M, Kaboli PJ, Weg MW, Lund BC. Trends in prevalent and incident opioid receipt: An observational study in Veterans Health Administration 2004–2012. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:597–604. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3143-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholas MK. The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: Taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norton PJ, Asmundson GJG. Amending the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: What is the role of physiological arousal? Behav Therapy. 2003;34:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Portenoy RK, Farrar JT, Backonja M, Cleeland CS, Yang K, Friedman M, Colucci SV, Richards P. Long-term use of controlled-release oxycodone for noncancer pain: Results of a 3-year registry study. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:287–299. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31802b582f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saunders KW, Dunn KM, Merrill JO, Sullivan M, Weisner C, Braden JB, Psaty BM, Von Korff M. Relationship of opioid use and dosage levels to fractures in older chronic pain patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:310–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawilowsky S. New effect size rules of thumb. J Mod Appl Stat Methods. 2009;8:467–474. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skinner HA. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith BH, Penny KI, Purves AM, Munro C, Wilson B, Grimshaw J, Chambers WA, Smith WC. The Chronic Pain Grade questionnaire: Validation and reliability in postal research. Pain. 1997;71:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)03347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Lee J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1968–1978. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner JA, Holtzman S, Manci L. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2007;127:276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Von Korff M, Saunders K, Ray G, Boudreau D, Campbell C, Merrill J, Sullivan M, Rutter C, Silverberg M, Banta-Green C, Weisner C. De facto long-term opioid therapy for non-cancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:521–527. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318169d03b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, van der Goes DN. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: A systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156:569–576. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52:157–168. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]