Abstract

Tulsi, also known as holy basil, is indigenous to the Indian continent and highly revered for its medicinal uses within the Ayurvedic and Siddha medical systems. Many in vitro, animal and human studies attest to tulsi having multiple therapeutic actions including adaptogenic, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, and immunomodulatory effects, yet to date there are no systematic reviews of human research on tulsi's clinical efficacy and safety. We conducted a comprehensive literature review of human studies that reported on a clinical outcome after ingestion of tulsi. We searched for studies published in books, theses, conference proceedings, and electronic databases including Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, Embase, Medline, PubMed, Science Direct, and Indian Medical databases. A total of 24 studies were identified that reported therapeutic effects on metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease, immunity, and neurocognition. All studies reported favourable clinical outcomes with no studies reporting any significant adverse events. The reviewed studies reinforce traditional uses and suggest tulsi is an effective treatment for lifestyle-related chronic diseases including diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and psychological stress. Further studies are required to explore mechanisms of action, clarify the dosage and dose form, and determine the populations most likely to benefit from tulsi's therapeutic effects.

1. Introduction

Tulsi in Hindi or Tulasi in Sanskrit (holy basil in English) is a highly revered culinary and medicinal aromatic herb from the family Lamiaceae that is indigenous to the Indian subcontinent and been used within Ayurvedic medicine more than 3000 years. In the Ayurveda system tulsi is often referred to as an “Elixir of Life” for its healing powers and has been known to treat many different common health conditions. In the Indian Materia Medica tulsi leaf extracts are described for treatment of bronchitis, rheumatism, and pyrexia [1]. Other reported therapeutic uses include treatment of epilepsy, asthma or dyspnea, hiccups, cough, skin and haematological diseases, parasitic infections, neuralgia, headache, wounds, and inflammation [2] and oral conditions [3]. The juice of the leaves has been applied as a drop for earache [4], while the tea infusion has been used for treatment of gastric and hepatic disorders [5]. The roots and stems were also traditionally used to treat mosquito and snake bites and for malaria [5].

Three types of tulsi are commonly described. Ocimum tenuiflorum (or Ocimum sanctum L.) includes 2 botanically and phytochemically distinct cultivars that include Rama or Sri tulsi (green leaves) and Krishna or Shyama tulsi (purplish leaves) [6, 7], while Ocimum gratissimum is a third type of tulsi known as Vana or wild/forest tulsi (dark green leaves) [8, 9]. The different tulsi types exhibit vast diversity in morphology and phytochemical composition including secondary metabolites, yet they can be distinguished from other Ocimum species by the colour of their yellow pollen, high levels of eugenol [10], and smaller chromosome number [11]. Despite being distinct species with Ocimum tenuiflorum having six times less DNA than Ocimum gratissimum [11], they are traditionally used in the same way to treat similar ailments [5]. For consistency, this review uses the term tulsi to refer to both Ocimum tenuiflorum or Ocimum gratissimum.

Tulsi has been the subject of numerous scientific studies and its pharmacological and wide range of therapeutic applications are the subject of more than one hundred publications during the last decade alone. Numerous in vitro and animal studies attest to tulsi leaf having potent pharmacological actions that include adaptogenic [12–14], metabolic [15–17], immunomodulatory [18–20], anticancer [21–23], anti-inflammatory [24, 25], antioxidant [26, 27], hepatoprotective [28, 29], radioprotective [30, 31], antimicrobial [32–35], and antidiabetic effects [36–38] that have been extensively reviewed previously [39–45].

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that tulsi increases swimming survival times in mice and prevents stress-induced ulcers in rats [46] with antistress effects comparable to antidepressant drugs [47]. Similarly, recent studies report leaf extracts from ethanolic and aqueous tulsi protects rats from stress-induced cardiovascular changes [48, 49]. Studies in animal models have further shown that the leaf extract of tulsi possesses anticonvulsant and anxiolytic activities [50, 51]. Several animal studies conducted over the past fifty years report that ingestion of tulsi leaves improves both glucose and lipid profiles in normal and diabetic-induced animal models [36, 38, 52–58]. Tulsi aqueous leaf extract intramammary infusion has also showed promising effect on improving the immune response in bovine models [59].

In addition to the extensive literature documenting in vitro and animal research, studies on the use of tulsi as part of a polyherbal formulation in humans has been systematically reviewed [60]. To date, however, there are no systematic reviews on the clinical efficacy and safety of tulsi as a single herbal intervention in humans. The objective of this review was therefore to summarize and critically appraise human clinical trials of tulsi in order to assess the current evidence on tulsi's clinical efficacy and safety.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Search Strategies

Relevant clinical studies were identified through searching PubMed, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Indian Medical databases. The terms in the title or abstract (MeSH and free search terms) alone or in combination searched were “Tulsi”, “Tulasi”, “Holy Basil”, “ocimum sanctum”, “Ocimum tenuiflorum”, “Ocimum gratissimum”, “ocimum”, “Albahaca Morada” or combined with “clinical trial”, “clinical”, or “human”.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they reported on a human intervention study that involved ingestion of any form of tulsi or holy basil (Ocimum sanctum or Ocimum tenuiflorum or Ocimum gratissimum) and at least one clinical outcome.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they were reviews, were nonclinical studies, did not involve human subjects, did not report a biological outcome, only involved topical application or only used tulsi at part of a polyherbal formulation, and did not report on the use of tulsi as a single herbal intervention.

2.4. Study Selection

All the titles and abstracts were screened on the basis of the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. The full text of each article was reviewed to assess suitability of the study with duplications removed. The search included clinical studies written in the English language and articles from inception until November 2016 in the above-mentioned electronic databases. The references of selected articles were manually searched to identify further relevant studies and, where appropriate, study authors were contacted to request further information.

2.5. Quality Assessment

In order to evaluate the quality of design and implementation of trials, information was collected on the study design, randomization, blinding, and description of participant dropouts and the Jadad scale was used to assess methodological quality [84].

2.6. Data Extraction

Eligible studies were reviewed with the following data extracted and tabulated: (1) first author name and year of publication; (2) design of the study; (3) Jadad score; (4) study participants (intervention and control groups); (5) extraction method; (6) duration of intervention; (7) tulsi dose and dose form (8) comparator; (9) outcome measure(s) including both primary and secondary, and (10) any adverse event(s).

3. Results

3.1. Study Description

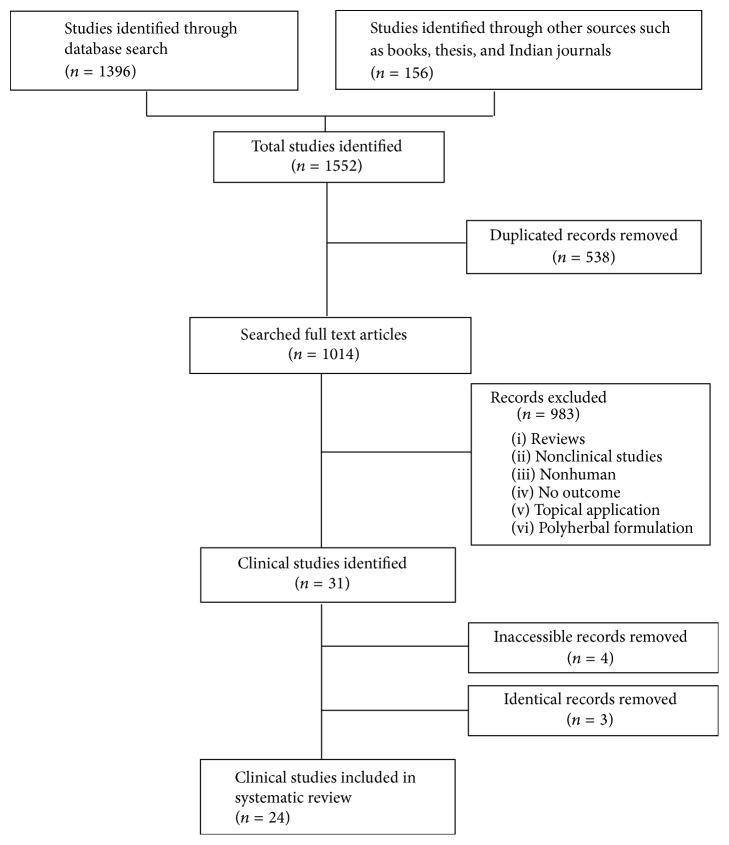

After screening 1553 studies, a total of 31 articles on tulsi met the inclusion criteria. Four articles were excluded due to being inaccessible and one article reported two independent clinical studies, while one clinical trial was reported in three separate articles. This left a total of 24 independent clinical studies to be reviewed. A flow chart of the systematic search and study selection protocol is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of systematic search and study selection protocol.

The reviewed studies involved a total of 1111 participants with ages ranging from 10 to 80 years old with eight clinical trials limiting participants to ≥40 years old [38, 61, 66, 68–70, 72, 75]. Only three clinical trials included 100 or more participants [65, 66, 82]. The study durations ranged from 2 to 13 weeks and tulsi dosage and frequency varied from 300 mg to 3000 mg given as 1–3 times per day as tulsi leaf aqueous extract; 300 mg–1000 mg once or twice per day as tulsi leaf ethanolic extract; 6 g to 14 g per day as the tulsi whole plant aqueous extract; and 10 g fresh tulsi leaf aqueous extract administered as once or four equal doses daily, and as tincture solution 30 drops a day were administered as three equal doses daily.

From the 24 studies identified only eight included a placebo [66, 68, 70, 75–77, 81, 82]. Five of the included trials adopted a two-arm parallel design [62, 63, 65, 67, 80], while four used a cross-over design with one being described in three different papers that reported on two different sets of outcomes [70, 75, 77].

Included studies were classified according to three major clinical domains: metabolic related disorders; immunity; and neurocognitive function (Tables 1, 2, and 3). Only two studies described the type of tulsi (Krishna) used while all other papers referred to tulsi as Ocimum sanctum [71, 72] not distinguishing between cultivars. Four studies reported on the use of tulsi alone and along with food, hypoglycemic drug, curry or Neem [63, 67, 69, 76]. Most studies looked at clinical populations with specific acute or chronic illnesses, such as viral infection, psychological stress, diabetes, or metabolic syndrome, with only three studies reporting on the effects of tulsi in healthy human participants [74, 76, 81].

Table 1.

Effect of tulsi on metabolic related-disorders in human clinical trials.

| Clinical domain |

Authors (year) |

Study design | Jadad score |

Participants∗∗ (age range) | Tulsi extract |

Intervention | Comparator | Outcome measure(s) |

Adverse events (s) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration∗ | Dosage | |||||||||

| Metabolic disorders | Gandhi et al. (2016) [61] | Randomized controlled clinical trial |

1 | 40 male adults T2DM (45–55 years) |

Tulsi leaves caps |

6.5 weeks | 3 g/day before meal |

Not disclosed |

Significant↓ postprandial glucose & fasting blood glucose |

Not reported |

| Satapathy et al. (2016) [62] | Randomized parallel group clinical trial |

3 | 30 adults Obesity (17–30 years) |

Tulasi1 leaves caps |

8 weeks | 250 mg/day 2x daily before meal |

Parallel group no intervention |

Improved BMI, lipid profile (except TC), TG & IR |

Mild nausea |

|

| Venkatesan and Sengupta (2015) [63] | Clinical trial controlled parallel group |

0 | 30 adults T2DM |

Tulsi powder leaves |

2 weeks | 2 g/day | Curry leaves tulsi + curry |

Significant↓ post-prandial glucose & fasting blood |

Not reported |

|

| Srinivasa Prasadacharyulu (2014) [64] | Clinical study case report |

0 | 3 adults T2DM |

Fresh tulsi leaves |

5 weeks | fresh leaves3 3x daily |

None | Considerable decrease in blood glucose reaching near normal levels |

None | |

| Ahmad et al. (2013) [65] | Randomized single-blind parallel group |

2 | 200 adults Gouty Arthritis |

Tincture2 from tulsi |

12 weeks | 10 drops 3 times/day |

Tincture wild rosemary 10 drops × 3/day |

Significant reduction in serum uric acid |

Not reported |

|

| Devra et al. (2012) [66] | Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial |

1 | 100 adults MetS (≥40 years) |

Aqueous tulsi Leaves |

12 weeks | 5 mL/×2 day before meals |

Not disclosed |

Improved lipid profile, fasting blood glucose, and BP |

Not reported |

|

| Somasundaram et al. (2012) [67] | Randomized, controlled parallel clinical Trial |

1 | 60 adults T2DM (30–65 years) |

Tulsi leaves + glibenclamide drug |

13 weeks | 300 mg/day tulsi + 5 mg Glibenclamide |

5 mg/day glibenclamide |

Significant ↓fasting blood & postprandial glucose reduced HBA1c |

None | |

| Dineshkumar et al. (2010) [68] | Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial |

3 | 40 adults T2DM (45–55 years) |

Aqueous tulsi leaves |

8 weeks | 500 g/day | Water | Significant improvement in lipid profile |

None | |

| Kochhar et al. (2009) [69] | Randomized, clinical trial |

1 | 90 male adults T2DM/MetS (40–60 years) |

Powder tulsi leaves |

12 weeks | 2 g/day | Neem neem + tulsi |

Improved T2DM symptoms: ↓polydipsia, ↓polyphagia, & BP |

Not reported |

|

| Rai et al. (1997) [38] | Clinical trial controlled group |

1 | 27 adults T2DM/MeS (45–65 years) |

Tulsi powder leaves |

4 weeks | 1 g/day in morning before meal |

None | Improved lipid profile, blood glucose, glycated proteins (HbA1c) & UA |

Not reported |

|

| Agrawal et al. (1996) [70] | Randomized, single-blind, Placebo-controlled cross-over |

1 | 40 adults T2DM (41–65 years) |

Tulsi powder leaves |

5 weeks (+5-day wash out) |

2.5 g/day in morning before meal |

Spinach powder leaves 2.5 g/day |

Significant ↓fasting blood glucose, post-prandial glucose and urine glucose |

None | |

| Luthy (1964) [71] | Clinical trial | 1 | 10 adults T2DM |

Whole plant decoction |

12 weeks | 14 g/day | None | Reduced blood glucose in 9 T2DM adults |

None | |

| Verma et al. (2012) [72] | Clinical trial | 0 | 5 adults psychosomatic (60–80 years) |

Powder whole plant tulsi |

12 weeks | 3 g × 2/day | None | Significant improvement in lipid profile |

None | |

| Bhargava et al., (2013) [73] | Clinical study open label |

1 | 50 Female adults hypotensive (18–30 years) |

Fresh juice 15 tulsi leaves |

4 weeks | Juice × 2/day | None | Significant changes, in Blood pressure |

Not reported |

|

| Mondal et al. (2012) [74] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over leaves |

5 | 22 healthy adults (22–37 years) |

Ethanolic tulsi |

4 weeks (+3-week wash-out) |

300 mg/day before food |

300 mg/day sucrose |

Reduction in lipid profile, in 6 participants |

None | |

| Sarvaiya (1986) [75] | Randomized placebo controlled cross-over |

1 | 20 adults, hypertension (45–64 years) |

Fresh Juice 75% tulsi |

10 days (+5-day wash-out) |

30 mL/day | Green colored water 30 mL/day before meal |

Significant ↓blood pressure | None | |

| Sarvaiya (1986) [75] | Randomized placebo-controlled |

1 | 16 adults, hypertension (45–64 years) |

Fresh Juice 75% tulsi |

12 days | 30 mL 2 times a day before meals |

Green-colored water 30 mL × 2/day |

Significant ↓blood pressure (lowered by 25%) |

None | |

BMI = body mass index measured by weight (kg)/height (m2); BP = blood pressure; HbA1C = glycosylated haemoglobin; IR = insulin resistance; MetS = metabolic syndrome; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus; TC = total cholesterol, TG = triglycerides; UA = uric acid.

∗ Intervention duration is the time the intervention was administered excluding any washout periods.

∗∗ Participants who completed the study are listed excluding any drop-outs.

1 Tulasi Tablets are product of Himalaya Herbal Healthcare Pharmaceutical Company in India.

2Tincture is a product of BM private limited.

3The quantity of tulsi fresh leaves was not specified; “handful” of leaves was given to each patient.

Table 2.

Effect of tulsi on immune system and viral infections in human clinical trials.

| Clinical domain |

Authors (year) |

Study design | Jadad score |

Participants∗∗ (age range) | Tulsi extract |

Intervention | Comparator | Outcome measure(s) |

Adverse events (s) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration∗ | Dosage | |||||||||

| Immunomodulation | Venu Prasad (2014) [76] | Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial |

3 | 30 healthy adults (18–30 years) |

Ethanolic tulsi leaves in Bar‡ |

2 weeks | 1 bar × 2/day (1000 mg tulsi) |

Not described “control bar” |

↑physical performance ↓fatigue and CK levels less increase in lactic acid |

None |

| Mondal† et al. (2011) [77] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over |

5 | 22 healthy adults (22–37 years) |

Ethanolic tulsi leaves |

4 weeks (+3 weeks wash out) |

300 mg/day | Cellulose 300 mg/day |

Increased cytokine level, interferon-ϒ, & interleukin-4 |

None | |

| Sharma (1983) [78] | Open clinical trial | 1 | 20 adults, asthma |

Aqueous tulsi leaves tablets |

1 week | 500 mg × 3/day | None | Relief within 3 days, improved vital capacity |

None | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Viral infections | Rajalakshmi et al. (1986) [79] | Clinical trial | 0 | 20 cases, viral hepatitis (10–60 years) |

Aqueous extract fresh tulsi leaves |

2 weeks for mild cases 3 weeks for Severe cases |

10 g daily | None | Symptoms all improved within 2 weeks |

None |

| Das et al. (1983) [80] | Randomized clinical trial parallel-controlled |

1 | 14 adults, viral encephalitis |

Aqueous extract fresh tulsi leaves |

4 weeks | 2.5 g 4 times/day |

12 mg/day dexamethasone treated group |

Increased survival rate compared to steroid |

Not reported |

|

CK = creatine kinase; TPE = tropical pulmonary eosinophilia.

∗ Intervention duration included wash-out periods where applicable until study was completed.

∗∗ Participants include both control and intervention groups completing the study and excluded any drop-outs.

†Same results as previously published (Mondal et al., 2010).

‡Tulsi enriched bar: each 25 g bar contained oats, resin, peanuts, skimmed milk powder, sugar, and honey and 0.5% ethanolic tulsi.

Table 3.

Therapeutic effects of tulsi on cognitive function, mood, and stress in human clinical trials.

| Clinical domain |

Authors (year) |

Study design | Jadad score |

Participants∗∗ (age range) | Tulsi extract |

Intervention | Comparator | Outcome measure(s) |

Adverse events (s) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration∗ | Dosage | |||||||||

| Neurocognition | Sampath et al. (2015) [81] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial |

5 | 40 healthy adults (18–30 years) |

Ethanolic tulsi leaves capsules |

4 weeks | 300 mg/day before meals |

Cellulose capsules |

Cognitive flexibility, attention, Improved working memory only after day 15 |

None |

| Saxena et al. (2012) [82] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled |

4 | 150 adults, stress (18–65 years) |

OCIBEST† whole plant capsules |

6 weeks | 400 mg 3 times/day after meals |

Cellulose capsules |

Reduction in stress related symptoms: fatigue, sleep and sexual problems |

None | |

| Verma‡ et al. (2012) [72] | Clinical trial | 0 | 24 adults, psychosomatic (60–80 years) |

powder whole plant tulsi |

12 weeks | 3 g × 2/day | None | Reduced anxiety significantly lowered biological age score |

None | |

| Bhattacharyya et al. (2008) [83] | Clinical trial | 1 | 35 adults with GAD (18–60 years) |

Ethanolic tulsi leaves capsules |

8 weeks | 500 mg 2x daily after meals |

None | Self-reported questionnaire, ↓anxiety, stress, & depression |

None | |

GAD = generalized anxiety disorder.

∗ Intervention duration is the time the intervention was administered excluding any washout periods.

∗∗ Participants include both control and intervention groups completing the study and excluded any drop-outs.

† OCIBEST is product of natural remedies and contains tulsi whole plant.

‡Authors also reported findings from glucose and lipid profile for 5 of the participants and found lipid profile significantly improved.

3.2. Effectiveness and Safety Evaluation

The most common outcome measurements were related to blood glucose levels (8 studies), lipid profile (6 studies), blood pressure (6 studies), immune response (6 studies), and neurocognitive changes (4 studies). Other outcomes included mood (3 studies), fatigue (2 studies), uric acid levels (2 studies), diabetes secondary symptoms (1 study), and sleep (1 study). Fifteen of the 24 included studies reported no adverse events and eight studies did not describe or refer to any adverse events. Only one study that used tulsi leaf extract as 250 mg capsule taken before meals twice daily in 16 obese adults reported the occurrence of occasional nausea.

3.3. Quality Assessment

The studies were classified as either Randomized Clinical Trial Placebo Controlled (RCT-PC 6), Randomized Clinical Trials with no placebo (RCT 7), or Clinical Trials where no information on randomization or control was available (CT 6). Only three out of 24 studies, two of which examined neurocognitive effects [81, 82] and one reported on immunity as well as cardiovascular changes [74, 77], were rated as high quality with Jadad scores of 4-5 points, with the remaining studies varying in quality with Jadad scores ranging from 0 to 3 points. The score for each included study is presented in Tables 1–3.

3.4. Metabolic Disorders

Seventeen clinical trials reported on metabolic conditions with ten studies reporting on type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome with measures of blood glucose, lipids, and blood pressure, yet only one study reported on the clinical symptoms associated with type 2 diabetes such as polydipsia, polyphagia, polyuria, sweating, fatigue, burning feet, itching, and headache [69]. In addition one study reported on obesity [62] and two studies on uric acid changes in participants with gouty arthritis [38, 65].

Six of the identified trials on metabolic conditions were randomized clinical trials with placebo controls [66, 68, 70, 74, 75]. In addition, eight studies were of 2–5 weeks duration [38, 63, 64, 70, 73–75], three were of 6–8 weeks [61, 62, 68], and six were of 12-13 weeks [65–67, 69, 71, 72]. When the duration of the tulsi intervention was increased from 4-5 weeks [38, 70] to 12-13 weeks there was a more dramatic reduction in fasting blood glucose (FBG) and postprandial glucose (PPG) compared to controls [66, 67]. In particular, HbA1c (35.8%) significantly decreased when tulsi was added as adjunct therapy to hypoglycemic medication compared to drug medication alone [67].

The earliest clinical trial conducted in 1964 with 10 patients with type 2 diabetes reported that over a period of 12 weeks, a 14 g decoction of whole Krishna tulsi plant led to a gradual improvement in fasting blood glucose in 9 out of 10 patients [71]. Three decades later, the first randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial reported daily ingestion of 2.5 g of tulsi leaves led to significant improvements of FBG, PPG, and urine glucose in type 2 diabetes patients after 4 weeks [70]. In addition, Rai et al. reported that 4 weeks of supplementation with tulsi powder significantly lowered blood glucose and glycated proteins, reduced uric acid levels, and improved lipid profiles in participants with type 2 diabetes [38]. In comparable trials with longer durations, FBG and PPG improved by 1.2–2.2 and 1.5–6.0 folds, respectively, while HbA1c improved 1.5 and 3.2 fold after 12-13 weeks [66, 67]. Similarly, lipid profile was improved significantly in MetS and diabetes participants in three clinical trials [38, 66, 68] with a separate clinical trial reporting significant improvement in lipid profile in obese participants [62] and a further study reporting improved lipid levels in healthy subjects [74].

A further 12-week study of type 2 diabetes patients reported greater improvement in both blood glucose and HbAc1 levels when 300 mg of tulsi leaf extract was administered along with the antidiabetic drug glibenclamide, compared to drug treatment alone [67]. Similarly, a controlled trial of patients with diabetes found that consumption of 2 g of tulsi powdered leaves, either alone or combined with curry leaves, led to significant improvement in blood sugars after two weeks [63]. In a further 12-week randomized trial in diabetic patients, 2 g of tulsi leaf extract alone or combined with neem leaf extract produced marked reduction in diabetic symptoms with greatest effect noted for the combination [69].

Six trials reported on the effect of tulsi on individual features of metabolic syndrome [62, 72–75]. Two studies reported significant improvement of blood pressure in hypertensive participants given 30 mL of fresh tulsi leaf juice once daily or 30 mL twice a day for 10 and 12 days, respectively [75], with a further study reporting normalisation of blood pressure in hypotensive adult females [73]. Yet another study reported improvement in serum lipids with no difference in blood pressure in healthy adults administered 300 mg per day of tulsi leaf ethanolic extract for 4 weeks [74]. A further study reported improved lipid profiles in older adults (60–80 years) with psychosomatic symptoms after administration of 3 g of whole plant tulsi extract twice daily for 12 weeks [72]. A more recent study also reported improvement in lipid profiles, as well as BMI of obese participants administered 250 mg capsules of tulsi leaf extract twice daily for 8 weeks [62].

3.5. Immunomodulation and Inflammation

Enhanced immune response was reported in five clinical studies [76–80]. A small randomized double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial found increased immune response with increased Natural Killer (NK) and T-helper cells in healthy adult participants compared to placebo volunteers after 4 weeks of 300 mg or ethanolic tulsi leaf extract daily taken before food [77]. Another 2-week controlled randomized study in which young adult volunteers were provided with nutrition bars fortified with 1 g of ethanolic tulsi leaf extract found that compared to control participants, the intervention group had significantly improved VO2 max, less fatigue, reduced Creatine Kinase, and improved immune response to viral infection as indicated by reduced load of human herpesvirus 6 in saliva [76].

Two clinical trials studied the effect of daily administration of 10 g of an aqueous extract of fresh tulsi leaves in patients with acute viral infections, with a study on patients with acute viral encephalitis reporting increased survival after 4 weeks in the tulsi group compared to a group given dexamethasone and a study on viral hepatitis reporting symptomatic improvement after 2 weeks [79, 80]. A further study of asthmatic patients found that 500 mg of dried tulsi leaves taken three times daily improved vital capacity and provided relief of asthmatic symptoms within 3 days [78].

3.6. Neurocognitive Effect

The four studies that reported on neurocognitive effects all showed significant improvements in mood and/or cognitive function regardless of age, gender, formulation, dose, or quality of the study [72, 81–83]. Cognition function was assessed in a randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial that demonstrated an improvement in cognitive flexibility, short-term memory, and attention in 40 healthy young adults (17–30 years) following treatment with 300 mg daily tulsi for 4 weeks [81]. However, the cognitive effects of tulsi were only significant after the first two weeks compared to the placebo, with no significant difference found in stress levels. This is in contrast to three clinical studies that reported significant reduction in anxiety and stress levels with higher doses of tulsi given over a longer time period [72, 82, 83]. The positive effect of tulsi on mood was demonstrated in three studies, with two studies reporting reductions of 31.6%–39% in overall stress-related symptoms in patients with psychosomatic problems compared to a control group [82, 83].

4. Discussion

Despite a long history of traditional use and widespread availability, relatively few human intervention studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of tulsi for clinical conditions and this is the first comprehensive literature review of published human research on the ingestion of tulsi as a single herbal intervention. The studies identified in this review could be classified according to three main clinical domains including metabolic disorders (15 studies), neurocognitive or mood conditions (4 studies), and immunity and infections (5 studies), which are all extremely relevant to the growing world-wide epidemic of lifestyle-related chronic disease. The finding that the reviewed studies reported favourable clinical effects across these domains suggests that tulsi may indeed be an effective adaptogen that has a role in helping to address the psychological, physiological, immunological, and metabolic stresses of modern living.

It is interesting that tulsi has important clinical effects across diverse therapeutic domains, all of which may have inflammation as an underlying factor. The anti-inflammatory effects of tulsi have been previously documented in many in vitro and in vivo studies [43, 85–88], and it is likely that tulsi has multiple bioactive secondary metabolites that act alone or synergistically to inhibit inflammatory pathways. There is also evidence to suggest that tulsi may be useful as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy and nutrition in the treatment of metabolic disorders thereby reducing the need for high doses of drugs, which may have adverse effects. The clinical effects demonstrated in the reviewed studies suggest tulsi may have an important role in addressing other inflammatory disorders and that the Ayurvedic tradition of consuming tulsi on a daily basis may be an effective lifestyle measure to address many modern chronic diseases.

The most commonly used part of the tulsi plant is the leaf (dried or fresh), which is known to contain several bioactive compounds including eugenol, ursolic acid, β-caryophyllene, linalool, and 1,8-cineole [89–91]. Eugenol has been found to be the major bioactive metabolite common to all three tulsi varieties with varying amounts in each cultivar [92, 93] and it has recently been suggested to act via dual cellular mechanisms to lower blood glucose levels. These include competitively preventing the binding of glucose to serum albumin and inhibiting the conversion of complex carbohydrate to glucose [93]. However, while eugenol has been shown to be bioactive, the phytochemical composition of tulsi is very complex and varies depending on different conditions [94–97] and there are many other potential active secondary metabolites such as other phenylpropanoids (methyl eugenol, rosmarinic acid), monoterpenes (ocimene), and sesquiterpenes (germacrene) that could alone or synergistically produce therapeutic benefits [98].

All reviewed studies reported favourable clinical effects with minimal or no side effects irrespective of dose, formulation, or the age or gender of participants, with only one clinical trial reporting transient mild nausea [62]. As the longest study was only 13 weeks, the failure to report any adverse effects does not preclude the presence of any long term side effects; however, the long traditional history of regular tulsi use suggests any serious long term effects are unlikely and that daily ingestion of tulsi is safe. Furthermore, the results of this review are consistent with previous evidence for the clinical efficacy and safety of tulsi, which includes multiple in vitro and in vivo studies and many human clinical trials in addition to traditional use.

4.1. Limitations and Scope

This review, which comprehensively reviewed all human clinical trials published in English language on ingestion of tulsi as a single herb, has many limitations. While the review included 24 studies and minimized bias by using a systematic and independent search strategy without limiting publication year or study design, we cannot be certain that all studies were located; this is especially due to the fact that almost all studies were conducted in India and published in local journals, some of which are very difficult to access or search. There may also be unpublished studies that report negative outcomes [99]. Furthermore, while the reviewed studies were consistent in reporting positive effects of tulsi in humans, only 7 out of 24 can be considered high quality studies with all but three failing to include a double-blind strategy. Tulsi's therapeutic effects may have therefore been overestimated and while the efficacy of tulsi was reported across a wide range of formulations and doses, many studies also failed to provide details of the cultivar, dosage form, or specific dosage or quality control measures of the tulsi used.

This review suggests that tulsi is an example of the Ayurvedic holistic lifestyle approach to health and appears to provide a vast array of health benefits that offers solutions to many modern day health problems. While the reviewed studies could be classified into three major therapeutic domains, there is insufficient evidence for any specific tulsi formulation to assist in any one condition. More rigorous studies with larger sample sizes and longer durations and standardised formulations are therefore needed before specific recommendations can be made for the treatment of any specific disease. This review further highlights the need to investigate and determine unique signature compounds specific to each of the three tulsi varieties, to not only identify the bioactive metabolites that may synergistically interact, but also shed light on the underlying mechanism of action on metabolic and inflammatory pathways.

5. Conclusion

Despite the lack of large-scale or long term clinical trials on the effect of tulsi in humans, the findings from 24 human studies published to date suggest that the tulsi is a safe herbal intervention that may assist in normalising glucose, blood pressure and lipid profiles, and dealing with psychological and immunological stress. Furthermore, these studies indicate the daily addition of tulsi to the diet and/or as adjunct to drug therapy can potentially assist in prevention or reduction of various health conditions and warrants further clinical evaluation.

Acknowledgments

Negar Jamshidi is a Ph.D. student supported by an RMIT University Scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

Professor Marc M. Cohen receives remuneration as a consultant and advisor to Organic India Pty. Ltd., which is a company that manufactures and distributes tulsi products. This article is the independent work of the authors and Organic India did not have input into the article's content or the decision to publish it.

References

- 1.Nadkarni K., Nadkarni A. Indian Materia Medica with Ayurvedic, Unani-Tibbi, Siddha, Allopathic, Homeopathic, Naturopathic & Home Remedies. Vol. 2. Bombay, India: Popular Prakashan Private Ltd; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee A. P. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India, Part I, Volume IV. 1st. New Delhi, India: Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Department of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebbar S. S., Harsha V. H., Shripathi V., Hegde G. R. Ethnomedicine of Dharwad district in Karnataka, India—plants used in oral health care. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2004;94(2-3):261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dadysett H. J. On the various domestic remedies, with their effects, used by the people of India for certain diseases of the ear. The Lancet. 1899;154(3968):781–782. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)59040-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chopra R., Chopra I. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants. Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, New Delhi, India, 1992.

- 6.Kothari S. K., Bhattacharya A. K., Ramesh S., Garg S. N., Khanuja S. P. S. Volatile constituents in oil from different plant parts of methyl eugenol-rich Ocimum tenuiflorum L.f. (syn. O. sanctum L.) grown in South India. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 2005;17(6):656–658. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2005.9699025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parrotta J. A. Healing Plants of Peninsular India. Oxfordshire, UK: CABI; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orwa C., Mutua A., Kindt R., Jamnadass R., Simons A. Agroforestree Database: A Tree Species Reference and Selection Guide Version 4.0. Nairobi, Kenya: World Agroforestry Centre ICRAF; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhamra S., Heinrich M., Howard C., Johnson M., Slater A. DNA authentication of tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) using the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and the chloroplast intergenic spacer trnH-psbA. Planta Medica. 2015;81(16, PW_20) doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1565644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhury T., Mandal A., Roy S. C., De Sarker D. Diversity of the genus Ocimum (Lamiaceae) through morpho-molecular (RAPD) and chemical (GC–MS) analysis. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carović-Stanko K., Liber Z., Besendorfer V., et al. Genetic relations among basil taxa (Ocimum L.) based on molecular markers, nuclear DNA content, and chromosome number. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2010;285(1):13–22. doi: 10.1007/s00606-009-0251-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jothie Richard E., Illuri R., Bethapudi B., et al. Anti-stress activity of Ocimum sanctum: possible effects on hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Phytotherapy Research. 2016;30(5):805–814. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venu Prasad M. P., Khanum F. Antifatigue activity of Ethanolic extract of Ocimum sanctum in rats. Research Journal of Medicinal Plant. 2012;6(1):37–46. doi: 10.3923/rjmp.2012.37.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabassum I., Siddiqui Z. N., Rizvi S. J. Effects of Ocimum sanctum and Camellia sinensis on stress-induced anxiety and depression in male albino Rattus norvegicus. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;42(5):283–288. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.70108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suanarunsawat T., Anantasomboon G., Piewbang C. Anti-diabetic and anti-oxidative activity of fixed oil extracted from Ocimum sanctum L. leaves in diabetic rats. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2016;11(3):832–840. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husain I., Chander R., Saxena J. K., Mahdi A. A., Mahdi F. Antidyslipidemic effect of Ocimum sanctum leaf extract in Streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 2015;30(1):72–77. doi: 10.1007/s12291-013-0404-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raja T., Reddy R. R. N., Priyadharshini M. B. An evaluation of anti-hyperglycemic activity of Ocimum sanctum Linn (leaves) in Wister rats. The Pharma Innovation Journal. 2016;5(1):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutili F. J., Gatlin D. M., Rossi W., Heinzmann B. M., Baldisserotto B. In vitro effects of plant essential oils on non-specific immune parameters of red drum, Sciaenops ocellatus L. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 2016;100(6):1113–1120. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panprommin D., Kaewpunnin W., Insee D. Effects of holy basil (Ocimum sanctum) extract on the growth, immune response and disease resistance against Streptococcus agalactiae of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) International Journal of Agriculture and Biology. 2016;18(4):677–682. doi: 10.17957/ijab/15.0143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godhwani S., Godhwani J. L., Was D. S. Ocimum sanctum- a preliminary study evaluating its immunoregulatory profile in albino rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1988;24(2-3):193–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aruna K., Sivaramakrishnan V. M. Anticarcinogenic effects of some Indian plant products. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1992;30(11):953–956. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(92)90180-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee S., Prashar R., Kumar A., Rao A. R. Modulatory influence of alcoholic extract of Ocimum leaves on carcinogen-metabolizing enzyme activities and reduced glutathione levels in mouse. Nutrition and Cancer. 1996;25(2):205–217. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin C.-C., Chao P.-Y., Shen C.-Y., et al. Novel target genes responsive to apoptotic activity by ocimum gratissimum in human osteosarcoma cells. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2014;42(3):743–767. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X14500487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godhwani S., Godhwani J. L., Vyas D. S. Ocimum sanctum: an experimental study evaluating its anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activity in animals. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1987;21(2):153–163. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(87)90125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanko Y., Magaji G. M., Yerima M., Magaji R. A., Mohammed A. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of aqueous leaves extract of Ocimum Gratissimum (Labiate ) in Rodents. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines. 2008;5(2):141–146. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v5i2.31265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akinmoladun A. C., Ibukun E., Afor E., Obuotor E., Farombi E. Phytochemical constituent and antioxidant activity of extract from the leaves of Ocimum gratissimum. Scientific Research and Essays. 2007;2(5):163–166. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelm M. A., Nair M. G., Strasburg G. M., DeWitt D. L. Antioxidant and cyclooxygenase inhibitory phenolic compounds from Ocimum sanctum Linn. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0944-7113(00)80015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang H.-C., Chiu Y.-W., Lin Y.-M., et al. Herbal supplement attenuation of cardiac fibrosis in rats with CCl4-induced liver cirrhosis. Chinese Journal of Physiology. 2014;57(1):41–47. doi: 10.4077/cjp.2014.bab147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chattopadhyay R., Sarkar S., Ganguly S., Medda C., Basu T. Hepatoprotective activity of Ocimum sanctum leaf extract against paracetamol induced hepatic damage in rats. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;24(3):p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devi P. U., Ganasoundari A. Radioprotective effect of leaf extract of Indian medicinal plant Ocimum sanctum. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 1995;33(3):205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devi P. U., Ganasoundari A., Rao B. S. S., Srinivasan K. K. In vivo radioprotection by ocimum flavonoids: survival of mice. Radiation Research. 1999;151(1):74–78. doi: 10.2307/3579750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman M. S., Khan M. M., Jamal M. A. Anti-bacterial evaluation and minimum inhibitory concentration analysis of Oxalis corniculata and Ocimum santum against bacterial pathogens. Biotechnology. 2010;9(4):533–536. doi: 10.3923/biotech.2010.533.536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prasad G., Kumar A., Singh A. K. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils of some Ocimum species and clove oil. Fitoterapia. 1986;57(6):429–432. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasad M. P., Jayalakshmi K., Rindhe G. G. Antibacterial activity of ocimum species and their phytochemical and antioxidant potential. International Journal of Microbiology Research. 2012;4(8):302–307. doi: 10.9735/0975-5276.4.8.302-307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura C. V., Ueda-Nakamura T., Bando E., Negrão Melo A. F., Garcia Cortez D. A., Dias Filho Filho B. P. Antibacterial activity of Ocimum gratissimum L. essential oil. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94(5):675–678. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000500022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chattopadhyay R. R. Hypoglycemic effect of Ocimum sanctum leaf extract in normal and streptozotocin diabetic rats. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 1993;31(11):891–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aguiyi J. C., Obi C. I., Gang S. S., Igweh A. C. Hypoglycaemic activity of Ocimum gratissimum in rats. Fitoterapia. 2000;71(4):444–446. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(00)00143-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rai V., Iyer U., Mani U. V. Effect of Tulasi (Ocimum sanctum) leaf powder supplementation on blood sugar levels, serum lipids and tissues lipids in diabetic rats. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 1997;50(1):9–16. doi: 10.1007/bf02436038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srinivas N., Sali K., Bajoria A. Therapeutic aspects of Tulsi unraveled: a review. Journal of Indian Academy of Oral Medicine and Radiology. 2016;28(1, article no. 17) doi: 10.4103/0972-1363.189984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baliga M. S., Rao S., Rai M. P., D'Souza P. Radio protective effects of the Ayurvedic medicinal plant Ocimum sanctum Linn. (Holy Basil): a memoir. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 2016;12(1):20–27. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.151422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fonseka H. R. D., Kulathunga W. M. S. S. K., Peiris A., Arawwawala L. D. A. M. A review on the therapeutic potentials of Ocimum sanctum Linn: in the management of diabetes Mellitus (Madhumeha) Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2015;4(3) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen M. M. Tulsi—Ocimum sanctum: a herb for all reasons. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine. 2014;5(4):251–259. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.146554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamyab A. A., Eshraghian A. Anti-inflammatory, gastrointestinal and hepatoprotective effects of Ocimum sanctum Linn: an ancient remedy with new application. Inflammation and Allergy - Drug Targets. 2013;12(6):378–384. doi: 10.2174/1871528112666131125110017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vishwabhan S., Birendra V. K., Vishal S. A review on ethnomedical uses of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) International Research Journal of Pharmacy. 2011;2:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pattanayak P., Behera P., Das D., Panda S. K. Ocimum sanctum Linn. A reservoir plant for therapeutic applications: an overview. Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2010;4(7):95–105. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.65323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhargava K. P., Singh N. Anti-stress activity of Ocimum sanctum Linn. The Indian journal of medical research. 1981;73:443–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakina M. R., Dandiya P. C., Hamdard M. E., Hameed A. Preliminary psychopharmacological evaluation of Ocimum sanctum leaf extract. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1990;28(2):143–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(90)90023-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sood S., Narang D., Thomas M. K., Gupta Y. K., Maulik S. K. Effect of Ocimum sanctum Linn. on cardiac changes in rats subjected to chronic restraint stress. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;108(3):423–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitra E., Ghosh D., Ghosh A. K., et al. Aqueous Tulsi leaf (Ocimum sanctum) extract possesses antioxidant properties and protects against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in rat heart. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2014;6(1):500–513. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okoli C. O., Ezike A. C., Agwagah O. C., Akah P. A. Anticonvulsant and anxiolytic evaluation of leaf extracts of Ocimum gratissimum, a culinary herb. Pharmacognosy Research. 2010;2(1):36–40. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.60580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okomolo F. C. M., Mbafor J. T., Bum E. N., et al. Evaluation of the sedative and anticonvulsant properties of three Cameroonian plants. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines. 2011;8(5):181–190. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhar M. L., Dhar M. M., Dhawan B. N., Mehrotra B. N., Ray C. Screening of Indian plants for biological activity: I. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 1968;6(4):232–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giri J., Suganthi B., Meera G. Effect of Tulasi (Ocimum sanctum) on diabetes mellitus. The Indian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics. 1987;24:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarkar A., Lavania S. C., Pandey D. N., Pant M. C. Changes in the blood lipid profile after administration of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) leaves in the normal albino rabbits. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1994;38(4):311–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta S., Mediratta P. K., Singh S., Sharma K. K., Shukla R. Antidiabetic, antihypercholesterolaemic and antioxidant effect of Ocimum sanctum (Linn) seed oil. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 2006;44(4):300–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patil R., Patil R., Ahirwar B., Ahirwar D. Isolation and characterization of anti-diabetic component (bioactivity—guided fractionation) from Ocimum sanctum L. (Lamiaceae) aerial part. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2011;4(4):278–282. doi: 10.1016/s1995-7645(11)60086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chandra A., Mahdi A. A., Singh R. K., Mahdi F., Chander R. Effect of Indian herbal hypoglycemic agents on antioxidant capacity and trace elements content in diabetic rats. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2008;11(3):506–512. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2007.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reddy S. S., Karuna R., Baskar R., Saralakumari D. Prevention of insulin resistance by ingesting aqueous extract of Ocimum sanctum to fructose-fed rats. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2008;40(1):44–49. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mukherjee R., Dash P. K., Ram G. C. Immunotherapeutic potential of Ocimum sanctum (L) in bovine subclinical mastitis. Research in Veterinary Science. 2005;79(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kundu P. K., Chatterjee P. Meta-analysis of Diabecon tablets: efficacy and safety. Indian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2010;20(9):p. 653. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gandhi R., Chauhan B., Jadeja G. Effect of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) powder on hyperglycemic patient. Indian Journal of Applied Research. 2016;6(5) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Satapathy S., Das N., Bandyopadhyay D., Mahapatra S. C., Sahu D. S., Meda M. Effect of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn.) supplementation on metabolic parameters and liver enzymes in young overweight and obese subjects. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12291-016-0615-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Venkatesan P., Sengupta R. Effect of supplementation of Tulsi leaves or curry leaves or combination of both type 2 diabetes. International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience (IJPAB) 2015;3(2):331–337. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srinivasa Prasadacharyulu C. Leaves of Ocimum sanctum [LOS]: a potent antidiabetic herbal medicine. International Journal of Innovative Research and Development. 2014;3(4):277–281. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ahmad M., Faraazi A. A., Aamir M. N. The effect of ocimum sanctum and ledum palustre on serum uric acid level in patients suffering from gouty arthritis and hyperuricaemia. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Ethiopia. 2013;27(3):469–473. doi: 10.4314/bcse.v27i3.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Devra D. K., Mathur K. C., Agrawal R. P., Bhadu I., Goyal S., Agarwal V. Effect of tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn) on clinical and biochemical parameters of metabolic syndrome. Journal of Natural Remedies. 2012;12(1):63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Somasundaram G., Manimekalai K., Salwe K. J., Pandiamunian J. Evaluation of the antidiabetic effect of Ocimum sanctum in type 2 diabetic patients. International Journal of Life Science and Pharma Research. 2012;5:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dineshkumar B., Analava M., Manjunatha M. Antidiabetic and hypolipidaemic effects of few common plants extract in type 2 diabetic patients at Bengal. International Journal of Diabetes and Metabolism. 2010;18(2):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kochhar A., Sharma N., Sachdeva R. Effect of supplementation of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) and Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf powder on diabetic symptoms, anthropometric parameters and blood pressure of non insulin dependent male diabetics. Studies on Ethno-Medicine. 2009;3(1):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agrawal P., Rai V., Singh R. B. Randomized placebo-controlled, single blind trial of holy basil leaves in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1996;34(9):406–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luthy N. A study of a possible oral hypoglycemic factor in albahaca morada (Ocimum sanctum L.) The Ohio Journal of Science. 1964;64(3):223–224. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Verma A. K., Dubey G. P., Agrawal A. Biochemical studies on serum Hb, Sugar, Urea and lipid profile under influence of ocimum sanctum L in aged patients. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology. 2012;5(6):791–794. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhargava A., Gangwar L., Grewal H. S. To study the effect of holy basil leaves on low blood pressure (hypotension) women aged 18–30 years. International Conference on Food and Agricultural Sciences. 2013;55(16):83–86. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mondal S., Mirdha B., Padhi M., Mahapatra S. Dried leaf extract of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn) reduces cardiovascular disease risk factors: results of a double blinded randomized controlled trial in healthy volunteers. Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2012;1(4):177–181. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarvaiya S. Studies on hypertension with special reference to hypotensive effect of Ocimum sanctum [Ph.D. thesis] Anand, India: Sardar Patel University; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Venu Prasad M. Antifatigue and Neuroprotective Properties of Selected Species of Ocimum L. Mysore, India: University of Mysore; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mondal S., Varma S., Bamola V. D., et al. Double-blinded randomized controlled trial for immunomodulatory effects of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn.) leaf extract on healthy volunteers. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;136(3):452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sharma G. Anti-asthmatic efficacy of Ocimum sanctum. Sachitra Ayurved. 1983;35:665–668. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rajalakshmi S., Sivanandam G., Veluchamy G. Role of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn.) in the management of Manjal Kamalai (viral hepatitis) Journal of Research in Ayurveda and Siddha. 1986;9(3-4):118–123. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Das S., Chandra A., Agarwal S., Singh N. Ocimum sanctum (tulsi) in the treatment of viral encephalitis (A preliminary clinical trial) Antiseptic. 1983;80:323–327. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sampath S., Mahapatra S. C., Padhi M. M., Sharma R., Talwar A. Holy basil (Ocimum sanctum Linn.) leaf extract enhances specific cognitive parameters in healthy adult volunteers: a placebo controlled study. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2015;59(1):69–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saxena R. C., Singh R., Kumar P., et al. Efficacy of an extract of ocimum tenuiflorum (OciBest) in the management of general stress: A Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:7. doi: 10.1155/2012/894509.894509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bhattacharyya D., Sur T. K., Jana U., Debnath P. K. Controlled programmed trial of Ocimum sanctum leaf on generalized anxiety disorders. Nepal Medical College Journal. 2008;10(3):176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jadad A. R., Moore R. A., Carroll D., et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Malairaman U., Mehta V., Sharma A., Kailkhura P. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antidiabetic activity of hydroalcoholic extract of Ocimum sanctum: an in-vitro and in-silico study. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2016;9(5):44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kavitha S., John F., Indira M. Amelioration of inflammation by phenolic rich methanolic extract of ocimum sanctum linn. Leaves in isoproterenol induced myocardial infarction. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 2015;53(10):632–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Soni K., Lawal T., Wicks S., Patel U., Mahady G. Boswellia serrata and Ocimum sanctum extracts reduce inflammation in an ova-induced asthma model of BALB/c mice. Planta Medica. 2015;81(11) doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1556201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kalabharathi H. L., Suresha R. N., Pragathi B., Pushpa V. H., Satish A. M. Anti inflammatory activity of fresh tulsi leaves (Ocimum Sanctum) in albino rats. International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences. 2011;2(4):45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bernhardt B., Szabó K., Bernáth J. Sources of variability in essential oil composition of Ocimum americanum and Ocimum tenuiflorum. Acta Alimentaria. 2015;44(1):111–118. doi: 10.1556/aalim.44.2015.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Awasthi P. K., Dixit S. C. Chemical Compositions of Ocimum sanctum Shyama and 0cimum sanctum Rama Oils from the Plains of Northern India. Journal of Essential Oil-Bearing Plants. 2007;10(4):292–296. doi: 10.1080/0972060x.2007.10643557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tewari B. B., Gomathinayagam S. A critical review on Ocimum tenuflorum, Carica papaya and Syzygium cumini: the medicinal flora of Guyana. Revista Boliviana de Química. 2014;31(2):28–41. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anand A., Jayaramaiah R. H., Beedkar S. D., et al. Comparative functional characterization of eugenol synthase from four different Ocimum species: implications on eugenol accumulation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Proteins and Proteomics. 2016;1864(11):1539–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Singh P., Jayaramaiah R. H., Agawane S. B., et al. Potential dual role of eugenol in inhibiting advanced glycation end products in diabetes: proteomic and mechanistic insights. Scientific Reports. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep18798.18798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.De Vasconcelos Silva M. G., Craveiro A. A., Abreu Matos F. J., MacHado M. I. L., Alencar J. W. Chemical variation during daytime of constituents of the essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum leaves. Fitoterapia. 1999;70(1):32–34. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(98)00020-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Johnson M. Studies on intra-specific variation in a multipotent medicinal plant Ocimum sanctum Linn. Using isozymes. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2012;2(1):S21–S26. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60123-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vani S. R., Cheng S. F., Chuah C. H. Comparative study of volatile compounds from genus Ocimum. American Journal of Applied Sciences. 2009;6(3):523–528. doi: 10.3844/ajas.2009.523.528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Boonyakiat D., Boonprasom P. Effect of vacuum cooling and packaging on physico-chemical properties of 'Red' holy basil. Acta Horticulturae. 2010;877:419–426. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Singh P., Kalunke R. M., Giri A. P. Towards comprehension of complex chemical evolution and diversification of terpene and phenylpropanoid pathways in Ocimum species. RSC Advances. 2015;5(129):106886–106904. doi: 10.1039/c5ra16637c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ernst E., Pittler M. H. Alternative therapy bias. Nature. 1997;385(6616) doi: 10.1038/385480c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]