Abstract

Patients with a diverse spectrum of rare genetic disorders can present with inflammatory bowel diseases (monogenic IBD). Patients with these disorders often develop symptoms during infancy or early childhood, along with endoscopic or histologic features of Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis or IBD unclassified. Defects in interleukin 10 signaling have a Mendelian inheritance pattern with complete penetrance of intestinal inflammation. Several genetic defects that disturb intestinal epithelial barrier function or affect innate and adaptive immune function have incomplete penetrance of the IBD-like phenotype. Several of these monogenic conditions do not respond to conventional therapy and are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Due to the broad spectrum of these extremely rare diseases, a correct diagnosis is frequently a challenge and often delayed. In many cases, these diseases cannot be categorized based on standard histologic and immunologic features of IBD. Genetic analysis is required to identify the cause of the disorder and offer the patient appropriate treatment options, which include medical therapy, surgery, or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In addition, diagnosis based on genetic analysis can lead to genetic counseling for family members of patients. We describe key intestinal, extra-intestinal, and laboratory features of 50 genetic variants associated with IBD-like intestinal inflammation. We provide approaches for identifying patients likely to have these disorders. We discuss classical approaches to identify these variants in patients, starting with phenotypic and functional assessments that lead to analysis of candidate genes. As a complementary approach, we discuss parallel genetic screening using next-generation sequencing followed by functional confirmation of genetic defects.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, unclassified colitis, indeterminate colitis, immunodeficiency, pediatrics, IBD unclassified, genetics, next-generation sequencing, whole exome sequencing

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are a diverse group of complex and multifactorial disorders. The most common subtypes are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)1, 2. There is increasing evidence that IBD arises in genetically susceptible individuals, who develop a chronic and relapsing inflammatory intestinal immune response toward the intestinal microbiota. Disease development and progression are clearly influenced by environmental factors, which have contributed to the rapid global increase in the incidence of IBD during the last decades3.

Developmental, Genetic, and Biologic Differences Among Age Groups

IBD location, progression, and response to therapy have age-dependent characteristics4–10. The onset of intestinal inflammation in children can affect their development and growth. Age of onset can also provide information about the type of IBD and its associated genetic features. For example, patients with defects in interleukin (IL)10 signaling have a particularly early onset of IBD, within the first few months of life. Our increasing understanding of age-specific characteristics has led to changes in classification of pediatric IBD. Based on disease characteristics, several age subgroups have been proposed corresponding largely to the generally accepted age stages defined by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pediatric terminology11.

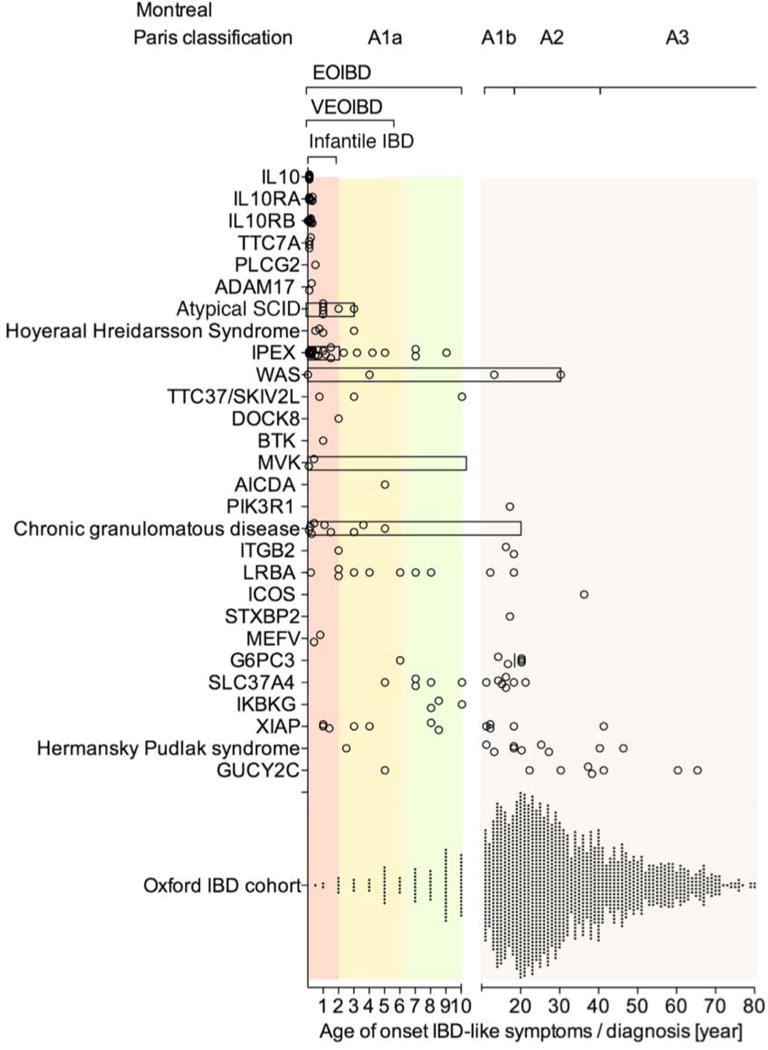

Five major pediatric IBD age subgroups can be summarized (Table 1). The Montreal classification12 originally defined patients with onset of <17 years as a distinct group of pediatric onset IBD patients (A1). The Pediatric Paris modification13 of the Montreal classification12 later defined pediatric onset group of IBD as A1, but subdivided an early onset IBD group diagnosed prior to 10 years of age as subgroup A1a, whereas patients from age 10 to <17 years of onset were classified as A1b13. This reclassification was based on several findings indicating that children diagnosed with IBD before 10 years of age, develop a somewhat different disease phenotype compared to adolescents or adults. Particular differences that supported the modification were paucity of ileal inflammation and predominance of pancolonic inflammation, as well as a low rate of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies in A1a CD patients, with an increased risk for surgery (colectomy) and biological therapy in A1a UC patients13. In this review we will refer to the A1a group as early onset IBD (EOIBD). Very early onset IBD (VEOIBD), the subject of this review, represents children diagnosed prior to 6 years of age14. This age classification includes a neonatal, infantile, toddler and early childhood group. Proposing an age group between the infantile IBD and the A1a early onset IBD makes sense when taking account that in multiple relevant subgroups of patients with monogenic IBD (such as XIAP deficiency, Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD) or other neutrophil defects) the age of onset is often above the age of 2 years of age. On the other hand, from the age of 7 years there is a substantial rise in the frequency of patients diagnosed with conventional polygenic IBD, particularly CD6, 15. This leads to a relative enrichment of monogenic IBD in the age group of under 6 years of onset. Approximately one fifth of children with IBD under 6 and one third of children with IBD under 3 years of age are labeled as IBD unclassified (IBDU or indeterminate colitis)16 reflecting the lack of a refined phenotyping tool to categorize relevant subgroup of patients with VEOIBD, as well as a potential bias due to incomplete diagnostic workup in very young children15. The enrichment of monogenic defects in EOIBD and VEOIBD becomes apparent when relating the approximate 1% of patients with IBD under 6 and less than 0.2% under 1 year of age to the literature reports that the majority of monogenic disorders can present under 6 years and even under 1 year of age (Figure 1). Although it is generally accepted that many VEOIBD patients have low response rates to conventional anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory therapy, there is a paucity of well-designed studies to support this hypothesis. Infantile (and toddler) onset of IBD was highlighted in the Pediatric Paris classification, because of higher rates of affected first degree family relatives, indicating an increased genetic component, severe disease course and high rate of resistance to immunosuppressive treatment13. Features of autoimmunity with dominant lymphoid cell infiltration are frequently found in infants and toddlers17. Such patients are likely to have pancolitis, subgroups of patients develop severely ulcerating perianal disease, there is a high rate of resistance to conventional therapy, a high rate of first-degree relatives with IBD and increased lethality4–8. Recent guidelines and consensus approaches for the diagnosis and management of IBD18, 19 highlight that children with infantile onset of IBD have a particular high risk for an underlying primary immunodeficiency. An extreme early subgroup, neonatal IBD, has been described with manifestations during the first 27 days of life4, 5, 8.

Table 1.

Subgroups of Pediatric IBD According to Age.

| Group | Classification | Age range (y) |

|---|---|---|

| Pediatric-onset IBD | Montreal A1 | Younger than 17 |

| EOIBD | Paris A1a | Younger than 10 |

| VEOIBD | Younger than 6 | |

| Infantile (and toddler) onset IBD | Younger than 2 | |

| Neonatal IBD | First 28 days of age |

Figure 1. Age of Onset of IBD-like Symptoms in Patients with Monogenic Diseases.

Multiple genetic defects are summarised in the group of atypical SCID, Hoyeraal Hreidarsson Syndrome, chronic granulomatous disease, and Hermansky Pudlak syndrome. By comparison, an unselected IBD population is presented (Oxford IBD cohort study; pediatric and adult referral based IBD cohort, n=1605 patients comprising CD, UC and IBDU). Symbols represent individual patients. Bar represent the age range of case series when individual data are not available. Age range of infantile IBD, VEOIBD, EOIBD and Montreal/Paris classification A1a, A1b, A2 and A3 are shown for reference.

Age of onset data refer to references provided in table 2. Additional references for disease subgroups are provided in supplemental information to Figure 1.

Guidelines for the diagnosis and classification of IBD in the pediatric age group13, 18–21 have addressed the need to recognize monogenic disorders and immunodeficiencies in particular, since these require a different treatment strategy than conventional IBD. Current guidelines do not, however, cover the spectrum of these rare subgroups of monogenic IBD. The identification of an underlying genetic defect is indeed challenging, owing to the orphan nature of these diseases, the wide phenotypic spectrum of disorders, and the limited information available on most genetic defects. This review and practice guide provides a comprehensive summary of the monogenic causes of IBD-like intestinal inflammation and provides a conceptual framework for the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected monogenic IBD. We categorize known genetic defects into functional subgroups and discuss key intestinal and extra-intestinal findings. Based on the enrichment of known causative mutations as well as extreme phenotypes in the very young, we have focused on a practical approach to detect monogenic disorders in patients with VEOIBD and infantile IBD in particular. Since there is only modest biological evidence to support age-specific categorization of IBD above infantile IBD and within the EOIBD subgroup, we discuss also disease- and gene specific ages of onset of intestinal inflammation (Figure 1).

Epidemiology of Pediatric IBD

Approximately 20%–25% of patients with IBD develop intestinal inflammation during childhood and adolescence. IBD in children less than 1 year of age has been reported in approximately 1%, and VEOIBD in about 15% of pediatric patients with IBD6. VEOIBD has an estimated incidence of 4.37/100,000 children and a prevalence of 14/100,000 children22. The incidence of pediatric IBD is increasing22, 23. Some studies reported that the incidence of IBD is increasing particularly rapidly in young children24,25, although not all studies have confirmed this observation9.

Polygenic and Monogenic Forms of IBD

Twin studies have provided the best evidence for a genetic predisposition to IBD, which is stronger for CD than UC. Conventional IBD is a group of polygenic disorders where hundred(s) of susceptibility loci contribute to the overall disease risk. Meta-analyses of (genome-wide) association studies of adolescent and adult-onset IBD identified 163 IBD-associated genetic loci encompassing about 300 potential candidate genes. However, it is very important to consider that these 163 loci individually contribute only a small percentage of the expected heritability in IBD26. This suggests that IBD including CD and UC can be regarded as a classical polygenic disorder. Findings from initial genome-wide pediatric association studies focused on adolescents and confirm a polygenic model27, 28. There are no well- powered genome-wide association studies of patients with EOIBD or VEOIBD.

Although most cases of IBD are caused by a polygenic contribution towards genetic susceptibility, there is a diverse spectrum of rare genetic disorders that produce IBD-like intestinal inflammation29. The genetic variants that cause these disorders have a large effect on the function of the gene function. However, these variants are so rare in allele frequency (many private mutations), those genetic signals are not detected in genome-wide association studies of patients with IBD. With recent advances in genetic mapping and sequencing techniques and increasing awareness of the importance of those “orphan” disorders, approximately 50 genetic disorders have been identified and associated with IBD-like immunopathology (partially summarized see Uhlig et al.29). For simplicity, we call these disorders in the following monogenic IBD even if there is a spectrum of penetrance of the IBD phenotype. We will compare those monogenic forms of IBD with polygenic conventional IBD.

All data suggest that the fraction of monogenic disorders with IBD-like presentation among all IBD patients correlates inversely with the age of onset. Despite a growing genotype spectrum, monogenic disorders still only account for a fraction of VEOIBD cases. The true fraction is unknown. In a study of 66 patients who developed IBD at ages younger than 5 years, 5 patients were found to carry mutations in IL10RA, 8 in IL10RB, and 3 in IL1030. All patients developed symptoms within the first 3 months of life30. A recent study detected 4 patients with presumed pathogenic XIAP mutations in a group of 275 pediatric IBD patients (A1a/A1b Paris classification) and 1047 adult onset CD patients (A2 and A3 Montreal)31. Since all patients with XIAP variants were infantile to adolescent male CD patients this could suggest an approximate prevalence of 4% among young male IBD patients. However, studies like these focus on specific genes and may suffer from strong selection bias towards an expected clinical sub-phenotype. They might therefore overestimate the frequency of specific variants. Analysis of large, multicenter, population-based cohorts is needed to determine the proportion of VEOIBD caused by single gene defects and to estimate penetrance.

Monogenic defects have been found to alter intestinal immune homeostasis via several mechanisms (Table 2). These include disruption of the epithelial barrier and epithelial response, and reduced clearance of bacteria by neutrophil granulocytes, and other phagocytes. Other single-gene defects induce hyper- or auto-inflammation, or disrupt T- and B-cell selection and activation. Hyper-activation of the immune response can result from defects in immune inhibitory mechanisms, such as defects in IL10 signaling or dysfunctional regulatory T cell activity.

Table 2.

Genetic Defects and Phenotype of Monogenic IBD

| Group | Syndrome/disorder | Gene | Inheritance | Intestinal findings

|

Extraintestinal findings

|

References | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD-like | Granuloma | UC-like | Epithelial defect (apoptosis) | Disease location (1–5) | Perianal fistula/abscess | Penetrating fistulas | Strictures | Skin lesions | Autoimmunity, inflammation | HLH/MAS | Neoplasia | |||||

| 1 Epithelial barrier | Dystrophic bullosa | COL7A1 | AR | + | 3 | + | eb | 32 (A. Martineza) | ||||||||

| 2 | Kindler syndrome | FERMT1 | AR | + | + | 5 | + | eb | 32, 149 (A. Martineza) | |||||||

| 3 | X-linked ectodermal immunodeficiency | IKBKG | X | + | + | 3 | + | A, Vase | 34, 150, 151 | |||||||

| 4 | TTC7A deficiency | TTC7A | AR | + | 3 | + | 38 | |||||||||

| 5 | ADAM17 deficiency | ADAM17 | AR | (+) | + | 3 | n, h | 35 | ||||||||

| 6 | Familial diarrhea | GUCY2C | AD | + | 3 | + | 33 (A. Janeckea) | |||||||||

| 7 Phagocyte defects | CGD | CYBB | X | + | + | 1,3 | + | e | 39 | |||||||

| 8 | CGD | CYBA | AR | + | + | 3 | + | e | 41 | |||||||

| 9 | CGD | NCF1 | AR | + | + | 1,3 | + | e | 39 | |||||||

| 10 | CGD | NCF2 | AR | + | + | 1,3 | + | e | 39 | |||||||

| 11 | CGD | NCF4 | AR | + | + | 1,3 | e | 40 | ||||||||

| 12 | Glycogen storage disease type lb | SLC37A4 | AR | + | + | 1,3 | + | + | f | 48, 49, 53 | ||||||

| 13 | Congenital neutropenia | G6PC3 | AR | + | 1,3 | + | ? | (+) | f | 50, 138, 152 | ||||||

| 14 | Leukocyte adhesion deficiency 1 | ITGB2 | AR | + | 1,3 | + | + | f | 51, 52 | |||||||

| 15 Hyperinflammatory and | Mevalonate kinase deficiency | MVK | AR | 3 | + | + | A, SJ | + | 54, 55, 71 | |||||||

| 16 autoinflammatory disorders | Phospholipase C-γ2 defects | PLCG2 | AD | + | 3 | (eb), e | A, NSIP | 56 | ||||||||

| 17 | Familial Mediterranean fever | MEFV | AR | + | 5 | + | S | 57–59 | ||||||||

| 18 | Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5 | STXBP2 | AR | 3 | 69 | |||||||||||

| 19 | X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome 2 (XLP2) |

XIAP | X | + | + | 3 | + | + | (+) | + | ? | + | 31, 66–69, 72, 73, 127 | |||

| 20 | X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome 1 (XLP1) |

SH2D1A | X | 3 | + | + | 65 | |||||||||

| 21 | Hermansky–Pudlak 1 | HPS1 | AR | + | + | 3 | + | (+) | + | 60–63 | ||||||

| 22 | Hermansky–Pudlak 4 | HPS4 | AR | + | + | 3 | + | (+) | + | 60, 62, 153 | ||||||

| 23 | Hermansky–Pudlak 6 | HPS6 | AR | 3 | + | 64 | ||||||||||

| 24 T- and B-cell defects | CVID 1 | ICOS | AR | 5 | P | A | 86 | |||||||||

| 25 | CVID 8 | LRBA | AR | + | 3 | EN | AlHA | 87–89 | ||||||||

| 26 | IL-21 deficiency (CVID-like) | IL21 | AR | + | + | 90 | ||||||||||

| 27 | Agammaglobulinemia | BTK | X | + | 5 | AIHA | 75, 76 | |||||||||

| 28 | Agammaglobulinemia | PIK3R1 | AR | 5 | EN | + | 77 | |||||||||

| 29 | Hyper IgM syndrome | CD40LG | X | 1,5 | + | AIHA | 78 | |||||||||

| 30 | Hyper IgM syndrome | AICDA | AR | + | 1,3 | AIHA | 79 | |||||||||

| 31 | WAS | WAS | X | + | 5 | e | AIHA, A | 80 | ||||||||

| 32 | Omenn syndrome | DCLRE1C | AR | + | 1,3 | 81 | ||||||||||

| 33 | SCID | ZAP70 | AR | + | 5 | e | 154 | |||||||||

| 34 | SCID/hyper IgM syndrome | RAG2 | AR | 5 | + | AIHA | 82, 155 | |||||||||

| 35 | SCID | IL2RG | X | 3 | 156, 157 | |||||||||||

| 36 | SCID | LIG4 | AR | No further information | + | AN | 82 | |||||||||

| 37 | SCID | ADA | AR | No further information | + | AIHA | 82 | |||||||||

| 38 | SCID | CD3γ | AR | + | 5 | + | + | 95 | ||||||||

| 39 | Hoyeraal–Hreidarsson S. | DKC1 | X | (+) | 1,3 | + | +, n, h | + | 99–101 | |||||||

| 40 | Hoyeraal–Hreidarsson S. | RTEL1 | AR | + | 5 | + | +, n, h | + | 97, 98 | |||||||

| 41 | Hyper IgE syndrome | DOCK8 | AR | + | 1,5 | e | PSC | 158 | ||||||||

| 42 Immunoregulation | IPEX | FOXP3 | X | 3 | e, p | AIHA, HT, T1D… | 111,112 | |||||||||

| 43 | IPEX-like | IL2RA | AR | 2 | e | AIHA, HT, T1D… | 114 | |||||||||

| 44 | IPEX-like | STAT1 | AD | 2 | 116 | |||||||||||

| 45 | IL-10 signaling defects | IL10RA | AR | + | (+) | 3 | + | + | f, e | A | + | 30, 102–105, 107 | ||||

| 46 | IL-10 signaling defects | IL10RB | AR | + | (+) | 3 | + | + | f | A, AIH | + | 30, 102–105, 107 | ||||

| 47 | IL-10 signaling defects | IL10 | AR | + | 3 | + | + | 30, 102, 104, 105, 107 | ||||||||

| 48 Others | MASP deficiency | MASP2 | AR | + | + | A | 159 | |||||||||

| 49 | Trichohepatoenteric S. | SKIV2L | AR | 3 | h, + | 117, 160 | ||||||||||

| 50 | Trichohepatoenteric S. | TTC37 | AR | 3 | h, + | 117 | ||||||||||

NOTE. Genetic defects are grouped according to functional subgroups. Gene names refer to HUGO gene nomenclature. CD-like and UC-like were marked only when patient characteristics in the original reports were described as typical CD or UC pathologies. Unclassified or indeterminate colitis is the not specified default option. Disease location is classified as follows: 1, mouth; 2, enteropathy; 3, enterocolitis; 4, isolated ileitis; 5, colitis; 6, perianal disease. Epithelial defects refer in particular to finding of epithelial lining nonadherent at the basal membrane or increased epithelial apoptosis and epithelial tufting. Key laboratory findings are provided in Supplementary Table 1, and examples of additional defects of possible or unclear relevance are listed in the Supplementary Information for Table 1.

HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; AR, autosomal recessive; eb, epidermolysis bullosa; X, X-linked; A, arthritis; vase, vasculitis; n, nail; h, hair; AD, autosomal dominant; e, eczema; f, folliculitis/pyoderma; SJ, Sjögren syndrome; p, psoriasis; AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; AN, autoimmune neutropenia; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; HT, Hashimoto thyroiditis; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; TID, type 1 diabetes mellitus; MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; NSIP, non-specific interstitial pneumonitis; S, serositis.

Personal information and communication.

Epithelial Barrier and Response Defects

Genetic disorders that affect intestinal epithelial barrier function include dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa32, Kindler syndrome32, familial diarrhea caused by dominant activating mutations in guanylate cyclase C33, X-linked ectodermal dysplasia and immunodeficiency,34 and ADAM17 deficiency35.

X-linked ectodermal dysplasia and immunodeficiency, caused by hypomorphic mutations in IKBKG (encodes nuclear factor-κB essential modulator protein, NEMO),34 and ADAM-17 deficiency35 cause epithelial and immune dysfunction. Recently, TTC7A deficiency was described in patients with multiple intestinal atresia, with and without SCID immunodeficiency36, 37. Hypomorphic mutations in TTC7A have been found to cause VEOIBD without intestinal stricturing or severe immunodeficiency, most likely due to a defect in epithelial signaling38.

Dysfunction of Neutrophil Granulocytes

Variants in genes that affect neutrophil granulocytes (and other phagocytes) predispose individuals to IBD-like intestinal inflammation. Chronic granulomatous disease is characterized by genetic defects in components of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase (phox) complex. Genetic mutations in all 5 components of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase (phox) gp91-phox (CYBB), p22-phox (CYBA), p47-phox (NCF1), p67-phox (NCF2), and p40-phox (NCF4) are associated with immunodeficiency and can cause IBD-like intestinal inflammation.

As many as 40% of patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) develop CD-like intestinal inflammation39–41. Multiple granuloma and the presence of pigmented macrophages can indicate the group of defects histologically. Missense variants in NCF2 that affect RAC2 binding sites have recently been reported in patients with VEOIBD42. Recently, several heterozygous functional hypomorphic variants in multiple components of the NOX2 NADPH oxidase complex were detected in patients with VEOIBD that do not cause CGD-like immunodeficiency, but have a moderate effect on ROS production and confer susceptibility to VEOIBD43. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors can resolve intestinal inflammation in patients with CGD, but could increase the risk of severe infections in patients with CGD44. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) can cure CGD and resolve intestinal inflammation44–46. Monocytes produce high level of IL1 in those patients with CGD and an IL1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) was used to treat non-infectious colitis in those patients47.

In addition to CGD, a number of other neutrophil defects are associated with intestinal inflammation. Defects in glucose-6-phosphate-translocase (SLC37A4)48, 49 and glucose-6-phosphatase-catalytic subunit 3 (G6PC3)50 are associated with congenital neutropenia (and other distinctive features) but also predispose individuals to IBD. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency type 1 is caused by mutations in the gene encoding CD18 (ITGB2) and is associated with defective transendothelial migration of neutrophil granulocytes. Patients typically present with high peripheral granulocyte counts and bacterial infections and some presented with IBD-like features51, 52.

CD-like disease is a typical manifestation of glycogen storage disease type Ib, characterized by neutropenia and neutrophil granulocyte dysfunction48, 49, 53. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor has been used to treat neutropenia and colitis in some patients with glycogen storage disease type Ib53.

In addition to neutrophil defects, defects in several other genes, including WAS, LRBA, BTK, CD40LG, and FOXP3, can lead to autoantibody-induced or haemophagocytosis-induced neutropenia. These multi-dimensional mechanisms of secondary immune dysregulation indicate the functional complexity of some seemingly unrelated genetic immune defects and the broad effects they might have on the innate immune system.

Hyper- and Auto-inflammatory Disorders

VEOIBD has been described in a number of hyper- and auto-inflammatory disorders such as mevalonate kinase deficiency54, 55, phospholipase Cγ2 defects56, familial Mediterranean fever57–59, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (type 1, 4 and 6)60–64, X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome type 165 and type 2,66–68 or familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 569. Among these, mevalonate kinase deficiency is an prototypic auto-inflammatory disorder, characterized by increased activation of caspase 1 and subsequent activation of IL1β70. Inhibiting IL1β signaling with antibodies that block IL1b or IL1R antagonists can induce complete or partial remission in patients including those with VEOIBD54, 55, 71.

X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome 2 is caused by defects in the XIAP gene. At least 20% of patients with XIAP defects develop a CD-like immunopathology with severe fistulizing perianal phenotype66–68, 72, 73. In these patients, Epstein-Barr virus infections can lead to life-threatening hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Originally associated with a poor outcome after HSCT74, less toxic induction regimens could improve prognosis and cure this form of IBD67, 73.

Complex Defects in T- and B-cell Function

IBD-like immunopathology is a common finding in patients with defects in the adaptive immune system. Multiple genetic defects that disturb T- and/or B-cell selection and activation can cause complex immune dysfunction including immunodeficiency and autoimmunity as well as intestinal inflammation. Disorders associated with IBD-like immunopathology include B-cell defects such as common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), hyper-immunoglobulin (Ig)IgM syndrome, and a-gammaglobulinemia75–79. Several other primary immune deficiencies, such as Wiskott Aldrich syndrome80 (WAS) and atypical SCID or Omenn syndrome81, 82 can also cause IBD-like intestinal inflammation.

CVID and a-gammaglobulinemia and hyper-IgM syndrome

Patients with CVID have clinical features of different types of IBD spanning CD, UC, ulcerative proctitis-like findings83, 84. Although CVID is largely polygenic, a small proportion of cases of CVID have been associated with specific genetic defects. CVID type 1 is caused by variants in the gene encoding the inducible T-cell co-stimulator (ICOS)85, 86, whereas CVID type 8 is caused by variants in LRBA.87–89 Patients with these mutations can present with IBD-like pathology. Recently, IBD and CVID-like disease was described in a family with IL21 deficiency90.

Patients with a-gammaglobulinemia, caused by defects in BTK or PIK3R1, as well as patients with subtypes of hyper-IgM syndrome caused by defects in CD40LG, AICDA, or IKBKG can develop IBD-like immunopathology75–79,77–79. It is worth considering that several other immunodeficiencies, not regarded as primary B-cell defects, are similarly associated with low numbers of B cell and/or Igs (such as those caused by variants in SKIV2L, TTC37, see Table 2 and supplemental table 1).

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome is a primary immunodeficiency. Many patients with Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome present with UC-like non-infectious colitis during early infancy80. The syndrome is caused by the absence or abnormal expression of the cytoskeletal regulator WASP and is associated with defects in most immune subsets (effector and regulatory T cells, natural killer (NK) T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, NK cells, and neutrophils)91. In addition to features of UC, patients develop many other autoimmune complications. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation is the standard of care for those patients80. Patients who are not candidates for bone marrow transplantation have been successfully treated with experimental gene therapy approaches92, 93.

Atypical SCID defects

Patients with atypical SCID defects have residual B and T cell development and oligoclonal T-cell expansion94. VEOIBD is commonly observed in patients with atypical SCID, due to hypomorphic defects in multiple genes such as DCLRE1C, ZAP70, RAG2, IL2RG, LIG4, ADA, and CD3G81, 82, 95. This list of genes is likely not complete and it seems reasonable to assume that most genetic defects that cause T-cell atypical SCID also cause IBD.

A subset of patients with SCID present with severe eczematous rash (Omenn syndrome)81. It is not clear whether residual lymphocyte function in patients with hypomorphic TTC7A mutations is a precondition for IBD or contributes to VEOIBD38. Intestinal and skin lesions also develop in patients with SCID, due to graft vs host disease in response to maternal cells96.

Hoyeraal Hreidarsson Syndrome

Hoyeraal Hreidarsson Syndrome is a severe form of dyskeratosis congenita characterized by dysplastic nails, lacy reticular skin pigmentation and oral leukoplakia. It is a multi-organ disorder. Patients with mutations in RTEL197, 98 or DKC199–101 can develop SCID and intestinal inflammation.

Regulatory T cells and IL10 Signaling

Loss of function defects in IL10 and its receptor (encoded by IL10RA and IL10RB)102–106 cause VEOIBD with perianal disease and folliculitis within the first months of life. All patients with loss of function mutations that prevent IL10 signaling develop IBD-like immunopathology, indicating that these defects are a monogenic form of IBD with 100% penetrance106, 107. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 is secreted by natural and induced regulatory T cells (in particular intestinal CD4+FOXP3+ and Tr1 cells), macrophages, and B cells. Many intestinal and extra-intestinal cell types express the IL10 receptor and respond to IL10. Defects in IL10R signaling affect the differentiation of macrophage M1/M2, shifting them toward an inflammatory phenotype108. Defects in IL10 signaling are associated with extra-intestinal inflammation such as folliculitis or arthritis and predispose to B-cell lymphoma102, 103, 109. Conventional therapy options are largely not effective in patients with IL10 signaling defects but allogeneic matched or mismatched HSCT can induce sustained remission of intestinal inflammation30, 102, 103, 107, 110.

X-linked immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy (IPEX) syndrome is caused by mutations in the transcription factor FOXP3. Those mutations affect natural and induced regulatory T cells causing autoimmunity and immunodeficiency, but also enteropathy in a large percentage of patients and colitis111, 112. The intestinal lesions that develop in patients with IPEX can be classified as: graft-vs-host disease-like changes with small bowel involvement and colitis, celiac disease-like lesions, or enteropathy with goblet cell depletion113.

Antibodies against enterocytes and/or antibodies against goblet cells can be detected in the serum of IPEX patients113. IPEX-like immune dysregulation with enteropathy can also be caused by defects in IL2 signaling in patients with defects in the IL2 receptor α chain (IL2RA, encoding CD25)114, 115 or a dominant gain of function in STAT1 signaling116.

Other Disorder and Genes

IBD or IBD-like disorders have been described in patients with several other disorders. In some disorders there is no well-defined plausible functional mechanism. For example, patients with trichohepatoenteric syndrome have presumed defects in epithelial cells that lead to intractable diarrhea117, 118. However, an adaptive immune defect might also cause this disorder, because the patients have Ig deficiencies that require Ig substitution.

Several genes, described in supplement to Table 1, are associated with a single or less well-defined case report of patients who developed IBD-like features. Some of these patients might just happen to have intestinal inflammation by coincidence, and even several case reports cannot exclude a publication bias.

Heterozygous defects in the PTEN phosphatase are associated not only with multiple tumors but also immune dysregulation and autoimmunity119. Inflammatory polyps are common among patients with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome and indeterminate colitis, and ileitis is a rare complication119. The functional mechanism involved in intestinal inflammatory polyps and intestinal inflammation is not clear since heterozygous mutations in PTEN are not associated with conventional immunodeficiency and affect multiple cell types.

Very early-onset enteropathies and intestinal infections are described in several monogenic immunodeficiency and/or autoinflammation disorder including defects in the Itchy E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase activity encoded by ITCH gene, defects in E3 ubiquitin ligase HOIL-1 encoded by HOIL1, and gain of function defects in Nuclear Factor Of Kappa Light Polypeptide Gene Enhancer In B-Cells Inhibitor Alpha (IKBA) encoded by NFKBIA (supplemental information to Table 1). It is not clear what activates the inflammatory events in those patients; it could be pathogenic microbes in the intestine, food, or IBD-like intestinal inflammation induced by the commensal microbiota.

Additional disorders are associated with intestinal inflammation without an immunodeficiency or without known epithelial mechanisms. For example, some patients with Hirschsprung’s disease, an intestinal innervation and dysmotility disorder, develop enterocolitis associated with dominant germline mutations in RET120, 121. One possible pathomechanism could be increased bacterial translocation due to bacterial stasis leading to subsequent inflammation.

Despite multiple reports of complement system deficiencies and IBD, this group of disorders is not clearly defined. MASP2 deficiency has been reported in a patient with pediatric onset of IBD. However, reports of intestinal inflammation in several other complement defects are much harder to interpret since those patients present with inconsistent disease phenotypes, some are less-well documented, and could be simple chance findings, (see supplemental information to Table 1).

Why Should we Care about Monogenic Defects?

It is a challenge to diagnose the rare patients with monogenic IBD but differences in the prognosis and medical management argue that a genetic diagnosis should not be missed. As a group, these diseases have high morbidity and subgroups have high mortality if untreated. Based on their causes, some require different treatment strategies than most cases of IBD.

Allogeneic HSCT has been used to treat several monogenic disorders. It is the standard treatment for patients with disorders that do not respond to conventional treatment, those with high mortality, or those that increase susceptibility to hematopoietic cancers (e.g. IL10 signaling defects, IPEX syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, or increasingly XIAP deficiency). Introduction of HSCT as a potentially curative treatment option for intestinal and extra-intestinal manifestations in these disorders has changed clinical practice30, 73, 74, 107, 111.

However, there is evidence from mouse models and clinical studies that patients with epithelial barrier defects are less amenable to HSCT, since this does not correct the defect that causes the disease (e.g. NEMO deficiency or possibly TTC7A deficiency). For example, severe recurrence of multiple intestinal atresia after HSCT in patients with TTC7A deficiency36, 37 indicates a contribution of the enterocyte defect to pathogenesis. Due to the significant risk associated with HSCT, including graft-vs-host disease and severe infections, it is important to determine the genetic basis for each patient’s VEOIBD before selecting HSCT as a treatment approach.

Understanding the pathophysiology of a disorder caused by a genetic defect can identify unconventional biologic treatment options that interfere with specific pathogenic pathways. Patients with mevalonate kinase deficiency or CGD produce excess amounts of IL1β so treatment with IL1β receptor antagonists have been successful54, 55. This treatment is not part of the standard therapeutic repertoire for patients with conventional IBD. Access to individualized genotype specific therapies is particularly important, since it might avoid both surgery (including colectomy) and the side effects of medical therapy in patients who are unlikely to benefit from conventional IBD therapies in the long term.

A further incentive to establish a specific genetic diagnosis is the ability to anticipate complications. Some patients should be screened for infections (such for the EBV infection status in XIAP defects) or cancer (including B cell lymphomas in patients with IL10R deficiency,109 or skin and hematopoietic malignancies in Hoyeraal Hreidarsson Syndrome). Genetic information can also identify patients who should be screened for extra-intestinal manifestations such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, autoimmune neutropenia, or autoimmune hepatitis (Table 2). That knowledge of the genetic predisposition can reduce the time to detect associated complications.

Families who are aware of the genetic basis of their disease can receive genetic counseling.

When Should we Suspect Monogenic IBD?

The timely diagnosis of monogenic IBD requires assessments of intestinal and extra-intestinal disease phenotypes, in conjunction with the histopathology and appropriate laboratory tests to exclude allergies or infections18, 19. Classification of clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and imaging findings into CD-like and UC-like phenotype can be helpful, but is not sufficient to differentiate patients with monogenic disorder from conventional idiopathic CD (such as discontinuous, transmural inflammation affecting the entire gastrointestinal tract, fistulizing disease, or granuloma formation) or UC (a continuous, colonic disorder with crypt abscess formation and increases in chronic inflammatory cells, typically restricted to the lamina propria). Histopathologists use non-specific terms such as IBD-unclassified in a releveant proportion of patients with VEOIBD including monogenic forms of IBD. In the absence of highly specific and sensitive intestinal histologic markers of monogenic forms of IBD, extra-intestinal findings and laboratory test results are important factors to focus the search for monogenic forms of IBD (Table 3, figure 2). A phenotypic aide-memoire summarizing the key findings to ensure that a careful clinical history for VEOIBD and examination to narrow the search for an underlying monogenetic defect is YOUNG AGE MATTERS MOST (YOUNG AGE onset, Multiple family members and consanguinity, Autoimmunity, Thriving failure, Treatment with conventional medication fails, Endocrine concerns, Recurrent infections or unexplained fever, Severe perianal disease, Macrophage activation syndrome and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, Obstruction and atresia of intestine, Skin lesions and dental and hair abnormalities, and Tumors). An important component of management is to solicit advice from a specialist in VEOIBD.

Table 3.

Pivotal Prompts for Suspecting Monogenic IBD.

| Key points | Comments |

|---|---|

| Very early age of onset of IBD-like immunopathology | Likelihood increases with very early onset, particularly in those younger than 2 years of age at diagnosis |

| Family history | In particular consanguinity, predominance of affected males in families, or multiple family members affected |

| Atypical endoscopic or histological findings | For example, extreme epithelial apoptosis or loss of germinal centers |

| Resistance to conventional therapies | Such as exclusive enteral nutrition, corticosteroids, and/or biological therapy |

| Skin lesions, nail dystrophy, or hair abnormalities | For example, epidermolysis bullosa, eczema, folliculitis, pyoderma or abscesses, woolen hair, or trichorrhexis nodosa |

| Severe or very early onset perianal disease | Fistulas and abscesses |

| Lymphoid organ abnormalities | For example, lymph node abscesses, splenomegaly |

| Recurrent or atypical infections | Intestinal and nonintestinal |

| Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis | Induced by viral infections such as Epstein-Barr virus or cytomegalovirus or macrophage activation syndrome |

| Associated autoimmunity | For example, arthritis, serositis, sclerosing cholangitis, anemia, and endocrine dysfunction such as thyroiditis, type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| Early development of tumors | For example, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, skin tumors, hamartoma, thyroid tumors |

Figure 2. Diagnosis of VEOIBD.

Patient and family history, physical examination, endoscopic investigations, imaging as well as limited biochemistry and microbiology/virology tests are required to establish the diagnosis of IBD, assess disease localization and behavior, and determine inflammatory activity. If there is doubt, those tests can contribute to exclude the much more frequent gastrointestinal infections and non-IBD immune responses towards dietary antigens. Cow’s milk protein allergy can present with enteropathy and colitis and coeliac disease can mimic autoimmune enteropathies. Fecal calprotectin can be helpful but may be increased even in healthy infants. The current diagnostic strategy to investigate a monogenic cause of IBD-like intestinal inflammation is largely based on restricted functional screening followed by genetic confirmation. A restricted set of laboratory tests are needed to propose candidate genes of the most common genetic defects for subsequent limited sequencing. As a complementary approach, genetic screening for IBD-causative rare variants using next generation sequencing might be followed by limited functional confirmatory studies. The complexity of problems in these children requires an interdisciplinary support including pediatric gastroenterologists, immunologists, geneticists and infectious disease specialists.

CBC complete blood count, CRP C-reactive protein, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CMPA cows milk protein allergy.

Very early age of onset of intestinal symptoms and IBD-like endoscopic and histologic changes is a strong indicator for monogenic IBD as a group (Figure 1). However there are clear gene specific differences in the age of onset. The reported age of onset of IBD-like immunopathology in subgroups such as IL10 signaling defects, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, or IPEX is focused to infancy and early childhood. However atypical late-onset of IBD has been reported in patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome122, 123 as well as IPEX syndrome124–126. The age is very variable in neutrophil defects, B cell defects and XIAP deficiency. Indeed, XIAP deficiency caused by identical genetic defects within families can be associated with VEOIBD or adult-onset IBD68, 73,127. Other diseases, such as GUCY2C deficiency, typically develop during adulthood (Figure 1). Phenotypes of many monogenic forms of IBD change over time—gastrointestinal problems can present as an initial or a later finding.

Some candidate disorders will be recognized by their pathognomonic symptom combinations. Since there are no specific and fully reliable endoscopic and histological features of monogenic VEOIBD, patients with VEOIBD and multiple other features (that are listed in the table 3) should be considered to have increased likelihood to carry disease causing mutations. The degree of suspicion should dictate the extent of functional and genetic exploration for an underlying cause. It is important to emphasize that currently in the majority of patients with infantile IBD or VEOIBD disease no genetic defect can be discovered that would explain the immunopathology. This fraction of causative defects will increase as our knowledge expands, and with a growing a number of patients undergoing whole-exome sequencing (WES). Although young age of IBD disease onset is a strong indicator, a strong suspicion for a monogenic cause should lead to limited functional or genetics screening irrespective of age.

Laboratory Tests and Functional Screens

Laboratory tests, upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy with histologic analysis of multiple biopsies as well as imaging should be performed for every patient with VEOIBD according to guidelines13, 18–21, 128. Histological investigation is paramount, not only to differentiate IBD-like features, but also to exclude other established pathologies such eosinophilic or allergic gastrointestinal disease and infection.

Cow’s milk protein allergy is common and can cause severe colitis that resembles UC and and even requires hospitalization. It manifests typically within the first 2–3 months of exposure to cow’s milk protein. This may be apparent with breast-feeding or only after introducing formula feeding. Colitis resolves after cow’s milk is removed from the diet, so a trial of exclusive feeding with an amino-acid-based infant formula is a customary treatment strategy for all VEOIBD diagnosed when they are less than 1 year old. However, improvement of symptoms or inflammation does not exclude the possibility that a patient could have a monogenetic IBD disorder, because food intolerance and allergy can be secondary to the disorder and allergen avoidance by exclusive enteral nutrition with elemental formula could also alleviate the inflammation of classic IBD.

High levels of IgE and/or eosinophilia are also found in patients with monogenic disorders caused by defects in FOXP3, IL2RA, IKBKG, WAS, or DOCK8 (Table 2, supplemental table 1). It should also be standard practice to exclude infectious causes such as bacteria (Yersinia spp., Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Clostridium difficile), parasites (Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia) and viral infections (cytomegalovirus or HIV), remembering that some infections can mimic IBD. However, most of these pathogens do not cause bloody diarrhea for more than 2–3 weeks. In addition monogenic disorders (such as B or T cell defect immunodeficiencies or familial HLH type 5, caused by STXBP2 deficiency) predispose individuals to intestinal infections69. Celiac disease should be considered as a differential diagnosis for patients with suspected autoimmune enteropathy presenting with villous atrophy (such as IPEX or IPEX-like patients).

To detect possible causes of monogenic IBD-like immunopathology we propose additional laboratory screening for all children diagnosed before 6 years of age. The limited set of laboratory tests includes measurements of IgA, IgE, IgG, IgM; flow cytometry analysis of lymphocyte subsets (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19/CD20, NK cells); and analysis of oxidative burst by neutrophils (using the nitroblue tetrazolium test or flow cytometry-based assays such as the dihydrorhodamine fluorescence assay).

When placed in the context of clinical, histopathologic and radiological data, these tests can guide the diagnosis towards the more prevalent defects of neutrophil, B-, or T-cell dysfunction. Further tests are necessary to characterize particular subgroups, such as those who develop the disease when they are younger than 2 years old, those with excessive autoimmunity, or those with severe perianal disease. Those tests include flow cytometry analysis of XIAP expression by lymphocytes and NK cells129, 130 or FOXP3 expression in CD4+ T cells, which can diagnose a significant proportion of patients with XLP2 and IPEX. Flow cytometry can detect functional defects in MDP signaling in patients with XIAP deficiency131. IL10RA and IL10RB defects can be detected by assays that determine whether exogenous IL10 will suppress lipopolysaccharides (LPS) induced peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) cytokine secretion or IL10 induced STAT3 phosphorylation30, 103, 107. Increased levels of antibodies against enterocytes can indicate autoimmune enteropathy, in particular in patients with IPEX syndrome.

In contrast to measurements of Igs, flow cytometry and oxidative burst assays (which are largely standardized), other tests such as IL10 mediated suppression of LPS-induced PBMC activation, and detection of antibodies against enterocytes are non-routine assays. Similarly, additional tests for extremely rare genetic defects might be appropriate but are only available at specialized laboratories, often as part of research projects. The clinical utility of the algorithm to use a limited set of laboratory tests to differentiate between conventional and monogenic VEOIBD as suggested in figure 2 is based on experience, case reports and case series of individual disorders. It has not been validated in prospective studies of patients with all forms of VEOIBD.

Diagnosis via Sequencing of Candidate Genes vs Parallel Next Generation Sequencing

The classical approach to detect monogenic forms of IBD as described above and summarized in Figure 2, is based on careful phenotypic analysis and candidate sequencing to confirm a suspected genetic diagnosis. Due to the increasing number of candidate genes, sequential candidate sequencing can be costly and time consuming. It is therefore not surprising to propose that this strategy of functional screening followed by genetic confirmation will increasingly be complemented by early parallel genetic screening using next-generation sequencing followed by functional confirmation. The US Food and Drug Administration has recently granted marketing authorization for the first next-generation genomic sequencer, which will further pave the way for genome-, exome- or other targeted parallel genetic tests in routine practice132,133. WES or even whole-genome sequencing (WGS) will increasingly become part of the routine analysis of patients with suspected genetic disorders including subtypes of IBD59,134, 135. This has several important implications for selecting candidate gene lists, for identification of disease causing variants, and for dealing with a large number of genetic variants of unknown relevance. In research and clinical settings, WES has been shown reliably to detect genetic variants that cause VEOIBD, in genes such as XIAP67, IL10RA136, 137, G6PC3138, MEFV59, LRBA88, FOXP3126 and TTC7A38.

There are several reasons to propose extended parallel candidate sequencing for patients with suspected monogenic IBD. Immune and gastrointestinal phenotypes of patients evolve over time, whereas the diagnosis needs to be made at the initial presentation to avoid unnecessary tests and treatment. IBD-like immunopathology can be linked to non-classical phenotypes of known immunodeficiencies, such as hypomorphic genetic defects in SCID patients (in genes such as ZAP70, RAG2, IL2RG, LIG4, ADA, DCLRE1C, CD3G, or TTC7A; see Table 2) with residual B- and T-cell development81,82,38, or glucose-6-phosphatase 3 deficiency with lymphopenia50, or FOXP3 defects without the classical IPEX phenotype126. WES has revealed unexpected known causative variants67 even after work-up in centers with specialized immunological and genetic clinical and research facilities. This all demonstrates that current knowledge about the disease phenotype spectrum is incomplete which means that a pure candidate approach is not reliable and genetic screening may have advantages. The 50 monogenic defects associated with IBD provide an initial filter to identify patients with monogenic disorders.

Because of the greatly reduced costs of next-generation sequencing, it is probably cost effective in many cases to perform multiplex gene sequencing, WES or WGS rather than sequential Sanger-sequencing of multiple genes.

A big advantage of WES is the potential to identify novel causal genetic variants, once the initial candidate filter list of known disease causing candidates has been analyzed. The number of gene variants associated with VEOIBD is indeed constantly increasing largely due to the new sequencing technologies, so datasets derived from WES allow updated analysis of candidates as well as novel genes. Because multiple genetic defects can lead to spontaneous or induced colitis in mice1, 139, assuming homology, it is likely that many additional human gene variants will be associated with IBD.

Targeted sequencing of genes of interest is an alternative approach to exome-targeted sequencing. Initial studies to perform targeted next-generation parallel sequencing showed the potential power of this approach140. Targeted next-generation sequencing of the 170 PID-related genes accurately detected point mutations and exonic deletions140. Only 9/170 PID-related genes analyzed showed inadequate coverage. Four of 26 PID patients without established pre-screening genetic diagnosis, despite routine functional and genetic testing, were diagnosed, indicating the advantage of parallel genetic screening. Since a major group of VEOIBD-causing variants are associated with PID-related genes, it is obvious how this approach can be adapted and extended to monogenic IBD genes.

Genetic approaches also offer practical advantages. Specialized functional immune assays are often only available in research laboratories, and are not necessarily validated; functional tests often require rapid processing of PBMC or biopsies in specialized laboratories. This means that handling of DNA and sequencing seems far less prone to error or variation.

It should, however, be noted that relying solely on genetic screening can be misleading, since computational mutation prediction can fail to detect functional damaging variants. For example, variants in the protein-coding region of the IL10RA gene were misclassified as ‘tolerated’ by certain prediction tools, whereas other prediction tools and functional analysis reported defects in IL10 signaling30. Although most studies report variants in protein-coding regions in monogenic diseases, there could be selection bias. It is indeed far more difficult to establish the biologic effects of variants that affect processes such as splicing, gene expression, or mRNA stability. It should be without saying that novel genetic variants require appropriate functional validation.

Increased availability of sequencing datasets highlights the role of mutation-specific IBD-causing variants that illustrate the functional balance of gene products affected by gain or loss of function variants, as well as gene dosage effects. Inherited gain-of-function mutations in GUCY cause diarrhea and increase susceptibility to IBD, whereas loss-of-function mutations lead to intestinal obstruction and meconium ileus141. Gain-of-function mutations in STAT1 cause an IPEX-like syndrome with enteropathy,116 whereas loss-of-function mutations are found in patients with autosomal dominant chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis142. Loss of TTC7A activity results in multiple intestinal atresia and SCID36, 37, 143, whereas hypomorphic mutations cause VEOIBD38. Similarly, loss-of-function variants cause classical SCID defects, whereas hypomorphic variants in the same genes allow residual oligoclonal T-cell activation and are associated with immunopathology including colitis.

Performing next generation sequencing exome- or genomewide will identify (in each patient) genetic variants of unknown relevance, and in some patients known variants that are associated with incomplete penetrance or variable phenotype severity. Increasing use of DNA sequencing technologies will lead to detection of hypomorphic variants that cause milder phenotypes and/or later onset of IBD. The increased availability of genotype–phenotype datasets in databases such as ClinVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar)144 or commercial databases will increase our ability to differentiate variants that cause IBD from those without biologic effects. WES analysis of patients with paediatric onset of IBD, including VEOIBD, has revealed multiple rare genetic variants in those IBD susceptibility genes that were discovered by association studies145. Similarly, WES analysis of patients with genetically confirmed mevalonate kinase deficiency identified multiple variants in IBD-related genes outside of the MVK gene146. It is currenly not clear how strongly these rare variants influence the genetic susceptibility to IBD as additive or synergistic factors. In particular in patients with non-conventional forms of IBD the identification of variants of unknown relevance can lead to the therapeutic dilemma of whether to wait for the disease to progress or start early treatment. Since some of disease-specific treatment options have potentially severe side effects, careful evaluation of genetic variants is required not only to validate sequence data147 and statistical association but to provide functional evidence that those variants cause disease148,133.

Conclusion

Rare monogenic disorders that affect intestinal immune and epithelial function can lead to VEOIBD and severe phenotypes. These disorders are diagnosed based on clinical and genetic information. Accurate genetic diagnosis is required for assessing prognosis and proper treatment of patients. We summarized phenotypes and laboratory findings for more than 50 monogenic disorders and suggest diagnostic strategy to identify these extremely rare diseases, which have large effects on patients and their families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

A.M.M. is supported by an Early Researcher Award from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation and funded by a Canadian Institute of Health Research – Operating Grant (MOP119457). S.B.S is supported by NIH Grants HL59561, DK034854, and AI50950 and the Wolpow Family Chair in IBD Treatment and Research. CK is supported by DFG SFB1054, BaySysNet, and DZIF. This work was funded in part by a grant of the The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust to AMM, CK, and SBS. HHU is supported by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA).

TS is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SCHW1730/1-1).

The COLORS in IBD study group is funded by a grant of WTSI and by a Crohn’s and Colitis UK grant to the UK and Irish paediatric IBD genetics group and in part by a MRC grant for the PICTS study.

Abbreviations

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CGD

Chronic granulomatous disease

- CVID

combined variable immunodeficiency

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- IBD

inflammatory bowel syndrome

- IBDu

IBD unclassified

- IPEX

immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome

- PID

primary immunodeficiency

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- EOIBD

early onset IBD

- VEOIBD

very early onset IBD

- WGS

whole-genome sequencing

- WES

whole-exome sequencing

Footnotes

* for the COLORS in IBD study group and ** NEOPICS (www.NEOPICS.org)

Disclosure and Conflict of interest:

None of the authors has a conflict of interest related to this article.

HHU declares industrial project collaboration with Lilly, UCB Pharma and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Travel support was received from GSK foundation, Essex Pharma, Actelion, and MSD.

ST received consulting fees from AbbVie, Cosmo Technologies, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Santarus, Schering-Plough, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Sigmoid Pharma, Tillotts Pharma AG, UCB Pharma, Vifor, and Warner Chilcott UK; research grants from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma; and payments for lectures from AbbVie, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Sanofi, and Tillotts Pharma AG.

SK received in the past consulting or speaker’s fees from AbbVie, Danone, Janssen Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Merck, MSD, Nestlé Nutrition, Vifor and Weyth. Industrial project collaboration with Euroimmun, Eurospital, Inova, Mead Johnson, Phadia-ThermoFisher, and Nestlé Nutrition.

SBS received in the past consulting fees from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Talecris, Cubist, Ironwoods, Pfizer; speaking fees from UCB; research grants from Pfizer.

DT received consultation fee, research grant, royalties, or honorarium from MSD, Janssen, Shire, BMS, Hospital for Sick Children, and Abbott.

TS received speaker’s fees from MSD and travel support from Nestlé Nutrition.

NS serves the advisory board to Mead Johnson as COI and received a unrestricted educational grant from MSD.

DCW has received consultation fees, speaker’s fees, meeting attendance support or research support from MSD, Ferring, Falk, Pfizer and Nestle.

Author contribution: HHU, TS, JK, AE and JO screened literature and acquired systematic data on genetic defects. AMM, SK, NS, ST, DT, DW, SBS, and CK focused on subsets of patients, disease groups and diagnostic strategies. HHU drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors discussed and critically revised the manuscript.

References

- 1.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–17. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thapar N, Shah N, Ramsay AD, Lindley KJ, Milla PJ. Long-term outcome of intractable ulcerating enterocolitis of infancy. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2005;40:582–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000159622.88342.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruemmele FM, El Khoury MG, Talbotec C, Maurage C, Mougenot JF, Schmitz J, Goulet O. Characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease with onset during the first year of life. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2006;43:603–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000237938.12674.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyman MB, Kirschner BS, Gold BD, Ferry G, Baldassano R, Cohen SA, Winter HS, Fain P, King C, Smith T, El-Serag HB. Children with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): analysis of a pediatric IBD consortium registry. The Journal of pediatrics. 2005;146:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul T, Birnbaum A, Pal DK, Pittman N, Ceballos C, LeLeiko NS, Benkov K. Distinct phenotype of early childhood inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2006;40:583–6. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannioto Z, Berti I, Martelossi S, Bruno I, Giurici N, Crovella S, Ventura A. IBD and IBD mimicking enterocolitis in children younger than 2 years of age. European journal of pediatrics. 2009;168:149–55. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruel J, Ruane D, Mehandru S, Gower-Rousseau C, Colombel JF. IBD across the age spectrum-is it the same disease? Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014;11:88–98. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE, Aldhous MC, Round NK, Nimmo ER, Smith L, Gillett PM, McGrogan P, Weaver LT, Bisset WM, Mahdi G, Arnott ID, Satsangi J, Wilson DC. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1114–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams K, Thomson D, Seto I, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ioannidis JP, Curtis S, Constantin E, Batmanabane G, Hartling L, Klassen T. Standard 6: age groups for pediatric trials. Pediatrics. 2012;129(Suppl 3):S153–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0055I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, Jewell DP, Karban A, Loftus EV, Jr, Pena AS, Riddell RH, Sachar DB, Schreiber S, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Vermeire S, Warren BF. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie. 2005;19(Suppl A):5A–36A. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Wilson DC, Turner D, Russell RK, Fell J, Ruemmele FM, Walters T, Sherlock M, Dubinsky M, Hyams JS. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17:1314–21. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muise AM, Snapper SB, Kugathasan S. The age of gene discovery in very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:285–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Bie CI, Buderus S, Sandhu BK, de Ridder L, Paerregaard A, Veres G, Dias JA, Escher JC. Diagnostic workup of paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: results of a 5-year audit of the EUROKIDS registry. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2012;54:374–80. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318231d984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prenzel F, Uhlig HH. Frequency of indeterminate colitis in children and adults with IBD - a metaanalysis. Journal of Crohn’s & colitis. 2009;3:277–81. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ojuawo A, St Louis D, Lindley KJ, Milla PJ. Non-infective colitis in infancy: evidence in favour of minor immunodeficiency in its pathogenesis. Archives of disease in childhood. 1997;76:345–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.76.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, Escher JC, Cucchiara S, de Ridder L, Kolho KL, Veres G, Russell RK, Paerregaard A, Buderus S, Greer ML, Dias JA, Veereman-Wauters G, Lionetti P, Sladek M, Martin de Carpi J, Staiano A, Ruemmele FM, Wilson DC. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2014;58:795–806. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner D, Levine A, Escher JC, Griffiths AM, Russell RK, Dignass A, Dias JA, Bronsky J, Braegger CP, Cucchiara S, de Ridder L, Fagerberg UL, Hussey S, Hugot JP, Kolacek S, Kolho KL, Lionetti P, Paerregaard A, Potapov A, Rintala R, Serban DE, Staiano A, Sweeny B, Veerman G, Veres G, Wilson DC, Ruemmele FM. Management of pediatric ulcerative colitis: joint ECCO and ESPGHAN evidence-based consensus guidelines. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2012;55:340–61. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182662233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner D, Travis SP, Griffiths AM, Ruemmele FM, Levine A, Benchimol EI, Dubinsky M, Alex G, Baldassano RN, Langer JC, Shamberger R, Hyams JS, Cucchiara S, Bousvaros A, Escher JC, Markowitz J, Wilson DC, van Assche G, Russell RK. Consensus for managing acute severe ulcerative colitis in children: a systematic review and joint statement from ECCO, ESPGHAN, and the Porto IBD Working Group of ESPGHAN. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011;106:574–88. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, van der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M, Guslandi M, Oldenburg B, Dotan I, Marteau P, Ardizzone A, Baumgart DC, D’Haens G, Gionchetti P, Portela F, Vucelic B, Soderholm J, Escher J, Koletzko S, Kolho KL, Lukas M, Mottet C, Tilg H, Vermeire S, Carbonnel F, Cole A, Novacek G, Reinshagen M, Tsianos E, Herrlinger K, Bouhnik Y, Kiesslich R, Stange E, Travis S, Lindsay J. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Special situations. Journal of Crohn’s & colitis. 2010;4:63–101. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benchimol EI, Fortinsky KJ, Gozdyra P, Van den Heuvel M, Van Limbergen J, Griffiths AM. Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of international trends. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17:423–39. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson P, Hansen R, Cameron FL, Gerasimidis K, Rogers P, Bisset WM, Reynish EL, Drummond HE, Anderson NH, Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Satsangi J, Wilson DC. Rising incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Scotland. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2012;18:999–1005. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benchimol EI, Guttmann A, Griffiths AM, Rabeneck L, Mack DR, Brill H, Howard J, Guan J, To T. Increasing incidence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: evidence from health administrative data. Gut. 2009;58:1490–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.188383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benchimol EI, Mack DR, C NG, Snapper SB, Li W, Mojaverian N, Quach P, Muise AM. Incidence, outcomes, and health services burden of children with very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, Lee JC, Schumm LP, Sharma Y, Anderson CA, Essers J, Mitrovic M, Ning K, Cleynen I, Theatre E, Spain SL, Raychaudhuri S, Goyette P, Wei Z, Abraham C, Achkar JP, Ahmad T, Amininejad L, Ananthakrishnan AN, Andersen V, Andrews JM, Baidoo L, Balschun T, Bampton PA, Bitton A, Boucher G, Brand S, Buning C, Cohain A, Cichon S, D’Amato M, De Jong D, Devaney KL, Dubinsky M, Edwards C, Ellinghaus D, Ferguson LR, Franchimont D, Fransen K, Gearry R, Georges M, Gieger C, Glas J, Haritunians T, Hart A, Hawkey C, Hedl M, Hu X, Karlsen TH, Kupcinskas L, Kugathasan S, Latiano A, Laukens D, Lawrance IC, Lees CW, Louis E, Mahy G, Mansfield J, Morgan AR, Mowat C, Newman W, Palmieri O, Ponsioen CY, Potocnik U, Prescott NJ, Regueiro M, Rotter JI, Russell RK, Sanderson JD, Sans M, Satsangi J, Schreiber S, Simms LA, Sventoraityte J, Targan SR, Taylor KD, Tremelling M, Verspaget HW, De Vos M, Wijmenga C, Wilson DC, Winkelmann J, Xavier RJ, Zeissig S, Zhang B, Zhang CK, Zhao H, Silverberg MS, Annese V, Hakonarson H, Brant SR, Radford-Smith G, Mathew CG, Rioux JD, Schadt EE, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–24. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kugathasan S, Baldassano RN, Bradfield JP, Sleiman PM, Imielinski M, Guthery SL, Cucchiara S, Kim CE, Frackelton EC, Annaiah K, Glessner JT, Santa E, Willson T, Eckert AW, Bonkowski E, Shaner JL, Smith RM, Otieno FG, Peterson N, Abrams DJ, Chiavacci RM, Grundmeier R, Mamula P, Tomer G, Piccoli DA, Monos DS, Annese V, Denson LA, Grant SF, Hakonarson H. Loci on 20q13 and 21q22 are associated with pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nature genetics. 2008;40:1211–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imielinski M, Baldassano RN, Griffiths A, Russell RK, Annese V, Dubinsky M, Kugathasan S, Bradfield JP, Walters TD, Sleiman P, Kim CE, Muise A, Wang K, Glessner JT, Saeed S, Zhang H, Frackelton EC, Hou C, Flory JH, Otieno G, Chiavacci RM, Grundmeier R, Castro M, Latiano A, Dallapiccola B, Stempak J, Abrams DJ, Taylor K, McGovern D, Silber G, Wrobel I, Quiros A, Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, Cho JH, Duerr RH, Rioux JD, Brant SR, Silverberg MS, Taylor KD, Barmuda MM, Bitton A, Dassopoulos T, Datta LW, Green T, Griffiths AM, Kistner EO, Murtha MT, Regueiro MD, Rotter JI, Schumm LP, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Xavier RJ, Libioulle C, Sandor C, Lathrop M, Belaiche J, Dewit O, Gut I, Heath S, Laukens D, Mni M, Rutgeerts P, Van Gossum A, Zelenika D, Franchimont D, Hugot JP, de Vos M, Vermeire S, Louis E, Cardon LR, Anderson CA, Drummond H, Nimmo E, Ahmad T, Prescott NJ, Onnie CM, Fisher SA, Marchini J, Ghori J, Bumpstead S, Gwillam R, Tremelling M, Delukas P, Mansfield J, Jewell D, Satsangi J, Mathew CG, Parkes M, Georges M, Daly MJ, Heyman MB, Ferry GD, Kirschner B, Lee J, Essers J, Grand R, Stephens M, et al. Common variants at five new loci associated with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nature genetics. 2009;41:1335–40. doi: 10.1038/ng.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uhlig HH. Monogenic diseases associated with intestinal inflammation: implications for the understanding of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62:1795–805. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotlarz D, Beier R, Murugan D, Diestelhorst J, Jensen O, Boztug K, Pfeifer D, Kreipe H, Pfister ED, Baumann U, Puchalka J, Bohne J, Egritas O, Dalgic B, Kolho KL, Sauerbrey A, Buderus S, Gungor T, Enninger A, Koda YK, Guariso G, Weiss B, Corbacioglu S, Socha P, Uslu N, Metin A, Wahbeh GT, Husain K, Ramadan D, Al-Herz W, Grimbacher B, Sauer M, Sykora KW, Koletzko S, Klein C. Loss of interleukin-10 signaling and infantile inflammatory bowel disease: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:347–55. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeissig Y, Petersen BS, Milutinovic S, Bosse E, Mayr G, Peuker K, Hartwig J, Keller A, Kohl M, Laass MW, Billmann-Born S, Brandau H, Feller AC, Rocken C, Schrappe M, Rosenstiel P, Reed JC, Schreiber S, Franke A, Zeissig S. XIAP variants in male Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2014 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freeman EB, Koglmeier J, Martinez AE, Mellerio JE, Haynes L, Sebire NJ, Lindley KJ, Shah N. Gastrointestinal complications of epidermolysis bullosa in children. The British journal of dermatology. 2008;158:1308–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiskerstrand T, Arshad N, Haukanes BI, Tronstad RR, Pham KD, Johansson S, Havik B, Tonder SL, Levy SE, Brackman D, Boman H, Biswas KH, Apold J, Hovdenak N, Visweswariah SS, Knappskog PM. Familial diarrhea syndrome caused by an activating GUCY2C mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:1586–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng LE, Kanwar B, Tcheurekdjian H, Grenert JP, Muskat M, Heyman MB, McCune JM, Wara DW. Persistent systemic inflammation and atypical enterocolitis in patients with NEMO syndrome. Clinical immunology. 2009;132:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.03.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blaydon DC, Biancheri P, Di WL, Plagnol V, Cabral RM, Brooke MA, van Heel DA, Ruschendorf F, Toynbee M, Walne A, O’Toole EA, Martin JE, Lindley K, Vulliamy T, Abrams DJ, MacDonald TT, Harper JI, Kelsell DP. Inflammatory skin and bowel disease linked to ADAM17 deletion. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1502–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen R, Giliani S, Lanzi G, Mias GI, Lonardi S, Dobbs K, Manis J, Im H, Gallagher JE, Phanstiel DH, Euskirchen G, Lacroute P, Bettinger K, Moratto D, Weinacht K, Montin D, Gallo E, Mangili G, Porta F, Notarangelo LD, Pedretti S, Al-Herz W, Alfahdli W, Comeau AM, Traister RS, Pai SY, Carella G, Facchetti F, Nadeau KC, Snyder M. Whole-exome sequencing identifies tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7A (TTC7A) mutations for combined immunodeficiency with intestinal atresias. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2013;132:656–664 e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samuels ME, Majewski J, Alirezaie N, Fernandez I, Casals F, Patey N, Decaluwe H, Gosselin I, Haddad E, Hodgkinson A, Idaghdour Y, Marchand V, Michaud JL, Rodrigue MA, Desjardins S, Dubois S, Le Deist F, Awadalla P, Raymond V, Maranda B. Exome sequencing identifies mutations in the gene TTC7A in French-Canadian cases with hereditary multiple intestinal atresia. Journal of medical genetics. 2013;50:324–9. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avitzur Y, Guo C, Mastropaolo LA, Bahrami E, Chen H, Zhao Z, Elkadri A, Dhillon S, Murchie R, Fattouh R, Huynh H, Walker JL, Wales PW, Cutz E, Kakuta Y, Dudley J, Kammermeier J, Powrie F, Shah N, Walz C, Nathrath M, Kotlarz D, Puchaka J, Krieger J, Racek T, Kirchner T, Walters TD, Brumell JH, Griffiths AM, Rezaei N, Rashtian P, Najafi M, Monajemzadeh M, Pelsue S, McGovern DPB, Uhlig HH, Schadt E, Klein C, Snapper SB, Muise AM. Mutations in Tetratricopeptide Repeat Domain 7A Result in a Severe Form of Very Early Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2014 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schappi MG, Smith VV, Goldblatt D, Lindley KJ, Milla PJ. Colitis in chronic granulomatous disease. Archives of disease in childhood. 2001;84:147–51. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matute JD, Arias AA, Wright NA, Wrobel I, Waterhouse CC, Li XJ, Marchal CC, Stull ND, Lewis DB, Steele M, Kellner JD, Yu W, Meroueh SO, Nauseef WM, Dinauer MC. A new genetic subgroup of chronic granulomatous disease with autosomal recessive mutations in p40 phox and selective defects in neutrophil NADPH oxidase activity. Blood. 2009;114:3309–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Bousafy A, Al-Tubuly A, Dawi E, Zaroog S, Schulze I. Libyan Boy with Autosomal Recessive Trait (P22-phox Defect) of Chronic Granulomatous Disease. The Libyan journal of medicine. 2006;1:162–71. doi: 10.4176/060905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muise AM, Xu W, Guo CH, Walters TD, Wolters VM, Fattouh R, Lam GY, Hu P, Murchie R, Sherlock M, Gana JC, Russell RK, Glogauer M, Duerr RH, Cho JH, Lees CW, Satsangi J, Wilson DC, Paterson AD, Griffiths AM, Silverberg MS, Brumell JH. NADPH oxidase complex and IBD candidate gene studies: identification of a rare variant in NCF2 that results in reduced binding to RAC2. Gut. 2012;61:1028–35. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhillon SS, Fattouh R, Elkadri A, Xu W, Murchie R, Walters T, Guo C, Mack D, Huynh H, Baksh S, Silverberg M, Griffiths AM, Snapper S, Brumell JH, Muise AM. Variants in NADPH Oxidase Complex Components Determine Susceptibility to Very Early Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2014 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]