ABSTRACT

Hundreds of human proteins contain prion-like domains, which are a subset of low-complexity domains with high amino acid compositional similarity to yeast prion domains. A recently characterized mutation in the prion-like domain of the human heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein hnRNPA2B1 increases the aggregation propensity of the protein and causes multisystem proteinopathy. The mutant protein forms cytoplasmic inclusions when expressed in Drosophila, the mutation accelerates aggregation in vitro, and the mutant prion-like domain can substitute for a portion of a yeast prion domain in supporting prion activity. To examine the relationship between amino acid sequence and aggregation propensity, we made a diverse set of point mutations in the hnRNPA2B1 prion-like domain. We found that the effects on prion formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and aggregation in vitro could be predicted entirely based on amino acid composition. However, composition was an imperfect predictor of inclusion formation in Drosophila; while most mutations showed similar behaviors in yeast, in vitro, and in Drosophila, a few showed anomalous behavior. Collectively, these results demonstrate the significant progress that has been made in predicting the effects of mutations on intrinsic aggregation propensity while also highlighting the challenges of predicting the effects of mutations in more complex organisms.

KEYWORDS: aggregation, low-complexity domain, prion-like, prions

INTRODUCTION

Amyloid fibrils are ordered, self-propagating, β-sheet-rich protein aggregates (1, 2). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, numerous prions (infectious proteins) have been identified that result from the conversion of proteins to an infectious amyloid form (3, 4). Most of the yeast prion proteins contain low-complexity, glutamine/asparagine (Q/N)-rich prion domains (5). Hundreds of human proteins contain similar prion-like domains (PrLDs), defined as protein segments that compositionally resemble yeast prion domains (6, 7). PrLDs are a subset of low-complexity sequence domains (LCDs) that are found in about one-third of the human proteome and which are generally predicted to be intrinsically disordered (7, 8). PrLDs are particularly enriched in RNA binding proteins (7). Mutations in various PrLD-containing RNA binding proteins have been linked to degenerative disorders, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (7, 9).

A number of these PrLD-containing RNA binding proteins are components of RNA-protein granules, such as P-bodies and stress granules (9, 10), and the PrLDs are thought to mediate interactions that are involved in the formation of these granules (11–13). These PrLD-containing RNA binding proteins can form a range of assemblies, which differ in the degree of order in the structure and possibly in the nature of the underlying interactions (14–17). These range from highly dynamic liquid-liquid phase separations, in which liquid droplets are formed in a temperature- and concentration-dependent manner (14–16), to hydrogels, consisting of metastable amyloid-like fibers (17), to more stable, ordered amyloid aggregates (15, 16). Disease-associated mutations appear to specifically shift these proteins toward the amyloid state (15, 16, 18). This raises the intriguing hypothesis that these PrLDs evolved to mediate the weak, dynamic interactions involved in formation of dynamic RNA-protein granules, but disease-associated mutations promote conversion of the PrLDs to more stable structures (9, 10, 19).

The human heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein hnRNPA2B1 provides a useful model to examine this hypothesis. hnRNPA2B1 is a ubiquitously expressed RNA binding protein that has two alternatively spliced forms, A2 and B1, which differ by 12 amino acids at the N terminus. The shorter hnRNPA2 is the predominant isoform in most tissues. hnRNPA2B1 contains a PrLD (Fig. 1A), and a single point mutation (D290V in hnRNPA2) in this PrLD causes multisystem proteinopathy (18). Interestingly, mutations at the corresponding position of a paralogous heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein, hnRNPA1, can cause either multisystem proteinopathy or familial ALS (18). The mutations in both proteins promote incorporation into stress granules and in Drosophila cause formation of cytoplasmic inclusions. In vitro, the mutations accelerate formation of amyloid fibrils. In yeast, the core prion-like domain is able to support prion formation when inserted in the place of the portion of the prion domain of Sup35 that is responsible for nucleating prion formation (18, 20). Thus, hnRNPA2 provides a range of experimental systems to monitor the effects of mutations on protein aggregation.

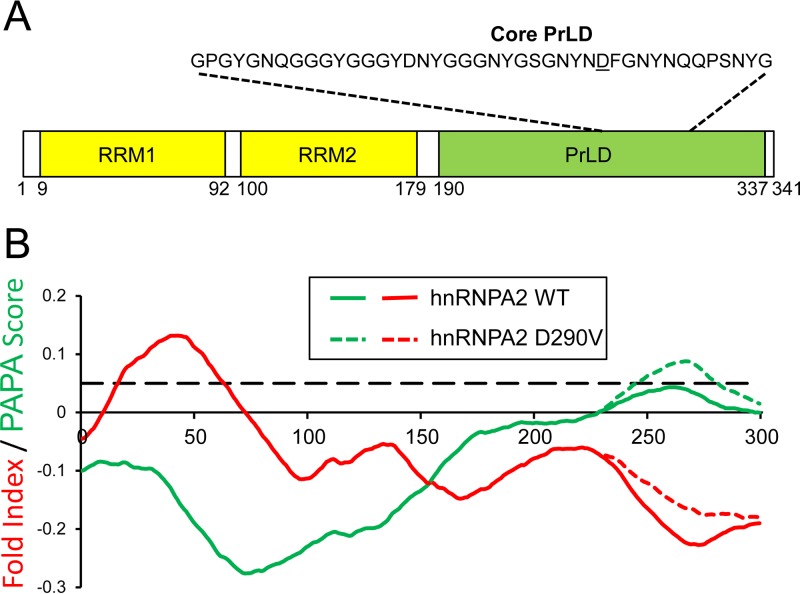

FIG 1.

hnRNPA2 contains a predicted prion-like domain. (A) Schematic of the hnRNPA2 domain architecture. (B) The disease-associated D290V mutation increases predicted prion propensity. PAPA scores (green) and FoldIndex scores (red) were calculated for hnRNPA2 wild type (WT) and D290V. The dashed line indicates a PAPA score of 0.05, the threshold that was most effective at separating prion-like domains with and without prion activity (23). Regions with high PAPA scores and negative FoldIndex scores are predicted to be prion prone. Adapted from the work of Kim et al. (18).

Intriguingly, PAPA and ZipperDB, two algorithms designed to predict amyloid or prion propensity, both correctly predict the effects of the three known disease-associated mutations in hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 (18). These results suggest that it might be possible to predict the effects of other mutations in these proteins and to rationally design mutations to alter aggregation propensity. However, this prediction success is currently based on a very small sample size: just one mutation in hnRNPA2 and two in hnRNPA1. Additionally, PAPA and ZipperDB use very different features to score aggregation propensity, so it is unclear which of these features is most predictive.

Specifically, PAPA was derived by replacing an 8-amino-acid segment from a scrambled version of Sup35 with a random sequence to build a library of mutants and then screening this library for prion formation (21). A prion propensity score was then derived for each amino acid by comparing its frequency among the prion-forming isolates relative to the starting library. PAPA predicts prion activity by first using FoldIndex (68) to identify regions of proteins that are predicted to be intrinsically disordered and then scanning these regions with a 41-amino-acid window size, adding up the prion propensity scores of each amino acid across the window (22, 23). In contrast, ZipperDB is a structure-based algorithm designed to look for short peptide fragments with a high propensity to form steric zippers (24). ZipperDB was developed by first solving the structure of a 6-amino-acid peptide from Sup35 in its amyloid conformation (25). The peptide was found to form a cross-β-sheet structure, with tight steric zipper interactions between the sheets. ZipperDB predicts amyloid propensity by threading 6-amino-acid peptides into this structure in silico and using Rosetta to determine the energetic fit.

Thus, PAPA solely considers amino acid composition and uses a large window size, while ZipperDB uses a much smaller window and is sensitive to primary sequence. Despite these differences, both accurately predicted the effects of the hnRNP mutations. PAPA predicts that the aggregation propensity of the wild-type hnRNPA2 PrLD falls just below the threshold for prion-like aggregation, while the mutation increases aggregation propensity well beyond this threshold (Fig. 1B). ZipperDB predicts that the disease-associated mutations should create a strong steric zipper (18).

In this study, to define the sequence features that drive aggregation, we designed a variety of mutations in the hnRNPA2 prion-like domain. Both in yeast and in vitro, the effects of mutations could be predicted entirely based on amino acid composition. In contrast, while the original disease-associated mutations created predicted steric zipper motifs, such motifs were neither necessary nor sufficient for aggregation in yeast. Although composition alone accurately predicted the effects of mutations on isolated prion-like domain fragments both in yeast and in vitro, it was less accurate at predicting their effects in the context of the full-length protein in Drosophila. This highlights a critical limitation of our current prediction methods. While these methods can predict the effects of mutations on intrinsic aggregation propensity, other factors (including interactions with other parts of the protein, interacting proteins, and localization) are currently much more challenging to predict.

RESULTS

Hydrophobic and aromatic residues promote aggregation.

We previously developed a yeast system to monitor the prion-like activity of hnRNPA2 (18). The [PSI+] prion is the prion form of the yeast translation termination factor Sup35 (26, 27). Sup35 has three functionally distinct domains: an N-terminal prion domain that is required for prion aggregation, a C-terminal functional domain that is necessary and sufficient for Sup35's normal function in translation termination, and a highly charged middle domain that is not required for either prion formation or Sup35's translation termination activity but which stabilizes prion fibers (Fig. 2A) (28–30). Yeast prion domains are generally modular, meaning that they maintain prion activity when attached to other proteins (31). Because simple assays are available to detect [PSI+] prion formation, substitution of the prion domain of Sup35 with fragments from other prion-like proteins has been widely used to probe for prion activity (32–34). The first 40 amino acids of the Sup35 prion domain are required for prion formation, while the remainder of the prion domain, which is composed of a series of imperfect oligopeptide repeats, is predominantly involved in prion maintenance (Fig. 2A) (20, 35, 36). Therefore, substitution of fragments in the place of the first 40 amino acids of Sup35 can be used to probe aggregation propensity of these domains and to examine the effects of mutation on aggregation propensity (20). The core PrLDs from mutant hnRNPA2 can support prion activity when substituted for the first 40 amino acids of Sup35, while the wild-type prion domain cannot (18). Thus, these fusion proteins provide a convenient system for examining how amino acid sequence affects PrLD aggregation propensity.

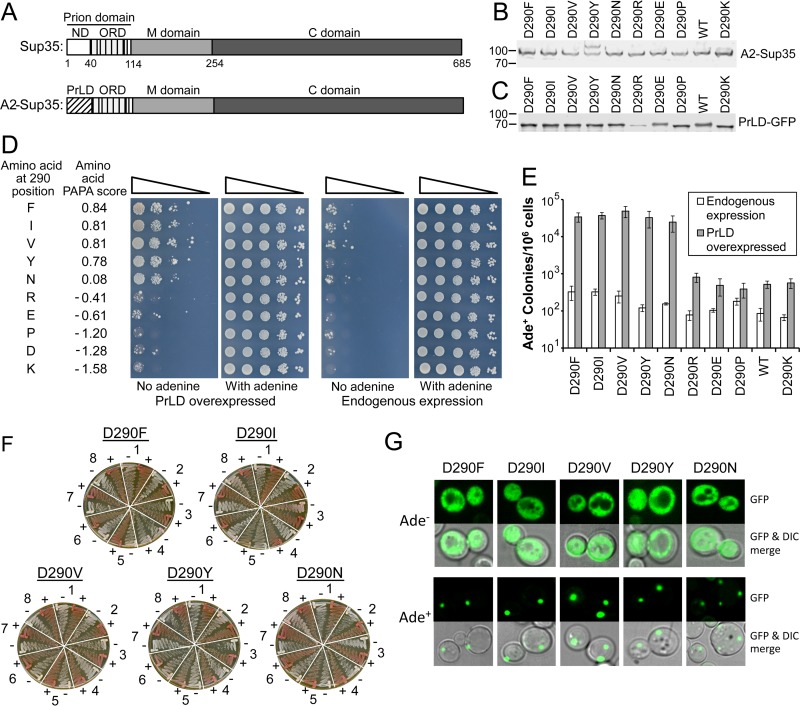

FIG 2.

PAPA accurately predicts prion-promoting mutations at the 290 position. (A) Schematic of wild-type Sup35 and the hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimeric protein (18). Sup35 contains three domains: an N-terminal prion domain, a highly charged middle (M) domain, and a C-terminal domain that is responsible for Sup35's translation termination function. The prion domain contains two parts: a nucleation domain (ND) that is required for prion formation and an oligopeptide repeat domain (ORD) that is dispensable for prion nucleation but is required for prion propagation. In the hnRNPA2-Sup35 fusion, the ND (amino acids 3 to 40) of Sup35 was replaced with the core PrLD (amino acids 261 to 303) from hnRNPA2B1. (B) Western blot analysis of endogenous expression of full-length wild-type (WT) and mutant hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimeric proteins, using an antibody to the Sup35 C-terminal domain. (C) Western blot analysis of overexpression of PrLD-GFP fusions, using an antibody to GFP. The NM domain of each hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimera was fused to GFP and expressed from the GAL1 promoter. (D) Effects of different amino acids at the D290 position. [psi−] strains were generated that expressed hnRNPA2-Sup35 fusion proteins with the indicated substitution at the D290 position as the sole copy of Sup35 in the cell. The strains were transformed with either an empty vector (endogenous expression) or a plasmid expressing the matching PrLD-GFP mutant under the control of the GAL1 promoter (PrLD overexpression). Cells were grown in galactose dropout medium for 3 days, and then 10-fold serial dilutions were plated onto medium lacking adenine to select for [PSI+] and medium containing adenine to test for cell viability. PAPA scores for each amino acid are indicated. The wild type (D290) and D290V were previously reported (18). (E) Quantification of Ade+ colony formation. Serial dilutions of the galactose cultures from panel D were plated onto full plates containing medium with and without adenine. The frequency of Ade+ colony formation was determined as the ratio of colonies formed with and without adenine. Data represent means ± SDs (n ≥ 3). (F) Curability of Ade+ colonies. For each mutant, eight individual Ade+ isolates were grown on YPD (−) or YPD plus 4 mM guanidine HCl (+). Cells were then restreaked onto YPD to test for loss of the Ade+ phenotype. (G) The Ade+ phenotype is associated with protein aggregation. For the indicated mutants, Ade− and Ade+ cells were transformed with a plasmid expressing the matching PrLD-GFP mutant under the control of the GAL1 promoter. Cells were grown for 1 h in galactose dropout medium and visualized by confocal microscopy.

The prion prediction algorithm PAPA predicts that within PrLDs, charged amino acids and proline should strongly inhibit prion formation, while aromatic and hydrophobic amino acids promote prion formation (37, 38). The disease-associated mutations in hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 each involve replacement of a strongly prion-inhibiting amino acid (aspartic acid) with a neutral (asparagine) or prion-promoting (valine) amino acid. We therefore hypothesized that replacing the aspartic acid with any predicted prion-promoting amino acid would have a similar effect.

To test this hypothesis, we replaced the aspartic acid at the disease-associated position in hnRNPA2 with predicted prion-promoting amino acids (phenylalanine, isoleucine, and tyrosine), a prion-neutral amino acid (asparagine), and prion-inhibiting amino acids (arginine, glutamic acid, proline, or lysine). We tested these mutations in the hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimeric protein (Fig. 2A). [PSI+] prion formation can be assayed by monitoring nonsense suppression of ade2-1 allele (39). ade2-1 mutants are unable to grow in the absence of adenine and turn red on limited adenine due accumulation of a pigment derived from the substrate of the Ade2 protein. In [PSI+] cells, Sup35 is sequestered into prion aggregates, resulting in occasional readthrough of the ade2-1 premature stop codon; therefore, [PSI+] cells are able to grow in the absence of adenine, and they form white or pink colonies on limiting adenine. One hallmark of prion activity is that increasing protein concentration should increase the frequency of prion formation (27). We therefore monitored the frequency of Ade+ colony formation with and without overexpression of the matching prion domain fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP).

The full-length fusions showed only modest differences in protein expression, although the D290Y mutant showed two bands, suggesting a possible posttranslational modification (Fig. 2B). Likewise, all of the PrLD-GFP fusions, except the one from the D290R mutant, showed similar levels of overexpression (Fig. 2C). The single point mutations had profound effects on Ade+ colony formation, with the mutants showing differences of multiple orders of magnitude upon PrLD overexpression (Fig. 2D and E). Strikingly, there was a strong correlation between the predicted effect of each mutation and the observed frequency of Ade+ colony formation. Each mutation predicted to enhance prion activity (D290F, -I, -V, -Y, and -N) showed statistically significant increases in Ade+ colony formation upon PrLD overexpression (P < 0.001 by t test) relative to the wild-type fusion.

Ade+ colony formation can result from either prion formation or from a nonsense suppressor mutation. For each of the prion-promoting mutations (D290F, -I, -V, -Y, and -N), the fact that the frequency of Ade+ colony formation showed an increase of multiple orders of magnitude upon PrLD overexpression strongly suggests that the Ade+ phenotype is a result of prion formation, as the frequency of DNA mutation should be insensitive to expression levels (27). Two assays were used to further confirm that these mutants formed prions. First, we tested whether the Ade+ phenotype could be cured by low concentrations of guanidine hydrochloride. Guanidine hydrochloride cures [PSI+] (40) by inhibiting Hsp104 (41, 42). For the D290F, -I, -V, -Y, and -N mutants, almost all tested Ade+ colonies formed upon PrLD overexpression maintained a white phenotype in the absence of guanidine hydrochloride but turned red after treatment with guanidine hydrochloride (Fig. 2F), consistent with the Ade+ phenotype resulting from prion formation. In contrast, none of the tested Ade+ colonies formed by the wild-type fusion protein and the D290R, -E, and -P mutants were curable by guanidine hydrochloride (data not shown), suggesting that the Ade+ phenotype is likely a result of DNA mutation. The D290K mutant did have a small number of stable, curable Ade+ colonies, although these occurred less frequently than for any of the aggregation-promoting mutations (data not shown). Second, we used a GFP assay (43) to confirm that the fusion proteins were aggregated in curable Ade+ cells. When Sup35N-GFP is transiently overexpressed in [psi−] cells, it initially shows diffuse cytoplasmic localization; in contrast, in [PSI+] cells, Sup35N-GFP rapidly joins existing prion aggregates and coalesces into foci (43). Therefore, to test for the presence of prion aggregates, we transiently overexpressed PrLD-GFP fusions in Ade+ and Ade− cells for each predicted prion-promoting mutant. In the Ade− cells, the GFP fusions remained diffuse, while in Ade+ cells the fusions rapidly coalesced into foci (Fig. 2G).

Additive and compensatory mutations.

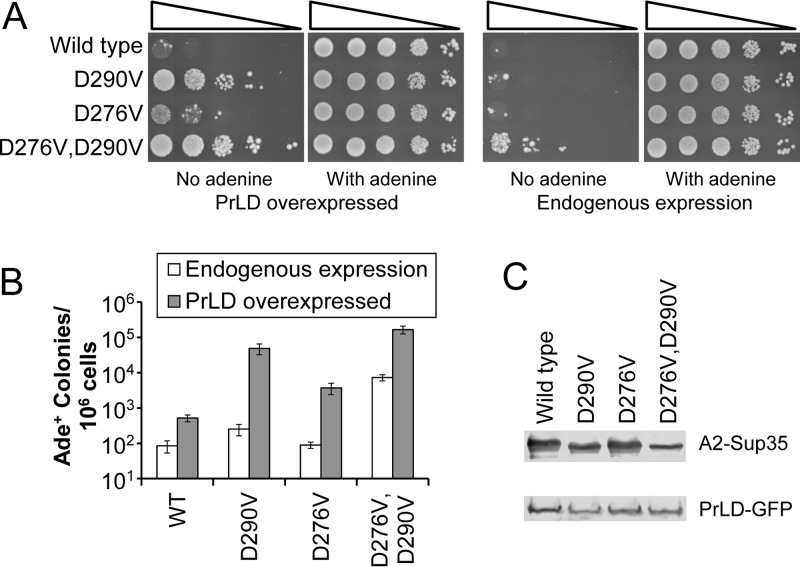

Each of the disease-associated mutations in hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 targets a highly conserved aspartic acid within a motif that is conserved across much of the hnRNPA/B family (18), suggesting that this position is may be a critical determinant of aggregation propensity; however, composition-based algorithms like PAPA predict that there is nothing unique about this specific aspartic acid and that similar mutations at other positions should exert a similar effect. The hnRNPA2 PrLD contains very few predicted prion-inhibiting amino acids, but a second aspartic acid is found at amino acid 276 (Fig. 1). An aspartic acid-to-valine change at this position also promoted Ade+ colony formation, although to a lesser extent than the disease-associated mutations (Fig. 3A and B). Additionally, combining mutations at both positions had an additive effect, generating a mutant that formed Ade+ colonies efficiently even in the absence of PrLD overexpression (Fig. 3A and B). For both the D276V mutant and the double mutant, the majority of Ade+ colonies formed upon PrLD overexpression were curable by guanidine hydrochloride, consistent with prion formation (data not shown). The strong additive effect of the mutations was not due to differences in protein expression; the double mutant actually had slightly lower levels of expression for the full-length hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimeric protein, and its PrLD-GFP fusion showed levels of expression similar to those of the wild-type and D290V mutant (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Additive mutations. (A) The indicated hnRNPA2-Sup35 mutants were tested for prion formation. D276V enhances Ade+ colony formation, albeit less than the D290V mutation. The D276V D290V double mutant shows substantially higher levels of Ade+ colony formation than the D290V mutant alone, even forming Ade+ colonies in the absence of PrLD overexpression. (B) Quantification of Ade+ colony formation. Data represent means ± SDs (n ≥ 3). (C) Western blot analysis of endogenous expression of full-length hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimeric proteins and overexpression of PrLD-GFP fusions.

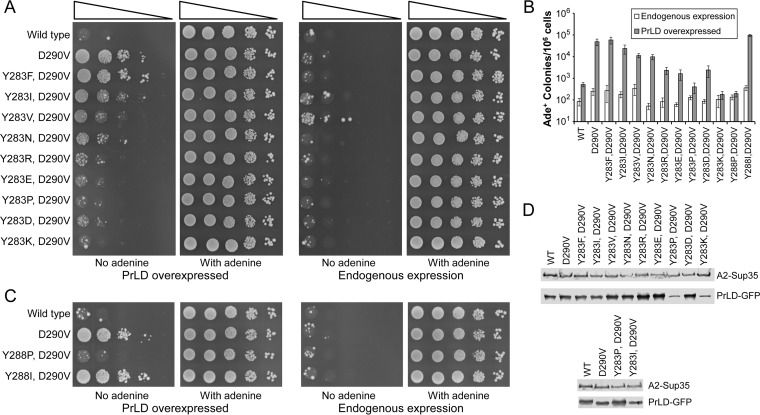

PAPA also predicts that it should also be possible to design compensatory mutations that offset the effects of the disease-associated mutations. Tyrosines are predicted to be strongly prion promoting (38). As predicted, replacing Y283 with various prion-inhibiting amino acids (R, E, P, D, and K) partially or completely offset the effects of the D290V mutation, while replacing this tyrosine with other prion-promoting amino acids had little effect (Fig. 4A and B). Similar results were seen with a more limited panel of mutants at a second position (Y288 [Fig. 4C]). For each of the mutants in which Y was replaced with a prion-promoting amino acid, the majority of Ade+ colonies formed upon PrLD overexpression were curable by guanidine hydrochloride, consistent with prion formation (data not shown). Y283 and Y288 mutants showed only modest differences in expression of the full-length hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimeras, although two of the Y283 mutants (Y283P and Y283K) showed lower levels of PrLD-GFP overexpression (Fig. 4D), potentially explaining why these two mutations showed the strongest aggregation-inhibiting effects.

FIG 4.

Compensatory mutations. (A) Prion-inhibiting mutations effectively offset the effects of the D290V mutation. Y283 in the hnRNPA2-Sup35 (D290V) fusion was replaced with either other prion-promoting amino acids (F, I, and V), a neutral amino acid (N), or prion-inhibiting amino acids (R, E, P, D, and K). Each of the predicted prion-inhibiting amino acids partially or completely reversed the effects of the D290V mutation. (B) Quantification of Ade+ colony formation. Data represent means ± SDs (n ≥ 3). (C) Y288 in the hnRNPA2-Sup35 (D290V) fusion was replaced with either a prion-inhibiting proline or a prion-promoting isoleucine. (D) Western blot analysis of endogenous expression of full-length hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimeric proteins and overexpression of PrLD-GFP fusions.

Zipper segments are neither necessary nor sufficient for prion aggregation.

Each of the disease-associated mutations in hnRNPA2B1 and -A1 are predicted by ZipperDB to create strong steric zipper segments (Fig. 5A and B) (18). Each of the prion-promoting residues tested in the experiment shown in Fig. 2 are likewise predicted to create strong zipper segments, so it is unclear whether the mutations enhance prion formation solely because of compositional effects or due to creation of a steric zipper. The presence of a strong zipper segment is clearly not sufficient for prion formation, as the compensatory mutations in Fig. 4A prevent prion formation without disrupting the predicted zipper segment (Fig. 5C and data not shown).

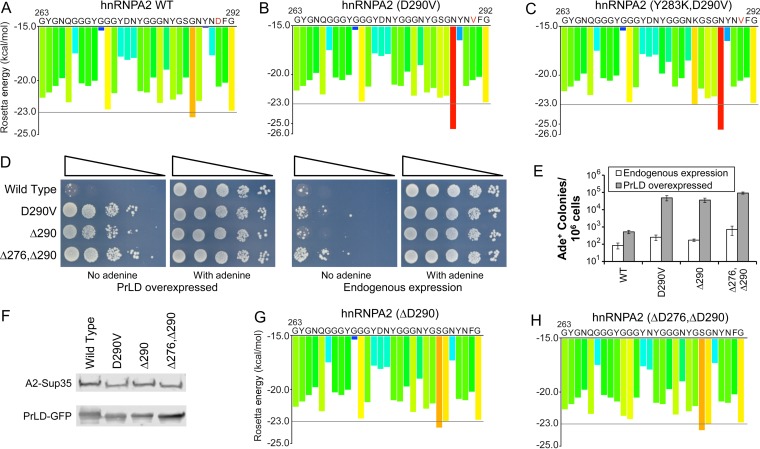

FIG 5.

Predicted strong steric zipper segments are neither necessary nor sufficient for prion activity. (A and B) ZipperDB analysis (24) of the core PrLDs of hnRNPA2 wild type and D290V mutant. Segments with a Rosetta energy below −23.0 kcal/mol are predicted to form steric zippers. The D290V mutation creates a strong predicted steric zipper segment from amino acids 287 to 292. The remainder of the core PrLD is not scored by ZipperDB due to the presence of prolines at positions 262 and 298. Adapted from the work of Kim et al. (18). (C) The Y283K mutation blocks prion formation by the hnRNPA2-Sup35 (D290V) mutant (Fig. 4) but does not affect the predicted strong steric zipper segment. (D) Both ΔD290 and a ΔD276 ΔD290 double mutant substantially increase Ade+ colony formation by the hnRNPA2-Sup35 fusion. (E) Quantification of Ade+ colony formation. Data represent means ± SDs (n ≥ 3). (F) Western blot analysis of endogenous expression of full-length hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimeric proteins and overexpression of PrLD-GFP fusions. (G and H) Neither the ΔD290 nor ΔD276 ΔD290 mutations are predicted to create a strong steric zipper.

We designed additional mutations to test whether zipper segments are necessary for prion formation by the hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimera. Because aspartic acid is predicted by PAPA to be strongly prion inhibiting, deletion of aspartic acid is predicted to enhance prion activity. Indeed, deletion of one or both aspartic acids in the core A2 PrLDs strongly enhanced Ade+ colony formation by the fusion proteins (Fig. 5D and E), and the majority of Ade+ colonies formed upon PrLD overexpression for these mutants were curable by guanidine hydrochloride. This effect is not due to differences in expression level; the ΔD290 mutant showed levels of expression similar to those of the wild type for both the full-length hnRNPA2-Sup35 chimera and the PrLD-GFP fusion (Fig. 5F), and although the double deletion showed modestly higher PrLD-GFP overexpression, this difference would be unlikely to explain the multiple-order-of-magnitude increase in Ade+ colony formation relative to the wild-type protein (Fig. 5F). However, although they substantially increased prion formation, neither of these mutations is predicted to create a strong steric zipper segment (Fig. 5G and H), indicating that strong zipper segments are neither necessary (Fig. 5D to H) or sufficient (Fig. 5C) for prion-like protein aggregation.

Effects of mutations in Drosophila.

For each of the mutations tested in yeast, prion activity closely correlated with PAPA predictions. Because hnRNPA2(D290V) primarily causes myopathy in humans (18), we were interested in whether our yeast results could accurately predict myopathy in a multicellular organism. Expression of aggregation-prone prion or prion-like proteins in muscle tissue of various model systems can cause muscle disorganization (18, 44, 45). We previously showed that when expressed in Drosophila, wild-type hnRNPA2 localizes to the nucleus and is predominantly detergent soluble, whereas hnRNPA2(D290V) forms cytoplasmic inclusions, is largely detergent insoluble, and leads to muscle degeneration (Fig. 6) (18). Similar results were obtained with two other antibodies: DP3B3 with untagged hnRNPA2 and anti-Flag antibody with Flag-tagged hnRNPA2 (data not shown). The cytoplasmic inclusions formed by hnRNPA2(D290V) are RNA granule assemblies, containing various RNA binding proteins (46).

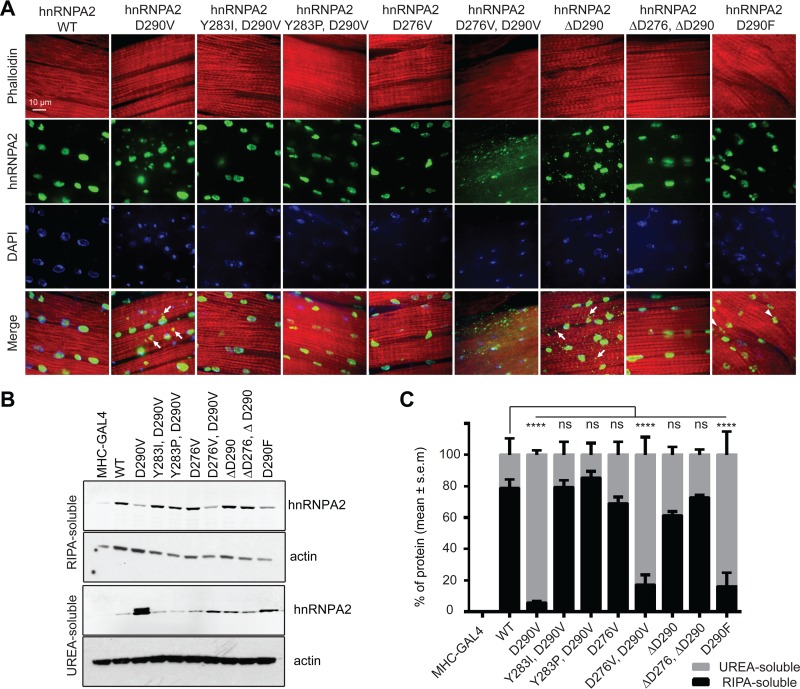

FIG 6.

Effects of mutations in Drosophila. (A) Adult fly thoraces were stained with anti-hnRNPA2B1 (green), Texas Red-X phalloidin (red), and DAPI (blue). Wild-type hnRNPA2 localizes exclusively to the nuclei, whereas the D290V mutant also forms cytoplasmic foci. The other mutants show a range of localization patterns, including much more substantial cytoplasmic foci for the D276V D290V double mutant. Examples of cytoplasmic and nuclear foci are indicated with arrows and arrowheads, respectively. (B) Thoraces of adult flies were dissected and sequential extractions were performed to examine the solubility profile of hnRNPA2. (C) Quantification of the blot shown in panel B. Data represent means ± SEMs (n = 3). ****, P < 0.0001 (two-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] with Bonferroni's post hoc test. ns, not significant.

To test whether other predicted prion-promoting mutations at the 290 position would also increase insolubility and promote formation of cytoplasmic foci, we expressed hnRNPA2(D290F) in Drosophila. While there was less radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer-insoluble (urea-soluble) protein for hnRNPA2(D290F) than for hnRNPA2(D290V) (Fig. 6B), hnRNPA2(D290F) was nevertheless largely RIPA buffer insoluble (Fig. 6C); interestingly, it predominantly formed nuclear foci rather than the cytoplasmic foci seen for hnRNPA2(D290V) (Fig. 6A).

To test whether mutations at other sites would mimic the D290V mutation, we expressed the hnRNPA2(D276V) and the hnRNPA2(D276V,D290V) mutants. As in yeast, the D276V mutation had a smaller effect than the D290V mutation. D276V slightly increased the fraction of detergent-insoluble protein compared to wild-type hnRNPA2, although this increase was not statistically significant (Fig. 6C). As in yeast, the double mutant had a strongly additive effect. The fraction of insoluble protein was actually slightly lower than for the hnRNPA2(D290V), likely because hnRNPA2(D290V) had higher protein levels and was already almost entirely insoluble (Fig. 6C); however, the double mutant had a much more dramatic immunohistological phenotype, with many small foci throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 6A). Additionally, it showed clear disruption of muscle fibers, seen as a loss of the regular striations normally observed with phalloidin staining of healthy muscle (Fig. 6A).

Two of the mutations showed different behavior in yeast and Drosophila. As expected, the predicted prion-inhibiting Y283P mutation largely offset the effect of the D290V mutation, restoring solubility and nuclear localization (Fig. 6). However, the control Y283I mutation, which had little effect in yeast (Fig. 4A), also offset the effect of the D290V mutation in Drosophila (Fig. 6). As in yeast, the ΔD290 mutation decreased the solubility of the protein in Drosophila, albeit not statistically significantly (Fig. 6C), and caused formation of cytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 6A); however, the hnRNPA2(ΔD276,ΔD290) double mutant actually appeared to be more soluble.

One other striking difference was observed between hnRNPA2(D290V) and all other mutants tested: only hnRNPA2(D290V) showed two bands on the Western blot, likely reflecting an uncharacterized posttranslational modification. The significance of this second band is unclear; given that it was not observed in the hnRNPA2(D276V,D290V) double mutant, clearly it is not required for insolubility, mislocalization, or muscle pathology.

In vitro analysis of mutants.

Prediction algorithms like PAPA are generally designed to predict the intrinsic aggregation propensity of peptides or proteins. However, mutations can influence aggregation by affecting activities other than intrinsic aggregation propensity, including altering interactions with other cellular factors or with other parts of the protein, changing expression levels or protein stability, or altering localization. For the mutants that showed divergent behavior in yeast and Drosophila, we hypothesized that this divergent behavior likely reflected effects of the mutation beyond intrinsic aggregation propensity. To test this hypothesis, we utilized an in vitro aggregation assay to examine the intrinsic aggregation propensity of these mutants in the absence of other cellular factors.

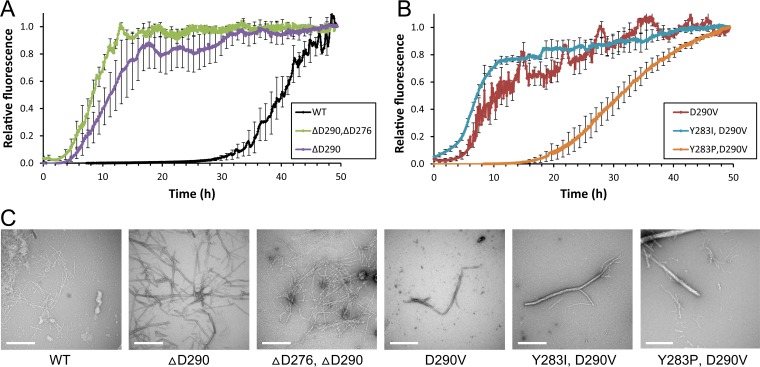

We generated 35-amino-acid peptides from the core PrLDs. We tested each for amyloid aggregation using thioflavin T, a dye that fluoresces upon interaction with amyloid fibrils but not soluble proteins or amorphous aggregates (47). Most amyloid-forming proteins show sigmodal aggregation kinetics, with a lag time followed by a growth phase in which there is a rapid increase in aggregation and then a plateau as soluble material is exhausted. For each protein where the yeast and Drosophila results diverged, the in vitro aggregation kinetics mimicked the yeast results and PAPA predictions; higher frequencies of prion formation in yeast correlated with shorter lag times and a steeper growth phase. Specifically, the wild-type protein showed very slow aggregation kinetics, with a lag time of approximately 25 h (Fig. 7A). The D290V mutation substantially accelerated aggregation, shortening the lag phase to about 4 h (Fig. 7B). The ΔD290 likewise showed accelerated aggregation, which was further enhanced in the ΔD276/ΔD290 double mutant (Fig. 7A). The Y283P mutant was largely able to offset the aggregation promoting effect of D290V, while the more conservative Y283I mutation had little effect (Fig. 7B). In all cases, the increase in thioflavin T signal was associated with fiber formation (Fig. 7C).

FIG 7.

In vitro amyloid formation by hnRNPA2 mutants. (A and B) Synthetic 35-amino-acid peptides from the hnRNPA2 core PrLD were generated with the indicated mutations. Peptides were resuspended under denaturing conditions and then diluted to initiate amyloid formation. Reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature with intermittent shaking. Amyloid formation was monitored by thioflavin T fluorescence. Data represent means ± SEMs, with error bars shown for every 10th data point; n = 3. (C) Electron micrographs of amyloid formation assays after 48 h. Scale bars, 500 nm.

Collectively, these results indicate that both the PAPA prediction algorithm and yeast fusion system can accurately predict the effects of mutations on the intrinsic aggregation propensity of peptides, but that intrinsic aggregation propensity is an imperfect predictor of in vivo aggregation of the peptides in the context of their respective full-length proteins.

DISCUSSION

Although prion formation in humans is generally thought of as pathogenic, an emerging theory suggests that many prion-like domains may have evolved to form weak or transient interactions that mediate the formation of membraneless organelles (9). For example, P bodies and stress granules are two types of RNA-protein assemblies that regulate translation and mRNA turnover. The prion-like domain of TIA-1 helps mediate the formation of stress granules (12), and in yeast, the prion-like domain of Lsm4 is involved in P body formation (11). This suggests the intriguing hypothesis that mutations may cause disease by disrupting the dynamics of these assemblies.

However, the exact relationship between PrLD aggregation propensity and disease is unclear. The cytoplasmic inclusions seen for disease-associated hnRNPA2B1 and -A1 mutations are not just simple aggregates of these proteins but instead are RNA granules (46). Therefore, these are complex structures that are normally under regulatory control, so it is unclear whether simple increases in aggregation propensity are sufficient to cause disease. Examining this question is challenging, as our understanding of these diseases is currently based on a limited set of mutations. For example, only one disease-associated mutation has been characterized for hnRNPA2B1. Furthermore, targeted mutations to investigate the role of PrLD aggregation in protein function and pathology have often involved dramatic changes to protein sequence, such as deletion or replacement of the entire PrLD, so these mutations likely have effects beyond just changing aggregation propensity.

In contrast, we were able to cause profound changes in the aggregation propensity of hnRNPA2 with just single or double point mutations. This ability to rationally design more subtle mutations to alter aggregation propensity will provide a powerful tool to explore the role of PrLDs in functional and pathological aggregation. While not all mutations behaved as expected in Drosophila in the context of full-length hnRNPA2, most did, suggesting that it is relatively simple to design mutations to modulate aggregation propensity. This will facilitate experiments both to explore the normal role of functional aggregation and to test whether increasing aggregation propensity disrupts the dynamics of these aggregates and leads to disease.

Our success rate in predicting prion aggregation in yeast was surprising. We designed 13 mutations expected to increase prion formation relative to the wild-type hnRNPA2-Sup35 fusion (D290F, -I, -Y, and -N; D290V paired with Y283F, -I, -V, or -N; D290V paired with Y288I; D276V; D276V D290V; ΔD290; and ΔD276 ΔD290) and 10 mutations expected to decrease prion activity relative to the D290V mutant (D290R, -E, -P, and -K; D290V paired with Y283R, -E, -P, -D, and -K; and D290V paired with Y288P). Numerous factors could have affected Ade+ colony formation in our assay: our mutants showed subtle differences in protein expression, which influences prion formation; for wild-type Sup35, many prions formed are toxic to cells (48), so the fraction of toxic prions for a given mutant would affect Ade+ colony formation; the assay may not detect weak, poorly propagating prions; and interactions with other cellular proteins may influence prion activity. Despite all of these potentially confounding factors, we accurately predicted the direction of the effect relative to the wild-type or D290V reference for all 23 mutations tested. Although the strength of the effect of each mutation was not perfectly predictable, this remarkable prediction success despite the limitations of the assay demonstrates that even single point mutations can have a profound effect on aggregation propensity.

Nevertheless, our experiments also highlight remaining challenges for predicting the effects of mutations. In the past decade, mutations in numerous PrLD-containing RNA binding proteins, including FUS (49, 50), TDP-43 (51), TAF15 (52), EWSR1 (53), hnRNPDL (54), hnRNPA1 (18), and hnRNPA2 (18), have been linked to various degenerative diseases. While some algorithms have proven successful at identifying the PrLDs in these proteins (7), predicting the effects of mutations has proven more difficult (6, 7). One issue is that while mutations in these proteins appear to cause disease by disrupting RNA homeostasis, increasing the aggregation propensity of these RNA binding proteins is just one of many mechanisms by which RNA homeostasis could be disrupted. For example, for TDP-43, a subset of disease-associated mutations do not cause a detectable increase in aggregation propensity (55). Likewise, for FUS and hnRNPA1, some of the disease-associated mutations are found in a predicted nuclear localization signal (56, 57), so they may lead to the formation of cytoplasmic inclusions by disrupting nuclear localization rather than directly increasing aggregation propensity.

Our results suggest an additional challenge in predicting the effects of mutations: while we clearly have made substantial strides in predicting the effects of mutations on the aggregation propensity of isolated PrLDs, this was an imperfect predictor of focus formation by the full-length protein in Drosophila. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear. For natively folded proteins, native state stability can be a critical determinant of aggregation propensity (58), so the intrinsic aggregation propensity of a protein (i.e., the propensity of the protein to form aggregates from a denatured state) is an imperfect predictor of the aggregation propensity of the native protein. However, the hnRNPA2 PrLD is predicted to be intrinsically disordered, so native state stability should be less of an issue. For a disordered protein, other factors, including changes in localization, interactions with other proteins or nucleic acids, posttranslational modifications, or expression levels, could indirectly affect aggregation propensity. Because RNA granule formation is a highly regulated process, interactions of a mutation with the normal regulatory machinery may influence the effect of a mutation, potentially resulting in the observed disconnect between intrinsic aggregation propensity and observed focus formation and insolubility in cells. Examining these outliers may ultimately provide a more complete understanding of the factors that affect pathological protein aggregation. Furthermore, it remains to be determined whether intrinsic aggregation propensity (in yeast and in vitro) or focus formation in Drosophila is more predictive of disease.

These experiments also highlight the risk of using small isolated peptides to examine aggregation propensity. This was seen at two levels: as discussed above, the peptides tested in vitro and in yeast were imperfect predictors of the behavior of full-length proteins, and ZipperDB, which was developed from analysis of 6-amino-acid peptides, was an imperfect predictor of longer ∼35-amino-acid peptides. ZipperDB utilizes structure-based prediction, threading sequences into the crystal structure of a 6-amino-acid peptide in an amyloid-like conformation (24). There are two main types of interactions that stabilize the structure: in-register parallel β-sheet interactions that run the length of the amyloid fibril and steric zipper packing interactions between β-sheets. Because the structure is based on a 6-amino-acid peptide, the predicted steric zipper interactions are intermolecular, between two identical peptides. Therefore, when ZipperDB predicts the ability to form steric zippers, it is essentially predicting self-complementarity of a peptide. However, in the context of longer peptides, steric zipper interactions may be intramolecular, between different segments of a single peptide (59). Such intramolecular zippers are seen in a recent high-resolution structure of amyloid β-fibers (60, 61). These intramolecular zippers are currently not predicted by ZipperDB, potentially explaining why it inaccurately predicts some of the peptides here. However, it should be noted that while strong predicted zipper segments were clearly not sufficient for efficient aggregation in yeast (Fig. 4 and 5), in Drosophila (Fig. 6), or in vitro (Fig. 7), whether they are necessary in Drosophila is less clear. The high aggregation propensity of the ΔD276 ΔD290 double mutant in vitro (Fig. 7) and in yeast (Fig. 5) clearly shows that a strong predicted steric zipper is not necessary in these contexts; however, this double mutant showed low aggregation propensity in Drosophila (Fig. 6), so we cannot rule out the possibility that a strong zipper segment is important in the context of the full-length protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and media.

Standard yeast media and methods were as previously described (62). All experiments were performed with strain YER635/pJ533 (α kar1-1 SUQ5 ade2-1 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 ppq1::HIS3 sup35::KanMx [63]). pJ533 (URA3) expresses SUP35 from the SUP35 promoter. Yeasts were grown at 30°C for all experiments.

Prion formation in yeast.

Plasmids pER599 and pER600 (cen LEU2) expressing wild-type and D290V hnRNPA2-Sup35 fusions, respectively, were previously described (18). All additional mutations were made by PCR and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmids were transformed into YER635/pJ533, selected on medium lacking leucine, and then transferred to 5-fluoroorotic-acid-containing medium to select for loss of pJ533.

To construct plasmids to transiently overexpress the PrLDs fused to GFP, the NM domain (the prion domain, plus the adjacent middle domain [Fig. 2A]) of each hnRNPA2-Sup35 fusion was amplified with oligonucleotides EDR1624 (GAGCTACTGGATCCACAATGTCAGGACCTGGATATGGCAACCAG) and EDR1924 (GTCGATGCTACTCGAGTCGTTAACAACTTCGTCATCCACTTC). The resulting PCR products were digested with BamHI and XhoI and inserted into BamHI/XhoI-cut pER760, a TRP1 plasmid that contains GFP under the control of the GAL1 promoter (37).

Prion formation assays were performed as previously described (64). Briefly, cells expressing a given hnRNPA2-Sup35 fusion as the sole copy of Sup35 were transformed with either an empty vector (pKT24 [65]) or a plasmid expressing the matching PrLD-GFP fusion under the control of the GAL1 promoter. Cells were grown for 3 days in galactose-raffinose dropout medium lacking tryptophan. Tenfold serial dilutions were then plated onto synthetic complete medium lacking adenine to select for [PSI+] cells and onto medium with adenine to test for cell viability.

Western blotting.

To probe PrLD-GFP expression levels in yeast, TRP1 plasmids expressing the PrLD-GFP fusion were transformed into the corresponding mutant strain. Low-density cultures were pregrown in raffinose dropout medium overnight, diluted to an optical density (OD) of 1.0 in 10 ml of 3% galactose-raffinose dropout medium, and grown for 4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were lysed as previously described (66), with protease inhibitor cocktail (Gold Biotechnology) included in the lysis buffer. Lysates were normalized based on total protein concentration, as determined by Bradford assay (Sigma). Proteins were separated on SDS–12% PAGE gels, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and immunoblotted using a monoclonal anti-GPF primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Alexa Fluor IR800–goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Rockland).

To probe endogenous expression levels, log-phase cultures were harvested by centrifugation, and cells were lysed as described above. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody against the Sup35C domain (BE4 [67] from Cocalico Biologicals, kindly made available by Susan Liebman) as the primary antibody, and Alexa Fluor IR800–goat anti-mouse (Rockland) as the secondary antibody.

Fly stocks and culture.

Mutagenesis using the QuikChange Lightning kit (Agilent) was performed on the pUASTattB-wild type hnRNPA2 construct as previously described (18). Flies carrying transgenes in pUASTattB vectors were generated by performing a standard injection and φC31 integrase-mediated transgenesis technique (BestGene Inc.). To express a transgene in muscles, Mhc-Gal4 (from G. Marqués) was used. All Drosophila stocks were maintained in a 25°C incubator with a 12-h day/night cycle and a standard diet.

Preparation of adult fly muscle for immunofluorescence.

Adult flies were embedded in a drop of OCT compound (Sakura Finetek) on a glass slide, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and bisected sagittally by using a razor blade. After being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fly tissues were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100, and indiscriminant binding was blocked by adding 5% normal goat serum in PBS. The hemithoraces were stained with anti-hnRNPA2B1 (EF-67) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen), Texas Red-X phalloidin (Invitrogen), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Stained hemithoraces were mounted in 80% glycerol, and the muscles were imaged with a Marianas confocal microscope (Zeiss; ×63).

Fly thorax fractionation protocol.

The thoraces of at least 15 adult flies were dissected, homogenized in RIPA buffer, and lysed on ice for 15 min. The cell lysates were sonicated and then cleared by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to generate the RIPA buffer-soluble samples. To prevent carryovers, the resulting pellets were washed with RIPA buffer. RIPA buffer-insoluble pellets were then extracted with urea buffer {7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate [CHAPS], 30 mM Tris [pH 8.5]}, sonicated, and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min at 22°C. Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce), and samples were boiled for 5 min and analyzed by the standard Western blotting method provided by the Odyssey system (Li-Cor) with a 4 to 12% NuPAGE bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen), anti-hnRNPA2B1 (DP3B3) antibody (Abcam; 1:2,000), and antiactin antibody (Santa Cruz; 1:10,000).

In vitro aggregation assays.

A 96-well plate was treated with 5% casein solution for 5 min at room temperature, then rinsed with deionized water, and allowed to dry. Synthetic peptides (GenScript) were dissolved at 2.5 mM in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. Peptides were then diluted approximately 100-fold to a final concentration of 25 μM in 10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 12.5 μM thioflavin T, and 0.02% casein (pH 7.4) in the 96-well plate to initiate aggregation. Fluorescence was monitored in a Victor3 PerkinElmer fluorescence plate reader, with excitation and emission wavelengths of 460 and 490 nm, respectively. Reactions were monitored for 48 h. Between readings, reaction mixtures were incubated without agitation for 3 min and then shaken for 10 s. The fraction aggregated was calculated by normalization relative to the final fluorescence of the well.

For electron microscopy of in vitro aggregation reactions, 10 to 20 μl of sample was incubated on carbon copper grids for 5 min and then rinsed with distilled water. Grids were stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 30 s and observed on a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope; imaging was done with a Gatan Orius 832 camera.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (MCB-1517231) and National Institutes of Health (GM105991) to E.D.R. and NIH grant R35NS097974 to J.P.T. The microscopes used for the yeast work and electron microscopy are supported by the Microscope Imaging Network core infrastructure grant from Colorado State University.

We thank Kim Vanderpool for assistance with electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kisilevsky R, Fraser PE. 1997. A beta amyloidogenesis: unique, or variation on a systemic theme? Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 32:361–404. doi: 10.3109/10409239709082674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sipe JD, Cohen AS. 2000. Review: history of the amyloid fibril. J Struct Biol 130:88–98. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liebman SW, Chernoff YO. 2012. Prions in yeast. Genetics 191:1041–1072. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wickner RB, Shewmaker FP, Bateman DA, Edskes HK, Gorkovskiy A, Dayani Y, Bezsonov EE. 2015. Yeast prions: structure, biology, and prion-handling systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 79:1–17. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00041-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du Z. 2011. The complexity and implications of yeast prion domains. Prion 5:311–316. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.4.18304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cascarina SM, Ross ED. 2014. Yeast prions and human prion-like proteins: sequence features and prediction methods. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:2047–2063. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1543-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King OD, Gitler AD, Shorter J. 2012. The tip of the iceberg: RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains in neurodegenerative disease. Brain Res 1462:61–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. 2014. Intrinsically disordered proteins and intrinsically disordered protein regions. Annu Rev Biochem 83:553–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-164947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramaswami M, Taylor JP, Parker R. 2013. Altered ribostasis: RNA-protein granules in degenerative disorders. Cell 154:727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolozin B. 2012. Regulated protein aggregation: stress granules and neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener 7:56. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decker CJ, Teixeira D, Parker R. 2007. Edc3p and a glutamine/asparagine-rich domain of Lsm4p function in processing body assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 179:437–449. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilks N, Kedersha N, Ayodele M, Shen L, Stoecklin G, Dember LM, Anderson P. 2004. Stress granule assembly is mediated by prion-like aggregation of TIA-1. Mol Biol Cell 15:5383–5398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reijns MA, Alexander RD, Spiller MP, Beggs JD. 2008. A role for Q/N-rich aggregation-prone regions in P-body localization. J Cell Sci 121:2463–2472. doi: 10.1242/jcs.024976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Y, Protter DS, Rosen MK, Parker R. 2015. Formation and maturation of phase-separated liquid droplets by RNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell 60:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molliex A, Temirov J, Lee J, Coughlin M, Kanagaraj AP, Kim HJ, Mittag T, Taylor JP. 2015. Phase separation by low complexity domains promotes stress granule assembly and drives pathological fibrillization. Cell 163:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel A, Lee HO, Jawerth L, Maharana S, Jahnel M, Hein MY, Stoynov S, Mahamid J, Saha S, Franzmann TM, Pozniakovski A, Poser I, Maghelli N, Royer LA, Weigert M, Myers EW, Grill S, Drechsel D, Hyman AA, Alberti S. 2015. A liquid-to-solid phase transition of the ALS protein FUS accelerated by disease mutation. Cell 162:1066–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato M, Han TW, Xie S, Shi K, Du X, Wu LC, Mirzaei H, Goldsmith EJ, Longgood J, Pei J, Grishin NV, Frantz DE, Schneider JW, Chen S, Li L, Sawaya MR, Eisenberg D, Tycko R, McKnight SL. 2012. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: low complexity sequence domains form dynamic fibers within hydrogels. Cell 149:753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HJ, Kim NC, Wang YD, Scarborough EA, Moore J, Diaz Z, MacLea KS, Freibaum B, Li S, Molliex A, Kanagaraj AP, Carter R, Boylan KB, Wojtas AM, Rademakers R, Pinkus JL, Greenberg SA, Trojanowski JQ, Traynor BJ, Smith BN, Topp S, Gkazi AS, Miller J, Shaw CE, Kottlors M, Kirschner J, Pestronk A, Li YR, Ford AF, Gitler AD, Benatar M, King OD, Kimonis VE, Ross ED, Weihl CC, Shorter J, Taylor JP. 2013. Mutations in prion-like domains in hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 cause multisystem proteinopathy and ALS. Nature 495:467–473. doi: 10.1038/nature11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.March ZM, King OD, Shorter J. 2016. Prion-like domains as epigenetic regulators, scaffolds for subcellular organization, and drivers of neurodegenerative disease. Brain Res 1647:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osherovich LZ, Cox BS, Tuite MF, Weissman JS. 2004. Dissection and design of yeast prions. PLoS Biol 2:E86. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toombs JA, McCarty BR, Ross ED. 2010. Compositional determinants of prion formation in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 30:319–332. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01140-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross ED, Maclea KS, Anderson C, Ben-Hur A. 2013. A bioinformatics method for identifying Q/N-rich prion-like domains in proteins. Methods Mol Biol 1017:219–228. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-438-8_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toombs JA, Petri M, Paul KR, Kan GY, Ben-Hur A, Ross ED. 2012. De novo design of synthetic prion domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:6519–6524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119366109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldschmidt L, Teng PK, Riek R, Eisenberg D. 2010. Identifying the amylome, proteins capable of forming amyloid-like fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:3487–3492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915166107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson R, Sawaya MR, Balbirnie M, Madsen AO, Riekel C, Grothe R, Eisenberg D. 2005. Structure of the cross-beta spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature 435:773–778. doi: 10.1038/nature03680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chernoff YO, Lindquist SL, Ono B, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. 1995. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [psi+]. Science 268:880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wickner RB. 1994. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 264:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu JJ, Sondheimer N, Lindquist SL. 2002. Changes in the middle region of Sup35 profoundly alter the nature of epigenetic inheritance for the yeast prion [PSI+]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99(Suppl 4):S16446–S16453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ter-Avanesyan MD, Dagkesamanskaya AR, Kushnirov VV, Smirnov VN. 1994. The SUP35 omnipotent suppressor gene is involved in the maintenance of the non-Mendelian determinant [psi+] in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 137:671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ter-Avanesyan MD, Kushnirov VV, Dagkesamanskaya AR, Didichenko SA, Chernoff YO, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Smirnov VN. 1993. Deletion analysis of the SUP35 gene of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals two non-overlapping functional regions in the encoded protein. Mol Microbiol 7:683–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Lindquist S. 2000. Creating a protein-based element of inheritance. Science 287:661–664. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. 2009. A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell 137:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osherovich LZ, Weissman JS. 2001. Multiple Gln/Asn-rich prion domains confer susceptibility to induction of the yeast [PSI(+)] prion. Cell 106:183–194. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sondheimer N, Lindquist S. 2000. Rnq1: an epigenetic modifier of protein function in yeast. Mol Cell 5:163–172. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DePace AH, Santoso A, Hillner P, Weissman JS. 1998. A critical role for amino-terminal glutamine/asparagine repeats in the formation and propagation of a yeast prion. Cell 93:1241–1252. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toombs JA, Liss NM, Cobble KR, Ben-Musa Z, Ross ED. 2011. [PSI+] maintenance is dependent on the composition, not primary sequence, of the oligopeptide repeat domain. PLoS One 6:e21953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez Nelson AC, Paul KR, Petri M, Flores N, Rogge RA, Cascarina SM, Ross ED. 2014. Increasing prion propensity by hydrophobic insertion. PLoS One 9:e89286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross ED, Toombs JA. 2010. The effects of amino acid composition on yeast prion formation and prion domain interactions. Prion 4:60–65. doi: 10.4161/pri.4.2.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cox BS. 1965. PSI, a cytoplasmic suppressor of super-suppressor in yeast. Heredity 20:505–521. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuite MF, Mundy CR, Cox BS. 1981. Agents that cause a high frequency of genetic change from [psi+] to [psi-] in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 98:691–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferreira PC, Ness F, Edwards SR, Cox BS, Tuite MF. 2001. The elimination of the yeast [PSI+] prion by guanidine hydrochloride is the result of Hsp104 inactivation. Mol Microbiol 40:1357–1369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung G, Masison DC. 2001. Guanidine hydrochloride inhibits Hsp104 activity in vivo: a possible explanation for its effect in curing yeast prions. Curr Microbiol 43:7–10. doi: 10.1007/s002840010251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patino MM, Liu JJ, Glover JR, Lindquist S. 1996. Support for the prion hypothesis for inheritance of a phenotypic trait in yeast. Science 273:622–626. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park KW, Li L. 2008. Cytoplasmic expression of mouse prion protein causes severe toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 372:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nussbaum-Krammer CI, Park KW, Li L, Melki R, Morimoto RI. 2013. Spreading of a prion domain from cell-to-cell by vesicular transport in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 9:e1003351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li S, Zhang P, Freibaum BD, Kim NC, Kolaitis RM, Molliex A, Kanagaraj AP, Yabe I, Tanino M, Tanaka S, Sasaki H, Ross ED, Taylor JP, Kim HJ. 2016. Genetic interaction of hnRNPA2B1 and DNAJB6 in a Drosophila model of multisystem proteinopathy. Hum Mol Genet 25:936–950. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LeVine H., III 1999. Quantification of beta-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol 309:274–284. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGlinchey RP, Kryndushkin D, Wickner RB. 2011. Suicidal [PSI+] is a lethal yeast prion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:5337–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102762108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwiatkowski TJ Jr, Bosco DA, Leclerc AL, Tamrazian E, Vanderburg CR, Russ C, Davis A, Gilchrist J, Kasarskis EJ, Munsat T, Valdmanis P, Rouleau GA, Hosler BA, Cortelli P, de Jong PJ, Yoshinaga Y, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Yan J, Ticozzi N, Siddique T, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PC, Horvitz HR, Landers JE, Brown RH Jr. 2009. Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 323:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vance C, Rogelj B, Hortobagyi T, De Vos KJ, Nishimura AL, Sreedharan J, Hu X, Smith B, Ruddy D, Wright P, Ganesalingam J, Williams KL, Tripathi V, Al-Saraj S, Al-Chalabi A, Leigh PN, Blair IP, Nicholson G, de Belleroche J, Gallo JM, Miller CC, Shaw CE. 2009. Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science 323:1208–1211. doi: 10.1126/science.1165942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, McCluskey LF, Miller BL, Masliah E, Mackenzie IR, Feldman H, Feiden W, Kretzschmar HA, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. 2006. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Couthouis J, Hart MP, Shorter J, Dejesus-Hernandez M, Erion R, Oristano R, Liu AX, Ramos D, Jethava N, Hosangadi D, Epstein J, Chiang A, Diaz Z, Nakaya T, Ibrahim F, Kim HJ, Solski JA, Williams KL, Mojsilovic-Petrovic J, Ingre C, Boylan K, Graff-Radford NR, Dickson DW, Clay-Falcone D, Elman L, McCluskey L, Greene R, Kalb RG, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Ludolph A, Robberecht W, Andersen PM, Nicholson GA, Blair IP, King OD, Bonini NM, Van Deerlin V, Rademakers R, Mourelatos Z, Gitler AD. 2011. A yeast functional screen predicts new candidate ALS disease genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:20881–20890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109434108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Couthouis J, Hart MP, Erion R, King OD, Diaz Z, Nakaya T, Ibrahim F, Kim HJ, Mojsilovic-Petrovic J, Panossian S, Kim CE, Frackelton EC, Solski JA, Williams KL, Clay-Falcone D, Elman L, McCluskey L, Greene R, Hakonarson H, Kalb RG, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Nicholson GA, Blair IP, Bonini NM, Van Deerlin VM, Mourelatos Z, Shorter J, Gitler AD. 2012. Evaluating the role of the FUS/TLS-related gene EWSR1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 21:2899–2911. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vieira NM, Naslavsky MS, Licinio L, Kok F, Schlesinger D, Vainzof M, Sanchez N, Kitajima JP, Gal L, Cavacana N, Serafini PR, Chuartzman S, Vasquez C, Mimbacas A, Nigro V, Pavanello RC, Schuldiner M, Kunkel LM, Zatz M. 2014. A defect in the RNA-processing protein HNRPDL causes limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 1G (LGMD1G). Hum Mol Genet 23:4103–4110. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson BS, Snead D, Lee JJ, McCaffery JM, Shorter J, Gitler AD. 2009. TDP-43 is intrinsically aggregation-prone, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutations accelerate aggregation and increase toxicity. J Biol Chem 284:20329–20339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Da Cruz S, Cleveland DW. 2011. Understanding the role of TDP-43 and FUS/TLS in ALS and beyond. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21:904–919. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Q, Shu S, Wang RR, Liu F, Cui B, Guo XN, Lu CX, Li XG, Liu MS, Peng B, Cui LY, Zhang X. 2016. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a missense mutation in hnRNPA1 in a family with flail arm ALS. Neurology 87:1763–1769. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelly JW. 1998. The alternative conformations of amyloidogenic proteins and their multi-step assembly pathways. Curr Opin Struct Biol 8:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paul KR, Ross ED. 2015. Controlling the prion propensity of glutamine/asparagine-rich proteins. Prion 9:347–354. doi: 10.1080/19336896.2015.1111506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eisenberg DS, Sawaya MR. 2016. Implications for Alzheimer's disease of an atomic resolution structure of amyloid-beta(1-42) fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:9398–9400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610806113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wälti MA, Ravotti F, Arai H, Glabe CG, Wall JS, Bockmann A, Guntert P, Meier BH, Riek R. 2016. Atomic-resolution structure of a disease-relevant Abeta(1-42) amyloid fibril. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E4976–E4984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600749113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sherman F. 1991. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol 194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.MacLea KS, Paul KR, Ben-Musa Z, Waechter A, Shattuck JE, Gruca M, Ross ED. 2015. Distinct amino acid compositional requirements for formation and maintenance of the [PSI(+)] prion in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 35:899–911. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01020-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paul KR, Hendrich CG, Waechter A, Harman MR, Ross ED. 2015. Generating new prions by targeted mutation or segment duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:8584–8589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501072112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ross ED, Edskes HK, Terry MJ, Wickner RB. 2005. Primary sequence independence for prion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:12825–12830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fredrickson EK, Gallagher PS, Clowes Candadai SV, Gardner RG. 2013. Substrate recognition in nuclear protein quality control degradation is governed by exposed hydrophobicity that correlates with aggregation and insolubility. J Biol Chem 288:6130–6139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.406710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bagriantsev SN, Kushnirov VV, Liebman SW. 2006. Analysis of amyloid aggregates using agarose gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol 412:33–48. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)12003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prilusky J, Felder CE, Zeev-Ben-Mordehai T, Rydberg EH, Man O, Beckmann JS, Silman I, Sussman JL. 2005. FoldIndex: a simple tool to predict whether a given protein sequence is intrinsically unfolded. Bioinformatics 21:3435–3438. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]