Abstract

Objective

At present, the absence of a pharmacological neuroprotectant represents an important unmet clinical need in the treatment of ischemic and traumatic brain injury. Recent evidence suggests that administration of apolipoprotein E mimetic therapies represent a viable therapeutic strategy in this setting. We investigate the neuroprotective and anti‐inflammatory properties of the apolipoprotein E mimetic pentapeptide, CN‐105, in a microglial cell line and murine model of ischemic stroke.

Methods

Ten to 13‐week‐old male C57/BL6 mice underwent transient middle cerebral artery occlusion and were randomly selected to receive CN‐105 (0.1 mg/kg) in 100 μL volume or vehicle via tail vein injection at various time points. Survival, motor‐sensory functional outcomes using rotarod test and 4‐limb wire hanging test, infarct volume assessment using 2,3,5‐Triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining method, and microglial activation in the contralateral hippocampus using F4/80 immunostaining were assessed at various time points. In vitro assessment of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha secretion in a microglial cell line was performed, and phosphoproteomic analysis conducted to explore early mechanistic pathways of CN‐105 in ischemic stroke.

Results

Mice receiving CN‐105 demonstrated improved survival, improved functional outcomes, reduced infarct volume, and reduced microglial activation. CN‐105 also suppressed inflammatory cytokines secretion in microglial cells in vitro. Phosphoproteomic signals suggest that CN‐105 reduces proinflammatory pathways and lower oxidative stress.

Interpretation

CN‐105 improves functional and histological outcomes in a murine model of ischemic stroke via modulation of neuroinflammatory pathways. Recent clinical trial of this compound has demonstrated favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profile, suggesting that CN‐105 represents an attractive candidate for clinical translation.

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1, 2 Currently, the only approved treatments for acute ischemic stroke include thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy.3 Because of the stringent time criteria to qualify for these treatments,4 <7% of all ischemic stroke patients actually receive these reperfusion interventions.5, 6, 7 Unfortunately, no other neuroprotective agent has been demonstrated to improve outcome. Thus, the development of a pharmacological intervention that mitigates secondary neuronal injury remains a compelling unmet clinical need.

The postischemic brain demonstrates a proinflammatory cascade, characterized by glial activation and release inflammatory mediators, neuronal excitotoxicity, and oxidative stress.8, 9 This neuroinflammatory cascade begins immediately after vascular occlusion and exacerbates secondary neuronal injury, resulting in further tissue injury days after the initial insult.9, 10, 11, 12 Targeting this cascade has potential for reducing tissue injury and lengthening the therapeutic window for revascularization. However, drugs targeting the inflammatory cascade have been unsuccessful in clinical trials, notably due to adverse effects and poor central nervous system (CNS) penetration.13, 14

Apolipoprotein E (apoE) is the primary apolipoprotein produced in the CNS, where its glial secretion is upregulated after injury.15 ApoE has demonstrated to suppress microglial and astrocyte activation in in vitro16, 17, 18 and in vivo models of brain injury.19, 20 In addition to its immunomodulatory effects, apoE attenuates N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate‐mediated neuronal excitotoxicity in cell culture models.21 ApoE also appears to protect from cerebral ischemia as apoE‐deficient animals demonstrate worse outcomes, both functionally and histologically, following experimental ischemia.19, 22, 23 ApoE exists in humans as three common isoforms, differing by single amino acid substitutions at residues 112 and 158.24 Isoform‐specific protective effects on endogenous neuroinflammatory responses have been observed in humans across different acute brain injuries25, 26 but not in cerebral ischemia.27, 28 Due to its large size, apoE does not cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and its therapeutic potential is limited. To overcome this limitation, smaller apoE‐mimetic peptides, derived from the helical receptor binding region of apoE, have been developed that retain the functional effects of the holoprotein on receptor binding29 in reducing inflammation17 and neuronal excitotoxicity.30 Moreover, these apoE‐mimetic compounds have demonstrated long‐term functional and histological improvements in preclinical models of ischemic stroke31, 32 and numerous other acute CNS injuries33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Therapeutic efficacy of apoE‐mimetic peptides in preclinical models of acute brain injuries

| Injury | Species | ApoE‐mimetic peptide | Functional improvement and survival advantage | Histological improvement | Biochemical improvement | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic Stroke (tMCAO) | Sprague–Dawley rats | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor (7 days), locomotor function | Reduction in infarct volume (35 days) | – | Tukhouvskaya et al., 2009 |

| C57Bl/6J mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor function (3 days) | Reduction in infarct volume (24 h), cerebral edema | Reduced of inflammatory cytokine (TNF‐α RNA) | Wang et al., 2013 | |

| Perinatal Hypoxia‐Ischemia | Wistar rat pups | COG133 | Reduced mortality | Reduction in brain tissue loss | – | McAdoo et al., 2005 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (collagenase injection) | C57Bl/6J mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor function (7 days) | Reduction in cerebral edema | Reduction in inflammatory cytokines (IL‐6 and eNOS) | James et al., 2009 |

| C57/BL6 mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor function (5 days), survival and reduced neurological severity. | Reduction in microgliosis, cerebral edema, and neuronal injury | Reduction in inflammatory signaling (phosphorylated p38 and NF‐kB protein) | Laskowitz et al., 2012 | |

| C57/BL6 mice | CN‐105 | Improved vestibulomotor function (5 days) and memory | Reduction in cerebral edema, microgliosis, and neuronal degeneration | – | Lei et al., 2016 | |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | C57/BL6 mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor function and reduced neurological severity | Reduction in microgliosis | Reduction in apoptotic markers and inflammatory signals (JNK, c‐Jun and p65) | Wu et al., 2016 |

| C57/BL6 mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor function (3 days), survival and reduced neurological severity | Reduction in vasospasm and cerebral edema | – | Gao et al., 2006 | |

| C57/BL6 mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor function (3 days) | Reduction in vasospasm | Mesis et al., 2006 | ||

| Traumatic brain injury (closed head injury) | C57Bl/6J mice | COG133 | Improved vestibulomotor function and memory (5 days) | Reduction in neuronal degeneration | Reduction in oxidative stress (aconitase) and inflammatory cytokine (TNFα) | Lynch et al., 2005 |

| C57Bl/6J mice | COG133 | Improved vestibulomotor function (5 days) | Reduction in neuronal degeneration and microgliosis | Reduction in amyloid‐beta expression | Wang et al., 2007 | |

| C57Bl/6J mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor function (5 days) and memory | Reduction in neuronal degeneration and microgliosis | – | Laskowitz et al., 2007 | |

| Traumatic brain injury (controlled cortical impact) | Sprague–Dawley rats | COG1410 | Improved sensorimotor function (14 days) | Reduction in lesion volume and astrocytosis | – | Hoane et al., 2007 |

| Sprague–Dawley rats | COG1410 | Improved somatosensory function and memory | Reduction in neuronal degeneration | – | Hoane et al., 2009 | |

| C57Bl/6J mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor (3 days) and neurological function | Reduction in lesion volume, cerebral edema, and BBB disruption | – | Cao et al., 2016 | |

| C57Bl/6J mice | COG1410 | Improved vestibulomotor function (7 days) | Reduction in cerebral edema, microvascular density, and neuronal degeneration | Reduction in VEGF expression and increased brain glucose uptake | Qin et al., 2016 |

BBB, blood–brain barrier; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; JNK, c‐Jun N‐terminal kinases; NF‐kB, nuclear factor kappa‐light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B cells; tMCAO, transient middle cerebral artery occlusion; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

CN‐105 is an apoE‐mimetic 5 amino acid peptide (acetyl‐Valine‐Serine‐Arginine‐Arginine‐Arginine‐amide) derived from the apoE receptor binding region by linearizing the polar face of the amphipathic helix involved in receptor interaction.35 CN‐105 has the advantage of increased CNS penetration35 over previous larger apoE‐mimetic peptides and has demonstrated efficacy in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage.35 Based on its preclinical safety and efficacy, CN‐105 was granted a successful investigational new drug application by the United States Food and Drug Administration and recently completed a Phase 1 clinical trial (clinical trials identifier: NCT02670824), where safety was demonstrated in both single escalating dose and multiple dosing paradigms.47 The evidence of good CNS penetration, efficacy in acute brain injury models, and reassuring safety profile suggest CN‐105 may be a viable candidate drug for further clinical development as a neuroprotective agent.

This study evaluates the therapeutic efficacy of CN‐105 in a murine model of transient focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. We test the hypothesis that intravenous administration of CN‐105 reduces mortality, results in improvement of functional and histological outcomes after experimental ischemic stroke, and reduces microglial activation. We also explore the mechanisms by which CN‐105 exerts its immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects by performing a phosphoproteomic analysis in animals exposed to cerebral ischemia.

Materials and Methods

Physiological effects of CN‐105

We performed a series of experiments to assess the safety and determine the physiological effects of CN‐105 using both males and females 8‐week‐old Crl:CD(SD) rats (Charles River Laboratories, Portage, Michigan). These experiments were independently conducted (MPI Research Inc, Mattawan, Michigan) prior to the conduct of further experiments in this study. These animals received an implanted femoral vein catheter exteriorized between the scapulae for intravenous dosing purposes. 0.9% Sodium Chloride for injection was used as vehicle. CN‐105 was synthesized by Polypeptide Inc (San Diego, CA) to a purity of >99%. CN‐105 was dissolved in vehicle to the concentration of 1.25 mg/mL. Repeated intravenous administration of 5 mg CN‐105/kg/dose or vehicle, four times per day (20 mg/kg/day) for 14 days 6 h apart (total of 56 doses per animal). Compared to the subsequent experiments, doses of CN‐105 used in these physiological studies were 50 times higher per dose and 200 times higher per day. Animals were randomized prior to any experiments and outcome assessments were performed in a blinded fashion.

Multiple physiological parameters were measured in these experiments. These included body temperature, hematological (platelet count and coagulation profile), biochemistry (glucose, creatinine, and total bilirubin), and respiratory (respiratory rate and minute ventilation) evaluations. Full experimental details are available in Data S1.

Peptide synthesis and administration

CN‐105 used in subsequent animal experiments was similarly synthesized by Polypeptide Inc (San Diego, CA) to a purity of >99%. However, CN‐105 was dissolved in 1× phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), reconstituted to 0.1 mg/kg concentration in 100 μL volume and administered via tail vein injection.

Animal procedures

In all experiments, mice were randomized to treatment and vehicle group before injury and all animals were treated with allocation concealment. In each experiment, mice were randomized to treatment or vehicle groups prior to injury. Animals were treated with blinded concealment. All procedures and assessments were performed in blinded fashion. Animal procedures were approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in keeping with established guidelines.

Model of focal ischemia and reperfusion

Ten‐ to 13‐week‐old C57Bl/6J male mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were used. Focal cerebral ischemia was induced by filamentous transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO), as previously described.32 To model the effect of CN‐105 in different clinical stroke severities, two different ischemic intervals were used. A 30‐min ischemic occlusion associated with high mortality was used to assess for mortality advantage and the phosphoproteomic signature of CN‐105 effects on large stroke volumes. A shorter 15‐min ischemic occlusion time, associated with lower mortality, was used to assess long‐term functional and histological endpoints.

Functional assessments

Vestibulomotor performance was assessed daily postinjury with the accelerating rotarod (Med Associates Inc, Georgia, Vermont), as previously described.32 The time in which the mouse was able to stay on the rotating rod before falling (rotarod latency) was recorded up to 300 sec and the average of three trials was used.

Motor coordination and limb muscle strength was assessed with the 4‐limb wire hanging test.48 A mouse was placed on the center of a wire grid upright and the grid was inverted gently. The time it took for the mouse to fall off the grid (hanging latency) was recorded up to 600 sec. The test was performed at 2 and 7 days post injury and repeated three times per day. Maximal hanging latency was used.

Infarct volume measurements

Coronally sectioned (1‐mm thick) brain slices were stained in 2% 2,3,5‐triphenyletrazolium chloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to protocol.49 After staining, images were captured and analyzed using open‐source software (Image J, version 1.49, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland). The infarcted area per slice was determined by subtracting the area of viable stained tissue of the ipsilateral hemisphere from the unaffected viable area of the contralateral hemisphere. Final infarct volume was the sum of infarcted areas multiplied by slice thickness.

Contralateral hemisphere microglial quantification

Frozen coronal brain sections (40 μm thick) were stained with anti‐rat F4/80 antibody (rat monoclonal, 1:10,000; Serotec, Raleigh, NC) specific for activated microglia and cells of the monocyte lineage.34 Microglial count was performed in the contralateral hippocampus using the optical fractionator method.50 Microglia per unit volume (count density) was used to allow comparability between animals.

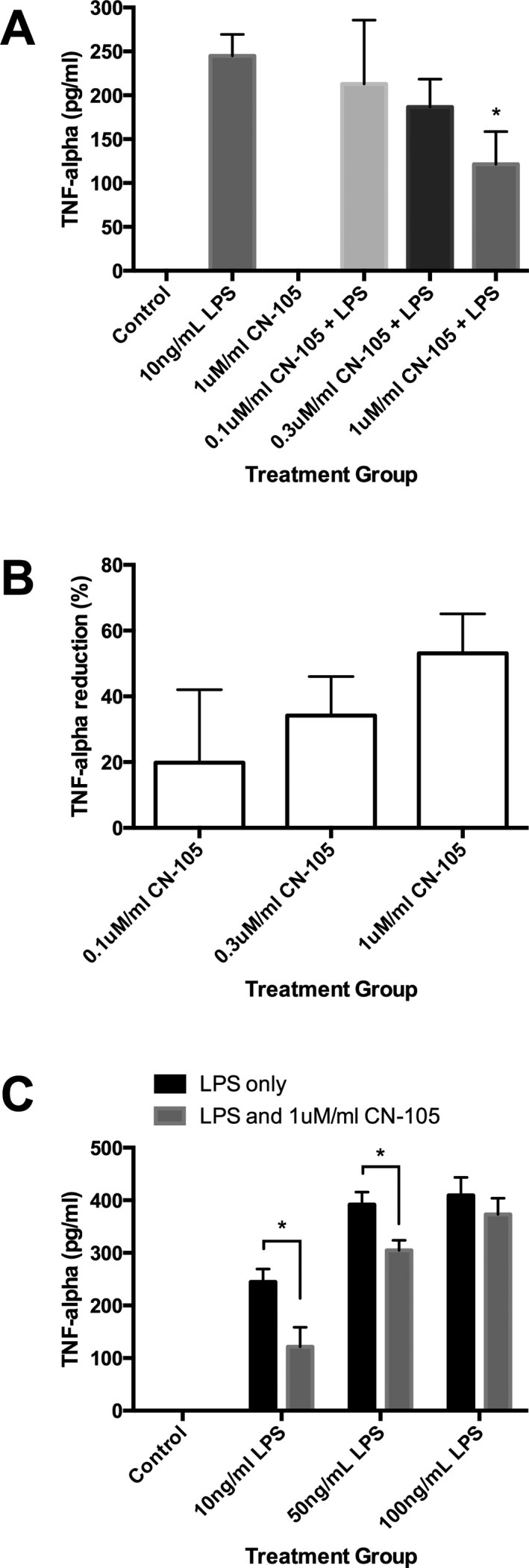

TNF‐α suppression by CN‐105 in microglial cells

For all in vitro experiments, C8‐B4 mouse microglia cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were used. We investigated the change in production of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α) produced by increasing concentrations of CN‐105 (0.1, 0.3, and 1 μM/mL) using fixed lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) stimulation (10 ng/mL), and by fixed concentration of 1 μM/mL of CN‐105 using increasing concentrations of LPS stimulation (10, 50, and 100 ng/mL). Cell supernatant was analyzed using Mouse TNF‐α DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) per manufacturer's protocol. All experiments were repeated six times and mean TNF‐α concentrations were recorded at 4 h post incubation.

Differential phosphopeptide expression

Following 30 min of ischemia, CN‐105 or vehicle was administered at 15 min after reperfusion. At 30 min after reperfusion, mice were killed, brains were removed and dissected in the midsagittal plane. Each hemisphere was flash‐frozen separately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The injured right hemispheres were used for analysis. Peptides were prepared from brain samples for liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS/MS) analysis (Data S2). Peptide digests obtained from each of the samples were analyzed in a label‐free quantitative fashion using a nanoAcquity UPLC system coupled to a Synapt HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters Corp, Milford, MA) for unenriched peptide analyses and an LTQ Orbitrap XL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for phosphopeptide analyses. Robust peak detection and label‐free alignment of individual peptides across all sample injections was performed using the commercial package Rosetta Elucidator v3.3 (Rosetta Biosoftware, Inc., Seattle, WA) with PeakTeller algorithm.

Statistical analysis

Independent two‐tailed t‐test was performed for infarct volume, microglial density analysis, and TNF‐α concentration of microglial cells. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for rotarod and 4‐limb wire hanging latencies, and Dunnett's post hoc test for multiple comparisons was used. Log‐rank test was performed for survival evaluation. Principal components analysis was performed between sample groups to screen for outliers in the phosphoproteomic data. The independent two‐tailed t‐test was performed on log2 protein intensities of the phosphopeptide (peptide‐level) datasets. Significance level for all tests was set at P < 0.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Absence of adverse physiological effects by CN‐105

Repeated intravenous administration of 5 mg CN‐105/kg/dose 4× per day (20 mg/kg/day) for 14 days over 5 min did not produce mortality and was without significant clinical effect on body temperature, hematology and coagulation, biochemistry, and respiratory parameters. Systemic exposure to CN‐105 was independent of sex and did not appear to change following repeated administration. Full results on physiological testing of CN‐105 are found in Supplemental Material 1.

CN‐105 confers survival benefit and functional improvements

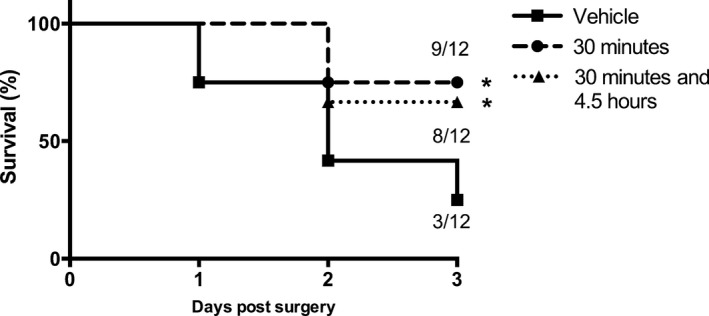

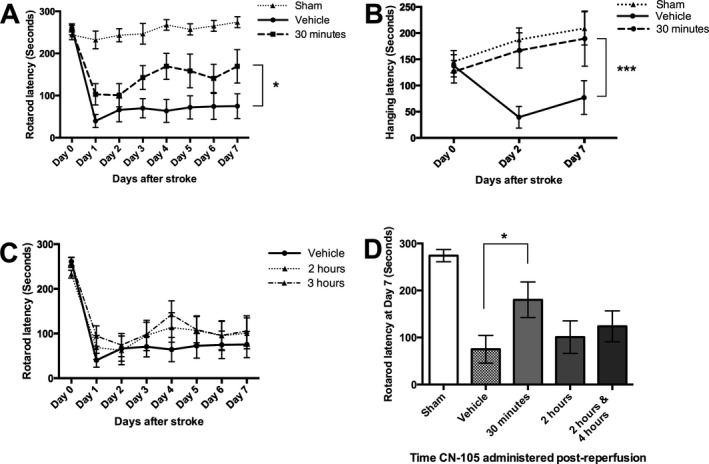

CN‐105 administrated at 30‐min post reperfusion, compared to vehicle, significantly improved survival at 3 days (75% vs. 25%, P = 0.013) (Fig. 1). An additional dose of CN‐105 at 4.5 h after reperfusion maintained the survival benefit, but did not enhance it. Administration of CN‐105 also conferred functional improvement following ischemic injury as demonstrated by improved rotarod latency (P = 0.035) and hanging latency (P < 0.001). The improvement was observed as early as the first day post injury and the benefit was maintained up to 7 days. No significant functional improvement was observed when CN‐105 was administered beyond 30 min post reperfusion (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

CN‐105 confers survival benefit in ischemic stroke. Intravenous CN‐105 confers survival benefit at 3 days (A) when administered via a single dose at 30 min post reperfusion, and via 2 doses at 30 min and 4.5 h post reperfusion, utilizing the murine model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) of 30 min ischemic occlusion time. (*P < 0.05 by log‐rank test compared to vehicle).

Figure 2.

CN‐105 improves functional outcomes in ischemic stroke. (A) Improvement in rotarod latency when CN‐105 is administered 30 min post reperfusion, compared to vehicle. Improvement is observed from first day post stroke and increase over the subsequent 7 days. (B) Improvement in the 4‐limb wire hanging test latency when CN‐105 is administered 30 min post reperfusion, compared to vehicle. Improvement is observed from day 2 post‐stroke and maintained till day 7. (C) No improvement of rotarod timing observed when CN‐105 is administered 2 and 3 h post reperfusion. (D) Rotarod latency at day 7 for all treatment groups. (*P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 by repeated measures ANOVA and *P < 0.05 by independent t‐test, and error bars represent standard error of mean).

CN‐105 reduces infarct volumes and contralateral microglial activation

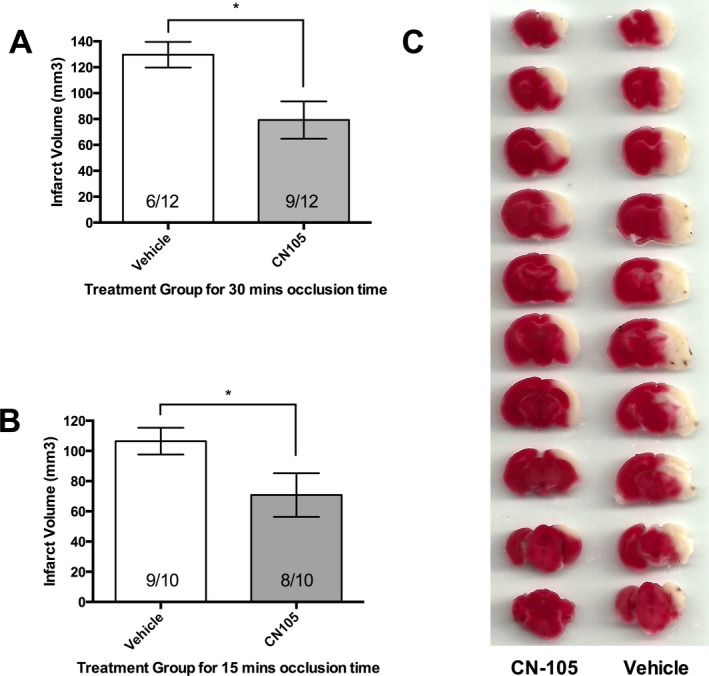

CN‐105, when administered 30 min post reperfusion, demonstrated a significant reduction in infarct volume at 72 h post stroke. The reduction in infarct volume was observed in both our tMCAO models of 30 min (126.7 ± 9.9 mm3 vs. 79.2 ± 14.4 mm3, P = 0.023) and 15 min ischemic occlusion time (106.5 ± 8.8 mm3 vs. 70.8 ± 14.5 mm3, P = 0.048) (Fig. 3). This represents an approximate 38% and 34% reduction in infarct volume in the 30 min and 15 min models, respectively.

Figure 3.

Significant reduction in infarct volume at 72 h post stroke using 2% 2,3,5‐triphenyletrazolium chloride staining methods. Reduction was observed in both our murine transient middle cerebral artery occlusion models of (A) 30 min ischemic occlusion time and (B) 15 min ischemic occlusion time. Numbers indicate the number of mice that survived to 72 h in each experimental group. (C) Representative brain slices from the 30 min ischemic occlusion experiment demonstrating the reduction in infarct volume with CN‐105. (*P < 0.05 by two‐tailed independent t‐test and error bars represent standard error of mean).

We observed that the survival in the vehicle arm in this experiment with 30‐min ischemic occlusion‐time (6 of 12 mice) was better than the preceding mortality experiment (3 of 12 mice). However, the survival of the CN‐105 arm was the same for both experiments (9 of 12 mice). Moreover, a post hoc analysis of survival at 72‐h, by combining the survival data of both experiments and using a two‐tailed chi‐squared test, still demonstrated significant survival benefit (15/24 (62.5%) vs. 9/24 (37.5%), P = 0.0189), supporting the mortality benefit of CN‐105.

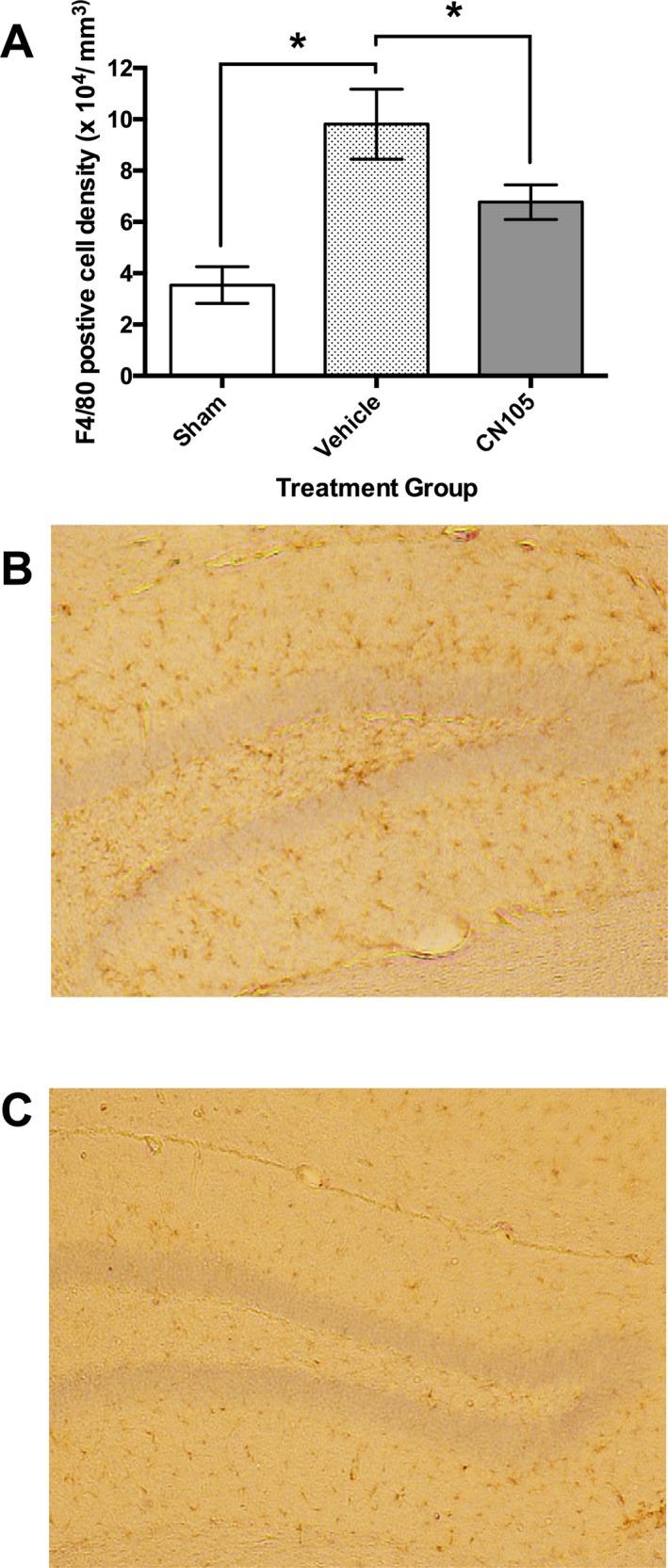

To assess the global protective effects from neuroinflammation by CN‐105 in focal ischemia, we quantified the amount of microglial activation in the contralateral uninjured hippocampus at 7 days post injury, following a 15‐min ischemic interval. Stereological analysis revealed significant increase in F4/80 immunopositive microglial cell density in tMCAO vehicle‐treated mice versus sham (9.8 ± 1.4 × 104/mm3 vs. 3.5 ± 0.7 × 104/mm3, P = 0.016). There was significant reduction in microglial cell density by CN‐105 compared to vehicle (6.8 ± 0.7 × 104/mm3 vs. 9.8 ± 1.4 × 104/mm3, P = 0.047) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

F4/80 immunocytochemical staining of microglia in contralateral hippocampus 7 days after ischemic stroke. (A) Microglial count density was significantly reduced by CN‐105, when administered 30 min post reperfusion, as compared to vehicle. Numbers indicate the number of mice that survived to 7 days in each experimental group. Representative images (4× magnification) of contralateral hippocampus demonstrating reduction in microglial cell density in hippocampal sections treated with vehicle (B) and CN‐105 (C). Microglial cells are stained brown by anti‐rat F4/80 antibody within the hippocampus. (*P < 0.05 by two‐tailed independent t‐test and error bars represent standard error of mean).

CN‐105 suppresses TNF‐α production in LPS‐stimulated microglial cells

In cultures of C8‐B4 murine microglial cells, TNF‐α production was increased in response to LPS stimulation. There was significant suppression of microglial TNF‐α production in the presence of 1 μM/mL concentration of CN‐105 versus LPS alone (121.5 ± 37 ng/mL vs. 245 ± 25 ng/mL, P = 0.0196) using 10 ng/ml LPS stimulation measured at 4 h. Although suppression of TNF‐α production was not significant at lower concentrations of CN‐105, the percentage of suppression of TNF‐α by CN‐105 is concentration‐dependent with 20%, 34% and 53% suppression observed with 0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM/mL of CN‐105, respectively. CN‐105 was also able to suppress microglial TNF‐α secretion up to a concentration of 50 ng/mL of LPS stimulation (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

CN‐105 induced suppression of microglial tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF‐α) secretion. C8‐B4 microglial cells were incubated with LPS and subsequent TNF‐α production was quantified by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (A) TNF‐α was measured at 4 h after incubation. (B) Percentage suppression of TNF‐α secretion using 10 ng/mL LPS measured at 4 h post incubation with 0.1, 0.3, and 1 μM/mL of CN‐105 compared to LPS alone. (C) TNF‐α secretion at 10, 50, 100 ng/mL LPS with 1 μmol/L of CN‐105. (*P < 0.05 by two‐tailed independent t‐test and error bars represent standard error of mean) LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Phosphoproteomic signatures support neuroprotective effects of CN‐105

To explore potential pathways by which CN‐105 exerted its neuroprotective effects, we performed a phosphoproteomic analysis of the ischemic brain. Protein phosphorylation is critical to cell signaling, in which the binding of ligand to an extracellular domain may modify multiple downstream cell functions.51

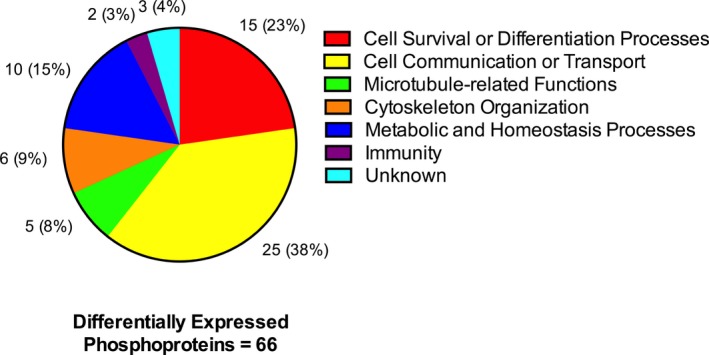

CN‐105 affected phosphorylation of neuroinflammatory proteins in ischemic stroke. Seventy‐one unique phosphotyrosine sites were differentially changed between CN‐105 and vehicle, of which 6 were upregulated and 65 were downregulated by more than twofold. These 71 phosphotyrosine sites corresponded to 66 unique phosphoproteins. Notable phosphoproteins differentially changed by CN‐105 mediate cellular survival (Rho GTPase activating protein 1), immunity (tyrosine kinase Lyn), and BBB integrity (cyclophilin A) (Table 2). Biological processes altered by CN‐105 (Fig. 6 and Table S1), known signaling pathways, biological functions of each phosphoproteins, and results of enrichment specificity, data quality control, and outlier screening can be found in the supplementary material (Table S2–S3 and Data S2).

Table 2.

Statistically different phosphopeptides between CN‐105 and vehicle in ischemic stroke

| Protein Name | Gene symbol and UniProtKB number | Modified peptide sequencea (phosphotyrosine position) | CN‐105 v vehicle fold change | P ‐value (two‐tailed t‐test) | Biological process of protein | Function of specific phosphorylation site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated Phosphopeptides | ||||||

| Disks large‐associated protein 2 | Dlgap2, Q8BJ42 | MHYSSHYDTR (169) | 2.416 | 0.040 | May play a role in the molecular organization of synapses and neuronal cell signaling. | Unknown |

| Golgi integral membrane protein 4 | Golim4, Q8BXA1 | GRQEHYEEEEDEEDGAAVAEK (633) | 2.039 | 0.037 | Plays a role in endosome to Golgi protein trafficking | Controlled by leptin in mouse liver. |

| Histone H4 | Hist1h4a, P62806 | KTVTAMDVVYALK (88) | 2.473 | 0.036 | Chromatin organization | Unknown |

| TVTAMDVVYALK (88) | 2.057 | 0.026 | ||||

| Insulin receptor substrate 2 | Irs2, P81122 | SDDYMPMSPTSVSAPK (671) | 13.414 | 0.048 | Transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling | Insulin induce phosphorylation at Y671, which in turn activate PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway in endothelial cells. |

| Probable phospholipid‐transporting ATPase IA | Atp8a1, P70704 | NTQWVHGIVVYTGHDTK (269) | 9.686 | 0.020 | Anion transport, Catabolic process | Unknown |

| Sodium/potassium‐transporting ATPase subunit alpha‐1 | Atp1a1, Q8VDN2 | KYGTDLSR (55) | 2.259 | 0.036 | Homeostatic process, Catabolic process | Unknown |

| Downregulated Phosphopeptides | ||||||

| 1‐phosphatidylinositol‐4,5‐bisphosphate phosphodiesterase gamma‐1 | Plcg1, Q62077 | KLAEGSAYEEVPTSVMYSENDISNSIK (472) | −3.211 | 0.043 | Intracellular signal transduction via G‐protein‐coupled receptor signaling and Phospholipid metabolic process | Human analog controlled by ephrin_B1 |

| 14‐3‐3 protein beta/alpha | Ywhab, Q9CQV8 | QTTVSNSQQAYQEAFEISKK (151) | −2.391 | 0.037 | Cell cycle | Unknown |

| QTTVSNSQQAYQEAFEISK (151) | −2.434 | 0.028 | ||||

| Alpha‐enolase | Eno1, P17182 | SGKYDLDFK (257) | −2.078 | 0.035 | Glycolysis | Unknown |

| Ankyrin‐2 | Ank2, Q8C8R3 | NGYTPLHIAAK (630) | −2.338 | 0.010 | Protein localization and Intracellular protein transport | Unknown |

| QELEDNDKYQQFR (2113) | −6.332 | 0.014 | Novel phosphorylation site | |||

| Band 4.1‐like protein 1 | Epb41l1, Q9Z2H5 | HLTQQDTRPAEQSLDMDDKDYSEADGLSER (68) | −3.678 | 0.021 | May confer stability and plasticity to neuronal membrane | Unknown |

| Band 4.1‐like protein 3 | Epb41l3, Q9WV92 | DSVSAAEVGTGQYATTK (479) | −2.577 | 0.024 | Inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. | Human isoform 2 (Y471) controlled by ephrin_B1. |

| Calcium‐dependent secretion activator 2 | Cadps2, Q8BYR5 | TYDTLHR (1273) | −3.236 | 0.012 | Exocytosis | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Calmodulin‐regulated spectrin‐associated protein 2 | Camsap1 l1, Q8C1B1 | EEAAGAEDEKVYTDR (799) | −2.566 | 0.032 | Regulator of noncentrosomal microtubule dynamics and organization. | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Calmodulin‐regulated spectrin‐associated protein 3 | Kiaa1543, Q80VC9 | APIYISHPENPSK (520) | −2.143 | 0.033 | Regulator of noncentrosomal microtubule dynamics and organization. | Unknown |

| Casein kinase I isoform delta | Csnk1d, Q9DC28 | YASINTHLGIEQSR (179) | −2.342 | 0.012 | Cellular component morphogenesis and endocytosis | Novel phosphorylation site |

| CLIP‐associating protein 2 | Clasp2, Q8BRT1 | DYNPYNYSDSISPFNK (1014) | −2.972 | 0.044 | Cell cycle. | Unknown |

| CMRF35‐like molecule 8 | Cd300a, Q6SJQ0 | AEYSEIQKPR (303) | −4.043 | 0.048 | Intracellular protein transport and receptor‐mediated endocytosis | Unknown |

| Coronin‐1A | Coro1a, O89053 | ADQCYEDVR (25) | −3.084 | 0.038 | Cytoskeleton organization | Unknown |

| HVFGQPAKADQCYEDVR (25) | −5.976 | 0.042 | ||||

| Coronin‐2A | Coro2a, Q8C0P5 | ENCYDSVPITR (26) | −2.633 | 0.040 | Cytoskeleton organization | Unknown |

| Cytochrome c‐type heme lyase | Hccs, P53702 | AYDYVECPVTGAR (67) | −5.111 | 0.006 | Cell cycle and coenzyme metabolic process | Unknown |

| Cytoplasmic dynein 1 heavy chain 1 | Dync1h1, Q9JHU4 | AISKDHLYGTLDPNTR (2263) | −4.501 | 0.031 | Cellular component morphogenesis, Cell cycle, Cellular component movement, Intracellular protein transport | Unknown |

| Dynamin‐1 | Dnm1, P39053 | RIEGSGDQIDTYELSGGAR (354) | −2.404 | 0.044 | Cellular component morphogenesis, Intracellular protein transport, Endocytosis | Unknown |

| IEGSGDQIDTYELSGGAR (354) | −2.893 | 0.045 | ||||

| EVDEYKNFRPDDPAR (314) | −3.247 | 0.018 | Novel phosphorylation site | |||

| LQSQLLSIEKEVDEYK (314) | −4.276 | 0.038 | ||||

| Dynamin‐1‐like protein | Dnm1l, Q8K1M6 | NKLYTDFDEIR (107) | −2.832 | 0.047 | Cellular component morphogenesis, Intracellular protein transport, Endocytosis | Novel phosphorylation site |

| EH domain‐containing protein 3 | Ehd3, Q9QXY6 | ELVNNLAEIYGR (339) | −3.179 | 0.043 | Synaptic transmission, Intracellular protein transport, Endocytosis, Neurotransmitter secretion | Unknown |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma 1 | Eif4g1, Q6NZJ6 | KVEYTLGEESEAPGQR (1424) | −2.610 | 0.029 | Apoptosis | Unknown |

| Glutaminase kidney isoform | Gls, D3Z7P3 | YAIAVNDLGTEYVHR (309) | −5.463 | <0.001 | Cellular amino acid biosynthetic catabolic process | Unknown |

| Glutathione S‐transferase P 1 | Gstp1, P19157 | YVTLIYTNYENGKNDYVK (119) | −2.652 | 0.029 | Conjugation of reduced glutathione | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Heat shock protein 105 | Hsph1, Q61699 | NAVEECVYEFRDK (644) | −2.354 | 0.043 | Protein complex assembly | Unknown |

| LysM and putative peptidoglycan‐binding domain‐containing protein 2 | Lysmd2, Q9D7V2 | DEESPYAASLYHS (208) | −3.571 | 0.030 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Microtubule‐associated protein 6 | Map6, Q7TSJ2 | SLYSEPFKECPK (493) | −3.469 | 0.020 | Microtubule stabilization | Unknown |

| Myosin‐Va | Myo5a, Q99104 | RTDSTHSSNESEYTFSSEFAETEDIAPR (1124) | −6.827 | 0.041 | Cellular component morphogenesis, Intracellular signal transduction, Cell cycle, Cytokinesis, Muscle development, Intracellular protein transport, Muscle contraction, Sensory perception | Unknown |

| Myotrophin | Mtpn, P62774 | DYVAKGEDVNR (21) | −3.285 | 0.005 | Promotes dimerization of NF‐kappa‐B subunits and regulates NF‐kappa‐B transcription factor activity | Unknown |

| Myotubularin‐related protein 5 | Sbf1, Q6ZPE2 | RSTSTLYSQFQTAESENR (1751) | −4.030 | 0.005 | Intracellular protein transport, Phospholipid metabolic process | Human analog controlled by Ephrin B1 |

| Neurochondrin | Ncdn, Q9Z0E0 | SMIDDTYQCLTAVAGTPR (156) | −3.042 | 0.044 | Signal transduction | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Peptidyl‐prolyl cis‐trans isomerase A | Ppia, P17742 | SIYGEKFEDENFILK (79) | −2.432 | 0.049 | Accelerate the folding of proteins | Unknown |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine‐binding protein 1 | Pebp1, P70296 | LYEQLSGK (181) | −2.263 | 0.040 | Binds ATP, opioids and phosphatidylethanolamine | Regulated by Catsper1 in murine sperm |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | Pgk1, P09411 | LGDVYVNDAFGTAHR (161) | −3.703 | 0.011 | Glycolysis | Unknown |

| Probable cationic amino acid transporter | Slc7a14, Q8BXR1 | EQALHQSTYQR (693) | −2.369 | 0.040 | Amino acid transporter, Anion transport | Unknown |

| Probable G‐protein‐coupled receptor 158 | Gpr158, Q8C419 | KLYAQLEIYKR (722) | −2.507 | 0.003 | G‐protein‐coupled receptor signaling | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Programmed cell death 6‐interacting protein | Pdcd6ip, Q9WU78 | IYGGLTSK (608) | −4.124 | 0.002 | Unknown orphan receptor. | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Protein arginine N‐methyltransferase 8 | Prmt8, Q6PAK3 | RGEEIYGTISMKPNAK (355) | −2.181 | 0.039 | Chromatin organization, Regulation of nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process, Biosynthetic process, Transcription | Unknown |

| Protein EFR3 homolog B | Efr3b, Q6ZQ18 | KKEAPYMLPEDVFVEKPR (629) | −2.364 | 0.006 | Component of a complex required to localize phosphatidylinositol 4‐kinase (PI4K) to the plasma membrane | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Protein FAM126B | Fam126b, Q8C729 | YSTISLQEDR (487) | −2.301 | 0.026 | Mediates cellular transport and reorganization of the microtubule cytoskeleton | Unknown |

| Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neurons protein 1 | Pacsin1, Q61644 | GPQYGSLER (74) | −3.649 | 0.012 | Cellular component morphogenesis, Cell differentiation, Nervous system development, Endocytosis | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Protein XRP2 | Rp2, Q9EPK2 | DYMFSGLKDETVGRLPGK (37) | −3.700 | 0.025 | Purine nucleobase metabolic process | Unknown |

| Putative tyrosine‐protein phosphatase auxilin | Dnajc6, Q80TZ3 | HLDHYTVYNLSPK (134) | −2.616 | 0.034 | Intracellular protein transport, Endocytosis | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Receptor‐type tyrosine‐protein phosphatase‐like N | Ptprn, Q60673 | LAALGPEGAHGDTTFEYQDLCR (628) | −2.592 | 0.031 | Plays a role in vesicle‐mediated secretory processes | Unknown |

| Regulator of G‐protein signaling 6 | Rgs6, Q9Z2H2 | SVYGVTDETQSQSPVHIPSQPIRK (234) | −3.918 | 0.042 | Regulation of nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process, Regulation of phosphate metabolic process, Catabolic process | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Rho GTPase‐activating protein 1 | Arhgap1, Q5FWK3 | HQIVEVAGDDKYGR (81) | −2.031 | 0.043 | Regulation of nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process, Regulation of phosphate metabolic process, Regulation of catalytic activity, Catabolic process. | Unknown |

| Rho GTPase‐activating protein 35 | Arhgap35, Q91YM2 | KMQASPEYQDYVYLEGTQK (308) | −3.163 | 0.035 | Regulation of nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process, Regulation of phosphate metabolic process, Regulation of catalytic activity, Catabolic process | Growth factors induce phosphorylation of thyrosine at position 308, which disrupts its ability to bind with General Transcription Factor II‐I. |

| SH3 and cysteine‐rich domain‐containing protein 2 | Stac2, Q8R1B0 | ESPPTGTSGKVDPVYETLR (205) | −2.054 | 0.044 | Unknown | Unknown |

| SH3 and PX domain‐containing protein 2B | Sh3pxd2b, A2AAY5 | TEPAQSEDHVDIYNLR (661) | −3.128 | 0.040 | Intracellular signal transduction | Unknown |

| SLIT‐ROBO Rho GTPase‐activating protein 3 | Srgap3, Q812A2 | NDLQSPTEHISDYGFGGVMGR (845) | −2.312 | 0.024 | Regulation of nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process, Regulation of phosphate metabolic process, Cellular component movement, Locomotion, Catabolic process | Unknown |

| Src substrate cortactin | Cttn, Q60598 | NASTFEEVVQVPSAYQK (334) | −3.605 | 0.030 | Cellular component morphogenesis | Phosphorylation is by proto‐oncogene tyrosine‐protein kinase Src and dephosphorylation is by protein tyrosine phosphophatase 1B. |

| Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2B | Sv2b, Q8BG39 | YRDNYEGYAPSDGYYR (10) | −2.635 | 0.004 | Synaptic transmission, Neurotransmitter secretion | Unknown |

| DNYEGYAPSDGYYR (10) | −3.735 | 0.016 | ||||

| Synaptogyrin‐3 | Syngr3, Q8R191 | GYQVPAY (224) | −3.971 | 0.026 | Positive regulation of dopamine transporter activity | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Syntaxin‐binding protein 1 | Stxbp1, O08599 | ERISEQTYQLSR (473) | −2.563 | 0.035 | Lysosomal transport, Intracellular protein transport, Synaptic vesicle exocytosis, Neurotransmitter secretion | Unknown |

| ISEQTYQLSR (473) | −2.843 | 0.015 | ||||

| YSTHLHLAEDCMK (344) | −2.920 | 0.019 | Novel phosphorylation site | |||

| HYQGTVDKLCR (358) | −3.161 | 0.025 | Novel phosphorylation site | |||

| Thioredoxin reductase 1, cytoplasmic | Txnrd1, Q9JMH6 | VVYENAYGR (245) | −2.016 | 0.032 | Respiratory electron transport chain | Phosphorylation is by proto‐oncogene tyrosine‐protein kinase Src. Phosphorylation of human analog (tyrosine 281) reduced by ZAP70 and upregulated in neuroblastoma. |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | Tpi1, P17751 | IIYGGSVTGATCK (259) | −2.893 | 0.029 | Glycolysis and gluconeogensis | Unknown |

| Tubulin polymerization‐promoting protein | Tppp, Q7TQD2 | VDLVDESGYVPGYK (200) | −3.438 | 0.008 | Microtubule functions | Unknown |

| Type I inositol 3,4‐bisphosphate 4‐phosphatase | Inpp4a, Q9EPW0 | VQDDGGSDQNYDVVTIGAPAAHCQGFK (355) | −2.552 | 0.013 | Regulation of megakaryocyte and fibroblast proliferation | Unknown |

| HYRPPEGTYGKVET (934) | −3.111 | 0.031 | Unknown | |||

| Tyrosine‐protein kinase | Lyn, P25911 | VIEDNEYTAR (397) | −2.289 | 0.015 | Cell adhesion, Transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling, Cell proliferation, Cellular component movement, Cell differentiation, Apoptosis, Hemopoiesis, Nervous system development, Immune system response, Exocytosis, Locomotion, Coagulation, Stress response | Phosphorylation of tyrosine in at tyrosine 397, located within the activation loop, is required for its kinase activity. Lyn is activated by B‐cell receptor and inhibited by CD45. |

| UPF0554 protein C2orf43 homolog | Ldah, Q8BVA5 | IEDVYGLNGQIEHK (111) | −2.475 | 0.015 | Serine lipid hydrolase associated with lipid droplets | Novel phosphorylation site |

| Vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter | Slc32a1, O35633 | SEGEPCGDEGAEAPVEGDIHYQR (Y85) | −2.321 | 0.020 | Amino acid transporter, Anion transport | Unknown |

| Wolframin | Wfs1, P56695 | NYIALDDFVELTKK (242) | −7.251 | 0.045 | Regulation of cellular Ca2 + homeostasis | Unknown |

Underlined amino acid represents phosphorylated tyrosine and numbers in brackets indicate the phosphotyrosine position.

Figure 6.

Main biological processes of differentially expressed phosphoproteins by CN‐105 in ischemic stroke. Sixty‐six phosphoproteins were differentially expressed between CN‐105 and vehicle in ischemic stroke. Majority of the biological functions of these phosphoproteins were involved in cell survival and signaling.

Discussion

Our study has demonstrated that CN‐105, an apoE‐mimetic pentapeptide, reduces mortality, infarct volume, microgliosis, and improves long‐term functional outcome in a murine reperfusion model of ischemic stroke. We have previously demonstrated that larger peptides derived from the apoE receptor‐binding region (apoE133‐149) retain the neuroprotective and anti‐inflammatory properties8, 17, 30, 52, 53 of the apoE holoprotein. However, these peptides were limited by their relatively larger size, resulting in lower CNS penetration and higher cost of production. CN‐105, our current apoE‐mimetic pentapeptide, retains the beneficial neuroprotective effect in ischemic stroke observed in other apoE‐mimetic peptides31, 32 and possesses increased CNS penetration and potency.35

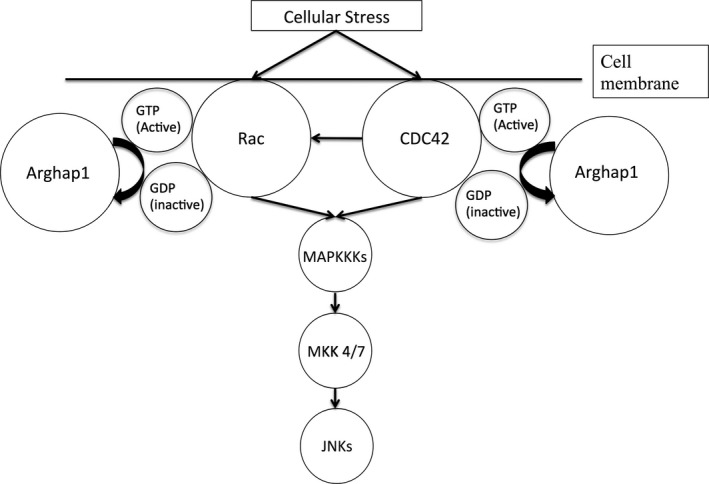

We demonstrated that CN‐105 downregulates microglial activation in ischemic stroke and suppress TNF‐α secretion from C8‐B4 microglial cells. These immune‐modulatory effects on microglial by CN‐105 are consistent with apoE15, 16, 17, 54 and other apoE‐mimetic peptides.17, 34 LRP1, a cell surface receptor, has been shown to bind apoE55 and other apoE‐mimetic peptides.29, 56 The function of this interaction between apoE and LRP1, has been associated with suppression of neuroinflammation.57 Microglial cells, which expresses LRP1, are resident macrophages within the CNS that become activated in pathological situations, including cerebral ischemia.58 Microglial activation results in oxidative stress and the release of inflammatory mediators, contributing to BBB breakdown, secondary neuronal injury, and development of cerebral edema.59 There is evidence that apoE‐mimetic peptides reduce these inflammatory responses in microglial cells, via LRP1, through the c‐Jun N‐terminal kinases (JNKs) pathway.60, 61 JNKs are stress‐activated protein kinases that mediate the activation of microglia.62 External cellular stress, such as ischemia, induces a complex system of upstream signals, which in turn activates JNKs and results in expression of transcription factors, such as c‐Jun or c‐Fos, that participate in apoptosis and many cell death paradigms.62 Our early phosphoproteomic results support the hypothesis that CN‐105 mediates the downregulation of JNK pathway, through the identification of the differentially phosphorylated Rho GTPase‐activating protein 1 (Arghap1). Arghap1 serves as a upstream molecular switch which converts various stress‐induced proteins into an inactive state63 (Fig. 7). These inactivated proteins are then unable to transmit signals to activate JNKs downstream.64

Figure 7.

Rho GTPase‐activating protein 1 (Arghap1) downregulates c‐JNKs pathway through inactivation of stress‐induced proteins. External cellular stress induces activation of Ras‐Related C3 Botulinum Toxin Substrate (Rac) and Cell Division Cycle‐42 (CDC42). This triggers the sequential activation of mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase kinases (MAPKKKs) and mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinases 4/7, resulting in JNKs activation. Arghap1 accelerate the intrinsic GTPase activity of Rac and CDC42 to return it to the inactive GDP‐bound conformation, resulting in downregulation of subsequent pathways. JNKs, Jun N‐terminal kinases.

Our study revealed a novel finding of increased microglial activation in the uninjured contralateral hippocampus after experimental ischemic stroke. Although the blood supply is not interrupted, it has been previously reported that the “healthy” contralateral hemisphere of an ischemic brain is associated with radiographic changes65 in the immediate poststroke period. Secretion of inflammatory mediators and trophic factors by non‐neuronal cells66 has been implicated. Our current finding of elevated microglial cell density in the contralateral hippocampus suggest that global and potentially detrimental inflammatory changes exist throughout the brain following focal ischemia. Remote downregulation of microglial activation in the contralateral uninjured hippocampus by CN‐105 suggests its anti‐inflammatory benefit extends beyond the effect of reducing the ipsilateral infarct volume.

A possible mechanism by which CN‐105 exerts its anti‐inflammatory and neuroprotective effect may be through the preservation of the BBB. After ischemic stroke, BBB disruption occurs and persists for days. ApoE appears to protect cerebrovascular integrity in acute brain injury through maintenance of the BBB, as demonstrated in apoE‐deficient mice, which was associated with an increase in disruption of BBB after injury.67, 68, 69 More recently, it has been found that apoE stabilizes BBB through suppression of cyclophilin A (Peptidylprolyl cis‐trans isomerase A or CypA) in an isoform‐specific manner via interaction with LRP1.57 We observed, through our phosphoproteomic study, that CN‐105 downregulated phosphorylation of CypA in ischemic stroke. This is consistent with the hypothesis that CN‐105 downregulates CypA and results in improved BBB integrity following ischemic stroke. Additionally, the phosphorylation site identified at tyrosine 79 of CypA in our data possibly points toward a critical signaling mechanism between CypA and either the upstream LRP1 receptor or downstream nuclear‐factor‐keppa‐beta transcription factor61 and deserves further investigation. CypA has also been additionally implicated in posthypoxic apoptosis via apoptosis‐inducing factor,70 suggesting that downregulation of CypA by CN‐105 may confer other neuroprotective effects.

Reduction in early mortality (24–72 h) after ischemic stroke was observed in our study with CN‐105. Early mortality in acute ischemic stroke is associated with initial clinical stroke severity, the size of the infarct and subsequent cerebral edema.71, 72, 73 Mechanism which CN‐105 reduced early mortality were likely through decreasing overall infarct size, as observed in our study, and also through decreasing cerebral edema by maintaining BBB integrity. Inflammation begins within hours in the postischemic brain,74, 75 resulting in activation of microglial and secretion of inflammatory cytokines within 24 h of infarction.76 These inflammatory cytokines contributes to cerebral edema through disruption of BBB integrity.77 Additionally, through the downregulation of phophorylation of CypA, as demonstrated in our phosphoproteomic results, CN‐105 also maintains BBB integrity, reducing cerebral edema after injury. All these factors contributes to the reduction in early mortality.

Other differentially phosphorylated proteins may also provide clue toward CN‐105′s mechanism of action. For example, CN‐105 may suppress microglial activation through the deactivation of Lyn. Lyn belongs to the Src family of tyrosine kinases predominantly expressed in granulocytes78 and involved in early B‐cell signaling pathway.79 Inhibition of Lyn showed suppression of microglial activation in an Alzheimer's disease model.80 Phosphorylation at tyrosine 397 (p‐Tyr397‐Lyn) is required for Lyn to perform its functional kinase activity81 to effect downstream proinflammatory pathways.79 Hence our observation of downregulation of p‐Tyr397‐Lyn suggests a possible mechanism by which CN‐105 reduces microglial activation. Moreover, Lyn activation has been implicated in degranulation of mast cells82 releasing histamine, consistent with our previous observation that apoE‐deficient mice possess elevated histamine after acute brain injury.83

Our study was limited by the inability to demonstrate improved functional outcome when CN‐105 was administered at 0.1 mg/kg beyond a latency of 30 min from ischemia. Although the protective effect of CN‐105 appears to be time‐dependent, our study was focused on delineating the early mechanistic effects of CN‐105 in ischemic stroke, and did not test the effects of higher drug dosage or multiple dosing, which have increased efficacy in prior studies.32 Since CN‐105 does not include the polymorphic region of the apoE holoprotein, the differential effects of ApoE isoforms were not investigated. An inherent limitation of the phosphoproteomic approach was the use of a twofold cutoff to determine significance between treatment groups. This could have excluded certain important phosphopeptides, with small initial changes, that may be associated with amplified downstream neuroprotective effects. The efficacy of CN‐105 would also have been further enhanced if evaluated in different models of ischemic stroke and female mice. Additionally, to elucidate if CN‐105 works definitively through LRP1, antagonism or genetic knock‐out models of LRP1 will be needed.

In summary, we demonstrate that intravenous administration of CN‐105 conferred durable sensorimotor functional improvements, reduced mortality, histological inflammation, and inflammatory phosphoproteomic signals following cerebral ischemia. In vitro application of CN‐105 also reduced microglial activation. With safety already demonstrated in a clinical trial, CN‐105 may be an attractive candidate for further clinical evaluation in ischemic stroke.

Author Contributions

T.M.T. designed the study, performed the in vivo experiments and functional testing, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. B.J.K. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. E.J.S designed, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. V.C. contributed to the in vivo experiments, immunohistochemistry assessments and wrote the manuscript. P.F. performed the in vitro experiments and wrote the manuscript. H.W. designed the study and contributed to the animal experiments. M.A.M. had scientific oversight of the proteomic component. H.N.D. assisted the study design, immunohistochemistry assessment, and edited the manuscript. D.T.L. designed the study, acquired grant, supervised the work, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the full manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

D.T.L, B.J.K, and H.N.D are co‐inventors of CN‐105 with US patent 9,303,063. D.T.L serves as an officer for Aegis‐CN, LLC. Aegis‐CN, LLC supplied the drug, but had no editorial control over study design, conduct, or writing of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Data S1. Physiological studies of CN‐105.

Data S2. Supplemental methods.

Data S3. Supplemental results.

Table S1. Principal biological process of differentially significant phosphoproteins.

Table S2. Known cell signaling pathways of differentially expressed phosphoproteins.

Table S3. Biological functions of phosphoproteins that are significantly different between CN‐105 and vehicle in ischemic stroke.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gregg Waitt (Duke Proteomics Core Facility, Duke University) for technical assistance in the proteomic component of this study. This work was supported by a grant from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center (2014‐CFG‐8004) to D.T.L and by the Ministry of Health, Singapore through the National Medical Research Council Research Training Fellowship (NMRC/Fellowship/0012/2015) supporting T.M.T.. We also thank MPI Research (5493 North Main Street, Mattawan, MI) for conducting physiological studies of CN‐105.

[The copyright line for this article was changed on 25 April 2017 after original online publication]

References

- 1. Kim AS, Johnston SC. Global variation in the relative burden of stroke and ischemic heart disease. Circulation 2011;124:314–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thrift AG, Cadilhac DA, Thayabaranathan T, et al. Global stroke statistics. Int J Stroke 2014;9:6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, et al. 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Focused update of the 2013 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke regarding endovascular treatment: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2015;46:3020–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Timeliness of tissue‐type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door‐to‐needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation 2011;123:750–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tong D, Reeves MJ, Hernandez AF, et al. Times from symptom onset to hospital arrival in the Get with the Guidelines‐Stroke Program 2002 to 2009: temporal trends and implications. Stroke 2012;43:1912–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Skolarus LE, Meurer WJ, Shanmugasundaram K, et al. Marked Regional Variation in Acute Stroke Treatment Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Stroke 2015;46:1890–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahmed N, Wahlgren N, Grond M, et al. Implementation and outcome of thrombolysis with alteplase 3‐4.5 h after an acute stroke: an updated analysis from SITS‐ISTR. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:866–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanrahan F, Campbell M. Neuroinflammation In: D Laskowitz, G Grant, eds. Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury. Boca Raton (FL):CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shichita T, Ito M, Yoshimura A. Post‐ischemic inflammation regulates neural damage and protection. Front Cell Neurosci 2014;8:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fu Y, Liu Q, Anrather J, Shi FD. Immune interventions in stroke. Nat Rev Neurol 2015;11:524–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krishnamurthy K, Laskowitz DT. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of secondary neuronal injury following traumatic brain injury In: D Laskowitz, G Grant, eds. Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury. Boca Raton (FL):CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iadecola C, Anrather J. The immunology of stroke: from mechanisms to translation. Nat Med 2011;17:796–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grupke S, Hall J, Dobbs M, et al. Understanding history, and not repeating it. Neuroprotection for acute ischemic stroke: from review to preview. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2015;129:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sutherland BA, Minnerup J, Balami JS, et al. Neuroprotection for ischaemic stroke: translation from the bench to the bedside. Int J Stroke 2012;7:407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laskowitz DT, Horsburgh K, Roses AD. Apolipoprotein E and the CNS response to injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998;18:465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laskowitz DT, Goel S, Bennett ER, Matthew WD. Apolipoprotein E suppresses glial cell secretion of TNF alpha. J Neuroimmunol 1997;76(1–2):70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laskowitz DT, Thekdi AD, Thekdi SD, et al. Downregulation of microglial activation by apolipoprotein E and apoE‐mimetic peptides. Exp Neurol 2001;167:74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu J, LaDu MJ, Van Eldik LJ. Apolipoprotein E attenuates beta‐amyloid‐induced astrocyte activation. J Neurochem 1998;71:1626–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sheng H, Laskowitz DT, Mackensen GB, et al. Apolipoprotein E deficiency worsens outcome from global cerebral ischemia in the mouse. Stroke 1999;30:1118–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duan RS, Chen Z, Dou YC, et al. Apolipoprotein E deficiency increased microglial activation/CCR3 expression and hippocampal damage in kainic acid exposed mice. Exp Neurol 2006;202:373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aono M, Lee Y, Grant ER, et al. Apolipoprotein E protects against NMDA excitotoxicity. Neurobiol Dis 2002;11:214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laskowitz DT, Sheng H, Bart RD, et al. Apolipoprotein E‐deficient mice have increased susceptibility to focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1997;17:753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McColl BW, McGregor AL, Wong A, et al. APOE epsilon3 gene transfer attenuates brain damage after experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007;27:477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weisgraber KH. Apolipoprotein E: structure‐function relationships. Adv Protein Chem 1994;45:249–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou W, Xu D, Peng X, et al. Meta‐analysis of APOE4 allele and outcome after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2008;25:279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. James ML, Blessing R, Bennett E, Laskowitz DT. Apolipoprotein E modifies neurological outcome by affecting cerebral edema but not hematoma size after intracerebral hemorrhage in humans. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;18:144–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verghese PB, Castellano JM, Holtzman DM. Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's disease and other neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:241–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martinez‐Gonzalez NA, Sudlow CL. Effects of apolipoprotein E genotype on outcome after ischaemic stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:1329–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Misra UK, Adlakha CL, Gawdi G, et al. Apolipoprotein E and mimetic peptide initiate a calcium‐dependent signaling response in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 2001;70:677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aono M, Bennett ER, Kim KS, et al. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E‐mimetic peptides on N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate excitotoxicity in primary rat neuronal‐glial cell cultures. Neuroscience 2003;116:437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tukhovskaya EA, Yukin AY, Khokhlova ON, et al. COG1410, a novel apolipoprotein‐E mimetic, improves functional and morphological recovery in a rat model of focal brain ischemia. J Neurosci Res 2009;87:677–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang H, Anderson LG, Lascola CD, et al. ApolipoproteinE mimetic peptides improve outcome after focal ischemia. Exp Neurol 2013;241:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. James ML, Sullivan PM, Lascola CD, et al. Pharmacogenomic effects of apolipoprotein e on intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2009;40:632–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laskowitz DT, Lei B, Dawson HN, et al. The apoE‐mimetic peptide, COG1410, improves functional recovery in a murine model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2012;16:316–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lei B, James ML, Liu J, et al. Neuroprotective pentapeptide CN‐105 improves functional and histological outcomes in a murine model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Sci Rep 2016;6:34834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lynch JR, Wang H, Mace B, et al. A novel therapeutic derived from apolipoprotein E reduces brain inflammation and improves outcome after closed head injury. Exp Neurol 2005;192:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoane MR, Pierce JL, Holland MA, et al. The novel apolipoprotein E‐based peptide COG1410 improves sensorimotor performance and reduces injury magnitude following cortical contusion injury. J Neurotrauma 2007;24:1108–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laskowitz DT, McKenna SE, Song P, et al. COG1410, a novel apolipoprotein E‐based peptide, improves functional recovery in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2007;24:1093–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoane MR, Kaufman N, Vitek MP, McKenna SE. COG1410 improves cognitive performance and reduces cortical neuronal loss in the traumatically injured brain. J Neurotrauma 2009;26:121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang H, Durham L, Dawson H, et al. An apolipoprotein E‐based therapeutic improves outcome and reduces Alzheimer's disease pathology following closed head injury: evidence of pharmacogenomic interaction. Neuroscience 2007;144:1324–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cao F, Jiang Y, Wu Y, et al. Apolipoprotein E‐mimetic COG1410 reduces acute vasogenic edema following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2016;33:175–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu Y, Pang J, Peng J, et al. An apoE‐derived mimic peptide, COG1410, alleviates early brain injury via reducing apoptosis and neuroinflammation in a mouse model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosci Lett 2016;627:92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gao J, Wang H, Sheng H, et al. A novel apoE‐derived therapeutic reduces vasospasm and improves outcome in a murine model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2006;4:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mesis RG, Wang H, Lombard FW, et al. Dissociation between vasospasm and functional improvement in a murine model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurg Focus 2006;21:E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gu Z, Li F, Zhang YP, et al. Apolipoprotein E mimetic promotes functional and histological recovery in lysolecithin‐induced spinal cord demyelination in mice. J Neurol Neurophysiol 2013;2014(Suppl 12):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang R, Hong J, Lu M, et al. ApoE mimetic ameliorates motor deficit and tissue damage in rat spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Res 2014;92:884–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guptill JT, Raja SM, Boakye‐Agyeman F, et al. Phase 1 randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study to determine the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of a single escalating dose and repeated doses of CN‐105 in healthy adult subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 2016; e‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aartsma‐Rus A, van Putten M. Assessing functional performance in the mdx mouse model. J Vis Exp 2014;Mar 27;(85). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang F, Chen J. Infarct measurement in focal cerebral ischemia: TTC Staining In: Chen J, Xu X‐M, Xu ZC, Zhang JH, eds. Animal models of acute neurological injuries II: injury and mechanistic assessments. vol. 2 Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2012:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 50. West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in the subdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat Rec 1991;231:482–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Day EK, Sosale NG, Lazzara MJ. Cell signaling regulation by protein phosphorylation: a multivariate, heterogeneous, and context‐dependent process. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2016;40:185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lynch JR, Tang W, Wang H, et al. APOE genotype and an ApoE‐mimetic peptide modify the systemic and central nervous system inflammatory response. J Biol Chem 2003;278:48529–48533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Laskowitz DT, Fillit H, Yeung N, et al. Apolipoprotein E‐derived peptides reduce CNS inflammation: implications for therapy of neurological disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2006;185:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lynch JR, Morgan D, Mance J, et al. Apolipoprotein E modulates glial activation and the endogenous central nervous system inflammatory response. J Neuroimmunol 2001;114(1–2):107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Guttman M, Prieto JH, Handel TM, et al. Structure of the minimal interface between ApoE and LRP. J Mol Biol 2010;398:306–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Croy JE, Brandon T, Komives EA. Two apolipoprotein E mimetic peptides, ApoE(130‐149) and ApoE(141‐155)2, bind to LRP1. Biochemistry 2004;43:7328–7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bell RD, Winkler EA, Singh I, et al. Apolipoprotein E controls cerebrovascular integrity via cyclophilin A. Nature 2012;485:512–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci 2007;10:1387–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A, Hofer M. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: therapeutic approaches. J Transl Med 2009;7:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pocivavsek A, Burns MP, Rebeck GW. Low‐density lipoprotein receptors regulate microglial inflammation through c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase. Glia 2009;57:444–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zlokovic BV. Cerebrovascular effects of apolipoprotein E: implications for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:440–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Waetzig V, Herdegen T. Neurodegenerative and physiological actions of c‐Jun N‐terminal kinases in the mammalian brain. Neurosci Lett 2004;361(1–3):64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Moon SY, Zheng Y. Rho GTPase‐activating proteins in cell regulation. Trends Cell Biol 2003;13:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Coso OA, Chiariello M, Yu JC, et al. The small GTP‐binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42 regulate the activity of the JNK/SAPK signaling pathway. Cell 1995;81:1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sbarbati A, Reggiani A, Nicolato E, et al. Regional changes in the contralateral “healthy” hemisphere after ischemic lesions evaluated by quantitative T2 parametric maps. Anat Rec 2002;266:118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bejot Y, Prigent‐Tessier A, Cachia C, et al. Time‐dependent contribution of non neuronal cells to BDNF production after ischemic stroke in rats. Neurochem Int 2011;58:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hafezi‐Moghadam A, Thomas KL, Wagner DD. ApoE deficiency leads to a progressive age‐dependent blood‐brain barrier leakage. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007;292:C1256–C1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Methia N, Andre P, Hafezi‐Moghadam A, et al. ApoE deficiency compromises the blood brain barrier especially after injury. Mol Med 2001;7:810–815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lynch JR, Pineda JA, Morgan D, et al. Apolipoprotein E affects the central nervous system response to injury and the development of cerebral edema. Ann Neurol 2002;51:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhu C, Wang X, Deinum J, et al. Cyclophilin A participates in the nuclear translocation of apoptosis‐inducing factor in neurons after cerebral hypoxia‐ischemia. J Exp Med 2007;204:1741–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hacke W, Schwab S, Horn M, et al. ‘Malignant’ middle cerebral artery territory infarction: clinical course and prognostic signs. Arch Neurol 1996;53:309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Braga P, Ibarra A, Rega I, et al. Prediction of early mortality after acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2002;11:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Qureshi AI, Suarez JI, Yahia AM, et al. Timing of neurologic deterioration in massive middle cerebral artery infarction: a multicenter review. Crit Care Med 2003;31:272–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J Leukoc Biol 2010;87:779–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Amantea D, Nappi G, Bernardi G, et al. Post‐ischemic brain damage: pathophysiology and role of inflammatory mediators. FEBS J 2009;276:13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schilling M, Besselmann M, Leonhard C, et al. Microglial activation precedes and predominates over macrophage infiltration in transient focal cerebral ischemia: a study in green fluorescent protein transgenic bone marrow chimeric mice. Exp Neurol 2003;183:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sandoval KE, Witt KA. Blood‐brain barrier tight junction permeability and ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Dis 2008;32:200–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Corey SJ, Anderson SM. Src‐related protein tyrosine kinases in hematopoiesis. Blood 1999;93:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Mills D, et al. B cell antigen receptor signaling 101. Mol Immunol 2004;41(6–7):599–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Manocha GD, Puig KL, Austin SA, et al. Characterization of novel Src family kinase inhibitors to attenuate microgliosis. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0132604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ingley E. Src family kinases: regulation of their activities, levels and identification of new pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1784:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Xiao W, Nishimoto H, Hong H, et al. Positive and negative regulation of mast cell activation by Lyn via the FcepsilonRI. J Immunol 2005;175:6885–6892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mace BE, Wang H, Lynch JR, et al. Apolipoprotein E modifies the CNS response to injury via a histamine‐mediated pathway. Neurol Res 2007;29:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Physiological studies of CN‐105.

Data S2. Supplemental methods.

Data S3. Supplemental results.

Table S1. Principal biological process of differentially significant phosphoproteins.

Table S2. Known cell signaling pathways of differentially expressed phosphoproteins.

Table S3. Biological functions of phosphoproteins that are significantly different between CN‐105 and vehicle in ischemic stroke.