Abstract

Dietary supplements sold for weight loss (WL), muscle building (MB), and sexual function (SF) are not medically recommended. They have been shown to be ineffective in many cases and pose serious health risks to consumers due to adulteration with banned substances, prescription pharmaceuticals, and other dangerous chemicals. Yet no prior research has investigated how these products may disproportionately burden individuals and families by gender and socioeconomic position across households. We investigated household (HH) cost burden of dietary supplements sold for WL, MB, and SF in a cross-sectional study using data from 60,538 U.S. households (HH) in 2012 Nielsen/IRi National Consumer Panel, calculating annual HH expenditures on WL, MB, and SF supplements and expenditures as proportions of total annual HH income. We examined sociodemographic patterns in HH expenditures using Wald tests of mean differences across subgroups. Among HH with any expenditures on WL, MB, or SF supplements, annual HH first and ninth expenditure deciles were, respectively: WL $5.99, $145.36; MB $6.99, $141.93; and SF $4.98, $88.52. Conditional on any purchases of the products, female-male-headed HH spent more on WL supplements and male-headed HH spend more on MB and SF supplements compared to other HH types (p-values < 0.01). High-income ($30,000 < annual income < $100,000), compared to low-income (annual income < $30,000) HH, spent more on all three supplements types (p-values < 0.01); however, proportional to income, low-income HH spent 2–4 times more than high-income HH on WL and MB supplements (p-values < 0.01). Dietary supplements sold for WL, MB, and SF disproportionately burden HH by income and gender.

Keywords: Dietary supplements, Weight loss, Muscle building, Sexual function, Disparities

Highlights

-

•

Female-male-headed households spend more than others on weight-loss supplements.

-

•

Male-headed households spend more than others on muscle-building and sexual-function supplements.

-

•

Low-income households bear the heaviest financial burden in terms of proportion of household income spent.

1. Introduction

The dietary supplement industry in the United States is a growing, multi-billion dollar industry. Dietary supplements, which include vitamins, minerals, herbs, and amino acids, are widely used by adults and children of all ages. In fact, Americans spent an estimated $36.7 billion on dietary supplements in 2014 (Anonymous, 2015). Dietary supplements sold for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function are commonly used. Americans spent $2 billion in 2015 on dietary supplements for weight loss (Anonymous, 2014), which is among the most common reasons for dietary supplement use (Bailey et al., 2013). Americans spent $2.6 billion on muscle-building products in 2015 (McKenna, 2015). There is also a substantial market for dietary supplements promising enhanced sexual function. Recently, one manufacturer was found to produce over one million capsules per month of a supplement sold for sexual functioning, netting more than $2 million dollars in three years. The global sexual-function supplement industry likely generates tens of millions, if not billions, of dollars yearly (Canham, 2011, Cohen and Venhuis, 2013, Szalavitz, 2013).

Despite their widespread use, dietary supplements for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function are not medically recommended and have been shown to be ineffective in many cases (Steffen et al., 2007, Roerig et al., 2003, Blanck et al., 2007) and to pose serious health risks to consumers due to adulteration with banned substances, prescription pharmaceuticals, and other dangerous chemicals (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2010, Cui et al., 2015). In fact, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has been well aware of this heightened risk for many years, and in 2010 issued a special warning to consumers regarding supplements sold for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function as being more likely than other supplements to be deceptively marketed and tainted with toxic ingredients (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2010). Effects with adverse health consequences can include for weight-loss supplements: chronic diarrhea and constipation, dehydration, hypokalemia, metabolic acidosis, and other electrolyte imbalances, cardiac arrhythmia, hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke, hepatic and renal failure; (Steffen et al., 2007, Roerig et al., 2003, Schneider, 2003, Copeland, 1994, Tozzi et al., 2006, Vanderperren et al., 2005, Crow, 2005) for muscle-building supplements: infertility, testicular cancer, stunted growth, coronary artery disease, pulmonary embolism; (Liyanage and Kodali, 2014, Li et al., 2015) and for sexual-function supplements: changes in blood pressure, hypomania, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, nausea, headaches, loss of consciousness, seizures (Cohen and Venhuis, 2013, Corazza et al., 2014).

With the serious health risks of dietary supplements sold for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function well-documented, there is concern that economic costs of these products may disproportionately burden individuals and families by gender and socioeconomic position. A recent national study found 21% of women and 10% of men had used weight-loss supplements at some point in their lives, with women ages 18–34 years having the highest rate of past year use at 17%, affecting many millions of Americans (Blanck et al., 2007). A different study assessing use of muscle-building products among adolescents found that 35% of boys had used protein powder in the past year and 11% had used other products including dietary supplements sold for muscle-building. On the other hand, 21% of girls had used protein powder in the past year and 6% had used other products including supplements sold for muscle-building (Eisenberg et al., 2012).

In the U.S. nationally representative National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Kakinami and colleagues found that compared to adults in high-income households, those in low-to-middle income households were more likely to use weight-loss strategies in the past year inconsistent with medical recommendations, such using as non-prescription diet pills, which are likely to include dietary supplements, as they comprise the vast majority of over-the-counter diet pills on the U.S. market (Kakinami et al., 2014). In another nationally representative study of U.S. adults, Pillitteri and colleagues similarly found that among adults who had ever attempted to lose weight, those in low-to-middle income households were more likely than those in higher-income households to use dietary supplements for weight loss (42% vs. 30%) (Pillitteri et al., 2008). They also found in this same sample that adults with high school or less education were more likely than those with at least some college education to use dietary supplements for weight loss (38% vs. 31%) and found higher use among African American (49%) and Latino (42%) adults compared to white adults (31%) (Pillitteri et al., 2008). We are not aware of any studies assessing the association between income and dietary supplement use for muscle building or sexual function.

Given these gaps in the literature, the objectives of our study were to estimate the proportion of household income in the United States spent on dietary supplements sold for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function as related to gender of household head and household annual income.

2. Methods

The primary data source, from which information on U.S. household purchases of dietary supplements was aggregated, was the observational 2012 Nielsen/IRi National Consumer Panel (NCP) (Nielsen/IRi, 2012). The dataset, administered by the Kilts Center at the University of Chicago, is a sample of > 60,000 U.S. households that in 2012 were asked to provide complete information on household purchases labeled with a scannable universal product codes (UPC). The NCP draws from all U.S. states and major metropolitan areas, which allowed us to produce national-level projections using NCP-calculated projection factors. The NCP database includes no identifiable information; therefore, this study is not considered human subjects research.

To augment information on dietary supplements listed in the NCP as having been purchased by participating households, we collected data on products with packaging and advertising making claims in at least one of three categories: weight loss, muscle building, or sexual function. To identify these characteristics, we conducted web searches by UPC, product brand, and product description, registering whether each product included each claim. The collected product claims data were merged into the NCP at the product level by matching collected UPCs with those recorded in the NCP database, at the product level. Then, all purchases for each household, as identified in the UPC merge, were aggregated according to the relevant measure, e.g., sum for total expenditure or an indicator value for any expenditure. This was done separately for each claim-type category. The analytic sample consisted of 60,538 households, which is all households included in the 2012 panel year.

The primary measure of interest is household-level expenditures within each product category during 2012. As described below, we also analyzed this measure across household types according to the gender(s) of the household head(s) and annual household income. There were 15,796 households reporting a female head only, 6112 reporting a male head only, and 38,630 reporting a female and male head. In addition, 13,470 households reported earning less than $30,000 in the prior tax year and 47,068 households reported earning more than $30,000 in the prior tax year.

Household-level expenditures were summarized in two ways. Whether or not a household purchased a product in a particular category (e.g., weight loss, muscle building, or sexual function) were coded as 1 or 0, so the estimated means represent percent of households reporting any purchases. Statistics that report conditional expenditure are calculated as mean values, conditional on a household having made any purchases of a product in one of the three dietary supplement categories under study (i.e., weight loss, muscle building, or sexual function). Thus, conditional estimates were based on the subset of the household population that purchased at least one product in a category. In addition, household expenditure greater than or equal to $250 on weight-loss (N = 659), muscle-building (N = 362), or sexual-function (N = 27) products were considered outliers and removed for relevant product type.

To prepare for estimates of a household's income share that was spent on products in each category, household income was imputed as the midpoint of the reported household income category. Recorded income category increments ranged from $3000 (for low income categories) to $20,000 (for high income categories), and the highest income category in the NCP database was $100,000 or more. Because the highest income category did not have a midpoint, households in this category (N = 9039) were excluded from income share estimates.

All analyses were cross-sectional, and statistics are reported in both weighted and unweighted estimates. Weighted estimates were constructed using projection factors provided by NCP, where the primary sampling unit was the household-year, and the sample was stratified by markets and census regions. We examined differences in weighted estimates using Wald tests. Some of the difference estimates may not satisfy the normality assumption of the Wald test; therefore, we also report results using unweighted estimates and corresponding nonparametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests that the samples are drawn from the from the same population.

As sensitivity analyses, we compared findings from analytic sample when outliers were removed, as described above, to findings when outliers were retained. Associations were not qualitatively different; therefore, results presented are based on the analytic sample exclusive of outliers.

3. Results

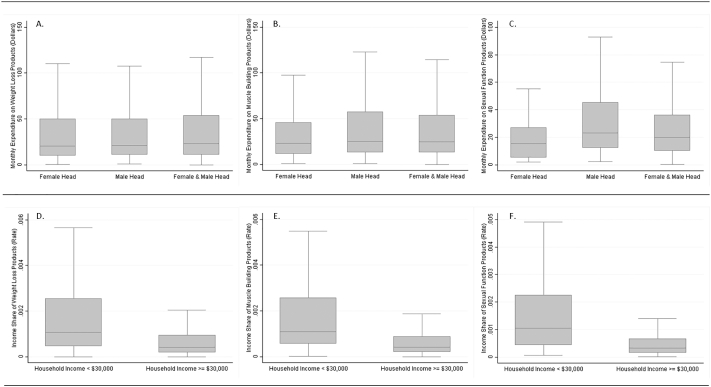

Table 1 presents estimates of the percent of households purchasing any products, and household expenditures conditional on any purchases, for each of the three supplement categories and each household head type. Among households with any expenditures on weight- loss, muscle-building, or sexual-function supplements, annual households first and ninth expenditure deciles were: weight loss $5.99 and $145.36; muscle building $6.99 and $141.93; and sexual function $4.98 and $88.52. In Fig. 1, panels A–C present the monthly expenditure of households on weight-loss, muscle-building, and sexual-function products, respectively, by household head type among households that purchased the products.

Table 1.

Household expenditure on dietary supplements sold for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function by household head.

| Female head only | Male head only | Female and male head | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss | Any purchases (weighted) | 21.3% | 16.2% | 20.6% |

| Wald p-value | 0.000 | 0.254 | ||

| N | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | |

| Any purchases (unweighted) | 21.4% | 15.7% | 22.3% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.030 | ||

| N | 15,796 | 6112 | 38,630 | |

| Conditional expenditure (weighted) | $58.06 | $63.95 | $62.18 | |

| Wald p-value | 0.339 | 0.267 | ||

| N | 12,962 | 12,962 | 12,962 | |

| Conditional expenditure (unweighted) | $65.59 | $61.92 | $66.56 | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.986 | 0.012 | ||

| N | 3388 | 960 | 8614 | |

| Muscle building | Any purchases (weighted) | 11.4% | 13.2% | 13.4% |

| Wald p-value | 0.005 | 0.685 | ||

| N | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | |

| Any purchases (unweighted) | 11.3% | 12.4% | 13.5% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.028 | 0.023 | ||

| N | 15,796 | 6112 | 38,630 | |

| Conditional expenditure (weighted) | $51.49 | $88.66 | $58.99 | |

| Wald p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 7751 | 7751 | 7751 | |

| Conditional expenditure (unweighted) | $54.41 | $89.13 | $63.54 | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.042 | ||

| N | 1791 | 758 | 5202 | |

| Sexual function | Any purchases (weighted) | 0.9% | 2.8% | 2.0% |

| Wald p-value | 0.000 | 0.003 | ||

| N | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | |

| Any purchases (unweighted) | 0.8% | 2.8% | 2.0% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 15,796 | 6112 | 38,630 | |

| Conditional expenditure (weighted) | $33.35 | $71.66 | $38.17 | |

| Wald p-value | N/Aa | N/Aa | ||

| N | 1073 | 1073 | 1073 | |

| Conditional expenditure (unweighted) | $30.87 | $67.98 | $41.21 | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.012 | ||

| N | 128 | 169 | 776 |

Missing standard errors because of stratum with single sampling unit.

Fig. 1.

Income share and monthly expenditure of weight-loss (WL), muscle-building (MB), and sexual-function (SF) products by household income and household head from 2012 Nielsen/IRi National Consumer Panel (N = 60,538 total households). Household expenditure greater than or equal to $250 on WL, MB, or SF products considered outliers and removed for relevant product type.

A. Income share of WL products by household income

B. Income share of MB products by household income

C. Income share of SF products by household income

D. Monthly expenditure of WL products by household head

E. Monthly expenditure of MB products by household head

F. Monthly expenditure of SF products by household head.

Households with a female head only were most likely to purchase weight-loss products, with 21.3% reporting any purchases compared with 16.2% (p-value < 0.0001) for households with a male head only and 20.6% (p-value = 0.25) for households with a female and male head. Conditional on any purchases, however, female-only households did not spend differently from other household types on weight-loss supplements. Unweighted estimates showed a similar pattern, although female-only households were significantly less likely to purchase (p-value = 0.03) and, conditional on any purchases, spent significantly less on weight-loss products than female-male households (p-value = 0.01).

Male-only households were generally more likely to purchase and spent conditionally more on muscle-building supplement products. The only exception to that pattern is that male-only households were slightly less likely to purchase muscle-building supplement products than female-male households. Male-only households spent a weighted average of $88.66 when purchasing any muscle-building supplement products, while female-only households spent $51.29 (p-value < 0.0001) and female-male households spent $58.99 (p-value = 0.0003).

A smaller percent of households purchased sexual-function supplements than purchased weight-loss or muscle-building supplements: male-only households were the most likely among household types with a weighted percent of 2.8% compared with female-only households at 0.9% (p-value < 0.0001) and female-male households at 2.0% (p-value = 0.003). A similar pattern emerged for conditional expenditures, in which male-only households spent a weighted average of $71.66, nearly twice that of each of the other household types.

Table 2 details purchase patterns across household types and product categories while also separately analyzing households reporting less than $30,000 in annual income vs. households reporting greater than or equal to $30,000 but less than $100,000 in annual income. In Fig. 1, panels D–F present the income share of weight-loss, muscle-building, and sexual-function products, respectively, by household income among households that purchased the products.

Table 2.

Household expenditure on dietary supplements sold for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function by household income (< 30 k or ≥ 30 k).

| Weight loss |

Muscle building |

Sexual function |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HH Inc < 30 k |

HH Inc ≥ 30 k |

HH Inc < 30 k |

HH Inc ≥ 30 k |

HH Inc < 30 k |

HH Inc ≥ 30 k |

||

| All households | Any purchases (weighted) | 17.8% | 20.8% | 8.6% | 14.5% | 1.7% | 1.9% |

| Wald p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.212 | ||||

| N | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | |

| Any purchases (unweighted) | 18.6% | 22.2% | 9.1% | 13.9% | 1.7% | 1.8% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.384 | ||||

| N | 13,470 | 47,068 | 13,470 | 47,068 | 13,470 | 47,068 | |

| Conditional proportional expenditure (weighted) | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.1% | |

| Wald p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | N/Aa | ||||

| N | 10,818 | 10,818 | 6170 | 6170 | 927 | 927 | |

| Conditional proportional expenditure (unweighted) | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 2502 | 8316 | 1222 | 4948 | 227 | 700 | |

| Female head only | Any purchases (weighted) | 19.7% | 22.7% | 8.4% | 14.0% | 0.8% | 1.0% |

| Wald p-value | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.390 | ||||

| N | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | |

| Any purchases (unweighted) | 19.5% | 22.9% | 8.9% | 13.1% | 0.8% | 0.8% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.853 | ||||

| N | 6668 | 9128 | 6668 | 9128 | 6668 | 9128 | |

| Conditional proportional expenditure (weighted) | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | |

| Wald p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | N/Aa | ||||

| N | 10,818 | 10,818 | 6170 | 6170 | 927 | 927 | |

| Conditional proportional expenditure (unweighted) | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 1297 | 1897 | 596 | 1069 | 53 | 71 | |

| Male head only | Any purchases (weighted) | 12.7% | 18.2% | 8.5% | 15.8% | 2.9% | 2.7% |

| Wald p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.648 | ||||

| N | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | |

| Any purchases (unweighted) | 12.8% | 17.1% | 8.7% | 14.2% | 2.8% | 2.7% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.824 | ||||

| N | 2013 | 4099 | 2013 | 4099 | 2013 | 4099 | |

| Conditional proportional expenditure (weighted) | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.7% | 0.6% | |

| Wald p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | N/Aa | ||||

| N | 10,818 | 10,818 | 6170 | 6170 | 927 | 927 | |

| Conditional proportional expenditure (unweighted) | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.2% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 258 | 574 | 175 | 445 | 57 | 93 | |

| Female and male head | Any purchases (weighted) | 19.3% | 20.9% | 9.1% | 14.2% | 1.9% | 2.0% |

| Wald p-value | 0.122 | 0.000 | 0.940 | ||||

| N | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | 60,538 | |

| Any purchases (unweighted) | 19.8% | 22.7% | 9.4% | 14.0% | 2.4% | 1.9% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.022 | ||||

| N | 4789 | 33,841 | 4789 | 33,841 | 4789 | 33,841 | |

| Conditional proportional expenditure (weighted) | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | |

| Wald p-value | 0.001 | 0.000 | N/Aa | ||||

| N | 10,818 | 10,818 | 6170 | 6170 | 927 | 927 | |

| Conditional proportional expenditure (unweighted) | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | |

| Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 947 | 5845 | 451 | 3434 | 117 | 536 | |

Missing standard errors because of stratum with single sampling unit.

When comparing across income categories, there were broadly similar qualitative patterns for weight-loss and muscle-building products. In general, higher income households (i.e., $30,000 < annual income < $100,000) were more likely to make any purchase of weight-loss and muscle-building supplement products across all household-head types. We also calculated the conditional expenditure share of income for each subcategory, and we broadly identified that lower-income households spent more as a share of income, typically 2 to 4 times, than higher-income households. All comparisons for these subcategories yielded p-values < 0.01.

Most comparisons across income categories for sexual-function products showed similar patterns in the point estimates as for weight-loss and muscle-building supplement products, but many of the comparison tests were not statistically significant. We were unable to calculate weighted conditional expenditure shares of income because of the presence of a stratum with a single sampling unit.

4. Discussion

Dietary supplements sold for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function have been flagged by the FDA as among the most likely of all supplement categories to be contaminated with dangerous ingredients and therefore among the most risky for consumers, (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2010) and yet they continue to be ubiquitously available in pharmacies, grocery stores, gyms, and many other brick-and-mortar and online retailers (Cohen, 2014, Pomeranz et al., 2015). Our study findings indicate that the financial burden of these industries borne by households is unevenly distributed by annual income and gender of head of household. While wealthier households spend more on these products in absolute dollars, it is low-income households that bear the heaviest financial burden for these products in terms of proportion of household income. In addition, conditional on any purchases of the products, female-male-headed households spent more on weight-loss supplements and male-headed households spend more on muscle-building and sexual-function supplements compared to other household types.

Prior research has similarly found evidence of social inequities in the burden these products pose, with two U.S. nationally representative studies finding lower-income adults more likely than their wealthier peers to use dietary supplements for weight loss (Pillitteri et al., 2008) and diet pills without a prescription, which is likely to include use of dietary supplements (Kakinami et al., 2014). Prior research has also found gender differences in the use of these products, with females more likely to use weight-loss supplements and males more likely to use muscle-building supplements (Blanck et al., 2007, Eisenberg et al., 2012, Pillitteri et al., 2008). Though we were not able to find epidemiologic studies estimating the prevalence by gender of use of sexual-function supplements, these products are primarily marketed to men (Cui et al., 2015). As might be expected, we found male-only headed households were more likely to purchase these products than other household types.

This study has several limitations. Data were gathered on the household level, which is informative as to how household income is allocated to different types of product purchases, but does not provide insight into who is using the products. Also, while the database provides information on how much money was spent by any household on particular products, the database does not include a direct measure of product consumption, nor does it indicate whether the products were consumed by one person or shared among two or more household members. In addition, because annual household income and annual product spending data are highly skewed, we chose to exclude the top category of household income (annual income ≥$100,000) and the approximately top two percentiles, depending on product type, of highest spending households (expenditure ≥$250) from our analyses. For this reason, findings should not be interpreted to apply to the highest category groups in terms of household income or spending. Furthermore, in many cases we were unable to obtain precise estimates for sexual-function products, due in part to the relatively small sample of households with any purchases. Social desirability bias may have occurred if consumers chose not to scan some products they purchased in a way that was differential by gender of household head or household income.

5. Conclusions

Dietary supplements sold for weight loss, muscle building, and sexual function are purchased by a range of household types defined by gender of household head and annual household income. These products, which have been flagged by the FDA as particularly dangerous, disproportionately burden households by income and gender. Greater attention is urgently needed to improve regulation and protect consumers from these noxious products.

Author information

S. Bryn Austin is with the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, and the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Kimberly Yu is with the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA. Selena H. Liu is with the Department of Nutrition, Simmons College, Boston, MA. Fan Dong and Nathan Tefft are with the Department of Economics, Bates College, Lewiston, ME. Austin, Yu, and Liu are with the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

Contributors

S.B. Austin and N. Tefft were responsible for study conception, database creation, analyses, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. K. Yu, S.H. Liu, and F. Dong were responsible for database creation, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Human participant protection

The study database includes no identifiable information; therefore, this study is not human subjects research.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Transparency Document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work has been provided by the Ellen Feldberg Gordon Challenge Fund for Eating Disorders Prevention Research, the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders, and training grants T71-MC-00009 and T76-MC-00001 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. We would like to thank Rose Billeci, Jayme Holliday, Michael Varner, and Kathryn Webber for their help in database creation and preparation.

Footnotes

The Transparency Document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- Anonymous NBJ's supplement business report. Nutr. Bus. J. 2015:2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Is sports nutrition its own worst enemy? Nutr. Bus. J. 2014;XIX [Google Scholar]

- Bailey R.L., Gahche J.J., Miller P.E., Thomas P.R., Dwyer J.T. Why US adults use dietary supplements. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173(5):355–361. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanck H.M., Serdula M.K., Gillespie C. Use of nonprescription dietary supplements for weight loss is common among Americans. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007;107:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canham M. Salt Lake City Tribune. 2011. Feds plow new ground in spiked supplement case. 2011 Oct. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P.A. Hazards of hindsight — monitoring the safety of nutritional supplements. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370(14):1277–1280. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P.A., Venhuis B.J. Adulterated sexual enhancement supplements more than just mojo. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173(13):1169–1170. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland P.M. Renal failure associated with laxative abuse. Psychother. Psychosom. 1994;62(3–4):200–202. doi: 10.1159/000288923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corazza O., Martinotti G., Santacroce R. Sexual enhancement products for sale online: raising awareness of the psychoactive effects of yohimbine, maca, horny goat weed, and ginko biloba. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2014/841798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow S. Medical complications of eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S., Mitchell J., de Zwaan M., Steiger H., editors. Eating Disorders Review, Part 1. Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.; Abingdon, U.K.: 2005. pp. 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cui T., Kovell R.C., Brooks D.C., Terlecki R.P. A urologist's guide to ingredients found in top-selling nutraceuticals for men's sexual health. J. Sex. Med. 2015;12(11):2105. doi: 10.1111/jsm.13013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg M.E., Wall M., Neumark-Sztainer D. Muscle-enhancing behaviors among adolescent girls and boys. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):1019–1026. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakinami L., Gauvin L., Barnett T.A., Paradis G. Trying to lose weight: the association of income and age to weight-loss strategies in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014;46(6):585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Hauser R., Holford T. Muscle-building supplement use and increased risk of testicular germ cell cancer in men from Connecticut and Massachusetts. Br. J. Cancer. 2015;112(7):1247–1250. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage C.R.D.G., Kodali V. Bulk muscles, loose cables. BMJ Case Rep. 2014:1–2. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna F. Health Stores in the US: Market Research Report: IBISWorld Industry Report. 2015. IBISWorld Industry Report. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen/IRi. National Consumer Panel. 2012. URL: http://www.ncppanel.com/content/ncp/ncphome.html. (Date Accessed: March 8, 2017).

- Pillitteri J.L., Shiffman S., Rohay J.M., Harkins A.M., Burton S.L., Wadden T.A. Use of dietary supplements for weight loss in the United States: results of a national survey. Obesity. 2008;16:790–796. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz J.L., Barbosa G., Killian C., Austin S.B. The dangerous mix of adolescents and dietary supplements for weight loss and muscle building: legal strategies for state action. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2015;21(5):496–503. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerig J.L., Mitchell J.E., de Zwaan M. The eating disorders medicine cabinet revisited: a clinician's guid to appetite suppressants and diuretics. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003;33:443–457. doi: 10.1002/eat.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. Bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder in adolescents. Adolesc. Med. State Art Rev. 2003;14(1):119–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen K.J., Mitchell J.E., Roerig J.L., Lancaster K.L. The eating disorders medicine cabinet revisted: a clinician's guide to ipecac and laxatives. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007;40:360–368. doi: 10.1002/eat.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalavitz M. The dangers lurking in male sexual supplements. Time Mag. 2013 2013 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi T., Thornton L.M., Mitchell J. Features associated with laxative abuse in individuals with eating disorders. Psychosom. Med. 2006;68(3):470–477. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221359.35034.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Tainted Products Marketed as Dietary Supplements. 2010. URL: http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm236774.htm. (Date accessed: March 8, 2017).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Tainted Products Marketed As Dietary Supplements_CDER; 2017. URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/sda/sdNavigation.cfm?filter=&sortColumn=1d&sd=tainted_supplements_cder&page=1. (Date accessed: March 8, 2017).

- Vanderperren B., Rizzo M., Angenot L., Haufroid V., Jadoul M., Hantson P. Acute liver failure with renal impairment related to the abuse of senna anthraquinone glycosides. Ann. Pharmacother. 2005;39(7–8):1353–1357. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.