Abstract

Many physiological functions of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) have been reported in mammalian cells over the last 20 years. These physiological effects have been ascertained through in vitro treatment of cells with Na2S or NaHS, both of which are precursors of H2S. Since H2S exists as HS− in a neutral solution, a disulfide compound such as cystine could react with HS− in culture medium as well as in the cell.

This study demonstrated that after the addition of Na2S solution into culture medium, HS− was transiently generated and disappeared immediately through the reaction between HS− and cystine to form cysteine persulfides and polysulfides in the culture medium (bound sulfur mixture: BS-Mix). Furthermore, we found that the addition of Na2S solution resulted in an increase of intracellular cysteine persulfide levels in SH-SY5Y cells. This alteration in intracellular persulfide was also observed in cystine-free medium.

Considering this reaction of HS− as a precursor of BS-Mix, we highlighted the cytoprotective effect of Na2S on human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells against methylglyoxal (MG)-induced toxicity. BS-Mix produced with Na2S in cystine-containing medium provided SH-SY5Y cells significant protective effect against MG-induced toxicity. However, the protective effect was attenuated in cystine-free medium. Moreover, we observed that Na2S or BS-Mix activated the Keap1/Nrf2 system and increased glutathione (GSH) levels in the cell. In addition, the activation of Nrf2 is significantly attenuated in cystine-free medium.

These results suggested that Na2S protects SH-SY5Y cells from MG cytotoxicity through the activation of Nrf2, mediated by cysteine persulfides and polysulfides that were generated by Na2S addition.

Abbreviations: AGEs, advanced glycation end products; BS-Mix, bound sulfur mixture; BSS, bound sulfur species; CNS, central nervous system; Df, differentiated; DMB, 1,2-diamino-4,5-methylenedioxybenzene; DTT, dithiothreitol; ESI, electrospray ionization; GLO, glyoxalase; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; mBB, monobromobimane; MG, methylglyoxal; 3MST, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase; NaHS, sodium hydrogen sulfide; Na2S, sodium sulfide; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor-2; NQO1, NAD (P) H: quinone oxidoreductase; RA, retinoic acid; SSP4, sulfane sulfur probe 4; TRPA1, transient receptor potential ankyrin 1

Keywords: Polysulfide, Persulfide, Hydrogen sulfide, Bound sulfur species, Nrf2, Methylglyoxal

Highlights

-

•

Neuronal cells were protected from methylglyoxal-induced toxicity by cysteine persulfides.

-

•

H2S immediately reacts with cystine to form persulfides and polysulfides in culture medium.

-

•

Cysteine persulfides protect neuronal cells from carbonyl stress through the activation of Nrf2.

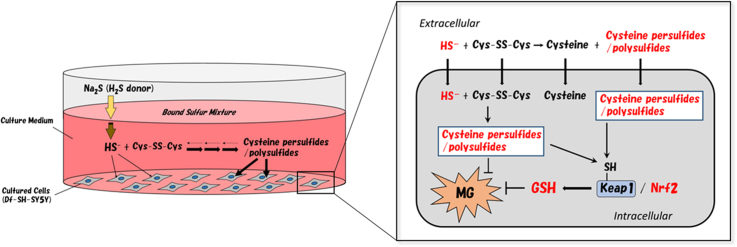

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

H2S is generated from cysteine in mammalian cells [1], [2], [3], [4], and many intensive studies have characterized the physiological functions of H2S [5]. However, it is also known that H2S is stored in cells as “bound sulfur” (including polysulfides and persulfides), which belong to “sulfane sulfur”. In the early 1990s, we redefined specific sulfane sulfur species as “bound sulfur”, which easily converts to hydrogen sulfide on reducing with a thiol reducing agent [6], [7], [8], [9]. In other words, bound sulfur refers to a sulfur atom that exists in zero to divalent form (0 to −2). which is easily liberated as hydrogen sulfide ion (HS−) by reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT). Recent studies have revealed that bound sulfur species (BSS) have various physiological roles in mammalian cells [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. We previously demonstrated that polysulfides, a typical bound sulfur species (BSS), protected neuronal cells from oxidative stress through the activation of the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)/transcription nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) system and also induced neurite outgrowth [9], [12]. Furthermore, polysulfides were found to activate transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) channels and induce Ca2+ influx [10]. We also attempted to detect polysulfides in the brain and showed that H2S3 was generated by a 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3MST)-dependent pathway in neurons [15]. On the basis of these findings, the physiological roles of BSS have garnered increasing attention from many researchers who have studied H2S. Interestingly, the addition of Na2S, an H2S-generating agent with a high level of purity, to in vitro systems have indicated that the effects of BSS potentially caused by the immediate oxidation of H2S in solution cannot be completely eliminated [11], [16]; it is now presumed that part of the action attributed to H2S in these studies may have been due to BSS.

On the other hand, Nrf2 is well established as a critical regulator of intracellular antioxidants and phase II detoxification enzymes by transcriptional up-regulation of many ARE-dependent genes. Nrf2 is targeted for rapid degradation by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, and electrophoretic compounds, heavy metals, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) inhibit Keap1-dependent regulation and activate the translocation of Nrf2 to the nucleus [17]. We most recently revealed that an increase in glutathione (GSH) levels induced by the activation of Nrf2 attenuated methylglyoxal (MG)-induced carbonyl stress in neuronal cells [18].

In the present study, we demonstrated that cysteine persulfides and cysteine polysulfides were generated by the exchange reaction between cystine and HS− in the medium created by the addition of Na2S. Pretreatment with bound sulfur mixture (BS-Mix) clearly exerted an anti-carbonyl stress effect in differentiated human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Moreover, we found that Na2S increased intracellular cysteine persulfide levels in the cystine-free (Cys-free) medium and a slight but significant protective effect against MG-induced toxicity was observed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All-trans retinoic acid (atRA), methylglyoxal 1, and 1-dimethyl acetal (MGDA) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Ham's F-12 (F12) medium was obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Grand Island, NY). A protease inhibitor, phosphatase inhibitor, and DMEM/F12 medium without cystine (Cys-free) were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Na2S·9H2O and formic acid were from Wako (Osaka, Japan). Na2S3, 4-fluoro-7-sulfamoylbenzofurazan (ABD-F), 1,2-diamino-4,5-methylenedioxybenzene, dihydrochloride (DMB), and 3′,6′-di(O-thiosalicyl)fluorescein (SSP4) were obtained from Dojindo (Kumamoto, Japan). Monobromobimane (mBB) was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). RIPA lysis buffer was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA).

2.2. Cell culture

The human neuroblastoma cell line, SH-SY5Y, was obtained from the ATCC. SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in DMEM/ F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 25 U/ml penicillin, 25 µg/ml streptomycin, and 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.4). Cells were cultured and maintained at 37 °C under 5% CO2.

2.3. SH-SY5Y cell differentiation

SH-SY5Y cells were differentiated by a previously described method, with minor modifications [19]. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on a culture dish in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS. The next day, the medium was changed to DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS and 10 μM atRA. Three days after the addition of atRA, the medium was changed to DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS and 10 μM atRA. We confirmed atRA-induced neurite outgrowth and then performed each experiment.

2.4. Purification of MG

Purified MG was synthesized from MGDA. MG was purified according to a previously described method [20].

2.5. Treatment of differentiated (df)-SH-SY5Y cells with Na2S and MG

Df-SH-SY5Y cells were treated with MG and Na2S. Na2S was dissolved to phosphate buffered saline (PBS), which had been degassed with nitrogen gas (10 mM Na2S stock prepared in PBS). Df-SH-SY5Y cells were first seeded onto a culture dish in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS. After differentiation, the medium was changed to DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% or 2% FBS and cells were treated with various concentrations of Na2S or purified MG, which were added at the indicated time points.

2.6. Preparation of pre-treated medium including BS-Mix

Na2S (0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100. and 200 μM) was pre-incubated in DMEM/F12 medium containing cystine and 10% FBS at 37 °C for 2 h under 5% CO2.

2.7. Cell survival assay

Neuronal cell injury was evaluated by a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay [12], [13]. LDH release was measured using the LDH Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (TAKARA BIO INC.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance of the sample was measured at 490 nm with a microplate reader (PerkinElmer EnSpire, USA).

2.8. Measurement of intracellular GSH levels

Intracellular GSH levels were measured by a previously described method, using HPLC with fluorescence detection (HPLC-FL), with minor modifications [21], [22]. Each treated cell sample was lysed by the addition of RIPA lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor. The sample was incubated with 0.2 M borate buffer (pH 10.5) containing 4 mM ABD-F, which specifically reacts with SH residues to form a fluorescent adduct, at 60 °C for 10 min; 0.5 M perchloric acid was then added. After centrifugation at 15,000g for 5 min, the supernatant was used to measure GSH levels with HPLC-FL. Ten microliters of the resulting mixture was injected into a C18 column (Cosmosil, 4.6×250 mm, Nacalai Tesque. Inc., Kyoto. Japan) pre-equilibrated with the mobile phase solution, which consisted of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 3.8): acetonitrile (92:8). A flow rate of 1.0 ml/min was used with a running time of 20 min. Retention times and peak areas were monitored at excitation and emission frequencies of 380 nm and 510 nm, respectively.

2.9. Fluorescence derivatization of H2S, cysteine, persulfides, and polysulfides with mBB

MBB was dissolved to acetonitrile, which had been degassed with nitrogen gas (50 mM mBB stock prepared in acetonitrile). Df-SH-SY5Y cells were harvested, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in lysis buffer (0.1 M phosphate buffer pH7.4, 0.5% Triton-X100, Protease inhibitor cocktail and 2 mM mBB). The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000g at 4 °C, and the supernatant incubated at room temperature for 10 min 5-sulfosalicylic acid was then added at a final concentration of 2%, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 15 min in the dark. The resulting reaction mixture was centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min, and the supernatant was analyzed by HPLC-FL (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.10. Measurement of cysteine and H2S levels

Cysteine and H2S levels were measured by a previously described method, using HPLC-FL with minor modifications [14], [15]. Samples derivatized with mBB were separated with a Waters Symmetry C18 column (250×4.6 mm, Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) with mobile phase A (0.25% formic acid in H2O) and B (0.25% formic acid:methanol =1:1) with a linear gradient program, having the following sequence at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min: 40% B (0 min) – 80% B (8 min) – 80% B (20 min) – 100% B (20.1 min) – 100% (25 min). The mBB adduct was monitored with a scanning fluorescence detector (Shimadzu, RF-20A) with an excitation wavelength of 370 nm and emission wavelength of 485 nm.

2.11. Measurement of persulfides and polysulfides

Cysteine persulfide and cysteine polysulfide levels were measured by a previously described method, using LC-MS/MS, with minor modifications [14]. Samples derivatized with mBB were analyzed using a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled to HPLC (Shimadzu, LCMS-8040). Samples were subjected to a Waters Symmetry C18 column (250×4.6 mm, Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid in water and (B) 0.1% formic acid in methanol. Samples were separated by eluting with a gradient program: 5% B (0 min) – 5% B (5 min) – 90% B (25 min). The column oven was maintained at 40 °C. The effluent was subjected to mass spectrometry using an electrospray ionization (ESI) interface operating in positive-ion mode. The source temperature was set at 400 °C and the ion spray voltage at 4.5 kV. Nitrogen was used as a nebulizer and drying gas. The tandem mass spectrometer was tuned in the multiple reaction monitoring mode to monitor the mass transitions m/z Q1/Q3 344/192 (Cys-SS-mBB), 376/192 (Cys-SSS-mBB), 408/192 (Cys-SSSS-mBB), 241/120 (cystine (Cys-SS-Cys)), 273/122 (Cys-SSS-Cys).

2.12. Measurement of BSS levels

BSS levels were assayed using the fluorescence probe SSP4, according to the manufacturer's instructions. SSP4 is generally used as a selectively bound sulfur probe [23]. DMEM/F12 medium without FBS was added to a 96-well black plate. A total of 1 mM SSP4 was added to each well, and the plate was then incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. The fluorescence of the sample was measured at an excitation wavelength of 482 nm and emission wavelength of 515 nm with a microplate reader (PerkinElmer EnSpire, USA).

2.13. Western blot analysis

Df-SH-SY5Y cells were harvested and washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were then prepared using the NE-PER™ nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (add protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor to CER I and NER) (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts from df-SH-SY5Y cells were boiled for 5 min in SDS sample buffer (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). Proteins were separated by 5–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) and then transferred onto an Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Blocking was performed using 4% (w/v) Block Ace (DS Pharma Biomedical, Osaka, Japan). Next, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies Nrf2 (H-300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), Lamin B1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) or NQO1 (Abnova Co., Taipei City, Taiwan), β-actin (Wako, Osaka, Japan) washed with PBS, and incubated with secondary antibodies HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody or HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The protein bands were detected using Immobilon Western Reagents (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) in a ChemiDoc touch image system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan). Quantification of the results was performed by densitometry using Image Lab Software version 5.2 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan).

2.14. Statistical analysis

Values are presented as the mean±S.D. Differences between two groups were analyzed by a Student's t-test. Differences between three or more groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. (P<0.05 was considered to be a statistically significant difference).

3. Results

3.1. Persulfides and polysulfides are generated in DMEM/F12 medium during the pre-incubation with Na2S

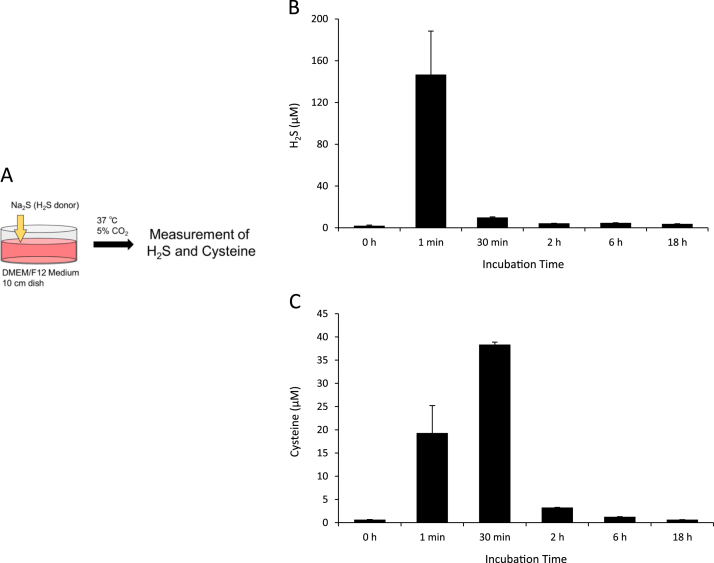

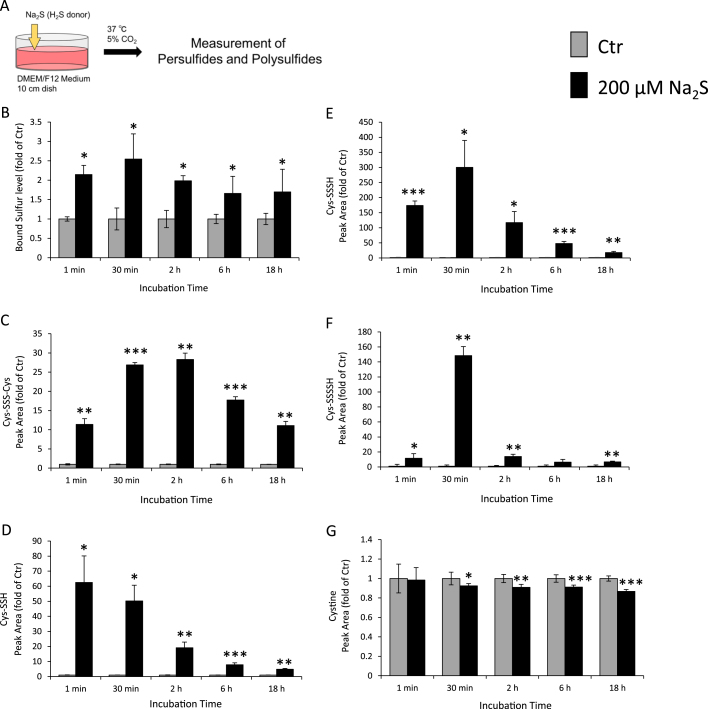

We monitored changes in H2S and cysteine concentrations in the culture medium (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B and C, approximately 150 μM H2S and 20 μM cysteine were detected in the culture medium 1 min after treatment with 200 μM Na2S. Approximately 40 μM cysteine was detected in the culture medium 30 min after treatment with 200 μM Na2S. However, H2S and cysteine concentrations in the culture medium immediately decreased and remained at basal levels for 2–18 h after the treatment of Na2S. We then measured BSS concentrations in culture medium, using SSP4. As shown in Fig. 2B, BSS concentrations in the culture medium were significantly higher 1 min–18 h after the treatment with Na2S than that with the control. We also examined the formation of cysteine persulfides and cysteine polysulfides in culture medium after the addition of Na2S by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 2A). The results indicated that cysteine persulfides (Cys-SS−, Cys-SSS−, and Cys-SSSS−) and cysteine polysulfides (Cys-SSS-Cys) were present in DMEM/F12 medium [FBS(+), Cys(+)] 1 min to 18h after the treatment with 200 μM Na2S and after 30 min displayed a time-dependent decrease in their levels (Fig. 2C–F). By contrast, the level of endogenous cystine decreased after 200 μM Na2S treatment for 30 min–18 h compared with that in the control (Fig. 2G). These results clearly indicated that the addition of Na2S to DMEM/F12 medium generated BSS such as cysteine persulfides and polysulfides.

Fig. 1.

H2S and cysteine concentrations in culture medium. DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS was treated with or without 200 μM Na2S for the indicated time. (A) Protocol for the addition of Na2S in the medium. (B and C) H2S and cysteine in the medium were derivatized with mBB and (B) H2S and (C) cysteine concentrations measured using HPLC-FL. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values indicate means±S.D.

Fig. 2.

Measurement of BSS levels in culture medium. DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS was treated with or without 200 μM Na2S for the indicated time. (A) Protocol for the addition of Na2S in the medium. Medium was derivatized with (B) SSP4 to measure BSS levels, using a microplate reader or (C-G) mBB for (C) Cys-SSS-Cys, (D) Cys-SSH, (E) Cys-SSSH, (F) Cys-SSSSH or (G) cystine using LC-MS/MS. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values indicate means±S.D. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 significantly different from the Ctr (PBS) level.

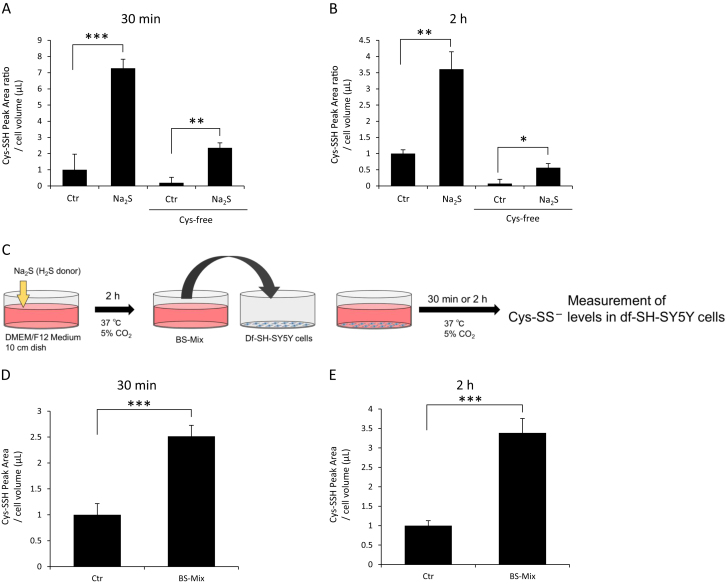

3.2. Na2S increases intracellular cysteine persulfide levels

In this study, we indicated that Na2S generates cysteine persulfides and cysteine polysulfides in culture medium. Next, we measured endogenous cysteine persulfide levels in df-SH-SY5Y cells when treated with Na2S in the presence or absence of extracellular cystine, as shown in Fig. 3A and B. Na2S increased endogenous cysteine persulfide (Cys-SS−) levels at 30 min and 2 h after its treatment. Moreover, even in the absence of extracellular cystine, Na2S increased endogenous cysteine persulfide levels at 30 min and 2 h after treatment with Na2S (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 3.

Measurement of Cys-SS− levels in df-SH-SY5Y cells. (A and B) Cells were treated with or without 200 μM Na2S for (A) 30 min or (B) 2 h in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS with or without cystine. (C) Protocol of the preparation and treatment of a medium containing BS-Mix (prepared by 200 μM Na2S). (D and E) Cells were treated with or without BS-Mix for (D) 30 min or (E) 2 h in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS and cystine. Cell lysates were derivatized with mBB to measure Cys-SS− levels using LC-MS/MS. Values indicate means±S.D. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 significantly different from the Ctr (PBS) level. N.S.; not significant. All data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Next, we investigated the effect of BS-Mix on endogenous cysteine and cysteine persulfide levels in df-SH-SY5Y cells. As shown in Fig. 3D and E, treatment with BS-Mix significantly increased endogenous cysteine persulfide (Cys-SS−) levels at 30 min and 2 h in df-SH-SY5Y cells.

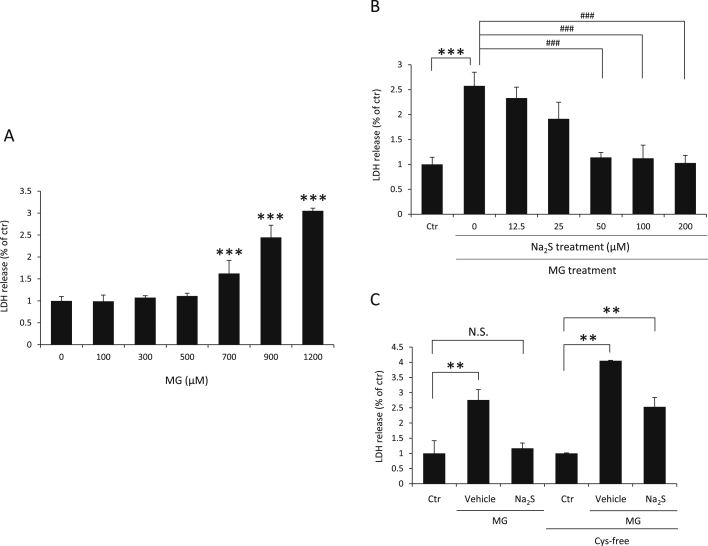

3.3. Protective effects of H2S against MG-induced cytotoxicity

We investigated whether H2S protects df-SH-SY5Y cells against MG-induced cytotoxicity. Cell viability was assessed by the LDH assay. As shown in Fig. 4A, df-SH-SY5Y cells were damaged by treatment with MG for 24 h. When df-SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with 200 µM Na2S for 2 h, followed by 900 μM MG treatment for 24 h, a significant decrease was observed in MG-induced LDH release (Fig. 4B). However, in Cys-free medium, the protective effect of Na2S against MG-induced cytotoxicity was attenuated compared with that upon treatment with Na2S in the medium containing cystine (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that H2S protected df-SH-SY5Y cells against MG-induced cytotoxicity caused by Na2S as a donor of persulfide, and extracellular cystine is the key factor in this protective effect.

Fig. 4.

Protective effects of Na2S against MG-induced cytotoxicity in df-SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Cell viability was measured by a LDH assay. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of MG for 24 h. ***P<0.001 compared to the value obtained following treatment with 0 μM MG. (B) Cells were pretreated with or without the indicated concentrations of Na2S for 2 h in DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS, and culture medium was exchanged to remove Na2S; cells were then treated with 900 µM MG for 24 h in DMEM/F12 containing 2% FBS. ***P<0.001 significantly different from the control (Ctr) level. ###P<0.001 significantly different from 0 μM Na2S (C) Cells were pretreated with 200 μM Na2S or vehicle (PBS) for 2 h in DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS, and culture medium exchanged to remove Na2S. Cells were then treated with 900 µM MG for 24 h in DMEM/F12 containing 2% FBS with or without cystine. Cell viability was assessed by the LDH assay. **P<0.01 significantly different from the control (Ctr) level. Values indicate means±S.D. All data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

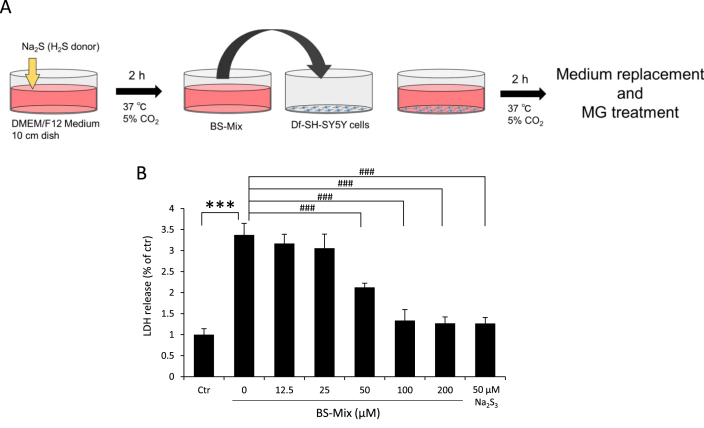

3.4. BS-Mix protects df-SH-SY5Y cells against MG-induced toxicity

We investigated whether BS-Mix without H2S protects cells against MG-induced cytotoxicity. Df-SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with BS-Mix for 2 h, followed by MG treatment for 24 h (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, treatment with a pre-incubated medium containing BS-Mix significantly protected df-SH-SY5Y cells from MG-induced cytotoxicity in a Na2S dose-dependent manner. These results indicated that BS-Mix containing cysteine persulfides and cysteine polysulfides protected df-SH-SY5Y cells against MG-induced cytotoxicity, similar to the polysulfide (Na2S3) treatment. Meanwhile, Cys-free medium with or without 10% FBS treated with 200 μM Na2S did not protect the cells from MG-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. S1).

Fig. 5.

Protective effects of BS-Mix without free H2S against MG-induced cytotoxicity in df-SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Protocol of the preparation and treatment of a medium containing BS-Mix before the treatment of MG in df-SH-SY5Y cells. Cells were pretreated with or without the indicated concentrations of BS-Mix or 50 μM Na2S3 for 2 h, and the culture medium exchanged to remove BS-Mix. Cells were then treated with 900 µM MG for 24 h in DMEM/F12 containing 2% FBS. Values indicate means±S.D. ***P<0.001 significantly different from the Ctr level. ###P<0.001 significantly different from 0 μM Na2S. All data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

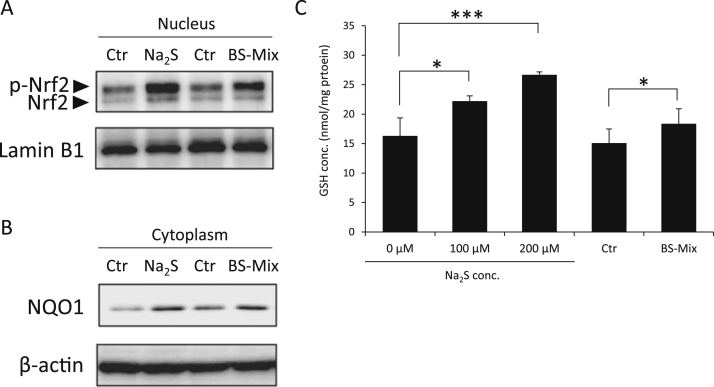

3.5. Na2S and BS-Mix induce translocation of Nrf2 into the nucleus

Our previous report indicated that MG-induced cytotoxicity is attenuated by the activation of Nrf2 and increasing GSH levels [18]. Therefore, the activation of Nrf2 is important for the protective mechanism of MG-induced cytotoxicity. First, we observed whether Na2S or BS-Mix induces translocation of Nrf2 to the nucleus in df-SH-SY5Y cells by western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 6A, 200 µM Na2S and BS-Mix significantly increased Nrf2 localization in nuclear fractions compared with that seen in the untreated control 2 h after their treatment in df-SH-SY5Y cells. Additionally, treatment with Na2S or BS-Mix increased the expression of NQO1, a typical Nrf2-regulatory and ARE-target protein in the cytosolic fractions, as shown in Fig. 6B. Further, we measured GSH levels in df-SH-SY5Y cells after Na2S or BS-Mix treatment. After 100 µM and 200 µM Na2S or BS-Mix were added and cultured for 2 h, GSH levels were significantly increased in df-SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Accumulation of Nrf2 in the nuclear fraction in df-SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Cells were treated with or without 200 μM Na2S in DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS medium or BS-Mix (prepared by 200 μM Na2S) for 2 h, and Nrf2 protein levels in nuclear fractions were analyzed by western blotting. Lamin B1 was used as nuclear loading control (bottom panel). (B) Cells were treated with or without 200 μM Na2S in DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS medium or BS-Mix (prepared by 200 μM Na2S) for 10 h, and NQO1 protein levels in cytosol fractions were analyzed by western blotting. β-actin was used as cytosol loading control (bottom panel). (C) Cells were treated with 0, 100 and 200 μM Na2S or BS-Mix (prepared by 200 μM Na2S) for 2 h, and GSH levels were measured using HPLC-FL with ABD-F derivatized samples. Values indicate means±S.D. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001. All data are representative of at least three independent experiments. p-Nrf2, phosphorylated Nrf2.

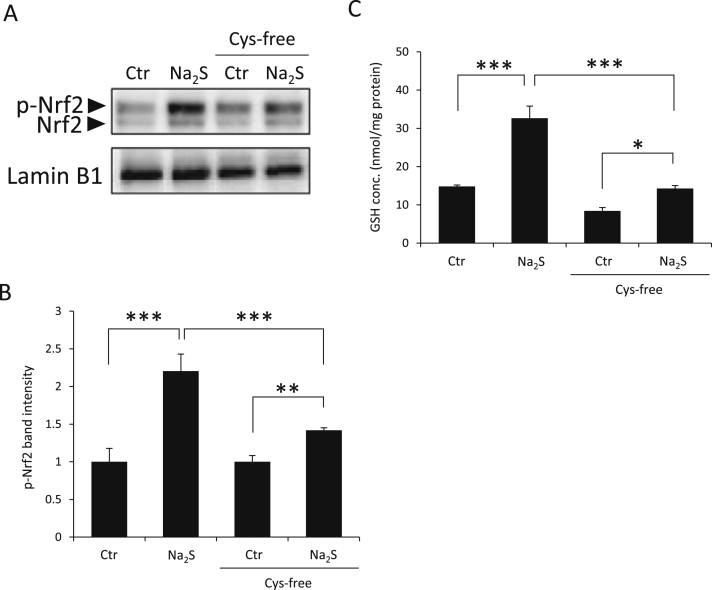

3.6. Na2S activates Nrf2 in df-SH-SY5Y cells in Cys-free medium

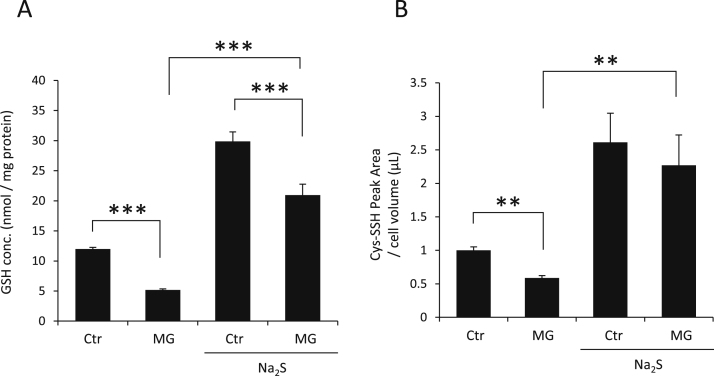

To investigate whether the Na2S-induced activation of Nrf2 is affected by extracellular cystine levels, Na2S was added to cells in the presence or absence of extracellular cystine. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, in the absence of extracellular cystine, Na2S slightly but significantly increased Nrf2 protein levels in nuclear fractions compared with that seen in the untreated control. Intranuclear Nrf2 protein accumulated during treatment with Na2S in Cys-free medium was lower than that seen in cystine-containing medium. Additionally, we measured GSH levels in df-SH-SY5Y cells treated with Na2S and BS-Mix in the presence or absence of extracellular cystine. As shown in Fig. 7C, although treatment with 200 µM Na2S for 2 h increased GSH levels compared with that in the untreated control, regardless of the presence or absence of cystine, the magnitude of change was significantly higher in the presence of extracellular cystine than without it. These results showed that H2S-induced Nrf2 activation is dependent on extracellular cystine.

Fig. 7.

Accumulation of Nrf2 in the nuclear fraction from df-SH-SY5Y cells. (A–C) Cells were treated with 200 μM Na2S in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% FBS and cystine or without FBS and cystine; Nrf2 protein levels in nuclear fractions were analyzed by western blotting (A and B) and GSH levels were measured by HPLC-FL with ABD-F derivatized samples (C). Lamin B1 was used as the nuclear loading control (bottom panel of A). (B) The densities of p-Nrf2 bands were measured and the ratio to LaminB1 calculated and expressed as fold-change of the band levels relative to control (Ctr) samples. Values indicate means±S.D. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. All data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Cys-free, cystine-free; p-Nrf2, phosphorylated Nrf2.

3.7. MG decreases intracellular GSH and cysteine persulfide levels

Since MG and GSH react with each other and generate hemithioacetal, which is metabolized by GLO1/GLO2 system, excess MG depletes the GSH. As shown in Fig. 8A and B, treatment with 900 μM MG seems to decrease not only GSH but also cysteine persulfide (Cys-SS−) levels after 1 h. However, when pretreated with 200 μM Na2S for 2 h, GSH and cysteine persulfide levels increased, even 1 h after MG treatment.

Fig. 8.

Influence of MG on endogenous GSH and Cys-SS− levels in df-SH-SY5Y cells. (A and B) Cells were pretreated with or without 200 μM Na2S for 2 h in DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS, and culture medium exchanged to remove Na2S. Cells were then treated with 900 µM MG for 1 h in DMEM/F12 containing 2% FBS. Cell lysates were derivatized with ABD-F to measure GSH by HPLC-FL (A) or mBB to measure Cys-SS− (B) levels by LC-MS/MS. Values indicate means±S.D. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. All data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

4. Discussion

A previous study clearly indicated that the reactions of cystine with HS− was found to be slow compared to that of thiolates [24]. However, HS− can react with cystine [25] and protein-SS-Cys [26] to generate cysteine persulfide at pH7.4. Recent report indicated at pH7.4, the availability of HS− is higher because the ratio HS−/H2S is 2.51 at pH7.4 due to the low pKa of H2S, and the ratio thiolate/thiol for cysteine is 0.13 [27].

In this study, the addition of high-purity Na2S to a tissue culture medium (DMEM/F12) containing cystine resulted in the transient formation of HS− followed by the generation of cysteine and cysteine persulfide (Cys-SS−). Further reactions produced cysteine polysulfide (Cys-SS(n)S-Cys), resulting in a bound sulfur mixture (BS-Mix) containing Cys-SS(n)− and Cys-SS(n)S-Cys. The reactions, as shown in (1) and (2) below, proceeded rapidly in a neutral medium.

| HS−+Cys-SS-Cys→Cys-SS−+Cysteine | (1) |

| Cys-SS−+Cys-SS-Cys→Cys-SSS-Cys+Cysteine | (2) |

Furthermore, when HS− was added to a Cys-free medium, the exchange reaction did not occur and the production of Cys-SS− and Cys-SSS-Cys was not observed. However, Cys-SS− was observed intracellularly, with no change in intracellular HS− concentration. This suggested that the incorporated HS− reacted with intracellular cystine to form Cys-SS−. Higher intracellular Cys-SS− concentrations were observed when HS− was added to a standard culture medium containing cystine, or when an HS−-free BS-Mix was used. These data suggest that Cys-SS− is formed in the medium before its uptake into the cells, or Cys-SS− is formed after HS− is taken into the cells.

A large number of studies have implicated carbonyl stress in Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia, and diabetes mellitus [28], [29], [30]. The accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) formed in the Maillard reaction in cells is referred to as carbonyl stress. For example, metabolic abnormalities in reactive carbonyl compounds, such as MG, lead to accumulation of AGEs and carbonyl stress in neuronal cells [31]. Chang et al. reported that H2S donor, NaHS, decreased cellular MG levels in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells [32]. We recently anticipated the possibility that polysulfide, not H2S, has scavenging ability against methylglyoxal [13]. Our results also indicated that polysulfide promotes GSH synthesis, and the subsequent increase in GSH concentration partially contributes to alleviating MG toxicity. Thus, it seems that polysulfide acts through a GSH-dependent mechanism and direct scavenging reactivity to weaken glycation stress.

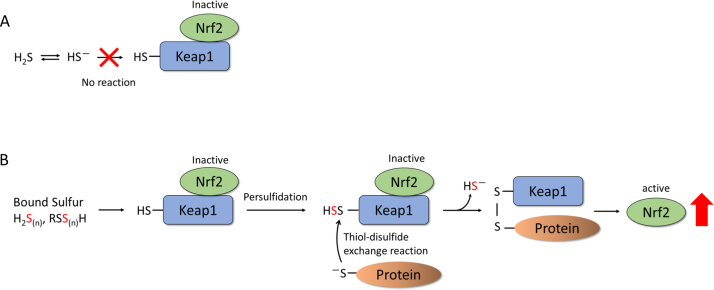

In this study, pretreatment of differentiated (df)-SH-SY5Y cells with Na2S attenuated toxicity caused by methylglyoxal. Additionally, a significant protective effect was observed in the medium in which all added HS− was converted to BS-Mix. We recently suggested that Nrf2 activation deeply contributed to the attenuation of MG-induced neurotoxicity [18]. Some researchers indicated that H2S/HS− directly react with the Keap1 cysteine residues and induce Nrf2 activation [33], [34]. However, HS− is not able to react with protein cysteine residues directly (Fig. 9A) [35]. In contrast, we recently revealed that BSS easily react with keap1 cysteine thiol residues and induce Nrf2 activation (Fig. 9B) [12]. In the present study, Na2S and BS-Mix treatment significantly induced Nrf2 nuclear translocation in df-SH-SY5Y cells. Therefore, this protective effect was due to the activation of the Nrf2 pathway by the BSS, which are produced by HS− as a precursor. We postulate that this HS−-induced Nrf2 activation may be caused by a mechanism similar to that observed during the persulfidation of Keap1, which introduces a steric change, thereby suppressing the Keap1/Nrf2 degradation system. Based on the above results, the protective effect of Na2S (HS−) observed in df-SH-SY5Y cells was not based on HS− itself as the active form, but rather was mediated by Cys-SS− and Cys-SSS-Cys.

Fig. 9.

Proposed mechanism for the activation of Nrf2 mediated by BSS. (A) HS− does not react with Keap1 cysteine residues and Nrf2 remains inactive. (B) BSS (hydrogen polysulfides, cysteine persulfides and polysulfides) react with Keap1 cysteine residues and induce the activation of Nrf2.

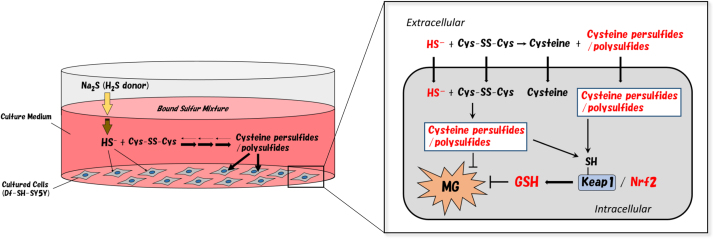

Hence, we can conclude that in the many cases that reported the use of a cystine-containing medium with Na2S and NaHS acting as HS− donors, the reactive species that affected the cultured cells was probably a BSS such as Cys-SS−, Cys-SSS-Cys, or similar (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

The exchange reactions between HS− and cystine to form persulfides and polysulfides in the cultured medium and differentiated-SH-SY5Y cells.

Conflicts of interest

The authors claim no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support from DOJINDO Laboratories, who provided Na2S3 and SSP4 for use in this study. Part of this work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP16K08383.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.020.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material Figure S1. Cys-free medium treated with Na2S did not protect the cells from MG-toxicity. A total of 200 µM Na2S was added to DMEM/F12 medium with or without cystine and 10% FBS at 37 °C for 2 h under 5% CO2 [A: (BS-Mix): Cys(+), FBS(+) and 200 μM Na2S(+), B: Cys-free, FBS(+) and 200 μM Na2S(+), C: Cys-free, FBS(-) and 200 μM Na2S(+)]. Cells were pretreated with A, B, or C medium for 2 h, and culture medium was exchanged to remove the medium; cells were then treated with 900 µM MG for 24 h. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values indicate means±S.D. ***P<0.001 significantly different from 0 μM BS-Mix. N.S.; not significant. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. Cys: cysteine.

.

References

- 1.Hosoki R., Matsuki N., Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;237(3):527–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stipanuk M.H., Beck P.W. Characterization of the enzymic capacity for cysteine desulphhydration in liver and kidney of the rat. Biochem. J. 1982;206(2):267–277. doi: 10.1042/bj2060267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shibuya N., Tanaka M., Yoshida M., Ogasawara Y., Togawa T., Ishii K., Kimura H. 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11(4):703–714. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shibuya N., Koike S., Tanaka M., Ishigami-yuasa M., Kimura Y., Ogasawara Y., Fukui K., Nagahara N., Kimura H. A novel pathway for the production of hydrogen sulfide from D-cysteine in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1366–1367. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose P., Moore P.K., Zhu Y.Z. H2S biosynthesis and catabolism: new insights from molecular studies. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2406-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogasawara Y., Ishii K., Togawa T., Tanabe S. Determination of bound sulfur in serum by gas dialysis/high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1993;215(1):73–81. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishigami M., Hiraki K., Umemura K., Ogasawara Y., Ishii K., Kimura H. A source of hydrogen sulfide and a mechanism of its release in the brain. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11(2):205–214. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koike S., Ogasawara Y. Sulfur atom in its bound state is a unique element involved in physiological functions in mammals. Molecules. 2016;21(12):1753. doi: 10.3390/molecules21121753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koike S., Shibuya N., Kimura H., Ishii K., Ogasawara Y. Polysulfide promotes neuroblastoma cell differentiation by accelerating calcium in flux. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;459(3):488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura Y., Mikami Y., Osumi K., Tsugane M., Oka J.I., Kimura H. Polysulfides are possible H2S-derived signaling molecules in rat brain. FASEB J. 2013;27(6):2451–2457. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-226415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greiner R., Pálinkás Z., Bäsell K., Becher D., Antelmann H., Nagy P., Dick T.P. Polysulfides link H2S to protein thiol oxidation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;19(15):1749–1765. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koike S., Ogasawara Y., Shibuya N., Kimura H., Ishii K. Polysulfide exerts a protective effect against cytotoxicity caused by t-buthylhydroperoxide through Nrf2 signaling in neuroblastoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(21):3548–3555. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koike S., Kayama T., Yamamoto S., Komine D., Tanaka R., Nishimoto S., Kishida A., Suzuki T., Ogasawara Y. Polysulfides protect SH-SY5Y cells from methylglyoxal-induced toxicity by suppressing protein carbonylation: a possible physiological scavenger for carbonyl stress in the brain. Neurotoxicology. 2016;55:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ida T., Sawa T., Ihara H., Tsuchiya Y., Watanabe Y., Kumagai Y., Suematsu M., Motohashi H., Fujii S., Matsunaga T., Yamamoto M., Ono K., Devarie-Baez N.O., Xian M., Fukuto J.M., Akaike T. Reactive cysteine persulfides and S-polythiolation regulate oxidative stress and redox signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111(21):7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321232111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura Y., Toyofuku Y., Koike S., Shibuya N., Nagahara N., Lefer D., Ogasawara Y., Kimura H. Identification of H2S3 and H2S produced by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the brain. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14774. doi: 10.1038/srep14774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes M.N., Centelles M.N., Moore K.P. Making and working with hydrogen sulfide the chemistry and generation of hydrogen sulfide in vitro and its measurement in vivo: a review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47(10):1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki T., Yamamoto M. Molecular basis of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;88(Pt B):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimoto S., Koike S., Inoue N., Suzuki T., Ogasawara Y. Activation of Nrf2 attenuates carbonyl stress induced by methylglyoxal in human neuroblastoma cells: increase in GSH levels is a critical event for the detoxification mechanism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;483(2):874–879. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang R.C.-C., Suen K.-C., Ma C.-H., Elyaman W., Ng H.-K., Hugon J. Involvement of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2alpha in neuronal degeneration. J. Neurochem. 2002;83(5):1215–1225. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabbani N., Thornalley P.J. Measurement of methylglyoxal by stable isotopic dilution analysis LC-MS/MS with corroborative prediction in physiological samples. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9(8):1969–1979. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogasawara Y., Mukai Y., Togawa T., Suzuki T., Tanabe S., Ishii K. Determination of plasma thiol bound to albumin using affinity chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection: ratio of cysteinyl albumin as a possible biomarker of oxidative stress. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2007;845(1):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogasawara Y., Takeda Y., Takayama H., Nishimoto S., Ichikawa K., Ueki M., Suzuki T., Ishii K. Significance of the rapid increase in GSH levels in the protective response to cadmium exposure through phosphorylated Nrf2 signaling in Jurkat T-cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;69:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deleon E.R., Gao Y., Huang E., Olson K.R. Garlic oil polysulfides: H2S− and O2− independent prooxidants in buffer and antioxidants in cells. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016;310(11):1212–1225. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00061.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasas A., Dóka É., Fábián I., Nagy P. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies on the disulfide-bond reducing potential of hydrogen sulfide. Nitric Oxide. 2015;46(30):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao G.S., Gorin G. Reaction of cysteine with sodium sulfide in sodium hydroxide solution. J. Org. Chem. 1959;24:749–753. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francoleon N.E., Carrington S.J., Fukuto J.M. The reaction of H(2)S with oxidized thiols: generation of persulfides and implications to H(2)S biology. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;516(2):146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuevasanta E., Lange M., Bonanata J., Coitiño E.L., Ferrer-Sueta G., Filipovic M.R., Alvarez B. Reaction of hydrogen sulfide with disulfide and sulfenic acid to form the strongly nucleophilic persulfide. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290(45):26866–26880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.672816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki N., Fukatsu R., Tsuzuki K., Koike T., Wakayama I., Yanagihara R., Garruto R. Advanced glycation end products in Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;153(4):1149–1155. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65659-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalousová M., Škrha J., Zima T. Advanced glycation end-products and advanced oxidation protein products in patients with diabetes mellitus. Physiol. Res. 2002;51(6):597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arai M., Yuzawa H., Nohara I., Ohnishi T., Obata N., Iwayama Y. Enhanced carbonyl stress in a subpopulation of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):589–597. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allaman I., Bélanger M., Magistretti P.J. Methylglyoxal, the dark side of glycolysis. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:23. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang T., Untereiner A., Liu J., Wu L. Interaction of methylglyoxal and hydrogen sulfide in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;12(9):1093–1100. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang G., Zhao K., Ju Y., Mani S., Cao Q., Puukila S., Khaper N., Wu L., Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide protects against cellular senescence via S-sulfhydration of Keap1 and activation of Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;18(15):1906–1919. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hourihan J.M., Kenna J.G., Hayes J.D. The gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide induces nrf2-target genes by inactivating the keap1 ubiquitin ligase substrate adaptor through formation of a disulfide bond between cys-226 and cys-613. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;19(5):465–481. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toohey J.I. Sulfur signaling: is the agent sulfide or sulfane? Anal. Biochem. 2011;413(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material Figure S1. Cys-free medium treated with Na2S did not protect the cells from MG-toxicity. A total of 200 µM Na2S was added to DMEM/F12 medium with or without cystine and 10% FBS at 37 °C for 2 h under 5% CO2 [A: (BS-Mix): Cys(+), FBS(+) and 200 μM Na2S(+), B: Cys-free, FBS(+) and 200 μM Na2S(+), C: Cys-free, FBS(-) and 200 μM Na2S(+)]. Cells were pretreated with A, B, or C medium for 2 h, and culture medium was exchanged to remove the medium; cells were then treated with 900 µM MG for 24 h. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values indicate means±S.D. ***P<0.001 significantly different from 0 μM BS-Mix. N.S.; not significant. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. Cys: cysteine.