Abstract

This study aimed at investigating the genetic diversity of a panel of Candida africana strains recovered from vaginal samples in different countries. All fungal strains were heterozygous at the mating-type-like locus and belonged to the genotype A of Candida albicans. Moreover, all examined C. africana strains lack N-acetylglucosamine assimilation and sequence analysis of the HXK1 gene showed a distinctive polymorphism that impair the utilization of this amino sugar in this yeast. Multi-locus sequencing of seven housekeeping genes revealed a substantial genetic homogeneity among the strains, except for the CaMPIb, SYA1 and VPS13 loci which contributed significantly to the classification of our set of C. africana strains into six existing diploid sequence types. Amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprint analysis yielded greater genotypic heterogeneity among the C. africana strains. Overall the data reported here show that in C. africana genetic diversity occurs and the existence of this intriguing group of C. albicans strains with specific phenotypes associated could be useful for future comparative studies in order to better understand the genetics and evolution of this important human pathogen.

Keywords: Candida africana, Candida albicans, genotyping, multi-locus sequence typing, amplified fragment length polymorphisms

Introduction

One of the great challenges in the past 20 years of mycological research has been to understand the genetic diversity and evolution of pathogenic fungi. This had important implications in the clinical settings because a great deal has been learned about the underlying mechanisms of virulence, pathogenicity, and drug resistance of important human fungal pathogens.

In parallel, a considerably increased frequency of fungal infections has been constantly reported worldwide and directly associated to the growing numbers of immunocompromised patients (Tuite and Lacey, 2013; Vallabhaneni et al., 2016). Among the different fungal species infecting humans, those belonging to the Candida clade remain the most common cause of opportunistic mycoses and Candida albicans is undoubtedly the most frequently encountered clinically important species (Pfaller et al., 2012; Quindós, 2014). Its success as a pathogen is, in part, attributable to the ability to adapt to a wide range of environments; to express a number of virulence determinants and to develop quickly resistance to commonly used antifungal drugs (Forche et al., 2008; Hirakawa et al., 2015; Scaduto and Bennett, 2015).

Such rapid, dynamic development of new phenotypic traits is often due to long-range genetic changes, such as numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities, subtelomeric hypervariation, and loss of heterozygosity (LOH), that affect large genomic regions and shape the evolution of new strains (Bennett et al., 2014; Hirakawa et al., 2015). In fact, molecular studies based on multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) revealed an unexpected diversity among different clades as well as clade-specific drug resistance and geographical specificity for particular genetically related groups of strains (Odds et al., 2007; MacCallum et al., 2009; McManus and Coleman, 2014).

Until October 2016, the C. albicans MLST database1 contained 1375 sequences from 4215 isolates arranged in 3178 diploid sequence types (DSTs). Of these, certainly, one of the most intriguing type is the DST182 which includes 24 yeast isolates originally described as Candida africana (Tietz et al., 2001; Romeo et al., 2013).

Candida africana was isolated, for the first time, in 1993 in Madagascar and Angola, Africa (Tietz et al., 1995) and afterward proposed as new Candida species phylogenetically closely related to the well-known human pathogen C. albicans (Tietz et al., 2001). However, currently C. africana is known as a biovariant of C. albicans with an exceptional capacity to colonize human genitalia and cause mainly vaginal infections (Romeo and Criseo, 2011; Romeo et al., 2013). Its distribution appears to be worldwide, with cases of infection reported from China (Shan et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2015), Japan (Odds et al., 2007), South Korea (Song et al., 2014), Colombia (Rodríguez-Leguizamón et al., 2015), Argentina (Theill et al., 2016), Chile (Odds et al., 2007), India (Sharma et al., 2014), Iran (Yazdanparast et al., 2015), Africa (Tietz et al., 2001; Dieng et al., 2012; Nnadi et al., 2012; Ngouana et al., 2015), USA (Romeo et al., 2013), and Europe (Alonso-Vargas et al., 2008; Romeo and Criseo, 2009; Borman et al., 2013). However, despite the efforts made so far, it is rather difficult to discriminate C. africana from C. albicans in clinical diagnostic laboratories and therefore its epidemiology is still unclear and needs more investigation (Romeo et al., 2013). Nevertheless, overall prevalence of C. africana in European vaginal samples can be estimated around 6–16% (Romeo and Criseo, 2009; Borman et al., 2013) while in Africa, it appears to be much more variable ranging from ∼2% in Senegal and Nigeria to 23% in Angola and 40% in Madagascar (Romeo et al., 2013).

Similarly to C. albicans, the clinical signs of vaginal infections caused by C. africana are characterized by white discharges, inflammation of the vaginal walls and vulvar tissues, accompanied by local itching or burning (Romeo et al., 2013).

Phenotypically, C. africana shows remarkable differences when compared to C. albicans such as the inability to produce the characteristic chlamydospores and the incapacity to assimilate many carbon sources especially N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc; Tietz et al., 2001). This amino sugar is metabolized by all typical C. albicans strains investigated (Tietz et al., 1995) and it is essential for various cellular processes in this species including white-opaque switching and yeast-to-hyphal transition (Huang et al., 2010; Konopka, 2012). In addition, C. africana also shows poor adhesion to human epithelial cells (Romeo et al., 2011), a notable low level of filamentation (Borman et al., 2013) and decreased virulence as recently demonstrated using both mammalian and insect infection models (Borman et al., 2013; Pagniez et al., 2015). All these characteristics could be the reflection of a peculiar genetic background that is worth to be investigated in detail. For these reasons, we decided to genotype a panel of C. africana isolates from different geographical areas in order to evaluate their genetic relationships and diversity.

Materials and Methods

Fungal Strains

Twenty six C. africana strains from different geographical origin were examined in this study (Figure 1). All strains were isolated from vaginal specimens and were phenotypically characterized in previous studies (Alonso-Vargas et al., 2008; Romeo and Criseo, 2009; Shan et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2014; Yazdanparast et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the lack of chlamydospore production on corn meal agar (CMA) at 24°C for 7 days and the absence of GlcNAc assimilation after 28 days of incubation at 30°C (Felice et al., 2016) were initially used as standard phenotypic criteria to verify the varietal status of the strains. Subsequently, their identity was confirmed by partial amplification of the HWP1 gene according to Romeo and Criseo (2008).

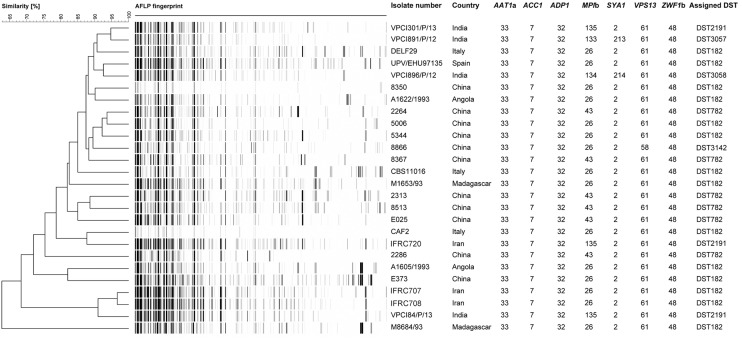

FIGURE 1.

UPGMA dendrogram based on AFLP fingerprints obtained from 26 C. africana strains. The columns after the AFLP patterns shows the isolate number, country of origin, the seven loci used in the MLST analysis, and DSTs assigned by C. albicans MLST database.

Candida albicans (ATCC 90028 = CBS 8837), Candida dubliniensis (CD 36 = CBS 7987), Candida stellatoidea (CBS 1905) and C. africana (CBS 8781) were used as reference strains.

ABC Genotyping and Mating Status Determination

The ABC genotype was determined using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay described by McCullough et al. (1999). This method detects the presence or absence of a transposable group I intron in DNA sequences encoding 25S rRNA and can classify C. albicans strains into three different genotypes according to the number and the size of the amplicon produced by PCR: genotype A (∼450 bp), genotype B (∼840 bp), and genotype C (∼450 and ∼840 bp) (McCullough et al., 1999).

For mating-type determination, three previously designed primer pairs were used to amplify specific regions within the MTLα1, MTLa1, and MTLa2 loci (Hull and Johnson, 1999).

In vitro amplifications for both ABC and mating-type analysis were carried out using Dream Taq Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Milan, Italy), a ready-to-use solution containing all reagents required for PCR to which were only added the DNA template (20 ng) and the specific primers, depending on the assay type (Hull and Johnson, 1999; McCullough et al., 1999). The amplicons were analyzed by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis for ABC-typing and 1.5% agarose for mating-type determination.

Partial Amplification and Sequencing of the HXK1 Gene

DNA sequence analysis of the HXK1 gene, encoding the enzyme GlcNAc-kinase, was done to demonstrate the existence of a specific mutation (guanine insertion) that impairs GlcNAc assimilation in C. africana (Felice et al., 2016).

The DNA region of the HXK1 gene carrying the polymorphism was amplified using the primer pair HXK1tr-fw 5′-GACTAGCATTAGTGGGTTGCG-3′ and HXK1-Rb 5′-CACCCAGCAGAATACACCG-3′ as described by Felice et al. (2016). The obtained HXK1-fragment (∼687 bp) was purified with a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy) and bi-directionally sequenced using the same PCR primers for which the Big Dye Terminator Kit v3.1 (Applied Biosystems) was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations on an automatic sequencer ABI 3130XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Electropherograms were inspected using FinchTV v1.4 software2 and compared with the corresponding wild-type open reading frame (ORF) sequence of C. albicans (GenBank: KP193959) and C. africana (GenBank: KP193956) reference strains, respectively.

Multi-Locus Sequence Typing Analysis of C. africana

The MLST scheme used for C. africana typing was based on a previously published consensus set of seven housekeeping genes for C. albicans: CaAAT1a, CaACC1, CaADP1, CaMPIb, CaSYA1, CaVPS13, and CaZWF1b (Bougnoux et al., 2003).

The reaction mixture, primers and conditions used for PCR-amplifications were the same as those previously described by Sharma et al. (2014). Amplicon purification and sequencing was performed as described above.

Sequencing electropherograms were manually inspected with FinchTV v1.4 software to detect call errors and to determine the positions of heterozygous polymorphisms. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were confirmed visually by examination of both forward and reverse sequence traces (Tavanti et al., 2003). The one-letter International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nucleotide code was used in sequence analyses. The sequence data of our isolates at each locus were compared with sequences deposited into the public MLST database (see text footnote 1) for assigning the allele numbers (Tavanti et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2014). The DST for an individual isolate was defined by the composite profile of all seven allele numbers.

Phylogenetic analysis, using our MLST data and selected DSTs representing the five most populous C. albicans clades (clades 1, 2, 3, 4, and 11) were conducted with Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) v6 software (Tamura et al., 2013). Before the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) clustering, using the p-distance model, the editing process described by Odds et al. (2007) for the analysis of diploid sequence data was employed to label homozygous and heterozygous polymorphic sites.

Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism Fingerprinting

To further assess the genotypic diversity, C. africana strains were subjected to amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) fingerprinting as previously described (Chowdhary et al., 2014). Raw data were analyzed with BioNumerics v7.5 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) using the UPGMA algorithm for cluster analysis. An arbitrary cut-off value of 95% similarity was used for defining a distinct genotype among the AFLP patterns.

Results

All C. africana strains examined in this study were unable to produce chlamydospores on CMA and did not grow in tubes containing different concentrations (100–0.195 mM) of GlcNAc as the sole carbon source. Molecular identification of these strains, based on partial amplification of the HWP1 gene, confirmed the presence of the expected 700 bp DNA fragment specific for C. africana.

A reasonable explanation for the inability of all our C. africana strains to grow in medium containing GlcNAc as the only carbohydrate source was provided by HXK1 gene analysis, which revealed the presence of a homozygous single guanine insertion in the gene ORF. This mutation was identical to that previously described in C. africana (GenBank: KP193956-KP193958) and results in a frame shift mutation that introduces a premature termination codon (TGA) in the HXK1 coding sequence, generating a putative non-functional truncated protein product (Felice et al., 2016). In addition to this specific polymorphism, all C. africana were found to belong to the genotype A of C. albicans and were all heterozygous (a/α) at the mating-type-like (MTL) locus. Overall these results indicate that C. africana strains exhibit a distinctive phenotypic and genetic homogeneity that is independent of their country of origin (Figure 2).

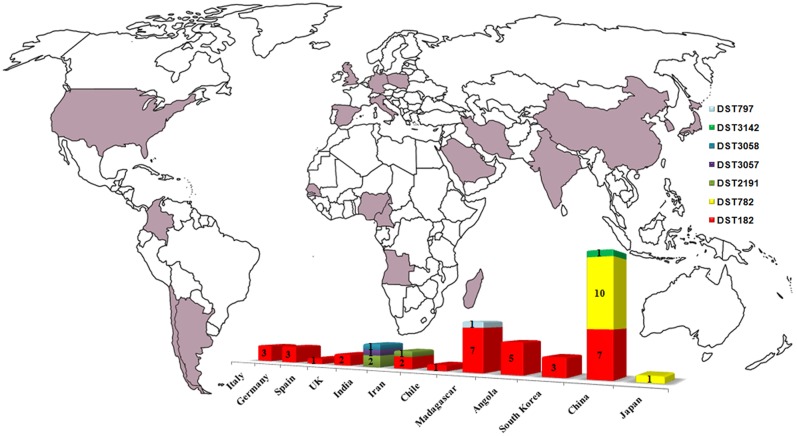

FIGURE 2.

Worldwide diffusion of C. africana (purple) and distribution, by country, of the MLST types currently known. The graphic was built by combining data present in the C. albicans MLST database including those reported in Figure 1, Song et al. (2014), and Hu et al. (2015).

To better investigate the level of genetic diversity among C. africana strains we genotyped them using MLST and AFLP methods. Sequencing of 373–491 bp fragments from the coding region of all the seven genes included in the MLST scheme, resulted in a total of 2,883 aligned nucleotides for each strain. Also the MLST analysis revealed a substantial degree of genetic homogeneity as all C. africana, except the Chinese strain 8866 and Indian strains VPCI891/P/12 and VPCI896/P/12, exhibited the same allele type assigned by the MLST database at the following six loci, CaAAT1a (allele 33), CaACC1 (allele 7), CaADP1 (allele 32), CaSYA1 (allele 2), CaVPS13 (allele 61), and CaZWF1b (allele 48) (Figure 1). On the contrary, the CaMPIb locus, encoding the mannose phosphate isomerase, was the most variable marker that contributed significantly to the classification of most C. africana strains into different DSTs (Figure 1). Only the Chinese C. africana 8866 strain (DST3142) was found to be different at the VPS13 locus encoding for a putative vacuolar protein, which carries the allele number 58 rather than allele 61 as found in all other C. africana strains (Figure 1). Sequence analysis of the allele 58 revealed that the VPS13 locus was affected by LOH at the position 53 in which the heterozygous state (G/A polymorphism) was replaced by GG-homozygosity.

The Indian and Chinese strains exhibited the greatest genetic variability at the CaMPIb locus (Figure 1). Combining the allele types at all seven loci resulted in six unique DSTs (Figure 1) of which DST182 was the most frequent and geographically dispersed (14/26; ∼54%) followed by DST782 (6/26; 23%) that, along with DST3142, was exclusively found in C. africana strains from China (Figures 1, 2). The remaining three types (DST2191, DST3057, and DST3058) were observed only in Indian and Iranian strains indicating a considerable genetic variability in C. africana isolates from these countries (Figure 2).

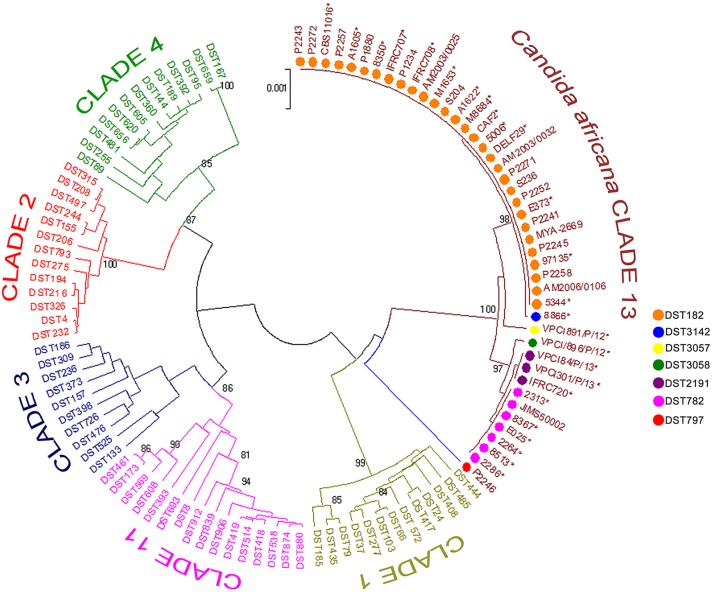

Phylogenetics analysis of the MLST data revealed that our C. africana grouped with isolates from the C. albicans clade 13 (Figure 3), which appears to be enriched with mating-type a/α isolates of genotype A, carrying a specific HXK1 gene mutation.

FIGURE 3.

Phylogenetic tree generated by UPGMA analysis using concatenated MLST sequences of the C. africana strains listed in Figure 1 and selected DSTs representing the five most populous C. albicans clades (1, 2, 3, 4, and 11) and clade 13. The evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance method and are in the units of the number of base differences per site. Bootstrap support values above 80% are indicated at the nodes. ∗Indicates yeast strains examined in this study.

Compared to MLST, the AFLP fingerprinting analysis yielded greater genotypic heterogeneity among C. africana strains (Figure 1). Using an arbitrary cut-off value of 95% similarity, we found 25 different AFLP genotypes. Only the Iranian strains IFRC707 and IFRC708 could not be differentiated using this threshold (Figure 1). These two Iranian DST182 strains were closely related to the Indian strain VPCI84/P/13 that showed a different MLST type (DST2191). The UPGMA dendrogram shows that all three strains form a cluster of isolates well-separated from the rest of the C. africana strains examined (Figure 1). However, the C. africana M8684 strain from Madagascar was the one with the highest degree of genetic diversity found in this study.

Discussion

Candida albicans is by far the most well-studied species among all clinically relevant fungal pathogens. Genetically, the population structure of this species is quite heterogeneous and consists of at least 18 different MLST clades (McManus and Coleman, 2014) in which phenotypic plasticity of the isolates appears to be driven mainly by LOH events as well as by chromosomal aneuploidies (Ford et al., 2015; Hirakawa et al., 2015).

Among the current C. albicans MLST clades, clade 13 is undoubtedly the most intriguing since it forms a single well resolved and strongly supported cluster of isolates, evolutionarily distinct from all the others (Odds et al., 2007). Isolates assigned to this group were originally proposed as representatives of a new species, C. africana (Tietz et al., 2001), and represent the most striking example of phenotypic variation occurring in C. albicans. In fact, compared to typical C. albicans isolates, C. africana showed a number of unusual phenotypes (Tietz et al., 2001; Romeo et al., 2013) including the inability to assimilate GlcNAc, which appears to be a prerogative of clade 13 isolates. This is well-supported by our molecular data which suggested a specific association between the frameshift mutation found in C. africana HXK1 gene and different MLST types ascribed to this clade.

Clade 13 strains showed a global distribution and a particular tendency to cause mainly genital infections. Our results revealed that this clade is enriched with genotype A and MTL heterozygous (a/α) strains carrying specific polymorphisms at HXK1 and HWP1 loci. Combining our MLST data with those of the Candida MLST database and other studies (Song et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2015) we found that DTS182 was the most common and geographically dispersed strain type having been isolated in Europe, South America, Africa, and Asia (Figure 2). Most of the strains were from vaginal specimens but examples of DST182 genotypes were also recovered from glans penis, rectal swab, urine, and blood samples (Odds et al., 2007; Song et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2015).

Analyses of genotypic richness and diversity on a continental level showed that the highest genetic variation occurs in Asia, especially in India, where specific and phylogenetically closely related MLST genotypes were exclusively found (Figures 1, 2). In addition, the unique Japanese strain (JIMS500002) described by Odds et al. (2007) and most of the vaginal Chinese isolates (6/11; ∼54%) examined in this study, were DST782 (Figures 1, 2), the commonest Asian genotype (Figure 2). This supports the recent findings of Hu et al. (2015) who reported that 80% of the C. africana isolates, recovered from Chinese male patients with balanoposthitis, belonged to this genotype.

In this study, five of the seven MLST loci sequenced showed identical sequences and lack SNP diversity. However, in MPIb and VPS13 loci we observed heterozygous sites, which were lost in all DST782 (MPIb gene) strains including DST3142 (VPS13 gene). This suggests a reasonable low level of divergence in the population structure of C. africana, possibly because it has evolved only recently from C. albicans (Sharma et al., 2014). This low level of sequence variation observed in many MLST loci, suggests also that this typing technique may not be ideal for local epidemiological studies and/or tracking clones in hospital outbreaks (Hu et al., 2015). In our opinion the application of techniques that allow analyses of a large fraction of a genome should be more appropriate. In fact, analysis performed by AFLP markers provided evidence for a significantly greater genetic differentiation.

The AFLP profiles reported in this study suggest a considerable genetic diversity in C. africana strains even though they were all isolated from the same kind of clinical specimens and most showed the same MLST genotype. AFLP patterns obtained in this study show a high number of polymorphic fragments, which are unusual for fungal species with a predominant clonal reproduction mechanism (Hensgens et al., 2009). Therefore, this also suggests that in our strains recombination occurs and that could significantly contribute to the genetic diversity seen in C. africana, which represents one of the best examples of divergent evolution in C. albicans.

Author Contributions

OR, AC, and JM conceived the study. CS, LG, AA-H, SF, and HB prepared the strains and did phenotypic identification. CS, LG, DG, and MRF performed molecular tests, multi-locus sequence typing, and analyzed the data. FH performed AFLP genotyping and interpreted the data. OR, AC, JM, and FH prepared the manuscript. SdH, AA-H, and SF participated in discussions and provided suggestions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer SD declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors SdH and a shared affiliation with the authors SdH, AA-H to the handling Editor, who ensured that the process met the standards of a fair and objective review.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Hans-Jürgen Tietz (Institut für Pilzkrankheiten, Berlin, Germany) and Dr. Guilliermo Quindos (Universidad del País Vasco, Bilbao, Spain) for supplying the German and Spanish C. africana strains. We are also very grateful to Dr. Fabio Scordino (IRCCS-Centro Neurolesi “Bonino-Pulejo”, Messina, Italy) for providing technical help and Prof. Giuseppe Criseo for his helpful suggestions about the manuscript.

Footnotes

References

- Alonso-Vargas R., Elorduy L., Eraso E., Cano F. J., Guarro J., Pontón J., et al. (2008). Isolation of Candida africana, probable atypical strains of Candida albicans, from a patient with vaginitis. Med. Mycol. 46 167–170. 10.1080/13693780701633101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. J., Forche A., Berman J. (2014). Rapid mechanisms for generating genome diversity: whole ploidy shifts, aneuploidy, and loss of heterozygosity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4:a019604 10.1101/cshperspect.a019604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borman A. M., Szekely A., Linton C. J., Palmer M. D., Brown P., Johnson E. M. (2013). Epidemiology, antifungal susceptibility, and pathogenicity of Candida africana isolates from the United Kingdom. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51 967–972. 10.1128/JCM.02816-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougnoux M. E., Tavanti A., Bouchier C., Gow N. A., Magnier A., Davidson A. D., et al. (2003). Collaborative consensus for optimized multilocus sequence typing of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 5265–5266. 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5265-5266.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary A., Anil Kumar V., Sharma C., Prakash A., Agarwal K., Babu R., et al. (2014). Multidrug-resistant endemic clonal strain of Candida auris in India. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33 919–926. 10.1007/s10096-013-2027-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieng Y., Sow D., Ndiaye M., Guichet E., Faye B., Tine R., et al. (2012). Identification of three Candida africana strains in Senegal. J. Mycol. Med. 22 335–340. 10.1016/j.mycmed.2012.07.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felice M. R., Gulati M., Giuffrè L., Giosa D., Di Bella L. M., Criseo G., et al. (2016). Molecular characterization of the N-acetylglucosamine catabolic genes in Candida africana, a natural N-acetylglucosamine kinase (HXK1) mutant. PLoS ONE 11:0147902 10.1371/journal.pone.0147902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forche A., Alby K., Schaefer D., Johnson A. D., Berman J., Bennett R. J. (2008). The parasexual cycle in Candida albicans provides an alternative pathway to meiosis for the formation of recombinant strains. PLoS Biol. 6:110 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. B., Funt J. M., Abbey D., Issi L., Guiducci C., Martinez D. A., et al. (2015). The evolution of drug resistance in clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Elife 4:e00662 10.7554/eLife.00662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensgens L. A., Tavanti A., Mogavero S., Ghelardi E., Senesi S. (2009). AFLP genotyping of Candida metapsilosis clinical isolates: evidence for recombination. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46 750–758. 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa M. P., Martinez D. A., Sakthikumar S., Anderson M. Z., Berlin A., Gujja S., et al. (2015). Genetic and phenotypic intra-species variation in Candida albicans. Genome Res. 25 413–425. 10.1101/gr.174623.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Yu A., Chen X., Wang G., Feng X. (2015). Molecular characterization of Candida africana in genital specimens in Shanghai, China. Biom ed. Res. Int. 2015:185387 10.1155/2015/185387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G., Yi S., Sahni N., Daniels K. J., Srikantha T., Soll D. R. (2010). N-acetylglucosamine induces white to opaque switching, a mating prerequisite in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 6:1000806 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull C. M., Johnson A. D. (1999). Identification of a mating type-like locus in the asexual pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Science 285 1271–1275. 10.1126/science.285.5431.1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka J. B. (2012). N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) functions in cell signalling. Scientifica 2012:489208 10.6064/2012/489208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum D. M., Castillo L., Nather K., Munro C. A., Brown A. J., Gow N. A., et al. (2009). Property differences among the four major Candida albicans strain clades. Eukaryot. Cell 8 373–387. 10.1128/EC.00387-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough M. J., Clemons K. V., Stevens D. A. (1999). Molecular and phenotypic characterization of genotypic Candida albicans subgroups and comparison with Candida dubliniensis and Candida stellatoidea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37 417–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus B. A., Coleman D. C. (2014). Molecular epidemiology, phylogeny and evolution of Candida albicans. Infect. Genet. Evol. 21 166–178. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngouana T. K., Krasteva D., Drakulovski P., Toghueo R. K., Kouanfack C., Ambe A., et al. (2015). Investigation of minor species Candida africana, Candida stellatoidea and Candida dubliniensis in the Candida albicans complex among Yaoundé (Cameroon) HIV-infected patients. Mycoses 58 33–39. 10.1111/myc.12266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnadi N. E., Ayanbimpe G. M., Scordino F., Okolo M. O., Enweani I. B., Criseo G., et al. (2012). Isolation and molecular characterization of Candida africana from Jos, Nigeria. Med. Mycol. 50 765–767. 10.3109/13693786.2012.662598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odds F. C., Bougnoux M. E., Shaw D. J., Bain J. M., Davidson A. D., Diogo D., et al. (2007). Molecular phylogenetics of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 6 1041–1052. 10.1128/EC.00041-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagniez F., Jimenez-Gil P., Mancia A., Le Pape P. (2015). Étude comparative in vivo de la virulence de Candida africana et de C. albicans stricto sensu. J. Mycol. Med. 25 107 10.1016/j.mycmed.2015.02.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M., Neofytos D., Diekema D., Azie N., Meier-Kriesche H. U., Quan S. P., et al. (2012). Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3648 patients: data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH Alliance®) registry, 2004-2008. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 74 323–331. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quindós G. (2014). Epidemiology of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis. A changing face. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 31 42–48. 10.1016/j.riam.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Leguizamón G., Fiori A., López L. F., Gómez B. L., Parra-Giraldo C. M., Gómez-López A., et al. (2015). Characterising atypical Candida albicans clinical isolates from six third-level hospitals in Bogotá, Colombia. BMC Microbiol. 15 199 10.1186/s12866-015-0535-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo O., Criseo G. (2008). First molecular method for discriminating between Candida africana, Candida albicans, and Candida dubliniensis by using hwp1 gene. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 62 230–233. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo O., Criseo G. (2009). Molecular epidemiology of Candida albicans and its closely related yeasts Candida dubliniensis and Candida africana. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47 212–214. 10.1128/JCM.01540-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo O., Criseo G. (2011). Candida africana and its closest relatives. Mycoses 54 475–486. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2010.01939.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo O., De Leo F., Criseo G. (2011). Adherence ability of Candida africana: a comparative study with Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. Mycoses 54 57–61. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo O., Tietz H. J., Criseo G. (2013). Candida africana: Is it a fungal pathogen? Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 7 192–197. 10.1007/s12281-013-0142-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scaduto C. M., Bennett R. J. (2015). Candida albicans the chameleon: transitions and interactions between multiple phenotypic states confer phenotypic plasticity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 26 102–108. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y., Fan S., Liu X., Li J. (2014). Prevalence of Candida albicans-closely related yeasts, Candida africana and Candida dubliniensis, in vulvovaginal candidiasis. Med. Mycol. 52 636–640. 10.1093/mmy/myu003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma C., Muralidhar S., Xu J., Meis J. F., Chowdhary A. (2014). Multilocus sequence typing of Candida africana from patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis in New Delhi, India. Mycoses 57 544–552. 10.1111/myc.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song E. S., Shin J. H., Jang H. C., Choi M. J., Kim S. H., Bougnoux M. E., et al. (2014). Multilocus sequence typing for the analysis of clonality among Candida albicans strains from a neonatal intensive care unit. Med. Mycol. 52 653–658. 10.1093/mmy/myu028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavanti A., Gow N. A., Senesi S., Maiden M. C., Odds F. C. (2003). Optimization and validation of multilocus sequence typing for Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 3765–3776. 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3765-3776.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theill L., Dudiuk C., Morano S., Gamarra S., Nardin M. E., Méndez E., et al. (2016). Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of Candida albicans and its related species Candida dubliniensis and Candida africana isolated from vulvovaginal samples in a hospital of Argentina. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 48 43–49. 10.1016/j.ram.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietz H. J., Hopp M., Schmalreck A., Sterry W., Czaika V. (2001). Candida africana sp. nov., a new human pathogen or a variant of Candida albicans?. Mycoses 44 437–445. 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2001.00707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietz H. J., Küssner A., Thanos M., Pinto De Andreade M., Presber W., Schönian G. (1995). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of unusual vaginal isolates of Candida albicans from Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33 2462–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuite N. L., Lacey K. (2013). Overview of invasive fungal infections. Methods Mol. Biol. 968 1–23. 10.1007/978-1-62703-257-5_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhaneni S., Mody R. K., Walker T., Chiller T. (2016). The global burden of fungal diseases. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 30 1–11. 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdanparast S. A., Khodavaisy S., Fakhim H., Shokohi T., Haghani I., Nabili M., et al. (2015). Molecular Characterization of highly susceptible Candida africana from vulvovaginal candidiasis. Mycopathologia 180 317–323. 10.1007/s11046-015-9924-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]