Abstract

Endoglycoceramidases (EGCases) specifically hydrolyze the glycosidic linkage between the oligosaccharide and the ceramide moieties of various glycosphingolipids, and they have received substantial attention in the emerging field of glycosphingolipidology. However, the mechanism regulating the strict substrate specificity of these GH5 glycosidases has not been identified. In this study, we report a novel EGCase I from Rhodococcus equi 103S (103S_EGCase I) with remarkably broad substrate specificity. Based on phylogenetic analyses, the enzyme may represent a new subfamily of GH5 glycosidases. The X-ray crystal structures of 103S_EGCase I alone and in complex with its substrates monosialodihexosylganglioside (GM3) and monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1) enabled us to identify several structural features that may account for its broad specificity. Compared with EGCase II from Rhodococcus sp. M-777 (M777_EGCase II), which possesses strict substrate specificity, 103S_EGCase I possesses a longer α7-helix and a shorter loop 4, which forms a larger substrate-binding pocket that could accommodate more extended oligosaccharides. In addition, loop 2 and loop 8 of the enzyme adopt a more open conformation, which also enlarges the oligosaccharide-binding cavity. Based on this knowledge, a rationally designed experiment was performed to examine the substrate specificity of EGCase II. The truncation of loop 4 in M777_EGCase II increased its activity toward GM1 (163%). Remarkably, the S63G mutant of M777_EGCase II showed a broader substrate spectra and significantly increased activity toward bulky substrates (up to >1370-fold for fucosyl-GM1). Collectively, the results presented here reveal the exquisite substrate recognition mechanism of EGCases and provide an opportunity for further engineering of these enzymes.

Keywords: crystal structure, glycoside hydrolase, protein engineering, sphingolipid, substrate specificity

Introduction

Glycosphingolipids (GSLs)2 are ubiquitous cell surface components found in essentially all eukaryotes, some prokaryotes, and viruses. Endoglycoceramidases (EGCases, EC 3.2.1.123) are a group of glycoside hydrolases that cleave the linkage between the oligosaccharide and the ceramide moieties of various GSLs. The reaction releases intact oligosaccharides that can be examined using glycoblotting and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS) to analyze the cellular glycosphingolipid-glycome, potentially leading to a comprehensive analysis of GSLs and the discovery of new GSL species (1, 2).

Several EGCases have been identified in prokaryotes (3, 4) and eukaryotes, particularly in invertebrates (5–9). These enzymes show distinct substrate specificities toward oligosaccharide moieties (supplemental Table S1). The eukaryotic EGCases from jellyfish and hydra hydrolyze ganglio- and lacto-series GSLs (8, 9). EGCrP1 and EGCrP2, which are expressed in the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans, are active against glucosylceramide (GlcCer) and various steryl-β-glucosides (10, 11). Three molecular species of EGCase with distinct specificities, designated EGCase I, II, and III, were identified in the culture fluid of Rhodococcus sp. M-750 (12). EGCase III (later renamed endogalactosylceramidase, EGALC) specifically hydrolyzes 6-gala-series GSLs (13). EGCase II possesses a similar specificity for eukaryotic EGCases (14). EGCase II from Rhodococcus sp. is now commercially available, but it is not suitable for a comprehensive analysis of GSLs because of its narrow specificity (i.e. weak activity for some biologically important antigens, such as globo-series GSLs and fucosyl-GM1) (15). By contrast, Rhodococcal EGCase I exhibits a broad substrate profile. EGCase I not only hydrolyzes ganglio- and lacto-series GSLs but also fucosyl-GM1 and globo-series GSLs that are resistant to eukaryotic EGCase and EGCase II (15).

In contrast to most GH5 members that hydrolyze entirely polar polysaccharide substrates (e.g. cellulose, xylan, and mannan), EGCases display an unusual substrate specificity that accepts amphiphilic GSLs consisting of a hydrophilic oligosaccharide headgroup and a hydrophobic ceramide tail. The crystal structure of EGCase II from Rhodococcus sp. strain M-777 (M777_EGCase II) suggests that the substrate-binding site of EGCase is split into two noticeably different parts: a wide, polar cavity that binds the polyhydroxylated oligosaccharide moiety and a narrow, hydrophobic tunnel that binds the ceramide moiety of the substrates (16). However, the distinct substrate specificities of different EGCases imply different substrate-binding modes, particularly for the oligosaccharide moiety. Unfortunately, because only one crystal structure of EGCase is available so far, detailed investigations of the substrate recognition mechanism have been hampered.

In this study, we report the molecular cloning and enzymatic characterization of a novel EGCase I from Rhodococcus equi 103S (103S_EGCase I). The recombinant protein showed high catalytic activity, broad substrate specificity, and a remarkably high expression level in Escherichia coli. Based on phylogenetic analyses, EGCase I may represent a new subfamily of GH5 glycosidases. The X-ray crystal structures of 103S_EGCase I alone and in complex with its substrates monosialodihexosylganglioside (GM3) and monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1) were obtained and compared with the structures of M777_EGCase II. A detailed analysis of the substrate-binding mode offers valuable information that enables us to better understand its substrate recognition mechanism, which may facilitate subsequent enzyme engineering studies for the design of better EGCases.

Results

Overexpression and Characterization of EGCase I from R. equi 103S

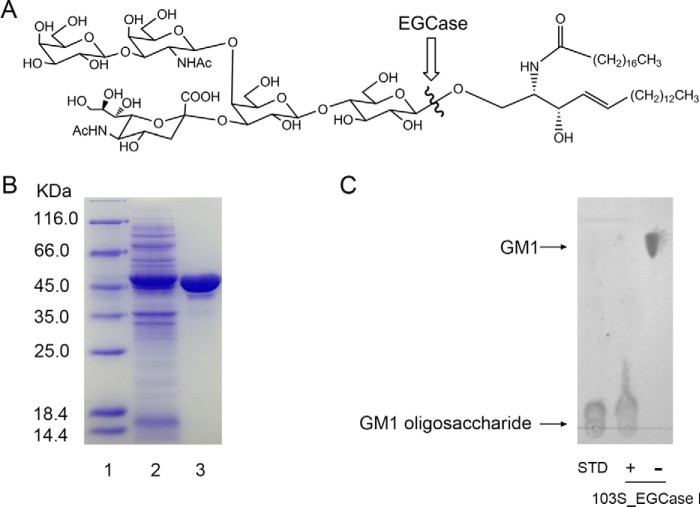

A putative EGCase from R. equi 103S (103S_EGCase I) (GenBankTM accession number CBH49814) shares 90% sequence identity with EGCase I from Rhodococcus sp. M-750 (M750_EGCase I) (supplemental Fig. S1) (15). The gene was codon-optimized for E. coli, chemically synthesized, and subcloned into a pET28a vector. 103S_EGCase I was functionally overexpressed in E. coli at a very high level (Fig. 1). In a typical experiment, 80 mg/liter purified protein was obtained from a 1-liter E. coli shaking flask culture after 12 h of induction, which is much higher than the previously reported expression of the M750_EGCase I in the Rhodococcus system (∼1 mg/liter, 24 h of induction).

FIGURE 1.

Purification and activity assessment of recombinant 103S_EGCase I. A, a typical substrate (GM1 ganglioside) for EGCase. The position of EGCase endohydrolysis is indicated by the wavy line. B, SDS-PAGE showing the purification of the recombinant 103S_EGCase I. Lane 1, protein marker; lane 2, sample corresponding to 20 μl of the culture of E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS transformed with pET28a-103S_EGCase I after 12 h of induction; lane 3, 10 μg of purified recombinant 103S_EGCase I. C, TLC showing the oligosaccharides released from GM1 by 103S_EGCase I. GM1 (10 nmol) was incubated with 1 μg of the recombinant 103S_EGCase I at 37 °C for 60 min. The reaction was terminated by heating the reaction mixture in a boiling water bath for 5 min. After high speed centrifugation, the supernatants were loaded onto a TLC plate and developed with chloroform, methanol, 0.02% CaCl2 (5:4:1, v/v/v). GSLs and oligosaccharides were visualized with orcinol-H2SO4 reagent. STD, GM1 oligosaccharide standard; −, without 103S_EGCase I; +, with 103S_EGCase I.

The substrate specificity of 103S_EGCase I appeared to be similar to that of M750_EGCase I (Table 1) (the raw HPLC data are shown in supplemental Fig. S2). 103S_EGCase I hydrolyzed various GSLs possessing the β-glucosyl-Cer linkage, including GM3 (100%), GM1 (100%), and lactosylceramide (LacCer) (63%), but showed no activity toward GlcCer and galactosylceramide (GalCer) under the conditions used in this study. Compared with M777_EGCase II, 103S_EGCase I hydrolyzed various GSLs at a much higher speed. For example, the specific activities of 103S_EGCase I for GM3, GM1, and LacCer were 8-, 34-, and 8-fold higher, respectively, than the specific activities of M777_EGCase II. 103S_EGCase I also efficiently hydrolyzed fucosyl-GM1 (66%) and globotetraosylceramide (Gb4Cer) (95%), whereas M777_EGCase II showed no activity toward fucosyl-GM1 and very weak activity toward Gb4Cer (6.3%). The optimal substrate for 103S_EGCase I was GM1, whereas M777_EGCase II preferred GM3 over the GSLs with larger and branched sugar moieties, such as GM1, fucosyl-GM1, and Gb4Cer. Thus, these two enzymes probably possess different substrate-binding sites.

TABLE 1.

Substrate specificities of 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II

| Name | Structure | Specific activitya |

Reaction yieldb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103S_EGCase I | M777_EGCase II | 103S_EGCase I | M777_EGCase II | ||

| nmol/min/μg | % | % | |||

| GlcCer | Glcβ1–1′Cer | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0 | 0 |

| GalCer | Galβ1–1′Cer | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0 | 0 |

| LacCer | Galβ1–4Glcβ1–1′Cer | 1.80 ± 0.15 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 62.8 ± 5.5 | 44.6 ± 5.1 |

| GM3 | NeuAcα2–3Galβ1–4Glcβ1–1′Cer | 4.93 ± 0.64 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 100 ± 3.0 | 95.9 ± 3.5 |

| GM1 | Galβ1–3GalNAcβ1–4 (NeuAcα2–3)Galβ1–4Glcβ1–1′Cer | 6.44 ± 0.49 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 100 ± 4.6 | 35.2 ± 4.3 |

| Fucosyl-GM1 | Fucα1–2Galβ1–3GalNAcβ1–4 (NeuAcα2–3)Galβ1–4Glcβ1–1′Cer | 3.21 ± 0.25 | <0.0001 | 65.8 ± 3.2 | 0 |

| Gb4Cer | GalNAcβ1–3Galα1–4Galβ1–4Glcβ1–1′Cer | 0.45 ± 0.05 | <0.0001 | 95.4 ± 3.3 | 6.3 ± 1.5 |

a The substrate specificity toward various GSLs is presented as the specific hydrolytic activities in the initial stage of the reaction. Values represent the means ±S.D. (n = 3).

b The substrate specificity toward various GSLs is presented as the reaction yield (%) when the reaction reached equilibrium and was calculated using the equation, peak area for oligosacchrides ×100/peak area for 0.5 mm oligosaccharide. Values represent means ±S.D. (n = 3). Representative HPLC chromatograms of the reaction yield assay are presented in supplemental Fig. S2.

Based on the determination of the steady-state kinetic parameters, 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II had similar Km values for the ganglioside GM1 (the raw data are shown in supplemental Fig. S3). However, the kcat and the kcat/Km of 103S_EGCase I were 119- and 130-fold higher, respectively, than the values for M777_EGCase II (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters for 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II using GM1 as the substrate

Kinetic assays were performed in triplicate. The fitting curves for the kinetic parameters are presented in supplemental Fig. S3.

| Enzyme | kcat | Km | kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| min−1 | mm | min−1 mm−1 | |

| 103S_EGCase I | 630 ± 50 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 2740 |

| M777_EGCase II | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 21 |

Phylogenetic Analysis of EGCases

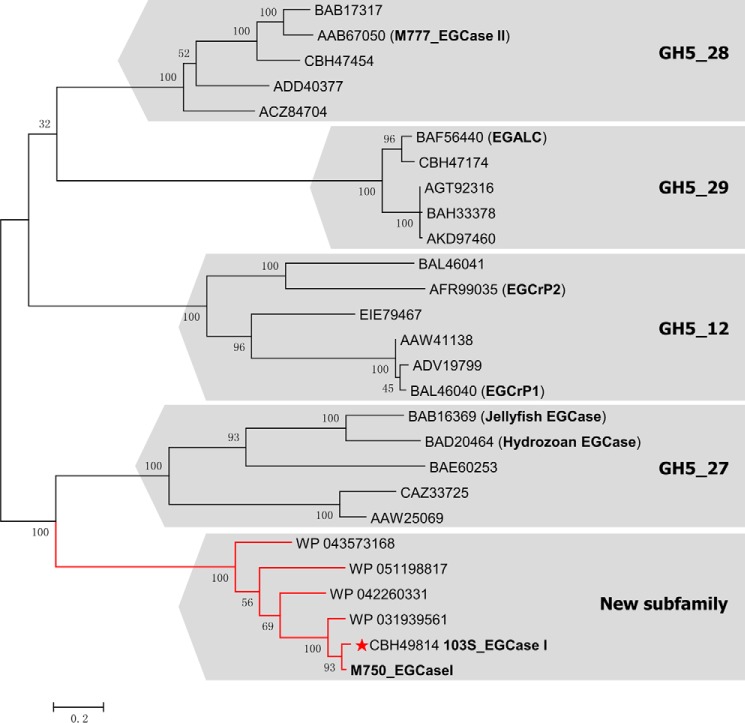

All of the known EGCases belong to the GH5 glycosidase family. EGCrP1 and EGCrP2 are assigned to subfamily GH5_12, eukaryotic EGCases belong to subfamily GH5_27, EGCase II belongs to subfamily GH5_28, and EGALC belongs to subfamily GH5_29 (17). However, EGCase I has not been classified into any GH5 subfamily. A phylogenetic analysis was performed to better understand the evolutionary background of EGCase I. The amino acid sequence of M750_EGCase I was used as a query for a BLAST search of the NCBI non-redundant protein sequence database, and five homologous sequences were collected with >50% sequence identity, including 103S_EGCase I (90%), WP 031939561 from Rhodococcus defluvii (86%), WP 042260331 from Nocardia brasiliensis (65%), WP 043573168 from Actinopolyspora erythraea (60%), and WP 051198817 from Gordonia shandongensis (57%). These sequences and 21 other EGCase-related proteins extracted from the CAZy database were used to derive a phylogenetic tree using the maximum likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model. As shown in Fig. 2, the tree clearly assigned these sequences to their corresponding subfamilies (17), confirming the validity of the phylogenetic analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenetic tree of EGCase and its homologs in the GH5 family based on the maximum likelihood method with 100 bootstrap replications conducted by MEGA6. The sequence of M750_EGCase I was obtained from the literature (15), whereas the other sequences included in the analysis were obtained from the NCBI database. All bootstrap values are displayed. Scale bar, 0.2 amino acid substitutions/site. The three-dimensional structure of 103S_EGCase I (GenBankTM accession number CBH49814) from R. equi 103S solved in this study is marked with a red star. M777_EGCase II (GenBankTM accession number AAB67050) was from Rhodococcus sp. strain M-777, EGALC (GenBankTM accession number BAF56440) was from R. equi, EGCrP1 (GenBankTM accession number BAL46040) was from C. neoformans, and EGCrP2 (GenBankTM accession number AFR99035) was from C. neoformans. The GH5 subfamily number for each branch is shown.

103S_EGCase I and M750_EGCase I were obviously clustered with other putative EGCase I sequences in a branch distinct from the other EGCase-related subfamilies, suggesting that these EGCase I-related enzymes may belong to a new subfamily of the GH5 family. The assignment of EGCase I to a new subfamily was consistent with the observation that it possessed distinct substrate specificity compared with other EGCases (supplemental Table S1).

Architecture of 103S_EGCase I

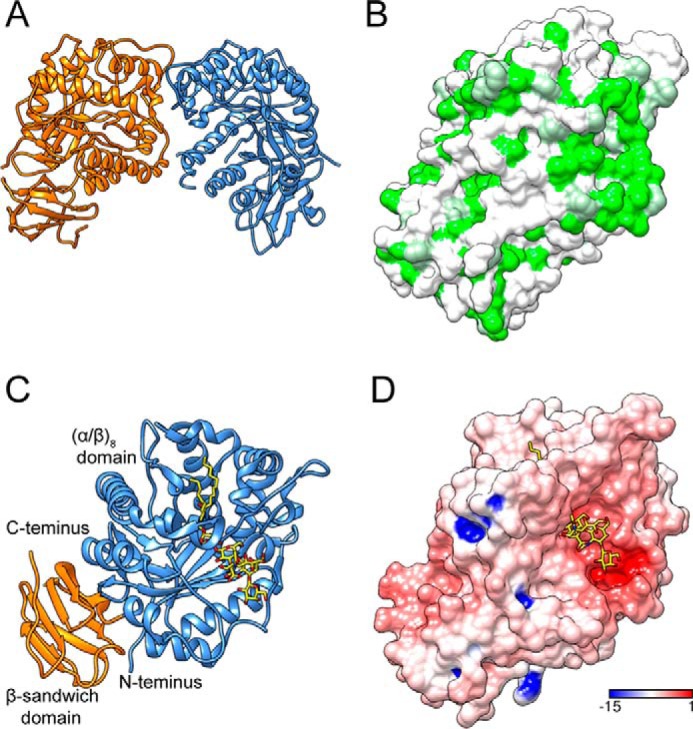

The crystal structure of 103S_EGCase I was determined at 2.11 Å resolution with the space group C121. Rwork and Rfree were 19.4 and 22.3%, respectively. Two 103S_EGCase I molecules were present in one asymmetric unit (Fig. 3A). The two monomers of 103S_EGCase I were nearly identical, with an r.m.s.d. of 0.52 Å over 416 residues. Residues 68, 300–307, 309, and 342–343 were not modeled in chain B because of a poor electron density. The monomer-monomer interface buried an extensive, predominantly hydrophobic area of ∼962 Å2, which corresponded to 12.7% of the total surface area of one monomer, as calculated by PISA (Fig. 3B) (18). The interface had three hydrogen bonds and 43 non-bonded contacts, suggesting that the observed dimer was not the biological form because the crystal contacts of homodimers or protein complexes tend to have 10–20 hydrogen bonds (19). Moreover, the interface between these two molecules had a 3.36% probability of being the biological interface according to the NOXclass analysis (20), providing further support for the hypothesis that the dimer only results from crystallographic packing.

FIGURE 3.

Overall structures of 103S_EGCase I and its GM1 substrate complex. A, ribbon diagram of 103S_EGCase I structure dimer. B, hydrophobic surface potential of 103S_EGCase I chain A (green, hydrophobic; white, polar). The molecular surface was colored by amino acid hydrophobicity using the KD hydrophobicity scale (43). C, ribbon representation of the structure of the 103S_EGCase I-GM1 complex. The N-terminal domain (cornflower blue) adopts an (α/β)8 fold, and the C-terminal domain (orange) adopts a β-sandwich fold. D, electrostatic surface potential of 103S_EGCase I (red, electronegative; blue, electropositive; contoured from −15 to 1 kT/e).

Each monomer of 103S_EGCase I contained two distinct domains. The N-terminal domain exhibited the characteristic (α/β)8 TIM-barrel fold of all GH5 family members; it contained an internal core of eight β-strands connected by loops of various sizes to an external layer of eight α-helices. The C-terminal domain formed a β-sandwich fold composed of two sheets of four antiparallel β-strands (Fig. 3, A and C). Two disulfide bonds were present in the 103S_EGCase I structure: Cys224–Cys229 and Cys294–Cys313. A structure search using the DALI server (21) suggested that the crystal structure of 103S_EGCase I closely matched the structure of M777_EGCase II (PDB code 2OYM, DALI Z = 41.7, and r.m.s.d. = 2.6 Å for 400 equivalent Cα positions), despite their low sequence similarity (30% identity). Other similar structures included a cellulase (PDB code 4HTY, DALI Z = 26.6, and r.m.s.d. = 2.6 Å for 269 residues), an endo-β-mannanase (PDB code 4QP0, DALI Z = 25.8, and r.m.s.d. = 2.8 Å for 294 residues) (22), and a mannosyl-oligosaccharide glucosidase (PDB code 1UUQ, DALI Z = 25.4, and r.m.s.d. = 2.8 Å for 314 residues) (23).

The C-terminal domain of 103S_EGCase I displayed a typical β-sandwich fold that resembled the folds of many carbohydrate-binding modules of glycoside hydrolases (24). The β-sandwich domain may not be involved in binding the carbohydrate portion of the substrate, because it located on the opposite face of the (α/β)8 domain. Similar domains have been observed in other GH5 family members, including M777_EGCase II (16), endo-xyloglucanase (25), and β-glucanase (26). Indeed, many of these carbohydrate-binding modules do not bind the substrate independently (27). This domain may simply stabilize the catalytic (α/β)8 domain.

Structure of the Enzyme-Substrate Complex

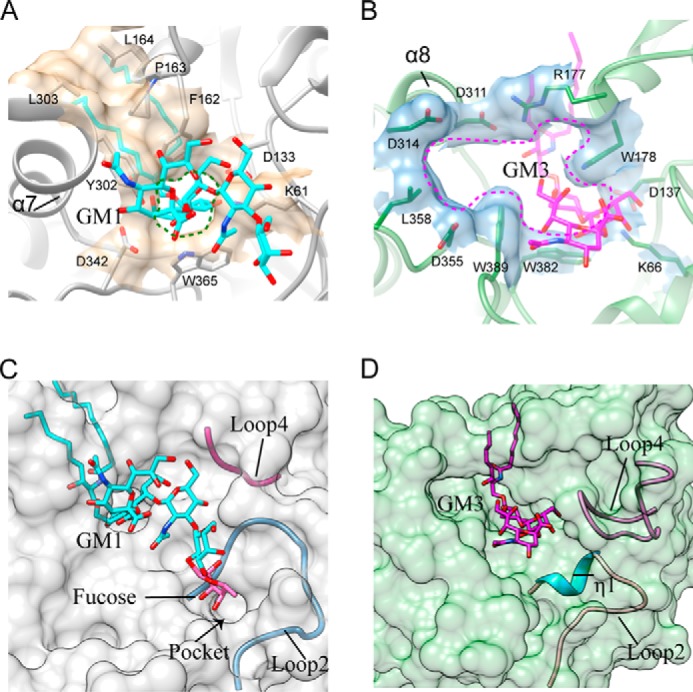

103S_EGCase I was co-crystallized with each of its substrates, GM1 and GM3, to further understand the structural basis of the broad substrate specificity of EGCase I. Co-crystallization experiments were performed with the nucleophile mutant 103S_EGCase I/E339S to prevent substrate hydrolysis. The 103S_EGCase I-GM1 structure was determined at 2.15 Å resolution, and the 103S_EGCase I-GM3 structure was determined at 1.915 Å resolution. Both structures belonged to space group C121 and contained two molecules per asymmetric unit. Clear electron density was evident for all the pyranoside rings, with the exception of the sialic acid unit of GM3, which was only partially clear (Fig. 4, A–C). In both complexes, the ceramide moieties were partially distinguished. The superposition of the 103S_EGCase I-GM1 or 103S_EGCase I-GM3 structure on the 103S_EGCase I structure showed that the overall protein structure was almost unchanged, reflected in the r.m.s.d. of 0.21 Å/0.23 Å over 449 common Cα atoms between the 103S_EGCase I structure and the ligand-bound forms, respectively.

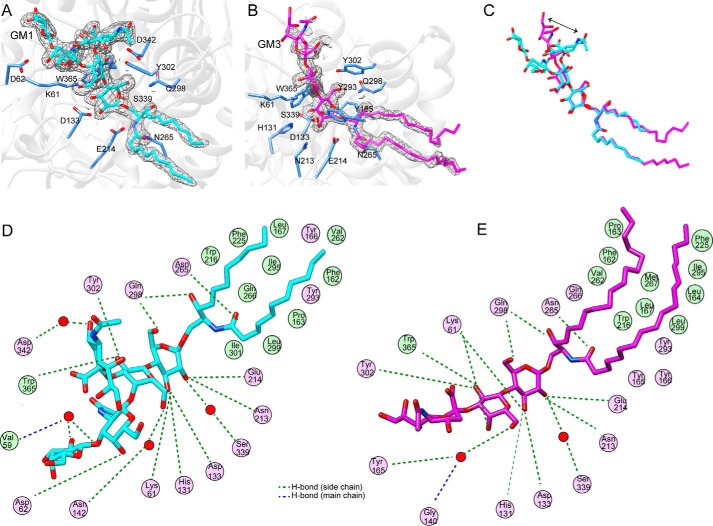

FIGURE 4.

Ligand-binding mode of 103S_EGCase I. A, close-up view of the GM1-binding site in 103S_EGCase I/E339S. The 2Fo − Fc electron density map was contoured at 1σ around GM1 in gray mesh. B, close-up view of the GM3-binding site in 103S_EGCase I/E339S. The 2Fo − Fc electron density map was contoured at 1σ around GM3 in gray mesh. C, comparison of the conformations of GM1 (cyan) and GM3 (magenta). The arrow shows the different portions of the sialic acid residue. D, schematic view of the interaction of 103S_EGCase I with GM1. E, schematic view of the interaction of 103S_EGCase I with GM3. This panel was generated using MOE.

Similar to the crystal structure of M777_EGCase II, the substrate-binding site of 103S_EGCase I contained two distinct regions. On one side of the catalytic residues, the active site channel was broad (∼27.9 Å) and mainly lined with polar residues that formed the binding cavity for the oligosaccharide moiety. On the opposite side, the active site narrowed to an ∼5.8-Å channel that was predominantly lined with hydrophobic residues, forming the ceramide-binding tunnel. This tunnel subsequently opened onto a distinctly flat surface of the enzyme, which also appeared largely composed of hydrophobic residues (Fig. 3, B and D).

The coordination of GM1 and GM3 in the enzyme is described in detail in Fig. 4, D and E. The glucose unit was held in a fixed position by a hydrogen bond network consisting of Lys61, His131, Asp133, Asn213, Glu214, and Gln298 residues. These residues are highly conserved among EGCases. Mutation of any of these residues to alanine completely abolished the enzymatic activity toward GM1 (Table 3; for the raw data, see supplemental Fig. S4). The inner galactose unit formed hydrogen bonds with Lys61, Tyr302, and Trp365. Both Lys61 and Trp365 are conserved among EGCases, and mutating them to alanine resulted in a dramatic loss of enzymatic activity (Table 3). Notably, the sialic acid unit showed a remarkable difference in conformations between the GM1 and GM3 complex (Fig. 4C). In the GM3 complex, the sialic acid unit directly interacted with the inner galactose, whereas in the GM1 complex, it interacted with the N-acetylglucosamine residue. In the 103S_EGCase I-GM1 complex, Asp62 formed a hydrogen bond with the N-acetylglucosamine unit of GM1. However, the D62A mutant still retained ∼70% of the normal activity, suggesting that Asp62 contributes little to catalysis. The terminal galactose unit of GM1 did not directly interact with the protein; instead, its interaction with Asp342 was mediated by a water molecule.

TABLE 3.

Specific activities of wild-type 103S_EGCase I and its mutants

Representative HPLC chromatograms of the specific activity assay are presented in supplemental Fig. S4.

| 103S_EGCase I mutant | GM1 |

LacCer |

Interacting sugar units | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific activity | Relative activity | Specific activity | Relative activity | ||

| nmol/min/μg | % | nmol/min/μg | % | ||

| WT | 7.59 ± 0.23 | 100 | 1.92 ± 0.17 | 0 | |

| K61A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Glc (O3), Gala (O4, O6) |

| D62A | 5.46 ± 0.09 | 71.9 | 1.61 ± 0.03 | 83.9 | GalNAc (O4) |

| H131A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Glc (O3) |

| D133A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Glc (O2, O3) |

| N213A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Glc (O2) |

| N265A | 0 | 0 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 2.1 | Sphingosine(OH) |

| Q298A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Glc (O6), Fatty acid (O) |

| Y302A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Glc (O6), Gala (O2) |

| E339S | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Glc(O2) |

| D342A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NeuAc (O4) |

| W365A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Gala (O2) |

a The inner Gal unit in the GM1 sugar chain.

Interestingly, although Asp342 is not a conserved residue in EGCase family, mutation of this residue caused a dramatic loss of activity, suggesting that it has an important role in catalysis. This residue was mutated to several other amino acids to better understand its potential function. Mutation of Asp342 with Asn or Gln caused the enzyme to retain very low activity, whereas the other mutations completely abolished the enzymatic activity (supplemental Table S2). Because the mutations caused a loss of the enzymatic activities toward GM1 and LacCer, the interaction between Asp342 and the sialic acid unit did not contribute to the loss of activity. We inferred that Asp342 might stabilize the conformation of the “cap,” which might be important for catalysis, because it formed a hydrogen bond with the cap-forming amino acid, Tyr302, located in the α7-helix (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of the active site pockets of 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II. A, Phe162, Pro163, Leu164, Tyr302, and Leu303 in 103S_EGCase I form a large cap over the active site. Lys61, Asp133, Phe162, Tyr302, Asp342, and Trp365 form a small opening for the active site pocket. B, Arg177 and Asp311 in M777_EGCase II form a small cap over the active site. Lys66, Asp137, Arg177, Trp178, Asp311, Asp314, Asp355, Leu358, Trp382, and Trp389 in M777_EGCase II form a large opening for the active site pocket. C, loop 2 and the short loop 4 of 103S_EGCase I define a broad sugar-binding cavity. The model of fucosyl-GM1 in the binding site was created by superimposing its structure onto GM1 and then adjusting the fucosyl unit to a reasonable conformation using Coot. The small pocket was able to accommodate the fucosyl unit. D, loop 2 and the long loop 4 of M777_EGCase II define a crowded sugar-binding cavity.

The ceramide moieties of GM1 and GM3 were only partially defined in the electron density map. Asn265 and Gln298 directly interacted with ceramide. Both residues are conserved among EGCases and important for catalysis (Table 3). The ceramide-binding channel was lined by the hydrophobic side chains of Phe162, Pro163, Leu167, Trp216, Phe225, Val262, Ile295, and Leu299.

The Substrate Recognition Mechanism and Molecular Engineering Guided by Structural Comparisons

The main difference between EGCase I and EGCase II was their substrate specificity toward oligosaccharide moieties. EGCase I efficiently hydrolyzes fucosyl-GM1 and globo-series GSLs that are resistant to EGCase II. The resolution of the 103S_EGCase I-GM1 structure (PDB code 5J7Z) enabled us to perform a detailed comparison of its structure with the structure of M777_EGGase II-GM3 (PDB code 2OSX). The superposition of 5J7Z and 2OSX monomers using Chimera gave an r.m.s.d. of 1.09 Å between 239 atom pairs. As shown in Fig. 5A, although the overall structure of 103S_EGCase I was similar to that of M777_EGCase II, it showed several major structural differences in the oligosaccharide-binding cavity.

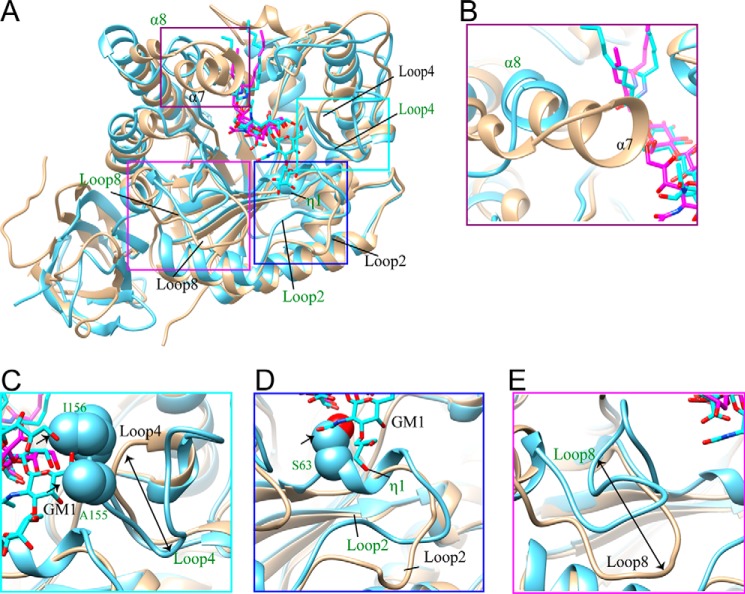

FIGURE 5.

Major structural differences in the sugar-binding sites of 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II. A, the structures of 103S_EGCase I (tan) and M777_EGCase II (light blue) are superimposed, and the differences are highlighted with boxes. B, the α7-helix of 103S_EGCase I was longer than the α8-helix in M777_EGCase II. C, M777_EGCase II had a longer loop 4 than 103S_EGCase I, in which Ala155 and Ile156 may clash with GM1, as indicated by the arrow. D, the conformations of loop 2 in 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II are different, and Ser63 located in loop 2 of M777_EGCase II may clash with GM1. E, loop 8 in 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II had a large difference in conformation.

First, the α7-helix of 103S_EGCase I was longer than the equivalent α8-helix in M777_EGCase II (Fig. 5B). The Tyr302 and Leu303 residues in the α7-helix along with Phe162, Pro163, and Leu164 in loop 5 and the α6-helix formed a broad cap over the ceramide-binding channel in 103S_EGCase I, whereas the cap in M777_EGCase II formed by Arg177 and Asp311 was much smaller (Fig. 6, A and B). Therefore, the opening of the active site of 103S_EGCase I was obviously smaller than the opening of M777_EGCase II (Fig. 6, A and B), which is mainly attributed to the presence of Tyr302.

Second, loop 4 (Gly140–Pro145) in 103S_EGCase I was shorter than the corresponding loop 4 (Thr144–Pro161) in M777_EGCase II (Fig. 5C). The shorter loop increased the volume of the sugar cavity of 103S_EGCase I, which may account for its broad substrate specificity. The truncation of loop 4 in M777_EGCase II from Asn148 to Gly154 may increase the space of the crowded sugar-binding cavity (Fig. 6D), resulting in enhanced activity toward GM1 (163%) and decreased activity (46.8%) toward LacCer (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Specific activities of M777_EGCase II and its mutants toward the GM1, LacCer, and fucosyl-GM1 substrates

| EGCase II | GM1 |

LacCer |

Fucosyl-GM1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific activity | Relative activity | Specific activity | Relative activity | Specific activity | Relative activity | |

| nmol/min/μg | % | nmol/min/μg | % | nmol/min/μg | % | |

| WT | 0.223 ± 0.012 | 100 | 0.250 ± 0.010 | 100 | <0.0001 | 100 |

| S63G | 2.099 ± 0.016 | 940 | 0.228 ± 0.015 | 91.5 | 0.137 ± 0.008 | >137000 |

| Loop deletion (Asn148–Gly154) | 0.364 ± 0.009 | 163 | 0.117 ± 0.009 | 46.8 | <0.0001 | 100 |

Third, the conformation of loop 2 was different in the two enzymes. Loop 2 in 103S_EGCase I (Val59–Thr73) was more open than loop 2 in M777_EGCase II (Ala62–Thr76) (Fig. 5D). Consequently, 103S_EGCase I possessed a larger sugar-binding pocket, which could accommodate the fucosyl unit of fucosyl-GM1 (Fig. 6C). By contrast, loop 2 in M777_EGCase II was disrupted by a short η1-helix (63SSAK66), and thus it adopted a conformation that was closer to that of the substrate (Fig. 5D). The superimposition of the crystal structures of 103S_EGCase I-GM1 and M777_EGCase II clearly showed that the inclusion of Ser63 in M777_EGCase II resulted in a narrowed sugar-binding cavity, which may also cause its strict specificity. Indeed, the S63G mutant of M777_EGCase II efficiently hydrolyzed fucosyl-GM1, with its catalytic activity increasing more than 1370-fold. Moreover, its activity toward GM1 was also enhanced by ∼10-fold (Table 4).

Finally, loop 8 also showed a large difference in conformations between 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II (Fig. 5E). Compared with M777_EGCase II, loop 8 of 103S_EGCase I moved outward ∼13 Å and was flatter, which also contributed to the enlarged sugar-binding cavity.

Discussion

EGCases are a group of glycoside hydrolases that are important in cellular glycosphingolipid-glycome analyses. In this study, we identified a new 103S_EGCase I from R. equi 103S that hydrolyzes ganglio-, lacto-, and globo-series GSLs, as well as fucosyl-GM1. Remarkably, 103S_EGCase I can be readily overexpressed in E. coli at a very high level (80 mg/liter purified protein, 12 h of induction), which is much higher than the previously reported expression of M750_EGCase I in the Rhodococcus system (∼1 mg/liter, 24 h of induction). The broad substrate specificity, high catalytic activity, and ease of expression make 103S_EGCase I a good biocatalyst for cellular glycomics analysis of GSLs.

The GH5 family is one of the largest GH families, containing >6900 protein sequences with ∼20 different enzyme activities (17). Previously, the EGCases were divided into the GH5_12, GH5_27, GH5_28, and GH5_29 subfamilies. A phylogenetic analysis was conducted in this study, and the results suggested that EGCase I genes belong to a new subfamily within the GH5 family. We obtained the first crystal structure of a member of this new subfamily, which may provide new insights into the mechanism of the substrate selectivity of EGCases.

Based on the detailed structural comparison, 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II exhibit several major structural differences in their sugar-binding cavities, which explains their different substrate specificities. First, the α7-helix of 103S_EGCase I is longer than the equivalent α8-helix in M777_EGCase II, forming a larger cap over the glycosidic bond. Second, the flexible loop 4 between η1 and η2 is shorter than the corresponding loop in M777_EGCase II. The loop 4 may play a role in the substrate selectivity of EGCases. For larger substrates, such as GM1, the activity may be inhibited by the space limitation arising from the long loop 4 in M777_EGCase II, but for smaller substrates, such as LacCer, the loop may stabilize the substrates in the active site and efficiently facilitate catalysis. Third, loop 2 of 103S_EGCase I adopts an open conformation compared with the closed conformation in M777_EGCase II, producing a smaller sugar-binding pocket that cannot accommodate more extended oligosaccharides. Presumably, the size of this pocket is the reason why M777_EGCase II cannot hydrolyze fucosyl-GM1. Finally, loop 8 of 103S_EGCase I moved outward and flattened, which could also enlarge the oligosaccharide-binding cavity.

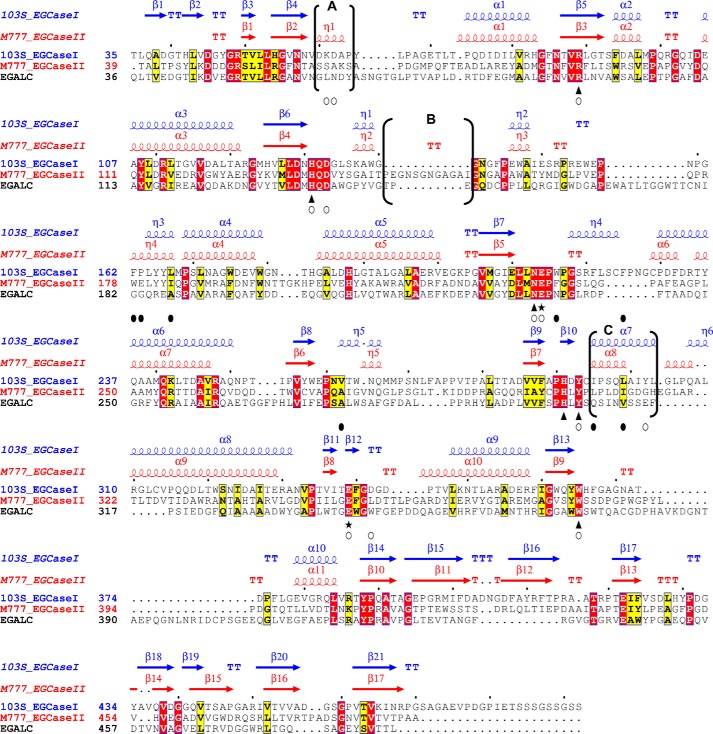

This structural information enabled us to identify a series of conserved amino acids that are important for substrate binding in 103S_EGCase I. The residues that interact with the first two sugar residues (Glu and Gal) are highly conserved in 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II and include Lys61, His131, Asp133, Asn213, Glu214, Gln298, and Trp365. By contrast, the outer sugar subunits have few interactions with the enzyme; the sialic acid unit of GM1 only interacts with Asp342 through a water molecule. A structure-based sequence alignment of EGCases revealed several regions with low sequence identity. In particular, the main structural differences mentioned above are located in unconserved regions A, B, and C, which may play key roles in determining substrate specificity (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Structure-based sequence alignment of 103S_EGCase I, M777_EGCase II and EGALC. The amino acid sequences of 103S_EGCase I (GenBankTM accession number CBH49814), M777_EGCase II (GenBankTM accession number AAB67050), and EGALC (GenBankTM accession number BAF56440) were aligned using PROMALS3D and shaded in ESPript 3.0. Identical residues are shown in open boxes with white letters on a red background. Similar residues are shown in open boxes with black letters on a yellow background. Conserved amino acid residues in the GH5 family of glycosidases are indicated by triangles. Two glutamates, functioning as an acid/base catalyst and nucleophile, respectively, are indicated by stars. Residues that form hydrogen bonds or hydrophobic interactions with the sugar moiety are indicated by empty circles. Residues that form the hydrophobic tunnel are indicated by black filled circles. The secondary structural elements are shown above the amino acid residues in blue (103S_EGCase I, PDB code 5J7Z) and red (M777_EGCase II, PDB code 2OSX). The major differences in the secondary structures of 103S_EGCase I and M777_II are indicated in brackets and marked as regions A, B, and C.

These analyses provided valuable information for engineering the EGCase protein. As shown in the study by Ishibashi et al. (15), the deletion of loop 4 (residues Asn148–Gly154) from M777_EGCase II increased its catalytic activity toward GM1. In this study, the resolution of the 103S_EGCase I crystal structure revealed that loop 4 in 103S_EGCase I is obviously shorter than the corresponding loop in M777_EGCase II. The superposition of the 103S_EGCase I-GM1 complex with the M777_EGCase II-GM3 structure suggested that the long loop 4 in M777_EGCase II might hamper the binding of GM1, which provides a structural explanation for the enhanced activity of its loop 4-deleted mutant. Loop 2 is another important region that differs in the structures of the two enzymes. Ser63 in M777_EGCase II appeared to be too close to the GalNAc residue in GM1. Indeed, the S63G mutation resulted in an activity enhancement of about 10-fold toward GM1 and at least 1370-fold toward the fucosyl-GM1, implying that this mutation eliminates the steric hindrance and enlarges the sugar-binding pocket. More detailed analyses of this structure information may be helpful for further protein engineering of EGCases.

In conclusion, the biochemical and structural analyses in this study illustrate the structural basis of the substrate selectivity of EGCases. The broad specificity, high reaction efficiency, and ease of expression of 103S_EGCase I make it the best enzyme reported to date for use in the cellular glycomics analysis of GSLs. The structural knowledge obtained in this study revealed several regions that may be important for the substrate recognition of this enzyme class, providing possibilities for the rational design of these enzymes.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

GlcCer, GalCer, and LacCer were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). GM3, Gb4Cer, and fucosyl-GM1 were purchased from Carbosynth Co., Ltd. (Berkshire, UK). GM1 was purchased from Qilu Pharmaceutical (Jinan, China). 2-Aminobenzoic acid (2-AA) was purchased from Aladdin Industries Corp. (Shanghai, China). GM3, GM1, fucosyl-GM1, and Gb4Cer oligosaccharides were purchased from Elicityl Co., Ltd. (Crolles, France). HPLC solvents were purchased from Anpel Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All other reagents were of the highest purity available.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Twenty-one members of the GH5_12, GH5_27, GH5_28, and GH5_29 subfamilies, with at least five members in each subfamily, were selected from the CAZy database. The protein sequences sharing >50% sequence identity with EGCase I from Rhodococcus sp. M-750 were collected by a BLAST search of the NCBI non-redundant protein sequence database. The sequences of the EGCases and EGCase-related proteins were aligned using ClustalX. Evolutionary analyses were conducted and visualized in MEGA6 (28). The phylogenetic tree of the EGCases was constructed using the maximum likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model with 100 bootstrap replications.

Protein Expression and Purification

The gene encoding the mature EGCase I from R. equi 103S, which lacks its 26-residue N-terminal secretion signal sequence, was codon-optimized for E. coli and chemically synthesized (Genscript Corp., Nanjing, China). The gene sequence was subcloned into a pET28a vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) using the BamHI/HindIII restriction sites and was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells. Transformants were grown at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg/ml kanamycin until the optical density at 600 nm reached ∼0.8. Then protein expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.1 mm at 16 °C. After 12 h, the cells were harvested and disrupted by sonication, and the enzyme was purified by Ni2+-chelating affinity chromatography to >95% purity, as determined by SDS-PAGE analysis. The protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay with BSA as the standard. The activity of EGCase I was confirmed using a thin layer chromatography (TLC) assay with the substrate GM1, as described previously (15).

Mutants of 103S_EGCase I were constructed (K61A, D62A, H131A, D133A, N213A, N265A, Q298A, Y302A, E339S, D342A, D342N, D342E, D342Q, D342F, D342Y, D342K, D342L, D342W, and W365A) using whole plasmid PCR. The mutants were purified using the same protocol as for wild-type 103S_EGCase I. Wild-type M777_EGCase II and its mutants (S63G, S64G, and Δloop (loop-deleted mutant, Asn148–Gly154)) were generated using a whole plasmid PCR protocol with the pET28a plasmid containing M777_EGCase II as the template. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells, and the expressed protein was purified as described previously (16). All the primers used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S3.

Enzymatic Assay and Kinetics

The activities of 103S_EGCase I and M777_EGCase II were measured in a standard enzymatic assay using GM1 as substrate. The reaction mixture contained 10 nmol of GM1 and an appropriate amount of enzyme in 20 μl of 50 mm sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.0) with 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100. Following an incubation at 37 °C for 10 min (103S_EGCase I) or 30 min (M777_EGCase II), the reaction was stopped by heating the mixture in a boiling water bath for 5 min to ensure that the initial velocity was measured. The generation of the GM1 oligosaccharide was measured using the HPLC-based protocol described by Neville et al. (29), with slight modifications. Briefly, a 20-μl sample of the reaction mixture was mixed with 100 μl of the 2-AA solution in 1.6-ml polypropylene screw cap freeze vials. The vials were capped tightly and heated at 80 °C for 45 min for derivatization. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm, the supernatant was transferred into a glass vial, and an aliquot (10 μl) was injected into a 4.6 × 250-mm TSK gel-Amide 80 column (4.6-mm inner diameter × 250 mm, 5-μm particle size). Solvent system A consisted of 5% acetic acid and 3% triethylamine in water, and solvent system B consisted of 2% acetic acid in acetonitrile. The following gradient conditions were used: 30% A isocratic for 5 min followed by a linear increase to 70% A over 1 min, holding at 70% A for an additional 4 min, and then a linear decrease to 30% A over 3 min. The 2-AA-derivatized product was detected using a fluorescence detector (Agilent 1260 FLD, Eex = 360 nm, Eem = 425 nm) and quantified using a standard curve.

The substrate specificity of EGCase was presented as the specific activity toward different substrates using 10 ng of 103S_EGCase I or 100 ng of M777_EGCase II in a standard enzymatic assay. Substrate specificity was also presented as the reaction yield (percentage) for different substrates after a 24-h reaction in the presence of a sufficient concentration of enzyme. The HPLC method used to detect the oligosaccharides after 2-AA derivatization was similar to the method used for the GM1 oligosaccharides, except that the mobile phase ratio of A/B was adjusted according to the polarity of the released oligosaccharides (supplemental Fig. S2). For the kinetic analysis, 103S_EGCase I (10 ng) was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min in 20 μl of reaction buffer. M777_EGCase II (100 ng) was assayed at 37 °C for 30 min in 20 μl of reaction buffer. The concentrations of the substrates ranged from 10 to 2000 μm. The parameters Km and kcat were obtained by fitting the experimental data to the Michaelis-Menten kinetics model using GraphPad Prism version 5 software.

Crystallization

Crystallization experiments were conducted in 48-well plates using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 293 K, and each hanging drop was prepared by mixing 1 μl each of protein solution and reservoir solution. Initial crystallization trials yielded some small crystals from the PEG/ION crystallization screen (Hampton Research). Crystal quality was improved by the MMS method (30), and the seed stock was generated from the initial crystals. Ultimately, diffraction quality crystals were grown in hanging drops at 21 °C by mixing 1 μl of protein (16 mg/ml in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 200 mm NaCl) with an equal volume of 0.2 m lithium nitrate and 20% PEG 3350. Crystals belonged to the space group C121, with the unit cell dimensions a = 192.8 Å, b = 48.9 Å, c = 120.3 Å, and β = 114.3°. Complex crystals were obtained by co-crystallizing the E339S mutant with GM1 or GM3. The GM1 or GM3 substrate was dissolved in the protein solution to a final concentration of 10 mm for 2 h at 4 °C before proceeding with the hanging drop crystallization experiments described above.

Data Collection and Structure Determination

For X-ray diffraction experiments, crystals were removed from the crystallization drop with a nylon loop, soaked briefly in a cryoprotectant solution of the crystallization solution supplemented with 30% (v/v) ethylene glycol, and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data sets were collected on the BL17U and BL19U beamlines at the Shanghai Synchrotron Research Facility. All diffraction data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using HKL-2000 (31).

Initial phases for each structure were determined by molecular replacement. The structure of 103S_EGCase I was solved using the program BALBES (32) with the Auto-RICSHAW pipeline (33). The structure was completed with alternating rounds of manual model building with Coot (34) and refinement with REFMAC5 (35) in the CCP4 suite (36). The structure of the 103S_EGCase I-substrate complex was determined by molecular replacement with the program MOLREP (37) using the 103S_EGCase I structure as a search model. The structures of GM1 and GM3 were built with Coot Ligand Builder, and restraints were created using PRODRG (38). Iterative model building was performed in Coot, and refinement was conducted with REFMAC5 in the CCP4 suite. The final models were validated using MolProbity (39). Data collection and refinement statistics are provided in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameters | Native | 103S_EGCase I-GM1 | 103S_EGCase I-GM3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | C121 | C121 | C121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 192.84, 48.98, 120.30 | 192.28, 48.92, 120.23 | 192.52, 49.05, 120.14 |

| α, β, γ (degrees) | 90.00, 114.30, 90.00 | 90.00, 113.95, 90.00 | 90.00, 114.19, 90.00 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.979 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.11 (2.18–2.11)a | 50–2.15 (2.23–2.15) | 50–1.915 (1.97–1.915) |

| Rmerge | 0.127 (0.493) | 0.118 (0.486) | 0.123 (0.425) |

| I/σ(I) | 10.09 (3.10) | 14.7 (5.11) | 11.03 (4.19) |

| No. of unique observations | 58,536 (5742) | 55,310 (5441) | 79,432 (5959) |

| No. of total observations | 59,788 | 55,996 | 79,632 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.4 (97.5) | 99.2 (98.6) | 97.4 (74.2) |

| Redundancy | 4.2 (4.3) | 4.2 (4.1) | 4.2 (4.0) |

| Refinement | |||

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 0.194/0.223 | 0.176/0.209 | 0.172/0.208 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 21.8 | 24.9 | 12.74 |

| Ligand | 33.9 | 27.9 | 22.39 |

| Water | 31.4 | 31.0 | 21 |

| r.m.s.d. | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.0109 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.073 | 1.458 | 1.479 |

| PDB entry | 5CCU | 5J7Z | 5J14 |

a Data for the highest resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Structural Analysis

Searches for similar structures were performed using the DALI server (21). Structure-based sequence alignments were generated with PROMALS3D (40). The alignments were shaded in ESPript version 3.0 (41). Fucosyl-GM1 was modeled in the binding site by superimposing the structure on GM1, and the fucosyl unit was adjusted to a reasonable conformation in Coot. Figures were prepared using Chimera (42).

Author Contributions

Y.-B. H. conducted most of the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote most of the paper. L.-Q. C. purified and crystallized 103S_EGCase I protein, determined its X-ray structure, and contributed to the preparation of the figures. Z. L. participated in the characterization of EGCases. Y.-M. T. participated in the construction of EGCase mutants. G.-Y. Y. and Y. F. conceived the idea for the project, designed the experiment, and analyzed the data. Y.-B. H., L.-Q. C., and G.-Y. Y. wrote the paper. All authors analyzed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staffs of beamlines BL19U1 and 17U at the National Center for Protein Sciences Shanghai and Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for assistance in data collection. We also thank the Instrument and Service Center of the School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, for equipment service.

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, 2012CB721003) and Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31470788 and 11371142. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 5CCU, 5J7Z, and 5J14) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S4.

- GSL

- glycosphingolipid

- EGCase

- endoglycoceramidase

- EGALC

- endogalactosylceramidase

- GM3

- monosialodihexosylganglioside

- GM1

- monosialotetrahexosylganglioside

- LacCer

- lactosylceramide

- GlcCer

- glucosylceramide

- GalCer

- galactosylceramide

- Gb4Cer

- globotetraosylceramide

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- GH

- glycoside hydrolase

- TLC

- thin layer chromatography.

References

- 1. Fujitani N., Takegawa Y., Ishibashi Y., Araki K., Furukawa J., Mitsutake S., Igarashi Y., Ito M., and Shinohara Y. (2011) Qualitative and quantitative cellular glycomics of glycosphingolipids based on rhodococcal endoglycosylceramidase-assisted glycan cleavage, glycoblotting-assisted sample preparation, and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization tandem time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 41669–41679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Furukawa J., Sakai S., Yokota I., Okada K., Hanamatsu H., Kobayashi T., Yoshida Y., Higashino K., Tamura T., Igarashi Y., and Shinohara Y. (2015) Quantitative GSL-glycome analysis of human whole serum based on an EGCase digestion and glycoblotting method. J. Lipid Res. 56, 2399–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ito M., and Yamagata T. (1986) A novel glycosphingolipid-degrading enzyme cleaves the linkage between the oligosaccharide and ceramide of neutral and acidic glycosphingolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 14278–14282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ashida H., Yamamoto K., Kumagai H., and Tochikura T. (1992) Purification and characterization of membrane-bound endoglycoceramidase from Corynebacterium sp. Eur. J. Biochem. 205, 729–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li S.-C., DeGasperi R., Muldrey J. E., and Li Y.-T. (1986) A unique glycosphingolipid-splitting enzyme (ceramide-glycanase from leech) cleaves the linkage between the oligosaccharide and the ceramide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 141, 346–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li Y.-T., Ishikawa Y., and Li S.-C. (1987) Occurrence of ceramide-glycanase in the earthworm, Lumbricusterrestris. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 149, 167–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Basu S. S., Dastgheib-Hosseini S., Hoover G., Li Z., and Basu S. (1994) Analysis of glycosphingolipids by fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis using ceramide glycanase from Mercenaria mercenaria. Anal. Biochem. 222, 270–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Horibata Y., Okino N., Ichinose S., Omori A., and Ito M. (2000) Purification, characterization, and cDNA cloning of a novel acidic endoglycoceramidase from the jellyfish, Cyanea nozakii. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31297–31304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horibata Y., Sakaguchi K., Okino N., Iida H., Inagaki M., Fujisawa T., Hama Y., and Ito M. (2004) Unique catabolic pathway of glycosphingolipids in a hydrozoan, Hydra magnipapillata, involving endoglycoceramidase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33379–33389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ishibashi Y., Ikeda K., Sakaguchi K., Okino N., Taguchi R., and Ito M. (2012) Quality control of fungus-specific glucosylceramide in Cryptococcus neoformans by endoglycoceramidase-related protein 1 (EGCrP1). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 368–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Watanabe T., Ito T., Goda H. M., Ishibashi Y., Miyamoto T., Ikeda K., Taguchi R., Okino N., and Ito M. (2015) Sterylglucoside catabolism in Cryptococcus neoformans with endoglycoceramidase-related protein 2 (EGCrP2), the first steryl-β-glucosidase identified in fungi. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 1005–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ito M., and Yamagata T. (1989) Purification and characterization of glycosphingolipid-specific endoglycosidases (endoglycoceramidases) from a mutant strain of Rhodococcus sp.: evidence for three molecular species of endoglycoceramidase with different specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 9510–9519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ishibashi Y., Nakasone T., Kiyohara M., Horibata Y., Sakaguchi K., Hijikata A., Ichinose S., Omori A., Yasui Y., Imamura A., Ishida H., Kiso M., Okino N., and Ito M. (2007) A novel endoglycoceramidase hydrolyzes oligogalactosylceramides to produce galactooligosaccharides and ceramides. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11386–11396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Izu H., Izumi Y., Kurome Y., Sano M., Kondo A., Kato I., and Ito M. (1997) Molecular cloning, expression, and sequence analysis of the endoglycoceramidase II gene from Rhodococcus species strain M-777. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 19846–19850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ishibashi Y., Kobayashi U., Hijikata A., Sakaguchi K., Goda H. M., Tamura T., Okino N., and Ito M. (2012) Preparation and characterization of EGCase I, applicable to the comprehensive analysis of GSLs, using a rhodococcal expression system. J. Lipid Res. 53, 2242–2251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Caines M. E. C., Vaughan M. D., Tarling C. A., Hancock S. M., Warren R. A. J., Withers S. G., and Strynadka N. C. J. (2007) Structural and mechanistic analyses of endo-glycoceramidase II, a membrane-associated family 5 glycosidase in the apo and GM3 ganglioside-bound forms. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14300–14308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aspeborg H., Coutinho P. M., Wang Y., Brumer H. 3rd, and Henrissat B. (2012) Evolution, substrate specificity and subfamily classification of glycoside hydrolase family 5 (GH5). BMC Evol. Biol. 12, 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krissinel E., and Henrick K. (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bahadur R. P., Chakrabarti P., Rodier F., and Janin J. (2004) A dissection of specific and non-specific protein-protein interfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 336, 943–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhu H., Domingues F. S., Sommer I., and Lengauer T. (2006) NOXclass: prediction of protein-protein interaction types. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holm L., and Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhou P., Liu Y., Yan Q., Chen Z., Qin Z., and Jiang Z. (2014) Structural insights into the substrate specificity and transglycosylation activity of a fungal glycoside hydrolase family 5 β-mannosidase. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 2970–2982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dias F. M. V., Vincent F., Pell G., Prates J. A. M., Centeno M. S. J., Tailford L. E., Ferreira L. M. A., Fontes C. M. G. A., Davies G. J., and Gilbert H. J. (2004) Insights into the molecular determinants of substrate specificity in glycoside hydrolase family 5 revealed by the crystal structure and kinetics of Cellvibrio mixtus mannosidase 5A. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25517–25526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boraston A. B., Bolam D. N., Gilbert H. J., and Davies G. J. (2004) Carbohydrate-binding modules: fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem. J. 382, 769–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larsbrink J., Rogers T. E., Hemsworth G. R., McKee L. S., Tauzin A. S., Spadiut O., Klinter S., Pudlo N. A., Urs K., Koropatkin N. M., Creagh A. L., Haynes C. A., Kelly A. G., Cederholm S. N., Davies G. J., et al. (2014) A discrete genetic locus confers xyloglucan metabolism in select human gut Bacteroidetes. Nature 506, 498–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Venditto I., Najmudin S., Luís A. S., Ferreira L. M. A., Sakka K., Knox J. P., Gilbert H. J., Fontes C. M. G. A.. (2015) Family 46 carbohydrate-binding modules contribute to the enzymatic hydrolysis of xyloglucan and β-1,3–1,4-glucans through distinct mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 10572–10586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Correia M. A. S., Mazumder K., Brás J. L. A., Firbank S. J., Zhu Y., Lewis R. J., York W. S., Fontes C. M. G. A., and Gilbert H. J. (2011) Structure and function of an arabinoxylan-specific xylanase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 22510–22520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., and Kumar S. (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neville D. C. A., Coquard V., Priestman D. A., te Vruchte D. J. M., Sillence D. J., Dwek R. A., Platt F. M., and Butters T. D. (2004) Analysis of fluorescently labeled glycosphingolipid-derived oligosaccharides following ceramide glycanase digestion and anthranilic acid labeling. Anal. Biochem. 331, 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. D'Arcy A., Bergfors T., Cowan-Jacob S. W., and Marsh M. (2014) Microseed matrix screening for optimization in protein crystallization: what have we learned? Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 70, 1117–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minor W., and Otwinowski Z. (1997) HKL2000 (Denzo-SMN) Software Package. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Long F., Vagin A. A., Young P., and Murshudov G. N. (2008) BALBES: a molecular-replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Panjikar S., Parthasarathy V., Lamzin V. S., Weiss M. S., and Tucker P. A. (2005) Auto-Rickshaw: an automated crystal structure determination platform as an efficient tool for the validation of an X-ray diffraction experiment. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 61, 449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Emsley P., and Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murshudov G. N., Skubák P., Lebedev A. A., Pannu N. S., Steiner R. A., Nicholls R. A., Winn M. D., Long F., and Vagin A. A. (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 355–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., et al. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vagin A., and Teplyakov A. (1997) MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30, 1022–1025 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schüttelkopf A. W., and van Aalten D. M. (2004) PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 1355–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., and Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pei J., Kim B.-H., and Grishin N. V. (2008) PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2295–2300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Robert X., and Gouet P. (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., and Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kyte J., and Doolittle R. F. (1982) A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157, 105–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.