CASE

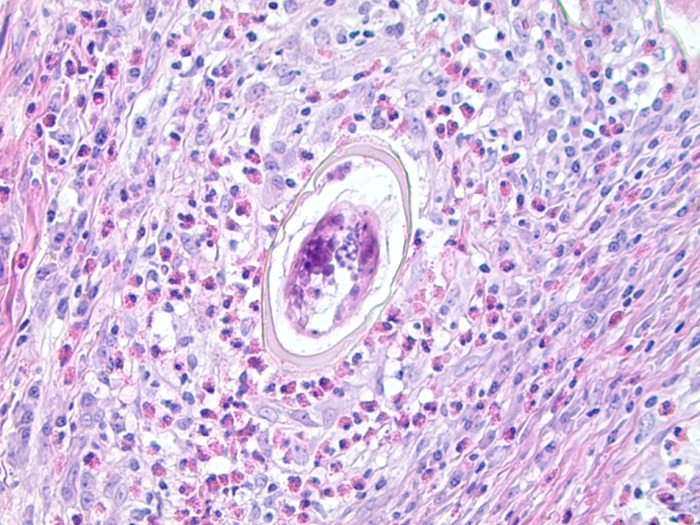

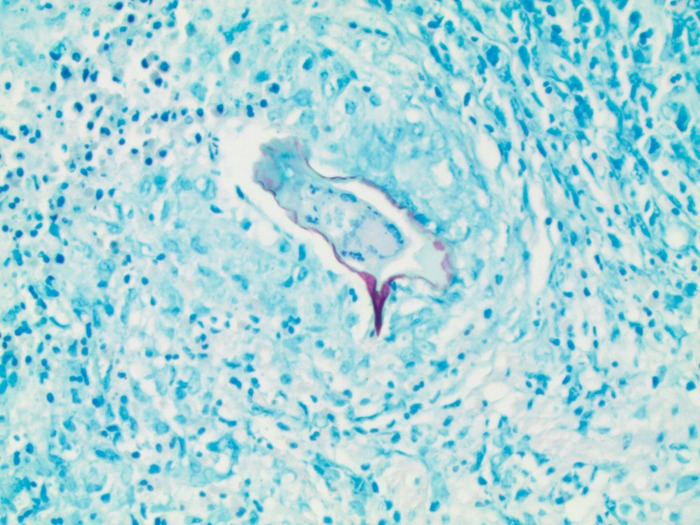

We report a case of a 40-year-old female of Yemeni background who presented with abdominal pain. The pain started 14 months prior and was localized to the epigastrium, was precipitated by eating, and was of a burning and itching type. The pain occurred every 2 to 3 days, lasted for several minutes, and was associated with intermittent nausea. She occasionally had dysphagia with solid foods, but this did not interfere with her daily activities. There was no history of constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, or blood in the stool. There was no history of recent travel, and she had not been clinically evaluated since her last visit to Yemen. Her family history was significant for gastric and colon cancers. Physical examination was negative for abdominal or rebound tenderness. Although her complete blood counts were within normal reference ranges, she did have a history of microscopic hematuria. No stool or urine microscopic examination was performed. The differential diagnosis at that time included gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, and cholelithiasis. Ultrasound of the abdomen was unremarkable, and the patient was started on a trial of proton pump inhibitors for 1 month. She was also followed up by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, as well as a screening colonoscopy because of the family history of colon cancer. Endoscopy showed a patchy area of mild nonerosive gastritis involving the antrum and the body of the stomach. On histology, the gastric biopsy specimen showed chronic active gastritis and was positive for Helicobacter pylori by immunohistochemistry. From the rectum, we obtained a single biopsy specimen of a 1-cm, nonbleeding, semipedunculated polyp, which was completely removed by snare cautery. The histologic sections showed benign polypoid colonic mucosa with submucosal granulomatous inflammation, giant cells, and abundant eosinophils. At the center of many of the granulomas were eggs in various orientations, measuring roughly 130 by 60 μm (Fig. 1). The shells of the eggs were positive for Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain, and in one section, a large lateral spine was visible (Fig. 2). The features of the tissue reaction, the morphology of the eggs, and the positive Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast staining were consistent with Schistosoma mansoni. No serological correlation was performed. The patient received praziquantel three times daily for 2 days for schistosomiasis and amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and proton pump inhibitors for 14 days for H. pylori-associated gastritis.

FIG 1.

Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained section of the rectal polyp with an S. mansoni egg in the center of a granuloma.

FIG 2.

Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain showing an S. mansoni egg staining acid fast positive.

DISCUSSION

Blood flukes (trematodes in the family Schistosomatidae) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although uncommon in the United States, schistosomiasis (bilharziasis or snail fever) is one of the top three tropical diseases in the world (following malaria and intestinal helminthiasis), more commonly seen in the developing countries of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East (1). According to the World Health Organization, more than 61.6 million people were reported to have been treated for schistosomiasis in 2014, in comparison to the 258 million needing preventive treatment (1). The most common species are S. haematobium, S. mansoni, and S. japonicum. S. haematobium usually causes urogenital symptoms, whereas the latter two are usually associated with, but not limited to, the intestinal form of the disease (1). S. haematobium was first discovered in the mid-1800s by a German surgeon, Theodore Bilharz, in Cairo. The parasite develops in freshwater snails (intermediate host), eventually releasing cercariae into the surrounding body of water. Humans acquire the disease when these cercariae enter through intact skin, which can cause mild dermatitis presenting as a sensation of tingling or a pruritic rash (Katayama fever) (2). Once the human host is infected, the cercariae shed the forked tail to form schistosomula. These disseminate hematogenously to different tissues, evolving into the adult worms that eventually reside in the venous plexuses of the mesentery, the urinary bladder, or both, depending upon the species (see below). The eggs laid within these venules lodge within the surrounding tissues and evoke a granulomatous host response. The eggs of S. haematobium lodge in the bladder wall and organs of the genital tract, while the eggs of the other species lodge in the intestinal wall or are passively transported to the liver via the portal circulation. In the bladder or intestine, the host immune response helps push the eggs toward the visceral lumen to be eliminated with feces or urine. The eggs hatch upon exposure to freshwater, releasing the miracidia, which then penetrate an appropriate snail host to repeat the cycle (1). Because of the nature of disease transmission, it tends to affect individuals living in the tropics and subtropics, with significant associated morbidity and significant subsequent economic hardships. For this reason, schistosomiasis is considered a neglected tropical disease (1). Interestingly, Schistosome eggs have been found in Egyptian mummies and the disease has been described in papyrus records, indicating that this is a “disease of antiquity” (3).

Intestinal schistosomiasis is usually caused by S. mansoni, S. japonicum, S. mekongi, or S. guineensis and rarely by S. haematobium (4). Intestinal polyposis in cases of schistosomiasis has previously been reported and is usually due to S. mansoni and rarely due to S. japonicum or S. haematobium (1, 2, 4). The number of polyps can range from one to several hundred (2). Signs and symptoms are secondary to the host immune response and vary depending on the organ system affected. Intestinal schistosomiasis may be asymptomatic or cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia. Similarly, urinary bladder involvement may be asymptomatic or cause microscopic or frank hematuria and infertility. Schistosoma eggs in the portal venules of the liver can lead to periportal fibrosis and eventually hepatic cirrhosis. Chronic infestation can lead to multiorgan dysfunction, affecting the brain, spleen, lungs, and bladder. If left untreated, schistosomiasis can persist for years (1) and systemic involvement can be found in advanced cases. Chronic bladder mucosal irritation secondary to S. haematobium has also been linked to bladder cancer (3). S. japonicum infection is considered a significant risk factor for colonic cancer in Asia, although this link has not been definitively established (5). The symptoms experienced by the patient in this case can be explained by H. pylori-associated gastritis. However, given the wide spectrum of symptoms seen with intestinal schistosomiasis, it is possible to conjecture that schistosomiasis may have contributed to her gastrointestinal symptoms as well.

In areas where schistosomiasis is endemic, diagnostic methodology usually involves direct visualization of eggs. Schistosome eggs can be detected in fecal specimens by the Kato-Katz technique (1, 2) by direct microscopic examination of sieved stool. Quantitation of the number of eggs per gram of stool is recommended by the WHO for diagnosis in areas where the prevalence of schistosomiasis is >20%. Although cost-effective, the method has low sensitivity, especially in patients with low burdens of infection. In countries where schistosomiasis is not endemic, such as the United States, the formalin-ethyl acetate stool concentration method is widely used for stool sample examination. Centrifugation separates the eggs and debris and concentrates the trematode eggs at the bottom of the tube, increasing diagnostic sensitivity. For urinary schistosomiasis, direct visualization of the eggs is the method of choice. The urine filtration method, similar to the Kato-Katz technique, is a quantitative test in which a urine specimen is passed through a filter to collect the eggs. This is followed by staining of the filtrate to identify and quantitate the number the eggs per 10 ml of urine. Midday urine collection is recommended, as the burden of eggs in the urine is likely to be greatest at that time. Urine samples should also be tested as soon as possible, as the eggs may hatch, releasing the miracidia. Alternatively, antibody detection methods are useful diagnostic tools, especially for individuals who have traveled to areas where schistosomiasis is endemic but microscopic diagnosis is not possible. Although they are widely available and have relatively higher sensitivity and specificity, antibody detection methods are more expensive (1, 2). A limitation of serological testing is that differentiation between current and prior infections is not possible. These tests also use a wide array of schistosomal antigens; therefore, the sensitivity and specificity of different tests are variable and not all available tests are species specific. Antigen detection methods have been developed and have a higher sensitivity and specificity, even when the parasite burden is light. These antigens can be detected in the blood during acute infection, and unlike the serological tests, they can be used to monitor treatment efficacy. However, these assays are expensive and not currently available for routine commercial use in the United States. Molecular testing via PCR has very high sensitivity and specificity but is not in routine use. Schistosome eggs can also be visualized in histologic sections from the rectum, colon, and small intestine in the setting of intestinal schistosomiasis. The histopathology characteristically demonstrates granulomas surrounding the eggs. Additionally, Ziehl-Neelsen staining of sections of a biopsy tissue specimen can be performed to determine the species, especially if its morphology is vague. The shells of S. mansoni, S. intercalatum, and S. japonicum eggs stain positive with Ziehl-Neelsen stain, unlike the eggs of other Schistosoma species. This is not widely done, as most pathologists are satisfied with morphology and a complete history.

Colonoscopic findings in intestinal schistosomiasis can be nonspecific. In our case, schistosomiasis was not considered in the differential diagnosis, clinically or even after colonoscopy. A case study in 2010 showed a wide spectrum of colonoscopic findings ranging from congested mucosa and petechial hemorrhage in acute schistosomal colitis and flat or elevated yellow nodules, polyps, and intestinal stricture in chronic schistosomal colitis (6). That study also showed that the polyps were more commonly found in the rectum (37%). In our case, no stool examination for parasitic eggs or serological test was carried out. A definitive diagnosis was made only on the basis of the histologic findings on the rectal polyp.

We report an incidental finding of schistosomiasis that was discovered in a rectal polyp. While intestinal involvement is common in schistosomiasis, colon polyps are rarely reported, especially in young people (2). While laboratory tests such as the Kato-Katz technique on stool can be diagnostic, clinical symptoms and endoscopic features are often nonspecific and therefore appropriate diagnostic tests are often not requested. In our case, the histopathologic findings were able to provide the correct diagnosis.

SELF-ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS

- Which species of Schistosoma does not stain acid fast positive?

-

A.S. haematobium.

-

B.S. mansoni.

-

C.S. japonicum.

-

D.S. intercalatum.

-

A.

- What is the mode of transmission of Schistosoma infection in humans?

-

A.Arthropod bite.

-

B.Ingestion of larvae in infected meat.

-

C.Fecal-oral transmission.

-

D.Entry through the skin.

-

A.

- Which commercially available test in the United States is most sensitive and specific in diagnosing Schistosoma infection?

-

A.The Kato-Katz technique.

-

B.Antibody detection.

-

C.Genotype analysis.

-

D.Antigen detection.

-

A.

For answers to the self-assessment questions and take-home points, see page 1226 in this issue (https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01454-16).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2016. Schistosomiasis, fact sheet no 115. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en/ Accessed 28 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Issa I, Osman M, Aftimos G. 2014. Schistosomiasis manifesting as a colon polyp: a case report. J Med Case Rep 8:331. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mostafa MH, Sheweita SA, O'Connor PJ. 1999. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev 12:97–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chassot CA, Christiano CG, Barros MS, Rodrigues CJ, Corbett CE. 1998. Colon polyps in Schistosoma haematobium schistosomiasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1:289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yosry A. 2006. Schistosomiasis and neoplasia. Contrib Microbiol 13:81–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao J, Liu WJ, Xu XY, Zou XP. 2010. Endoscopic findings and clinicopathologic characteristics of colonic schistosomiasis: a report of 46 cases. World J Gastroenterol 16:723–727. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i6.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]