Abstract

Chikungunya fever is an arboviral infection caused by the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) and is transmitted by Aedes mosquito. The envelope protein (E2) of Chikungunya virus is involved in attachment of virion with the host cell. The present study was conceptualized to determine the structure of E2 protein of CHIKV and to identify the potential viral entry inhibitors. The secondary and tertiary structure of E2 protein was determined using bioinformatics tools. The mutational analysis of the E2 protein suggested that mutations may stabilize or de-stabilize the structure which may affect the structure–function relationship. In silico screening of various compounds from different databases identified two lead molecules i.e. phenothiazine and bafilomycin. Molecular docking and MD simulation studies of the E2 protein and compound complexes was carried out. This analysis revealed that bafilomycin has high docking score and thus high binding affinity with E2 protein suggesting stable protein–ligand interaction. Further, MD simulations suggested that both the compounds were stabilizing E2 protein. Thus, bafilomycin and phenothiazine may be considered as the lead compounds in terms of potential entry inhibitor for CHIKV. Further, these results should be confirmed by comprehensive cell culture, cytotoxic assays and animal experiments. Certain derivatives of phenothiazines can also be explored in future studies for entry inhibitors against CHIKV. The present investigation thus provides insight into protein structural dynamics of the envelope protein of CHIKV. In addition the study also provides information on the dynamics of interaction of E2 protein with entry inhibitors that will contribute towards structure based drug design.

Keywords: E2 protein, Chikungunya virus, Homology modeling, MD simulation, Phenothiazine, Bafilomycin

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is are-emerging arboviral infection that is the cause of major public health concern [29]. The Chikungunya viral infection share common symptoms with the dengue viral infection characterized by sudden onset of fever, vomiting, nausea, rashes, arthralgia and myalgia [2, 13]. Both CHIKV and DENV are spread by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes [3]. CHIKV is endemic in many parts of the world including Africa, Asia and tropical regions of America [43]. Nearly 94 countries were identified with substantial CHIKV infection in a recent investigation [26]. It was also estimated that around 1.3 billion people are living in risk areas for CHIKV transmission [26]. The CHIKV has been reported from more than 40 countries in the Americas with over 1 million infections in last 2 years [43]. The largest outbreak of CHIKV occurred during 2004–2009 in Indian Ocean region involving millions of people [41].

Chikungunya virus is a member of alphavirus genus in the Togaviridae family. The genome of CHIKV is single stranded positive sense RNA of approximately 11.8 kb in length. The genomic RNA is capped and polyadenylated, and encodes two open reading frames (ORFs) [13]. The 5′ ORF encodes four non-structural proteins (nsP1, nsP2, nsP3 and nsP4) and 3′ ORF encodes the structural polyprotein that is cleaved into the capsid, small polypeptide 6K, E3 and the envelope glycoproteins E2 and E1 [35]. The mature virion is 70 nm in diameter and contains trimeric spikes of E1 and E2 proteins on its surface [25]. The E2 protein is involved in attachment of the virion and E1 protein helps in viral fusion with the host cell [36].

No vaccines or antiviral drugs are available for the Chikungunya virus infection. Therefore, in realization of the true disease burden it is important to screen large number of compounds for their inhibitory effects on the virus. Many studies have investigated the inhibitory effect of various compounds, but none of them have been found to have significant anti-CHIKV activity in animal models [1]. In addition, the in vitro study of such large number of compounds is laborious, time consuming, and costly. Therefore, it is convenient to use the computational approaches to screen out lead compounds. Such lead compounds can then be investigated in detail using experimental approaches. A potential anti-viral strategy against CHIKV involves the inhibition of the viral entry that involves E1 and E2 proteins. The present investigation was thus planned to determine the structure of the E2 protein of Chikungunya virus using computational methods. Molecular docking and MD simulations of the E2 protein-inhibitors (i.e. phenothiazine and bafilomycin) was also carried out to investigate the dynamics of interaction. Identification of the inhibitors of Chikungunya virus infection will contribute towards structure based drug design approaches.

Material and methods

Sequence analysis

The sequence of E2 protein of Chikungunya virus (S27 African strain) was retrieved from NCBI (Accession number: AF339485). This protein sequence was studied through several bioinformatics tools for the present study. The secondary structure of the E2 protein was analyzed with Psipred [23] (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/). Protein glycosylation is important for secretion, localization and stability of the protein. Therefore, N-linked glycosylation sites were predicted using NetNGlyc 1.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/). In addition, the O-linked glycosylation were also predicted using NetOGlyc 4.0 server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetOGlyc/).

Structure prediction and validation

Homology modeling is a computational method used to predict the two as well as three dimensional structure of a protein sequence based on the template protein. The quality of generated model depends on identity between the target and template proteins. The three dimensional structure of E2 protein was identified using a Discovery Studio (DS 4.0) module MODELLER [15]. Phyre2 and iTASSER servers were used to increase the accuracy of the generated model.

The most accurate model was evaluated on the basis of root mean square deviation (RMSD), C-score and TM score. The selected model was refined using CHARMm [45] and energy minimization was done using ChiRotor algorithm of DS. The GROMOS [44] algorithm implemented in DeepView [19] was used for energy minimization of the predicted E2 structure. The three dimensional models were validated by PROCHECK in SAVeS server [21, 22]. PROCHECK server validates the quality of the structural model by the Z-score which indicate the overall model quality. The Ramachandran plot between the psi/phi values that explained the stereo chemical quality was obtained with the PROCHECK program. In addition, the predicted three dimensional structure was also superimposed with the crystallized trimer of Chikungunya virus E1–E2–E3 polyprotein [46] using the Pymol visualization tool.

Mutation analysis

The effect of some reported point mutations on the structure of E2 glycoprotein [31, 40] were analyzed using in silico tools. Various methods were used for the prediction of the effect of mutations on the structure of E2 protein. Swiss-PDB Viewer [19] was used to generate the structural mutants. The structural stability of wild type and mutant E2 protein were compared using the SDM server (Site Directed Mutator). The calculation of stability score is done in terms of change in free energy (ΔΔG). Moreover, the MuStab [37] and I-Mutant 2.0 [6] servers were used for estimating the significance of mutations on the stability of the E2 protein. Both MuStab and I-Mutant 2.0 perform similar analysis with accuracy of 84.59 and 77% respectively. I-Mutant 2.0 is based on support vector machine (SVM) protocol that estimates the change in protein stability upon a point mutation in terms of Gibb’s free energy change (ΔΔG).

Receptor–ligand interactions

The structure of E2 protein generated in silico was used for docking studies with some reported inhibitors of alphaviruses to visualize the interaction using AutoDock4.0 software [24]. The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm with free energy based empirical force-field was used by Autodock4.0 for the prediction of bound conformations [24]. The structure of E2 protein generated in silico was used for docking studies with some reported inhibitors of alphaviruses to visualize the interaction with the predicted active pocket site using AutoDock 4.0 software [24]. AutoDock is a flexible docking program that uses iterated local search global optimization algorithm [24]. The speed and accuracy of docking is much more improved in AutoDock as a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading is used in it. Grid maps were automatically computed in AutoDock. The pdbqt files of both protein and ligands were prepared and polar hydrogen was added. The calculations of binding free energies were done using scoring function of AutoDock with the following equation:

In the above equation i and j are the atoms separated by three consecutive covalent bonds and summation over all is the pairs of i and j atoms moving relative to each other. Each atom has been allotted a type , and a symmetric set of interaction functions of where is distance between atoms i and j.

The ligand receptor preparation, binding site characterization and energy minimization were done for both the ligands and E2 protein. The grid box was adjusted to 80 × 80 × 80 along with X, Y and Z axis with 3.75 Å spacing between the points. The docked complexes were optimized and validated using modules for receptor–ligand interactions in Discovery Studio 4.0 (BIOVIA 2013). In addition, the minimization of docked complexes was done with CHARMM force-field [45].

The docking was also performed with PatchDock [14, 32] in order to increase the accuracy of docking. PatchDock is geometry-based molecular docking tool. In PatchDock the molecule’s surface is divided into convex, concave and flat surfaces patches [11, 12]. The surfaces of ligand and protein are distributed into patches of above surfaces and searched for their complementary patch. The atomic desolvation energy and complementarity of shape both are determined by scoring function. The Energy minimized PDB files of both protein and ligand molecules were submitted with clustering RMSD cut off value of 4.0 Å.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Both the protein–ligand complexes were then subjected to MD simulation studies. The biological function of DNA and proteins and their intense dynamic mechanisms like allosteric transition [7, 48], the drug intercalation into DNA [9], the active and inactive state switching [47], and assembly of microtubules [10], can be studied by analyzing their internal motions [8]. The mechanism of protein–ligand interaction can be studied by two different methods i.e. using static structure and by simulation of dynamic processes involved. MD simulation is the online tool to study the dynamics of the interaction between protein and ligand. MD simulation was performed for E2 protein and for E2-ligand complex using the GROMACS 5.0 software. The Gromos43a1 [42] forcefield was used for the E2 protein while for ligands the generalized Gromos forcefield was utilized [45]. The E2-ligand complexes were then solvated and water molecules and appropriate counter-ions were added to achieve the electrical neutrality in a cubic box of SPC water model [4]. The solvated system was then energy minimized by using steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms for around 10,000 steps till the force on all the atoms went below 100 kJ/mol/nm. The MD simulations of these energy minimized systems were done for up to 40 ns at constant pressure–temperature (NPT). A constant temperature of 300 K with 1 atmospheric pressure was used for the system at a time constant of 5 ps together with the method given by Parrinello and Rahman [27]. The equation of motion was integrated using 2 fs time step. The energy minimized structures were evaluated by plotting trajectories of RMSD and Rg values for each system.

Results and discussion

Sequence properties

The E2 protein of Chikungunya virus prototype strain (S27 African strain) was used for the present investigation (Accession number AF339485). The ProtParam server analysis revealed that the E2 gene (1300 bp) encodes the protein of 423 amino acids. The molecular weight of the protein is 47.054 kDa with theoretical PI of 8.37 and estimated half-life of more than 20 h (yeast, in vivo). The N- and O-linked glycosylation sites were predicted for the E2 protein. There were three N-linked glycosylation sites at residue number 263, 273 and 345 and one O-linked site at residue number 143 with G score of more than 0.5 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The complete sequence of Chikungunya virus E2 protein with N-linked glycosylation sites in blue and O-linked glycosylation site in red color. The arrows on amino acids show the reported mutations used in the present study. In addition, the trans-membrane region is shown by a rectangular outline (color figure online)

The prediction and evaluation of secondary and tertiary structure

The HHpred and PSI-Blast identified crystal structure of the immature envelope glycoprotein of Chikungunya virus (PDB Id: 3n40) as the suitable template for the structure prediction of E2 protein [46]. The study sequence and template alignment shows 41% identity. The MODELLER aligned the template with query sequence and generated the three dimensional model by satisfying the spatial restraints (Fig. 1). The models generated by the software were evaluated on the basis of C-Score (confidence score), RMSD, TM-score and DOPE profile etc. The C-score predicts quality of models based on the convergence and the threading template alignment parameters of the structure assembly. The best model selected had the highest confidence value i.e. 1.75 where 2 was the maximum C-score value. On the whole predicted model was evaluated on the basis of RMSD value and the TM-score with values 3.4 ± 2.3 and 0.96 ± 0.05 respectively. RMSD is the average distance of all the residues of the two structures. A model with the correct topology is indicated by more than 0.5 TM-score. The best model was evaluated using various tools of SAVES server. The Procheck tool of the SAVES server indicated that 74.5% of the residues of the E2 protein were in favored region of the Ramachandran plot (Fig. 2). The additional and generously allowed regions contained 20.8 and 3.6% residues respectively. Further, the plot identified that only 1.18% of the residues were in the disallowed region. The ϕ–ψ distribution score was found to be −0.95.

Fig. 2.

The Ramachandran plot generated from SAVeS server with maximum number of amino acids in the favored region

The secondary structure prediction of E2 protein was performed using GORIV [16] online tool. The predicted E2 protein structure showed 9% α-helix, 60% random coil, and 31% extended strand. The secondary structure image (Fig. 3) was generated using Psipred [23] (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/). The superimposition of the best model of E2 protein was done with crystal structure of immature envelope glycoprotein (E1–E3–E2 trimer) of Chikungunya virus. The superimposed structures showed an RMSD value of 1.63 Å that also validates the predicted structure (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The secondary structure of E2 protein generated using the Psipred server

Fig. 4.

The ribbon image showing superimposition of the modeled E2 protein (purple color) and the crystallized immature E1–E2–E3complex of Chikungunya virus [46] (PDB Id: 3n40) (green color) (color figure online)

Mutational analysis

The E2 protein is involved in attachment of virion with the host cell. Hence, it is the neutralization antigen and therefore a vaccine candidate. The mutations in E2 protein may alter the overall local secondary structure. This may affect structure–function relationship of the E2 protein thereby affecting the overall infectivity of the virus. The in silico stability score prediction of some reported mutations in E2 protein was done in the present study using I-Mutant 2, SDM server and MuStab server. All these servers calculate the stability score or DDG value (Pseudo delta delta G). A negative DDG value is indication of destabilization of the protein structure whereas a positive value suggests that the protein structure is stabilized.

The present study analyzed 5 different reported mutations i.e. G82R, L210Q, I211T, V229I, S375T [31, 34, 40] (Fig. 1). The selection pressure analysis in a previous investigation has showed that 3 of these mutations (L210, I211 and S375) were positively selected [31]. The DDG value of L210Q was found to be slightly negative and for V229I and slightly positive for the mutation S375T. Therefore, it is postulated that these three mutations do not have much contribution to alteration of the overall three dimensional structure of E2 protein. However, these in silico results should be validated by the site directed mutagenesis experiments in laboratory.

The DDG values for two other mutations i.e. I211T and G82R were highly negative and highly positive respectively. Therefore, I211T destabilized and G82R stabilized the three dimensional structure of the E2 protein. A large epidemic of CHIKV occurred in 2004–2009 in the Indian Ocean region affecting millions of people [33]. A point mutation in the E1 protein (A226V) was identified in most of the virus isolates of this epidemic. This unique molecular signature was associated with higher epidemic potential of CHIKV during this epidemic. Further detailed analysis of the epidemic strains revealed that this point mutation was crucial for the high efficiency of replication and dissemination of CHIKV in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Subsequent investigation of the epidemic strains by Tsetsarkin and co-workers revealed that another mutation in the E2 protein (I211T) was essential for the sensitivity of CHIKV to the E1-A226V mutation in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Further, they also concluded that this mutation at 211 position is probably involved in binding of the E2 protein with the receptor on the host cell [41].

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are polymers of disaccharide units that are associated with the outer surface of mammalian cells where they act as virus receptors. Further, it has been postulated that GAGs present the on mammalian cell surface is utilized by E2 protein of CHIKV to bind with the host cell. Silva and colleagues reported that the amino acid at position number 82 in the E2 protein is primary determinant in binding to GAGs on the host cell [34]. The authors concluded that a mutation at this position (G82R) influenced the binding of E2 with the GAGs present on the host cell thereby affecting the viral entry.

Thus mutational analysis of the present study revealed that even the point mutations may affect the overall structure of proteins that may lead to stabilizing or destabilization of the proteins. The in silico predictions of the mutational analysis will thus contribute to information about the structural stability of the E2 protein. Further, comprehensive site directed mutagenesis investigations on these mutations will provide insight into the detailed mechanism of structure stabilization/de-stabilization of E2 protein and its effect on virus pathogenesis.

Molecular docking and MD simulation studies

The docking of E2 protein was done with Autodoc4.0 software [24]. Various compounds from zinc database (50) were screened to check the interaction with E2 protein (data not shown). These included two different compounds, encainide and barbamine that showed good interaction with the E2 protein with binding energies −8.5 and −8.4 (in kcal/mol) respectively. These two compounds, berbamine (calcium channel blocker) [38] and encainide (anti-erithmatic agent) [39] have a pharmaceutical importance and were found to have a good interaction and binding energy with E2 protein. However, the information about the antiviral activity of these compounds was not available in literature. Therefore, the in silico study with these compounds was not done further.

Many other compounds have been reported in literature that demonstrates antiviral activities. Pohjala and co-workers used many pharmaceutically important compounds including the flavonoids, apigenin, chrysin, naringenin, silybin, etc. to study their antiviral activities in terms of virion entry. They concluded that six compounds including chlorpromazine, ethopropazine, methdilazine, perphenazine, thiethylphenazine and thioridazine were found to inhibited SFV (Semliki forest virus) entry into BHK-21 cells. These six compounds share a common core structure i.e. 10H-phenothiazine [28]. Both CHIKV and SFV belong to Alphavirus genus and they share similar antigenic serocomplex and are considered phylogenetically similar [30]. Therefore, these two compounds (phenothiazine and bafilomycin) with known antiviral activities were used for the docking studies. Phenothiazine S ((C6H4)2NH) is an organic compound with thiazine ring. It is frequently used as an inhibitor or stabilizer in chemical industries. Earlier it was used as an insecticide and anti-helminthic for livestock and humans. The bafilomycin is an antibiotic extracted from Streptomyces griseus having macrocyclic lactone ring linked with deoxy sugars. In addition, it is a vacuolar-type-H+-ATPase inhibitor in mammalian cells that prevents acidification of the endosomal compartment, a mechanism commonly employed as a mode of inhibition of infection by viruses which gain entry by receptor-mediated endocytosis and low-pH mediated membrane fusion. An investigation by Hunt and colleagues reported that Bafilomycin A1 was found to block the expression of a virus-encoded reporter gene of sindbis virus in both infection and transfection of the BHK cells [18]. Further, another study reported limited inhibitory effect of bafilomycin in post CHIKV infection in HEK239T cells [5]. The inhibitory effect of bafilomycin has also been reported previously for other viruses like influenza [17].

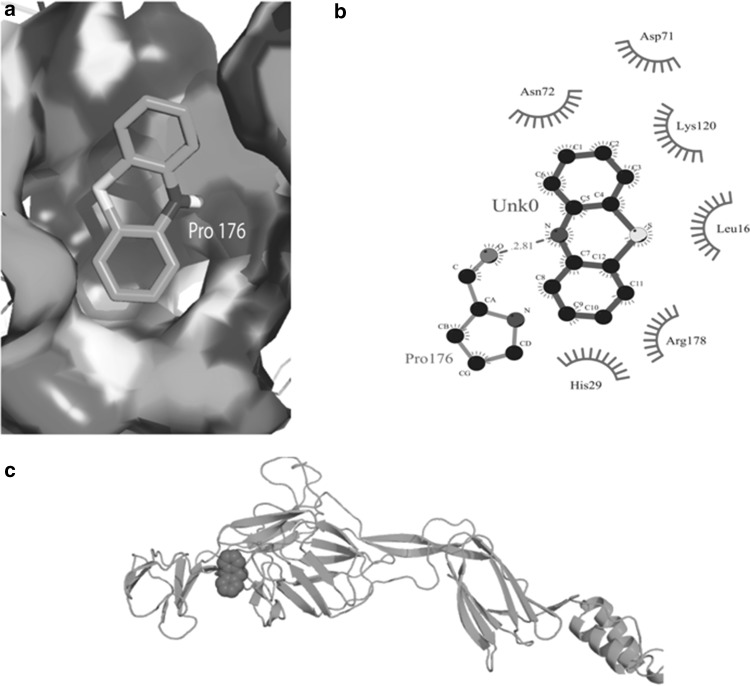

The docking of E2 protein with the two compounds i.e. phenothiazine and bafilomycin was done with Autodoc software. The molecular docking of the E2 protein with phenothiazine indicated good interaction with binding energy of −5.8 kcal/mol and docking score of 3122. In addition, phenothiazine was found to be hydrogen bonded with the protein involving one residue i.e. Pro176 with bond length of 2.81 Å. The other amino acids i.e. Leu16, His29, Asn72, Asp71, Lys120, Arg178 had hydrophobic interaction with the compound (Fig. 5). Further the molecular docking of the E2 protein with the other compound i.e. bafilomycin revealed good interaction with binding energy of −6.2 kcal/mol and a docking score of 5510. The main residues of E2 protein that are involved in hydrogen bonding with the compound include Tyr15, His18, Pro240 and Leu241 with bond length 2.82, 2.71, 3.16 and 3.32 Å respectively. The amino acids involved in hydrophobic interactions with the compound were Ala17, Ser27, Pro20, His127, Pro128 and Pro243 (Fig. 6). These weak non-covalent hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions play a critical role in stabilization of the docked complexes. Further, the docking of E2 protein with the two compounds i.e. phenothiazine and bafilomycin was also performed with Patchdock tool using RMSD cutoff of 4.0 Å. The results of docking of the E2 protein with Autodoc and Patchdock software are summarized in the Table 1. The bafilomycin has high docking score and thus high binding affinity with the E2 protein suggesting stable protein–ligand interaction.

Fig. 5.

The overall structure of E2 protein in complex with Phenothiazine. a 3-D representation of the docked complex, b 2-D representation of the docked complex, residues with hydrophobic interactions are shown in red half circles, ligands are shown in blue black dots. Hydrogen bonds are shown in green color, c 3-D view of docked complex showing the interaction residue positions (color figure online)

Fig. 6.

The overall structure of E2 protein in complex with bafilomycin. a 3-D representation of the docked complex, b 2-D representation of the docked complex, residues with hydrophobic interactions are shown in red half circles, ligands are shown in blue black dots. The hydrogen bonds are shown in green color, c 3-D view of docked complex showing the interaction residue positions (color figure online)

Table 1.

Different parameters generated from molecular docking with Autodoc, Patchdock and Firedock softwares showing interaction of E2 with both the compounds (phenothiazine and bafilomycin)

| E2-ligand | Total interaction energy | Van der Waal’s energy | ACE | Docking score | Binding energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2-phenothiazine | −33.30 | −16.47 | −10.44 | 3122 | −5.16 |

| E2-bafilomycin | −36.27 | −20.22 | −11.22 | 5510 | −5.74 |

The dynamics of the complexes E2-bafilomycin and E2-phenothiazine were further analyzed through MD simulation using GROMACS software. The energy value, RMSD value and radius of gyration were calculated for the E2 protein and protein–ligand complexes by MD simulation. The stabilization and convergence of the native E2 protein and ligand-bound E2 complex was shown by a steady RMSD trajectory. RMSD values were calculated by the equation:

where, t2 is the time of the reference structure, t1 is the particulate time point in the simulation, ri is the atom position i at a particular time and N is the number of atoms.

The RMSD plot shows that MD simulation of the native E2 protein was carried out up to 40 ns. The maximum RMSD value of the native E2 protein was 1.79 nm at 33 ns and the plot of RMSD trajectories was stabilized at 40 ns. Similarly, MD simulation was also carried out for the E2-ligand complexes that showed stability at around 20 ns. The molecular dynamic study of these docked complexes showed that the stability of these complexes is increasing as compared with that of the native E2 protein. The maximum RMSD value for the E2-phenothiazine complex was 1.24 nm at around 8 ns whereas for the E2-bafilomycin complex the maximum RMSD value was 0.6 nm at around 10 ns. The RMSD trajectories of E2-phenothiazine complex was stabilized at 20 ns whereas the E2-bafilomycin complex got stabilized at around 10 ns. The variation between RMSD values of native E2 protein and complex showed that bafilomycin is stabilizing the E2 protein (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The RMSD plots for native E2 protein, E2-bafilomycin and E2-phenothiazine complexes

The compactness of a protein was measured by calculating Rg (radius of gyration). The radius of gyration is the Root Mean Square distance of a particular atom or group of atoms with its center of mass. The Rg was calculated using equation:

in which mi represents mass of atom i and ri imply position of atom i with respect to the center of mass of the studied protein.

A stably folded protein always has a constant or unvarying Rg values at various time points during the simulation and the values vary when the protein starts to unfold [20]. The graph of Rg values was plotted against time throughout the simulation run (Fig. 8). The Rg values for E2, E2-bafilomycin and E2-phenothiazine were 4, 2 and 1.6 nm respectively. The plot depicts that the protein was stably folded in all the three states, E2 alone and in complex with bafilomycin and phenothiazine over the course of time. It was observed that the Rg value for E2 protein was higher as compared to bafilomycin and phenothiazine over the entire simulation time period suggesting that E2-compound complexes were stabilized.

Fig. 8.

Graph showing the Rg values for native E2 protein, E2-bafilomycin and E2-phenothiazine complexes

The present report describes the structure of E2 protein of Chikungunya virus that was determined with homology modeling. Mutational analysis of the E2 protein suggested that point mutations may stabilize/de-stabilize structure of the protein thereby affecting the structure–function relationship. Further, we describe the dynamics of the interaction of E2 protein with two different fusion entry inhibitors (i.e. phenothaizine and bafilomycin) by molecular docking and MD simulation studies. The stable E2-bafilomycin complex was formed as suggested by high docking score and high binding affinity. Further, the MD simulations revealed that both the inhibitors were stabilizing the E2 protein. Thus, phenothaizine and bafilomycin may be considered as the lead compounds in terms of potential entry inhibitor for the Chikungunya virus. Additional elaborate experimental investigations including cytotoxicity studies will provide insight into the detailed mechanism of inhibition of Chikungunya virus infection by phenothaizine and bafilomycin and their derivatives. Further, besides Chikungunya virus these compounds may also be investigated for the anti-viral activities against other Alphaviruses for development of broad spectrum therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgements

Work in our laboratory is supported by grants from the University Grants Commission and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research. The study was supported by King Saud University, Deanship of Scientific Research, College of Science Research Centre.

References

- 1.Abdelnabi R, Neyts J, Delang L. Antiviral strategies against Chikungunya virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1426:243–253. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3618-2_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afreen N, Deeba F, Khan WH, Haider SH, Kazim SN, Ishrat R, Naqvi IH, Shareef MY, Broor S, Ahmed A, Parveen S. Molecular characterization of dengue and Chikungunya virus strains circulating in New Delhi, India. Microbiol Immunol. 2014;58(12):688–696. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afreen N, Deeba F, Naqvi I, Shareef M, Ahmed A, Broor S, Parveen S. Molecular investigation of 2013 dengue fever outbreak from Delhi, India. PLOS Curr Outbreaks. 2014 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.0411252a8b82aa933f6540abb54a855f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, Hermans J. Interaction models for water in relation to protein hydration. In: Intermolecular forces. Berlin: Springer; 1981. p. 331–342.

- 5.Bernard E, Solignat M, Gay B, Chazal N, Higgs S, Devaux C, Briant L. Endocytosis of Chikungunya virus into mammalian cells: role of clathrin and early endosomal compartments. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7):e11479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capriotti E, Fariselli P, Casadio R. I-Mutant 2.0: predicting stability changes upon 464 mutation from the protein sequence or structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(465):W306–W310. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou KC. The biological functions of low-frequency vibrations (phonons). VI. A possible dynamic mechanism of allosteric transition in antibody molecules. Biopolymers. 1987;26:285–295. doi: 10.1002/bip.360260209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou KC. Low-frequency collective motion in biomacromolecules and its biological functions. Biophys Chem. 1988;30:3–48. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(88)85002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou KC, Mao B. Collective motion in DNA and its role in drug intercalation. Biopolymers. 1988;27:1795–1815. doi: 10.1002/bip.360271109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou KC, Zhang CT, Maggiora GM. Solitary wave dynamics as a mechanism for explaining the internal motion during microtubule growth. Biopolymers. 1994;34:143–153. doi: 10.1002/bip.360340114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connolly ML. Analytical molecular surface calculation. J Appl Crystallogr. 1983;16:548–558. doi: 10.1107/S0021889883010985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly ML. Solvent-accessible surfaces of proteins and nucleic acids. Science. 1983;221:709–713. doi: 10.1126/science.6879170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deeba F, Islam A, Kazim SN, Naqvi IH, Broor S, Ahmed A, Parveen S. Chikungunya virus: recent advances in epidemiology, host pathogen interaction and vaccine strategies. FEMS Pathog Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duhovny D, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ, et al. Efficient unbound docking of rigid molecules. In: Gusfield D, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 2nd workshop on algorithms in bioinformatics (WABI) Rome, Italy, lecture notes in Computer Science. Berlin: Springer; 2002. pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eswar N, Eramian D, Webb B, Shen MY, Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;426:145–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garnier J, Gibrat JF, Robson B. GOR method for predicting protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:540–553. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(96)66034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiroshi Ochiai H, Sakai S, Hirabayashi T, Shimizu Y, Terasawa K. Inhibitory effect of bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type proton pump, on the growth of influenza A and B viruses in MDCK cells. Antiviral Res. 1995;27:425–430. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00040-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt SR, Hernandez R, Brown DT. Role of the vacuolar-ATPase in Sindbis virus infection. J Virol. 2011;85(3):1257–1266. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01864-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan W, Littlejohn TG. Swiss-PDB viewer (deep view) Brief Bioinform. 2001;2:195–197. doi: 10.1093/bib/2.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar CV, Swetha RG, Anbarasu A, Ramaiah S. Computational analysis reveals the association of threonine 118 methionine mutation in PMP22 resulting in CMT-1A. Adv Bioinform. 2014;2014:502618. doi: 10.1155/2014/502618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK—a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGuffin LJ, Bryson K, Jones DT. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:404–405. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulvey M, Brown DT. Assembly of the Sindbis virus spike protein complex. Virology. 1996;219:125–132. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nsoesie EO, Kraemer MU, Golding N, Pigott DM, Brady OJ, Moyes CL, Johansson MA, Gething PW, Velayudhan R, Khan K, Hay SI, Brownstein JS. Global distribution and environmental suitability for Chikungunya virus, 1952 to 2015. Euro Surveill. 2016 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.20.30234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parrinello M, Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals—a new molecular-dynamics method. J Appl Phys. 1981;52(12):9. doi: 10.1063/1.328693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pohjala L, Utt A, Varjak M, Lulla A, Merits A, Ahola T, Tammela P. Inhibitors of alphavirus entry and replication identified with a stable Chikungunya replicon cell line and virus-based assays. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12):e28923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers AM, Logue CH. Changing patterns of Chikungunya virus: reemergence of a zoonotic arbovirus. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:2363–2377. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powers AM, Brault AC, Shirako Y, Strauss EG, Kang W, Strauss JH, Weaver SC. Evolutionary relationships and systematics of the alphaviruses. J Virol. 2001;75:10118–10131. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10118-10131.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahu A, Das B, Das M, Patra A, Biswal S, Kar SK, Hazra RK. Genetic characterization of E2 region of Chikungunya virus circulating in Odisha, Eastern India from 2010 to 2011. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;18:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W363–W367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney MC, Lavenir R, Pardigon N, Reynes JM, Pettinelli F, Biscornet L, Diancourt L, Michel S, Duquerroy S, Guigon G, Frenkiel MP, Bréhin AC, Cubito N, Despres P, Kunst F, Rey FA, Zeller H, Brisse S. Genome microevolution of Chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva LA, Khomandiak S, Ashbrook AW, Weller R, Heise MT, Morrison TE, Dermody TS. A single-amino-acid polymorphism in Chikungunya virus E2 glycoprotein influences glycosaminoglycan utilization. J Virol. 2014;88(8):2385–2397. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03116-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder AJ, Sokoloski KJ, Mukhopadhyay S. Mutating conserved cysteines in the alphavirus E2 glycoprotein causes virus-specific assembly defects. J Virol. 2012;86(6):3100–3111. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06615-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solignat M, Gay B, Higgs S, Briant L, Devaux C. Replication cycle of Chikungunya: a re-emerging arbovirus. Virology. 2009;393(2):183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teng S, Srivastava AK, Wang L. Sequence feature-based prediction of protein stability changes upon amino acid substitutions. BMC Genom. 2010;11(Suppl. 2):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-S2-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian H, Pan QC. A comparative study on effect of two bisbenzylisoquinolines, tetrandrine and berbamine, on reversal of multidrug resistance. Yao XueXueBao. 1997;32(4):245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toivonen L, Kadish A, Morady F. A Prospective comparison of class IA, B, and C antiarrhythmic agents in combination with amiodarone in patients with inducible, sustained ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1991;84(1):101–108. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.84.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsetsarkin KA, McGee CE, Volk SM, Vanlandingham DL, Weaver SC, Higgs S. Epistatic roles of E2 glycoprotein mutations in adaption of Chikungunya virus to Aedes albopictus and Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(8):e6835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsetsarkin KA, Chen R, Leal G, Forrester N, Higgs S, Huang J, Weaver SC. Chikungunya virus emergence is constrained in Asia by lineage-specific adaptive landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(19):7872–7877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018344108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJC. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Duijl-Richter MKS, Hoornweg TE, Rodenhuis-Zybert IA, Smit JM. Early events in Chikungunya virus infection—from virus cell binding to membrane fusion. Viruses. 2015;7:3647–3674. doi: 10.3390/v7072792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Gunsteren WF, Billeter SR, Eising AA, Hunenberger PH, Kruger P, Mark AE, Scott WRP, Tironi IG. Biomolecular simulation: the GROMOS96 manual and user guide. Zurich: VdfHochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zurich; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I, Mackerell AD., Jr CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Voss JE, Vaney MC, Duquerroy S, Vonrhein C, Girard-Blanc C, Crublet E, Thompson A, Bricogne G, Rey FA. Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature. 2010;468(7324):709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang JF, Chou KC. Insight into the molecular switch mechanism of human Rab5a from molecular dynamics simulations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:608–612. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang JF, Gong K, Wei DQ, Li YX, Chou KC. Molecular dynamics studies on the interactions of PTP1B with inhibitors: from the first phosphate-binding site to the second one. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2009;22:349–355. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]