Abstract

Viruses are the most abundant biological entities on Earth and can be found in a variety of environments. A high prevalence of viruses in marine and freshwater systems was initially reported by Spencer in 1955, but the ecological significance of viruses is insufficiently known even until the present day. Viruses are known to play a key role in the biology of freshwater bacteria: controlling the bacterial abundance, composition of species, and acting as intermediaries in the transfer of genes between bacterial populations. In our study a variety of viromes of the Ile-Balkhash water basin were identified. It was found that the composition of viruses of the Ile-Balkhash region is made up not only of a wide variety of autochthonous viruses typical for phytoplankton hydro ecosystems, but also of representatives of allochthonous viruses—such families as Coronaviridae, Reoviridae and Herpesviridae—indicating anthropogenic pollution of the basin. The research designed to investigate the viral abundance, spread, infectious cycle, seasonal dynamics, composition of the viral community, and the influence of viruses on the bacteria, phytoplankton and recycling of nutrients, as well as the impact of environmental factors on the viral ecology in a variety of marine and freshwater systems is very relevant nowadays.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13337-016-0353-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bacteriophage, Metagenomics, Viromes, Biodiversity, Water ecosystems

Introduction

Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites. That is a fundamental factor of evolutionary process of their adaptation to the conditions of existence in certain types of biological hosts, and to spread in the populations of these hosts. The contagiousness of an infectious agent is a virus transition from the infected organism to a susceptible one. Usually the contagiousness consists of three main stages: virus yield from an infected organism into the environment, temporary stay of the virus in abiotic or biotic environment objects and the penetration of the virus into a susceptible organism. The stages of virus release and penetration have been objects of study of researchers since the discovery of viruses, but the question of mechanisms of virus circulation in the environment for a long time remained unclaimed. For example, the presence of viruses in water bodies has been known since the middle of last century [1, 2]. However, an active research into their ecological importance in aquatic ecosystems has begun only with the works of Berg et al. [3], who discovered a very high concentration of water viruses (up to 108 particles/ml), mostly classified as bacteriophages. Now it is proved that viruses are an important and integral part of biological communities of aquatic ecosystems. Viral communities influence the abundance, species composition and diversity of planktonic microorganisms, as well as changes the flows of matter and energy in the microbial communities [4–7]. In addition, viruses are intermediaries of genetic exchange within and between species through transduction [8]. Regularities of distribution and functioning of aquatic viruses are complex and still poorly understood. In this regard, the necessity of the research into the role of viruses-bacteriophages in the functioning of microbial communities in various aquatic ecosystems is obvious.

Today there is a large amount of publications devoted to the study of biodiversity of viruses in fresh and marine waters and the study of influence on their composition of the season, trophic status of the water reservoir, depth of sampling of material for research and anthropogenic influences [9–11]. They have revealed that the composition of viruses is affected not only by the geographical location of the water body but also by the variety of microorganisms inhabiting it [12]. It was also shown that due to mixing of sea and fresh water, inflow of large amounts of nutrient and intensive mixing of deep water with surface water in estuaries, there occur physiological, genetic and ecological changes in microbial communities. This in turn affects the virome and biodiversity as a whole in estuary zones of reservoirs. At the same time almost no studies into the influence of the river virus diversity on the virus composition of a large water bodies, fed by these rivers have been made so far.

In our research, we made a comparative study of viromes from the Ile-Balkhash region of Kazakhstan. We made a comparative study of viromes from three major water reservoirs of this basin: the Ile River, Kapchagay Reservoir and the freshwater part of Lake Balkhash. The works of such direction are highly relevant, since it sheds some light on the diversity of viruses and their ratio depending on the geographical location of each water body in the basin. In addition the viromes comparison enables us to assess the anthropogenic influence on the diversity of viruses.

Materials and methods

Study sites

The hydrographic network of the Ile-Balkhash region is represented by rivers Ile, Karatal, Aksu and Lepsi with their numerous tributaries. The Ile River is the largest waterway of the Ile-Balkhash region. It originates in Central Tien-Shan and, after leaving the Kapchagay gorge, carries its waters through the desert of the Balkhash plain into the regional water artery towards Lake Balkhash.

The region was chosen due to the fact that the area of the Ile-Balkhash basin is 413 thousand square kilometers (km2), of which 353 thousand km2 are located on the territory of Kazakhstan. The flood plain of the basin of the Ile River drains the water into Lake Balkhash and covers the area of 119 thousand km2. Lake Balkhash is the third largest intra-continental reservoir of water after the Caspian Sea and the Aral Sea. A distinctive feature of the basin is its orographic and climatic heterogeneity, as well as a wide variety of environmental conditions it is subject to. A narrow strip of the arid steppe zone to the north of the basin is followed by Northern Balkhash semi-desert and, subsequently, by the desert stretching from the southern coast of Lake Balkhash. Irrigated agriculture practiced within the boundaries of the basin is considered to be the most water-intensive sector of the country’s agriculture. The irrigated agriculture adversely effects the ecological situation in the basin through contamination with pesticides and its contribution to soil salinity.

The largest tributaries of the Ile River are the left-bank rivers Charyn, Turgen, Issyk, Talgar, Kaskelen, Kurty and the right-bank rivers—Horgos, Usek and Borohudzir. They all belong to the mixed feeding river type (Supl. Figure 1).

The rivers are losing a significant part of their flow to filtration in unconsolidated clastic sediments and partially to evaporation. These are fresh water rivers with mineralization of less than 1 g/L. Their inflows do not significantly increases the Ile River runoff due to the large losses to filtration and withdraws for irrigation. At the confluence with the lake, the Ile River forms a delta which is divided into three arms: Topar, Ile and Zhideli. The Ile River is a snow-glacial and ground water-fed watercourse susceptible to spring-summer floods. Lake Balkhash is the main reservoir for the water flow in the region. It is located in a cavity. Its western part contains fresh water with mineralization of up to 1 g/L, and in its eastern part the water is brackish and salty with mineralization of greater than 3 g/L. The main source of the incoming water and a factor influencing the salt balance of the lake is the river flow [13].

Sampling sites and sample collection

Water samples of the Ile-Balkhash region were collected into sterile 1L bottles and fixed with formalin (final concentration 1%) or with glutaraldehyde (final concentration 2%). The samples were collected from the surface at 1.0 m depth at one week intervals during the summer period of 2014. The water samples were collected from the following reservoirs of the Ile-Balkhash region: Lake Balkhash. Water samples were collected in the coastal area near Balkhash city. The coordinates of the collections are 46°49′24.9″N 74°58′51.7″E (Supl. Fig. 2). Kapchagay water reservoir. Water samples were collected in the coastal area near Kapchagay city. The coordinates of the collection are 43°52′5.5″N 77°16′24.9″E (Supl. Fig. 3). River Ile. Water samples were collected near the mouth of the river before its offing into the Kapchagay water reservoir. The coordinates of the collection are 43°51′13.7″N 78°27′01.3″E (Supl. Fig. 4).

Sample fractionation

1000 mL of each sample was sequentially filtered through polycarbonate filters (Millipore) with 1.2, 0.45 and 0.22 micron pores to remove zooplankton, phytoplankton and bacterioplankton. The water was collected into sterile bottles and fixed with formaldehyde (final concentration 1%). Bacteriophages were precipitated by ultracentrifugation using Beckman-L8-55 fixed-angle rotor at 100,000×g for 2 h. The pellet was resuspended in sterile 1.5 mL tubes. Nucleic acid was isolated from 9 individual 1 L samples [Three samples from the Ile River, three samples from Kapchagay water reservoir and three samples from Lake Balkhash (freshwater part of the lake)] using Pure Link Viral DNA/RNA Mini kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The isolated nucleic acid was further concentrated using a double volume of absolute ethanol and 1/10th volume of 3 M sodium-acetate (pH 5.2) and dissolved in 20 μl of 1× TE (pH 8.0). The concentrated nucleic acid was then stored at −20 °C. The concentration of the nucleic acid samples was measured using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen).

Preparation of nucleic acid from samples for sequencing

After extraction, nucleic acid amounts of 10 and 100 ng were used in Illumina sequencing library preparation as described in the Genoscope protocol (Genoscope Illumina protocol) for sequencing with HiSeq. Fragment size distribution of each library was checked using Bioanalyzer and High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent). Samples were then normalized according to the supplier’s instruction using Nextera XT DNA Sample Prep Kit. Five microliters of each library was pooled and concentrated. The final pool of each library was then quantified using qPCR and sequenced using 100 bp paired-end, HiSeq 2000, Illumina platform.

Bioinformatic analyses

Paired-end sequence reads generated from the Illumina HiSeq were assembled into contigs using standalone Edena software, freely available under the General Public License (GPLv3) at www.genomic.ch/edena.php. This tool is all publicly available, and currently often used to assemble short reads generated by next-generation sequencing platforms, such as Illumina Genome Analyzer (read length = 35–150 bp). In our studies with the purpose of finding the greatest number of bacteriophages the required intersection of reads was set to 35 nucleotides. Simulated single-end and paired-end reads were generated from benchmark sequences with several variable parameters, including depth of coverage, base calling error rate and individual read length. Depth of coverage is the average number of reads by which any position of an assembly is independently determined. As a source of benchmark sequences (viral genomes) we used a standalone version of the NCBI nucleotide database comprising 6079 complete genomes of viruses.

The length of the obtained sequences ranged from 162 to 190,000 bp. The contigs were then uploaded to Metavir (http://metavir-meb.univ-bpclermont.fr/) pipeline for phylogenetic analysis (N 151,301, 173,141, 116,319) [14]. Sequences were also uploaded and analyzed using MG-RAST server (http://metagenomics.anl.gov/), an online metagenome annotation pipeline [15]. Before uploading, sequences were quality trimmed using MG-RAST QC pipeline, which included removal of artificial or technical replicates [16] and removal of low quality sequences [17]. Gene-calling was performed using MG-RAST automated pipeline which included the use of FragGeneScan [18], clustering of predicted proteins at 90% identity by using uclust [19] and the use of sBLAT, and applying of the BLAT algorithm [20] for similarity analysis of each cluster. Taxonomic composition of the viromes was obtained through comparison of sequences to the curated NCBI RefSeq complete viral genomes protein sequence database using blastX with an e-value cut-off of ≤10−3. Taxonomic composition was deduced from the best blast hit of each contig.

Results

Nucleic acid isolated from water samples

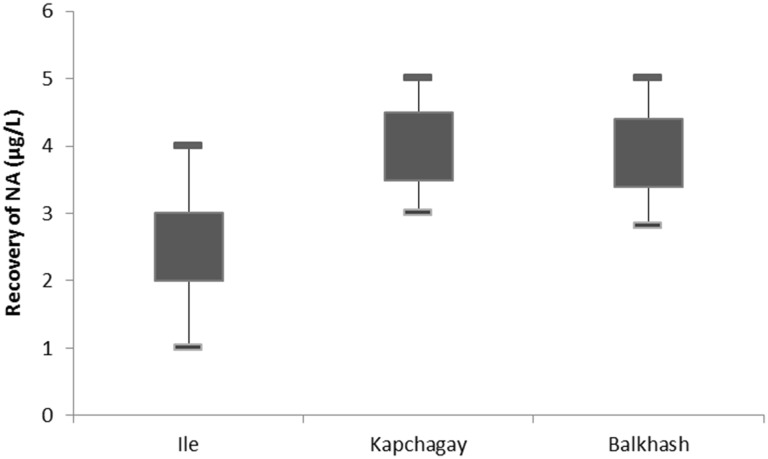

Nucleic acid was obtained from the collected water samples of different freshwater reservoirs of the Ile-Balkhash region. A total of 9 samples (three samples from each reservoir) were used to extract nucleic acid. Recovery of nucleic acid varied from 2.5 to 4.0 μg from 1 L water samples (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Recovery of nucleic acid from freshwater environment. On the abscissa axis are different reservoirs, on the ordinate axis is recovery of nucleic acid

Overview of viromes

After the bioinformatic processing of sequencing databases, 3 data sets consisting of 346,628 contigs for the Ile River sample, 265,687 contigs for the Kapchagay Reservoir sample and 428,084 contigs for the Lake Balkhash sample were obtained (Table 1). The data sets contained between 12 and 17 million nucleotides. Analysis with MG-RAST and Metavir programs showed that the investigated data sets contained 249,951; 211,603 and 269,955 predicted genes for the water samples of the Ile River, Kapchagay and Balkhash, respectively.

Table 1.

Overview of the viromes in reservoirs of the Ile-Balkhash region

| Sample | Quantity of sequences | Quantity of nucleotides | discounted contigs | Predicted genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ile | 346,628 | 155,162,571 | 151,301 (51 contigs were detected as circular) | 249,951 |

| Kapchagay | 265,687 | 128,398,623 | 116,319 (27 contigs were detected as circular) | 211,603 |

| Balkhash | 428,084 | 174,433,273 | 173,141 (65 contigs were detected as circular) | 269,955 |

Taxonomic composition of viromes

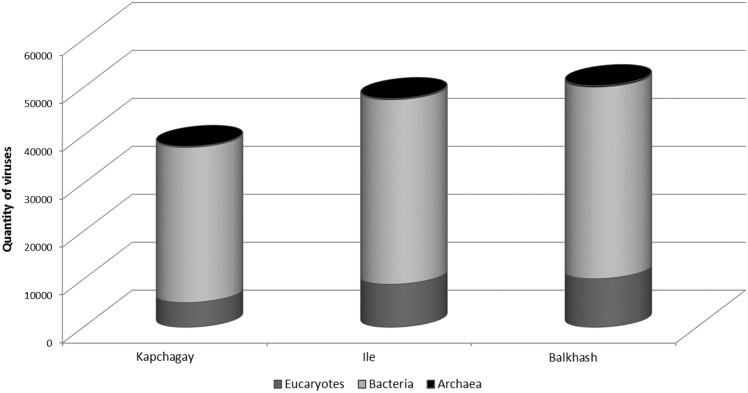

Taxonomic composition of the viral communities was determined through comparison of sequence reads against the curated non-redundant RefSeq Virus database using blastX with an e-value threshold of ≤10−3. The presence of viruses of three domains (archaea, bacteria and eukaryotes), which characterizes the qualitative and quantitative composition of the viromes was found in each reservoir (Fig. 2). Comparative analysis of the ratio of archaea, bacteria and eukaryote viruses showed the highest number of eukaryote viruses in the Lake Balkhash sample in comparison to the samples from other reservoirs, the number of the viruses of archaea was approximately equal in all the water samples.

Fig. 2.

The number of viruses infecting the three domains of life. On the abscissa axis are different reservoirs, on the ordinate axis is quantity of viruses of three domains (in thousands). Each domain is marked in a different color

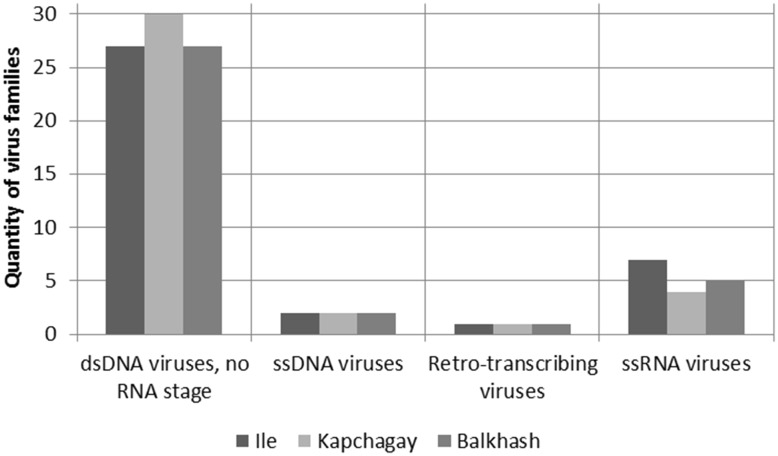

Representatives of 37 families of viruses belonging to 4 types of nucleic acids were identified in the investigated samples (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Annotation of the viromes sequences. On the abscissa axis are families of viruses with different types of nucleic acids, on the ordinate axis is quantity of virus family

The maximum number of families belonged to double-stranded DNA viruses without RNA stage in replication. It was identified that the maximum amount of viral sequences belonged to representatives of five families of dsDNA viruses (Table 2): bacteria viruses Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, Podoviridae, plant viruses Phycodnaviridae and protozoa viruses Mimiviridae. Apart from these major viral families, viruses belonging to other families such as Asfarviridae, Poxviridae, Herpesviridae etc. were also present in these viromes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Viral families in reservoirs of the Ile-Balkhash region

| Virus family | Ilea | Balkhasha | Kapchagaya |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myoviridae | 30.4 | 41.8 | 36.7 |

| Siphoviridae | 22.7 | 19.4 | 23.6 |

| Podoviridae | 15.2 | 10.1 | 13.0 |

| Phycodnaviridae | 13.7 | 10.8 | 7.6 |

| Mimiviridae | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.0 |

| Adenoviridae | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.011 |

| Ampullaviridae | 0.002 | – | – |

| Ascoviridae | 0.248 | 0.278 | 0.427 |

| Asfarviridae | 0.128 | 0.012 | 0.029 |

| Baculoviridae | 0.166 | 0.119 | 0.124 |

| Bicaudaviridae | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.033 |

| Bidnaviridae | 0.002 | – | – |

| Caulimoviridae | 0.003 | 0.003 | – |

| Circoviridae | 0.002 | – | – |

| Endornaviridae | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Hepadnaviridae | – | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Alloherpesviridae | 0.038 | 0.043 | 0.044 |

| Herpesviridae | 0.084 | 0.135 | 0.136 |

| Malacoherpesviridae | 0.005 | – | – |

| Hytrosaviridae | 0.041 | 0.027 | 0.042 |

| Inoviridae | 0.062 | 0.079 | 0.149 |

| Iridoviridae | 0.308 | 0.309 | 0.287 |

| Lipothrixviridae | 0.044 | 0.072 | 0.051 |

| Rudiviridae | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.020 |

| Marseileviridae | 0.282 | 0.237 | 0.216 |

| Microviridae | 0.012 | 0.022 | 0.004 |

| Nimaviridae | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.007 |

| Parvoviridae | 0.003 | – | – |

| Papillomaviridae | – | 0.002 | – |

| Polydnaviridae | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.007 |

| Poxviridae | 0.588 | 0.660 | 0.638 |

| Retroviridae | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.016 |

| Polyomaviridae | – | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Arenaviridae | 0.002 | 0.002 | – |

| Closteroviridae | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.007 |

| Flaviviridae | 0.002 | – | – |

| Coronaviridae | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.009 |

| Picornaviridae | 0.002 | – | 0.002 |

| Potyviridae | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.044 |

| Tymovirales | 0.002 | 0.002 | – |

| Tectiviridae | 0.034 | 0.015 | 0.036 |

| Reoviridae | – | 0.003 | 0.016 |

| Sphaerolipoviridae | – | 0.022 | – |

| Costicoviridae | – | – | 0.007 |

| Fuselloviridae | – | – | 0.007 |

| Astroviridae | – | – | 0.002 |

| Mesoniviridae | – | – | 0.007 |

| Turriviridae | – | – | 0.002 |

| Unclissified | 11.1 | 11.1 | 12.8 |

| viruses |

a% of viral reads

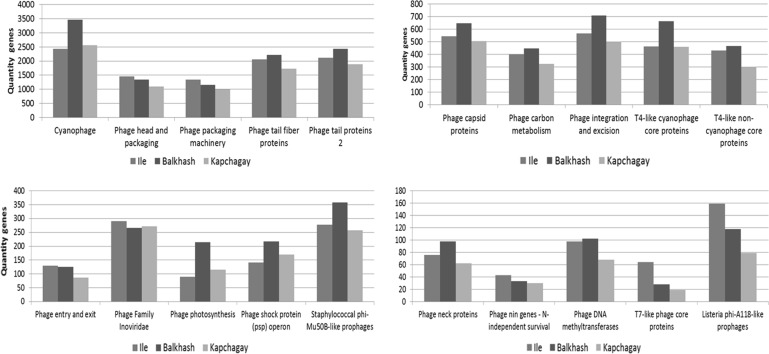

Analysis of the investigated data sets confirmed the dominant position of these five virus families of bacteria, algae and protozoa, and showed the presence of the main metabolic and structural groups of genes of bacteriophages (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Main metabolic and structural groups of genes of bacteriophages of the Ile-Balkhash region. On the abscissa axis are metabolic and structural groups of genes of bacteriophages, on the ordinate axis is quantity of genes. Different color indicates each of the reservoirs

Comparison of the viromes

A comparative assessment of data sets obtained from three different water reservoirs was carried out for the purpose of investigation of viromes of the Ile-Balkhash region. The amount of viral sequences representing the Myoviridae family made 30% in the Ile River sample, 37% in Kapchagay sample, and 42% in Lake Balkhash sample. However, representatives of the Podoviridae family were prevalent in the Ile River sample −15%, made 13% in the Kapchagay sample and 10% in the Balkhash sample.

Analysis of the amount of viruses of the Siphoviridae family showed a pattern similar to that of the Podoviridae family representatives. For example, the amount of viruses of this family in the waters of the Ili River and Kapchagay water reservoir were 23–24%, and in the water of Lake Balkhash contained only 19%. A similar decrease was observed in the analysis of algae viruses: the content changed from 14% in the river to 7–11% in the lakes. The quantity of viruses of Mimiviridae family affecting amoebae remained almost unchanged throughout the samples and amounted to 4–5%.

The group “Other viruses” includes another 42 families, the content of which in samples varied from 0.002–0.638% (Table 2).

Discussion

Historically, phage research contributed important insights into the field of molecular biology [21]. The recent discovery of viral abundance and diversity of natural environment caused a huge interest to viral ecology [10, 21–23]. Allochthonous and autochthonous viruses have a crucial influence on the microbial ecosystem. It was found that the interrelation of respective phages and bacteria makes up the same balance as the ratio of predators and rodents in the macrocosm. Viruses are responsible for 20–40% of marine microbial mortality [23]. Viral-induced lysis of microbes redirects organic matter back into the microbial loop and away from microalgae, zooplankton and fish [4, 24]. Viral infection also facilitates the transfer of genes among phages and their hosts, thereby promoting a wide variety of life on the planet. [25] Additionally, phage can also affect human health, for example, by changing pathogenic properties of bacteria such as Vibrio cholerae [26], or by interacting with bacteria present in the human microbiome [27, 28].

Therefore, the study of viromes diversity in the reservoirs is of great importance for characterization of the ecological status of aquatic ecosystems. In our research, a comparative study of the diversity of viruses in two reservoirs of the Ile-Balkhash region conjoined by the Ile River was carried out. The study sites were selected for several reasons, one of which is an attempt at a comparative study of viral diversity in waters of different origins (artificial and relict) connected by a river artery.

The aim of this pilot project was to show the diversity of viral communities in the region in about the same temperature conditions, depth and time of year, which made comparative characterization of the water bodies possible from the environmental point of view.

Considering the close interrelation between the diversity of microbial and viral communities, three entities connected to each other and having approximately equal taxonomic compositions of bacterial microflora and zooplankton were chosen as sites of the research.

Sampling was made in the main reservoirs of the Ile-Balkhash basin—Lake Balkhash, the Ile River and Kapchagay water reservoir—to get an overview of the diversity of aquatic virus species. Nucleic acids were isolated from the collected samples in the amount of 2.5–4 µg per 1 L water sample, which corresponds to the average number of isolated nucleic acids from the same volume [29]. Considering that rather small input amounts of ng are sufficient for sequencing of nucleic acid with Illumina HiSeq [30], in further studies it will be possible to reduce the volume of water samples in order to decrease the time and cost of isolation of nucleic acids.

As a result of the whole genome sequencing 346,628, 265, 687 and 428, 084 sequences were obtained in the reservoirs of Ile, Kapchagay and Balkhash respectively. This number of sequences had homology with sequences in public databases, which was determined by loading reads into MG-RAST and Metavir. The number of predicted genes from all three samples was approximately the same: 249,951; 211,603 and 269,955, which indicates that the number of contigs does not determine the number of significant genes. The obtained sequences mainly referred to double-stranded DNA viruses (Fig. 3), most of which were bacteriophages, and belonged to three main families of tailed phages: Myoviridae, Siphoviridae and Podoviridae (Table 2). The percentage of these virus families was 68.3% for the Ile River, 71.3% for Lake Balkhash, and 73.3% for Kapchagay Reservoir. The most numerous of them were viruses of Myoviridae family (the percentage of 30.4–41.8% in the studied samples). This is due to a high content of cyanophages that infect cyanobacteria, a basic prokaryotic component of aquatic ecosystems.

It was found that at the transition from the river to the lake there was a change not so much in the qualitative as in the quantitative composition of the viruses. The amount of viral sequences of the Myoviridae family was 30% in the Ile River, whereas in the sample from Kapchagay this quantity increased to 37%, and in the sample from Balkhash it went up to 42%. Somewhat different was the case with the Podoviridae family viruses: in the river sample these viruses made up 15%, in the water of Kapchagay they were 13%, and in the Balkhash sample −10%.

Also, all the studied water reservoirs contained a sufficiently high amount of viruses belonging to the Phycodnaviridae family.

A special group of viromes were representatives of viruses of “Other” families. The group “Other viruses” (2%) comprised sequences of such families as Poxviridae (0.59–0.66%), Coronaviridae (0.02–0.09%), Reoviridae (0–0.02%) and Herpesviridae (0.08–0.14%), etc. In the Kapchagay sample a small percentage (less than 0.007%) of viruses of the Costicoviridae, Fuselloviridae, Astroviridae, Mesoniviridae and Turriviridae families was also found (Table 2). Despite the fact that their number did not exceed 2%, regardless of the reservoir, this group of viruses is an important environmental component in the ecological characterization of the reservoir. Presence of the Poxviridae family sequences in all the investigated reservoirs suggests a possible focus of this group of infections, and calls for a careful study of the epidemiological and zoonotic component of representatives of this group of viruses. Changes in the numbers of representatives of the Coronaviridae, Reoviridae and Herpesviridae families directly indicates some fecal pollution of the studied water bodies.

Detection of viruses of the Costicoviridae, Fuselloviridae, Astroviridae, Mesoniviridae and Turriviridae families shows that there is a more pronounced ecological pressure on the Kapchagay reservoir compared to the other studied reservoirs of the Ile-Balkhash region. Results of the study of biodiversity of viruses in the reservoirs, their population and genomic changes will help predict and control the ecological status of the specified aquatic ecosystems, which is very relevant today. Comparison of species diversity in water reservoirs from different regions shows different environmental features of the regions, describes the extent of purity of water and provides additional information for surveillance and/or assessment of risks to public health (through identification of sequences associated with pathogens).

Some authors claim that reproduction of lake ecosystems determines the composition and diversity of viral communities. For example, Drucker and Dutova [31] found that morphological diversity among phages of the Myoviridae family is dominant in rivers, while the Siphoviridae family prevails in lakes. Whereas our research shows that bacteriophages of the Myoviridae family dominate all three studied reservoirs, with their higher content nevertheless being observed in the lake.

Analysis of virus diversity of the Ile-Balkhash basin showed not only a wide variety of autochthonous viruses typical for hydro ecosystems, but also is a good tool to assess the pollution of the water bodies, as presence of viruses of the families such as Coronaviridae, Reoviridae and Herpesviridae indicates pollution of the water bodies with various sewages.

The study of diversity of viral community in different water bodies is of great of theoretical and practical importance, since it gives a more precise description of the ecological state of the reservoir and provides a snapshot of epizootic and epidemiological status of the region. A further study involving larger geographical areas will provide more information on the diversity of viral communities in the ecologically important sensitive aquatic ecosystems of the Ile-Balkhash region.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Map of the Ile-Balkhash region. Ile-Balkhash region is marked by a yellow square (TIFF 1823 kb)

Lake Balkhash – place of collection point of water samples. Sample site on the Lake Balkhash is marked by a red flag (TIFF 2620 kb)

The Kapchagay water reservoir–place of collection point of water samples. Sample site on the Kapchagay water reservoir is marked by a red flag (TIFF 2450 kb)

River Ile – place of collection point of water samples. Sample site on the River Ile is marked by a red flag (TIFF 2748 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant 0115PK01095 from the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan. The authors thank the “Genotek” company’s employees for help with the sequencing of the obtained samples.

References

- 1.Spencer R. A marine bacteriophage. Nature. 1955;175:690–691. doi: 10.1038/175690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kriss AE, Rukina EA. Bacteriophage in the sea. Rep Acad Sci USSR New Ser. 1947;57(8):833–835. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg O, Børsheim Y, Bratbak G, Heldal M. High abundance of viruses found in aquatic environments. Nature. 1989;340:467–468. doi: 10.1038/340467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuhrman A. Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature. 1999;399:541–548. doi: 10.1038/21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noble RT, Middelboe M, Fuhrman JA. The effects of viral enrichment on the mortality and growth of heterotrophic bacterioplankton. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1999;18:1–13. doi: 10.3354/ame018001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bratbak G, Heldal M. Viruses rule the waves—the smallest and most abundant members of marine ecosystems. Microbiol Today. 2000;27:171–173. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frede T. Thingstad elements of a theory for the mechanisms controlling abundance, diversity, and biogeochemical role of lytic bacterial viruses in aquatic systems. Limnol Oceanogr. 2000;45(6):1320–1328. doi: 10.4319/lo.2000.45.6.1320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang SC, Paul JH. Gene transfer by transduction in the marine environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64(8):2780–2787. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2780-2787.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felts AF, Breitbart MB, Salamon P, Edwards R, et al. The marine viromes of four oceanic regions. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(11):e368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinbauer MG. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Mircobiol Rev. 2004;28:127–181. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewson I, Barbosa JG, Brown JM. Temporal dynamics and decay of putatively allochthonous and autochthonous viral genotypes in contrasting freshwater lakes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(18):6583–6591. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01705-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montanié H, et al. Potential effect of freshwater virus on the structure and activity of bacterial communities in the Marennes-Oléron Bay (France) Microb Ecol Febr. 2009;57(2):295–306. doi: 10.1007/s00248-008-9428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Promoting IWRM and fostering transboundary dialogue in central asia. Report. 2010.

- 14.Roux S, et al. Ecology and evolution of viruses infecting uncultivated SUP05 bacteria as revealed by single-cell- and meta-genomics. eLife. 2014;3:e03125. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer F, et al. The metagenomics RAST server—a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:386. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez-Alvarez V, et al. Systematic artifacts in metagenomes from complex microbial communities. ISME J. 2009;3:1314–1317. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox MP, et al. SolexaQA: at-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:485. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rho M, et al. FragGeneScan: predicting genes in short and error-prone reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(20):e191. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kent WJ. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12(4):656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cairns J, et al. Phage and the origins of molecular biology. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohwer F, Thurber RV. Viruses manipulate the marine environment. Nature. 2009;459:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nature08060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suttle CA. Marine viruses—major players in the global ecosystem. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:801–812. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilhelm SW, Suttle CA. Viruses and nutrient cycles in the sea. Bioscience. 1999;49:781–788. doi: 10.2307/1313569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sano E, et al. Movement of viruses between biomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:5842–5846. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5842-5846.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson EJ, et al. Cholera transmission: the host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:693–702. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reyes A, et al. Viruses in the faecal microbiota of monozygotic twins and their mothers. Nature. 2010;466:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nature09199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rho M, et al. Diverse CRISPRs evolving in human microbiomes. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohiuddin M, Schellhorn HE. Spatial and temporal dynamics of virus occurrence in two freshwater lakes captured through metagenomic analysis. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:00960. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Binga EK, Lasken RS, Neufeld JD. Something from (almost) nothing: the impact of multiple displacement amplification on microbial ecology. ISME J. 2008;2:233–241. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drucker V, Dutova N. Bacteriophages from the Barguzin River and Barguzin Bay of Lake Baikal. Proc Irkutsk State Univ Ser Earth Sci. 2012;2:P111–P115. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Map of the Ile-Balkhash region. Ile-Balkhash region is marked by a yellow square (TIFF 1823 kb)

Lake Balkhash – place of collection point of water samples. Sample site on the Lake Balkhash is marked by a red flag (TIFF 2620 kb)

The Kapchagay water reservoir–place of collection point of water samples. Sample site on the Kapchagay water reservoir is marked by a red flag (TIFF 2450 kb)

River Ile – place of collection point of water samples. Sample site on the River Ile is marked by a red flag (TIFF 2748 kb)