Abstract

Background

Revised breast cancer screening guidelines have fueled debate about the effectiveness and frequency of screening mammography, encouraging discussion between women and their providers.

Objective

To examine whether primary care providers’ (PCPs’) beliefs about the effectiveness and frequency of screening mammography are associated with utilization by their patients.

Design

Cross-sectional survey data from PCPs (2014) from three primary care networks affiliated with the Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) consortium, linked with data about their patients’ mammography use (2011–2014).

Participants

PCPs (n = 209) and their female patients age 40–89 years without breast cancer (n = 30,233).

Main Measures

Outcomes included whether (1) women received a screening mammogram during a 2-year period; and (2) screened women had >1 mammogram during that period, reflecting annual screening. Principal independent variables were PCP beliefs about the effectiveness of mammography and their recommendations for screening frequency.

Key Results

Overall 65.2% of women received >1 screening mammogram. For women 40–48 years, mammography use was modestly lower for those cared for by PCPs who believed that screening was ineffective compared with those who believed it was somewhat or very effective (59.1%, 62.3%, and 64.7%; p = 0.019 after controlling for patient characteristics). Of women with PCPs who reported they did not recommend screening before age 50, 48.1% were nonetheless screened. For women age 49–74 years, the vast majority were cared for by providers who believed that screening was effective. Provider recommendations were not associated with screening frequency. For women ≥75 years, those cared for by providers who were uncertain about effectiveness had higher screening use (50.7%) than those cared for by providers who believed it was somewhat effective (42.8%). Patients of providers who did not recommend screening were less likely to be screened than were those whose providers recommended annual screening, yet 37.1% of patients whose providers recommended against screening still received screening.

Conclusions

PCP beliefs about mammography effectiveness and screening recommendations are only modestly associated with use, suggesting other likely influences on patient participation in mammography.

KEY WORDS: mammography, variation in care, provider beliefs

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade there have been several well-publicized revisions to national breast cancer screening guidelines.1 – 4 These updates have re-invigorated both professional and lay debate about the effectiveness of screening mammography and how often women should be screened.5 – 7 For many women, these guidelines accentuate the importance of patient–provider discussion of individual screening harms and benefits.

Most studies of self-reported use of mammography in the initial years following the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPTSF) recommendations have not demonstrated the less frequent use or later initiation of routine screening called for by the USPSTF,8 , 9 although a registry-based study documented a decline in use.10 Surveys of primary care providers (PCPs) have examined whether changes in guidelines have influenced provider beliefs about screening effectiveness and their recommendations for screening;11 , 12 the majority of PCPs report that they believe screening mammography is effective in reducing breast cancer mortality for women ages 40–74 years, and they have not implemented less frequent screening, in part because of patient concerns.11 , 12

Conceptual models hypothesize that variation in the use of cancer screening occurs at multiple health system levels, including organizations, practices, providers, and patients.13 , 14 While earlier studies suggest that provider demographic characteristics influence screening use (e.g., patients of female providers may receive more mammography15 , 16), to our knowledge, no US studies have examined whether PCP beliefs about the effectiveness of and recommendations for mammography screening are associated with actual use by their patients. A study from Denmark, where invitations for mammography are managed centrally and PCPs are not directly involved in the breast cancer screening process, found that women in the panels of providers with a “positive” attitude about breast cancer screening were more likely to receive screening than those in the panel of a PCP with a more “negative” attitude.17 Understanding the multi-level influences on the use of cancer screening is critical for designing interventions to improve evidence-based screening. Further, as PCP recommendations are thought to be important in patient decisions, we sought to explicitly describe this relationship.

In this study, we linked survey data from PCPs to the utilization data of their patients to directly examine the association of provider beliefs about mammography effectiveness and recommendations for screening frequency with screening utilization.

METHODS

Overview

This study was conducted as part of the NCI-funded Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) consortium.18 The overall aim of PROSPR is to conduct multi-site, coordinated, trans-disciplinary research to evaluate and improve cancer screening processes. In 2014, we conducted a survey of PCPs affiliated with the three primary care networks of the PROSPR breast cancer research centers (response rate 57.6%) to ascertain provider beliefs about the effectiveness of mammography and their recommendations for screening.11 Resident physicians were excluded. These data were linked to the screening utilization data for the patients of participating PCPs for the period from 2011 to 2014, obtained from PROSPR’s central data repository. All sites received institutional review board approval for active or passive consent processes or a waiver of consent to enroll participants, link data, and perform analyses.

Settings and Study Population

Women were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were 40–89 years of age, without a known diagnosis of breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ, and had a primary care visit between January 1, 2011, and September 30, 2012, with a PCP affiliated with the clinical network of Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital (BWFH; Boston, MA), Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System (DH; Lebanon, NH), or the University of Pennsylvania (PENN; Philadelphia, PA). This time frame was chosen to ensure that most women had 2 years of follow-up in the data repository. One of the provider networks (PENN) was limited to only 18–24 months of follow-up to observe screening mammograms after the PCP visit.

Data and Covariates

Provider-level data were obtained from the survey, which ascertained information about provider demographic and practice characteristics, including age, gender, specialty (family or general practice, general internal medicine, gynecology, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, certified nurse midwives, other), medical school affiliation, number of outpatient office visits in a typical week, number of physicians at their practice, whether during the prior 12 months they had their clinical income adjusted based on their breast cancer screening performance, whether they had ever been sued for failure to diagnose cancer, and whether their primary practice had received NCQA recognition as a medical home.

Also derived from the survey were the principal independent variables: provider beliefs concerning screening mammography effectiveness, and their recommendations for screening frequency. Survey questions about screening beliefs and recommendations were assessed by specific age groups (i.e., 40–49 years, 50–74 years, and ≥75 years), because guideline recommendations for screening vary by patient age. For each age group, PCPs were asked the following: (1) How effective do you believe screening mammography is for reducing cancer mortality for average-risk women? (response options: very effective, somewhat effective, not effective, effectiveness not known, I am not sure); and (2) How often do you recommend screening mammography for most asymptomatic, average-risk women (in good health for their age)? (response options: every year (12 months), every other year (24 months), I discuss interval options with patients, I do not routinely recommend).

Patient-level data were obtained from PROSPR’s central data repository including age (categorized as 40–48 years, 49–74 years, and ≥75 years to reflect guideline differences by age; 49-year-olds were included with the older group because they turned 50 before the end of the 2-year window), race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, mixed race/other), type of health insurance (commercial, Medicare, Medicaid, uninsured/medical assistance, other, or missing), and Charlson comorbidity score (0, 1, 2+).19 , 20

Survey data were linked to data from PROSPR’s central repository using a unique provider identification code. Of the 73,266 women in the PROSPR data repository meeting the eligibility criteria for this study, 30,233 (41.2%) linked to a PCP who had completed a survey.

Outcome Variables

Outcome variables were obtained from PROSPR’s central data repository and measured at the patient level, as follows: (1) whether a woman received a screening mammogram during the 2 years following a PCP visit; and (2) for women who received a screening mammogram, whether they received >1 mammogram during that period, reflecting the use of annual screening. A screening mammogram was defined as a mammogram coded by the radiology facility as being for screening; in addition, the woman did not have any prior imaging in the prior 3 months, to avoid inclusion of diagnostic mammograms.

Statistical Analyses

We performed logistic regression analyses of the two binary outcomes. Potential predictors were assessed using univariate and then multivariate analysis, adjusting for other significant factors. For the assessment of patient characteristics, we used a population-averaged generalized estimating equations (GEE) model to account for correlation among outcomes from the same PCP. To evaluate provider characteristics and beliefs we used GEE models adjusted for patient characteristics found to be significant in the patient-level GEE analyses. All models of provider characteristics and beliefs were adjusted for patient age, race/ethnicity, and insurance status as well as calendar year and primary care network (BWFH, DH, PENN). Additionally, for evaluating the first outcome of “any screening use” we adjusted for comorbidity. Significant provider variables were tested in a larger joint multivariate model. The absolute measurement of screening may have been reduced at PENN due to shorter follow-up than the other two sites. However, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding PENN (14% of the population), and there were no substantial differences. Thus, we report results for all three sites.

RESULTS

Description of the Provider Population and the Patients Under Their Care

Twenty-three percent of providers were under the age of 40 years; these younger providers cared for 13.2% of the study cohort (Table 1). The majority of providers were women, general internists, and had a medical school affiliation. About one-third noted that their clinical income was adjusted based on their performance of breast cancer screening; few reported that they had been sued for failure to diagnose cancer. Slightly over half reported that they practiced in an NCQA-recognized medical home, and about 80% said they practiced in either a hospital-based or community-based office.

Table 1.

Description of PCPs and Patients under their Care

| No. of providers (%) N = 209 | No. of patients (%) N = 30,233 | |

|---|---|---|

| Provider characteristics | ||

| Age: | ||

| < 40 years | 47 (23.2%) | 3953 (13.2%) |

| 40–49 years | 73 (36.0%) | 12,377 (41.3%) |

| 50–59 years | 43 (21.2%) | 7583 (25.3%) |

| 60+ years | 40 (19.7%) | 6087 (20.3%) |

| Female: | 136 (65.1%) | 23,972 (79.3%) |

| Provider specialty: | ||

| Family medicine (MD/DO) | 39 (18.7%) | 4906 (16.2%) |

| General internal medicine (MD/DO) | 138 (66.1%) | 22,108 (73.1%) |

| Gynecology (MD/DO) | 17 (8.1%) | 1430 (4.7%) |

| Physician assistant, nurse practitioner, certified nurse midwife | 11 (5.3%) | 811 (2.7%) |

| Other | 4 (1.9%) | 978 (3.2%) |

| Affiliated with a medical school | 185 (90.2%) | 28,081 (93.6%) |

| Typical week, no. of office visits: | ||

| ≤ 25 | 39 (19.2%) | 3720 (12.6%) |

| 26–50 | 56 (27.6%) | 8942 (30.2%) |

| 51–75 | 69 (34.0%) | 11,868 (40.1%) |

| 76+ | 39 (19.3%) | 5067 (17.1%) |

| During the past 12 months, clinical income was adjusted based on breast cancer screening: | ||

| Yes | 64 (31.5%) | 8357(28.3%) |

| No | 124 (61.1%) | 18,096 (61.3%) |

| Not sure | 15 (7.4%) | 3081 (10.4%) |

| Ever sued for failure to diagnose cancer | ||

| Yes | 15 (7.3%) | 2066 (6.9%) |

| Provider-reported practice characteristics | ||

| Clinical provider network | ||

| University of Pennsylvania | 79 (37.8%) | 4198 (13.9%) |

| Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System | 47 (22.5%) | 11,000 (36.9%) |

| Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital | 83 (39.7%) | 15,035 (49.7%) |

| National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)-recognized medical home: | ||

| Yes | 113 (55.4%) | 14,342 (48.1%) |

| Practice type: | ||

| Hospital-based office | 79 (38.9%) | 12,541 (41.8%) |

| Community-based office (not health center) | 89 (43.8%) | 11,888 (39.6%) |

| Community health center | 16 (7.9%) | 3140 (10.5%) |

| Other | 19 (9.4%) | 2417 (8.1%) |

| Number of physicians in practice: | ||

| < 5 | 21 (10.3%) | 3990 (13.3%) |

| 5–10 | 71 (34.8%) | 8343 (27.9%) |

| 11–20 | 65 (31.9%) | 10,550 (35.2%) |

| 21+ | 47 (23.0%) | 7057 (23.6%) |

Notes: Provider data were missing for age (n = 6 providers), number of office visits/week (6), performance reporting (12), sued for failure to diagnose cancer (8), practice in NCQA-recognized medical home (10), practice location (6), medical school affiliation (4), number of physicians in practice (10)

Provider Beliefs about Mammography Effectiveness and Patient Use

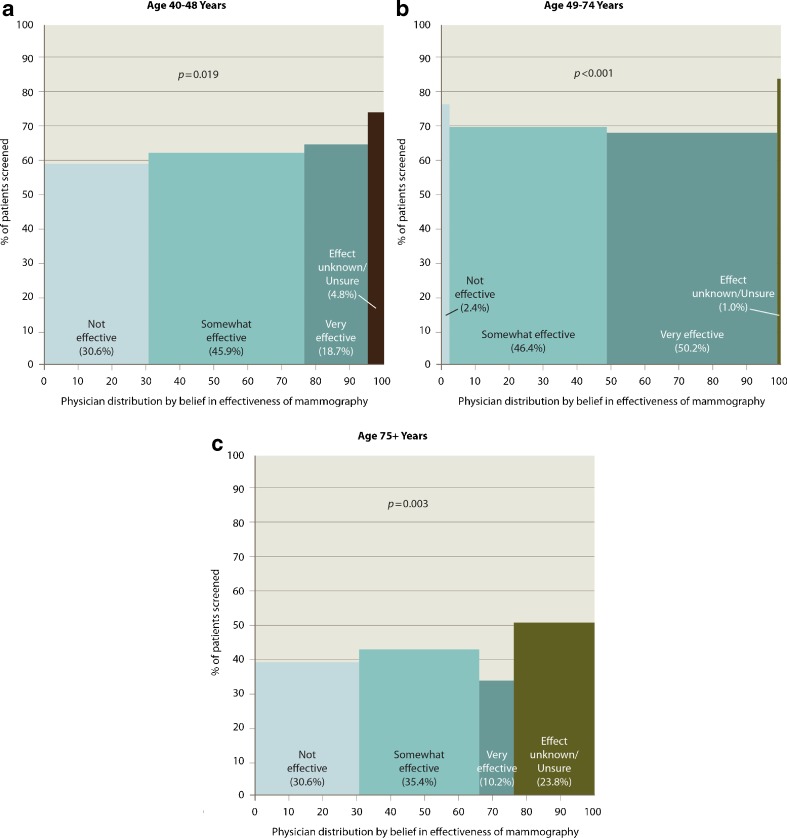

For women age 40–48 years, 30.6% of providers believed that mammography was not effective, 45.9% somewhat effective, 18.7% very effective, and 4.8% that effectiveness was not known or they were unsure about its effectiveness (Fig. 1a). Use of mammography was modestly lower among women cared for by providers who believed that screening was not effective (59.1%) than among those whose providers thought it was somewhat effective (62.3%). Women cared for by providers who were uncertain about mammography effectiveness had the highest use (74.2%). Differences in use by provider beliefs about effectiveness were significant (p = 0.019) after controlling for patient characteristics (Table 2). There was no overall association between provider beliefs about effectiveness and receipt of annual screening for this age group (Table 2), although those cared for by providers who thought that mammography was very effective (43.9%) were more likely to receive mammography than those cared for by a provider who thought it was somewhat effective (39.2%; p = 0.026).

Figure 1.

Association between provider beliefs about mammography effectiveness and use of screening by their patients, by age. a 40–48 years. b 49–74 years. c. 75+ years. Note: Figures show unadjusted rates and the adjusted p values.

Table 2.

Provider and Practice Characteristics Associated with Screening Use after Adjustment for Patient Factors

| Received a screening mammogram | Among those with a screening mammogram, received annual screening | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value* | OR | 95% CI | p value* | |

| Provider belief in effectiveness of screening mammography | ||||||

| Women age 40–48 years | 0.019 | 0.177 | ||||

| Not effective | 0.84 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.045 | 1.06 | 0.93–1.21 | 0.405 |

| Somewhat effective | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Very effective | 1.10 | 0.90–1.34 | 0.361 | 1.22 | 1.02–1.45 | 0.026 |

| Effectiveness not known/not sure | 1.46 | 0.97–2.22 | 0.073 | 1.05 | 0.81–1.37 | 0.703 |

| Women age 49–74 years | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Not effective | 1.15 | 0.93–1.41 | 0.207 | 1.05 | 0.87–1.27 | 0.616 |

| Somewhat effective | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Very effective | 0.94 | 0.76–1.16 | 0.540 | 0.94 | 0.83–1.06 | 0.296 |

| Effectiveness not known/not sure | 1.55 | 1.29–1.86 | <0.0001 | 0.72 | 0.63–0.84 | <0.0001 |

| Women age 75+ years | 0.003 | 0.632 | ||||

| Not effective | 0.81 | 0.54–1.20 | 0.284 | 0.92 | 0.62–1.35 | 0.659 |

| Somewhat effective | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Very effective | 0.63 | 0.38–1.03 | 0.065 | 0.66 | 0.35 -1.24 | 0.193 |

| Effectiveness not known/not sure | 1.36 | 1.00–1.86 | 0.053 | 0.95 | 0.69–1.32 | 0.765 |

| Provider recommendation for screening frequency | ||||||

| Women age 40–48 years | 0.164 | 0.157 | ||||

| Every year | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Every other year | 0.74 | 0.52–1.05 | 0.092 | 0.87 | 0.52–1.46 | 0.600 |

| Discuss interval options | 0.92 | 0.78–1.09 | 0.325 | 0.88 | 0.77 - 1.00 | 0.050 |

| Do not routinely recommend | 0.66 | 0.41–1.05 | 0.078 | 1.00 | 0.80–1.26 | 0.970 |

| Women age 49–74 years | 0.002 | 0.358 | ||||

| Every year | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Every other year | 1.59 | 1.19–2.13 | 0.002 | 1.12 | 0.91–1.37 | 0.290 |

| Discuss interval options | 1.48 | 1.09–2.02 | 0.012 | 1.18 | 0.94–1.47 | 0.153 |

| Women age 75+ years | 0.024 | 0.176 | ||||

| Every year | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Every other year | 0.69 | 0.43–1.12 | 0.136 | 1.05 | 0.56–1.98 | 0.874 |

| Discuss interval options | 0.86 | 0.53–1.40 | 0.557 | 0.89 | 0.50–1.58 | 0.679 |

| Do not routinely recommend | 0.56 | 0.35–0.89 | 0.014 | 0.69 | 0.38–1.25 | 0.216 |

| Provider characteristics | ||||||

| Provider gender | <0.0001 | 0.011 | ||||

| Male | 0.63 | 0.53–0.77 | <0.0001 | 0.87 | 0.78–0.97 | 0.011 |

| Female | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Provider specialty: | <0.0001 | 0.011 | ||||

| Family medicine (MD/DO) | 0.57 | 0.44–0.72 | <0.0001 | 0.83 | 0.71–0.96 | 0.012 |

| General internal medicine (MD/DO) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Gynecology (MD/DO) | 0.97 | 0.73–1.28 | 0.823 | 1.32 | 1.00–1.73 | 0.049 |

| Physician assistant, nurse practitioner, certified nurse midwife | 1.13 | 0.76–1.67 | 0.544 | 0.88 | 0.67–1.17 | 0.388 |

| Other | 0.71 | 0.41–1.22 | 0.212 | 1.00 | 0.72–1.37 | 0.991 |

| Affiliated with a medical school | 0.184 | 0.343 | ||||

| Yes | 1.32 | 0.88–1.98 | 0.184 | 1.10 | 0.85–1.41 | 0.343 |

| No | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| During the past 12 months, clinical income was adjusted based on breast cancer screening | 0.152 | 0.812 | ||||

| Yes | 1.42 | 0.97–2.06 | 0.068 | 0.96 | 0.75–1.23 | 0.755 |

| No | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Not sure | 1.40 | 0.97–2.02 | 0.073 | 1.04 | 0.83–1.31 | 0.732 |

| Ever sued for failure to diagnose cancer | 0.919 | 0.602 | ||||

| Yes | 1.01 | 0.86–1.18 | 0.919 | 1.04 | 0.89–1.22 | 0.602 |

| No | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Provider-reported practice characteristics | ||||||

| National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)-recognized medical home | 0.398 | 0.117 | ||||

| Yes | 0.93 | 0.77–1.11 | 0.398 | 0.88 | 0.75–1.03 | 0.117 |

| No | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Practice type: | 0.0008 | 0.028 | ||||

| Hospital-based office | 1.40 | 1.16–1.68 | 0.0003 | 1.10 | 1.00–1.22 | 0.054 |

| Community-based office (not health center) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Community health center | 1.57 | 1.22–2.02 | 0.0004 | 1.03 | 0.85–1.24 | 0.784 |

| Other | 1.39 | 1.11–1.74 | 0.0044 | 1.06 | 0.87–1.29 | 0.555 |

Notes: OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

* First p value for each characteristic is for the overall difference among the categories of that variable and is based on the score test from the GEE model. All subsequent p values reflect the comparison of that particular value to the referent category and are based on the Wald test from the GEE model.

GEE models account for clustering of patients within primary care provider. Models adjust for all patient covariates (age, race/ethnicity, insurance status, Charlson comorbidity score, calendar year, and clinical provider network) except where noted due to small numbers in some models; provider characteristics were then added individually to these models. Models of 2+ vs. 1 screen did not include Charlson scores. Individuals with missing values for Charlson score or race were excluded. Those with missing insurance status were designated as a separate category and included unless the number of unknowns was too small to be modeled. For the models in women 75 or older, insurance and race were not included due to small numbers

For women age 49–74 years, more providers believed that mammography was very effective (50.2%), and few believed that mammography was not effective (2.4%) (Fig. 1b). Women who were cared for by providers who were uncertain about mammography effectiveness had the highest use of mammography (84.0%). Differences in use by provider beliefs about effectiveness were significant (p < 0.0001) after controlling for patient characteristics. In contrast to the use of any screening, women cared for by providers who were uncertain of mammography effectiveness were least likely to receive annual screening.

For women age 75 years and older, fewer providers believed that mammography was very effective compared with the younger groups; 30.6% indicated that mammography was not effective, and 23.8% were unsure about its effectiveness (Fig. 1c). Again, the use of mammography was highest among patients cared for by providers who were uncertain about mammography effectiveness (50.7%). Differences in use by provider beliefs about effectiveness were significant (p = 0.003) after controlling for patient characteristics. There was no association between provider beliefs about effectiveness and receipt of annual screening for this age group.

PCP Recommendations for Mammography Frequency and Patient Use

For women age 40–48 years, 30.6% of providers recommended yearly screening, 6.2% recommended biennial screening, 55.0% discussed interval options with the patient, and 8.1% did not routinely recommend screening (Fig. 2a). There was no association between providers’ recommended screening intervals and use of screening or use of annual screening (Table 2). Of note, mammography use among women cared for by providers who recommended yearly screening (64.4%) was similar to that among those cared for by providers who discussed frequency options (63.6%); almost half of women cared for by providers who did not recommend screening in this age group received a mammogram.

Figure 2.

Association between provider recommendations for frequency of screening and use of screening by their patients, by age. a. 40–48 years. b. 49–74 years. c. 75+ years. Note: Figures show unadjusted rates and the adjusted p values.

For women age 49–74 years, more providers recommended yearly screening compared with the younger group, and fewer (14.0%) discussed interval options with women. No women were cared for by providers who did not routinely recommend screening for women in this age group (Fig. 2b). Differences in use by provider recommendations for screening frequency were significant although modest in absolute difference (p = 0.002). There were no differences in provider recommendations for screening frequency and use of annual screening.

For women age 75 years and older, providers most commonly discussed frequency options with their patients or did not recommend screening (Fig. 2c). Mammography use was highest among women whose providers recommended yearly screening (52.9%) and lowest among women cared for by providers who did not routinely recommend screening in this age group. Nevertheless, 37.1% of women whose providers reported they did not routinely recommend screening for this age group received a mammogram. Differences in use by provider recommendations for screening frequency were significant (p = 0.024). There was no association between providers’ recommended screening intervals and receipt of annual screening (Table 2).

Provider Characteristics and Screening Use

In models that adjusted for patient and provider characteristics (Table 2), patients of male providers were less likely than patients of female providers to receive a mammogram (odds ratio [OR] 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.53–0.77) or annual screening (0.87; 0.78–0.97). Patients of family physicians were less likely than those of general internists, gynecologists, or mid-level providers to receive screening mammography or annual screening. Neither performance measurement for breast cancer screening nor history of being sued for failure to diagnose cancer were associated with screening use. There also was no association with provider-reported NCQA-recognized medical home status, but women of providers who practiced in a hospital-based office or a community health center were more likely to receive mammography screening than those whose providers practiced in a community-based office.

Use of Screening Mammography by Patient Characteristics

Overall, 65.2% of women received at least one screening mammogram during the 2-year study period (Table 3). Screening was higher among younger women than those 75 years and older. Hispanic women received screening mammograms at a higher rate than other racial/ethnic groups. Women with commercial insurance received screening at a higher rate than uninsured women and those with public insurance. Screening use was lowest for women with a Charlson score of 2+. In the GEE model of patient factors associated with any screening use, age, race/ethnicity, insurance, comorbidity, and provider network were statistically significant. Among women who were screened, 49.0% received mammography annually. Patterns of annual screening were similar to any use of screening, except that black women were less likely than white or Hispanic women to receive annual screening, women with Medicare were more likely to receive annual screening than were women with commercial insurance, and there was no association with comorbidity. In the GEE model of patient factors associated with annual screening, the associations between age, race/ethnicity, insurance, and provider network were statistically significant.

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics Associated with the Use of Screening Mammography and Receipt of Annual Screening

| Characteristic | Had a screening mammogram | Among those with a screening mammogram, received annual screening | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible (N) | Screened (N) | % Screened of eligible | Adj. OR | 95% CI | Annual screen (N) | % Annual screen of those screened | Adj. OR | 95% CI | |

| Overall | 30,233 | 19,715 | 65.2% | 9659 | 49.0% | ||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 40–48 | 11,045 | 6888 | 62.4% | 1.00 | Referent | 2831 | 41.1% | 1.00 | Referent |

| 49–74 | 17,229 | 11,971 | 69.5% | 1.31 | 1.20–1.42 | 6366 | 53.2% | 1.39 | 1.29–1.50 |

| 75–87 | 1959 | 856 | 43.7% | 0.49 | 0.41–0.59 | 462 | 54.0% | 1.26 | 1.05–1.50 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 2298 | 1780 | 77.5% | 1.87 | 1.55–2.26 | 891 | 50.1% | 1.01 | 0.88–1.17 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 22,196 | 14,194 | 64.0% | 1.00 | Referent | 7161 | 50.4% | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 3808 | 2465 | 64.7% | 1.23 | 1.08–1.40 | 1014 | 41.4% | 0.80 | 0.70–0.91 |

| Asian | 867 | 574 | 66.2% | 1.05 | 0.88–1.24 | 267 | 46.5% | 0.93 | 0.74–1.15 |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 37 | 19 | 51.4% | 0.56 | 0.31–1.02 | 12 | 63.3% | 1.74 | 0.73–4.15 |

| Mixed race/other | 249 | 137 | 55.0% | 1.02 | 0.80–1.29 | 48 | 35.0% | 0.89 | 0.64–1.24 |

| Insurance | |||||||||

| Medicaid | 1204 | 690 | 57.3% | 0.68 | 0.59–0.79 | 242 | 35.1% | 0.68 | 0.57–0.81 |

| Medicare | 5230 | 3052 | 58.4% | 0.82 | 0.77–0.89 | 1697 | 55.6% | 1.16 | 1.06–1.27 |

| Commercial | 21,160 | 14,383 | 68.0% | 1.00 | Referent | 6991 | 48.6% | 1.00 | Referent |

| Other | 628 | 424 | 67.5% | 1.00 | 0.83–1.21 | 215 | 50.7% | 0.98 | 0.82–1.17 |

| Uninsured/medical assistance | 1838 | 1139 | 62.0% | 0.56 | 0.48–0.64 | 513 | 45.0% | 0.75 | 0.66–0.86 |

| Unknown | 173 | 27 | 15.6% | 0.15 | 0.10–0.23 | 1 | 3.7% | 0.08 | 0.01–0.56 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||||||||

| 0 | 22,736 | 15,033 | 66.1% | 1.00 | Referent | 7362 | 49.0% | Not included | |

| 1 | 4430 | 2899 | 65.4% | 0.92 | 0.86–1.00 | 1431 | 49.4% | ||

| 2+ | 2991 | 1734 | 58.0% | 0.66 | 0.59–0.75 | 862 | 49.7% | ||

| Clinical provider network | |||||||||

| University of Pennsylvania | 4198 | 2246 | 53.5% | 1.00 | Referent | 744 | 33.1% | 1.00 | Referent |

| Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System | 11,000 | 6485 | 59.0% | 1.11 | 0.87–1.40 | 3119 | 48.1% | 1.08 | 0.88–1.31 |

| Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital | 15,035 | 10,984 | 73.1% | 1.96 | 1.62–2.39 | 5796 | 52.8% | 1.47 | 1.21–1.78 |

Notes: OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval for the OR

Odds ratios adjust for all patient factors shown in the table. GEE models account for clustering of patients by primary care provider. Model of screening use adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, insurance status, Charlson comorbidity score, calendar year, and clinical provider network. Model of multiple screening use adjusted for same covariates, except Charlson comorbidity score was not included. Patient data were missing for race/ethnicity (n = 778 patients), and Charlson score (76)

DISCUSSION

The effectiveness of screening mammography and the appropriate screening frequency among women of different age groups continues to fuel policy, clinical, and public discourse.1 – 7 While prior studies have examined physicians’ beliefs about mammography effectiveness,11 , 12 to our knowledge, no US studies have directly linked data on PCP beliefs and recommendations to actual utilization by their patients. We found that provider beliefs about mammography effectiveness and recommendations for screening were only modestly associated with use. We found evidence of substantial use even among women of providers who did not routinely recommend mammography screening for certain age groups. For average-risk women in their 40s, the USPSTF recommends that providers and patients engage in informed decision-making.3 Although the majority of providers in our study report that they practice informed decision-making with women in this age group, screening rates were similar to those observed among women whose providers recommended yearly screening. Importantly, almost half of women in their 40s who were seen by providers who reported that they did not routinely recommend screening still received mammography, and we observed a lack of association between provider recommendations for screening frequency and annual screening for women in all age groups. We also found that patients of providers who were unsure about the effectiveness or frequency of mammography were more likely to be screened, suggesting that patient preference may play a larger role in screening use when providers are uncertain. Importantly, we did not find an association between such practice characteristics as NCQA medical home recognition or the use of provider incentives and the use of screening. These findings suggest that evidence-based implementation of mammography screening may require practice tools and policies beyond those currently available for shared decision-making, including the broad dissemination of decision aids and perhaps centralized invitation and education for screening.

Our findings differ from those of a study of PCPs in solo practice in Denmark, where PCPs are not directly involved in ordering breast cancer screening because invitations to screening are managed centrally.17 Despite this more advisory role, the study suggested a positive relationship between a provider’s more positive attitude about screening and the decision to initiate screening after the age of 50. The difference in findings may be because the Danish study was focused on the decision to initiate screening, whereas ours was focused on the use and frequency of screening, as well as the important differences in how screening is implemented in the USA and Denmark.

Understanding multi-level influences on the use of health care is critical to ensuring the delivery of evidence-based care.13 , 14 Mammography screening is an exemplar of this complexity. Our findings suggest that there may be important influences on personal screening decisions beyond discussion with PCPs or practice-level interventions to promote guideline-concordant screening. There are several potential reasons for these findings. PCPs may have limited time, skills, or tools for engaging in individualized discussions of the harms and benefits of screening.21 , 22 Thus, screening may become a default option, especially with electronic health record (EHR) clinical decision support prompting clinicians to screen. This work supports the need for better and more EHR-integrated tools for informed decision-making to help patients and providers discuss and consider the benefits and harms of screening, particularly for women in their 40s and those over the age of 75, where personal decision-making may be most important.23 – 26 Furthermore, there is a need for better EHR documentation of the occurrence of informed decision-making discussions. In addition to protocol reminders in EHRs for annual screening, recommendations and reminders to patients from radiology centers could also influence screening use.22 , 27 This underscores the importance of reconciling guideline recommendations for mammography across specialties and implementing systems for individualized screening reminders in EHRs. This work supports prior studies showing that provider demographic characteristics, particularly gender, may influence patients’ use of cancer screening, but are not dominant factors,15 , 16 and that financial productivity incentives are not associated with mammography use.28 Importantly, patient beliefs and behaviors may have a broader influence than the recommendations of a PCP. Social networks and the media likely influence women’s screening decisions.6 , 7

Strengths of this study include the use of multi-level data about patients, providers, and primary care practices. The study also has limitations. We did not survey patients about their screening beliefs or other influences on screening use, such as friends, family, or the media. We did not assess details of shared decision-making practices among PCPs. PCP survey data were not collected longitudinally, and provider beliefs and practices may be evolving. Although we examined patients and their PCPs from three primary care networks, these findings may not be generalizable to other health care settings or to US regions beyond the Northeast, where the attitudes of women and PCPs may differ. Despite these limitations, our paper has strengths beyond the diversity of practice networks. All patients saw their provider at least once, making it possible to discuss screening mammography. Because of our large sample, we were able to adjust for patient, provider, and practice characteristics.

PCP beliefs about the effectiveness of mammography and recommendations for screening frequency are only modestly associated with use. These results suggest that there are other important influences on women’s decisions to participate in screening mammography. Further elucidation of these factors may inform the development of tools to support shared decision-making that incorporate evidence about both the effectiveness and limitations of screening mammography, as well as patient values and preferences.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating PROSPR Research Centers for the data they provided for this study. A list of PROSPR investigators and contributing research staff is provided at: http://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/prospr/

This study was conducted as part of the National Cancer Institute-funded consortium, Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) (Grant numbers U54 CA163307, U54 CA163313, U54 CA163303, U01 CA163304).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727–737. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716-726, W-236. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Siu AL, Force USPST. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016.

- 4.Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk: 2015 Guideline Update From the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RA, Kerlikowske K, Miglioretti DL, Kalager M. Clinical decisions. Mammography screening for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):e31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMclde1212888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabin RC. For Women, a More Complicated Choice on Mammograms. New York Times. February 11, 2014.

- 7.How Often Do You Really Need a Mammogram? How much is too much? Many disagree, but with women’s best interests at heart. 2015; http://health.usnews.com/health-news/patient-advice/articles/2015/06/18/how-often-do-you-really-need-a-mammogram. Accessed Jun 1, 2016.

- 8.Dehkordy SF, Hall KS, Roach AL, Rothman ED, Dalton VK, Carlos RC. Trends in Breast Cancer Screening: Impact of U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pace LE, He Y, Keating NL. Trends in mammography screening rates after publication of the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. Cancer. 2013;119(14):2518–2523. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sprague BL, Bolton KC, Mace JL, et al. Registry-based Study of Trends in Breast Cancer Screening Mammography before and after the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations. Radiology. 2014;270(2):354–361. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas JS, Sprague BL, Klabunde CN, et al. Provider Attitudes and Screening Practices Following Changes in Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):52–59. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3449-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbelli J, Borrero S, Bonnema R, et al. Physician adherence to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force mammography guidelines. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(3):e313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onega T, Beaber EF, Sprague BL, et al. Breast cancer screening in an era of personalized regimens: a conceptual model and National Cancer Institute initiative for risk-based and preference-based approaches at a population level. Cancer. 2014;120(19):2955–2964. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zapka JG, Taplin SH, Solberg LI, Manos MM. A framework for improving the quality of cancer care: the case of breast and cervical cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(1):4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lurie N, Slater J, McGovern P, Ekstrum J, Quam L, Margolis K. Preventive care for women. Does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;329(7):478–482. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308123290707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Harris R, Kobrin SC, Skinner CS. Are patients of women physicians screened more aggressively? A prospective study of physician gender and screening. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(3):119–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02599664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen LF, Mukai TO, Andersen B, Vedsted P. The association between general practitioners’ attitudes towards breast cancer screening and women’s screening participation. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:254. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaber EF, Kim JJ, Schapira MM, et al. Unifying screening processes within the PROSPR consortium: a conceptual model for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv120. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabatino SA, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS, Burns RB. Breast cancer risk assessment and management in primary care: provider attitudes, practices, and barriers. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31(5):375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schapira MM, Sprague BL, Klabunde CN, et al. Inadequate Systems to Support Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening in Primary Care Practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1148–55. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3726-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schonberg MA, Walter LC. Talking about stopping cancer screening—not so easy. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):532–533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schonberg MA, Hamel MB, Davis RB, et al. Development and evaluation of a decision aid on mammography screening for women 75 years and older. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):417–424. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schonberg MA, Breslau ES, McCarthy EP. Targeting of mammography screening according to life expectancy in women aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):388–395. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seitz HH, Gibson L, Skubisz C, et al. Effects of a risk-based online mammography intervention on accuracy of perceived risk and mammography intentions. Patient Educ Couns. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.ACR and SBI Continue to Recommend Regular Mammography Starting at Age 40. 2015; http://www.acr.org/About-Us/Media-Center/Press-Releases/2015-Press-Releases/20151020-ACR-SBI-Recommend-Mammography-at-Age-40. Accessed June 3, 2016.

- 28.Wee CC, Phillips RS, Burstin HR, et al. Influence of financial productivity incentives on the use of preventive care. Am J Med. 2001;110(3):181–187. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]