Abstract

Background

There is a need for screening and brief assessment instruments to identify primary care patients with substance use problems. This study’s aim was to examine the performance of a two-step screening and brief assessment instrument, the TAPS Tool, compared to the WHO ASSIST.

Methods

Two thousand adult primary care patients recruited from five primary care clinics in four Eastern US states completed the TAPS Tool followed by the ASSIST. The ability of the TAPS Tool to identify moderate- and high-risk use scores on the ASSIST was examined using sensitivity and specificity analyses.

Results

The interviewer and self-administered computer tablet versions of the TAPS Tool generated similar results. The interviewer-administered version (at cut-off of 2), had acceptable sensitivity and specificity for high-risk tobacco (0.90 and 0.77) and alcohol (0.87 and 0.80) use. For illicit drugs, sensitivities were ≥0.82 and specificities ≥0.92. The TAPS (at a cut-off of 1) had good sensitivity and specificity for moderate-risk tobacco use (0.83 and 0.97) and alcohol (0.83 and 0.74). Among illicit drugs, sensitivity was acceptable for moderate-risk of marijuana (0.71), while it was low for all other illicit drugs and non-medical use of prescription medications. Specificities were 0.97 or higher for all illicit drugs and prescription medications.

Conclusions

The TAPS Tool identified adult primary care patients with high-risk ASSIST scores for all substances as well moderate-risk users of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana, although it did not perform well in identifying patients with moderate-risk use of other drugs or non-medical use of prescription medications. The advantages of the TAPS Tool over the ASSIST are its more limited number of items and focus solely on substance use in the past 3 months.

Keywords: Substance abuse screening, substance abuse assessment, primary care, ASSIST

1. Introduction

In recognition of the health problems associated with substance use and the need for an efficient approach to screen and assess substance-using individuals in primary care settings, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (WHO ASSIST Working Group, 2002). The ASSIST consists of seven questions regarding each of 10 classes of substances and a question about drug injection. Items cover lifetime use and frequency of use in the past-3 months as well as various problems associated with the use of these substances. The ASSIST was found to have good concurrent, construct, and discriminant validity among a sample of 1,047 primary care and drug treatment patients in six countries spanning five continents (Humeniuk et al., 2008). Substance-specific involvement scores were developed to separate respondents into low-, moderate-, and high-risk categories for each substance. In developing the ASSIST, it was thought that the moderate-risk category, in particular, would help to identify individuals who otherwise might go undetected in health care settings (Humeniuk et al., 2008), while those with high risk scores were appropriate for referral to specialist addiction treatment services. A moderate-level substance risk score on the ASSIST was subsequently used as an inclusion criterion in a multi-site study of brief intervention in primary care (Humeniuk et al., 2012), that demonstrated the utility of the ASSIST in providing actionable data to triage patients to particular interventions.

Although the ASSIST has subsequently been studied across a variety of diverse populations, including adults with first-episode psychosis (Hides et al., 2009) and adolescents (Gryczynski et al., 2014), its widespread implementation has been hampered by the instrument’s length (requiring 5 to 15 minutes to administer) and complex scoring system (Ali et al., 2013; McNeely et al., 2014). In order to overcome these barriers to adoption, a computerized version of the full ASSIST that can be self-administered and scored automatically has been developed (Kumar, Cleland, Gourevitch et al., 2016; McNeely et al., 2016; Wolf & Shi, 2015). In addition, Ali and colleagues (2013) developed a short version of the ASSIST, termed the ASSIST-Lite, based on factor and item-response theory analyses of pooled data from previous validation studies of the ASSIST. This shortened version of the ASSIST has 3 items each for tobacco, cannabis, stimulants, sedatives, and opioids and 4 items for alcohol. The first item for each substance asks about any use in the past 3 months. Individuals who respond ‘yes’ to use of a substance are administered two (or for alcohol, three) subsequent items specific to that substance. For tobacco, the two items were drawn from the Heaviness of Smoking Index (Diaz et al., 2005) and the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire (Tate & Schmitz, 1993), not the original ASSIST, and ask if the respondent smoked 10 or more cigarettes/day and if they smoked within 30 minutes of waking. For the non-tobacco substances, the items are drawn from the ASSIST and vary depending on the substance. These items query loss of control (alcohol and opioids), concern expressed by others (alcohol, opioids, cannabis, sedatives, stimulants), urge to use (cannabis and sedatives), and frequency of using (i.e., weekly or greater; stimulants). Participants reporting use of alcohol receive an additional item that asks about frequency of having 4 (for women) or 5 (for men) more drinks on a single occasion. Scoring was also simplified such that a score of 2 or greater for all substances except alcohol (which required a score of 3) yielded an acceptable level of diagnostic accuracy for identifying DSM-IV substance dependence.

The National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network launched a multi-site trial examining the validity of a two-step screening and brief assessment for substance use termed the Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription medication, and other Substance use (TAPS) Tool among 2,000 adults enrolled in five primary care clinics across 4 states in the Eastern US (McNeely et al., 2016). The TAPS Tool is a two-step screening (TAPS-1) and brief assessment (TAPS-2) instrument. The TAPS-1 was adapted from the NIDA Quick Screen v 1.0 (NIDA, 2016) and the TAPS-2 was based on the ASSIST-Lite (Ali et al., 2013) and modified for the US context (as described below). The TAPS Tool in both self-administered tablet computer (iPad) and interviewer-administered versions was compared to a number of criterion measures, including the DSM-5 SUD criteria, the AUDIT-C, Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire, and the ASSIST (Wu et al., 2016). The primary analysis of the trial examined the performance of the TAPS Tool using the DSM-5 criteria as the gold standard (McNeely et al., 2016). The present paper is the first report on the concurrent validity of a modified version of the ASSIST-lite (i.e., the TAPS Tool) relative to the ASSIST.

2. Methods

The study’s methods have been reported in detail elsewhere (Wu et al., 2016). In brief, 2,000 adult primary care patients participated from August 2014–April 2015 at five primary care sites in four Eastern US states, including a Federally Qualified Health Center in Baltimore, MD, two practices in Kannapolis, NC, a public hospital clinic in New York City, and a University-based primary care clinic in Richmond, VA (McNeely et al., 2016). Eligibility criteria were intentionally broad and included being a primary care patient of at least 18 years of age and being at the clinic for a medical visit on the day of recruitment. Patients who did not understand spoken English, were physically unable to use the iPad, or had already participated in the study were excluded. Willing patients meeting eligibility criteria provided verbal informed consent to Research Assistants (RAs) after reviewing an IRB-approved consent form.

The order of administration of the self-administered tablet computer version or interviewer-administered TAPS Tool was determined by an electronic data capture system, which randomized participants in a counterbalanced order, such that 50% of the participants were first administered the TAPS Tool by the RA followed by self-administration of the TAPS Tool on a tablet computer (iPad). In order to accommodate low-literacy patients, the tablet included an optional computer-assisted audio self-interview that read questions and response options out loud. The other 50% of the participants were administered the TAPS Tool in the reverse order. After both formats of the TAPS Tool were completed, the RA then administered criterion measures, including the ASSIST, to each participant. The RA provided participants with $20 after completion of the measures.

2.1 Measures

2.1.1 TAPS Tool

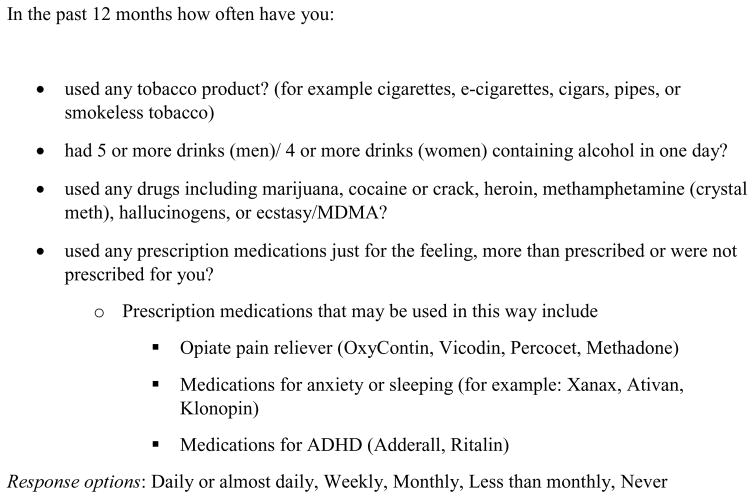

As shown in Figure 1, the TAPS-1 screen inquires about past 12-month frequency of four substance classes: tobacco, alcohol (binge drinking in excess of 5 drinks/day for men or 4 drinks/day for women); illicit drugs (including marijuana, cocaine methamphetamine, heroin); and non-medical use of prescription medications (including opioids, stimulants, and sedative-hypnotics). There are five possible response categories that range from “never” to “daily or almost daily.” Any response other than “never” is considered a positive screen and leads to administration of the TAPS-2.

Figure 1.

TAPS-1

The TAP-2 (shown in Figure 2), in contrast to the ASSIST and in keeping with the format of the ASSIST-Lite, has three items for each substance (four for alcohol) and a binary (yes/no) rather than an ordinal response format. The TAPS-2 was modified from the ASSIST-lite by adapting the ASSIST-lite for the US context by clarifying language (e.g., replacing cannabis with marijuana), replacing the Australian guideline of more than 4 drinks for both men and women with the NIAAA-recommended gender-specific variant (5+ for men and 4+ for women), and creating separate items for prescription opioids and prescription stimulants in order to separate them from their illicit counterparts (Wu et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

TAP-2 Items (Yes/No)

The TAPS-2 asks about past 3 month use of tobacco, alcohol, three classes of illicit drugs (marijuana, stimulants [cocaine, methamphetamine], and heroin), three classes of non-medical use of prescription medications (stimulants, opioids, and sedative-hypnotics), and ‘other’ drugs using a yes/no format. If the response is ‘no,’ the subsequent questions for that substance class are skipped. When the answer is ‘yes’ to any past 3 month use, the participant receives 2 follow-up items (3 for alcohol) specific to that substance class.

Possible scores on the TAPS Tool for tobacco and each class are 0, 1, 2 or 3. For alcohol, the possible scores are 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 (0 = no use; 1 = use but no problems; >1 = use plus one addition point for each problem per substance). Because the parent study was planned to assess the validity of the complete TAPS tool, which is the combination of TAPS-1 and TAPS-2, participants were asked to respond to all TAPS-2 questions even if their answers on the TAPS-1 indicated no use in the prior 12 months. If the participant indicated never using a substance in the past 12 months on TAPS-1, but reported use in the past 3 months on TAPS-2, the combined TAPS Tool score is 0 for the present analysis (because when the TAPS Tool will be used in clinical practice, patients denying use in the past 12 months on the TAPS-1 would not be administered the TAPS 2). Otherwise the combined TAPS Tool score is the TAPS-2 score.

2.2 Criterion Measure: ASSIST Version 3.0

The ASSIST 3.0 (Humeniuk et al., 2008) consists of seven questions that are scored for each of 10 drug classes (tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens, opioids, and other drugs). In addition, an eighth question (unscored) inquires about injection drug use. Only those who endorse any lifetime use in the first question for each substance category are then asked subsequent items for that substance. Questions 2 through 5 refer to the past 3-month period for each substance category and include questions on the frequency of use, cravings, problems associated with use, and failure to fulfill normal role expectations. Response categories for these items are: never, once or twice only, monthly, weekly, and daily/almost daily. Questions 6 and 7 (regarding others expressing concern over the patient’s use of the substance and the patient’s inability to control or stop using) are trinary items (Never; Yes, but not in the past 3 months; and Yes, in the past 3 months). The substance-specific score is obtained by adding the item scaling weights (as per the WHO scoring manual) on items 2 through 7 (WHO, 2016). Substance-specific scores (except for alcohol) are divided into low (0–3), moderate (4–26), and high risk (≥27). Alcohol risk categories are low (0–10), moderate (11–26), and high (≥27).

2.3 Statistical Analysis

This study reports a preplanned secondary analysis from a multi-site study whose primary aim was to examine the TAPS Tool vs. the DSM-5 SUD criteria (McNeely et al., 2016). In this secondary analysis, the TAPS Tool substance specific scores for those participants who were positive on the TAPS-1 screen, were compared to ASSIST substance specific involvement scores corresponding to moderate-risk and high-risk use, with the ASSIST serving as the reference standard measure. Because the TAPS-2, in contrast to the ASSIST-lite, separates the items for prescription stimulants and illicit stimulants (cocaine and methamphetamine) and the prescription opioids and heroin, analyses were conducted for each of the TAPS-2 items separately and then by combining illicit and prescription and illicit stimulants into a stimulant category and prescription opioids and heroin into an opioid category. Interviewer-administered and self-administered tablet computer versions of the TAPS-2 were examined. Sensitivity, specificity, and the positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) were calculated. The sensitivity and the specificity represent the proportion of patients whose ASSIST severity score categories (high risk or moderate risk and above) were correctly identified by the TAPS Tool cut-points and the proportion of patients who do not have a moderate or high risk ASSIST score and who have a negative TAPS Tool score (i.e., below the cut-points) respectively. The PPV represents the proportion of patients above the cut-points on the TAPS Tool who had a high or moderate risk and above score on the ASSIST, while the NPV shows the proportion of patients who test negative on the TAPS tool who do not have a high or moderate risk or above score on the ASSIST. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were computed and the area under each curve (AUC) was examined (Hanley & McNeil, 1982). The cut-point on the TAPS Tool was based on maximizing the AUC. In some cases (as shown in Table 2 and 3), in which the AUCs were quite similar but the marginally higher value would have resulted in a different cut-point than the other substances, the cut-point matching the other substances was chosen in order to simplify interpretation of the test by primary care providers. Excellent discrimination was considered an AUC of >.90, good discrimination was considered an AUC of > 0.8, acceptable discrimination was considered >0.7, while an AUC of < 0.7 was considered poor discrimination (Hanley & McNeil, 1982). Wilson score 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all estimates and all analyses were conducted in SAS® version 9.3.

Table 2.

ASSIST Scores Frequencies, Categories of Use, Means (SD)

| Lifetime Use N (%) |

Past 3-month Use N (%) |

Low Risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance | ||||||

| Tobacco | 1474 (73.7%) | 840 (42.0%) | 1099 (55.0%) | 786 (39.3%) | 115 (5.8%) | 8.09 |

| Alcohol | 1793 (89.7%) | 1078 (53.9%) | 1717 (85.9%) | 214 (10.7) | 69 (93.5%) | 5.15 |

| Illicit Drugs | 1325 (66.3%) | 470 (23.5%) | 1437 (71.9%) | 478 (23.9%) | 85 (4.3%) | 4.24 |

| Prescription Drugs | 612 (30.6%) | 163 (8.2%) | 1764 (88.2%) | 192 (9.6%) | 44 (2.2%) | 1.77 |

| By Drug Class | ||||||

| Marijuana | 1257 (62.9%) | 350 (17.5%) | 1624(81.2%) | 349 (17.5%) | 27 (1.4%) | 2.60 |

| Illicit Stimulants | 754 (37.7%) | 129 (6.5%) | 1738 (86.9) | 229 (11.5%) | 33 (1.7%) | 1.74 |

| Heroin | 407 (20.4%) | 106 (5.3%) | 1818 (90.9%) | 142 (7.1%) | 39 (2.0%) | 1.41 |

| Prescription Opioids | 407 (20.4%) | 106 (5.3%) | 1818 (90.9%) | 142 (7.1%) | 39 (2.0%) | 1.41 |

| Sedatives | 329 (16.5%) | 80 (4.0%) | 1908 (95.4%) | 84 (4.2%) | 8 (0.4%) | 0.61 |

| Prescription Stimulants | 361 (18.1%) | 33 (1.7%) | 1944 (97.2%) | 52 (2.6%) | 4 (0.2%) | 0.38 |

| Other Drugs | 404 (20.2%) | 37 (1.9%) | 1953 (97.7%) | 42 (2.1%) | 5 (0.3%) | 0.32 |

| Combined Categories | ||||||

| Opioids (Heroin and Prescription Opioids) | 407 (20.4%) | 106 (5.3%) | 1818 (90.9%) | 142 (7.1%) | 39 (2.0%) | 1.41 |

| Stimulants (Cocaine, Methamphetamine, and Prescription Stimulants) | 754 (37.7%) | 129 (6.5%) | 1738 (86.9%) | 229 (11.5%) | 33 (1.7%) | 1.74 |

| Illicit Drugs Other than Marijuana | 831 (41.6%) | 223 (11.2%) | 1649 (82.5%) | 288 (14.4%) | 62 (3.1%) | 2.57 |

Table 3.

Interviewer-administered TAPS Tool v. ASSIST (N=2,000)

| Positive on ASSIST N (%) |

Positive on TAPS N (%) |

Sensitivity (95 % Wilson Score CI)1 | Specificity (95 % Wilson Score CI) | PPV2 (95 % Wilson Score CI) | NPV3 (95 % Wilson Score CI) | AUC4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Risk on the ASSIST5 (TAPS Cut-Point = 2) | |||||||

| Tobacco | 115 (0.06) | 533 (0.27) | 0.90 (0.83, 0.94) | 0.77 (0.75, 0.79) | 0.20 (0.17, 0.24) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.84 |

| Alcohol | 69 (0.03) | 449 (0.22) | 0.87 (0.77, 0.93) | 0.80 (0.78, 0.82) | 0.13 (0.10, 0.16) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.83 |

| Marijuana | 27 (0.01) | 190 (0.10) | 0.96 (0.81, 0.99) | 0.92 (0.91, 0.93) | 0.14 (0.10, 0.20) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.94 |

| Cocaine, meth | 33 (0.02) | 76 (0.04) | 0.94 (0.80, 0.98) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.41 (0.31, 0.52) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.96 |

| Rx stimulant | 4 (0.00) | 5 (0.00) | 0.25 (0.05, 0.70) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.20 (0.04, 0.62) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.62 |

| Total Stimulants (Cocaine, meth & Rx stimulant) | 33 (0.02) | 80 (0.04) | 0.94 (0.80, 0.98) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.39 (0.29, 0.50) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.96 |

| Heroin | 39 (0.02) | 46 (0.02) | 0.82 (0.67, 0.91) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.70 (0.56, 0.81) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.91 |

| Rx opioids | 39 (0.02) | 29 (0.01) | 0.41 (0.27, 0.57) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.55 (0.37, 0.71) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.70 |

| Total Opioids (heroin & Rx opioids) | 39 (0.02) | 61 (0.03) | 0.92 (0.79, 0.97) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.59 (0.46, 0.70) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.96 |

| Sedative | 8 (0.00) | 35 (0.02) | 0.63 (0.31, 0.87) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.14 (0.06, 0.29) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.80 |

| Moderate Risk6 or Higher on the ASSIST (TAPS Cut-Point = 1) | |||||||

| Tobacco | 901 (0.45) | 778 (0.39) | 0.83 (0.80, 0.85) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.87 (0.85, 0.89) | 0.90 |

| Alcohol | 283 (0.14) | 679 (0.34) | 0.83 (0.78, 0.87) | 0.74 (0.72, 0.76) | 0.34 (0.31, 0.38) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.78 |

| Marijuana | 375 (0.19) | 317 (0.16) | 0.71 (0.66, 0.75) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.84 (0.80, 0.88) | 0.93 (0.92, 0.94) | 0.84 |

| Cocaine, meth | 262 (0.13) | 102 (0.05) | 0.36 (0.30, 0.42) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.92 (0.85, 0.96) | 0.91 (0.90, 0.92) | 0.68 |

| Rx stimulant | 56 (0.03) | 12 (0.01) | 0.09 (0.04, 0.19) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.42 (0.20, 0.68) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.54 |

| Total Stimulants (Cocaine, meth & Rx stimulant) | 262 (0.13) | 111 (0.06) | 0.37 (0.31, 0.43) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.87 (0.79, 0.92) | 0.91 (0.90, 0.92) | 0.68 |

| Heroin | 181 (0.09) | 60 (0.03) | 0.31 (0.25, 0.38) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.93 (0.84, 0.97) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.95) | 0.65 |

| Rx opioids | 181 (0.09) | 70 (0.04) | 0.28 (0.22, 0.35) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.73 (0.62, 0.82) | 0.93 (0.92, 0.94) | 0.64 |

| Total Opioids (heroin & Rx opioids) | 181 (0.09) | 109 (0.05) | 0.48 (0.41, 0.55) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.79 (0.70, 0.86) | 0.95 (0.94, 0.96) | 0.73 |

| Sedative | 92 (0.05) | 55 (0.03) | 0.47 (0.37, 0.57) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.78 (0.65, 0.87) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.73 |

Notes. Rx=prescription, meth=methamphetamine. AUC for alcohol moderate risk or higher for a cut-off of 2 = 0.80.

Wilson Score CI = Wilson Score Confidence Intervals

PPV = Positive Predictive Value

NPV = Negative Predictive Value

AUC = Area Under the Curve

High Risk on the ASSIST for tobacco, alcohol and all drugs ≥ 27.

Moderate Risk on the ASSIST for tobacco and all drugs = 4 – 26; Moderate Risk for alcohol = 11–26.

3. Results

3.1 Participants

The demographic characteristics of the 2,000 participants are shown in Table 1. Their mean (SD) age was 46.0 (14.7) and 56.2% of the sample were women. Slightly more than half were African American (55.6%), a third were White (33.4%) and 11.7% were Hispanic. The lifetime and past three month frequencies of substance use and the ASSIST risk categories (low, medium, high) by substance are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (N=2,000)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n/%) | |

| Male | 874 (43.7%) |

| Female | 1124 (56.2%) |

| Other/Refused | 2 (0.1%) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 46.0 (14.7) |

| Ethnicity (n/%) | |

| Hispanic | 233 (11.7%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 1761 (88.1%) |

| Other/Refused | 6 (0.3%) |

| Race (n/%) | |

| White | 667 (33.4%) |

| African-American | 1112 (55.6%) |

| Asian | 35 (1.8%) |

| Multiracial | 66 (3.3%) |

| Other/Unknown/American Indian or Alaska Native | 113 (5.7%) |

| Refused | 7 (0.4%) |

3.2 Interviewer and Self-administered tablet computer versions

The mean (SD) time to complete the TAPS Tool interviewer-administered version was 2.39 (1.01) minutes and to complete the self-administered version was 4.47 (2.56) minutes. We did not assess the time to complete the ASSIST.

The optimal cut-points on the TAPS Tool for detecting “high risk” and “moderate risk or higher” on the ASSIST were 2 and 1, respectively. Table 3 shows the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUC for the interviewer-administered TAPS Tool, while Table 4 presents results for the self-administered tablet computer TAPS-2. These two formats for TAPS Tool administration had small differences in sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUC. Sensitivity exceeded 0.77 for all substance classes for detecting high risk ASSIST thresholds, except for prescription stimulants, prescription opioids, and prescription sedatives (because, as indicated in the methods section above, in contrast to the TAPS-2, the ASSIST combines prescription stimulants and illicit stimulants into a single item and heroin and prescription opioids into a single item). Specificities also exceeded 0.75 for all substances for detecting high risk with the exception of prescription stimulants. Given the similarities in their properties, for simplicity below we present in detail the properties of the interviewer-administered TAPS Tool.

Table 4.

Self-administered computerized TAPS Tool v. ASSIST (N=2,000)

| Positive on ASSIST N (%) |

Positive on TAPS N (%) |

Sensitivity (95 % Wilson Score CI)1 | Specificity (95 % Wilson Score CI) | PPV2 (95 % Wilson Score CI) | NPV3 (95 % Wilson Score CI) | AUC4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Risk on the ASSIST5 (TAPS Cut-Point = 2) | |||||||

| Tobacco | 115 (0.06) | 539 (0.27) | 0.90 (0.83, 0.94) | 0.77 (0.75, 0.79) | 0.19 (0.16, 0.23) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.83 |

| Alcohol | 69 (0.03) | 470 (0.24) | 0.91 (0.82, 0.96) | 0.79 (0.77, 0.81) | 0.13 (0.10, 0.16) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.85 |

| Marijuana | 27 (0.01) | 190 (0.10) | 0.96 (0.81, 0.99) | 0.92 (0.91, 0.93) | 0.14 (0.10, 0.20) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.94 |

| Cocaine, meth | 33 (0.02) | 81 (0.04) | 0.91 (0.77, 0.97) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.37 (0.27, 0.48) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.94 |

| Rx stimulant | 4 (0.00) | 10 (0.01) | 0.25 (0.05, 0.70) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.10 (0.02, 0.40) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.62 |

| Total Stimulants (Cocaine, meth & Rx stimulant) | 33 (0.02) | 88 (0.04) | 0.91 (0.77, 0.97) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.34 (0.25, 0.44) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.94 |

| Heroin | 39 (0.02) | 47 (0.02) | 0.79 (0.64, 0.89) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.66 (0.52, 0.78) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.89 |

| Rx opioids | 39 (0.02) | 41 (0.02) | 0.59 (0.43, 0.73) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.56 (0.41, 0.70) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.79 |

| Total Opioids (heroin & Rx opioids) | 39 (0.02) | 67 (0.03) | 0.92 (0.79, 0.97) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.54 (0.42, 0.65) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.95 |

| Sedative | 8 (0.00) | 55 (0.03) | 0.75 (0.41, 0.93) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.11 (0.05, 0.22) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.86 |

| Moderate Risk of Higher on the ASSIST6 (TAPS Cut-Point = 1) | |||||||

| Tobacco | 900 (0.45) | 766 (0.38) | 0.81 (0.78, 0.83) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.86 (0.84, 0.88) | 0.89 |

| Alcohol | 283 (0.14) | 713 (0.36) | 0.84 (0.79, 0.88) | 0.72 (0.70, 0.74) | 0.33 (0.30, 0.37) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.78 |

| Marijuana | 376 (0.19) | 312 (0.16) | 0.70 (0.65, 0.74) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.85 (0.81, 0.89) | 0.93 (0.92, 0.94) | 0.84 |

| Cocaine, meth | 262 (0.13) | 112 (0.06) | 0.39 (0.33, 0.45) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.90 (0.83, 0.94) | 0.91 (0.90, 0.92) | 0.69 |

| Rx stimulant | 56 (0.03) | 19 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.07, 0.25) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.42 (0.23, 0.64) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.57 |

| Total Stimulants (Cocaine, meth & Rx stimulant) | 262 (0.13) | 124 (0.06) | 0.40 (0.34, 0.46) | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.84 (0.77, 0.89) | 0.92 (0.91, 0.93) | 0.69 |

| Heroin | 181 (0.09) | 59 (0.03) | 0.31 (0.25, 0.38) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.95 (0.86, 0.98) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.95) | 0.65 |

| Rx opioids | 181 (0.09) | 81 (0.04) | 0.28 (0.22, 0.35) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.62 (0.51, 0.72) | 0.93 (0.92, 0.94) | 0.63 |

| Total Opioids (heroin & Rx opioids) | 181 (0.09) | 113 (0.06) | 0.44 (0.37, 0.51) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.70 (0.61, 0.78) | 0.95 (0.94, 0.96) | 0.71 |

| Sedative | 92 (0.05) | 81 (0.04) | 0.52 (0.42, 0.62) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.59 (0.48, 0.69) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.75 |

Notes. Rx= prescription. Meth=methamphetamine. Cut-off of 1 on high risk ASSIST score for select substances as follows: cocaine/methamphetamine = 0.96; total stimulants = 0.96; heroin = 0.93; prescription opioids = 0.895; total opioids = 0.98. Cut off of 2 on moderate risk or higher ASSIST score for alcohol = 0.81.

Wilson Score CI = Wilson Score Confidence Intervals

PPV = Positive Predictive Value

NPV = Negative Predictive Value

AUC = Area Under the Curve

High Risk on the ASSIST for tobacco, alcohol and all drugs ≥ 27.

Moderate Risk on the ASSIST for tobacco and all drugs = 4 – 26; Moderate Risk for alcohol = 11–26

Tobacco n = 900 (in contrast to Table 2 in which n = 901) because of missing data.

3.3 Identification of high-risk ASSIST scores from the Interviewer-administered TAPS Tool (Table 3)

The interviewer-administered TAPS Tool had good sensitivity and specificity for high risk use of tobacco (0.90 and 0.77, respectively) and alcohol (0.87 and 0.80, respectively). For illicit drugs, sensitivity ranged from a low of 0.82 for heroin to a high of 0.96 for marijuana. For non-medical use of prescription drugs, sensitivities were lower. For prescription opioids, sensitivity was 0.41. As described above, the ASSIST has a single item that combines heroin and prescription opioid use. Therefore, the single ASSIST opioid item was compared to the combined heroin and prescription opioid items on the TAPS Tool which yielded a sensitivity of 0.92. The prescription stimulant and sedative items had very low sample size with high risk scores on the ASSIST for non-medical use of these medications (ns=4 and 8, respectively). Specificities exceeded .91 for all illicit substances. PPVs for tobacco and alcohol were 0.20 and 0.13, respectively. PPVs for illicit substances ranged from 0.70 for heroin to 0.14 for marijuana. Finally, NPVs exceeded 0.99 for alcohol, tobacco, illicit substances and use of non-prescription medications.

3.4 Identification of moderate risk ASSIST scores from the Interviewer-administered TAPS Tool (Table 2)

The interviewer-administered TAPS Tool had good sensitivity and specificity for identification of moderate risk tobacco use (0.83 and 0.97, respectively) and good sensitivity and acceptable specificity for alcohol (0.83 and 0.74, respectively). Among illicit drugs, sensitivity was acceptable for marijuana (0.71), while for all other illicit drugs and prescription medications, it was low (ranging from 0.28 for prescription opioids to 0.47 for sedatives). In contrast, specificities were uniformly high, ranging at or exceeding 0.97 for all illicit drugs and prescription medications. PPVs for tobacco and alcohol were .96 and .34, respectively. PPVs for illicit and non-medical use of prescription drugs ranged from .42 for prescription stimulants to .93 for heroin. Finally, NPVs exceeded 0.87 for tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs and non-medical use of prescription medications.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the concurrent validity of the TAPS Tool (a modified version of the ASSIST-Lite) in comparison to the full WHO ASSIST as part of a large, multi-site study in Eastern US primary care patients. The TAPS Tool was found to have favorable sensitivity and specificity at a cutpoint of 2 to detect high risk use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, stimulants (prescription and cocaine/methamphetamine combined) and opioids (prescription opioids and heroin combined).

The TAPS Tool at a cutpoint of 1 also had favorable sensitivity and specificity for detecting moderate risk use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. In contrast, its sensitivity was unacceptably low in detecting moderate risk use of stimulants (cocaine, prescription stimulants) opioids (heroin, prescription opioids), and sedatives. One likely reason for this finding is that participants who report current abstinence but have experienced certain problems in the past (concern expressed by friends or relatives, and failed attempts to control, cut down, or stop using) can still score in the moderate risk range on the ASSIST. In contrast, participants who did not use the substance in the past 3 months would have a zero score on the TAPS Tool. A moderate risk score on the ASSIST in the face of no recent drug use might prove confusing to primary care providers because it includes people who may be at risk for using as well as those who are using and have some use-related problems. Thus, a potential benefit of the ASSIST-Lite and the TAPS Tool is that only recent (past 3 month) use garners any score. Notwithstanding its low sensitivity for detecting moderate risk of certain drugs, a score of 1 should prompt providers to conduct further assessment of their patient’s use of these substances

Opioid misuse is a growing problem in the US (Compton et al., 2016) and elsewhere (Degenhardt et al., 2014). Patients who misuse prescription opioids may switch to heroin because of its lower price (Mars et al., 2014). Primary care practices provide a potentially rich venue in which to identify patients misusing opioids. In the present study, 181 (9%) of participants were identified with moderate or higher opioid risk scores on the ASSIST and 39 (2%) had a high-risk opioid score. At a cutpoint of 2 (i.e., identifying participants with high risk opioid use scores), the TAPS Tool had a sensitivity of 0.92, specificity of 0.99, PPV of 0.59, NPV of 1.0, and AUC of 0.95. Although these results should be interpreted with some caution because of the relatively small sample size, it would be prudent to carefully assess patients with a TAPS Tool score of 2 for the need for opioid treatment.

In the present study, the mean time required to complete the TAPS Tool was 4.47 for the computer self-administered version, and 2.39 minutes for the interviewer-administered version. This compares favorably to the length of time required for the interviewer-administered ASSIST, which has been reported to require between 5 and 15 minutes (Ali et al. 2013). It should be noted that the time required to administer the TAPS Tool via tablet computer in the present study may overestimate the time required in clinical practice, since all participants completed the TAPS-2 regardless of their responses on TAPS-1. In practice, a patient who reported no illicit drug use on the TAPS-1, for example, would not be administered the TAPS-2 items for marijuana, cocaine, or heroin. The time required to complete the self-administered TAPS Tool also compared favorably to the computer self-administered versions of the ASSIST reported in the literature. In the ACASI ASSIST validation study in adult primary care patients, the mean time was 4 minutes, (McNeely et al., 2016). Another study of a computer self-administered ASSIST with incarcerated men reported that the ACASI ASSIST was completed in 5–10 minutes (Wolff et al., 2015).

The study has a number of strengths, including a large sample size, a diverse population recruited from multiple primary care settings across several Eastern US states, and comparison to a criterion measure (the ASSIST) that underwent rigorous psychometric testing (Humeniuk et al., 2008; Newcombe et al., 2005). However, there are also a number of limitations to be considered, including sampling only from the Eastern US states, and having only an English language version. Hence, findings may not generalize to other parts of the US or to other countries. In addition, data were collected under research conditions, and results were not given to medical providers. The extent to which the instrument would perform equally well when delivered by primary care staff and entered into the patient’s medical record is not known. Although research assistants used a systematic strategy for approaching patients in the clinics’ waiting rooms to minimize bias in recruitment, we do not know the extent to which study participants were representative of the clinic patient populations.

The TAPS Tool has a number of potential advantages compared to other screeners. In contrast to single item screens, it inquires about specific substances and goes beyond simple endorsement of use by obtaining data on problematic use. It screens for all classes of substances, in contrast to single substance screeners such as the AUDIT for alcohol (Bradley et al., 2003) or the Fagerstrom for tobacco (Tate & Schmitz, 1993). It is much briefer and easier to score than the full ASSIST and can lead to actionable results based on the scores, such that individuals who score zero need only receive praise and encouragement and those who score 2 or above need an assessment for treatment. The individuals who score 1 would also benefit from further assessment, and may be appropriate for brief intervention with prevention messaging and follow-up. Because the self-administered tablet computer instrument performed as well as the interviewer-administered instrument, either approach could be used in primary care practices, permitting flexibility and affording the possibility of direct entry into the patient’s medical record or self-completion while waiting for the scheduled appointment.

5. Conclusions

In comparison to the ASSIST, the TAPS Tool performed well in detecting high risk ASSIST scores for all substances and for detecting moderate-risk ASSIST scores for alcohol tobacco, and marijuana. It did not perform well in identifying individuals with moderate risk ASSIST scores for other drugs. The TAPS Tool score provides the primary care physician with a window into current drug use and problems, and is an alternative to the longer version of the ASSIST. More research is needed to determine the potential benefits of using the TAPS Tool and the ASSIST-lite in different patient populations.

Highlights.

This study examined the performance of a two-step screening and brief assessment instrument (TAPS Tool) for substance use problems in both an interviewer and self-administered format, compared to the longer WHO ASSIST.

The interviewer and self-administered versions of the TAPS Tool generated similar results

The TAPS Tool identified primary care patients with high-risk ASSIST scores for alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs as well moderate-risk users of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana.

Acknowledgments

Funding source

The study was supported through National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Cooperative Agreement Nos. UG1DA013034, U10DA013727, UG1DA040317, and UG1DA013035. NIDA or the National Institutes of Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; data acquisition, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov NCT02110693

Declaration of interests

Dr. Schwartz in the past provided a one-time consultation to Reckitt-Benckiser, one of the manufacturers of buprenorphine, on behalf of Friends Research Institute. Dr Ali has received an untied educational grant from Reckitt–Benckiser to conduct a pharmacogenetics study. Dr. O’Grady has, in the past, received reimbursement for his time from Reckitt–Benckiser. Dr. Subramaniam and Ms. Cushing are employees of the Center for the Clinical Trials Network (CCTN), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which is the funding agency for the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. Dr. Subramaniam’s participation in this publication arises from her role as a project scientist on a cooperative agreement for this study. No financial disclosures were reported by Ms. Sharma and Nordeck, Drs. Mitchell, Gryczynski, McNeely, Wu, Sharma, and Wahle. Dr. Marsden has received educational grant funding at King’s College London for a study of psychological interventions in opioid agonist treatment (2010–2016; Indivior PLC via Action on Addiction). Merck Serono has given him honoraria in 2013 and 2015 for clinical oncology medicine). He has received honoraria from Indivior via PCM Scientific in relation to the Improving Outcomes in Treatment of Opioid Dependence conference (faculty member, 2012–2013; co-chair, 2015–2016).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali R, Meena S, Eastwood B, Richards I, Marsden J. Ultra-rapid screening for substance-use disorders: The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST-Lite) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132(1–2):352–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, Dobie DJ, Davis TM, Sporleder JL, Maynard C, Burman ML, Kiviahan DR. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Archives of Internal Medicines. 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:154–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Mathers B, Hall WD, Flaxman AD, Johns N, Vos T. The global epidemiology and burden of opioid dependence: Results from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1320–1333. doi: 10.1111/add.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz FJ, Jane M, Salto E, Pardell H, Salleras L, Pinet C, de Leon J. A brief measure of high nicotine dependence for busy clinicians and large epidemiological surveys. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:161–168. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryczynski J, Kelly SM, Mitchell SG, Kirk A, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP. Validation and performance of the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) among adolescent primary care patients. Addiction. 2014;110:240–247. doi: 10.1111/add.12767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryczynski J, Nordeck C, Mitchell SG, O’Grady KE, McNeely J, Wu LT, Schwartz RP. Reference periods in retrospective behavioral self-report: A qualitative investigation. American Journal on Addiction. 2015;24(8):744–7. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12305. Epub 2015 Nov 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hides L, Cotton SM, Berger G, Gleeson J, O’Donnell C, Proffitt T, McGorry PD, Lubman DI. The reliability and validity of the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in first-episode psychosis. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:821–825. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, Farrell M, Formigoni ML, Jittiwutikarn J, de Lacerda RB, Ling W, Marsden J, Monteiro M, Nhiwatiwa S, Pal HJ, Poznyak V, Simon S. Validation of the alcohol, smoking, and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103:1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, Formigoni ML, de Lacerda RB, Ling W, McCree B, Newcombe D, Pal HJ, Poznyak V, Simon S, Vendetti J. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction. 2012;107:957–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PC, Cleland CM, Gourevitch MN, Rotrosen J, Strauss S, Russell L, McNeely J. Accuracy of the Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ACASI ASSIST) for identifying unhealthy substance use and substance use disorders in primary care patients. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2016;165:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars SG, Bourgois P, Karandinos G, Montero F, Ciccarone D. “Every ‘never’I ever said came true”: Transitions from opioid pills to heroin injecting. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2014;25(2):257–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely J, Strauss SM, Wright S, Rotrosen J, Khan R, Lee JD, Gourevitch MN. Test-retest reliability of a self-administered Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in primary care patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;47:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely J, Wu LT, Subramaniam G, Sharma G, Cathers LA, Svikis D, Sleiter L, Russell L, Nordeck C, Sharma A, O’Grady KE, Bouk LB, Cushing C, King J, Wahle A, Schwartz RP. Performance of the Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use (TAPS) Tool for Substance Use Screening in Primary Care Patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016 Sep 6; doi: 10.7326/M16-0317. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely J, Strauss SM, Rotrosen J, Ramautar A, Gourevitch MN. Validation of an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) version of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) in primary care patients. Addiction. 2016;111(2):233–44. doi: 10.1111/add.13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Resource Guide: Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. [Accessed on March 16, 2016];NIDA Quick Screen. 2016 Retrieved from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/resource-guide-screening-drug-use-in-general-medical-settings/nida-quick-screen.

- Newcombe DA, Humeniuk RE, Ali R. Validation of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): report of results from the Australian site. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2005;24(3):217–26. doi: 10.1080/09595230500170266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate JC, Schmitz JM. A proposed revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 1993;18:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1183–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. [Accessed on March 8, 2016];ASSIST Version 3.0. 2016 Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/assist_v3_english.pdf?ua=1.

- Wolff N, Shi J. Screening for Substance Use Disorder Among Incarcerated Men with the Alcohol, Smoking, Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): A Comparative Analysis of Computer-Administered and Interviewer-Administered Modalities. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;53:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, McNeely J, Subramaniam GA, Sharma G, VanVelduisen P, Schwartz RP. Design of the NIDA Clinical Trials Network Validation Study of Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medications, and Substance Use/Misuse (TAPS) Tool. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2016;50:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]