Abstract

While gliomas have been extensively modelled with a reaction–diffusion (RD) type equation it is most likely an oversimplification. In this study, three mathematical models of glioma growth are developed and systematically investigated to establish a framework for accurate prediction of changes in tumour volume as well as intra-tumoural heterogeneity. Tumour cell movement was described by coupling movement to tissue stress, leading to a mechanically coupled (MC) RD model. Intra-tumour heterogeneity was described by including a voxel-specific carrying capacity (CC) to the RD model. The MC and CC models were also combined in a third model. To evaluate these models, rats (n = 14) with C6 gliomas were imaged with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging over 10 days to estimate tumour cellularity. Model parameters were estimated from the first three imaging time points and then used to predict tumour growth at the remaining time points which were then directly compared to experimental data. The results in this work demonstrate that mechanical–biological effects are a necessary component of brain tissue tumour modelling efforts. The results are suggestive that a variable tissue carrying capacity is a needed model component to capture tumour heterogeneity. Lastly, the results advocate the need for additional effort towards capturing tumour-to-tissue infiltration.

Keywords: mathematical model, cancer, forecast, brain, glioma

1. Introduction

A fundamental challenge in the care of cancer patients is the limitation of standard radiographic measurements to accurately evaluate patient response and capture tumour growth kinetics. Biophysical models that incorporate patient-specific measurements may be able to address this challenge by providing accurate predictions of tumour growth and treatment response through which clinical care can be guided [1]. We [2–7] and others [8–12] have proposed that a practical way forward is to initialize and constrain predictive models via imaging data that can be acquired non-invasively, in three dimensions, and at numerous time points. Examples of such data include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography measurements that are routinely available and can characterize tumour vascularity and perfusion [13,14], tumour cellularity [15], metabolism [16] and hypoxia [17]. Towards this effort we are developing biophysical models that are parametrized from a subject's own imaging measurements and evaluating them in a pre-clinical model of glioma.

A common predictive model in the mathematical analysis of tumours is a reaction–diffusion (RD) model which describes the proliferation (reaction) and movement (diffusion) of tumour cells. Several groups have investigated neoplastic growth using variations of this model in several organ sites (brain [2,8,10,11,18], breast [4,5] and pancreas [19]). In the pre-clinical setting, we have previously used MRI data collected at three time points to estimate rat-specific diffusion and proliferation parameters which were then used to predict the in vivo spatio-temporal evolution of the tumour. These predictions were then directly compared to experimental MRI data collected at future time points. We previously observed [2] the RD model incompletely described in vivo C6 glioma growth at both the global (high error in tumour volume, low agreement in tumour shape) and local (high error in voxel cell number) levels. In this study, we seek to modify the standard RD model to improve the accuracy of predictions at both the global and local levels.

One possibility for the high global level errors is the assumption that the diffusion coefficient is constant in time. In the RD model, tumour growth is restricted only by the bounds of the simulation domain (e.g. the skull in the case of a rat glioma) and not inhibited by the surrounding brain tissue. However, the force exerted by the surrounding tissue [20] during tumour expansion is a critical biological interaction that can alter both tumour expansion [21] and shape [22]. This mechanical–biological interaction between the tumour mass and surrounding tissue mass has been previously incorporated into modelling brain [10,11,18,23], breast [4,5], kidney [24] and pancreatic [9,19] cancer. Here, we apply it to modelling in vivo C6 glioma growth using a mechanically coupled (MC) RD model.

Similarly, the high local level errors observed in vivo are a result of fundamental limitations of the standard RD model at describing intra-tumoural heterogeneity. More specifically, with a temporally constant proliferation rate and carrying capacity the cell number will saturate at steady state within the tumour resulting in a homogeneous distribution of tumour cells. The limitation of temporally constant proliferation can be addressed by incorporating additional equations or terms into the RD model that result in cell death or alteration of their proliferation status [25,26]. However, parametrizing these models on a subject-specific basis is challenging as they often have many free parameters that must be assigned in some reasonable way. Heterogeneity in cell density can also be obtained through spatially varying the carrying capacity which may occur due to physical limitations (e.g. decrease in available space to grow) and environmental limitations (e.g. poorly perfused, low nutrient concentration). The physical limitations on growth can be incorporated through the use of imaging measurements which can provide estimates of the vascular and extracellular–extravascular volume fractions [27]. Similarly, models that incorporate vascular growth or remodelling [28] can also account for these spatial variations in carrying capacity. In this work, we investigate a simplified alternative to these approaches to build in heterogeneity by linking the physical and environmental limitations on carrying capacity to a single lumped model parameter which can be estimated throughout the tumour from data observations (this model is termed the carrying capacity RD model, or CC).

In this contribution, we seek to evaluate the ability of the MC, CC and MC–CC (the combination of the MC and CC models) models to predict future tumour growth. Using serial diffusion-weighted MRI (DW-MRI) data acquired in a murine glioma model, we first estimate rat-specific model parameters to initialize and constrain the RD, MC, CC and MC–CC models for predicting the spatio-temporal tumour evolution. Model predictions are then directly compared to the future MRI measurements.

2. Theory

2.1. Reaction–diffusion model

The RD model, equation (2.1), describes the change in the distribution and number of tumour cells due to the random movement of tumour cells (diffusion) and proliferation (reaction):

|

2.1 |

where  is the number of cells at three-dimensional position

is the number of cells at three-dimensional position  and time t,

and time t,  is the cell diffusion coefficient at position

is the cell diffusion coefficient at position  , θ is the cellular carrying capacity (i.e. the maximum number of cells a region can support),

, θ is the cellular carrying capacity (i.e. the maximum number of cells a region can support),  is the tumour cell proliferation rate, and

is the tumour cell proliferation rate, and  indicates the three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z). Measurements from DW-MRI are used to provide estimates of

indicates the three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z). Measurements from DW-MRI are used to provide estimates of  or

or  at several time points [2,29]. These

at several time points [2,29]. These  are then used to solve an inverse problem of estimating model parameters P for equation (2.1). For the RD model P (PRD) includes voxel-wise values of

are then used to solve an inverse problem of estimating model parameters P for equation (2.1). For the RD model P (PRD) includes voxel-wise values of  and two global

and two global  parameters, one for all voxels within the white matter (Dw) and one for all voxels within the grey matter (Dg). A three dimensions in space (Δx = 250 µm, Δy = 250 µm, Δz = 1000 µm), fully explicit in time (time step = 0.01 days) finite difference (FD) simulation is used to solve the forward problem of equation (2.1) written in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

parameters, one for all voxels within the white matter (Dw) and one for all voxels within the grey matter (Dg). A three dimensions in space (Δx = 250 µm, Δy = 250 µm, Δz = 1000 µm), fully explicit in time (time step = 0.01 days) finite difference (FD) simulation is used to solve the forward problem of equation (2.1) written in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).  has no diffusive flux at the brain tissue boundaries (Neumann boundary condition).

has no diffusive flux at the brain tissue boundaries (Neumann boundary condition).

2.2. Mechanically coupled model

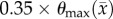

To address the high global level errors produced by the RD [2] model, a MC RD model [4,5,18] will be used. The MC model is based on observations that the growth of tumour spheroids is inhibited as the stiffness of the embedded matrix increases [21]. Furthermore, as the tumour volume expands the tumour induces significant mechanical stress on the surrounding tissue [30] resulting in a mass effect. Thus, as the tumour expands there is an increasing amount of mechanical stress which can restrict further expansion by the tumour. These biophysical effects are incorporated in the MC model by altering equation (2.1) to incorporate a diffusion coefficient, equation (2.2), that is spatially and temporally variant in response to local tissue stress:

| 2.2 |

where D0 represents tumour cell diffusion in the absence of mechanical restrictions, λ1 is an empirically derived stress-tumour cell diffusion coupling constant, and  is the von Mises stress [4,5,7,18]. A single value of D0 is used to describe tumour cell diffusion in the absence of mechanical restrictions. We assume that the mechanical environment (and the variations in local mechanical properties) is what primarily drives the local diffusion of tumour cells, and thus the variations in tumour shape. As the local von Mises stress increases, tumour cell movement will be inhibited by a decrease in the tumour cell diffusion coefficient,

is the von Mises stress [4,5,7,18]. A single value of D0 is used to describe tumour cell diffusion in the absence of mechanical restrictions. We assume that the mechanical environment (and the variations in local mechanical properties) is what primarily drives the local diffusion of tumour cells, and thus the variations in tumour shape. As the local von Mises stress increases, tumour cell movement will be inhibited by a decrease in the tumour cell diffusion coefficient,  .

.  is determined by calculating the tissue displacement (

is determined by calculating the tissue displacement ( ) caused by the growing tumour. The following equation, which is the linear elastic isotropic mechanical equilibrium equation with an expansion force related to

) caused by the growing tumour. The following equation, which is the linear elastic isotropic mechanical equilibrium equation with an expansion force related to  , is used to solve for

, is used to solve for  :

:

| 2.3 |

where G is the shear modulus, ν is Poisson's ratio, and λ2 represents a tumour cell force coupling constant. Equation (2.3) is solved using the FD method. Briefly, equation (2.3) is re-arranged into a matrix description of the system shown in the following:

| 2.4 |

where M represents the known FD coefficients from equation (2.3), u is a vector representing the unknown tissue displacement in the x-, y- and z-directions, and  is a vector containing the known gradient of N in the x-, y- and z-directions. M is a square 3n × 3n coefficient matrix where n is the number of nodes. This is solved using an iterative approach (Matlab's bicgstab function) using an incomplete LU decomposition of M as a preconditioner. M is built once at the beginning of the simulation, while

is a vector containing the known gradient of N in the x-, y- and z-directions. M is a square 3n × 3n coefficient matrix where n is the number of nodes. This is solved using an iterative approach (Matlab's bicgstab function) using an incomplete LU decomposition of M as a preconditioner. M is built once at the beginning of the simulation, while  is updated for each iteration. Boundary conditions were prescribed with no tissue displacement in the normal direction of the boundary, while tissue in the tangential directions was free to move (i.e. slip condition). U is then used to calculate the local normal and shear stresses (σ) that are used to calculate the three-dimensional spatial distribution of the Von Mises stress,

is updated for each iteration. Boundary conditions were prescribed with no tissue displacement in the normal direction of the boundary, while tissue in the tangential directions was free to move (i.e. slip condition). U is then used to calculate the local normal and shear stresses (σ) that are used to calculate the three-dimensional spatial distribution of the Von Mises stress,  , using the following equation:

, using the following equation:

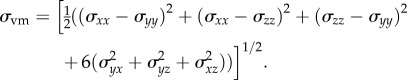

|

2.5 |

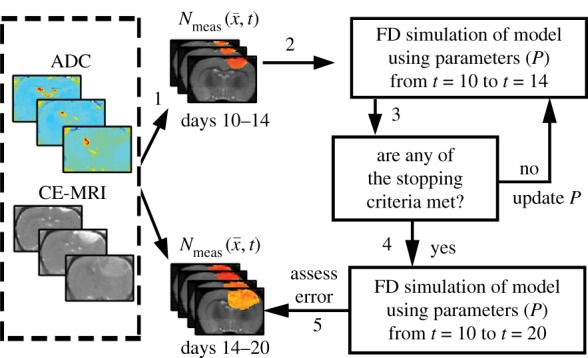

The estimated parameter set, P, for the MC (PMC) model includes voxel-wise  and one D0 value. PMC is estimated using the same approach as for the RD model. Poisson's ratio was set at 0.45, while G was assigned region-wise (i.e. cortex = 418 Pa, corpus callosum = 238 Pa, hippocampus = 466 Pa, thalamus = 383 Pa, putamen = 275 Pa) [31,32]. λ2 was assigned to 1. Figure 1 shows how the MC model, equations (2.2)–(2.5), spatially and temporally adjusts tumour cell diffusion. Starting with the current values of

and one D0 value. PMC is estimated using the same approach as for the RD model. Poisson's ratio was set at 0.45, while G was assigned region-wise (i.e. cortex = 418 Pa, corpus callosum = 238 Pa, hippocampus = 466 Pa, thalamus = 383 Pa, putamen = 275 Pa) [31,32]. λ2 was assigned to 1. Figure 1 shows how the MC model, equations (2.2)–(2.5), spatially and temporally adjusts tumour cell diffusion. Starting with the current values of  ,

,  and

and  the FD implementation of equation (2.1) is evolved a single time step. Tissue displacement (

the FD implementation of equation (2.1) is evolved a single time step. Tissue displacement ( ) is then calculated using the gradient of the latest distribution of

) is then calculated using the gradient of the latest distribution of  via equation (2.3).

via equation (2.3).  is then used to calculate

is then used to calculate  via equation (2.5), within the simulation domain. The updated

via equation (2.5), within the simulation domain. The updated  is then used to calculate a new value of

is then used to calculate a new value of  using equation (2.2) before starting the next time-iteration.

using equation (2.2) before starting the next time-iteration.

Figure 1.

The panels depict a single iteration of the MC tumour model. The current values of  ,

,  and

and  are used in a finite difference simulation, step 1, of equation (2.1). The updated

are used in a finite difference simulation, step 1, of equation (2.1). The updated  is then used to calculate

is then used to calculate , step 2. Using G, ν, λ2 and

, step 2. Using G, ν, λ2 and  equation (2.4) is solved for

equation (2.4) is solved for  (step 3).

(step 3).  is then used to calculate the normal shear and stresses, step 4, in order to calculate

is then used to calculate the normal shear and stresses, step 4, in order to calculate  .

.  is then updated, step 5, using

is then updated, step 5, using  in equation (2.2). (Online version in colour.)

in equation (2.2). (Online version in colour.)

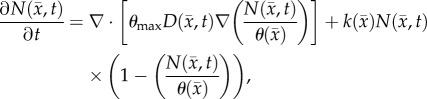

2.3. Voxel-specific carrying capacity model

Another shortcoming of the RD model is that at steady state it predicts a homogeneous distribution of tumour cells within the tumour compared to the heterogeneous distribution observed in vivo. The in vivo heterogeneous distribution may occur due to several factors including local space limitations (e.g. variations in local vascularity or extracellular swelling) and local viability (e.g. distance to nearby vasculature, amount of available nutrients). One way to incorporate the heterogeneity observed in vivo is to allow the carrying capacity to vary spatially, effectively lumping geometric and metabolic growth constraints into a voxel-wise parameter describing the local carrying capacity. Thus, we amend equation (2.1) to incorporate a voxel-specific carrying capacity [33]:

|

2.6 |

where θmax is the maximum number of cells a voxel can physically support. The voxel-specific carrying capacity,  , alters both the movement (preferential movement to areas with a lower packing fraction versus areas of lower cell number) and proliferation (maximum cell number varies throughout the tumour) of tumour cells. The estimated parameter set, P, for the CC (PCC) model includes voxel-wise

, alters both the movement (preferential movement to areas with a lower packing fraction versus areas of lower cell number) and proliferation (maximum cell number varies throughout the tumour) of tumour cells. The estimated parameter set, P, for the CC (PCC) model includes voxel-wise  , voxel-wise

, voxel-wise  and two

and two  values; one for white matter and one for grey matter. PCC is estimated using the same approach used for the RD model.

values; one for white matter and one for grey matter. PCC is estimated using the same approach used for the RD model.  and

and  are spatially, but not temporally, variant. While it is likely that

are spatially, but not temporally, variant. While it is likely that  and

and  have some temporal variation as a tumour grows and some error will be incurred as a consequence, in this preliminary realization, we have chosen to assess the fidelity of our approach with the assumption of these parameters being temporally invariant.

have some temporal variation as a tumour grows and some error will be incurred as a consequence, in this preliminary realization, we have chosen to assess the fidelity of our approach with the assumption of these parameters being temporally invariant.

2.4. Combined model (MC–CC)

The fourth model amends the RD model to incorporate both a spatially temporally variant  coupled to local tissue stress (MC) and a spatially variant

coupled to local tissue stress (MC) and a spatially variant  (CC). The estimated parameter set, P, for the MC–CC (PMC–CC) model includes voxel-wise

(CC). The estimated parameter set, P, for the MC–CC (PMC–CC) model includes voxel-wise  , voxel-wise

, voxel-wise  and one D0 value.

and one D0 value.

3. Material and methods

3.1. In vivo experiments

For all imaging and surgical procedures, rats were anaesthetized with 2% isoflurane in 98% oxygen. Female Wistar rats (n = 14, 236–268 g) were anaesthetized and inoculated intracranially with C6 glioma cells (1 × 105) via stereotaxic injection. While the C6 line may not recapitulate all the manifestations of human glioma, it was selected for its widespread use in neuro-oncology, pre-clinical evaluation of imaging methods, and mathematical modelling, as well as its repeatable growth characteristics [34]. A jugular catheter was placed in each rat 8 days after the tumour inoculation surgery for injection of an MRI contrast agent. During each MRI procedure, rat body temperature was maintained near 37°C by a flow of warm air directed over the animal and respiration was monitored using a pneumatic pillow. The first imaging time point occurred 10 days after inoculation surgery. The imaging measurement time points for each rat are reported in table 1. DW-MRI, contrast-enhanced MRI (CE-MRI) and T1 maps were acquired on a 9.4 T horizontal-bore magnet (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a 38 mm diameter Litz quadrature coil (Doty Scientific, Columbia, SC, USA). All MR images were acquired over a 32 × 32 × 16 mm3 field of view sampled with a 128 × 128 × 16 matrix. From the beginning of the second through the final imaging session, a mutual information based rigid registration algorithm was used to register the current imaging time point to the initial imaging session.

Table 1.

Animal imaging time points.

| rat | days post inoculation |

|---|---|

| 1–4 | 10,12,14,15,16,18,20 |

| 5–6 | 10,12,14,15,18,20 |

| 7–9 | 10,12,14,15,16,18 |

| 10–13 | 10,12,14,15,16 |

| 14 | 10,12,14,15 |

DW-MRI was acquired using a pulsed fast spin echo diffusion sequence with three orthogonal diffusion encoding directions with b-values of 150, 500 and 1100 s mm−2, and Δ/δ = 25/2 ms. The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) was estimated on a voxel basis using standard methods [35].  was then estimated from ADC values [29,36,37] using the following equation:

was then estimated from ADC values [29,36,37] using the following equation:

| 3.1 |

where θmax represents the maximum tumour cell carrying capacity for an imaging voxel, ADCw is the ADC of free water at 37°C (2.5 × 10−3 mm2 s−1) [35],  is the ADC value at position

is the ADC value at position  and time t, and ADCmin is the minimum ADC value observed within the tumour regions-of-interest (ROIs) across all animals. We assume that the ADCmin corresponds to the voxel with the largest number of cells equal to θmax which was calculated using the imaging voxel dimensions, and assuming spherical tumour cells with a packing density of 0.7405 [38] with an average cell volume of 908 µm3 [39]. In this work, we assume that all changes in ADC are directly related to changes in tumour cellularity. However, changes in ADC may also be a result of changes in cell size, cell permeability, cell tortuosity; we return to this critical point in the Discussion section.

and time t, and ADCmin is the minimum ADC value observed within the tumour regions-of-interest (ROIs) across all animals. We assume that the ADCmin corresponds to the voxel with the largest number of cells equal to θmax which was calculated using the imaging voxel dimensions, and assuming spherical tumour cells with a packing density of 0.7405 [38] with an average cell volume of 908 µm3 [39]. In this work, we assume that all changes in ADC are directly related to changes in tumour cellularity. However, changes in ADC may also be a result of changes in cell size, cell permeability, cell tortuosity; we return to this critical point in the Discussion section.

Tissue T1 was measured using data from an inversion-recovery snapshot experiment with TR/TE = 5000/3 ms, TI (inversion time) = (8 TIs logarithmically spaced between 200 and 4000 ms), and two averaged excitations. CE-MRI was acquired using a spoiled gradient echo sequence with TR/TE = 45/1.4 ms, two averaged excitations, and a flip angle = 20° collected before and after the injection of a 200 µl bolus (0.05 mmol kg−1) of Gado-DTPA™ (BioPhysics Assay Lab, Worcester, MA, USA).

Tumour ROIs were identified using the difference of the pre- and post-contrast agent images from CE-MRI. The measured tumour cell distribution,  , was then calculated within these ROIs from ADC measurements using equation (3.1). T1 maps were used to define general white and grey matter regions and to identify the cortex, corpus callosum, hippocampus, thalamus and putamen.

, was then calculated within these ROIs from ADC measurements using equation (3.1). T1 maps were used to define general white and grey matter regions and to identify the cortex, corpus callosum, hippocampus, thalamus and putamen.

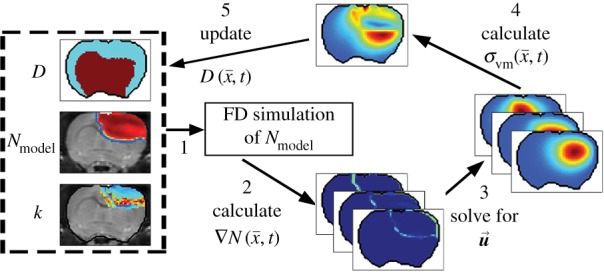

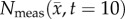

3.2. Parameter estimation

The parameter estimation method is shown in figure 2. ADC maps obtained from DW-MRI are used to provide estimates of  at several time points (step 1). The optimal parameters were determined by minimizing the sum squared difference between the measured and model estimated tumour cell (i.e. the objective function) using the Levenberg–Marquardt method (steps 2–4). The optimization process terminated when one of the following occurs: error in the objective function stagnated (less than 0.5% change in value between successive iterations), iteration count reaches 1000, or change in parameter values stagnated (less than 0.5% change in value between successive iterations). A 3 × 3 voxel Gaussian filter was applied to

at several time points (step 1). The optimal parameters were determined by minimizing the sum squared difference between the measured and model estimated tumour cell (i.e. the objective function) using the Levenberg–Marquardt method (steps 2–4). The optimization process terminated when one of the following occurs: error in the objective function stagnated (less than 0.5% change in value between successive iterations), iteration count reaches 1000, or change in parameter values stagnated (less than 0.5% change in value between successive iterations). A 3 × 3 voxel Gaussian filter was applied to  prior to the start of the parameter optimization to reduce the effects of noise within individual voxels. The model parameters were constrained from 0 to 10 day−1 for

prior to the start of the parameter optimization to reduce the effects of noise within individual voxels. The model parameters were constrained from 0 to 10 day−1 for  ,

,  to

to  for θ, and 5000–500 000 µm2 day−1 for Dw, Dg and D0. The estimated model parameters were within these constraints and did not optimize to the lower or upper constraints. Parameter constraints were selected based on previous experience [2] and biologically relevant ranges observed in the literature. The upper constraints for the diffusion coefficients were used in a Von Neumann stability analysis [40] to determine the maximum time step for FD simulations to remain monotonic and stable. A single time step of 0.01 day was used for all simulations.

for θ, and 5000–500 000 µm2 day−1 for Dw, Dg and D0. The estimated model parameters were within these constraints and did not optimize to the lower or upper constraints. Parameter constraints were selected based on previous experience [2] and biologically relevant ranges observed in the literature. The upper constraints for the diffusion coefficients were used in a Von Neumann stability analysis [40] to determine the maximum time step for FD simulations to remain monotonic and stable. A single time step of 0.01 day was used for all simulations.  was estimated voxel-wise within the tumour ROI and assigned 0 elsewhere. Similarly, for the CC and MC–CC models,

was estimated voxel-wise within the tumour ROI and assigned 0 elsewhere. Similarly, for the CC and MC–CC models,  was estimated voxel-wise within the tumour ROI and assigned the maximum value elsewhere. Single values for D0, Dg and Dw were estimated for the whole brain.

was estimated voxel-wise within the tumour ROI and assigned the maximum value elsewhere. Single values for D0, Dg and Dw were estimated for the whole brain.

Figure 2.

Flow chart for parameter optimization of the tumour models. ADC values are used to calculate cell number within regions of interested identified in CE-MRI, step 1. A FD simulation, step 2, is then initialized with  and an initial guess of P to simulate N at days 12 and 14 (

and an initial guess of P to simulate N at days 12 and 14 ( ). The stopping criteria, step 3, are then evaluated. When the stopping criteria are met, step 4, the optimized P is used in an additional FD simulation to simulate

). The stopping criteria, step 3, are then evaluated. When the stopping criteria are met, step 4, the optimized P is used in an additional FD simulation to simulate  at days 10 to 20, step 5, otherwise P is updated and the optimization continues. (Online version in colour.)

at days 10 to 20, step 5, otherwise P is updated and the optimization continues. (Online version in colour.)

An in silico study was performed for each model to evaluate the robustness of the parameter optimization approach to measurement noise. Briefly, for each model 250 noisy datasets were generated by adding random noise from a normal distribution with a standard deviation based on the repeatability of ADC measurements [35] (as described in [2]). Model parameters were then estimated from the noisy datasets and then compared with the true model parameters used to grow the synthetic datasets. Model parameter optimization used the Lonestar 5 Cluster at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) of the University of Texas at Austin.

3.3. Forward evaluation and error analysis

After optimization of P for each model, these values were then used in an FD simulation initialized at day 10 and ‘grown’ to each rat's final imaging measurement (figure 2, step 5). The simulated tumour growth (NRD, NMC, NCC, NMC−CC,) was then sampled at time points corresponding to the experimentally acquired imaging time points. As the tumour expanded into regions where an estimate of  was not obtained,

was not obtained,  was assigned using a local average of available non-zero k's within a 3 × 3 × 3 voxel kernel. This approach results in a smooth proliferation map outside of the estimated region with areas of predominately high or low proliferation rates moving outwards as the tumour grows.

was assigned using a local average of available non-zero k's within a 3 × 3 × 3 voxel kernel. This approach results in a smooth proliferation map outside of the estimated region with areas of predominately high or low proliferation rates moving outwards as the tumour grows.

Error between predicted and the measured tumour growth (identified using CE-MRI data) was assessed at the global and local levels. At the global level, error was assessed by calculating the per cent error in tumour volume and the average surface distance (ASD). The ASD is the average minimum distance between a voxel on the surface of the model predicted tumour volume and a voxel on the surface of the measured tumour volume. At the local level, error was assessed by calculating the average per cent error in cell number, the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), and the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC). Per cent error in tumour volume was used to assess the error in volume estimates, while the agreement between ROI shapes was assessed using the ASD. The per cent error in tumour volume was computed for each model by comparing the predicted tumour volume to the measured tumour volume on days 15–20. Similarly, the predicted tumour ROIs on days 15–20 were compared to the measured tumour volume on the same days to compute the ASD. The error at the local level was assessed at days 15–20 by calculating at each voxel the per cent error between  and

and  . The voxel-wise error is then averaged to compute the average per cent error in cell number. The PCC and CCC were also calculated to evaluate the correlation and agreement between voxel-wise cell number and the observed cell number. All results are presented as the mean and 95% CI when appropriate.

. The voxel-wise error is then averaged to compute the average per cent error in cell number. The PCC and CCC were also calculated to evaluate the correlation and agreement between voxel-wise cell number and the observed cell number. All results are presented as the mean and 95% CI when appropriate.

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the differences in global and local errors between the RD, MC, CC and MC–CC models. Tukey's honest significant difference test was then used for pairwise comparisons. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Models that had significant differences at all 4 time points were considered to be highly suggestive of a fundamental model requirement, while models with significant differences at 3 time points were considered moderately suggestive. No conclusions were made for models with significant differences at 2 or fewer time points.

4. Results

4.1. Parameter optimization

Table 2 shows the results which evaluate the optimization process for synthetic datasets for the RD, CC, MC and MC–CC models. The absolute value of error in estimated parameter values ranged from 0.74% to 6.92% for all models and model parameters.

Table 2.

Synthetic dataset optimization results. Per cent absolute error in model parameter means (95% CI).

| model parameters | RD | CC |

|---|---|---|

| Dw | 2.39 (0.18) | 2.19 (0.20) |

| Dg | 2.20 (0.16) | 2.26 (0.21) |

|

5.55 (0.60) | 5.46 (0.62) |

|

n.a. | 1.39 (0.13) |

| model parameters | MC | MC–CC |

|---|---|---|

| D0 | 0.74 (0.06) | 3.36 (0.23) |

|

1.48 (0.20) | 6.92 (0.67) |

|

n.a. | 3.44 (0.29) |

4.2. Mechanically coupled model

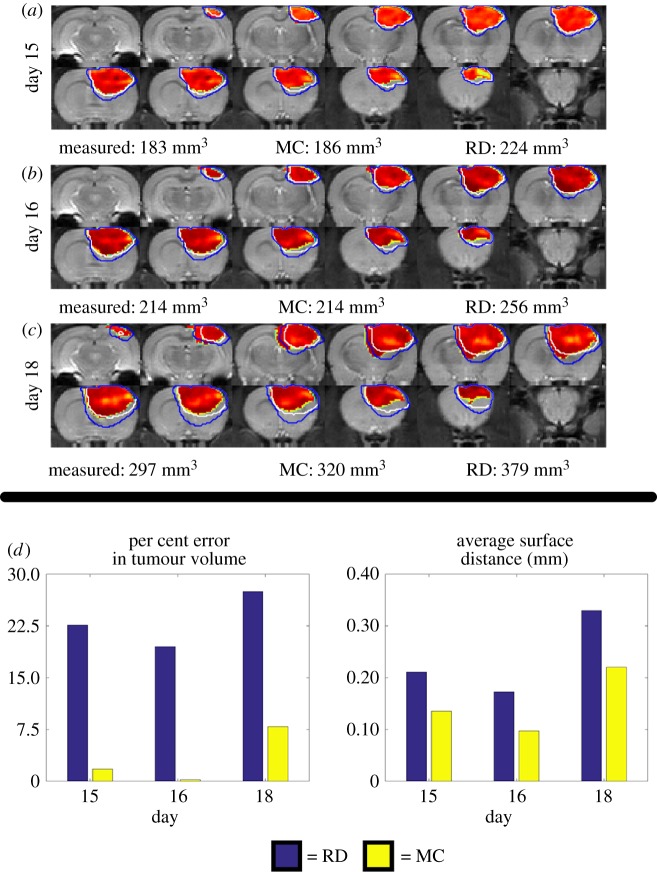

Figure 3 shows the comparison at the global level of the RD and MC model predictions for rat 7. The MC model resulted in lower error in tumour volume relative to the RD model at day 15. Increased error is observed for the RD compared to the MC model at the final imaging time point (27.48% for the RD and 7.89% for the MC model). (Note: for clarity, the CC model is excluded from this figure as its contours overlap with the RD model.) Figure 3d shows a steady increase in per cent error in tumour volume for the RD model while the MC model remains below 8%. Similarly, the MC model results in a decreased ASD (0.22 mm for the MC and 0.33 mm for the RD), which is most noticeable at the later time points.

Figure 3.

Global error analysis for the MC and RD models. Rows (a–c) show  with two outlines representing the simulated tumour spread for the

with two outlines representing the simulated tumour spread for the  (blue lines) and the

(blue lines) and the  (white lines) over the entire tumour volume at days 15, 16 and 18 for rat 7. The measured, MC, and RD tumour volume values for each day are displayed below each row. The MC model has less than 8% error at all time points, while the RD model has greater than 19% error at all prediction time points. Panel (d) quantifies rows (a–c) by showing the per cent error in tumour volume (blue bars, RD; yellow bars, MC) and the average surface distance at days 15, 16 and 18. The MC model exhibits lower global level error (decreased per cent error in tumour volume and decreased ASD) compared to the RD model. (Online version in colour.)

(white lines) over the entire tumour volume at days 15, 16 and 18 for rat 7. The measured, MC, and RD tumour volume values for each day are displayed below each row. The MC model has less than 8% error at all time points, while the RD model has greater than 19% error at all prediction time points. Panel (d) quantifies rows (a–c) by showing the per cent error in tumour volume (blue bars, RD; yellow bars, MC) and the average surface distance at days 15, 16 and 18. The MC model exhibits lower global level error (decreased per cent error in tumour volume and decreased ASD) compared to the RD model. (Online version in colour.)

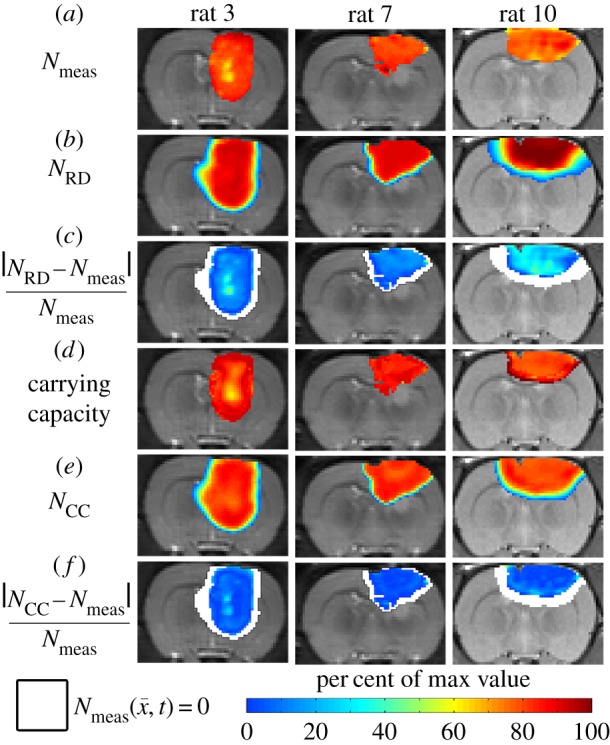

4.3. Voxel-specific carrying capacity model

Figure 4 shows the local error analysis for the CC model from the central tumour slice of rats 3, 7 and 10 on day 16.  , figure 4b, results in a more uniform distribution of tumour cells in comparison to what is observed in vivo, figure 4a. Elevated errors are observed in areas corresponding to low

, figure 4b, results in a more uniform distribution of tumour cells in comparison to what is observed in vivo, figure 4a. Elevated errors are observed in areas corresponding to low  for rats 3, 7 and 10 (13.27 ± 0.87%, 8.46 ± 0.70% and 23.10 ± 1.17%, respectively). Lower cellularity regions in

for rats 3, 7 and 10 (13.27 ± 0.87%, 8.46 ± 0.70% and 23.10 ± 1.17%, respectively). Lower cellularity regions in  are reflected in the fitted carrying capacity, figure 4d. The predictions of the CC model, figure 4e, resulted in less uniform distributions of tumour cells compared to NRD. In particular, rat 3 captures some of the low cellularity regions observed in

are reflected in the fitted carrying capacity, figure 4d. The predictions of the CC model, figure 4e, resulted in less uniform distributions of tumour cells compared to NRD. In particular, rat 3 captures some of the low cellularity regions observed in  . Rats 3, 7 and 10 showed reduced error (12.12 ± 0.90%, 5.08 ± 0.68% and 6.27 ± 0.51%, respectively) for the CC model, figure 4f, compared to the RD model, figure 4c. (Note: for clarity, the MC model is not included in this figure as it does not improve the local level errors and results in similar error maps as the RD model.)

. Rats 3, 7 and 10 showed reduced error (12.12 ± 0.90%, 5.08 ± 0.68% and 6.27 ± 0.51%, respectively) for the CC model, figure 4f, compared to the RD model, figure 4c. (Note: for clarity, the MC model is not included in this figure as it does not improve the local level errors and results in similar error maps as the RD model.)

Figure 4.

Local error analysis for the CC and RD models.  is shown in row (a) while the various model predictions of

is shown in row (a) while the various model predictions of  are shown in rows (b–f) for the central tumour slice at the final imaging time point of three rats at day 16. The per cent error between

are shown in rows (b–f) for the central tumour slice at the final imaging time point of three rats at day 16. The per cent error between  and

and  is shown in panels (c,f). The RD model, rows (b,c), poorly captures the intra-tumoural heterogeneity in

is shown in panels (c,f). The RD model, rows (b,c), poorly captures the intra-tumoural heterogeneity in  ; row (c) shows a high error (greater than 40%) for all rats. In comparison, the CC model, rows (d–f), better describes the intra-tumoural heterogeneity in

; row (c) shows a high error (greater than 40%) for all rats. In comparison, the CC model, rows (d–f), better describes the intra-tumoural heterogeneity in  . Row (e) shows the fitted carrying capacity map which is used in the finite difference simulation to obtain

. Row (e) shows the fitted carrying capacity map which is used in the finite difference simulation to obtain  , row (e). Reduced error (less than 20%) is observed in

, row (e). Reduced error (less than 20%) is observed in  , row (f), compared to

, row (f), compared to  , row (c). The white spaces in rows (c,f) represent voxels where

, row (c). The white spaces in rows (c,f) represent voxels where  . (Online version in colour.)

. (Online version in colour.)

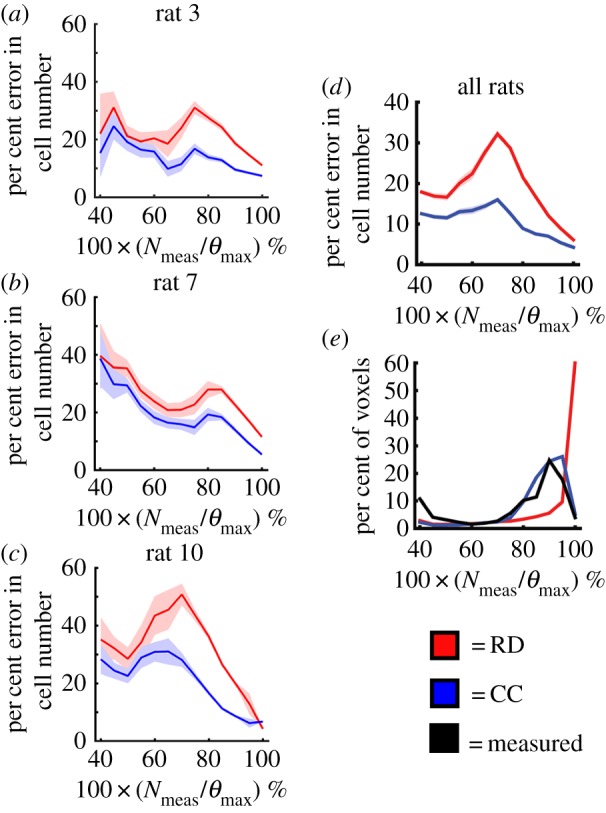

Figure 5 compares the RD and CC models, along with  at the local level. Rat 3 shows significant differences (p < 0.05) between the RD and CC model (for

at the local level. Rat 3 shows significant differences (p < 0.05) between the RD and CC model (for  /θ < 0.95) with the RD model resulting in a mean increase in error of 7.87% over the CC model. For rat 7, the CC model resulted in a mean decrease in error of 6.29% compared to the RD model. Similarly, significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed between the RD and CC models for rat 10, where the RD model also resulted in a mean increase of 11.28% error compared with the CC model (figure 5c). The cohort results display a similar trend as the individual rats. Figure 5a–d shows increased difference in per cent error between the RD and CC curves between 60 and 70%. For the cohort, the CC model resulted in a mean decrease in error of 7.48% compared with the RD model, figure 5d. The CC model more closely matches the in vivo observed distribution (figure 5e, SSE = 1.32 × 10−2) compared to the RD model (SSE = 2.83 × 10−1). The RD model results in a distribution of

/θ < 0.95) with the RD model resulting in a mean increase in error of 7.87% over the CC model. For rat 7, the CC model resulted in a mean decrease in error of 6.29% compared to the RD model. Similarly, significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed between the RD and CC models for rat 10, where the RD model also resulted in a mean increase of 11.28% error compared with the CC model (figure 5c). The cohort results display a similar trend as the individual rats. Figure 5a–d shows increased difference in per cent error between the RD and CC curves between 60 and 70%. For the cohort, the CC model resulted in a mean decrease in error of 7.48% compared with the RD model, figure 5d. The CC model more closely matches the in vivo observed distribution (figure 5e, SSE = 1.32 × 10−2) compared to the RD model (SSE = 2.83 × 10−1). The RD model results in a distribution of  with approximately 36% of its voxels with values less than 90% of the carrying capacity, whereas approximately 73% of the

with approximately 36% of its voxels with values less than 90% of the carrying capacity, whereas approximately 73% of the  and

and  voxels have values less than 90% of the carrying capacity.

voxels have values less than 90% of the carrying capacity.

Figure 5.

Local error comparison for RD and CC models. Panels (a–c) show the per cent error in cell number (mean ± 95% CI) versus the voxel cell number as a percentage of the maximum carrying capacity for rats 3, 7 and 10 on day 16. The red lines represent the RD model, while the blue lines represent the CC model. The RD model has increased error at lower numbers (i.e. less than 80% of the carrying capacity), while the CC model has reduced error at all cell numbers. Panel (d) shows the results for the entire cohort (mean ± 95% CI). There are significant differences in the error distributions at each cell value. Panel (e) shows the distribution of cell number for the RD, CC and measured N (black lines) at day 16. (Online version in colour.)

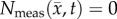

4.4. Combined model (MC–CC)

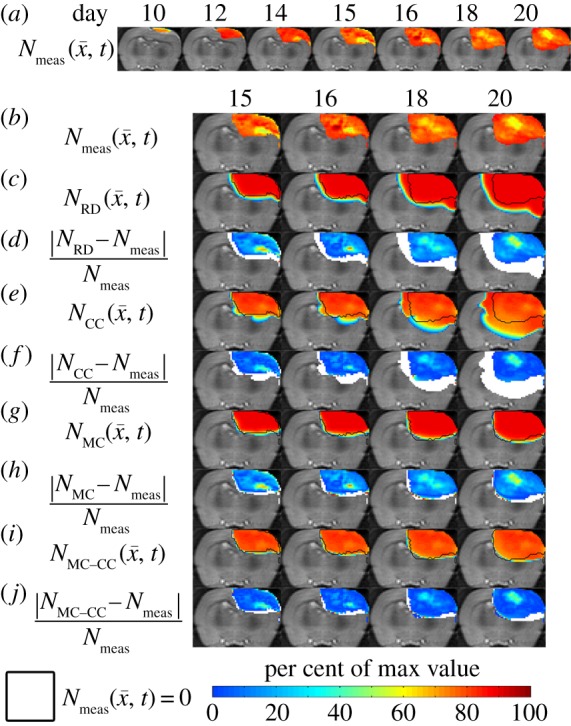

Figures 6–8 show the results of the global and local error analysis for the MC–CC model. Figure 6 shows at day 20, the RD and MC models (figure 6c,g, respectively) both fail to capture the low cell-density regions seen within  resulting in high local level error (15.95 ± 0.89% and 17.01 ± 1.14%, respectively). Conversely, the CC and MC–CC models (figure 6e,i, respectively) capture some low cellularity regions in

resulting in high local level error (15.95 ± 0.89% and 17.01 ± 1.14%, respectively). Conversely, the CC and MC–CC models (figure 6e,i, respectively) capture some low cellularity regions in  resulting in decreased local level errors (7.96 ± 0.79% and 9.05 ± 0.96%, respectively). Increased error in cell number is observed in the centre of the tumour (greater than 40%) compared to the periphery (less than 10%). All four models have low global level errors at day 15 (less than 16%). At days 18 and 20, however, the RD and CC models overestimate tumour growth (greater than 41%) compared to the MC and MC–CC models (less than 6%). Visually, it is evident that the MC–CC model combines the benefits of both the MC (low global level errors) and CC (low local level errors) models in predicting future tumour growth.

resulting in decreased local level errors (7.96 ± 0.79% and 9.05 ± 0.96%, respectively). Increased error in cell number is observed in the centre of the tumour (greater than 40%) compared to the periphery (less than 10%). All four models have low global level errors at day 15 (less than 16%). At days 18 and 20, however, the RD and CC models overestimate tumour growth (greater than 41%) compared to the MC and MC–CC models (less than 6%). Visually, it is evident that the MC–CC model combines the benefits of both the MC (low global level errors) and CC (low local level errors) models in predicting future tumour growth.

Figure 6.

Rows (a,b) show the measured cell number,  , while rows (c–j) show

, while rows (c–j) show  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  for rat 1. The black outlines on rows (c,e,g,i) represent the boundaries of

for rat 1. The black outlines on rows (c,e,g,i) represent the boundaries of  , whereas the white spaces on rows (d,f,h,j) represent areas where

, whereas the white spaces on rows (d,f,h,j) represent areas where  was equal to zero. The RD model, rows (c,d), overestimates tumour size and fails to depict low cellularity regions within the tumour. The CC model, rows (e,f), also overestimates tumour size but it has reduced errors in cellularity. The MC model, rows (g,h), has reduced error in tumour size but has higher error compared with the CC model. Both the global and local errors are reduced in the MC–CC model, rows (i, j), compared to the RD model. (Online version in colour.)

was equal to zero. The RD model, rows (c,d), overestimates tumour size and fails to depict low cellularity regions within the tumour. The CC model, rows (e,f), also overestimates tumour size but it has reduced errors in cellularity. The MC model, rows (g,h), has reduced error in tumour size but has higher error compared with the CC model. Both the global and local errors are reduced in the MC–CC model, rows (i, j), compared to the RD model. (Online version in colour.)

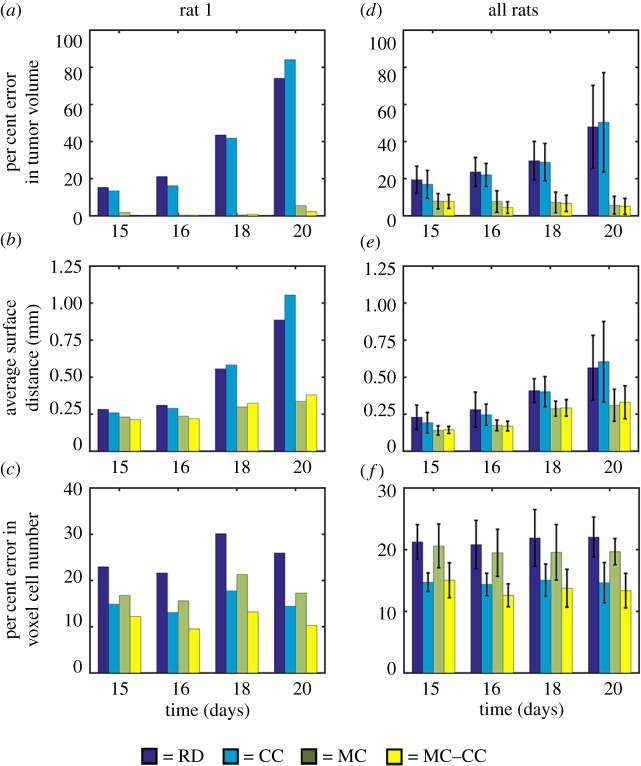

Figure 7.

Global and local error results for all models. Per cent error in tumour volume, panels (a,d), the average surface distance, panels (b,e), and the per cent error in voxel cell number, panels (c,f), are shown for rat 1, panels (a–c), and all rats, panels (d–f). For rat 1, increased global level error, panels (a,b), is observed for the RD and CC models compared to the MC and MC–CC models. Similarly, increased local error is observed, panel (c), for the RD and MC models compared to the CC and MC–CC models. Similar results were observed for the cohort. The mean and 95% CI are shown in panels (d–f). Increased error was observed in tumour volume, panel (d), for the RD and CC models (greater than 16%) compared to the MC and MC–CC models (less than 8%). Elevated average surface distances, panel (e), were also observed for the RD and CC models. Less than 16% error was observed at the local level, panel (f), for the CC and MC–CC models. (Online version in colour.)

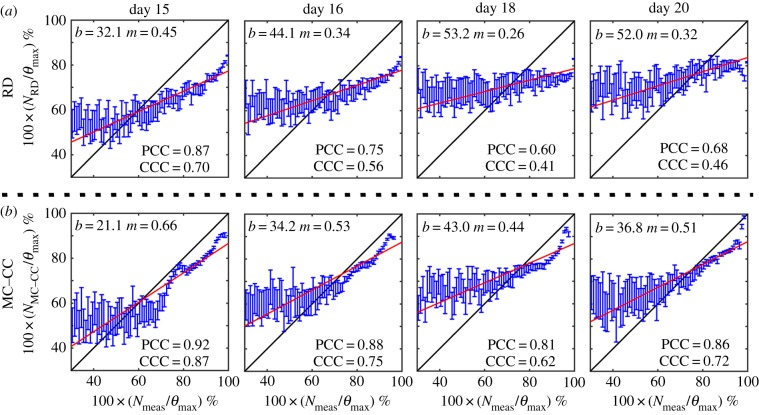

Figure 8.

Comparison of model and measured voxel cell number for the RD and MC–CC models. Cell number as a percentage of the maximum carrying capacity for the RD model, panel (a), and the MC–CC model, panel (b), are plotted against the measured cell number as a percentage of the maximum carrying capacity on days 15, 16, 18 and 20. The blue dots represent the mean  and 95% CI for a given

and 95% CI for a given  . The black lines represent the line of unity, while the red lines represent the results of linear regression (b = y-intercept, m = slope). The PCC and CCC for each model are reported within the plot. Both the RD and MC–CC models showed a decreased level of agreement (CCC) and correlation (PCC) from day 15 to 20. The MC–CC model, however, had an increased level of agreement (at day 20; CCC(MC–CC) = 0.72 versus CCCRD = 0.46) and correlation (at day 20; PCC(MC–CC) = 0.86 versus PCCRD = 0.68) at all days. (Online version in colour.)

. The black lines represent the line of unity, while the red lines represent the results of linear regression (b = y-intercept, m = slope). The PCC and CCC for each model are reported within the plot. Both the RD and MC–CC models showed a decreased level of agreement (CCC) and correlation (PCC) from day 15 to 20. The MC–CC model, however, had an increased level of agreement (at day 20; CCC(MC–CC) = 0.72 versus CCCRD = 0.46) and correlation (at day 20; PCC(MC–CC) = 0.86 versus PCCRD = 0.68) at all days. (Online version in colour.)

Figure 7a–c shows global and local errors applied to the complete tumour volume for rat 1, while figure 7d–f shows the analogous results for the cohort. Less than 6% error in tumour volume, figure 7a, was observed for the MC models (MC and MC–CC) at all time points, whereas the non-MC models (RD and CC) had errors in tumour volume ranging from 13.42% to 84.12%. All models had low average surface distances less than 0.31 mm, figure 7b, at days 15 and 16. Conversely, on day 20 the RD and CC models had ASDs greater than 0.89 mm compared with the MC and MC–CC models which had ASDs less than 0.40 mm. The RD and MC models both had increased error ranging from 16.13 to 30.12% in voxel cell number, figure 7c, compared to the CC and MC–CC models which ranged from 9.55 to 17.75%.

Similar results are seen in the cohort (figure 7d–f). The non-MC models resulted in increasing volume error, figure 7d, over time ranging from 16.08 to 50.37%, whereas the MC models had less than 8% error in tumour volume estimates. Similarly, figure 7e shows that the MC and MC–CC models both have decreased average surface distances ranging from 0.15 to 0.33 mm compared with the RD and CC models which ranged from 0.19 to 0.60 mm. Models with a voxel-specific carrying capacity (CC and MC–CC models) reduced local level error, figure 7f, from greater than 19.92% error (RD and MC models) to less than 15.04% error (CC and MC–CC models).

The results of the pairwise testing following statistically significant ANOVA results (p < 0.05) indicated that the MC and MC–CC models had significantly reduced error in tumour volume at all time points compared to the RD model. Similarly, the MC and MC–CC models had significantly reduced error in tumour volume at days 16, 18 and 20 compared with the CC model. For local level error (error in voxel cell number), the CC and MC–CC models had significantly reduced error at all time points compared to the RD model. Additionally, the MC–CC model had reduced local error compared with the MC model at days 15, 16 and 20. No significant differences (p-values for F-test ranged from 0.053 to 0.193) were observed between model values of ASD.

Figure 8 shows the PCC and CCC results for the RD and MC–CC models. Figure 8a shows a reduction in correlation and agreement between  and

and  from day 15 (PCC = 0.87, CCC = 0.70) to 20 (PCC = 0.68, CCC = 0.46). Figure 8b also shows decreased correlation and agreement between

from day 15 (PCC = 0.87, CCC = 0.70) to 20 (PCC = 0.68, CCC = 0.46). Figure 8b also shows decreased correlation and agreement between  and

and  from day 15 (PCC = 0.92, CCC = 0.87) to 20 (PCC = 0.86, CCC = 0.72). The MC–CC model resulted in an increased level of agreement and correlation at all time points compared to the RD model.

from day 15 (PCC = 0.92, CCC = 0.87) to 20 (PCC = 0.86, CCC = 0.72). The MC–CC model resulted in an increased level of agreement and correlation at all time points compared to the RD model.

5. Discussion

The results of the model analysis showed that global error can be significantly improved by coupling local tissue stress to tumour cell diffusion and that local error can be improved by fitting for a voxel-specific carrying capacity. Global error analysis showed that the MC models (MC, MC–CC) were significantly more accurate in describing tumour volume than the RD and CC models. Generally, global level error for the MC models (MC, MC–CC) remained relatively constant from days 15 to 20 compared to the non-MC models (RD, CC) which grew from days 15 to 20. This suggests that the MC model could potentially provide better global level predictions past day 20 compared to the non-MC models. The local level analysis showed that incorporating a voxel-specific carrying capacity (CC, MC–CC) reduced local level error compared with when a global value was used (RD, MC). The MC–CC model benefits from both a reduced global level error (lower error in tumour volume, lower ASD) provided by the MC component of the model and reduced local level error (less error in local cell number) provided by the CC component of the model. Additionally, a strong level of agreement and correlation, compared to the RD model, was observed between the MC–CC model and measured cell number at the voxel level. This work demonstrates that individualized model predictions can be made accurately using parameters estimated from a subject's own imaging measurements.

To evaluate the model-prediction framework we used a pre-clinical model of glioma (the C6 line) injected orthotopically in rats. This experimental system provides a well-controlled setting to perform imaging and modelling experiments (e.g. repeatable growth characteristics, more frequent observation, relatively easy to region to register). However, other cell lines should also be investigated, especially those which more closely mimic human gliomas such as patient-derived xenografts. We would expect the estimated model parameters to implicitly capture variations in tumour biology; however, additional terms may need to be added to explicitly recapitulate unique tumour features. In the present work, we focused primarily on incorporating mechanical forces and intra-tumour heterogeneity, but it should be noted that other factors such as tumour vascularization and the interaction with the surrounding microenvironment are likely to have a significant influence on tumour growth and should be considered in future efforts.

Mechanical forces play a critical role in the growth of tumours [20,21] and the interaction with these forces needs to be considered in the development of accurate mathematical models. Cancer development results in complex changes to the mechanical microenvironment between a tumour and its supporting stroma and is likely to affect the growth and invasion of tumour growth [41–43]. We have focused on the inhibitory role of local mechanical stress on gross tumour growth [18]. Without mechanical coupling, error in predicted tumour volume worsens over time (increasing approx. threefold from days 15 to 20). The results of this model analysis, suggested that incorporating an MC tumour cell diffusion coefficient is critical for accurately predicting gross tumour growth. It results in significant decreases in global level error (per cent error in tumour volume) when compared to the RD model. Furthermore, the gross inhibitory effect of local tissue stress observed modelled here accurately describes in vivo C6 glioma growth. One of the limitations of this current study is that the shear modulus was uniquely assigned to only a few identifiable regions based on literature values. While this current approach still results in reduced global level errors due to inhibitory effect of the MC model [21], a more tissue-specific approach could potentially more accurately describe glioma morphology [44]. More accurate assignment of these tissue-specific properties (via, for example, magnetic resonance elastography after tumour implantation [45]) may improve the predictions of future tumour morphology. These results suggest the importance of mechanical forces on accurate tumour growth predictions. Other efforts have included the influence of mechanical forces on prediction of breast [5], pancreatic [46] and kidney [24] cancers. This model could be adapted for other cell lines or human cancers using a different degree of coupling by changing λ1.

Mathematically modelling cell interactions at the local level is a large field [28,47–50] with complexity ranging from a single equation to models with several coupled equations. However, parametrizing these models in a subject/tumour-specific approach often would require highly invasive measurements to accurately capture the in vivo behaviour. In this work, a simple alteration of the RD model to include a voxel-specific carrying capacity resulted in reduced local level errors. For the RD and MC models, θ is based on voxel dimension and average tumour cell size. In the CC model, the voxel-specific  is, in essence, a snapshot of the cumulative effects of both physical restrictions and environmental limitations. The analysis of the CC model suggests that it is significantly better at describing in vivo C6 glioma behaviour. The CC model allows for changes in existing low cell-density regions to be more accurately described (figure 4). Furthermore, the CC model is significantly more accurate in capturing the cell number distribution (figure 5e) observed in vivo. The CC model does, however, fail to capture expanding low cellularity regions as seen in figure 6 which is one of the main limitations to this model. Since

is, in essence, a snapshot of the cumulative effects of both physical restrictions and environmental limitations. The analysis of the CC model suggests that it is significantly better at describing in vivo C6 glioma behaviour. The CC model allows for changes in existing low cell-density regions to be more accurately described (figure 4). Furthermore, the CC model is significantly more accurate in capturing the cell number distribution (figure 5e) observed in vivo. The CC model does, however, fail to capture expanding low cellularity regions as seen in figure 6 which is one of the main limitations to this model. Since  is temporally constant, which if it is truly a function of physical and environmental limitations may not be accurate, a higher error may be observed in future predictions if necrotic regions develop. The CC model provides improved local level error for voxels that are saturated in the RD model.

is temporally constant, which if it is truly a function of physical and environmental limitations may not be accurate, a higher error may be observed in future predictions if necrotic regions develop. The CC model provides improved local level error for voxels that are saturated in the RD model.  calibrates the model to adjust the differences between the calculated physical carrying capacity and the observed cell density. In future work, we plan to investigate the sensitivity of our model parameters to real change in cell density versus experimental noise. At this time, we do not know what degree of change in, for example,

calibrates the model to adjust the differences between the calculated physical carrying capacity and the observed cell density. In future work, we plan to investigate the sensitivity of our model parameters to real change in cell density versus experimental noise. At this time, we do not know what degree of change in, for example,  represents a significant change over the measurement noise. However, in voxels where

represents a significant change over the measurement noise. However, in voxels where  is decreasing over time (potentially due to necrosis) we would have worsening error as

is decreasing over time (potentially due to necrosis) we would have worsening error as  continues to decrease. One potential solution is to develop a more complicated and explicit relationship between θ and physical limitations (vasculature space [27,28], edema [51], non-tumour cells [52]) and environmental limitations (availability of glucose and oxygen [47], acidity [52]) that could be evolved temporally as these conditions change. However, it is important to note that such modifications would likely require additional model assumptions and parameters that need additional data sources to define. A second limitation of the CC model is that it requires two sets of voxel-specific parameters (

continues to decrease. One potential solution is to develop a more complicated and explicit relationship between θ and physical limitations (vasculature space [27,28], edema [51], non-tumour cells [52]) and environmental limitations (availability of glucose and oxygen [47], acidity [52]) that could be evolved temporally as these conditions change. However, it is important to note that such modifications would likely require additional model assumptions and parameters that need additional data sources to define. A second limitation of the CC model is that it requires two sets of voxel-specific parameters ( and

and  ) and two global parameters (D for white and grey matter) which may be challenging to accurately estimate in a data limited situation. Model selection criteria [53,54] that balance the goodness of fit and model complexity should be used to determine whether a more complex model is preferred for specific disease settings. Estimating a global carrying capacity may also provide some of the benefit of the locally estimated carrying capacity to account for variations in carrying capacity between disease settings. A spatial regularization process to enforce local continuity (as nearby voxels are likely to influence each other) may improve the convergence and result in a more robust optimization. However, we elected to use a data-driven approach to estimating model parameters rather than constraining our approach with an unknown correlation that is as of yet arbitrarily assigned.

) and two global parameters (D for white and grey matter) which may be challenging to accurately estimate in a data limited situation. Model selection criteria [53,54] that balance the goodness of fit and model complexity should be used to determine whether a more complex model is preferred for specific disease settings. Estimating a global carrying capacity may also provide some of the benefit of the locally estimated carrying capacity to account for variations in carrying capacity between disease settings. A spatial regularization process to enforce local continuity (as nearby voxels are likely to influence each other) may improve the convergence and result in a more robust optimization. However, we elected to use a data-driven approach to estimating model parameters rather than constraining our approach with an unknown correlation that is as of yet arbitrarily assigned.

The combined model, MC–CC, provides the best description of the in vivo C6 glioma growth by reducing both global and local level errors. The MC–CC model also shows a very high level of agreement and correlation to the in vivo observed cell number. Furthermore, statistically significant differences between the RD and MC–CC models were observed for both the global and local level metrics. This model is not intended (as-is) to be applied directly to clinical glioma cases which would require additional modification of the model system to account for patient-specific therapeutic interventions. However, our approach could be used as an accurate individualized control against which novel treatments or treatment schedules could be evaluated. In the pre-clinical setting, this model could be used as the foundation for the inclusion of the effects of radiation or chemotherapy that could be used to investigate novel approaches to delivering these therapies. Depending on the quantity of interest, the MC model may be sufficient to provide estimates of tumour volume and location without adding an additional spatially varying model parameter.

There are, however, some key underlying limitations for all of the modelling approaches discussed in this work. First, we use the measured ADC to estimate cellularity at the voxel level. While several studies have shown a strong correlation between histological estimates of cellularity in human brain tumours [55] (r = 0.77, p = 0.007), breast cancer [56] (r = 0.54, p

< 0.01), extracranial lesions [57] (r = 0.73, p < 0.001), small animal models of breast cancer [37] (r > 0.57, p = 0.03), and in vitro studies [36], there are other factors (cell membrane permeability [58], cell size, tortuosity [59], oedema [60] and necrosis [60]) which can also effect the measured ADC. Thus, this transformation (i.e. equation (3.1)) from ADC to cellularity is a first-order approximation to the true tumour cellularity. A second limitation of this work is the quantity of imaging measurements that are needed to estimate model parameters. In data limited settings (e.g. standard-of-care clinical studies), our approach will not be tenable. A third limitation of note is that our current model does not provide a means to explicitly alter  and

and  as a function of time. It is important for future work to explicitly alter

as a function of time. It is important for future work to explicitly alter  and

and  as a function of time; however, developing a system of equations that can accurately capture this dynamic process will be challenging. We are currently working to address this fundamental shortcoming of the model.

as a function of time; however, developing a system of equations that can accurately capture this dynamic process will be challenging. We are currently working to address this fundamental shortcoming of the model.

6. Conclusion

The standard RD model poorly predicts the spatio-temporal evolution of in vivo C6 glioma growth in rats resulting in high global and local level errors. Comparing across figures 6c–i and 7, it is clear that mechanically coupling local tissue stress to tumour cell movement is a fundamental requirement towards accurate tumour growth models. While more subtle, figure 8f demonstrates that a voxel-specific carrying capacity is likely a necessary ingredient for improving local predictions of the cellular heterogeneity within tumours. Lastly, even though these models lack the prediction of specific tumour-to-tissue infiltrative shape as expressed by the average surface distance, the MC–CC model can provide accurate short- and long-term predictions on a rat-specific basis. The MC–CC model provides a more complete description of in vivo C6 glioma growth in rats compared with the standard RD model.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at The University of Texas at Austin for providing high performance computing resources that have contributed to this research. The authors thank Dr Zou Yue for performing the animal surgeries and Dr Daniel C. Colvin for assistance with the image registration.

Ethics

All experimental procedures were approved by Vanderbilt University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Authors' contributions

D.A.H. performed the experimental work, data analysis, study design, and drafted the manuscript; J.A.W. and S.L.B. participated in data analysis, design of the study and drafted the manuscript; M.I.M., E.C.R., V.Q. and T.E.Y. participated in conceiving the study and drafted the manuscript.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported through funding from the National Cancer Institute R01CA138599, U01CA174706, K25CA204599, CPRIT RR160005, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R01NS049251 and the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (NIH P30CA68485). E.C.R. holds a Career Award from the BWF. This work was partially supported by a pilot project from the Physical Sciences in Oncology Center at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center (PIs: Robert Gatenby MD, Robert Gillies PhD).

References

- 1.Yankeelov TE, Atuegwu N, Hormuth D, Weis JA, Barnes SL, Miga MI, Rericha EC, Quaranta V. 2013. Clinically relevant modeling of tumor growth and treatment response. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 187ps9–187ps9. ( 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005686) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hormuth DA II, Weis JA, Barnes SL, Miga MI, Rericha EC, Quaranta V, Yankeelov TE. 2015. Predicting in vivo glioma growth with the reaction diffusion equation constrained by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging data. Phys. Biol. 12, 46006 ( 10.1088/1478-3975/12/4/046006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atuegwu NC, Gore JC, Yankeelov TE. 2010. The integration of quantitative multi-modality imaging data into mathematical models of tumors. Phys. Med. Biol. 55, 2429–2449. ( 10.1088/0031-9155/55/9/001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weis JA, et al. 2013. A mechanically coupled reaction-diffusion model for predicting the response of breast tumors to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 58, 5851–5866. ( 10.1088/0031-9155/58/17/5851) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weis JA, et al. 2015. Predicting the response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant therapy using a mechanically coupled reaction-diffusion model. Cancer Res. 75, 4697–4707. ( 10.1158/0008-5472) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atuegwu NC, Arlinghaus LR, Li X, Welch EB, Chakravarthy BA, Gore JC, Yankeelov TE. 2011. Integration of diffusion-weighted MRI data and a simple mathematical model to predict breast tumor cellularity during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Magn. Reson. Med. 66, 1689–1696. ( 10.1002/mrm.23203) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weis JA, Miga MI, Yankeelov TE. 2017. Three-dimensional image-based mechanical modeling for predicting the response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant therapy. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 314, 494–512. ( 10.1016/j.cma.2016.08.024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harpold HLP, Alvord EC, Swanson KR. 2007. The evolution of mathematical modeling of glioma proliferation and invasion. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 66, 1–9. ( 10.1097/nen.0b013e31802d9000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Sadowski SM, Weisbrod AB, Kebebew E, Summers RM, Yao J. 2014. Patient specific tumor growth prediction using multimodal images. Med. Image Anal. 18, 555–566. ( 10.1016/j.media.2014.02.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clatz O, Sermesant M, Bondiau P-Y, Delingette H, Warfield SK, Malandain G, Ayache N. 2005. Realistic simulation of the 3-D growth of brain tumors in MR images coupling diffusion with biomechanical deformation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 24, 1334–1346. ( 10.1109/TMI.2005.857217) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogea C, Davatzikos C, Biros G. 2008. An image-driven parameter estimation problem for a reaction-diffusion glioma growth model with mass effects. J. Math. Biol. 56, 793–825. ( 10.1007/s00285-007-0139-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jbabdi S, Mandonnet E, Duffau H, Capelle L, Swanson KR, Pélégrini-Issac M, Guillevin R, Benali H. 2005. Simulation of anisotropic growth of low-grade gliomas using diffusion tensor imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 54, 616–624. ( 10.1002/mrm.20625) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiroishi MS, et al. 2015. Principles of T2*-weighted dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI technique in brain tumor imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 41, 296–313. ( 10.1002/jmri.24648) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yankeelov TE, et al. 2009. Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in oncology: theory, data acquisition, analysis, and examples. Curr. Med. Imaging Rev. 3, 91–107. ( 10.2174/157340507780619179) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh DM, Collins DJ. 2007. Diffusion-weighted MRI in the body: applications and challenges in oncology. Am. J. Roentgenol. 188, 1622–1635. ( 10.2214/AJR.06.1403) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelloff GJ, et al. 2005. Progress and promise of FDG-PET imaging for cancer patient management and oncologic drug development. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 2785–2808. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2626) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imam SK. 2010. Review of positron emission tomography tracers for imaging of tumor hypoxia. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 25, 365–374. ( 10.1089/cbr.2009.0740) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg I, Miga MI. 2008. Preliminary investigation of the inhibitory effects of mechanical stress in tumor growth. Proc. SPIE 6918, 69182L ( 10.1117/12.773376) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong KCL, Summers RM, Kebebew E, Yao J. 2015. Tumor growth prediction with reaction-diffusion and hyperelastic biomechanical model by physiological data fusion. Med. Image Anal. 25, 72–85. ( 10.1016/j.media.2015.04.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain RK, Martin JD, Stylianopoulos T. 2014. The role of mechanical forces in tumor growth and therapy. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16, 321–346. ( 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071813-105259) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helmlinger G, Netti PA, Lichtenbeld HC, Melder RJ, Jain RK. 1997. Solid stress inhibits the growth of multicellular tumor spheroids. Nat. Biotechnol. 15, 778–783. ( 10.1038/nbt0897-778) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng G, Tse J, Jain RK, Munn LL. 2009. Micro-environmental mechanical stress controls tumor spheroid size and morphology by suppressing proliferation and inducing apoptosis in cancer cells. PLoS ONE 4, e4632 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0004632) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gooya A, Biros G, Davatzikos C. 2011. Deformable registration of glioma images using em algorithm and diffusion reaction modeling. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 30, 375–390. ( 10.1109/TMI.2010.2078833) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Summers RM, Yao J. 2013. Kidney tumor growth prediction by coupling reaction-diffusion and biomechanical model. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 60, 169–173. ( 10.1109/TBME.2012.2222027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piotrowska MJ, Angus SD. 2009. A quantitative cellular automaton model of in vitro multicellular spheroid tumour growth. J. Theor. Biol. 258, 165–178. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.02.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swanson KR, Rockne RC, Claridge J, Chaplain MA, Alvord EC, Anderson ARA. 2011. Quantifying the role of angiogenesis in malignant progression of gliomas: in silico modeling integrates imaging and histology. Cancer Res. 71, 7366–7375. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1399) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atuegwu NC, Arlinghaus LR, Li X, Chakravarthy AB, Abramson VG, Sanders ME, Yankeelov TE. 2013. Parameterizing the logistic model of tumor growth by DW-MRI and DCE-MRI data to predict treatment response and changes in breast cancer cellularity during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Transl. Oncol. 6, 256–264. ( 10.1593/tlo.13130) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkins-Daarud A, Rockne RC, Anderson ARA, Swanson KR. 2013. Modeling tumor-associated edema in gliomas during anti-angiogenic therapy and its impact on imageable tumor. Front. Oncol. 3, 66 ( 10.3389/fonc.2013.00066) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atuegwu NC, Colvin DC, Loveless ME, Xu L, Gore JC, Yankeelov TE. 2012. Incorporation of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging data into a simple mathematical model of tumor growth. Phys. Med. Biol. 57, 225–240. ( 10.1088/0031-9155/57/1/225) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon VD, et al. 2003. Measuring the mechanical stress induced by an expanding multicellular tumor system: a case study. Exp. Cell Res. 289, 58–66. ( 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00256-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elkin BS, Ilankovan AI, Morrison B. 2011. A detailed viscoelastic characterization of the P17 and adult rat brain. J. Neurotrauma 28, 2235 ( 10.1089/neu.2010.1604) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SJ, King MA, Sun J, Xie HK, Subhash G, Sarntinoranont M. 2014. Measurement of viscoelastic properties in multiple anatomical regions of acute rat brain tissue slices. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 29, 213–224. ( 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.08.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korobenko L, et al. 2009. A logistic model with a carrying capacity driven diffusion. Can. Appl. Math. Q. 17, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barth R, Kaur B. 2009. Rat brain tumor models in experimental neuro-oncology: the C6, 9 L, T9, RG2, F98, BT4C, RT-2 and CNS-1 gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 94, 299–312. ( 10.1007/s11060-009-9875-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whisenant JG, Ayers GD, Loveless ME, Barnes SL, Colvin DC, Yankeelov TE. 2014. Assessing reproducibility of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging studies in a murine model of HER2+ breast cancer. Magn. Reson. Imaging 32, 245–249. ( 10.1016/j.mri.2013.10.013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson AW, Xie J, Pizzonia J, Bronen RA, Spencer DD, Gore JC. 2000. Effects of cell volume fraction changes on apparent diffusion in human cells. Magn. Reson. Imaging 18, 689–695. ( 10.1016/S0730-725X(00)00147-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnes SL, Sorace AG, Loveless ME, Whisenant JG, Yankeelov TE. 2015. Correlation of tumor characteristics derived from DCE-MRI and DW-MRI with histology in murine models of breast cancer. NMR Biomed. 28, 1345–1356. ( 10.1002/nbm.3377) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin I, Dozin B, Quarto R, Cancedda R, Beltrame F. 1997. Computer-based technique for cell aggregation analysis and cell aggregation in in vitro chondrogenesis. Cytometry 28, 141–146. ( 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19970601)28:2%3C141::AID-CYTO7%3E3.0.CO;2-I) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rouzaire-Dubois B, Milandri JB, Bostel S, Dubois JM. 2000. Control of cell proliferation by cell volume alterations in rat C6 glioma cells. Pflugers Arch. 440, 881–888. ( 10.1007/s004240000371) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch D. 2005. Numerical partial differential equations for environmental scientists and engineers: a first practical course. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paszek MJ, et al. 2005. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell 8, 241–254. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagelkerke A, Bussink J, Rowan AE, Span PN. 2015. The mechanical microenvironment in cancer: how physics affects tumours. Semin. Cancer Biol. 35, 62–70. ( 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.09.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim Y, Stolarska MA, Othmer HG. 2011. The role of the microenvironment in tumor growth and invasion. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 106, 353–379. ( 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.06.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doblas S, He T, Saunders D, Pearson J, Hoyle J, Smith N, Lerner M, Towner RA. 2010. Glioma morphology and tumor-induced vascular alterations revealed in seven rodent glioma models by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging and angiography. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 32, 267–275. ( 10.1002/jmri.22263) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huston J., III 2014. Magnetic resonance elastography of the brain. In Magnetic resonance elastography (eds SK Venkatesh, RL Ehman), pp. 89–98. New York, NY: Springer; ( 10.1007/978-1-4939-1575-0_8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong KCL, Summers RM, Kebebew E, Yao J. 2017. Pancreatic tumor growth prediction with elastic-growth decomposition, image-derived motion, and FDM-FEM coupling. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 36, 111–123. ( 10.1109/TMI.2016.2597313) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerlee P, et al. 2007. An evolutionary hybrid cellular automaton model of solid tumour growth. J. Theor. Biol. 246, 583–603. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.01.027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]