Abstract

Objectives

The International Collaboration for a Life Course Approach to Reproductive Health and Chronic Disease Events (InterLACE) project is a global research collaboration that aims to advance understanding of women’s reproductive health in relation to chronic disease risk by pooling individual participant data from several cohort and cross-sectional studies. The aim of this paper is to describe the characteristics of contributing studies and to present the distribution of demographic and reproductive factors and chronic disease outcomes in InterLACE.

Study design

InterLACE is an individual-level pooled study of 20 observational studies (12 of which are longitudinal) from ten countries. Variables were harmonized across studies to create a new and systematic synthesis of life-course data.

Main outcome measures

Harmonized data were derived in three domains: 1) socio-demographic and lifestyle factors, 2) female reproductive characteristics, and 3) chronic disease outcomes (cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes).

Results

InterLACE pooled data from 229,054 mid-aged women. Overall, 76% of the women were Caucasian and 22% Japanese; other ethnicities (of 300 or more participants) included Hispanic/Latin American (0.2%), Chinese (0.2%), Middle Eastern (0.3%), African/black (0.5%), and Other (1.0%). The median age at baseline was 47 years (Inter-quartile range (IQR): 41–53), and that at the last follow-up was 56 years (IQR: 48–64). Regarding reproductive characteristics, half of the women (49.8%) had their first menstruation (menarche) at 12–13 years of age. The distribution of menopausal status and the prevalence of chronic disease varied considerably among studies. At baseline, most women (57%) were pre- or peri-menopausal, 20% reported a natural menopause (range 0.8–55.6%) and the remainder had surgery or were taking hormones. By the end of follow-up, the prevalence rates of CVD and diabetes were 7.2% (range 0.9–24.6%) and 5.1% (range 1.3–13.2%), respectively.

Conclusions

The scale and heterogeneity of InterLACE data provide an opportunity to strengthen evidence concerning the relationships between reproductive health through life and subsequent risks of chronic disease, including cross-cultural comparisons.

Keywords: Baseline characteristics, Reproductive health, Chronic disease, Life-course research, Cross-cultural comparison, Harmonization

1. Introduction

Since chronic diseases are typically characterized by long latency and complex causal pathways, the clear sex differences evident in their risks [1] highlight the need to understand the role of reproductive characteristics and sex hormones in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) across life. For instance, women with diabetes have a 3.5-fold increased risk of mortality from coronary heart disease, compared with 2-fold for men with diabetes [1]. Some aspects of female reproductive health act as markers for increased risk of NCDs in later life, in that they may signal an underlying predisposition or sub-clinical conditions [2–4]. Early menarche is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease (CVD) [5,6], and breast cancer [7]. Early menarche is also linked to poor reproductive health outcomes across life, such as irregular menstrual cycles [8], but with better bone health in later life [9,10]. Similarly, early menopause increases the risk of having chronic diseases in later life including T2DM and CVD [11,12], while the vasomotor symptoms and longer duration of menopausal transition also represent a period of increased metabolic and cardiovascular risks [13,14]. Various lifestyle, socioeconomic, and cultural factors also influence reproductive characteristics and chronic disease risk [15–17]. A more detailed understanding of the complex relationships between these modifiable factors and reproductive characteristics is needed to support targeted gender-specific preventive strategies for chronic diseases. Previous research based on individual studies has been constrained by issues such as small sample size, lack of control for comorbidities, and lack of sufficient information on the racial/ethnic and cultural diversity of the study samples.

The International Collaboration for a Life Course Approach to Reproductive Health and Chronic Disease, or InterLACE, aims to advance the evidence base for women’s health policy by developing a collaborative research program that takes a comprehensive life course perspective of women’s reproductive health in relation to chronic disease risk [18]. Established in June 2012, InterLACE has pooled individual-level observational data on reproductive health and chronic disease from almost 230,000 women from 20 observational studies, mostly on women’s health, across ten countries. InterLACE offers an integrated approach for a more detailed understanding of the determinants and characteristics of reproductive health across the life course in diverse populations [18]. A life course perspective emphasizes the differential effects of exposures and events at different stages of life [19], which in turn can be reflected in models that capture the different types of biological, psychological, and social mechanisms at work [20].

Findings from InterLACE can therefore provide insights into causal pathways for disease aetiology [21] and have implications for the timing and targeting of preventive health interventions [22]. This will enable a more detailed description of reproductive function and ageing by quantifying the markers of reproductive health through life, such as age at menarche, parity, and age at menopause in different populations. The project will determine the extent to which these markers and overall trajectories of lifetime reproductive health are associated with future chronic disease risks such as T2DM and CVD. Through InterLACE, the relationships of lifestyle, cultural factors, and reproductive health with subsequent risk of chronic disease will be identified. Recommendations for future study designs to facilitate rigorous cross-cultural comparisons across longitudinal studies will also be presented. The aim of this paper is to present the overall demographic and reproductive characteristics and to describe the prevalence of T2DM and CVD in InterLACE.

2. Methods

2.1. Study recruitment

Twenty observational studies, twelve of which are longitudinal, currently provide data for InterLACE: Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH) [23], Healthy Ageing of Women Study (HOW) [24], Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS) [25], Danish Nurse Cohort Study (DNC) [26], Women’s Lifestyle and Health Study (WLH) [27], Medical Research Council (MRC) National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD) [28], National Child Development Study (NCDS) [29], English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) [30], UK Women’s Cohort Study (UKWCS) [31], Whitehall II study (WHITEHALL) [32], The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) [33], Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study (SMWHS) [34], Japan Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS) [35], Japanese Midlife Women’s Health Study (JMWHS) [24], Hilo Women’s Health Study (HILO) [36], San Francisco Midlife Women’s Health Study (SFMWHS) [37], and The Decision at Menopause Study (DAMES-USA [38], Lebanon [39], Spain [40], Morocco [41]). Participants in each study were recruited under Institutional Review Board protocols approved at each research centre and provided informed consent. Details of the study design, recruitment, and research aims for each study have been published elsewhere (see above for references). Brief descriptions of the 20 studies are given in Table 1, with their geographic scope shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Twenty studies contributing to the InterLACE dataset (n = 229,054).

| Study (abbreviation) | Location | Baseline survey year | Baseline sample | Median age at baseline (IQR) | No. of survey included | Latest survey yearc | Latest survey sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal data provided (n = 175,749) | |||||||

| Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s | Australia | 1996 | 13,715 | 48 (46–49) | 7 | 2013 | 9151 |

| Health (ALSWH) | |||||||

| Healthy Ageing of Women Study (HOW) | Australia | 2001 | 868 | 55 (52–57) | 3 | 2011 | 325 |

| Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS) | Australia | 1990–94 | 24,469 | 55 (48–62) | 3 | 2003–2006 | 16,615 |

| Danish Nurse Cohort Study (DNC) | Denmark | 1993/1999 | 28,731 | 50 (47–58) | 2 | 1999 | 24,155 |

| Women’s Lifestyle and Health Study (WLH) | Sweden/Norway | 1991–92 | 49,259 | 40 (35–45) | 2 | 2003–2004 | 34,402 |

| MRC National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD) | UK | 1993a | 1570 | 47a | 8 | 2000 | 1307 |

| National Child Development Study (NCDS) | UK | 2008a | 5274 | 50a | 2 | 2013 | 4635 |

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | UK | 2002–09 | 9118 | 58 (52–68) | 5 | 2010–2011 | 5649 |

| UK Women’s Cohort Study (UKWCS) | UK | 1995–98 | 35,522 | 51 (45–59) | 2 | 1999–2004 | 19,004 |

| Whitehall II (WHITEHALL) | UK | 1985–88 | 3413 | 45 (40–51) | 8 | 2006 | 2156 |

| The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) | USA | 1996 | 3302 | 46 (44–48) | 11 | 2006 | 2239 |

| Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study (SMWHS) | USA | 1990–92 | 508 | 41 (38–44) | 2 | 2000 | 194 |

| Cross-sectional data provided (n = 53,305) | |||||||

| Japan Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS) | Japan | 2001–2007 | 49,927 | 41 (35–47) | |||

| Japanese Midlife Women’s Health Study (JMWHS) | Japan | 2002 | 847 | N/A (45–60)b | |||

| Hilo Women’s Health Study (HILO) | USA | 2004–05 | 994 | 51 (46–56) | |||

| San Francisco Midlife Women’s Health Study (SFMWHS) | USA | 1996 | 347 | 43 (42–45) | |||

| The Decision at Menopause Study (DAMES-USA) | USA | 2001 | 293 | 50 (48–53) | |||

| The Decision at Menopause Study (DAMES-Lebanon) | Lebanon | 1997 | 298 | 50 (48–53) | |||

| The Decision at Menopause Study (DAMES-Spain) | Spain | 2002 | 300 | 50 (47–53) | |||

| The Decision at Menopause Study (DAMES-Morocco) | Morocco | 1998 | 299 | 49 (46–52) | |||

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable; IQR, interquartile range.

NSHD (1946 British Birth Cohort) and NCDS (1958 British Birth Cohort) first collected information on women’s health in 1993 (aged 47) and in 2008 (aged 50), respectively, so we used 1993 and 2008 as the baseline year for the InterLACE.

JMWHS provided age by category only, and 48% of women were aged more than 55 (age range: 45–60 years).

The latest survey data contributed to the InterLACE dataset.

Fig. 1.

Locations of the 20 studies contributing to the InterLACE study.

There are ten participating countries: Australia, Demark, Sweden, Norway, UK, USA, Japan, Lebanon, Spain, and Morocco.

The majority of studies began between 1990 and early 2000, with the exception of NSHD (1946 British Birth Cohort) and NCDS (1958 British Birth Cohort), in which participants (male and female) were recruited at birth. InterLACE used data from a sub-sample study of women’s health (n = 1570) from NSHD started in 1993 (and the baseline for InterLACE), when participants were aged 47 years, with annual follow-up surveys until 2000 (age 54 years) to capture timing of menopause, menopausal symptoms and menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) use [28]. Similarly, for NCDS we used data from the women’s health survey in 2008 (n = 5274) as the baseline when cohort members were aged 50 years and were followed up until 2013 for disease outcome.

The DNC and ELSA studies had multiple waves of recruitment. DNC first invited members of the Danish Nurses Organisation to participate in 1993, with both a follow-up and recruitment of additional nurses in 1999 [26]. ELSA commenced in 2002–03 (wave 1) with the original sample recruited from households that had earlier participated in the Health Survey for England (HSE) in 1998, 1999, and 2001 (wave 0) [30]. New cohorts that were recruited from households that had participated in HSE in 2001–04 and 2006 were added to the ELSA sample at wave 3 (2006–07) and wave 4 (2008–09), respectively. The baseline years used in InterLACE for DNC and ELSA were determined according to the year in which each participant was recruited.

The SWAN and SMWHS had different recruitment criteria at baseline. In SWAN, only women with at least one menstrual period in the previous three months, without surgical removal of the uterus and/or both ovaries, and without the current use of hormone therapy, were eligible. In SMWHS, only women without surgical removal of uterus or ovaries were eligible to participate.

2.2. Study variables

InterLACE invited all individual studies to provide relevant data including a list of variables, survey questionnaires, data dictionaries/formats, and protocols or standard operating procedures. The data were requested from the three key domains:

Socio-demographic and lifestyle factors: age, birth year, race/ethnicity, marital and employment status, the level of education, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, food and vegetable intakes, and the consumption of soy products were provided if available. Marital status, employment, and lifestyle variables were also available at multiple time points in some longitudinal studies and were all preserved, although only baseline data are presented here. Use of these exposure variables will vary depending on the research questions.

Female reproductive characteristics: studies provided some or all of the following self-reported markers of reproductive health through life: age at menarche, age at first birth, number of pregnancies, parity, timing and duration of oral contraceptive pill (OCP) use, MHT use, age at natural menopause, hysterectomy/oophorectomy, menopausal status, and menopausal symptoms (e.g. vasomotor symptoms and psychological symptoms) [20]. Time-varying reproductive variables such as hormone use, surgery history, menopausal status, and menopausal symptoms were also available at multiple surveys in the longitudinal studies.

Chronic disease outcomes: data on CVD (stroke and heart diseases including general heart disease, heart attack, heart failure and angina) and diabetes (Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes) were collected from self-reported survey questionnaires and linkage with national registries (for DNC, WLH and SMWHS). Four studies (JMWHS, DAMES-USA, Lebanon, and Spain) did not have data available on CVD or diabetes.

2.3. Data harmonization

Once individual-level datasets were received, data were checked for outliers and inconsistencies, and if present, data providers were queried and the issue resolved. Harmonization rules and recoding instructions were created for each variable. When multiple studies had more detailed but similar information available, extra variables were created to encompass this alternative format and benefit from the increased granularity. In general, categorical variables were collapsed into the simplest level of detail to incorporate information from as many studies as possible. For example, education categories varied from study to study. It was categorised into ≤10 years, 11–12 years, and >12 years. Harmonized education category of less or equal to 10 years corresponds to less than high school or Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) or General Certificate of Education Ordinary Level (GCE O-level) in the UK. Similarly, 11–12 years category corresponds to high school or GCE Advanced Level (A-level) in the UK, and >12 years corresponds to at least some college education including trade, certificate, vocational training, diploma, and university degree.

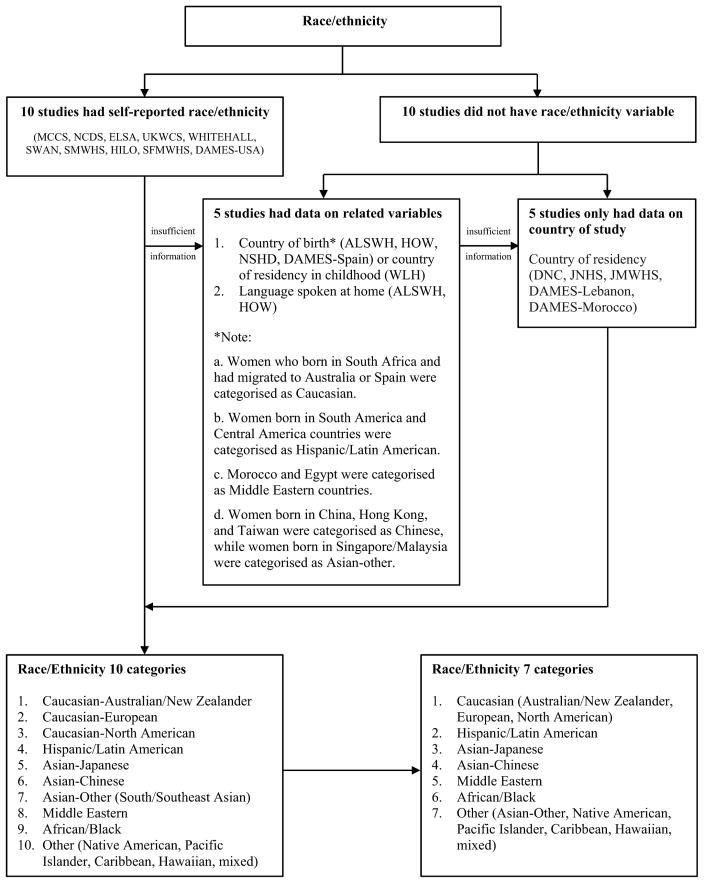

Harmonization of other specific variables such as race/ethnicity and menopausal status are presented in Figs. 2 and Fig. 3. In detail, participants self-identified their specific race/ethnicity and/or population subgroup in ten studies from which ethnicity variable was defined. Of the remaining ten studies, ethnic groups were defined based on country of birth and language spoken at home (5 studies), and where these were not available (DNC, JNHS, JMWHS, DAMES-Lebanon, and DAMES-Morocco), the country where the study was conducted was considered as a residency variable and used as a proxy for ethnicity [42]. In total, ten ethnic groups were defined: Caucasian-Australian/New Zealander, Caucasian-European, Caucasian-North American, His-panic/Latin American, Asian-Japanese, Asian-Chinese, Asian-Other (South/Southeast Asian), Middle Eastern, African/Black, and Other (Native American, Pacific Islander, Caribbean, Hawaiian, and Mixed). We then collapsed Australian/New Zealander, European, and North American together as Caucasian, and combined Asian-Other and Other.

Fig. 2.

Example of data harmonization to obtain common categories for race/ethnicity.

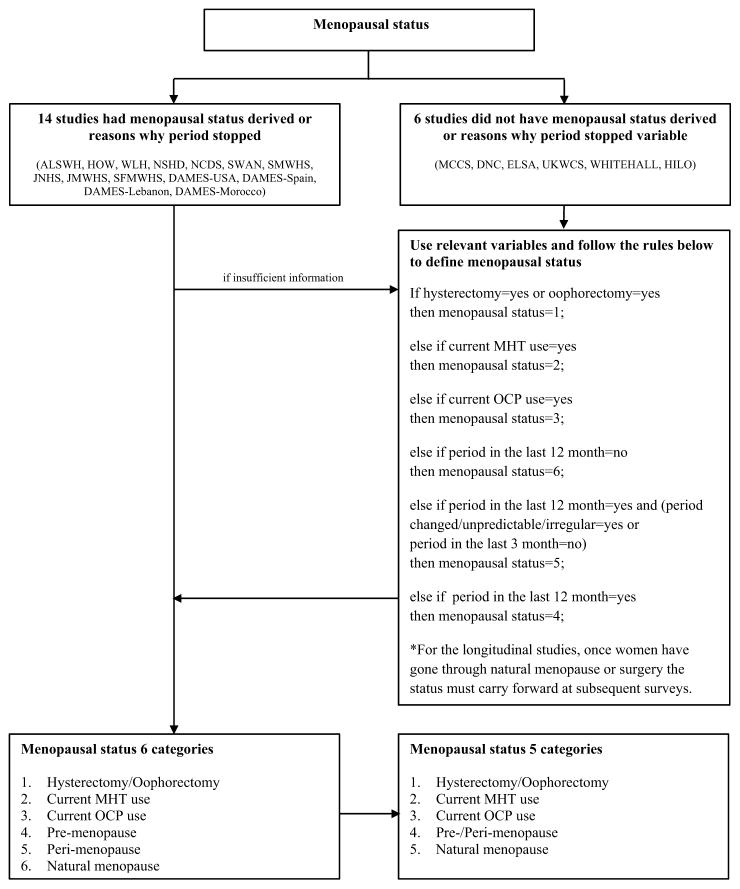

Fig. 3.

Example of data harmonization to obtain common categories for menopausal status.

Abbreviations: MHT, menopause hormone therapy; OCP, oral contraceptive pill.

To harmonize menopausal status at baseline, we first reviewed 14 studies that either had predefined menopausal status (pre-, peri-, or post-menopause) or reasons for the cessation of menses. Among them, those reporting current use of hormone therapy (unless natural menopause specifically reported) and hysterectomy/oophorectomy were categorised separately. As a result, we have six categories of menopausal status: hysterectomy/oophorectomy, current MHT use, current OCP use, pre-menopause, peri-menopause, and natural menopause. For all other women, where predefined menopausal status was not available, we used related variables (hysterectomy/oophorectomy, current use of hormone, menstrual period in the last 12 months, menstrual period in the last 3 months, and irregular or changeable period) using a consistent rule (Fig. 3) to assign them to one of the six groups defined above. In this way, each woman was provided with consistent and harmonized data on menopausal status at baseline. The same rules applied for the follow-up surveys. However once women had gone through natural menopause or surgery (hysterectomy/oophorectomy), their menopausal status remained throughout for any subsequent surveys. In addition to the harmonized menopausal status, more detailed information about the current and past use of MHT and OCP, hysterectomy, and unilateral/bilateral oophorectomy are available as separate variables. In this paper, we only present socio-demographic and reproductive characteristics at baseline, and show the cumulative prevalence of chronic disease outcomes over the study period. We used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) for all data management and analysis.

3. Results

The InterLACE dataset pooled individual-level data from 229,054 participants. Of the twenty studies currently comprising InterLACE, nine are national cohorts from Australia, the USA, the UK, Japan, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. The remaining state-based studies from specific cities or regions including San Francisco, Seattle, Hawaii, and Massachusetts in the USA; London, England; Melbourne and Queensland in Australia; Nagano, Japan; Beirut, Lebanon; Madrid, Spain; and Rabat, Morocco (Fig. 1). Twelve studies provided longitudinal data with at least two waves of surveys and five years of follow-up, while eight studies provided only cross-sectional baseline data (Table 1). For the majority of studies, women’s average age at baseline was between 40 and early 50 years with an overall median of 47 years (IQR: 41–53 years), with the exceptions of HOW, MCCS, and ELSA where the women were older at baseline (median ranging from 55 to 58 years). JMWHS only provided categorical age (≤55 or >55 years), and almost half (48%) of the women were more than 55 years of age.

Table 2 presents the distribution of some key harmonized demographic and reproductive variables by studies at baseline. Of the seven categories of ethnicity, Caucasian (75.5%, Australian/New Zealander 12.6%, European 61.7%, North American 1.2%) were the most prevalent, followed by Japanese (22.4%, mainly living in Japan (98.9%) but also some living in the USA). The remaining minority racial/ethnic groups included Hispanic/Latin American, Chinese, Middle Eastern, African/Blacks, and Others, with a minimum of 300 participants in each group. Within studies, four (SWAN, SMWHS, HILO, and SFMWHS) had a combination of multi-racial/ethnic samples. The level of education varied greatly between studies. Some variations were due to original study designs (e.g. study of nurses). However, this could also be reflecting regional variation in education. For example, DAMES-Morocco had a very small percentage of women (4%) with >12 years of education, while most US studies had over 75% at that level. Meanwhile, >12 years of education was significantly lower in NSHD compared with other UK studies. In most studies, the percentage of unmarried women was less than 10%, except for WHITEHALL and JNHS, which both had more than 20% single women. In WLH, more than double the average percentage of women (38.4%) were single because marital status was recorded from mother’s birth registry, so for those who had not given birth this information was missing. The overall prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) was 10%. In four studies (ELSA, SWAN, SFMWHS, and DAMES-USA) nearly 30% of women were obese, while the corresponding figure for Japanese studies (JMWHS and JNHS) was less than 2%.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and reproductive variables for the 20 studies.

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | Educationa (%) | Marital status (%) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Study | n | Caucasian | Hispanic/Latino | Asia-Japanese | Asia-Chinese | Middle Eastern | African/Black | Other | n | ≤10 years | 11–12 years | >12 years | n | Married/partnered | Separated/divorced/widowed | Never married/single |

| Overall | 229,054 | 75.5 | 0.2 | 22.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 223,733 | 29.4 | 11.7 | 58.9 | 197,768 | 69.6 | 14.6 | 15.8 |

| Longitudinal data | ||||||||||||||||

| ALSWH | 13,715 | 96.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | N/A | 2.8 | 13,577 | 50.1 | 16.8 | 33.1 | 13,647 | 82.9 | 13.9 | 3.3 |

| HOW | 868 | 96.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.5 | 859 | 52.4 | 15.9 | 31.7 | 861 | 76.4 | 19.3 | 4.3 |

| MCCS | 24,469 | 100 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24,465 | 63.0 | 9.2 | 27.8 | 23,391 | 69.3 | 22.2 | 8.5 |

| DNC | 28,731 | 100 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 28,731 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 28,484 | 69.8 | 20.0 | 10.2 |

| WLH | 49,259 | 100 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 48,755 | 29.7 | 28.4 | 41.9 | 23,727b | 60.2 | 1.4 | 38.4 |

| NSHD | 1570 | 100 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1482 | 70.4 | 23.8 | 5.8 | 1442 | 80.5 | 14.7 | 4.8 |

| NCDS | 5274 | 98.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.2 | 1.8 | 4546 | 62.5 | 10.4 | 27.1 | 4893 | 68.5 | 22.4 | 9.1 |

| ELSA | 9118 | 96.4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.5 | 3.0 | 8939 | 71.3 | 7.1 | 21.6 | 8979 | 65.3 | 29.4 | 5.4 |

| UKWCS | 35,522 | 98.7 | N/A | N/A | 0.1 | N/A | 0.1 | 1.1 | 32,320 | 48.2 | 12.1 | 39.7 | 34,818 | 75.0 | 17.4 | 7.6 |

| WHITEHALL | 3413 | 84.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 15.8 | 3008 | 55.3 | 16.3 | 28.5 | 3395 | 61.2 | 17.2 | 21.6 |

| SWAN | 3302 | 46.9 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 7.6 | N/A | 28.3 | N/A | 3271 | 7.3 | 17.8 | 75.0 | 3248 | 66.1 | 20.3 | 13.5 |

| SMWHS | 508 | 77.2 | 1.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 11.4 | 10.2 | 507 | 0.6 | 14.6 | 84.8 | 507 | 68.4 | 24.7 | 6.9 |

| Cross-sectional data | ||||||||||||||||

| JNHS | 49,927 | N/A | N/A | 100 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 49,927 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 99.2 | 48,843 | 67.9 | 7.9 | 24.2 |

| JMWHS | 847 | N/A | N/A | 100 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 826 | 9.9 | 58.6 | 31.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HILO | 994 | 24.2 | 0.9 | 29.7 | 0.9 | N/A | 0.1 | 44.2 | 990 | 1.8 | 14.3 | 83.8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SFMWHS | 347 | 46.4 | 27.4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 26.2 | N/A | 342 | 4.1 | 6.4 | 89.5 | 343 | 57.4 | 28.6 | 14.0 |

| DAMES-USA | 293 | 94.2 | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.0 | 2.7 | 293 | 2.4 | 28.7 | 68.9 | 293 | 73.0 | 18.1 | 8.9 |

| DAMES-Lebanon | 298 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 100 | N/A | N/A | 296 | 75.0 | 11.0 | 15.0 | 298 | 87.2 | 12.8 | 0.0 |

| DAMES-Spain | 300 | 95.3 | 3.7 | N/A | N/A | 0.3 | N/A | 0.7 | 300 | 46.3 | 19.0 | 34.7 | 300 | 70.3 | 10.3 | 19.3 |

| DAMES-Morocco | 299 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 100 | N/A | N/A | 299 | 87.3 | 8.7 | 4.0 | 299 | 78.3 | 19.1 | 2.7 |

| Body mass index (%) | Age at menarche (%) | Menopausal status (%) | Vasomotor symptoms h (%) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Study | n | Normal <25 kg/m2 |

Overweight 25–29.9 kg/m2 |

Obese ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

n | ≤ 11 years | 12–13 years | ≥ 14 years | n | Hade surgery | Current MHT use | Current OCP use | Pre-/peri-menopause | Natural menopause | n | Hot flashes | n | Night sweats |

| Overall | 219,351 | 66.9 | 23.2 | 10.0 | 214,759 | 16.9 | 49.8 | 33.2 | 223,775 | 12.6 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 57.2 | 20.0 | 30,309 | 46.1 | 27,085 | 38.3 |

| Longitudinal data | ||||||||||||||||||

| ALSWH | 13,179 | 52.5 | 28.9 | 18.6 | 11,396 | 18.8 | 49.4 | 31.8 | 13,674 | 23.5 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 56.3 | 5.5 | 13,624 | 49.6 | 13,614 | 39.4 |

| HOW | 821 | 43.2 | 32.0 | 24.7 | 508d | 19.5 | 43.3 | 37.2 | 861 | 29.6 | 7.7 | N/A | 14.5 | 48.2 | 851 | 44.8 | 846 | 38.2 |

| MCCS | 24,454 | 41.9 | 36.2 | 21.9 | 24,389 | 16.5 | 45.7 | 37.8 | 24,030 | 20.3 | 4.8 | 1.6 | 29.7 | 43.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| DNC | 28,533 | 71.5 | 22.8 | 5.6 | 28,477 | 7.9 | 43.0 | 49.1 | 28,675 | 13.1 | 12.8 | 2.2 | 37.7 | 34.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| WLH | 47,234 | 72.4 | 21.8 | 5.8 | 48,544 | 12.9 | 54.4 | 32.6 | 48,897 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 12.2 | 74.3 | 2.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| NSHD | 1429 | 60.7 | 25.5 | 13.8 | 1242 | 16.2 | 64.2 | 19.6 | 1492 | 14.9 | 11.3 | 2.9 | 65.0 | 5.8 | 1535 | 37.2 | 1532 | 30.9 |

| NCDS | 4158 | 44.4 | 33.0 | 22.6 | 4227 | 16.5 | 57.7 | 25.7 | 4896 | 17.2 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 48.2 | 21.3 | 4894 | 64.3 | 4895 | 51.9 |

| ELSA | 7485 | 34.4 | 37.6 | 28.0 | 6314 d | 20.9 | 39.5 | 39.6 | 7049 | 19.5 | 11.0 | 1.2 | 16.4 | 51.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| UKWCS | 33,990 | 64.8 | 25.4 | 9.8 | 34,596 | 22.1 | 46.0 | 31.8 | 3,4909 | 19.4 | 13.6 | N/A | 39.2 | 27.8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| WHITEHALL | 3411 | 61.1 | 27.9 | 11.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3268 | 12.2 | 1.7 | 6.2 | 58.9 | 21.0 | 2704 | 35.3 | N/A | N/A |

| SWAN | 3260 | 40.1 | 26.9 | 33.0 | 3267 | 24.2 | 52.7 | 23.1 | 3225 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 100f | N/A | 3285 | 26.7 | 3284 | 29.3 |

| SMWHS | 507 | 55.4 | 25.8 | 18.7 | 507 | 22.9 | 57.8 | 19.3 | 506 | N/Af | 5.9 | 3.0 | 90.3 | 0.8 | 361 | 10.5 | 361 | 8.0 |

| Cross-sectional data | ||||||||||||||||||

| JNHS | 47,831 | 87.2 | 11.0 | 1.8 | 49,175 | 21.0 | 54.1 | 25.0 | 48,968 | 5.7 | 0.2 | N/A | 82.5 | 11.6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| JMWHS | 825 | 85.7 | 13.1 | 1.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 813 | 11.3 | 2.1 | N/A | 31.0 | 55.6 | 830 | 46.5 | 827 | 25.5 |

| HILO | 955 | 46.9 | 29.7 | 23.4 | 972 | 25.4 | 52.8 | 21.8 | 982 | 21.5 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 38.7 | 30.8 | 994 | 32.1 | 994 | 25.2 |

| SFMWHS | 96 | 36.5 | 32.3 | 31.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 343 | 1.7 | N/A | N/A | 97.1 | 1.2 | 339 | 17.1 | 339 | 21.8 |

| DAMES-USA | 293 | 43.7 | 29.0 | 27.3 | 291 | 22.3 | 49.1 | 28.5 | 293 | 16.0 | N/A | N/A | 50.0 | 34.0g | 293 | 56.7 | 292 | 35.6 |

| DAMES-Lebanon | N/Ac | N/A | N/A | N/A | 298 | 21.1 | 42.3 | 36.6 | 297 | 11.0 | N/A | N/A | 55.0 | 34.0g | 271 | 48.0 | N/A | N/A |

| DAMES-Spain | 300 | 59.0 | 33.0 | 8.0 | 297 | 20.9 | 54.9 | 24.2 | 300 | 9.0 | N/A | N/A | 53.0 | 38.0g | 300 | 45.7 | 300 | 34.0 |

| DAMES-Morocco | N/Ac | N/A | N/A | N/A | 259 | 10.0 | 45.6 | 44.4 | 297 | 2.0 | N/A | N/A | 55.0 | 43.0g | 299 | 61.2 | N/A | N/A |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable; MHT, menopause hormone therapy; OCP, oral contraceptive pill.

Education ≤10 years corresponds to less than high school (equivalent to CSE or GCE O level in the UK), 11–12 years to high school (equivalent to GCE A level in the UK), and >12 years to at least some college (including trade, certificate, vocational training, diploma, and university degree).

In the WLH study, marital status was only recorded from mothers’ birth registry hence the data were missing for all women who did not give birth.

Body mass index data were reported as body weight appearance by category only (e.g. normal, overweight, obese), instead of measured or self-reported weight and height.

In the HOW study, age at menarche was only collected from survey 2 in 2006; in the ELSA study, age at menarche was only collected at wave 3 and wave 4 hence the data were missing for those women who lost to follow-up.

Had surgery category included hysterectomy or oophorectomy.

The baseline eligibility criteria for the SWAN study were: at least one menstrual period in the previous three months, without surgical removal of the uterus and/or both ovaries, and without the current use of hormone therapy. The baseline eligibility for the SMWHS study was without surgical removal of uterus or ovaries.

In the DAMES studies, women on MHT use were categorised as post-menopause.

Vasomotor symptoms were asked whether participants had experienced the symptoms in different time periods prior to baseline: in the last 12 months (ALSWH, NSHD, and NCDS), in the past month (DAMES studies), in the last one/two weeks (SFMWHS, SWAN, and HILO), and in the past 24 h/at the moment (HOW, WHITEHALL, SMWHS, and JMWHS).

Regarding reproductive factors, 40–60% of women reported that they had their first period (menarche) between the ages of 12–13 years. The percentage of women with earlier menarche (≤11 years) was around 20%, except for DNC and DAMES-Morocco where this was less than 10%. At baseline most women (57%) were still pre-or peri-menopausal, 20% reported natural menopause (range 0.8–55.6% among studies), 13% had hysterectomy or oophorectomy (range 1.7–29.6%), and the remaining 10% were taking either MHT or OCP. The distribution of vasomotor symptoms also varied considerably among studies, reflecting the range of age and menopausal status among studies. The studies with the oldest baseline age of late 50s (HOW, MCCS, ELSA, and JMWHS) had the highest proportions of naturally menopausal women (range 43.5–55.6%) and high prevalence of vasomotor symptoms (30–50%). Conversely, studies with a younger baseline age of early 40s (WLH, SMWHS, and SFMWHS) had lower proportions of natural menopause ( < 3%) and lower prevalence of vasomotor symptoms (10–20%).

The prevalence of CVD and diabetes at baseline for cross-sectional studies and at the end of the follow-up period for the 12 longitudinal studies are provided in Table 3. Overall, the median age at last follow-up for disease outcome was 56 years (IQR: 48–64 years). The prevalence of CVD and diabetes were higher in longitudinal studies that followed participants into their 60s or 70s of age. The overall prevalence of CVD was 7.2%, but it ranged from 0.9 to 24.6% between studies with the lowest in JNHS (median age 41 years) and the highest in ELSA (median age 65 years). Of the total CVD cases, 2.0% were stroke and 5.8% were heart disease. There was little variation in the prevalence of stroke between studies, except for ELSA, which had more than double the prevalence (5.6%) of other studies. A wider variation was evident in the prevalence of heart disease across studies, which ranged from 0.6 to 22.4%. The overall prevalence of diabetes was 5.1%, with JNHS having the lowest (1.3%) prevalence and SWAN the highest (13.2%).

Table 3.

The prevalence of chronic diseases at the end of study follow-up for the 20 studies.

| Cardiovascular disease | Diabetes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Study | Median age at last follow-up (IQR) | n | Stroke and/or heart disease (%) | n | Stroke (%) | n | Heart diseasesc(%) | n | Type 1 or Type 2 (%) |

| Overall | 56 (48–64) | 218,082 | 7.2 | 217,608 | 2.0 | 217,992 | 5.8 | 223,211 | 5.1 |

| Longitudinal dataa | |||||||||

| ALSWH | 63 (60–65) | 13,714 | 12.3 | 13,714 | 2.9 | 13,713 | 10.7 | 13,714 | 12.0 |

| HOW | 63 (60–66) | 522 | 13.2 | 515 | 2.3 | 521 | 11.5 | 523 | 11.1 |

| MCCS | 64 (57–71) | 24,467 | 10.3 | 24,467 | 2.9 | 24,467 | 8.3 | 24,467 | 7.3 |

| DNC | 64 (50–73)b | 28,640 | 10.9 | 28,592 | 2.9 | 28,632 | 8.5 | 28,554 | 4.8 |

| WLH | 59 (54–64)b | 49,149 | 6.0 | 49,021 | 2.2 | 49,148 | 4.2 | 49,258 | 6.1 |

| NSHD | 64b | 1526 | 13.6 | 1518 | 0.8 | 1503 | 13.2 | 1526 | 6.0 |

| NCDS | 55 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5274 | 5.7 |

| ELSA | 65 (58–75) | 9118 | 24.6 | 9115 | 5.6 | 9118 | 22.4 | 9115 | 9.4 |

| UKWCS | 53 (47–62) | 33,607 | 4.5 | 33,334 | 1.1 | 33,558 | 3.6 | 33,372 | 2.4 |

| WHITEHALL | 61 (56–67) | 3413 | 18.0 | 3413 | 2.2 | 3413 | 16.6 | 3413 | 10.2 |

| SWAN | 54 (52–57) | 3302 | 7.8 | 3300 | 3.1 | 3296 | 5.5 | 3296 | 13.2 |

| SMWHS | 48 (42–55)b | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 508 | 4.1 |

| Cross-sectional dataa | |||||||||

| JNHS | 41 (35–47) | 49,658 | 0.9 | 49,658 | 0.3 | 49,658 | 0.6 | 49,658 | 1.3 |

| JMWHS | N/A (45–60) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HILO | 51 (46–56) | 966 | 6.2 | 961 | 2.2 | 965 | 4.8 | N/A | N/A |

| SFMWHS | 43 (42–45) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 234 | 2.1 |

| DAMES-USA | 50 (48–53) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| DAMES-Lebanon | 50 (48–53) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| DAMES-Spain | 50 (47–53) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| DAMES-Morocco | 49 (46–52) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 299 | 5.4 |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable; IQR, interquartile range.

Longitudinal studies provided the cumulative prevalence of chronic diseases over the study follow-up period. Once women reported they had CVD or diabetes, their disease status carried forward at subsequent surveys. Cross-sectional studies only provided the prevalence of disease at baseline.

DNC, WLH, and SMWHS provided diseases outcome data from survey questionnaires and also from hospital registries (DNC: 1993–2013, WLH: 1991–2010, SMWHS: 1990–2013). NSHD also provided disease outcome data from the latest 2010 survey, when cohort members were aged 64 years.

Heart diseases included general heart disease, heart attack, heart failure and angina.

4. Discussion

With the pooled information from 230,000 mid-aged women across 20 cohort and cross-sectional studies, from ten countries, InterLACE has sufficient scale and heterogeneity to study the health of women in midlife. It provides a unique opportunity for advancing understanding of the relationships between reproductive characteristics and chronic diseases that are shown to have marked sex differences in their aetiology and prevalence. The study has assembled a broad spectrum of prospective data on mid-aged women, including socioeconomic status (education and marital status), lifestyle (BMI, smoking, and physical activities), reproductive factors (menarche, parity, and menopause), and disease outcomes (diabetes and CVD). It comprises a diverse range of race/ethnic groups (Caucasian, Asian, and Blacks) that enables inferences to be drawn regarding minority subgroups that would otherwise be underpowered in individual studies. This heterogeneity is important for detecting relationships that may not be apparent in homogeneous populations and increases the generalizability of the study findings.

The overall distribution of measures in InterLACE data are broadly consistent with that in the published literature, for example, most of the women had their first menstrual period between 12 and 13 years of age [43,44]. Similarly, the overall prevalence of obesity (10% at baseline) and diabetes (5% by final survey) among mid-aged women was comparable with the global prevalence of these conditions in the early 2000s [45,46].

The process of combining individual-level data from multiple cohorts and cross-sectional studies for InterLACE inevitably leads to a number of methodological challenges. The contributing studies varied in their sampling methods, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and modes of survey administration. For instance, women may respond differently to questions about their reproductive health if the survey is completed on-line or via a telephone interview compared with a self-completed paper-based questionnaire, which was the most frequently used data collection method. Retention of participants is an issue for all longitudinal studies. The contributing studies have different levels of sample attrition and missing data due to withdrawal, mortality, and other reasons for non-response at each wave of data collection. The studies also varied greatly in terms of likely representativeness of the sample with respect to the relevant national population; for example sampling from specific professional groups as illustrated by women in the civil service for the Whitehall II study, or women nurses for the DNC and JNHS studies. Variations in the prevalence of CVD across studies already serve to illustrate the effect of differences in the age range of the cohorts of women when they responded to the relevant survey questions. Future analyses of the data from InterLACE will need to identify and adjust for these potential sources of heterogeneity and clustering of information.

5. Conclusion

Despite the challenges, this study profile shows that InterLACE has the potential to build a more detailed understanding of the differential effects of timing, frequency or duration of reproductive characteristics on the risk of key chronic disorders. This will allow for the development of distinct profiles of reproductive characteristics throughout life. Because these profiles are likely to be associated with risk of chronic disease in later life, they have the potential to be developed as the basis for a more tailored approach for preventive health strategies when women discuss reproductive issues with health professionals. Moreover, such health service encounters may present an opportunity for timely and targeted interventions to reduce chronic disease risk [47] that can be enhanced to individual needs through understanding the interactions between reproductive health profiles and modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic conditions. Crucially, InterLACE also enables a detailed review of methodologies currently used in the field of menopausal symptom research. This will result in recommendations for study design, symptom measures, and reporting of results to improve international and cross-cultural comparisons. Standardization of methods will become increasingly important to enhance the value of studies of women’s health in low and middle-income countries and where currently there are manifest gaps in knowledge.

Further information is available on the InterLACE website http://interlace.org.au. The pooled data set is governed by a Collaborative Research Agreement among several institutions. Those interested in collaborating on the project can contact the scientific committee at interlace@uq.edu.au.

Acknowledgments

Funding

InterLACE is funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1027196, APP1000986). G. D. Mishra is supported by the Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT120100812). The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of this manuscript; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

The data on which this research is based were drawn from several global observational studies including: Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH), Healthy Ageing of Women Study (HOW), Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS), Danish Nurse Cohort Study (DNC), Women’s Lifestyle and Health Study (WLH), Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development (1946) (NSHD), National Child Development Study (1958) (NCDS), English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), UK Women’s Cohort Study (UKWCS), Whitehall II study (WHITEHALL), The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), Seat-tle Midlife Women’s Health Study (SMWHS), Japan Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS), Japanese Midlife Women’s Health Study (JMWHS), Hilo Women’s Health Study (HILO), San Francisco Midlife Women’s Health Study (SFMWHS), and The Decision at Menopause Study (DAMES).

The research on which this paper is based was conducted as part of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, the University of Newcastle, Australia, and the University of Queensland, Australia. We are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for funding and to the women who provided the survey data. HOW and JMWHS (also called Australian and Japanese Midlife Women’s Health Study) were supported by Queensland University of Technology Early Career Research Grant, JSPS Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research. MCCS was supported by VicHealth and the Cancer Council, Victoria, Australia. DNC was supported by the National Institute of Public Health, Copenhagen, Denmark. WLH was funded by a grant from the Swedish Research Council (Grant number 521-2011-2955). NSHD and NCDS have core funding from the UK Medical Research Council. ELSA is funded by the National Institute on Aging (Grants 2RO1AG7644 and 2RO1AG017644-01A1) and a consortium of UK government departments. UKWCS was originally funded by the World Cancer Research Fund. The Whitehall II study has been supported by grants from the Medical Research Council. SMWHS was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research, P50-NU02323, P30-NR04001, and R01-NR0414. Baseline survey of the JNHS was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B: 14370133, 18390195) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and by the grants from the Japan Menopause Society. HILO was supported by NIH grant 5 S06 GM08073-26. SFMWHS was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (1 R01 NR04259) at the NIH. The DAMES project was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation Behavioral Science Branch (SBR-9600721), and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging, 5R01 AG17578. Both grants were to Carla Makhlouf Obermeyer, PI.

SWAN has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061; U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH.

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 – present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994–2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA – Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 – present; Robert Neer, PI 1994–1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL – Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 – present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994–2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser –Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles – Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY – Carol Derby, PI 2011 – present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010–2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004–2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry – New Jersey Medical School, Newark – Gerson Weiss, PI 1994–2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD –Winifred Rossi 2012 – present; Sherry Sherman 1994–2012; Marcia Ory 1994–2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD–Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012 – present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001–2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA – Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995–2001.

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair

Chris Gallagher, Former Chair

All studies would like to thank the participants for volunteering their time to be involved in the respective studies. The findings and views in this paper are not those of the original studies or their respective funding agencies.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

Each study in the InterLACE consortium has been undertaken with ethical approval from the relevant authorities and with the informed consent of participants.

Contributors

GDM conceived the study design and contributed to interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript.

H-FC, NP and LJ harmonized the data and performed statistical analysis.

AJD and DA contributed to interpretation of the data.

NEA, SLC, EBG, DB, LLS, EB, JEC, VJB, DCG, GGG, FB, AG, KH, JSL, HM, DK, RC, RH, CMO, KAL, MKS, TY, NFW, ESM, MH, PD, SS, H-OA and EW provided study data.

All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review

This article has undergone peer review.

References

- 1.Huxley R, Barzi F, Woodward M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2006;332:73–78. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38678.389583.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thurston RC, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Everson-Rose SA, Hess R, Matthews KA. Hot flashes and subclinical cardiovascular disease: findings from the study of women’s health across the nation heart study. Circulation. 2008;118:1234–1240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wellons M, Ouyang P, Schreiner PJ, Herrington DM, Vaidya D. Early menopause predicts future coronary heart disease and stroke: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Menopause. 2012;19:1081–1087. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182517bd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wernli KJ, Ray RM, Gao DL, De Roos AJ, Checkoway H, Thomas DB. Menstrual and reproductive factors in relation to risk of endometrial cancer in Chinese women. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:949–955. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janghorbani M, Mansourian M, Hosseini E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of age at menarche and risk of type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51:519–528. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0579-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charalampopoulos D, McLoughlin A, Elks CE, Ong KK. Age at menarche and risks of all-cause and cardiovascular death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:29–40. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1141–1151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70425-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra GD, Cooper R, Tom SE, Kuh D. Early life circumstances and their impact on menarche and menopause. Womens Health. 2009;5:175–190. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chevalley T, Bonjour JP, Ferrari S, Rizzoli R. Deleterious effect of late menarche on distal tibia microstructure in healthy 20-year-old and premenopausal middle-aged women. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:144–152. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuh D, Muthuri S, Moore A, Cole TJ, Adams JE, Cooper C, et al. Pubertal timing and bone phenotype in early old age: findings from a British birth cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw131. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brand JS, van der Schouw YT, Onland-Moret NC, Sharp SJ, Ong KK, Khaw KT, et al. Age at menopause, reproductive life span, and type 2 diabetes risk: results from the EPIC-InterAct study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1012–1019. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atsma F, Bartelink ML, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. Postmenopausal status and early menopause as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Menopause. 2006;13:265–279. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000218683.97338.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mesch VR, Boero LE, Siseles NO, Royer M, Prada M, Sayegh F, et al. Metabolic syndrome throughout the menopausal transition: influence of age and menopausal status. Climacteric. 2006;9:40–48. doi: 10.1080/13697130500487331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuh D, Langenberg C, Hardy R, Kok H, Cooper R, Butterworth S, et al. Cardiovascular risk at age 53 years in relation to the menopause transition and use of hormone replacement therapy: a prospective British birth cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112:476–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardy R, Kuh D, Wadsworth M. Smoking body mass index, socioeconomic status and the menopausal transition in a British national cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:845–851. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melby MK, Anderson D, Sievert LL, Obermeyer CM. Methods used in cross-cultural comparisons of vasomotor symptoms and their determinants. Maturitas. 2011;70:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, Bromberger J, Greendale GA, Powell L, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra GD, Anderson D, Schoenaker DA, Adami HO, Avis NE, Brown D, et al. InterLACE: a new international collaboration for a life course approach to women’s reproductive health and chronic disease events. Maturitas. 2013;74:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra GD, Cooper R, Kuh D. A life course approach to reproductive health: theory and methods. Maturitas. 2010;65:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rich-Edwards JW. Reproductive health as a sentinel of chronic disease in women. Womens Health. 2009;5:101–105. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephenson J, Kuh D, Shawe J, Lawlor D, Sattar NA, Rich-Edwards J, et al. Scientific Impact Paper No. 27. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2011. Why Should We Consider a Life Course Approach to Women’s Health Care? [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobson AJ, Hockey R, Brown WJ, Byles JE, Loxton DJ, McLaughlin D, et al. Cohort profile update: Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;4:1547a–1547f. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson D, Yoshizawa T, Gollschewski S, Atogami F, Courtney M. Menopause in Australia and Japan: effects of country of residence on menopausal status and menopausal symptoms. Climacteric. 2004;7:165–174. doi: 10.1080/13697130410001713760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giles GG, English DR. The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hundrup YA, Simonsen MK, Jørgensen T, Obel EB. Cohort profile: the Danish nurse cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1241–1247. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roswall N, Sandin S, Adami HO, Weiderpass E. Cohort profile: the Swedish women’s lifestyle and health cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv089. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadsworth M, Kuh D, Richards M, Hardy R. Cohort profile: the 1946 national birth cohort (MRC national survey of health and development) Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:49–54. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Power C, Elliott J. Cohort profile: 1958 British birth cohort (national child development study) Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:34–41. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J. Cohort profile: the English longitudinal study of ageing. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1640–1648. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cade JE, Burley VJ, Alwan NA, Hutchinson J, Hancock N, Morris MA, et al. Cohort profile: the UK women’s cohort study (UKWCS) Int J Epidemiol. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv173. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmot M, Brunner E. Cohort profile: the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:251–256. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sowers M, Crawford SL, Sternfeld B, Morganstein D, Gold EB, Greendale GA, et al. SWAN: a Multi-Center, Multiethnic Community-Based Cohort Study of Women and The Menopausal Transition. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell ES, Woods NF. Cognitive symptoms during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause. Climacteric. 2011;14:252–261. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.516848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi K, Mizunuma H, Fujita T, Suzuki S, Imazeki S, Katanoda K, et al. Design of the Japan Nurses’ Health Study: a prospective occupational cohort study of women’s health in Japan. Ind Health. 2007;45:679–686. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sievert LL, Morrison L, Brown DE, Reza AM. Vasomotor symptoms among Japanese-American and European-American women living in Hilo, Hawaii. Menopause. 2007;14:261–269. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000233496.13088.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilliss CL, Lee KA, Gutierrez Y, Taylor D, Beyene Y, Neuhaus J, et al. Recruitment and retention of healthy minority women into community-based longitudinal research. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:77–85. doi: 10.1089/152460901750067142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obermeyer CM, Reynolds RF, Price K, Abraham A. Therapeutic decisions for menopause: results of the DAMES project in central Massachusetts. Menopause. 2004;11:456–465. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000109318.11228.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obermeyer CM, Ghorayeb F, Reynolds R. Symptom reporting around the menopause in Beirut, Lebanon. Maturitas. 1999;33:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Obermeyer CM, Reher D, Alcala LC, Price K. The menopause in Spain: results of the DAMES (Decisions At MEnopause) study. Maturitas. 2005;52:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obermeyer CM, Schulein M, Hajji N, Azelmat M. Menopause in Morocco: symptomatology and medical management. Maturitas. 2002;41:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mateos P. Ethnicity, language and populations. In: Mateos P, editor. Names, Ethnicity and Populations. Springer; Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: 2014. pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nichols HB, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Egan KM, Willett WC, et al. From menarche to menopause: trends among US women born from 1912 to 1969. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:1003–1011. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wyshak G, Frisch RE. Evidence for a secular trend in age of menarche. New Engl J Med. 1982;306:1033–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204293061707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diab Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1431–1437. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases: Attaining The Nine Global Noncommunicable Diseases Targets; A Shared Responsibility. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]