Abstract

The United States healthcare system is rapidly moving toward rewarding value. Recent legislation, such as the Affordable Care Act and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), solidified the role of value-based payment in Medicare. Many private insurers are following Medicare’s lead. Much of the policy attention has been on programs such as accountable care organizations and bundled payments; yet, value-based purchasing (VBP) or pay-for-performance, defined as providers being paid fee-for-service with payment adjustments up or down based on value metrics, remains a core element of value payment in MACRA and will likely remain so for the foreseeable future. This review article summarizes the current state of VBP programs and provides analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for the future. Multiple inpatient and outpatient VBP programs have been implemented and evaluated, with the impact of those programs being marginal. Opportunities to enhance the performance of VBP programs include improving the quality measurement science, strengthening both the size and design of incentives, reducing health disparities, establishing broad outcome measurement, choosing appropriate comparison targets, and determining the optimal role of VBP relative to alternative payment models. VBP programs will play a significant role in healthcare delivery for years to come, and they serve as an opportunity for providers to build the infrastructure needed for value-oriented care.

Keywords: outcomes research, cost, value-based purchasing

Introduction

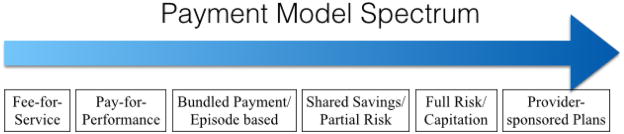

U.S. healthcare has reoriented towards quality and value, incorporating both the health outcomes and the resources allocated to achieve those outcomes. The need for value is clear. With healthcare consuming almost one-fifth of the U.S. economy, the burden of healthcare expenditures continues to crowd out funds for other society essentials such as education, infrastructure, and social security programs.1 Despite the fact that the U.S. ranks the highest in the world on healthcare spending, the U.S. ranks the lowest on health performance indicators among eleven comparable nations.2, 3 While provider organizations, insurance companies, and government payors have attempted to improve quality and lower cost since the 1990’s, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) launched unprecedented reforms to improve healthcare value. A wide spectrum of payment models have been introduced that balance financial rewards and risks based on provider performance on specific measures, such as clinical quality, patient experience, and cost (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A variety of payment models aim to improve healthcare value, with varying degrees of accountability and financial risk. This review paper discusses pay-for-performance, often known as value-based purchasing (VBP). VBP is the first step from fee-for-service on the spectrum toward more comprehensive and higher financial risk programs.

The shift towards value-based payment has only accelerated: in January 2015 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced their intent to tie 85% of all traditional Medicare payments to quality or value by 2016 and 90% of payments by 2018.4 The April 2015 passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) repealed the longstanding, unsuccessful Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula for Medicare and widely adopted alternative payment models, thus demonstrating the bipartisan and far-reaching commitment to valued-based payment solutions.5 With this growing traction, it is critical for clinicians to better understand the programmatic structure, the data about the strengths and weaknesses, and the prospects for the future of value-based purchasing.

Cardiovascular care has been and continues to be at the forefront of these changes. Acute myocardial infarction and heart failure have been the focus of policy efforts to improve quality and value for three main reasons. First, cardiovascular disease and its associated risk factors impact millions of Americans with an ensuing large morbidity and mortality burden. Second, cardiovascular disease is costly both in the direct healthcare costs and the indirect costs of the illnesses on society.6 Lastly, the cardiovascular community has been a leader in establishing an evidence base of randomized-controlled trials that have led to rigorous guidelines supporting clinical care. These evidence-based guidelines naturally lend themselves to the establishment of quality measures by which performance on delivering guideline-based care can be evaluated. Thus, cardiovascular disease has been integral to quality measurement and incentive programs from their very inception and will continue to be. Cardiologists and other cardiovascular disease providers must understand these programs in order to succeed in these programs and advocate for program designs that are fair, rational, and best serve the needs of providers and, most importantly, patients.

Concept of Value-Based Purchasing

Traditionally the U.S. health care system has relied on fee-for-service compensation, where reimbursements were provided for each service provided, regardless of the resulting patient outcomes or costs. The paradigm has shifted to paying for value, defined as the health outcomes or quality achieved in relation to the costs of the care provided.7 Value can be increased by improving outcomes and quality, reducing costs, or both.

While value-based purchasing (VBP) can refer to a wide variety of payment strategies that link provider performance and reimbursement, this paper will focus on VBP programs where providers are paid fee-for-service with payment adjustments up or down based on value metrics, a structure also known as pay-for-performance. This paper will not address payment models which have been covered by other pieces in this series such as Patel et al on accountable care organization (ACO) and Shih et al on bundled payments.8, 9 This pay-for-performance VBP mechanism serves as an introductory model that allows providers to gain experience at relatively low risk with the essentials of alternative payment models: quality metrics, performance improvement, and payment incentives and risks. This could be the critical transitional step to allow organizations to adopt more advanced alternative payment models involving greater potential financial risk and benefit, such as shared savings models for ACOs.

To better conceptualize, develop, implement, and evaluate VBP programs, several frameworks have been created to outline the primary components and interacting factors.10, 11, 12, 13 The design and evaluation of VBP programs depends on three main influences: the external environment, provider characteristics, and program features. (Figure 2) The external environment includes regulatory changes, payment policies, patient preferences, and other quality improvement initiatives which can either promote or thwart the potential success of VBP programs. Provider characteristics include structure of the healthcare system, organizational culture, available resources and capabilities (especially in information technology), and patient population served. Program features include defining the targeted patient population, the program goals, measures, financial incentive, and risk structure. Specific program structure considerations include the level at which the data is analyzed and incentives are provided - is it individual physicians, physician groups, or the entire organization. Understanding the multiple factors influencing VBP programs is essential to designing, evaluating, and importantly succeeding in these programs. Moreover, minute details of the measures, formulas for calculating performance, and rules for defining rewards and penalties can have substantial impact on who wins and who loses, and on unintended consequences such as potentially worsening healthcare disparities.14, 15

Figure 2.

The design and evaluation of value based purchasing programs depend on the external environment, provider characteristics and program features. This figure provides examples in each of those components.

Major Value-Based Purchase Programs

There are numerous VBP pay-for-performance programs both internationally and within the U.S., encompassing a wide variety of healthcare delivery settings, and implemented by both commercial insurance companies and by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This paper will detail several key historical and current VBP programs and specific evaluation studies, ranging from the outpatient to the inpatient settings. Cardiovascular care has been a foundational aspect of many programs, especially in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction as well as the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and heart failure (specific measures are detailed in Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardiovascular disease – selected specific measures.

IHA Measures

|

HEDIS Measures

|

PQRS, Value Based Modifier

|

Premier HQID

|

Hospital Value Based Purchasing Measures

|

ACO Measures

|

ACEI = Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor; ARB = Angiotensin Receptor Blocker; RAS = Renin Angiotensin System; LVSD = Left Ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVEF <40%)

Outpatient VBP Programs

California Integrated Healthcare Association (IHA)

One of the first and largest private, non-governmental multi-payer VBP program is the California IHA program. The IHA program assesses quality in the four domains of clinical quality, meaningful use, patient experience and appropriate resource use, including cardiovascular health related metrics: process measures on secondary prevention such as blood pressure control and statin therapy.16 These quality measures translate into three forms of incentives: financial, public reporting, and public recognition. From 2004 to 2013, the IHA awarded a total of nearly $500 million in bonus payments; however, to put these rewards in context, the total incentive payments in 2007 was $52 million, which represented only about 2% of total base compensation.17 The public reporting was an online quality report card on overall and individual measure performances and five public recognition awards were developed. The concept is that the financial, public reporting, and public recognition incentives complement each other to drive improvement.

A 2010 IHA white paper report showed that although physician organizations improved in all measurement areas, the performance range was wide. The average state performance was below 75th percentile on national benchmarks for Health Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures while the top quartile of physician groups scored comparable to the 90th percentile. State performance improved an average of 3% annually in overall clinical quality, with improvements in individual measures ranging from 5.1% to 12.4%. Results showed physician groups in the lowest performance quartile had greater absolute improvement than those that started in the highest quartile, but the resulting variation decrease was minimal due to the small size of groups in the lowest quartile. There was marginal improvement in patient experience, with regional variation in a pattern similar to clinical quality regional variation. 18

State Medicaid Programs

The Commonwealth Fund surveyed state Medicaid programs to determine the prevalence of VBP programs and found that, as of 2006, more than half of all state Medicaid programs had at least one existing VBP program and more than 70% had plans for new programs.19 The most common Medicaid VBP programs were managed care organizations that incorporated incentives based on HEDIS measures, with the majority providing rewards for achieving an attainment threshold. Since children represented half of all Medicaid beneficiaries, most programs focused on addressing the populations of children, adolescents, and women. Given the individualized nature of state Medicaid programs, there is anecdotal, qualitative evidence that these VBP programs are improving quality of care but no large quantitative study analyzing the success of these VBP programs exists.

Medicare Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and Value Based Modifier

Initially called the Physician Voluntary Reporting Program (PVRP) when enacted in 2006, it began as a mere method of promoting reporting requirements by rewarding a one-time lump sum to physicians who sufficiently reported on at least three quality measures. 20 The program changed in subsequent years, becoming the pay-for-reporting program Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI), with changes to the number of measures, the reporting mechanisms, and potential bonus. While the physician reporting began as pay-for-reporting, the program evolved under the ACA to the pay-for-performance Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), with penalties starting in 2015 for not reporting data, and broadening to performance-based penalties and bonuses in the Value-Base Payment Modifier (Value Modifier).21

Cardiovascular measures include appropriate coronary artery disease and heart failure medications, cardiac rehabilitation referrals, as well as control of blood pressure and cholesterol. With most cardiovascular disease measures being based on clinical practice guidelines, a recent difficulty has been how to adapt the PQRS measures for changes in the guidelines. For example, the PQRS program measures included an LDL-C target of less than 100 mg/dL for patients with ischemic vascular disease at the time when the 2013 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines were released removing recommendations for specific LDL-C targets.22 Given the inevitable delay between the publication of evidence-based guidelines and those guidelines being translated into quality measures, a discrepancy existed for some time between the guidelines and the quality measures. Subsequently, the quality measures have been adjusted to reflect the updated clinical guidelines. This example is emblematic of the ongoing challenge of how to keep quality process of care measurement up to date with changing clinical standards of care.

PQRS lays the foundation for the ACA’s Value Modifier program, which mandates payment adjustments based on risk-adjusted quality and cost metrics to Medicare physician payments. 21 These programs will remain effective until 2018, at which point the system will be replaced with the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) created in MACRA, which combines several federal quality programs. MIPS is a fee-for-service based VBP program beginning in 2019 with payment linked to composite score on quality, resource use, clinical improvement, and the use of electronic health records. For providers, substantial amounts of Medicare payments will be in play, with positive or negative adjustments up to 4% in 2019 and increasing over time to up to 9% in 2022.5 Exceptional performers may qualify for an additional 10% positive adjustment annually. The overall program will be budget neutral, so providers receiving bonuses will be offset by providers facing penalties. Under MACRA, physician organizations that participate in alternative payment models (APMs), such as ACOs, with more than minimal financial risk at stake will be exempt from MIPS. At the time of writing this article, the MACRA rule has not yet been finalized but will contain key details about the expectations for MIPS and APM participation. Cardiovascular disease is likely to play a large role in the measures available within MIPS and by which APMs will be evaluated. Moreover, cardiologists will need to make important decisions about whether they participate in MIPS, or participate in an APM that involves the potential for financial losses as well as bonuses. For cardiologists practicing in large organizations, the opportunity exists to provide informed input to their organizations on which path to choose. For independent and small-group cardiologists, this decision of participating in MIPS or joining a qualified APM will be critical as the implications can be broad for both Medicare participation and more general practice affiliations.

Hospital VBP Programs

Medicare Premier Hospital Quality Inventive Demonstration (Premier HQID)

The Premier HQID was a six-year P4P demonstration by CMS from 2003 to 2009 for three medical conditions (acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia) and two surgical procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting and total hip/knee replacement). Premier HQID hospitals could receive either a one to two percent bonus or, starting in 2006, penalty adjustments, based on performance on 33 measures.23 Initially, hospitals were eligible if they achieved the top 20th percentile on metrics, but, in the fourth year, the program introduced bonuses to hospitals with substantial improvements in performance. One of the most widely studied program, evidence is mixed on the effectiveness of HQID. Detailed below, some studies showed it improved quality measures, others showed no effect on outcomes such as mortality, and others showed a temporary effect on quality.

Lindenauer and colleagues sought to determine the added effect of pay-for-performance to public reporting. Adjusting for baseline performance and characteristics, a range of 2.6% to 4.1% improvement over the study period was attributed to pay-for-performance. 24 This suggested that public reporting itself provided a strong incentive for quality improvement, though financial incentives can modestly facilitate performance improvement. Interestingly, multivariable analysis results showed hospitals with the lowest baseline performance had the largest improvements in heart failure composite measures. Although this was not observed in measures for acute myocardial infarction or pneumonia, it raises the issue of whether greater bonuses should be awarded to higher absolute levels of performance metrics or improvement in those metrics.

To address questions about how VBP affected processes of care in the context of other quality improvement initiatives, Glickman and colleagues analyzed data for acute non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients enrolled in the national CRUSADE initiative No significant difference was found in the rate of quality composite score improvement or hospital mortality between HQID and control hospitals. Only two individual incentivized measures (aspirin at discharge and smoking cessation) and one individual non-incentivized measure (lipid-lowering medication at discharge) had slightly higher rates of improvement. 25

Noting that prior studies were mainly on process measures and not outcome measures, Ryan evaluated patient mortality, cost, and outlier classification from over 6.7 million patients from 3,570 hospitals with principal diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, or CABG procedures across four years. Controlling for baseline differences, confounders, and time variants, the analysis showed HQID had no significant effect on risk-adjusted 30-day mortality or on cost growth for the studied diagnoses. 26 To evaluate a change in HQID incentive design to award for improvements, Ryan and colleagues reevaluated relative quality improvement of HQID hospitals to matched samples over a five-year period. While the initial incentive structure led to better improvement rates in the HQID hospitals, the incentivizing of improvement on top of attainment failed to create higher performance. Of note, the incentive structure provided the strongest incentive to hospitals just above the median instead of the lowest performers. 27

While these earlier studies suggested HQID had a small early effect on measures of quality, Werner et al specifically studied whether the effect was sustained and what programmatic, provider, or external factors may have contributed to the program’s success. Comparing Premier HQID hospitals to matched control hospitals, they found a significant initial difference in performance improvement in HQID hospitals compared to controls. However, this effect difference decreased after three years and was no longer statistically different after five years. Subgroup analysis showed that HQID hospitals eligible for larger incentives had larger improvements than control hospitals as compared to the HQID hospitals eligible for smaller incentives. Further analysis also showed that larger improvements were seen in HQID hospitals in less competitive markets and in better financial health. 28 This suggests the design of future VBP programs may need to incorporate larger incentives, more frequent feedback, and greater focus on measurement of the individual clinician. The results also suggest that hospitals in poorer financial health may need greater up-front resources to invest in quality improvement initiatives.

Though the aforementioned studies showed no early effects on mortality, Jha and colleagues studied the longer-term effects on mortality by comparing HQID hospitals to control hospitals in public reporting only. Multivariate regression analysis showed that 30-day risk adjusted mortality rates for the five specified conditions were similar at baseline, with similar rates of decline and no significant difference by the end of the six year study period. There was also no difference found when considering factors such as potential financial incentive, institutional financial health, and market competitiveness.29

State-wide, All-payer Inclusive System

Since 1977 Maryland has had a prospective hospital payment system with specific payments for all inpatient and outpatient services for all public and private payers. Two VBP programs were implemented in Maryland – the 2008 Quality-Based Reimbursement Program, which provides financial rewards and penalties based on processes measures, and the 2009 Maryland Hospital-Acquired Conditions Program, which rewards and penalizes based on a hospital’s risk-adjusted rate of preventable complications or hospital-acquired conditions. Calikoglu and colleagues assessed the Maryland VBP programs by studying the state average and hospital variation in performance rates over four years. While the study results are limited by lacking a robust control group, process measures improved and hospital acquired conditions decreased by over 15% over two years, or an estimated cost savings of $110.9 million.30 This study suggested some VBP program success when all payers have aligned value based incentives and the potential of a statewide value system.

Medicare Hospital VBP Program (HVBP)

Implemented as part of the ACA, HVBP built on Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program (IQR) pay-for-reporting program for hospitals that started in 2003.31 Beginning in 2012, HVBP uses IQR’s infrastructure to introduce Medicare payment adjustments for acute inpatient services. The program creates an incentive payment fund by reducing inpatient Medicare payments by a percentage that increases over time, then distributes that fund to hospitals by applying a value-based adjustment factor that is determined by the hospital’s Total Performance Score. The Total Performance Score initially consisted of two domains of clinical processes of care and a survey in patient experience. In later years the program evolved their measures, standards, weighting, and structure such as including additional domains in outcomes, safety, and efficiency. 32, 33, 34 Outcome measures include mortality for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. Performance is scored based both on attaining a certain achievement level and on improvement compared to each hospital’s baseline and benchmark.

In 2016, the HVBP program increased to representing 1.75% of all Medicare payments to hospitals. In practical application, hospitals will all have 1.75% of all payments withheld, that they can then earn back depending on their Total Performance Score. Some hospitals will earn less than the 1.75% back and have a “penalty,” and some hospitals will earn more than the 1.75% back and have a “bonus.” In 2016, about half of hospitals will see a minimal change in the Medicare payments, with the overall adjustment being between −0.4% and +0.4%. The worst performing hospital will earn back none of the 1.75% withhold, and the highest performing hospital will have a net increase of approximately 1.25%.35 While long terms studies have not yet been completed, an evaluation of the first year of HVBP showed no improvement in clinical process or patient experience among hospitals exposed to the program. 36 Additional studies are certain with grants having already been awarded for this purpose.

International VBP Programs

The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, in partnership with the World Health Organization, published a report on alternative payment models in multiple Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.37 VBP programs exist in primary care, specialist, and hospital categories, with targeted performance measures often overlapping such as in clinical quality, priority services such as immunizations and cancer screenings, and efficiency. Interestingly, other performance domains not commonly seen in the U.S. programs include improving equity or reducing health disparities, though questions exist about whether VBP approaches effectively reduce disparities.38 While most VBP programs are rewarded or penalized based on either attainment, improvement, or relative ranking, Turkey has an “all or nothing” approach where providers avoid a penalty only if all members reach target performance. The review found that the typical incentive was less than 5% of total provider income, with the exception of the U.K. and Turkey programs where general practitioner practices had the potential to increase compensation by almost 25% and 20% respectively. The evaluation of 12 international case studies showed mixed results. Some programs improved rates of preventative services for some conditions and some programs had improvements in chronic disease management. Generally there were no significant impacts on health outcome measures. In programs that achieved broad significant improvements in processes of care, such as Germany and Estonia, there were also reported gains in efficiency and cost savings. Interestingly, cost savings and increased efficiency were not evident in programs with cost reduction incentives, such as targeting brand medications to be replaced with generics.37

While the 2004 U.K chronic disease management pay for performance program that could increase family practitioners’ income by 25% (or $40,200) was among those that had mixed results, the National Health Service implemented the Advancing Quality program in 2008 focusing on hospital payments which showed significant improvements in mortality outcomes.39 Analysis of early results showed risk-adjusted mortality for all conditions decreased and the VBP was associated with a 1.3% reduction in combined mortality. 40 However, this short-term success in first 18 months of the program was not sustained in a longer term analysis of the next 24 months. While both participating and control hospitals lowered mortality rates, the initial benefit of program participation disappeared over time and control hospitals had similar performance to incentivized hospitals.41

Overall Analysis of Value-Based Purchasing Approach

VBP programs have been implemented widely, and their impact has been marginal thus far. The challenge of determining the effectiveness of VBP programs is not only complicated by how one might define success, but also the external factors of simultaneous quality improvement programs such as public reporting. Moreover, the effectiveness of VBP programs stems not only from the process of implementation, but also from specifics of program design and incentive structure. VBP programs essentially remain fee-for-service structures of payment, sustaining all the negative incentives of that system.

In 2014, Damberg and colleagues with RAND were commissioned by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to evaluate available literature on VBP models including pay for performance, accountable care organizations, and bundled payments. Fifty studies of 1,891 articles screened on pay for performance programs were reviewed and ranked by study method quality (good, fair, poor) and strength of evidence reflecting a true effect (high, moderate, low, insufficient). Results were mixed. Thirty-nine studies focused on physicians or physician groups, with 7 of the studies determined to be good quality and 15 of the studies found to be of fair quality. There were modestly positive results of incentives improving treatment, screening, and prevention measures. Eleven studies focused on hospitals, mainly on the CMS HQID program, with six studies of good quality and showing modestly positive results. 42

Future Directions for VBP Programs

The overall effectiveness of VBP programs has been marginal thus far. While many studies have examined VBP programs and sought to understand what works and why, the answers still elude us. Several potential reasons exist for VBP’s meager impacts. First, the financial incentives may be inadequate to drive change. Second, the quality measurement systems may be overly complex such that providers are confused as to which measures are most closely linked to the incentives. Third, the delay in time between measure performance and incentives decouples the two events such that providers do not closely connect cause and effect. Fourth, incentives are often rolled into standard Medicare payments as a percentage adjustment, rather than being called out as a separate payment to highlight the incentive. Lastly, the multiple Medicare programs and commercial payor programs collectively create a confounding environment for providers who become uncertain as to what interventions to work on and which incentives link to which performance. At least on the Medicare programs, this aspect should improve with MACRA as multiple programs are being combined into MIPS. Future program designs that more closely adhere to behavioral economic principles may more effectively drive the intended performance. In addition, some specific programmatic elements are worth considering.

Measurements

Quality is a complex concept with aspects in infrastructure, clinical processes, intermediate outcomes, and true outcomes. As payments are increasingly tied to measurements, there has been debate whether the current set of measures actually correlate with true outcomes that are clinically significant and that are meaningful for patients. While some studies have shown that process measures did modestly correlate with risk-adjusted mortality rates, strong data to support a correlation between process measures and outcomes is lacking. 43 Outcome measures are the ultimate goal in evaluating performance, though outcomes must be risk adjusted and questions exist about how fully the risk adjustment models account for differences in medical risk. An even more challenging question is whether to and how to adjust for socioeconomic factors.44 The outcomes that are calculable from claims data also represent a small set of the true outcomes of clinical interest. Extant measures are limited by the reliance of extractable data from claims. There has been an evolving transition to outcome-based measures, though more development is needed in both disease-specific and overall population-level health measures. An additional consideration is to design VBP programs stratifying measures with different weights based on their relative cost effectiveness, clinical benefit, and value. This will require greater health economics research in cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analysis of interventions that may be high value yet high cost. The science of quality measurement will need to quickly and substantially improve to meet the expanding need to assess quality performance in VBP programs.

Incentive structure

There is much that is not known about how to best design incentive structures, including the size of the incentive, the recipient (individual versus organization), how reward eligibility is determined (attainment, improvement), frequency of information feedback or incentive, and inclusion of nonfinancial incentives (recognition). With regards to incentive size, studies have showed varied results where programs with incentives of as little as $2 per patient incentive have been effective and others with $10,000 per practice have not.28 Little to no research has been done regarding the impact of more frequent performance feedback. Studies in behavioral economics have shown that people tend to discount future losses at lower rates than gains and larger outcomes more than smaller outcomes, suggesting that a high incentive frequency may be more effective, especially for the risk-adverse.45 Behavioral economics also demonstrates loss and risk aversion: people have stronger preferences to avoid losses compared to acquiring gains, even when the objective value is equivalent.46 In terms of incentive recipients, one systematic review showed that targeting incentives directly to providers versus the organization had greater positive results.47 Evaluations of existing and planned VBP programs may resolve questions of the optimal incentive structures for various settings; however, such answers will require operational programs to be designed with rigorous evaluations in mind. In addition, incentive structures are often constrained by legislation (as in the case of budget neutrality for the VBP programs), potentially limiting innovative incentive designs (such as frequent incentive payments). Future considerations of incentive structure creation include categorizing performance such as meeting prior performance, improving from prior performance, meeting a minimum threshold standard, and being a regional best performer.

Health Disparities

It has been suggested that VBP programs could exacerbate health disparities by penalizing organizations with large disadvantaged populations already less likely to receive recommended care due to factors including lower health literacy, resource constraints of both patients and facilities, and cultural norms. This concept was supported by Chien and colleagues who geocoded quality data of 12,000 practices in the California IHA program, and found a significant association between higher socio-economic areas and higher performance scores, despite outliers.48 Including patient satisfaction as a major performance indicator may also be disadvantageous to safety net hospitals. In a study defining safety net hospitals into quartiles by proportion of patients receiving Supplemental Security Income or Medicaid, there was a significant difference in patient satisfaction scores.49 However, Ross and colleagues, in a study of Medicare fee-for-service, showed minimal differences in mortality and readmission rates between safety net and non-safety net hospitals.50 Clearly the potential for unintended consequences, such as the exacerbation of healthcare disparities, requires consideration in program design and close ongoing monitoring and evaluation.51, 52

Unmeasured Priority Areas

There is concern about “teaching to the test” where VBP programs may cause providers to focus on incentivized areas of care, and possibly ignore non-incentivized but still essential and valued aspects of care.53 While VBP programs strive to employ a wide range of measures covering multiple clinical areas, unmeasured areas will certainly exist and the possibility for inattention is real. The shift toward incentivizing broad outcomes measures may mitigate some of this risk.

Comparison targets

There is extensive geographic variation in quality and costs, often previously attributed to practice variations and cost of living adjustments, but recent research has also shown there is significant price charge variations even in one geographic region and no correlation between federal Medicare and private insurance prices.54 Hospital comparison targets are often determined nationally. For ACOs, some have recommended using regional financial benchmarks and this element may be incorporated into the Medicare Shared Savings Program.55, 56 Perhaps similar consideration of regional financial benchmarks should be included in VBP programs.

Interaction with Alternative Payment Models

While it is clear that nearly all Medicare payments will be linked to value and likely many private insurance payments, it is less clear how, or what mix of programs will exist and what programs will dominate. Medicare has signaled that it favors either episode-based payments, such as bundled payments, or global payment models, exemplified by accountable care organizations.5 However, bundled payments may not be appropriate for all conditions or all procedures, and not all providers will have the scale or capabilities to participate in an accountable care organization. Thus, it is likely that a variety of alternative payment models will exist in the years to come, with bundled payments, accountable care organizations, and still fee-for-service for some episodes of care. The fee-for-service that continues to exist will have some incentives linked to payment, likely in forms similar to current and recent VBP programs.

Conclusions

The strength of evidence on the effectiveness of pay for performance VBP programs on improving health delivery and patient outcomes is mixed and modest. Many studies were over a short time frame; while a longer study period may allow better observation of long-term outcomes, it also makes the study more vulnerable to confounding by other factors. As healthcare payment models increasingly move towards risk and accountability, there needs to be greater understanding of the individual design levers in creating a VBP program as well as responsiveness to the incentives of individual providers and provider organizations. With recent legislation expanding VBP for organizations not in qualifying APMs, these programs provide opportunities for providers of cardiovascular care to build infrastructure for value-oriented care.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: William B. Borden – salary as the Director of Healthcare Delivery Transformation at the George Washington University Medical Faculty Associates. Jason H. Wasfy – salary as assistant medical director of the Massachusetts General Physicians Organization.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 27, 2015];NHE-Fact-Sheet. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet.html. Published July 28, 2015.

- 2.Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, 2014 Update: How the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally. [Accessed August 27, 2015];Commonw Fund. 2014 Jun; http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/jun/mirror-mirror.

- 3.Squires D. The U.S. Health System in Perspective: A Comparison of Twelve Industrialized Nations. [Accessed August 27, 2015];Commonw Fund. 2011 Jul; http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2011/jul/us-health-system-in-perspective. [PubMed]

- 4.Burwell SM. Setting Value-Based Payment Goals — HHS Efforts to Improve U.S. Health Care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:897–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed October 15, 2015];MACRA: MIPS & APMs. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Published October 15, 2015.

- 6.Ojeifo O, Berkowitz SA. Cardiology and Accountable Care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:213–217. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter ME. What Is Value in Health Care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2477–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shih T, Chen LM, Nallamothu BK. Will Bundled Payments Change Health Care?: Examining the Evidence Thus Far in Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2015;131:2151–2158. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel KK, Cigarroa JE, Nadel J, Cohen DJ, Stecker EC. Accountable Care Organizations: Ensuring Focus on Cardiovascular Health. Circulation. 2015;132:603–610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudley RA, Frolich A, Robinowitz DL, Talavera JA, Broadhead P, Luft HS. Strategies To Support Quality-Based Purchasing: A Review of the Evidence. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004. [Accessed August 27, 2015]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43997/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHugh M, Joshi M. Improving Evaluations of Value-Based Purchasing Programs. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(5 Pt 2):1559–1569. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher ES, Shortell SM, Kreindler SA, Van Citters AD, Larson BK. A framework for evaluating the formation, implementation, and performance of accountable care organizations. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2012;31:2368–2378. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theory and Reality of Value-Based Purchasing: Lessons from the Pioneer. AHRQ; [Accessed August 27, 2015]. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/meyer/index.html. Published November 1, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blustein J, Borden WB, Valentine M. Hospital performance, the local economy, and the local workforce: findings from a US National Longitudinal Study. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borden WB, Blustein J. Valuing improvement in value-based purchasing. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:163–170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.962811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Integrated Healthcare Association. [Accessed March 30, 2016];Factsheet: Value Based Pay for Performance in California. 2015 http://www.iha.org/sites/default/files/resources/vbp4p-fact-sheet-final-20150925.pdf.

- 17.Yegian J, Yanagihara D. Value Based Pay for Performance in California. Integr Healthc Assoc. 2013 (Issue Brief No. 8) [Google Scholar]

- 18.California IHA. IHA Pay for Performance Report of Results for Measurement Year 2010. Integrated Healthcare Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartman T, Kukmerker K. Pay-for-Performance in State Medicaid Programs: A Survey of State Medicaid Directors and Programs. [Accessed September 19, 2015];Commonw Fund. 2007 Apr; http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2007/apr/pay-for-performance-instate-medicaid-programs--a-survey-of-state-medicaid-directors-and-programs.

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 28, 2015];Overview - Physician Quality Reporting System. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/. Published June 12, 2015.

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 28, 2015];Value Based Payment Modifier. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeedbackProgram/ValueBasedPaymentModifier.html. Published August 4, 2015.

- 22.Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S1–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 28, 2015];Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalPremier.html. Published January 9, 2013.

- 24.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, Rothberg MB, Benjamin EM, Ma A, Bratzler DW. Public Reporting and Pay for Performance in Hospital Quality Improvement. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:486–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glickman SW, Ou F-S, DeLong ER, Roe MT, Lytle BL, Mulgund J, Rumsfeld JS, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Schulman KA, Peterson ED. Pay for performance, quality of care, and outcomes in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297:2373–2380. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan AM. Effects of the Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration on Medicare Patient Mortality and Cost. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:821–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan AM, Blustein J, Casalino LP. Medicare’s Flagship Test Of Pay-For-Performance Did Not Spur More Rapid Quality Improvement Among Low-Performing Hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:797–805. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Werner RM, Kolstad JT, Stuart EA, Polsky D. The Effect Of Pay-For-Performance In Hospitals: Lessons For Quality Improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:690–698. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jha AK, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. The Long-Term Effect of Premier Pay for Performance on Patient Outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1606–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1112351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calikoglu S, Murray R, Feeney D. Hospital Pay-For-Performance Programs In Maryland Produced Strong Results, Including Reduced Hospital-Acquired Conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2649–2658. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/hospitalqualityinits/hospitalrhqdapu.html. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Frequently Asked Questions Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program Last Updated. 2012 Mar 9; https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/Downloads/FY-2013-Program-Frequently-Asked-Questions-about-Hospital-VBP-3-9-12.pdf.

- 33.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program. 2013 Mar; https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/Hospital_VBPurchasing_Fact_Sheet_ICN907664.pdf.

- 34.Wheeler B. Overview of the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Fiscal Year (FY) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2017. http://www.qualityreportingcenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/HVBP_021715_Overview-FY2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed March 31, 2016];Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Results for the CMS Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-10-26.html. Published October 26, 2015.

- 36.Ryan AM, Burgess JF, Pesko MF, Borden WB, Dimick JB. The early effects of Medicare’s mandatory hospital pay-for-performance program. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:81–97. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cashin C, Chi Y-L, Smith P, Borowitz M, Thomson, editors. Implications for health system performance and accountability. Open Univ Press; 2014. [Accessed August 27, 2015]. Paying for performance in health care. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series. http://www.euro.who.int/en/about-us/partners/observatory/publications/studies/paying-for-performance-in-health-care.-implications-for-health-system-performance-and-accountability. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blustein J, Weissman JS, Ryan AM, Doran T, Hasnain-Wynia R. Analysis raises questions on whether pay-for-performance in Medicaid can efficiently reduce racial and ethnic disparities. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2011;30:1165–1175. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doran T, Fullwood C, Gravelle H, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Hiroeh U, Roland M. Pay-for-Performance Programs in Family Practices in the United Kingdom. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:375–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa055505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutton M, Nikolova S, Boaden R, Lester H, McDonald R, Roland M. Reduced Mortality with Hospital Pay for Performance in England. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1821–1828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1114951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kristensen SR, Meacock R, Turner AJ, Boaden R, McDonald R, Roland M, Sutton M. Long-Term Effect of Hospital Pay for Performance on Mortality in England. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:540–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Damberg CL, Sorbero ME, Lovejoy SL, Martsolf GR, Raaen L, Mandel D. Measuring Success in Health Care Value-Based Purchasing Programs. [Accessed October 11, 2015];RAND. 2014 http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR306.html. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Werner RM, Bradlow ET. Relationship between Medicare’s hospital compare performance measures and mortality rates. JAMA. 2006;296:2694–2702. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Quality Forum. Risk Adjustment for Socioeconomic Status or Other Sociodemographic Factors. National Quality Forum; 2014. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2014/08/Risk_Adjustment_for_Socioeconomic_Status_or_Other_Sociodemographic_Factors.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frederick S, Loewenstein G, O’Donoghue T. Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review. J Econ Lit. 2002;40:351–401. doi: 10.1257/002205102320161311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-Dependent Model. Q J Econ. 1991;106:1039–1061. doi: 10.2307/2937956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herck PV, Smedt DD, Annemans L, Remmen R, Rosenthal MB, Sermeus W. Systematic review: Effects, design choices, and context of pay-for-performance in health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:247. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chien AT, Wroblewski K, Damberg C, Williams TR, Yanagihara D, Yakunina Y, Casalino LP. Do Physician Organizations Located in Lower Socioeconomic Status Areas Score Lower on Pay-for-Performance Measures? J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:548–554. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1946-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chatterjee P, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient experience in safety-net hospitals: implications for improving care and value-based purchasing. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1204–1210. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ross JS, Bernheim SM, Lin Z, Drye EE, Chen J, Normand S-LT, Krumholz HM. Based On Key Measures, Care Quality For Medicare Enrollees At Safety-Net And Non-Safety-Net Hospitals Was Almost Equal. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1739–1748. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryan AM. Will Value-Based Purchasing Increase Disparities in Care? N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2472–2474. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1312654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilman M, Hockenberry JM, Adams EK, Milstein AS, Wilson IB, Becker ER. The Financial Effect of Value-Based Purchasing and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program on Safety-Net Hospitals in 2014: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:427–436. doi: 10.7326/M14-2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ryan AM, McCullough CM, Shih SC, Wang JJ, Ryan MS, Casalino LP. The intended and unintended consequences of quality improvement interventions for small practices in a community-based electronic health record implementation project. Med Care. 2014;52:826–832. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper Z, Craig SV, Gaynor M, Reenen JV. The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2015. [Accessed February 3, 2016]. http://www.nber.org/papers/w21815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The Revised Medicare ACO Program: More Options … And More Work Ahead. [Accessed March 31, 2016];Health Affairs. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/06/16/the-revised-medicare-aco-program-more-options-and-more-work-ahead/

- 56.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; Medicare Shared Savings Program; Accountable Care Organizations-Revised Benchmark Rebasing Methodology, Facilitating Transition to Performance-Based Risk, and Administrative Finality of Financial Calculations. [Accessed March 31, 2016];Federal Register. 2016 81:5824–5872. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2016/02/03/2016-01748/medicare-program-medicare-shared-savings-program-accountable-care-organizations-revised-benchmark. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]