Abstract

Bell pepper is an economically important crop worldwide; however, production is restricted by a number of fungal diseases that cause significant yield loss. Chemical control is the most common approach adopted by growers to manage a number of these diseases. Monitoring for the development to resistance to fungicides in pathogenic fungal populations is central to devising integrated pest management strategies. Two fungal species, Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex (FIESC) and Colletotrichum truncatum are important pathogens of bell pepper in Trinidad. This study was carried out to determine the sensitivity of 71 isolates belonging to these two fungal species to fungicides with different modes of action based on in vitro bioassays. There was no significant difference in log effective concentration required to achieve 50% colony growth inhibition (LogEC50) values when field location and fungicide were considered for each species separately based on ANOVA analyses. However, the LogEC50 value for the Aranguez-Antracol location-fungicide combination was almost twice the value for the Maloney/Macoya-Antracol location-fungicide combination regardless of fungal species. LogEC50 values for Benomyl fungicide was also higher for C. truncatum isolates than for FIESC isolates and for any other fungicide. Cropping practices in these locations may explain the fungicide sensitivity data obtained.

Keywords: anthracnose, Fusarium, integrated pest management, sweet pepper

The top five ranked producers of bell peppers (Capscium annuum L.), between 2007 and 2011, were China, Mexico, Turkey, Indonesia, and Spain (FAOSTAT, 2011). For the grower, selection of bell pepper cultivars is dependent on disease resistance, growing conditions, performance and yield. Protected-culture technologies for pepper production offers the grower a greater level of control over growing conditions especially with respect to chemical use and fertilizer input (Correll and Thornsbury, 2013). Field-grown bell peppers are more susceptible to a range of bacterial, virus and fungal diseases and this continues to be a limiting factor to pepper production (Black et al., 1991).

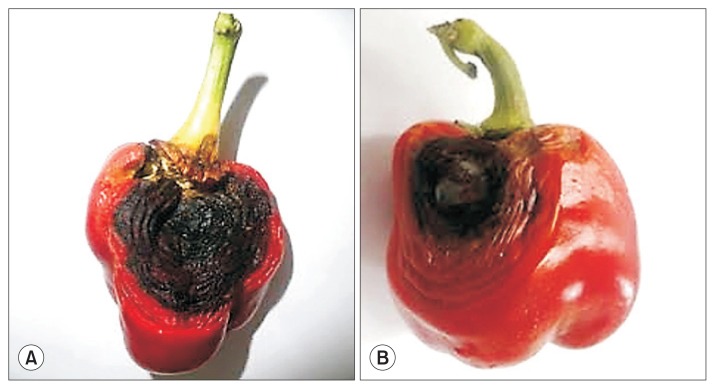

Bell pepper is an important crop grown throughout Trinidad and field production is mainly concentrated in the Northeast and Southeast regions (Mohammed, 2013). The cost of greenhouse production systems remains prohibitive, USD 1.13 per 0.5 kg for greenhouse production vs USD 0.48 per 0.5 kg for open field production (Seepersad et al., 2013). Barbados is the only current export market and exports have fluctuated between 2006 and 2010 perhaps as a result of changing market value. There has been a decline in the importation of bell peppers from 2008 to 2012 with the lowest recorded trade occurring in 2012 (Mohammed, 2013). Over the last five years, yield has been affected by fungal diseases that cause fruit rot. Several Colletotrichum species are implicated as causal agents of anthracnose in bell pepper, including C. gloeosporioides, C. coccodes, C. acutatum, and C. truncatum (syn. C. capsici; Damm et al., 2009). Different Colletotrichum species infect pepper at different stages of maturity, e.g., C. gloeosporioides and C. acutatum have been reported to infect both young and mature green fruit, whereas C. truncatum has been shown to infect mature red-fruits (Ramdial and Rampersad, 2015; Than et al., 2008). Colletotrichum is capable of causing quiescent infection where infection of the plant in the early stages of development, the fungus exhibits biotrophy and inactivity for most of the plant’s development, and then becomes necrotrophic during the ripening and senescence stages (Harp et al., 2008; Prusky and Lichter, 2007). Fruit rot can also extend to the seed cavity which may lead to infection of the seed. In Trinidad, C. truncatum infects mature red fruit and causes severe fruit rot. Symptoms are seen as a single, dry, large lesion or as multiple lesions (Fig. 1A). Field occurrence and yield loss are estimated between 90% and 100% and 40% and 60%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

(A) Symptoms of Colletotrichum truncatum infection on mature bell pepper fruit. (B) Symptoms of Fusarium sp. infection on mature bell pepper fruit.

Members of the Fusarium genus are economically important plant pathogens. They are ubiquitous fungi, found in almost every terrestrial ecosystem (Ploetz, 2006) and are known for causing disease in a wide range of weed, forest, ornamental and crop host species (Abu Bakar et al., 2013). Several Fusarium species are associated with fruit rot in susceptible Capsicum sp.; however, in Trinidad, Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex (FIESC) has been identified as the causal agent of fruit rot in bell pepper (Ramdial et al., 2016). Symptoms are seen as black, water-soaked lesions that begin around the calyx but can develop anywhere on the mature fruit (Fig. 1B). There is evidence of internal decay in some cases. To date, the disease has been detected in fields located in Northwest and Northeast Trinidad and yield loss is estimated between 30% and 50% of mature red fruit.

Although anthracnose disease resistance is available in some varieties of chili peppers, there are no bell pepper cultivars that are resistant to anthracnose or Fusarium (AVRDC, 1999, 2000; Yoon et al., 2004). Development of cultivars with a shorter ripening period or with a thicker waxy cuticle may allow the fruit to escape infection by the fungus (Harp et al., 2008; Lewis-Ivey et al., 2004). Chemical control is among the most commonly used strategies for management of fungal diseases (Gang et al., 2015). Chemical control of anthracnose includes use of benzimidazoles, strobilurins, dicarboximides, and demethylation inhibitors which are single-site mode-of-action fungicides (Young et al., 2010). However, for late maturing red peppers, maneb (Group M3), azoxystrobin (Quadris, Fungicide Resistance Action Committee [FRAC] Group 11), trifloxystrobin (Flint, FRAC Group 11), and pyraclostrobin (Cabrio, FRAC Group 11) have been suggested for the control of anthracnose (Alexander and Waldenmaier, 2000, 2001, 2003; Zitter, 2011). Marvel (2003) stated that azoxystrobin in combination with maneb, offers a high level of protection against anthracnose in green pepper in field trials. There are no fungicides registered to control Fusarium fruit rot in bell pepper.

Fungicide resistance can occur as a result of genetic mutations of target proteins; exclusions and expulsion of fungicidal compounds via intrinsic efflux pumps such as ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters; overexpression of target proteins; and detoxification of the fungicides through development of catabolic pathways (FRAC, 2014, 2015). Resistance arising from mutations in target proteins is reported for single-site inhibitors and there is less risk of developing resistance with multi-site inhibitors (FRAC, 2014). Monitoring the development of fungicide resistance is necessary to (i) detect for selection of resistant phenotypes after prolonged chemical use, (ii) streamline chemical control strategies and cost associated with chemical use, and (iii) reduce environmental impact due to accumulation of fungicides (Gang et al., 2015). This study was, therefore, conducted to determine the sensitivity of Fusarium and Colletotrichum isolates infecting bell pepper to fungicides with different modes of action.

Materials and Methods

Isolate collection

Seventeen fields were sampled for anthracnose fruit rot infection in the major production areas in Trinidad (see Tables 1 and 2 for sampling locations). Symptomatic fruit with diagnostic symptoms were collected and surface disinfested by rinsing in 70% ethanol for 1 min followed by another rinse in 0.6% sodium hypochlorite solution for 1 min. Samples were then washed three times in sterilized distilled water and dried on sterilized tissue paper in a laminar flow hood. A 4-mm3 block of tissue was cut from the edge of the lesion and placed in the center of STEA plates (2% water agar amended with 50 mg/l streptomycin and 50 mg/l tetracycline [Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA] and 5% absolute ethanol). STEA plates were incubated for five days at 25°C in the dark. After incubation, a 4-mm3 block of agar taken from the advancing mycelial edge of a 5-day old STEA culture was removed and placed in the center of a potato dextrose agar plate (PDA; Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK) supplemented with 50 mg/l streptomycin and 50 mg/l tetracycline (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Cultures were incubated for seven days at 25°C in the dark. Monoconidial cultures were subsequently obtained through serial dilution. Isolates were maintained on PDA slants at 4°C for temporary storage, and as conidial suspensions in 50% glycerol at −70°C for long-term storage.

Table 1.

LogEC50 values determined for isolates belonging to the Fusarium-incarnatum-equiseti species complex

| n | Location | Region* | Fungicide | Regression equation | R2-value | LogEC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Arang | Northwest | Antracol | y = 3.531× + 4.381 | 0.996 | 12.919 |

| 13 | Mal/Mac | North Central | Antracol | y = 5.467× + 8.152 | 0.992 | 7.654 |

| 25 | Arang | Northwest | Criptan | y = 3.423× + 5.104 | 0.927 | 13.116 |

| 13 | Mal/Mac | North Central | Criptan | y = 1.722× + 0.574 | 0.600 | 28.703 |

| 25 | Arang | Northwest | Benomyl | y = 4.182× + 3.552 | 0.883 | 11.107 |

| 13 | Mal/Mac | North Central | Benomyl | y = 13.624× + 11.327 | 0.835 | 2.839 |

| 25 | Arang | Northwest | Valete | y = 7.459× + 9.562 | 0.961 | 5.421 |

| 13 | Mal/Mac | North Central | Valete | y = 7.985× + 6.907 | 0.955 | 5.397 |

LogEC50, log effective concentration required to achieve 50% colony growth inhibition.

Region key: Arang, Aranguez (5 fields); Mal and Mac, Maloney (3 fields) and Macoya (3 fields).

Table 2.

LogEC50 values determined for Colletotrichum truncatum isolates infecting bell pepper in Trinidad

| n | Location | Region* | Fungicide | Regression equation | R2-value | LogEC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Arang | Northwest | Antracol | y = 3.569× + 5.902 | 0.991 | 12.356 |

| 10 | Mal/Mac | North Central | Antracol | y = 4.573× + 13.127 | 0.988 | 8.063 |

| 11 | BA/P | South | Antracol | y = 6.025× + 11.457 | 0.998 | 6.397 |

| 12 | Arang | Northwest | Criptan | y = 4.628× + 3.775 | 0.711 | 9.988 |

| 10 | Mal/Mac | North Central | Criptan | y = 5.394× + 8.779 | 0.978 | 7.642 |

| 11 | BA/P | South | Criptan | y = 4.776× + 12.937 | 0.925 | 7.76 |

| 12 | Arang | Northwest | Benomyl | y = 2.43× | 0.777 | 20.58 |

| 10 | Mal/Mac | North Central | Benomyl | y = 7.105× | 0.736 | 27.04 |

| 11 | BA/P | South | Benomyl | y = 2.339× + 0.086 | 0.526 | 21.34 |

| 12 | Arang | Northwest | Valete | y = 5.973× + 7.732 | 0.963 | 7.076 |

| 10 | Mal/Mac | North Central | Valete | y = 7.168× + 12.305 | 0.989 | 5.259 |

| 11 | BA/P | South | Valete | y = 8.733× + 12.216 | 0.969 | 4.327 |

LogEC50, log effective concentration required to achieve 50% colony growth inhibition.

Region key: Arang, Aranguez (5 fields); BA, Bonne Aventure (4 fields); Mal and Mac, Maloney (3 fields) and Macoya (3 fields); P, Penal (2 fields).

PCR amplification, sequencing and identification of isolates

Fresh mycelium was harvested from cultures grown in potato dextrose broth and used in genomic DNA extraction using the cetyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) extraction method. PCR amplification was carried out using two primers pairs that target the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rDNA region (ITS4/5 primers; White et al., 1990) and the translation elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1/2 primers) under published thermal cycling conditions (Geiser et al., 2004; O’Donnell et al., 2015). For a single 25 μl reaction, PCR components (Invitrogen; Life Technologies Co., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) included 1× PCR buffer; 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mMdNTP, 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase and 50 pmoles of each primer (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA). PCR amplification thermal conditions consisted of an initial denaturation of 5 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, 1 min at 72°C with a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were sequenced directly and in both directions (Amplicon Express, Pullman, WA, USA). Isolates were then identified based on Blast queries with cognate sequences deposited in GenBank and the FU-SARIUM-ID sequence repositories.

In vitro bioassay

The sensitivity of isolates to four fungicides (Antracol, Criptan, Benomyl, and Valete) was determined using the amended agar screening method. The selection of fungicides was based on confirmed use in bell pepper fields by growers in Trinidad (survey conducted by Ramdial, unpublished). A summary of each fungicide’s FRAC grouping, mode of action, registered for controlling anthracnose or Fusarium and evidence of resistance is given in Supplementary Table 1 (Davidse, 1986; Dirou and Stovold, 2005; Gordon, 2011; Jarvis et al., 1994; Lucas et al., 2015; Lukens, 1969; Owens and Novotny, 1959; Richmond and Somers, 1963; Rosenberger, 2013; Turechek, 2004). Stock solutions of the commercially available formulation of each fungicide were prepared in acetone (Rampersad, 2011; Zhang et al., 2010). PDA media were amended with 0, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0, and 100.0 μg/ml of fungicide. A total of 71 isolates were screened (N = 38 FIESC; N = 33 C. truncatum). Four replicates of each fungicide concentration were used for each isolate and the experiment was conducted twice. Cultures were prepared by removing a 4-mm3 block of mycelia from the leading edge of an actively growing 7-day-old culture and placing it mycelium-side-down in the center of fungicide-amended media. The plates were incubated at 25°C for five days and the radial diameter of each colony was measured (orthogonal measurements) for each isolate to determine percentage of relative growth inhibited compared to the growth on non-amended media. Mean values were used in subsequent analyses as values did not differ significantly between experiments. The log effective concentration required to achieve 50% colony growth inhibition (LogEC50) on fungicide-amended media was calculated for isolates based on in vitro bioassays.

Statistical tests

Linear regression analyses were conducted to determine the LogEC50 values for the fungal isolates according to field location. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the LogEC50 values (mycelia growth of the control vs the Log10 of the fungicide concentration) was carried out (Minitab v.17; Minitab, State College, PA, USA). A comparison of means LogEC50 values using Fisher’s least significant difference and Tukey’s multiple comparison of means tests was also done.

Results

The influence of species, fungicides used, as well as the location of isolate collection, on calculated LogEC50 values for each of the two fungal species were determined based on ANOVA analyses (Table 1, 2). The t-tests were also conducted to compare the LogEC50 values of FIESC isolates against those of C. truncatum isolates. With respect to FIESC, there was no significant influence of fungicide on LogEC50 values (P = 0.219). This was further confirmed by Tukey’s and Fisher’s tests where there were no significant differences among LogEC50 values of various fungicide groupings (P > 0.05), e.g., Criptan-Antracol (P = 0.456). There was also no significant influence of location on LogEC50 values (P = 0.938). It should be noted that the Bon Aventure/Penal location was not included in this analysis as no FIESC isolates were collected here.

ANOVAs were also performed on C. truncatum isolates, to assess the influence of fungicide use, and the location of sample collection, on the LogEC50 values calculated (Supplementary Table 2). It must be noted that C. truncatum isolates were obtained from the Bon Aventure and Penal locations, and, therefore, LogEC50 values were included in this analysis. Results showed significant influence of fungicide on LogEC50 values (P = 0.000). Both Tukey’s and Fisher’s tests indicated that mean LogEC50 values were grouped separately for Benomyl as these values were significantly higher than for the other fungicides for C. truncatum isolates. For the combined data set, however, results showed no significant influence of fungicides on LogEC50 values (P = 0.082). This was further confirmed by Tukey’s and Fisher’s tests where there were no significant differences among mean LogEC50 values and all means fell within the same grouping.

The effect of species and fungicide on LogEC50 values, the effect of species and location on LogEC50 values and the effect of location and fungicide on LogEC50 values were also determined separately (Supplementary Table 2). None of the paired factors had a significant effect on LogEC50 values (P > 0.05), e.g., species × fungicide (P = 0.293), species × location (P = 0.711), and location × fungicide (P = 0.314).

The t-tests were also performed to compare LogEC50 values of each species according to fungicide and field location. Equal variances were assumed for all tests, with 95% confidence interval. When the test was carried out to compare LogEC50 values for all Aranguez isolates versus all Maloney and Macoya isolates of both species regardless of fungicide screened (combined data set), there was a significant difference in mean LogEC50 values (P = 0.005). Aranguez isolates had a significantly higher LogEC50. When LogEC50 values of all C. truncatum and FIESC isolates for individual locations and fungicides were compared, the Aranguez-Antracol combination was significantly different from all other pairwise comparisons (P = 0.004). Similarly, the Maloney/Macoya-Antracol combination (P = 0.017) was significantly different from other pairwise combinations. All other location-fungicide pairwise comparisons of LogEC50 values for all isolates were not significant (P > 0.05). For example, Aranguez-Criptan (P = 0.086), Maloney/Macoya-Criptan (P = 0.334), Aranguez-Benomyl (P = 0.185), Maloney/Macoya-Benomyl (P = 0.256), and Aranguez-Valete (P = 0.084).

Discussion

Two fungal species, FIESC and C. truncatum are important pathogens of bell pepper in Trinidad. There is no single fungicide that is effective against all fungal pepper diseases. Therefore, it is necessary to screen different chemistries to optimize chemical use for management of different fungal diseases in bell pepper. This study was carried out to determine the efficacy of various fungicides with different modes of action to control 71 isolates belonging to two fungal species that affect bell pepper in Trinidad.

Another important consideration is fungicide resistance management. Colletotrichum spp. are reported to become resistant to benzimidazole fungicides after prolonged use with ultimate selection for resistant isolates in the fungal population (Ramdial et al., 2016). The risk factors for developing fungicide resistance in a given fungal population depends on a number of interacting factors including, (i) the fitness advantage offered to resistant mutants, (ii) the population size, reproductive rate and history of resistance of the target pathogen, (iii) repetitive and sustained fungicide use especially single-site inhibitors, (iv) no integration with other complementary non-chemical control methods, (v) exceeding the dose rate and timing of application, (vi) use of chemicals as an eradicant rather than preventative application, and (vii) cross-resistance among single-site inhibitors as is the case with benzimidazoles (Brent and Hollomon, 2007). Alternating products in different fungicide groups is, therefore, highly recommended.

The findings of this study indicated that there was no significant difference in LogEC50 values when field location and fungicide were considered for each species separately based on ANOVA analyses. However, the LogEC50 value for the Aranguez-Antracol location-fungicide combination was almost twice the value for the Maloney/Macoya-Antracol location-fungicide combination regardless of fungal species. Antracol is a multi-site inhibitor and the risk of developing resistance is low. The higher LogEC50 values obtained for this fungicide for Aranguez may be a reflection of difference in dosage requirement for these two fungal species infecting bell pepper in Trinidad and not necessarily a case of resistance. Resistance to Antracol has not yet been reported (Bayer CropScience Egypt, 2016).

There was a significant difference in LogEC50 values calculated for Benomyl fungicide compared to the values obtained for the other three chemicals. C. truncatum had the highest LogEC50 values for this fungicide compared to the other three chemicals. Ramdial et al. (2016) determined that C. truncatum infecting bell pepper was resistant to Benomyl. This fungicide was included in this study for comparison with the LogEC50 values for FIESC isolates infecting bell pepper. These values, therefore, reflect resistance to this fungicide by C. truncatum isolates. FIESC isolates had significantly lower LogEC50 values compared to C. truncatum. Molecular work to characterize FIESC isolates for the detection of the E198A genotype among Benomyl resistant isolates would have to be carried out to confirm whether the LogEC50 values obtained for this fungus species reflect resistance or dosage requirements for this fungicide.

By examining the history of agriculture at the Aranguez, Maloney and Macoya locations, the fungicide sensitivity data obtained in this study may be explained. In the late 1800s to early 1900s, Aranguez was originally run as a sugar cane estate (North Aranguez) and rice plantation (South Aranguez) (Gomes, 1981). By the late 1930s, as the petroleum industry expanded in Trinidad, sugar cane and rice production declined, and vegetable crop cultivation which was previously done on a small scale, progressively increased and completely replaced sugar cane cultivation. Year-round vegetable crop cultivation was boosted by the implementation of an irrigation scheme through the construction of a dam, access roads, rapidly expanding urban districts, and food shortages during World War II (1941–1945). However, by 1950, growers reported a decline in soil fertility perhaps as a result of soil depletion from sugar cane cultivation, and a difficulty in cultivating in certain soil types, e.g., silty-clay loam, with some areas remaining unproductive due to salt water infiltration (Bell, 1950). As a result, fields were developed outside of Aranguez, in Maloney, Wallerfield, Macoya, and Valencia areas. To date, Aranguez is still known as a major vegetable production area in Trinidad with intensive crop cultivation supported by a heavy reliance on agro-chemical use, e.g., fertilizers, pesticides, fungicides and herbicides (Kenny, 2008). It is proposed that chemical use, particularly in Aranguez, is related to a history of (i) poor soil quality, (ii) monoculture practices, (iii) unavailability of high performing cultivars which may have contributed to plants with relatively higher sensitivity to infection, and (iv) indiscriminate use of chemicals all of which may have resulted in fungal populations with detectable levels of resistance to certain chemicals or with relatively higher LogEC50 values to certain chemicals.

Apart from screening for sensitivity to differently acting fungicides, to further optimize strategies to control anthracnose and Fusarium fruit rot in bell pepper in Trinidad, it may be useful to quantify the environmental spore load in both productive and abandoned fields. Research should also be conducted to determine the relationship between fruit rot and spore pressure, fruit load, fruit position on the plant, growing conditions, and cultivar. Although anthracnose has been detected in all fields sampled in this study, FIESC has only been found in fields located in Northwest and Northeast Trinidad.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Research and Publications Grant no. CRP.3.NOV11.8.

References

- Abu Bakar AI, Nur Ain Izzati MZ, Umi Kalsom Y. Diversity of Fusarium species associated with post-harvest fruit rot disease of tomato. Sains Malaysiana. 2013;42:911–920. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SA, Waldenmaier CM. Evaluation of fungicides for control of anthracnose in bell pepper, 2000. Fungicide Nematicide Tests. 2000;56:V30. doi: 10.1094/FN56. Online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SA, Waldenmaier CM. Management of anthracnose in bell pepper, 2001. Fungicide Nematicide Tests. 2001;57:V055. doi: 10.1094/FN57. Online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SA, Waldenmaier CM. Management of anthracnose in bell pepper, 2002. Fungicide Nematicide Tests. 2003;58:V049. doi: 10.1094/FN58. Online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [AVRDC] Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center. AVRDC report 1998. AVRDC; Tainan, Taiwan: 1999. Off-season tomato, pepper and eggplant; pp. 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- [AVRDC] Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center. AVRDC report 1999. AVRDC; Tainan, Taiwan: 2000. Off-season tomato, pepper and eggplant; pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer CropScience Egypt. [1 November 2016].];2016 onwards http://www.egypt.cropscience.bayer.com/en/Products/Fungicides/Antracol.aspx.

- Bell LA. ATA thesis. The University of the West Indies; Kingston, Jamaica: 1950. A social, economic and agricultural survey of peasant agriculture at Aranguez Estate, Trinidad, B.W.I., 1949–50. [Google Scholar]

- Black LL, Green SK, Hartman GL, Poulos JM. Pepper diseases: a field guide. Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center (AVRDC); Tainan, Taiwan: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brent KJ, Hollomon DW. FRAC monograph No 2. 2nd ed. The Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC); Brussels, Belgium: 2007. Fungicide resistance: the assessment of risk; pp. 2–39. [Google Scholar]

- Correll S, Thornsbury S. [1 November 2016];Vegetables and pulses outlook: Special Article, Commodity Highlight: Bell Peppers. 2013 onwards URL https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/vgs353/41021_vgs353sa1.pdf.

- Damm U, Woudenberg JHC, Cannon PF, Crous PW. Colletotrichum species with curved conidia from herbaceous hosts. Fung Divers. 2009;39:45–87. [Google Scholar]

- Davidse LC. Benzimidazole fungicides: mechanism of action and biological impact. Ann Rev Phytopathol. 1986;24:43–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.24.090186.000355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dirou J, Stovold G. Fungicide management program to control mango anthracnose. Primefact. 2005;19:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. [1 November 2016];Production and Trade. 2011 onwards URL http://faostat.fao.org/

- [FRAC] Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. [1 November 2016];Mode of action. 2014 onwards URL http://www.frac.info/resistance-overview/mechanisms-of-fungicide-resistance.

- [FRAC] Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. [9 January 2017];FRAC code list 2015: fungicides sorted by mode of action (including FRAC code numbering) 2015 onwards URL http://www.frac.info/docs/default-source/publications/frac-code-list/fraccode-list-2015.pdf?sfvrsn=2.

- Gang GH, Cho HJ, Kim HS, Kwack YB, Kwak YS. Analysis of fungicide sensitivity and genetic diversity among Colletotrichum species in sweet persimmon. Plant Pathol J. 2015;31:115–122. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.03.2015.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser DM, Jiménez-Gasco MM, Kang S, Makalowska I, Veeraraghavan N, Ward TJ, Zhang N, Kuldau GA, O’Donnell K. FUSARIUM-ID v. 1.0: a DNA sequence database for identifying Fusarium. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2004;110:473–479. doi: 10.1023/B:EJPP.0000032386.75915.a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes PI. The social and cultural factors involved in production by small farmers in Trinidad and Tobago of tomatoes and cabbage and their marketing. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); Paris, France: 1981. SS-82/WS/2. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon EB. Handbook of pesticide toxicology. 2nd ed. Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harp TL, Pernezny K, Lewis Ivey ML, Miller SA, Kuhn PJ, Datnoff L. The etiology of recent pepper anthracnose outbreaks in Florida. Crop Prot. 2008;27:1380–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2008.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis WR, Khosla SK, Barrie SD. Fusarium stem and fruit rot of sweet pepper in Ontario green houses. Can Plant Dis. 1994;74:131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny JS. The biological diversity of Trinidad and Tobago: a naturalist’s notes. Prospect Press; Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago: 2008. p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Ivey ML, Nava-Diaz C, Miller SA. Identification and management of Colletotrichum acutatum on immature bell peppers. Plant Dis. 2004;88:1198–1204. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.11.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas JA, Hawkins NJ, Fraaije BA. The evolution of fungicide resistance. In: Sariaslani S, editor. Advances in applied microbiology. Vol. 90. Academic Press; Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2015. pp. 30–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens RJ. Heterocyclic nitrogen compounds. In: Torgeson DC, editor. Fungicides: an advanced treatise. Volume II Chemistry and physiology. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 1969. pp. 345–445. [Google Scholar]

- Marvel JK. MSc thesis. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; Blacksburg, VI, USA: 2003. Biology and control of pepper anthracnose. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed A. Market profile for sweet pepper in Trinidad and Tobago. Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute (CARDI); 2013 onwards. [1 November 2016]. URL http://www.cardi.org/cfc-pa/files/downloads/2013/11/Publ-22-Market-Profile-Sweet-pepper-TT-Aziz-M.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Ward TJ, Robert VARG, Crous PW, Geiser DM, Kang S. DNA-sequence based identification of Fusarium: current status and future directions. Phytoparasitica. 2015;43:583–595. doi: 10.1007/s12600-015-0484-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens RG, Novotny HM. Mechanisms of action of the fungicide captan [N-(trichloromethylthio)-4-cyclohexene-1,2-dicarboximide] Contrib Boyce Thompson Inst. 1959;20:171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ploetz RC. Fusarium-induced diseases of tropical, perennial crops. Phytopathology. 2006;96:648–652. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-96-0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusky D, Lichter A. Activation of quiescent infections by postharvest pathogens during transition from the biotrophic to the necrotrophic stage. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;268:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramdial H, Hosein FN, Rampersad SN. Detection and molecular characterization of benzimidazole resistance among Colletotrichum truncatum isolates infecting bell pepper in Trinidad. Plant Dis. 2016;100:1146–1152. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-15-0995-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramdial H, Rampersad SN. Characterization of Colletotrichum spp. causing anthracnose of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) in Trinidad. Phytoparasitica. 2015;43:37–49. doi: 10.1007/s12600-014-0428-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rampersad SN. A rapid colorimetric microtiter bioassay to evaluate fungicide sensitivity among Verticillium dahliae isolates. Plant Dis. 2011;95:248–255. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-10-10-0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond DV, Somers E. Studies on the fungitoxicity of captan. III. Relation between the sulphydryl content of fungal spores and their uptake of captan. Ann Appl Biol. 1963;52:327–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1963.tb03755.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger D. [1 November 2016];The Captan conundrum: scab control vs. phytotoxicity. 2013 onwards URL http://ipm.uconn.edu/documents/raw2/html/409.php?aid=409.

- Seepersad G, Iton A, Compton P, Lawrence J. [1 November 2016];Financial aspects of greenhouse vegetables production systems in Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago. 2013 onwards URL http://www.cardi.org/cfc-pa/files/downloads/2013/11/Publ-20-Financial-Aspects-Greenhouses-Govind-S.pdf.

- Than PP, Jeewon R, Hyde KD, Pongsupasamit S, Mongkolporn O, Taylor PWJ. Characterization and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum species associated with anthracnose on chili (Capsicum spp.) in Thailand. Plant Pathol. 2008;57:562–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2007.01782.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turechek B. Strawberry anthracnose control. [1 November 2016];New York Berry News. 2004 3(6) URL http://www.fruit.cornell.edu/berry/ipm/ipmpdfs/stranthraccontrol.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JB, Yang DC, Lee WP, Ahn SY, Park HG. Genetic resources resistant to anthracnose in the genus Capsicum. J Korean Soc Hortic Sci. 2004;45:318–323. [Google Scholar]

- Young JR, Tomaso-Peterson M, Tredway LP, de la Cerda K. Occurrence and molecular identification of azoxystrobin-resistant Colletotrichum cereale isolates from golf course putting greens in the Southern United States. Plant Dis. 2010;94:751–757. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-6-0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CQ, Liu YH, Zhu GN. Detection and characterization of benzimidazole resistance of Botrytis cinerea in greenhouse vegetables. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2010;126:509–515. doi: 10.1007/s10658-009-9557-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zitter TA. [1 November 2016];Pepper disease control: it starts with the seed. 2011 onwards URL http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/NewsArticles/PepDisease_Con.htm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.