Abstract

Purpose

Various genetic variants have been reported to be linked to an increased risk of meningioma. However, no confirmed conclusion has been obtained. The purpose of the study was to investigate potential meningioma-associated gene polymorphisms, based on published evidence.

Materials and methods

An updated meta-analysis was performed in September 2016. After electronic database searching and study screening, we selected eligible case-control studies and extracted data for meta-analysis, using Mantel–Haenszel statistics. P-values, pooled odds ratios (ORs), and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results

We finally selected eight genes with ten polymorphisms: MLLT10 rs12770228, CASP8 rs1045485, XRCC1 rs1799782, rs25487, MTHFR rs1801133, rs1801131, MTRR rs1801394, MTR rs1805087, GSTM1 null/present, and GSTT1 null/present. Results of meta-analyses showed that there was increased meningioma risk in case groups under all models of MLLT10 rs12770228 (all OR >1, P<0.001), compared with control groups. Similar results were observed under the allele, homozygote, dominant, and recessive models of MTRR rs1801394 (all OR >1, P<0.05), and the heterozygote and dominant models of MTHFR rs1801131 in the Caucasian population (all OR >1, P<0.05). However, no significantly increased meningioma risks were observed for CASP8 rs1045485, XRCC1 rs25487, rs1799782, MTHFR rs1801133, MTR rs1805087, or GSTM1/GSTT1 null mutations.

Conclusion

Our updated meta-analysis provided statistical evidence for the role of MLLT10 rs12770228, MTRR rs1801394, and MTHFR rs1801131 in increased susceptibility to meningioma.

Keywords: meningioma, meta-analysis, gene, SNP

Introduction

Meningiomata, common slow-growing intracranial tumors, originate from the derivatives between the meninges and meningeal gap of the central nervous system.1,2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO) grading system, grade I meningioma lesions are usually benign, whereas grade II–III meningioma lesions are mostly atypical, anaplastic, or malignant.3,4 Chromosomal abnormalities (chromosomes 22, 1p, 9p, 10p, 11, 14q, 15, 17, and 18q) and associated genetic variants have been reported to be associated with meningioma risk.4–6 For example, mutation of the NF2 gene is reportedly related to meningioma risk.7 However, the role of various gene polymorphisms in susceptibility to meningioma remains unconfirmed.

In the present study, we aimed to analyze all the relevant publications and investigate potential functional gene polymorphisms associated with meningioma risk. Ten single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of eight genes – MLLT10 rs12770228, CASP8 rs1045485, XRCC1 rs1799782, XRCC1 rs25487, MTHFR rs1801133, MTHFR rs1801131, MTRR rs1801394, MTR rs1805087, GSTM1 null/present, and GSTT1 null/present – were selected from 20 eligible articles to conduct our meta-analysis.

There were several previous meta-analyses for associations between meningioma risk and gene polymorphisms, including MTHFR rs1801133, MTRR rs1801394, MTR rs1805087, GSTM1 null/present, and GSTT1 null/present.8–13 However, an updated meta-analysis was still required. Moreover, no previous meta-analyses have been conducted to evaluate the association between MTHFR rs1801131, MLLT10 rs12770228, CASP8 rs1045485, XRCC1 rs1799782, rs25487 polymorphisms and meningioma risks. Our data highlighted the positive association between MLLT10 rs12770228, MTRR rs1801394, MTHFR rs1801131, and increased meningioma risk.

Materials and methods

Information sources

We retrieved the available articles from the online databases PubMed, Embase, Central, Web of Science, and CNKI/Wanfang in September 2016. The following search terms were used: “polymorphism, genetic” or “polymorphisms, genetic” or “genetic polymorphism” or “polymorphism (genetics)” or “genetic polymorphisms” or “polymorphism” or “variant” or “variants” or “mutation” or “mutations” or “SNP” or “single nucleotide polymorphism”; “meningioma” or “meningiomas” or “angioblastic meningiomas” or “angiomatous meningiomas” or “clear cell meningiomas” or “fibrous meningiomas” or “hemangioblastic meningiomas” or “intracranial meningiomas” or “intraventricular meningiomas” or “malignant meningiomas” or “multiple meningiomas” or “meningiomatosis” or “microcystic meningioma” or “olfactory groove meningioma” or “papillary meningioma” or “posterior fossa meningioma” or “psammomatous meningiomas” or “secretory meningioma” or “sphenoid wing meningioma” or “spinal meningioma” or “transitional meningioma” or “xanthomatous meningioma” or “benign meningiomas” or “cerebral convexity meningioma”.

Eligibility criteria and data extraction

We screened and collected eligible studies based on our exclusion/inclusion criteria. The selected case-control studies had to contain genotype distributions of the case-control group. Genotype distribution in the control group had to be in line with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Exclusion criteria were comments, reviews, and letters; meeting abstracts; cases, trials, or not polymorphisms; not clinical data; other genes for which the number of case-control studies on specific variants was fewer than three; other diseases; meta-analyses; and lack of usable data. Then, four investigators independently performed methodological quality assessment using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS; http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp), and extracted the specific data, mainly genes, SNP, first author, year of publication, country, ethnicity, genotype frequencies of case-control, source of control, disease group, P-values of HWE test, genotyping methods, number of studies, sample size, and NOS score. NOS scores ≥7 mean a high-quality study. Emails were sent for unavailable data, and a discussion was needed for discrepancies.

Data synthesis

Stata/SE 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was utilized. P-values of association, summary odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated via Mantel–Haenszel statistics, based on the allele, homozygote, heterozygote, dominant, and recessive models. Two-sided P-values less than 0.05 were interpreted as statistically different; χ2 tests were used for HWE P-values.

Heterogeneity analysis and publication bias

Cochran’s Q test and I 2 statistic were applied for assessment of potential between-study heterogeneity. P-values for Q tests >0.1 or I 2 index <25% indicate the existence of overall statistically significant heterogeneity and the utilization of a fixed-effect model. Otherwise, a random-effect model was used.14,15 To analyze the main source of homogeneity, subgroup analysis by ethnicity and sensitivity analysis were conducted. In addition, Egger’s test and Begg’s test were carried out to evaluate potential publication bias.16–18

Results

Study selection and characteristics

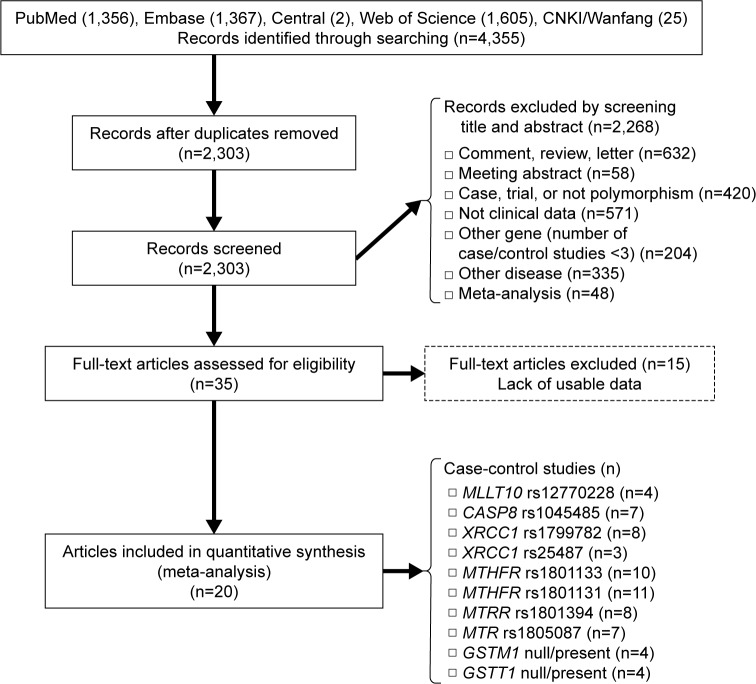

To identify studies on the association between potential genetic variants and meningioma risk, five online databases (PubMed, Embase, Central, Web of Science, and CNKI/Wanfang) were searched in September 2016. A flow diagram of publication search and study screening for the meta-analysis is shown in Figure 1. The PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) statement was followed.19 A total of 4,355 potentially relevant articles were retrieved initially from the databases. After the removal of duplicated articles, 2,268 articles were excluded by screening title and abstract, with reasons shown in Figure 1. A total of 35 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 15 were excluded for lack of usable data. As a result, 20 articles with ten polymorphisms of eight genes met our eligibility criteria and were selected for the meta-analysis.20–39 Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the articles included. NOS scores of all the studies were larger than or equal to 7, which indicated high quality. No significant deviation from HWE was found for any of the studies. The SNPs MLLT10 rs12770228, CASP8 rs1045485, XRCC1 rs1799782, XRCC1 rs25487, MTHFR rs1801133, MTHFR rs1801131, MTRR rs1801394, MTR rs1805087, GSTM1 null/present, and GSTT1 null/present were analyzed (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of publication search and study screening for the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Year | Country/region | Ethnicity | Gene | SNP | Case

|

Disease group | Control

|

Source of controls | HWE, P-value | Genotyping methods | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM/Mm/mm | MM/Mm/mm | |||||||||||

| Ahn et al39 | 2002 | South Korea | Asian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 16/13/3 | Meningioma | 91/129/34 | PB | 0.27 | PCR-RFLP | 7 |

| Bethke et al38 | 2009 | Finland | Caucasian | CASP8 | rs1045485 | 60/16/0 | Meningioma | 65/7/0 | PB | 0.66 | Illumina customized GoldenGate array | 7 |

| Denmark | Caucasian | CASP8 | rs1045485 | 81/20/0 | 84/23/1 | PB | 0.67 | |||||

| UK – South | Caucasian | CASP8 | rs1045485 | 92/21/6 | 93/24/1 | PB | 0.68 | |||||

| UK – North | Caucasian | CASP8 | rs1045485 | 128/37/2 | 133/29/4 | PB | 0.13 | |||||

| Sweden | Caucasian | CASP8 | rs1045485 | 115/27/2 | 115/27/1 | PB | 0.67 | |||||

| Bethke et al37 | 2008 | UK – North | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 80/73/20 | Meningioma | 94/64/17 | PB | 0.22 | Illumina GoldenGate array | 7 |

| UK – North | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 57/98/19 | 73/78/24 | PB | 0.66 | |||||

| UK – North | Caucasian | MTRR | rs1801394 | 54/83/37 | 74/78/23 | PB | 0.73 | |||||

| UK – North | Caucasian | MTR | rs1805087 | 113/54/7 | 106/60/8 | PB | 0.89 | |||||

| UK – Southeast | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 54/59/8 | 62/48/13 | PB | 0.42 | |||||

| UK – Southeast | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 50/57/14 | 48/60/15 | PB | 0.57 | |||||

| UK – Southeast | Caucasian | MTRR | rs1801394 | 41/57/23 | 39/59/25 | PB | 0.76 | |||||

| UK – Southeast | Caucasian | MTR | rs1805087 | 77/39/5 | 75/42/6 | PB | 0.97 | |||||

| Sweden | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 61/77/11 | 64/66/19 | PB | 0.76 | |||||

| Sweden | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 64/68/17 | 82/57/10 | PB | 0.98 | |||||

| Sweden | Caucasian | MTRR | rs1801394 | 39/84/26 | 53/74/22 | PB | 0.64 | |||||

| Sweden | Caucasian | MTR | rs1805087 | 98/45/6 | 94/51/4 | PB | 0.34 | |||||

| Denmark | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 44/57/9 | 53/43/17 | PB | 0.1 | |||||

| Denmark | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 45/55/10 | 56/45/12 | PB | 0.52 | |||||

| Denmark | Caucasian | MTRR | rs1801394 | 41/47/22 | 40/55/18 | PB | 0.90 | |||||

| Denmark | Caucasian | MTR | rs1805087 | 73/33/4 | 70/40/3 | PB | 0.33 | |||||

| Finland | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 38/31/8 | 37/32/8 | PB | 0.78 | |||||

| Finland | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 46/26/5 | 47/25/5 | PB | 0.51 | |||||

| Finland | Caucasian | MTRR | rs1801394 | 26/37/14 | 30/33/14 | PB | 0.36 | |||||

| Finland | Caucasian | MTR | rs1805087 | 50/24/3 | 56/17/4 | PB | 0.1 | |||||

| Cacina et al36 | 2015 | Turkey | Caucasian | CASP8 | rs1045485 | 28/8/3 | Meningioma | 66/42/6 | PB | 0.84 | PCR-RFLP | 7 |

| Cengiz et al35 | 2008 | Turkey | Caucasian | XRCC1 | rs25487 | 25/41/5 | Meningioma | 43/41/3 | PB | 0.07 | PCR-RFLP | 8 |

| De Roos et al34 | 2003 | US | Caucasian | GSTM1 | Present/null | 85b/84c | Meningioma | 254b/321c | HB | – | PCR | 7 |

| GSTT1 | Present/null | 121b/38c | 445b/100c | HB | – | |||||||

| Dobbins et al33 | 2011 | Germany | Caucasian | MLLT10 | rs12770228 | 309/426/123 | Meningioma | 328/302/74 | PB | 0.72 | a | 7 |

| UK | Caucasian | MLLT10 | rs12770228 | 144/187/73 | 361/321/76 | PB | 0.71 | |||||

| Scandinavia | Caucasian | MLLT10 | rs12770228 | 145/158/47 | 463/424/91 | PB | 0.67 | |||||

| Egan et al32 | 2015 | US | Caucasian | MLLT10 | rs12770228 | 111/111/46 | Meningioma | 287/267/74 | PB | 0.33 | TaqMan assays | 7 |

| Elexpuru-Camiruaga et al31 | 1995 | UK | Caucasian | GSTM1 | Present/null | 22b/27c | Meningioma | 262b/315c | HB | – | PCR | 7 |

| UK | Caucasian | GSTT1 | Present/null | 26b/21c | 403b/91c | HB | – | |||||

| Huang et al30 | 2012 | China | Asian | XRCC1 | rs1799782 | 100/80/25 | Meningioma | 95/102/21 | PB | 0.39 | Snapshot multiplex | 8 |

| China | Asian | XRCC1 | rs1799782 | 53/24/11 | <50 years old | 41/51/12 | PB | 0.52 | ||||

| China | Asian | XRCC1 | rs1799782 | 47/56/14 | ≥50 years old | 54/51/9 | PB | 0.52 | ||||

| China | Asian | XRCC1 | rs1799782 | 27/20/7 | Male | 29/36/9 | PB | 0.67 | ||||

| China | Asian | XRCC1 | rs1799782 | 73/60/18 | Female | 66/66/12 | PB | 0.42 | ||||

| Huang et al29 | 2015 | China | Asian | XRCC1 | rs1799782 | 63/41/20 | Skull-base meningioma | 95/102/21 | PB | 0.39 | Snapshot multiplex | 8 |

| Kafadar et al28 | 2006 | Turkey | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 20/12/3 | Meningioma | 53/38/7 | PB | 0.96 | PCR-RFLP | 9 |

| Kiuru et al27 | 2008 | Mixed | Caucasian | XRCC1 | rs1799782 | 469/50/2 | Meningioma | 1,377/177/2 | PB | 0.13 | PCR-RFLP | 9 |

| Mixed | Caucasian | XRCC1 | rs25487 | 212/233/74 | 645/728/176 | PB | 0.17 | |||||

| Li et al26 | 2013 | China | Asian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 101/147/69 | Meningioma | 159/129/32 | PB | 0.44 | PCR-RFLP | 9 |

| China | Asian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 205/96/16 | 201/98/21 | PB | 0.06 | |||||

| Pinarbasi et al25 | 2005 | Turkey | Caucasian | GSTM1 | Present/null | 12b/11c | Meningioma | 116b/37c | HB | – | PCR | 7 |

| Turkey | Caucasian | GSTT1 | Present/null | 17b/6c | 122b/31c | HB | – | |||||

| Rajaraman et al24 | 2010 | US | Caucasian | XRCC1 | rs1799782 | 104/18/0 | Meningioma | 394/73/1 | HB | 0.21 | TaqMan assay | 7 |

| US | Caucasian | XRCC1 | rs25487 | 56/62/14 | 205/201/72 | HB | 0.05 | |||||

| Rajaraman et al23 | 2007 | US | Caucasian | CASP8 | rs1045485 | 117/38/5 | Meningioma | 426/118/6 | HB | 0.87 | Medium-throughput TaqMan assay | 7 |

| Schwartzbaum et al22 | 2007 | Mixed | Caucasian | GSTM1 | Present/null | 68b/108c | Meningioma | 193b/237c | PB | – | PCR | 8 |

| Mixed | Caucasian | GSTT1 | Present/null | 149b/27c | 362b/68c | PB | – | |||||

| Semmler et al21 | 2008 | Germany | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 131/133/26 | Meningioma | 132/135/20 | PB | 0.06 | PCR-RFLP | 8 |

| Germany | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 116/142/32 | Meningioma | 132/123/32 | PB | 0.68 | ||||

| Germany | Caucasian | MTR | rs1805087 | 197/81/12 | Meningioma | 184/92/11 | PB | 0.91 | ||||

| Germany | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 10/7/1 | WHO grade III | 132/135/20 | PB | 0.91 | ||||

| Germany | Caucasian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 7/10/1 | WHO grade III | 132/123/32 | PB | 0.91 | ||||

| Germany | Caucasian | MTR | rs1805087 | 18/0/0 | WHO grade III | 184/92/11 | PB | 0.91 | ||||

| Zhang et al20 | 2013 | China | Asian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 184/157/50 | WHO grade I | 289/245/66 | PB | 0.2 | PCR-RFLP | 8 |

| China | Asian | MTRR | rs1801394 | 135/176/80 | WHO grade I | 225/282/93 | PB | 0.77 | ||||

| China | Asian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 79/67/21 | WHO grade II | 289/245/66 | PB | 0.2 | ||||

| China | Asian | MTRR | rs1801394 | 59/74/34 | WHO grade II | 225/282/93 | PB | 0.77 | ||||

| China | Asian | MTHFR | rs1801131 | 20/17/5 | WHO grade III | 289/245/66 | PB | 0.2 | ||||

| China | Asian | MTRR | rs1801394 | 15/19/8 | WHO grade III | 225/282/93 | PB | 0.77 |

Notes: M, major allele; m, minor allele.

Illumina Infinium HD human 662 quad or OmniExpress BeadChip, competitive allele-specific KASP chemistry;

number of samples with GSTM1 or GSTT1 null genotype;

number of samples with GSTM1 or GSTT1 null/present genotype. ‘–’ indicates not available.

Abbreviations: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale; PB, population-based; PCR-RFLP, polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment-length polymorphism; HB, hospital-based; WHO, World Health Organization.

Table 2.

Genes and SNPs included in the meta-analysis

| Gene | Chromosome | SNP | Sequence | Global MAF | Variants | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLLT10 | 10:21494705 | rs12770228 | CTTTCGCTTGCGGTTTGCAACCCCT [A/G]GGGTGGGTCTGACCCCGCGCGGCAC |

A =0.156/781 | C895T | Transcription factor and partner gene involved in several chromosomal rearrangements |

| CASP8 | 2:201284866 | rs1045485 | GCTTCATTTTGAGATCAAGCCCCAC [C/G]ATGACTGCACAGTAGAGCAAATCTA |

C =0.0527/264 | D302H | Apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase |

| XRCC1 | 19:43553422 | rs1799782 | GAGGCCGGGGGCTCTCTTCTTCAGC [C/T]GGATCAACAAGACATCCCCAGGTGA |

A =0.1238/620 | R194W | DNA repair of single-strand breaks and base excision |

| 19:43551574 | rs25487 | CGCATGCGTCGGCGGCTGCCCTCCC [A/G]GAGGTAAGGCCTCACACGCCAACCC |

T =0.2604/1,304 | Q399R | ||

| MTHFR | 1:11796321 | rs1801133 | TTGAAGGAGAAGGTGTCTGCGGGAG [C/T]CGATTTCATCATCACGCAGCTTTTC |

A =0.2454/1,229 | C677T | Catalyzes the conversion of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to |

| 1:11794419 | rs1801131 | TGGGGGGAGGAGCTGACCAGTGAAG [A/C]AAGTGTCTTTGAAGTCTTCGTTCTT |

G =0.2494/1,249 | A1298C | 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, and a cosubstrate for homocysteine remethylation to methionine | |

| MTRR | 5:7870860 | rs1801394 | AGGCAAAGGCCATCGCAGAAGAAAT [A/G]TGTGAGCAAGCTGTGGTACATGGAT |

G =0.3642/1,824 | A66G | Involved in the reductive regeneration of cobalamin cofactor required for the maintenance of methionine synthase in a functional state |

| MTR | 1:236885200 | rs1805087 | GAAGAATATGAAGATATTAGACAGG [A/G]CCATTATGAGTCTCTCAAGGTAAGT |

G =0.2183/1,093 | A2756G | Cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase, catalyzes the final step in methionine biosynthesis |

| GSTM1 | – | – | – | – | Null/present | Member of GST family that conjugates with glutathione and functions in the detoxification of carcinogens, environmental toxins and products of oxidative stress |

| GSTT1 | – | – | – | – | Null/present | Member of GST family that catalyzes the conjugation of reduced glutathione to a variety of electrophilic and hydrophobic compounds |

Note: ‘–’ indicates not available.

Abbreviations: SNPs, single-nucleotide polymorphisms; MAF, minor allele frequency; GST, glutathione S-transferase; A, adenine; G, guanine; C, cytosine; T, thymine.

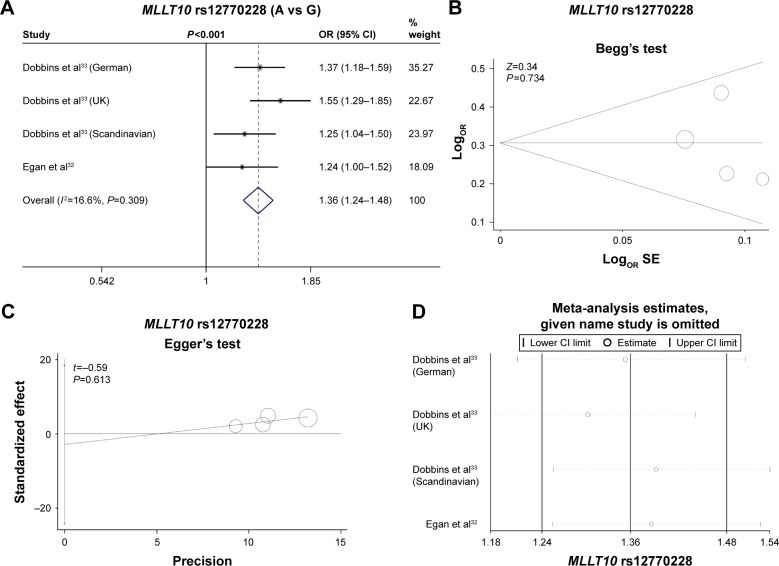

MLLT10 rs12770228

We first evaluated the association between rs12770228 of MLLT10 and meningioma risk. As shown in Figure 2A and Table 3, a fixed-effect model was used under the allele (A vs G), homozygote (AA vs GG) and recessive (AA vs GG+GA) models, due to low degree or no heterogeneity (heterogeneity, all P>0.1, I2<25%), whereas a random-effect model was applied for others. Pooled analysis data suggested that increased meningioma risk was detected under all genetic models (Table 3, test of association, all ORs >1, P<0.001). In addition, the existence of publication bias was excluded (Figure 2B and C, Table 4, Begg’s test, Egger’s test, all P>0.05). We also performed a sensitivity meta-analysis and found that the corresponding pooled OR value did not differ significantly from that of the overall meta-analysis (Figure 2D for allele model; data not shown for other models). These results suggested that the MLLT10 rs12770228 A/G polymorphism may be associated with increased meningioma risk.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the association between the MLLT10 polymorphism and meningioma risk under the allele model.

Notes: (A) Forest plot analysis; (B) Begg’s test with size graph symbol by weights; (C) Egger’s test with size graph symbol by weights; and (D) sensitivity meta-analysis. Weights are from fixed-effect analysis. The “given name study is omitted” was produced by the STAT12.0 software. It means the given name studies were omitted, and the meta-analysis data by other studies were showed.

Abbreviations: A, adenine; G, guanine; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Table 3.

Pooled analysis of the associations between MLLT10, CASP8, XRCC1, MTHFR, MTRR, and MTR polymorphisms and meningioma risk

| Gene | SNP | Comparison | Number of studies | Sample size

|

Test of association

|

Heterogeneity

|

Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | OR (95% CI) | P-value | I2 | P-value | |||||

| MLLT10 | rs12770228 | A vs G | 4 | 1,880 | 3,068 | 1.36 (1.24–1.48) | <0.001 | 16.6 | 0.309 | F |

| AA vs GG | 4 | 1,880 | 3,068 | 1.84 (1.53–2.23) | <0.001 | 0 | 0.438 | F | ||

| GA vs GG | 4 | 1,880 | 3,068 | 1.32 (1.13–1.54) | <0.001 | 27.7 | 0.246 | R | ||

| GA+AA vs GG | 4 | 1,880 | 3,068 | 1.42 (1.23–1.64) | <0.001 | 28.7 | 0.24 | R | ||

| AA vs GG+GA | 4 | 1,880 | 3,068 | 1.36 (1.24–1.48) | <0.001 | 0 | 0.552 | F | ||

| CASP8 | rs1045485 | C vs G | 7 | 806 | 1,271 | 1.14 (0.94–1.4) | 0.181 | 2.6 | 0.406 | F |

| CC vs GG | 6 | 730 | 1,199 | 1.67 (0.86–3.26) | 0.129 | 5.5 | 0.382 | F | ||

| GC vs GG | 7 | 806 | 1,271 | 1.06 (0.8–1.4) | 0.687 | 26.4 | 0.227 | R | ||

| GC+CC vs GG | 7 | 806 | 1,271 | 1.11 (0.89–1.39) | 0.181 | 14.7 | 0.318 | F | ||

| CC vs GG+GC | 6 | 730 | 1,199 | 1.14 (0.94–1.4) | 0.102 | 3.6 | 0.393 | F | ||

| XRCC1 | rs1799782 | T vs C | 8 | 1,382 | 2,896 | 0.94 (0.82–1.07) | 0.327 | 0 | 0.469 | F |

| TT vs CC | 8 | 1,382 | 2,896 | 1.22 (0.89–1.69) | 0.219 | 0 | 0.83 | F | ||

| CT vs CC | 8 | 1,382 | 2,896 | 0.75 (0.61–0.94) | 0.010 | 34.2 | 0.155 | R | ||

| CT+TT vs CC | 8 | 1,382 | 2,896 | 0.82 (0.7–0.97) | 0.018 | 23.8 | 0.24 | F | ||

| TT vs CC+CT | 8 | 1,382 | 2,896 | 1.43 (1.05–1.95) | 0.022 | 0 | 0.969 | F | ||

| XRCC1 | rs25487 | A vs G | 3 | 722 | 2,114 | 1.08 (0.89–1.31) | 0.440 | 37 | 0.205 | R |

| AA vs GG | 3 | 722 | 2,114 | 1.14 (0.67–1.95) | 0.632 | 49.3 | 0.139 | R | ||

| GA vs GG | 3 | 722 | 2,114 | 1.09 (0.85–1.4) | 0.495 | 27.8 | 0.25 | R | ||

| GA+AA vs GG | 3 | 722 | 2,114 | 1.1 (0.87–1.39) | 0.429 | 25.3 | 0.262 | R | ||

| AA vs GG+GA | 3 | 722 | 2,114 | 1.09 (0.63–1.86) | 0.766 | 54.2 | 0.112 | R | ||

| MTHFR | rs1801133 | T vs C | 10 | 1,323 | 1,883 | 1.14 (0.93–1.39) | 0.222 | 64.2 | 0.003 | R |

| TT vs CC | 10 | 1,323 | 1,883 | 1.31 (0.87–1.98) | 0.201 | 52 | 0.027 | R | ||

| CT vs CC | 10 | 1,323 | 1,883 | 1.19 (0.95–1.49) | 0.132 | 43.8 | 0.066 | R | ||

| CT+TT vs CC | 10 | 1,323 | 1,883 | 1.19 (0.92–1.53) | 0.180 | 58.9 | 0.009 | R | ||

| TT vs CC+CT | 10 | 1,323 | 1,883 | 1.22 (0.87–1.71) | 0.239 | 36.6 | 0.115 | R | ||

| MTHFR | rs1801131 | C vs A | 11 | 1,855 | 3,331 | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) | 0.335 | 0 | 0.97 | F |

| CC vs AA | 11 | 1,855 | 3,331 | 1.01 (0.82–1.24) | 0.597 | 0 | 0.829 | F | ||

| AC vs AA | 11 | 1,855 | 3,331 | 1.13 (0.99–1.29) | 0.060 | 0 | 0.793 | F | ||

| AC+CC vs AA | 11 | 1,855 | 3,331 | 1.11 (0.98–1.25) | 0.108 | 0 | 0.935 | F | ||

| CC vs AA+AC | 11 | 1,855 | 3,331 | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.574 | 0 | 0.594 | F | ||

| MTRR | rs1801394 | G vs A | 8 | 1,231 | 2,437 | 1.18 (1.06–1.31) | 0.002 | 0 | 0.682 | F |

| GG vs AA | 8 | 1,231 | 2,437 | 1.4 (1.14–1.73) | 0.002 | 0 | 0.756 | F | ||

| AG vs AA | 8 | 1,231 | 2,437 | 1.1 (0.93–1.3) | 0.250 | 0 | 0.67 | F | ||

| AG+GG vs AA | 8 | 1,231 | 2,437 | 1.18 (1.01–1.37) | 0.036 | 0 | 0.622 | F | ||

| GG vs AA+AG | 8 | 1,231 | 2,437 | 1.33 (1.1–1.61) | 0.003 | 0 | 0.883 | F | ||

| MTR | rs1805087 | G vs A | 7 | 939 | 1,210 | 0.89 (0.75–1.04) | 0.140 | 0 | 0.51 | F |

| GG vs AA | 7 | 939 | 1,210 | 0.96 (0.6–1.53) | 0.867 | 0 | 0.985 | F | ||

| AG vs AA | 7 | 939 | 1,210 | 0.84 (0.69–1.02) | 0.074 | 10.4 | 0.35 | F | ||

| AG+GG vs AA | 7 | 939 | 1,210 | 0.85 (0.7–1.02) | 0.084 | 5.7 | 0.384 | F | ||

| GG vs AA+AG | 7 | 939 | 1,210 | 1.02 (0.64–1.61) | 0.946 | 0 | 0.986 | F | ||

Abbreviations: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; F, fixed; R, random; A, adenine; G, guanine; C, cytosine; T, thymine.

Table 4.

Begg’s test and Egger’s test data

| Gene | SNP | Comparison | Begg’s test

|

Egger’s test

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| z | P-value | t | P-value | |||

| MLLT10 | rs12770228 | A vs G | 0.34 | 0.734 | −0.59 | 0.613 |

| AA vs GG | 1.02 | 0.308 | −0.32 | 0.778 | ||

| GA vs GG | 1.02 | 0.308 | −2.02 | 0.18 | ||

| GA+AA vs GG | 0.34 | 0.734 | −1.24 | 0.341 | ||

| AA vs GG+GA | 0.34 | 0.734 | 0.27 | 0.814 | ||

| CASP8 | rs1045485 | C vs G | 0.6 | 0.548 | −0.17 | 0.87 |

| CC vs GG | 0.38 | 0.707 | −0.61 | 0.572 | ||

| GC vs GG | 0.6 | 0.548 | −0.4 | 0.708 | ||

| GC+CC vs GG | 0.90 | 0.368 | −0.31 | 0.77 | ||

| CC vs GG+GC | 0.38 | 0.707 | −0.64 | 0.56 | ||

| XRCC1 | rs1799782 | T vs C | 0.12 | 0.902 | −0.71 | 0.506 |

| TT vs CC | 0.37 | 0.711 | 0.36 | 0.731 | ||

| CT vs CC | 0.37 | 0.711 | −0.79 | 0.46 | ||

| CT+TT vs CC | 0.62 | 0.536 | −0.6 | 0.569 | ||

| TT vs CC+CT | −0.12 | 1 | 0.28 | 0.792 | ||

| XRCC1 | rs25487 | A vs G | 0 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.784 |

| AA vs GG | 0 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.955 | ||

| GA vs GG | 1.04 | 0.296 | 4.08 | 0.153 | ||

| GA+AA vs GG | 1.04 | 0.296 | 1.3 | 0.418 | ||

| AA vs GG+GA | 0 | 1 | −0.16 | 0.897 | ||

| MTHFR | rs1801133 | T vs C | 1.43 | 0.152 | −2.33 | 0.048 |

| TT vs CC | 0.54 | 0.592 | −2.51 | 0.036 | ||

| CT vs CC | 1.61 | 0.107 | −1.88 | 0.097 | ||

| CT+TT vs CC | 1.43 | 0.152 | −2.23 | 0.056 | ||

| TT vs CC+CT | 0.54 | 0.592 | −1.96 | 0.086 | ||

| MTHFR | rs1801131 | C vs A | 1.09 | 0.276 | −0.59 | 0.571 |

| CC vs AA | 1.09 | 0.276 | −2.14 | 0.061 | ||

| AC vs AA | 0.93 | 0.35 | 1.45 | 0.181 | ||

| AC+CC vs AA | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.92 | 0.38 | ||

| CC vs AA+AC | 1.4 | 0.161 | −2.37 | 0.042 | ||

| MTRR | rs1801394 | G vs A | 1.11 | 0.266 | −0.55 | 0.605 |

| GG vs AA | 1.11 | 0.266 | −0.64 | 0.544 | ||

| AG vs AA | −0.12 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.753 | ||

| AG+GG vs AA | −0.12 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.99 | ||

| GG vs AA+AG | 1.61 | 0.108 | −1.21 | 0.272 | ||

| MTR | rs1805087 | G vs A | 0 | 1 | −1.55 | 0.183 |

| GG vs AA | 0.3 | 0.764 | −0.73 | 0.497 | ||

| AG vs AA | 0.3 | 0.764 | −0.95 | 0.385 | ||

| AG+GG vs AA | 0.3 | 0.764 | −1.21 | 0.28 | ||

| GG vs AA+AG | 0.3 | 0.764 | −0.46 | 0.662 | ||

Abbreviations: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; A, adenine; G, guanine; C, cytosine; T, thymine.

CASP8 rs1045485

The association between CASP8 rs1045485 and susceptibility to meningioma was then analyzed. As shown in Table 3, a fixed-effect model was utilized for the allele, homozygote, dominant, and recessive models (heterogeneity, all P>0.1, I2<25%), but not the heterozygote model (Table 3, I2=26.4%). The genetic association between the rs1045485 G/C allele frequency of CASP8 and increased meningioma risk was obtained under the C vs G model (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.94–1.4; P=0.181). In addition, we did not observe significantly increased meningioma risk in any genetic model (Table 3, test of association, all P>0.05). No publication bias was observed under any model either (Table 4, Begg’s test, Egger’s test, all P>0.05). Sensitivity meta-analyses further confirmed the results (data not shown). Therefore, the CASP8 rs1045485 polymorphism seems not to be associated with meningioma risk.

XRCC1 rs1799782 and rs25487

Next, we conducted meta-analyses of the associations between XRCC1 rs1799782 and rs25487 polymorphisms and meningioma risk. For XRCC1 rs1799782, no or low heterogeneity was observed, and a fixed-effect model was thus used for all genetic models (Table 3, heterogeneity, all P>0.1, I2<25%), apart from the heterozygote model (I2=34.2%). The results of Table 3 show that significant differences were observed under the heterozygote (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61–0.94; P=0.01), dominant (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.7–0.97; P=0.018), and recessive models (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.05–1.95; P=0.022), but not other models. Furthermore, subgroup analyses based on ethnicity were performed under all models. A similar change for increased meningioma risk was observed in the Asian population under the heterozygote, dominant, and recessive models (Table 5). Begg’s test and Egger’s test data excluded the presence of large publication bias (Table 4, Begg’s test and Egger’s test, all P>0.05).

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis of the association between XRCC1, MTHFR, and MTRR polymorphisms and meningioma risk

| Comparison |

XRCC1 rs1799782

|

MTHFR rs1801133

|

MTHFR rs1801131

|

MTRR rs1801394

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | Caucasian | Asian | Caucasian | Asian | Caucasian | Asian | Caucasian | |

| m vs M | ||||||||

| Studies, n | 6 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| Case-control | 739/872 | 643/2,024 | 349/574 | 974/1,309 | 917/2,120 | 938/1,211 | 600/1,800 | 631/637 |

| OR | 0.95 | 0.89 | 1.19 | 1.11 | 1.02 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 1.19 |

| 95% CI | 0.82–1.1 | 0.68–1.17 | 0.42–3.22 | 0.97–1.27 | 0.9–1.16 | 0.94–1.23 | 1.01–1.34 | 1.02–1.4 |

| P-value | 0.511 | 0.408 | 0.775 | 0.129 | 0.73 | 0.301 | 0.032 | 0.03 |

| mm vs MM | ||||||||

| Studies, n | 6 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| Case-control | 739/872 | 643/2,024 | 349/574 | 974/1,309 | 917/2,120 | 938/1,211 | 600/1,800 | 631/637 |

| OR | 1.2 | 2.3 | 1.44 | 1.18 | 1.08 | 0.92 | 1.41 | 1.4 |

| 95% CI | 0.86–1.66 | 0.45–11.8 | 0.22–9.34 | 0.86–1.62 | 0.81–1.44 | 0.68–1.26 | 1.06–1.86 | 1.01–1.94 |

| P-value | 0.283 | 0.32 | 0.703 | 0.302 | 0.592 | 0.618 | 0.016 | 0.04 |

| Mm vs MM | ||||||||

| Studies, n | 6 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| Case-control | 739/872 | 643/2,024 | 349/574 | 974/1,309 | 917/2,120 | 938/1,211 | 600/1,800 | 631/637 |

| OR | 0.7 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 0.99 | 1.32 | 1.02 | 1.21 |

| 95% CI | 0.52–0.95 | 0.64–1.14 | 0.35–3.26 | 0.97–1.42 | 0.83–1.19 | 1.09–1.59 | 0.82–1.27 | 0.94–1.54 |

| P-value | 0.022 | 0.282 | 0.902 | 0.11 | 0.931 | 0.004 | 0.827 | 0.136 |

| Mm+mm vs MM | ||||||||

| Studies, n | 6 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| Case-control | 739/872 | 643/2,024 | 349/574 | 974/1,309 | 917/2,120 | 938/1,211 | 600/1,800 | 631/637 |

| OR | 0.8 | 0.87 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 1.01 | 1.23 | 1.12 | 1.26 |

| 95% CI | 0.66–0.97 | 0.66–1.15 | 0.31–4.17 | 0.98–1.4 | 0.85–1.19 | 1.03–1.48 | 0.91–1.37 | 1–1.59 |

| P-value | 0.026 | 0.331 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 0.932 | 0.023 | 0.277 | 0.052 |

| mm vs MM+Mm | ||||||||

| Studies, n | 6 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| Case-control | 739/872 | 643/2,024 | 349/574 | 974/1,309 | 917/2,120 | 938/1,211 | 600/1,800 | 631/637 |

| OR | 1.41 | 2.33 | 1.48 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 0.8 | 1.39 | 1.26 |

| 95% CI | 1.03–1.93 | 0.45–11.99 | 0.42–5.25 | 0.79–1.44 | 0.83–1.43 | 0.6–1.08 | 1.08–1.78 | 0.94–1.68 |

| P-value | 0.031 | 0.31 | 0.547 | 0.674 | 0.552 | 0.146 | 0.01 | 0.121 |

Notes: M, major allele; m, minor allele.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

For XRCC1 rs25487, a random-effect model was used under all genetic models (Table 3, heterogeneity, all I2>25%). No significant difference and no publication bias were observed under any genetic models (Table 3, test of association, all P>0.05; Table 4, Begg’s test and Egger’s test, all P>0.05). Sensitivity meta-analyses further confirmed these results (data not shown). The data failed to provide strong evidence for an association between XRCC1 rs1799782 or rs25487 polymorphisms and increased meningioma risk.

MTHFR rs1801133 and rs1801131

As shown in Table 3, a random-effect model was used for MTHFR rs1801133 (heterogeneity, all I2>25%), while a fixed-effect model was used for MTHFR rs1801131 (heterogeneity, all P>0.1, I2=0%). No significant difference was observed for rs1801133 or rs1801131 under any genetic model (Table 3, test of association, all P>0.05). No publication bias was observed under any models (Table 4, Begg’s test and Egger’s test, all P>0.05), apart from the allele and homozygote models of rs1801133 (Table 4, Egger’s test, P<0.05). Subgroup analyses of ethnicity further showed a significant difference only for rs1801131 under the heterozygote (AC vs AA, OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.09–1.59; P=0.004) and dominant (AC+CC vs AA, OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.03–1.48; P=0.023) models of rs1801131 in the Caucasian population (Table 5), suggesting that the AC genotype of MTHFR rs1801131 might be associated with increased meningioma risk in the Caucasian population. Sensitivity meta-analyses further confirmed these results (data not shown).

MTRR rs1801394 and MTR rs1805087

Fixed-effect models were used for MTRR rs1801394 and MTR rs1805087 (Table 3, heterogeneity, all P>0.1, I2<25%). Significantly increased meningioma risk was observed for MTRR rs1801394 under the allele (G vs A), homozygote (GG vs AA), dominant (AG+GG vs AA), and recessive (GG vs AA+AG) models (Table 3, test of association, all OR>1, P<0.05). Nevertheless, no increased meningioma risk was observed for MTR rs1805087 under any model (Table 3, test of association, all P>0.05). Subgroup analyses further indicated that there was increased meningioma risk for MTRR rs1801394 under the allele, homozygote, and recessive models in the Asian population and the allele and homozygote models in the Caucasian population (Table 5, test of association, all P<0.05). No publication bias was detected for MTRR rs1801394 or MTR rs1805087 under any model (Table 4, Begg’s test and Egger’s test, all P>0.1). The results were further confirmed by sensitivity meta-analyses (data not shown). These data demonstrated that MTRR rs1801394, but not MTR rs1805087, is more likely to be linked to increased meningioma risk.

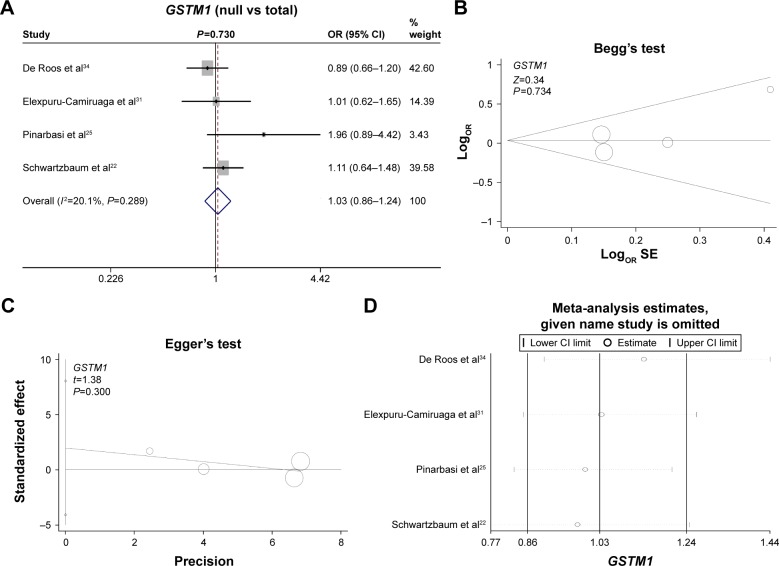

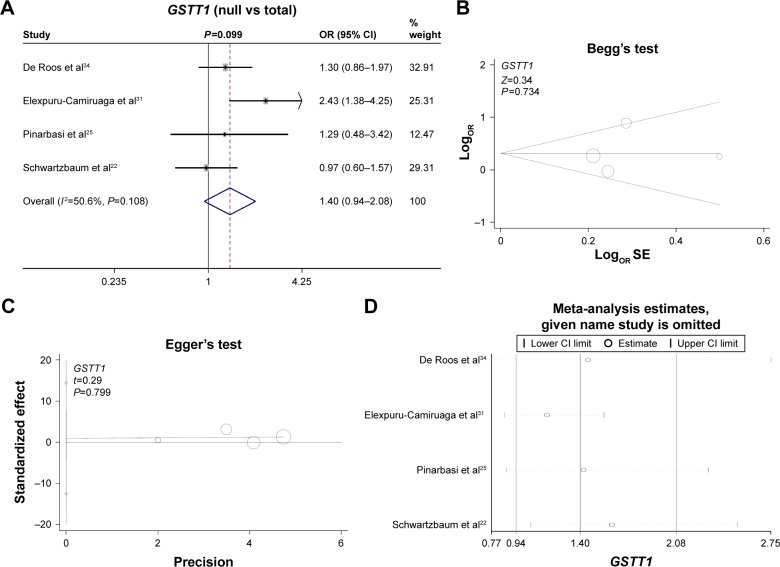

GSTM1 and GSTT1 null/present

Finally, we investigated the genetic relationship between the null/present genotype of GSTM1 and GSTT1 and meningioma risk. A fixed model was used for GSTM1 (Figure 3A, heterogeneity, P=0.289, I2=20.1%), whereas a random model was used for GSTT1 (Figure 4A, heterogeneity, P=0.108, I2=50.6%). No increased or decreased meningioma risk was observed for the null genotype of GSTM1 (Figure 3A, test of association, P=0.73) or GSTT1 (Figure 4A, test of association, P=0.099). No publication bias was detected (Figure 3B and C, Figure 4B and C, Begg’s test and Egger’s test, all P>0.05). Sensitivity meta-analyses (Figures 3D and 4D) further confirmed the results. These results demonstrated that the polymorphisms of GSTM1 and GSTT1 may not be associated with meningioma risk.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of the association between the GSTM1 polymorphism and meningioma risk.

Notes: (A) Forest plot analysis; (B) Begg’s test with size graph symbol by weights; (C) Egger’s test with size graph symbol by weights; and (D) sensitivity meta-analysis. Weights are from fixed-effect analysis. The “given name study is omitted” was produced by the STAT12.0 software. It means the given name studies were omitted, and the meta-analysis data by other studies were showed.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of the association between the GSTT1 polymorphism and meningioma risk.

Notes: (A) Forest plot analysis; (B) Begg’s test with size graph symbol by weights; (C) Egger’s test with size graph symbol by weights; and (D) sensitivity meta-analysis. Weights are from random-effect analysis. The “given name study is omitted” was produced by the STAT12.0 software. It means the given name studies were omitted, and the meta-analysis data by other studies were showed.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Discussion

In the present study, we performed an updated meta-analysis to investigate potential genetic variants associated with meningioma risk. Ten genetic variants of eight genes were targeted. These genes can be classified into five categories: 1) chromosomal rearrangement-associated gene, MLLT10; 2) apoptosis-associated gene, CASP8; 3) DNA repair-associated gene, XRCC1; 4) folate-metabolism genes, MTHFR, MTRR, and MTR; 5) and drug metabolism-related genes, GSTM1 and GSTT1.

Folate metabolism-associated gene mutations have been reported to be associated with several diseases.12,40 The MTHFR protein, a kind of folate-metabolizing enzyme, is required for the methylation of homocysteine to methionine.41–44 Both the MTRR and MTR genes are also indispensable for the folate metabolic pathway.40 Polymorphisms of MTHFR, MTRR, and MTR have been reported to be linked to susceptibility to meningioma in certain populations. For example, MTHFR rs1801133 or MTRR rs1801394 was found to be associated with meningioma risk in the Chinese population.20,26 However, the role of MTHFR polymorphisms in the presence of meningioma is still conflicting. For instance, there was no significant genetic association between MTHFR rs1801133 and meningioma risk in the Turkish population.28 The TT genotype of MTHFR rs1801133 may be related to the lower risk of meningioma in the Korean population.39

Ding et al conducted a meta-analysis of nine case-control studies, and found that the CT genotype of MTHFR rs1801133 might be linked to high meningioma risk in Caucasians.13 Xu et al found that significantly increased meningioma risk was only observed under the TC vs CC model in a meta-analysis of four studies.9 A meta-analysis by Zeng et al showed that the MTRR rs1801394 polymorphism (seven case-control studies), but not MTR rs1805087 (seven case-control studies), may be associated with meningioma risk in adults.8 We removed data that did not meet the HWE, such as the rs1805087 data of Zhang et al,20 and added data from case-control studies, such as the WHO grade III meningioma group.21 As such, MTHFR rs1801133 (eleven case-control studies), MTRR rs1801394 (eight case-control studies) and MTR rs1805087 (seven case-control studies, all in the Caucasian population) were enrolled in the present updated meta-analysis. Our results indicated that MTRR rs1801394, but not MTHFR rs1801133 or MTR rs1805087, is likely to be associated with meningioma risk, and the AC genotype of MTHFR rs1801131 may confer high susceptibility to meningioma in the Caucasian population. The precise molecular mechanisms of MTHFR and MTR mutations in the incidence of meningioma remain unclear. Due to its close relationship with the synthesis, methylation, and repair of DNA, folate is essential for the production or maintenance of normal cells and the inhibition of tumor cells.45–47 It is possible that the harmful mutation of MTHFR rs1801131 or MTRR rs1801394 confers susceptibility to meningioma via abnormal of enzyme activity and folate-involved DNA metabolism. More experiments are needed.

In addition to folate-metabolism genes, susceptibility loci of drug metabolism-related genes GSTM1 and GSTT1, apoptosis-associated gene CASP8, DNA repair-associated gene XRCC1, and chromosomal rearrangement-associated gene MLLT10 have also been reported in various clinical diseases.48–52 For instance, GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms might be associated with renal cell carcinoma risk or treatment outcomes of breast cancer.48,49 XRCC1 polymorphisms are likely linked to the risk of lung cancer in Caucasian population.51 Cryptic XPO1–MLLT10 translocation was related to homeobox A-locus deregulation in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.52 Here, the results of our meta-analysis under all genetic models showed that the rs12770228 polymorphism of MLLT10 was significantly associated with increased meningioma risk. However, no strong association between GSTM1, GSTT1, CASP8, XRCC1 and meningioma susceptibility was obtained. The negative associations between GSTM1 and GSTT1 null/present and meningioma risk were partly in line with previous results on the role of GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms in brain-tumor risk.10,11 In spite of this, the possibility of potential roles of these polymorphisms in inherited meningioma risk still cannot be ruled out.

Limitations

Although the strict exclusion and inclusion criteria were utilized to select eligible studies, several limitations in our meta-analysis must be acknowledged. We tried our best to search the electronic databases for relevant articles, and analyzed the potential meningioma-associated genetic variants via meta-analysis. Multiple genes, such as CDKN2 and PON1, were initially retrieved.23,53 However, genes for which the number of case-control studies on specific variants was fewer than three were removed. As such, only eight genes were collected. We admit that there was a very limited number of included studies and very small sample size in case-control studies for our meta-analysis. Considering the limitation of small study numbers on the evaluation efficiency of publication bias via Begg’s test,16 there is still the potential of publication bias, which may have affected our conclusions.

Even though the Mantel–Haenszel statistics under the random-effect model and sensitivity analyses were used for between-study heterogeneity, there were small sample sizes, and other unpublished or unavailable data are still needed. SNPs, disease characteristics, and other environmental effect modifiers contribute to meningioma risk. Several factors, such as ionizing radiation, estrogen level, and traumatic brain injury, might be involved in the complicated etiology or pathology of meningiomas.54–56 Unfortunately, only stratified analysis according to ethnic background was performed for XRCC1 rs1799782, MTHFR rs1801133, rs1801131, and MTRR rs1801394. More subgroup analysis based on more factors (eg, sex, disease type, or other clinical characteristics) were needed for a proper judgment of the genetic association between the measured variants and meningioma risk.

Very limited genome-wide association study (GWAS) data, genome-wide SNP linkage-disequilibrium mapping, or exome sequencing was obtained.33,57,58 We found that the MLLT10 gene was identified from the GWAS data on meningioma risk.32,33 However, the positive association of MTRR rs1801394 and MTHFR rs1801131 failed to obtain the support of GWAS data. Further investigations with more subjects are warranted to confirm the role of CASP8, XRCC1, MTHFR, MTRR, MTR, GSTM1, GSTT1, and other genes identified from high-throughput analysis, such as PIAS2 and KATNAL2.

Conclusion

Our updated meta-analysis concluded that MLLT10 rs12770228 and MTRR rs1801394 polymorphisms may be meningioma risk factors. Also, the AC genotype of MTHFR rs1801131 appears to be associated with increased susceptibility to meningioma in the Caucasian population.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Bi WL, Mei Y, Agarwalla PK, Beroukhim R, Dunn IF. Genomic and epigenomic landscape in meningioma. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016;27(2):167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanti MJ, Marson AG, Chavredakis E, Jenkinson MD. The impact of epilepsy on the quality of life of patients with meningioma: a systematic review. Br J Neurosurg. 2016;30(1):23–28. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1080215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karsy M, Guan J, Cohen A, Colman H, Jensen RL. Medical management of meningiomas: current status, failed treatments, and promising horizons. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016;27(2):249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexiou GA, Markoula S, Gogou P, Kyritsis AP. Genetic and molecular alterations in meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113(4):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domingues P, Gonzalez-Tablas M, Otero A, et al. Genetic/molecular alterations of meningiomas and the signaling pathways targeted. Oncotarget. 2015;6(13):10671–10688. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith MJ. Germline and somatic mutations in meningiomas. Cancer Genet. 2015;208(4):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahronowitz I, Xin W, Kiely R, Sims K, MacCollin M, Nunes FP. Mutational spectrum of the NF2 gene: a meta-analysis of 12 years of research and diagnostic laboratory findings. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(1):1–12. doi: 10.1002/humu.20393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng XT, Lu JT, Tang XJ, Weng H, Luo J. Association of methionine synthase rs1801394 and methionine synthase reductase rs1805087 polymorphisms with meningioma in adults: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2014;2(3):432–436. doi: 10.3892/br.2014.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu C, Yuan L, Tian H, Cao H, Chen S. Association of the MTHFR C677T polymorphism with primary brain tumor risk. Tumour Biol. 2013;34(6):3457–3464. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0922-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sima XT, Zhong WY, Liu JG, You C. Lack of association between GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms and brain tumour risk. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(1):325–328. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai R, Crevier L, Thabane L. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferases and the risk of adult brain tumors: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(7):1784–1790. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han D, Shen C, Meng X, et al. Methionine synthase reductase A66G polymorphism contributes to tumor susceptibility: evidence from 35 case-control studies. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(2):805–816. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding H, Liu W, Yu X, Wang L, Shao L, Yi W. Risk association of meningiomas with MTHFR C677T and GSTs polymorphisms: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(11):3904–3914. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakkinstian A, McElduff P, D’Este C, Duffy D, Attia J. A method for meta-analysis of molecular association studies. Stat Med. 2005;24(9):1291–1306. doi: 10.1002/sim.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Zhou YW, Shi HP, et al. 5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), methionine synthase (MTRR), and methionine synthase reductase (MTR) gene polymorphisms and adult meningioma risk. J Neurooncol. 2013;115(2):233–239. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1218-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semmler A, Simon M, Moskau S, Linnebank M. Polymorphisms of methionine metabolism and susceptibility to meningioma formation: laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(5):999–1004. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/5/0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartzbaum JA, Ahlbom A, Lönn S, et al. An international case-control study of glutathione transferase and functionally related polymorphisms and risk of primary adult brain tumors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(3):559–565. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajaraman P, Wang SS, Rothman N, et al. Polymorphisms in apoptosis and cell cycle control genes and risk of brain tumors in adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(8):1655–1661. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajaraman P, Hutchinson A, Wichner S, et al. DNA repair gene polymorphisms and risk of adult meningioma, glioma, and acoustic neuroma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(1):37–48. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinarbasi H, Silig Y, Gurelik M. Genetic polymorphisms of GSTs and their association with primary brain tumor incidence. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;156(2):144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R, Wang R, Li Y, et al. Association study on MTHFR polymorphisms and meningioma in northern China. Gene. 2013;516(2):291–293. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiuru A, Lindholm C, Heinävaara S, et al. XRCC1 and XRCC3 variants and risk of glioma and meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2008;88(2):135–142. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9556-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kafadar AM, Yilmaz H, Kafadar D, et al. C677T gene polymorphism of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) in meningiomas and high-grade gliomas. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(3B):2445–2449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang GY, Feng J, Hao SY, et al. Association between DNA repair gene XRCC1 polymorphism and susceptibility to skull base meningioma. J Int Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;42(2):144–147. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang GY, Feng J, Hao SY, et al. Association of XRCC1 Arg194Trp polymorphism with meningioma. Chin J Neurosurg. 2012;4(28):406–410. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elexpuru-Camiruaga J, Buxton N, Kandula V, et al. Susceptibility to astrocytoma and meningioma: influence of allelism at glutathione S-transferase (GSTT1 and GSTM1) and cytochrome P-450 (CYP2D6) loci. Cancer Res. 1995;55(19):4237–4239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egan KM, Baskin R, Nabors LB, et al. Brain tumor risk according to germ-line variation in the MLLT10 locus. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(1):132–134. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobbins SE, Broderick P, Melin B, et al. Common variation at 10p12.31 near MLLT10 influences meningioma risk. Nat Genet. 2011;43(9):825–827. doi: 10.1038/ng.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Roos AJ, Rothman N, Inskip PD, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in GSTM1, -P1, -T1, and CYP2E1 and the risk of adult brain tumors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(1):14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cengiz SL, Acar H, Inan Z, Yavuz S, Baysefer A. Deoxy-ribonucleic acid repair genes XRCC1 and XPD polymorphisms and brain tumor risk. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2008;13(3):227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cacina C, Pence S, Turan S, et al. Analysis of CASP8 D302H gene variants in patients with primary brain tumors. In Vivo. 2015;29(5):601–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bethke L, Webb E, Murray A, et al. Functional polymorphisms in folate metabolism genes influence the risk of meningioma and glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(5):1195–1202. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bethke L, Sullivan K, Webb E, et al. CASP8 D302H and meningioma risk: an analysis of five case-control series. Cancer Lett. 2009;273(2):312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahn JY, Kim NK, Han JH, Kim JK, Joo JY, Lee KS. Genetic mutation of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase in the brain neoplasms. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2002;32(3):183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nazki FH, Sameer AS, Ganaie BA. Folate: metabolism, genes, polymorphisms and the associated diseases. Gene. 2014;533(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santilli F, Davi G, Patrono C. Homocysteine, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, folate status and atherothrombosis: a mechanistic and clinical perspective. Vascul Pharmacol. 2016;78:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, et al. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10(1):111–113. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rozen R. Genetic predisposition to hyperhomocysteinemia: deficiency of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) Thromb Haemost. 1997;78(1):523–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cardona H, Cardona-Maya W, Gomez JG, et al. Relationship between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism and homocysteine levels in women with recurrent pregnancy loss: a nutrigenetic perspective. Nutr Hosp. 2008;23(3):277–282. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Das PM, Singal R. DNA methylation and cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(22):4632–4642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ueland PM, Hustad S, Schneede J, Refsum H, Vollset SE. Biological and clinical implications of the MTHFR C677T polymorphism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22(4):195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duthie SJ, Narayanan S, Brand GM, Pirie L, Grant G. Impact of folate deficiency on DNA stability. J Nutr. 2002;132(8 Suppl):2444S–2449S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2444S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang W, Shi H, Hou Q, Mo Z, Xie X. GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms contribute to renal cell carcinoma risk: evidence from an updated meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17971. doi: 10.1038/srep17971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu XY, Huang XY, Ma J, et al. GSTT1 and GSTM1 polymorphisms predict treatment outcome for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(1):151–162. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji GH, Li M, Cui Y, Wang JF. The relationship of CASP 8 polymorphism and cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-Grand) 2014;60(6):20–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen L, Zhuo D, Chen J, Yuan H. XRCC1 polymorphisms and lung cancer risk in Caucasian populations: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(9):14969–14976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bond J, Bergon A, Durand A, et al. Cryptic XPO1-MLLT10 translocation is associated with HOXA locus deregulation in T-ALL. Blood. 2014;124(19):3023–3025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-567636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martínez C, Molina JA, Alonso-Navarro H, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Agúndez JA, García-Martín E. Two common nonsynonymous paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene polymorphisms and brain astrocytoma and meningioma. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307–314. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gelabert-Gonzalez M, Serramito-Garcia R. Intracranial meningiomas – I: epidemiology, aetiology, pathogenesis and prognostic factors. Rev Neurol. 2011;53(3):165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller R, Jr, DeCandio ML, Dixon-Mah Y, et al. Molecular targets and treatment of meningioma. J Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;1(1):1000101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosking FJ, Feldman D, Bruchim R, et al. Search for inherited susceptibility to radiation-associated meningioma by genomewide SNP linkage disequilibrium mapping. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(6):1049–1054. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang X, Jia H, Lu Y, et al. Exome sequencing on malignant meningiomas identified mutations in neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) and meningioma 1 (MN1) genes. Discov Med. 2014;18(101):301–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]