Abstract

Introduction

Referral rates to specialty care from primary care physicians vary widely. To address this variability, we developed and pilot tested a peer-to-peer coaching program for primary care physicians.

Objectives

To assess the feasibility and acceptability of the coaching program, which gave physicians access to their individual-level referral data, strategies, and a forum to discuss referral decisions.

Methods

The team designed the program using physician input and a synthesis of the literature on the determinants of referral. We conducted a single-arm observational pilot with eight physicians which made up four dyads, and conducted a qualitative evaluation.

Results

Primary reasons for making referrals were clinical uncertainty and patient request. Physicians perceived doctor-to-doctor dialogue enabled mutual learning and a pathway to return joy to the practice of primary care medicine. The program helped physicians become aware of their own referral data, reasons for making referrals, and new strategies to use in their practice. Time constraints caused by large workloads were cited as a barrier both to participating in the pilot and to practicing in ways that optimize referrals. Physicians reported that the program could be sustained and spread if time for mentoring conversations was provided and/or nonfinancial incentives or compensation was offered.

Conclusion

This physician mentoring program aimed at reducing specialty referral rates is feasible and acceptable in primary care settings. Increasing the appropriateness of referrals has the potential to provide patient-centered care, reduce costs for the system, and improve physician satisfaction.

INTRODUCTION

Specialty referral is an important process in health care because it is how patients in primary care generally gain access to specialty care. Referrals to specialty care generally occur for three main reasons: to provide specialty advice and guidance on diagnosis and management; to perform specialized procedures and tests that require advanced technologies or skills; and to provide management reassurance to the patient, family, physician, payer, or other third party.1–3 Research has consistently found that specialist referral rates from primary care vary widely, even after adjusting for patient case mix.4–6

This variability suggests considerable uncertainty about which patients should be referred, to which specialist, when and if transfer of care should occur, and for how long referral relationships should continue.4,7–10 There is little agreement among physicians and patients about the reasons and necessity for many referrals,4 and limited evidence of a relationship between referral rates and patient outcomes, such as self-rated health or avoidable hospitalization.10 High referral rates can lead to costly downstream testing, procedures, and cross-referrals by specialists.

Patient characteristics are important determinants of referral and relate to the nature and complexity of their medical problems (eg, patients with rare conditions are often best managed with specialist advice), as well as their socioeconomic characteristics, attitudes, and expectations for referral.4 There is also some evidence that patients who are satisfied with prior specialty referrals are more likely to be referred again.11 A national survey showed that physicians acquiesce to a patient’s requests for unnecessary referrals.12

Referral has also been shown to relate to many characteristics of the primary care physicians,4,7,12,13 including their medical training paths,10,12,14,15 age and experience in practice,12,13,15,16 sex,17 and workload (eg, overworked physicians are more likely to refer).18 Other research suggests that high- and low-referring physicians differ in their willingness to take risks in the face of clinical uncertainty.4,17,19–21

Innovations such as data audits, feedback, and referral guidelines aimed at better equipping primary care physicians to deal with clinical uncertainty and to respond to patients’ referral requests have been shown to be effective at reducing unnecessary specialty referrals.4,7 However, these innovations are unlikely to be successful without addressing fundamental issues collectively.

To address high rates of specialty referrals and build on effective approaches, a multidisciplinary team, which included family physicians, the Medical Director for the Quality Program at Group Health, a psychologist, and health services researchers, developed and pilot tested a peer-to-peer coaching program. The goal of the program was to reduce unnecessary referrals by providing primary care physicians with their individual-level referral data, an opportunity to reflect and discuss referral decisions with a respected peer, and alternative approaches of providing care to patients without the need for specialty referrals. Our goals for the pilot were to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the program. We describe the program and our learnings from implementing the quality-improvement pilot in primary care.

METHODS

Setting

A single-arm observational pilot study took place at 2 primary care clinics of Group Health, an integrated health care delivery system that serves about 600,000 patients in Washington and Idaho. At the time of the pilot, Group Health did not have explicit guidelines for appropriate referrals. We chose the 2 clinics for convenience because they were proximal to the project team, which enabled face-to-face meetings. We identified peer coaches and participants from August 2014 through December 2014. For the next 3 months we implemented the pilot. Given that the project was used for quality improvement, it was not considered research by Group Health’s institutional review board.

Physician Coach Identification and Recruitment

To identify physician coaches, we used information that the Medical Group had collected in an anonymous survey to its physicians in October 2014. Respondents identified local primary care opinion leaders across the organization: someone they respected or would ask for consultation for a puzzling clinical problem. We reviewed referral rates of opinion leaders who were nominated on the survey multiple times, at least three or more, to look for physicians with low to midrange referral rates (described in the next paragraph) in their clinic. Using the referral rates and the physician survey results, we identified four candidate coaches, two at each clinic. Because Group Health clinics are locally operated and led, we asked the Chiefs of both pilot clinics to confirm whether they thought the coaches were appropriate and available, and to invite them to participate in the pilot. Each of the four invited coaches agreed to participate.

We used a dataset of referrals made by primary care physicians from March 2014 to August 2014 to calculate referral rates. The numerator was the number of referrals made by the primary care physician, and the denominator was the average number of patients in the physician’s panel. We used Diagnostic Cost Group to account for comorbidity differences across physician panels. We calculated referral rates by physician for all specialties, medical specialties (excluding referrals for physical or occupational therapy, massage, and podiatry), and each of the top 10 specialties that received the most referrals at Group Health (eg, complimentary alternative medicine, cardiology, dermatology, orthopedics). The mean all-specialty referral rate across the group practice was 336 referrals per 1000 Diagnostic Cost Group-adjusted enrollees in March 2014 to August 2014. The mean all-specialty rate was 274 referrals (range, 111 to 556) in the first clinic and 232 referrals (range, 120 to 313) in the second clinic where the pilot took place.

Physician Participant Identification and Recruitment

We reviewed all-specialty referral rates and selected approximately five physicians per clinic who had midrange to high referral rates compared with other physicians in their same clinic. Among these physicians, we asked the clinic Chief to invite two physicians to work with a coach in their clinic. Everyone who was invited voluntarily agreed to participate in the pilot.

Coaching Program

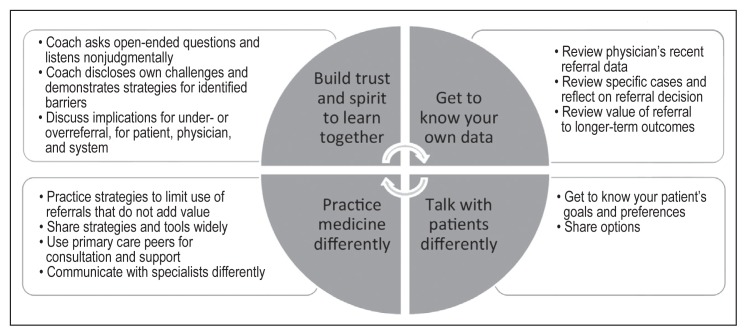

Two physicians (TA and the Medical Director of Quality) and a clinical psychologist (EL) designed a program using a synthesis of the literature on the determinants of referral. They outlined the coaching program with the expectation it would be modified by coaches and partners during the pilot. The project team and coaches met before initiating the pilot. The meeting objectives were to discuss the outline of the program; compile a list of reasons why physicians might be high referring; and share their personal experiences with clinical decision making around specialty referrals, their challenges, and some techniques they found helpful that they might share during coaching. A physician (TA) and the psychologist (EL) held two more interim meetings with the coaches during the intervention. In these meetings, they worked to debrief about their coaching experiences and to document the referral issues that each physician dyad worked on in its weekly meetings. This input was used to adapt the coaching program (Figure 1) as needed during the pilot.

Figure 1.

Physician peer-to-peer coaching program based on four areas of emphasis.

The program focused on four areas. Each coach used various tactics to demonstrate these four areas of emphasis during the coaching sessions.

Build a peer-to-peer coaching relationship. The program provided a safe space and protected time for peer-to-peer dialogue about clinical care, concerns, and reasons underlying referral patterns from the perspective of patients, physicians, specialists, and system, and approaches to better tolerate diagnostic and clinical uncertainty and to deal with logistical barriers. The coach used reflective listening (a communication strategy) to elicit and better understand the participants’ biases, experiences, and how they thought about and made referrals. The coaches also shared their own experiences.

Get to know the referral data. Physician dyads were given just-in-time, patient-level referral data to reflect on and to discuss referral decisions and alternate clinical management strategies about specific patients under their care. Participants and coaches were provided with a list of referrals made from June 2014 through August 2014 by the participant and the coach in the three specialty areas to which the participant referred most often. Physician dyads used these data to select cases for review in the electronic health record and then reflected post hoc on their motivations for making referrals. A key strategy was to question and discuss whether the referrals added value to the patient in the short and intermediate term.

Develop strategies to practice medicine differently. The physician dyads discussed alternative approaches to reduce unnecessary referrals, such as consulting in real time with a primary care peer. The dyads also considered three key questions to facilitate inner dialogue when they were in the moment of discussing and deciding when to make a referral: 1) What is the added value of the referral to the patient? 2) Is this the right time to refer? and 3) What alternatives should physicians consider before making a referral?

Get to know and talk with patients differently. The physician dyads discussed practical techniques to address attitudes and preferences of patients for specialty referral. The coaches urged the participants to pause when discussing and deciding whether it was appropriate to make a referral. Taking a step back, a physician can inquire about the patient’s needs, goals, values, and preferences (eg, whether they want conservative or more interventional treatment as the primary approach). This helps the physician understand how the referral will meet the patients’ goals and gives the physician a context for discussing alternative options. Many physicians can have a phone or virtual consult with a specialist without having to make a complete in-person referral. For example, a physician can take a photo of a skin lesion, then transmit the image to a specialist for a virtual consult. According to specialists’ recommendations in this scenario, referral follow-up would be needed only if the lesion had not resolved.

We anticipated that coaching might be stressful. It was important to integrate support mechanisms for the coaches similar to a study the authors implemented at Group Health, in which they set up mechanisms to support oncology nurse navigators.22 The project team implemented a virtual forum for the coaches, which served as a coach support group for them to ask questions and share techniques via e-mail. The coaches received an honorarium for their time to design and implement the project.

Evaluation

From May 2015 through July 2015, we held individual 20- to 30-minute, semistructured phone interviews with the coaches and participants to gather their perspectives on key program features. Interview questions focused on program experience, results, benefits, challenges, key lessons learned, and perspective on the potential for program scale and spread. The interviews were recorded (with the interviewee’s consent), transcribed, and analyzed using standard thematic analysis. We did not calculate changes in referral rates because our sample size of participants was not large enough to assess change reliably.

RESULTS

Quantitative Results

The 4 coaches graduated from medical school between 1971 and 2000. The 4 participants who met with the coaches graduated from medical school between 1995 and 2004. All physicians were board certified in family medicine. The coaching pilot was successful in engaging physician dyads to have weekly meetings and additional conversations about care and how they assess their patients’ needs. The dyad meetings were approximately 30 minutes and spanned 8 to 10 weeks. The project provided lunch for the dyads during their weekly meetings. Dyads collaboratively set informal agendas, reviewed patient charts and referral data, discussed their goals for the program, and conversed about specific scenarios and alternative approaches to making a referral. The coaches reported that participants’ primary reasons for making referrals were clinical uncertainty and patient request.

Qualitative Results

All four participants described their experience in positive terms, including some who were initially reluctant to participate. Voluntary participation in this pilot laid the groundwork for productive dyad interactions. Coaches tried to establish early on that the program was not about performance management but about learning together to make appropriate referrals. Coaches were instrumental in making the experience friendly and constructive, to “discover together,” as one coach commented. Coaches reported that they gained as much from their interactions as the participants said they did.

Four key themes emerged from the interviews as well as from meetings with the coaches.

Peer-to-peer dialogue relieved workday isolation and was a vehicle to learn from one another. The chance to meet with other clinicians and “compare notes” about how they practice was cited as one of the most positive aspects of the pilot. Doctors spoke openly of the isolating nature of their day-to-day routines and their desire for meaningful interactions with their peers. One participant said, “We don’t talk to other people, there’s really no time in your day; [in the pilot] it was nice being able to discuss cases with a partner, [and] it’s nice to just talk with your colleagues.” Coaches recognized their “support group” was an additional opportunity for dialogue with physician colleagues to discuss cases and approaches. Everyone expressed gratitude for the opportunity to talk with peers about providing clinical care.

Reflection and acquiring new skills improved knowledge and decision-making capacity. The pilot helped both coaches and participants become more aware of their own referral data and different reasons for making referrals, and gave them new approaches and decision-making aids to use in their practice. A participant reported, “the main impact was that I’m thinking more in-depth about how much value this referral adds for this patient at this time. Is this the right time to make a referral?” Participants reported that they learned about communication guidelines to triage referrals efficiently to orthopedics, how to make better use of internal resources (eg, referring patients to primary care physicians with particular expertise rather than to specialists), tangible skills and knowledge in certain clinical areas (diseases of the urinary tract), and new ways of talking to patients about their wants and expectations for care.

Lack of time was a reported barrier. Time constraints caused by physicians’ large workloads were cited as a barrier both to taking part in the pilot and to practicing in ways that optimize referrals. One participant expressed, “The meeting cost me an hour of charting time. That was my major challenge; I had to come in earlier or stay later the next day.” Perhaps more important is that those same constraints may cause unnecessary or premature referrals: “That’s often when you put in a referral, where you don’t have time in the day to do the research you need to do, and if you’re not an expert, you put in the referral.” Delays in getting an appointment with a specialist sometimes instigated setting up referrals “just in case,” almost like saving the patient’s place in line. When the time came, a decision could be made whether to keep or cancel the referral appointment.

There was support for sustainability. Most coaches and participants thought the program should and could be sustained and spread, provided some conditions were met. These included keeping the dyad or having a very small group to enable individual-level conversations, arranging time relief and coverage for participating physicians, and/or offering nonfinancial incentives and/or compensation (eg, providing lunch, a “pay-it-forward” approach in which physicians who experienced the program would serve as coaches to other physicians). The coaches felt there could be potential value of also having specialists consult with the dyads about how to work efficiently and effectively together. A coach suggested that several factors were needed for program success: “First, the coaches meeting several times among themselves; second, an ongoing relationship between the mentor and the mentees; third, that the person being coached is willing and interested and recognizes that it’s not a punitive experience.”

DISCUSSION

Interview data revealed that the pilot fostered learning and gave physicians a rare opportunity for clinical discussions with their peers. The data also suggest direct and indirect effects on referrals by targeting some of the underlying reasons for referrals, including habit and gaps in skill and knowledge.

The pilot demonstrated that a physician mentoring program based on voluntary participation that aimed to reduce specialty referral rates was feasible and acceptable in primary care settings. The essential elements of the program included 1) dedicated time in a setting that was not focused on performance management to converse about clinical care, much like Balint groups23 or the traditional “doctors’ lounge”; 2) catered lunch during these dedicated times; and 3) review and discussion of one’s own cases and referral data, not examples or aggregated clinic data. Physicians perceived doctor-to-doctor dialogue as mutual learning that enhanced confidence and trust and reduced defensiveness, and as a pathway to bring joy back into the practice of primary care medicine. We learned that having clinic leadership support and the trusting relationships that developed during face-to-face, small-group interaction were essential to the pilot’s success.

A larger cohort of physicians and a longer-term program is needed to determine if referral rates are affected by this type of coaching program. Overall, the concept of mentor-guided learning applied to optimizing referrals is promising, although the one-to-one application may be resource intensive. Adjustments to make the program scalable include increasing the coach-to-partner ratio, coaching in a small group format, or conducting the coaching virtually rather than in-person. Involvement of specialists is another potential area to study.

CONCLUSION

Because fee-for-service health care systems generally desire the production of referrals to obtain revenue, interventions to address referral variation in the general US medical community are poorly developed. However, a novel coaching intervention such as the one we developed could have wider applicability in today’s health care environment with the introduction of Accountable Care Organizations that manage the total cost of care. Increasing the appropriateness of referrals has the potential to provide patient-centered care, reduce costs for the system, and enable physicians to practice joy at work by partnering with each other. Expanding this physician coaching program by offering it to more physicians and in more clinics could reap benefits in the future, but only with continued leadership support, evaluation, and adjustment when needed.

Specializing in Diseases

[Egyptians split up] the practice of medicine … into separate parts, each doctor being responsible for the treatment of only one disease. There are, in consequence, innumerable doctors, some specializing in diseases of the eyes, others of the head, others of the teeth, others of the stomach, and so on; while others, again, deal with the sort of troubles which cannot be exactly localized.

— Herodotus, 485 BC – 426 BC, Greek historian

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from Group Health Foundation’s Partnership for Innovation. We would like to thank Rebecca Phillips, MA, who provided administrative support.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Penchansky R, Fox D. Frequency of referral and patient characteristics in group practice. Med Care. 1970 Sep-Oct;8(5):368–85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197009000-00004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-197009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulter A, Noone A, Goldacre M. General practitioners’ referrals to specialist outpatient clinics. I. Why general practitioners refer patients to specialist outpatient clinics. BMJ. 1989 Jul 29;299(6694):304–308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6694.304. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.299.6694.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell CA. Variation in GP referral rates: What can we learn from the literature? Fam Pract. 2000 Dec;17(6):462–71. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.6.462. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/17.6.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohoe MT, Kravitz RL, Wheeler DB, Chandra R, Chen A, Humphries N. Reasons for outpatient referrals from generalists to specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 1999 May;14(5):281–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00324.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roland MO, Bartholomew J, Morrell DC, McDermott A, Paul E. Understanding hospital referral rates: A user’s guide. BMJ. 1990 Jul 14;301(6743):98–102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6743.98. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.301.6743.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett ML, Song Z, Landon BE. Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999–2009. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jan 23;172(2):163–70. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.722. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the baton: Specialty referrals in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011 Mar;89(1):39–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00619.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beasley JW, Starfield B, van Weel C, Rosser WW, Haq CL. Global health and primary care research. J Am Board of Fam Med. 2007 Nov-Dec;20(6):518–26. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.06.070172. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2007.06.070172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan CO, Omar RZ, Ambler G, Majeed A. Case-mix and variation in specialist referrals in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2005 Jul;55(516):529–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franks P, Mooney C, Sorbero M. Physician referral rates: Style without much substance? Med Care. 2000 Aug;38(8):836–46. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00007. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200008000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludke RL. An examination of the factors that influence patient referral decisions. Med Care. 1982 Aug;20(8):782–96. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198208000-00003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaul S, Kirchhoff AC, Morden NE, Vogeli CS, Campbell EG. Physician response to patient request for unnecessary care. Am J Manag Care. 2015 Nov;21(11):823–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vehviläinen AT, Kumpusalo EA, Voutilainen SO, Takala JK. Does the doctors’ professional experience reduce referral rates? Evidence from the Finnish referral study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1996 Mar;14(1):13–20. doi: 10.3109/02813439608997063. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/02813439608997063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherkin DC, Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG, Schneeweiss R, LoGerfo J. The use of medical resources by residency-trained family physicians and general internists. Is there a difference? Med Care. 1987 Jun;25(6):455–69. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198706000-00001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198706000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkin D, Smith A. Explaining variation in general practitioner referrals to hospital. Fam Pract. 1987 Sep;4(3):160–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/4.3.160. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/4.3.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ringberg U, Fleten N, Deraas TS, Hasvold T, Førde O. High referral rates to secondary care by general practitioners in Norway are associated with GPs’ gender and specialist qualifications in family medicine, a study of 4350 consultations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013 Apr 23;13:147. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-147. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franks P, Clancy CM. Referrals of adult patients from primary care: Demographic disparities and their relationship to HMO insurance. J Fam Pract. 1997 Jul;45(1):47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kushnir T, Greenberg D, Madjar N, Hadari I, Yermiahu Y, Bachner YG. Is burnout associated with referral rates among primary care physicians in community clinics? Fam Pract. 2014 Feb;31(1):44–50. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt060. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmt060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grol R, Whitfield M, De Maeseneer J, Mokkink H. Attitudes to risk taking in medical decision making among British, Dutch and Belgian general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1990 Apr;40(333):134–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey J, King N, Newton P. Analysing general practitioners’ referral decisions. II. Applying the analytic framework: Do high and low referrers differ in factors influencing their referral decisions? Fam Pract. 1994 Mar;11(1):9–14. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.1.9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/11.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calman NS, Hyman RB, Licht W. Variability in consultation rates and practitioner level of diagnostic certainty. J Fam Pract. 1992 Jul;35(1):31–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horner K, Ludman EJ, McCorkle R, et al. An oncology nurse navigator program designed to eliminate gaps in early cancer care. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013 Feb;17(1):43–8. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.43-48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1188/12.cjon.a1-a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horder J. The first Balint group. Br J Gen Pract. 2001 Dec;51(473):1038–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]