Abstract

Every biological trait requires both a proximate and evolutionary explanation. The field of vascular biology is focused primarily on proximate mechanisms in health and disease. Comparatively little attention has been given to the evolutionary basis of the cardiovascular system. Here, we employ a comparative approach to review the phylogenetic history of the blood vascular system and endothelium. In addition to drawing on the published literature, we provide primary ultrastructural data related to the lobster, earthworm, amphioxus and hagfish. Existing evidence suggests that the blood vascular system first appeared in an ancestor of the triploblasts over 600 million years ago, as a means to overcome the time-distance constraints of diffusion. The endothelium evolved in an ancestral vertebrate some 540–510 million years ago to optimize flow dynamics and barrier function, and/or to localize immune and coagulation functions. Finally, we emphasize that endothelial heterogeneity evolved as a core feature of the endothelium from the outset, reflecting its role in meeting the diverse needs of body tissues.

INTRODUCTION

Every biological trait requires both a proximate and evolutionary explanation (reviewed in [1]). Proximate explanations (“how”) employ traditional tools, including biochemistry, molecular biology and cell biology to describe the anatomy, physiology and ontogeny of a trait at the level of a modern day organism. Evolutionary explanations (“when and why”) employ a combination of the fossil record, and comparative morphology and DNA sequences to describe the phylogenetic history of a trait and the fitness advantage that the trait provides at the level of a population or species [2].

The field of cardiovascular biology is largely concerned with proximate mechanisms. How does the heart generate force? How do blood vessels form during development? How do blood vessels and their endothelial lining function in health and how do they become dysfunctional in disease? By contrast, little attention is paid to the evolutionary mechanisms of the cardiovascular system. When and why did the cardiovascular system evolve in the first place? Why are certain blood circulatory systems open, while others are closed? Why are some systems lined by endothelium, whereas others have no cell lining? These are important questions because they provide insights into the design constraints, path dependence, trade-offs and selective pressures that underlie human physiology and vulnerability to disease.

The goal of this review is to explore the evolutionary origins of the blood vascular system and endothelium. There is no trace of the cardiovascular system in the fossil record. Molecular phylogenetic analyses have yielded interesting, though limited insights into evolutionarily conserved mechanisms of heart development and tube formation. By contrast, comparative biology provides a rich source of information that can be used to infer and reconstruct the evolutionary history of the cardiovascular system. We will begin with an overview of body plans in extant animals. Next, we will discuss concrete examples (and introduce primary ultrastructural data) from a spectrum of representative species, with a particular emphasis on invertebrates. Finally, we will use these data to draw conclusions about the evolutionary origins of the blood vascular system. A glossary of terms and concepts used in the current review is included in the online Supplement.

BODY PLANS

All animals have evolved to survive and reproduce, and to do so they share common tasks that include the capture, ingestion, absorption and distribution of food/nutrients; the acquisition and distribution of oxygen for cellular respiration; and the excretion of metabolic wastes and undigested materials [3]. Different species use different strategies to achieve these goals. Such strategies diverge most prominently with changes in body size and complexity. However, the number of identifiable themes or body plans (including the structural design of cardiovascular systems) is limited by developmental /genetic constraints and the laws of chemistry and physics. A consideration of these designs provides important insights into the evolutionary history of the blood vascular system and endothelium.

A word on taxonomy

Eukaryotes consist of two kingdoms, the Protozoa and Animalia (Metazoa). For our purposes, Metazoa, which represent multicellular eukaryotes, can be further classified in one of two ways. The first classification employs molecular and/or morphological data to describe the evolutionary relationships among major metazoan lineages. The results, which may be represented in the form of phylogenetic trees (an example is shown in Fig. 1), can be used to infer evolutionary histories. The deep branches on the animal tree of life remain controversial. Although the details of the metazoan phylogenic tree continue to be revised as new evidence emerges, several important themes emerge. The origin of the Metazoa dates back to approximately 770–850 million years. The most primitive living phylum of animals is the Porifera (sponges), followed by Cnidaria (corals and jellyfish) and Ctenophora (comb jellies). Only two germ layers (endoderm and ectoderm) develop in these latter phyla. Hence, they are called diplobastic animals. Between 600 and 700 million years ago, a new body plan emerged that demonstrated bilateral symmetry and a third germ layer (mesoderm). 1 These animals, referred to as triploblasts, gave rise to two separate lineages: the protostomes and deuterostomes.2 The deuterostome lineage gave rise to the chordates (including cephalocordates, urochordates and vertebrates) as well as hemichordates (acorn worms) and echinoderms (e.g., sea urchins and starfish). Protostomes are further divided into two groups: the Ecdysozoans (including the arthropods and nematodes) and the Lophotrochozoans (including the mollusks and annelids).3 As we shall see, these various branch points mark important transitions in the development of vascular systems.

Fig. 1. Metazoan phylogenetic tree.

Adapted and modified from Juliano CE, Swartz SZ, Wessel GM. A conserved germline multipotency program. Development. 2010; 137:4113-26.

A second, simpler classification separates Metazoa into vertebrates (those animals that possess a backbone/vertebral column consisting of bone or cartilage) and invertebrates (those that do not possess such a structure). Vertebrates, which constitute the subphylum Vertebra of the phylum Chordata, comprise only 3% of all living animal species. Invertebrates, which span over 30 phyla, constitute the remainder of metazoan species. Invertebrates are highly paraphyletic4, and thus display an enormous diversity of body plans. By contrast, all vertebrates are derived from a common ancestor, and are thus constructed on a single common body plan.5 Although the invertebrate-vertebrate dichotomy carries little taxonomic meaning, it allows for a distinction between the prototypic vertebrate cardiovascular system and a broad spectrum of vascular phenotypes in invertebrates, many of which arose independently in response to common selective pressures.

Size matters

Larger body size is a major trend in animal evolution. Changes in size mandate changes in structural design. All unicellular and multicellular animals depend on diffusion to supply oxygen and nutrients, and to remove carbon dioxide. Diffusion, while energetically inexpensive, is a very slow process and works only over small distances (diffusion path < 1 mm).6 A change in body size (whether for a single cell or a multicellular organism) disproportionately changes the ratio of surface area to volume. Specifically, as a solid 3-dimensional body enlarges, its surface area increases in proportion to the radius squared (r2), whereas its volume increases more rapidly (r3). At some point, the cell will reach a size where its surface area cannot meet the needs of its volume. Single cells optimize their surface area-to-volume ratio by developing folded surfaces, or a flattened or thread-like shape. Another strategy to increase size is to incorporate many cells into a single organism. Simple multicellular organisms (diplobastic animals and some of the early triploblastic animals, such as flatworms) obtain oxygen by diffusion alone. They do so by minimizing metabolic demands, by assuming a body geometry that maximizes the surface area, by localizing most of their cells at the environment/body interface and/or by pumping external environmental water to their internal surfaces. However, these strategies have inherent design constraints that place an upper limit on body size. To achieve further 3-dimensional increases in size, it is necessary to employ internal transport and exchange systems (i.e., circulatory systems) to provide bulk flow delivery of substances (e.g., gases, nutrients, wastes) to and from each cell in the body.

Circulatory systems

A circulatory system is any system of moving fluids that reduces the functional diffusion distance that nutrients, gases and metabolic waste products must traverse regardless of its embryological origin or its design [3]. Circulatory systems are highly varied. In diploblasts, they involve circulation of seawater into a body cavity that is open to the environment. In triploblasts, however, circulatory fluid is an internal, extracellular, aqueous medium produced by the animal and distributed either through body cavities or through integrated networks of vessels, sinuses and pumping organs. Circulatory fluids can be moved by ciliary function or muscle action. Directional flow is achieved by means of coordinated peristaltic waves of contraction and/or the presence of one-way valves. There are two internal circulatory systems: coelomic and blood vascular. Most triploblastic animals possess both a coelomic circulatory system and a blood vascular system.7

Coelomic circulatory systems

Some small and flat triploblastic animals (e.g., flatworms) have no system of internal fluid support (i.e., they lack a coelom or blood vascular system). They are called acoelomates (Fig. 2). The space between their ectoderm and endoderm tissue layers is filled with a meshwork of mesodermal cells called parenchyma. These creatures obtain all of their oxygen and food by simple diffusion across the skin and gut and throughout the intercellular medium.8 If there are fluid-filled clefts in this meshwork, the animal is termed a pseudocoelomate.9 However, most triploblastic animals have a fluid-filled body cavity between the outer body wall (ectoderm) and the digestive tube (endoderm), termed the coelom. The coelom is lined by mesoderm-derived epithelium (termed mesothelium), with the apical surface of the mesothelial cells facing towards the lumen.10 The cavity is filled with coelomic fluid, which in some cases contains cells (termed coelomocytes). Coelomic cavities have never developed a pumping system. Instead, fluid transport is produced by cilia on the surface of the mesothelial cells, by contraction of mesothelial cells (which have acquired a myoepithelial phenotype, and are thus termed myoepithelial cells), or by contraction of body wall muscle. The coelom is usually subdivided into multiple compartments by septa and mesenteries (Fig. 2).11 In addition to providing convective flow of gases, nutrients and wastes, the appearance of the coelom allowed organs to move freely, rather than being embedded in solid mesoderm tissue. The coelom also provided space for organ development. Functionally, a coelom can absorb shock or provide a hydrostatic skeleton essential for certain types of movement.12 Because they tend to be compartmentalized, coelomic cavities function in the local circulation of fluid. In contrast, blood vascular systems have evolved in the vast majority of coelomates to provide bulk fluid transport throughout the body of segmented animals.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of different circulatory systems.

Blood vascular systems

The blood vascular system consists of blood-filled spaces (vessels, sinuses, hemocoels, and/or pumping organs) within the connective tissue compartment, which is continuous around and between all tissue layers in the body [4]. In invertebrates, the spaces are lined only by matrix. Vertebrates have evolved a secondary cell lining, termed endothelium. Fluid transport is produced by contraction of specialized mesothelial cells (myoepithlial cells) and/or muscular pumps.13 The blood vascular system is used for the transport of substances (e.g., nutrients, oxygen, carbon dioxide), hydraulic force generation (e.g., head-foot protrusion in mollusks and penile erection in vertebrates), regulation of heat (e.g., via countercurrent flow), ultrafiltration (e.g. in the kidney), defense (e.g., through delivery of clotting factors, immune factors/cells) and whole-body integration (e.g., hormonal regulation). Blood vascular systems follow one of two principal designs: open or closed. In keeping with their paraphyletic origins, invertebrates display diverse phenotypes ranging from open to closed systems. In contrast, all vertebrates have a closed cardiovascular system. As we shall discuss, the division between closed and open systems is not always clear-cut.

Open circulatory systems occur in arthropods (e.g., insects and crustaceans) and non-cephalopod mollusks (e.g., clams, snails and slugs). In these animals, the mesoderm forms coelomic cavities during embryogenesis. However, the cavities and their cell lining regress in the adult. Some populations of mesodermal cells reaggregate and form the blood vessels (e.g., the dorsal vessel in insects). The system is considered open because the blood (called hemolymph) empties from a contractile heart and major supply vessels into the body cavity (termed a hemocoel), where it directly bathes the organs. In other words, the hemocoel is bordered not by mesoderm-derived mesothelial cells, but rather by the basal surface of the tissue cells themselves.14 Thus, once blood empties from the lumen of the distributing vessels, there is no distinction between hemolymph and interstitial fluid/extracellular fluid. Hemolymph returns to the heart either through ostia in the ventricle (arthropods) or via the atrium (mollusks).15 Compared with the closed circulation in lower invertebrates (e.g., annelids), the open circulation boasts a more efficient pump. Whereas annelids rely on peristaltic blood vessels to propel blood, animals with an open circulation have evolved true hearts (containing muscle striations and Z-bands), which display automatic and synchronized beating. However, compared with more advanced closed systems (e.g., in cephalopods and vertebrates), open circulatory systems have a larger blood volume and lower flow rates/pressures. Indeed, the velocity and blood pressure drop abruptly once the blood leaves the heart and vessels and enters the hemocoel. As a final point of comparison, open systems provide flow to organs in series, such that tissues lying further downstream of the heart receive less oxygen compared with more proximal organs. By contrast, the capillary networks of closed circulatory systems are arranged in parallel allowing for equal (and regulated) distribution among tissues.

In insects, the open circulation is not responsible for delivering oxygen. Oxygen delivery is carried out by an elaborate, highly branched tracheal system, which facilitates diffusion to each and every cell of the body. As a result, insects have a larger capacity for aerobic metabolism compared with other with open-circulation invertebrates.

Closed circulatory systems occur in a wide variety of invertebrates including annelids, cephalopods (e.g., octopus and squid) and non-vertebrate chordates, as well as in vertebrates. In closed systems, the blood remains inside distinct channels or chambers, where it is physically separated from the intercellular fluid, body cells and coelom.16 Closed systems consist of collecting and distributing vessels, usually with a central meeting site in a propulsive pump. Exchange with the interstitial fluid and body cells takes place in special areas such as capillary beds or plexi, where the walls are thin to optimize diffusion. The closed system of invertebrates consists of a network of spaces in the extracellular matrix between epithelial cells where the coelom contacts coelom (e.g., mesentery or septa) or where coelom contacts endoderm or ectoderm (Fig. 2). Thus, the wall of these vessels consists of basement membranes derived from different kind of epithelia and the vessels are outlined by the basal surfaces of these cells. In some cases (e.g., annelids), blood is propelled by the pumping action of the blood vessels, which in turn is mediated by the contraction of specialized, differentiated coelomic mesothelial cells (myoepithelial cells), or by muscular blood vessels that contract in peristaltic waves.17. In other cases (e.g., in cephalopods), chambered hearts have evolved to promote fluid movement.

In vertebrates, the closed vascular system consists of a series of closed vessels with an endothelial lining, invested with smooth muscle cells or pericytes. Vertebrate blood vessels, while contractile, do not propel blood. Rather, transport is mediated by a central muscular pump. Most vertebrates have a lymphatic system, which collects and recycles interstitial fluid back to the circulation. There are variations on the common vertebrate plan, many of which are related to different requirements of living in water or on land (reviewed in [5, 6]). For example, fish have a single circulatory system, consisting of an undivided heart with a single atrium and single ventricle in series with oxygen-exchanging gills. By contrast, adult birds and mammals have a double circulatory system in which the heart is completely divided into right and left sides, resulting in separation of deoxygenated and oxygenated blood. The circulatory systems of lungfish, amphibians and reptiles demonstrate a broad array of intermediate designs, each of which is characterized by partial separation of the air breathing organ and the systemic circulation, and thus the potential for left-right and right-left shunts.

The idea that cardiovascular systems are either closed or open is an oversimplification [7]. For example, in many mollusks and crustaceans, blood is ejected from the heart into a highly ramified network of branching vessels before emptying into the hemocoel. This is illustrated in the lobster (see section below), and even more prominently in the sea snail, Haliotis, where the abdominal arteries end up in a complex meshwork of small capillary-like vessels [8].18 Moreover, studies in drosophila have shown that blood flows along preferred routes in the open hemocoel despite the absence of discrete return channels [9]. Conversely, the closed system of vertebrates contains vascular beds, such as the sinusoids of the liver, spleen and bone marrow, where there is direct contact between blood and the interstitial space. In hemochorial placentation (e.g., in primates), the maternal spiral arteries become open ended, and blood is released into a placental labyrinth where it bathes the chorionic villi and is drained by the spiral veins. Such an arrangement is highly reminiscent of an open system.

Endothelium

Invertebrate vessels are always lined by extracellular matrix. Only vertebrates possess a true endothelial lining, defined as a layer of epithelial cells expressing basoapical polarity (with the apical surface facing the lumen), intercellular junctions and anchoring to basement membrane. The blood vessels of some invertebrates, including cephalopods, annelids, and amphioxus (discussed next) have cells clinging to the luminal surface, internal to the basement membrane. These cells have sometimes been referred to as “endothelial cells” [10–13]. However, they form an incomplete lining, they lack intercellular junctions typical of vertebrate endothelial cells and they rarely appear attached to the underlying basal lamina. A more appropriate term for this cell type is an amoebocyte. It likely represents a type of circulating hemocyte, which may or not be an evolutionary precursor of the endothelial cell.

Gas exchange

The circulatory system has co-evolved with gas exchange mechanisms. Some invertebrates obtain their oxygen by simple diffusion through the skin. Integumentary gas exchange is characteristic of small soft-bodied animals with high surface:volume ratios. Gas exchange in the majority of marine and many freshwater invertebrates occurs via gills. Terrestrial invertebrates employ specialized invaginated structures, including book lungs (spiders) or trachea (insects). Many invertebrates have metal ion-containing respiratory pigments to increase the oxygen carrying capacity of their blood. For example, hemoglobin is found in many annelids, as well as some crustaceans, insects and mollusks, whereas hemocyanins are the most commonly occurring respiratory pigments in mollusks and arthropods. Respiratory pigments are usually carried in solution in blood, but they are occasionally packaged in blood cells. Vertebrates breathe through their gills, skin and/or lungs. All vertebrates with the exception of Antarctic icefishes (Channichthyidae) have hemoglobin and red blood cells.

CASE STUDIES

In this section, we will consider the blood vascular systems of four different animals: 3 invertebrates and one basal vertebrate. These examples will be used to highlight features of cardiovascular design in the animal kingdom. We begin with an example of an open circulation (lobster). We then turn to three examples of a closed circulation (earthworm, amphioxus and hagfish). The reader is referred to the online Supplement for a description of the methods employed and for additional figures.

Case study 1: The lobster (Homarus americanus)

Lobsters belong to phylum Arthropoda, subphylum Crustacea. Like other arthropods, they have an open circulation (Fig. 3A, Supplemental Fig. I). They have a well-developed single-chambered heart suspended in a pericardial sinus in the dorsal thorax by several pairs of alary ligaments (Fig. 3B). These elastic ligaments are stretched during systole. In diastole, they expand the heart, which results in passive filling with hemolymph from the pericardial sinus through three pairs of muscular valved ostia [14]. The heart is comprised of striated cardiac muscle cells and is conspicuous for its absence of an endocardial lining (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Fig. II). The heart empties into 7 arteries, which then branch multiple times along their length into thin-walled microvessels before emptying into tissue lacunae (i.e., the hemocoel) (Figs. 3A, 3F) [15]. Muscular cardio-arterial valves are present at the origins of all but the dorsal abdominal artery. Blood is collected into a series of interconnected sinuses and passes through either the gills or the branchiostegal sinus before being delivered back to the pericardial sinus surrounding the heart [15].

Fig. 3. Blood vascular system of the lobster.

A, Schematic of the blood vascular system of the lobster. a, artery. B, Open view of the dorsal thorax showing the single-chambered heart suspended in the pericardial sinus by alary ligaments. C, Electron micrograph of the heart showing a cardiomyocyte (cm) filled with cross-sections of thick and thin microfibrils (consistent with myosin and actin) and mitochondria (*). The inner surface of the heart chamber is covered by a thin basal lamina. There is no endocardial lining. A hemocyte (h) is shown in the heart chamber. D, One-micron transverse histological section of a dorsal abdominal artery stained with Giemsa. E, Electron micrograph of the dorsal abdominal artery shows the wall consisting of extracellular matrix composed of a dense meshwork of collagen fibrils. There is no endothelial lining. F, Photomicrograph of a swimmeret of a lobster that has been injected with Evans blue dye in the dorsal abdominal artery. Note the branching network of vessels ending in plumes of extravasated dye in the interstitial space. Panel A is adapted McLaughlin PA. Internal Anatomy. In LH Mantel (Ed.), The biology of crustacea: Internal anatomy and physiological regualtion. New York, NY: Academic Press, 1983.

Arteries leaving the heart are trilaminar vessels consisting of an inner acellular tunic interna, a tunica intermedia which contains fibroblast-like cells, and an outer tunica externa (Fig. 3D, Supplemental Fig. III) [16, 17]. Of the 7 arteries, only the dorsal abdominal artery has occasional muscle fibers in its wall [16, 18]. Electron microscopy reveals the presence of an internal lamina containing microfibrils and a medial lamina composed of a dense network of microfibrils (Fig. 3E, Supplemental Fig. IV) [19]. All invertebrates lack elastin. Nonetheless, lobster arteries demonstrate non-linear elasticity (typical of vertebrate arteries) [16]. This property my be related to the reorientation of the microfibrils within the vessel wall [20].

Previous studies in lobster have demonstrated heart rates of 61–83 beats per minute [16, 21], and systolic pressures of approximately 20 mmHg [16]. Although all but one of the arteries lack muscle, they contract with exposure to cardioactive drugs, suggesting that they are not simply passive supply tubes but rather are used to regulate arterial resistance.[16] Oxygen exchange in lobsters takes place in gills. Oxygen transport is facilitated by the copper-containing respiratory pigment, hemocyanin [22], which is found in solution in the hemolymph. Lobster blood contains hemocytes (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Fig. II). Between 3 and 11 morphologically distinct types of hemocytes have been described [23]. These cells are likely involved in innate immunity and coagulation.

In summary, the lobster has evolved highly efficient cardiovascular and respiratory systems to meet its metabolic requirements. Indeed, the very fact that mollusks and arthropods represent the largest and most diverse phyla in the animal kingdom is testament to the enormous success of the open circulatory design.

Case study 2: The earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris)

The earthworm belongs to the phylum, Annelida. Like most triploblastic animals, the earthworm has a well-developed coelom and a blood vascular system. The coelom is highly compartmentalized, with distinct left and right cavities housed in each body segment. The coelomic fluid provides an important hydrostatic skeleton that enables locomotion.19 The blood vascular system is closed. There is no heart. Rather, circulation is carried out by contractile blood vessels. There are three main longitudinal vessels: the dorsal vessel, the ventral vessel and the subneural vessel (Fig. 4A, Supplemental Fig. V). The largest and most conspicuous vessel in the earthworm is the dorsal vessel, which lies on the dorsal surface of the alimentary tract and traverses the length of the animal (Fig. 4B, Supplemental Fig. VI) [24]. The dorsal vessel collects blood from other vessels and drives it forwards through contractile peristaltic waves that originate at the posterior end of the animal and move forward [24, 25]. Anteriorly the dorsal vessel ceases to be a collecting vessel and gives rise to five pairs of large commissures that connect to the ventral vessel. These commissures contain lateral “hearts” (pseudohearts), whose contractions are asynchronous with those of the dorsal vessel. The ventral vessel, which is suspended in the mesentery beneath the gut, is the main distributing channel, sending blood forwards anterior to the hearts, and posteriorly behind the hearts. The ventral vessel has no peristaltic activity. In each segment the ventral vessel gives rise to segmental vessels and capillaries (Fig. 4C and Supplemental Fig. VII show capillaries in the body wall), through which blood is carried back to the dorsal vessel. Blood also flows posteriorly through the subneural vessel, which lies ventral to the nerve cord.

Fig. 4. Blood vascular system of the earthworm.

A, Schematic of the blood vascular system of the earthworm. In this case, all vessels are colored red since there is no specialized respiratory organ where blood is oxygenated and because there is no central heart that divides vessels into afferent channels (veins) and efferent channels (arteries). B, Transverse histological section through the body of the earthworm shows the dorsal vessel (arrow) on the dorsal side of the gut. The section was stained with H&E. C, One-micron histological section stained with Giemsa shows two small blood vessels in the body wall. Ep, epidermis; mu, circular muscle layer. D, Electron micrograph of a small blood vessel surrounded by a continuous layer of myoepithelial cells. The lumen is filled with hemoglobin particles. E, Higher power electron micrograph shows a blood vessel lined by several myoepithelial cells. The cells are connected by specialized lateral borders. They contain numerous thick myofilaments (arrows) consistent with myosin that are oriented circumferentially around the vessel. A well-formed basal lamina (*) separates the myoepithelial cells from the lumen of the blood vessel. The fact that the hemoglobin particles are retained in the lumen indicates that the basal lamina forms an effective barrier. F, A similar electron micrograph to E, but shows the presence of an amoebocyte in the blood vessel lumen adjacent to the myoepithlial lining. Panel A is adapted from Brusca R.C., Brusca G.J. Invertebrates. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2003.

A previous study in L. terrestris demonstrated a resting dorsal vessel pulse rate of 11 +/− 2.1 beats per minute [24]. The giant earthworm (Glossoscolex giganteus) reaches sizes of 500–600 g (the body weight of a typical earthworm used in our studies is 3–4 g) and may be as long as 120 cm. Frequency of peristalsis in the dorsal vessel of the giant earthworm was measured as 8 per minute, with an average systolic and diastolic pressure of 24 and 14 cm H2O, respectively, in resting healthy specimens [25]. Pressures in the ventral vessel in response to lateral heart contractions can exceed 100 cm Hg [25]. There is evidence that blood flow is physiologically regulated in annelids. For example, dorsal vessel pulse rates are increased in L. terrestris after forced exercise [24]. Moreover, the load or degree of filling of the dorsal vessel determines the frequency as well as the force of contraction of the peristaltic waves [24, 25]. Finally, a previous study in L. variegatus demonstrated a role for biogenic amines in regulating the dorsal vessel pulse rate [26].

In electron microscopy, blood vessels are readily identified by the presence of electron-dense hemoglobin particles within the lumen (Fig. 4D, Supplemental Fig. VIII). The vessels are outlined by the basal lamina/basement membrane of mesodermal cells, mesodermal and endodermal cells (of the gut), or mesodermal and ectodermal cells (of the skin). The thickness of this extracellular layer (basement membrane) varies across the vascular tree [27]. Mesodermal cells have varying numbers of microfilaments (Fig. 4E, Supplemental Fig. IX) [27, 28]. Microfilament-rich mesodermal cells (myoepithelial cells) are presumed to have a contractile function. Scattered amoebocytes are found on the inner surface of the lumen (Fig. 4F, Supplemental Fig. X) (these cells can also be seen on one-micron Giemsa-stained sections of blood vessels, as shown in Supplemental Fig. XI) [27].20 The amoebocytes contain electron-dense granules and vesicles [27]. In tracer experiments in which colloidal gold or horseradish peroxidase was injected into the blood vessels, most of the vesicles in the amoebocytes were filled with tracer, suggesting that they are endosomes [27]. Amoebocytes are distinct from endothelial cells. They do not appear to be firmly attached to the basement membrane. They cover only a small fraction of the surface of the blood vessel. There is no evidence for junctional complexes between neighboring cells. Finally, the large number of dense granules is atypical for endothelial cells. In summary, blood vessels of the earthworm are lined by basement membrane and lack an endothelial layer.

Earthworms have no specialized respiratory organs.21 Rather, gas exchange takes place across the general body surface. The earthworm has an extensive intradermal capillary network, which provides a high surface area for such exchange. The blood contains a high molecular weight (3.6 MDa) hemoglobin dissolved in the plasma [29, 30].22 The oxygen content in blood samples from the dorsal vessel of giant earthworms has been reported to be between 0.7 and 9.8% [31].

In summary, the earthworm provides an example of an invertebrate with a closed blood circulatory system. Unlike its vertebrate counterpart, the closed circulation of annelids lacks a true heart and consists of blood vessels that are delimited by the basal surface of epithelial cells, some of which exhibit a contractile function.

Case study 3: Amphioxus (Branchiostoma lanceolatum)

Amphioxus belongs to the phylum Chordata, subphylum Cephalochordata, which is the most basal subphylum of the chordates [32, 33].23 They have extensive coelomic cavities and a closed circulation. The blood does not contain circulating cells or hemoglobin (or any other respiratory pigment). As a result, the blood vessels are not readily identifiable. However, previous tracer studies have yielded a roadmap of the circulatory system in amphioxus (Fig. 5A, Supplemental Fig. XII) [12, 34, 35]. Amphioxus do not have a heart. Instead, circulation is accomplished by contractile vessels, including the endostylar artery, subintestinal vein and hepatic vein. As in vertebrates, blood moves forward ventrally and backwards dorsally. The endostylar artery (also called the ventral aorta) is ventral and carries blood in a cranial direction. The endostylar artery sends vessels to the gills, which comprise more than 80 pairs of gill slits with adjacent slits separated by gill bars (Fig. 5B, Supplemental Figs. XIII–XV) [36]. The gills are used for filter feeding, not for oxygen exchange [37]. The gill bars are of two types: primary and secondary. The primary gill bars have three longitudinal vessels: the visceral, the skeletal and the coelomic. The secondary only have two such vessels: the visceral, and skeletal. Blood from the gills moves to the dorsal aorta. In the anterior region of the pharynx, the dorsal aorta is paired and lies immediately under the notochord. It is fused posteriorly. The dorsal aorta sends branches (segmental dorsal and ventral arteries) to supply the myomeres. It also sends short mesenteric arteries, which open directly into the plexus of vessels surrounding the intestine [34]. Blood in the intestinal plexus is drained into the subintestinal vein followed in turn by the afferent liver vessel, the liver plexus and the efferent liver vessel (also called the hepatic vein). The hepatic vein runs caudally along the dorsal surface of the liver (a simple blind diverticulum of the intestine) to ultimately join the common cardinal vein at the sinus venosus to form the endostylar artery (Supplemental Figs. XV–XVI). Previous tracer studies have shown that the various afferent and efferent vessels of amphioxus are connected by extensive plexi of tiny vessels [34].

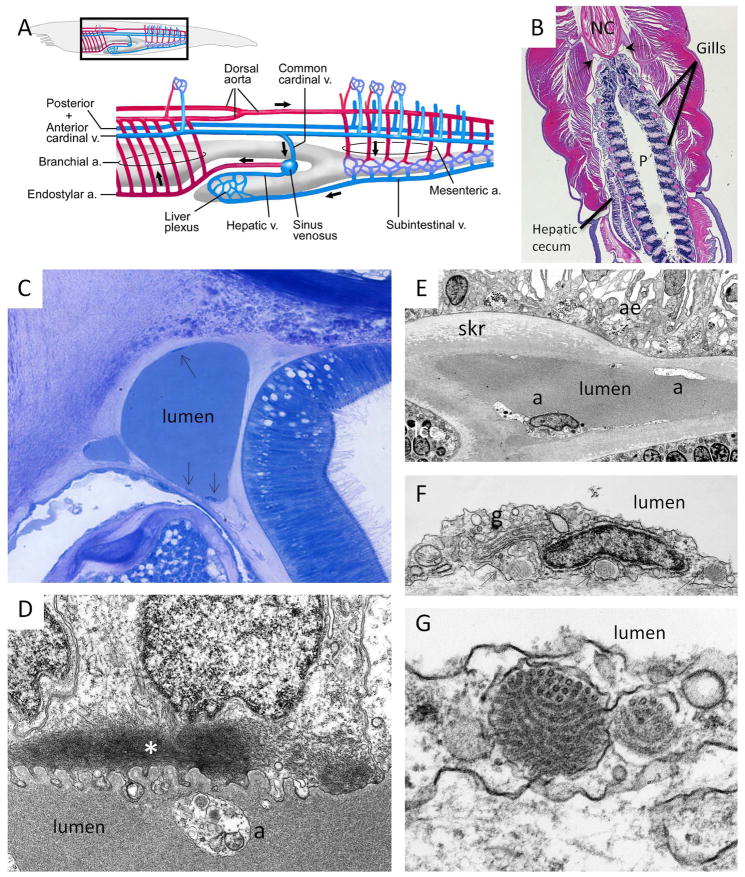

Fig. 5. Blood vascular system of amphioxus.

A, Schematic of the blood vascular system of amphioxus. B, Transverse histological section through the pharynx shows the paired dorsal aortae (arrows) lying on either side of and ventral to the notochord (NC). The hepatic vein is on the dorsal surface of the liver (also referred to as the hepatic cecum). The section was stained with H&E. P, pharynx. C, One-micron histological section stained with Giemsa shows a discontinuous coverage of dorsal aorta with amoebocytes (arrows). D, Electron micrograph of the contractile hepatic vein shows the lumen delimited by parts of three myoepithelial cells, which contain myofilaments (*) in their basal portion. a, amoebocyte. E, Electron micrograph of a skeletal vessel in the gill surrounded by skeletal rod (skr). The skeletal rod, in turn is surrounded by atrial epithelial cells (ae) and lateral ciliated cells (lcc). Occasional chromaffin-like cells (with membrane-delimited electron dense granules) are scattered between the atrial epithelial cells. Note the presence of amoebocytes (a) on the luminal surface of the blood vessel wall. F, Electron micrograph shows an amoebocyte “clinging” to the luminal surface of the dorsal aorta. The cell contains a well-developed Golgi apparatus (g), numerous vesicles, and granules containing tubular structures (arrows). Note that the amoebocyte has no underling basal lamina. Rather it is applied to the connective tissue matrix. G, Higher magnification of an amoebocyte from dorsal aorta shows two tubule-filled granules.

Blood vessels in amphioxus are not lined by endothelium, but rather by the basal surfaces of epithelial cells and extracellular matrix. For example, the dorsal aorta is delimited by the basal surface of coelomic cells and by connective tissue around the sheath of the notochord and the hyperpharyngeal groove (Figs. 5B–5C, Supplemental Figs. XVII). Blood vessels in the gills are lined by varying types of epithelial cells, including coelomic cells, atrial cells, lateral ciliated cells, lateral pharyngeal cells and medial pharyngeal cells. In the gut, the blood vessel lumen forms between the basal surfaces of coelomic cells and intestinal epithelial cells. A previous tracer study demonstrated that the basal lamina in the visceral vessel of the gill is more permeable to horseradish peroxidase compared with endostylar artery [13], suggesting vascular bed-specific differences in permeability properties.

In contractile vessels (e.g., the hepatic vein and endostylar artery), the surrounding mesoderm consists of myoepithelial cells. These cells contain contractile filaments in the basal part, next to the basal lamina [12]. Many filaments end in patches of higher density (Fig. 5D, Supplemental Fig. XVIII). Isolated masses of connective tissue are distributed around the luminal margin of the hepatic vein near attachment of the vein to the cecum. These finger-like extensions gain entrance into the lumen and form a web-like supporting structure for the vessel wall [12].

As in the earthworm, scattered amoebocytes are found clinging to the inner surfaces of amphioxus blood vessels (Figs. 5E–5F, Supplemental Figs. XIX–XX). These cells, which are rounded or flattened, are rarely in contact with one another and when they are, there are no junctional specializations. The cells contain a well-formed Golgi apparatus. They are packed with polyribosomes and rough endoplasmic reticulum. They also possess many vesicles. In previous tracer studies, ferritin and horseradish peroxidase were taken up by coated and smooth surfaced vesicles within the amoebocytes, suggesting that these latter cells possess endocytotic capability [13]. The most conspicuous finding (which is not observed in the earthworm amoebocyte) is the presence of tubules in membrane-bound organelles (granules), which occur at varying orientations (Figs 5G, Supplemental Fig. XXI). The size of the tubules appears larger than what is observed in Weibel-Palade bodies and microtubules in the cytoskeleton. It has been proposed that these tubules are precursors of cytoplasmic microtubules involved in cell motility, and that the amoebocytes function by “policing” the luminal surface of the boundary layer, removing residues of filtration and facilitating exchange of material between blood and surrounding tissues [12]. Others have suggested that these cells are responsible for depositing and/or clearing the lumen of extracellular matrix as blood vessels develop in the amphioxus larvae [38, 39].

In summary, despite its close evolutionary relationship with vertebrates, amphioxus seem to possess a relatively “primitive” closed circulatory system, conspicuous for its absence of a central heart and endothelial lining, as well as lack of circulating blood cells and respiratory pigment.

Hagfish (Myxine glutinosa)

Modern vertebrates are classified into two major groups: the gnathostomes (jawed vertebrates) and the agnathans (jawless vertebrates). The agnathans are further classified into two groups, myxinoids (hagfish) and petromyzonids (lamprey). Most evidence suggests that the hagfish diverged before lamprey and is thus the oldest living vertebrate. Shared traits in hagfish and jawed vertebrates indicate that the trait was present in the common ancestor of all craniates.

Hagfish have a closed circulation (Fig. 6A, Supplemental Fig. XXII). Similar to the case in other fishes, the branchial (i.e., gill) circulation is found in series with the systemic circulation. The gills are unique among vertebrates in that they are internalized and organized as pouches, typically 6 on each side in M. glutinosa (Fig. 6B). The hagfish circulation also possesses a series of blood sinuses, which are in direct communication with systemic vessels [40]. The most prominent of these is the large subcutaneous vascular sinus located between skeletal muscles and the skin, stretching from the tentacles of the snout to the caudal fin fold. Hagfish can hold up to 30% of their blood volume within the sinus system [40]. It is believed that the caudal and cardinal “hearts” (composed of skeletal muscle) function to reintroduce sinus blood into the systemic circulation. The hagfish heart exhibits a Frank-Starling mechanism [41]. Thus, blood that is redistributed from sinus to central compartments may serve to increase preload and cardiac output.

Fig. 6. Blood vascular system of the hagfish.

A, Schematic of the blood vascular system of hagfish. Top, Transverse section through mid-region shows several features that are typical of other vertebrates, including the arrangement of myomeres, neural tube, and aorta. Features that are unique to hagfish include the large subcutaneous sinus between skin and skeletal muscle, the retention of the notochord in the adult, and the presence of slime glands on the ventrolateral surface. Bottom, schematic of hagfish circulation. The gills are in series with the systemic circulation. Blood enters the subcutaneous sinus via skeletal muscle capillaries and renters the systemic circulation via accessory hearts (the caudal and cardinal hearts). The portal heart pumps blood from the intestinal vasculature into the systemic heart via the common portal vein. B, Photomicrograph of ventral aorta and two (of a total of 12) gills in an animal that has been injected with Evans blue dye through the heart. C, Electron micrograph of the heart shows electron-lucent endothelial cells (EC) overlying a thick extracellular matrix containing a chromaffin-like cell, and a cardiomyocyte (cm) with electron-lucent cytoplasm, and well-preserved mitochondria and muscle filaments. D, Electron micrograph of the dermis shows a microvessel in cross-section containing two nucleated red blood cells. The blood vessel is lined by a continuous layer of endothelial cells. A melanocyte is seen on the left side of the vessel. E, Electron micrograph of a kidney glomerulus shows podocyte foot processes abutting a well formed basal lamina. On the other side of the basal lamina is an endothelial cell (EC) facing the lumen of a glomerular capillary. The endothelial cell contains many vesicles, vacuoles and tubular structures. F, Electron micrograph of a liver sinusoid shows a large gap in a single endothelial cell (E1, double-headed arrow), well-preserved attachments between two endothelial cells (EC1 and EC2), and a continuum of proteinaceous material from the lumen to extravascular space (Space of Disse). EC2 is a second endothelial cell. Panel A is reprinted with permission from Cheruvu PK, Gale D, Dvorak AM, Haig D, Aird WC. Hagfish: a model for early endothelium. In W Aird (Ed.), Endothelial Biomedcine. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Panels C, D and F are reprinted with permission from Yano K, Gale D, Massberg S, Cheruvu PK, Monahan-Earley R, Morgan ES, Haig D, von Andrian UH, Dvorak AM, Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity is an evolutionarily conserved feature of the endothelium. Blood. 2007;109:613-5.

Hagfish maintain the lowest arterial blood pressures (dorsal aorta blood pressure 5.8–9.8 mm Hg) and highest relative blood volumes (18%) of any vertebrate [42–44]. Cardiac output in M. glutinosa is 8–9 mL min−1 kg−1 [45], which approaches the values seen in some teleosts. Similar to other fish, hagfish have a double-chambered heart containing a single atrium and a single ventricle. The heart consists of an avascular mesh of muscle cells (a so-called spongy heart). There is no coronary circulation. Rather, deoxygenated blood in the ventricle circulates through spaces (sinusoidal channels or lacunae) in the myocardial wall. Unlike other vertebrates, the hagfish heart lacks cardioregulatory nerves. The heart rate ranges from 20–30 beats per minute [45]. Hagfish possess a second cardiomyocyte-containing chambered heart, the portal heart, which beats asynchronously with the systemic heart, as it propels blood from the gut to the liver via the common portal vein [45].

We and others have previously shown that hagfish blood vessels are lined by a single layer of endothelial cells [46–48]. All endothelial cells have vesicles along both the blood and tissue fronts of the cell. The lateral borders of endothelial cells are typical for those seen in mammals. Occasional Weibel-Palade bodies are observed, suggesting that hagfish express von Willebrand factor. Similar to other vertebrates, endothelial phenotypes vary from one vascular bed to another. For example, endothelial cells lining the heart sinuses are attenuated, electron lucent, and contain many vesicular structures (Fig. 6C, Supplemental Fig. XXIII). Dermal microvessels display a continuous endothelium, with lateral plasma membrane borders containing specializations typical of other vertebrates (Fig. 6D, Supplemental Fig. XXIV). The kidney glomerulus contains endothelial cells with few fenestrae, and many vesicle and vacuoles of varying sizes (Fig. 6E, Supplemental Fig. XXV). As a final example, ultrastructural studies of the liver demonstrate a discontinuous endothelium with many gaps (Fig. 6F, Supplemental Fig. XXVI).

In addition to vascular bed-specific differences in ultrastructure, the endothelium of hagfish also demonstrates molecular and functional heterogeneity. For example, lectin staining of various tissues revealed significant differences in lectin binding to the endothelium [46]. Moreover, in intravital microscopy studies of the dermal microvasculature, histamine was shown to induce neutrophil adhesion in capillaries and postcapillary venules, but not arterioles [46]. As a final example, arteries from the mesentery and skeletal muscle demonstrated site-specific mechanisms of endothelium-dependent vasomotor relaxation [49].

In summary, our findings in hagfish confirm that the closed system of even the most basal vertebrate is lined by endothelium and that phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium is a conserved property of this cell type.

EVLOTUTIONARY IMPLICATIONS

When approaching the evolutionary origins of the blood vascular system and the endothelium, we must consider three important questions. First, when did these systems evolve? Second, why did they evolve? In other words, what survival advantage do these structures confer at the level of species? Finally, how did the blood vessels and their endothelial linings develop ontogenetically (as evolutionary novelties) in the first place? In this section, we will consider each question in turn.

When did the blood vascular system and endothelium first evolve?

As we survey the present landscape of body plans, we find a wide variety of blood vascular systems (Fig. 7). Some are closed, others are open. Some use hearts to propel blood, whereas others employ pulsatile blood vessels. Only a minority are lined by endothelium. When and how did all of these diverse structures evolve? The answer is likely through a combination of homology and convergence.24 The last common ancestor of vertebrates and annelids, or of vertebrates and mollusks was the ancestor of the protostome-deuterostome ancestor, which lived between 600 and 700 million years ago [50]. Although the fossil record is scarce, it is widely believed that this precursor animal was a segmented bilaterian (triploblastic coelomate) [7]. If we are to accept that the blood vascular system evolved as a means to bypass the bulkheads of a segmented animal (see next section), then the first such system likely arose during this time. Flow would have been mediated by peristaltic vessels, perhaps like those described in the annelid. Blood probably percolated through spaces in the extracellular matrix, and thus the system was by definition closed, albeit primitive. This scenario supports homology of all blood vascular systems. Over the past 600–700 million years of evolution, the blood vascular system has undergone significant modifications, in response to selective pressures experienced by individual phyla. In some cases, the blood vascular system has regressed (e.g., in flatworms and nematodes). In other cases, the primitive system transitioned to an open circulation. The open system reverted back to a closed design in an ancestral cephalopod. This is an example of convergent evolution, whereby an analogous structure (the closed circulation in cephalopods) arose independently of the closed circulation in other invertebrates (e.g., worms) and in vertebrates. Finally, the endothelium is present in all vertebrates, yet distinctly absent in invertebrates. Although cells appear to cling to the inner surface of some invertebrate closed vessels, these lack the classical morphological features of endothelial cells. Therefore, the endothelium appeared in an ancestral vertebrate following the divergence from the urochordates and cephalochordates between 540 and 510 million years ago. Our findings in hagfish indicate that endothelial heterogeneity appeared during the same narrow window of time [46].

Fig. 7. Phylogenetic perspective of the blood vascular system.

Blood vascular system types and major propulsive organs are shown for representative extant phyla. The phylogenetic tree is schematic only, and the timelines are not drawn to scale. EC, endothelial cell; mya, mullion years ago.

Why did the blood vascular system and endothelium evolve?

Circulatory systems most certainly evolved to overcome the time and distance constraints of diffusion, thus permitting increased body size and metabolic rates, as well as increased levels of integration and organization in Metazoa. Although the primitive coelom provided bulk flow delivery of substances, these structures never developed an efficient pumping mechanism. More importantly, they became increasingly localized to distinct compartments in the body. Ruppert and Carle hypothesized that the blood vascular system evolved as a means to provide bulk fluid transport along the entire length of a segmented animal, in effect bypassing the septal bulkheads [4]. The earliest design may have involved the formation of spaces in between the basal laminae of endodermal and coelomic epithelia, allowing for improved distribution of nutrients absorbed by the intestine [51]. Myoepithelial differentiation of the visceral layer of coelomic epithelium would have provided the necessary pumping action to drive nutrients towards the viscera [52]. Subsequent vascularization of the skin would have facilitated gas exchange at the body surface.

The movement of fluid in blood vascular systems was originally mediated by the peristaltic motion of certain blood vessels, similar to what occurs in the earthworm and amphioxus. However, peristaltic pumps lack effective coordination between the fluid that is entering the contractile region and the fluid that is leaving it. Despite some tweaks to the peristaltic design, such as the evolution of one-way valves and partial coordination in contractions, the loss of fluid energy associated with backflow, distension of wall segments ahead of the stream, and pump reversals would have constrained body size and metabolic activity [53]. This would have provided a selective pressure for the appearance of true hearts, in which inflow and outflow are tightly coupled via multiple chambers, efficient electrical connection between myocytes (hence, simultaneous contraction) and one-way valves [53].

If the closed circulatory system was the ancestral condition, then why did the open circulatory system evolve in the precursors of mollusks and arthropods? One explanation for this change in the circulatory blueprint is that the rigid exoskeleton of these animals, which evolved for protection against predation and physical injury, eliminated the need for a coelomic hydrostatic skeleton [4]. The subsequent regression of the coelom removed barriers to bulk transport and therefore the need for a closed system of vessels. At the same time, the exoskeleton impaired any contribution of body wall musculature to the movement of blood. This may have provided selective pressure for the evolution of a well-developed muscular heart, which is a characteristic feature of most animals with an open circulation.25

Cephalopods are monophyletic with other mollusks, yet they have secondarily evolved a closed circulation. Moreover, they have a far more efficient heart compared with other members of the phylum [8, 52].26 It seems likely that these modifications were selected for to enable an active lifestyle, which includes predatory behavior, swimming and jet propulsion. The same association between closed circulatory system, highly efficient hearts and active lifestyles is seen in the vertebrates. There are several reasons why a closed system might better serve the needs of a highly active animal. First, it provides for a more efficient (i.e., fractal-like) distribution system, which can be tailored to the unique architecture of the various tissues and organs.27 Second, closed circulatory systems can be subject to regulation so that flow is directed preferentially to one organ or another. Third, the closed system enables carriers to remain inside the vessels and release their cargo where needed. This allows for homeostatic integration of diverse tissues in the body. Finally, as alluded to earlier, the closed system provides for parallel flow (equal opportunity) to all organs of the body.

The transition from aquatic to terrestrial life required modifications of several body systems, including those involved with respiration, feeding, locomotion, water balance, and reproduction. The formation of invaginated gas exchangers (i.e., lungs) reflected the need to minimize water loss across the respiratory surface [6].28 Ancillary skin breathing (i.e., cutaneous gas exchange) was possible so long as the epidermis was highly vascularized and thin. Animals with thin skin have high evaporative loss. Therefore, skin breathing is confined to aquatic or semi-aquatic tetrapods, particularly amphibians. Reptiles, which evolved thick impermeable skin to prevent water loss and provide physical protection, were the first vertebrates to rely entirely on lungs for gas exchange. A limitation of the single circulation in fish is that gills receive a greater pressure head than the systemic circulation. As higher pressures evolved in response to increased metabolic demands and gravitation, there was a need to depressurize the gas exchanger. This was accomplished by the separation of systemic and pulmonary circulations.

In water, buoyancy provides virtual weightlessness, whereas on land, animals are subjected to gravitational force. Since the density of water and blood are similar, gradients of hydrostatic pressure in vertical blood columns are counter-balanced by pressure gradients in surrounding water [54]. Thus, transmural pressure throughout the vasculature of aquatic animals remains relatively constant. In contrast, on land, gravity causes increased pressure in the lower part of a fluid column, resulting in increased transmural pressure, pooling of blood in dependent vasculature, reduced venous return and decreased arterial pressures. This effect is particularly important in tall animals or in animals with postural behavior (e.g., arboreal or climbing snakes). Countermeasures to gravitational stress have evolved in tetrapods, including higher arterial pressure, baroreceptor reflex, and low compliance tissues (e.g., stiff skin) [54].

What selective forces were responsible for the appearance of the endothelium in the ancestral vertebrate? One suggestion is that that the smooth lining provided by the endothelium minimizes energy required to move blood.29 The endothelium mediates vasomotor control in the earliest extant vertebrate. Thus, the appearance of the endothelium may have provided a critical new layer of vasoregulation, allowing for more highly pressurized systems. Also, the barrier function provided by the endothelium would have prevented the loss of plasma proteins necessary to maintain equilibrium between osmotic and hydrostatic pressures [4]. Higher pressures required not only higher osmotic pressures, but also the formation of the lymphatic system to drain net surplus of interstitial fluid. The ancestral vertebrate also evolved novel immune and coagulation mechanisms. Thus, the co-evolution of the endothelium during this narrow window of time may be explained in part by the role of endothelial cells in localizing these activities to areas of need [55]. Endothelial cells have been shown to play a pivotal role in the early development of organs, such as the pancreas and liver [56]. Such bidirectional dialogue between the endothelium and other tissues may have been instrumental in shaping the evolution of this cell layer.

The fitness advantage of endothelial cell heterogeneity may be explained on several levels [57]. First, phenotypic heterogeneity reflects the remarkably pleiotropic role of the endothelium in meeting the varying needs of diverse tissue types. Second, some site-specific properties reflect a local self-preserving adaptation of the endothelial cells to their particular microenvironment. Third, phenotypic plasticity provides the endothelium with flexibility to temporally adjust to a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological influences, including pathogens and toxins.

How did the blood vascular system and endothelium evolve?

The coelomic and blood vascular systems (as well as excretory systems) arose within the mesoderm of triploblastic animals. Indeed, the appearance of the mesoderm provided new building material for animal construction and allowed for the evolution of increasingly complex and large animals. At some early evolutionary stage, perhaps in the ancestral triploblastic bilaterian condition, a subpopulation of mesodermal cells differentiated into a mesothelium whose apical side faced the coelom and whose basal side faced clefts (i.e., blood vessels) between the mesothelial walls [58]. Some of these mesothelial cells acquired myofilaments and the capacity to contract [55, 58]. If the earliest blood vessels formed between these myoepithelial cells and gut epithelial cells, then there must have been an intimate coordination between mesodermal and endodermal lineages. In vertebrates, the mesothelium no longer contributes to the vasculature. Instead, endothelial cells are derived from distinct mesodermal zones arising from the primitive streak, including the lateral plate mesoderm, cardiac mesoderm and paraxial mesoderm. Other components of the vascular wall, including smooth muscle cells, are derived from mesoderm or the neural crest (an ectoderm derivative found exclusively in vertebrates). Thus, at some point following the divergence of the cephalocordates, the mesoderm of the ancestral vertebrate acquired novel specialization, which allowed for the formation of endothelium.

There is an interesting body of literature debating the degree to which the drosophila and vertebrate hearts are homologous [53, 58–60]. An important concept is that homology can apply to different levels of organization (e.g., genetic, molecular, cellular, tissue structure, function) [3, 53].30 For example, the drosophila and vertebrate hearts are hardly homologous in three-dimensional structure (at least in the adult stages). However, the drosophila and vertebrates share orthologous genes involved in making a heart, including tinman/Nkx2-5. Indeed, it has been argued that the homologies lie at the level of gene regulatory pathways that make a muscle cell rather than at the level of the organ (i.e., the three dimensional pump) [53]. It has been proposed that the heart evolved through modification and expansion of an ancestral network of regulatory genes encoding a core set of cardiac transcription factors, including NK2, myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2), GATA, Tbx and Hand, virtually all of which are present in triploblasts [39, 61]. The ancestral circuit was probably responsible for the contractile mesothelial cell that lined the earliest blood vessels and ultimately acquired a contractile phenotype to propel the blood. Complexity of the heart increased during evolution owing to the expansion of the number of ancestral regulatory genes, modification of the timing and pattern of their expression, as well as their regulatory interactions with each other and with other regulatory inputs.

What is the origin of the endothelial cell? One possibility is that it arose from the mesothelial cell. Alternatively, endothelial cells are derived from amoebocytes, through the acquisition of an epithelial phenotype [55, 62]. A previous study demonstrated that amoebocytes in amphioxus larvae express Pdvegfr (a single member of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor [PDGFR]/ vascular endothelial growth factor receptor [VEGFR] subfamily) [39]. The authors proposed that vertebrate endothelial cells may have derived from ancestral free hemal Pdvegfr+ cells [39]. Consistent with an amoebocyte origin of endothelial cells is the observation that endothelial cells arise in close association with hematopoietic cells. For example, they share a common progenitor cell (the hemangioblast) and some hematopoietic cells are derived from hemogenic endothelium. It also noteworthy that hemocytes in Drosophila express VEGFR [63].

As in the case of the heart, the endothelium likely arose through the mutation and selection of a small number of pre-existing regulatory genes involved in mesoderm function. It is, of course, highly improbable that selection has coordinated hundreds of different DNA mutations to yield such a broad array of endothelial cell phenotypes [57]. Instead, the endothelium has been selected for its plasticity and exploratory behavior [64]. As a result, organs can acquire changes without depending on co-evolution in the endothelium.

The ancestral vertebrate developed the means to assemble endothelial cells into tubes, to recruit pericytes and stabilize blood vessels, and to specify different subtypes of vessels, including arteries and veins. The extent to which the processes “borrowed” from established building plans is unclear. It is notable that VEGF-like factors have been identified in a number of invertebrates, including drosophila [63], and squid [65]. Moreover, a blueprint for tubulogenesis exists in multiple systems, including the tracheal system of insects [66, 67]. The formation of blood vessels in the closed circulatory system of invertebrates has been referred to as “myoepithelial angiogenesis” [51]. The process may involve hemocyte-mediated clearance of extracellular matrix to form a patent lumen [38, 62], or the separation of apposing mesothelial basement membranes, perhaps via cell-cell repulsion [62]. Studies in Drosophila have implicated a role for Robo-Slit in heart tube formation [62].

EVOLUTIONARY MEDICINE

In the Introduction, we emphasized the importance of both proximate and evolutionary explanations when approaching human physiology and pathophysiology. Evolutionary medicine is the application of evolutionary principles to an understanding of human health and disease [1, 68, 69]. Evolutionary biology teaches us that no trait is perfect. Every trait can be made better, but by making it better something else would be made worse. Indeed, a central tenet of evolutionary medicine is that the human body is a jerry-rigged bundle of trade-offs and that an understanding of the cost-benefits of these trade-offs will provide novel insights into our vulnerability to disease. For example, consider the closed circulatory system. Such a design permits more efficient bulk flow delivery to the tissues of the body. However, a closed vasculature is by definition branched and curved. Blood flow is disturbed at branch points and curvatures. Microdomains of flow disturbance render the endothelium dysfunctional and vulnerable to atherosclerosis. This is a classic example of an evolutionary tradeoff, where the advantages of closing the circulation are balanced against the disadvantage of increased susceptibility to atherosclerotic lesion formation. Another important evolutionary principle when considering human health and disease is the notion that the present-day blood vascular system evolved to maximize fitness in a far earlier era, perhaps tens of thousands of years ago, which is the time it takes for natural selection to filter the gene pool. Our evolved state has not had time to adapt to changes in longevity, physical activity, diet and recreational drug use (especially smoking). The resulting gene-environment mismatch has led to an epidemic of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and atherosclerosis. A goal of preventive medicine is to recalibrate the balance by adapting the environment to the genetic blueprint.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians and clinician-scientists tend to view the cardiovascular system through the narrow lens of proximate causation. In this review, we have attempted to place the blood vascular system in a broader temporal context, with the goal of emphasizing the selection pressures that have led to its emergence. An important take home message is that cardiovascular systems are highly diverse in their structure and function. The design of a given system is exquisitely matched to the needs of the animal. It is not helpful to think of one system being “superior” to another. Mollusks have no more need for a human heart, than humans have for a mollusk heart. All extant animals have survived the rigor of natural selection and are by definition highly successful. An appreciation of the particular adaptations that underlie these many successes provides important insights into basic principles of oxygen delivery and homeostasis in all animals, including humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Moskowitz for his artwork, Ellen Morgan and Kiichiro Yano for their technical help, and Dena Groutsis for her help in procuring specimens. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL076540. Author contributions: RME designed and performed experiments and analyzed the data. AMD designed and performed experiments and analyzed the data. WCA designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Bilaterality is associated with cephalization (anterior-posterior head-to-tail body axis); a dorsoventral back-to-front axis; and a division of the body into left and right sides.

The deuterostomes and protostomes are considered superphyla of Metazoa. They differ primarily in their embryonic origins. For example, in protostomes, the blastopore becomes the mouth, whereas in deuterostomes it becomes the anus.

These two groups were initially proposed based on molecular phylogenetic analyses of the protostomes (particularly similarities in 18S rRNA genes).

A paraphyletic group is a group whose member species are all descendants of a common ancestry, but that does not contain all the species descended from that ancestor.

For example, all vertebrates have an axial skeleton with vertebral column, brain complexity, an anterior mouth, a posterior anus, a digestive tract, a liver, kidneys, a ventrally located heart (two hearts in the case of hagfish), a closed circulatory system with an endothelial lining, a neural crest, and acquired immunity.

According to Fick’s first law, diffusion is proportional to the concentration gradient and surface area and inversely proportional to the distance. dS/dt=D x A x dC/dx, where dS/dt is the rate of transport, A is the area though which diffusion occurs, dC/dx is the concentration gradient and D is the diffusion coefficient of the substance. See LaBarbera M. Principles of design of fluid transport systems in zoology. Science 1990;249: 992–1000.

There are some exceptions such as higher leeches and the nemertines, in which a coelom exists without a blood vascular system. Conversely, animals with an open circulation (e.g., mollusks and arthropods) have a blood vascular system, but a significantly regressed coelomic system.

The largest have highly branched guts that carry out the functional equivalent of internal transport (see Fig. 1). Reliance on the gut for diffusion of gases and nutrients limits the degree to which the gut may be regionally specialized, e.g., for digestion, absorption.

The pseudocoelom, also referred to as a blastocoelom, is not formed from mesoderm and is not lined by mesothelium. It may represent remnants of the embryonic blastocoel. See Brusca R.C., Brusca G.J. Invertebrates. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2003, p. 48–9.

Mesothelial cells also called myoepithelial cells, peritoneal cells, and cardiac cells.

Examples in mammals include the pericardial cavity, pleural space, and peritoneal cavity.

In fact, the coelom may have evolved initially to provide a hydrostatic skeleton for early soft-bodied, bilaterally symmetrical animals that assumed a crawling or burrowing lifestyle.

The following types of pumps or hearts may be distinguished: 1) myoepithelial cell-containing peristaltic pulsating vessels which propel blood by peristalsis (e.g., annelids and amphioxus), 2) cardiomyocyte-containing tubular hearts (which represent an adaptation of an original peristaltic design) whose beating is synchronous or near-synchronous (e.g., insects); and 3) cardiomyocyte-containing chambered hearts whose beating is synchronous or near-synchronous (e.g., mollusks and vertebrates). The latter two designs are controlled myogenically or neurogenically. See Xavier-Neto, et al. Parallel avenues in the evolution of hearts and pumping organs. Cell Mol Life Sci 2007;64:719–34.

The hemocoel is not a coelom. It may be viewed as a persistent blastoceolic remnant, which has been secondarily derived during evolution. See Brusca R.C., Brusca G.J. Invertebrates. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2003, p. 476.

Mollusks and vertebrates are the only animals that possess a chambered heart with at least one ventricle and atrium. The occurrence of chambered hearts in these two phylogenetically distant groups is an example of convergence.

Some authors have used “closed” to describe systems lined by endothelium (e.g., see McMahon B.R.. Comparative evolution and design in non-vertebrate cardiovascular systems. In D. Sedmera and T. Wang (Eds.), Ontogeny and phylogeny of the vertebrate heart. New York, NY: Springer, 2012; Shigei T., Tsuru H., Ishikawa N. and Yoshioka K. Absence of endothelium in invertebrate blood vessels: significance of endothelium and sympathetic nerve/medial smooth muscle in the vertebrate vascular system. Jpn J Pharmacol 2001;87:253–60). Our definition does not require the presence of a cell lining.

These latter cells, which contain contractile myofibrils, may remain in the coelomic cavity or they may delaminate and constitute a differentiated contractile cell layer between the hemal cavity and coelomic epithelium (giving rise to a multilayered blood vessel wall). See Munoz-Chapuli R., Carmona R., Guadix J.A., Macias D., Perez-Pomares J.M. The origin of the endothelial cells: an evo-devo approach for the invertebrate/vertebrate transition of the circulatory system. Evol Dev 2005;7:351–8; Perez-Pomares JM, Gonzalez-Rosa JM, Munoz-Chapuli R. Building the vertebrate heart – an evolutionary approach to cardiac development. Int J Dev Biol 2009;53:1427–43. In addition to giving rise to contractile myoepithelial cells, coelomic epithelial cells are believed to differentiate into hemocytes during development (see Hartenstein V., Mandal L. The blood/vascular system in a phylogenetic perspective. Bioessays 2006;28:1203–10). Hemocytes are diverse in structure and function, but participate in functions similar to counterparts in vertebrates.

There is no structural equivalent of a vertebrate artery in invertebrates. The term “artery” is often used to describe distributing vessels that supply blood downstream of a pump. In other words, an artery is defined by its efferent relationship to the pump and not by its wall structure.

The action of the body wall muscles on the coelomic fluids provides the hydraulic changes associated with locomotion.

These cells have been variously referred to as vasothelial myobasts, amoebocytes, blood cells, hemocytes or endothelial cells. See Hama, K. The fine structure of some blood vessels of the earthworm, Eisenia foetida. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 1960;7:717–24 (and references therein).

In fact, the giant earthworm represents the largest living terrestrial animal without specialized respiratory organs.

A recent study demonstrated the use of ultra-pure earthworm Hb as a means to improve oxygen delivery in hamsters with severe anemia. See Elmer J, Palmer AF, Cabrales P. Oxygen delivery during extreme anemia with ultra-pure earthworm hemoglobin. Life Sci 2012;91:852–9.

Like vertebrates, they have a hollow dorsal nerve cord, a notochord, segmented muscles, and pharyngeal gill slits. In contrast to vertebrates, the notochord persists in adults and it is the only skeletal structure in its body. Like other chordates, they possess a series of V-shaped muscle blocks (myomeres or myotomes). Although fish-like shape, they lack eyes, paired fins, ears, jaws. They are always half buried in benthic substrate, and filter feed on small particles of plankton.

The reader is referred to an excellent discussion of these concepts in Xavier-Neto, J., et al. Parallel avenues in the evolution of hearts and pumping organs. Cell Mol Life Sci 2007;64:719–34.

This is a nice example of an evolutionary trade-off. In this case, the exoskeleton evolved to provide protection from predators and physical support. However, body size could no longer increase (hence the evolution of molting), the body wall muscles could no longer contribute to blood flow (hence the evolution of the heart) and it was no longer possible to breathe through the skin (hence the evolution of gills).

The cephalopod heart typically consists of a ventricle and two atria. The myocardium contains multiple layers of striated muscle cells, which in turn are covered by a coelomic epithelium.

It is often said that the closed system “allowed” for higher pressures. However, in reality the closed system required high pressures to overcome the systemic resistance associated with a complex distribution system.

The original selection pressure for lungs was aquatic hypoxia, resulting in the appearance of air-breathing fish lungfish. In fish, the heart receives (and is therefore perfused by) deoxygenated mixed venous blood. It has been hypothesized that the lung (in conjunction with the coronary circulation) evolved as an adaptation to myocardial hypoxia. See Farmer CG. Evolution of the vertebrate cardio-pulmonary system. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:573–92. Second,

Laminar flow is required to minimize the energy needed to move blood through these complex vascular systems. Laminar flow through a cylindrical tube can be predicted based on vessel diameter, mean blood velocity, and blood density and viscosity (Reynolds’s number). However, if there are sudden variations in vessel diameter or irregularities in the vessels walls turbulent flow can result. In turbulent flow a significantly greater pressure is required to move a fluid through the vessels as compared to laminar flow.

Brusca offers a nice example of the importance of the level of analysis being considered: The wings of bats and birds are homologous as tetrapod forelimbs, but they are not homologous as “wings” because wings evolved independently in these two groups (i.e., the wings of bats and birds do not share a common ancestral wing). See Brusca, R.C. & Brusca, G.J. Invertebrates, (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass., 2003).

References

- 1.Nesse RM, Bergstrom CT, Ellison PT, Flier JS, Gluckman P, Govindaraju DR, Niethammer D, Omenn GS, Perlman RL, Schwartz MD, Thomas MG, Stearns SC, Valle D. Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Making evolutionary biology a basic science for medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(Suppl 1):1800–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906224106. 0906224106 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinbergen N. On aims and methods in ethology. Z Tierpsychol. 1963;20:410–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brusca RC, Brusca GJ. Invertebrates. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruppert EE, Carle KJ. Morphology of metazoan circulatory systems. Zoomorphology. 1983;103:193–208. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmer CG. Evolution of the vertebrate cardio-pulmonary system. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:573–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maina JN. Structure, function and evolution of the gas exchangers: comparative perspectives. J Anat. 2002;201:281–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedmera D, Wang T. Ontogeny and phylogeny of the vertebrate heart. New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourne G, Redmond JR, Jorgensen DD. Dynamics of the molluscan circulatory ssytem: open versus closed. Physiological Zoology. 1990;63:140–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choma MA, Suter MJ, Vakoc BJ, Bouma BE, Tearney GJ. Physiological homology between Drosophila melanogaster and vertebrate cardiovascular systems. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:411–20. doi: 10.1242/dmm.005231. dmm.005231 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browning J. Octopus microvasculature: permeability to ferritin and carbon. Tissue Cell. 1979;11:371–83. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(79)90050-8. 0040-8166(79)90050-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]