Abstract

Background:

Improving global maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (MNCAH) is a top development priority in Canada, as shown by the $6.35 billion in pledges toward the Muskoka Initiative since 2010. To guide Canadian research investments, we aimed to systematically identify a set of implementation research priorities for MNCAH in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods:

We adapted the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative method. We scanned the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative literature and extracted research questions pertaining to delivery of interventions, inviting Canadian experts on MNCAH to generate additional questions. The experts scored a combined list of 97 questions against 5 criteria: answerability, feasibility, deliverability, impact and effect on equity. These questions were ranked using a research priority score, and the average expert agreement score was calculated for each question.

Results:

The overall research priority score ranged from 40.14 to 89.25, with a median of 71.84. The average expert agreement scores ranged from 0.51 to 0.82, with a median of 0.64. Highly-ranked research questions varied across the life course and focused on improving detection and care-seeking for childhood illnesses, overcoming barriers to intervention uptake and delivery, effectively implementing human resources and mobile technology, and increasing coverage among at-risk populations. Children were the most represented target population and most questions pertained to interventions delivered at the household or community level.

Interpretation:

Investing in implementation research is critical to achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring health and well-being for all. The proposed research agenda is expected to drive action and Canadian research investments to improve MNCAH.

The United Nations' Millennium Development Goals, a set of interrelated targets adopted by world leaders in 2000, catalyzed political commitment toward improving child survival and maternal health. Goals 4 and 5 called for a two-thirds reduction in mortality among children less than 5 years of age and a three-quarters reduction in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, respectively.1 Five years before the goals came to a close, the Muskoka Initiative was launched at the G8 summit to intensify efforts toward improving maternal, newborn and child health in low- and middle-income countries, with Canada investing $2.85 billion to reduce the burden of disease, improve nutrition and strengthen health systems in areas with the greatest need.2 Although there have been substantial gains in reducing global maternal and child mortality, progress has been insufficient to achieve the Millennium Development Goals' targets.3,4 Unacceptably high numbers of women and children are still dying every year, largely due to conditions that could have been prevented or treated if existing cost-effective interventions were made universally available.5 Currently, there is insufficient knowledge on how to effectively implement proven affordable interventions in resource-limited settings.6 Over the past 5 years, Canadian funding through the Muskoka Initiative has focused on scaling up interventions to improve maternal, newborn and child health; however, investments in implementation research have been limited.7 If we are to achieve high, sustainable and equitable coverage of life-saving interventions, addressing this research gap is essential.

The year 2015 marked the beginning of a new global framework - the Sustainable Development Goals - and an additional Canadian pledge of $3.5 billion toward the Muskoka Initiative.2,8 These renewed commitments toward improving maternal, newborn and child health present an opportunity to address the unfinished agenda of the Millennium Development Goals, bridge the gap in implementation research and expand efforts to address the neglected area of adolescent health. We undertook an expert consensus process using standardized methods to systematically identify the top research priorities on the implementation of maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (MNCAH) interventions in low- and middle-income countries with the aim of guiding Canadian research investments over the next 15 years - the timeline of the Sustainable Development Goal targets for 2030.

Methods

Study design

We adapted the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative method.9 This method was designed to assist policy-makers and investors to identify research gaps and examine the potential risks and benefits of investing in different research options. This systematic and transparent approach is the most frequently used method of health research prioritization since 2001, followed by the Delphi, James Lind Alliance and Combined Approach Matrix methods.10 It has now been applied to a wide range of relevant MNCAH topics, including, but not limited to, birth asphyxia, childhood pneumonia and diarrhea, and adolescent sexual and reproductive health.11-14 The method involves 5 stages: (i) defining the context and criteria for priority-setting with input from investors and policy-makers; (ii) listing and scoring research investment options by technical experts using the proposed criteria; (iii) weighting the criteria according to wider societal values with input from other stakeholders; (iv) calculating research priority scores and average expert agreement scores; and (v) ranking research priorities according to research priority scores. An initial stage was added to the present study, in which the steering committee extracted implementation-focused research priorities from the existing Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative literature before inviting input from technical experts. This literature review was conducted to build on the foundation of existing Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative studies, allowing our expert group to review and contribute to a set of research questions previously identified as priority areas.

Setting

This study aimed to inform various stakeholders, including the Canadian Partnership for Women and Children's Health (CanWaCH) community and key Canadian donors and researchers, about research investment options that are expected to improve the implementation of MNCAH interventions in low- and middle-income countries. This process of developing and ranking research questions also allowed researchers to systematically approve a common research agenda and develop a consensus on priorities. The timeline of 15 years was set to coincide with the Sustainable Development Goal targets.

In selecting the criteria against which to evaluate the proposed research questions, the steering committee modified the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative criteria from previous exercises to better reflect the context of implementation.9,15 The 5 criteria selected were answerability by research, research feasibility, deliverability, impact and effect on equity. Table 1 shows the 3 specific subquestions evaluated under each criterion.

Table 1: Criteria for implementation (Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative).

| Criterion | Subquestions |

|---|---|

| Answerable by research | Would you say the research question is well framed? Can a single study or a very small number of studies be designed to answer the research question? Do you think that a study needed to answer the proposed research question would obtain ethical approval without major concerns? |

| Research feasibility | Is it likely that there will be sufficient capacity to carry out the proposed research? Is it feasible to provide the training required for staff to carry out the research? Is the cost and time required for this research reasonable? |

| Deliverability | Taking into account the level of difficulty with implementation of the potential delivery strategy (e.g., need for change of attitudes and beliefs, supervision, transport infrastructure), would you say that this strategy would be deliverable? Taking into account the resources available to implement the intervention, would you say that the potential delivery strategy would be affordable? Taking into account government capacity and partnership required, would you say that the potential delivery strategy would be sustainable? |

| Impact | Will the results of this research fill an important knowledge gap? Are the results from this research likely to shape future planning and implementation? Will the results of this research lead to a long-term reduction in disease burden? |

| Effect on equity | Would you say that the present distribution of the target disease burden/health issue affects mainly the poor and marginalized in the population? Would you say that the poor and marginalized would be the most likely to benefit from the results of the proposed research? Would you say that the proposed research has the overall potential to improve equity in disease burden distribution in the long-term (e.g., 10 yr)? |

Literature review

Through an initial literature search, a team member (O.M.) screened published Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative studies, identifying all research questions potentially relevant to implementation. Two researchers (R.S. and M.B.) then screened this list for research questions explicitly pertaining to implementation, defined as the delivery of interventions (i.e., policies, programs or individual practices) and the translation of research evidence into improved health policy and practice.16,17 These questions were then classified into 4 domains: description (epidemiology), discovery (new interventions), development (improving existing interventions) and delivery (health policy and implementation). We selected the highest-ranked delivery questions from each article, which was followed by an updated search for studies through Google Scholar, PubMed and Web of Science using the keywords: "CHNRI" and "Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative." The 3 highest-ranked delivery questions from each additional article were then added to the list. Finally, the research questions were mapped by theme and position on the continuum of care, removing duplicates and questions within over-represented health areas.

Technical consultation

This study drew upon the expertise of researchers, clinicians and implementing partners from various institutions across Canada. We specifically engaged Canadian-based voices in global health given the focus of the study on guiding Canadian research investment. Experts either volunteered to participate at the CanWaCH meeting in November 2014, were identified from their affiliations with the Coalition of Centres in Global Child Health or SickKids Centre for Global Child Health, or were selected for their known expertise in the field of MNCAH.

Experts were asked to individually review the research questions identified from the literature and propose additional questions. We then thematically organized the combined list of questions by position on the continuum of care, removing overlapping options and questions outside the scope of the exercise. The remaining questions were organized into a marking tool for scoring.

Experts scored each proposed research question against these 5 predetermined criteria, each with 3 subquestions:

Answerable by research: likelihood that the research question can be answered ethically.

Research feasibility: likelihood that there are sufficient resources and time to carry out the research.

Deliverability: likelihood that the research can result in a deliverable, affordable and sustainable implementation strategy.

Impact: likelihood that the results from this research will fill crucial knowledge gaps and shape future planning in implementation research.

Effect on equity: likelihood that the implementation strategy will reduce inequity.

We asked experts to score 1 for yes, 0 for no and 0.5 if they were informed but undecided. If the experts did not feel sufficiently knowledgeable to answer a particular question, they were instructed to leave the cell blank. These blank cells were not included in the calculation of scores.

Analysis

The relative importance of the scoring criteria may vary among stakeholders. In a previous exercise,18 a wide range of stakeholders was polled to weight the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative criteria; however, before scoring, the steering committee decided not to assign weights for this exercise. We weighed all 5 criteria equally in the analysis, as we felt they were of equal importance.

The research priority score and average expert agreement scores were calculated for each research question. The research priority score is the mean of the scores across the 5 criteria, expressed as a percentage. The average expert agreement score is the average proportion of scorers who chose the mode (most common score) across the 15 subquestions asked. The average expert agreement score was calculated as follows:

where q is a question that experts are being asked to evaluate competing research investment options, ranging from 1 to 15, n is the number of scorers who provided the most frequent response and N is the total number of scorers. A Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to examine the association between research priority score and average expert agreement scores.

Results

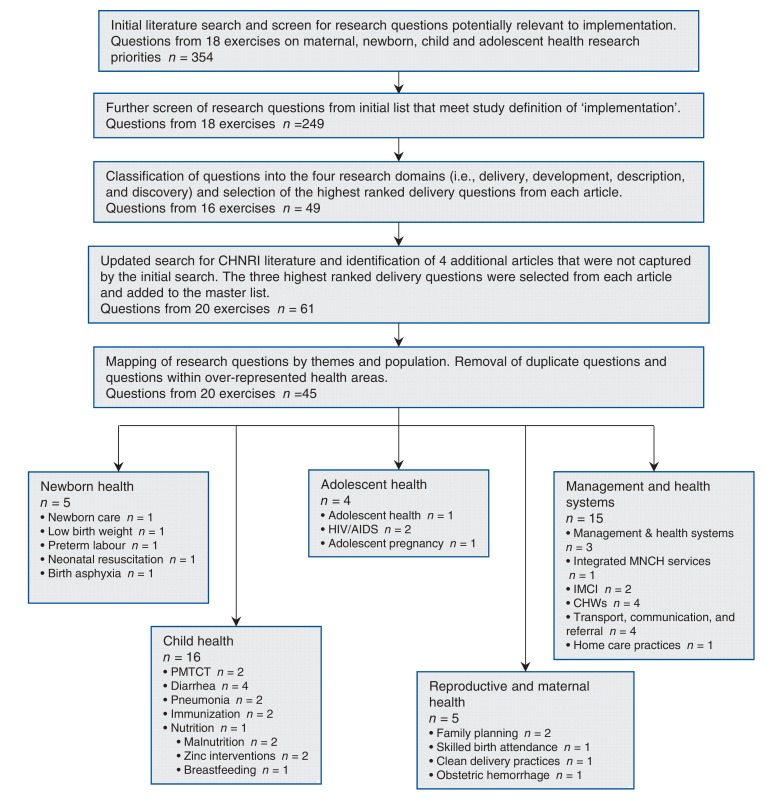

Figure 1 shows how the steering committee identified relevant research questions from existing Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative studies.11-15,19-35 The final list from the literature contained 45 research questions. Thirty-eight experts were then formally invited by email to participate. Six experts volunteered to participate at the CanWaCH meeting, and 32 experts were identified from their affiliations or known expertise. Participants' expertise ranged across the continuum of care, representing knowledge of all 4 target populations.

Figure 1.

Identification of priority research questions from the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative literature. Note: CHW = community health worker, IMCI = integrated management of childhood illness, PMTCT = Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Experts individually reviewed the 45 questions from the literature, with 24 experts proposing 71 additional questions. The steering committee then thematically organized the 116 questions by position on the continuum of care, removing overlapping options. Ninety-seven remaining questions were organized into a marking tool, and 20 experts returned completed scoring sheets.

Table 2 shows the research questions with a rounded research priority score of 80 or more, and Appendix 1 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/1/E82/suppl/DC1) shows the complete list of ranks and scores for all 97 questions. Both tables present the perceived likelihood that each research question will comply with each of the 5 priority-setting criteria. Research priority scores ranged from 40.14 to 89.25, with a median of 71.84. The average expert agreement scores ranged from 0.51 to 0.82, with a median of 0.64. Similar to past Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative exercises, average expert agreement showed a strong positive association with research priority score, as evidenced by a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.783 (p < 0.0001). This finding suggests that there was strong agreement among experts about what were considered priority research questions.

Table 2: Top 15 research questions according to their achieved RPS, with AEA related to each question.

| Rank | Research question | Criterion 1: answerable by research |

Criterion 2: research feasibility | Criterion 3: deliverability | Criterion 4: impact | Criterion 5: equity | RPS | AEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | How can caregivers be mentored in recognizing child health danger signs (e.g., for pneumonia)? | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 89.25 | 0.82 |

| 2 | Identify and evaluate delivery strategies to increase coverage of oral rehydration solution and zinc among remote populations and the poorest of the poor. | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 86.61 | 0.78 |

| 3 | Can improved methods of detecting and managing dehydration in children with diarrhea reduce mortality? | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 86.26 | 0.82 |

| 4 | Evaluate whether coverage of antibiotic treatment can be greatly expanded in safe and effective ways if administered by community health workers. | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 85.62 | 0.79 |

| 5 | How can smart phoneintegrated community case management apps be implemented to accurately identify newborns and under-5 children requiring referral from their communities to a health facility? | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.66 | 84.23 | 0.78 |

| 6 | What are effective delivery strategies to ensure that the most vulnerable individuals receive critical RMNCAH services? | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 83.31 | 0.77 |

| 7 | Evaluate ways to reduce the financial barriers to facility births at the community level, such as through user fee exemptions, emergency loans, conditional cash transfers and transportation vouchers. | 0.73 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 82.05 | 0.74 |

| 8 | Can a simplified neonatal resuscitation program delivered by trained health workers reduce deaths due to intrapartum events and complications and birth asphyxia? | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 81.69 | 0.77 |

| 9 | Can a standardized newborn kit (simple bag/mask, clean blades/knives, and cord clamps) with appropriate education reduce newborn mortality and morbidity? | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.66 | 0.90 | 81.54 | 0.72 |

| 10 | How can mobile technology be used to identify mothers and children at risk, reduce unneeded transports and facilitate earlier timed care? | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 81.52 | 0.75 |

| 11 | What factors drive care-seeking behaviour during childhood diarrheal disease, and how can we position oral rehydration solution and zinc to best respond to these factors? | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 81.32 | 0.71 |

| 12 | Identify and evaluate strategies for retention and motivation of community health workers. | 0.73 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 81.30 | 0.73 |

| 13 | Identify innovative mechanisms to support and utilize existing trained but underutilized human resources in health (such as community midwives in Pakistan, auxiliary nurse midwives in India, and clinical officers in Malawi) to provide high-quality maternal health services in remote and rural areas. | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 80.62 | 0.72 |

| 14 | How can we overcome the barriers to implementing kangaroo care in low-resource settings? | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.53 | 79.75 | 0.72 |

| 15 | How can we overcome barriers to uptake of modern contraceptives in settings with very low prevalence of contraceptive use? | 0.59 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 79.61 | 0.72 |

Note: AEA = average expert agreement, RMNCAH, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health, RPS = research priority score.

The top 15 research questions varied across the continuum of care. Children were the most represented target population, with 6 out of the 15 questions pertaining to child health. Although there were highly-ranked questions about maternal (questions 10 and 13) and newborn health (questions 5, 8, 9 and 14), there were no top-ranked questions that explicitly mentioned adolescents. The highest ranking for an adolescent health question was number 19 - "What factors facilitate uptake, retention and adherence to antiretroviral therapy and minimize HIV treatment failure among adolescents."

A wide range of topics was covered in the top 15 research questions. Diarrhea was the most frequently mentioned health condition, with 2 questions about oral rehydration solution and 1 question about detection and management of dehydration in children with diarrhea.

Research questions varied in specificity. For example, broad questions like "what are effective delivery strategies to ensure that the most vulnerable individuals receive critical reproductive, maternal, newborn child and adolescent health services?" were scored alongside specific questions like "Can a simplified neonatal resuscitation program delivered by trained health workers reduce deaths due to intrapartum events and complications and birth asphyxia?" Both broad and specific questions were ranked in the top and bottom 15 research questions, suggesting that no bias existed against the kind of question asked.

Interpretation

We engaged a diverse group of Canadian experts with knowledge and experience across the continuum of care. The modified Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative approach we used offered greater transparency and replicability than Delphi or other consultative processes.10 The systematic ranking of proposed research priorities against predetermined criteria also made apparent the strengths and weaknesses of competing research investment options.

The comprehensive list of research priorities generated by this exercise addressed leading causes of newborn, child and maternal death, including intrapartum events and complications, diarrhea and barriers to facility births.36 The 3 most important coverage gaps identified by the Countdown to 2015 for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Survival group (Countdown) were present in our list of priorities; they included family planning, interventions addressing newborn mortality and case management of childhood diseases.36 Countdown reported that there are relatively smaller inequities in coverage for interventions that are delivered close to home.37 Our list of priorities was consistent with this finding, because most highly ranked research questions pertained to interventions that could be implemented at the household or community level. Seven of the 15 top-ranked questions originated from the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative literature and 2 of these questions (questions 7 and 12) came from Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiatives explicitly focused on implementation, indicating strong agreement between our expert group and the existing literature.15,30

Limitations

Although the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative method represents a systematic attempt to address the challenges inherent in the complex process of research investment priority setting, the approach is not without limitations. Yoshida and colleagues conducted an analysis of the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative methodology,38 examining the concordance among top-ranking research priorities as sample size increases from 15 to 90. They found that a high degree of reproducibility of top-ranking research priorities was achieved with 45-55 experts, suggesting that our relatively small sample of 20 scorers may be a limitation. However, it should be noted that they still found an appreciable degree of reproducibility with a sample of only 15 people. In addition, it is possible that there were sound research options that were not included in the list of questions generated by the literature and experts. These options, therefore, could not have been scored and identified as priorities. Proposed research questions and their subsequent scores were also limited to the opinions of the experts involved in the exercise. In an effort to minimize response bias, we employed a comprehensive process of identifying experts with relevant knowledge and experience. Although this process was nonsystematic, we deliberately invited only Canadian experts given the focus of the exercise on informing Canadian research investments. The predetermined Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative criteria also ensured that questions were anonymously scored against a transparent and standardized set of values, thus eliminating the advantage of more eloquent speakers advocating for their own research agenda. An additional potential limitation was that experts might have scored questions about patient populations or health conditions outside of their area of expertise. To avoid inaccurate scores, experts were instructed to leave the cell blank when they did not feel sufficiently knowledgeable to answer a particular question.

The top 15 research questions varied across the continuum of care, but there were no highly-ranked questions that explicitly mentioned adolescents. The steering committee noted that existing Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative literature on adolescent health was limited. In light of this gap, we made an effort to recruit adolescent health experts to propose additional research questions and provide scores. Adolescent health is an emerging global health priority and although this population was not explicitly mentioned among the top-ranked research questions, it should be noted that questions pertaining to maternal and reproductive health could also be relevant to adolescents, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Moreover, since the completion of this study, there has been a Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative study published, focusing on 8 areas of adolescent health.39

Conclusion

Current investments in health research predominantly target diseases prevalent in high-income countries and tend to favour basic science research. If progress toward improving MNCAH is to be made by 2030, improving implementation is crucial to maximizing the impact of existing interventions and reducing inequity. The research gaps identified through this priority-setting exercise cannot be addressed in isolation; they must be integrated with the measurement and accountability agenda, so as to ensure there is timely data on the quality and coverage of effective interventions. The proposed research agenda is expected to be a valuable tool in guiding research investments that could drive substantial improvement in health outcomes by 2030. We call upon the Canadian community of donors, researchers, policy-makers and program managers to support the translation of these recommendations into appropriate and transparent funding opportunities.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/1/E82/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge James Blanchard, Andrea Hunter and Rachel Spitzer for their participation; Kerri Wazny for providing technical support; and the Canadian Partnership for Women and Children's Health (CanWaCH) for their support in this collaborative effort. CanWaCH is a collaboration of more than 80 Canadian organizations that are working to improve maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health in low- and middle-income countries.

Footnotes

Funding: This project was funded by the Centre for Global Child Health at the Hospital for Sick Children and the Canadian Partnership for Women and Children's Health.

Members of the Canadian Expert Group on Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health: Lisa Avery MD MIH (Centre for Global Public Health, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Man.), Diego G. Bassani PhD (Centre for Global Child Health, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ont.), Alan D. Bocking MD (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Toronto; Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Toronto, Ont.), Kevin J. Chan MD MPH (Department of Pediatrics, Memorial University; Children and Women's Health Program, Eastern Health, St. John's, NL), Maryanne Crockett MD MPH (Centre for Global Public Health, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Man.), Stephen B. Freedman MDCM MSc (Alberta Children's Hospital and Research Institute, University of Calgary, Alta.), Miriam Kaufman BSN MD (Department of Adolescent Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ont.), Niranjan Kissoon MBBS (British Columbia Children's Hospital; Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC), Eugene A. Krupa PhD Med (Catalyst Research & Development Inc.; University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alta.), Charles P. Larson MD (Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC), Vanessa Mathews-Hanna MPH (World Renew, Burlington, Ont.), Douglas McMillan MD (Dalhousie University; IWK Health Centre, Halifax, NS), Shaun Morris MD MPH (Centre for Global Child Health, The Hospital for Sick Children; Department of Pediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.), Zubia Mumtaz MBBS PhD (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alta.), Gregor Reid PhD DrHS (Canadian Centre for Human Microbiome and Probiotic Research, Lawson Health Research Institute; Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, London, Ont.), Selim Rashed MPH MD (Maisoneuve Rosmont Hospital, University of Montreal; Montreal University Health Center, McGill University, Montréal, Que.), Prakeshkumar S. Shah MBBS MD (Department of Pediatrics and Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.), Nalini Singhal MD (Alberta Children's Hospital and Research Institute and Department of Paediatrics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alta.), Alan Talens MD MPH (World Renew, Burlington, Ont.); Stanley H. Zlotkin MD PhD (Centre for Global Child Health, The Hospital for Sick Children; Department of Pediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.).

References

- 1.Resolution adopted by the General Assembly: 55/2. United Nations Millennium Declaration. United Nations. 2000. Sept. 18. [accessed 2015 Nov. 24]. Available www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm.

- 2.Canada's ongoing leadership to improve the health of mothers, newborns and children (2015-2020). Ottawa: Government of Canada. 2015. [accessed 2015 ]. [Oct. 29]. Available www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/development-developpement/health_women-sante_femmes/canada_leadership_2015-2020.aspx?lang=eng.

- 3.Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, et al. United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group collaborators and technical advisory group. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2016;387:462–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, et al. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. (UN IGME). Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet. 2015;386:2275–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, et al. Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year. Lancet. 2003;362:65–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryce J, el Arifeen S, Pariyo G, et al. Multi-Country Evaluation of IMCI Study Group. Reducing child mortality: can public health deliver. Lancet. 2003;362:159–64. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13870-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Projects funded through the Muskoka Initiative ($1.1 billion). Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada. 2015. [accessed 2015 Oct. 29]. Available www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/cidaweb/cpo.nsf/fWebProjListEn?ReadForm&profile=SMNE-MNCH.

- 8.Resolution adopted by the General Assembly: 70/1. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. 2015 Oct. 21. [accessed 2015 Sep. 25]. Available www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1.

- 9.Rudan I, Gibson JL, Ameratunga S, et al. Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: guidelines for implementation of the CHNRI method. Croat Med J. 2008;49:720–33. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.49.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida S. Approaches, tools and methods used for setting priorities in health research in the 21st century. J Glob Health. 2016;6:010507. doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.010507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawn JE, Bahl R, Bergstrom S, et al. Setting research priorities to reduce almost one million deaths from birth asphyxia by 2015. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudan I, El Arifeen S, Bhutta ZA, et al. WHO/CHNRI Expert Group on Childhood Pneumonia. Setting research priorities to reduce global mortality from childhood pneumonia by 2015. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wazny K, Zipursky A, Black R, et al. Setting research priorities to reduce mortality and morbidity of childhood diarrhoeal disease in the next 15 years. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hindin MJ, Christiansen CS, Ferguson J. Setting research priorities for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:10–18. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.107565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wazny K, Sadruddin S, Zipursky A, et al. Setting global research priorities for integrated community case management (iCCM): results from a CHNRI (Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative) exercise. J Glob Health. 2014;4:020413. doi: 10.7189/jogh.04.020413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Implementation science information and resources. Bethesda (MD): Fogarty International Center. [accessed 2016 Sept. 12]. Available https://www.fic.nih.gov/researchtopics/pages/implementationscience.aspx.

- 17.Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, et al. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ. 2013;347:f6753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapiriri L, Tomlinson M, Chopra M, et al. Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI) Setting priorities in global child health research investments: addressing values of stakeholders. Croat Med J. 2007;48:618–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomlinson M, Chopra M, Sanders D, et al. Setting research priorities in child health research investments for South Africa. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walley J, Lawn JE, Tinker A, et al. Lancet Alma-Ata Working Group. Primary health care: making Alma-Ata a reality. Lancet. 2008;372:1001–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown KH, Hess SY, Boy E, et al. Setting priorities zinc-related health research to reduce children's disease burden worldwide: an application of the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:389–96. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosek M, Lanata CF, Black RE, et al. Directing diarrhoeal disease research towards disease burden reduction. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27:319–31. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i3.3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bahl R, Martines J, Ali N, et al. Research priorities to reduce global mortality from newborn infections by 2015. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(Suppl):S43–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819588d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fontaine O, Kosek M, Bhatnagar S, et al. Setting research priorities to reduce global mortality from childhood diarrhoea by 2015. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudan I, Theodoratou E, Zgaga L, et al. Setting priorities for the development of emerging interventions against childhood pneumonia, meningitis and influenza. J Glob Health. 2012;2:010304. doi: 10.7189/jogh.02.010304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahl R, Martines J, Bhandari N, et al. Setting research priorities to reduce global mortality from preterm birth and low birth weight by 2015. J Glob Health. 2012;2:010403. doi: 10.7189/jogh.02-010403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dean S, Rudan I, Althabe F, et al. Setting research priorities for preconception care in low-and middle-income countries: aiming to reduce maternal and child mortality and morbidity. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhutta ZA, Zipursky A, Wazny K, et al. Setting priorities for development of emerging interventions against childhood diarrhoea. J Glob Health. 2013;3:010302. doi: 10.7189/jogh.03.010302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali M, Seuc A, Rahimi A, et al. A global research agenda for family planning: results of an exercise for setting research priorities. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:93–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.122242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George A, Young M, Bang A, et al. GAPPS Expert Group on Community Based Strategies and Constraints. Setting implementation research priorities to reduce preterm births and stillbirths at the community level. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morof DF, Kerber K, Tomczyk B, et al. Neonatal survival in complex humanitarian emergencies: setting an evidence-based research agenda. Confl Health. 2014;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angood C, McGrath M, Mehta S, et al. MAMI Working Group Collaborators. Research priorities to improve the management of acute malnutrition in infants aged less than six months (MAMI). PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rollins N, Chanza H, Chimbwandira F, et al. Prioritizing the PMTCT implementation research agenda in 3 African countries: integrating and scaling up PMTCT through implementation research (INSPIRE). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(Suppl 2):S108–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Souza JP, Widmer M, Gulmezoglu AM, et al. Maternal and perinatal health research priorities beyond 2015: an international survey and prioritization exercise. Reprod Health. 2014;11:61. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida S, Rudan I, Lawn J, et al. neonatal health research priority setting group. Newborn health research priorities beyond 2015. Lancet. 2014;384:e27–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Requejo JH, Bryce J, Barros AJ, et al. Countdown to 2015 and beyond: fulfilling the health agenda for women and children. Lancet. 2015;385:466–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A decade of tracking progress for maternal, newborn and child survival: the 2015 Report - Countdown to 2015. UNICEF and World Health Organization. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida S, Rudan I, Cousens S. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: VI. Quantitative properties of human collective opinion. J Glob Health. 2016;6:010503. doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.010503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagata JM, Ferguson BJ, Ross DA. Research priorities for eight areas of adolescent health in low- and middle-income countries. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.