Abstract

Background:

The detection and management of chronic kidney disease lies within primary care; however, performance measures applicable in the Canadian context are lacking. We sought to develop a set of primary care quality indicators for chronic kidney disease in the Canadian setting and to assess the current state of the disease's detection and management in primary care.

Methods:

We used a modified Delphi panel approach, involving 20 panel members from across Canada (10 family physicians, 7 nephrologists, 1 patient, 1 primary care nurse and 1 pharmacist). Indicators identified from peer-reviewed and grey literature sources were subjected to 3 rounds of voting to develop a set of quality indicators for the detection and management of chronic kidney disease in the primary care setting. The final indicators were applied to primary care electronic medical records in the Electronic Medical Record Administrative data Linked Database (EMRALD) to assess the current state of primary care detection and management of chronic kidney disease in Ontario.

Results:

Seventeen indicators made up the final list, with 1 under the category Prevalence, Incidence and Mortality; 4 under Screening, Diagnosis and Risk Factors; 11 under Management; and 1 under Referral to a Specialist. In a sample of 139 993 adult patients not on dialysis, 6848 (4.9%) had stage 3 or higher chronic kidney disease, with the average age of patients being 76.1 years (standard deviation [SD] 11.0); 62.9% of patients were female. Diagnosis and screening for chronic kidney disease were poorly performed. Only 27.1% of patients with stage 3 or higher disease had their diagnosis documented in their cumulative patient profile. Albumin-creatinine ratio testing was only performed for 16.3% of patients with a low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and for 28.5% of patients with risk factors for chronic kidney disease. Family physicians performed relatively better with the management of chronic kidney disease, with 90.4% of patients with stage 3 or higher disease having an eGFR performed in the previous 18 months and 83.1% having a blood pressure recorded in the previous 9 months.

Interpretation:

We propose a set of measurable indicators to evaluate the quality of the management of chronic kidney disease in primary care. These indicators may be used to identify opportunities to improve current practice in Canada.

Chronic kidney disease is common. The median prevalence among adults aged 30 years and older is estimated to be 7.2%, and between 23.4% and 35.8% for people more than 64 years of age.1 Chronic kidney disease has a prevalence similar to that of diabetes2 and engenders at least the same amount of risk for cardiovascular events and death,3-6 yet it does not get as much attention with respect to quality improvement. Studies in Canada,7,8 the United States,9-11 the United Kingdom12,13 and Australia14,15 have universally identified gaps in care and knowledge about chronic kidney disease among patients and providers in both primary care and specialist settings.

Many countries have guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease,16-18 including Canada.19 In 2014, the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes group published international chronic kidney disease guidelines.20 Guideline statements typically represent important processes of care, such as appropriate use of diagnostic tests and medications. Processes that are supported by high-quality evidence are more likely to improve outcomes; hence, measuring guideline adherence is increasingly used to assess care quality.21 Measures of quality for chronic kidney disease care are uncommon, and are not currently included in major measurement sets such as the American Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measures.22 The Quality and Outcomes Framework in the UK includes only 1 measure specific to chronic kidney disease.23 National primary care quality indicators in Canada24 currently include no measures related specifically to chronic kidney disease.

We set out to develop a set of primary care quality indicators for chronic kidney disease in the Canadian setting and to assess the current state of the disease's detection and management in the primary care setting using electronic medical record (EMR) data from a representative sample of Ontario physicians and patients.

Methods

Quality indicator selection

We used a modified Delphi approach to establish a chronic kidney disease quality indicator measurement set for primary care. We used a multifaceted search strategy of peer-reviewed and grey literature sources to identify chronic kidney disease-related measures used by other organizations. We then performed a focused search to identify clinical practice guidelines specific to the diagnosis and management of chronic kidney disease. We used AGREE II25 criteria (for quality assessment of guidelines) to only include high-quality guidelines, from which we extracted recommendations for consideration by the Delphi panel as evidentiary support for the identified measures. We did not use recommendations from clinical practice guidelines to develop new indicators; rather, the information from the guidelines was used to shape the indicators during the Delphi process (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/1/E74/suppl/DC1).

Identified quality measures were reviewed by the project clinical leads in primary care (KT) and nephrology (GN) for relevance to chronic kidney disease in the primary care setting, and the retained measures were submitted to the Delphi panel for prioritization.

Panel members and modified Delphi process

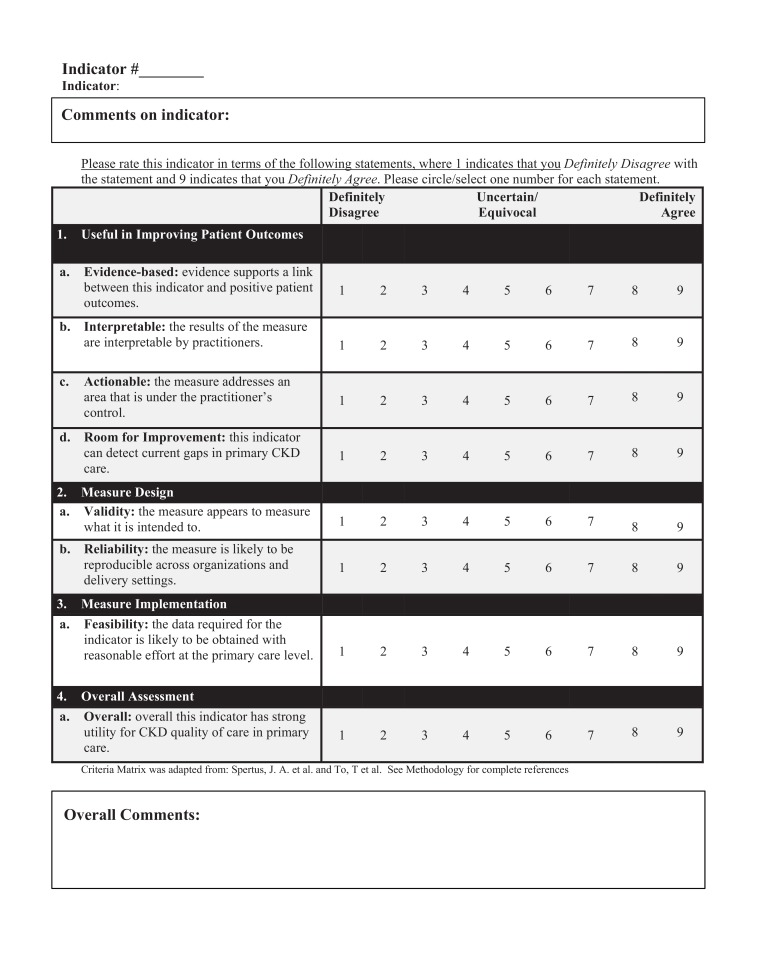

We invited 20 panel members from across Canada for participation in a modified Delphi process. Ten were family physicians, 7 were nephrologists with clinical and methodological expertise, 1 was a patient, 1 was a primary care nurse and 1 was a pharmacist. Each panel member completed conflict of interest and consent forms. Panelists completed 3 rounds of ratings of candidate measures using a Web-based tool and a criteria matrix based on an adaptation from previously established criteria26,27 (Figure 1). Panelists participated in a webinar after the first round, to allow for discussion and consensus building. Panelists provided qualitative feedback during the review, and could propose new measures. Measures were excluded at each round according to the criteria in Box 1. Panelists reviewed their own responses, the panel's aggregate responses and qualitative feedback at each round. The study team considered qualitative feedback and Canadian practice guidelines in modifying selected candidate measures to align with Canadian standards (e.g., blood pressure targets). After 3 rounds of rating and the webinar, indicators that met the inclusion criteria (Box 1) were reviewed by the panel and clinical leads for face validity and comprehensiveness to derive the final measurement set.

Figure 1.

Indicator rating criteria matrix.

Box 1: Filter criteria.

Exclusion criteria:

• 75% or more of panel member ratings of the "overall" criteria fell within the bottom 2 tertiles (between 1 and 6 on a 9-point Likert scale)

OR

• 75% or more of panel members' composite ratings (sum of ratings for all 7 sub-criteria) fell within the bottom 2 tertiles (7-48)

Inclusion criteria:

• 75% or more of panel member ratings of the "overall" criteria fell within the top tertile (between 7 and 9 on a 9-point Likert scale)

OR

• 75% or more of panel members' composite ratings (sum of ratings for all 7 sub-criteria) fell within the top tertile (49-63)

AND

• Median "overall" score ≥ 7

Measurement of quality indicators

Using our final measurement set, we performed a current state analysis of detection and management practices in a convenience sample that consisted of Ontario residents and physicians. We used the Electronic Medical Record Administrative data Linked Database (EMRALD), which captures clinically relevant data contained in nearly 400 family physician EMRs distributed across Ontario. The representativeness of EMRALD patients and physicians, in addition to the quality and comprehensiveness of EMRALD data, has been previously found to be generally reflective of the Ontario population.28,29 Young adults and people with lower socioeconomic status are slightly under represented in EMRALD compared with the general Ontario population; however, this is likely characteristic of the types of people that see a physician and not anything specific to EMRALD patients. Relative to all Ontario physicians, EMRALD physicians practise more in rural locations and fewer are foreign-trained physicians.28

To operationalize our measures using EMR data, we introduced a number of additional specifications. We included patients greater than 18 years of age at index date with an EMR record that began at least 1 year before the extraction of the EMR data in the summer/fall of 2014. For indicators for patients with chronic kidney disease, we identified patients with stage 3 or greater disease as having a most recent estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and a second abnormal reading at least 3 months earlier. We excluded patients with chronic kidney disease who were receiving dialysis as documented in the cumulative patient profile, because patients on dialysis were considered to be beyond the domain of primary care for management of their condition. For the first indicator, "The primary care provider can identify patients in their practice aged 18 or over with chronic kidney disease," the proxy EMR measure was a recording of chronic kidney disease or it's synonyms in the cumulative patient profile, a discrete EMR field, typical of family physician patient records, which contains a "history of past health" and active "problem list." For the 2 indicators that were written as "… initial eGFR less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 …," we defined "initial" as the first eGFR at least 6 months before the date the data was extracted to allow for at least 6 months to look for a repeat test or albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) test. For the "percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease that had a serum potassium test 7-30 days after the initial angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) prescription," we only included patients with ACE inhibitor-ARB prescriptions after a full year of no ACE inhibitor-ARB prescription, thus ensuring new-user status among patients included in the denominator. For the indicator "percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease simultaneously receiving both an ACE inhibitor and an ARB," the numerator only included patients that received a prescription for both types of medications on the same day.

We used validated methods for identifying patients with diabetes30,31 and included patients with hypertension who had hypertension recorded in their cumulative patient profile, who had an elevated blood pressure and a prescription for an antihypertensive on the same day and a prescription for an antihypertensive in the past 18 months, or who met Canadian Hypertension Education Program Criteria for hypertension at any time in their EMR record and an elevated blood pressure or antihypertensive prescription in the past 18 months. This algorithm had a sensitivity of 81.1%, specificity of 97.7%, positive predictive value of 93.2% and negative predictive value of 93.1% in a validation study involving 969 randomly selected adults that compared EMRALD with chart-abstracted data.32-34

All analyses were done in SQL Server Management Studio 2012.

Ethics approval

The Sunnybrook Health Sciences Research Ethics Board approved both phases of the project.

Results

Modified-Delphi panel results

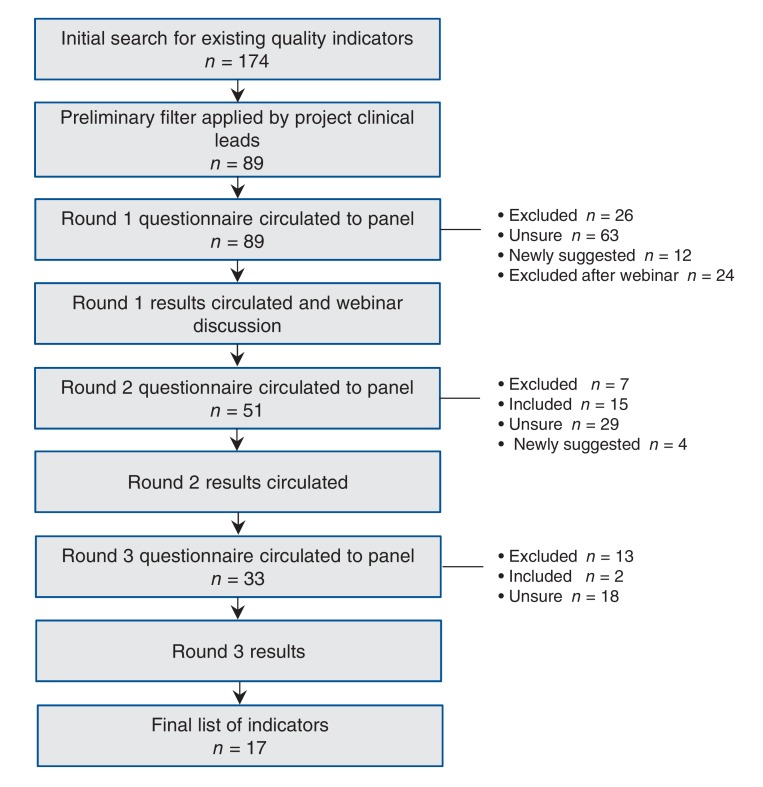

We identified 174 measures published by 26 sources (Figure 2). After review by clinical leads, 89 measures (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/1/E74/suppl/DC1 were submitted to the panel. The response rate for all 3 of the rating rounds of the panel process was 100%. Seventeen indicators made up the final list, with 1 under the category Prevalence, Incidence and Mortality; 4 under Screening, Diagnosis and Risk Factors; 11 under Management; and 1 under Referral to a Specialist (Box 2). There were 2 categories, System Level and Lifestyle, for which no indicators met the inclusion criteria. The panel acknowledged through discussion that, though important, System Level indicators are likely outside of the family physicians' control. Lifestyle-related indicators (e.g., smoking cessation, dietary, exercise counselling) did not get included because the panel rated them as low in their feasibility to measure in the EMR.

Figure 2.

Modified Delphi panel process.

Box 2: Quality indicators resulting from Delphi panel process.

Prevalence, incidence and mortality

1. The primary care providers can identify patients in their practice aged 18 years and older with chronic kidney disease.

Screening, diagnosis and risk factors

2. Percentage of patients with an initial estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 that is followed by a repeat test within 6 months.

3. Percentage of patients with an initial eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 with an albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) test conducted within 6 months.

4. Percentage of patients with risk factors for chronic kidney disease (diabetes, hypertension) with an eGFR in the past 18 months.

5. Percentage of patients with risk factors for chronic kidney disease (diabetes, hypertension) with an ACR in the past 18 months.

Management

6. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with an eGFR in the past 18 months.

7. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with an ACR in the past 18 months.

8. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with a blood pressure recorded in the past 18 months.

9. Percentage of patients with diabetes and albuminuria (moderately or severely increased ACR ≥ 3 mg/mmol) with a blood pressure recorded in the past 9 months.

10. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with a most recent blood pressure < 140/90 mm Hg, or with chronic kidney disease and diabetes with a most recent blood pressure < 130/80 mm Hg.

11. Percentage of patients with diabetes and albuminuria (moderately or severely increased ACR ≥ 3 mg/mmol) who were prescribed an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) unless a contraindication or adverse effects are recorded.

12. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease who had a serum potassium test 7-30 days after initial ACE inhibitor-ARB prescription.

13. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease simultaneously receiving both an ACE inhibitor and an ARB.

14. Percentage of patients with stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease and a prescription for a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for more than 2 weeks.

15. Percentage of patients ≥ 50 years and ≤ 80 years of age with stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease and taking a statin unless contraindicated.

16. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease who received an influenza vaccine in the past year unless contraindicated.

Referral to a specialist

17. Percentage of patients age < 80 years with a referral to a nephrologist for eGFR < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Measurement of quality indicators

Overall, of the 140 147 eligible adult patients in EMRALD, 101 561 (72.5%) had at least 1 eGFR in their chart and although only 76 935 (54.9%) patients had at least 2 eGFRs recorded in their chart, 16 585 of 17 299 (95.9%) of the patients with an eGFR less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 had at least 1 additional eGFR test. There were 154 dialysis recipients who were removed from analysis; of the remaining patients, 6848 of 139 993 (4.9%) had stage 3 or greater chronic kidney disease. The mean age of the EMRALD cohort was 50.0 (standard deviation [SD] 18.3) years, with 57.2% of the cohort being female. The mean age of patients in our cohort with stage 3 or greater chronic kidney disease was 76.1(SD 11.0) years, with 62.9% being female. The mean duration of the EMR record was 5.8 (SD 2.9) years. Among our patients with stage 3 or greater disease, 32.9% had diabetes and 70.3% had hypertension, compared with 10.6% with diabetes and 23.1% with hypertension in the general EMRALD population.

Family physician performance was highest in avoiding nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), avoiding simultaneous prescription of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, and measuring eGFR and blood pressure for patients with stage 3 or greater chronic kidney disease, with over 80% adherence in these measures (Table 1). In addition, more than 70% of patients with a clinical indication were prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB and had an eGFR measured if at high risk for chronic kidney disease. Less than 70% of applicable patients had a referral to a nephrologist, had received influenza vaccine, met blood pressure targets, were prescribed a statin, or had a potassium test 7-30 days after starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB. It is notable that ACR testing was part of 3 of the 5 most poorly performed indicators. Less than 50% of patients at risk for chronic kidney disease had an ACR done, had their chronic kidney disease documented in their cumulative patient profile, had an ACR done or a repeat eGFR if their initial eGFR was less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 within 6 months, or had an ACR in the past 18 months if they had chronic kidney disease.

Table 1: Results as applied in Electronic Medical Record Administrative data Linked Database (EMRALD).

| Quality indicator | Numerator | Denominator | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence, incidence and mortality | |||

| 1. Patients with stage 3 or greater chronic kidney disease who have it documented in their cumulative patient profile* | 1856 | 6848 | 27.1 |

| Screening, diagnosis & risk factors | |||

| 2. Percentage of patients with an initial eGFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with an eGFR within 6 months* | 4068 | 8573 | 47.5 |

| 3. Percentage of patients with an initial† eGFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with an ACR within 6 months* | 1400 | 8573 | 16.3 |

| 4. Percentage of patients with risk factors for chronic kidney disease (diabetes, hypertension) with an eGFR in the past 18 months | 23 998 | 32 637 | 73.5 |

| 5. Percentage of patients with risk factors for chronic kidney disease (diabetes, hypertension) with an ACR in the past 18 months | 9291 | 32 637 | 28.5 |

| Management | |||

| 6. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with an eGFR in the past 18 months | 6190 | 6848 | 90.4 |

| 7. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with an ACR in the past 18 months | 2341 | 6848 | 34.2 |

| 8. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with a BP recorded in the past 9 months | 5692 | 6848 | 83.1 |

| 9. Percentage of patients with diabetes and albuminuria (moderately or severely increased ACR ≥ 3 mg/mmol) with a BP recorded in the past 9 months | 5439 | 6320 | 86.1 |

| 10. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with a most recent BP < 140/90 mm Hg, or with chronic kidney disease and diabetes with a most recent BP < 130/80 mm Hg | 4465 | 6848 | 65.2 |

| 11. Percentage of patients with diabetes and albuminuria (moderately or severely increased ACR ≥ 3 mg/mmol) who were prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB unless a contraindication or adverse effects are recorded | 3734 | 4997 | 74.7 |

| 12. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease who had a serum potassium test 7-30 days after initial ACE inhibitor-ARB prescription* | 2944 | 4965 | 59.3 |

| 13. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease with an ACE inhibitor and an ARB prescription on the same day* | 48 | 6848 | 0.7 |

| 14. Percentage of patients with chronic kidney disease and ≥ 1 prescription for NSAIDs* | 99 | 6848 | 1.4 |

| 15. Percentage of patients ≥ 50 years and ≤ 80 years of age with chronic kidney disease taking a statin unless contraindicated | 2236 | 3701 | 60.4 |

| 16. Percentage of patents with chronic kidney disease who received an influenza vaccine in the past year unless contraindicated | 4493 | 6848 | 65.6 |

| Referral to a specialist | |||

| 17. Percentage of patients aged < 80 years with a referral to a nephrologist for eGFR < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 339 | 508 | 66.7 |

Note: ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme, ACR = albumin-creatinine ratio, ARB = angiotensin II receptor blocker, BP = blood pressure, eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate, NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

*Modified to be feasible to measure.

†First eGFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 at least 6 months before the load date of the electronic medical record.

Interpretation

Through a modified Delphi process, we established a set of primary care indicators for detecting and managing chronic kidney disease in a Canadian context. In addition, we were able to show the feasibility of measuring these indicators to gain an understanding of the current state of the detection and management of this disease in the primary care setting in Ontario, which could allow us to identify gaps in care and determine areas that should be targeted for improvement.

Our measures span a broad range of identified measurement domains and concepts. A US-based panel identified 12 measures for the primary care management of chronic kidney disease.35 Most were conceptually similar to ours in terms of identifying important actions in the management of chronic kidney disease, although they differed slightly in their definitions of time frames for actions. An annual complete blood count for patients with stage 3b-5 disease and avoidance of bisphosphonates in patients with an eGFR of less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 were included in the US indicators, but not in ours. Recently, a Japanese team followed a modified Delphi method to identify a set of quality indicators for the care of chronic kidney disease in the primary care setting.36 They selected 11 indicators, of which 7 were conceptually similar to ours, with 4 measures not included in our set: prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy, glycemic control of diabetes in chronic kidney disease, avoidance of biguanides in diabetes and quarterly urine testing. With respect to lipid management in chronic kidney disease, our indicator measured statin prescribing, which is within the provider's control. The US-based panels' indicator required cholesterol testing, and the Japanese indicator was based on achieving a cholesterol target, which is not necessarily within the provider's control.

We found the lack of documentation in problem lists or past medical history of chronic kidney disease by family physicians consistent with other studies that identified the lack of recognition of chronic kidney disease by primary care physicians.13,37 Although our indicator methods differed slightly from previous measures in the primary care setting in the US, we found similar rates of lipid-lowering medication use (~60%) and avoidance of NSAID prescribing.38 Our prevalence rates for stage 3 or greater disease (4.9%) were lower than identified elsewhere, but other studies based their diagnosis on a single eGFR measure and did not exclude patients who were undergoing dialysis.13,38 The higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease that we found among women was similar to those found in the UK and in the US, and the rates of diabetes and hypertension were similar to the American rates, but higher than those found in the UK.13,38

Limitations

It was necessary to modify some of the indicators for measurement because we only had laboratory data as far back as the date of creation of each EMR record. Therefore, we could not confirm disease onset and duration because we could not be certain that the first occurrence of an eGFR of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the EMR was the first ever for a given patient. This limitation required us to redefine "initial" in indicators that measured repeat testing after the initial eGFR of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. It is possible that if we had the initial eGFR, our measured performance rate for repeat or ACR testing may have been higher. However, it is unlikely that it would have been significantly higher given the low rate of ACR testing in general.

In Ontario, the eGFR is typically provided when serum creatinine testing is ordered and is calculated at the laboratory using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.39 However, the MDRD equation only takes into account white and black ethnicity, and does not consider the ethnic diversity of the Ontario population. Ethnicity is not typically provided when the laboratory test is ordered, thus it is likely that even the correction factor for black patients is not applied. The MDRD equation may underestimate eGFR and therefore may have led to overdiagnosis. More recently, in 2015, Ontario laboratories have switched to using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation,40 which is considered to be more accurate, particularly for women and the younger population. However, this change occurred after the conduct of our analysis.

It is possible that influenza vaccines were given to patients but not recorded in the EMR because patients in Ontario may receive influenza vaccines outside of the family physician's office (e.g., at shopping malls, pharmacies or public health units), and the completeness of this recording in EMRs is unknown.

We did not have access to medication duration and precise medication discontinuation dates; therefore, we were required to make estimates on timing and duration for medication indicators.

Finally, we are limited by identifying patients with chronic kidney disease through the laboratory tests in the EMR. It is likely that laboratory tests ordered by specialists or in hospital are not accounted for in our analysis.

Conclusion

We have developed a set of quality indicators for the detection and management of chronic kidney disease that are feasible to measure. Through our application of these indicators to real-world primary care EMR data, we have identified areas that need improvement. Future studies that focus on understanding why physicians are not ordering ACR tests and appear not to be recognizing chronic kidney disease are needed. We have been unable to identify similar quality indicator measurement in other provinces in Canada; however, it is hopeful with the release of these indicators that other provinces may be able to do comparable analyses in the future.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/1/E74/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by a grant from the Ontario Renal Network. The authors would like to thank all the members of the panel for their participation and expertise (Dr. Adeera Levin, Dr. Allan Grill, Dr. Amit Garg, Betty Hogeterp, Dr. Blaise Clarkson, Dr. Brenda Hemmelgarn, Dr. Brian Hutchison, Dr. Elizabeth Muggah, Dr. Francois Madore, Dr. Kevin Samson, Dr. Liisa Jaakkimainen, Michael McCormick, Dr. Noah Ivers, Dr. Patricia Marr, Dr. Roland Grad, Dr. Scott Brimble, Dr. Sharon Johnston and Dr. Sheldon Tobe).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intented or should be inferred.

References

- 1.Zhang QL, Rothenbacher D. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in population-based studies: systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipscombe LL, Hux JE. Trends in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality in Ontario, Canada 1995-2005: a population-based study. Lancet. 2007;369:750–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296–305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, et al. Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:659–63. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson DW. Evidence-based guide to slowing the progression of early renal insufficiency. Intern Med J. 2004;34:50–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.t01-6-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trivedi HS, Pang MM, Campbell A, et al. Slowing the progression of chronic renal failure: economic benefits and patients' perspectives. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:721–9. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.31990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonelli M, Bohm C, Pandeya S, et al. Cardiac risk factors and the use of cardioprotective medications in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:484–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens L, Cooper S, Singh R, et al. Detection of chronic kidney disease in non-nephrology practices An important focus for intervention. BCMJ. 2005; 47:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coresh J, Byrd-Holt D, Astor BC, et al. Chronic kidney disease awareness, prevalence, and trends among US adults, 1999 to 2000. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:180–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drawz PE, Miller RT, Singh S, et al. Impact of a chronic kidney disease registry and provider education on guideline adherence - a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:62. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenz O, Mekala DP, Patel DV, et al. Barriers to successful care for chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2005;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens PE, O'Donoghue DJ, de Lusignan S, et al. Chronic kidney disease management in the United Kingdom: NEOERICA project results. Kidney Int. 2007;72:92–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lusignan S, Chan T, Stevens P, et al. Identifying patients with chronic kidney disease from general practice computer records. Fam Pract. 2005;22:234–41. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White SL, Polkinghorne KR, Cass A, et al. Limited knowledge of kidney disease in a survey of AusDiab study participants. Med J Aust. 2008;188:204–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Razavian M, Heeley EL, Perkovic V, et al. Cardiovascular risk management in chronic kidney disease in general practice (the AusHEART study). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1396–402. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137–47. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management. London (UK): 2014. . [accessed 2016 July 15]. Available: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182.

- 18.Chronic kidney disease (CKD) management in general practice (2nd ed.). Melbourne (AU): Kidney Health Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin A, Hemmelgarn B, Culleton B, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease. CMAJ. 2008;179:1154–62. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3 doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kötter T, Blozik E, Scherer M. Methods for the guideline-based development of quality indicators - a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2012;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganz GMF. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease: Rationale, development, and implementation. BCMJ. 2005; 47:292–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.2016/17 General Medical Services (GMS) contract Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). United Kingdom: BMA/NHS Employers/NHS England; 2016. . [accessed 2016 July 15]. Available: www.nhsemployers.org/~/media/Employers/Documents/Primary%20care%20contracts/QOF/2016-17/2016-17%20QOF%20guidance%20documents.pdf.

- 24.Pan-Canadian primary health care indicator update. Toronto: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spertus JA, Eagle KA, Krumholz HM, et al. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association methodology for the selection and creation of performance measures for quantifying the quality of cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2005;111:1703–12. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157096.95223.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.To T, Guttmann A, Lougheed MD, et al. Evidence-based performance indicators of primary care for asthma: a modified RAND Appropriateness Method. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:476–85. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tu K, Mitiku TF, Ivers NM, et al. Evaluation of Electronic Medical Record Administrative data Linked Database (EMRALD). Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:e15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu K, Widdifield J, Young J, et al. Are family physicians comprehensively using electronic medical records such that the data can be used for secondary purposes? A Canadian perspective. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:67. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0195-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu K, Manuel D, Lam K, et al. Diabetics can be identified in an electronic medical record using laboratory tests and prescriptions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:431–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivers NM, Tu K, Francis J, et al. Feedback GAP: study protocol for a cluster-randomized trial of goal setting and action plans to increase the effectiveness of audit and feedback interventions in primary care. Implement Sci. 2010;5:98. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tu K, Mitiku T, Guo H, et al. Myocardial infarction and the validation of physician billing and hospitalization data using electronic medical records. Chronic Dis Can. 2010;30:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tu K, Mitiku T, Lee DS, et al. Validation of physician billing and hospitalization data to identify patients with ischemic heart disease using data from the Electronic Medical Record Administrative data Linked Database (EMRALD). Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:e225–8. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ivers N, Pylypenko B, Tu K. Identifying patients with ischemic heart disease in an electronic medical record. J Prim Care Community Health. 2011;2:49–53. doi: 10.1177/2150131910382251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Litvin CB, Ornstein SM. Quality indicators for primary care: an example for chronic kidney disease. J Ambul Care Manage. 2014;37:171–8. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukuma S, Shimizu S, Niihata K, et al. Development of quality indicators for care of chronic kidney disease in the primary care setting using electronic health data: a RAND-modified Delphi method. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vest BM, York TRM, Sand J, et al. Chronic kidney disease guideline implementation in primary care: a qualitative report from the TRANSLATE CKD Study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:624–31. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.05.150070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Litvin CB, Nietert PJ, Wessell AM, et al. Recognition and management of CKD in primary care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;37:646–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.