Abstract

Combinations of growth factors synergistically enhance tissue regeneration, but typically require sequential, rather than co-delivery from biomaterials for maximum efficacy. Polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM) coatings can deliver multiple factors without loss of activity; however, sequential delivery from PEM has been limited due to interlayer diffusion that results in co-delivery of the factors. This study shows that addition of a biomimetic calcium phosphate (bCaP) barrier layer to a PEM coating effectively prevents interlayer diffusion and enables sequential delivery of two different biomolecules via direct cell access. A simulated body fluid method was used to deposit a layer of bCaP followed by 30 bilayers of PEM made with poly-L-Lysine (+) and poly L-Glutamic acid (−) (bCaP-PEM). Measurements of MC3T3-E1 proliferation and viability over time on bCaP-PEM were used to demonstrate the sequential delivery kinetics of a proliferative factor (fibroblast growth factor -2 (FGF-2)) followed by a cytotoxic factor (antimycin A, AntiA). FGF-2 and AntiA both retained their bioactivity within bCaP-PEM, yet no release of FGF-2 or AntiA from bCaP-PEM was observed when cells were absent indicating a cell-mediated, local delivery process. Biomedical products that would benefit from highly localized, sequential delivery of multiple biomolecules activated by cell degradation to avoid off-target effects can benefit from this coating technique.

Keywords: biomaterial, multifactor delivery, calcium phosphate, polyelectrolyte multilayer films, fibroblast growth factor-2

INTRODUCTION

Multi-component biomaterial drug delivery systems are being developed to guide multiple, critical aspects of the tissue regeneration process, including: infection control1, progenitor cell recruitment and migration2 and cell proliferation and differentiation3. These bodily processes are governed by the timely release and exposure to multiple biologically active factors.4,5 Growth factors have different effects on tissue regeneration depending on the developmental stage of the healing process at which they are present.6 Since growth factors may oppose each other if given at the same time (e.g. proliferative cues at the same time as differentiation cues), the sequence of delivery is important and must be considered to optimize biological activity and healing. The biological understanding of cell instructive cues is expanding and thus new drug delivery systems are needed to better control the release of multiple therapeutic agents at optimized physiological doses, ideally with specific spatiotemporal patterns.7

Several different types of delivery systems for multiple factors have already been developed as potential therapeutics for wound healing/infection, bone, cartilage, muscle, teeth and cancer, and have shown some efficacy in vitro 1,8–11 and in vivo 12–14; however, their success has been limited. One drawback of systems such as microspheres,1 nanoparticles,9 and hydrogels10,13 is that often there is a co-delivery of multiple factors due to uncontrolled diffusion through the biomaterial that can impede biological activity8. Diffusive mixing of multiple factors adsorbed at different times is also feature of layer-by-layer polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM) films and occurs due to diffusion of the polyelectrolytes and adsorbed factors during exponential growth of hydrophilic polyelectrolyte multilayer coatings.15 As the coating is exposed to a polyanion (−) solution, the polycation (+) within the coating will diffuse to the surface allowing for more binding sites for the polyanion. Vice versa will occur during the next step when the polycation solution is being applied. During the rearrangement of the PEM molecules, any incorporated factor will also be rearranged resulting in a blended architecture lacking controlled order.16 A recently reported strategy for overcoming co-delivery due to diffusion within PEM films12,15,16 is the introduction of a laponite clay barrier layer.17,18 The clay barrier layer changed the release profile of the second factor from burst to continuous; however, the first and second factor were still co-delivered initially; thus, true sequential delivery was not achieved.17

The novelty of the present study is the introduction of a biomimetic calcium phosphate (bCaP) barrier layer to a PEM coating made of polyamino acids. Calcium phosphate was chosen because of its biocompatibility, low cost, and ease of manufacture. It was hypothesized that if the bCaP layer could prevent interlayer diffusion of multiple factors, then controlled, sequential delivery would be achieved. This study describes the fabrication methods and characterization of bCaP-PEM coatings and the in vitro assessment of the delivery kinetics of two factors with opposing activity (proliferative vs. cytotoxic) delivered from bCaP-PEM coatings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design of Sequential Delivery System

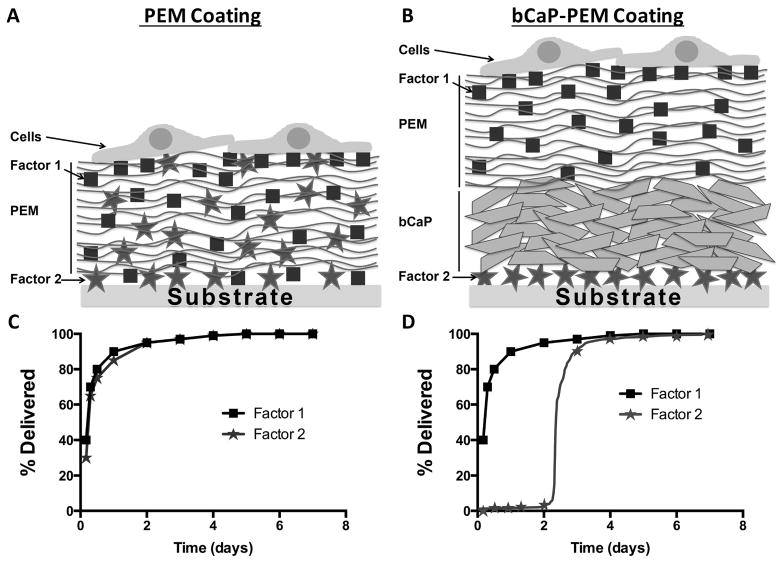

To prevent interlayer diffusion of multiple factors that occurs with a PEM-only coating (schematically shown in Fig. 1A), a bCaP layer was deposited as a barrier above factor 2 and below a PEM coating containing factor 1 (schematically shown in Fig. 1B). The PEM layer is used as a reservoir for adsorption of the first factor (shown as squares) and the second factor, to be accessed later, is adsorbed prior to bCaP deposition. The diffusion of two different factors that occurs in PEM only coatings results in co-delivery of the factors (Fig. 1C), therefore it was hypothesized that introducing bCaP into the delivery system to block diffusion would result in sequential delivery of multiple factors (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of (A) interlayer diffusion of Factors 1 and 2 in a PEM only coating, compared to (B) prevention of interlayer diffusion of Factors 1 and 2 with the addition of bCaP to the PEM coating. Theoretical (C) co- and (D) sequential delivery profiles of two different bioactive factors (shown as squares and circles) from PEM only coating vs. PEM with a biomimetic bCaP barrier.

Material Fabrication

Preparation of bCaP coated disks for cell culture

A two-step simulated body fluid (SBF) biomimetic CaP coating (bCaP) protocol developed for metal substrates19–21 and modified for plastic disks by our laboratory as described earlier22 was utilized to produce bCaP. For these studies, 22 mm diameter polystyrene disks (NUNC, Rochester, NY) that fit exactly into 12 well cell culture dishes were sandblasted on both sides with 240-grit aluminum oxide powder (Ivoclar Vivadent, Amherst, NY) to roughen the surface for coating adhesion. The sandblasted tissue culture plastic disks (TCPsb) were cleaned by ultrasonication in water and UV-sterilized prior to bCaP deposition. The bCaP coating procedure involved immersion in two different solutions over a two day process. Solution A results in a thin amorphous layer of CaP and Solution B, with less inhibitors of apatite formation, results in the formation of mature apatite crystals as a second layer above the amorphous layer. After drying the coated disks through a series of graded alcohol solutions, the samples were stored in a desiccator until further use.

Polyelectrolyte multilayer application

The layer-by-layer PEM application process was automated by the use of a histology-staining machine (Varistain 24-4, Thermo Shandon, Loughborough, UK) with custom designed sample holders. The PEM coatings were applied to TCPsb and/or the bCaP-coated disks by alternate 10 min immersions into 1 mg/ml poly-L-Glutamic acid (PLGlut) or 1 mg/ml poly-L-Lysine (PLLys) in saline (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), with seven saline rinses between each for a total of 30 bilayers (PEM30).

Factor application

A proliferative factor, recombinant human FGF-2 (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and a cytotoxic factor.23,24, Antimycin A (AntiA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were used. AntiA was adsorbed directly on the disks before bCaP deposition (10μl of 40mM AntiA in ethanol and allowed to dry before rinsing: 213 μg/disk). AntiA coated disks were rinsed 3x with saline before bCaP or PEM application and the low solubility of AntiA minimized desorption. FGF-2 stimulates cell proliferation at low doses 8,25–27 and is cytotoxic at high doses. Dose response studies were conducted to determine an appropriate dose of FGF-2 adsorbed as an outer layer that led to proliferation and not cytotoxicity. The bCaP-PEM30 coated disks were placed in 0.4 ml of saline containing 375 ng/ml FGF-2 for 1hr to adsorb FGF-2 and then rinsed 3x with saline. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was performed on the FGF-2 solutions before and after binding and determined that approximately 80% of FGF-2 bound to the coated disks: actual adsorbed dose ~120 ng/22 mm diameter disk.

Characterization

Scanning Electron Microscopy

The microscopic morphology of three different batches of coated disks was characterized using SEM (JSM - 5900LV, Jeol USA Inc. Peabody, MA). Disks were cut in half, allowing the examination of the coating cross-section with measurements of the coating thickness in multiple locations.

Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

The elemental composition and Ca/P ratio of the bCaP coatings before and after PEM application were determined with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (FEI Teneo LVSEM and EDAX SDD EDS). The accelerating voltage was 10 kV and a depth of X-ray interaction of about 1 μm. At least 3–5 locations on bCaP and bCaP-PEM coated disks from 3 different batches were analyzed at 1000X magnification for area scans, and 10,000X for point analyses. Values were compared to those obtained from a hydroxyapatite powder (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

The crystal structure of the bCaP coating before and after PEM application was determined with an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D8 Advanced, Bruker AXS) using Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 44 mA over a 2θ range of 5–75° at a scan rate of 2°/min in steps of 0.02°. Sufficient material was scraped from six representative disks to produce powder samples and compared to the hydroxyapatite powder and previously published patterns.22

Bioactivity and Delivery Kinetics

Cell-Culture Assays for Evaluation of bCaP-PEM Delivery Kinetics

MC3T3-E1 mouse calvarial osteoprogenitor cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in alpha-Minimal Essential Medium (α-MEM, No. 12571, Gibco BRL, Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate (penstrep). Passages 10–30 were routinely used. The bCaP-PEM30 and/or PEM30 coated disks were sterilized prior to cell culture and before FGF-2 application by exposure to UV light for 10 min to each side of the disks. The opaque bCaP coating protected the AntiA activity by blocking the damaging UV light from reaching the AntiA adsorbed below. Disks were then placed into 12-well tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and equilibrated in 1 ml α-MEM medium without FBS or penstrep for 30–45 min. MC3T3-E1s were seeded at 4 × 104 cells/cm2 on the disks in complete medium and were cultured on the coated disks for 4h, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 days, (medium changed on day 3). The following groups were tested: TCPsb coated with PEM30, AntiA-PEM30, bCaP-PEM30, bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2, AntiA-bCaP-PEM30, AntiA-bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2.

Proliferative and cytotoxic effects of the factors embedded in the coatings on the cells were evaluated over time to determine initial diffusion through PEM only coatings and blocking effects of the bCaP layer. Two proliferation assays were initially used for dose response studies of single factors, i.e. the non-terminal Alamar Blue (resazurin, Sigma Aldrich) assay or the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS, tetrazolium compound) assay. However, they were not able to accurately discriminate proliferative effects of FGF-2 from cytotoxic effects of AntiA in the two factor coatings because metabolic activity slows when cells proliferate well and become confluent or can slow due to cytotoxic effects. The dsDNA assay (Quant-iT PicoGreen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) which can be an excellent measure of total cell number could not be used due to the interference of the PEM component poly L lysine with the assay. Initially bovine serum albumin was used as a model protein to determine release kinetics as measured by the micro bicinchoninic acid assay BCA kit, however both PEM components were also detected by the BCA kit thus preventing accurate measurements of release of the protein component. LIVE® staining (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was thus determined to be the best method and was used following the manufacturer’s protocol. The DEAD® stain could not be used due to interference with the bCaP coating autofluorescence at that wavelength. Prior to LIVE® staining, disks were transferred to new wells and washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS); LIVE® staining was applied and cells were imaged after 30 min incubation and washing at 100X magnification. A plate reader was initially used to determine average intensities for each well, however the frequent presence of bubbles under the bCaP-PEM coated disk inserts led to variable background measurements. The most accurate and reliable data was obtained by image analysis of 3 images per well with 3 replicates. Average percent fluorescently labelled area of 3 images taken per well was determined by standardized thresholding and ImageJ analysis. Percent cell death was calculated by subtracting the average percent live stained area of the AntiA group normalized by its respective AntiA-negative control from 100%. All experiments were repeated at least twice.

To determine if the bCaP or PEM coating process washed off or inactivated the AntiA, AntiA coated disks (N=4) underwent the “PEM” processing but without PEM molecules present, i.e. disks were subjected to the automated dip procedure that normally would apply the polyelectrolytes but only saline was used. Similarly disks with AntiA were subjected to “bCaP” processing but without the ions present, i.e. the disks were submerged in MilliQ water at the higher temperatures for SBF (rather than solution A or B). AntiA adsorbed to sandblasted disks (213 μg/disk with 3x saline rinses, n = 4) without processing was used as a positive control. Sandblasted disks with no AntiA were used as the negative control. MC3T3-E1s were plated on the disks at 4 × 104 cells/cm2. Cytotoxic effects of the AntiA on the cells were evaluated with image analysis of LIVE® staining after 24 h of culture.

Release studies

Coated disks (with and without AntiA, with and without FGF-2) were incubated in 1 ml complete culture medium without cells for 1 or 3 days. Release medium was collected at each time point and immediately frozen at −20°C. A bioactivity assay was used to detect release of the factors into the media as follows. MC3T3-E1 cells were plated in a 96-well tissue culture plate (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at 2.5 × 103 cells/cm2. After 48 h of culture, 50% of the media was removed and replaced with thawed release medium. After an additional 24 h of culture, LIVE® staining was used. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) testing for FGF-2 release was performed.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significances were determined by unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-tests, with a p-value ≤ 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of the Biomimetic Calcium-Phosphate Coating

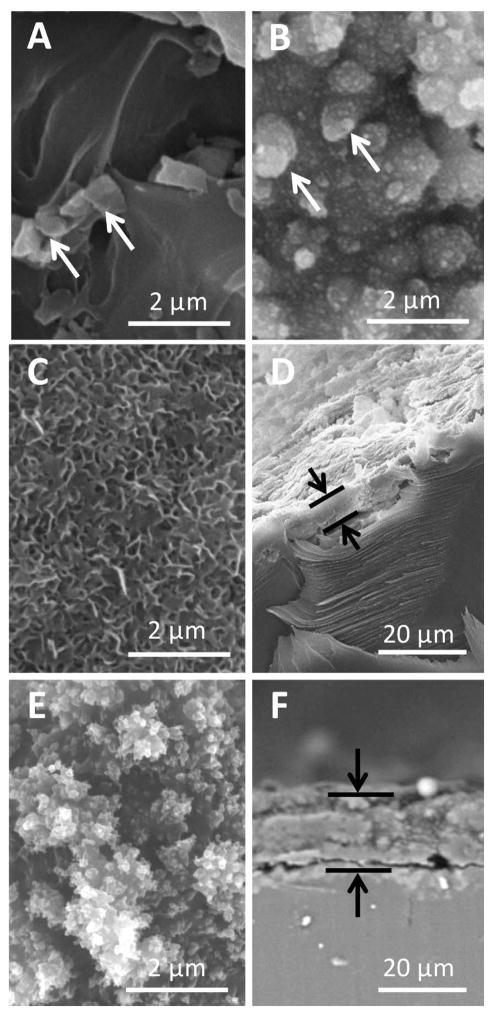

SEM microscopy with EDS point analysis revealed some embedded aluminum oxide sandblasting residue on the TCPsb prior to bCaP or PEM deposition (Fig. 2A, white arrows) that was still detectable after PEM30 coating (Fig. 2B, white arrows). The densely packed, nano-crystals of bCaP completely coated the TCPsb resulting in an average layer thickness of 5.8 ± 1.8 μm (Fig. 2C, Fig. 2D). The bCaP crystals became indistinguishable after PEM30 application with an average bCaP-PEM30 coating thickness of 16.3 ± 2.2 μm (Fig. 2E, F).

Figure 2.

SEM images of (A) TCPsb, (B) TCPsb-PEM30, (C) TCPsb-bCaP, (D) TCPsb-bCaP cross-section, (E) TCPsb-bCaP-PEM30, (F) TCPsb-bCaP-PEM30 cross-section. White arrows point to embedded sandblasting remnants (aluminum oxide). Black arrows indicate coating thickness; bCaP thickness = 5.8 ± 1.8 μm and bCaP-PEM30 thickness = 16.3 ± 2.2 μm.

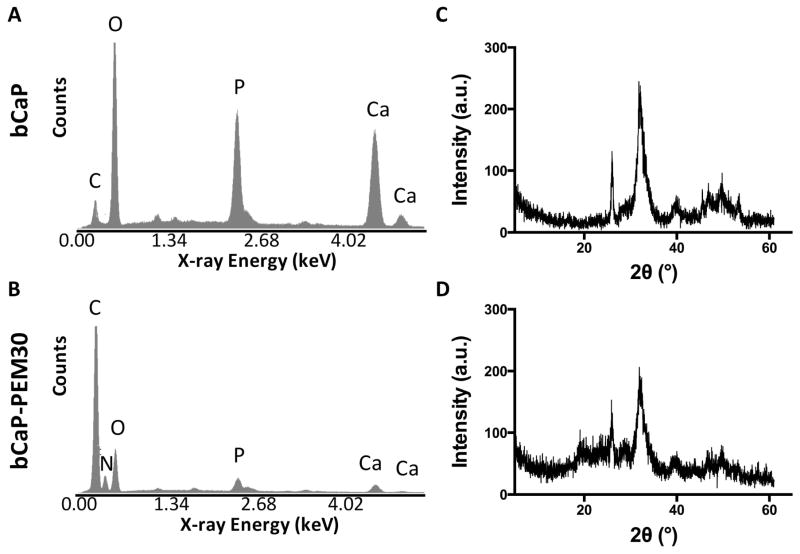

EDS revealed Ca/P atomic ratios of 1.95 ± 0.12 for bCaP before (Fig. 3A) and 1.52 ± 0.50 after PEM30 adsorption (Fig. 3B), which is similar to the Ca/P ratio of a standard hydroxyapatite powder, 1.71 ± 0.04. EDS analysis of bCaP-PEM30 also confirmed the presence of carbon and nitrogen due to the polyelectrolyte layers. The crystal structure of the bCaP was identified as poorly crystalline/nanocrystallline hydroxyapatite by XRD (Fig. 3C). The term poorly crystalline/nanocrystalline is used due to the observed peak broadening.22 After PEM adsorption, the bCaP crystal structure became less crystalline as evident by even further peak broadening (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

EDS analysis of the bCaP deposited on TCPsb (A) before, and (B) after PEM30 adsorption, revealed Ca/P atomic ratios of 1.95 ± 0.12 and 1.52 ± 0.50 respectively, not statistically different from the hydroxyapatite powder (1.71 ± 0.04) nor each other. (C) XRD identified the composition of the bCaP coating as poorly crystalline/nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite. (D) After PEM adsorption the bCaP became less crystalline.

Bioactivity and Delivery Kinetics

Coating procedure does not inactivate AntiA

To ensure the coating procedure did not inactivate the AntiA, cytotoxicity of adsorbed AntiA was evaluated after multiple saline rinses or when treated with MilliQ water and heat similar to the PEM and bCaP coating procedures. All AntiA coated disks, regardless of rinsing procedures, resulted in significant MC3T3-E1 cell death within 24 h of culture as compared to the negative control, TCPsb with no AntiA (**** p < 0.0001). Furthermore there were no statistically significant differences between the processed AntiA disks compared to the fresh/normal AntiA indicating AntiA retains its cytotoxic activity during coating application (data available from author upon request).

bCaP-PEM inhibits interlayer diffusion

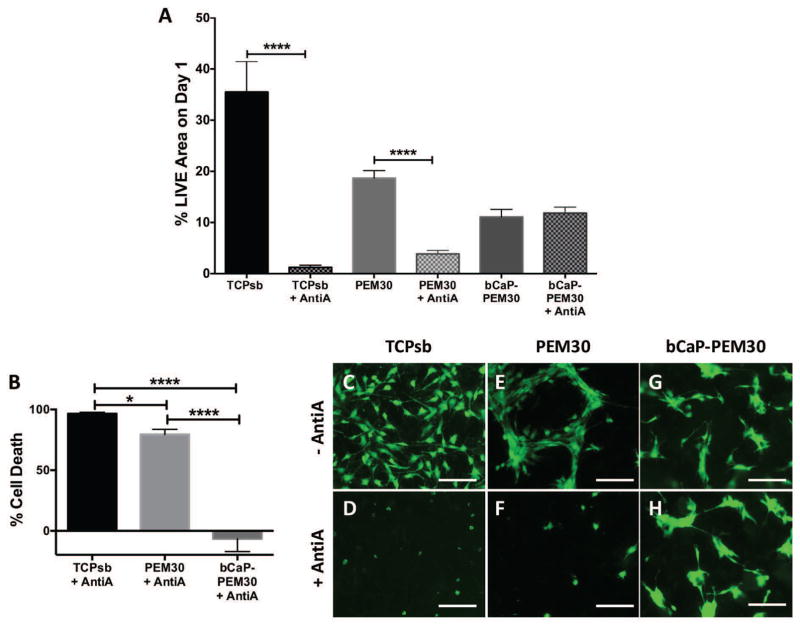

MC3T3-E1s cultured for one day on TCPsb-only controls coated with AntiA resulted in a significant drop in % LIVE® stained area as compared to no AntiA (TCPsb vs. TCPsb+AntiA, Fig. 4A, **** p ≤ 0.0001). This equated to 96.6 ± 1.2 % cell death (Fig. 4B) and was visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4C vs. Fig. 4D). MC3T3-E1 cells cultured for one day on AntiA-PEM30 coated TCPsb led to a significant drop in % LIVE® stained area as compared to its PEM-only control (PEM30 vs. AntiA-PEM30, Fig. 4A, *** p ≤ 0.001). This equated to 79.5 ± 4.2 % cell death (Fig. 4B) and was visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4E vs. Fig. 4F). MC3T3-E1s cultured for one day on AntiA-bCaP-PEM30 showed no statistical difference in % LIVE® stained area compared to its bCaP-PEM-only control (Fig. 4A) and this equated to −6.7 ± 10.6 % cell death (Fig. 4B). Cell culture viability differences can be seen in Fig. 4G vs. Fig. 4H. Percent cell death is negative for this group because the day 1 LIVE® staining on the AntiA-bCaP-PEM30 was consistently slightly higher than on the bCaP-PEM30 control, (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Live staining on day 1 demonstrates diffusion of a cytotoxic compound through PEM only and a blocking effect of bCaP-PEM (A) Day 1 % LIVE stained area of MC3T3-E1s cultured on AntiA with no coating compared to its TCPsb-only control, AntiA embedded under PEM30 compared to its PEM-only control, and AntiA embedded under bCaP-PEM30 compared to a bCaP-PEM-only control, (*** p value ≤ 0.001, **** p value ≤ 0.0001). (B) LIVE® staining expressed inversely as % cell death for AntiA, AntiA-PEM30, and AntiA-bCaP-PEM30 respectively relative to their viability on their respective controls, (* p value ≤ 0.05, *** p value ≤ 0.001, **** p value ≤ 0.0001). Fluorescent images of LIVE® staining of MC3T3-E1s cultured on (C) TCPsb vs. (D) TCPsb coated with AntiA, (E) PEM30 vs. (F) AntiA-PEM30, and (G) bCaP-PEM30 vs. (H) AntiA-bCaP-PEM30. Scale bar = 250 μm.

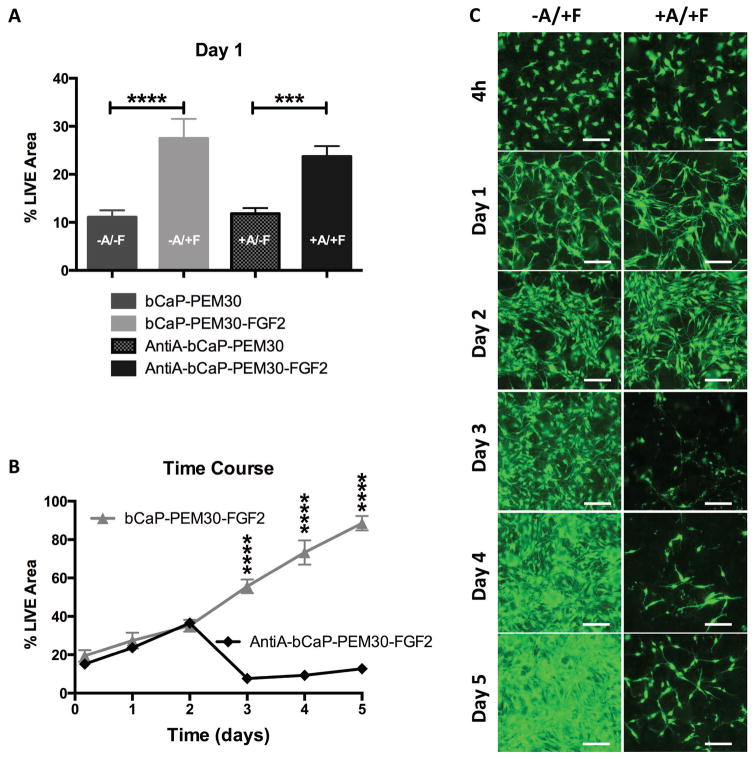

Delivery of biologically active factors from bCaP-PEM30

Biologically active FGF-2 was successfully delivered from bCaP-PEM30 (bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2) coated disks as indicated by the significant increase in LIVE® staining on day 1 and the remaining time points in the study, as compared to its bCaP-PEM-only control (bCaP-PEM30) (Fig. 5A, B). Active AntiA was successfully delivered from bCaP-PEM30 coated disks as evident by the significant decrease in MC3T3-E1 proliferation on days 2–4 as compared to its bCaP-PEM-only control (bCaP-PEM30) (Fig. 5C and Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

(A) % LIVE® stained area of MC3T3-E1s cultured on TCPsb coated with bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 increases throughout culture as compared cells on bCaP-PEM30 indicating active FGF-2 is delivered to cells. (B) Fluorescent images of day 1 LIVE® staining of MC3T3-E1s cultured on bCaP-PEM30 (−A/−F) versus bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 (−A/+F). (C) % LIVE® stained area of MC3T3-E1s cultured on TCPsb coated with AntiA-bCaP-PEM30 resulted in a significant decrease in proliferation on days 2–4 as compared cells on bCaP-PEM30. (D) Fluorescent images of day 3 LIVE® staining of MC3T3-E1s cultured on bCaP-PEM30 (−A/−F) versus AntiA-bCaP-PEM30 (+A/−F). Scale bar = 250 μm, (* p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001).

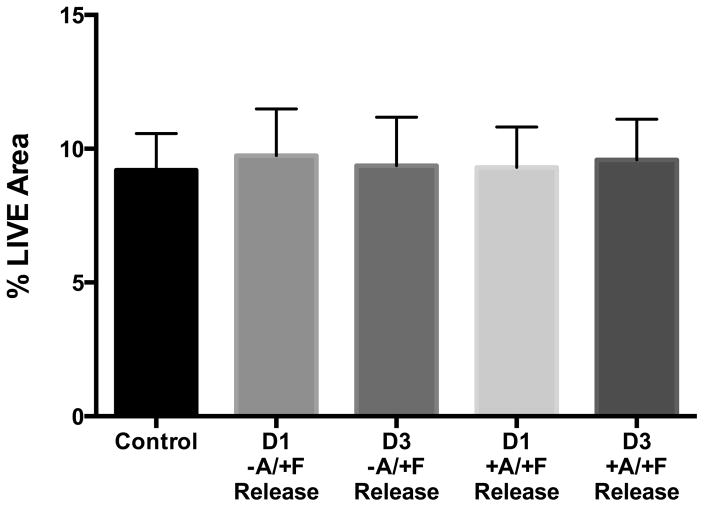

Factor release not detected from bCaP-PEM30 without cells

Release medium collected after 1 or 3 days incubation of bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 coated disks in medium without cells had no significant proliferative effect when added to MC3T3-E1s as compared to control medium, indicating negligible FGF-2 release from the (Fig. 6, −A/+F group). Release medium collected after 1 or 3 days incubation of AntiA-bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 coated disks in medium without cells had no cytotoxic effect when added to MC3T3-E1 cultures as compared to control medium or release medium from the group with FGF-2 indicating no AntiA release without cells being present on the coatings over these time points (Fig. 6, +A/+F group).

Figure 6.

% LIVE ® staining of cells cultured in day 1- or day 3-release medium collected from bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 (−A/+F) or AntiA-bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 (+A/+F) coated disks incubated at 37°C without cells indicating non-detectable FGF-2 or AntiA release.

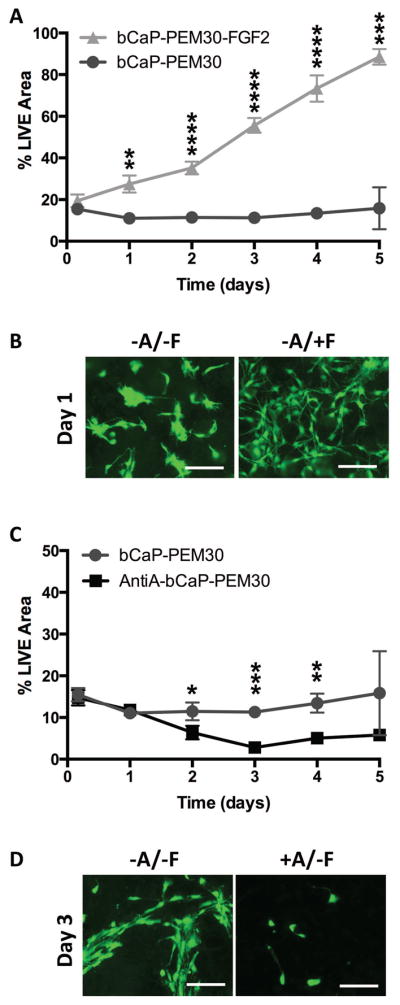

Sequential delivery of multiple factors from bCaP-PEM30

The first factor, FGF-2 (150 ng/disk) was accessed immediately by cells on the bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 coated disks with or without embedded AntiA as evident by the significant increase in day 1 LIVE® staining of the MC3T3-E1s on the coatings with FGF-2 compared to their controls lacking FGF-2, (Fig. 7A). Despite the presence of Anti-A within the coatings, no differences in LIVE® stained area were observed between cells cultured on AntiA-bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 and control disks without AntiA (bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2) for time points 4h, day 1 and day 2 indicating AntiA was successfully blocked by bCaP-PEM30 (Fig. 7B, 7C). By day 3 a significant decrease in LIVE® staining between groups was observed indicating cells had accessed AntiA, (Fig. 7B, 7C). At day 4, the cells that survived the AntiA exposure started to recover as shown by increased cell numbers (Fig. 7C), which is even more apparent on day 5.

Figure 7.

(A) % LIVE® stained area of MC3T3-E1 cells after one day of culture compared for all groups tested (*** p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001). (B) Time course of MC3T3-E1s cultured on bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 and AntiA-bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2. By day 3 a significant decrease in LIVE® staining was observed between groups indicating sequential AntiA delivery, (**** p ≤ 0.0001). (C) Images of LIVE stained MC3T3-E1 cells after culture on bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 (−A/+F) vs AntiA-bCaP-PEM30-FGF-2 (+A/+F) corresponding to the time points of the graph. Scale bar = 250 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this study the development of a novel biomimetic calcium phosphate/polyelectrolyte multilayer coating that can deliver two different factors in a sequential manner is reported. Sequential delivery is necessary in order to maximize the effects of some combinations of growth factors that have different and conflicting cell directives; such as, FGF-2 and BMP-2 that stimulate proliferation and differentiation, respectively, and lead to inhibition of osteoblast differentiation when co-delivered 8. Sequential delivery systems could also be utilized in cell reprogramming experiments which cells are brought through a de-differentiation process followed by differentiation to another cell type. Sequential delivery systems might also be useful for influencing initial acute inflammatory events at the cell/biomaterial interface such as recruitment of monocytes and macrophages 28 that are later instructed to switch phenotype to a regenerative type by delivery of particular factors. The two day delay between first and second factors observed in the present studies is an appropriate time for guiding these multi-step biological activities.

PEM was selected as the base material for the development of a sequential delivery system because PEM is one of the few systems that maintains the bioactivity of incorporated factors. Because bioactive molecules are directly integrated in the architecture of the film based on electrostatic interactions and do not require covalent bonding,29,30 protein secondary structures remain close to their native form and this retains their biological activity.31 Increasing the number of PEM bilayers is a means to increase the amount of growth factor that can be adsorbed into the PEM portion of the system 32. However, there are diffusion and molecular rearrangement issues of PEM-only films that prevent distinct sequential delivery of different factors from different layers. This was demonstrated by the immediate cell death observed when AntiA was embedded under 30-bilayers of PEM without the barrier layer (Fig. 6). Evidently AntiA diffused or rearranged during PEM build up, resulting in immediate access of the cells to the cytotoxic factor upon cell seeding. Thus PEM-only coatings, particularly those with exponential growth, are not suitable for multifactor delivery in which a delayed access to a second factor is desired. This shortcoming of PEM motivated the present research to modify the coating with a bCaP barrier layer to achieve sequential delivery.

Due to our long standing interest in FGF-2 effects on bone formation 8,27, FGF-2 was selected as one of the test molecules to evaluate bCaP-PEM delivery kinetics. Our previous studies showed very low doses of FGF-2 (5 ng or less) are needed for in vivo bone regeneration efficacy33 and that picogram levels of FGF-2 are effective for in vitro differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells8. The present study therefore utilized low doses of FGF-2. The release media collected after 1 or 3 days was expected to contain measurable amounts of FGF-2, but no FGF-2 was detected by standard ELISA testing. Release media added to cells also had no biological effects; yet cells cultured on the coatings responded with robust proliferation indicating FGF-2 was present and activity was retained. Inactivation of the FGF-2 adsorbed to the PEM surface coating is unlikely given the many previous studies that have demonstrated retention of activity of FGF-234 and other growth factors (e.g. BMP-234, vascular endothelial growth factor, etc35–37) in PEM coatings like those tested here. The bCaP-PEM delivery system is thus capable of a highly localized nature of growth factor delivery. This delivery system may help advance the in vivo application of molecules for genetic modification or factors that influence stem cell generation that could have dangerous side effects if delivered systemically or to adjacent healthy tissues.

The highly localized delivery mechanism of the bCaP-PEM system made analysis and demonstration of the kinetics of multi-factor delivery difficult. Since release of the compounds could not be measured it was necessary to use bioassays to measure cellular response. The combination of a cytotoxic compound (AntiA) and a proliferative compound (FGF-2) was selected to study the multifactor, cell-mediated delivery kinetics of the bCaP-PEM coating because the two compounds have opposite effects and thus their effects on cells could be distinguished from each other. Proliferation assays such as alamar blue or cell titer MTS that measure metabolic activity go up and then down in response to cells reaching confluency which was misinterpreted as cell access to the cytotoxic compound, thus they were not a reliable method. The pico green total DNA assay and the BCA assay also reacted unfavorably with PEM components. The opaque nature of the sandblasted tissue culture plastic disks with the bCaP prevented direct visualization of cells during the assays; thus standardized quantification of LIVE staining was eventually determined to be the best approach.

Alternate strategies for separating access to two different factors within PEM have been investigated. A slight delay of 6 hrs was observed when increasing the ratio of D- to L-enantiomer polyelectrolytes because D-enantiomer slows cellular degradation of the film.38 A longer delay of 25 h was achieved with the use of a covalently cross-linked poly(allylamine hydrochloride)(PAH)/poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) layer.16 A clay barrier layer was tried as a means to separate gentamycin antibiotic from BMP-2 delivery within a Poly β-amino ester/PAA PEM coating; yet burst release of the antibiotic with simultaneous, sustained release of BMP-2 was observed without a temporal delay.17 The two day delay provided by the bCaP-PEM layer is thus an advance relative to the previous publications. PEM only coatings are fragile and easily removed during implant placement due to their thin nanostructure. The addition of a highly textured bCaP layer to PEM overcomes this limitation and has previously been shown to increase stability of PEM coating up to 8 months in storage without cells.39

The mechanism by which the MC3T3-E1 cells degrade the bCaP to access the embedded second factor, AntiA, remains unclear. Our previous studies indicated that after 21 days of MC3T3-E1 culture on a bCaP-only coating, the bCaP remained nearly intact.22 Given that the MC3T3-E1 osteoprogenitor cells are not capable of physically degrading the bCaP layer, it is speculated that the presence of cracks in the coating observed by SEM and possible nanoporosity40 allows cell processes of MC3T3-E1s to push through small openings in the coating to access the AntiA. The AntiA may also slowly diffuse out of the cracks. It is known that osteoblasts cultured in three-dimensions 41 or on the surface of bone will form long processes.42,43 From the images in the present studies, it is evident the MC3T3-E1s have long processes in two-dimensions along the surface of the coating; it is therefore speculated that these processes also extend down through cracks in the coating.

Monocytes/macrophages are one of the first cell types that would interact with the coating in vivo 44, and are known to be capable of rapid resorption of PLLys-PLGlut PEM materials 45. Future work will focus on understanding how the kinetics of cellular access to factors within bCaP-PEM coatings differ based on the cell type interacting with the material. In addition, it is known that chemical and physical changes to the coating composition can alter kinetics of biomolecule release from bCaP 46 and thus could be investigated as a means to tune the kinetics of cell access to adsorbed factors.

CONCLUSION

The addition of a biomimetic calcium-phosphate barrier layer to a poly-L-lysine/poly-L-glutamic acid polyelectrolyte multilayer delivery system prevents unwanted interlayer diffusion of embedded factors within PEM-only coatings and enables localized, cell-mediated sequential delivery of multiple factors. Sequential delivery of a proliferative factor, FGF-2, followed by a cytotoxic factor, AntiA was demonstrated. Both factors retained their bioactivity through processing and during in vitro culture. The addition of the bCaP layer to the PEM design resulted in delayed access of the embedded AntiA for 3 days when cultured with MC3T3-E1 cells. This technology can be utilized in multiple applications where a highly localized application of two or more biomolecules is desired, administered with a sequential delivery profile.

Acknowledgments

Funding provided from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) R01DE021103. The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support of Li Zhu who conducted the ELISA assays.

References

- 1.Jiang B, Zhang G, Brey EM. Dual delivery of chlorhexidine and platelet-derived growth factor-BB for enhanced wound healing and infection control. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(2):4976–84. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.La WG, Jin M, Park S, Yoon HH, Jeong GJ, Bhang SH, Park H, Char K, Kim BS. Delivery of bone morphogenetic protein-2 and substance P using graphene oxide for bone regeneration. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9(Suppl 1):107–16. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S50742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su J, Xu H, Sun J, Gong X, Zhao H. Dual delivery of BMP-2 and bFGF from a new nano-composite scaffold, loaded with vascular stents for large-size mandibular defect regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(6):12714–28. doi: 10.3390/ijms140612714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta M, Schmidt-Bleek K, Duda GN, Mooney DJ. Biomaterial delivery of morphogens to mimic the natural healing cascade in bone. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(12):1257–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vo TN, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Strategies for controlled delivery of growth factors and cells for bone regeneration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(12):1292–309. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. Developmental aspects of fracture healing and the use of pharmacological agents to alter healing. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2003;3(4):297–303. discussion 320–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen FM, Zhang M, Wu ZF. Toward delivery of multiple growth factors in tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31(24):6279–308. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn LT, Ou G, Charles L, Hurley MM, Rodner CM, Gronowicz G. Fibroblast growth factor-2 and bone morphogenetic protein-2 have a synergistic stimulatory effect on bone formation in cell cultures from elderly mouse and human bone. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(10):1170–80. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee AL, Wang Y, Cheng HY, Pervaiz S, Yang YY. The co-delivery of paclitaxel and Herceptin using cationic micellar nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2009;30(5):919–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim SM, Oh SH, Lee HH, Yuk SH, Im GI, Lee JH. Dual growth factor-releasing nanoparticle/hydrogel system for cartilage tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2010;21(9):2593–600. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundararaj SC, Thomas MV, Peyyala R, Dziubla TD, Puleo DA. Design of a multiple drug delivery system directed at periodontitis. Biomaterials. 2013;34(34):8835–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah NJ, Macdonald ML, Beben YM, Padera RF, Samuel RE, Hammond PT. Tunable dual growth factor delivery from polyelectrolyte multilayer films. Biomaterials. 2011;32(26):6183–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons CA, Alsberg E, Hsiong S, Kim WJ, Mooney DJ. Dual growth factor delivery and controlled scaffold degradation enhance in vivo bone formation by transplanted bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2004;35(2):562–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Cao L, Shansky J, Wang Z, Mooney D, Vandenburgh H. Minimally invasive approach to the repair of injured skeletal muscle with a shape-memory scaffold. Mol Ther. 2014;22(8):1441–9. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picart C, Mutterer J, Richert L, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Lavalle P. Molecular basis for the explanation of the exponential growth of polyelectrolyte multilayers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(20):12531–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202486099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood KC, Chuang HF, Batten RD, Lynn DM, Hammond PT. Controlling interlayer diffusion to achieve sustained, multiagent delivery from layer-by-layer thin films. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(27):10207–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602884103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min J, Braatz RD, Hammond PT. Tunable staged release of therapeutics from layer-by-layer coatings with clay interlayer barrier. Biomaterials. 2014;35(8):2507–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salama A, El-Sakhawy M. Preparation of polyelectrolyte/calcium phosphate hybrids for drug delivery application. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;113:500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrere F, van Blitterswijk C, de Groot K, Layrolle P. Nucleation of biomimetic Ca-P coatings on ti6A14V from a SBF x 5 solution: influence of magnesium. Biomaterials. 2002;23(10):2211–20. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrere F, van Blitterswijk C, de Groot K, Layrolle P. Influence of ionic strength and carbonate on the Ca-P coating formation from SBFx5 solution. Biomaterials. 2002;23(9):1921–30. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habibovic P, Barrere F, van Blitterswijk C, de Groot K, Layrolle P. Biomimetic Hydroxyapatite Coating on Metal Implants. J Am Ceram Soc. 2002;85(3):517–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg AJ, Liu Y, Advincula MC, Gronowicz G, Habibovic P, Kuhn LT. Fabrication and characterization of hydroxyapatite-coated polystyrene disks for use in osteoprogenitor cell culture. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2010;21(10):1371–87. doi: 10.1163/092050609X12517190417830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi EM. Magnolol protects osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells against antimycin A-induced cytotoxicity through activation of mitochondrial function. Inflammation. 2012;35(3):1204–12. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suh KS, Lee YS, Seo SH, Kim YS, Choi EM. Gold nanoparticles attenuates antimycin A-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2013;153(1–3):428–36. doi: 10.1007/s12011-013-9679-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes GL, Kostenuik PJ, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. Growth factor regulation of fracture repair. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(11):1805–15. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.11.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marie PJ. Fibroblast growth factor signaling controlling osteoblast differentiation. Gene. 2003;316:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00748-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ou G, Charles L, Matton S, Rodner C, Hurley M, Kuhn L, Gronowicz G. Fibroblast growth factor-2 stimulates the proliferation of mesenchyme-derived progenitor cells from aging mouse and human bone. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(10):1051–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsell R, Einhorn TA. The biology of fracture healing. Injury. 2011;42(6):551–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kong W, Wang LP, Gao ML, Zhou H, Zhang X, Li W, Shen JC. Immobilized bilayer glucose isomerase in porous trimethylamine polystyrene based on molecular deposition. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1994;11:1297–1298. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lvov Y, Haas H, Decher G, Moehwald H, Mikhailov A, Mtchedlishvily B, Morgunova E, Vainshtein B. Successive Deposition of Alternate Layers of Polyelectrolytes and a Charged Virus. Langmuir. 1994;10:4232–4236. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwinte P, Voegel JC, Picart C, Haikel Y, Schaaf P, Szalontai B. Stabilizing effects of various polyelectrolyte multilayer films on the structure of adsorbed/embedded fibrinogen molecules: An ATR-FTIR study. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105(47):11906–11916. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vodouhe C, Le Guen E, Garza JM, Francius G, Dejugnat C, Ogier J, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Lavalle P. Control of drug accessibility on functional polyelectrolyte multilayer films. Biomaterials. 2006;27(22):4149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charles LF, Woodman JL, Ueno D, Gronowicz G, Hurley MM, Kuhn LT. Effects of low dose FGF-2 and BMP-2 on healing of calvarial defects in old mice. Exp Gerontol. 2015;64:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson AM, Pilz-Allen C, Kolesnikova T, Mohwald H, Shchukin D. Growth factor release from polyelectrolyte-coated titanium for implant applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(3):1866–71. doi: 10.1021/am404849y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Facca S, Ferrand A, Mendoza-Palomares C, Perrin-Schmitt F, Netter P, Mainard D, Liverneaux P, Benkirane-Jessel N. Bone formation induced by growth factors embedded into the nanostructured particles. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7(3):482–5. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2011.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadiri A, Kuchler-Bopp S, Mjahed H, Hu B, Haikel Y, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Benkirane-Jessel N. Cell apoptosis control using BMP4 and noggin embedded in a polyelectrolyte multilayer film. Small. 2007;3(9):1577–83. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Facca S, Cortez C, Mendoza-Palomares C, Messadeq N, Dierich A, Johnston AP, Mainard D, Voegel JC, Caruso F, Benkirane-Jessel N. Active multilayered capsules for in vivo bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(8):3406–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908531107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benkirane-Jessel N, Lavalle P, Hubsch E, Holl V, Senger B, Haikel Y, Voegel JC, Ogier J, Schaaf P. Short-Time Tuning of the Biological Activity of Functionalized Polyelectrolyte Multilayers. Adv Func Mat. 2005;15(4):648–654. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schade R, Dutour Sikiric M, Liefeith K, Furedi-Milhofer H. Interaction of Cells with Organic-Inorganic Nanocomposite Coatings for Titanium Implants. Bioceram Dev App. 2011;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JS, Lu Y, Baer GS, Markel MD, Murphy WL. Controllable protein delivery from coated surgical sutures. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2010;20:8894–8903. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murshid SA, Kamioka H, Ishihara Y, Ando R, Sugawara Y, Takano-Yamamoto T. Actin and microtubule cytoskeletons of the processes of 3D-cultured MC3T3-E1 cells and osteocytes. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25(3):151–8. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gohel AR, Hand AR, Gronowicz GA. Immunogold localization of beta 1-integrin in bone: effect of glucocorticoids and insulin-like growth factor I on integrins and osteocyte formation. J Histochem Cytochem. 1995;43(11):1085–96. doi: 10.1177/43.11.7560891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gronowicz G, Egan JJ, Rodan GA. The effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on the cytoskeleton of rat calvaria and rat osteosarcoma (ROS 17/2. 8) osteoblastic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1986;1(5):441–55. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650010509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leuschner F, Dutta P, Gorbatov R, Novobrantseva TI, Donahoe JS, Courties G, Lee KM, Kim JI, Markmann JF, Marinelli B, et al. Therapeutic siRNA silencing in inflammatory monocytes in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(11):1005–10. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lukasiewicz S, Szczepanowicz K, Blasiak E, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M. Biocompatible Polymeric Nanoparticles as Promising Candidates for Drug Delivery. Langmuir. 2015;31(23):6415–25. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b01226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang S. Hydroxyapatite Coatings for Biomedical Applications. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2013. [Google Scholar]