Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Individuals reporting a history of childhood violence victimization have impaired brain function. However, the clinical significance, reproducibility, and causality of these findings are disputed. We directly tested these research gaps.

METHOD

We tested the association between prospectively-collected measures of childhood violence victimization and cognitive functions in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood among 2,232 members of the UK E-Risk Study and 1,037 members of the New Zealand Dunedin Study, who were followed-up from birth until ages 18 and 38 years, respectively. We used multiple measures of victimization and cognition, and included comparisons of cognitive scores for twins discordant for victimization.

RESULTS

We found that individuals exposed to childhood victimization had pervasive impairments in clinically-relevant cognitive functions including general intelligence, executive function, processing speed, memory, perceptual reasoning, and verbal comprehension in adolescence and adulthood. However, the observed cognitive deficits in victimized individuals were largely explained by cognitive deficits that predated childhood victimization and by confounding genetic and environmental risks.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings from two population-representative birth cohorts totaling more than 3,000 individuals and born 20 years and 20,000 kilometers apart suggest that the association between childhood violence victimization and later cognition is largely non-causal, in contrast to conventional interpretations. These findings urge adopting a more circumspect approach to causal inference in the neuroscience of stress. Clinically, cognitive deficits should be conceptualized as individual risk factors for victimization as well as potential complicating features during treatment.

Individuals reporting a history of childhood violence victimization have impaired brain function(1–4). It is biologically plausible that exposure to extreme stressors, such as violence victimization, might harm brain function(5), particularly during periods of enhanced developmental plasticity(1). However, the interpretation and implications of these findings continue to fuel debate in neuroscience(6–8), clinical psychiatry(9; 10) and social policy(11; 12), because of unanswered questions about clinical significance, reproducibility, and causal inference.

With regard to clinical significance, it is unclear if research findings reflect clinically-relevant impairment of brain function in victimized children. This is unclear because neuroimaging methods that have been used to describe structural and functional brain differences in victimized individuals have, at present, only limited ability to predict everyday functioning and clinical outcomes(13). Neuropsychological assessments have greater reliability and predictive value(14; 15), and have shown that individuals with a history of childhood victimization have deficits in general intelligence and more specialized cognitive functions(16; 17). However, the origins of such cognitive deficits are unclear.

With regard to reproducibility, it is unclear if research findings reflect the effects of child victimization in the general population. This is unclear because sampling for research studies is often done in convenience groups (e.g., students answering research-study advertisements) or extreme groups (e.g., post-institutionalized young people) and on a small scale. Although these sampling strategies can be easily implemented, they may lead to non-reproducible results(18). Studies undertaken in selected samples may lead to non-generalizable results that are conditional upon sample-specific characteristics (low external validity)(19). Studies undertaken in small samples may produce spurious positive results (type-II error)(20).

With regard to causality, it is unclear if correlational findings from observational studies in humans reflect causal effects of child victimization on later brain function. This is unclear because victimized children often have pre-existing impairment in brain function and live in disadvantaged socio-economic conditions(21). Both factors provide alternative explanations for observed differences in brain function between victimized and non-victimized individuals(22; 23). Ruling out the effects of these confounding factors is necessary in order to infer causal effects of child victimization(24; 25). However, this has been difficult to achieve because extant research designs are typically cross-sectional, rely on retrospective recall of childhood victimization, and are limited to measurement of brain function at a single point in time in adolescence or adult life.

We addressed these questions in the current study. To understand the clinical significance of deficits in brain function associated with childhood victimization, we tested whether victimized children showed later global deficits in the intelligence quotient (IQ) or specific deficits in a wide range of cognitive functions associated with clinical and functional outcomes(14; 15; 26; 27). To ensure reproducibility of these observations, we tested whether the results were consistent across a range of prospectively-collected and validated measures of childhood victimization(28; 29) (including both broad poly-victimization (30) and specific types of victimization); across repeated cognitive assessments in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood(26); and across two large, population-representative cohorts in the UK and New Zealand, as described in Figure 1. Finally, to inform about causality, we took advantage of three methodological features (repeated cognitive assessments of Study members and their parents since before victimization; prospectively-collected information about family circumstances; and a twin-difference design) to test the alternative hypothesis that the associations between childhood victimization and later cognitive deficits have their origins in pre-existing and stable cognitive vulnerabilities and in confounding familial conditions.

Figure 1.

Timeline for the assessment of childhood victimization and cognitive functioning in the E-Risk Study and the Dunedin Study.

CTQ=Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; *executive function (CANTAB), processing speed (CANTAB); **executive function (CANTAB, WAIS-IV, WMS-III, Trail-B), processing speed (CANTAB, WAIS-IV), memory (CANTAB, WMS-III, Rey AVL), perceptual reasoning (WAIS-IV), verbal comprehension (WAIS-IV)

METHODS

Study 1: The Environmental-Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study

Sample

Participants were members of the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, which tracks the development of a birth cohort of 2,232 British children (Figure 1). Full details about the sample are reported elsewhere(31) and in the Supplement.

Childhood poly-victimization

Exposure to several types of victimization was assessed repeatedly when the children were 5, 7, 10, and 12 years of age and dossiers have been compiled for each child with cumulative information about exposure to domestic violence between the mother and her partner; frequent bullying by peers; physical maltreatment by an adult; sexual abuse; emotional abuse; and physical neglect. Following Finkelhor et al. (30), for each child, our cumulative index counts the types of victimization experienced during the first 12 years of life. Details about these measurements have been reported previously(29). In addition to the above prospective measures of victimization, we assessed recall of victimization through the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)(32) completed by Study members at the age–18 follow-up. Details about victimization measurements are available in the Supplement.

Cognitive testing

Figure 1 provides an overview of the cognitive testing in E-Risk, at ages 5, 12, and 18 years. Details are provided in the Supplement.

Statistical analyses

To test the associations between childhood victimization and cognitive measures, we ran a series of bivariate Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) linear regression models accounting for clustering of twins within families in SAS v9.3. To test if observed associations were accounted for by pre-existing cognitive vulnerabilities and non-specific effects of socio-economic disadvantage, we expanded the bivariate GEE models to include covariates for IQ at age 5 years and family socio-economic status (see Supplement), respectively. To test for significant attenuation of the association by the above covariates, we compared regression coefficients across models(33). To test if the results based on the experience of poly-victimization could be generalized to more extreme forms of victimization, we reran the above analyses using physical harm or physical neglect as independent variables. To test if the above results depended on victimization in infancy of toddlerhood, we ran a sensitivity analysis excluding 307 study members with evidence of victimization before age 5 years. To test whether the association between childhood victimization and cognitive functioning was accounted for by unobserved genetic or environmental heterogeneity, we tested whether differences in cognitive functioning were associated with differences in poly-victimization within pairs of siblings sharing their early family environment and either some (dizygotic twins) or all (monozygotic twins) genes. Finally, to test if the results based on the study-specific, prospectively-collected measure of maltreatment could be generalized to another more commonly used measure of childhood maltreatment, we reran the above analyses using the retrospective CTQ as the independent variable. Details are provided in the Supplement.

Study 2: The Dunedin Longitudinal Study

Sample

Participants were members of the Dunedin Longitudinal Study, which tracks a 1972–73 birth cohort of 1037 children born in Dunedin, New Zealand (Figure 1). Full details about the sample are reported elsewhere(34) and in the Supplement.

Childhood victimization

As previously described(28), the measure of childhood maltreatment includes (1) maternal rejection assessed at age 3 years by observational ratings of mothers’ interaction with the study children, (2) harsh discipline assessed at ages 7 and 9 years by parental report of disciplinary behaviours, (3) 2 or more changes in the child’s primary caregiver, and (4) physical abuse and (5) sexual abuse reported by study members once they reached adulthood (and were able to give informed consent). For each child, our cumulative index counts the number of maltreatment indicators during the first decade of life. When Study members were 38 years old, they also completed the CTQ(32). Details about victimization measurements are available in the Supplement.

Cognitive testing

Figure 1 provides an overview of the cognitive testing in the Dunedin study, at ages 3, 11–13, and 38 years. Details are provided in the Supplement.

Statistical analyses

To test the associations between childhood maltreatment between ages 3–11 years (independent variable) and cognitive measures (dependent variable), we ran a series of bivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models. To test if observed associations were accounted for by pre-existing cognitive vulnerabilities and non-specific effects of socio-economic disadvantage (see Supplement), we expanded the bivariate OLS models to include covariates for maternal IQ, Peabody test scores at age 3 years, and family socio-economic status, respectively. To test for significant attenuation of the association by the above covariates, we compared regression coefficients across models(33). To test if the results based on the study-specific, prospectively-collected measure of maltreatment could be generalized to another more commonly used measure of childhood maltreatment, we reran the above analyses using Childhood Trauma Questionnaire scores as the independent variable.

RESULTS

Study 1: E-Risk Study

Does childhood victimization predict low IQ in adolescence?

We first used the E-Risk Study (Figure 1:Panel A) to test if child victimization had immediate effects on general intelligence in adolescence. Children who experienced poly-victimization between ages 5–12 years had lower IQ test scores at age 12 than non-victimized children (beta=−.17, p<0. 01; Table 1:Panel A/Model 1). However, these differences were significantly attenuated once pre-existing differences in the IQ at age 5 years and family socioeconomic status (SES) were taken into account (beta=−.05, p=0.02; Table 1:Panel A/Model 4 and Omitted Variable Bias test p<0.001; Figure 2:Panel B).

Table 1. Association of childhood poly-victimization with the IQ and cognitive functions in the E-Risk Study.

The table shows standardized regression coefficients (betas) for the association between childhood poly-victimization and cognitive measures using Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) linear models and accounting for clustering within family. Panels A–B describe the association between poly-victimization and IQ; Panel C–H describe the association between poly-victimization and executive functions; Panels I–J describe the association between poly-victimization and processing speed. Model 1 shows bivariate (unadjusted) associations between all predictors and the cognitive measures. Model 2 shows the association between childhood poly-victimization and cognitive measures adjusted for the effect of IQ at age 5 years. Model 3 shows the association between childhood poly-victimization and cognitive measures adjusted for the effect of family socio-economic status. Model 4 shows the association between childhood poly-victimization and cognitive measures adjusted for the effect of both IQ at age 5 years and family socio-economic status. "Omitted Variable Bias" shows the difference between the unadjusted and fully adjusted effect of poly-victimization on the cognitive measures.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Omitted Variable Bias* | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | s.e. | p | b2 | s.e. | p | b3 | s.e. | p | b4 | s.e. | p | d1–4 | s.e. | p | |

| Intelligence Quotient | |||||||||||||||

| A. WISC-IQ at age 12 years (N = 2112) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | −0.17 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.13 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | 0.45 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | 0.43 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| B. WAIS-IQ at age 18 years (N = 2045) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | −0.12 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.82 | −0.13 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | 0.42 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | 0.44 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.43 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Executive Function | |||||||||||||||

| C. Rapid Visual Information Processing A' at age 18 years (N = 2042) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | −0.11 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.23 | −0.08 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | 0.30 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | 0.25 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| D. Rapid Visual Information Processing - False Alarms at age 18 years (N = 2044) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.99 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.47 | - | - | - |

| IQ at age 5 years | −0.18 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.18 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.15 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | −0.14 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||

| E. Spatial Working Memory - Total Errors at age 18 years (N = 2044) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | 0.08 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | −0.26 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.25 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | −0.18 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||

| F. Spatial Working Memory - Strategy at age 18 years (N = 2044) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | 0.07 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | −0.24 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.21 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | −0.17 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||

| G. Spatial Span at age 18 years (N = 2041) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | −0.09 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.66 | −0.08 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | 0.29 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | 0.24 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| H. Spatial Span - Reversed at age 18 years (N = 2034) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | −0.11 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.15 | −0.07 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | 0.26 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | 0.22 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Processing Speed | |||||||||||||||

| I. Rapid Visual Information Processing - Mean Latency at age 18 years (N = 2042) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | 0.07 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | −0.14 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | −0.11 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||||||

| J. Spatial Working Memory - Mean Time at age 18 Years (N = 2044) | |||||||||||||||

| Poly-victimization | 0.08 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| IQ at age 5 years | −0.23 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | −0.22 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Family socio-economic status (SES) | −0.11 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.41 | ||||||

d1–4 = b1 – b4

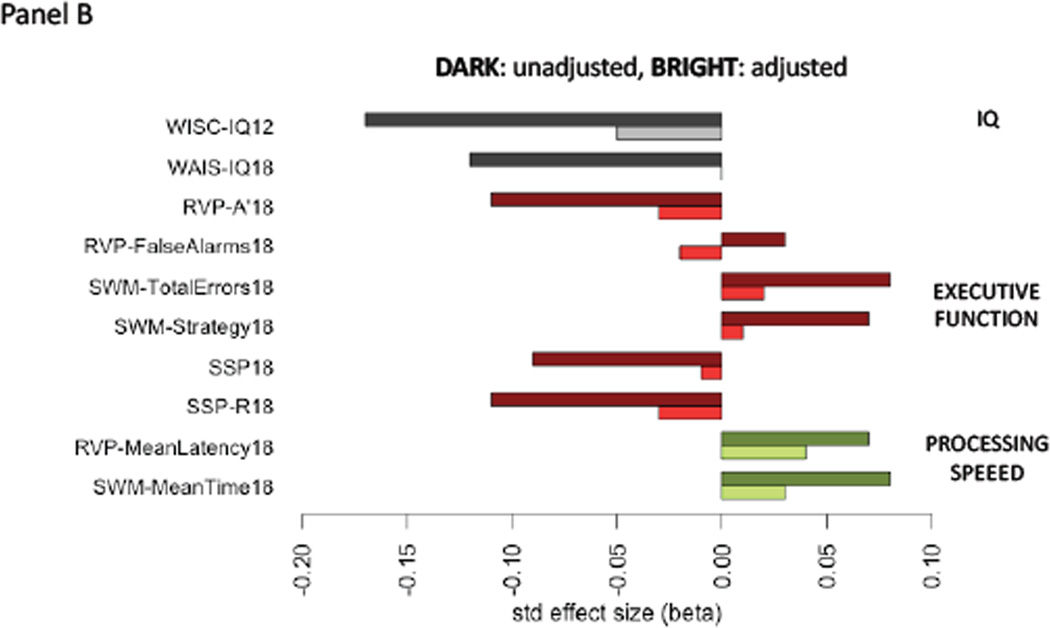

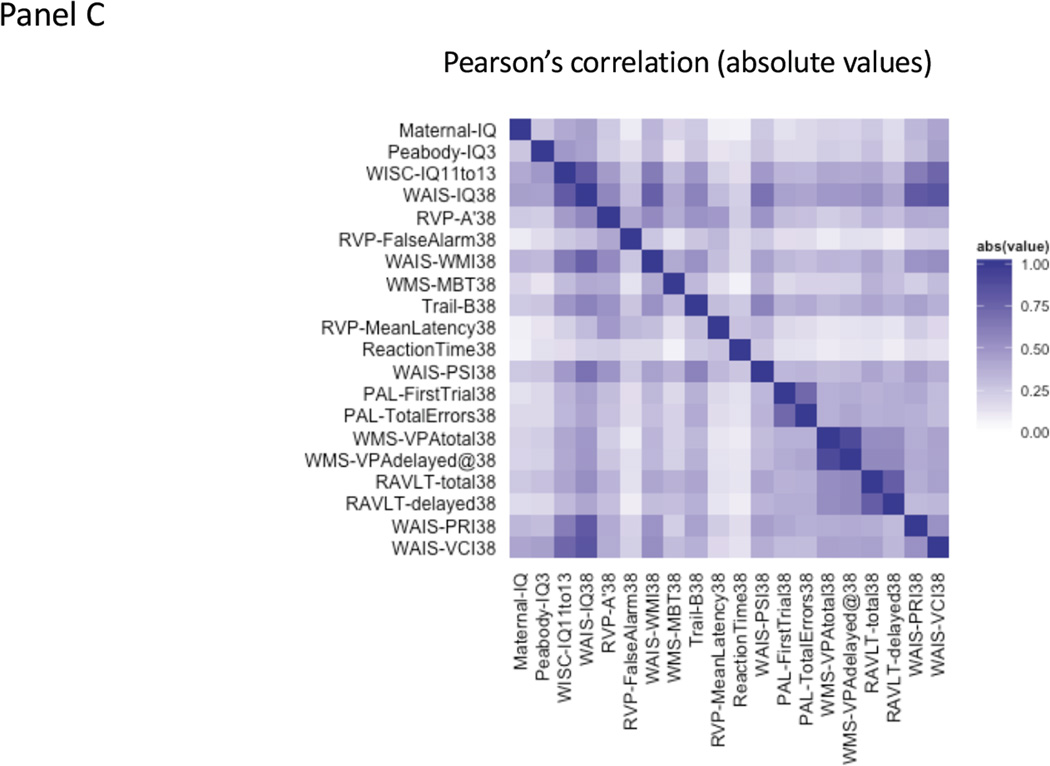

Figure 2.

The association between childhood victimization and cognitive functioning in the E-Risk Study (Panels A, B) and the Dunedin Study (Panels C, D)

The association between childhood victimization and cognitive functioning in two birth cohorts. Panel A: Heat-map displaying the absolute values of correlations across cognitive functions in the E-Risk Study. Dark blue pixels display strong positive absolute values of correlations and light / white pixels display weak correlations. Exact correlation values are reported in Supplementary Table 7. Panel B. Standardized effect sizes (betas) for the association between childhood victimization and different cognitive functions in the E-Risk Study. Dark bars display unadjusted associations. Bright bars of the same color display associations adjusted for cognitive functioning prior to the observational period for victimization (i.e., IQ at 5 years). Panel C: Heat-map displaying the absolute values of correlations across cognitive functions in the Dunedin Study. Dark blue pixels display strong positive absolute values of correlations and light / white pixels display weak correlations. Exact correlation values are reported in Supplementary Table 8. Panel D. Standardized effect sizes (betas) for the association between childhood victimization and different cognitive functions in the Dunedin Study. Dark bars display unadjusted associations. Bright bars of the same color display associations adjusted for cognitive functioning prior to the observational period for victimization (i.e., maternal IQ and Peabody test at 3 years).

E-Risk Study. WPPSI-IQ5= IQ from Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised at 5 years; WISC-IQ12= IQ from Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised at 12; WAIS-IQ18=IQ from Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV at 18; RVP-A’18= CANTAB Rapid Visual Processing A-prime at 18; RVP-FalseAlarms18= CANTAB Rapid Visual Processing Total False Alarms at 18; SWM-TotalErrors18= CANTAB Spatial Working Memory Total Errors at 18; SWM-Strategy18= CANTAB Spatial Working Memory Strategy at 18; SSP18= CANTAB Spatial Span at 18; SSP-R18= CANTAB Spatial Span Reverse at 18; RVP-MeanLatency18= CANTAB Rapid Visual Processing Mean Latency at 18; SWM-MeanTime18= CANTAB Spatial Working Memory Mean Time at 18

Dunedin Study. Maternal-IQ= maternal IQ from the Thurstone SRA Test when study members were 3 years old; Peabody-IQ3=IQ from Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test at 3 years; WISC-IQ1113= average IQ from Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised at 11 and 13; WAIS-IQ38=IQ from Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV at 38; RVP-A’38= CANTAB Rapid Visual Processing A-prime at 38; RVP-FalseAlarms38= CANTAB Rapid Visual Processing Total False Alarms at 38; WAIS-WMI38= WAIS Working Memory Index at 38; WMS-MBT38= Wechsler Memory Scale-III Months of the Year Backwards Test at 38; Trail-B38= Trail-B test at 38; RVP-MeanLatency38= CANTAB Rapid Visual Processing Mean Latency at 38; ReactionTime38= CANTAB Reaction Time at 38; WAIS-PSI38= WAIS Processing Speed Index at 38; PAL-FirstTrial38= CANTAB Paired Associates Learning First Trial at 38; PAL-TotalErrors38= CANTAB Paired Associates Learning Total Errors at 38; WMS-VPAtotal38= Wechsler Memory Scale-III Verbal Paired Associates Total Recall at 38; WMS-VPAdelayed38= Wechsler Memory Scale-III Verbal Paired Associates Delayed Recall at 38; RAVLT-total38= Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test Total Recall at 38; RAVLT-delayed38= Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test Delayed Recall at 38; WAIS-PRI38= WAIS Perceptual Reasoning Index at 38; WAIS-VCI38= WAIS Verbal Comprehension Index at 38.

These findings were replicated in analyses focused on each of the specific types of victimization (Supplementary Tables 1–7). For example, we found lower IQ at age 12 among E-Risk children who had been physically abused (beta=−.09, p<0. 01; Supplementary Table 3:Panel A/Model 1) or neglected (beta=−.14, p<0.01; Supplementary Table 6:Panel A/Model 1). However, these differences, too, were significantly attenuated once pre-existing differences in IQ at age 5 years and family SES were taken into account (beta=−.03, p=0.13 and beta=−.03, p=0.11, respectively; Supplementary Tables 3 and 6:Panel A/Model 4).

Does childhood victimization predict low IQ in young adulthood?

Next, we tested if childhood victimization had late-onset (“sleeper”) effects on IQ in young adulthood. E-Risk children who experienced poly-victimization between ages 5–12 years had lower IQ at age 18 than non-victimized children (beta=−.12, p<0.01; Table 1:Panel B/Model 1). However, these differences were significantly attenuated once pre-existing differences in IQ at age 5 years and family SES were taken into account (beta=.00, p=0.82; Table 1:Panel B/Model 4; Figure 2:Panel B). Similar results emerged when we focused on each of the specific types of victimization (see Supplementary Tables 1–7:Panel B).

Does childhood victimization predict impaired cognitive functions in young adulthood?

Despite these limited residual effects on a broad measure of cognition, such as the IQ, childhood victimization could have affected more specific cognitive functions that are only moderately correlated with the IQ (Figure 2:Panel A). In particular, executive functions and processing speed hinge upon functioning of the prefrontal cortex(35), which continues developing throughout childhood(36) and, thus, might be more sensitive to the effects of childhood victimization. Therefore, we tested the effects of victimization on these functions.

Children who experienced poly-victimization between ages 5–12 years performed more poorly on executive function tests at age 18 years, such as CANTAB Rapid Visual Information Processing A’, Spatial Working Memory Total Errors and Strategy, and Spatial Span (Table 1:Panels C–H/Model 1). Furthermore, children who experienced poly-victimization performed more poorly on processing speed tests at age 18 years, such as CANTAB Rapid Visual Information Processing Mean Latency and Spatial Working Memory Mean Time (Table 1:Panels I–J/Model 1). However, these differences were also significantly attenuated once pre-existing differences in the IQ at age 5 years and family SES were taken into account (Table 1:Panels C–J/Model 4; Figure 2:Panel B). Similar results emerged when we focused on each of the specific types of victimization (see Supplementary Tables 1–7:Panels C–J).

Does childhood victimization predict cognitive deficits in those not victimized before age-5 years?

We considered that IQ tested at age 5 years could have been influenced by earlier victimization and, thus, could be an inadequate baseline measure of cognitive function for some children, if they had been victimized early as infants or toddlers. There was evidence of victimization before age 5 for 307 E-Risk children. In analyses restricted to children without evidence of victimization before age 5, we found similar results as in the overall sample (cf. Supplementary Table 8 “Omitted variable bias” column and Table 1 “Omitted variable bias” column, respectively), suggesting that the limited residual effects of childhood victimization on later cognitive functions were not simply a reflection of biased baseline measures of cognition.

Do differences in childhood victimization predict differences in cognitive function within sibling pairs?

We also took advantage of the co-twin control method in the E-Risk Study to determine whether differences in poly-victimization were associated with differences in cognitive functions within pairs of twins who grew up in the same family and shared some (dizygotic twins) or all (monozygotic twins) of their genetic material(37). However, we did not find associations between poly-victimization and cognitive functions within sibling pairs except for IQ at age 12 in dizygotic twins (Table 2; Supplementary Table 9), suggesting that the associations observed at the individual level (Table 1:Panels A–J/Model 1) were likely explained by unmeasured familial (both genetic and environmental) factors.

Table 2. Association of childhood poly-victimization with the IQ and cognitive functions among twin pairs discordant for victimization.

The table shows Pearson correlations between differences in childhood poly-victimization and differences in cognitive measures within twin-pairs.

| Dizygotic and monozygotic twin pairs (Npairs = 1003 to 1061) |

Monozygotic twin pairs (Npairs = 556 to 578) |

Dizygotic twin pairs (Npairs = 447 to 483) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | |

| Intelligence Quotient | ||||||

| WISC-IQ at age 12 years | −0.066 | 0.032 | −0.020 | 0.636 | −0.100 | 0.028 |

| WAIS-IQ at age 18 years | −0.020 | 0.529 | −0.066 | 0.120 | 0.016 | 0.737 |

| Executive Function | ||||||

| Rapid Visual Information Processing A' at age 18 years | −0.045 | 0.157 | −0.039 | 0.363 | −0.051 | 0.283 |

| Rapid Visual Information Processing - False Alarms at age 18 years | −0.021 | 0.515 | −0.024 | 0.570 | −0.016 | 0.741 |

| Spatial Working Memory - Total Errors at age 18 years | −0.004 | 0.891 | 0.022 | 0.610 | −0.028 | 0.548 |

| Spatial Working Memory - Strategy at age 18 years | −0.009 | 0.773 | 0.017 | 0.685 | −0.035 | 0.458 |

| Spatial Span at age 18 years | 0.011 | 0.724 | 0.003 | 0.938 | 0.017 | 0.716 |

| Spatial Span - Reversed at age 18 years | −0.023 | 0.477 | 0.007 | 0.867 | −0.048 | 0.309 |

| Processing Speed | ||||||

| Rapid Visual Information Processing - Mean Latency at age 18 years | 0.037 | 0.240 | 0.059 | 0.165 | 0.017 | 0.713 |

| Spatial Working Memory - Mean Time at age 18 Years | −0.023 | 0.457 | −0.037 | 0.385 | −0.013 | 0.776 |

Are retrospective reports of childhood victimization in young adulthood associated with low IQ and impaired cognitive functions?

We extended our analysis to test whether the findings could be replicated when childhood victimization was measured at age 18 years with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)(32), a popular tool for retrospectively assessing childhood maltreatment history in adults. E-Risk Study members who reported having been maltreated as children performed more poorly on executive function tests (Spatial Working Memory Total Errors, Spatial Span) and processing speed tests (Rapid Visual Information Processing Mean Latency) but not IQ tests (Supplementary Table 10:Panel A–J/Model 1). However, these differences were significantly attenuated once pre-existing differences in the IQ at age 5 years and family SES were taken into account (Supplementary Table 10:Panel A–J/Model 4). Furthermore, we did not find associations between differences in CTQ scores and differences in cognitive functions within pairs of siblings (Supplementary Table 11).

Study 2: Dunedin Study

Does childhood victimization predict low IQ in adolescence?

Next, we tested whether the findings in the E-Risk Study could be replicated and expanded in an independent and older cohort. In the Dunedin Study (Figure 1:Panel B), children who experienced maltreatment between ages 3–11 years had lower IQ at age 11–13 than non-maltreated children (beta=−.11, p<0.01; Table 3:Panel A/Model 1). However, these differences were again significantly attenuated once indicators of pre-existing cognitive functioning, such as maternal IQ and the child’s IQ at age 3 years, and family SES were taken into account (beta=.00, p=0.89; Table 3:Panel A/Model 4 and Omitted Variable Bias test p<0.01; Figure 2:Panel D).

Table 3. Association between childhood maltreatment and the IQ and cognitive functions in the Dunedin Study.

The table shows standardized regression coefficients (betas) for the association between childhood maltreatment and cognitive measures from Ordinary Least-Squares (linear) regression models. Panels A–B describe the association between maltreatment and IQ; Panel C–G describe the association between maltreatment and executive functions; Panels H–J describe the association between maltreatment and processing speed; Panels K–P describe the association between maltreatment and memory; Panel Q describes the association between maltreatment and perceptual reasoning; Panel R describes the association between maltreatment and verbal comprehension. Model 1 shows bivariate (unadjusted) associations between all predictors and the cognitive measures. Model 2 shows the association between childhood maltreatment and cognitive measures adjusted for the effect of maternal IQ. Model 3 shows the association between childhood maltreatment and cognitive measures adjusted for the effect of IQ at age 3 years. Model 4 shows the association between childhood maltreatment and cognitive measures adjusted for the effect of family socio-economic status. Model 5 shows the association between childhood maltreatment and cognitive measures adjusted for the effect of all covariates. "Omitted Variable Bias" shows the difference between the unadjusted and fully adjusted effect of child maltreatment on the cognitive measures.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Omitted Variable Bias* | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | s.e. | p | b2 | s.e. | p | b3 | s.e. | p | b4 | s.e. | p | b5 | s.e. | p | d1–5 | s.e. | p | |

| Intelligence Quotient | ||||||||||||||||||

| A. WISC-IQ at ages 11–13 years (N = 899) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.11 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.89 | −0.10 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.40 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.48 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.39 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| B. WAIS-IQ at age 38 years (N = 913) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.14 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.21 | −0.10 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.44 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.43 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.43 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.38 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Executive Function | ||||||||||||||||||

| C. Rapid Visual Information Processing - A' at age 38 years (N = 890) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.41 | - | - | - |

| Maternal IQ | 0.24 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.22 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| D. Rapid Visual Information Processing - False Alarms at age 18 years (N = 895) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.001 |

| Maternal IQ | −0.09 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | −0.15 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.71 | |||||||||

| E. WAIS 9 Working Memory Index at age 38 years (N = 910) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.09 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.56 | −0.08 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.34 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.31 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.29 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| F. Wechsler Memory Scale - Months Backwards Test at age 38 years (N = 911) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.12 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.19 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.12 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.18 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.18 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| G. Trails 9 B Test at age 38 years (N = 909) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | −0.24 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.24 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | −0.26 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.26 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | −0.18 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.14 | |||||||||

| Processing Speed | ||||||||||||||||||

| H. Rapid Visual Information Processing - Mean Latency at age 38 (N = 890) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.65 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.80 | - | - | - |

| Maternal IQ | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.13 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | −0.12 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.35 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.51 | |||||||||

| I. Reaction Time Index at age 38 years (N = 895) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.33 | - | - | - |

| Maternal IQ | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.47 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | −0.13 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | −0.10 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.18 | |||||||||

| J. WAIS - Processing Speed Index at age 38 years (N = 912) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.26 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.29 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.24 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.73 | −0.06 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.25 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.27 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.18 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.15 | |||||||||

| K. Paired Associates Learning - First Trial at age 38 years (N = 898) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.17 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.41 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.44 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.37 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.69 | - | - | - |

| Maternal IQ | 0.14 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.10 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.57 | |||||||||

| L. Paired Associates Learning - Total Errors at age 38 years (N = 898) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.75 | - | - | - |

| Maternal IQ | −0.17 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | −0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.12 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | −0.10 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.77 | |||||||||

| M. Wechsler Memory Scale - Verbal Paired Associates, Total Recall at age 38 years (N = 911) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.29 | - | - | - |

| Maternal IQ | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.22 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.22 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| N. Wechsler Memory Scale - Verbal Paired Associates, Delayed Recall at age 38 years (N = 908) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.72 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.71 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.24 | - | - | - |

| Maternal IQ | 0.19 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| O. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test - Total Recall at age 38 years (N = 910) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.09 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.45 | −0.06 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.25 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.27 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.25 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| P. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test - Delayed Recall at age 38 years (N = 911) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.39 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.38 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.90 | - | - | - |

| Maternal IQ | 0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.00 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.19 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Perceptual Reasoning | ||||||||||||||||||

| Q. WAIS - Perceptual Reasoning Index at age 38 years (N = 911) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.13 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.006 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.33 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.29 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.24 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| Verbal Comprehension | ||||||||||||||||||

| R. WAIS - Verbal Comprehension Index at age 38 years (N = 913) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child maltreatment | −0.13 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.39 | −0.10 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.42 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| IQ at age 3 years | 0.44 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.43 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Family SES | 0.41 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

d1–5 = b1 – b5

Does childhood victimization predict low IQ in midlife?

In the older Dunedin cohort, we tested whether childhood maltreatment exerted long-term “sleeper effects” on IQ into midlife. We found that children exposed to maltreatment between ages 3–11 years had lower IQ scores at the Study’s latest assessment, at age 38, than non-maltreated children (beta=−.14, p<0.01; Table 3:Panel B/Model 1). These differences were significantly attenuated once indicators of pre-existing cognitive functioning, such as maternal IQ and the child’s IQ at age 3 years, and family SES were taken into account (beta=−.04, p=0.21; Table 3:Panel B/Model 4; Figure 2:Panel D).

Does childhood victimization predict impaired cognitive functions in midlife?

In order to test more subtle and specific effects of childhood maltreatment on cognition, we used a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests, administered at age 38, that are only moderately correlated with the IQ (Figure 2:Panel C). Children exposed to maltreatment between ages 3–11 years performed more poorly in midlife on several tests of executive function (CANTAB Rapid Visual Information Processing False Alarms; WAIS Working Memory Index; Wechsler Memory Scale Months of the Year Backwards; Trails-B test), processing speed (WAIS Processing Speed Index), memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Total Recall), perceptual reasoning (WAIS Perceptual Reasoning Index), and verbal comprehension (WAIS Verbal Comprehension Index) (Table 3:Panel C–R/Model 1). These differences were significantly attenuated once indicators of pre-existing cognitive functioning, such as maternal IQ and the child’s IQ score at age 3 years, and family SES were taken into account (Table 3:Panel C–R/Model 4; Figure 2:Panel D).

Are reports of childhood victimization in midlife associated with low IQ and impaired cognitive functions?

Finally, we extended our analysis to test whether the findings could be replicated when childhood maltreatment was measured retrospectively at age 38 years with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)(32). Study members who reported having been maltreated as children performed more poorly on IQ tests administered in adolescence and midlife, and on more specific cognitive tests administered in midlife (Supplementary Table 12:Panel A–R/Model 1). However, the link between childhood maltreatment and impaired cognitive performance was significantly attenuated once indicators of pre-existing cognitive functioning, such as maternal IQ and the child’s IQ at age 3 years, and family SES were taken into account (Supplementary Table 12:Panel A–R/Model 5).

DISCUSSION

We found that cognitive deficits previously described in individuals with a history of childhood victimization are largely explained by pre-existing cognitive vulnerabilities and non-specific effects of socio-economic disadvantage. The results both strengthen the evidence for cognitive deficits in individuals with a history of childhood victimization and strongly challenge the conventional causal interpretation given.

Consistent with previous research(16; 17), we found that adolescents and adults with a history of childhood victimization have pervasive deficits in clinically-significant cognitive functions including both general intelligence and more specific measures of executive function, processing speed, memory, perceptual reasoning, and verbal comprehension. We observed this in two population-representative birth cohorts totaling 3,000 individuals born 20 years and 20,000 kilometers apart, and we reproduced the findings using multiple measures of victimization and cognitive assessments in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

In contrast to the conventional causal interpretation given to these findings, our longitudinal-prospective design revealed that cognitive deficits in victimized adolescents and adults were largely explained by cognitive deficits present before the observational period for childhood victimization and by non-specific effects of childhood socio-economic disadvantage. On the one hand, the results are consistent with the high heritability of cognitive functions in humans(38), their strong continuity across the life-course(22), and the stable cognitive deficits previously described in children exposed to adversity(39; 40). On the other hand, they are inconsistent with the causal effects of early-life stress on brain function reported in experimental animal models(41; 42). Although animal models show that early-life stress can have an effect on brain function, human studies, such as those reported here, are needed to test if real-world exposures, such as childhood victimization, do typically affect clinically-relevant brain function in ordinary humans. We speculate that inconsistencies could arise because of several reasons. First, differences in the effects of early-life stress could arise because of differences in life histories and brain-development timing across species(43; 44). Second, because of greater genetic heterogeneity in humans, individual differences may buffer the average effects of early-life stress on brain function to a greater extent in humans than in animal models(45). Third, universal interventions (e.g., schooling) and targeted interventions (e.g., child protection services, psychiatric treatment) in childhood may buffer the effect of early-life stress on brain function in humans but not in animal models. Finally, selective reporting of positive results might have biased scientific evidence(46).

We note a set of limitations. First, it is possible that our measures of childhood victimization have underestimated associations with cognitive functions. However, a comparison between our studies and previous studies suggests that is not the case. For example, Perez and Widom report standardized mean differences (SMD) in IQ between court-substantiated cases of maltreatment and controls of SMD=−0.62 (95%CI=−0.77, −0.46) (47). By comparison, in E-Risk, standardized mean differences in IQ between poly-victimized and non-victimized study members were SMD=−0.68 (95%CI=−0.85, −0.50) at age 12 years and SMD=−0.52 (95%CI=−0.70, −0.34) at age 18 years. In Dunedin, standardized mean differences in IQ between definite maltreated and non-maltreated study members were SMD=−0.29 (95%CI=−0.52, −0.06) at ages 11–13 and SMD=−0.43 (95%CI=−0.66, −0.20) at age 38 years. Confidence intervals for the estimates overlap, in line with expectations that there are no significant differences across the studies. This shows that at the bivariate level our studies have not underestimated the associations between childhood victimization and cognitive functions. However, our multivariate analyses suggest that these associations were significantly attenuated by the presence of cognitive deficits that predated childhood victimization and by confounding genetic and environmental risks. Second, results may only be valid for childhood victimization within the age ranges described in our studies (3 to 12 years). It is possible that victimization of infants and toddlers(48) can cause immediate and stable changes in cognitive functions that we did not detect. To partly test for such effects, in the E-Risk Study we reran analyses excluding children who were victimized before age-5 IQ testing, but results remained unaltered. In the Dunedin Study we capitalized on a measure of maternal IQ, a proxy for the child’s IQ(38) unbiased by the child’s victimization experience. Cognitive deficits were similarly explained by differences in maternal IQ and differences in the child’s IQ at age 3 years (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 12, Model 2 and 3, respectively). These findings suggest that the limited residual effects of childhood victimization on later cognitive functions were unlikely to be due to early post-natal victimization. Third, results may only apply to childhood victimization experiences measured here and not to more extreme and unusual experiences (e.g., institutional upbringing, head-injury-associated victimization). Fourth, results may only apply to the clinically-relevant cognitive measures used here and not to other brain functions that may be affected by victimization experiences (e.g., reward or threat processing). Fifth, there was evidence for a residual effect of childhood victimization on the WISC at age 12 in one of our two samples. Therefore, we cannot conclusively rule out the presence of a small causal effect. Despite these limitations, the findings have implications for neuroscience and clinical practice.

With regard to neuroscience, these findings caution researchers to adopt a more circumspect approach to causal inference in human studies. Together with previous commentaries(18–20), these results highlight that advances in neuroscience methods need to be accompanied by greater attention to study design. Experimental designs to test the effects of child victimization in humans are clearly unethical. Longitudinal designs like the ones used here are costly but essential for tracking within-individual changes(49). Twin and sibling designs are uncommon but can offer crucial insights in this area(50; 51). Future neuroscience research capitalizing on these designs will be important to further test putative causal effects of child victimization on brain structure and function.

With regard to clinical practice, the findings caution clinicians against simplistic case formulations for individuals with complex traumatic histories of child victimization. The results suggest that cognitive deficits should be conceptualized as children’s individual risk factors for victimization(9; 21) as well as potential complicating features during treatment(52; 53). Interventions attempting to support and improve cognition(54; 55) in individuals with history of childhood victimization can be useful to complement more commonly used interventions for emotional and behavioral disturbances in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study is funded by the U.K. Medical Research Council grant G1002190. Additional support was provided by the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Development grants HD077482 and the Jacobs Foundation. Dr Helen Fisher is supported by the MQ: Transforming Mental Health Fellowship MQ14F40.

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is funded by the New Zealand Health Research Council and the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE). Additional support was provided by the U.S. National Institute on Aging grants R01AG032282, R01AG049789 and R01AG048895, the U.K. Medical Research Council grant MR/K00381X, the Economic and Social Research Council grant ES/M010309/1, and the Jacobs Foundation.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Andrea Danese: planning of study, data collection, statistical analyses, writing manuscript

Terrie E Moffitt: planning of study, data collection, revising manuscript

Louise Arseneault: planning of study, data collection, revising manuscript

Ben A Bleiberg: data collection, revising manuscript

Perry B Dinardo: data collection, revising manuscript

Stephanie B Gandelman: data collection, revising manuscript

Renate Houts: statistical analyses, revising manuscript

Antony Ambler: statistical analyses, revising manuscript

Helen Fisher: data collection, revising manuscript

Richie Poulton: planning of study, data collection, revising manuscript

Avshalom Caspi: planning of study, data collection, revising manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol. Behav. 2012;106:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E. Research review: the neurobiology and genetics of maltreatment and adversity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:1079–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moffitt TE. Klaus-Grawe 2012 Think Tank: Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: clinical intervention science and stress-biology research join forces. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013;25:1619–1634. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim L, Radua J, Rubia K. Gray matter abnormalities in childhood maltreatment: a voxel-wise meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:854–863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sapolsky RM. Why Stress Is Bad for Your Brain. Science. 1996;273:749–750. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry BD. Childhood experience and the expression of genetic potential: what childhood neglect tells us about nature and nurture. Brain and Mind. 2002;3:79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tost H, Champagne FA, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Environmental influence in the brain, human welfare and mental health. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18:1421–1431. doi: 10.1038/nn.4108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leppänen JM, Nelson CA. Tuning the developing brain to social signals of emotions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:37–47. doi: 10.1038/nrn2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Susser E, Widom CS. Still searching for lost truths about the bitter sorrows of childhood. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:672–675. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen G, Smith ID. Early intervention: good parents, great kids, better citizens [Internet] Centre for Social Justice and the Smith Institute. 2008 Available from: http://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/UserStorage/pdf/Pdf%20reports/EarlyInterventionFirstEdition.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards R, Gillies V, Horsley N. Brain science and early years policy: Hopeful ethos or 'cruel optimism'? Critical Social Policy. 2015;35:167–187. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishop DVM: Research Review: Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 2012 - neuroscientific studies of intervention for language impairment in children: interpretive and methodological problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:247–259. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deary IJ, Whiteman MC, Starr JM, Whalley LJ, Fox HC. The Impact of childhood intelligence on later life: following up the Scottish mental surveys of 1932 and 1947. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86:130–147. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt FL, Hunter J. General mental ability in the world of work: occupational attainment and job performance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86:162–173. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pechtel P, Pizzagalli DA. Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: an integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2011;214:55–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart H, Rubia K. Neuroimaging of child abuse: a critical review. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:52. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Open Science Collaboration: Psychology. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science. 2015;349:aac4716–aac4716. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falk EB, Hyde LW, Mitchell C, Faul J, Gonzalez R, Heitzeg MM, Keating DP, Langa KM, Martz ME, Maslowsky J, Morrison FJ, Noll DC, Patrick ME, Pfeffer FT, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Thomason ME, Davis-Kean P, Monk CS, Schulenberg J. What is a representative brain? Neuroscience meets population science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:17615–17622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310134110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Button KS, Ioannidis JPA, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, Robinson ESJ, Munafó MR. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:442–442. doi: 10.1038/nrn3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones L, Bellis MA, Wood S, Hughes K, McCoy E, Eckley L, Bates G, Mikton C, Shakespeare T, Officer A. Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet. 2012;380:899–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60692-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deary IJ, Pattie A, Starr JM. The stability of intelligence from age 11 to age 90 years: the Lothian birth cohort of 1921. Psychological Science. 2013;24:2361–2368. doi: 10.1177/0956797613486487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heckman JJ. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica. 1979;47:153. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan GJ, Magnuson KA, Ludwig J. The endogeneity problem in developmental studies. Research in Human Development. 2004;1:59–80. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RSE, McDonald K, Ward A, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:E2657–E2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottfredson LS. Why g matters: The complexity of everyday life. Intelligence. 1997;24:79–132. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, Taylor A, Poulton R. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher HL, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wertz J, Gray R, Newbury J, Ambler A, Zavos H, Danese A, Mill J, Odgers CL, Pariante C, Wong CCY, Arseneault L. Measuring adolescents' exposure to victimization: The Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015;27:1399–1416. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: a neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moffitt TE. E-Risk Study Team: Teen-aged mothers in contemporary Britain. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43:727–742. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A. Statistical Methods for Comparing Regression Coefficients Between Models. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100:1261–1293. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulton R, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study: overview of the first 40 years, with an eye to the future. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:679–693. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1048-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luna B, Garver KE, Urban TA, Lazar NA, Sweeney JA. Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Dev. 2004;75:1357–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, Nugent TF, Herman DH, Clasen LS, Toga AW, Rapoport JL, Thompson PM. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Dongen J, Slagboom PE, Draisma HHM, Martin NG, Boomsma DI. The continuing value of twin studies in the omics era. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012;13:640–653. doi: 10.1038/nrg3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plomin R. Genetics and general cognitive ability. Nature. 1999;402:C25–C29. doi: 10.1038/35011520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richards M, Wadsworth MEJ. Long term effects of early adversity on cognitive function. Arch. Dis. Child. 2004;89:922–927. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.032490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pesonen A-K, Eriksson JG, Heinonen K, Kajantie E, Tuovinen S, Alastalo H, Henriksson M, Leskinen J, Osmond C, Barker DJP, Räikkönen K. Cognitive ability and decline after early life stress exposure. Neurobiol. Aging. 2013;34:1674–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu D, Diorio J, Day JC, Francis DD, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal synaptogenesis and cognitive development in rats. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:799–806. doi: 10.1038/77702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunson KL, Kramár E, Lin B, Chen Y, Colgin LL, Yanagihara TK, Lynch G, Baram TZ. Mechanisms of late-onset cognitive decline after early-life stress. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9328–9338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2281-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clancy B, Finlay BL, Darlington RB, Anand KJS. Extrapolating brain development from experimental species to humans. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:931–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Workman AD, Charvet CJ, Clancy B, Darlington RB, Finlay BL. Modeling transformations of neurodevelopmental sequences across mammalian species. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:7368–7383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5746-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Worp HB, Howells DW, Sena ES, Porritt MJ, Rewell S, O'Collins V, Macleod MR. Can animal models of disease reliably inform human studies? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ioannidis JPA, Munafó MR, Fusar-Poli P, Nosek BA, David SP. Publication and other reporting biases in cognitive sciences: detection, prevalence, and prevention. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 2014;18:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez CM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and long-term intellectual and academic outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:617–633. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Child Maltreatment | Children's Bureau | Administration for Children and Families [Internet] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. 2013 Available from: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- 49.Kraemer HC, Yesavage JA, Taylor JL, Kupfer D. How can we learn about developmental processes from cross-sectional studies, or can we? AJP. 2000;157:163–171. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Ciszewski A, Kasai K, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5:1242–1247. doi: 10.1038/nn958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ouellet-Morin I, Danese A, Bowes L, Shakoor S, Ambler A, Pariante CM, Papadopoulos AS, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L. A discordant monozygotic twin design shows blunted cortisol reactivity among bullied children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:574.e3–582.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:141–151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agnew-Blais J, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment and unfavourable clinical outcomes in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:342–349. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Millan MJ, Agid Y, Brüne M, Bullmore ET, Carter CS, Clayton NS, Connor R, Davis S, Deakin B, DeRubeis RJ, Dubois B, Geyer MA, Goodwin GM, Gorwood P, Jay TM, Joëls M, Mansuy IM, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Murphy D, Rolls E, Saletu B, Spedding M, Sweeney J, Whittington M, Young LJ. Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:141–168. doi: 10.1038/nrd3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harvey AG, Lee J, Williams J, Hollon SD, Walker MP, Thompson MA, Smith R. Improving outcome of psychosocial treatments by enhancing memory and learning. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2014;9:161–179. doi: 10.1177/1745691614521781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.