Abstract

Background

Alcohol consumption is associated with intestinal injury including intestinal leakiness and the risk of developing progressive gastrointestinal cancer. Alcoholics have disruption of intestinal barrier dysfunction that persists weeks after stopping alcohol intake and this occurs in spite of the fact that intestinal epithelial cells turn over every 3-5 days. The renewal and functional regulation of the intestinal epithelium largely relies on intestinal stem cells (ISCs). Chronic inflammation and tissue damage in the intestine can injure stem cells including accumulation of mutations that may result in ISC dysfunction and transformation. ISCs are a key element in intestinal function and pathology; however, very little is known about the effects of alcohol on ISCs. We hypothesize that dysregulation of ISCs is one mechanism by which alcohol induces long-lasting intestinal damage.

Methods

In Vivo: Small intestinal samples from alcohol- and control-fed mice were assessed for ISC markers (Lgr5 and Bmi1) and the changes of the β-catenin signaling using immunofluorescent microscopy, Western blotting, and RT-PCR. Ex Vivo: Organoids were generated from small intestine tissue and subsequently exposed to alcohol and analyzed for ISC markers, β-catenin signaling.

Results

Chronic alcohol consumption significantly decreased the expression of stem cell markers, Bmi 1 in the small intestine of the alcohol fed mice and also resulted in dysregulation of the β-catenin signaling- an essential regulator of its target gene Lgr5 and ISC function. Exposure of small intestine-derived organoids to 0.2% alcohol significantly reduced the growth of the organoids, including budding, and total surface area of the organoid cultures. Alcohol also significantly decreased the expression of Lgr5, p-β-catenin (ser552), and Bmi1 in the organoid model.

Conclusions

Both chronic alcohol feeding and acute exposure of alcohol resulted in ISC dysregulation which might be one mechanism for alcohol-induced long-lasting intestinal damage.

Keywords: alcohol exposure, β-catenin, Bmi1, enteroid, intestinal stem cells, Lgr5, organoid culture

Introduction

One of the consequences of chronic alcohol ingestion in human and rodents is disruption of intestinal barriers which can lead to endotoxemia and gut-derived local and systemic inflammation. This pathological condition appears to be critical for development of alcohol associated pathologies like alcoholic liver disease and malignancy in subset of alcoholics (Ferrier et al., 2006, Purohit et al., 2008, Tang et al., 2008, Wang et al., 2010, Wood et al., 2013). The detrimental consequences of alcohol consumption on intestinal barrier integrity can persist long after alcohol consumption ceases, despite the fact that the entire epithelial cell lining of the intestine is turned over approximately every 2-3 days. These clinical and experimental observations lead us to examine the impact of alcohol on intestinal stem cells (ISCs) which have the potential to mediate the long-term consequences of alcohol on intestinal barrier functions.

The renewal and functional regulation of the intestinal epithelium largely relies on ISCs. Chronic inflammation and tissue damage can injure ISCs, including accumulation of mutations, which may result in ISC dysfunction and transformation. These changes would be expected to result in the long-lasting effects that are observed including changes in intestinal barrier integrity and cancer. Therefore, it is not surprising that ISCs play a critical role in the pathogenesis of many digestive diseases (Sato and Clevers, 2013, Sun, 2011, Moossavi et al., 2013, Hammoud et al., 2013).

We hypothesized that dysregulation of ISCs is achieved via alterations in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The Wnt gene family, consisting of 19 members in mammals, is implicated in the regulation of a wide variety of normal and pathological processes, including embryogenesis, differentiation, and carcinogenesis (Katoh, 2007). The canonical Wnt pathway exists upstream of the β-catenin pathway and can stabilize β-catenin, which in turn enters the nucleus to regulate Wnt pathway target genes (Haegebarth and Clevers, 2009). β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, where it binds T cell factor (Tcf) transcription factors, thus activating target genes, such as cyclin D1 for proliferation and Lgr5 marker of ISCs (Li and Clevers, 2010). Lgr5 is required to maintain adult intestine epithelial proliferation and crypt architecture (Pinto et al., 2003, Kuhnert et al., 2004, Muncan et al., 2006, de Lau et al., 2007).

Using both in vivo mouse model and ex vivo organoid techniques, we showed that (1) alcohol significantly changed the expression of stem cell markers in the small intestine, such as Lgr5, and (2) alcohol induces dysregulation of the β-catenin signaling, an essential mediator of its target gene Lgr5 and function of ISCs.

Materials and Methods

Statement of Ethics

All animal work was approved by the Rush University Medical Center Committee on Animal Resources and the Animal Care Committee at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Animal models

Studies used 6-8 weeks old wild-type C57BL/6J male mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Male mice were individually housed and were fed either a control or an alcohol-containing diet as described previously (Summa et al., 2013). The diet consisted of a two-week introduction and gradual increase in alcohol dose, followed by eight weeks on the full alcohol concentration (29% of total calories, 4.5% v/v). Control mice were fed an isocaloric liquid diet in which the calories from alcohol were replaced with dextrose. The diet was prepared daily and provided to mice in individual graduated sipper tubes (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) for monitoring daily food intake. Mice were euthanized and small intestinal tissue was collected for the indicated analysis.

Mouse small intestinal organoids culture and treatment with alcohol

The mouse small intestine organoids were prepared and maintained as we previously described (Zhang and Sun, 2016, Zhang et al., 2014). Mini gut medium (advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with HEPES, L-glutamine, N2 and B27) was added to the culture, along with R-Spondin, Noggin, and EGF. Organoid cells (6 days after passage) were treated with 0.2% alcohol. The shape of organoids, including budding and the total area of the organoid cultures, were examined. Each condition was examined in triplicate with multiple (>10) organoids in each sample (Zhang and Sun, 2016, Zhang et al., 2014).

Immunoblotting

Mouse intestine tissues were lysed in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 0.2 mM sodium ortho-vanadate, protease inhibitor cocktail), and the protein concentration was measured. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with anti-Bmi 1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-p-β-catenin (ser 552) (Cell Signal, Beverly, MA), β-catenin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), anti-Lgr5 (Abcam), PCNA antibodies(Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA) as previously described (Liao et al., 2008, Ye et al., 2007).

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Total mRNA was extracted from scraped mouse colonic epithelial cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). cDNA was then subjected to real-time PCR (SYBR Green PCR kit, BioRad) with primers (Table 1). Percent expression was calculated as the ratio of the normalized value of each sample relative to that of the corresponding untreated control cells. All real-time PCR reactions were performed in triplicate.

Table 1. Primers for real-time PCR.

| Name | Sequences of primers | Length of PCR (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| β-cantenin Fw | 5- CCCAGTCCTTCACGCAAGAG -3 | 102 |

| β-cantenin Rv | 5- CATCTAGCGTCTCAGGGAACA T-3 | |

| AKT Fw | 5-ATGAACGACGTAGCCATTGTG-3 | 116 |

| AKT Rv | 5-TTGTAGCCAATAAAGGTGCCAT-3 | |

| Bmi1 Fw | 5-ACGTCATGTATGAAGAGGAACCT-3 | 113 |

| Bmi1 Rv | 5-TGGCCGAACTCTGTATTTCAAAG-3 | |

| Lgr5 Fw | 5- ACATTCCCAAGGGAGCGTTC-3 | 139 |

| Lgr5 Rv | 5- ATGTGGTTGGCATCTAGGCG-3 | |

| Actin Fw | 5-TGTTACCAACTGGGACGACA-3 | 139 |

| Actin Rv | 5-CTGGGTCATCTTTTCACGGT-3 |

Immunofluorescence

Small intestinal tissues were freshly isolated and embedded in paraffin wax after fixation with 10% neutral buffered formalin. Tissue samples were processed for immunofluorescence as described previously (Liao et al., 2008). The slides were stained with anti-Lgr5 (Abcam) antibody. Samples were mounted with SlowFade (SlowFade® AntiFade Kit, Molecular Probes) followed by a coverslip, and the edges were sealed to prevent drying. Specimens were examined with a Leica SP5 Laser Scanning confocal microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Small intestinal tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and processed the next day by standard techniques, as previously described (Ye et al., 2007, Lu et al., 2014, Lu et al., 2012, Liu et al., 2010). The slides were stained with anti-Bmi 1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), or anti-p-β-catenin (ser 552) (Cell Signal, Beverly, MA), β-catenin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), cycllin D1, and PCNA antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SD. Differences between two samples were analyzed by Student's t test. Differences among three or more groups were analysed using ANOVA with GraphPad Prism 5. p Values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Results

Alcohol feeding decreased ISC markers in the small intestine

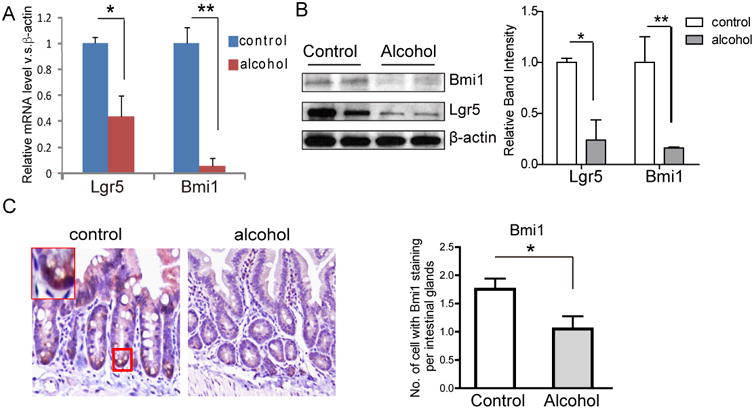

Using small intestine tissue collected from alcohol-fed or control-fed mice, we examined the expression of ISC markers (Lgr5 and Bmi1). Chronic alcohol feeding significantly decreased the mRNA expression and protein levels of Lgr5 and Bmi1 in the small intestine of alcohol-fed compared to control-fed mice (Fig. 1A). Likewise, immunostaining showed less intense Lgr5 and Bmi1 staining in the small intestine of alcohol-fed compared to control-fed mice (Fig. 1B). To further confirm the intestinal stem cell change between control and alcohol-fed mice, immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry were used to detect Bmi1 gene. Bmi1 were decreased in small intestine of alcohol-fed mice compared to control mice (Fig. 1C). Immunofluorescence study also showed the reduced Lgr5 in alcohol-fed small intestine (data not shown). Thus, chronic alcohol feeding in mice reduces both Lgr5 and Bmi1 in stem cells in the small intestine.

Fig 1. Chronic alcohol-exposure decreases ISC markers in mouse small intestine.

(A) Alcohol exposure significantly decreased the mRNA expression of Lgr5 and Bmi1 in alcohol-fed male mice compared to the control-fed male mice (10 weeks), (B) Alcohol exposure significantly decreased the protein levels of Lgr5 and Bmi1 in small intestine. (C) IHC staining showed Bmi1 in the alcohol-exposed small intestine compared to control. Less Bmi1 staining per intestinal glands in alcohol-exposed small intestine. N=3 mice/group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01

Chronic alcohol decreased small intestinal p-β-catenin (ser552)

The p-β-catenin (ser552) is a known marker of intestinal stem cells that has a nuclear distribution (He et al., 2007). Interestingly, IHC data showed that the alcohol-fed mice had less p-β-catenin (ser552) in the small intestine than the control-fed mice (Fig. 2A) with a significant decrease in the number of nuclear β-catenin-positive cells per crypt in the alcohol-fed mice compared with the control mice (Fig. 2B). These IHC data were confirmed via Western blotting which showed that chronic alcohol feeding decreased p-β-catenin (ser552) in the mouse small intestine (Fig. 2C). PI3K-induced and Akt-mediated β-catenin signaling are required for progenitor cell activation (Lee et al., 2010, Regmi et al., 2015, Ormanns et al., 2014, Liu et al., 2014, Tenbaum et al., 2012). The activation of p-beta-catenin (ser552) occurs via the Akt pathway; thus, we examined Akt as an important factor that contributes to phosphorylation of β-catenin. We found significantly difference of p-Akt in the alcohol-exposed intestine, whereas alcohol-exposed induce slightly lower total Akt protein in the intestine, compared to the control intestine without alcohol. There is no significant change of total Akt at the mRNA level in the small intestine without alcohol (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Chronic alcohol-exposure decreases p-beta-catenin (ser552) in mouse small intestine.

(A) immunostaining showed less p-beta-catenin (ser552) in the alcohol-exposed small intestine compared to control. (B) Less p-beta-catenin (ser552) staining per crypts. (C) Alcohol exposure decreased the protein levels of p-beta-catenin (ser552) in small intestine. (D) Akt at the mRNA level in the small intestine without alcohol. N=3 mice/group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01

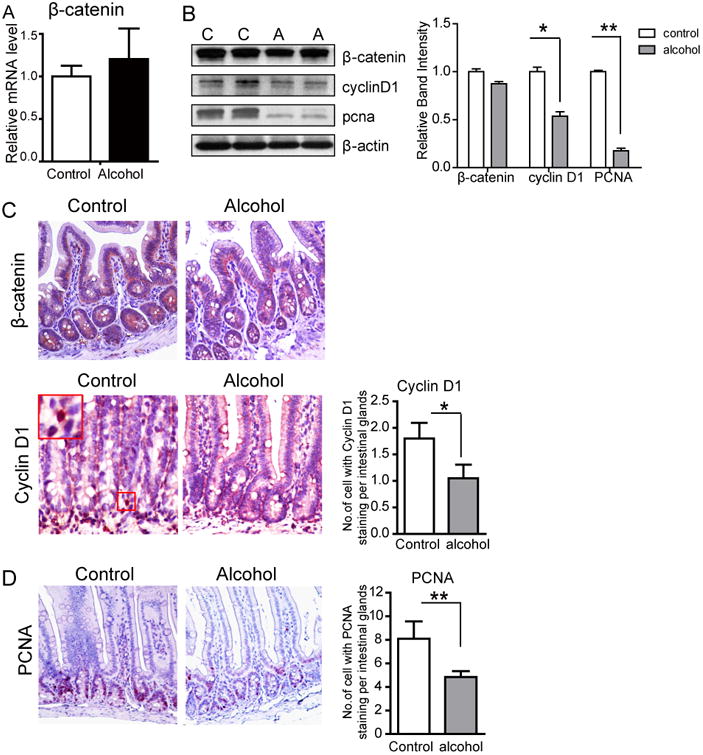

Cyclin D1, target gene of β-catenin, and proliferation were decreased by alcohol feeding in small intestine

We then examined the β-catenin pathway in alcohol-fed or control-fed mice including the expressions of β-catenin at the mRNA and protein levels, its target gene cyclin D1, and proliferation marker PCNA (Fig. 3). At the mRNA level we did not see significant difference of β-catenin mRNA in small intestine between alcohol-fed or control-fed mice (Fig. 3A). At the protein level, we did find significant difference of β-catenin in small intestine between alcohol-fed or control-fed mice (Fig. 3B). We further examined the target gene cyclin D1 of the β-catenin pathway. The protein level of cyclin D1 was decreased in small intestine exposed to alcohol (Fig. 3B). By IHC, we found decreased cyclin D1 staining in the alcohol-fed mouse small intestine (Fig. 3C cyclin D1). Lgr5 is required to maintain adult intestine epithelial proliferation and crypt architecture (Li and Clevers, 2010) and activating target gene cyclin D1 is also for proliferation. Moreover, we measured the proliferation marker PCNA and found its significant reduction by alcohol exposure at the protein level (Fig. 3B PCNA). Proliferative cells were reduced by alcohol feeding in small intestine (Fig. 3D PCNA). Taken together the change of β-catenin pathway appears to be due to a post-transcriptional even (e.g. phosphorylation) and activation of the β -catenin target genes because there was no change of β-catenin mRNA in the alcohol-fed mouse intestine.

Figure 3. The gene expression of beta-catenin signaling in alcohol-fed mice compare to control-fed mice.

The beta-catenin expression was increased in the alcohol-exposed small intestine. (A) The gene expression of beta-catenin by real time RT-PCR. (B) The gene expression of beta-catenin pathway by western blotting. (C) Immunohistochemistry staining of beta-catenin and cyclin D1 in small intestine tissue. (D) Immunohistochemistry staining of PCNA in small intestine tissue. N=3 mice/group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01

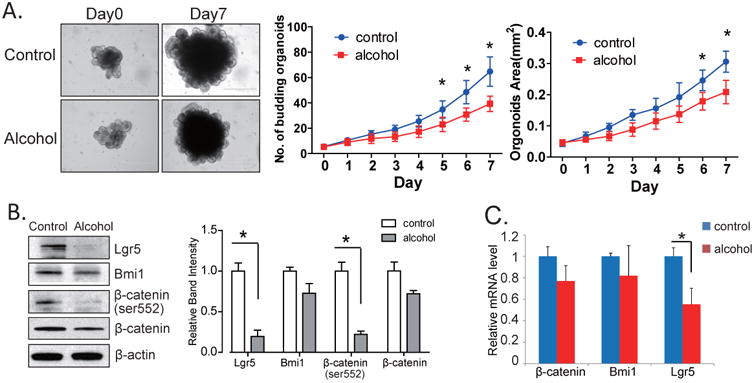

Alcohol decreased the growth of organoids, and decreased Lgr5, p-β-catenin (ser552), and Bmi1 expression in organoids

To rule out confounding factors that may contribute to the ISC dysregulation in vivo, we established an in vitro crypt cell culture organoid model and exposed the culture to 0.2% alcohol. We observed the growth of organoids for 7 days and found that alcohol exposure significantly reduced the growth of organoids, including budding, and total area of the organoid cultures (Fig. 4A). We then investigated the expressions of Lgr5, p-β-catenin (ser552), and Bmi1. Alcohol significantly decreased the expression of Lgr5, p-β-catenin (ser552), and Bmi1 at the protein (Fig. 4B) and RNA (Fig. 4C) levels. These observations are consistent with the in vivo data, suggesting that ISCs are negatively impacted by chronic alcohol. This organoid model also indicates the feasibility to study intestinal alcohol exposure in an enteroid (organoid) model.

Figure 4. Alcohol exposure reduces the growth of organoid culture.

(A) The morphology change of organoid culture treated with 0.2% alcohol. Significant reduction of budding and area of organoid culture after exposed to alcohol. (B)&(C) Expression level of p-beta-catenin, Bmi1, and Lgr5 in the organoid culture by western blotting (4B) and real time RT-PCR (4C). N=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01

Discussion

In the current study, we showed alcohol-induced aberrant intestinal stem cells (ISCs), using a well-established model of alcohol-induced gut leakiness in mice. We have further established an organoid model for alcohol studies of ISCs ex vivo and showed that alcohol disrupts ISC homeostasis, in part, through the β-catenin pathway.

Alcohol causes numerous detrimental effects on the intestine: (1) alcohol damages the intestinal epithelial barrier resulting in hyperpermeability (Summa et al., 2013) which promotes alcoholic liver disease and other inflammation-mediated diseases (Purohit et al., 2008, Tang et al., 2008, Wood et al., 2013, Ferrier et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2010); and (2) alcohol induces several signaling pathways in intestinal epithelial cells, including epithelial mesenchymal transition, and induces susceptibility to colon cancer (Mutlu et al., 2009, Forsyth et al., 2009, Wimberly et al., 2013). The injurious effects of alcohol on the intestine are long-lasting, persisting weeks after abstinence from alcohol consumption. Thus, investigating the mechanism by which alcohol causes such detrimental effects on the intestine is warranted.

Our in vivo and in vitro data all show that alcohol exposure leads to decreased stem cell markers. We have chosen to study Lgr5 and Bmi1 because they are well-established markers of ISCs. Lgr5 and Bmi1 are known to have distinct roles in regulating a subgroup of ISCs (Yan et al., 2011). Adult stem cell niches are often co-inhabited by cycling and quiescent stem cells. In the intestine, lineage tracing has identified Lgr5+ cells as frequently cycling stem cells, whereas Bmi1+, mTert+, Hopx+ and Lrig1+ cells appear to be more quiescent (Roth et al., 2012). Lgr5 marks mitotically active ISCs that exhibit exquisite sensitivity to canonical Wnt modulation, contribute robustly to homeostatic regeneration, and are quantitatively ablated by irradiation. In contrast, Bmi1 marks quiescent ISCs that are insensitive to Wnt perturbations, contribute weakly to homeostatic regeneration, and are resistant to high-dose radiation injury (Yan et al., 2011). Our data also indicate that β-catenin is one mechanism that contributes to the dysregulated ISCs. Alcohol suppresses proliferation of ISCs through dysregulation of β-catenin, as an essential fate-determining factor of alcohol-induced ISC dysfunction. Our finding that alcohol affects β-catenin signaling in intestinal stem cells is similar to the prior study that showed ethanol affects differentiation-related pathways and suppresses Wnt signaling protein expression in human neural stem cells (Vangipuram and Lyman, 2012).

In the current study, we have selected the small intestine as a well-validated and appropriate model to investigate our hypothesis. In the small intestine, a crypt and villus represent the fundamental repetitive unit (Li and Clevers, 2010, Yen and Wright, 2006). The crypt is the proliferative compartment, composed of 250–300 cells in constant, active proliferation, and generates all the cells required to renew the entire intestinal epithelium in 2–3 days in mice. ISCs are located just above Paneth cells, in a permissive microenvironment within the first 4 to 5 cell positions from the bottom of the crypt, with some ISCs interspersed among the Paneth cells (Yen and Wright, 2006, Li and Clevers, 2010). Each crypt has about 30 pluripotent stem cells. The G protein-coupled receptor Lgr5 (Barker et al., 2007) and the Polycomb group protein Bmi1 are two molecular markers of self-renewing and multipotent adult stem cell populations, capable of supporting regeneration of the intestinal epithelium (Barker et al., 2007, Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008). Therefore, the small intestine is one of the best models for studying adult stem cells in healthy and diseased states.

The organoids derived from stem cells in small intestine acts as a bridge between in vivo and in vitro systems. Organoids contain the full complement of stem, progenitor and differentiated cell types (Sato et al., 2009). It provides a novel and powerful ex vivo model for studying stem cell biology. Change of Lgr5 and the β-catenin pathway in organoids after alcohol treatment is consistent with our observations in vivo. Our study indicates the feasibility to use organoids to investigate the effects and mechanism of alcohol-induced injury on ISCs.

Moon et al reported that alcohol induced hypermethylation of ADHFE1, decreased its expression, and stimulated cell proliferation of colon cancer cells (e.g. HT-29, SW480, and DLD-1cells) (Moon et al., 2014). This suggests that the effect of alcohol on intestinal epithelial cell proliferation could be complicated. Future studies will also investigate the changes in the colon exposed to alcohol and potential effects of microbiome.

Intestinal stromal cells actively support the intestinal epithelium and are phenotypically modulatied during inflamamtion (Owens, et al., 2013). There is increasing interest in the therapeutic potential and immune function of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), often referred as “mesenchymal stromal cells”. A better understanding of MSC function is likely to be beneficial in intestinal stromal cell biology, particularly in delineating stromal cell differentiation and modulating resident mesenchymal cell abundance/function for alcohol injury and other intestinal diseases.

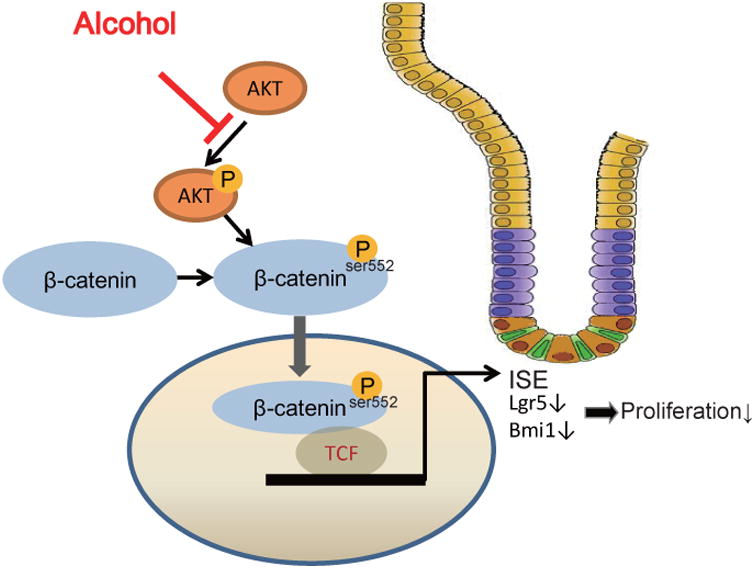

In summary, our studies on ISCs in the mouse model and organoids provide unique and fundamental insights into alcohol-induced injury on the intestine: alcohol disrupts ISC homeostasis, in part, through the β-catenin pathway (Fig. 5). Insights gained from understanding how the Wnt pathway is integrally involved in stem cell maintenance and growth in the intestine may serve as a paradigm for understanding the dual nature of self-renewal signals (Reya and Clevers, 2005). Investigating how the β-catenin pathway is altered by alcohol may provide critical insight into alcohol-induced effects on ISC function and pathology. Further studies on alcohol-induced injury in ISCs possibly shed light on the association between alcohol consumption and intestinal cancer, as well as alcohol-induced gut leakiness and gut-derived inflammation that is involved in alcohol-induced pathologies.

Figure 5. Working model of ISCs regulation in alcohol exposed intestine.

Alcohol disrupts ISC homeostasis through the beta-catenin pathway by reduce expression of target genes (e.g. p-beta-catenin and Lgr5).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIDDK R01 DK105118 to Jun Sun and NIH R01 AA020216 to Ali Keshavarzian.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of Interest.

References

- Barker N, Van es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, Van den born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De lau W, Barker N, Clevers H. WNT signaling in the normal intestine and colorectal cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:471–91. doi: 10.2741/2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier L, Berard F, Debrauwer L, Chabo C, Langella P, Bueno L, Fioramonti J. Impairment of the intestinal barrier by ethanol involves enteric microflora and mast cell activation in rodents. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1148–54. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CB, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Zhang L, Keshavarzian A. Alcohol stimulates activation of Snail, epidermal growth factor receptor signaling, and biomarkers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colon and breast cancer cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;34:19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haegebarth A, Clevers H. Wnt signaling, lgr5, and stem cells in the intestine and skin. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:715–21. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud SS, Cairns BR, Jones DA. Epigenetic regulation of colon cancer and intestinal stem cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XC, Yin T, Grindley JC, Tian Q, Sato T, Tao WA, Dirisina R, Porter-westpfahl KS, Hembree M, Johnson T, Wiedemann LM, Barrett TA, Hood L, Wu H, LI L. PTEN-deficient intestinal stem cells initiate intestinal polyposis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:189–98. doi: 10.1038/ng1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M. WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4042–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnert F, Davis CR, Wang HT, Chu P, Lee M, Yuan J, Nusse R, Kuo CJ. Essential requirement for Wnt signaling in proliferation of adult small intestine and colon revealed by adenoviral expression of Dickkopf-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:266–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536800100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Goretsky T, Managlia E, Dirisina R, Singh AP, Brown JB, May R, Yang GY, Ragheb JW, Evers BM, Weber CR, Turner JR, He XC, Katzman RB, LI L, Barrett TA. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling mediates beta-catenin activation in intestinal epithelial stem and progenitor cells in colitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:869–81. 881 e1–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao AP, Petrof EO, Kuppireddi S, Zhao Y, Xia Y, Claud EC, Sun J. Salmonella type III effector AvrA stabilizes cell tight junctions to inhibit inflammation in intestinal epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Lu R, Wu S, Sun J. Salmonella regulation of intestinal stem cells through the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:911–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YZ, Wu K, Huang J, Liu Y, Wang X, Meng ZJ, Yuan SX, Wang DX, Luo JY, Zuo GW, Yin LJ, Chen L, Deng ZL, Yang JQ, Sun WJ, He BC. The PTEN/PI3K/Akt and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways are involved in the inhibitory effect of resveratrol on human colon cancer cell proliferation. Int J Oncol. 2014;45:104–12. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Liu X, Wu S, Xia Y, Zhang YG, Petrof EO, Claud EC, Sun J. Consistent activation of the beta-catenin pathway by Salmonella type-three secretion effector protein AvrA in chronically infected intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1113–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00453.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Wu S, Zhang YG, Xia Y, Liu X, Zheng Y, Chen H, Schaefer KL, Zhou Z, Bissonnette M, LI L, Sun J. Enteric bacterial protein AvrA promotes colonic tumorigenesis and activates colonic beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncogenesis. 2014;3:e105. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2014.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon JW, Lee SK, Lee YW, Lee JO, Kim N, Lee HJ, Seo JS, Kim J, Kim HS, Park SH. Alcohol induces cell proliferation via hypermethylation of ADHFE1 in colorectal cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:377. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moossavi S, Zhang H, Sun J, Rezaei N. Host-microbiota interaction and intestinal stem cells in chronic inflammation and colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2013;9:409–22. doi: 10.1586/eci.13.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muncan V, Sansom OJ, Tertoolen L, Phesse TJ, Begthel H, Sancho E, Cole AM, Gregorieff A, De Alboran IM, Clevers H, Clarke AR. Rapid loss of intestinal crypts upon conditional deletion of the Wnt/Tcf-4 target gene c-Myc. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8418–26. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00821-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu E, Keshavarzian A, Engen P, Forsyth CB, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P. Intestinal dysbiosis: a possible mechanism of alcohol-induced endotoxemia and alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2009;33:1836–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormanns S, Neumann J, Horst D, Kirchner T, Jung A. WNT signaling and distant metastasis in colon cancer through transcriptional activity of nuclear beta-Catenin depend on active PI3K signaling. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2999–3011. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D, Gregorieff A, Begthel H, Clevers H. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1709–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.267103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit V, Bode JC, Bode C, Brenner DA, Choudhry MA, Hamilton F, Kang YJ, Keshavarzian A, Rao R, Sartor RB, Swanson C, Turner JR. Alcohol, intestinal bacterial growth, intestinal permeability to endotoxin, and medical consequences: summary of a symposium. Alcohol. 2008;42:349–61. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.03.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regmi SC, Park SY, Kim SJ, Banskota S, Shah S, Kim DH, Kim JA. The Anti-Tumor Activity of Succinyl Macrolactin A Is Mediated through the beta-Catenin Destruction Complex via the Suppression of Tankyrase and PI3K/Akt. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;434:843–50. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Franken P, Sacchetti A, Kremer A, Anderson K, Sansom O, Fodde R. Paneth cells in intestinal homeostasis and tissue injury. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi E, Capecchi MR. Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nat Genet. 2008;40:915–20. doi: 10.1038/ng.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Clevers H. Growing self-organizing mini-guts from a single intestinal stem cell: mechanism and applications. Science. 2013;340:1190–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1234852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, Van de wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, Van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summa KC, Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Shaikh M, Cavanaugh K, Tang Y, Vitaterna MH, Song S, Turek FW, Keshavarzian A. Disruption of the Circadian Clock in Mice Increases Intestinal Permeability and Promotes Alcohol-Induced Hepatic Pathology and Inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. Enteric Bacteria and Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:285–297. doi: 10.3390/cancers3010285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Banan A, Forsyth CB, Fields JZ, Lau CK, Zhang LJ, Keshavarzian A. Effect of alcohol on miR-212 expression in intestinal epithelial cells and its potential role in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:355–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenbaum SP, Ordonez-Moran P, Puig I, Chicote I, Arques O, Landolfi S, Fernandez Y, Herance JR, Gispert JD, Mendizabal L, Aguilar S, Ramon Y Cajal S, Schwartz S, Jr, Vivancos A, Espin E, Rojas S, Baselga J, Tabernero J, Munoz A, Palmer HG. beta-catenin confers resistance to PI3K and AKT inhibitors and subverts FOXO3a to promote metastasis in colon cancer. Nat Med. 2012;18:892–901. doi: 10.1038/nm.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangipuram SD, Lyman WD. Ethanol affects differentiation-related pathways and suppresses Wnt signaling protein expression in human neural stem cells. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2012;36:788–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HJ, Zakhari S, Jung MK. Alcohol, inflammation, and gut-liver-brain interactions in tissue damage and disease development. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1304–13. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberly AL, Forsyth CB, Khan MW, Pemberton A, Khazaie K, Keshavarzian A. Ethanol-induced mast cell-mediated inflammation leads to increased susceptibility of intestinal tumorigenesis in the APC Delta468 min mouse model of colon cancer. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(1):E199–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S, Pithadia R, Rehman T, Zhang L, Plichta J, Radek KA, Forsyth C, Keshavarzian A, Shafikhani SH. Chronic alcohol exposure renders epithelial cells vulnerable to bacterial infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan KS, Chia LA, Li X, Ootani A, Su J, Lee JY, Su N, Luo Y, Heilshorn SC, Amieva MR, Sangiorgi E, Capecchi MR, Kuo CJ. The intestinal stem cell markers Bmi1 and Lgr5 identify two functionally distinct populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;109:466–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118857109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z, Petrof EO, Boone D, Claud EC, Sun J. Salmonella effector AvrA regulation of colonic epithelial cell inflammation by deubiquitination. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:882–92. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TH, Wright NA. The gastrointestinal tract stem cell niche. Stem Cell Rev. 2006;2:203–12. doi: 10.1007/s12015-006-0048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YG, Sun J. Study Bacteria-Host Interactions Using Intestinal Organoids. Methods Mol Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/7651_2016_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YG, Wu S, Xia Y, Sun J. Salmonella-infected crypt-derived intestinal organoid culture system for host-bacterial interactions. Physiol Rep. 2014;2 doi: 10.14814/phy2.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]