Abstract

The phagocytic clearance of host cells is important for eliminating dying cells and for the therapeutic clearance of antibody-targeted cells. As ubiquitous, motile and highly phagocytic immune cells, macrophages are principal players in the phagocytic removal of host cells throughout the body. In recent years great strides have been made in identifying the molecular mechanisms that control the recognition and phagocytosis of cells by macrophages. However, much less is known about the physical and metabolic constraints that govern the amount of cellular material macrophages can ingest and how these limitations affect the overall efficiency of host cell clearance in health and disease. In this review we will discuss, in the contexts of apoptotic cells and antibody-targeted malignant cells, how physical and metabolic factors associated with the internalization of host cells are relayed to the phagocytic machinery and how these signals can impact the overall efficiency of cell clearance. We also discuss how this information can be leveraged to increase cell clearance for beneficial therapeutic outcomes.

Keywords: Macrophage, Phagocytosis, Apoptosis, Efferocytosis, GTPase, Monoclonal antibody therapy, Lymphoid malignancy, Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, Cellular metabolism

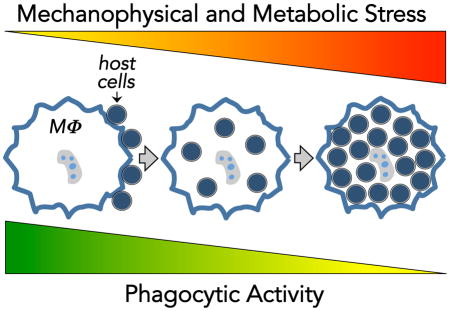

Graphical Abstract

Macrophages play a vital role in the phagocytic clearance of host cells in two important physiologic settings: dead cell clearance (efferocytosis) and therapeutic antibody-dependent cell clearance. This review discusses the molecular pathways that control how macrophages sense and respond to the mechanophysical and metabolic stress resulting from the engulfment of large numbers of host cells and how these responses can affect the phagocytic capacity of macrophages in physiologic settings.

Introduction

The cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate the phagocytic clearance of dying cells (efferocytosis) and antibody-targeted host cells have become increasingly well understood in recent years [1–3]. Efferocytosis plays key roles in normal tissue development and in shaping innate and adaptive immune responses to cell death [4–6]. Antibody-dependent cell phagocytosis (ADCP) is a key cellular mechanism for the therapeutic elimination of deleterious host cells by monoclonal antibodies (mAb) in cancer and autoimmunity [7,8]. Given the relevance of host cell clearance to a broad array of diseases there is substantial interest in developing new approaches to enhance the efficiency and specificity of host cell recognition and phagocytosis by macrophages and other phagocytes. However, an important but often overlooked aspect of such phagocytosis-promoting approaches is that phagocytes have a finite capacity to acquire and process host cell material before reaching a state of saturation characterized by a sharp decline in phagocytic activity. Recent evidence from studies of efferocytosis and ADCP – the two best-studied forms of host cell phagocytosis – suggest that phagocytes employ feedback mechanisms in response to the physical and metabolic burden of engulfed cellular material, but the precise mechanisms that underlie these responses are just beginning to be elucidated. Although many cell types can carry out host cell phagocytosis, including non-hematopoietic cells like mesenchymal cells, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts [9], macrophages are the principal effectors of cell clearance in efferocytosis and ADCP. Therefore, we will focus largely on evidence garnered from studies of macrophages to discuss the parameters and potential feedback mechanisms that define phagocytic capacity in efferocytosis and ADCP.

Efferocytosis: Mechanisms and Consequences

Apoptosis is the primary means for eliminating unwanted nucleated cells, and the phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells, a process termed ‘efferocytosis,’ is the principal cellular mechanism for eliminating these dying cells in normal and diseased tissues [4–6,10]. Efferocytosis is regulated by a multitude of complex and redundant signaling networks within and between phagocytes and target cells that ensure the swift recognition and engulfment of dying cells in every tissue in the body throughout life [1,6,9]. Efferocytosis has garnered considerable attention in recent years as numerous studies in mice and humans have linked defective efferocytosis to increased tissue inflammation and organ-specific and systemic autoimmunity [11–19]. The prevailing model to explain the link between efferocytosis and disease is that the rapid clearance of apoptotic cells prevents cellular necrosis and the release of intracellular damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that can trigger deleterious immune activation. Although many aspects of this model remain to be fully explored, it is clear that the swift and non-inflammatory removal of apoptotic corpses is a decisive factor in the health and function of mammalian tissues.

The molecular mechanisms of apoptotic cell recognition and engulfment are becoming increasingly well understood. As discussed in detail in a number of recent reviews, the molecular ‘code’ for apoptotic cell removal involves a diverse range of soluble and cell-bound proteins, lipids and metabolites that act as signals that enable macrophages to locate and engulf apoptotic cells [1,6,20,21]. With respect to phagocytosis, a number of receptors on macrophages are capable of recognizing and binding phosphatidylserine (PS) and other so-called ‘eat-me’ signals enriched on the surface of apoptotic cells [22]. PS receptors are a structurally diverse set of molecules that include single-pass transmembrane receptors like Tim-4 and CD300f [23,24], the G protein-couple receptor (GPCR) Bai1 [25], heterodimeric αvβ3/5 integrins [12,26,27], and the receptor tyrosine kinases Mer and Axl [28–30]. As depicted in Figure 1, receptor-mediated apoptotic cell recognition occurs either via direct binding of the efferocytic receptor to PS (e.g. Bai1, Stab2) or indirectly via macrophage receptor binding to PS-binding ‘bridging’ proteins on apoptotic cells (e.g. MFG-E8/αvβ3/5, Gas6/Mer). The specific efferocytosis receptor(s) used by macrophages in vivo can vary depending the type and state of the tissue being studied, and in some instances macrophages utilize a combination of PS receptors and tethering receptors (e.g. Tim-4) to coordinate apoptotic cell engulfment [30,31]. Upon target binding, efferocytic receptors trigger rapid actin polymerization at the phagocytic synapse that drives pseudopodia extension and target envelopment (Figure 1). Although the specific signaling pathways activated by individual PS receptors can vary, these pathways ultimately converge on the small GTPase Rac, leading to activation of the Arp2/3 actin nucleation complex that coordinates actin dynamics and target internalization (Figure 1 and refs. [1,32]). Following internalization, apoptotic cells are trafficked and degraded via the phagolysosomal pathway [33].

Figure 1. Mechanisms of efferocytosis and antibody-dependent phagocytosis.

Depiction of some of the key signaling events regulating efferocytosis (left) and antibody-dependent cell phagocytosis (right). Prominent features of these forms of phagocytosis are indicated in the shaded box to the right of each diagram. For simplicity, efferocytosis receptors are depicted categorically as tethering, direct, or indirect phosphatidylserine- (PS) binding receptors, from left to right on the diagram. The diagram on the right depicts two forms of antibody-dependent cell phagocytosis (ADCP): Fc receptor (FcR)-mediated phagocytosis and complement receptor (CR) mediated phagocytosis. For simplicity, ADCP receptors shown are FcγRI with associated γ chain (left) and CR3 αMβ2 integrin binding to iC3b on the surface of the target cell. ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif.

Antibody-dependent cell phagocytosis (ADCP)

Unlike efferocytosis which occurs via endogenous signals, the therapeutic clearance of viable cells using monoclonal antibodies (mAb) leverages the ability of macrophages to carry out antibody-dependent cell phagocytosis (ADCP) as a cytotoxic mechanism. The macrophage receptors required for ADCP are less heterogeneous than for efferocytosis, with ADCP depending almost entirely on Fc receptors (FcR) that bind the Fc portion of immunoglobulins (Figure 1). Human macrophages express all the known FcγR [3,7]. All of these receptors except FcγRIIB, bind to the Fc region of antibodies ligated to target cells resulting in membrane receptor clustering and phosphorylation of the FcγR cytoplasmic signaling ITAM motifs (Figure 1) [3]. This is followed by formation of a phagocytic synapse and then a phagocytic cup by actin polymerization followed by pseudopod extension around the target cell, in a process called zippering phagocytosis (Figure 1) [34]. Ongoing actin rearrangement then extends the macrophage cell membrane around the target followed by scission from the plasma membrane to form a phagosome within the macrophage [3,34,35]. The phagosome matures by an orderly sequence of fusions with endosomes and lysosomes to acquire a range of digestive enzymes and is acidified by the action of proton pumps resulting in target cell digestion [34]. Antibodies can also trigger ADCP indirectly via activation of the classical complement pathway. C3-derived iC3b bound covalently to the target cell membrane is ligated by macrophage complement receptor 3 (CR3, integrin αMβ2) that activates a discrete signaling pathway leading to engulfment by sinking phagocytosis (Figure 1) [3,34]. The resultant phagosome then undergoes maturation and content digestion as described above [34].

Negative regulation of phagocytosis

Several inhibitory signaling pathways have been identified that function to suppress phagocytosis and prevent non-specific host cell engulfment. CD47, an immunoglobulin superfamily transmembrane protein, is constitutively expressed on red blood cells, viable nucleated cells and has been shown to be upregulated on some malignant cells [36–39]. CD47 functions as a so-called ‘don’t eat me’ signal in both efferocytosis and ADCP via binding to SIRPα receptors on macrophages, leading to activation of tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 and attenuation of signaling to Rac downstream of phagocytic receptors [36,40,41]. Genetic or pharmacologic blockade of CD47 in vivo can significantly enhance the clearance of apoptotic cells and promote tumor clearance [37,42]. Another major point of negative regulation for phagocytosis is the coordinated activation of Rho GTPases. As shown in Figure 1, Rac plays a vital role in driving actin polymerization and target internalization during efferocytosis and Fc-dependent phagocytosis. However, other Rho GTPases, including RhoA, RhoG and Cdc42, have distinct spatiotemporal activation patterns during phagocytosis and can act to either promote or inhibit engulfment [2,43,44]. RhoA activation for example has a well-established role as a negative regulator of efferocytosis [45,46]. Although the mechanisms leading to RhoA activation during efferocytosis are not well understood, RhoA and Rac have been found to engage in mutual antagonism in many cell signaling contexts including phagocytosis [47]. By contrast, RhoA activation positively regulates complement receptor 3-mediated phagocytosis (Figure 1), but its role in Fc receptor-mediated host cell engulfment is presently not well defined [44]. As discussed in more detail below, the pathways that negatively regulate phagocytosis play a potentially crucial role in determining the phagocytic capacity of macrophages.

The role of macrophages in host cell clearance

Although many immune and non-immune cell types are competent to carry out host cell phagocytosis, macrophages are widely thought to be one of the most important mediators of host cell phagocytosis in vivo. Here we will discuss the known roles of macrophages in efferocytosis and ADCP and also review the experimental evidence that macrophages indeed have a finite capacity for engulfing host cells.

Role of macrophages in efferocytosis

There are two main lines of evidence supporting a key role for tissue macrophages in the clearance of apoptotic cells. First, a number of studies have shown that when exogenous apoptotic cells are given to mice by various routes they localize predominantly to macrophages versus other types of phagocytic cell types in the tissue. This is true for administration of apoptotic cells to lungs, spleen, liver, peritoneum, and bone marrow [14,16,48–53]. Secondly, studies examining the clearance of endogenous apoptotic cells using mice where macrophages are selectively depleted either chemically or genetically have found that the loss of macrophages is associated with a build up of uncleared dead cells in the lungs, splenic marginal zones and liver [49,51,54]. Additionally, loss of function of certain genes that are exclusively expressed on tissue macrophages, like Tim-4 on peritoneal macrophages, can result in failure to clear apoptotic cells in vivo [52,55]. Nevertheless, there are numerous examples where non-macrophage cell types play a key role in cell clearance. For example, mice completely lacking macrophages due to germline deletion of the hematopoietic transcription factor PU.1 show only modest delays in the clearance of dead cells during embryonic development [56]. Similarly during mammary gland involution large numbers of milk-secreting epithelial cells undergo apoptosis, but macrophages are largely absent from these tissues, and the bulk of the apoptotic cell load is cleared via lumenal shedding and engulfment by viable epithelial cells [57]. In the lung and gut where epithelial homeostatic cell turnover is high, viable epithelial cells are capable of engulfing apoptotic cells, thereby supplementing the phagocytic function of resident macrophages [14,15]. Thus, an important theme is that the efficient clearance of apoptotic cells involves the coordinated phagocytic activity of macrophages and non-macrophages to successfully clear apoptotic cells from normal and inflamed tissues [58].

Role of macrophages in ADCP

Macrophage-mediated ADCP has physiological, pathological and therapeutic roles in humans. Tissue-resident, or ‘fixed’, macrophages in the liver and spleen have a critical physiological role in the destruction of senescent and damaged red blood cells and platelets. One of the mechanisms for this phagocytosis is the incremental ligation of naturally occurring antibodies to red blood cells which eventually results in ADCP [59]. Pathological production of anti-red blood cell or anti-platelet autoantibodies can markedly increase ADCP by fixed macrophages in the liver and spleen. Increased destruction of red blood cells results in autoimmune hemolytic anemia and increased destruction of platelets causes immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) as previously reviewed [60]. The development of therapeutic unconjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAb) over the past two decades has been a major advance in the management of malignancies and autoimmune disease. The cytotoxicity of many of these mAb is primarily mediated by the innate immune system [7,8]. More recently, the use of intravital imaging and macrophage depletion strategies have revealed that ADCP by tissue-resident macrophages, particularly Kupffer cells in the liver, are the major mediator of the therapeutic effect of these drugs, especially when used to treat B cell malignancies [61–63].

Regulating the phagocytic capacity of macrophages in efferocytosis and ADCP

Microscopic examination of cultured mouse and human macrophages reveals the capacity of these cells to rapidly engulf large amounts of cellular material, with individual macrophages at times containing 10–20 apoptotic or antibody-opsonized lymphocytes (Figure 2 and [30,46,64–68]). Similarly, macrophages can also engulf very large particles such as synthetic targets with diameters up to ~30μm [69]. By contrast, non-hematopoietic phagocytes such as epithelial cells and fibroblasts display a much reduced capacity to engulf and digest host cells compared to macrophages [70]. This capacity to engulf and process large volumes of material is one of the characteristic features of ‘professional’ phagocytes like macrophages and dendritic cells.

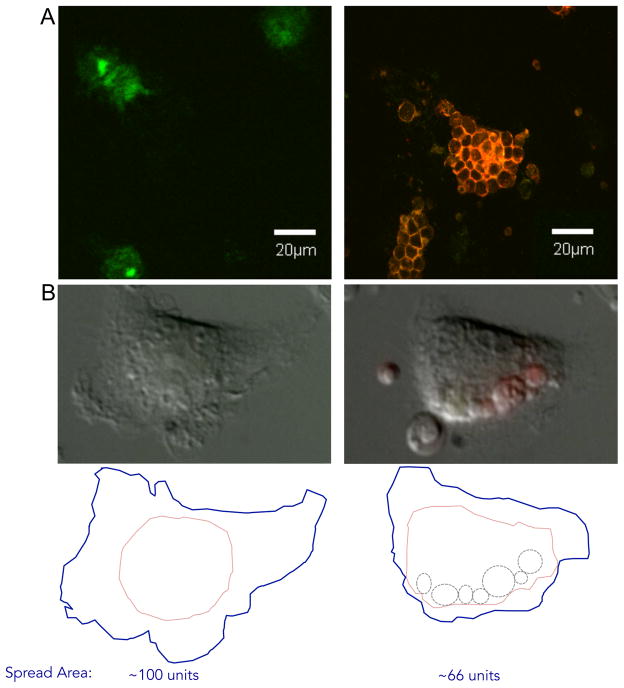

Figure 2. Macrophage phagocytosis of host cells.

A) Human monocyte-derived macrophages (green cells stained with FITC conjugated anti-CD11b) on left were incubated with autologous PKH-26-labeled chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells (red) opsonized with the anti-CD52 IgG1 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab resulting in phagocytosis (right) as described in ref. 65. B) Still images from time-lapse microscopy of mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages fed apoptotic lymphocytes (green and red). Left image is prior to feeding, and right image is the same macrophage 90 min after feeding. Below, tracing of entire visible perimeter of macrophage (blue), main cell body of macrophage (pink), and location of internalized cells (dashed circles). Approximate spread area was calculated using a square grid overlay. Relative area within blue traces are shown below (unfed cell on left was assigned 100 arbitrary units of area).

However, the phagocytic capacity of macrophages is finite, and recent work has shown that macrophages can reach a point of saturation (or ‘exhaustion’) beyond which their phagocytic activity is substantially impaired. Exhaustion in the context of ADCP has been modeled in vitro using human monocyte-derived macrophages cultured in the presence of excess numbers of IgG-opsonized lymphocytes. Under these conditions, maximal clearance is achieved after 4 hours, with very little additional engulfment beyond this time [63,65]. Moreover, the presence of excess IgG-opsonized lymphocytes on macrophages for 24 hours leads to a sharp decrease in their phagocytic activity upon refeeding with fresh targets compared to previously unfed macrophages [65]. Interestingly, data from these experiments indicate that the length of time may be a more important factor than the numbers of cell targets in mediating macrophage exhaustion; when macrophages are fed a surfeit of targets for a short period of time (<4hrs) followed by removal of excess targets, the fed macrophages can in fact display increased phagocytic activity upon re-feeding with fresh target cells [11,13]. In vivo, the cytotoxic capacity of macrophage ADCP is determined by the number of macrophages, the phagocytic capacity of individual macrophages, and the ability of antibodies to ligate antigens on target cells. Limited phagocytic capacity has been experimentally demonstrated in patients with the lymphoid malignancy chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), a disease characterized by the accumulation of monoclonal mature B-lymphocytes with a fraction of these malignant cells circulating in the blood. Treatment outcome has been markedly improved by the addition of the anti-CD20 mAb rituximab to chemotherapy regimens [71]. The ability to measure circulating CLL cells following treatment with mAb has allowed for important in vivo studies in humans. Intravenous infusions of more than 60–100mg of rituximab or the second generation anti-CD20 ofatumumab results in a rapid decrease in circulating CLL cells followed by a rebound in these counts despite sustained high blood levels of the therapeutic mAb over the subsequent 24 hours [72–75]. These finding suggested failure to kill all circulating CLL cells because of exhaustion of innate immune system cytotoxicity (primarily ADCP and complement-mediated lysis) followed by re-equilibration of CLL cells from the lymphoid tissue compartment. Subsequent in vitro studies using monocyte derived macrophages and autologous CLL cells have demonstrated rapid ADCP of CLL cells over ~ 4 hours followed by no further phagocytosis suggestive of macrophage exhaustion [65]. The mechanisms of this effect are being further investigated and data derived from these studies could be very useful in modifying therapy to improve treatment efficacy.

Exposure to apoptotic cells has been shown to similarly affect the efferocytic capacity of macrophages in vitro. Work by Erwig et al showed that exposure of rat bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) to apoptotic neutrophils for 30 minutes led to a marked reduction in efferocytosis activity that persisted for at least 48 hours [76]. Interestingly, the authors also note that prior exposure to apoptotic neutrophils had no effect on BMDM phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized red blood cells, suggesting that apoptotic neutrophils induced an efferocytosis-specific state of phagocytic exhaustion. By contrast, a number of recent studies have shown that prior exposure of macrophages to apoptotic cells can result in a pro-phagocytic ‘priming’ effect, characterized by increased expression of multiple components of the phagocytic machinery (discussed below) [11,13]. These findings indicate that macrophages have the capacity to adjust their phagocytic machinery in response to engulfed cargo, although the molecular mechanisms and in vivo relevance of these feedback pathways remain poorly understood.

Making room: How physical limitations affect macrophage phagocytosis

In experimental systems where cellular prey are in gross excess, macrophages do not continue to engulf material to the point of lysis. Rather, macrophages in these environments are able to adjust the rate of uptake of new material in a manner commensurate with their available capacity. This raises a fascinating question: how does a macrophage know when it is ‘full’? Although poorly understood, current evidence suggests that macrophages possess molecular feedback systems that connect the cargo load to the phagocytic machinery.

The engulfment of cells is a biophysically demanding event and one that macrophages are particularly well-suited to handle. The ability of macrophages to undergo rapid and extensive morphological changes in response to physical and biochemical cues is fundamental to their role as interstitial sentinels. This physical adaptability enables macrophages, which represent only 1–10% of cells in most tissues, to deform and migrate to cover relatively large areas within a tissue. The dynamic morphology of macrophages is mediated by a network of cell surface and intracellular signaling pathways that enable the cells interact with and subsequently conform to their physical environment. Likewise, the engulfment of nucleated cells by macrophages also places physical demands, and thus potential limitations, on macrophages in order to accommodate multiple targets. Here we discuss three key physical parameters of macrophages related to engulfment that may limit their phagocytic capacity: 1) membrane availability, 2) changes in membrane composition, and 3) the physical disruption of phagocytosis signaling networks.

Effects of membrane generation on phagocytosis

For both efferocytosis and Fc-mediated phagocytosis, target internalization is achieved via the extension of macrophage pseudopodia around the bound target, eventually resulting in complete envelopment and internalization of the target in a phagosome. Pseudopodia extension is driven by a dynamic cycle of assembly and disassembly of filamentous actin (F-actin) structures emanating from the actin-rich phagocytic cup region (Figure 1 and reviewed in [2,44]). In addition, the formation of pseudopodia around a cell target requires a ready supply of phagocyte-derived membranes. In order to fully envelope a target, particularly large targets like nucleated cells, macrophages must increase their surface area substantially, with published estimates ranging from 20–500% increases depending on the target [68,69]. Clearly, this magnitude of increase in surface area requires an increase in the supply of membrane material since the lipid bilayer can only be ‘stretched’ ~4% before loss of integrity [77]. The source of the membrane used to build pseudopodia during engulfment has been an area of intense investigation and debate for many years, with previous reports proposing plasma membrane “unwrinkling” or endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-derived membranes as key sources of pseudopodia membrane [78]. While “unwrinkling” of the plasma membrane is important for phagocytosis by neutrophils, it does not appear to be a significant source of additional membrane for macrophage phagocytosis [79]. Instead, it has been found that the extension of pseudopodia during phagocytosis requires the rapid flux of exocytic vesicles targeted to the growing pseudopodia in a process called ‘focal exocytosis.’ (Figure 3).

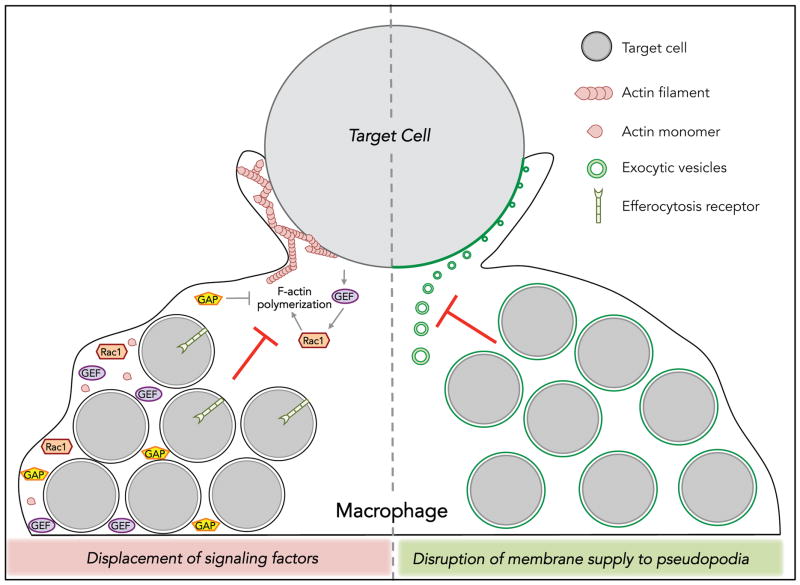

Figure 3. Hypothetical mechanisms of exhausted phagocytosis.

Left side of diagram depicts the potential for engorgement of macrophages with target cells to cause displacement of key signaling molecules away from the phagocytic synapse. For simplicity, only the potential consequences of displacement of Rho GTPase, GEFs, GAPs and F-actin are shown. Model also depicts the potential sequestration of GEFs and GAPs away from the phagocytic machinery due to association with internalized cargo. Right portion of the diagram depicts the potential consequences of internalized cells to disrupt normal endomembrane supply (green circles) to the growing pseudopodia. Such inhibition could be the result of the depletion of the endomembrane supply due to high levels of phagosome formation or by disruption of normal trafficking of membrane vesicles and focal exocytosis at the pseudopodia.

A number of elegant studies examining the composition and molecular mechanisms of pseudopodia assembly during Fc-dependent phagocytosis have revealed that recycling endosomes are the major source of pseudopodia membrane during phagocytosis [80–83]. These studies have shown that disrupting the supply of endomembrane by blocking the exocytosis machinery prevents full pseudopodia extension and results in incomplete or “frustrated” phagocytosis. The Fc-dependent engulfment of large particles (>5μm diameter), including all nucleated cells, is particularly dependent on the generation of pseudopodia membrane and is in fact a rate-limiting step in large particle phagocytosis [84–86]. Presently, the precise mechanisms of endomembrane trafficking to pseudopodia are not clear. However, recent studies indicate that phosphoinositide-dependent Rac signaling in the pseudopodia may function not only in promoting actin polymerization but may also activate exocytic flux to the phagocytic cup [87](Figure 3). Further investigation is required to determine how the rapid internalization of multiple host cells during efferocytosis and ADCP alters the availability of membrane resources and whether such perturbations could effectively limit the subsequent engulfment of host cells. For the most part, our understanding of membrane generation during phagocytosis has arisen from the study of Fc-dependent phagocytosis, with very little work on this topic in the area of efferocytosis. Given that there are indeed striking differences between the efferocytosis and ADCP in the mechanisms of uptake (Figure 1) as well as in phagosome formation [88,89], it will be important to define the role of membrane supply in regulating phagocytic capacity separately for these two processes.

Effects of phagocytosis on macrophage membrane composition

Another important but relatively unexplored issue that could influence macrophage phagocytic potential are changes in the protein composition of the phagocyte membrane resulting from the rapid flux of endomembranes during phagocytosis. This flux is bidirectional in nature in that plasma membrane is simultaneously being ‘added’ to the growing phagosome via focal exocytosis and ‘subtracted’ as a result of invagination and internalization of the phagosome. Indeed a number of studies have shown that the phagosomal membranes formed around IgG-coated synthetic targets are enriched for numerous proteins on these membranes compared to normal plasma membrane [90–92]. Moreover, there is evidence that the phagocyte plasma membrane undergoes substantial, albeit transient, remodeling during engulfment of large particles, with changes in the levels of integral membrane proteins and lipid composition. Early evidence for such remodeling came from the observation that phagocytosis of latex particles caused a change in surface-associated 5′-nucleotidase activity [93]. Later, an elegant study by Grinstein and colleagues employed fluorescence-based microscopy to track several ectopically expressed membrane proteins in the phagocytic cup during ingestion of 8μm diameter IgG-coated beads [85]. Intriguingly, it was shown that some plasma membrane proteins localized transiently to the phagocytic cup in the early stages of phagosome formation, but that the FcγRIIA receptor was selectively retained in the plasma membrane. In the context of efferocytosis, the tethering receptor Tim-4, localizes transiently to the phagosome during PS-dependent phagocytosis [94]. Thus it is possible that the successive uptake of large host cells by macrophages during efferocytosis and ADCP could deplete surface proteins other key components of the phagocytic machinery, thereby effectively reducing the ability of the macrophage to continue to recognize and engulf targets (Figure 3). One caveat to this idea however is that, at least for Fc-dependent phagocytosis, Cannon and Swanson showed that macrophages that were ‘full’ due to the engulfment of large IgG-coated synthetic spheres were still able to bind (but not engulf) IgG-coated erythrocytes, indicating that the availability of Fc receptors was unlikely to be a limiting factor in phagocytosis by engorged macrophages. Clearly, more in-depth studies of changes in macrophage membrane composition, particularly in the context of efferocytosis, will help determine whether and how these cellular trafficking events impact phagocytic capacity.

Cargo-induced changes in the regulation of cytoskeleton signaling networks

Mechanosensing – the capacity of cells to respond to mechanical stimuli (i.e. applied force) through alterations in biochemical signaling (mechanotransduction) – could play an important role in regulating feedback systems that control phagocytic capacity. Mechanosensing is carried out by many different types of cells in a wide range of tissue contexts as a means for cellular adaptation to mechanical or distortional forces applied from outside the cell (e.g. shear flow, vascular extravasation, interstitial adhesion from the extracellular matrix) [2,95]. Much has been learned about mechanotransduction pathways in the context of cell motility, extravasation and interstitial migration [96–98]. Certainly at a gross level, phagocytosis and cell motility share many morphological and biochemical features, including receptor-ligand interactions, extensive cytoskeletal remodeling and rapid membrane flux. Here, we discuss mechanosensing in the context of phagocytosis and how the physical stress of internalizing multiple large targets can feedback to control engulfment responses.

At the core of the mechanosensing and phagocytic signaling networks is the Rho family of small GTPases [43,44,99]. These enzymes act as molecular switches to rapidly transmit biophysical and biochemical cues into adaptive cytoskeleton changes affecting migration and phagocytosis. Of particular importance in all forms of phagocytosis are Rac, RhoA and Cdc42, which play key roles in regulating actin and microtubule dynamics throughout the phagocytic process [2,44,96]. Like most GTPases, these enzymes exist in inactive (GDP-bound) and active (GTP-bound) conformations through the actions of large and diverse families of GTPase modifying proteins. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) promote GTP loading and activation of GTPases, while GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) catalyze the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP resulting in the inactivation of the GTPase [100]. The three canonical Rho GTPases (Rac, RhoA, Cdc42) play essential roles in the efficient recruitment and activation of actin-modulating signaling pathways that lead to formation and dynamic regulation of actin and microtubule networks that drive pseudopodia and phagosome formation during phagocytosis [2,44,86]. For our purposes, we will focus on how the function of these GTPases might enable the macrophage to adjust the rate of phagocytosis based on the content of already internalized material in the phagocytes. Since GTPases critically regulate efferocytosis and ADCP (Figure 1), we will discuss studies related to both processes in order to gain a more complete picture of phagocytosis.

A general model for how Rho GTPases function in mechanotransduction has arisen largely from studies of cellular responses to adhesive and shear forces. Rho GTPases can associate directly with different types of cellular membranes via prenylation of C-terminal CAAX domains [100,101]. Although the majority of Rho protein is typically sequestered in the cytosol through interactions with a family of GTPase chaperones called guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs), a fraction of the total pool of Rho proteins are constitutively associated with cellular membranes [100,102]. The constitutive localization of Rho GTPases to membranes places them in close proximity to cytoplasmic domains of membrane-associated signaling proteins as well as signaling lipids. Upon the application of external force, activation of mechanosensing receptors in the membrane lead to rapid activation of nearby Rho GTPases, which in turn activate actin nucleation complexes as well as microtubule dynamics that mediate the morphological changes in response to the stimuli. Considering this general model, how then might Rho GTPases relay the physical characteristics of internalized cargo to the phagocytic machinery? Although still an open question, it is clear from a number of microscopy studies using FRET-based Rho activity reporters that the precise spatiotemporal activation of Rac, RhoA and Cdc42 is critical for pseudopodia formation and phagocytosis (reviewed in [2,43,44]). The uptake of targets by efferocytosis and Fc-mediated phagocytosis occurs most often at regions of membrane extensions on the phagocyte (e.g. filopodia, lamellipodia and membrane protrusions). Flannagan et al demonstrated that cultured macrophages extend thin membrane protrusions from up to ~1μm distance from the main plasma membrane body to capture and pull in antibody-opsonized and apoptotic targets [103]. We and others have observed that the internalization of apoptotic cells occurs most often in lamellipodia regions (Figure 2 and [104]). Also, Nakaya et al observed that among phagocytes that had engulfed four or more apoptotic cells, a single entry point (dubbed a “portal”) was used by multiple targets [104]. This suggests that the sites of engulfment on a macrophage are likely not random but instead coincide with certain regions of the phagocyte cytoskeleton where existing signaling networks are in place to allow for the rapid formation of a phagosome. In vitro studies of macrophages have shown that the engulfment of host cells corresponds to changes in morphology changes such that they adopt a more rounded shape with less extensive regions of active membrane (Figure 2). This rounding up of the macrophage and retraction of lamellipodia coincides with the reduced capacity to engulf targets encountered subsequently. Whether this change in cell shape is a compensatory move to make space for the ingested cells is not known. But as shown in Figure 3, such large-scale changes in phagocyte morphology has the potential to alter the physical localization of key signaling molecules like Rho GTPases, making the cells less able to generate concentrated regions of phagocytic machinery needed to affect cell engulfment (Figure 3). Also, it is possible that changes in the shape of a macrophage caused by engulfing multiple targets could alter the distribution of phagocytic receptors in a way that effectively reduces engulfment (Figure 3). However, as mentioned earlier, Cannon and Swanson convincingly demonstrated that even when macrophages were “full” of engulfed IgG-coated particles, they were still able to effectively bind (but not engulf) antibody-coated erythrocytes [69]. Similarly, macrophages treated with cytoskeleton disrupting agents that prevent phagocytosis, like cytochalasin or colchicine, undergo a similar rounding up, but are still able to bind apoptotic cells very efficiently. Based on these cumulative findings, it seems possible that the signal for macrophages to ‘stop eating’ is mediated by changes in the intracellular signaling networks, including Rho GTPases, caused by the physical displacement of molecules required for cytoskeletal reorganization and target internalization (Figure 3).

Finally, it is also possible that the attenuation of phagocytosis as macrophages become engorged is due to the depletion or sequestration of signaling mediators common to the internalization and phagosome maturation pathways. In real-time, the transition from phagocytic cup formation to entry of a target into the phagolysosomal pathway is very rapid (on the order of minutes) and seamless, at least visually. As macrophages internalize more and more cells, the formation of multiple phagosomes could serve to deplete signaling molecules from the surface, resulting in failure to form new pseudopodia and phagosomes. In support of this, sequestration of key molecules, like monomeric actin, away from nascent pseudopodia can delay the initiation of new phagosomes [2]. It remains to be determined whether cargo-dependent sequestration of other signaling proteins, including GTPases, GEFs and GAPs, can similarly affect the successful engulfment of target cells (Figure 3).

How metabolic cargo from engulfed host cells impacts engulfment

Phagocytosis evolved as a rather sophisticated means for ancient unicellular organisms like Dictyostelium discoideum to capture nutrients from the environment [105]. A few hundred million years later when metazoans appeared, equipped with specialized organ systems for ingesting environmental nutrients, cellular phagocytosis took on more specialized roles in the clearance of pathogens and effete host cells. However, recent insights into the fate of cellular material acquired during host cell engulfment suggest that macrophages have retained some of these ancient capabilities to sense and respond to nutrients acquired through phagocytosis.

Once a host cell has been engulfed by a macrophage, the macromolecular contents of that cargo, including carbohydrates, cholesterols, proteins and nucleic acids, are processed through the phagolysosomal pathway. Macrophages must either incorporate or offload these newly acquired resources in order to maintain a healthy metabolic program. Considering that a single macrophage can contain 10 or more host cells at once, the potential metabolic load acquired by macrophages can be many times the normal levels for the phagocyte. The breakdown of engulfed cells via the phagolysosomal pathway has been investigated intensely for many years (reviewed in [33,106–108]). Here we will focus on how the metabolic byproducts of host cell digestion feedback to control phagocytosis. Since this process has been studied in-depth in the context of efferocytosis more so than ADCP in recent years, we will focus our discussion primarily on the metabolic consequences of efferocytosis, with relevant findings related to ADCP discussed where appropriate.

Sensing lipids

The acquisition and processing of lipids, particularly fats, sterols and phospholipids, via cell engulfment has been shown to have important consequences on the phagocytic potential of macrophages. As far as we know, the lipids derived from engulfed cells are not uniquely modified inside the macrophage phagosome and thus are essentially indistinguishable from those of the host macrophage, making source-tracing of these basic molecules during phagocytosis a major challenge. Still, a number of studies have established a firm linkage between lipid-sensing and the phagocytic machinery in macrophages. Li et al found that exposure of macrophages to exogenous saturated free fatty acid (FFA) complexed with albumin inhibited the engulfment of apoptotic cells [109]. Interestingly, FFA treatment also altered the lipid composition of macrophage plasma membranes and decreased PI3K/AKT activation, suggesting that disruptions in normal lipid homeostasis could affect the capacity of macrophages to maintain efficient phagocytic signaling. Along these lines, two studies by Ravichandran and colleagues have shown that the ingestion of apoptotic cells by macrophages is linked to cholesterol efflux. In one study, the uptake of apoptotic cells (but not necrotic cells, IgG-opsonized cells or synthetic beads) by macrophages induced the expression of the lipid transporter Abca1 in macrophages thereby increasing their efflux of cholesterol via ABCA1-mediated generation of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) complexes [110]. More recently, this group found that signaling downstream of the PS receptor Bai1 was important for upregulation of Abca1 and cholesterol efflux during efferocytosis, thereby connecting for the first time the phagocytic machinery to the cholesterol sensing apparatus of macrophages [111] (Figure 4). Interestingly, Yvan-Charvet et al reported that macrophages lacking ABCA1 (or the related ABCG1) did not have a defect in phagocytosis, but rather these mutant macrophages were much more likely to undergo apoptosis following engulfment of apoptotic cells [112]. This suggests that the inappropriate handling of cholesterol during cell phagocytosis can trigger stress-induced cell death, possibly via direct means (oxidative stress) or indirectly through the failure to produce HDL to offset apoptosis-triggering oxidized lipids.

Figure 4. Regulating phagocytic activity via metabolic feedback pathways.

Diagram depicting four metabolic feedback pathways that have been shown to link engulfed host cells to the phagocytic machinery. The role of lipid metabolism in macrophage phagocytosis is shown for: ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux, response to oxidized phospholipids (oxPL), and activation of nuclear receptors LXR and PPARγ. The role of carbohydrate metabolism and mitochondrial function are also shown. Solid arrows indicate components of the pathways that have been confirmed, while dashed arrows indicate pathways that have not been formally elucidated. HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Phospholipids (PL) from apoptotic cells play many key roles in efferocytosis, including acting as ligands for phagocytosis receptors (PS, PE)[22], stimulation of engulfment signaling pathways (lysoPS, sphingosine-1 phosphate)[113,114], and chemotaxis of macrophages toward apoptotic cells (lysoPC)[115]. In addition, oxidized phospholipids (oxPL) have been known for some time to be perceived by the immune system as altered self and as such can act as “danger” signals to drive activation of innate and adaptive immunity [116,117]. It is well known that apoptosis (and other forms of stress-induced cell death) leads to the accumulation of oxidized PL (oxPL) in cell corpses due to the inactivation of oxidative stress pathways [118,119]. Therefore, internalization of dying corpses results in the acquisition by macrophages of substantial loads of oxPL from the internalized cells, with important consequences on macrophage homeostasis and phagocytic function (Figure 4).

As a danger signal, oxPL can induce a plethora of oxidative stress responses in macrophages up to and including apoptosis. Perhaps the best-studied paradigm for this is in intimal macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. Here, the uptake of oxidized lipids promotes the conversion of macrophages to lipid-laden foam cells, which adopt altered functions in many ways, including ineffective efferocytosis [120,121]. In studies using the prototypical bioactive PL, 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-3-glycero-phosphorylcholine (PAPC), the uptake of oxPAPC was found to have dramatic effects on the ability of macrophages to engulf host cells [112,122]. While it is clear that exposure of macrophages to oxPL can impair phagocytic function, the mechanisms behind this effect are just beginning to be elucidated. In a transcriptomics analysis of oxPAPC-treated macrophages, Kadl et al found that oxPAPC elicited a macrophage transcriptional profile quite distinct from untreated macrophages or M1 and M2 polarized macrophages, leading the authors to create a new appellation for oxPL-treated macrophages: “Mox” [122]. Not surprisingly, many of the genes modulated by oxPAPC treatment were associated with redox regulation, including HO-1, Srxn1, and Txnrd1. Transcription factor analyses revealed that the redox-regulated transcription factor Nrf2 was uniquely upregulated in Mox macrophages compared to other macrophage populations, and that deletion of Nrf2 abrogated many of the changes in gene expression characteristic of Mox macrophages. Intriguingly, it was also shown that the Mox phenotype was associated with significantly contracted actin network and more rounded cell bodies, as well as a dramatically reduced capacity to migrate or engulf apoptotic cells and synthetic beads. While the mechanisms underlying these morphological and functional defects in Mox macrophages remain to be elucidated, based on studies linking the uptake of oxidized LDL by macrophages to defective phagocytosis of apoptotic cells via changes in RhoA activation [120,123], it seems reasonable to hypothesize that oxPL could alter the ability of macrophages to internalize cell targets via disruption of Rho GTPase signaling (Figure 4).

Nuclear receptors (NR) are a large family of DNA-binding proteins that modulate gene transcription in response to steroid ligands. Three classes of these receptors have recently been shown to regulate efferocytosis: peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor γ/δ (PPARγ/δ) which recognize fatty acids and prostaglandins; liver X receptor α/β (LXRα/β) which recognize oxysterols; and retinoic X receptor α (RXRα) which recognizes retinoids [121,124,125]. In separate studies, deletion of these NRs in macrophages was found to dramatically impair the ability of macrophages to engulf apoptotic cells [11,13,126]. Collectively, these studies revealed that the loss of any of these NRs caused a significant defect in efferocytosis both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, it was shown that the engulfment of apoptotic cells increases the expression of a number of efferocytosis-related genes (e.g. phagocytic receptors, cytokines), providing a NR-dependent positive feedback loop to promote the continued clearance of apoptotic cells (Figure 4). This upregulation of pro-phagocytosis genes enables macrophages to maintain and even increase their phagocytic capacity over time, and some of these ‘programming’ signals conveyed by apoptotic cells are greatly impaired in the absence of PPARδ and LXRα/β [11,13]. Interestingly, in the case of PPARδ, in vitro microscopic analysis of efferocytosis revealed that the percentage of macrophages engulfing one apoptotic target was similar between WT and PPARδ−/− macrophages; however, PPARδ−/− macrophages showed a dramatic defect in the engulfment of two or more targets by individual macrophages [11]. With respect to the importance of these NRs on Fc-mediated engulfment of Ig-coated cells, it was shown loss of PPARδ did not affect macrophage engulfment of Ig-opsonized targets [11], while Rozer et al. reported that macrophages from PPARγ, and RXRα mice had strong defects in engulfment of IgG and IgM-coated erythrocytes in vitro [126]. Thus it appears that NRs play a positive role in cell phagocytosis by mediating expression of phagocytic genes that govern the magnitude and duration of efferocytosis responses. However, it is noteworthy that at present neither the precise ligands nor source of ligands for the NRs in the context of cell phagocytosis are known (Figure 4).

Carbohydrate sensing

Carbohydrates provide a ready source for intracellular ATP production, and it has been known for many years that disruption of cellular energy homeostasis can impact the phagocytic capacity of macrophages. Indeed, treatment of macrophages with exogenous saccharides like glucose and sucrose impairs their ability to engulf IgG-coated targets and apoptotic cells [69,127]. Cannon and Swanson showed that provision of excess sucrose caused macrophages to become vacuolated and lose phagocytic capacity [69]. This effect was transient, as addition of invertase, a sucrose-hydrolyzing enzyme, to macrophages rapidly reversed this impairment. In the context of efferocytosis, Park et al similarly found that the presence of glucose in macrophage growth medium had a marked inhibitory effect on the capacity of macrophages to engulf apoptotic cells [127]. More recently, the autophagic machinery has been implicated in cellular phagocytosis in a process called LC3 (microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3)-associated phagocytosis (LAP) [128–130]. Canonical autophagy is a cellular stress response to nutrient deprivation whereby cellular contents are scavenged to supply the base energy needs of the cell (Reviewed in [2,44,56,104,131,132]). Interestingly, the execution of LAP requires both efferocytosis and autophagic machinery and is triggered in circumstances where macrophage recognition of cellular targets by receptors, including PS and Fc receptors, occurs in the context of TLR activation [6]. Recently, LAP-dependent engulfment of dead cells was shown to enhance the rate of corpse degradation (compared to conventional phagocytosis pathways) and also was shown to prevent aberrant inflammatory responses and autoimmunity in response to dead cells in mice [133]. Considering the central role of autophagy in cellular metabolism, it will be fascinating to learn whether and how cell engulfment by LAP affects the generation and function of internalized cell-derived macromolecules on macrophage phagocytosis.

Mitochondria are the central regulators of energy production in cells, so it is not surprising that the mitochondrial function of macrophages is altered as a consequence of host cell engulfment. Park et al demonstrated that soon after the engulfment of apoptotic cells (but not synthetic prey), the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) of phagocytes increased, although ATP levels in the phagocytes remained constant [127]. These authors found that an uncoupling protein called UCP2, an inner mitochondrial membrane responsible for uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production, was upregulated in macrophages after engulfment of apoptotic cells (but not synthetic beads, E. coli or zymosan particles). Macrophages deficient in UCP2 showed a strong defect in apoptotic cell uptake in vitro and in vivo, while ectopic expression of UCP2 substantially enhanced the number of apoptotic cell taken up by individual macrophages in vitro [127]. It is interesting to note that this study showed that the transcriptional upregulation of Ucp2 during efferocytosis was a key mechanism for modulating the uncoupling activity during phagocytosis, although the precise molecular links between engulfed cargo and UCP2-mediated mitochondrial function remain to be determined (Figure 4). It is not currently known whether UCP2 similarly controls the phagocytic potential macrophages for mAb-opsonized targets.

Reduced phagocytosis of targets cells via trogocytosis

Therapy with mAb can also profoundly alter target cells and their susceptibility to ADCP. Following mAb ligation of membrane bound antigens, target cells can bind FcγR expressing effector cells including macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils and NK cells, forming an immunological synapse. This is followed trogocytosis – an ordered sequence of activation events that result in effector cell removal of the mAb-antigen complex together with a small amount of cell membrane in a manner that does not affect target cell viability (reviewed in [134]). This process of trogocytosis was first noted to occur after mAb therapy of CLL with rituximab and subsequently found to complicate treatment with ofatumumab in a dose dependent manner [74,75,135,136]. These data and associated correlative studies suggest that exhaustion of macrophage ADCP following opsonization of large numbers of circulating CLL cells increases the exposure of mAb opsonized cells to effectors cells that remove CD20 from the CLL cell membranes by trogocytosis resulting in acquired CLL resistance to mAb mediated cytotoxicity as recently reviewed [134]. Clinical trials using low dose higher frequency rituximab designed to mitigate effector cell exhaustion have shown sustained therapeutic efficacy with considerably reduced loss of membrane CD20 on circulating CLL cells suggesting that optimized drug regimens could decrease trogocytosis and improve therapeutic outcome [72,73,137,138]. The relevance of trogocytosis-like events in efferocytosis and how this process might affect the clearance of dying cells has not been investigated.

Developing ways to boost engulfment for therapeutic gain

Therapeutic mAb that utilize innate immune mediated toxicity of malignant cells are effective but non-curative because they are not capable of killing all malignant cells capable of replication. Improving macrophage ADCP could increase the therapeutic efficacy of mAb. Achieving this goal will require a considerably improved understanding of the mechanisms of ADCP and how target cells escape phagocytosis. Some progress has been made in this regard, with mAb engineering producing mAb with marked increased affinity for antigen and FcγR that are more effective at activating ADCP [139]. Glycoengineered anti-CD20 mAbs for example were recently shown to enhance B cell depletion by increasing ADCP by Kupffer cells in the liver [63]. Along these lines, the use of better mAb dosing strategies could help avoid macrophage exhaustion by limiting the loss of target antigens by trogocytosis. However, a major obstacle to improved therapeutic outcome remains the finite capacity of tissue resident macrophages to phagocytose target cells. Overcoming this obstacle will require a major effort to understand the limiting components of ADCP followed by the testing of interventions that could overcome these limitations. Based on current knowledge, potential approaches could include combination therapies of mAb with drugs that increase innate immune activation (e.g. TLR agonists), therapy with mAb constructs with more potent complement activation ability or that ligate more than one FcγR molecule, and targeting of inhibitors of macrophage activation such as FcγRIIB. However, major progress with probably only be achieved using data that precisely define the molecular limitations of phagocytic capacity and thus provides molecular targets for manipulation.

The inefficient clearance of apoptotic cells can trigger deleterious immune responses, such as loss of self-tolerance, and can also impair the resolution of tissue inflammation and wound healing. This concept is supported by many studies linking defective recognition of PS on apoptotic cells by macrophages to a variety of immune dysfunctions [20]. Accordingly, preclinical and clinical studies designed to utilize efferocytosis for therapeutic gain are currently dominated by approaches centered on PS recognition [39,140]. However, to meet the therapeutic goal of enhancing apoptotic cell clearance, it will also be necessary to consider approaches that increase the phagocytic capacity of macrophages so that they are able to rapidly process the increased burden caused by such phagocytosis-promoting therapies.

Acknowledgments

The MRE Laboratory is funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI114554, AI027767). CSZ is grateful for support from the University of Rochester Wilmot Foundation.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- ADCP

antibody-dependent cell phagocytosis

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CR

complement receptor

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- FcR

Fc receptor

- FFA

free fatty acid

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GAP

GTPase-activating protein

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GDI

guanosine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor

- GDP

guanosine diphosphate

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- ITAM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

- ITP

immune thrombocytopenia

- LAP

LC3-associated phagocytosis

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- NK cells

natural killer cells

- NR

nuclear receptor

- oxPL

oxidized phospholipid

- PAPC

1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-3-glycero-phosphorylcholine

- PL

phospholipid

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

References

- 1.Penberthy KK, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell recognition receptors and scavenger receptors. Immunol Rev. 2015;269:44–59. doi: 10.1111/imr.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman SA, Grinstein S. Phagocytosis: receptors, signal integration, and the cytoskeleton. Immunol Rev. 2014;262:193–215. doi: 10.1111/imr.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf AJ, Underhill SM. In: Phagocytosis. Biswas SK, Mantovani A, editors. Springer Science/Business Media; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott MR, Ravichandran KS. Clearance of apoptotic cells: implications in health and disease. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:1059–1070. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poon IKH, Lucas CD, Rossi AG, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell clearance: basic biology and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nri3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green DR, Oguin TH, Martinez J. The clearance of dying cells: table for two. Cell Death Differ. 2016 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gul N, van Egmond M. Antibody-Dependent Phagocytosis of Tumor Cells by Macrophages: A Potent Effector Mechanism of Monoclonal Antibody Therapy of Cancer. Cancer Research. 2015;75:5008–5013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiskopf K, Weissman IL. Macrophages are critical effectors of antibody therapies for cancer. MAbs. 2015;7:303–310. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1011450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arandjelovic S, Ravichandran KS. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in homeostasis. Nature Immunology. 2015;16:907–917. doi: 10.1038/ni.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagata S, Hanayama R, Kawane K. Autoimmunity and the Clearance of Dead Cells. Cell. 2010;140:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Morel CR, Heredia JE, Mwangi JW, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Goh YPS, Eagle AR, Dunn SE, Awakuni JUH, Nguyen KD, Steinman L, Michie SA, Chawla A. PPAR-δ senses and orchestrates clearance of apoptotic cells to promote tolerance. Nat Med. 2009;15:1266–1272. doi: 10.1038/nm.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miyasaka K, Aozasa K, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Nagata S. Autoimmune disease and impaired uptake of apoptotic cells in MFG-E8-deficient mice. Science. 2004;304:1147–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1094359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A-Gonzalez N, Bensinger SJ, Hong C, Beceiro S, Bradley MN, Zelcer N, Deniz J, Ramirez C, DIaz M, Gallardo G, de Galarreta CR, Salazar J, Lopez F, Edwards P, Parks J, Andujar M, Tontonoz P, Castrillo A. Apoptotic Cells Promote Their Own Clearance and Immune Tolerance through Activation of the Nuclear Receptor LXR. Immunity. 2009:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juncadella IJ, Kadl A, Sharma AK, Shim YM, Hochreiter-Hufford A, Borish L, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell clearance by bronchial epithelial cells critically influences airway inflammation. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CS, Penberthy KK, Wheeler KM, Juncadella IJ, Vandenabeele P, Lysiak JJ, Ravichandran KS. Boosting Apoptotic Cell Clearance by Colonic Epithelial Cells Attenuates Inflammation In Vivo. Immunity. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uderhardt S, Herrmann M, Oskolkova OV, Aschermann S, Bicker W, Ipseiz N, Sarter K, Frey B, Rothe T, Voll R, Nimmerjahn F, Bochkov VN, Schett G, Krönke G. 12/15-Lipoxygenase Orchestrates the Clearance of Apoptotic Cells and Maintains Immunologic Tolerance. Immunity. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami Y, Tian L, Voss OH, Margulies DH, Krzewski K, Coligan JE. CD300b regulates the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells via phosphatidylserine recognition. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1746–1757. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jun J-I, Kim K-H, Lau LF. The matricellular protein CCN1 mediates neutrophil efferocytosis in cutaneous wound healing. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7386. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujimori T, Grabiec AM, Kaur M, Bell TJ, Fujino N, Cook PC, Svedberg FR, MacDonald AS, Maciewicz RA, Singh D, Hussell T. The Axl receptor tyrosine kinase is a discriminator of macrophage function in the inflamed lung. 2015;8:1021–1030. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimani SG, Geng K, Kasikara C, Kumar S, Sriram G, Wu Y, Birge RB. Contribution of Defective PS Recognition and Efferocytosis to Chronic Inflammation and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2014;5:566. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baxter AA, Hulett MD, Poon IK. The phospholipid code: a key component of dying cell recognition, tumor progression and host–microbe interactions. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:1893–1905. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segawa K, Nagata S. An Apoptotic “Eat Me” Signal: Phosphatidylserine Exposure. Trends Cell Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyanishi M, Tada K, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kitamura T, Nagata S. Identification of Tim4 as a phosphatidylserine receptor. Nature. 2007;450:435–439. doi: 10.1038/nature06307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian L, Choi S-C, Murakami Y, Allen J, Morse HC, Qi C-F, Krzewski K, Coligan JE. p85α recruitment by the CD300f phosphatidylserine receptor mediates apoptotic cell clearance required for autoimmunity suppression. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3146. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park D, Tosello-Trampont A-C, Elliott MR, Lu M, Haney LB, Ma Z, Klibanov AL, Mandell JW, Ravichandran KS. BAI1 is an engulfment receptor for apoptotic cells upstream of the ELMO/Dock180/Rac module. Nature. 2007;450:430–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savill J, Dransfield I, Hogg N, Haslett C. Vitronectin receptor-mediated phagocytosis of cells undergoing apoptosis. Nature. 1990;343:170–173. doi: 10.1038/343170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert ML, Kim JI, Birge RB. alphavbeta5 integrin recruits the CrkII-Dock180-rac1 complex for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:899–905. doi: 10.1038/35046549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y, Singh S, Georgescu M-M, Birge RB. A role for Mer tyrosine kinase in alphavbeta5 integrin-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:539–553. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seitz HM, Camenisch TD, Lemke G, Earp HS, Matsushima GK. Macrophages and dendritic cells use different Axl/Mertk/Tyro3 receptors in clearance of apoptotic cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:5635–5642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dransfield I, Zagórska A, Lew ED, Michail K, Lemke G. Mer receptor tyrosine kinase mediates both tethering and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Cell Death and Disease. 2015;6:e1646. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishi C, Toda S, Segawa K, Nagata S. Tim4- and MerTK-mediated engulfment of apoptotic cells by mouse resident peritoneal macrophages. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2014;34:1512–1520. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01394-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinchen JM, Ravichandran KS. Journey to the grave: signaling events regulating removal of apoptotic cells. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120:2143–2149. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinchen JM, Ravichandran KS. Phagosome maturation: going through the acid test. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:781–795. doi: 10.1038/nrm2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flannagan RS, Jaumouillé V, Grinstein S. The cell biology of phagocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2012;7:61–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sosale NG, Spinler KR, Alvey C, Discher DE. Macrophage engulfment of a cell or nanoparticle is regulated by unavoidable opsonization, a species-specific “Marker of Self” CD47, and target physical properties. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;35:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, Lagenaur CF, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288:2051–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gardai SJ, McPhillips KA, Frasch SC, Janssen WJ, Starefeldt A, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Bratton DL, Oldenborg PA, Michalak M, Henson PM. Cell-surface calreticulin initiates clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of LRP on the phagocyte. Cell. 2005;123:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Pang WW, Jaiswal S, Gibbs KD, van Rooijen N, Weissman IL. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 2009;138:286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chao MP, Majeti R, Weissman IL. Programmed cell removal: a new obstacle in the road to developing cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;12:58–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blazar BR, Lindberg FP, Ingulli E, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Oldenborg PA, Iizuka K, Yokoyama WM, Taylor PA. CD47 (integrin-associated protein) engagement of dendritic cell and macrophage counterreceptors is required to prevent the clearance of donor lymphohematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:541–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okazawa H, Motegi S-I, Ohyama N, Ohnishi H, Tomizawa T, Kaneko Y, Oldenborg P-A, Ishikawa O, Matozaki T. Negative regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by the CD47-SHPS-1 system. J Immunol. 2005;174:2004–2011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willingham SB, Volkmer J-P, Gentles AJ, Sahoo D, Dalerba P, Mitra SS, Wang J, Contreras-Trujillo H, Martin R, Cohen JD, Lovelace P, Scheeren FA, Chao MP, Weiskopf K, Tang C, Volkmer AK, Naik TJ, Storm TA, Mosley AR, Edris B, Schmid SM, Sun CK, Chua M-S, Murillo O, Rajendran P, Cha AC, Chin RK, Kim D, Adorno M, Raveh T, Tseng D, Jaiswal S, Enger PØ, Steinberg GK, Li G, So SK, Majeti R, Harsh GR, van de Rijn M, Teng NNH, Sunwoo JB, Alizadeh AA, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pertz O. Spatio-temporal Rho GTPase signaling - where are we now? Journal of Cell Science. 2010;123:1841–1850. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao Y, Finnemann SC. Regulation of phagocytosis by Rho GTPases. smallgtpases. 2015;6:89–99. doi: 10.4161/21541248.2014.989785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tosello-Trampont AC. Engulfment of Apoptotic Cells Is Negatively Regulated by Rho-mediated Signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:49911–49919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakaya M, Tanaka M, Okabe Y, Hanayama R, Nagata S. Opposite effects of rho family GTPases on engulfment of apoptotic cells by macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8836–8842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guilluy C, Garcia-Mata R, Burridge K. Rho protein crosstalk: another social network? Trends Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huynh ML, Fadok VA, Henson PM. Phosphatidylserine-dependent ingestion of apoptotic cells promotes TGF-beta1 secretion and the resolution of inflammation. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109:41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI11638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyake Y, Asano K, Kaise H, Uemura M, Nakayama M, Tanaka M. Critical role of macrophages in the marginal zone in the suppression of immune responses to apoptotic cell-associated antigens. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:2268–2278. doi: 10.1172/JCI31990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qiu CH, Miyake Y, Kaise H, Kitamura H, Ohara O, Tanaka M. Novel Subset of CD8 + Dendritic Cells Localized in the Marginal Zone Is Responsible for Tolerance to Cell-Associated Antigens. J Immunol. 2009;182:4127–4136. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang M, Xu S, Han Y, Cao X. Apoptotic cells attenuate fulminant hepatitis by priming Kupffer cells to produce interleukin-10 through membrane-bound TGF-β. Hepatology. 2011;53:306–316. doi: 10.1002/hep.24029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong K, Valdez PA, Tan C, Yeh S, Hongo J-A, Ouyang W. Phosphatidylserine receptor Tim-4 is essential for the maintenance of the homeostatic state of resident peritoneal macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:8712–8717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910929107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casanova-Acebes M, Pitaval C, Weiss LA, Nombela-Arrieta C, Chèvre R, A-Gonzalez N, Kunisaki Y, Zhang D, van Rooijen N, Silberstein LE, Weber C, Nagasawa T, Frenette PS, Castrillo A, Hidalgo A. Rhythmic modulation of the hematopoietic niche through neutrophil clearance. Cell. 2013;153:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schneider C, Nobs SP, Heer AK, Kurrer M, Klinke G, van Rooijen N, Vogel J, Kopf M. Alveolar macrophages are essential for protection from respiratory failure and associated morbidity following influenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004053. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez-Manzanet R, Sanjuan MA, Wu HY, Quintana FJ, Xiao S, Anderson AC, Weiner HL, Green DR, Kuchroo VK. T and B cell hyperactivity and autoimmunity associated with niche-specific defects in apoptotic body clearance in TIM-4-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:8706–8711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910359107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood W, Turmaine M, Weber R, Camp V, Maki RA, McKercher SR, Martin P. Mesenchymal cells engulf and clear apoptotic footplate cells in macrophageless PU. 1 null mouse embryos. Development. 2000;127:5245–5252. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monks J, Smith-Steinhart C, Kruk ER, Fadok VA, Henson PM. Epithelial cells remove apoptotic epithelial cells during post-lactation involution of the mouse mammary gland. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:586–594. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.065045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greenlee-Wacker MC. Clearance of apoptotic neutrophils and resolution of inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2016;273:357–370. doi: 10.1111/imr.12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Back DZ, Kostova EB, van Kraaij M, van den Berg TK, van Bruggen R. Of macrophages and red blood cells; a complex love story. Front Physiol. 2014;5:9. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zent CS, Kay NE. Autoimmune complications in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2010;23:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gül N, Babes L, Siegmund K, Korthouwer R, Bögels M, Braster R, Vidarsson G, Hagen ten TLM, Kubes P, van Egmond M. Macrophages eliminate circulating tumor cells after monoclonal antibody therapy. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014;124:812–823. doi: 10.1172/JCI66776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Montalvao F, Garcia Z, Celli S, Breart B, Deguine J, van Rooijen N, Bousso P. The mechanism of anti-CD20–mediated B cell depletion revealed by intravital imaging. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123:5098–5103. doi: 10.1172/JCI70972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grandjean CL, Montalvao F, Celli S, Michonneau D, Breart B, Garcia Z, Perro M, Freytag O, Gerdes CA, Bousso P. Intravital imaging revealsimproved Kupffer cell-mediatedphagocytosis as a mode of actionof glycoengineered anti-CD20antibodies. 2016:1–6. doi: 10.1038/srep34382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kamangar E, Zhao W. Hemophagocytosis in a patient with persistent chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:2149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-493072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Church AK, VanDerMeid KR, Baig NA, Baran AM, Witzig TE, Nowakowski GS, Zent CS. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody-dependent phagocytosis of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells by autologous macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;183:90–101. doi: 10.1111/cei.12697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schlam D, Bagshaw RD, Freeman SA, Collins RF, Pawson T, Fairn GD, Grinstein S. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase enables phagocytosis of large particles by terminating actin assembly through Rac/Cdc42 GTPase-activating proteins. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8623. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Firdessa R, Oelschlaeger TA, Moll H. Identification of multiple cellular uptake pathways of polystyrene nanoparticles and factors affecting the uptake: relevance for drug delivery systems. Eur J Cell Biol. 2014;93:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lam J, Herant M, Dembo M, Heinrich V. Baseline mechanical characterization of J774 macrophages. Biophys J. 2009;96:248–254. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cannon GJ, Swanson JA. The macrophage capacity for phagocytosis. J Cell Sci. 1992;101(Pt 4):907–913. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parnaik R, Raff MC, Scholes J. Differences between the clearance of apoptotic cells by professional and non-professional phagocytes. CURBIO. 2000;10:857–860. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, Fink AM, Busch R, Mayer J, Hensel M, Hopfinger G, Hess G, Grünhagen von U, Bergmann M, Catalano J, Zinzani PL, Caligaris-Cappio F, Seymour JF, Berrebi A, Jäger U, Cazin B, Trneny M, Westermann A, Wendtner CM, Eichhorst BF, Staib P, Bühler A, Winkler D, Zenz T, Böttcher S, Ritgen M, Mendila M, Kneba M, Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S International Group of InvestigatorsGerman Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams ME, Densmore JJ, Pawluczkowycz AW, Beum PV, Kennedy AD, Lindorfer MA, Hamil SH, Eggleton JC, Taylor RP. Thrice-weekly low-dose rituximab decreases CD20 loss via shaving and promotes enhanced targeting in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Immunol. 2006;177:7435–7443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aue G, Lindorfer MA, Beum PV, Pawluczkowycz AW, Vire B, Hughes T, Taylor RP, Wiestner A. Fractionated subcutaneous rituximab is well-tolerated and preserves CD20 expression on tumor cells in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95:329–332. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.012484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Beum PV, Peek EM, Lindorfer MA, Beurskens FJ, Engelberts PJ, Parren PWHI, van de Winkel JGJ, Taylor RP. Loss of CD20 and bound CD20 antibody from opsonized B cells occurs more rapidly because of trogocytosis mediated by Fc receptor-expressing effector cells than direct internalization by the B cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;187:3438–3447. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baig NA, Taylor RP, Lindorfer MA, Church AK, LaPlant BR, Pettinger AM, Shanafelt TD, Nowakowski GS, Zent CS. Induced Resistance to Ofatumumab-Mediated Cell Clearance Mechanisms, Including Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity, in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. The Journal of Immunology. 2014;192:1620–1629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Erwig LP, Gordon S, Walsh GM, Rees AJ. Previous uptake of apoptotic neutrophils or ligation of integrin receptors downmodulates the ability of macrophages to ingest apoptotic neutrophils. Blood. 1999;93:1406–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hamill OP, Martinac B. Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:685–740. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huynh KK, Kay JG, Stow JL, Grinstein S. Fusion, fission, and secretion during phagocytosis. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:366–372. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00028.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hallett MB, Dewitt S. Ironing out the wrinkles of neutrophil phagocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]