Abstract

Background

Prior studies have found that social rejection is associated with increases in negative affect, distress, and hostility. Fewer studies, however, have examined the impact of social rejection on alcohol use, and no known studies have tested whether the impact of social rejection by close others differs from social rejection by acquaintances in its association with subsequent drinking.

Methods

Participants completed event-contingent reports of their social interactions and alcohol use for 14 consecutive days on smartphones. Multilevel negative binomial regression models tested whether experiencing more social rejection than usual was associated with increased drinking, and whether this association was stronger when participants were rejected by close others (e.g. friends, spouses, family members) versus strangers or acquaintances.

Results

Results showed a significant interaction between social rejection and relationship closeness. On days characterized by rejection by close others, the likelihood of drinking significantly increased. On days characterized by rejection by acquaintances, by contrast, there was no increase in the likelihood of drinking. There was no main effect of rejection on likelihood of drinking.

Conclusions

These results suggest that relationship type is a key factor in whether social rejection translates to potentially harmful behaviors, such as increased alcohol use. This finding is in contrast to many laboratory paradigms of rejection, which emphasize rejection and ostracism by strangers rather than known others. In the more naturalistic setting of measuring social interactions on smartphone in daily life, however, our findings suggest that only social rejection delivered by close others, and not strangers, led to subsequent drinking.

Keywords: rejection, social rejection, daily diary, alcohol use

Introduction

Social rejection threatens one of the most fundamental human needs: the need to belong and experience social bonds. Numerous laboratory studies have shown that social rejection increases arousal and negative affect, and lowers self-esteem (Gerber and Wheeler, 2009). Social rejection also affects interpersonal behavior: rejection can be associated with increased efforts to affiliate, such as greater submissive behaviors thought to ingratiate the rejected individual to others (Romero-Canyas et al., 2010; Williams, 2001). On the other hand, studies have also found that social rejection increases aggressive and hostile behaviors (Leary et al., 2006). It is surprising that relatively few studies have examined directly the impact of social rejection on maladaptive regulatory behaviors such as alcohol use, given that multiple theories of use dating from the tension reduction hypothesis (Conger, 1956) posit that individuals drink to decrease stress and negative affect, which are known correlates of social rejection. Further, social drinking has been suggested as a way in which individuals lessen fears of rejection and increase perceived social ties and bonding with others (Fairbairn and Sayette, 2014). Thus, there are two potential reasons that individuals might cope with experiences of social rejection by drinking more than usual. First, due to dysregulating aspects of social rejection including increased arousal and negative affect, individuals may turn to alcohol use as a means of stress reduction (e.g., Chaplin et al., 2008). Second, social rejection may prompt individuals to seek greater social belonging and euphoria commonly found in social drinking.

Interestingly, few laboratory studies of social rejection account for differences in social rejection depending on relationship closeness. Many experimental paradigms of social rejection, such as Cyberball (Williams et al., 2000; Williams and Jarvis, 2006), activate ostracism from strangers. Yet more recent work using both close others and strangers within the Cyberball paradigm has found that the responses from social rejection differ depending on the closeness of the interactant. One study found that both children and mothers experienced greater neural activation in a task when rejected by one another versus a stranger (Sreekrishnan et al., 2014). In another study of children and their friends, researchers found that rejection by one’s best friend versus a stranger elicited a stronger neural response in well-adjusted children (Baddam et al., 2016). Both theory and research have shown that threats from those from within one’s close social network may be seen as threatening the secure base of attachment relationships and thus are particularly damaging (Charuvastra and Cloitre, 2008). It follows that experiences of rejection from inside one’s social network would be especially hurtful, thereby driving maladaptive regulatory behaviors. Further, an assumption of many studies of close relationships including friendships, romantic partnerships, and parent-child relationships is that there is something inherently more important, or perhaps more influential, about closer relationships as opposed to acquaintanceships. Given the potential importance of close relationships in driving maladaptive regulatory behaviors, this study will examine whether the level of familiarity of the person in each social interaction moderates the level of social rejection in predicting alcohol use.

Recent theory and research from the alcohol literature have suggested that social drinking may be reinforcing because of processes related to social comfort and ties. Specifically, this research hypothesizes that social drinking eases threats to the self, lessens fears of social rejection, and induces positive affect and euphoria as a result (Fairbairn and Sayette, 2014). Given that social rejection is seen as a threat to the social self and to feelings of social belonging (Baumeister and Leary, 1995), it is possible that participants rejected by close others are engaging in social drinking as a way to regain a sense of social belonging.

Findings are mixed as to whether feelings of social rejection lead to increased drinking behaviors. One of the few studies that found that social rejection was associated with increased drinking involved a laboratory paradigm of social exclusion and drinking behaviors (Rabinovitz, 2014). Participants were randomized to either a social exclusion or social inclusion condition, which consisted of being told that their personality type was consistent with individuals who “end up alone” later in life versus being told their personality indicated that they would have positive and lasting relationships in the future. After the manipulation, participants were allowed to drink and also rated how much they would be willing to pay for a drink. Results showed that excluded individuals drank more alcohol than participants in the social inclusion condition. However, this study was limited in that it used a “pseudo-drinking” paradigm rather than measuring actual alcohol consumption under real world conditions. In addition, laboratory studies of social rejection may not translate to social rejection that occurs during the course of individuals’ daily lives. Importantly however, by using a paradigm that invoked rejection in terms of lasting close relationships rather than acquaintanceships, the study was able to find a significant link between social rejection and alcohol consumption. Other laboratory studies of rejection have found no association between rejection and alcohol use. For example, one study of rejection by strangers found no difference in drinking behaviors in rejected versus non-rejected participants, with some participants even showing decreased drinking behaviors following ostracism experiences (Bacon et al., 2015).

Many of the limitations in the laboratory paradigms may be addressed by using real-world assessment methodologies, termed daily diary studies, in which participants report on their everyday experiences rather than responding to the more controlled, but less ecologically valid, context of the laboratory setting. However, the few daily diary studies of social interactions and drinking behavior that have been published suggest that the association between social rejection and drinking is not straightforward. For example, one study found that low anxiety participants were (adaptively) less likely to drink after socially embarrassing events, and found no difference in drinking behaviors of socially anxious individuals regardless of whether they had an embarrassing social experience or not (O’Grady et al., 2011). Another study found that perceiving mistreatment by others and negative interpersonal events were associated with increased binge drinking, but only on days also characterized by greater ego depletion (DeHart et al., 2014). Still others have found that negative interactions are associated with increased problem drinking, but only in individuals with low self-esteem (DeHart et al., 2008; DeHart et al., 2009). In summary, prior daily diary studies have shown that rejection experiences across multiple social interactions are also associated with increased daily drinking, but only under certain circumstances. Note, however, these daily diary studies did not distinguish between rejection experiences within close relationships versus those occurring with strangers or acquaintances.

Studies of close relationships suggest that attending to the closeness of the relationship may be a critical factor in considering the impact of social rejection on behavior in daily life. While no known studies have compared close others to strangers in examining the impact of social rejection on drinking, there are studies of social factors and daily drinking solely within the context of a particular close relationship. Several daily diary studies of close relationships and drinking indicate that negative social interactions with a close other is predictive of drinking. For example, one study of emerging adult couples found that increased relationship conflict was associated with increased problem drinking behaviors (Lambe et al., 2015). Another study found that spouses with insecure anxious attachment styles used drinking as a way to cope with problems in their marriage (Levitt and Leonard, 2015). Such findings suggest that negative social interactions within close relationships may have a stronger, or more straightforward, association with alcohol use as compared with negative interactions with acquaintances or strangers. While these studies report significant findings within romantic relationships, they did not measure effects of negative interpersonal experiences outside the relationship on drinking behavior. No known studies have directly compared whether the impact of negative or rejecting interpersonal interactions on daily drinking differs depending on a participant’s degree of closeness with the social interactant.

In the present work, we test the effect of an intuitive but understudied moderator of social rejection’s impact on drinking behavior: relationship closeness. Consistent with lay understanding and with theories of relationship closeness (Berscheid, 1994), we posit that the degree to which a social interaction will affect a participant’s alcohol use will be determined in part by one’s level of relationship closeness with that interactant. This study will examine the association of social rejection with subsequent drinking using the naturalistic paradigm of event-contingent assessment within daily dairy smartphone methodology. Consistent with both the general theory that individuals may drink to relieve any type of stress (Conger, 1956) and the relationship-specific theory that individuals may drink to decrease social wounds and increase a sense of social well-being (Fairbairn and Sayette, 2014), we hypothesize that 1) when social interactions are more rejecting than is usual for a participant, there will be an associated increase in daily alcohol consumption; and 2) the link between social rejection and subsequent drinking will be stronger when rejection is by a close other, versus an acquaintance.

Materials and Methods

Procedure

Data are drawn from a daily diary study of regular drinkers, which was approved by the human subjects research committee. Participants were 78 community members who reported consuming alcohol at least once per week and were recruited via flyers distributed at community locations, on list servs and tables at community events, by word of mouth, and by ads on Craig’s list. Participants completed a phone screen in which they were asked about substance use and their mental health history. Participants were excluded if they did not drink at least once per week in the last month, if they were substance dependent for any substance other than nicotine, or if they had a severe mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other psychotic disorder) requiring acute care. Eligible participants provided written informed consent prior to the intake session. At the intake session participants completed a variety of baseline questionnaires related to mental health, family history, personality characteristics, and demographics. Participants also completed a one hour training session on how to use and complete the items on the smartphone assessments for social interactions. Participants were trained to report daily drinks using the standard definition for “one drink” as either one 5 oz glass of wine, one 12 oz can or bottle of beer, or a 1.5 oz serving of hard alcohol as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2005).

Approximately half (53%) of participants identified as female, and mean participant age was 24.5 years old (SD =5.7). A majority (71.4%) were White/Caucasian, 9.1% were Black/African American, 7.8% were Asian, 7.8% identified as of Hispanic ethnicity, and 3.9% identified as “other” than any of the above groups. Table 1 presents demographic information and descriptive statistics. Participants had an average of about 5 alcohol use days during the study (M = 5.2, SD = 3, Range 1–13), and consumed about 3 drinks on an average alcohol use day (M = 2.9, SD = 2.4, Range 1–24). One participant dropped out of the study prior to data collection. Two additional participants dropped out of the study after 4 and 10 days of diary data collection. As the multilevel statistical modeling technique allows for unbalanced repeated measures (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), the data provided by participants who had any data from the 14 day daily diary period were included, leaving a final sample size of N = 77 participants.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, N = 77

| Variables | Mean (SD) and Percentages (frequency) |

|---|---|

| Age | 24.5 (5.7), Range 18.4 – 44.3 |

| Female | 53.2% (41) |

| Race/ Ethnicity | |

| White/Caucasian | 71.4% (55) |

| Hispanic | 7.8% (6) |

| Asian | 7.8% (6) |

| Black/African-American | 9.1% (7) |

| Other | 3.9% (3) |

| Alcohol Use Days | 5.2 (3.0), Range 1 – 13 |

| Drinks Per Alcohol Use Day | 2.9 (2.4), Range 1 – 24 |

| Hazardous Drinker (AUDIT ≥ 8) | 55.8% (43) |

Social interaction procedure

Participants used smartphones to complete 14 consecutive days of reporting their interpersonal interactions, following social interaction paradigms used in prior studies of interpersonal functioning in daily life (Reis and Wheeler, 1991; Moskowitz and Zuroff, 2005). Guidelines required that interactions be 1) face to face or voice to voice, 2) at least 5 minutes long, and 3) involve a specific identified interactant as opposed to a diffuse group conversation. Participants could initiate event-contingent social interaction surveys at any time, could rate as many per day as they wished, and were asked to rate a minimum of 4 interactions per day. Participants provided information about the person they interacted with (i.e., the “social interactant”) including the type of relationship and degree of closeness with the interactant. They also provided ratings of their affect and stress following each interaction. Responses were uploaded to a secure server in real time and were also saved on participants’ smartphone devices. Research assistants monitored compliance daily and subjects were contacted if irregularities were identified or surveys were not completed. At the end of participation, data saved on the phones was then uploaded and verified against data sent in real time to the server to ensure the completeness of response datasets. Participants were paid for their participation and received a bonus payment of $50 for 95% compliance with survey responses. Compliance for the social interaction surveys was good overall: on average participants completed 4.4 social interaction surveys per day across all study days (with participants’ average interaction reports ranging from 3 to 7 interactions per day), with 81.5% of study days including 4 or more social interactions. As described below, data from most, but not all, social interactions were used for the present paper, informing a day-level summary variable of social rejection experiences.

Measures

Rejection

Rejection was measured by a single item on a visual analog sliding scale with a low anchor of “Not at all” and a high anchor of “Extremely,” which read “Right now, I feel rejected by others.” Responses spanned the possible range of 0 – 100, M = 20.3 SD = 15.8. Note that single item measures were used for both rejection and closeness. While multiple items are preferable to a single item to measure a construct of interest, in order to reduce participant burden in daily diary studies it is an accepted practice to measure constructs related to social situations with only a single item (e.g., Dehart et al., 2009; Laurenceau, Barrett, & Rovine, 2005). As the original variable was skewed, a square root transformation was performed to symmetrize the data prior to analyses. The root-transformed rejection variable spanned the possible range of 0 – 10, M = 4.1 SD = 1.9. Rejection ratings were averaged to create a day-level measure of social rejection experienced by each participant each study day.

Closeness

The degree to which study participants knew their social interactant was captured by a single variable which read “How well do you know this person?” with anchors from “Not at all” to “Very well.” Responses spanned the possible range of 0–100, M = 66.9, SD = 19.7. The variable was divided by 10 for ease of coefficient interpretation, such that a one unit change in the rescaled closeness variable reflects a 10 unit change in the original scaling metric (M = 6.7, SD = 2.0). Closeness ratings were averaged per day to characterize social interaction characteristics per participant per day to relate to subsequent drinking.

Drinks

Participants provided reports of their daily drinking by a simple count of the number of drinks they had that day. If participants had multiple drinking “events” in a day, they complete multiple drinks questionnaires. Alcohol use reports from waking to 5am were included in the prior days’ drinks count. If participants did not report any drinking that day, they were listed as having 0 drinks that day. Daily drinks ranged from 0–24 (see Table 1).

Analytic Plan

Sequence of social rejection and daily drinking

Reports of social interactions and daily drinking were automatically time-stamped in the participants’ smartphone data entry. Participants rated how long ago the social interaction or drinking event occurred, and this value was subtracted from the timestamp associated with their actual data entry. To minimize retrospective bias, social interaction data were excluded if reported more than 2 hours after the event took place. In addition, as the primary hypothesis implied a temporal sequence in which prior social rejection experiences potentiated subsequent daily drinking, social interaction data after the first drink on drinking days were excluded from the present analyses. Note that participants tended to report their social interactions prior to the first drink: (M = 3.49, SD = 1.11), with far fewer interactions reported after the first drink excluded from analyses (M=.91, SD = .93). The mean number of social interactions on non-drinking days was 4.39 (SD= .88). Thus, for each drinking day of the study, participants’ aggregate social interaction ratings prior to the first reported drink were used as predictors of subsequent drinking on the same day in order to test the hypothesized temporal sequence of events.

Multilevel models

Because drinks are a count outcome, linear multilevel modeling could not be used for these analyses (Atkins and Gallop, 2007). We conducted multilevel models appropriate to count outcomes using Stata (StataCorp, 2013). We first tested a model using a Poisson distribution. The Poisson distribution assumes that the mean and variance of the count outcome are equal, an assumption that is often violated in count data. We compared the fit of the more complex negative binomial regression model with the model using the more constrained Poisson distribution. Results showed that the negative binomial model with random effects provided a significantly better fit to the data than the Poisson model with random effects, χ2(1) = 695.79, p <.001. These results provided evidence that a negative binomial model with random effects would provide a more accurate model of daily drinking. The equations for the negative binomial multilevel model were as follows:

Level 1:

Log(E[Drinksij]) = β0j + β1j*cwRejectij + β2j*cwCloseij + β3j*cwRejectij*cwCloseij

-

Level 2:

β0j = γ00 + γ01*cbReject + γ02*cbClose + u0j

β1j = γ10 + u1j

β2j = γ20 + u2j

β3j = γ30

For each social interaction, participants’ ratings of feeling rejected (“cwReject”) and the closeness of their social interactant (“cwClose”) were entered as predictors. These variables were person-mean (group-mean) centered, so that the model would estimate changes in daily drinking as a result of fluctuations around each person’s general levels of rejection and closeness. This type of centering disaggregates within-person fluctuations around one’s own mean from between-person differences in average levels. Thus, within-person and between-person variables are orthogonal (Curran and Bauer, 2011). The mean levels of rejection and closeness were centered around the sample mean (grand mean centered) and entered as individual difference (Level 2) variables to account for between-subjects differences in these variables (“cbReject” and cbClose”). In the full model, the interaction of rejection and closeness was entered as a predictor at level 1 (within-person). Additional covariates and controls (not shown in above equations) were included in both the main effects and interaction models. First, we included variables controlling for time effects to account for unexpected linear trends in the data (Bolger and Laurenceau, 2013). “Study Day” was centered at midpoint of the study and divided by 7 so that a one unit change indicated a one week change in the outcome. Second, we included days of the week found to be significantly more likely to be drinking days. In preliminary analyses, we included indicator variables for each day of the week except Sunday, which served as the reference category. Results showed that participants were significantly more likely to drink on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday than on Sunday (no differences were found for other days of the week). These indicator variables were collapsed into a “Weekend” indicator variable to ensure that the model accounted for increases in drinking due to weekend effects. Finally, centered age, gender, and race/ethnicity minority status variables were included as controls to account for basic demographic characteristics. With these choices, the intercept in the model reflects the likelihood of drinking on a weekday for the average participant’s social interaction with their personal average level of feeling rejected and with a social interactant of average closeness. The key variable for Hypothesis 1 was the main effect of rejection at the within-person level: significance for this variable would indicate that all experiences of rejection that deviated from a person’s average rejection level were associated with subsequent drinking. We hypothesized that experiencing more rejection than usual would lead to more drinking, across all levels of relationship closeness. The key variable for hypothesis 2 was the within-person interaction term between rejection and closeness (“cwReject*cwClose”): a significant coefficient for this interaction term would indicate that the effect of rejection on subsequent drinking depended on how close the participant was with the social interactant. We hypothesized that participants who experienced a more rejecting social interaction than usual from a close other would have an increased likelihood of drinking as compared with social interactions rated equally rejecting by acquaintances.

Results

We first conducted a main effects model to test whether experiences of social rejection predicted subsequent daily drinking irrespective of interactant closeness. This was a within-person hypothesis, testing whether experiences of social rejection above one’s usual rejection levels were associated with increases in drinking (Hypothesis 1). Counter to our hypothesis, results from the main effects model showed no significant association between within-person rejection and drinking. There was a trend-level negative effect of the Study Day variable (γ = −.175, p = .087, RR = .839). This finding may suggest a linear change in drinking reports over the course of the study due to changes either in drinking or reporting patterns (Bolger and Laurenceau, 2013). Given that the effect was only marginally significant, however, we conclude that there was limited evidence that participants’ reporting or drinking patterns changed as a result of study participation. There was also no significant association between age or gender and likelihood of drinking. There was a significant effect of minority status on likelihood of drinking such that participants identifying as White/Caucasian had 1.72 times the likelihood of increased drinking compared to non-Caucasian participants (γ = .541, p = .009, RR = 1.72). As expected based on preliminary analyses, participants were significantly more likely to drink on a weekend (Thursday, Friday, or Saturday) than on other days of the week (γ = .958, p < .001, RR =2.61). Participants’ average (between-subjects) social rejection and average interactant closeness were not significantly associated with likelihood of drinking. Aside from the intercept, there were no other significant effects in this model. See Table 2, Main Effects Model, for all coefficients and associated incidence rate ratios from this model.

Table 2.

Social rejection as a predictor of subsequent daily drinking, main effects and model moderating rejection with social interactant closeness.

| Main Effects Model | Interaction Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate Ratio | Estimate | SE | p | Rate Ratio | Estimate | SE | p | |

|

| ||||||||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | .317 | −1.150 | .221 | <.001 | .315 | −1.154 | .223 | <.001 |

| Within-person variables | ||||||||

| Rejectiona | 1.003 | .003 | .062 | .961 | .984 | −.016 | .063 | .797 |

| Closeness of interactanta | .993 | −.007 | .040 | .865 | 1.007 | .007 | .040 | .856 |

| Rejection*Closenessa | -- | -- | -- | 1.078 | .075 | .032 | .019 | |

| Day of Study | .839 | −.175 | .103 | .087 | .844 | −.169 | .103 | .099 |

| Weekend | 2.607 | .958 | .121 | <.001 | 2.614 | .961 | .120 | <.001 |

| Between-person variables | ||||||||

| Rejectionb | 1.017 | .017 | .059 | .772 | 1.026 | .026 | .059 | .667 |

| Closeness of interactantb | .925 | −.078 | .081 | .333 | .925 | −.078 | .081 | .339 |

| Male | 1.264 | .189 | .186 | .312 | 1.257 | .229 | .184 | .213 |

| White/Caucasian | 1.717 | .541 | .207 | .009 | 1.687 | .523 | .209 | .012 |

| Ageb | 1.012 | .012 | .017 | .461 | 1.012 | .012 | .017 | .473 |

Note: Study Day variable was centered at the study midpoint and divided by 7 so a 1 unit change reflects the passage of 1 week.

Within-person rejection and closeness were person-mean (group mean) centered, so that within-person coefficients represent deviations from one’s own mean levels of rejection and closeness.

All continuous between-person variables were sample-mean (grand mean) centered.

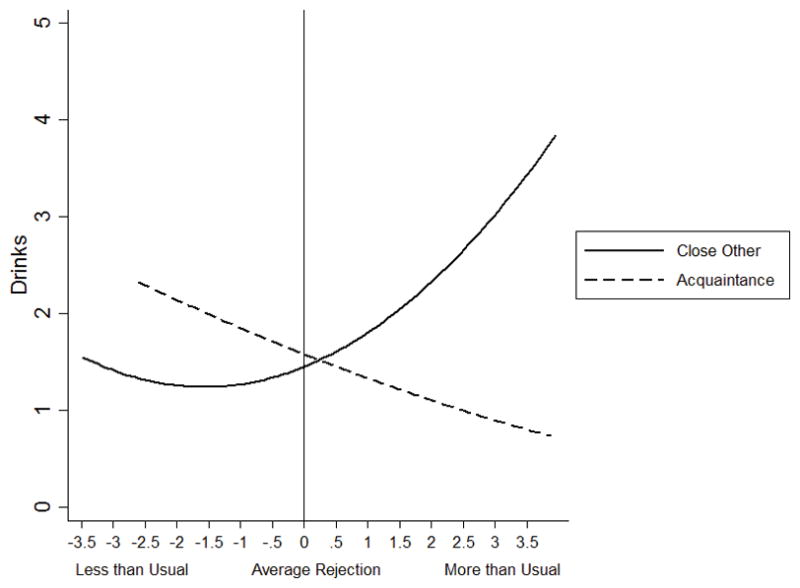

Next, the interaction of within-person social rejection and closeness of interactant were added to the above model. Results showed a significant interaction between rejection and closeness (γ = .075, p = .019, RR = 1.08). As displayed in Figure 1, on days characterized by more rejection than usual by close others there was an associated increase in drinking likelihood, whereas there was no increased likelihood in drinking on days characterized by rejection by acquaintances or strangers. This result is consistent with Hypothesis 2. Note that on days characterized by less rejection than usual, participants showed increases in drinking likelihood regardless of relationship closeness, which is discussed below. All other effects in the model were similar to those reported above, see the Interaction Model results in Table 2 for statistics and rate ratios.

Figure 1.

Social rejection predicts increased drinking when rejected by close others (spouses, family members, close friends) but not when rejected by less familiar individuals (strangers, acquaintances). Note that on days with less than usual social rejection (left side of the figure), drinking increased as rejection decreased, indicating a potentially hedonistic process whereby positive social interactions led to greater daily drinking. There was no significant difference between experiencing less rejection than usual by close others versus strangers (left side of the figure). On days where participants experienced greater than usual social rejection, however (right side of the figure), increased rejection by close others was associated with increased drinking whereas increased rejection by strangers had no significant association with daily drinking. Note: “Close Other” and “Acquaintance” prediction lines are the upper and lower quartile of the continuous interactant closeness rating scale, respectively.

Discussion

Results from this study show that experiencing more social rejection by close others than usual was associated with increased daily drinking. Days characterized by social rejection by acquaintances or strangers were not associated with increased drinking. Interestingly, this study also found increased drinking behaviors for days characterized by less rejection than usual, though this phenomenon did not differ depending on relationship closeness. Taken together, findings suggest that rejection by close others may be one type of dysregulatory experience that increases risk for drinking, consistent with theories of stress-induced substance use (Conger, 1956; Sayette, 1993), and in turn the impact of chronic stress on the likelihood of substance addiction (Sinha, 2008). Findings also showed that experiencing less rejection than usual may be associated with increased drinking, in line with current understanding of socially motivated drinking and drinking to enhance or regulate positive experiences (Cooper et al., 1995; Weiss et al., 2015; Wilkie and Stewart, 2005).

The primary finding of this study is that not all types of social rejection are associated with increased drinking. While one prior study of social rejection in a laboratory setting found that social rejection experiences impacted likelihood of drinking (Rabinovitz, 2014), the manipulation used evoked rejection related to close, lasting relationships, not rejection by strangers. In the present work we found that in the more naturalistic paradigm of event- contingent reporting in daily life, not all rejection experiences affected alcohol use. Only rejection experiences delivered by close others were associated with increased drinking. This finding is in line with prior work across multiple domains of relationship influence that suggest that behavior and affect are more strongly affected by closer relationships as opposed to stranger relationships (e.g., Joiner and Katz, 1999). The negative effects of this social rejection in turn may increase stress, and drinking may be used as a means of coping with increased feelings of stress. Another possibility is that experiences of social rejection are associated with drinking not as a way of coping with stress, but as a means of repairing one’s sense of social functioning. Rejection researchers have identified social rejection as a threat to the social self and social ties. Prior research and theory have suggested that one function of social drinking is that it lessens the fear of social rejection, and induces a sense of social connection (Fairbairn and Sayette, 2014). Since the majority (89%) of drinking reported in the present study involved drinking with others as opposed to drinking in isolation, it is reasonable to suggest a process in which the wounds of social rejection are soothed by social drinking. The theorized process in this case is that social rejection by close others hurts in multiple ways, not only by increasing stress, but by decreasing self-esteem, social efficacy, and increasing fears of future rejection. Alcohol researchers have found that social drinking serves as a means of creating the illusion of social bonds by decreasing fears of rejection (Fairbairn and Sayette, 2014). Given that only a small percentage of drinking took place outside the social drinking context, it was not possible to disaggregate whether the increased drinking found in the present study served the function of stress relief or, alternately, whether it served the function of repairing threats to the social self.

A methodological strength of the present work is that data were gathered in the hypothesized temporal sequence in which daily experiences of social rejection are associated with subsequent drinking. In daily diary studies with only one report of drinking and rejection per day, for example, it would be difficult to test whether rejection led to drinking or instead whether drinking led to feeling rejected. In the present work, however, multiple measures of social interactions were collected each day, and only social interactions that occurred prior to the first drink of the day were included. Thus, while this study cannot claim a causal association between social rejection and drinking due to its observational design, findings from this study do provide evidence for a temporal sequence in which increases in perceived social rejection are associated with increased drinking subsequent to those experiences.

It is also important to highlight that the present findings are within-person findings. What this means conceptually is that each individual served as his or her own reference point: on days when individuals felt more rejected than usual by their close others, they drank more than their usual amount. Differences in average rejection levels between participants were removed from the within-person variable. By disaggregating within-person fluctuations around an individual’s average, we are able to eliminate the potential confound that individual-level characteristics were responsible for the process observed. For example, there are individuals who experience, or perceive themselves as experiencing, more rejection in general than other individuals. By removing mean levels of perceived rejection, we were able to disaggregate how fluctuations around one’s average perceived rejection level affected drinking. We found that, regardless of participants’ average social rejection levels, instances of social rejection by close others above that average were associated with increased risk for drinking behaviors.

While experiencing less rejection than usual was not the emphasis of the present inquiry, the increase in drinks associated with experiencing less rejection than usual is nonetheless consistent with prior studies. Several studies have shown that positive, not only negative, daily experiences are associated with increased drinking (Carney et al., 2000; Mohr et al., 2001; Park et al., 2004). This line of research shows evidence for hedonic drinking, such that when individuals are less stressed or happier than usual, they may engage in other pleasure-seeking activities such as alcohol use (Arbeau et al., 2011). These results are also consistent with recent studies of positive urgency, which find that some individuals may use drinking as a way to regulate both negative and positive affect (Weiss et al., 2015).

Lower than usual rejection may simply represent the absence of rejection or, alternatively, may represent the presence of acceptance. Unfortunately, in the present study, feelings of acceptance were not measured following participants’ social interactions, so we were unable to test the meaning of the intriguing finding that experiencing less rejection than usual was also associated with increased drinking. In addition, note that the effect of less rejecting experiences than usual did not differ depending on the closeness of the interactant, suggesting that the role of relationship closeness may be more important in negatively, versus positively, valenced interactions. This idea is consistent with prior research finding differential effects for positive versus negative emotions (Baumeister et al., 2001). Future studies of daily experiences of social interaction should assess the impact of interactant closeness on both negative and positive social interactions in order to further explore the meaning of this finding.

This study had several limitations. First, we relied on participants’ self-reports of both drinking and social rejection, thus findings from this study may be influenced by biases in reporting of these behaviors. Relatedly, all surveys used in the present work were event-contingent, meaning that participants had to initiate their smartphone survey in order to report on their drinking behaviors or social interactions. For example, it is possible that days with no reported drinking were in fact days in which participants were simply non-compliant with reporting their drinking. A second limitation is that our relatively smaller sample size limited our power to detect differences in key subgroup’s responses to social rejection. Prior research suggests that individuals with early experiences of rejection or trauma may have rejection sensitivity (Downey and Feldman, 1996). Rejection sensitive individuals may be more likely to perceive rejection than others, and may be more affected by social rejection experiences than those who are not rejection sensitive. For these individuals, we would expect to see increased drinking after rejection experiences. Other studies have shown that rejection from close others affects women more than men (Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Lambe et al., 2015), suggesting that gender should have been included as a moderator in the present work. The present study’s relatively small sample size, however, did not allow for adequately powered tests of whether the within-person process here differed for meaningful subgroups of participant. Future studies will need to examine whether such “cross-level” interactions of between-subjects characteristics are associated with stronger within-person reactions to social rejection.

Finally, our study only tested the association between social rejection and drinking in one direction, while the literature also suggests that drinking can lessen perceptions of subsequent social rejection. Since a majority (over 75%) of social interactions were reported prior to the first drink on drinking days, we did not have enough social interaction data in the present study to test the hypothesis the drinking led to reduced perceptions of rejection. The literature will benefit from future studies which enable modeling of the rejection-drinking linkage in both directions.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that social rejection by close others, but not strangers or acquaintances, leads to increased daily drinking. While further work is need to replicate and extend these findings to other populations, the repeated measures collected each day of the present study did enable us to test whether prior social rejection experiences on a given day lead to subsequent drinking later that day. One implication of these findings is that it clarifies how processes within close relationships are important when considering proximal risk factors for hazardous drinking. While there is ample evidence that couples and family therapies can aid in alcohol recovery (Stanton and Shadish, 1997), there is a relatively smaller body of research examining the social processes that may contribute to increased hazardous drinking in individuals who are at risk for alcohol use disorders. This study’s findings suggest that understanding the social context of at-risk drinking may help develop interventions aimed at decreasing subsequent drinking. Close relationships, and feelings or rejection from close others, may be the sites for interventions aimed at preventing alcohol use disorders.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K08DA029641 (EBA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Arbeau KJ, Kuiken D, Wild TC. Drinking to enhance and to cope: A daily process study of motive specificity. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: a tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:726. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon AK, Cranford AN, Blumenthal H. Effects of ostracism and sex on alcohol consumption in a clinical laboratory setting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29:664. doi: 10.1037/adb0000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddam S, Laws H, Crawford JL, Wu J, Bolling DZ, Mayes LC, Crowley MJ. What they bring: baseline psychological distress differentially predicts neural response in social exclusion by children’s friends and strangers in best friend dyads. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsw083. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5:323. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E. Interpersonal relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 1994;45:79–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Laurenceau J. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research (Methodology in the social sciences) The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carney MA, Armeli S, Tennen H, Affleck G, O’Neil TP. Positive and negative daily events, perceived stress, and alcohol use: a diary study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Hong K, Bergquist K, Sinha R. Gender differences in response to emotional stress: An assessment across subjective, behavioral, and physiological domains and relations to alcohol craving. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charuvastra A, Cloitre M. Social bonds and posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:301. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1956 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart T, Longua Peterson J, Richeson JA, Hamilton HR. A diary study of daily perceived mistreatment and alcohol consumption in college students. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2014;36:443–451. [Google Scholar]

- DeHart T, Tennen H, Armeli S, Todd M, Affleck G. Drinking to regulate negative romantic relationship interactions: The moderating role of self-esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:527–538. [Google Scholar]

- DeHart T, Tennen H, Armeli S, Todd M, Mohr C. A diary study of implicit self-esteem, interpersonal interactions and alcohol consumption in college students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:720–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn CE, Sayette MA. A social-attributional analysis of alcohol response. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1361. doi: 10.1037/a0037563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber J, Wheeler L. On being rejected a meta-analysis of experimental research on rejection. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4:468–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Katz J. Contagion of depressive symptoms and mood: meta-analytic review and explanations from cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal viewpoints. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lambe L, Mackinnon SP, Stewart SH. Dyadic conflict, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems: A psychometric study and longitudinal actor–partner interdependence model. Journal of Family Psychology. 2015;29:697. doi: 10.1037/fam0000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Rovine MJ. The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: A daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:314–323. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Twenge JM, Quinlivan E. Interpersonal rejection as a determinant of anger and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:111–132. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Cooper ML. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:1706–1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Leonard KE. Insexure attachment styles, relationship-drinking contexts, and marital alcohol problems: Testing the mediating role of relationship-specific drinking-to-cope motives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29:696–705. doi: 10.1037/adb0000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Carney MA, Afflect G, Hromi A. Daily interpersonal experiences, context, and alcohol consumption: crying in your beer and toasting good times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:489. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz D, Zuroff DC. Robust predictors of flux, pulse, and spin. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39:130–147. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much, a clinician’s guide. National Institute of Health Publication 09-3769; 2005. [on December 23, 2016]. Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady MA, Cullum J, Armeli S, Tennen H. Putting the relationship between social anxiety and alcohol use into context: A daily diary investigation of drinking in response to embarrassing events. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2011;30:599. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2011.30.6.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitz S. Drowning your sorrows? Social exclusion and anger effects on alcohol drinking. Addiction Research & Theory. 2014;22:363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods (Second Edition) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Wheeler L. Studying social interaction with the Rochester Interaction Record. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1991;24:269–318. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Canyas R, Downey G, Reddy KS, Rodriguez S, Cavanaugh TJ, Pelayo R. Paying to belong: when does rejection trigger ingratiation? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99:802. doi: 10.1037/a0020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA. An appraisal-disruption model of alcohol’s effects on stress responses in social drinkers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:459. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1141:105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreekrishnan A, Herrera TA, Wu J, Borelli JL, White LO, Rutheford HJ, Mayes LC, Crowley MJ. Kin rejection: social signals, neural response and perceived distress during social exclusion. Developmental Science. 2014;17:1029–1041. doi: 10.1111/desc.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MD, Shadish WR. Outcome, attrition, and family–couples treatment for drug abuse: A meta-analysis and review of the controlled, comparative studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:170. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Sullivan TP, Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and risky behaviors among trauma-exposed inpatients with substance dependence: The influence of negative and positive urgency. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;155:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie H, Stewart SH. Reinforcing mood effects of alcohol in coping and enhancement motivated drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:829–836. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000163498.21044.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism: The Power of Silence. New York: Guilford; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Cheung CK, Choi W. Cyberostracism: effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:748. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Jarvis B. Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior Research Methods. 2006;38:174–180. doi: 10.3758/bf03192765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]