Abstract

Antibiotic resistance continues to receive national attention as a leading public health threat. In 2015, President Barack Obama proposed a National Action Plan to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to curb the rise of “superbugs,” bacteria resistant to antibiotics of last resort. Whereas many antibiotics are prescribed appropriately to treat infections, there continue to be a large number of inappropriately prescribed antibiotics. Although much of the national attention with regards to stewardship has focused on primary care providers, there is a significant opportunity for surgeons to embrace this national imperative and improve our practices. Local quality improvement efforts suggest that antibiotic misuse for surgical disease is common. Opportunities exist as part of day-to-day surgical care as well as through surgeons' interactions with nonsurgeon colleagues and policy experts. This article discusses the scope of the antibiotic misuse in surgery for surgical patients, and provides immediate practice improvements and also advocacy efforts surgeons can take to address the threat. We believe that surgical antibiotic prescribing patterns frequently do not adhere to evidence-based practices; surgeons are in a position to mitigate their ill effects; and antibiotic stewardship should be a part of every surgeons' practice.

Keywords: antibiotic stewardship, antibiotics, healthcare acquired infections, surgery, surgical site infections, urinary tract infections

Antibiotic resistance continues to receive national attention as a leading public health threat. In 2015, President Barack Obama proposed a National Action Plan to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to curb the rise of “superbugs,” bacteria resistant to antibiotics of last resort. One of its goals is to reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics by 50% in the outpatient setting and 20% in the inpatient setting.1 Hundreds of millions of antibiotic prescriptions are written annually in the United States, and antimicrobials routinely make up more than 20% of hospital pharmacy budgets.2 In 2011 alone, 842 antibiotic prescriptions were written per 1000 people.3 Whereas many antibiotics are prescribed appropriately to treat infections, there continue to be a large number of inappropriate prescriptions, estimated to be 50% in some studies. It is these unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions that promote antibiotic resistance. They threaten the future availability of effective therapeutics as old antimicrobial agents no longer work and new agents are coming to the market slowly.2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates there are 2 million illnesses and 23,000 deaths per year due to antibiotic-resistant organisms, with the incidence continuing to rise annually.2 We believe that surgical antibiotic prescribing patterns frequently do not adhere to evidence-based practices; surgeons can actively engage in improving prescribing patterns; and antibiotic stewardship should be a part of every surgeon's practice.

Surgeons' Call to Action

Antibiotics are an important component of the treatment for many surgical diseases. To preserve the efficacy of antibiotics and curb the development of multidrug-resistant bacteria, surgeons and patients must be responsible stewards of this limited and precious resource. Some of the most common surgical conditions, such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis, are infectious in nature. Additionally, healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), such as surgical site infections, urinary tract infections, and pneumonia, are among the most common complications we face. Too often, we overtreat surgical infections or HAIs by prescribing antibiotics for longer than needed or using broad-spectrum agents when a narrower-spectrum agent would suffice.4 Furthermore, HAIs are frequently treated presumptively, when the patient may not meet the criteria for a urinary tract infection or Clostridium difficile infection, and as a result receives an unnecessary course of antibiotics.5,6

Opportunities for Antibiotic Stewardship in Surgery

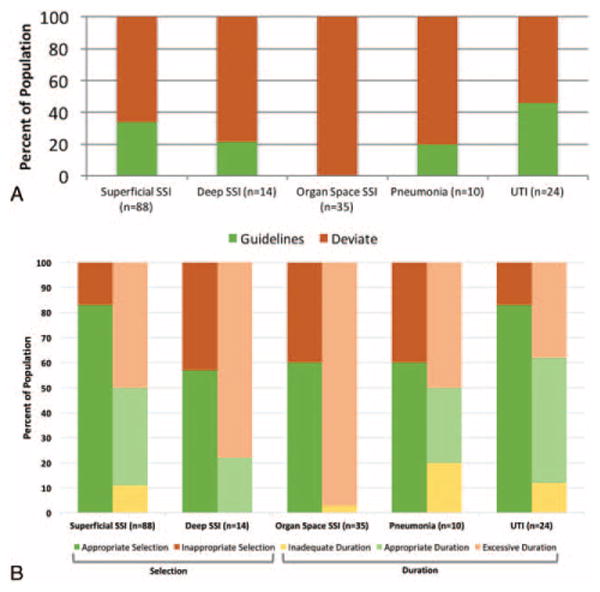

Although much of the national attention with regards to stewardship has focused on primary care providers—pediatricians and family practice providers—there are opportunities for surgeons to embrace this national imperative and improve our practices. We evaluated the antibiotic-prescribing practices of surgeons at The Johns Hopkins Hospital for patients with postoperative HAIs (surgical site infections, urinary tract infections, and pneumonia). Patients who developed HAIs within 30 days of colorectal surgery were identified from the hospital's American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Through further review of patients' records, we identified the date of HAI diagnosis, antibiotic selection, and duration of treatment. These treatment regimens were then compared with the Johns Hopkins Antibiotic Guidelines—a handbook updated annually by the hospital's Antibiotic Stewardship Group.7 We identified significant opportunities for improvement with many cases demonstrating over and inappropriate treatment (Fig. 1). In 73% of HAIs, the clinicians' treatment deviated (eg, antibiotic selection, duration) from recommended practice. Twenty-five per cent of patients were treated with too broad a regimen, and 60% of patients were treated beyond the recommended duration. These data suggest that surgical practice even at medical centers with antibiotic stewardship programs fails more often than not to prevent antibiotic misuse. We believe this is a common phenomenon.1,3

FIGURE 1.

Panel A: Proportion adhering to Johns Hopkins Antibiotic Guidelines selection and duration recommendations for colorectal surgery patients at The Johns Hopkins Hospital grouped by HAI (n = 222 patients). Panel B: Proportion of nonadhering prescribing practices by specific guideline deviation. SSI indicates surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Areas to Incorporate Antibiotic Stewardship into Surgical Practice

Surgeons need to stay up to date with national consensus guidelines regarding appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for procedures they regularly perform and antibiotic treatment of the complications they most commonly encounter. Clinical decision-making regarding antibiotic use, including empiric antibiotic selection; daily re-evaluation of the need for continued antibiotic therapy; and optimizing the duration of therapy, should be basic expectations of surgical practice in the antibiotic-resistance era. Most importantly, surgeons should be encouraged to seek consultation from their antimicrobial stewardship team or infectious diseases consultant when questions arise.

Newer evidence supports more restrictive antibiotic prescribing, but we frequently fail to translate antibiotic treatment-related research into surgical practice. The following recommendations can help surgeons incorporate best-evidence practices:

Prophylactic antibiotics should be discontinued at the end of the procedure for routine general surgery cases. Prolonged use—even for only 24 hours—does not help prevent surgical site infec-tions.8–10

Topical antibiotics are not indicated in the era of prophylactic systemic antibiotic therapy. A meta-analysis comparing appendectomy and colorectal surgery patients with and without systemic antibiotic prophylaxis demonstrated the surgical site infection benefit of topical antibiotic disappeared when using routine, prophylactic systemic antibiotics.8

Limited, fixed courses of antibiotics are sufficient for treating complex intra-abdominal infections after the infectious source is controlled. A recent randomized trial demonstrated similar outcomes when comparing the effectiveness of approximately 4 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics for intra-abdominal infections versus physiologic triggered regimens that on average lasted 8 days.9

Incision and drainage of superficial skin abscesses and opening of infected superficial surgical site infections is an effective treatment. Antibiotic treatment is not necessary after appropriate drainage.10–12

Uncomplicated diverticulitis does not typically need to be treated with antibiotics. Recent studies support the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents without antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis.13,14 Continuing to provide unnecessary or excessive antibiotics has been demonstrated to double the rates of C difficile infection in surgical patients.15

Asymptomatic bacteriuria should be distinguished from urinary tract infections, and the former should not be treated with antibiotics except for pregnant women and men undergoing transurethral prostate resections. Urinalyses and urine cultures are routinely sent as part of postoperative fever evaluations, but our data above suggest the results are not being interpreted correctly. Bacteriuria in patients without frequency, urgency, dysuria, or unspecified suprapubic pain does not constitute a urinary tract infection and should not be treated.6,7,16

Clostridium difficile samples should only be sent when the pathologic condition is suggested by the patients' clinical state including at least 3 or more unformed stools in 24 hours.17 A positive laboratory test without evidence of symptoms suggests asymptomatic colonization and should not be treated.5,7

Institutional and External Advocacy for Antibiotic Stewardship in Surgery

Although, there is a clear role for antibiotic stewardship in surgical care, there is little attention devoted nationally to the subject. For example, more than 20 recommendations from various specialty society participants of the American Board of Internal Medicine's cross-disciplinary Choosing Wisely Campaign recognize the importance of overuse and misuse of antibiotics. However, none of the recommendations contributed by the American College of Surgeons address antibiotic use.18 Furthermore, an environmental scan of the past 12 months of the 5 most highly cited general surgery journals found no articles relating to antibiotic stewardship. We are at risk of losing influence over antibiotic decision-making for our patients if we do not increase our engagement in antibiotic stewardship work by providing proactive leadership in this field.

Residency training programs should provide focused efforts to ensure that future generations of surgeons optimize antibiotic use. In the same way that we value and enable ongoing professional development with respect to surgical technique and operating knowledge, surgeons should be expected to continually hone their knowledge about antibiotic prescribing for their surgical practice. Efficient forms of implementing ongoing antibiotic stewardship education at the national level include subject-specific continuing medical education requirements and formal inclusion of antibiotic stewardship as a topic on specialty board maintenance of certification exams.

At the local level, clinical decision support, performance feedback, and surgical engagement in hospital antibiotic stewardship activities are all strategies to promote ongoing practice improvement. Most hospitals have or are in the process of developing antimicrobial stewardship programs. Starting in January 2017, all hospitals accredited by The Joint Commission will have to meet the new standard with regards to antibiotic stewardship. This includes: establishing antimicrobial stewardship as an organizational priority; educating staff, patients, and families about the appropriate use of antibiotics; and creating a multidisciplinary antimicrobial stewardship team. Importantly, the Joint Commission recognized the importance of requiring diverse expertise for antimicrobial stewardship. Surgeons should support and participate in these hospital efforts and ensure that the best evidence is reconciled with practical experience and procedure-specific risks.

Antibiotics are one of the medical advances in the 20th century that have radically transformed how we are able to care for and treat surgical disease. Unlike some other technical counterparts, however, antibiotics represent a healthcare resource in which their current use limits their future availability. Before the introduction of antibiotics, surgical wound sepsis was effectively a foregone conclusion with infection rates as high as 90% during the first world war.19 Combined top-down and bottom-up approaches such as those proposed here will help maintain this precious surgical resource for the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Timothy Pawlik, MD, for his comments on early versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

ILL and AF contributed equally to this work.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Office of the Press Secretary. Washington, DC: 2015. Fact Sheet: Obama administration releases national action plan to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria [Internet] [Accessed February 6, 2016]. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/12/22/fact-sheet-obama-administration-releases-national-action-plan-combating. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamma PD, Cosgrove SE. Antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2011;25:245–260. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1308–1316. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedouch P, Labarère J, Chirpaz E, et al. Compliance with guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip replacement surgery: results of a retrospective study of 416 patients in a teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:302–307. doi: 10.1086/502396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su W-Y, Mercer J, Van Hal SJ, et al. Clostridium difficile testing: have we got it right? J Clin Microbiol. 2016;51:377–378. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02189-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when to screen and when to treat. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:367–394. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosgrove SE, Avdic E, editors. Antimicrobial Stewardship Program. Antibiotic Guidelines 2015-2016. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Medicine; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charalambous C, Tryfonidis M, Swindell R, et al. When should old therapies be abandoned? A modern look at old studies on topical ampicillin. J Infect. 2003;47:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(03)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawyer RG, Claridge JA, Nathens AB, et al. Trial of short-course antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infection. N Engl J Med. 2016;372:1996–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huizinga WKJ, Kritzinger NA, Bhamjee A. The value of adjuvant systemic antibiotic therapy in localised wound infections among hospital patients: a comparative study. J Infect. 1986;13:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(86)92118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Heal Pharm. 2013;70:195–283. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:e10–e52. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mali JP, Mentula PJ, Leppäniemi AK, et al. Symptomatic treatment for uncomplicated acute diverticulitis: a prospective cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:529–534. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chabok A, Påhlman L, Hjern F, et al. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:532–539. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itani KMF, Wilson SE, Awad SS, et al. Ertapenem versus cefotetan prophylaxis in elective colorectal surgery. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2640–2651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:643–654. doi: 10.1086/427507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA) Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–455. doi: 10.1086/651706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely Recommendations [Internet] 2014 [Accessed February 6, 2016]. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Choosing-Wisely-Recommendations.pdf.

- 19.Fraser F, Dew JW, Taylor DC, et al. Primary and delayed primary suture of gunshot wounds. Br J Surg. 2016;6:92–124. [Google Scholar]