Abstract

The emerging field of RNA nanotechnology has been used to design well-programmed, self-assembled nanostructures for applications in chemistry, biology, and medicine. At the forefront of its utility in cancer is the unrestricted ability to self-assemble multiple siRNAs within a single nanostructure formulation for the RNAi screening of a wide range of oncogenes while potentiating the gene therapy of malignant tumors. In our RNAi nanotechnology approach, V- and Y-shape RNA templates were designed and constructed for the self-assembly of discrete, higher-ordered siRNA nanostructures targeting the oncogenic glucose regulated chaperones. The GRP78-targeting siRNAs self-assembled into genetically encoded spheres, triangles, squares, pentagons and hexagons of discrete sizes and shapes according to TEM imaging. Furthermore, gel electrophoresis, thermal denaturation, and CD spectroscopy validated the prerequisite siRNA hybrids for their RNAi application. In a 24 sample siRNA screen conducted within the AN3CA endometrial cancer cells known to overexpress oncogenic GRP78 activity, the self-assembled siRNAs targeting multiple sites of GRP78 expression demonstrated more potent and long-lasting anticancer activity relative to their linear controls. Extending the scope of our RNAi screening approach, the self-assembled siRNA hybrids (5 nM) targeting of GRP-75, 78, and 94 resulted in significant (50–95%) knockdown of the glucose regulated chaperones, which led to synergistic effects in tumor cell cycle arrest (50–80%) and death (50–60%) within endometrial (AN3CA), cervical (HeLa), and breast (MDA-MB-231) cancer cell lines. Interestingly, a nontumorigenic lung (MRC5) cell line displaying normal glucose regulated chaperone levels was found to tolerate siRNA treatment and demonstrated less toxicity (5–20%) relative to the cancer cells that were found to be addicted to glucose regulated chaperones. These remarkable self-assembled siRNA nanostructures may thus encompass a new class of potent siRNAs that may be useful in screening important oncogene targets while improving siRNA therapeutic efficacy and specificity in cancer.

Keywords: siRNA nanostructures, RNAi nanotechnology, cancer gene therapy, chaperones, glucose regulated proteins, GRP, endometrial, cervical and breast cancer

Graphical Abstract

Gene therapy has re-emerged as a powerful modern day treatment modality in the search for a cure for cancer.1 Several cancer gene therapy methods have already been realized in vitro as well as in vivo, paving the way for their successful use in human clinical oncology.2 Leading the way are the growing applications of short-interfering RNA (siRNA) in cancer therapy.3 Technological advances in synthetic biology have ushered in a new wave of modified siRNAs that have improved the silencing of oncogenic mRNA expression, ultimately resulting in tumor cell death.4 This RNA interference (RNAi) mechanism has shown exceptional catalytic efficacy and tolerance for a wide range of modified siRNAs that can effectively screen a variety of oncogene targets while potentiating gene silencing effects.5

The rise of RNA nanotechnology has led to the evolution of functional RNA materials for a variety of applications, including the development of nanomedicines.6,7 Recently, siRNA nanostructures have been formulated and applied for silencing single or multiple gene targets. For example, hybrid RNA nanocubes composed of six double-stranded dsRNA Dicer substrates have been formulated and shown to simultaneously release multiple siRNAs in breast cancer cells upon Lipofectamine-mediated transfection.8 The intracellular release of the siRNAs was found to trigger the RNAi response and effectively down-regulated the reporter, enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), for up to 12 days. In a related case study, multifunctional RNA nanorings embedding six siRNAs within the nanoparticle formulation were shown to silence eGFP expression at concentrations as low as 1 nM.9 Moreover, the siRNA nanoparticles were functionalized with RNA aptamers, which were selected for binding to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) overexpressed on human breast cancer cells. These RNA nanoparticles demonstrated targeted tumor binding and cellular uptake, which led to persistent eGFP knockdown over a nine day period. This effect was found to be equivalent to the transfection of the linear eGFP-siRNAs at 6-fold higher concentrations. In another proof-of-concept study, the branched siRNA nanostructures targeting multiple mRNA sites of the luciferase firefly reporter gene were shown to self-assemble into three- and four-way junctions.10 These nanoparticle formulations released multiple siRNAs upon Dicer cleavage and effectively silenced luciferase activity for up to 5 days in HeLa cells. Taken altogether, these representative examples demonstrate the ability for higher-ordered siRNA nanostructures to behave as Dicer substrates, resulting in the release of multiple siRNAs that are processed by the RNAi mechanism, ultimately leading to synergistic gene knockdown effects. These results underscores the potential utility of siRNA nanostructures in RNAi screening and cancer gene therapy applications.

We previously reported the synthesis, characterization and RNAi evaluation of branch and hyperbranched siRNAs.11 These novel molecular structures were built by automated solid-phase RNA synthesis and incorporated a ribouridine branchpoint synthon, which facilitated the extension of single or double siRNAs targeting the glucose-regulated protein of 78 kDa (GRP78). GRP78 is a chaperone protein located in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, where it plays a pivotal role in regulating protein misfolding responses.12 Although GRP78 is primarily found within the cytoplasm of healthy cells, in cancer, GRP78 is overexpressed and localized to the cell surface, where it functions as a signaling receptor for oncogenic activity.13 Moreover, GRP78 is associated with other stress-inducible members of the GRP family of chaperones, including GRP-75 and 94, which have also been found to play a pivotal role in the progression of certain types of cancers.19 GRP knockdown or inhibition has been shown to sensitize cancer cells to treatment and trigger tumor cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, resulting in potent anticancer effects.14–20 Thus, GRP78 and the related glucose-regulated chaperones have been validated as clinically relevant molecular targets in cancer.19 In our previous study, the branch and hyperbranch siRNAs led to 50–60% silencing of GRP78 expression, which translated to approximately 20% cell death of the HepG2 liver cancer cells.11 Therefore, the branch and hyperbranch siRNAs have effectively expanded the repertoire of modified siRNA motifs that may be useful in the development of more potent RNAi oncogene therapeutics.

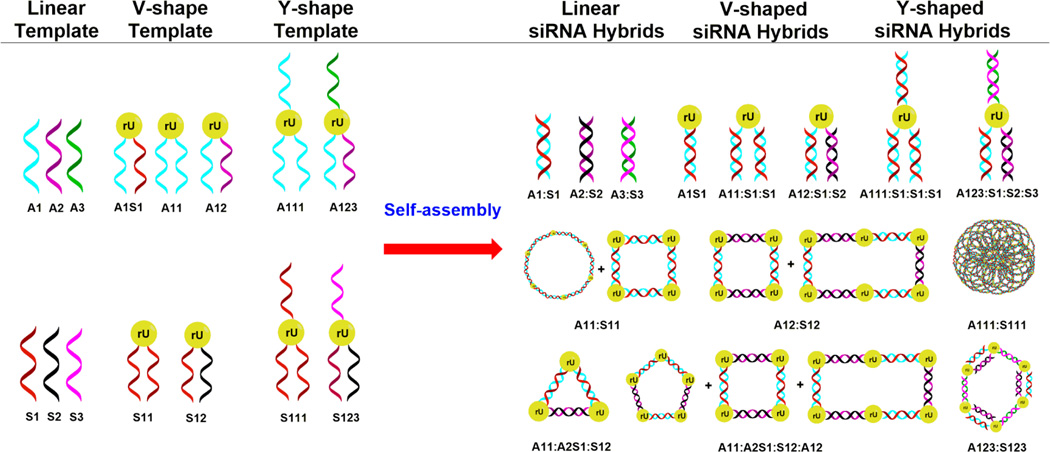

Toward this goal, this study describes the applications of linear and V- and Y-shaped RNA templates for the self-assembly of GRP-targeting siRNA nanostructures owning distinct sizes and shapes (Figure 1). This combinatorial self-assembly approach has enabled the formulation of a library (30) of siRNA nanoparticles for exploring structure–activity relationships (SARs) within GRP overexpressing cancer cell lines.

Figure 1.

Design and self-assembly of siRNA nanostructures. The RNA templates (namely, linear and V-, and Y-shaped RNA) were designed and synthesized according to our previously described methodology.11 The V- and Y-shaped templates incorporate a branchpoint ribouridine (rU), which facilitates the hybridization of complementary sense (S) and antisense (A) RNA. These templates preorganizes the self-assembly of siRNA hybrid nanostructures having discrete sizes and shapes, including those belonging to circles, triangles, squares, rectangles, pentagons, hexagons, and poroustype structures. These siRNA nanostructures are genetically encoded to target a single (1), double (1, 2) and triple (1, 2, 3) sites of oncogenic GRP-75, 78, and 94 mRNA.

siRNA Self-Assembly

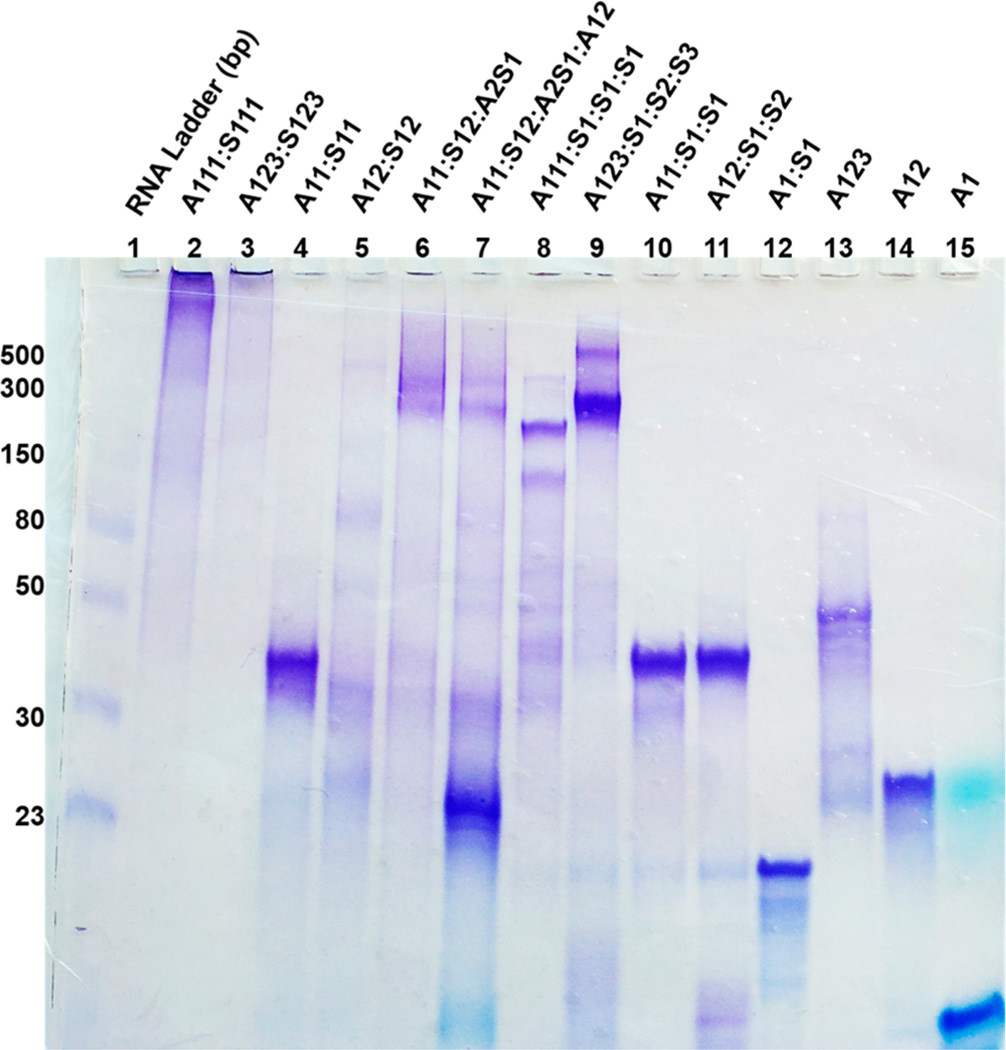

The siRNA sequences described in this study (Table S1) are based on the target nucleotides for down-regulating GRP-75, 78, and 94 expression in human cancer cells.20,21 The linear and V- and Y-shaped RNA templates incorporating the antisense (A) or sense (S) single strands targeting GRP-75, 78, and 94 mRNA were synthesized by automated solid-phase RNA synthesis following our previously reported procedure.11 In our synthetic approach, an orthogonally protected 5′-OLv 2′-OMMT ribouridine phosphoramidite was incorporated as branchpoint synthon to selectively and efficiently extend the linear RNA sequence into the V- and Y-shape RNA templates on solid phase. Following solid-phase synthesis, cleavage and deprotection, the crude RNA templates were purified by reverse-phase ion-pairing high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-IP-HPLC) in ≥96% purities, and their identities were confirmed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI MS); see Table S1. The purified RNA templates and their complementary RNA strands were hybridized in annealing buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA; pH 7.5–8.0, 13–15 µL) using equimolar concentrations (0.75 µM) of the pairing strands. For the higher-ordered siRNA formulations, each complementary strand was added to their corresponding RNA templates in stoichiometric ratios that favored hybrid formation and self-assembly into the putative siRNA nanostructures. In this procedure, the V- and Y-shape RNA templates preorganize the self-assembly with their complementary strands resulting in siRNA nanostructures that were designed to mimic genetically encoded geometric shapes such as circles, triangles, squares, rectangles, pentagons, hexagons, and porous-type structures (Figure 1). Hybridization and self-assembly were promoted by heating the RNA templates and their complementary sequences at 90 °C (5–10 min) followed by slow cooling to room temperature (22 °C) for 1 h and overnight storage at 4 °C. siRNA hybridization was confirmed by a native, nondenaturing 16% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). In this assay (Figure 2), the lower molecular weight templates (linear and V- and Y-shaped RNA) migrated fastest on the gel and were found to be equivalent to the anticipated migration of the 23–50 bp RNA ladder. The V- and Y-shaped RNA templates hybridized to their complementary RNA single strands (Figure 2; lanes 10 and 11 and lanes 8 and 9, respectively) migrated slower on the gels, with electrophoretic mobilities, which were found to be comparable to the migration of the 30–50 bp RNA ladder (V-shape siRNA hybrids, lanes 10 and 11) and the 150–300 bp RNA ladder (Y-shape siRNA hybrids, lanes 8 and 9). The self-assembled V- (Figure 2, lanes 4–7) and Y-shape (Figure 2, lanes 2 and 3) siRNA hybrids migrated the slowest on the gels. The self-assembled V-shape siRNA hybrids (lanes 4 and 5) migrated with similar electrophoretic mobility on gel in comparison to the V-shape siRNA hybrids formed with their complementary linear RNA sequences (lanes 10 and 11). The siRNA hybrid combinations formed with multiple Y- and V-RNA templates (lanes 2 and 3 and lanes 6 and 7, respectively) were found to be ≥300 bp RNA ladders, suggesting the formation of higher-ordered siRNA nanostructures.

Figure 2.

siRNA self-assembly. Native, nondenaturing 16% PAGE of self-assembled Y- (lanes 2 and 3), V-shape (lanes 4–7) siRNA hybrids, Y-shape RNA templates hybridized to linear complementary RNA sequences (lanes 8 and 9), V-shape RNA templates hybridized to linear complementary RNA sequences (lanes 10 and 11), and linear siRNA (lane 12) along with Y-shape (lane 13), V-shape (lane 14), and linear (lane 15) RNA templates. The RNA ladder (23–500 bp) was used to track the relative sizes of the siRNA hybrids on the gel (lane 1).

Characterization of siRNA Nanostructures

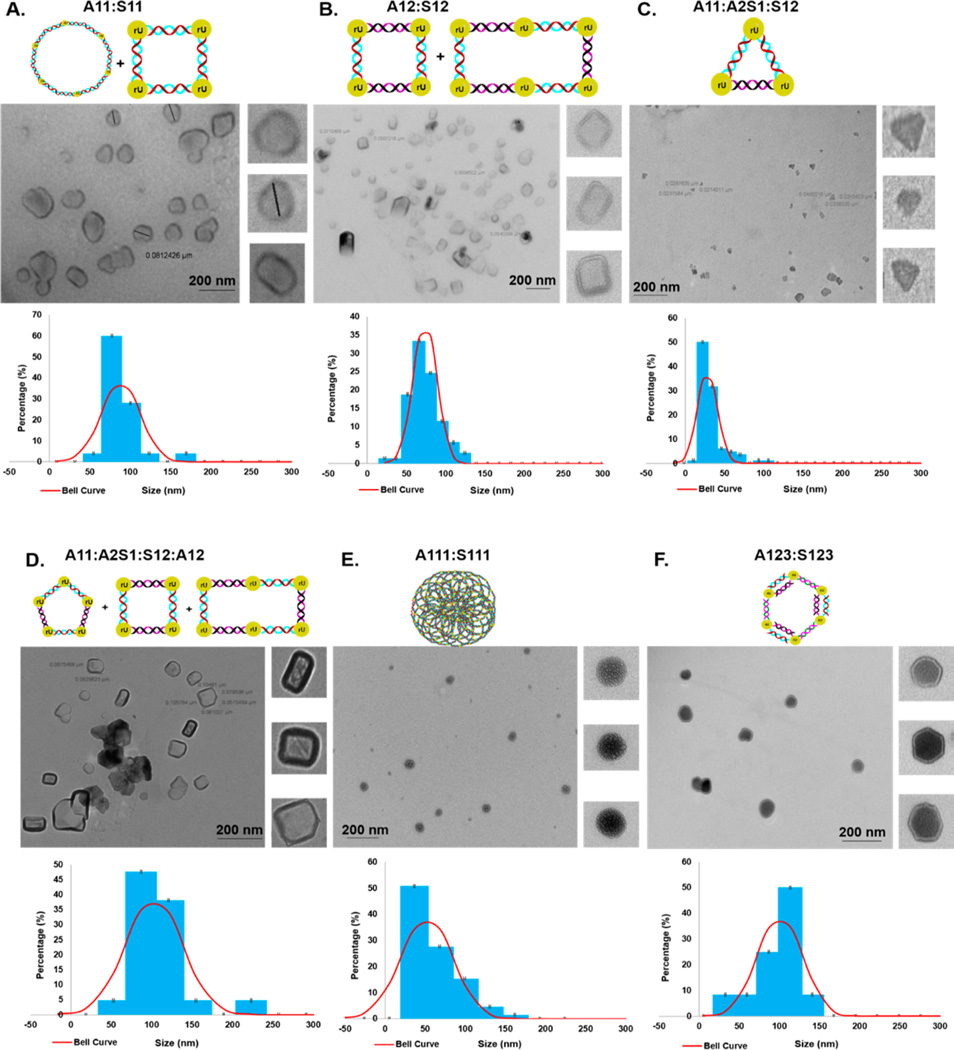

To determine the sizes and shapes of the siRNA hybrids detected on native PAGE, a transmission electron microscopy (TEM) study was conducted. Interestingly, the TEM images of the hybrid V- and Y-shaped siRNAs revealed nanostructures of well-defined geometries and size distributions in addition to the unavoidable appearance of aggregates that were not factored into our quantitative analyses (Figure 3). For example, the V-shape siRNA hybrid A11–S11 was found to self-assemble into circular and rectangular nanostructures having size distributions of 60–100 nm (Figure 3A). Comparatively, the TEM image of the V-shape siRNA hybrids A12–S12 self-assembled to form squares (60–80 nm) with a few elongated (80–110 nm) rectangular shape nanostructures (Figure 3B). The nanoparticle formulation formed from hybridizing three complementary V-shape RNA templates (namely, A11–A2S1–S12) self-assembled into triangle-shaped siRNA nanostructures, having mostly smaller size distributions of 10–50 nm (Figure 3C). Pushing the boundaries of siRNA self-assembly, the complementary V-shape templates composed of A11–A2S1–S12–A12 generated pentagons of sizes 90–100 nm and squares and rectangles of sizes ranging from 60 to 80 and from 100 to 120 nm, respectively, (Figure 3D). The Y-shaped siRNA hybrid A123–S123 formed hexagonal shaped nanostructures ranging in sizes from 80 to 120 nm (Figure 3F). Comparatively, the Y-shaped siRNA hybrid A111–S111 was uniquely shown to self-assemble into porous spheres, with diameters ranging from ~20–~110 nm and with pore sizes as small as 3–30 nm (Figure 3E). This novel type of RNA nanomaterial may be especially useful in small molecule encapsulation and release applications, such as those belonging to the stable RNA nanoparticles that have been used in drug delivery for cancer therapy.22

Figure 3.

Sizes and shapes of siRNA nanostructures. TEM images and particle size distribution plots of (A) V-shape siRNA hybrids A11–S11, (B) V-shape siRNA hybrids A12–S12, (C) V-shape siRNA hybrids A11–A2S1–S12, (D) V-shape siRNA hybrids A11–A2S1–S12–A12, (E) Y-shaped siRNA hybrids A111–S111, and (F) Y-shaped siRNA hybrids A123–S123.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was used to explore whether the siRNA nanostructures maintained the prerequisite A-type helix geometry for RNAi applications.23 The linear siRNAs displayed typical CD profiles for A-form helices, with a minimum peak at 240 nm and a broad maximum in between 250 and 290 nm.24 In the case of the self-assembled V- and Y-shape siRNA hybrids (see Figure S12), the A-type broad maximum and minimum bands were observed between 250 and 290 and 240 nm, respectively, albeit with a decrease in the amplitudes of the molar ellipticities at these characteristic wavelengths. Despite this change, the self-assembled V- and Y-shape siRNA hybrids maintained CD signatures that were consistent with the A-form RNA helix.

siRNA hybrid stabilities were measured by thermal denaturation (Tm). The V-shaped siRNA hybrids were found to be very stable, with high Tm values obtained for A11–S11 (Tm = 84 °C) and A12–S12 (Tm = 78 °C); see Figure S11. The V-shaped RNA templates hybridized with their complementary linear strands showed good thermal stabilities (A11–S1–S1, Tm = 76 °C and A12–S1–S2, Tm = 77 °C). Similarly, the Y-shaped siRNA hybrids, A111–S111 and A123–S123 were also found to be stable (Tm = 69 °C and Tm = 63 °C, respectively). While the Y-shaped RNA template hybridized to its complementary linear RNA, strands formed siRNA hybrids, which maintained good thermal stabilities (A111–S1–S1–S1, Tm = 62 °C and A123–S1–S2–S3, Tm = 68 °C); see Figure S11. Taken altogether, the siRNA hybrids were found to maintain thermally stable, A-type helices within their higher-ordered nanostructure formulations, making them promising candidates for their applications in RNAi nanotechnology.

siRNA Transfections

Prior to our RNAi screen, siRNA transfections were optimized within the GRP78 overexpressing AN3CA endometrial cancer (EC) cell line (ATCCHTB-111).25–31 The linear, A1–S1, and the Y-shape, A123–S1–S2–S3 GRP78-targeting siRNAs were selected as test samples along with a nonspecific (NS) RNA control. The benchmark transfection reagents, Lipofectamine 2000, siLentFect, and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX were tested for their transfection efficiencies according to the manufacture’s protocol. Briefly, the transfection reagents (2.5–7 µL) were mixed with the siRNAs (15 and 30 nM) for 20 min at room temperature (22 °C) and then added to the AN3CA cell culture, which was incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. Cell images were collected periodically during the incubation period and revealed the greatest extent of cell growth inhibition for the RNAiMAX-mediated siRNA transfections (see Figures S13 and S16). The enhanced efficiency of the RNAiMAX transfections was also supported by the most pronounced GRP78 knockdown effect (>90%) as detected by Western blot, which also led to the most significant cell death response (35–55%) according to a cytotoxic lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay (see Figure S14).32 The Y-shape siRNA hybrids, A123–S1–S2–S3, were found to be more active than the linear siRNA control, A1–S1, exhibiting a greater GRP78 knockdown effect (>97% versus 90%), which translated to a stronger inhibition of the AN3CA cells’ growth (>99% versus ~30%), which ultimately led to a more pronounced cell death effect (58% versus 32%) at 30 nM and over a 3 day incubation period (see Figures S13–S16). These results have effectively served to validate the potent anticancer effects of the multifunctional Y-shape siRNA, paving the way for a vigorous screening assay for evaluating the SARs of the GRP78-targeting siRNAs within the AN3CA EC cells.

Screening of 24 siRNA Samples

Our hybridization and self-assembly approach has enabled a small library of 24 siRNA samples for evaluating their SARs in the AN3CA EC cells. RNAiMAX transfections of 24 siRNA samples at single doses (15 nM) within the AN3CA cells were evaluated over a 3 day incubation period. Cell growth data obtained from the Incucyte (24–72 h) revealed the most significant growth inhibition (70–95%) for the multifunctional siRNA nanostructures, while the control linear siRNAs and the NS RNA samples exhibited modest effects (5–50%) on the growth of the AN3CA cells (see Figure S17A). The Western blots confirmed the anticipated GRP78 knockdown effects, with the V- (e.g., A12–S1–S2) and Y-shape (e.g., A123–S123) siRNAs triggering the most potent responses (>95%); see Figure S17B. Interestingly, the Y-shape siRNAs targeting three different GRP78 mRNA sites (A123–S1–S2–S3 and A123–S123) produced the most marked effects on GRP78 knockdown (>95%) in comparison to the linear siRNA controls targeting single (A1–S1, 15%), double (A1–S1 + A2–S2, 80%), and triple (A1–S1 + A2–S2 + A3–S3, 85%) oncogenic GRP78 mRNA sites. Moreover, these synergistic responses were also observed when the levels of the cleaved 85 kDa protein poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (Cl-PARP), a molecular marker of apoptosis in cells (Figure S17B), were monitored.33 For example, the potent Y-shape siRNA (A123–S1–S2–S3) demonstrated significant GRP78 knockdown and growth inhibition (>90%, 15 nM), with notable increases in Cl-PARP levels (~50%). Comparatively, the linear control siRNAs (A1–S1 + A2–S2 + A3–S3) resulted in less (~30%) Cl-PARP expression. Taken altogether, the multifunctional siRNAs stimulate synergistic anticancer responses in the AN3CA EC cells. These effects supersede those seen by the control siRNAs, even when added in combination, making the siRNA nanostructures more promising candidates for RNAi screening and cancer gene therapy applications.

siRNA Leads

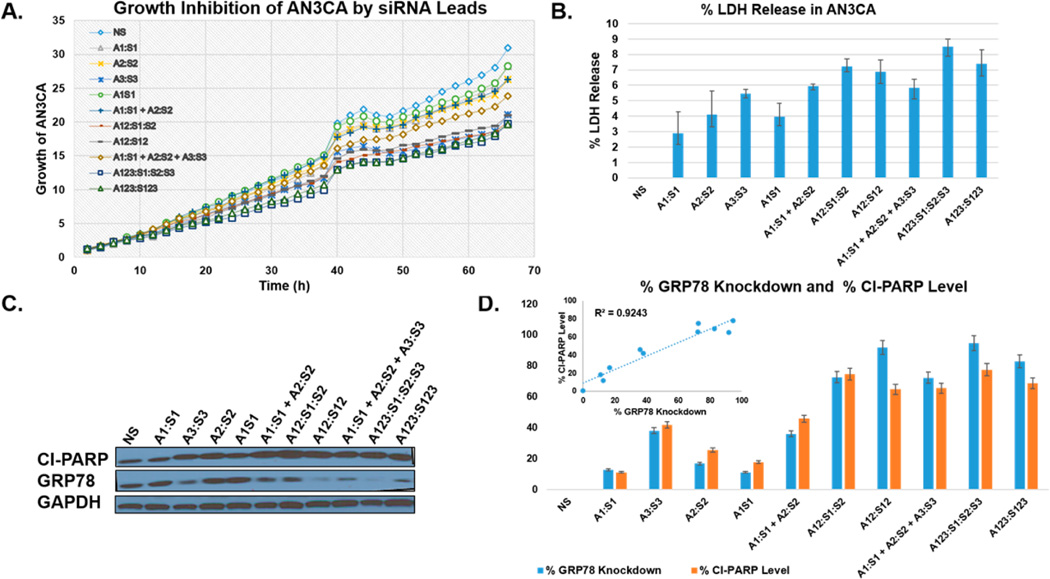

From the single-dose 24 sample siRNA screen, four V- (A12–S1–S2 and A12–S12) and Y-shape (A123–S1–S2–S3 and A123–S123) siRNA nanostructures were selected to validate the potency of their RNAi activity relative to their corresponding linear NS RNA and the siRNA (A1–S1, A2–S2, A3–S3, A1S1, A1–S1 + A2–S2, A1–S1 + A2–S2 + A3–S3) controls (Figure 4). The siRNA nanostructures, which exhibited the most pronounced anticancer effects, determined based on GRP78 knockdown, Cl-PARP levels, and cell growth inhibition in our siRNA screen (Figure S17) were selected as leads. As anticipated, the self-assembled siRNA hybrids inhibited the AN3CA cells’ growth to about a 40% greater extent relative to the siRNA controls (Figure 4A). A LDH release assay confirmed the cytotoxicities of the siRNA formulations, even at low dosages (5 nM), with the Y-shape A123–S1–S2–S3 siRNA exhibiting the most lethal (~10%) effects (Figure 4B). Moreover, Western blot validated their potent GRP78 knockdown efficiencies, with ≥80% knockdown observed for the V- and Y-shape siRNA hybrids, and the linear controls exhibited at most ~75% GRP78 knockdown when added in combination (Figure 4C,D). Western blot also confirmed that the Cl-PARP levels indicative of apoptosis were found at significantly increased levels in the cases of the V-shape (A12–S1–S2, ~75% and A12–S12, ~65%) and the Y-shape (A123–S1–S2–S3, ~77% and A123–S123, ~69%) siRNAs relative to their linear controls (~10–~65%).

Figure 4.

Biological evaluation of the siRNA leads. (A) The AN3CA cell growth curves (0–66 h) obtained from the Incucyte following RNAiMAX (7 µL) transfections of the siRNAs (5 nM). (B) LDH release assay following siRNA transfections. The percent LDH released was measured for the siRNAs and normalized according to the NS RNA. (C) Western blot of the total GRP78 and Cl-PARP levels following siRNA transfections. The loading control, GAPDH, was used to normalize the detected bands for quantitative densitometry using NIH imager (ImageJ). (D) The percent GRP78 knockdown and the percent Cl-PARP levels were normalized according to the NS RNA control and quantitated following densitometry of the Western blot. The linear (r2 = 0.9243) correlation diagram in between the percent GRP78 knockdown and the percent Cl-PARP levels is provided as an inset. All experiments were replicated in triplicate, with average values presented with their standard deviations about the mean. Statistical analyses produced error bars with acceptable variance ± SEM; N = 3; p < 0.05.

Interestingly, a direct correlation was observed in between GRP78 knockdown and increased levels of Cl-PARP, indicating that GRP78 knockdown may be directly contributing to apoptosis in the AN3CA EC cells. Taken altogether, this study unveils the potent and long-lasting anticancer activities of the V- and Y-shape GRP78-targeting siRNA hybrids within the AN3CA EC cells at exceptionally low dosages (5 nM) and for an extended duration of action (72 h). Furthermore, these new siRNA motifs may be developed into multifunctional probes for screening the influence of multiple oncogene targets on cancer cell biology and for enhancing the gene therapy effects within malignant tumors.

RNAi Screening

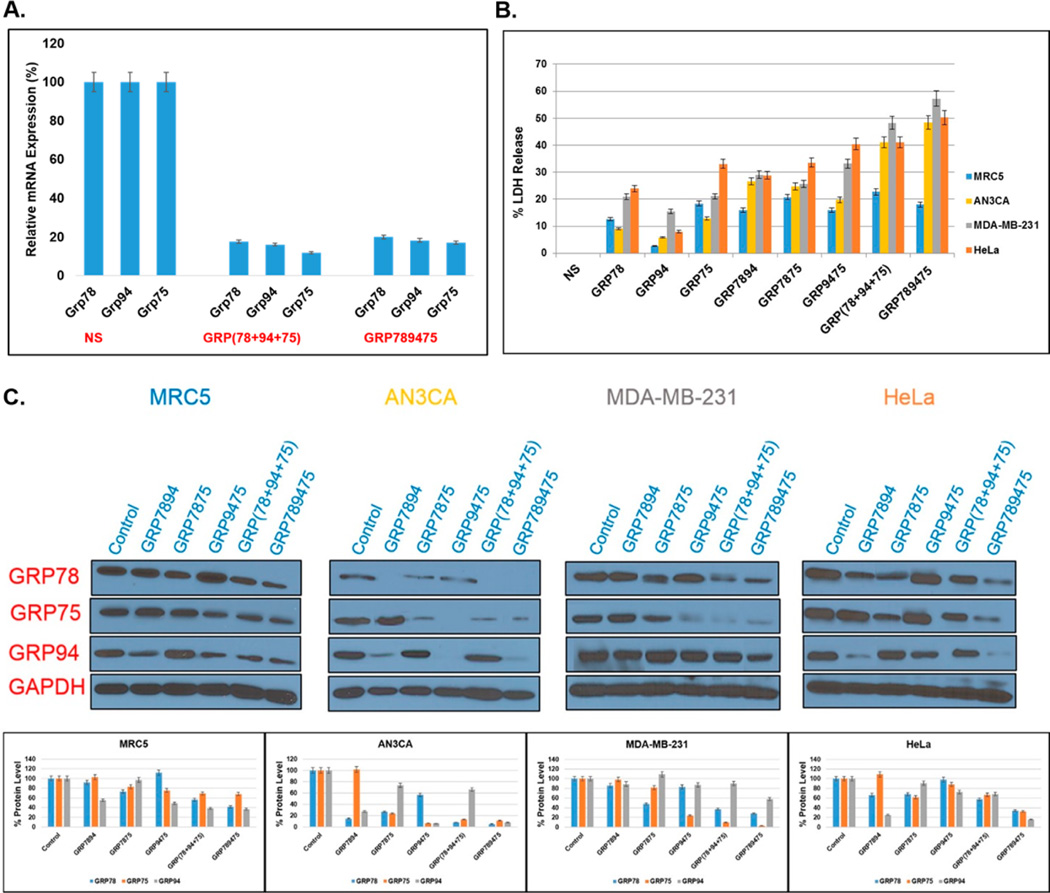

The GRP overexpressing human cervical HeLa (ATCC CCL-2),20 endometrial AN3CA,29–31 and breast MDA-MB-231 (ATCC HTB-26)16 cancer cells, in addition to a nontumorigenic lung fibroblast MRC5 (ATCC–CCL-171)34 cell line displaying normal GRP function, were used as representative models to explore the influence of the glucose-regulated chaperones GRP-75, 78, and 94 on cell viability (see Figure S18). The linear and V- and Y-shape siRNA hybrids respectively targeting single, double, and all three GRPs were used as molecular probes for exploring cancer cell biology in our RNAi screening strategy (see Table S1). The linear GRP-75, 78, and 94 siRNAs, used in combination, demonstrated notable (20–90%) knockdown of GRP expression, which translated into modest effects on cell growth inhibition (10–30%) and cell death (30–40%) in all cell lines tested (Figure 5). The Grp mRNA knockdown levels in HeLa cells were confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which indicated comparable Grp-75, 78, and 94 mRNA silencing with the multitargeting Y-shape siRNA (GRP759478) and the control linear siRNAs targeting the same oncogenes (Figure 5A). With respect to the protein levels of GRP-75, 78, and 94, the V-shape siRNA hybrids targeting double chaperones (GRP7578, GRP7594, and GRP7894) showed sequence specific knockdown in all cell lines (20–95%) with varied effects on the expression levels of the nontargeted chaperone (Figure 5C). For example, within the AN3CA cells, GRP-78 and 94 knockdown had little influence on the expression levels of GRP75, whereas GRP-75 and 94 knockdown led to a significant (40%) reduction in the GRP78 expression levels. Similar trends were delineated across different cell lines. For example, knockdown of GRP-75 and 94 led to a decrease in the expression levels of GRP78 within the AN3CA cells but not within the HeLa cells, suggesting that the cell lines have varied levels of GRP addiction (Figure 5C). This assumption was validated by their varied effects on cell growth inhibition (30–50%) and death (20–40%). Representatively, GRP-75 and 94 knockdown translated to about a 2-fold increase in cell death within the HeLa relative to the AN3CA cell lines, underscoring a critical role of these chaperones on HeLa cell survival (Figure 5B). The most potent anticancer effects were observed with the trifunctional Y-shape siRNA targeting GRP-75, 78, and 94. In this case, potent (50–95%) knockdown was observed in all cancer cell lines, which translated to significant levels of tumor cell cycle arrest (50–80%) and cancer cell death (50–60%). In comparison, the multiple GRP78-targeting Y-shape siRNA (A123–S1–S2–S3) triggered only about 10% AC3CA cell death (Figure 4B), whereas the GRP-75, 78, and 94 targeting Y-shape siRNA produced a 5-fold increase (50%) in cytotoxicity at low doses of 5 nM (Figure 5B). The results observed for the Y-shape siRNA targeting GRP-75, 78, and 94 supersede the anticancer effects observed from all other siRNA hybrids tested in our study and underscores the synergistic influence of compromising chaperone activity in cancer. Moreover, GRP knockdown with the GRP-75, 78, and 94 targeting Y-shape siRNA had a more pronounced effect on tumor cell growth inhibition (50–80%) and death (50–60%) in comparison to the control, nontumorigenic MRC5 cell line, which displayed modest growth inhibition (10–30%) and death (10–20%). These results correlate an addiction of human cancer cells to the overexpressed glucose-regulated chaperones, which may directly contribute toward cancer treatment selectivity.35 Therefore, the self-assembled siRNA hybrids targeting multiple GRPs proved useful in screening these important oncogene targets for elucidating their role in cancer cell biology while improving siRNA therapeutic efficacy and specificity in cancer.

Figure 5.

RNAi screening. (A) Grp mRNA levels detected by RT-PCR. HeLa cells were transfected with NS RNA, linear GRP (78 + 94 + 75), and Y-shape GRP(789475) siRNA (5 nM) using RNAiMAX (7 µL). Grp78, Grp94, Grp75, and Gapdh mRNA levels were normalized according to Gapdh and quantitated with respect to NS RNA. (B) LDH release assay. The percent LDH released was measured following transfections of all treated cell lines (MRC5, AN3CA, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa). The LDH levels were quantitated and normalized according to the NS RNA. (C) Western blots measuring GRP78, GRP94, and GRP75 (percent protein) levels following siRNA (5 nM) transfections in normal lung, MRC5, endometrial, AN3CA, breast, MDA-MB-231, and cervical HeLa cancer cells. The GRP78, GRP94, and GRP75 levels were normalized according to GAPDH and quantified with respect to the NS RNA. Data represents knockdown efficiency of V-shape siRNAs (GRP7894, GRP7875, and GRP9475), Y-shape siRNA (GRP789475), and the linear siRNAs (GRP78 + GRP94 + GRP75) added in combination. All experiments were replicated in triplicate, with average values presented with their standard deviations about the mean. Statistical analyses produced error bars with acceptable variance ± SEM; N= 3; p < 0.05.

siRNA Serum Stability

The serum stability of selected siRNAs and their corresponding RNA templates were evaluated in fetal bovine serum (FBS). The linear (A1–S1), V- (A12–S12) and Y-shaped (A123–S1–S2–S3 and A123–S123) siRNAs in comparison with the linear (A1), V-shape (A12), and Y-shape (A123) RNA templates were treated with 10% FBS and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Periodically, aliquots were collected, concentrated and suspended in gel loading buffer for 16% native PAGE analyses (see Figures S19 and S20). As expected, the linear siRNA completely degraded, even after shorter incubation times of 4 h. These results confirm the limited duration of action and therapeutic index of the native siRNAs that are readily degraded by nucleases present in serum.36 Moreover, the linear (A1), V-shape (A12), and Y-shape (A123) RNA templates were completely degraded after 24 h treatment. However, the higher-order siRNA hybrids formed from the V- and Y-shape RNA templates (A12–S12, A12–S1–S2 and A123–S123, A123–S1–S2–S3, respectively) were found to undergo partial degradation after a 48 h incubation period. These results confirm that the higher-order siRNA nanostructures formed from the V-and Y-shape RNA templates impart partial stability to the nucleases present in serum, which likely contributes to their prolonged duration of action relative to the linear siRNA hybrids. These results are consistent with the observed serum stability of other RNA nanostructures, suggesting that higher-order structure formulation may contribute to enhanced serum stability.37 Moreover, site specific or gapmer modifications to the siRNA sequences have also been shown to improve resistance toward nuclease degradation and may be incorporated to further enhance serum or plasma stability while retaining potent silencing activity.38

Conclusions

We have effectively demonstrated the rational design and applications of RNA templates in the self-assembly of discrete, higher-order siRNA nanostructures for RNAi screening and cancer gene therapy applications. The novel siRNA nanostructures created in this study have expanded the repertoire of multifunctional siRNAs. The representative examples found in the literature have demonstrated the ability for higher-ordered siRNA nanostructures to behave as Dicer substrates and release multiple siRNAs that led to synergistic knockdown effects of reporter genes.6–10,37,38 These proof-of-concept studies demonstrated the potential utility of siRNA nanostructures in RNAi screening and cancer gene therapy applications. In our study, the design, synthesis, and applications of V- and Y-shape RNA templates led to the self-assembly of novel siRNA nanostructures that demonstrated unprecedented utility in RNAi screening of oncogene targets and cancer gene therapy applications. More specifically, the V- and Y-shape RNA templates hybridized to their complementary RNA sequences generated higher-order siRNA hybrids according to a native PAGE analysis. These siRNA hybrids were found to self-assemble into unique shapes and well-defined structures according to TEM imaging. Moreover, thermal denaturation and CD spectroscopy were, respectively, used to confirm the prerequisite siRNA hybrid stabilities and A-form helices for invoking RNAi activity. In endometrial cancer, the higher-order siRNA hybrids were found to trigger synergistic anticancer effects, which surpassed those observed with the linear siRNAs. The V- and Y-shape siRNA hybrids induced potent (>95%) GRP78 knockdown, which inhibited tumor cell growth (35–55%) and stimulated programmed cell death according to the release of LDH and the increase in the 85-kDa Cl-PARP fragment, a molecular marker of apoptosis.33 In an RNAi screen across a panel of GRP overexpressing cancer cell lines and a nontumorigenic control displaying regulated levels of GRP, the multifunctional V- and Y-shape siRNAs targeting GRP-75, 78, and 94 displayed synergistic anticancer effects, which superseded their linear controls or the V- and Y-shape siRNAs targeting GRP78 alone. The RNAi screen also revealed the influence of GRP activity on cell viability. The GRP overexpressing cancer cells were sensitized to GRP-75, 78, and 94 knockdown resulting in greater tumor cell cycle arrest and cytotoxicity relative to the nontumorigenic control. These studies revealed a greater dependence of human cancer cells to the overexpressed glucose regulated chaperones, which was found to contribute to cancer treatment selectivity. A FBS serum stability assay provided preliminary mechanistic insights into the anticancer activity of the siRNA hybrids. In these experiments, the linear siRNAs and the RNA templates were found to quickly degrade in the presence of serum nucleases. Whereas the siRNA nanostructures were found to undergo only partial degradation after a 48 h incubation period in 10% FBS. Therefore, the higher-order V- and Y-shape siRNA hybrids were found to confer greater resistance toward degradation in serum that may likely contribute to the long-lasting oncogene knockdown and anticancer effects observed in our study. Additional mechanistic studies are currently underway to elucidate the complete mechanism of action of the siRNA hybrids. In conclusion, a new class of siRNA bioprobes are reported for studying RNAi activity in cancer and also for screening important (single or multiple) oncogene targets for successful applications in cancer gene therapy.

Methods

Solid-Phase Synthesis and Deprotection of RNA

Solid-phase RNA synthesis reagents and materials were purchased from ChemGenes or Glen Research Inc., and used without further purification. The synthesis of the branchpoint phosphoramidite and its incorporation within V- and Y-shape RNA was accomplished according to our previously published method.11 Following synthesis, the oligonucleotides were deprotected from the solid support (7:3 v/v NH4OH–EtOH, 60 °C, 12–14 h) and desilylated (1:1.2 v/v trimethylaminetrihydrofluoride TEA-3HF–DMSO, 55 °C, 2 h), and the crude oligonucleotide pellets were precipitated in 3MNaOAc (25 µL) and n-BuOH (1 mL).

siRNA Hybridization

A 50 µM stock solution of each RNA sample was prepared in autoclaved Millipore H2O. To the templates (20 µL, 50 µM) was added the complementary RNA strands (20 µL, 50 µM) and annealing buffer (60 µL, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) to afford the hybrid mixtures (100 µL,10 µM). The resulting mixtures were heated to 95 °C for 3–5 min on a heating block, slowly cooled to room temperature (22 °C) over 2 h, and stored in the fridge at 4 °C overnight (12–14 h) prior to analysis.

Nondenaturing Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

The hybridized siRNA samples (20 µM) in annealing buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5–8.0, 8 µL) were suspended in 30% sucrose loading buffer (15 µL in 5× TBE). Samples were then loaded on a 16% native, nondenaturing PAGE and run at 300 V, 100 mA, and 12 W for 2.5 h. Following electrophoresis, the siRNA bands were visualized under UV shadowing (260 nm) and stained with a Stains-All (Sigma-Aldrich) solution.

TEM Imaging

siRNA hybrid samples (50 µL, 50 µM) were suspended in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7, 1 mL) and sonicated for 15 min for complete dissolution. Samples were then mixed in 1:1 v/v ratio with 1% uranyl acetate and sonicated for an additional 10 min. An aliquot (5 µL) of siRNA sample was placed on a carbon-film-coated copper grid of 300 mesh (Electron Microscopy Sciences Inc., Hatfield, PA), dried overnight and viewed under the transmission electron microscope (JEOL, model JEM-1200 EX). Images were taken with a SIA-L3C CCD camera (Scientific Instruments and Applications, Inc.) using the software Maxim DL5 (Diffraction Limited, Ottawa, Canada).

Serum Stability Assay

siRNA hybrid samples (A1, A12, A123, A1–S1, A12–S12, A12–S1–S2, A123–S123, A123–S1–S2–S3) were hybridized as previously described in annealing buffer (0.75 µM, 10 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5–8.0, 1 mL). An aliquot (10 µL, 5 µM) was added to a 10% FBS solution (40 µL in phosphate buffer). The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C, and periodically (0–48 h), sample aliquots (10 µL) were removed and suspended in 1.5× TBE loading buffer (15 µL) and frozen at −80 °C prior to analyses. Samples were thawed to room temperature (22 °C) and analyzed on a 16% native, nondenaturing PAGE for 2.5 h. The gel was then visualized with a Stains-All (Sigma-Aldrich) solution.

siRNA Transfections in AN3CA Cells

Briefly, the AN3CA endometrial cancer cells (ATCC HTB-111, 1 × 105) were plated in six-well culture plates containing MEM culture media with 10% FBS. Cells were cultured for 48 h in a humidified incubator set at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Prior to transfections, the siRNA hybrids (5 µL, 2.5–12.5 µM, in DMEM, 250 µL) were mixed with the transfection reagents (Lipofectamine 2000, Silentfect, or RNAiMAX, 2.5–7 µL in DMEM, 250 µL) according to the manufacture’s recommendation. The mixtures were incubated (10 min, 22 °C) then added to the AN3CA cell culture and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 over a three-day period. Cell growth over time (65–72 h) was monitored in an Incucyte (Essen BioScience).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Grp mRNA was isolated from the HeLa cervical cancer cell lines using the manufacturer’s protocol (TRIzol, ThermoFisher Scientific). The RNA pellet was dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated H2O. The total mRNA levels were quantitated by measuring the absorbance of collected RNA samples at 260 nm. The isolated RNAs (1.5 µg of each sample) were treated with gDNA Wipeout buffer at 42 °C to eliminate residual genomic DNA. These samples were then reverse-transcribed using Quantiscript reverse transcriptase, Quantiscript RT Buffer, and RT Primer Mix according to manufacturer’s protocol (QIAGEN). Additionally, the samples were incubated with RNaseH to remove RNA, and the resulting cDNAs were then diluted to 100 µL with distilled water. Each quantitative PCR consisted of 5 µL of cDNA template, 12.5 µL of PerfCta SYBR Green Supermix, Low ROX (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA), and 500 nM of forward and reverse primers in a final volume of 25 µL. For human Grp78, the primer sequences were 5′-ACCTCCAACCCCGAGAACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTCAACCACCTTGAACGGC-3′ (reverse). For human Grp94, they were 5′-ACTGTTGAGGAGCCCATGGAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTGAAGAGTCTCGCGGGAAAC-3′ (reverse). For human Grp75, they were 5′-AGCTGGAATGGCCTTAGTCAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGGAGTTGGTAGTACCCAAATC-3′ (reverse). For Gapdh, they were 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ (reverse). The reactions were carried out on an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for 30 cycles (95 °Cfor 15 s and 60 °Cfor 45 s) after an initial 3min of incubation at 95 °C. The fold change in the expression of each gene was calculated using the standard curve method, with Gapdh used as an internal control for normalization.

Western Blots

The cell media was aspirated from the transfected culture and washed with PBS buffer for 2–3 min twice. The cells were lysed using cell lysis buffer (1% Tween-20, 50 mM Tris, 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (Protease inhibitor, PSMF, Phos2, and Phos3). Protein concentration of lysates were determined using the BSA protein assay reagent (Thermo- Fisher Scientific Inc.). Proteins samples (15–20 µg, 20 µL) were dissolved in 5× loading buffer, boiled for 5–7 min, and resolved in 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories), which was blocked in Tris-buffered saline, pH 8.0, Tween-20, 5% (w/v) skim milk (TBST solution) for 1 h at room temperature (22 °C). Membranes were then probed with the indicated primary antibodies (anti-PARP p85 fragment pAb, Promega Inc. and anti-GRP78 pAb, Cell Signaling Inc.) in TBST solution at 4 °C overnight. Next day, membranes were washed with TBST solution (three times, 10 min each) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3000) at room temperature for 1 h followed by washing with TBST solution (three times, 10 min each). Immunoblotted protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) and quantified using NIH imager (ImageJ)

Cell Cytotoxicity

Following transfection with GRP78 specific siRNAs, a cytotoxicity assay was performed with all cells using the Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.). With this kit, the rate of cell lysis is monitored by determination of the LDH amount released into the culture medium and quantified at 492 nm by the detection of the red formazan chromophore.

Acknowledgments

Funding

U.S. acknowledges financial support from the Undergraduate Research and Mentoring Education (URME) program at Queens College. J.K. is grateful for funding support from the Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA for Individual Postdoctoral fellowship award (F32 CA192786–01).

Experiments performed at MSKCC were supported in part by the NIH (P01 CA186866 to GC).

This research was gratefully supported by Seton Hall University. The authors acknowledge Dr. Allan Blake for insightful discussions on cancer cell biology and Dr. Anthony Maina, who pioneered the synthesis method for V- and Y-shape siRNA. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Mark Hail at Novatia LLC, who conducted the MS analyses of the RNA samples synthesized in this study. The authors also thank The Core Facility for Imaging, Cellular, and Molecular Biology at Queens College.

ABBREVIATIONS

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- CD

circular dichroism spectroscopy

- Tm

thermal denaturation

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- GRP75

glucose-regulated protein 74

- GRP78

glucose- regulated protein 78

- GRP94

glucose-regulated protein 94

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- Cl-PARP

cleaved PARP

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

- Additional details on experimental methods. Tables showing linear sequence numbers. Figures showing RP IP HPLC chromatogram of V-shapes A11 RNA (9), A12 RNA (10), S11 RNA (11), S12 RNA (12), A2S1 RNA (13), A1S1 RNA (14), A111 RNA (15), A123 RNA (16), S111 RNA (17), and S123 RNA (18); thermal denaturation of V- and Y-shaped siRNAs; circular dichroism spectroscopy of V- and Y-shaped siRNAs; optimization of siRNA transfections in AN3CA cells; LDH release assay following siRNA transfections; Western blot of the totalGRP78 levels following siRNA transfections; cell growth images of the treated AN3CA EC cells; a 24 siRNA screen; cell growth curves; and siRNA FBS stability assays. (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Naldini L. Nature. 2015;526:351–360. doi: 10.1038/nature15818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajith TA. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 2015;11:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masiero M, Nardo G, Indraccolo S, Favaro E. Mol. Aspects Med. 2007;28:143–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam JK, Chow MY, Zhang Y, Leung SW. Mol. Ther.–Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e252. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaglione M, Messere A. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2010;10:578–595. doi: 10.2174/138955710791384036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo P. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:833–842. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shukla GC, Haque F, Tor Y, Wilhelmsson LM, Toulmé JJ, Isambert H, Guo P, Rossi JJ, Tenenbaum SA, Shapiro BA. ACS Nano. 2011;5:3405–3418. doi: 10.1021/nn200989r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afonin KA, Viard M, Kagiampakis I, Case CL, Dobrovolskaia MA, Hofmann J, Vrzak A, Kireeva M, Kasprzak WK, KewalRamani VN, Shapiro BA. ACS Nano. 2015;9:251–259. doi: 10.1021/nn504508s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afonin KA, Viard M, Koyfman AY, Martins AN, Kasprzak WK, Panigaj M, Desai R, Santhanam A, Grabow WW, Jaeger L, Heldman E, Reiser J, Chiu W, Freed EO, Shapiro BA. Nano Lett. 2014;14:5662–5671. doi: 10.1021/nl502385k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakashima Y, Abe H, Abe N, Aikawa K, Ito Y. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:8367–8369. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11780g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maina A, Blackman BA, Parronchi CJ, Morozko E, Bender ME, Blake AD, Sabatino D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:5270–5274. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee AS. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1992;4:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90042-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang LH, Zhang X. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;110:1299–1305. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roller C, Maddalo D. Front. Pharmacol. 2013;4:10. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang YJ, Huang YP, Li ZL, Chen CH. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dejeans N, Glorieux C, Guenin S, Beck R, Sid B, Rousseau R, Bisig B, Delvenne P, Buc Calderon P, Verrax J. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2012;52:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yi X, Luk JM, Lee NP, Peng J, Leng X, Guan XY, Lau GK, Beretta L, Fan ST. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:315–325. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700116-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firczuk M, Gabrysiak M, Barankiewicz J, Domagala A, Nowis D, Kujawa M, Jankowska-Steifer E, Wachowska M, Glodkowska-Mrowka E, Korsak B, Winiarska M, Golab Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e741. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee AS. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:263–276. doi: 10.1038/nrc3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki T, Lu J, Zahed M, Kita K, Suzuki N. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;468:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saar Ray M, Moskovich O, Iosefson O, Fishelson Z. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:15014–15022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.552406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shu Y, Pi F, Sharma A, Rajabi M, Haque F, Shu D, Leggas M, Evers BM, Guo P. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2014;66:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu YL, Rana TM. RNA. 2003;9:1034–1048. doi: 10.1261/rna.5103703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray DM, Hung SH, Johnson KH. Methods Enzymol. 1995;246:19–34. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)46005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray MJ, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Yoo E, Yang W, Wu E, Lee AS, Lin YG. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;133:21–30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bifulco G, Miele C, Di Jeso B, Beguinot F, Nappi C, Di Carlo C, Capuozzo S, Terrazzano G, Insabato L, Ulianich L. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012;125:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulianich L, Insabato L. Front. Med. 2014;1:55–60. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2014.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuo K, Gray MJ, Yang DY, Srivastava SA, Tripathi PB, Sonoda LA, Yoo EI, Duebeau L, Lee AS, Lin AS. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013;128:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luvsandagva B, Nakamura K, Kitahara Y, Aoki H, Murata T, Ikeda S, Minegishi T. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012;126:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H, Liu Z, Gou Y, Qin Y, Xu Y, Liu J, Wu JZ. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015;10:5505–5512. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S83838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calì G, Insabato L, Conza D, Bifulco G, Parrillo L, Mirra P, Fiory F, Miele C, Raciti GA, Di Jeso B, Terrazzano G, Beguinot F, Ulianich L. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014;229:1417–1426. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan FK, Moriwaki K, De Rosa M. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;979:65–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-290-2_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boulares AH, Yakovlev AG, Ivanova V, Stoica BA, Wang G, Iyer S, Smulson M. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:22932–22940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubporn A, Srisomsap C, Subhasitanont P, Chokchaichamnankit D, Chiablaem K, Svasti J, Sangvanich P. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2009;6:229–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taldone T, Ochiana SO, Patel PD, Chiosis G. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;35:592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hickerson RP, Vlassov AV, Wang Q, Leake D, Ilves H, Gonzalez-Gonzalez E, Contag CH, Johnston BH, Kaspar RL. Oligonucleotides. 2008;18:345–354. doi: 10.1089/oli.2008.0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grabow WW, Zakrevsky P, Afonin KA, Chworos A, Shapiro BA, Jaeger L. Nano Lett. 2011;11:878–887. doi: 10.1021/nl104271s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afonin KA, Kireeva M, Grabow WW, Kashlev M, Jaeger L, Shapiro BA. Nano Lett. 2012;12:5192–5195. doi: 10.1021/nl302302e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]