Abstract

Objective(s):

Scutellarin, a flavonoid extracted from the medicinal herb Erigeron breviscapus Hand-Mazz, protects neurons from damage and inhibits glial activation. Here we examined whether scutellarin may also protect neurons from hypoxia-induced damage.

Materials and Methods:

Mice were exposed to hypoxia for 7 days and then administered scutellarin (50 mg/kg/d) or vehicle for 30 days Cognitive impairment in the two groups was assessed using the Morris water maze test, cell proliferation in the hippocampus was compared using 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) immunohistochemistry, and hippocampal levels of nestin and neuronal class III β-tubulin (Tuj-1) were measured using Western blotting. These results were validated in vitro by treating cultured neural stem cells (NSCs) with scutellarin (30 μM).

Results:

Treating mice with scutellarin shortened escape times and increased the number of platform crossings, it increased the number of BrdU-positive proliferating cells in the hippocampus, and it up-regulated expression of nestin and Tuj-1. Treating NSC cultures with scutellarin increased the number of proliferating cells and the proportion of cells differentiating into neurons instead of astrocytes. The increase in NSC proliferation was associated with phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2, while neuronal differentiation was associated with altered expression of differentiation-related genes.

Conclusion:

Scutellarin may alleviate cognitive impairment in a mouse model of hypoxia by promo-ting proliferation and neuronal differentiation of NSCs.

Keywords: Cognitive deficits, Differentiation, Hypoxia, Neural stem cells, Proliferation, Scutellarin

Introduction

Originally thought to occur only during embryonic development, neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) continues throughout adulthood (1). During neurogenesis, neural stem cells (NSCs) differentiate into functionally integrated neurons (2). It may be possible to treat diseases involving cognitive defects by stimulating NSC proliferation and neuronal differentiation. For example, transplanting NSCs into the hippocampus restores cognitive deficits in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease (3, 4). Injection of NSCs into humans, however, raises significant ethical issues. Therefore researchers are exploring ways to promote the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of endogenous NSCs (5).

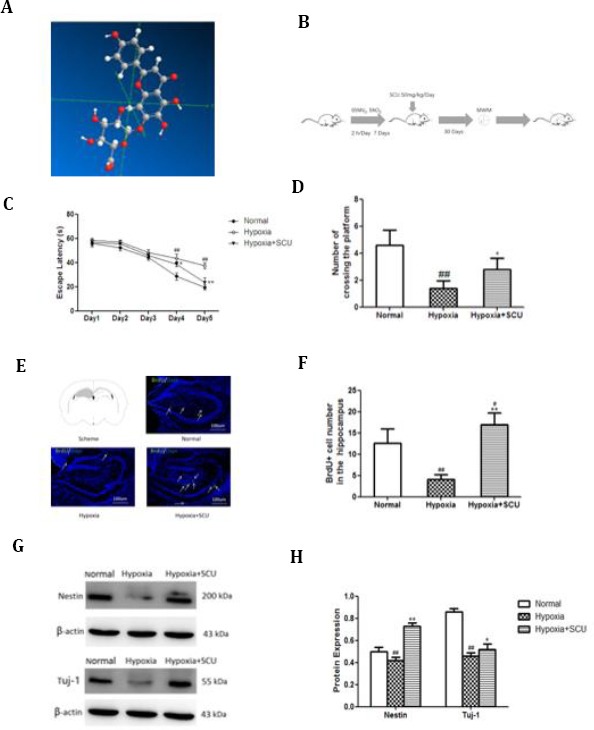

Scutellarin, a flavonoid in the medicinal herb Erigeron breviscapus Hand-Mazz (Figure 1A), has shown significant neuroprotective effects in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and stroke (6-8). Scutellarin also attenuates neuronal damage induced by a variety of insults including hypoxia (9-11). How scutellarin exerts these effects is unclear. The flavonoid crosses the blood-brain barrier and distributes widely in the brain, where it reduces vascular resistance and renders the blood-brain barrier more permeable (12). Another study showed that scutellarin protects NSCs in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis, alleviating behavioral deficits (13). The flavonoid may protect astrocytes against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury by stimulating neurotrophin synthesis and release (14). These findings led us to wonder whether scutellarin might also protect NSCs against hypoxia-induced injury.

Figure 1.

Scutellarin alleviates cognitive deficits in mice exposed to hypoxia, and these effects involve NSC proliferation and neuronal differentiation

(C) Escape latency assessed over 5 days in the Morris water maze test (n=10 per group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs hypoxia; ## P<0.01 vs healthy controls

(D) Number of crossings over the platform on day 6 in the Morris water maze test (n=10 per group). *P<0.05 vs hypoxia; ## P<0.01 vs healthy controls

(E) Evaluation of cell proliferation in the hippocampus based on anti-BrdU antibody staining. The counting area is indicated in gray. Arrows indicate BrdU-labeled cells.

(F) Quantitative analysis of the numbers of BrdU-positive cells in hippocampus (n=5 per group). **P<0.01 vs. hypoxia; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01 vs healthy controls

(G) Western blotting of hippocampal lysates with antibodies against nestin and Tuj-1

(H) Quantitative analysis of Western blots like those in panel G (n= 5 per group). Hypoxia decreased the expression of Nestin and Tuj-1, and scutarellin attenuated these effects. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs hypoxia; ## P<0.01 vs healthy controls

In the current study, we examined the potential neuroprotective effects of scutellarin in a mouse model of hypoxia and in NSC cultures. We provide evidence that scutellarin may reduce hypoxia-related learning and memory impairment in mice by enhancing the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of NSCs.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Scutellarin (98.6% pure) was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology (cat. no. YY90017; Shanghai, China). Antibody against mouse nestin was from Covance (cat. no. PRB-315C; New Jersey, USA). Antibodies against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; cat. no. MAB360) or BrdU (cat. no. MAB3510) were from Millipore (Massachusetts, USA). Antibodies against total ERK1/2 (cat. no. #4695) or phospho-ERK1/2 (cat. no. #4370) as well as the compound U0126 (cat. no #9903) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Massachusetts, USA). Phosphatase inhibi-tor cocktail tablets (cat. no. PhosSTOP) was from Roche Diagnostics (Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany). Anti-bodies against Tuj-1 (cat. no. T2200) or Ki67 (cat. no. AMAB90870), Trizol reagent (cat. no. T9424), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, cat. no. M2128) and RIPA buffer (cat. no. R0278) were from Sigma Aldrich (Missouri, USA). The following secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (CA, USA): Alexa Flour 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. A21202), Alexa Flour 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. A21206), Alexa Flour 594-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. A21203), and Alexa Flour 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. A21207). DMEM/F-12 (cat. no. 11320-033) and Accutase (cat. no. A11105-01) were from Gibco (California, USA). Matrigel (cat. no. 354277) was from BD Biosciences (New Jersey, USA). RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (cat. no. K1621) was from Invitrogen (California, USA). SYBR® Select Master Mix (cat. no. 4472919) was from Applied Biosystems (California, USA).

Animals and scutellarin treatment

Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kunming Medical University in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 80-23, revised 1996). Adult male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were obtained from the Peking Weitonglihua Laboratory Animal Center (Beijing, China) and exposed to hypoxia for 2 hr per day for 7 consecutive days in a chamber filled with 95% nitrogen and 5% oxygen (15). Then animals were divided into two groups that were injected intraperitoneally with either scutellarin dissolved in 0.9% saline (50 mg/kg/d) or in 0.9% saline vehicle for 30 consecutive days (n=10 animals per group). The dosage and treatment duration were based on previous findings (16).

Morris water maze test

At 24 hr after the last injection, cognitive function was assessed using a Morris water maze test essentially as described (15, 17), with few modifications. In addition, 10 healthy mice not exposed to hypoxia were analyzed as a positive control. A black cylindrical pool with a diameter of 120 cm was filled with water at 25±1 °C and divided into four equal quadrants. A platform with a diameter of 4.5 cm was placed in a fixed position in one quadrant of the pool, at a depth of 1 cm below the surface. Mice were subjected to four consecutive trials with a gap of 15 min per day for 5 consecutive days. In each trial, mice were placed into one of the four quadrants of the pool, facing the wall. The mouse was placed into a different quadrant in each trial. Mice were given 60 sec to find the platform, then they were allowed to rest on the platform for 20 sec; if a mouse failed to locate the platform within 60 sec, then it was guided to the platform and allowed to remain there for 20 sec. On day 6, each mouse was placed in one of the four quadrants (randomly selected) but with the platform removed, and the number of times that the animal crossed over the last location of the platform was measured over 60 sec.

BrdU labeling in vivo and anti-BrdU staining of hippocampal sections

Immediately after the water maze testing, five mice previously treated with scutellarin and subjected to hypoxia, five mice treated with vehicle and subjected to hypoxia, and five untreated mice not subjected to hypoxia were injected intraperito-neally with BrdU dissolved in 0.9% saline (50 mg/ kg) every 2 hr for a total of four injections. At 24 hr after the last injection, mice were sacrificed. The BrdU dosing schedule was based on previous findings (18). Hippocampal brain tissue sections (16 μm) from bregma -0.94 mm to -3.98 mm were prepared and stained using anti-BrdU antibody as described (13). First, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody (1:500), follow-ed by incubation for 1 hr with Alexa Fluor-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:1000). Then sections were counter-stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Slides were analyzed under the fluorescence microscope (Leica DFC420C, Germany) using Image J (NIH, Maryland, USA). The numbers of BrdU-positive cells in the hippocampus were counted; for each animal, 10-11 sections (0.24 mm apart from each other) were analyzed; the counting area is depicted in Figure 1E. Average cell counts per slide were determined (18).

Western blotting of hippocampal sections

Immediately after the water maze testing, the remaining five mice previously treated with scutellarin and subjected to hypoxia, five mice treated with vehicle and subjected to hypoxia, and five untreated mice not subjected to hypoxia were sacrificed, and hippocampal brain tissue was processed as described (19) for Western blotting. Briefly, tissue was homogenized in RIPA buffer containing phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and total protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay (CW0014S, CWBIO, Beijing, China). The supernatant was denatured by boiling, fractionated on 8% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin, and incubated overnight with a rabbit monoclonal antibody against nestin (1:800), rabbit monoclonal antibody against Tuj-1 (1:1000), or mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin (1:1000). Membranes were then incubated with a secondary antibody labeled with horseradish peroxidase (1:2000), and visualized using standard chemiluminescence. Band intensity was measured using Image J, and normalized to the intensity for β-actin.

NSC culture

Cultures of NSCs from the forebrain of embryonic mice (E14) were prepared as described (20, 21). Briefly, forebrain samples were digested with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA for 10 min at 37 °C, and cells were plated onto 12-well plates in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12) containing the following: 1% non-essential amino acid solution (NEAA), 2 mM GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM PenStrep, 4 mM B27, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF) and 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). The culture medium (200 μl) was replaced each day. Typically at 7 days after plating, primary spheres were treated with 400 μl Accutase (22) for 5 min at 37 °C. Cells were replated into 12-well plates at a density of 2.0 x 105 cells/well and passaged every 48 hr. Cells that had been passaged more than 5 times were cultured in DMEM/F12 containing the following: 1% NEAA, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 4 mM B27, 20 ng/ml EGF, 10 ng/ml bFGF, 50% Neuronal Base and 1% BSA. These cells were used in all further experiments. Their identity as NSCs was confirmed based on positive staining for the intermediate filament protein nestin (23).

Effects of scutellarin on NSC proliferation in vitro

NSCs in 96-well plates were exposed to scutellarin (1, 5, 10, 30, 50, or 100 µM) or DMSO vehicle for 48 hr, then processed in the MTT assay. Optical density values (reflecting numbers of viable cells) were normalized to that in the DMSO group. Suspension cultures in 12-well plates (2.0 x 105 cells/well) were exposed to scutellarin (30 µM) or DMSO vehicle for 48 hr, cells were photographed and counted using a hemocytometer. Relative growth was calculated as the number of cells counted, divided by the initial number. Adherent cultures in 12-well plates (2.0 x 105 cells/well) were exposed to scutellarin (30 µM) or DMSO vehicle for 48 hr, fixed and stained as described (24) with an antibody against Ki67 to label cells progressing through the cell cycle, followed by an antibody against nestin to confirm NSC identity. Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, incubated overnight with mouse monoclonal antibody against Ki67 (1:1000) as well as a rabbit polyclonal antibody against nestin (1:1000), followed by an Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000). In parallel, adherent cultures were exposed to scutellarin or DMSO vehicle for 44 hr, then BrdU solution (10 mg/ml) was added to each well, and cultures were incubated a further 4 hr in the dark. Cells were fixed and stained as describ-ed above but with a mouse primary monoclonal antibody against BrdU (1:500) to label DNA-synthesi-zing cells, followed by the anti-nestin antibody. Stained cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope (DFC420C, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) using Image J (NIH, Maryland, USA).

To examine the possible involvement of ERK1/2 in scutellarin-induced effects on NSC proliferation, NSCs were co-cultured with ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (3 μM) and scutellarin for 48 hr. Proliferation was examined using immunostaining against BrdU and nestin as described above.

Effects of scutellarin on neuronal differentiation of NSCs in vitro

NSCs were seeded into Matrigel-coated 24-well plates (5.0 x 104 cells/well) and cultured for 3 days in differentiation medium: DMEM/F12 supplemented with 50% Neuronal Base, 0.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM GlutaMAX, and 4 mM B27. Cells were treated with scutellarin (30 µM) or DMSO vehicle for 48 hr, then their differentiation into neuronal and astrocyte lineages was examined by staining cells as described above with rabbit polyclonal antibody against neuronal class III β-tubulin (Tuj-1, 1:1000) to label neuronal lineages, or with mouse monoclonal antibody against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:1000) to label astrocyte lineages.

In another set of experiments, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was used to analyze expression of nestin and the differentiation-related, basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factors neurogenin 1 (Ngn1) and enhancer of split 1 (Hes1) in NSCs treated with scutellarin (30 µM) or DMSO vehicle for 48 hr. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol, and used to prepare cDNA with the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. Levels of target mRNAs were quantified using primers designed with NetPrimer (www.premierbiosoft.com/netprimer) (25) or taken from the literature (15), SYBR® Select Master Mix and 40 cycles of amplification in an ABI 7300 thermocycler. The following primers were used: nestin forward, 5’-GCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTAAAAT-3’; nestin reverse, 5’-TTGGCTCCACCCTTCAAGTG-3’; Ngn1 forward, 5’-GA-CCTGCATCTCTGATCTCGAC-3’; Ngn1 reverse, 5’-ATTC-GATGCCCCGGAGAGG-3’; Hes1 forward, 5’-AGAGGCG-AAGGGCAAGAATAAAT-3’; Hes1 reverse, 5’-CCGGGAGC-TATCTTTCTTAAGTG-3’; GAPDH forward, 5’-GCTTCGG-CAGCACATATACTAAAAT-3’; GAPDH reverse: 5’-TTGG-CTCCACCCTTCAAGTG-3’. The 2△△CT method of relative quantification was applied, with levels of GAPDH mRNA serving as an internal control.

In a third set of experiments, Western blotting was used to examine levels of nestin, Tuj-1, total ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 in NSCs treated for 48 hr with DMSO, scutellarin (30 µM), or the combination of scutellarin and U0126. Cultures were processed and blotted as described above for total hippocampal lysates. The primary antibody against total ERK1/2 was rabbit polyclonal (1:1000); the antibody against phospho-ERK1/2 was rabbit monoclonal (1:2000).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean±SD and compared between groups using Student’s t test or ANOVA, followed by the LSD test for pairwise comparisons. The threshold of statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. Each condition was measured in triplicate (or more) in each experiment.

Results

Scutellarin alleviates cognitive deficits in mice exposed to hypoxia

As expected, hypoxia exposure resulted in significant cognitive deficits, which were detectable using the Morris water maze test. Hypoxia significantly prolonged the time needed to escape onto the platform (escape latency) on day 4 (43.80±3.27 vs 28.80±3.03 sec; P<0.01) and day 5 (37.60±2.41 vs 19.67±2.28 sec; P<0.01; Figure 1C). It also significantly reduced the number of times within a pre-specific period that the animals crossed over the area where the platform had been (1.40±0.54 vs 4.60±1.14; P<0.01; Figure 1D).

Scutellarin treatment attenuated these cognitive deficits, significantly shortening escape latency on day 4 (38.78±1.92 vs 43.80±3.27 sec; P<0.05) and day 5 (23.80±3.89 vs 37.60±2.41 sec; P<0.01; Figure 1C). It also increased the number of times that animals crossed over the area where the platform had been (2.80±0.83 vs 1.40±0.54; P<0.05; Figure 1D).

Scutellarin promotes cell proliferation in the hippocampus of mice exposed to hypoxia

As expected, hypoxia exposure decreased the number of BrdU-positive cells in the hippocampus (4.20±1.09 vs 12.60±3.36; P<0.01; Figure 1E-F). Scutellarin treatment of animals exposed to hypoxia resulted in a higher number of BrdU-positive cells than in healthy controls never exposed to hypoxia (17.00±2.74 vs. 12.60±3.36; P<0.05).

Scutellarin increases expression of nestin and Tuj-1 in hippocampus of mice exposed to hypoxia

Hypoxia reduced levels of nestin protein in the hippocampus (0.42±0.03 vs 0.50±0.04; P<0.01), and scutellarin treatment significantly increased this level (0.73±0.03 vs 0.42±0.03; P<0.01; Figure 1G-H). Similar results were observed with Tuj-1 after hypoxia alone (0.46±0.03 vs 0.86±0.03; P<0.01) and after hypoxia followed by scutellarin (0.52±0.05 vs 0.46±0.03; P<0.05; Figure 1G-H).

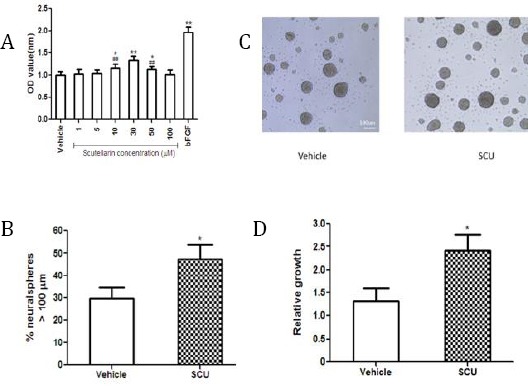

Scutellarin promotes NSC proliferation in vitro

To assess whether scutellarin has overall positive or negative effects on NSCs, we exposed NSC cultures to various concentrations of the flavonoid (1, 5, 10, 30, 50, 100 µM) and examined the changes in numbers of viable cells using the MTT assay. Doses of 10, 30, and 50 µM led to larger numbers of viable cells than those observed after vehicle treatment, with the 30 µM dose showing the best results (Figure 2A). Therefore, this dose was used in subsequent experiments. This was even higher than the relative proliferation index of 1.97 observed for positive control cultures incubated with 20 ng/ml bFGF instead of scutellarin.

Figure 2.

Scutellarin promotes NSC viability and growth

(A) NSCs were incubated with scutellarin (SCU) at various concentrations for 48 hr. NSC viability was assessed using the MTT assay (n=5 per group). **P<0.01, *P<0.05 vs vehicle; ## P<0.01 vs 30 µM SCU

(B) Bright-field images of dissociated neurospheres cultured for 48 hr in passaging medium.

(C) The proportion of total neurospheres with diameters >100 μm was counted. *P<0.05 vs vehicle

(D) Relative growth of NSCs (n=5 per group). *P<0.05 vs vehicle

The proportion of neurospheres that had diameters >100 μm was significantly larger after scutellarin treatment than after vehicle treatment (47.39±18.68% vs 29.89±15.33%; P<0.05; Figure 2B-C). In addition, relative proliferation of NSCs was significantly greater after scutellarin treatment (2.43±0.78 vs 1.32±0.64; P<0.05; Figure 2D).

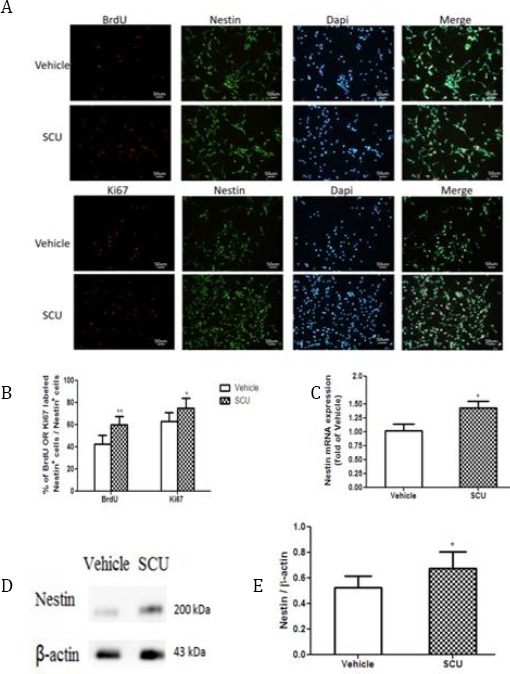

This increased proliferation correlated with an increased number of cells progressing through the cell cycle. Scutellarin increased the percentage of nestin-positive cells that were also positive for BrdU (60.07±7.41% vs 42.64±7.86%; P<0.01; Figure 3A-B). Similarly, it increased the percentage of nestin-positive cells that were also positive for Ki67 (75.32±8.65% vs 62.91±8.21%; P<0.05; Figure 3A-B).

Figure 3.

Scutellarin promotes NSC proliferation

(A) Cultured NSCs were stained with anti-nestin antibody and then additionally stained with antibody against Ki67 to detect active growth or antibody against BrdU to detect DNA synthesis

(B) Quantitative analysis of NSC proliferation (n=5 per group) *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs vehicle

(C) RT-qPCR analysis of nestin mRNA levels (n=3 per group) *P<0.05 vs vehicle

(D) Western blotting of cell lysates with antibody against nestin.

(E) Quantitative analysis of nestin protein levels in lysates (n=3 per group). *P<0.05 vs vehicle

These observed increases in NSC proliferation correlated with increases in levels of nestin mRNA measured using RT-qPCR. Scutellarin-treated cultures showed significantly higher levels of this mRNA than vehicle-treated cultures (1.43±0.26 vs 1.02±0.25; P<0.05; Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained at the level of nestin protein, based on Western blot analysis (Figure 3D-E).

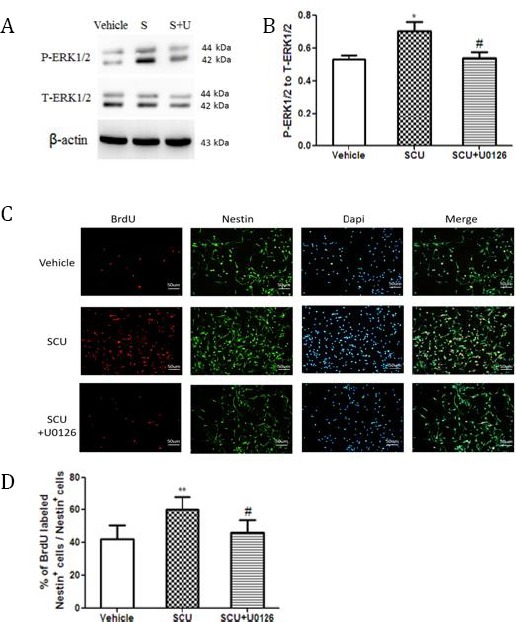

Scutellarin promotes NSC proliferation by activating the ERK pathway

Treating NSC cultures with scutellarin increased the ratio of phospho-ERK1/2 to total ERK1/2 (0.71±0.12 vs 0.53±0.05; P<0.05; Figure 4A-B), and this increase was reversed by including the ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (0.54±0.08 vs 0.71±0.12; P<0.05; Figure 4A-B). Furthermore, including this inhibitor reduced the percentage of nestin-positive cells that were also positive for BrdU (46.18±7.29% vs 60.07±7.41%; P<0.05; Figure 4C-D).

Figure 4.

The ERK1/2 pathway may be involved in scutellarin-induced NSC proliferation

(A) NSCs were treated with vehicle, scutellarin (SCU) or the combination of scutellarin and ERK1/1 inhibitor U0126 (S+U). Lysates were blotted using antibodies against total ERK1/2 (T-ERK1/2) or phospho-ERK1/2 (P-ERK1/2)

(B) Quantitative analysis of Western blots like that in panel A (n=3 per group). SCU increased the ratio of P-ERK1/2 to T-ERK1/2, which U0126 attenuated. *P<0.05 vs vehicle; #P<0.05 vs scutellarin

(C) NSCs were stained with antibodies against BrdU and nestin.

(D) Quantitative analysis of NSC proliferation (n=3 per group) **P<0.01 vs vehicle; #P<0.05 vs SCU

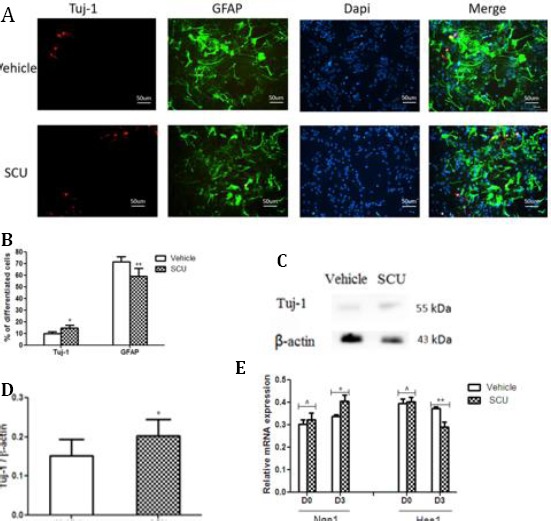

Scutellarin promotes neuronal differentiation of NSCs by altering expression of bHLH transcription factors

Scutellarin increased the percentage of cultured cells positive for Tuj-1 (14.68±2.73% vs. 10.18±1.63%; P<0.05; Figure 5A-B) and concomitantly decreased the percentage of cells positive for GFAP (59.22±6.73% vs 71.67±4.46%; P<0.01; Figure 5A-B). The increased percentage of Tuj-1-positive cells correlated with higher levels of Tuj-1 in Western blots (Figure 5C-D). The observed increase in Tuj-1 expression also correlated with higher levels of Ngn1 mRNA (0.41±0.06 vs. 0.34±0.02; P < 0.05) and lower levels of Hes1 mRNA (0.29±0.05 vs. 0.37±0.02; P < 0.01; Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Scutellarin promotes neuronal differentiation of NSCs

(A) NSCs were treated with SCU in differentiation medium for 3 days, and then stained with Tuj-1 and GFAP

(B) SCU increased the percentage of cells positive for Tuj-1 and decreased the percentage of cells positive for GFAP (n=3 per group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs vehicle

(C) Lysates from differentiated cells were analyzed by Western blotting with antibody against Tuj-1

(D) Quantitative analysis of blots like those in panel C (n=3 per group). *P<0.05 vs vehicle

(E) RT-PCR analysis of levels of mRNAs encoding Ngn1 and Hes1 (n = 3 per group). *P< 0.05, **P<0.01, ^ P>0.05 vs vehicle

Discussion

NSCs, located predominantly in the hippocampus and subventricular zone of the adult brain (3, 26), can be induced to proliferate and differentiate in response to various physiological and pathophysiological conditions (27, 28). This may provide a strategy for regenerating neuronal tissue lost as a result of injury or neurodegenerative disease (15, 29). Here we provide in vivo evidence that scutellarin can alleviate hypoxia-induced cognitive impairment, and we provide evidence both in vivo and in vitro that these therapeutic effects involve the ability of the flavonoid to stimulate the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of NSCs in the hippocampus.

Hypoxia exposure can induce cognitive deficits by decreasing neurogenesis in the hippocampus (30-32); consistent with this, animals in our study exposed to hypoxia showed fewer BrdU-positive cells in the hippocampus than controls. This decrease in neurogenesis correlated with delayed escape latency and fewer platform crossings. Scutellarin was able to alleviate all these effects. Our findings in this animal model of hypoxia extend previous work showing that scutellarin can protect cultured neurons against oxygen and glucose deprivation (10), as well as alleviate apoptosis resulting from cerebral hypoxic-ischemic injury (6).

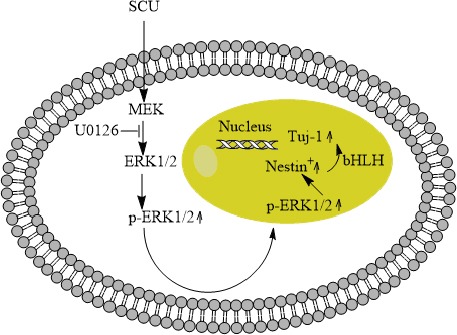

The MAPK signaling pathway is a critical regulator of NSCs (33), and up-regulation of ERK1/2 correlates with NSC proliferation (34, 35). Therefore we asked whether similar ERK1/2 up-regulation may help mediate the observed effects of scutellarin on NSC proliferation. We found that scutellarin increased the ratio of phospho-ERK1/2 to total ERK1/2 ratio, as well as the proportion of nestin-positive cells that were also positive for BrdU. Both effects were blocked by the ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126, suggesting that ERK1/2 activation contributes to the observed effects of scutellarin on NSCs (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A mechanistic model for how scutellarin may increase NSC viability and promote growth and proliferation Scutellarin may induce phosphorylation of ERK1/2, which then travels to the nucleus to influence expression of genes related to proliferation and differentiation, including genes encoding bHLH transcription factors

During neurodevelopment, bHLH transcription factors help determine whether NSCs differentiate and if so, whether they differentiate into neurons or astrocytes (36). Activator-type bHLH factors such as Ngn1 promote neuronal differentiation of NSCs; repressor-type bHLH factors such as Hes1 promote NSC proliferation (37). Interaction between the two types of bHLH transcription factors determines whether NSCs remain as NSCs or differentiate (38). In our NSC cultures, scutellarin up-regulated Ngn1 and down-regulated Hes1, consistent with the idea that scutellarin may induce neuronal differentiation of NSCs by altering the expression of bHLH transcription factors (Figure 6).

Conclusion

Here we provide evidence that scutellarin may attenuate cognitive deficits induced by hypoxia, and that it may do so by promoting the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of NSCs. Our preliminary mechanistic studies suggest at least two molecular processes that may underlie these effects: activation of the MAPK signaling pathway and regulation of bHLH transcription factors.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by The “Ten, Hundred, Thousand People of Talents Project” for Kunming health technology talents and internal research institutions and the construction project of technology center for treating senile mental disorders [SW (tech)-33], The training project of Yunnan senior health technology talents in 2016, The grant from Education Department of Yunnan Province, China (2016ZZX093).

References

- 1.Sola S, Aranha MM, Rodrigues CM. Driving apoptosis-relevant proteins toward neural differentiation. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:316–331. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suh H, Deng W, Gage FH. Signaling in adult neurogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:253–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acharya MM, Martirosian V, Chmielewski NN, Hanna N, Tran KK, Liao AC, et al. Stem cell transplantation reverses chemotherapy-induced cognitive dysfunction. Cancer Res. 2015;75:676–686. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marei HE, Farag A, Althani A, Afifi N, Abd-Elmaksoud A, Lashen S, et al. Human olfactory bulb neural stem cells expressing hNGF restore cognitive deficit in Alzheimer’s disease rat model. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:116–130. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassanzadeh K, Nikzaban M, Moloudi MR, Izadpanah E. Effect of selegiline on neural stem cells differentiation: a possible role for neurotrophic factors. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18:549–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yiming L, Wei H, Aihua L, Fandian Z. Neuroprotective effects of breviscapine against apoptosis induced by transient focal cerebral ischaemia in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:349–355. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.3.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S, Wang H, Guo H, Kang L, Gao X, Hu L. Neuroprotection of Scutellarin is mediated by inhibition of microglial inflammatory activation. Neuroscience. 2011;185:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo LL, Guan ZZ, Huang Y, Wang YL, Shi JS. The neurotoxicity of beta-amyloid peptide toward rat brain is associated with enhanced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis, all of which can be attenuated by scutellarin. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2013;65:579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong H, Liu GQ. Scutellarin protects PC12 cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2007;9:135–143. doi: 10.1080/10286020412331286470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu W, Zha RP, Wang WY, Wang YP. Effects of scutellarin on PKCgamma in PC12 cell injury induced by oxygen and glucose deprivation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1573–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo H, Hu LM, Wang SX, Wang YL, Shi F, Li H, et al. Neuroprotective effects of scutellarin against hypoxic-ischemic-induced cerebral injury via augmentation of antioxidant defense capacity. Chin J Physiol. 2011;54:399–405. doi: 10.4077/CJP.2011.AMM059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu M, Li H, Luo G, Liu Q, Wang Y. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of surface modification polymeric nanoparticles. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31:547–554. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang WW, Lu L, Bao TH, Zhang HM, Yuan J, Miao W, et al. Scutellarin Alleviates Behavioral Deficits in a Mouse Model of Multiple Sclerosis, Possibly Through Protecting Neural Stem Cells. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;58:210–220. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai L, Guo H, Li H, Wang S, Wang YL, Shi F, et al. Scutellarin and caffeic acid ester fraction, active components of Dengzhanxixin injection, upregulate neurotrophins synthesis and release in hypoxia/-reoxygenation rat astrocytes. JEthnopharmacol. 2013;150:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, Wang Z, Zhan J, Zhang Q, Wang J, Zhang Q, et al. Hydrogen sulfide promotes proliferation and neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells and protects hypoxia-induced decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;116:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin LL, Liu AJ, Liu JG, Yu XH, Qin LP, Su DF. Protective effects of scutellarin and breviscapine on brain and heart ischemia in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:327–332. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3180cbd0e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin G, Bai D, Yin S, Yang Z, Zou D, Zhang Z, et al. Silibinin rescues learning and memory deficits by attenuating microglia activation and preventing neuroinflammatory reactions in SAMP8 mice. Neurosci Lett. 2016;629:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu YH, Zhang CW, Lu L, Demidov ON, Sun L, Yang L, et al. Wip1 regulates the generation of new neural cells in the adult olfactory bulb through p53-dependent cell cycle control. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1433–1442. doi: 10.1002/stem.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu XS, Bao TH, Ke Y, Sun DY, Shi ZT, Tang HR, et al. Hint1 suppresses migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro by modulating girdin activity. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:14711–14719. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5336-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwindt TT, Motta FL, Gabriela FB, Cristina GM, Guimaraes AO, Calcagnotto ME, et al. Effects of FGF-2 and EGF removal on the differentiation of mouse neural precursor cells. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2009;81:443–452. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652009000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YH, Chung JI, Woo HG, Jung YS, Lee SH, Moon CH, et al. Differential regulation of proliferation and differentiation in neural precursor cells by the Jak pathway. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1816–1828. doi: 10.1002/stem.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo X, Lian R, Guo Y, Liu Q, Ji Q, Chen J. bFGF and Activin A function to promote survival and proliferation of single iPS cells in conditioned half-exchange mTeSR1 medium. Hum Cell. 2015;28:122–132. doi: 10.1007/s13577-015-0113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rietze RL, Valcanis H, Brooker GF, Thomas T, Voss AK, Bartlett PF. Purification of a pluripotent neural stem cell from the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2001;412:736–739. doi: 10.1038/35089085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang PS, Wang J, Zheng Y, Pallen CJ. Loss of protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha (PTPalpha) increases proliferation and delays maturation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12529–12540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.312769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veazey KJ, Carnahan MN, Muller D, Miranda RC, Golding MC. Alcohol-induced epigenetic alterations to developmentally crucial genes regulating neural stemness and differentiation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1111–1122. doi: 10.1111/acer.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennea NL, Mehmet H. Neural stem cells. J Pathol. 2002;197:536–550. doi: 10.1002/path.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piao CS, Li B, Zhang LJ, Zhao LR. Stem cell factor and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor promote neuronal lineage commitment of neural stem cells. Differentiation. 2012;83:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu T, Zhou H, Wang T, Lu L, Li F, Liu B, et al. In vitro characteristics of valproic acid and all-trans-retinoic acid and their combined use in promoting neuronal differentiation while suppressing astrocytic differentiation in neural stem cells. Brain Res. 2015;1596:31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eendebak RJ, Lucassen PJ, Fitzsimons CP. Nuclear receptors and microRNAs: Who regulates the regulators in neural stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boissard CG, Lindner MD, Gribkoff VK. Hypoxia produces cell death in the rat hippocampus in the presence of an A1 adenosine receptor antagonist: an anatomical and behavioral study. Neuroscience. 1992;48:807–812. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthuraju S, Maiti P, Solanki P, Sharma AK, Amitabh Singh SB, et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors enhance cognitive functions in rats following hypobaric hypoxia. Behav Brain Res. 2009;203:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaparro E, Quiroga C, Erasso D, Bosco G, Rubini A, Mangar D, et al. Isoflurane prevents learning deficiencies caused by brief hypoxia and hypotension in adult Sprague Dawley rats. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2014;29:895–900. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2013.866658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stachowiak EK, Fang X, Myers J, Dunham S, Stachowiak MK. cAMP-induced differentiation of human neuronal progenitor cells is mediated by nuclear fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR1) J Neurochem. 2003;84:1296–1312. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu J, Zhao SD, Liu HJ, Yuan QH, Liu SM, Zhang YM, et al. Melatonin promotes proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells subjected to hypoxia in vitro. J Pineal Res. 2011;51:104–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z, Liu DX, Wang FW, Zhang Q, Du ZX, Zhan JM, et al. L-Cysteine promotes the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells via the CBS/H(2)S pathway. Neuroscience. 2013;237:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Hatakeyama J, Ohsawa R. Roles of bHLH genes in neural stem cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Kobayashi T. Roles of Hes genes in neural development. Dev Growth Differ. 2008;1:S97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katakura M, Hashimoto M, Shahdat HM, Gamoh S, Okui T, Matsuzaki K, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid promotes neuronal differentiation by regulating basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors and cell cycle in neural stem cells. Neuroscience. 2009;160:651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]