Abstract

Background

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is associated with a higher incidence of distant metastasis and decreased survival. Whether TGF-β can be used as a prognostic indicator of colorectal cancer (CRC) remains controversial.

Methods

The Medline, EMBASE and Cochrane databases were searched from their inception to March 2016. The studies that focused on TGF-β as a prognostic factor in patients with CRC were included in this analysis. Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were analysed separately. A meta-analysis was performed, and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Results

Twelve studies were included in the analysis, of which 8 were used for OS and 7 for DFS. In all, 1622 patients with CRC undergoing surgery were included. Combined HRs suggested that high expression of TGF-β had a favourable impact on OS (HR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.10–2.59) and DFS (HR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.03–1.19) in CRC patients. For OS, the combined HRs of Asian studies and Western studies were 1.50 (95% CI: 0.61–3.68) and 1.80 (95% CI: 1.33–2.45), respectively. For DFS, the combined HRs of Asian studies and Western studies were 1.42 (95% CI: 0.61–3.31) and 1.11 (95% CI: 1.03–1.20), respectively.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis demonstrates that TGF-β can be used as a prognostic biomarker for CRC patients undergoing surgery, especially for CRC patients from Western countries.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3215-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Transforming growth factor-beta, TGF-β, Prognosis, Meta-analysis

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies worldwide. In terms of frequency, colorectal cancer ranked third in North America and Europe and fifth in Asia among malignant diseases [1, 2]. More than 1.2 million patients are diagnosed with CRC every year, and of these, more than 600,000 die [3]. The 5-year survival rate for patients with metastatic CRC is 10-15%, whereas for patients with non-metastatic CRC, the rate is 40-90% [4]. Recent advances in genetic and molecular characterisation of CRC have yielded a set of prognostic and predictive biomarkers that aid in the identification of patients at a higher risk for disease recurrence and progression [5]. Some investigators have reported that drugs that target signalling pathways involved in tumourigenesis; for example, cetuximab for wild-type K-ras CRC [6], and bevacizumab for CRC [7], improve survival of patients with CRC over chemotherapy alone [6–8].

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family includes TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3, which are expressed during tumour progression [9]. TGF-β has been shown to be a critical regulator and is considered a tumour suppressor because it inhibits cell cycle progression and stimulates apoptosis in the early stages of cancer progression [10, 11]. However, TGF-β may transform from an inhibitor of tumour cell growth to a stimulator of growth and invasion in advanced stages of CRC [12–14]. TGF-β can modulate cancer-related processes, such as cell invasion, distant metastasis, and modification of the microenvironment in advanced stages of CRC.

Many studies have been performed to assess the prognostic value of TGF-β in patients with CRC, but the conclusions of these studies have been inconsistent. Some studies demonstrated that high expression of TGF-β was associated with worse survival of patients with CRC [15, 16] whereas some studies failed to show any statistically significant association between high expression of TGF-β and survival in patients with CRC [10, 17]. Thus, it is unclear whether high expression of TGF-β is associated with worse survival in CRC patients. To our knowledge, no meta-analysis has been performed to assess the prognostic effects of TGF-β. Therefore, our goal was to combine all the results from published studies, after which we systematically evaluated the essential roles of TGF-β in colorectal cancer.

Methods

Search strategy

The meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement [18]; the PRISMA 2009 Checklist is shown in additional files (Additional file 1). Two reviewers independently conducted a systematic literature search of the following databases from the database inceptions to March 8th, 2016: PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The search included the following terms:

“colorectal” OR “large intestine” OR “large bowel” OR “colon” OR “colonic” OR “rectal” OR “rectum”

“cancer” OR “carcinoma” OR “tumor” OR “tumour” OR “neoplasm” OR “cancers”

“TGF-β” OR “TGF-β1” OR “transforming growth factor”

“prognosis” OR “prognoses” OR “prognostic” OR “predictive” OR “biomarker” OR “marker” OR “survival” OR “survive” OR “Cox” OR “Log-rank” OR “Kaplan-Meier”

The search was not limited by language. The specific search strategy is shown in the additional files (Additional file 2).

The systematic reviews and meta-analyses on TGF-β and CRC were manually reviewed for potentially relevant studies. Relevant studies were also retrieved using Google scholar with the following search terms: “colorectal cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer”, “TGF-β, TGF-β1 or transforming growth factor” and “prognoses, predictive or survive”.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria included the following four aspects. (1) Patients diagnosed with CRC (including colon cancer and rectal cancer) were eligible for inclusion. Patients with different clinical stages, histological types, or treatment methods were all included but patients with other diseases were excluded. (2) The expression of TGF-β (protein, mRNA) was measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry (IHC) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in primary CRC (including colon cancer, or rectal cancer) tissues. (3) The association between TGF-β and patient prognosis (i.e., overall survival [OS], disease-free survival [DFS], and/or relapse-free survival [RFS]) was investigated; the hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI), or the relevant information was provided. (4) A full paper was published in English. The eligible studies included cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, and even randomised controlled trials. When the same author reported multiple studies from the same patient population, the most recent study or the most complete study was included. The studies published in abstract form were considered only if sufficient outcome data could be retrieved from the abstract or from communication with the authors.

Study selection

Duplicate studies from different databases were identified, and the remaining abstracts were read for eligibility by two independent authors (ZQC and SLZ); the studies with inconsistent results were reviewed by the third author (XLC). The full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and reviewed independently by two authors (ZQC and SLZ). Any disagreements were recorded and resolved by consensus under the guidance of the third author (XLC).

Data collection

The eligible studies were reviewed, and the data were extracted independently by two authors (ZQC and SLZ). The study information (the first author, the year of publication), study participants (the histological type of CRC, gender, mean age, and sample sizes), the characteristics of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), the characteristics of TGF-β (gene subtypes, test samples, test content, test methods), and prognostic outcomes of interest (OS and/or DFS) were extracted. If data from any of the above categories were not reported in the study, the item was recorded as “NR (not reported)”.

Data analysis

Overall survival and disease-free survival were analysed separately for the eligible studies. The TGF-β value was classified as either “high expression” (overexpression) or “low expression”. For the quantitative aggregation of the survival times, the impact of TGF-β overexpression on survival times was measured. HRs and associated 95% CI were combined as effective values. If the HRs and 95% CI were given explicitly in the studies, we used the crude values. If these data were not given explicitly, they were calculated from the available numerical data or from the survival curve using the methods reported by Tierney. [19].

Heterogeneity of the individual HRs was calculated using Chi-square tests. A heterogeneity test with inconsistency index (I 2) statistic and Q statistic was performed. If the HRs were found to be homogenous, a fixed-effect model was used for analysis; if not, a random effect model was used. Subgroup analyses were performed for different countries (Asia, the West [Europe and America]) and analytical methods (univariate analysis, multivariate analysis). A P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. An observed HR > 1 implied a worse prognosis in terms of high expression of TGF-β compared with low expression of TGF-β. The publication bias was evaluated using the methods of Begg [20]. All the calculations were performed using STATA version 12.0.

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 916 studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). In all, 181 studies were excluded as duplicates. The titles and abstracts of 735 studies were reviewed by two reviewers, and 698 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The full texts of the remaining 37 studies were retrieved for review, and 24 studies were excluded after secondary screening. Eventually, 13 studies were included [10, 13, 15–17, 21–28]. The study conducted by Langenskiöld [23] was not included for analysis for the following reasons: (1) it had a great impact on the combined HR and accounted for 99% of the weight due to its small standard error of HR (0.005); (2) the study analysed colon cancer and rectal cancer separately; and (3) it is very difficult to get the small standard error in such a sample size (136). Therefore, 12 studies were eligible for this meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the search strategy

The major characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Nine studies were conducted in European countries (UK, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Poland, Greece and Bulgaria) and in the United States (US), and four were conducted in Asian countries (China, Japan and Korea) [21, 22, 25, 26]. All the eligible studies were published between 1995 and 2015. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 34 to 206 patients (median: 124 patients). In all, 1622 CRC patients were included. All patients included in the eligible studies underwent surgical resection. Only one study investigated rectal cancer [22], and two investigated colon cancer [25, 27], whereas other studies investigated colorectal cancer. One study included stage III patients [22], and one study included stage I-III patients [23]. Other studies included patients with all stages of CRC.

Table 1.

The main characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Year of publication | Country | Time | Sample size | Males | Mean of age (range) | Patients | Stage (UICC) | Differentiation | Surgery | Chemo−/Radio-therapy | Follow-up time (median, months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhu J | 2015 | China | 2003–2009 | 115 | 70 | 62 (29, 89) | CRC | All | All | All | NR/NR | NR |

| Chun HK | 2014 | Korea | 2006–2007 | 201 | 132 | 58.6 | Rectal cancer | III | All | All | Partial/Partial | 57.8 |

| Langenskiöld M | 2013 | Sweden | 1999–2003 | 136 | 78 | 75 (44, 91) | CRC | I-III | All | All | Partial/No | 51.0 |

| Uhlmann ME | 2012 | Germany | 1998–2001 | 103 | 67 | 66.7 | CRC | All | NR | All | NR/NR | 104.5 |

| Lampropoulos P | 2012 | Greece | 2005–2006 | 195 | 103 | 68.6 (36, 90) | CRC | All | NR | All | No/No | 56.0 |

| Li X | 2011 | China | 2003–2004 | 147 | 86 | NR (24, 87) | Colon cancer | All (Duke’s stage) | NR | All | Partial/No | ≥ 60.0 |

| Khanh do T | 2011 | Japan | 1998–2005 | 206 | 114 | 63.3 (19, 92) | CRC | All | All | All | Partial/NR | ≥ 60.0 |

| Wincewicz A | 2010 | Poland | 2004–2008 | 72 | 35 | NR | CRC | All | Moderate and poor | All | NR/NR | NR |

| Gulubova M | 2010 | Bulgaria | 1997–2006 | 142 | 92 | 65 b (39, 96) | CRC | All | All | All | NR/NR | 37.6 |

| Bellone G | 2010 | Italy | 2004–2008 | 75 | 47 | NR (24, 87) | Colon cancera | All (Duke’s stage) | NR | All | NR/NR | 44.0 |

| Tsamandas AC | 2004 | Greece | 1990–1998 | 124 | 79 | 66 b (25, 82) | CRC | All | All | All | Partial/Partial | 68.0 |

| Robson H | 1996 | UK | NR | 72 | 47 | 70 (32, 92) | CRC | All | All | All | NR/NR | ≥ 36.0 |

| Friedman E | 1995 | US | 1994 | 34 | 18 | 64.6 | CRC | NR | NR | All | NR/NR | 57.3 (mean) |

CRC Colorectal cancer, NR not reported

aOnly included adenoma and adenocarcinoma of the colon

bMedian of age

Table 2.

The TGF-β information and results of the included studies

| Gene subtype | High expression (%) | Test sample | Test content | Test method | Analytic method | Outcome | HR for OS | 95% CI HR for OS | HR for DFS | 95% CI HR for DFS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhu J | TGF-β1 | 53.0 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Multivariate | OS | 3.33 | 1.41–7.87 | NR | NR |

| Chun HK | TGF-β1 | 14.9 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Multivariate | DFS | NR | NR | 9.19 | 1.26–67.20 |

| Langenskiöld M | TGF-β1 | NR | Tissue | Protein | ELISA | Multivariate | OS | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | NR | NR |

| Uhlmann ME | TGF-β | 25.2 | Tissue | mRNA | PCR | Surv curve | OS | 1.13 | 0.42–3.03 | NR | NR |

| Lampropoulos P | TGF-β | 71.3 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Multivariate | OS | 4.68 | 2.09–10.48 | NR | NR |

| Li X | TGF-β1 | 70.7 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Univariate | OS, DFS | 0.75 | 0.48–1.16 | 0.81 | 0.55–1.20 |

| Khanh do T | TGF-β1 | 55.3 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Multivariate | OS, RFS | 1.62 | 0.74–3.56 | 1.46 | 0.74–2.87 |

| Wincewicz A | TGF-β1 | 83.3 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Survival curve | DFS | NR | NR | 1.00 | 0.93–1.07 |

| Gulubova M | TGF-β1 | 25.4 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Surv curve | OS | 1.35 | 0.82–2.23 | NR | NR |

| Bellone G | TGF-β1 | NR | Serum | Protein | ELISA | Multivariate | DFS | NR | NR | 1.11 | 1.03–1.20 |

| Tsamandas AC | TGF-β1 | 79.0 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Multivariate | OS, DFS | 1.55 | 1.33–3.08 | 1.09a | 0.27–4.4 |

| Robson H | TGF-β1 | 58.3 | Tissue | Protein | IHC | Surv curve | OS | 0.56 | 0.15–2.14 | NR | NR |

| Friedman E | TGF-β1 | 58.8 | Tissue | Protein | PCR | Surv curve | DFS | NR | NR | 3.33 | 0.47–23.43 |

DFS disease-free survival, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, IHC Immunohistochemistry, Multivariate Multivariate survival analyses, NR not reported, OS overall survival, PCR Polymerase chain reaction, RFS recurrence-free survival (which was used as DFS), Surv curve survival curve, Univariate Univariate survival analyses

a:the result was analysed by the Univariate method

Eight studies reported the prognostic value of TGF-β with respect to OS in CRC patients (Table 2). Of the 8 studies, 6 directly reported the HRs, while the other 3 studies provided survival curves. Three studies identified high expression of TGF-β as an indicator of poor prognosis in terms of OS [13, 16, 21], whereas others showed no significant difference. Seven studies reported the prognostic value of TGF-β for DFS in CRC patients (Table 2). Of these 7 studies, 5 directly reported the HRs, while the other 2 studies provided survival curves. Two out of the 7 studies identified high expression of TGF-β as an indicator of poor prognosis in terms of DFS [22, 27], whereas others showed no significant difference.

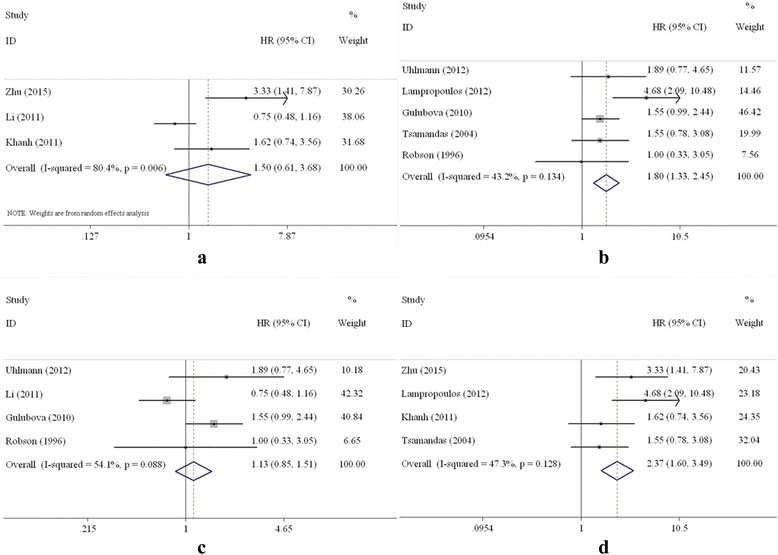

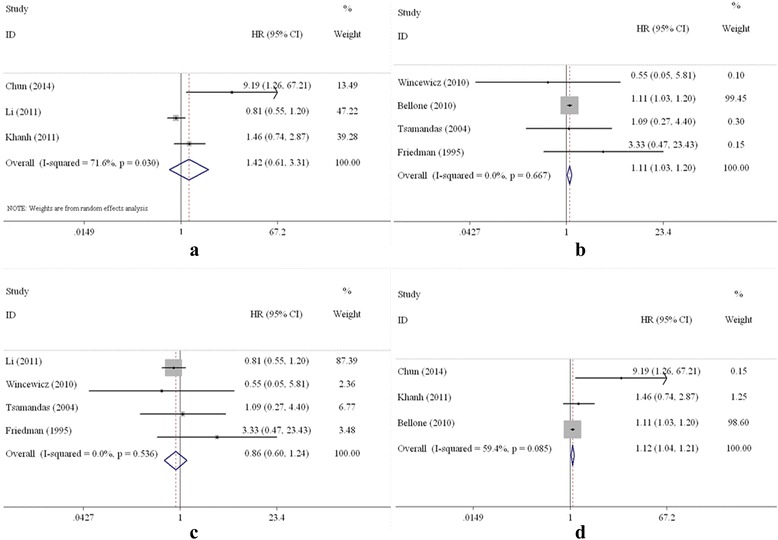

Meta-analysis of OS

Eight studies that focused on the relationship of TGF-β expression to overall survival of CRC patients undergoing surgery were included in the meta-analysis [10, 13, 15, 16, 21, 24–26]. The combined HR value of the 8 studies that evaluated the high expression of TGF-β with respect to OS was 1.68 (95% CI: 1.10–2.59, Table 3, Fig. 2), which indicates that high expression of TGF-β was associated with a poor OS of patients with CRC. When the subgroups were analysed based on country, the combined HRs of the Asian studies and the Western studies were 1.50 (95% CI: 0.61–3.68) and 1.80 (95% CI: 1.33–2.45), respectively (Fig. 3). Subgroup analyses were performed according to the analytical method of the individual studies. The combined HR of the studies based on multivariate analysis was 2.37 (95% CI: 1.60–3.49; Fig. 3). However, the relationship between TGF-β overexpression and OS was not statistically significant (HR = 1.13, 95% CI: 0.85–1.51; Fig. 3) according to the univariate analysis.

Table 3.

Results of the meta-analysis

| Number of studies | Number of patients | HR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I2, χ2, P) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||

| All | 8 | 1119 | 1.68 (1.10–2.59)a | 67.0%, 21.21, 0.003 |

| Univariate analysis | 4 | 479 | 1.13 (0.85–1.51) | 54.1%, 6.54, 0.088 |

| Multivariate analysis | 4 | 640 | 2.37 (1.60–3.49) | 47.3%, 5.69, 0.128 |

| Country | ||||

| Asian | 3 | 468 | 1.50 (0.61–3.68)a | 80.4%, 10.21, 0.006 |

| Western | 5 | 651 | 1.80 (1.33–2.45) | 43.2%, 7.04, 0.134 |

| Disease-free survival | ||||

| All | 7 | 859 | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) | 33.0%, 8.96, 0.176 |

| Univariate analysis | 4 | 377 | 0.86 (0.60–1.24) | 0.0%, 2.18, 0.536 |

| Multivariate analysis | 3 | 482 | 1.12 (1.04–1.21) | 59.4%, 4.92, 0.085 |

| Country | ||||

| Asian | 3 | 554 | 1.42 (0.61–3.31)a | 71.6%, 7.04, 0.030 |

| Western | 4 | 305 | 1.11 (1.03–1.20) | 0.0%, 1.56, 0.667 |

aThe result was based on the random effect model

Fig. 2.

Forest plot evaluating the combined HR between TGF-β and OS for all included studies

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis on TGF-β and OS. a Asian countries; b Western countries; c univariate analysis; d multivariate analysis

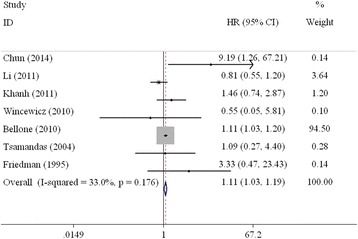

Meta-analysis of DFS

Seven studies on TGF-β and DFS in CRC patients undergoing surgery were included in the meta-analysis [16, 17, 22, 25–28]. The combined HR of the 7 studies that evaluated the relationship of the high expression of TGF-β to DFS was 1.11 (95% CI: 1.03–1.19, Table 3, Fig. 4), which suggests that high expression of TGF-β is a significant prognostic factor for CRC patients.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot evaluating the combined HR between TGF-β and DFS for all included studies

When the subgroups were analysed based on country, the combined HRs of the Asian and Western studies were 1.42 (95% CI: 0.61–3.31) and 1.11 (95% CI: 1.03–1.20), respectively (Fig. 5). The combined HR of the studies based on multivariate analysis was 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04–1.21; Fig. 5). However, statistical significance was not observed with respect to the association of TGF-β overexpression and DFS (HR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.60–1.24; Fig. 5) according to the univariate analysis.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis on TGF-β and DFS. a Asian countries; b Western countries; c univariate analysis; d multivariate analysis)

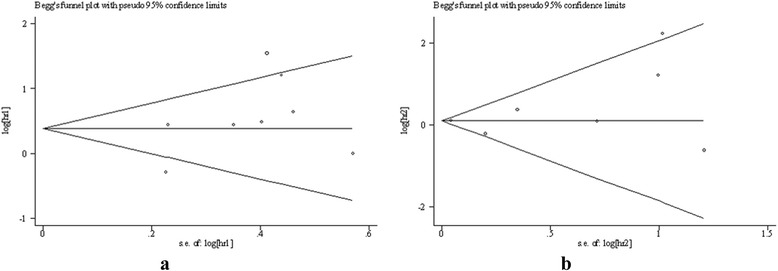

The Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were performed to evaluate the publication bias of the included studies (Fig. 6). Eight studies that investigated the effect of high expression of TGF-β on OS yielded a slope of −0.51 (95% CI: -1.96–0.94) with no significant difference (P = 0.423). Seven studies that investigated the effect of high expression of TGF-β on DFS yielded a slope of 0.08 (95% CI: -0.07–0.23) with no significant difference (P = 0.231). These results indicate the absence of publication bias in the included studies.

Fig. 6.

Funnel plot for the included studies. a OS; b DFS

Discussion

High expression of TGF-β in primary CRC is associated with advanced stages of the disease, a greater likelihood of recurrence and decreased survival [15, 28]. TGF-β stimulates proliferation and invasion in advanced stages of CRC and leads to distant metastasis [29]. Many studies have been conducted to assess the prognostic value of TGF-β in patients with CRC, but the conclusions have been inconclusive.

Our analysis showed that high expression of TGF-β was a prognostic indicator in CRC patients undergoing surgery. With respect to OS, the mortality rate of patients with a high expression of TGF-β was 1.68 times that of patients with a low expression. With respect to DFS, the mortality rate of patients with a high expression of TGF-β was 1.11 times that of patients with a low expression. Our results were consistent with those of studies of other cancers. The results of the meta-analysis conducted by Yang demonstrated that the high expression of TGF-β was strongly associated with the 3-year survival rate in patients with glioma [30]. Similar results were also found in patients with gastric cancer [31], hepatocellular carcinoma [32], renal cancer [33], breast cancer [34], and oesophageal cancer [35].

Determination of TGF-β expression independently provided valuable prognostic information in relation to two targeting pathways in patients with CRC. (1) One piece of information was related to the following signalling pathway molecules: matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and TGF-β. TGF-β acted as a tumour promoter in advanced stages of CRC, which potentially led to increased expression of MMP-2 and COX-2 [36, 37]. Coordinated, increased expression of COX-2, TGF-β and VEGF have been associated with increased angiogenesis, which in turn has been described to be a prerequisite for tumour growth [24, 38]. The meta-analysis showed that high expression levels of MMP-2, COX-2 and VEGF were associated with decreased survival time for CRC patients [39–41]. (2) Another piece of information involved the Smad4 and VEGF-C signalling pathway. Upon stimulation by TGF-β1, Smad2/Smad3 is phosphorylated by activated TGF-β receptors and forms a complex with Smad4. Smad4 translocates into the nucleus, where it affects transcription of the VEGF-C gene [25]. The meta-analysis demonstrated that high expression of VEGF-C was associated with decreased OS of patients with CRC [42].

TGF-β had a stronger association with OS and DFS in CRC patients undergoing surgery in Western countries than in Asian countries. The results suggested that CRC patients in Western countries who have overexpression of TGF-β are at a higher risk of death than those in Asian countries. With respect to DFS, the HRs among Asian countries were significantly different, whereas those among Western countries were not. This discrepancy may be related to heterogeneity and different disease characteristics in the Asian studies. (1) Heterogeneity was present among the Asian studies for DFS, and the P values were less than 0.05. For example, the HR of the study by Chun was 9.19 [22], but the HR for the study by Li was 0.81 [25]. (2) Different disease characteristics were also observed in the Asian studies. Two Asian studies involved CRC [21, 26], one involved rectal cancer [22], and one involved colon cancer [25]. One study enrolled CRC patients with stage III disease (AJCC) only [22]. Three other studies enrolled CRC patients with all stages of the disease [21, 25, 26]. When using disease (colorectal, rectal, and colon) as a grouping factor, the effects of TGF-β on prognosis were inconsistent. The HR of TGF-β in colorectal cancer was much higher than that of colon cancer.

Subgroup analysis was also performed based on the analytical method (univariate analysis, multivariate analysis). The HR of TGF-β in the multivariate analysis (2.37 for OS, 1.12 for DFS) was higher than that in the univariate analysis (1.13 for OS, 0.86 for DFS). If the variable was not significantly different in the univariate analysis, the variable was not entered into the Cox proportional hazards model (multivariate analysis). To understand the independent effect of TGF-β expression on prognosis of patients with CRC, multivariate analysis should be used to control the effects of other possible risk factors (e.g., gender, tumour grade, TNM staging system). The effect of the high expression of TGF-β on prognosis based on the univariate analysis was confounded because prognosis was affected by other factors.

Several limitations should be considered. (1) The method of therapy greatly affected the survival time of CRC patients. Although the use of chemotherapy or radiotherapy differed substantially among the included studies, all the included CRC patients were treated with surgery. Thus, the confounding effects of different therapeutic modalities would not be substantial. (2) The second limitation was the heterogeneity of the eligible studies. The results of subgroup analyses suggested that heterogeneity may have been partly due to the following variables: diversity of the disease and the countries where the studies were conducted. Other variables, such as follow-up time and the non-standardised methodologies for the assessment of TGF-β, among others, may be related to the heterogeneity. However, these subgroup analyses were not conducted. (3) The study conducted by Langenskiöld was excluded due to its great impact on the combined HR [23]. If the study was included in the analysis, it would have accounted for 99% of the weight due to its small standard error for HR (0.005). (4) TGF-β1 was not assessed in all the included studies. Two studies reported that they included the TGF-β gene, but it was unclear whether the gene was TGF-β1 [13, 24].

Conclusions

This meta-analysis provides evidence that high expression of TGF-β is significantly associated with worse OS and DFS in CRC patients who undergo surgery. TGF-β could be used as a prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer. Subgroup analysis indicates that high expression of TGF-β is associated with cancer progression in CRC patients from Western countries. However, high expression of TGF-β was not associated with cancer progression in Asian patients with CRC due to the high heterogeneity of the included studies. These results can guide postoperative treatment of CRC patients, especially the application of chemotherapy in CRC patients from Western countries.

Additional files

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. (DOC 66 kb)

The search strategy. (DOC 27 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine for their funds.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81,403,296, 81,373,786), the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Guangdong Province Colleges and Universities (YQ2015041), the Young Talents Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (QNYC20140101), and the Torch Plan of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (XH20140105). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the findings in this study are included within the manuscript and the two Additional files.

Authors’ contributions

XLC the designed the study, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. ZQC participated in study selection, extracted the data, and helped to write the manuscript. SLZ participated in study selection and extracted the data. TWL and YW performed the statistical analyses and interpreted the results. YSS, XJX and YH contributed to the discussion. LL participated in the study design and modified the manuscript. FBL participated in the study design and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- DFS

disease-free survival

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HRs

hazard ratios

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MMP-2

matrix metalloproteinase-2

- OS

overall survival

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RFS

relapse-free survival

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-beta

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Contributor Information

Xin-lin Chen, Email: chenxlsums@126.com.

Zhuo-qun Chen, Email: 546747905@qq.com.

Shui-lian Zhu, Email: 875461439@qq.com.

Tian-wen Liu, Email: liutianwen100@163.com.

Yi Wen, Email: 421491922@qq.com.

Yi-sheng Su, Email: drsysh@163.com.

Xu-jie Xi, Email: xixujie@126.com.

Yue Hu, Email: 2282683689@qq.com.

Lei Lian, Email: sabiston@126.com.

Feng-bin Liu, Email: liufb163@163.com.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1490–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erstad DJ, Tumusiime G, Cusack JC., Jr Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in colorectal cancer: implications for the clinical surgeon. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(11):3433–3450. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4706-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ku GY, Haaland BA, de Lima LG, Jr. Cetuximab in the first-line treatment of K-ras wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: the choice and schedule of fluoropyrimidine matters. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;70(2):231–238. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1898-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marien KM, Croons V, Martinet W, De Loof H, Ung C, Waelput W, Scherer SJ, Kockx MM, De Meyer GR. Predictive tissue biomarkers for bevacizumab-containing therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: an update. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15(3):399–414. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.993972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanz-Garcia E, Grasselli J, Argiles G, Elez ME, Tabernero J. Current and advancing treatments for metastatic colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16(1):93–110. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2016.1108405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thapa N, Lee BH, Kim IS. TGFBIp/betaig-h3 protein: a versatile matrix molecule induced by TGF-beta. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(12):2183–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulubova M, Manolova I, Ananiev J, Julianov A, Yovchev Y, Peeva K. Role of TGF-beta1, its receptor TGFbetaRII, and Smad proteins in the progression of colorectal cancer. Int J Color Dis. 2010;25(5):591–599. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin RL, Zhao LJ. Mechanistic basis and clinical relevance of the role of transforming growth factor-beta in cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12(4):385–393. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachman KE, Park BH. Duel nature of TGF-beta signaling: tumor suppressor vs. tumor promoter. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(1):49–54. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000143682.45316.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampropoulos P, Zizi-Sermpetzoglou A, Rizos S, Kostakis A, Nikiteas N, Papavassiliou AG. Prognostic significance of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) signaling axis molecules and E-cadherin in colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2012;33(4):1005–1014. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yashiro M, Hirakawa K, Boland CR. Mutations in TGFbeta-RII and BAX mediate tumor progression in the later stages of colorectal cancer with microsatellite instability. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:303. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robson H, Anderson E, James RD, Schofield PF. Transforming growth factor beta 1 expression in human colorectal tumours: an independent prognostic marker in a subgroup of poor prognosis patients. Br J Cancer. 1996;74(5):753–758. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsamandas AC, Kardamakis D, Ravazoula P, Zolota V, Salakou S, Tepetes K, Kalogeropoulou C, Tsota I, Kourelis T, Makatsoris T, et al. The potential role of TGFbeta1, TGFbeta2 and TGFbeta3 protein expression in colorectal carcinomas. Correlation with classic histopathologic factors and patient survival. Strahlenther Onkol. 2004;180(4):201–208. doi: 10.1007/s00066-004-1149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wincewicz A, Koda M, Sulkowski S, Kanczuga-Koda L, Sulkowska M. Comparison of beta-catenin with TGF-beta1, HIF-1alpha and patients' disease-free survival in human colorectal cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2010;16(3):311–318. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu J, Chen X, Liao Z, He C, Hu X. TGFBI protein high expression predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(1):702–710. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chun HK, Jung KU, Choi YL, Hong HK, Kim SH, Yun SH, Kim HC, Lee WY, Cho YB. Low expression of transforming growth factor beta-1 in cancer tissue predicts a poor prognosis for patients with stage III rectal cancers. Oncology. 2014;86(3):159–169. doi: 10.1159/000358064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langenskiöld M, Ivarsson ML, Holmdahl L, Falk P, Kåbjörn-Gustafsson C, Angenete E. Intestinal mucosal MMP-1 -a prognostic factor in colon cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(5):563–569. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.708939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhlmann ME, Georgieva M, Sill M, Linnemann U, Berger MR. Prognostic value of tumor progression-related gene expression in colorectal cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138(10):1631–1640. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1238-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Liu B, Xiao J, Yuan Y, Ma J, Zhang Y. Roles of VEGF-C and Smad4 in the lymphangiogenesis, lymphatic metastasis, and prognosis in colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(11):2001–2010. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanh do T, Mekata E, Mukaisho K, Sugihara H, Shimizu T, Shiomi H, Murata S, Naka S, Yamamoto H, Endo Y, et al. Prognostic role of CD10+ myeloid cells in association with tumor budding at the invasion front of colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(9):1724–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellone G, Gramigni C, Vizio B, Mauri FA, Prati A, Solerio D, Dughera L, Ruffini E, Gasparri G, Camandona M. Abnormal expression of Endoglin and its receptor complex (TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta receptor II) as early angiogenic switch indicator in premalignant lesions of the colon mucosa. Int J Oncol. 2010;37(5):1153–1165. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman E, Gold LI, Klimstra D, Zeng ZS, Winawer S, Cohen A. High levels of transforming growth factor beta 1 correlate with disease progression in human colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1995;4(5):549–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y, Pasche B: TGF-beta signaling alterations and susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Hum Mol Genet 2007, 16 Spec No 1 R14-R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Yang X, Lv S, Zhou X, Liu Y, Li D, Shi R, Kang H, Zhang J, Xu Z. The clinical implications of transforming growth factor Beta in pathological grade and prognosis of Glioma patients: a meta-analysis. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;52(1):270–276. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8872-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tas F, Yasasever CT, Karabulut S, Tastekin D, Duranyildiz D. Serum transforming growth factor-beta1 levels may have predictive and prognostic roles in patients with gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(3):2097–2103. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Liu T, Tang W, Deng B, Chen Y, Zhu J, Shen X. Hepatocellular carcinoma cells induce regulatory T cells and lead to poor prognosis via production of transforming growth factor-beta1. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38(1):306–318. doi: 10.1159/000438631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lebdai S, Verhoest G, Parikh H, Jacquet SF, Bensalah K, Chautard D, Rioux Leclercq N, Azzouzi AR, Bigot P. Identification and validation of TGFBI as a promising prognosis marker of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33(2):69.e11–69.e68. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahhnassy A, Mohanad M, Shaarawy S, Ismail MF, El-Bastawisy A, Ashmawy AM, Zekri AR. Transforming growth factor-beta, insulin-like growth factor I/insulin-like growth factor I receptor and vascular endothelial growth factor-a: prognostic and predictive markers in triple-negative and non-triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(1):851–864. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozawa D, Yokobori T, Sohda M, Sakai M, Hara K, Honjo H, Kato H, Miyazaki T, Kuwano H. TGFBI expression in cancer Stromal cells is associated with poor prognosis and Hematogenous recurrence in esophageal Squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(1):282–289. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massague J. TGFbeta in cancer. Cell. 2008;134(2):215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neil JR, Johnson KM, Nemenoff RA, Schiemann WP. Cox-2 inactivates Smad signaling and enhances EMT stimulated by TGF-beta through a PGE2-dependent mechanisms. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(11):2227–2235. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fosslien E. Review: molecular pathology of cyclooxygenase-2 in cancer-induced angiogenesis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2001;31(4):325–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi M, Yu B, Gao H, Mu J, Ji C. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 overexpression and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(1):617–623. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng L, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Mou H, Zhao Q: Prognostic significance of COX-2 immunohistochemical expression in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of the literature. PLoS One 2013, 8(3):e58891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Des Guetz G, Uzzan B, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Morere JF, Benamouzig R, Breau JL, Perret GY. Microvessel density and VEGF expression are prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. Meta-analysis of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(12):1823–1832. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zong S, Li H, Shi Q, Liu S, Li W, Hou F. Prognostic significance of VEGF-C immunohistochemical expression in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;458:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. (DOC 66 kb)

The search strategy. (DOC 27 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings in this study are included within the manuscript and the two Additional files.