Abstract

Background

The long-term clinical outcomes of antiviral therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis C are uncertain in terms of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related morbidity and mortality according to the response to antiviral therapy. This study aimed to assess the impact of antiviral treatment on the development of HCC and mortality in patients with chronic HCV infection.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted for studies that evaluated the antiviral efficacy for patients with chronic hepatitis C or assessed the development of HCC or mortality between SVR (sustained virologic response) and non-SVR patients. The methodological quality of the enrolled publications was evaluated using Risk of Bias table or Newcastle-Ottawa scale. Random-effect model meta-analyses and meta-regression were performed. Publication bias was assessed.

Results

In total, 59 studies (4 RCTs, 15 prospective and 40 retrospective cohort studies) were included. Antiviral treatment was associated with reduced development of HCC (vs. no treatment; OR 0.392, 95% CI 0.275–0.557), and this effect was intensified when SVR was achieved (vs. no SVR, OR: 0.203, 95% CI 0.164–0.251). Antiviral treatment was associated with lower all-cause mortality (vs. no treatment; OR 0.380, 95% CI 0.295–0.489) and liver-specific mortality (OR 0.363, 95% CI 0.260–0.508). This rate was also intensified when SVR was achieved [all-cause mortality (vs. no SVR, OR 0.255, 95% CI 0.199–0.326), liver-specific mortality (OR 0.126, 95% CI 0.094–0.169)]. Sensitivity analyses revealed robust results, and a small study effect was minimal.

Conclusions

In patients with chronic hepatitis C, antiviral therapy can reduce the development of HCC and mortality, especially when SVR is achieved.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12876-017-0606-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antiviral therapy, Chronic hepatitis C, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Mortality, Sustained virologic response

Background

Antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C (CHC) aims to prevent hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related morbidity and mortality, including complications of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Treatment reduces the degree of necroinflammation of the liver and induces regression of hepatic fibrosis [1]. Although direct-acting antivirals have recently emerged as a promising therapy, conventional interferon (IFN) or pegylated IFN (PegIFN) with or without ribavirin (RBV) has been used as the standard treatment for curing HCV.

A sustained virologic response (SVR) is the surrogate indicator for eradicating HCV and is considered to be “cure” [2]. SVR24 or SVR12, which is the state of undetectable HCV RNA in a sensitive assay with a lower limit of detection <50 IU/mL at week 24 or 12 after the end of treatment are accepted as an endpoint of treatment [3].

The evolution of CHC is slow, and there is no specific symptom before progression to liver fibrosis. Due to delayed diagnosis of HCV-related chronic liver disease such as chronic hepatitis or liver fibrosis, it is difficult to start an anitviral treatment in the early stage of the disease. Previous study has demonstrated an achievement of SVR was associated with less risk for mortality (risk ratio 0.16) and development of HCC (risk ratio 0.37) [4]. However, the majority of studies assessed short-term prognosis and the long-term clinical outcomes of antiviral therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis C are uncertain in terms of HCV-related morbidity and mortality, including disease progression to advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, HCC, and liver-specific death, especially according to the response to antiviral therapy. Moreover, viral replication of HCV is not known to be directly related to HCC development [4].

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of antiviral treatment on the development of HCC and mortality in patients with CHC.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis fully adhered to the principle of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist.

Literature searching strategy

PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were searched using common keywords associated with chronic hepatitis C, HCC, or SVR (from inception to April 2016) by 2 independent evaluators (C.S.B. and Y.J.Y.). Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or Emtree keywords were selected for searching of electronic databases. The keywords included ‘hepatitis C’, ‘HCV’, ‘hepatocellular carcinoma’, ‘HCC’, ‘sustained virologic response’, ‘SVR’ and ‘mortality’. These keywords were combined for a searching strategy using Boolean operators. The abstracts of all identified studies were reviewed to exclude irrelevant articles. Full-text reviews were performed to determine whether the inclusion criteria were satisfied by the remaining studies and the bibliographies of relevant articles were reviewed to identify additional studies. Disagreements between the evaluators were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third evaluator (I.H.S.). The detailed searching strategy is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical data of included studies

| 1. PubMed |

| 1. Hepatitis C[Mesh] OR HCV 2. HCC OR “hepatocellular carcinoma” 3. SVR OR “sustained virologic response” 4. Mortality (#1 AND #2) OR (#1 AND #3) OR (#1 AND #4) - > removed duplicated articles |

| 2. Embase |

| 1. (hepatitis C or hcv).mp 2. (hcc or hepatocellular carcinoma).mp 3. (svr or sustained virologic reponse).mp 4. mortality After accumulation of (1 and 2), (1 and 3), and (1 and 4), and then removed duplicated articles |

| 3. Cochrane library |

| 1. Hepatitis C OR HCV 2. HCC OR “hepatocellular carcinoma” 3. SVR OR “sustained virologic response” 4. Mortality (#1 AND #2) OR (#1 AND #3) OR (#1 AND #4) - > removed duplicated articles |

Selection criteria

We included randomized or non-randomized studies that met the following criteria: 1. Study designed to evaluate the efficacy of antiviral treatment on the development of HCC or mortality in CHC patients and a control group, or in CHC patients with SVR and the no SVR group; 2. Publications on human subjects; 3. Full-text publication; and 4. English language. Studies that met the all of the inclusion criteria were sought and selected. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1. Incomplete data; 2. Review article; 3. Animal study; 4. Letter or case article; or 5. Abstract only publication. Studies meeting at least 1 of the exclusion criteria were excluded from this analysis.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the enrolled publications was assessed using the Risk of Bias table for randomized studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for non-randomized studies. The Risk of Bias was assessed as described in the Cochrane handbook by recording the method used to generate the randomization sequence, allocation concealment, determination of whether blinding was implemented for participants or staff, and evidence of selective reporting of the outcomes [5]. Review Manager version 5.3.3 (Revman for Windows 7, the Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to generate the Risk of Bias table. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale is categorized into three parameters: the selection of the study population, the comparability of the groups, and the ascertainment of the exposure or outcome. Each parameter consists of subcategorized questions: selection (n = 4), comparability (n = 1), and exposure or outcome (n = 3) [6, 7]. Stars that are awarded for each item serve as a quick visual assessment of the methodological quality of the studies. A study can be graded a maximum of 9 stars, which indicates the highest quality. Two of the evaluators (C.S.B. and Y.J.Y.) independently assessed the methodological quality of all studies, and any disagreements between the evaluators were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third evaluator (I.H.S.).

Primary and modifier-based analyses

The following questions were primary topic of this meta-analyses: In patients with CHC, 1. Does the antiviral treatment reduce the development of HCC? 2. Does the antiviral treatment reduce all-cause or 3. liver-specific mortality? 4. Does the achievement of SVR reduce the development of HCC? 5. Does the achievement of SVR reduce all-cause or 6. liver-specific mortality?

The analysis was performed as 6 distinct meta-analyses to answer the 6 questions described above. Two evaluators (C.S.B. and Y.J.Y.) independently used the same data fill-up form to collect the primary summary outcome and modifiers in each study. The outcome was the relative rate of the development of HCC or mortality between antiviral treatment and the control groups, or the SVR and no SVR groups. These ratios were extracted and evaluated by odds ratios (ORs). Sensitivity analyses, including cumulative and one study removed analyses were performed to confirm the robustness of the main analysis results. These analyses were calculated in the order of publication year or effect size to find whether the time trend exists or which study is more or less influential in the pooled estimate. We also performed a meta-ANOVA and meta-regression to identify the reason of heterogeneity based on the multiple modifiers identified during systematic review. These reasons include study format (randomized/prospective cohort/retrospective cohort study), nationality, histology (degree of liver fibrosis), follow-up duration, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, age, and the regimen of the treatment (IFN, IFN with RBV, PegIFN with or without RBV). The follow-up duration of each study was categorized as long-term (≥5 years) or short-term (<5 years).

Statistics

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 3, Biostat; Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J and Rothstein H. Englewood, NJ, USA) was used for this meta-analysis. We calculated the ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using 2 × 2 tables from the original articles to evaluate the efficacy of antiviral treatment between the treatment and control groups, or the SVR and no SVR groups whenever possible. Heterogeneity was determined using the I 2 test developed by Higgins, which measures the percentage of total variation across studies [8]. I 2 was calculated as follows: I 2 (%) = 100 × (Q-df)/Q, where Q is Cochrane’s heterogeneity statistic and df signifies the degree of freedom. Negative values for I 2 were set to zero, and an I 2 value over 50% was considered to be of substantial heterogeneity (range: 0–100%) [9]. Pooled-effect sizes with 95% CIs were calculated using a random effects model and the method of DerSimonian and Laird due to methodological heterogeneity [10]. These results were confirmed by the I 2 test. Significance was set at p = 0.05. Publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s funnel plot, Egger’s test of the intercept, Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test, and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method [11–15].

Results

Identification of relevant studies

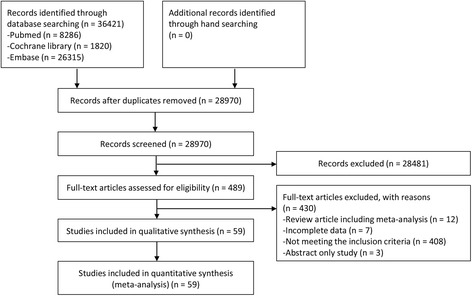

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of how relevant studies were identified. In total, 36,421 articles were identified by a search of 3 databases. In all, 7451 duplicate studies and an additional 28,481 studies were excluded during the initial screening through a review of the titles and abstracts. The full texts of the remaining 489 studies were then thoroughly reviewed. Among these studies, 431 articles were excluded from the final analysis. The reasons for study exclusion during the final review were as follows: review article (n = 12), incomplete data (n = 7), not meeting the inclusion criteria (n = 409), or abstract only study (n = 3). The remaining 58 studies [4 randomized controlled studies (RCTs), 15 prospective cohort, and 40 retrospective cohort studies] were included in the final analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for identification of relevant studies

Characteristics of included studies

In each study topic, about 13–35 studies were enrolled. In terms of the study format, RCTs, prospective and retrospective cohort studies were mixed. The number of Western population-based studies and the number of Asian population-based studies were evenly distributed. The age of enrolled patients ranged from 37 to 64 years (median). The follow-up duration ranged from 32 months (mean) to 11.5 years (median). Most of the studies used IFN-based regimens with or without RBV in topic 1, 2 and 3. However, a PegIFN-based regimen and IFN-based regimens were evenly distributed in topic 4, 5, and 6. Underlying histology of liver was variable, but some studies exclusively assessing liver cirrhosis patients were included. The detailed characteristics of the included studies are described in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Table 2.

Clinical data summary of all included studies

| Topic | Number of enrolled studies and population | Study format | Nationality | Age | Follow-up duration | Treatment regimen | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic 1 | 25 studies (9691 treated vs. 6010 control) | 3 RCTs 8 prospective cohort studies 14 retrospective cohort studies |

15 Western population-based studies 10 Asian population-based studies |

37 to 61 years (median) | 32 months to 10 years (mean) | IFN-based regimens with or without RBV, except 4 studies with a PegIFN-based regimen | 10 studies exclusively assessing LC patients) |

| Topic 2 | 17 studies (9868 treated vs. 4700 controls) | 1 RCT 5 prospective cohort studies 11 retrospective cohort studies |

8 Western population-based studies 9 Asian population-based studies |

37 to 61 years (median) | 55 months to 11.5 years (median) | IFN-based regimen with or without RBV, except 3 studies with a PegIFN-based regimen | 3 studies exclusively assessing LC patients |

| Topic 3 | 13 studies (8671 treated vs. 2831 controls) | 5 prospective cohort studies 8 retrospective cohort studies |

5 Western population-based studies 8 Asian population-based studies |

37 to 61 years (median) | 55 months to 11.5 years (median) | IFN-based regimen with or without RBV, except 2 studies with a PegIFN-based regimen | 4 studies exclusively assessing LC patients |

| Topic 4 | 35 studies (14756 patients with SVR vs. 12741 patients with no SVR) | 1 RCT 8 prospective cohort studies 26 retrospective cohort studies |

17 Western population-based studies 17 Asian population-based studies 1 Saudi Arabia and Egypt population-based study |

37 to 64 years (median) | 2.1 (median) to 10 years (mean) | 20 studies with PegIFN-based regimen 15 studies with IFN-based regimen |

9 studies exclusively assessing LC patients |

| Topic 5 | 22 studies (12440 patients with SVR vs. 18980 patients with no SVR) | 4 prospective cohort studies 18 retrospective cohort studies |

12 Western population-based studies 9 Asian population-based studies 1 Saudi Arabia and Egypt population-based study |

41.8 to 64 years (mean) | 2.1 to 11.5 years (median) | 11 studies with PegIFN-based regimen 11 studies with IFN-based regimen |

3 studies exclusively assessing LC patients |

| Topic 6 | 23 studies (5148 patients with SVR vs. 10356 patients with no SVR) | 7 prospective cohort studies 16 retrospective cohort studies |

14 Western population-based studies 9 Asian population-based studies |

41.8 to 64 (mean) | 2.1 to 11.5 years (median) | 12 studies with PegIFN-based regimen 11 studies with IFN-based regimen |

6 studies exclusively assessing LC patients |

RCT randomized controlled study, IFN interferon, PegIFN pegylated interferon, RBV ribavirin, LC liver cirrhosis, SVR sustained virologic response

Table 3.

Clinical data of included studies for the efficacy of antiviral treatment on the development of HCC in patients with CHC

| Study | Nationality | Age | Duration of follow up | Study format | Genotype | NOS | Treatment | HCC/Total treatment | HCC/Control | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mazella G et al. (1996) [23] | Italy | Tx: 53, control: 54 (mean) | mean 32 months | P | unknown | 7 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 5/193 | 9/92 | Child A LC |

| Bruno S et al.(1997) [24] | Italy | Tx 56, control: 59 (mean) | median 68 months | P | 62% type 1b | 7 | IFN-α | 6/83 | 16/80 | LC (mainly Child A) |

| Fattovich G et al. (1997) [25] | Italy | Tx: 53, control: 57 (mean) | mean 60 months | R | unknown | 8 | IFN-α | 7/193 | 16/136 | LC |

| Serfaty L et al. (1998) [26] | France | Tx: 55, control: 56 (mean) | median 40 months | P | 48% 1b | 7 | IFN-α | 2/59 | 9/44 | Knodell 10 (mean) |

| Benvegnù L et al.(1998) [27] | Italy | Tx: 56.7, control: 59.5 (mean) | mean 71.5 months | P | unknown | 8 | IFN | 4/75 | 20/77 | Child A LC |

| International Interferon-α Hepatocellular Carcinoma Study Group (1998) [28] | Italy and Argentina | 54 (median) | 36 months | R | unknown | 7 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 21/232 | 48/259 | unknown |

| Imai Y et al.(1998) [29] | Japan | unknown | Tx: 47.6, control: 46.8 (median) | R | unknown | 7 | IFN-α | 28/419 | 19/144 | F3,4: 37% in Tx, 53% in control |

| Yoshida H et al. (1999) [30] | Japan | Tx: 49.5, control: 53.6 (mean) | median 4.3 years | R | 70.3% type 1 | 7 | IFN-α or IFN-β or combination | 89/2400 | 59/490 | F3,4: 33.1% in Tx, 33.8% in control |

| Okanoue T et al. (1999) [31] | Japan | 42.6–57.6 (mean) | mean 39.5–67.1 months | R | unknown | 7 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 52/1148 | 22/55 | F3,4: 34% in Tx, F4: 100% in control |

| Valla DC et al. (1999) [32] | France | Tx: 57, control: 56 (mean) | mean 160 weeks | RCT | unknown | IFN-α | 5/47 | 9/52 | compensated LC | |

| Ikeda K et al. (2001) [33] | Japan | 57 (median) | median 7.6 years | R | unknown | 7 | IFN-α or IFN-β | 32/113 | 271/581 | LC |

| Gramenzi A et al. (2001) [34] | Italy | Tx: 57.9, control: 58.1 (mean) | median 55–58 months | P | unknown | 7 | IFN-α | 6/72 | 19/72 | LC (mainly Child A) |

| Nishiguchi S et al. (2001) [35] | Japan | Tx: 54.7, control: 57.3 (mean) | mean 8.2 years | RCT | 75.6% type 2 | IFN-α | 12/45 | 33/45 | unknown | |

| Testino G et al. (2002) [16] | Italy | Tx: 55.3, control: 56.8 (mean) | mean 95.4 months | R | 55% type 1b, 45% type 2 | 8 | IFN-α | 12/51 | 24/71 | Child A LC |

| Coverdale SA et al. (2004) [36] | Australia | Tx: 37, control: 38 (median) | median 9 years | P | 39.6% type 1 | 7 | IFN-α | 26/384 | 7/71 | Scheuer fibrosis score 2 |

| Azzaroli F et al. (2004) [37] | Italy | 55.1 (mean) | 5 years | RCT | 64.4% type 1b | IFN-α with RBV | 2/71 | 9/30 | LC | |

| Shiratori Y et al. (2005) [38] | Japan | Tx: 57, control: 61 (median) | median 6.8 years | P | 71.9% type 1b | 8 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 84/271 | 35/74 | unknown |

| Yu ML et al. (2006) [39] | Taiwan | Tx: 46.9, control: 43.6 (mean) | mean 5.18–5.15 years | R | 46.2% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV | 51/1057 | 54/562 | LC 15.6% in Tx, 12.1% in control |

| Sinn DH et al. (2008) [40] | Korea | 48.4–58.2 (mean) | median 55.2 months | R | 48.6% type 2 | 7 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 14/490 | 122/647 | F3,4: 49% in Tx, F4: 33% in control |

| Di Martino V et al. (2011) [41] | France | unknown | median 59 months | R | 57.9% type 1 | 7 | IFN with or without RBV, or PegIFN with RBV | 9/184 | 5/184 | 55.5% F2 or greater |

| Tateyama M et al. (2011) [42] | Japan | 57 (median) | mean 8.2 years | R | 72.1% type 1b | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 110/373 | 63/334 | F3,4: 34.1% |

| Maruoka D et al. (2012) [43] | Japan | 50.4–54 (mean) | mean 9.9 years | R | 73.6% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α/IFN-β with or without RBV | 85/577 | 35/144 | F3,4: 24.3% in Tx, F4: 43.1% in control |

| Cozen ML et al. (2013) [44] | US | 50.98 (mean) | mean 10 years | R | 68.7% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV | 11/159 | 9/199 | F3,4: 19% (30.2% in Tx, 10.1% in control) |

| Aleman S et al. (2013) [45] | Sweden | 51 (mean) | mean 5.3 years | R | 50% type 1 | 8 | PegIFN with RBV | 32/303 | 14/48 | LC |

| Cozen ML et al. (2016) [46] | US | 51.4 (mean) | mean 8.5 years | P | 71.6% type 1 or 4 | 8 | IFN-α with RBV | 43/692 | 84/1519 | LC 15.8% in Tx, 5.3% in control |

HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, CHC chronic hepatitis C, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa scale, Tx treatment group, R retrospective cohort study, P prospective cohort study, RCT randomized controlled study, IFN interferon, PegIFN pegylated interferon, RBV ribavirin, LC liver cirrhosis

Table 4.

Clinical data of included studies for the efficacy of antiviral treatment on all-cause and liver-specific mortality in patients with CHC

| Study | Nationality | Age | Duration of follow up | Study format | Genotype | NOS | Treatment | Death/Total treatment | Death/Control | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benvegnù L et al. (1998) [27] | Italy | Tx: 56.7, control: 59.5 (mean) | mean 71.5 months | P | unknown | 8 | IFN | a3/75 | a15/77 | Child A LC |

| Ikeda K et al. (2001) [33] | Japan | 57 (median) | median 7.6 years | R | unknown | 7 | IFN-α or IFN-β | 20/113 a12/113 | 266/581 a124/581 | LC |

| Gramenzi A et al. (2001) [34] | Italy | Tx: 57.9, control: 58.1 (mean) | median 55–58 months | P | unknown | 7 | IFN-α | a7/72 | 9/72 a8/72 | LC (mainly Child A) |

| Nishiguchi S et al. (2001) [35] | Japan | Tx: 54.7, control: 57.3 (mean) | mean 8.2 years | RCT | 75.6% type 2 | IFN-α | 5/45 | 26/45 | unknown | |

| Testino G et al. (2002) [16] | Italy | Tx: 55.3, control: 56.8 (mean) | mean 95.4 months | R | 55% type 1b, 45% type 2 | 8 | IFN-α | 1/51 | 9/71 | Child A LC |

| Yosida H et al. (2002) [47] | Japan | Tx: 49.5, control: 54.6 (mean) | mean 5.4 years | R | unknown | 8 | IFN-α or IFN-β | 56/2430 a35/2430 | 30/459 a23/459 | F3,4: 32.2% in Tx, 31.6% in control, 26.3% in SVR, 35.2% in no SVR |

| Imazeki F et al. (2003) [48] | Japan | Tx: 49.2, control: 53.1 (mean) | mean 8.2 years | R | 73.9% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α or IFN-β | 33/355 a19/355 | 15/104 a12/104 | F3,4: 26.7% in Tx, 29.8% in control, |

| Coverdale SA et al. (2004) [36] | Australia | Tx: 37, control: 38 (median) | median 9 years | P | 39.6% type 1 | 7 | IFN-α | a36/384 | a12/71 | Scheuer fibrosis score 2 |

| Kasahara A et al. (2004) [17] | Japan | Tx: 53, control: 54 (median) | mean 6 years | R | unknown | 8 | IFN | 101/2698 a69/2698 | 52/256 a42/256 | F3,4: 38.7% in Tx, 48% in control, 28.6% in SVR, 43% in no SVR |

| Shiratori Y et al. (2005) [38] | Japan | Tx: 57, control: 61 (median) | median 6.8 years | P | 71.9% type 1b | 8 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 45/271 a32/271 | 24/74 a19/74 | unknown |

| Yu ML et al. (2006) [39] | Taiwan | Tx: 46.9, control: 43.6 (mean) | mean 5.18–5.15 years | R | 46.2% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV | 16/1057 a14/1057 | 12/562 a10/562 | LC 15.6% in Tx, 12.1% in control |

| Di Martino V et al. (2011) [41] | France | unknown | median 59 months | R | 57.9% type 1 | 7 | IFN with or without RBV, or PegIFN with RBV | 9/184 a5/184 | 20/194 a4/184 | 55.5% F2 or greater |

| Yamasaki K et al. (2012) [49] | Japan | 60.9 (mean) | median 11.5 years | P | 59.9% type 1b | 7 | IFN-α or β or lymphoblastoid with or without RBV | 25/152 a6/152 | 90/199 a32/199 | unknown |

| Maruoka D et al. (2012) [43] | Japan | 50.4–54 (mean) | mean 9.9 years | R | 73.6% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α/IFN-β with or without RBV | 84/577 a52/577 | 37/144 a30/144 | F3,4: 24.3% in Tx, F4: 43.1% in control |

| Cozen ML et al. (2013) [44] | US | 50.98 (mean) | mean 10 years | R | 68.7% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV | 31/159 | 47/199 | F3,4: 19% (30.2% in Tx, 10.1% in control) |

| Aleman S et al. (2013) [45] | Sweden | 51 (mean) | mean 5.3 years | R | 50% type 1 | 8 | PegIFN with RBV | 59/303 a39/303 | 18/48 a16/48 | LC |

| Kutala BK et al. (2015) [50] | France | 50 (median) | median 5.5 years | R | 55.7% type 1 | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 30/325 | 19/102 | F3,4: 100% |

| Cozen ML et al. (2016) [46] | US | 51.4 (mean) | mean 8.5 years | P | 71.6% type 1 or 4 | 8 | IFN-α with RBV | 112/692 | 488/1519 | LC 15.8% in Tx, 5.3% in control |

a: Liver-specific death, CHC chronic hepatitis C, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa scale, Tx treatment group, R retrospective cohort study, P prospective cohort study, RCT randomized controlled study, IFN interferon, PegIFN pegylated interferon, RBV ribavirin, LC liver cirrhosis, SVR sustained virologic response

Table 5.

Clinical data of included studies for the efficacy of SVR on the development of HCC in patients with CHC

| Study | Nationality | Age | Duration of follow up | Study format | Genotype | NOS | Treatment | HCC/Total SVR | HCC/No SVR | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nishiguchi S et al. (1995) [51] | Japan | Tx: 54.7, control: 57.3 (mean) | 2–7 years | RCT | 75.6% type 2 | IFN-α | 0/7 | 2/38 | HAI 11.7 in Tx, 11.8 in control (mean) | |

| Tanaka K et al. (1998) [52] | Japan | SVR: 47.7, no SVR: 51 (mean) | about 40 months | P | unknown | 7 | lymphoblastoid IFN | 0/8 | 10/47 | LC |

| Yoshida H et al. (1999) [30] | Japan | Tx: 49.5, control: 53.6 (mean) | median 4.3 years | R | 70.3% type 1 | 7 | IFN-α or IFN-β or combination | 10/789 | 79/1611 | F3,4: 33.1% in Tx, 33.8% in control |

| Testino G et al. (2002) [16] | Italy | Tx: 55.3, control: 56.8 (mean) | mean 95.4 months | R | 55% type 1b, 45% type 2 | 8 | IFN-α | 3/11 | 12/40 | Child A LC |

| Okanoue T et al. (2002) [53] | Japan | Tx: 50.4, control: 58.1 (mean) | Mean 5.6 years | R | unknown | 7 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 4/426 | 110/994 | F3,4: 20.9% in SVR, 34.4% in control |

| Coverdale SA et al. (2004) [36] | Australia | Tx: 37, control: 38 (median) | median 9 years | P | 39.6% type 1 | 7 | IFN-α | 1/50 | 25/334 | Scheuer fibrosis score 2 |

| Shiratori Y et al. (2005) [38] | Japan | Tx: 57, control: 61 (median) | median 6.8 years | P | 71.9% type 1b | 8 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 11/64 | 73/207 | unknown |

| Yu ML et al. (2006) [39] | Taiwan | Tx: 46.9, control: 43.6 (mean) | mean 5.18–5.15 years | R | 46.2% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV | 12/715 | 39/342 | LC 15.6% in Tx, 12.1% in control |

| Pradat P et al. (2007) [54] | Europe | 45–47 (mean) | 5–7 years | P | 49.2% type 1 | 6 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 0/91 | 17/266 | unknown |

| Braks RE et al. (2007) [55] | France | 54.1 (mean) | mean 7.7 years | R | 61.1% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV, or PegIFN with RBV | 1/37 | 24/76 | Child A LC |

| Bruno S et al. (2007) [56] | Italy | 54.7 (mean) | Mean 96.1 months | R | 71.8% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α | 7/124 | 122/759 | Child A LC |

| Hasegawa E et al. (2007) [57] | Japan | 56 (median) | median 4.6 years | R | 65% 2a | 7 | IFN-α,β/lymphoblastoid with or without RBV | 3/48 | 16/57 | LC |

| Veldt BJ et al. (2007) [58] | Europe and Canada | 48 (median) | median 2.1 years | R | 59% type 1 | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 3/142 | 32/337 | Ishak 4–6 |

| Floreani A et al. (2008) [59] | Italy | 44.5–55.7 (mean) | mean 23.4–25.2 months | R | 41.3% type 1 | 7 | PegIFN with RBV | 0/40 | 5/38 | unknown |

| Sinn DH et al. (2008) [40] | Korea | 48.4–58.2 (mean) | median 55.2 months | R | 48.6% type 2 | 7 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 4/296 | 10/194 | F3,4: 49% in Tx, F4: 33% in control |

| Kurokawa M et al. (2009) [60] | Japan | 55.8 (mean) | median 36.5 months | R | 72.9% type 1 | 7 | IFN-α with RBV | 4/139 | 21/264 | F3,4: 31.3% |

| Asahina Y et al. (2010) [61] | Japan | 55.4 (mean) | mean 7.5 years | R | 69.6% type 1b | 8 | IFN-α,β with or without RBV, or PegIFN with RBV | 22/686 | 149/1356 | F3,4: 25.2% |

| Kawamura Y et al. (2010) [62] | Japan | 50 (median) | median 6.7 years | R | unknown | 8 | IFN-α,β with or without RBV | 12/1081 | 61/977 | F1,2: 93.1% |

| Cardoso AC et al. (2010) [63] | France | 55 (mean) | median 3.5 years | R | 60% type 1 | 7 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 6/103 | 40/204 | F3,4: 100% |

| Morgan TR et al. (2010) [64] | US | 48.6–49.6 (mean) | median 79–96 months | P | 87.2% type 1 | 8 | PegIFN with or without RBV | 2/140 | 33/386 | F3,4: 100% |

| Di Martino V et al. (2011) [41] | France | unknown | median 59 months | R | 57.9% type 1 | 7 | IFN with or without RBV, or PegIFN with RBV | 1/59 | 8/125 | 55.5% F2 or greater |

| Velosa J et al. (2011) [65] | Portugal | 51.7 (mean) | mean 6.4 years | R | 61% type 1 | 7 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 1/39 | 20/91 | compensated LC |

| Iacobellis A et al. (2011) [66] | Italy | 59–62 (mean) | mean 51 months | P | 57.3% type 1 | 7 | PegIFN with RBV | 5/24 | 11/51 | decompensated LC |

| Hung CH et al. (2011) [67] | Taiwan | 53 (median) | median 4.3 years | R | 49% type 1 | 7 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 33/1027 | 54/443 | unknown |

| Takahashi H et al. (2011) [68] | Japan | 55.4 (mean) | Mean 52 months | R | 74.9% type 1b | 7 | IFN-α,β/PegIFN with RBV | 1/89 | 12/114 | F3,4: 23.2% |

| Backus LI et al. (2011) [69] | US | 51–53 (mean) | median 3.8 years | R | 72.1% type 1 | 6 | PegIFN with RBV | 223/7434 | 283/1440 | 13% LC |

| Tateyama M et al. (2011) [42] | Japan | 57 (median) | mean 8.2 years | R | 72.1% type 1b | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 3/139 | 44/234 | F3,4: 34.1% |

| Osaki Y et al. (2012) [70] | Japan | 59 (median) | median 4.1 years | R | 59.9% type 1 | 7 | IFN/PegIFN with RBV | 1/185 | 22/197 | unknown |

| van der Meer AJ et al. (2012) [71] | Europe and Canada | 48 (mean) | median 8.4 years | R | 68% type 1 | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 7/125 | 76/405 | Ishak 4–6 |

| Maruoka D et al. (2012) [43] | Japan | 50.4–54 (mean) | mean 9.9 years | R | 73.6% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α/IFN-β with or without RBV | 5/221 | 80/356 | F3,4: 24.3% in Tx, F4: 43.1% in control |

| Cozen ML et al. (2013) [44] | US | 50.98 (mean) | mean 10 years | R | 68.7% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV | 2/69 | 9/90 | F3,4: 19% (30.2% in Tx, 10.1% in control) |

| Alfaleh FZ et al. (2013) [72] | Saudi Arabia, Egypt | 48 (mean) | mean 63.8 months | P | 30.6% type 4 | 8 | PegIFN with or without RBV | 0/62 | 4/95 | F3,4: 24.6% (27.1% in SVR, 31.1% in no SVR) |

| Aleman S et al. (2013) [45] | Sweden | 51 (mean) | mean 5.3 years | R | 50% type 1 | 8 | PegIFN with RBV | 6/110 | 26/193 | LC |

| Di Marco V et al. (2016) [73] | Italy | 58 (mean) | median 7.6 years | P | 83.4% type 1 | 8 | PegIFN with RBV | 7/108 | 92/336 | compensated LC |

| Ikezaki H et al. (2016) [74] | Japan | 60–64 (median) | median 2.8 years | R | 52.7% in type 1 | 7 | IFN- β with RBV | 2/68 | 7/44 | F3,4: 30.9% in SVR, 72.7% in no SVR |

SVR sustained virologic response, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, CHC chronic hepatitis C, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa scale, Tx treatment group, R retrospective cohort study, P prospective cohort study, RCT randomized controlled study, IFN interferon, PegIFN pegylated interferon, RBV ribavirin, LC liver cirrhosis

Table 6.

Clinical data of included studies for the efficacy of SVR on all-cause and liver-specific mortality in patients with CHC

| Study | Nationality | Age | Duration of follow up | Study format | Genotype | NOS | Treatment | Death/Total SVR | Death/No SVR | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yosida H et al. (2002) [47] | Japan | Tx: 49.5, control: 54.6 (mean) | mean 5.4 years | R | unknown | 8 | IFN-α or IFN-β | a7/817 | a49/1613 | F3,4: 32.2% in Tx, 31.6% in control, 26.3% in SVR, 35.2% in no SVR |

| Okanoue T et al. (2002) [53] | Japan | Tx: 50.4, control: 58.1 (mean) | Mean 5.6 years | R | unknown | 7 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 2/426 a0/426 | 47/994 a34/994 | F3,4: 20.9% in SVR, 34.4% in control |

| Imazeki F et al. (2003) [48] | Japan | Tx: 49.2, control: 53.1 (mean) | mean 8.2 years | R | 73.9% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α or IFN-β | 4/116 a1/116 | 29/239 a18/239 | F3,4: 26.7% in Tx, 29.8% in control |

| Coverdale SA et al. (2004) [36] | Australia | Tx: 37, control: 38 (median) | median 9 years | P | 39.6% type 1 | 7 | IFN-α | a1/50 | a35/334 | Scheuer fibrosis score 2 |

| Kasahara A et al. (2004) [17] | Japan | Tx: 53, control: 54 (median) | mean 6 years | R | unknown | 8 | IFN | 7/738 a1/738 | 94/1930 a68/1930 | F3,4: 38.7% in Tx, 48% in control, 28.6% in SVR, 43% in no SVR |

| Shiratori Y et al. (2005) [38] | Japan | Tx: 57, control: 61 (median) | median 6.8 years | P | 71.9% type 1b | 8 | IFN-α or lymphoblastoid | 1/64 a0/64 | 44/207 a32/207 | unknown |

| Yu ML et al. (2006) [39] | Taiwan | Tx: 46.9, control: 43.6 (mean) | mean 5.18–5.15 years | R | 46.2% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV | 4/715 a3/715 | 12/342 a11/342 | LC 15.6% in Tx, 12.1% in control |

| Arase Y et al. (2007) [75] | Japan | SVR: 63, no SVR: 64 (mean) | mean 7.4 years | R | 60.4% type 1b | 8 | IFN-α/β with or without RBV | 9/140 a2/140 | 44/360 a32/360 | F3,4: 14.5 in SVR, 27.5 in no SVR |

| Bruno S et al. (2007) [56] | Italy | 54.7 (mean) | Mean 96.1 months | R | 71.8% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α | 6/124 a2/120 | 114/759 a83/728 | Child A LC |

| Veldt BJ et al. (2007) [58] | Europe and Canada | 48 (median) | median 2.1 years | R | 59% type 1 | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 2/142 a1/142 | 24/337 a19/337 | Ishak 4–6 |

| Cardoso AC et al. (2010) [63] | France | 55 (mean) | median 3.5 years | R | 60% type 1 | 7 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | a3/103 | a18/204 | F3,4: 100% |

| Morgan TR et al. (2010) [64] | US | 48.6–49.6 (mean) | median 79–96 months | P | 87.2% type 1 | 8 | PegIFN with or without RBV | a1/140 | a23/386 | F3,4: 100% |

| Innes HA et al. (2011) [76] | UK | 41.8 (mean) | mean 5.3 years | R | 35.6% type 1 | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 13/560 a5/560 | 75/655 a50/655 | 85.8% no LC |

| Di Martino V et al. (2011) [41] | France | unknown | median 59 months | R | 57.9% type 1 | 7 | IFN with or without RBV, or PegIFN with RBV | 0/59 a0/59 | 9/125 a5/125 | 55.5% F2 or greater |

| Velosa J et al. (2011) [65] | Portugal | 51.7 (mean) | mean 6.4 years | R | 61% type 1 | 7 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | a0/39 | a15/91 | compensated LC |

| Iacobellis A et al. (2011) [66] | Italy | 59–62 (mean) | mean 51 months | P | 57.3% type 1 | 7 | PegIFN with RBV | a2/24 | a23/51 | decompensated LC |

| Backus LI et al. (2011) [69] | US | 51–53 (mean) | median 3.8 years | R | 72.1% type 1 | 6 | PegIFN with RBV | 525/7434 | 1440/9430 | 13% LC |

| Yamasaki K et al. (2012) [49] | Japan | 60.9 (mean) | median 11.5 years | P | 59.9% type 1b | 7 | IFN-α or β or lymphoblastoid with or without RBV | 9/72 a1/72 | 16/80 a5/80 | unknown |

| van der Meer AJ et al. (2012) [71] | Europe and Canada | 48 (mean) | median 8.4 years | R | 68% type 1 | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 13/125 a3/125 | 100/405 a103/405 | Ishak 4–6 |

| Maruoka D et al. (2012) [43] | Japan | 50.4–54 (mean) | mean 9.9 years | R | 73.6% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α/IFN-β with or without RBV | 10/221 a2/221 | 74/356 a50/356 | F3,4: 24.3% in Tx, F4: 43.1% in control |

| Cozen ML et al. (2013) [44] | US | 50.98 (mean) | mean 10 years | R | 68.7% type 1 | 8 | IFN-α with or without RBV | 6/69 | 25/90 | F3,4: 19% (30.2% in Tx, 10.1% in control) |

| Alfaleh FZ et al. (2013) [72] | Saudi Arabia, Egypt | 48 (mean) | mean 63.8 months | P | 30.6% type 4 | 8 | PegIFN with or without RBV | 0/62 a0/62 | 4/95 a8/95 | F3,4: 24.6% (27.1% in SVR, 31.1% in no SVR) |

| Aleman S et al. (2013) [45] | Sweden | 51 (mean) | mean 5.3 years | R | 50% type 1 | 8 | PegIFN with RBV | 11/110 a4/110 | 48/193 a35/193 | LC |

| Singal AG et al. (2013) [77] | US | 48 (median) | median 36–72 months | R | 68.6% type 1 | 7 | PegIFN with RBV | 2/83 | 41/159 | 17.3% LC |

| Dieperink E et al. (2014) [78] | US | 51.4 (mean) | median 7.5 years | R | 70% type 1 | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 19/222 a6/222 | 81/314 a56/314 | F3,4: 54.5% (41.3% in SVR, 64.7% in no SVR) |

| Kutala BK et al. (2015) [50] | France | 50 (median) | median 5.5 years | R | 55.7% type 1 | 8 | IFN/PegIFN with or without RBV | 3/104 | 27/221 | F3,4: 100% |

| Di Marco V et al. (2016) [73] | Italy | 58 (mean) | median 7.6 years | P | 83.4% type 1 | 8 | PegIFN with RBV | a8/108 | a98/336 | compensated LC |

a: Liver-specific death, SVR sustained virologic response, CHC chronic hepatitis C, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa scale, Tx treatment group, R retrospective cohort study, P prospective cohort study, RCT randomized controlled study, IFN interferon, PegIFN pegylated interferon, RBV ribavirin, LC liver cirrhosis

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of cohort study is described in the Table 3, 4, 5 and 6. This feature was evaluated as modifiers in each analysis. The methodological quality of RCT is described in Additional file 1: Appendix 1. Given the similar methodological quality among RCTs, sensitivity analysis or subgroup analyses based on the methodological quality in RCTs were not performed.

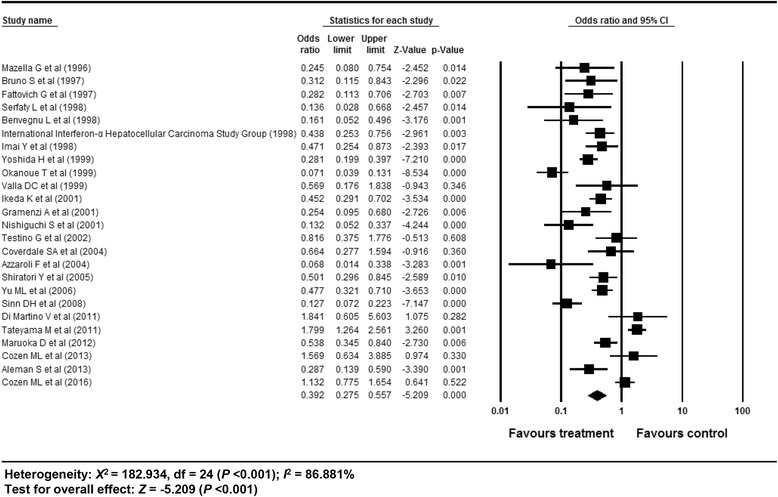

Efficacy of antiviral treatment on the development of HCC in chronic hepatitis C patients

The overall efficacy of antiviral treatment on the development of HCC exhibited an OR of 0.392 (95% CI: 0.275–0.557, p <0.001) in a random effect model analysis (Fig. 2). The funnel plot showed asymmetry on the right lower quadrant area (Additional file 1: Appendix Figure S2). However, the Egger’s test revealed an intercept of −2.131 (95% CI: −4.81–0.54, t-value: 1.64, df: 23, p = 0.11 (2-tailed)). The rank correlation test also showed a Kendall’s tau of −0.19 with a continuity correction (p = 0.17). The trim and fill method indicated that no study was trimmed. Overall, there was no evidence of publication bias.

Fig. 2.

Efficacy of antiviral treatment on the development of HCC in patients with CHC. The size of each square is proportional to the study’s weight. Diamond is the summary estimate from the pooled studies (random effect model). HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CHC, chronic hepatitis C

A cumulative meta-analysis of enrolled studies based on publication year showed no specific time trend (Additional file 1: Appendix 3). A cumulative meta-analysis based on effect size showed no small study bias (Additional file 1: Appendix 4). One study removed meta-analysis revealed a stable feature (Additional file 1: Appendix 5). Overall, the sensitivity meta-analyses revealed robust results.

Methodological quality of Newcastle-Ottawa scale potentially explained heterogeneity in meta-ANOVA tests (p = 0.027) (Additional file 1: Appendix 6). A meta-regression revealed a Newcastle-Ottawa scale score of 8 for the reason of heterogeneity (p = 0.027) (Additional file 2: Table S1). After excluding 10 studies (Newcastle-Ottawa scale 8), no covariates explained heterogeneity in meta-regression tests. Therefore, methodological quality was the reason of heterogeneity in this analysis.

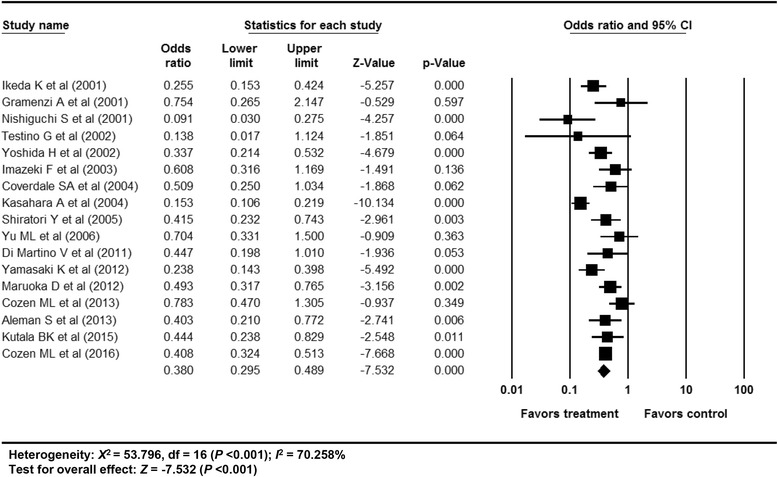

Efficacy of antiviral treatment on All-cause mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C

The overall efficacy of antiviral treatment on all-cause mortality revealed an OR of 0.380 (95% CI: 0.295–0.489, p <0.001) in a random effect model analysis (Fig. 3). The funnel plot showed asymmetry on the right lower quadrant area (Additional file 1: Appendix 7). However, the Egger’s test revealed an intercept of 0.266 (95% CI: −2.010–2.542, t-value: 0.25, df: 15, p = 0.81 (2-tailed)). The rank correlation test also showed a Kendall’s tau of 0.04 with a continuity correction (p = 0.84). The trim and fill method indicated that 1 study was trimmed. After excluding the study by Testino et al. [16] located on the left lower quadrant in funnel plot, the OR was 0.385 (95% CI: 0.298–0.496, p <0.001). Overall, the impact of bias was minimal.

Fig. 3.

Efficacy of antiviral treatment on all-cause mortality in patients with CHC. The size of each square is proportional to the study’s weight. Diamond is the summary estimate from the pooled studies (random effect model). CHC, chronic hepatitis C

A cumulative meta-analysis of enrolled studies based on publication year showed no specific time trend (Additional file 1: Appendix 8). A cumulative meta-analysis based on effect size showed no small study bias (Additional file 1: Appendix 9). One study removed meta-analysis revealed a stable feature (Additional file 1: Appendix 10). Overall, the sensitivity meta-analyses revealed robust results.

Meta-ANOVA or meta-regression showed no specific modifier for the reason of heterogeneity (Additional file 1: Appendix 11) (Additional file 2: Table S2). Overall, no covariates were found to be explaining heterogeneity in this meta-analysis.

Efficacy of antiviral treatment on liver-specific mortality in chronic hepatitis C patients

The overall efficacy of antiviral treatment on liver-specific mortality exhibited an OR of 0.363 (95% CI: 0.260–0.508, p <0.001) in a random effect model analysis (Additional file 1: Appendix 12). The funnel plot showed symmetry (Additional file 1: Appendix 13). However, the Egger’s test revealed that intercept was 3.06 (95% CI: 0.295–5.831, t-value: 2.43, df: 11, p = 0.03 (2-tailed)). The rank correlation test showed a Kendall’s tau of 0.28 with a continuity correction (p = 0.20). The trim and fill method indicated that no study was trimmed. After excluding an outlier (study by Kasahara A et al. [17]) located on the left upper quadrant area in funnel plot, the OR was 0.398 (95% CI: 0.314–0.504, p <0.001). Overall, the impact of bias was minimal.

A cumulative meta-analysis of enrolled studies based on publication year showed no specific time trend (Additional file 1: Appendix 14). A cumulative meta-analysis based on effect size showed no small study bias (Additional file 1: Appendix 15). One study removed meta-analysis revealed a stable feature (Additional file 1: Appendix 16). Overall, the sensitivity meta-analyses showed robust results.

A meta-ANOVA indicated that follow-up duration (p = 0.036) and methodological quality (p = 0.029) were suspicious for the reason of heterogeneity (Additional file 1: Appendix 17). A meta-regression indicated that follow-up duration (p = 0.036) and Newcastle-Ottawa scale score of 8 (p = 0.029) explained the heterogeneity (Additional file 2: Table S3). After excluding 2 studies (short-term follow-up duration), no covariates explained heterogeneity in meta-regression tests. After excluding 7 studies (Newcastle-Ottawa scale 8), no covariates explained heterogeneity in meta-regression tests. Therefore, follow-up duration and methodological quality were the reasons of heterogeneity in this analysis.

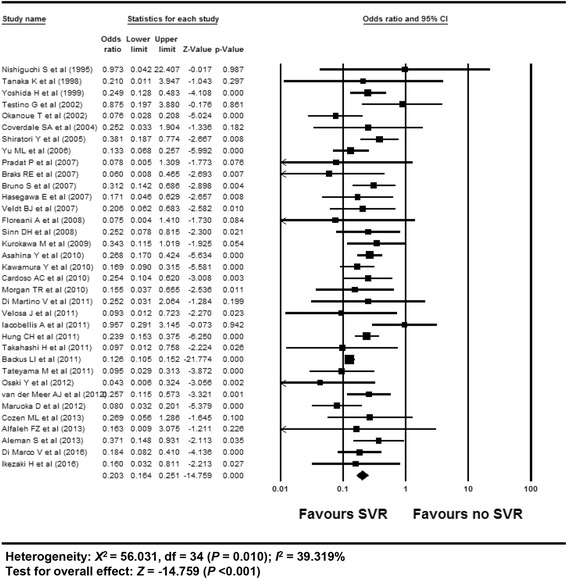

Efficacy of SVR on the development of HCC in patients with chronic hepatitis C

The overall efficacy of SVR on the development of HCC exhibited an OR of 0.203 (95% CI: 0.164–0.251, p <0.001) in a random effect model analysis (Fig. 4). The funnel plot showed symmetry (Additional file 1: Appendix 18). The Egger’s test showed that intercept was 0.56 (95% CI: −0.099–1.217, t-value: 1.73, df: 33, p = 0.09 (2-tailed)). The rank correlation test showed a Kendall’s tau of −0.17 with a continuity correction (p = 0.16). The trim and fill method indicated that no study was trimmed. Overall, there was no evidence of publication bias.

Fig. 4.

Efficacy of SVR on the development of HCC in patients with CHC. The size of each square is proportional to the study’s weight. Diamond is the summary estimate from the pooled studies (random effect model). SVR, sustained virologic response; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CHC, chronic hepatitis C

A cumulative meta-analysis of enrolled studies based on publication year showed no specific time trend (Additional file 1: Appendix 19). A cumulative meta-analysis based on effect size showed no small study bias (Additional file 1: Appendix 20). One study removed meta-analysis showed a stable feature (Additional file 1: Appendix 21). Overall, the sensitivity meta-analyses revealed robust results.

Meta-ANOVA or meta-regression identified no specific modifier for the reason of heterogeneity (Additional file 1: Appendix 22) (Additional file 2: Table S4). Overall, no covariates explained heterogeneity.

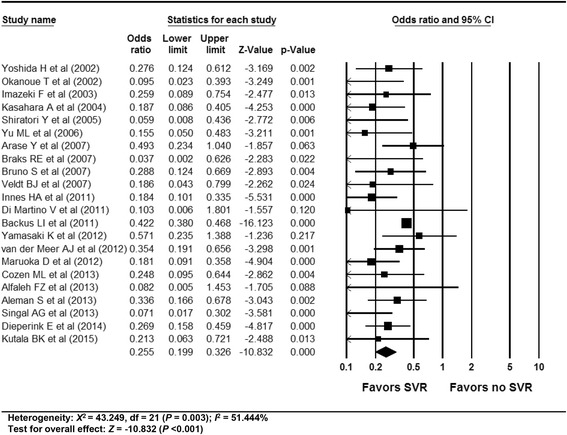

Efficacy of SVR on all-cause mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C

The overall efficacy of SVR on all-cause mortality revealed an OR of 0.255 (95% CI: 0.199–0.326, p < 0.001) in a random effect model analysis (Fig. 5). The funnel plot showed asymmetry on the right lower quadrant area (Additional file 1: Appendix 23). The Egger’s test showed that the intercept was −1.44 (95% CI: −1.921– −0.949, t-value: 6.16, df: 20, p <0.001 (2-tailed)). The rank correlation test showed a Kendall’s tau of −0.23 with a continuity correction (p = 0.14). The trim and fill method indicated 11 studies were trimmed. Overall, there was evidence of publication bias.

Fig. 5.

Efficacy of SVR on all-cause mortality in patients with CHC. The size of each square is proportional to the study’s weight. Diamond is the summary estimate from the pooled studies (random effect model). SVR, sustained virologic response; CHC, chronic hepatitis C

A cumulative meta-analysis of enrolled studies based on publication year showed no specific time trend (Additional file 1: Appendix 24). A cumulative meta-analysis based on effect size showed no small study bias (Additional file 1: Appendix 25). One study removed meta-analysis revealed a stable feature (Additional file 1: Appendix 26). Overall, the sensitivity meta-analyses showed robust results.

Meta-ANOVA indicated that methodological quality potentially explained heterogeneity (p = 0.030) (Additional file 1: Appendix 27). Meta-regression revealed a Newcastle-Ottawa scale score of 8 for the reason of heterogeneity (Additional file 2: Table S5). After excluding 16 studies (Newcastle-Ottawa scale 8), no covariates explained heterogeneity in meta-regression tests. Therefore, methodological quality was the reasons of heterogeneity in this analysis.

Efficacy of SVR on liver-specific mortality in chronic hepatitis C patients

The overall efficacy of SVR on liver-specific mortality exhibited an OR of 0.126 (95% CI: 0.094–0.169, p < 0.001) in a random effect model analysis (Additional file 1: Appendix 28). The funnel plot showed asymmetry on the right lower quadrant area (Additional file 1: Appendix 29). The Egger’s test indicated that intercept was −0.77 (95% CI: −1.473 – −0.057, t-value: 2.25, df: 21, p = 0.036 (2-tailed)). The rank correlation test revealed a Kendall’s tau of −0.19 with a continuity correction (p = 0.20). The trim and fill method showed 6 studies were trimmed. Overall, there was evidence of publication bias.

A cumulative meta-analysis of enrolled studies based on publication year showed no specific time trend (Additional file 1: Appendix 30). A cumulative meta-analysis based on effect size showed no small study bias (Additional file 1: Appendix 31). One study removed meta-analysis revealed a stable feature (Additional file 1: Appendix 32). Overall, the sensitivity meta-analyses showed robust results.

Meta-ANOVA or meta-regression revealed no specific modifier for the reason of heterogeneity (Additional file 1: Appendix 33) (Additional file 2: Table S6). Overall, no covariates explained heterogeneity.

The results of meta-regression analyses for each topic are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results of meta-regression analyses

| Modifier | Coefficient | Standard error | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOS (topic 1) | NOS 8: 1.203 NOS 7: 0.501 |

0.565 0.561 |

0.033 0.372 Q: 7.24, df: 2, P = 0.027 |

| Follow-up duration (topic 3) | 1.140 | 0.542 | 0.036 |

| NOS (topic 3) | NOS 8: −0.659 | 0.302 | 0.029 |

| NOS (topic 5) | NOS 8: −0.540 NOS 7: −0.544 |

0.209 0.322 |

0.010 0.091 Q: 7.03, df: 2, P = 0.030 |

NOS Newcastle-Ottawa scale

Discussion

This meta-analyses confirmed the long-term efficacy of antiviral treatment in terms of prevention of HCC and reduction in all-cause and liver-specific mortality in patients with chronic HCV infection. This long-term efficacy was also intensified when SVR was achieved. Clinical outcomes regarding the efficacy of antiviral therapy in CHC patients have been continuously investigated by previous studies with a small number of patients or short-term follow-up duration. The reasons for performing this meta-analysis were a persistent risk of HCC even after attainment of SVR and a lack of sufficient data regarding long-term efficacy [18]. Persistent low-level of viremia and dysplastic hepatocyte regeneration are representative grounds for persistent risk of HCC after antiviral treatment [19, 20]. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis revealed that IFN nonresponders exhibited a decreased risk of HCC recurrence after curative treatment of HCC, compared with no treatment patients, thus indicating that reduced necroinflammation and an inhibition of hepatic fibrosis progression prevent the development of HCC [21]. This results is consistent with that of our study and emphasized the importance of screening strategy of chronic hepatitis C.

Early antiviral treatment before progression to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis is associated with an increasing probability of achieving SVR [22]. However, an indolent course of chronic hepatitis C makes it difficult for early diagnosis and treatment. Authors have revealed that favorable antiviral efficacy persists in all patients with chronic hepatitis C, regardless of histology. This result was also confirmed by a previous study indicating favorable antiviral efficacy even in patients with LC [18]. Considering the advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis is the sequelae of long-standing inflammation of liver, our study confirmed antiviral treatment is still valid in the late course of chronic hepatitis C. Although histology was not a significant modifier in our meta-analysis, all of the included studies have substantially heterogeneous populations regarding the degree of fibrosis or cirrhosis of the liver. This finding was commonly detected in a previous meta-analysis [18]. However, considering the expanding treatment indication, including decompensated LC by the advent of direct-acting antiviral agents, histology is not expected to affect the long-term efficacy of antiviral treatment in the near future.

Despite the favorable efficacy of antiviral treatment, 2 modifiers associated with heterogeneity were identified in the meta-ANOVA and meta-regression analyses. Studies with Newcastle-Ottawa scale of 8 were modifier in the analysis of association between antiviral treatment and the development of HCC (Additional file 2: Table S1), in the analysis of association between antiviral treatment and the liver-specific mortality (Additional file 2: Table S3), and in the analysis of association between SVR and all-cause mortality (Additional file 2: Table S5). Studies with a short-term follow-up duration were also modifier in the analysis of association between antiviral treatment and liver-specific mortality (Additional file 2: Table S3). Although these modifiers were confirmed as not significantly affecting the results of main analyses, this finding indicated the need for more number of high-quality and long-term follow-up studies on this topic.

Publication bias was detected in 2 topics (topic 5 and 6). Sensitivity analyses including cumulative and one study removed meta-analyses were rigorously performed to find the small study effect associated with publication bias, and these analyses showed no small study effect. Overall, the impact of publication bias was minimal.

This meta-analysis included the largest number of articles identified by a comprehensive literature search, and potential confounding modifiers were searched within each study whenever possible. Sensitivity analyses and meta-regression tests were performed to demonstrate robustness or identify the reason of heterogeneity. Despite the strengths, several limitations were detected during the systematic review. First, pretreatment predictive factors associated with the treatment response were not controlled or evaluated in these analyses, including pretreatment viral load, genotype, IL-28β polymorphism, and HBV or HIV coinfection. Direct-acting antiviral agents are expected to overcome these factors. Therefore, results of studies including these agents are expected in the near future. Second, the baseline characteristics of each enrolled study were not comparable between the treatment vs. no treatment groups, or the SVR vs. no SVR groups in some studies. This phenomenon was reflected in the evaluation of methodological quality and was confirmed to be a significant modifier associated with heterogeneity. Notably, difference by race or country including life style (obesity, consumption of alcohol or aflatoxin-contaminated foods, and chemical carcinogens exposure) was not appropriately investigated in our study. Considering the HCC is a heterogenous malignancy resulting from diverse causes of liver injury, different mechanisms or molecular pathways on the basis of country could be a cause of different treatment response. However, due to the heterogenous baseline characteristics including genotype and lacking of enough data about risk factors of HCC, the subgroup analyses by country could not present meaningful data. The limitations described above could be a cause of potential heterogeneity and bias. Therefore, studies controlling for various risk factors are needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C showed improved outcome in the development of HCC and mortality, especially when SVR is achieved, although studies controlling for various risk factors of HCC and mortality are still lacking.

Additional files

Contains 33 figures including assessment of methodological quality, funnel plots for publication bias, sensitivity analyses, and Meta-ANOVA. (DOC 24248 kb)

Contains 6 tables including detailed meta-regression data of 6 study topics of this study. (DOC 79 kb)

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to appreciate Dr. Young Joo Yang’s effort for helping manuscript searching and data filling up for this study.

Funding

There was no financial or grant support related to this article.

Availability of data and materials

Input data for the analyses are available from the corresponding author on request.

Author’s contributions

CSB participated study concept, design, literature search, data abstraction, data analysis and manuscript writing. IHS participated study concept, design, data analysis and gave final approval for publication. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Competing interests

None

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CHC

Chronic hepatitis C

- CI

Confidence interval

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- IFN

Interferon

- OR

Odds ratio

- PegIFN

Pegylated interferon

- RBV

Ribavirin

- RCT

Randomized controlled studies

- SVR

Sustained virologic response

Contributor Information

Chang Seok Bang, Email: csbang@hallym.ac.kr.

Il Han Song, Phone: +82 41 5503924, Email: ihsong21@dankook.ac.kr.

References

- 1.AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;62:932–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.27950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swain MG, Lai M, Shiffman ML, Cooksley WG, Zeuzem S, Dieterich DT, Abergel A, Pessôa MG, Lin A, Tietz A, et al. A sustained virologic response is durable in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with peginterferon Alfa-2a and ribavirin. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1593–601. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinot-Peignoux M, Stern C, Maylin S, Ripault MP, Boyer N, Leclere L, Castelnau C, Giuily N, El Ray A, Cardoso AC, et al. Twelve weeks posttreatment follow-up is as relevant as 24 weeks to determine the sustained virologic response in patients with hepatitis c virus receiving pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Hepatology. 2010;51:1122–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.23444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wen Y, Zheng YX, de Tan M. A comprehensive long-term prognosis of chronic hepatitis C patients with antiviral therapy: a meta-analysis of studies from 2008 to 2014. Hepat Mon. 2015;15:e27181. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.15(5)2015.27181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011, 2013.

- 6.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, Petticrew M, Altman DG. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:1–173. doi: 10.3310/hta7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for meta-analysis in medical research. Chichester (UK): Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046–55. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Testino G, Ansaldi F, Andorno E, Ravetti GL, Ferro C, De Iaco F, Icardi G, Valente U. Interferon therapy does not prevent hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV compensated cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1636–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasahara A, Tanaka H, Okanoue T, Imai Y, Tsubouchi H, Yoshioka K, Kawata S, Tanaka E, Hino K, Hayashi K, et al. Interferon treatment improves survival in chronic hepatitis C patients showing biochemical as well as virological responses by preventing liver-related death. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:148–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singal AK, Singh A, Jaganmohan S, Guturu P, Mummadi R, Kuo YF, Sood GK. Antiviral therapy reduces risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung CH, Lee CM, Lu SN, Wang JH, Hu TH, Tung HD, Chen CH, Chen WJ, Changchien CS. Long-term effect of interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin therapy on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:409–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerotto M, Dal Pero F, Bortoletto G, Ferrari A, Pistis R, Sebastiani G, Fagiuoli S, Realdon S, Alberti A. Hepatitis C minimal residual viremia (MRV) detected by TMA at the end of Peg-IFN plus ribavirin therapy predicts post-treatment relapse. J Hepatol. 2006;44:83–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Yamamoto K. Meta-analysis: reduced incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients not responding to interferon therapy of chronic hepatitis C. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:989–96. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everson GT, Hoefs JC, Seeff LB, Bonkovsky HL, Naishadham D, Shiffman ML, Kahn JA, Lok AS, Di Bisceglie AM, Lee WM, et al. Impact of disease severity on outcome of antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C: lessons from the HALT-C trial. Hepatology. 2006;44:1675–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.21440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazzella G, Accogli E, Sottili S, Festi D, Orsini M, Salzetta A, Novelli V, Cipolla A, Fabbri C, Pezzoli A, et al. Alpha interferon treatment may prevent hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1996;24:141–7. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(96)80022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruno S, Silini E, Crosignani A, Borzio F, Leandro G, Bono F, Asti M, Rossi S, Larghi A, Cerino A, et al. Hepatitis C virus genotypes and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatology. 1997;25:754–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, Diodati G, Tremolada F, Nevens F, Almasio P, Solinas A, Brouwer JT, Thomas H, et al. Effectiveness of interferon Alfa on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensation in cirrhosis type C. European concerted action on viral hepatitis (EUROHEP) J Hepatol. 1997;27:201–5. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serfaty L, Aumaitre H, Chazouilleres O, Bonnand AM, Rosmorduc O, Poupon RE, Poupon R. Determinants of outcome of compensated hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;27:1435–40. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benvegnu L, Chemello L, Noventa F, Fattovich G, Pontisso P, Alberti A. Retrospective analysis of the effect of interferon therapy on the clinical outcome of patients with viral cirrhosis. Cancer. 1998;83:901–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980901)83:5<901::AID-CNCR15>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Interferon-alpha Hepatocellular Carcinoma Study Group. Effect of interferon-alpha on progression of cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 1998;351:1535–9. [PubMed]

- 29.Imai Y, Kawata S, Tamura S, Yabuuchi I, Noda S, Inada M, Maeda Y, Shirai Y, Fukuzaki T, Kaji I, et al. Relation of interferon therapy and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Osaka hepatocellular carcinoma prevention study group. Ann Internal Med. 1998;129:94–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-2-199807150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida H, Shiratori Y, Moriyama M, Arakawa Y, Ide T, Sata M, Inoue O, Yano M, Tanaka M, Fujiyama S, et al. Interferon therapy reduces the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma: national surveillance program of cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C in Japan. IHIT study group. Inhibition of hepatocarcinogenesis by interferon therapy. Ann Internal Med. 1999;131:174–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okanoue T, Itoh Y, Minami M, Sakamoto S, Yasui K, Sakamoto M, Nishioji K, Murakami Y, Kashima K. Interferon therapy lowers the rate of progression to hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C but not significantly in an advanced stage: a retrospective study in 1148 patients. Viral hepatitis therapy study group. J Hepatol. 1999;30:653–9. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(99)80196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valla DC, Chevallier M, Marcellin P, Payen JL, Trepo C, Fonck M, Bourliere M, Boucher E, Miguet JP, Parlier D, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: a randomized, controlled trial of interferon alfa-2b versus no treatment. Hepatology. 1999;29:1870–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Suzuki Y, Suzuki F, Tsubota A, Arase Y, Murashima N, Chayama K, Kumada H. Long-term interferon therapy for 1 year or longer reduces the hepatocellular carcinogenesis rate in patients with liver cirrhosis caused by hepatitis C virus: a pilot study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:406–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gramenzi A, Andreone P, Fiorino S, Cammà C, Giunta M, Magalotti D, Cursaro C, Calabrese C, Arienti V, Rossi C, et al. Impact of interferon therapy on the natural history of hepatitis C virus related cirrhosis. Gut. 2001;48:843–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.6.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishiguchi S, Shiomi S, Nakatani S, Takeda T, Fukuda K, Tamori A, Habu D, Tanaka T. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic active hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Lancet. 2001;357:196–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coverdale SA, Khan MH, Byth K, Lin R, Weltman M, George J, Samarasinghe D, Liddle C, Kench JG, Crewe E, et al. Effects of interferon treatment response on liver complications of chronic hepatitis C: 9-years follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:636–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azzaroli F, Accogli E, Nigro G, Trere D, Giovanelli S, Miracolo A, Lodato F, Montagnani M, Tamé M, Colecchia A, et al. Interferon plus ribavirin and interferon alone in preventing hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study on patients with HCV related cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3099–102. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i21.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiratori Y, Ito Y, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Nakata R, Tanaka N, Arakawa Y, Hashimoto E, Hirota K, Yoshida H, et al. Antiviral therapy for cirrhotic hepatitis C: association with reduced hepatocellular carcinoma development and improved survival. Ann Internal Med. 2005;142:105–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu ML, Lin SM, Chuang WL, Dai CY, Wang JH, Lu SN, Sheen IS, Chang WY, Lee CM, Liaw YF. A sustained virological response to interferon or interferon/ribavirin reduces hepatocellular carcinoma and improves survival in chronic hepatitis C: a nationwide, multicentre study in Taiwan. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:985–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinn DH, Paik SW, Kang P, Kil JS, Park SU, Lee SY, Song SM, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Lee JH, et al. Disease progression and the risk factor analysis for chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2008;28:1363–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Martino V, Crouzet J, Hillon P, Thévenot T, Minello A, Monnet E. Long-term outcome of chronic hepatitis C in a population-based cohort and impact of antiviral therapy: a propensity-adjusted analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:493–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tateyama M, Yatsuhashi H, Taura N, Motoyoshi Y, Nagaoka S, Yanagi K, Abiru S, Yano K, Komori A, Migita K, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein above normal levels as a risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients infected with hepatitis C virus. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:92–100. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maruoka D, Imazeki F, Arai M, Kanda T, Fujiwara K, Yokosuka O. Long-term cohort study of chronic hepatitis C according to interferon efficacy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:291–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cozen ML, Ryan JC, Shen H, Lerrigo R, Yee RM, Sheen E, Wu R, Monto A. Nonresponse to interferon-alpha based treatment for chronic hepatitis C infection is associated with increased hazard of cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aleman S, Rahbin N, Weiland O, Davidsdottir L, Hedenstierna M, Rose N, Verbaan H, Stål P, Carlsson T, Norrgren H, et al. A risk for hepatocellular carcinoma persists long-term after sustained virologic response in patients with hepatitis C-associated liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:230–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cozen ML, Ryan JC, Shen H, Cheung R, Kaplan DE, Pocha C, Brau N, Aytaman A, Schmidt WN, Pedrosa M, et al. Improved survival among all interferon-alpha-treated patients in HCV-002, a veterans affairs hepatitis C cohort of 2211 patients, despite increased cirrhosis among nonresponders. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1744–56. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4122-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida H, Arakawa Y, Sata M, Nishiguchi S, Yano M, Fujiyama S, Yamada G, Yokosuka O, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Interferon therapy prolonged life expectancy among chronic hepatitis C patients. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:483–91. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imazeki F, Yokosuka O, Fukai K, Saisho H. Favorable prognosis of chronic hepatitis C after interferon therapy by long-term cohort study. Hepatology. 2003;38:493–502. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamasaki K, Tomohiro M, Nagao Y, Sata M, Shimoda T, Hirase K, Shirahama S. Effects and outcomes of interferon treatment in Japanese hepatitis C patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kutala BK, Guedj J, Asselah T, Boyer N, Mouri F, Martinot-Peignoux M, Valla D, Marcellin P, Duval X. Impact of treatment against hepatitis C virus on overall survival of naive patients with advanced liver disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:803–10. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04027-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishiguchi S, Kuroki T, Nakatani S, Morimoto H, Takeda T, Nakajima S, Shiomi S, Seki S, Kobayashi K, Otani S. Randomised trial of effects of interferon-alpha on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic active hepatitis C with cirrhosis. Lancet. 1995;346:1051–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91739-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanaka K, Sata M, Uchimura Y, Suzuki H, Tanikawa K. Long-term evaluation of interferon therapy in hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis: does IFN prevent development of hepatocellular carcinoma? Oncol Rep. 1998;5:205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okanoue T, Itoh Y, Kirishima T, Daimon Y, Toyama T, Morita A, Nakajima T, Minami M. Transient biochemical response in interferon therapy decreases the development of hepatocellular carcinoma for 5 years and improves the long-term survival of chronic hepatitis C patients. Hepatol Res. 2002;23:62–77. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6346(02)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pradat P, Tillmann HL, Sauleda S, Braconier JH, Saracco G, Thursz M, Goldin R, Winkler R, Alberti A, Esteban JI, et al. Long-term follow-up of the hepatitis C HENCORE cohort: response to therapy and occurrence of liver-related complications. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:556–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braks RE, Ganne-Carrie N, Fontaine H, Paries J, Grando-Lemaire V, Beaugrand M, Pol S, Trinchet JC. Effect of sustained virological response on long-term clinical outcome in 113 patients with compensated hepatitis C-related cirrhosis treated by interferon alpha and ribavirin. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5648–53. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i42.5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruno S, Stroffolini T, Colombo M, Bollani S, Benvegnù L, Mazzella G, Ascione A, Santantonio T, Piccinino F, Andreone P, et al. Sustained virological response to interferon-alpha is associated with improved outcome in HCV-related cirrhosis: a retrospective study. Hepatology. 2007;45:579–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasegawa E, Kobayashi M, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Akuta N, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Arase Y, et al. Efficacy and anticarcinogenic activity of interferon for hepatitis C virus-related compensated cirrhosis in patients with genotype 1b low viral load or genotype 2. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:793–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Veldt BJ, Heathcote EJ, Wedemeyer H, Reichen J, Hofmann WP, Zeuzem S, Manns MP, Hansen BE, Schalm SW, Janssen HL. Sustained virologic response and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:677–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-10-200711200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Floreani A, Baldo V, Rizzotto ER, Carderi I, Baldovin T, Minola E. Pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for naive patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:734–7. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318046ea75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurokawa M, Hiramatsu N, Oze T, Mochizuki K, Yakushijin T, Kurashige N, Inoue Y, Igura T, Imanaka K, Yamada A, et al. Effect of interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin therapy on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:432–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asahina Y, Tsuchiya K, Tamaki N, Hirayama I, Tanaka T, Sato M, Yasui Y, Hosokawa T, Ueda K, Kuzuya T, et al. Effect of aging on risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2010;52:518–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.23691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawamura Y, Arase Y, Ikeda K, Hirakawa M, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Akuta N, et al. Diabetes enhances hepatocarcinogenesis in noncirrhotic, interferon-treated hepatitis C patients. Am J Med. 2010;123:951–6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cardoso AC, Moucari R, Figueiredo-Mendes C, Ripault MP, Giuily N, Castelnau C, Boyer N, Asselah T, Martinot-Peignoux M, Maylin S, et al. Impact of peginterferon and ribavirin therapy on hepatocellular carcinoma: incidence and survival in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:652–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morgan TR, Ghany MG, Kim HY, Snow KK, Shiffman ML, De Santo JL, Lee WM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bonkovsky HL, Dienstag JL, et al. Outcome of sustained virological responders with histologically advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;52:833–44. doi: 10.1002/hep.23744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Velosa J, Serejo F, Marinho R, Nunes J, Glória H. Eradication of hepatitis C virus reduces the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1853–61. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1621-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iacobellis A, Perri F, Valvano MR, Caruso N, Niro GA, Andriulli A. Long-term outcome after antiviral therapy of patients with hepatitis C virus infection and decompensated cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hung CH, Lee CM, Wang JH, Hu TH, Chen CH, Lin CY, Lu SN. Impact of diabetes mellitus on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with interferon-based antiviral therapy. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2344–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takahashi H, Mizuta T, Eguchi Y, Kawaguchi Y, Kuwashiro T, Oeda S, Isoda H, Oza N, Iwane S, Izumi K, et al. Post-challenge hyperglycemia is a significant risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:790–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, Belperio P, Halloran J, Mole LA. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509–16.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Osaki Y, Ueda Y, Marusawa H, Nakajima J, Kimura T, Kita R, Nishikawa H, Saito S, Henmi S, Sakamoto A, et al. Decrease in alpha-fetoprotein levels predicts reduced incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus infection receiving interferon therapy: a single center study. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:444–51. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, Duarte-Rojo A, Heathcote EJ, Manns MP, Kuske L, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308:2584–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.144878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alfaleh FZ, Alswat K, Helmy A, Al-hamoudi W, El-sharkawy M, Omar M, Shalaby A, Bedewi MA, Hadad Q, Ali SM, et al. The natural history and long-term outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 4 after interferon-based therapy. Liver Int. 2013;33:871–83. doi: 10.1111/liv.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Di Marco V, Calvaruso V, Ferraro D, Ferraro D, Bavetta MG, Cabibbo G, Conte E, Cammà C, Grimaudo S, Pipitone RM, et al. Effects of Viral Eradication in Patients with HCV and Cirrhosis Differ With Stage of Portal Hypertension. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:130-139.e2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Ikezaki H, Nomura H, Furusyo N, Ogawa E, Kajiwara E, Takahashi K, Kawano A, Maruyama T, Tanabe Y, Satoh T, et al. Efficacy of interferon-beta plus ribavirin combination treatment on the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:E174–80. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arase Y, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Akuta N, Someya T, Koyama R, Hosaka T, et al. Long-term outcome after interferon therapy in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C. Intervirology. 2007;50:16–23. doi: 10.1159/000096308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]