Highlights

-

•

Methastases to thyroid gland are a rare condition.

-

•

RCC (renal cell carcinoma) is the most common primitive tumour which leads to thyroid methastases.

-

•

Preopeative diagnosis is hard to be established with routinary techniques.

-

•

Surgical approach (total thyroidectomy) is useful to obtain long survival rate.

Keywords: Thyroid, Cancer, Metastases, RCC

Abstract

Introduction

We report the case of an incidental solitary renal cancer cell (RCC) thyroid metastatic nodule treated by thyroidectomy.

Presentation of case

A 53 year male presented with a solitary, asymptomatic thyroid nodule. He was treated with left nephrectomy 1 year before for a RCC. Radiological standard follow-up was negative for secondary lesions but ultrasound (US) 12 months after surgery revealed a 1.5 cm solid nodule in the right lobe of the gland. Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was inadequate and the patient was submitted to total thyroidectomy. Histology showed the presence of solitary metastasis from RCC. At 2 years follow-up, no evidence of recurrence has been found.

Discussion

Solitary RCC metastasis to the thyroid usually occurs late from nephrectomy and have no specific US pattern. When FNAB provides an uncertain cytological results, the patient received thyroidectomy for primary thyroid tumors and diagnosis of metastases from RCC was incidentally made.

Conclusion

Thyroid nodules in a patient with history of malignancy can pose a diagnostic challenge. The presence of a solitary thyroid nodule in a patient with history of RCC should be carefully suspected for metastasis. We suggest to extend at neck the thorax and abdomen CT scan routinely recommended during the follow-up in high-risk cases. Thyroidectomy may result in prolonged survival in selected cases of isolated thyroid metastasis from RCC.

1. Introduction

Intra-thyroid Metastases (ITM) are very rare, approximately representing 1–2.4% of all malignant nodules [1].

Autopsy studies in patient who die for cancer suggest that these tumors are underdiagnosed with frequency up to 24.4% [2].

About half of these non-thyroid malignancies arise from RCC [3].

These metastases have not a typical symptomatology and show a late presentation from nephrectomy, making often impossible an early different diagnosis from primary thyroid tumors. Routine diagnostic techniques (US and CT scan) are unable to distinguish primary from secondary thyroid tumours. Cytological exam by fine FNAB has been shown to achieve an accuracy of over 90% for thyroid methastasis [4].

Appropriate management of ITM is controversial but thyroidectomy for RCC solitary metastases is a reasonable option to improve outcome and increase survival in selected patients.

We present a case of ITM from RCC unexpectedly detected after total thyroidectomy for a solitary nodule preoperatively classified as primitive thyroid tumour.

The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [19].

2. Case report

A 53-years-old male underwent surgical visit for a single and palpable thyroid nodule. The patient was submitted to left nephrectomy for RCC (pT1c N0 Mx – G3) 1 year before. Follow-up showed no metastasis or locoregional recurrence with thorax/abdomen CT scan at 6 and 12 months performed according to ESMO Guidelines [5].

He referred no symptoms linked to thyroid hyperfunction and blood exams where unremarkable (FT3: 2.32 pg/mL, n.v. 1.8–4.6 pg/mL; FT4: 1.23 ng/dL, n.v. 0.9–1.7 ng/dL; TSH 1.76 μUI/mL, n.v. 0.3–4.2 μUI/mL). Clinical examination revealed a little asymptomatic nodule in the right lobe of the gland. No regional lymph node was detected with palpation. Thyroid US confirmed a 1.5 cm solid, hypoechoic nodule with intranodular vascularization in the right thyroid lobe, highly suspected for neoplasm. FNAB was inadequate. Therefore, the patient accepted the surgical approach and a total thyroidectomy was performed with no early or late complication. Histology showed the presence of a single, white, partly capsulated nodule in the right thyroid lobe characterised by RCC+, CD10+, Vimentin +, TTF1− and Thyroglobulin−. This report, as suggested by immunohistochemistry and clinical history, was highly suggestive for metastasis from RCC. Two years after surgery no evidence of other site of tumor recurrence has been found.

3. Discussion

ITM represent less than 2.5% of all thyroid malignances [1]. Despite metastases are of diverse histogenesis and include a variety of carcinomas as well as sarcomas, melanomas, and hematologic malignancies, quite half of ITM rise from RCC [3].

Generally RCC diffuses in an unpredictable manner and can show a late recurrence as a notable feature. Clinical presentation of ITM is nonspecific and tumors are often unsuspected especially when metastases develop many years after the primary diagnosis. Recently it has been reported that in 67% of ITM, indication to thyroidectomy was for suspected primary thyroid malignancies or nodular goiter [6]. Also in our case, ITM was the first metastatic site during follow-up for RCC removed 1 years before and it was misinterpreted as a primary thyroid tumor.

In patients treated for RCC with radical nephrectomy, follow-up is carefully managed to establish local recurrence and/or the presence of metastases. This is stressed by the high incidence of recurrence of neoplasm that appear in almost 60% of the patients in the first year from diagnosis [7]. The recurrence of the neoplasm has to be identified as soon as possible because the possibility to obtain a radical resection decreases with increasing delay of diagnosis [8]. In literature, there are no current prospective randomized trials that help to evaluate the correct timing and/or which patients should be strictly evaluated for high risk of recurrence. However, important clinical and molecular factors, identified at primary diagnosis, emerge from long-term follow-up, showing which patients have an increased risk of recurrence and therefore have to be strictly followed [9]. According to these data, CT scans of thorax and abdomen are routinely carried out, with time intervals depending on risk factors. It is recommended to perform CT scans every 3–6 months in high-risk patients for the first 2 years, while a yearly CT scan is probably sufficient in low-risk patients [5]. Timing and duration of follow-up is controversy in literature for clinical and cost-effectiveness reasons.

In retrospective studies [10] it has been reported that thyroid metastases usually present in the context of widespread metastatic disease, more rarely they appear as a single mass. The reported interval of presentation for metachronous isolated ITM is very wide ranging from 68 to 130 months [11]. Our case represent an exception because ITM has been detected only 1 year after nephrectomy; this may be linked to the physical shape of the patient, who was very thin and immediately noted the nodule in the neck. Interestingly, the thorax/abdomen CT scans at 6 and 12 months after surgery did not target the ITM. The rarity of ITM do not allow to propose a routinely US or CT study of the neck. Our experience suggests that CT-scan proposed in ESMO follow-up should be extended to the neck without a significant increase of cost.

When ITM appears as single non-functioning nodule, often several years after nephrectomy, metastatic RCC may be misinterpreted as a primary thyroid tumor. US distinction between primary versus secondary thyroid neoplasm is almost impossible [12]. The commonly known US features of thyroid metastasis are nonspecific findings including nonhomogeneous hypoechogenicity, noncircumscribed margins, no calcifications, and increased vascularity [3]. The true metastatic nature of the tumor is recognized only after tumor sampling. FNAB has become an important tool in diagnosis of the thyroid nodules but in case of ITM, an accuracy ranging from 70% to 90% has been recently reported [3], [11], and the most common primary tumor sites for which FNAB did not make the correct diagnosis were kidney and lung [3], [11]. Noncontributory FNAB can result from inadequate sampling or interpretation difficulties. Increased vascularity, like showed in metastatic nodules from RCC, may be the most plausible reason for the low diagnostic yield of FNAB in relation to high blood contamination, which makes cytologic examinations more difficult [13]. Immunohistochemistry (HIC) can be able to differentiate between primary and secondary thyroid malignancies but it cannot be performed with FNAB specimens [3]. Another potential source of confusion in cytologic interpretation is the difficulty of distinguishing primary anaplastic thyroid carcinoma from metastatic high-grade malignancy. Positive immunostaining for thyroglobulin suggests a primary thyroid malignancy [12] remembering that only 20% to 30% of anaplastic carcinomas stain for thyroglobulin [14].

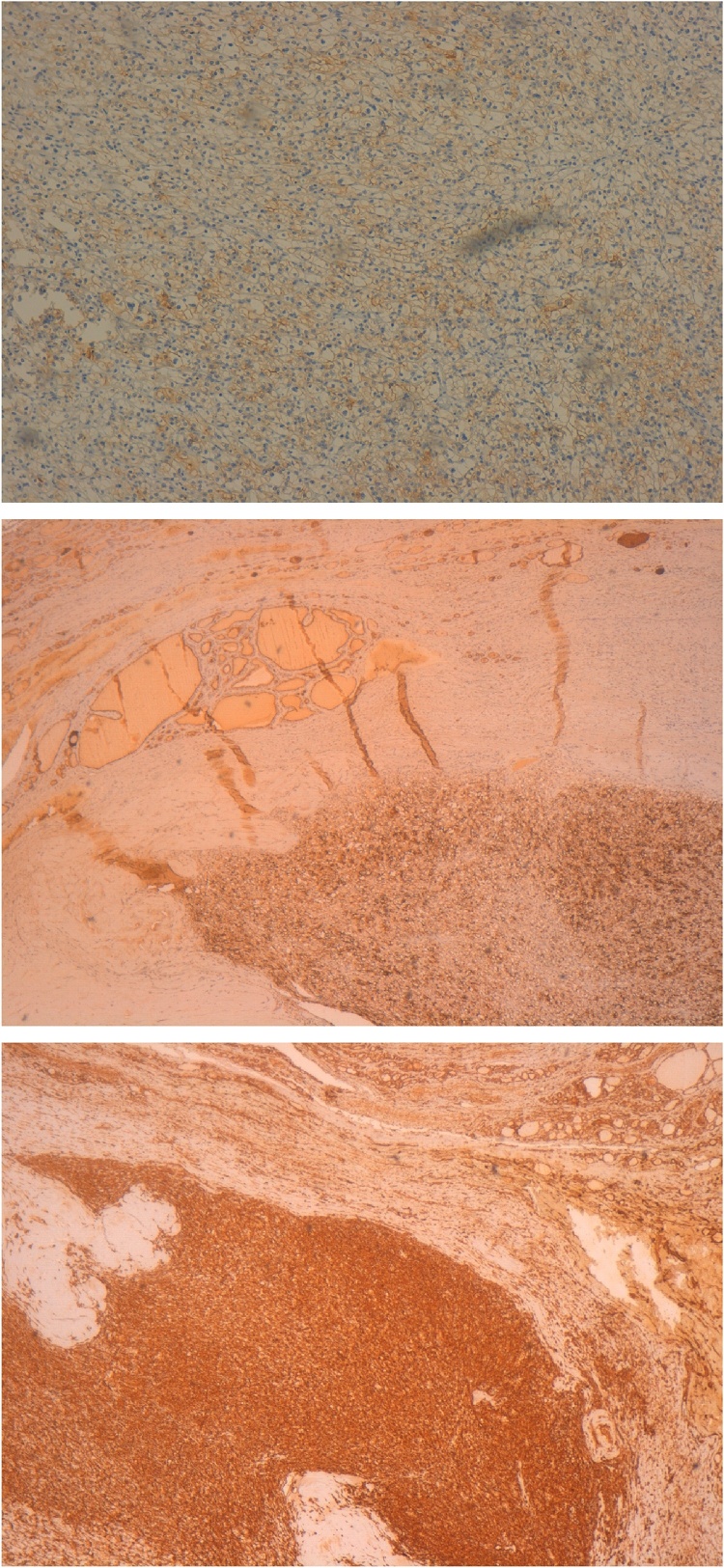

In our case, thyroid was the first metastatic site of a RCC diagnosed and removed 12 months earlier. US revealed a solid lesion suggestive of a neoplastic nodule but cytological examination after FNAB was inadequate. The patient was submitted to total thyroidectomy for suspected primary thyroid carcinoma according to the standard treatment of the thyroid neoplasm adopted in our institute. The metastatic nature of the thyroid nodule was then unexpected. The histological examination with immunohistochemistry (Thyroglobulin and TTF-1 negative with CD10 and Vimentin positive) (Figure) and the patient’s history of previous RCC provided definitive diagnosis (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

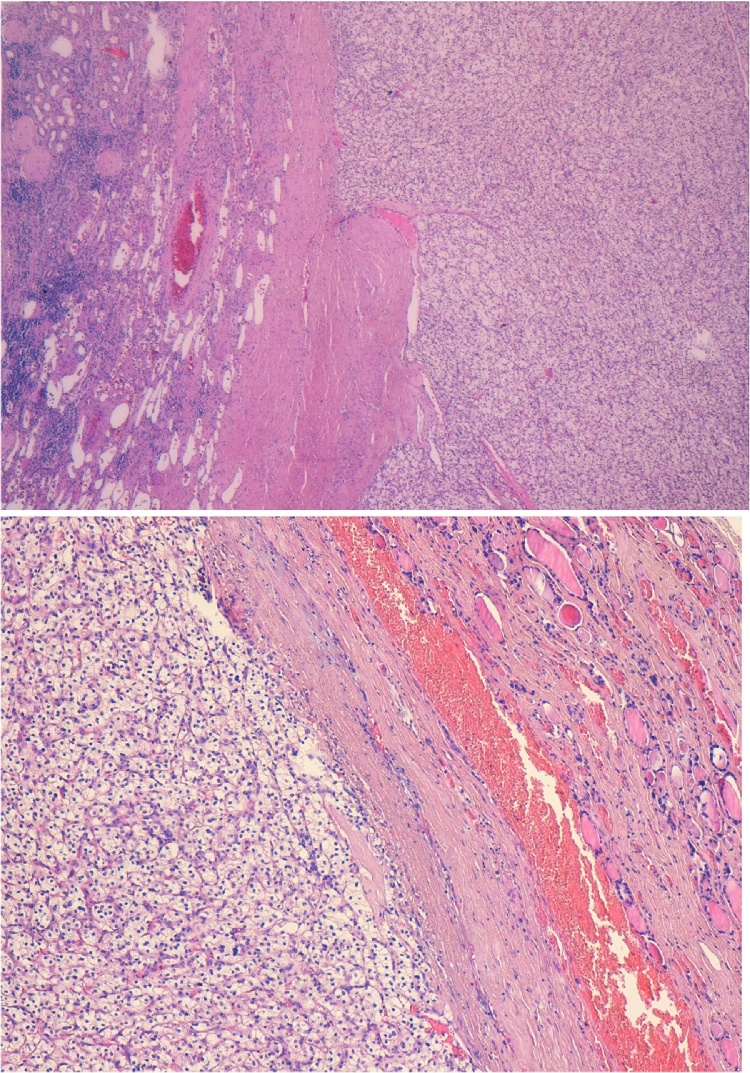

Fig. 1.

Upper image: Primitive tumor (RCC), H-H, 4×. Lower image: Intra-thyroid Metastases (ITM) from RCC, H-H, 10×.

Fig. 2.

Immunoistochemistry in ITM from RCC. From up to above: CD10+, Thyroglobulin −, Vimentine + (4×).

Although 35–80% of patients with thyroid involvement from different malignancies present with multi-organ metastases [15], overall prognosis appears to be most closely linked to the innate features of the primary tumor [3]. In cases of aggressive primary RCC and diffuse metastases, the prognosis is poor and thyroid surgery is only recommended with palliative intent with the aim of improving quality of life by preventing airway obstruction [16]. However, for those patients with an indolent primary lesion and disease confined to the thyroid gland without significant extra-thyroid extension, surgery with curative intent is possible and may offer good survival rates and long disease-free intervals [6], [17]. For this reason, an aggressive operative approach has been advocated by several authors, considering the minimal morbidity associated, and a median survival of approximately 5 years despite the 20% of thyroidectomies were performed without curative intents [10], [18].

Recently, a multicentre retrospective study has found 30% of local neck recurrence after thyroidectomy for metastatic RCC. This event develop more often in patients with tumor spread to adjacent structures, and thyroid metastases exceeding 3.5 cm [6]. The risk of cervical recurrence was not reduced by total vs subtotal thyroidectomies [6]. However, should keep in mind that, for more patients, the primary indication to the thyroidectomy was primitive thyroid cancer or nodular goiter in which total thyroidectomy was wide accepted like standard of care. Furthermore, improved surgical techniques and the introduction of new coagulation devices have greatly facilitated the performance of total thyroidectomy for quite all thyroid gland diseases.

The presence of a solitary thyroid nodule in a patient with history of RCC must be carefully suspected for a secondary tumour. From the review of literature, the addition of thyroid evaluation to standard thorax/abdomen CT scans seems to be recommendable also in the first 12 months of follow-up for high-risk cases. Thyroidectomy performed for ITM from RCC results safe and associated in selected patients with favourable long-term outcome.

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent

The patient gave written informed consent for the publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

Di Furia M. and Della Penna A. contributed the original idea and steasure of the manuscript.

Clementi M. contributed by conceptualization and performing the surgical procedures.

Salvatorelli A. contributed by collecting all the data.

Guadagni S. contributed by conceptualization and revision of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding sources

All the authors declare that they have no source of funding.

Ethical approval

There is no need for ethical approval because it is a case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Guarantor

Dott. Di Furia.

References

- 1.Calzolari F., Sartori P.V., Talarico C. Surgical treatment of intrathyroid metastases: preliminary results of a multicentric study. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(5B):2885–2888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berge T., Lundberg S. Cancer in Malmö 1958–1969: an autopsy study. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1977;260(Suppl):1–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung A.Y., Tran T.B., Brumund K.T. Metastases to the thyroid: a review of the literature from the last decade. Thyroid. 2012;22:258–268. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aron M., Kapila K., Verma K. Role of fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of secondary tumors of the thyroid—twenty years’ experience. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2006;34:240–245. doi: 10.1002/dc.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escudier B., Porta C., Schmidinger M. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2016;27(Suppl. 5):v58–v68. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iesalnieks I., Machens A., Bures C. Local recurrence in the neck and survival after thyroidectomy for metastaticrenal cell carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015;22(6):1798–1805. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janzen N.K., Kim H.L., Figlin R.A. Surveillance after radical or partial nephrectomy for localized renal cell carcinoma and management of recurrent disease. Urol. Clin. North Am. 2003;30:843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(03)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau W.K., Blute M.L., Weaver A.L. Matched comparison of radical nephrectomy vs nephron-sparing surgery in patients with unilateral renal cell carcinoma and a normal contralateral kidney. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2000;75:1236–1242. doi: 10.4065/75.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cindolo L., Patard J.J., Chiodini P. Comparison of predictive accuracy of four prognostic models for non metastatic renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy: a multicenter European study. Cancer. 2005;104:1362–1371. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beutner U., Leowardi C., Bork U. Survival after renal cell carcinoma metastasis to the thyroid: single center experience and systematic review of the literature. Thyroid. 2015;25(March (3)):314–324. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegerova L., Griebeler M.L., Reynolds J.P. Metastasis to the thyroid gland: report of a large series from the Mayo Clinic. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;38(August (4)):338–342. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31829d1d09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heffess C.S., Wenig B.M., Thompson L.D. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the thyroid gland. A clinicopathologic study of 36 cases. Cancer. 2002;95:1869–1878. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon W.J., Baek J.H., Choi J.W. The value of gross visual assessment of specimen adequacy for liquid-based cytology during ultrasound-guided, fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules. Endocr. Pract. 2015;21:1219–1226. doi: 10.4158/EP14529.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurlimann J., Gardiol D., Scazziga B. Immunohistology of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. A study of 43 cases. Histopathology. 1987;11:567–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1987.tb02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iesalnieks I., Winter H., Bareck E. Thyroid metastases of renal cell carcinoma: clinical course in 45 patients undergoing surger. Assessment of factors affecting patients’ survivaly. Thyroid. 2008;18:615–624. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May M., Marusch F., Kaufmann O. Solitary renal cell carcinoma metastasis to the thyroid gland – a paradigm of metastasectomy? Chirurg. 2003;74(August (8)):768–774. doi: 10.1007/s00104-003-0674-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero Arenas M.A., Ryu H., Lee S. The role of thyroidectomy in metastatic disease to the thyroid gland. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014;21(February (2)):434–439. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood K., Vini L., Harmer C. Metastases to the thyroid gland: the Royal Marsden experience. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2004;30:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]