Abstract

Objective:

To describe and assess the effectiveness of a formal scholarly activity program for a highly integrated adult and pediatric neurology residency program.

Methods:

Starting in 2011, all graduating residents were required to complete at least one form of scholarly activity broadly defined to include peer-reviewed publications or presentations at scientific meetings of formally mentored projects. The scholarly activity program was administered by the associate residency training director and included an expanded journal club, guided mentorship, a required grand rounds platform presentation, and annual awards for the most scholarly and seminal research findings. We compared scholarly output and mentorship for residents graduating within a 5-year period following program initiation (2011–2015) and during the preceding 5-year preprogram baseline period (2005–2009).

Results:

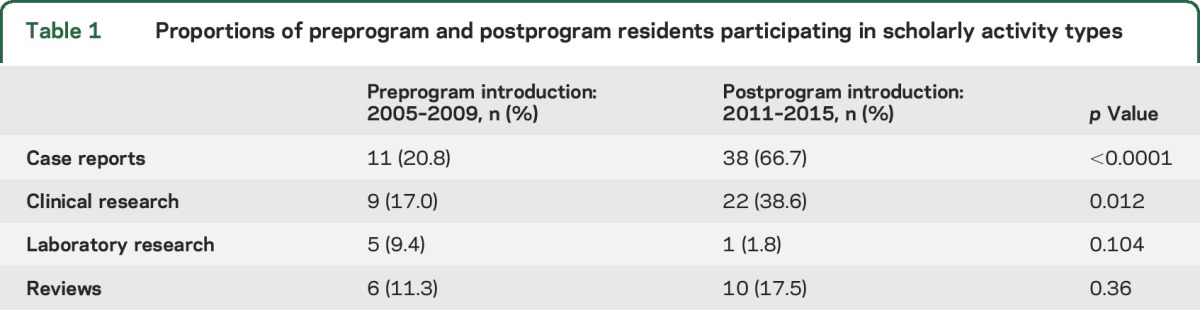

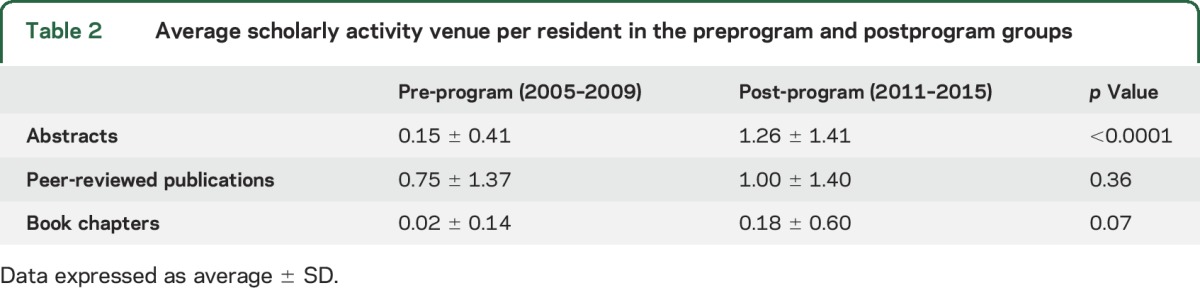

Participation in scholarship increased from the preprogram baseline (24 of 53 graduating residents, 45.3%) to the postprogram period (47 of 57 graduating residents, 82.1%, p < 0.0001). Total scholarly output more than doubled from 49 activities preprogram (0.92/resident) to 139 postprogram (2.44/resident, p = 0.0002). The proportions of resident participation increased for case reports (20.8% vs 66.7%, p < 0.0001) and clinical research (17.0% vs 38.6%, p = 0.012), but were similar for laboratory research and topical reviews. The mean activities per resident increased for published abstracts (0.15 ± 0.41 to 1.26 ± 1.41, p < 0.0001), manuscripts (0.75 ± 1.37 to 1.00 ± 1.40, p = 0.36), and book chapters (0.02 ± 0.14 to 0.18 ± 0.60, p = 0.07). Rates of resident participation as first authors increased from 30.2% to 71.9% (p < 0.0001). The number of individual faculty mentors increased from 36 (preprogram) to 44 (postprogram).

Conclusions:

Our multifaceted program, designed to enhance resident and faculty engagement in scholarship, was associated with increased academic output and an expanded mentorship pool. The program was particularly effective at encouraging presentations at scientific meetings. Longitudinal analysis will determine whether such a program portfolio inspires an increase in academic careers involving neuroscience-oriented research.

Although scholarly activity programs have been described in many graduate educational settings,1–7 they have not been examined in the setting of neurology residency programs. Increasing the scholarly participation of neurology residents is important to promote and inspire academic careers during training. It may also lead to better understanding of neurologic subspecialty content, technological modalities, and seminal advances in neuroscience research involving disease pathogenesis, risk stratification, differential diagnosis, earlier disease detection, and therapeutics. Scholarly activity participation may also enhance familiarity with research methodology, which can provide skills for a research career and judging the literature for studies relevant to neurologic practice.8

According to an expert consensus and a study of promotion criteria at academic medical institutions, core components of scholarly activity in graduate medical education should include discovery (advancing knowledge), integration (synthesizing knowledge), application (applying existing knowledge), and teaching (disseminating current medical knowledge).9 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) specifies examples of resident scholarship including “participation in research; publication and presentation at national and regional meetings; preparation and presentation of neurologic topics at educational conferences and programs; organization and administration of educational programs; and activity related to professional leadership. Peer-review activities and quality of care programming are additional examples of scholarship.”10

Scholarly activity is a requirement by the ACGME for all trainees participating in residency and fellowship programs.11 The core components feature the following guidelines: “The curriculum must advance residents' knowledge of the basic principles of research, including how research is conducted, evaluated, explained to patients, and applied to patient care. Residents should participate in scholarly activity. The sponsoring institution and program should allocate adequate educational resources to facilitate resident involvement in scholarly activities.”11 Scholarly activity participation is also a component of the Level 5 distinction in the disease-type (subspecialty) ACGME Neurology Milestones.12 Scholarly activity participation has been associated with greater satisfaction with residency training.13 Conversely, uncertainty about scholarly activity definitions and expectations during residency training may limit successful productivity.14 Participation in scholarly activity during residency training does not compromise clinical workflow and may be associated with superior clinical performance.15

We aimed to describe and assess the effectiveness of a formal scholarly activity program on the adult and pediatric neurology residency programs at our institution. We hypothesized that requiring scholarly activity by all residents in the context of a well-organized, administered program would lead to an increase in scholarly productivity within our training program. Specifically, we hypothesized that scholarly output and mentorship for residents graduating in 2011–2015 (postprogram) would exceed that of graduates in 2005–2009 (preprogram).

METHODS

Setting.

We studied the effect of a standardized scholarly activity program in the highly integrated adult and pediatric neurology residency programs at our institution, including Montefiore Medical Center and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in the Bronx, New York. Typically there are 9 positions per year in the adult program and 2 positions annually in the pediatric program. We initiated the program as an optional module for the graduating class of 2010 (phase-in), and it became a required program component beginning with the 2011 graduating class.

Program components.

The scholarly activity requirement stipulates that each resident must complete at least one form of scholarly activity. We defined scholarly activity as the production of peer-reviewed publications, presentations at scientific meetings, and authored book chapters/textbooks. Residents within our institution are required to participate in mentored activities and a substantial amount of the activity had to be performed during the 3 years of residency training. The program was formally administered by an associate residency training program director (M.S.R.). Components included an expanded journal club led by 2 investigators (S.R.H., R.B.L.) during which resident projects were discussed in workshop form, guided mentorship, a required grand rounds platform presentation before graduation, and the presentation of annual awards for the most scholarly and seminal research findings, as judged by a faculty awards committee. Residents were permitted (though not mandated) to use elective rotations supervised by their mentors to work on scholarly activity, though not at the expense of required clinical activities. Other components included referral of residents to appropriate faculty mentors, regular monitoring of research progress, support from the department chair for mentoring by faculty, and collaboration between subspecialty and general neurology divisions and well as other clinical and basic science departments.

Outcome assessment.

Data were compared for residents graduating in 2011–2015 (postprogram) vs graduates in 2005–2009 (preprogram). We compared the proportion of residents with scholarly output; the total output, the number, type, and presentation/publication venue of activities per resident; the number and proportion of residents as first authors of abstracts and publications; and the number of faculty mentors in comparison across the 2 epochs.

Data were directly abstracted from residency program administrative records into a Microsoft (Redmond, WA) Excel database. The data were summarized using descriptive statistics (percentages or means with SD). Categorical data were compared using χ2 or a 2-tailed Fisher exact test, and continuous data by an unpaired t test. Statistical significance was defined as a p value less than or equal to 0.05.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Our institutional review board approved this study as educational research not requiring informed consent.

RESULTS

Sample overview, participation, and total output.

Scholarly output from 110 residents was analyzed, including 90 adult and 20 pediatric neurology residents. Residents were divided into groups that completed training prior to program initiation (n = 53) and after the start of the program (n = 57). The proportion of residents participating in at least one scholarly activity was higher following program initiation in comparison with preprogram baseline (82.5% vs 45.3%, p < 0.0001). Of the 10 postprogram residents who did not generate scholarly output, the reasons included lack of participation or noncompliance with the program (n = 5, only 1 resident since 2012), work that was rejected for presentation or publication (n = 3), work that remained unfinished (n = 1), and work focused on a project preceding neurology residency (n = 1). The total scholarly output more than doubled, from 49 activities preprogram (0.92/resident) to 139 activities postprogram (2.44/resident, p = 0.0002).

Scholarly activity type and venue.

Resident participation significantly increased for case reports and clinical research, whereas there were no significant differences in dedicated laboratory research and production of scholarly reviews (table 1). Activity per resident increased significantly in abstracts presented at scientific meetings, with increases in peer-reviewed literature and book publications not reaching statistical significance (table 2).

Table 1.

Proportions of preprogram and postprogram residents participating in scholarly activity types

Table 2.

Average scholarly activity venue per resident in the preprogram and postprogram groups

Authorship and mentorship.

Proportions of residents who generated a first-authored abstract presentation or publication increased from 30.2% preprogram to 71.9% postprogram (p < 0.0001). The number of participating faculty mentors increased from 36 preprogram to 44 postprogram. Seventeen faculty members were mentors across both epochs. The mentor: resident ratio increased from 0.68 preprogram to 0.77 postprogram.

DISCUSSION

Our formalized scholarly activity program, designed to enhance resident and faculty engagement in scholarship, was associated with increased scholarly output and an expanded mentorship pool. The program was particularly effective at encouraging abstract presentations at scientific meetings. Resident participation in authoring case reports more than tripled and clinical research more than doubled.

It may be intuitive that requiring scholarly activity among trainees would lead to an increase among residents' scholarly output. However, our experience demonstrates that a modest investment in promoting scholarship dramatically increased the magnitude of scholarly participation and volume well beyond the minimal requirements of the program. The increased proportion of residents presenting abstracts at annual scientific meetings may have an important effect on trainee scholarly activity itself as a forum for improving the content and format of their presentation as well as an opportunity for academic collaboration. Other potential benefits for trainees presenting at scientific meetings include formal and informal networking opportunities for future educational and academic pursuits.

We also observed that the majority of postprogram residents participated in presenting or publishing case reports, many of whom also produced other forms of scholarly activity. Case reports uniquely provide scientific and educational value. They permit scientific discovery, including enhanced recognition and descriptions of clinical signs and diseases that may be rare, complex, or previously overlooked. They may also report unanticipated benefits and serious adverse effects of therapies, and allow for the study of disease mechanisms.16 The educational benefits of case report participation may include developing skills in observation, pattern recognition, hypothesis generation, organization, and writing.17 Successful case report writing and completion to abstract presentation or publication may potentially motivate trainees to pursue more complex forms of scholarly activity during their training and afterwards in their careers.

Administrative and organizational factors may contribute to the success of such an initiative. An associate residency program director administered our program, though other administration models have been described, including employing a postdoctoral researcher to assist faculty and trainees in translating clinical questions into tangible research projects, applying for regulatory approval, procuring funds, and networking.18 Programs lacking administrative resources or framework may look to resident-led scholarly activity initiatives for inspiration.19 Our residency program permitted elective time in research supervised by individual mentors. Other training programs have established formal research rotations that have also been associated with increasing scholarly output.20,21 We also utilized our journal club to workshop some residents' research projects. Though our program utilizes academic half-days, which have been employed in most Canadian neurology residency programs,22 we did not specifically use them to discuss scholarly activity planning or research methodology, but may do so in the future. Since the conclusion of this study, we have expanded this program to our fellowship training programs and have initiated a searchable, online departmental database of scholarly projects that can be browsed by trainees. One program has described an incentivized system for residents, where points generated by institutional review board approval, manuscript submission, and acceptance of research projects are converted to a monetary amount used for individual academic enrichment.23

Our study had limitations. It was difficult to account for the broad pattern of increasing scholarly output among trainees in the current era and the potential for increased scholarly activity production based on already developed preresidency skillsets. We did not account for research background prior to residency initiation as a predetermined variable. Though much of our department appreciated a major culture change with increasing resident and faculty scholarship, we did not formally assess for satisfaction by residents and mentors within our program. The denominator of total faculty members across the 2 periods was dynamic and a true proportion of faculty involvement could not be accurately assessed.

It may be difficult to generalize the results of our program to other training environments. Funding for residents to travel to scientific meetings to present their work may vary and may limit abstract submissions. Smaller neurology residency programs and departments may feature diminished faculty mentorship pools, administrative framework, and ability to provide assistance for trainees who wish to travel to scientific meetings and have their clinical responsibilities covered. We also grouped together adult and pediatric neurology residents in our program, who frequently share academic and clinical activities, though this may not be applicable to other programs. Finally, residents were not primary investigators in clinical trials as a part of our scholarly activity program, likely because of factors related to logistics and expertise. However, clinical trial design, execution, and interpretation are a fundamental aspect of any clinical research curriculum and may need special attention to complement our initiative.

Our study suggests that a scholarly activity program for a neurology residency may be feasible to implement and successful in producing a robust volume of presentations and publications. An unanswered but important question generated by our study is whether such a program portfolio inspires an increase in academic careers involving research.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Shari Archilla, residency program coordinator, for administrative assistance with this project; Isabelle Rapin, MD, who provided inspiration for the program; and all resident and faculty mentor participants.

GLOSSARY

- ACGME

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

Footnotes

Editorial, page 1302

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Robbins conceived and designed the study, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data, conducted the statistical analysis, and drafted, revised, and gave final approval to the manuscript. Drs. Haut, Lipton, Milstein, Ocava, Ballaban-Gil, Moshé, and Mehler provided critical input to study design and revised and gave final approval to the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURE

M. Robbins serves on the editorial board for Headache and is a section editor for Current Pain and Headache Reports. He has received book royalties for Headache (Neurology in Practice series) from Wiley. S. Haut serves on the editorial board for Epilepsy and Behavior and is a consultant for Acorda, Upsher Smith, and Neurelis. R. Lipton is the Edwin S. Lowe Professor of Neurology. He receives research support from the NIH: PO1 AG003949 (program director), RO1 AG038651-01A1 (PI, Einstein), U10 NS077308-01 (PI), RO1 NS07792503 (investigator), RO1 AG042595-01A1 (investigator), RO1 NS08243203 (investigator), and K23 NS096107-01 (mentor). He also receives support from the Migraine Research Foundation and the National Headache Foundation. He serves on the editorial board of Neurology® and as senior advisor to Headache. He has reviewed for the NIA and NINDS; holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics; and serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received honoraria from Alder, Allergan, American Headache Society, Amgen, Autonomic Technologies, Avanir, Boston Scientific, Colucid, Dr. Reddy's, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, Glaxo, Inc., Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Teva, and Vedanta. He receives royalties from Wolff's Headache, 8th Edition, Oxford Press University, 2009, and Informa. M. Milstein has received book royalties from Elsevier. L. Ocava and K. Ballaban-Gil report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. S. Moshé is the Charles Frost Chair in Neurosurgery and Neurology and funded by grants from NIH NS43209, CURE, US Department of Defense, the Heffer Family, the Segal Family Foundations, and the Abbe Goldstein/Joshua Lurie and Laurie Marsh/Dan Levitz families. He serves as Associate Editor of Neurobiology of Disease and is on the editorial board of Epileptic Disorders, Brain and Development, Pediatric Neurology, and Physiologic Research. He receives annual compensation from Elsevier for his work as Associate Editor on Neurobiology of Disease and royalties from 2 books he coedited. He received a consultant's fee from Eisai and UCB. M. Mehler is the Alpern Family Foundation Professor and University Chair of the Saul R. Korey Department of Neurology and funded by grants from the NIH (NS096144, NS071571, and U10NS086531). Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amrhein TJ, Tabesh A, Collins HR, Gordon LL, Helpern JA, Jensen JH. Instituting a radiology residency scholarly activity program. Educ Health 2015;28:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geyer BC, Kaji AH, Katz ED, Jones AE, Bebarta VS. A national evaluation of the scholarly activity requirement in residency programs: a survey of emergency medicine program directors. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:1337–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abramson EL, Naifeh MM, Stevenson MD, et al. Research training among pediatric residency programs: a national assessment. Acad Med 2014;89:1674–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanmugalingam A, Ferreria SG, Norman RM, Vasudev K. Research experience in psychiatry residency programs across Canada: current status. Can J Psychiatry 2014;59:586–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner RF Jr, Raimer SS, Kelly BC. Incorporating resident research into the dermatology residency program. Adv Med Educ Pract 2013;4:77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine RB, Hebert RS, Wright SM. Resident research and scholarly activity in internal medicine residency training programs. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins L, Bostrom M, Marx R, Roberts T, Sculco TP. Restructuring the orthopedic resident research curriculum to increase scholarly activity. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5:646–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leira EC, Granner MA, Torner JC, Callison RC, Adams HP Jr. Education Research: the challenge of incorporating formal research methodology training in a neurology residency. Neurology 2008;70:e79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grady EC, Roise A, Barr D, et al. Defining scholarly activity in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ 2012;4:558–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Frequently asked questions: neurology review committee for neurology ACGME. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/portals/0/pdfs/faq/180_neurology_faqs.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accredited programs and sponsoring institutions. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Specialty-specific%20Requirement%20Topics/DIO-Scholarly_Activity_Resident-Fellow.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- 12.Lewis SL, Jozefowicz RF, Kilgore S, Dhand A, Edgar L. Introducing the neurology milestones. J Grad Med Educ 2014;6:102–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi O, Ohde S, Jacobs JL, Tokuda Y, Omata F, Fukui T. Residents' experience of scholarly activities is associated with higher satisfaction with residency training. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:716–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledford CJ, Seehusen DA, Villagran MM, Cafferty LA, Childress MA. Resident scholarship expectations and experiences: sources of uncertainty as barriers to success. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5:564–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seaburg LA, Wang AT, West CP, et al. Associations between resident physicians' publications and clinical performance during residency training. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandenbroucke JP. In defense of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Packer CD, Katz RB, Iacopetti CL, Krimmel JD, Singh MK. A case suspended in time: the educational value of case reports. Acad Med Epub 2016 Apr 19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Penrose LL, Yeomans ER, Praderio C, Prien SD. An incremental approach to improving scholarly activity. J Grad Med Educ 2012;4:496–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoedebecke K, Rerucha C, Runser L. Increase in residency scholarly activity as a result of resident-led initiative. Fam Med 2014;46:288–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanna B, Deng C, Erickson SN, Valerio JA, Dimitrov V, Soni A. The research rotation: competency-based structured and novel approach to research training of internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ 2006;6:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstantakos EK, Laughlin RT, Markert RJ, Crosby LA. Assuring the research competence of orthopedic graduates. J Surg Educ 2010;67:129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalk C. The academic half-day in Canadian neurology residency programs. Can J Neurol Sci 2004;31:511–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang CW, Mills JC. Effects of a reward system on resident research productivity. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;139:1285–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.