Significance

This report gives empirical evidence indicating that chemoreception of volatile/odorant lipophilic compounds, almost insoluble in water, can occur in aquatic environments, by means of “tactile” forms of olfaction. This thesis has been proved by exploring the defensive role of terpenes isolated from benthic invertebrates. The isolated metabolites were found to act both as defensive toxic weapons and as olfactory signals. In addition, the most abundant compound induced avoidance learning in crustaceans and fish that experienced postingestive negative effects.

Keywords: marine chemical ecology, chemical defense, olfactory aposematism, avoidance learning, volatile terpenes

Abstract

Olfaction is considered a distance sense; hence, aquatic olfaction is thought to be mediated only by molecules dissolved in water. Here, we challenge this view by showing that shrimp and fish can recognize the presence of hydrophobic olfactory cues by a “tactile” form of chemoreception. We found that odiferous furanosesquiterpenes protect both the Mediterranean octocoral Maasella edwardsi and its specialist predator, the nudibranch gastropod Tritonia striata, from potential predators. Food treated with the terpenes elicited avoidance responses in the cooccurring shrimp Palaemon elegans. Rejection was also induced in the shrimp by the memory recall of postingestive aversive effects (vomiting), evoked by repeatedly touching the food with chemosensory mouthparts. Consistent with their emetic properties once ingested, the compounds were highly toxic to brine shrimp. Further experiments on the zebrafish showed that this vertebrate aquatic model also avoids food treated with one of the terpenes, after having experienced gastrointestinal malaise. The fish refused the food after repeatedly touching it with their mouths. The compounds studied thus act simultaneously as (i) toxins, (ii) avoidance-learning inducers, and (iii) aposematic odorant cues. Although they produce a characteristic smell when exposed to air, the compounds are detected by direct contact with the emitter in aquatic environments and are perceived at high doses that are not compatible with their transport in water. The mouthparts of both the shrimp and the fish have thus been shown to act as “aquatic noses,” supporting a substantial revision of the current definition of the chemical senses based upon spatial criteria.

Traditionally, the sense of smell has been regarded as a distance sense (like vision), whereas the sense of taste has been treated as a contact sense (like touch). This classification of the chemical senses (olfaction and gustation) based on their spatial range persists in contemporary literature. Accordingly, biomolecules smaller than ∼300 Da, which can be transported through air, and which finally bind to odorant receptors expressed in olfactory neurons, are generally considered odorant molecules. Conversely, the molecules sensed by taste have to be in solution and in contact with the receptor (1). However, the claim that “only olfaction can provide information on the identity of the water mass encountered” by marine organisms (2) implies that water-soluble compounds, which are typically “tasted” by the tongues of terrestrial animals, act as olfactory cues in aquatic environments. Consequently, it may be asked how typical odorant molecules such as small terpenes from plants and marine sponges that combine high volatility in air with insolubility in water can produce olfactory sensations in marine organisms, thereby giving protection from predators and cues to finding food and mates.

The distinction between olfaction and gustation based upon spatial criteria is prevalent in the literature on aquatic chemical communication (3). However, this differentiation has been reevaluated in a recent perspective article (4). Therein, a substantial revision of the traditional classification of the chemical senses has been proposed based on the cues actually involved in chemical sensations rather than upon spatial criteria. In the present study, we provide empirical support for this thesis by challenging the notion that the aquatic sense of smell cannot be mediated by hydrophobic and airborne olfactory molecules.

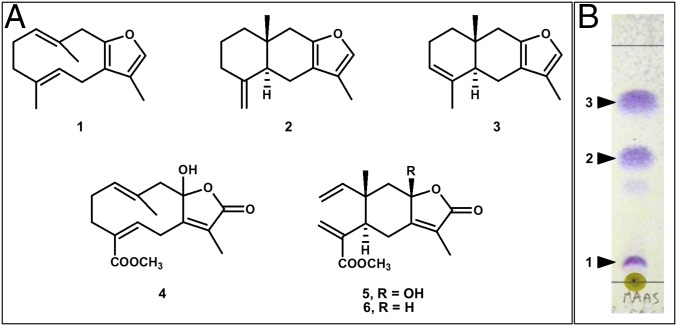

We report the finding of furanosesquiterpenes isofuranodiene (1), (−)-atractylon (2), and (−)-isoatractylon (3) (Fig. 1) in Maasella edwardsi (de Lacaze-Duthiers, 1888) (Fig. 2 A and C), a Mediterranean octocoral (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Alcyonacea) from which the related sesquiterpene lactones 4–6 (Fig. 1) had previously been reported (5). The same compounds were also found in the nudibranch Tritonia striata Haefelfinger, 1963 (Fig. 2 B−D), a mollusk (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Nudibranchia) that usually seeks refuge among the pedicels of M. edwardsi. Compounds 1–3 act as typical olfactory cues, showing characteristic odors when exposed to air. It is noteworthy that isofuranodiene (1), often misleadingly called furanodiene (6), also occurs in marine organisms (7–12), but it is better known for contributing to the smell of several terrestrial flowering plants, including myrrh and white turmeric, some of which are commonly used as food additives and fragrance ingredients (6). Furthermore, atractylon (2), which has also been found in marine animals (10), is a major odor-active compound from plants (13, 14). In contrast, the volatile compound 3 has only been reported from the marine cnidarian Dasystenella acanthina (Wright & Studer, 1889) as the (+)-enantiomer (7). Isofuranodiene and atractylon are also known for their pharmacological properties. In particular, isofuranodiene shows anticancer and antiangiogenic activity (15–22), as well as analgesic properties when acting on brain opioid receptors (23). Atractylon exhibits antiinflammatory activity (24), cytotoxicity against various human cancer cell lines (25, 26), acaricidal activity (27), and inhibition of Na+, K+-ATPase activity (28). However, previous attempts to explore the natural function of compound 1 in the Antarctic gorgonian D. acanthina have failed to recognize its feeding deterrent properties against the goldfish Carassius auratus (Linnaeus, 1758), although the compound showed toxicity to the mosquitofish Gambusia affinis (Baird & Girard, 1853) (7). Similar results have been obtained for the (+) enantiomer of compound 3, supporting the idea that these volatile compounds do not induce olfactory-mediated recognition and avoidance in fish, although they are icthyotoxic. This point is a critical one in marine chemical ecology because previous studies have not clearly shown that volatile compounds can deter predation in marine environments (29, 30).

Fig. 1.

Metabolites from M. edwardsi. (A) Chemical structures of isofuranodiene (1), atractylon (2), isoatractylon (3), edwardsiolide A (4), edwardsiolide B (5), and edwardsiolide C (6). (B) Detail of the analytical AgNO3-treated TLC plate revealing the occurrence of bands corresponding to furanosesquiterpenes 1–3 in the crude diethyl ether extract of M. edwardsi (MAAS), after spraying with Ehrlich’s reagent. Eluent is n-hexane/diethylether 95:5.

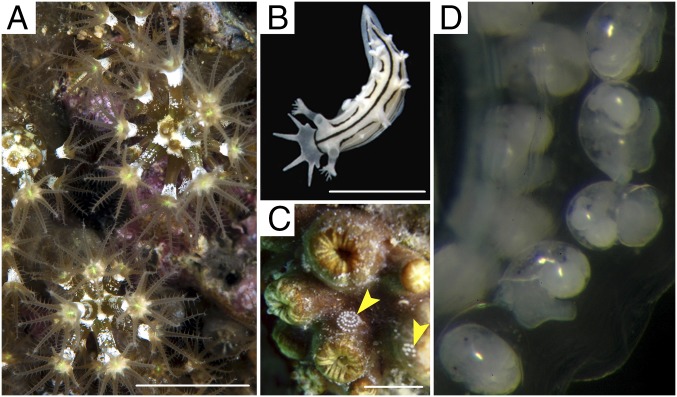

Fig. 2.

Studied animals. (A) M. edwardsi; (B) T. striata; (C) yellow arrows indicate egg masses of T. striata on M. edwarsdi (in retracted state). (Scale bars, 5 mm.) (D) T. striata larvae inside its egg mass.

In this report, recognition and avoidance of hydrophobic odors in water has been studied by evaluating the ecological role of the compounds detected in M. edwardsi and T. striata. The finding of the nudibranch’s egg masses in spirals on the surface of coral colonies in the field (Fig. 2C) suggested a trophic relationship between the two marine benthic invertebrates, and a possible defensive role of compounds 1–3. Nudibranchs are known to lay their egg masses on or near the prey they feed on (mainly sponges and cnidarians) and from which they obtain defensive compounds. A specifically designed aquarium system (Fig. S1A) allowed us (i) to follow the life cycle of M. edwardsi colonies collected in the archipelago of Li Galli in Southern Italy (Fig. S1B), (ii) to observe directly the nudibranch feeding on the octocoral tissues and larvae, and (iii) to photograph the larvae (veligers) of T. striata inside an egg mass laid in captivity (Fig. 2D). The feeding deterrence activity of compounds 1–3 was evaluated against the cooccurring generalist shrimp Palaemon elegans Rathke, 1837, following an approach already used to assess the palatability of other bioactive metabolites (31), including marine furanosesquiterpenes (32, 33). Like other palaemonid species (34, 35), P. elegans is suitable for evaluations of this kind, which require a good view of the ingested food in the digestive system (31). Given that decapod crustaceans exhibit complex learning ability (36, 37), the possibility that the shrimp learn to avoid the compounds after experiencing aversive olfactory stimuli was also considered. Subsequently, we conducted additional behavioral assays on the zebrafish (Danio rerio Hamilton, 1822). Although this animal model is not of direct ecological relevance to the system under investigation, it provided additional information about the possible effects of compound 3 on aquatic lower vertebrates. General toxicity of the compounds was estimated by using the brine shrimp Artemia salina (Linnaeus, 1758), allowing us to provide information about the level of toxicity within a recognized scale of toxicity (38).

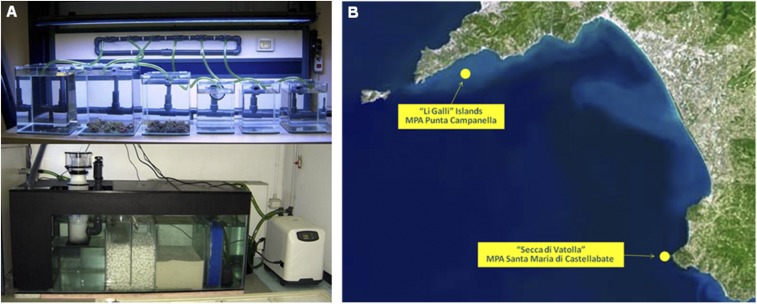

Fig. S1.

(A) The modular system of tanks (Upper), and the filtering sump (Lower). (B) The sampling sites along the coast of the Campania region (Italy).

Results

Purification, Identification, and Quantification of the Furanosesquiterpenes.

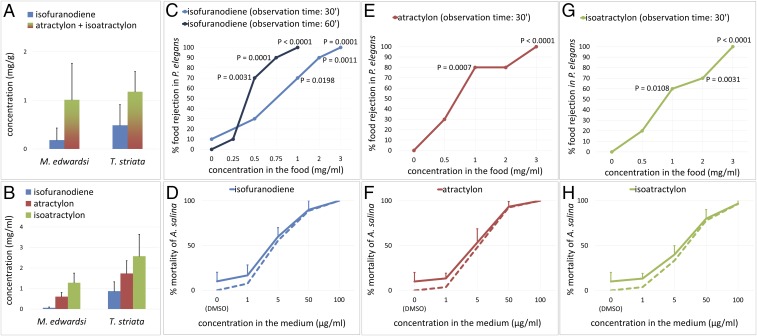

Isofuranodiene (1), (−)-atractylon (2), and (−)-isoatractylon (3) were extracted and isolated from M. edwardsi, and identified by comparison of spectroscopic data with the literature (7, 10, 13). Compounds 2 and 3 displayed negative optical rotation values (2: [α]D = −78, c 0.15, hexane; 3: [α]D = −128, c 0.22, hexane), opposite in sign to those previously reported (7, 13). The characteristic spicy and woody odors of the three isolated furanoterpenes, which can be distinguished by their slightly different olfactory nuances, were clearly detected during purification, revealing the presence of the compounds in the chromatographic fractions even before visualizing them on TLC plates (Fig. 1B). A quantification of the volatile metabolites in the crude extracts of three individuals of both M. edwardsi and T. striata was carried out by GC-MS. Although, under the conditions used, we were not able to discriminate between isomeric compounds 2 and 3, owing to their similar chromatographic behavior, the total amount of the three compounds was apparently higher in the mollusk than in its prey (Fig. 3A). The mixture of furanosesquiterpenes 1–3 was further detected by TLC in a sample of the mucus secreted by M. edwardsi following sampling with a cotton swab on the surface of a living colony. Furthermore, the presence of isofuranodiene (1) was ascertained by 1H NMR in the extract from a few planulae of M. edwardsi, although the low amount of extracted material and the volatility of the furanosesquiterpenes prevented the identification of all of the other metabolites present in the extract and their realistic quantification. Subsequently, before proceeding with the evaluation of the biological activity of the compounds, we evaluated the natural volumetric concentrations (in milligrams per milliliter) of each compound in three whole small colonies of M. edwardsi, and in three individuals of T. striata by quantitative 1H NMR. This analysis showed that (−)-isoatractylon (3) was the major sesquiterpene in both animals (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Quantification of the metabolites and evaluation of their biological activity. (A and B) Concentration of compounds 1–3 quantified by (A) GC-MS and (B) 1H NMR. Values shown are means and SDs from triplicate extractions from different colonies/individuals. (C, E, and G) Feeding deterrence dose–response curves against P. elegans. The significant differences were evaluated using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test (n = 10 for each tested concentration, α = 0.05). (D, F, and H) Dose–response curves of toxicity to A. salina. The results are shown as the means and SDs of triplicate wells. Because deaths also occurred in the control (vehicle DMSO only), percentages of deaths were corrected by using Abbott’s formula (dashed lines).

Feeding Deterrence Activity.

Compounds 1–3 were then tested for their activity as feeding deterrents against P. elegans. The presence of a red spot visible by transparency in the gastric mill and the stomach of the shrimp was considered as acceptance of food (Movie S1), and the absence of the spot gave a rejection response (Movie S2). As summarized in Fig. 3 C, E, and G, the purified compounds were all significantly active, starting from a minimum effective dose of 1.0 mg/mL. It is noteworthy that, in some cases, the treated food induced vomiting in the shrimp when ingested; vomiting was always preceded by spasmodic contractions of the stomach, which were easily observable because of the transparency of the animals (Movie S3). The regurgitations occurring within an observation time of 30 min were treated as cases of food rejection, contributing to the dose–response curves, whereas emetic events were not noticed in shrimp that had accepted the control food, even upon prolonging the observation time to 1 h. Conversely, the incidence of vomiting increased with the observation time, occurring after a delay varying from 5 min to 50 min. Accordingly, assays carried out on isofuranodiene (1), and with the observation time extended to 60 min, revealed significant food rejection at a concentration as low as 0.5 mg/mL, due to the occurrence of delayed regurgitation events, which had not been observed using observation intervals of 30 min in the previous experiment (Fig. 3C).

Avoidance Learning.

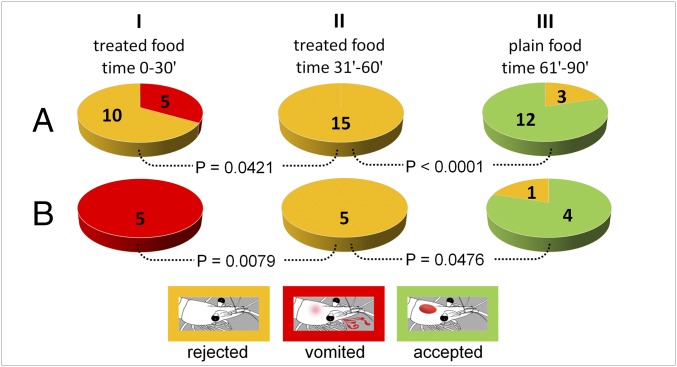

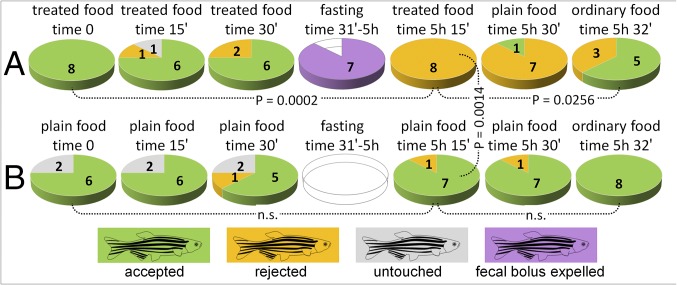

The role of regurgitation events in avoidance learning was next evaluated by offering food containing 4 mg/mL of (−)-isoatractylon (3) to a larger sample of shrimp after 2 d fasting (n = 15) (Fig. 4A). In the first treatment, 10 individuals did not accept the food, whereas the remaining 5 individuals ingested the food but then vomited it within 30 min (Fig. 4A, step I). In the next administration (Fig. 4A, step II), none of the shrimp accepted the treated food. Finally, untreated control food was significantly (P < 0.0001) accepted by the shrimp during the last step (Fig. 4A, step III). It is noteworthy that all shrimp that had previously experienced emetic events significantly (P = 0.0079) rejected the treated food during a subsequent administration, having touched it, while significantly (P = 0.0476) accepting nontreated food during the last experimental step (Fig. 4B). Different responses were observed using the zebrafish as a vertebrate model (Fig. 5). When food treated with (−)-isoatractylon (3) (4.0 mg/mL) was offered to the fish, after 1 d of fasting, the food pellets were accepted during three subsequent administrations at 15-min intervals, but apparently undigested food was found at the bottom of most of the tanks within 5 h after the beginning of the experiment. Analysis of recorded videos in slow motion led us to observe that such material was not regurgitated/vomited food, but instead was a sort of undigested fecal bolus (different from the excrement normally produced by zebrafish). The fish completely rejected the treated food in a subsequent administration (Fig. 5A, time 5 h 15 min). The memory recall was induced after the fish repeatedly took the food into their oral cavity before definitely refusing it (Movie S4). However, fish also avoided control plain food offered 15 min later; but just 2 min later, they accepted the commercial pellets (Fig. 5A, time 5 h 32 min).

Fig. 4.

Avoidance learning assay on P. elegans. Recorded responses: green, food acceptance (as shown in Movie S1); yellow, food rejection after touching (as shown in Movie S2); and red, vomiting (as shown in Movie S3). (A) Response from the whole sample (n = 15) to food containing (−)-isoatractylon at a concentration of 4.0 mg/mL (step I, step II) and untreated plain food (step III). (B) Response from the subgroup of the vomiting shrimp (n = 5). P values are calculated using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test (α = 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Avoidance learning in the zebrafish. Recorded responses: green, food acceptance; yellow, food rejection after touching (as shown in Movie S4); gray, rejection without touching; and violet, evacuation of fecal bolus. (A) Time-dependent responses to food containing (−)-isoatractylon (3) followed by responses to nontreated plain food, and to commercial granular pellets (ordinary food). (B) Responses to plain food. P values are calculated using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test (n.s. = not significant; n = 8; α = 0.05).

Brine Shrimp Toxicity Assay.

The assay revealed high toxicity in vivo of compounds 1–3 against A. salina, with LC50 < 50 µg/mL (Fig. 3 D, F, and H), whereas a dose-dependent gradual attenuation of the brine shrimp movements was also noticed under the action of the assayed compounds.

Discussion

It is believed that the chemosensory world of marine organisms is limited to water-soluble, and does not include volatile, chemical stimuli (39, 40). The present report contradicts this preconceived idea by showing that aquatic animals also sense volatile biomolecules when they face the vital problem of determining food palatability.

The first phase of the study focused on the isolation of the metabolites and on the problem of a possible interference by chemical transformations that can confound assay readouts when working with labile compounds. The odorant compounds isofuranodiene (1), (−)-atractylon (2), and (−)-isoatractylon (3) have been found in adult colonies of M. edwardsi collected along Italian coasts, whereas germacrane and elemane class sesquiterpenoid lactones, previously isolated from M. edwardsi from Tunisia (5) (Fig. 2A), were not detected. This discrepancy could reflect either geographical variations in the chemical composition of the octocoral or a degradation of the furanosesquiterpenes 1–3, possibly due to postcollection oxidation or to the use of methanol as the extraction solvent. Furans are known to be susceptible to oxidative processes that can lead to five-membered lactones. They undergo photooxygenation reactions under natural or fluorescent light and in solution in methanol (41, 42). In the present work, we also avoided the use of chloroform, which induces rapid transformations of the compounds. Instead, acetone and benzene were used for the extraction, and deuterated benzene (benzene-d6) was used to record the NMR spectra. Once the compounds were identified, GC-MS and 1H NMR studies proved, chemically, the prey−predator trophic relationship between the octocoral and the mollusk. Compounds 1–3 were detected in both the prey and the predator, and the presence of isofuranodiene (1) was also ascertained by 1H NMR in the extract from the larvae (planulae) of M. edwardsi that the mollusk actively eats after the octocoral spawns (Movie S5). The higher concentration of compounds 1–3 in the mollusk than in the octocoral supports bioaccumulation farther up the food chain. Moreover, the most abundant furanoterpene in both organisms was compound 3, which also was particularly abundant in T. striata.

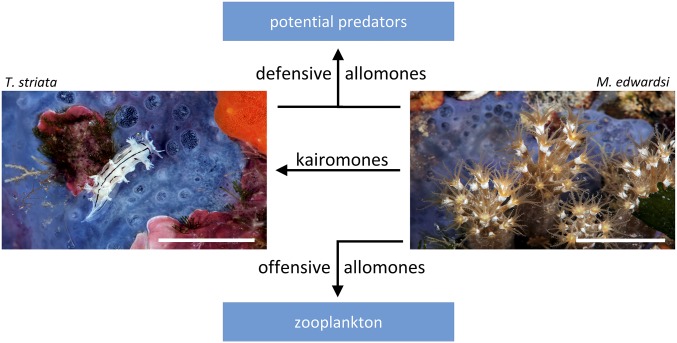

Among a wide range of potential predators of both M. edwardsi and T. striata, we selected the cooccurring generalist shrimp P. elegans for the chemoecological assays. The transparency of this shrimp allows an easy visualization of the food once ingested (Movie S1). This crustacean can be maintained for a long time in a small volume of seawater, allowing us easily to perform series of individual replicates in a chemical laboratory, where it is actually possible also to control the state of the compounds immediately before the experiments. Dose–response curves provided information about the thresholds of activity of compounds 1–3 independently from the levels of the metabolites measured in the samples, thus describing the change in effect on shrimp caused by differing levels of exposure to compounds 1–3, after a certain exposure time. By setting an observation interval of 30 min, and considering emetic events as cases of food rejection, all compounds were significantly active as feeding deterrents starting from a concentration of 1 mg/mL, and reaching 100% rejection at a concentration of 3 mg/mL. Although the natural concentrations of these unstable, volatile compounds may have been underestimated, and despite the fact that a small loss of compounds was likely to occur during artificial food preparation, our measurements indicated that the most abundant compound 3 was present in both studied animals in sufficient amounts to induce food rejection and/or vomiting by potential predators (Fig. 3 A and B). However, in the case of compound 1, extension of the observation interval to 60 min allowed the detection of delayed regurgitation events, revealing significant rejection even at concentrations as low as 0.5 mg/mL (Fig. 3C). Further experiments carried out on (−)-isoatractylon (3) led us to observe that the shrimp that swallowed the treated food, and then vomited it, completely avoided the treated food in a subsequent administration, but only after having repeatedly touched it. Consequently, the protective effect seems to have been achieved both through the induction of a basic olfactory aversion to compounds 3 and by the olfactory recall of postingestive toxic effects. General toxicity measurements carried out by A. salina lethality assays revealed high toxicity for compounds 1–3 (Fig. 3 D, F, and H). However, the toxic doses of compounds 1–3 against brine shrimp were significantly lower than the doses required to deter P. elegans from feeding, or to induce vomiting. This finding can be explained by taking into account that the exposure route, as well as the physicochemical properties of the involved compounds, is extremely important in determining toxicity. In the tests with A. salina, compounds 1–3 were conveyed in water using DMSO. Under such conditions, the compounds act like waterborne molecules and can also directly reach the respiratory system of the brine shrimp. Conversely, in the feeding assays on P. elegans, the lipophilic molecules have a very low propensity to diffuse in water, due to hydrophobic interactions. Consequently, chemoreception takes place by touching the food with the chemosensory mouthparts (see Movie S2), whereas uptake of the products can occur only after ingestion (see Movie S1). Subsequently, the compounds can be poorly absorbed or immediately detoxified by the digestive system, and vomiting also helps to avoid food poisoning (see Movie S3). However, the toxicity of compounds 1–3 to brine shrimp is further suggestive of an involvement in mechanisms of predation as part of the alimentary strategies of M. edwardsi in nature, helping to capture dietary zooplanktonic crustaceans (e.g., copepods) that come into contact with the mucus layer covering the octocoral, and which lose their ability to escape, owing to intoxication. Obviously M. edwardsi does not use DMSO as a cosolvent to dissolve the lipophilic compounds in water, but when small planktonic organisms come into contact with the octocoral, they actually remain embedded in the secretions that cover the octocoral, like flies on flypaper. An attenuation of the movements has been also noticed in A. salina under the action of the assayed compounds, and the furanosesquiterpenes have also been detected in the mucus that covers the surface of M. edwardsi and first comes in contact with its zooplanktonic prey. Again, this finding implies that the relative insolubility of the compounds in water contributes to ensuring adequate local concentrations, allowing their effectiveness in both predation and defense (Fig. 6). The furanosesquiterpenes of M. edwardsi and T. striata thus convey different messages depending on the different receiver organisms. They can act as both defensive warning messages and toxic chemical weapons if directed to potential predators or prey, but they evidently do not deter T. striata (the specialist predator) from feeding. On the contrary, in the latter case, the compounds possibly indicate a food source for the receiver (acting as kairomones), which is able to handle and reuse them in self-defense. Our observation of T. striata actively feeding on M. edwardsi and its larvae in aquarium strongly supports this hypothesis. Moreover, the chemical message is stronger in T. striata, which accumulates higher levels of the dietary compounds 1–3, and it is reinforced by a conspicuous coloration (white color striped with black lines) that is reminiscent of the aposematic pattern of striped skunks and their famous defensive scent. According to the model developed by Gohli and Högstedt (43), the visual aposematic signal of T. striata, which is easily detectable by potential predators with well-developed visual systems, could have evolved in the mollusk, favored by the strongest message conveyed by high levels of protective olfactory chemicals.

Fig. 6.

Proposed multiple ecological roles of furanosesquiterpenes 1–3. (Scale bars, 10 mm.)

Aposematism describes the association between easily detectable conspicuous signals (visual, olfactory, and acoustic) and unprofitability (33, 44). However, as is true for plants that simultaneously use visual and olfactory aposematic signals for animal attraction (45), T. striata uses double signaling, but for defensive purposes, whereas M. edwardsi relies on olfactory aposematism, which may provide protection from a wider range of predators, including those lacking efficient visual systems (35). It is worth underlining here that compounds 1–3 induce both toxic and olfactory-guided food avoidance effects and, differently from the cases considered by Eisner and Grant (44), they function as conditioned olfactory stimuli for indicating their own intrinsic toxicity and unprofitability. However, odors that themselves are noxious have already been described in insects (46). Although the experiments on the zebrafish failed to recognize vomiting events in this vertebrate animal model, food treated with compound 3, once ingested, induced a sort of gastrointestinal malaise in the fish, which led to the evacuation of an apparently undigested fecal bolus, and to subsequent avoidance learning. Differently from the shrimp, however, the zebrafish seemed to learn from a wider range of sensory signals associated with the negative postingestive toxic experience, possibly including not only visual and chemical senses but also the perception of the consistency of the food. In P. elegans, instead, olfaction seems to be the main way to avoid dangerous foods. However, in both animals, the memory recall and the consequent food rejection were always induced after touching the food (as shown in Movies S2 and S4). The need to repeatedly touch the food, before deciding whether to swallow or refuse it, is consistent with the extremely short range of action of insoluble olfactory cues in the aquatic environment. Accordingly, the observations made in this work call for some reflections on the range of effectiveness of volatile and hydrophobic olfactory cues in terrestrial and marine environments. In particular, to say that the odiferous isofuranodiene (1), a major constituent of the extract of terrestrial plants, can act in long-distance signaling on land is an evident truism. Conversely, our results on P. elegans show that the minimum concentrations at which compounds 1–3 produce significant effects on alimentary behavior are significantly higher than those allowing terrestrial animals to recognize and avoid an unpleasant food. This fact, combined with the extremely low number of genes encoding for odorant receptors in marine fish compared with terrestrial tetrapods (47), and the very low solubility in water of compounds 1, 2, and 3 [estimated to be about 0.0001, 0.0004, and 0.0005 mg/mL, respectively (48)], makes the feeding deterrent action of the compounds at a distance in the marine environment implausible. Although solubility in saline water should even be lower than the estimated solubility in fresh water, the estimated concentrations of saturated solutions with compounds 1–3 are three orders of magnitude lower than the experimentally determined minimum concentrations in artificially prepared food able to deter P. elegans from feeding. Accordingly, during the experiments, the shrimp were hungry and actively searching for food, repeatedly “smelling” the potential sources of food by touching it with their mouthpart chemosensors. Even after having experienced the negative experience of vomiting, the shrimp needed to touch the food before deciding whether to accept or reject it, evidently because they were unable to detect the unpleasant smell dissolved in water. These aquatic animals are thus provided with a sense of smell that can be mediated by stimulatory molecules that are not in solution. Olfactory biomolecules, such as compounds 1–3, which cannot be transported at effective doses in an aquatic medium, can instead be perceived at high doses by direct contact with the emitter (as shown in Movies S2 and S4). This is a fact that we must no longer ignore, even if it will require a substantial revision of the current definition of the chemical senses based on their spatial range.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Colonies of M. edwardsi and 10 individuals of T. striata were sampled by scuba diving along the coast of the Campania region (southern Italy) in shallow rocky sites at Secca di Vatolla and in the archipelago of Li Galli, with the permission of the Marine Protected Areas of Santa Maria di Castellabate and Punta Campanella, respectively (Fig. S1B). The samples were transported to the laboratory in cooled seawater and then frozen (−20 °C) to prevent degradation of metabolites. Further colonies/individuals of both animals were reared in aquarium (Fig. S1A) as described in SI Materials and Methods, to observe the spawned eggs (Fig. S2A), the fully developed swimming/crawling planulae (Fig. S2 B and C), and T. striata engulfing the planulae (Movie S5).

Fig. S2.

(A) M. edwardsi (surface brooding). Retracted pedicels covered with eggs. (B) Fully developed planula. (Scale bar, 1 mm.) (C) Contracted planula.

Chemical Study.

Extraction, purification, and identification of compounds 1–3 from M. edwardsi were carried out as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. The acetone extract of the mucus secreted by M. edwardsi, collected with a cotton swab on the surface of a living colony in aquarium, was analyzed by AgNO3-SiO2 TLC, and 20 larvae (planulae) of M. edwardsi collected in the aquarium 7 d to 10 d after spawning were directly extracted with benzene-d6 and analyzed by 1H NMR.

Quantification of the Metabolites.

Natural concentrations of metabolites 1–3 in T. striata and M. edwardsi were estimated by quantitative GC-MS and 1H NMR analysis by using dimethylfumarate as an internal standard, as reported in SI Materials and Methods.

Feeding Deterrence Assay.

The compounds were tested for their feeding deterrence activity against a shrimp, P. elegans, which is widely distributed in the Mediterranean Sea and along the European coast of the Atlantic (49). Artificial food was prepared as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. The shrimp were collected along the coast of Pozzuoli, Italy, and habituated to the control food in captivity for a week before experiments. After 2 d of fasting, 10 randomly picked shrimp were assayed as a series of individual replicates for each concentration and the control (n = 10 for each series). Shrimp were placed individually into 500-mL plastic beakers filled with 300 mL of seawater. A colored food strip was given to each shrimp, and shrimp were not reused. For each tested compound, control and treatments were carried out in parallel. The presence of a red spot, visible by transparency in the gastric mill and the stomach of the shrimp, was considered as acceptance of food, and the absence of the spot gave a rejection response. The regurgitation events that occurred within the observation time were considered as cases of food rejection. Statistical analysis between treatments and controls was performed using the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, with α = 0.05.

Avoidance Learning Assays.

Fifteen shrimp (P. elegans) habituated to the control food in captivity were fasted for 2 d. Subsequently, food pellets treated with compound 3 (4 mg/mL) were offered to the shrimp in a series of individual replicates. After 30 min, food residuals were removed from the bottom of the beakers, and food treated with compound 3 was given to all shrimp again. Finally, 30 min later, control food was given to all shrimp. Percentages of rejection, acceptance, and vomiting were recorded for each step, and differences between treatment and control were evaluated using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test, with α = 0.05. Compound 3 was also tested for its palatability at a concentration of 4 mg/mL against the zebrafish (D. rerio), after 1 d of fasting. The experiments were conducted in the animal facility of the Department of Biology, Federico II University of Napoli (Italy), under animal handling and experimental procedures approved by the University ethics committee on animal experiments (ethical permit protocol 2013/0096061). The artificial food was prepared as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. Eight randomly picked zebrafish were assayed as a series of individual replicates. Fish were placed individually into 1,000-mL plastic containers filled with 600 mL of water. Treated food was offered to each fish in three subsequent administrations. Subsequently, after an interval of 5 h, during which the majority of individuals had expelled a fecal bolus, treated food was offered again to each individual. Finally, nontreated pellets and commercial granular food were given to the fish. The time-dependent response to nontreated control food was evaluated on a further series of eight fish.

Brine Shrimp Toxicity Assay.

The toxicity of compounds 1–3, dissolved in DMSO, was evaluated using the brine shrimp (A. salina) lethality test, by following the reported toxicity scale (50, 51). Given that deaths also occurred in the solvent/vehicle controls, the percentage of deaths for each treatment was corrected using Abbott’s equation (52). For details, SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

M. Edwardsi Reproduction in Aquarium.

We set up a system of six tanks (with volumes ranging from 10 L to 30 L), connected to a 300-L sump (Fig. S1A). The sump was divided into chambers to allow the installation of different filter systems: synthetic sponges (mechanical/organic filter), protein skimmer, sintered glass cylinders (biological filter), and refugium containing a 20-cm sand layer (deep sand bed) on which a “carpet” of green algae was placed for nitrate absorption. An aquarium water chiller (Teco, TC10 water chiller) was also added to control the water temperature. Aquarium lighting (Odyssea, T5 T150 Aquarium Light) was mounted to control the photoperiod. In June (before the spawning period), 20 M. edwardsi colonies were collected at a depth of 6 m using scuba in the archipelago of Li Galli, and another sampling of 20 colonies was carried out at Secca di Vatolla (Fig. S1B). To prevent any damage to the tissues of alcyonaceans, the colonies were preferably detached by removing the substratum on which they were fixed. Specimens were placed in closed plastic bags and transported to the laboratory. The colonies were placed in the tanks maintaining a photoperiod of 14:10 (light:dark) and a temperature of 20 °C to 21 °C for the first month. The colonies were fed every 3 d, alternating live food (A. salina nauplii) and a mixture of freeze-dried food (squid and mussel) and Dupla Rin Coral Food powder. Photoperiod and temperature were modified monthly to follow the natural conditions. Spawning events and stages of larval development were recorded. Female colonies released eggs after 12 d from collection. Spawned eggs, white in color, remained attached to the surface of the colonies (surface brooding) for a few days (Fig. S2A). After 7 d to 10 d from spawning, fully developed swimming/crawling planulae were observed (Fig. S2B). When fully extended, the larvae reached a length of ∼1.5 mm. If disturbed, the planulae were able to contract, assuming a subspherical shape (Fig. S2C). After the spawning period, the eggs and planulae represented an easily accessible food source for specimens of T. striata. We directly observed the nudibranchs engulfing several whole planulae one after the other (Movie S5).

Chemical Study.

The extraction of frozen samples of M. edwardsi was carried out with acetone both by grinding and ultrasonic treatment to increase extraction efficiency. The diethyl ether soluble portion of the acetone extract was analyzed by TLC (n-hexane/diethyl ether in different ratios as eluent) by using Ehrlich's reagent to detect the spots. This analysis revealed the presence of Ehrlich positive spots at Rf 0.4 to 0.6, 100% n-hexane. The extract was fractionated on a silica gel column, eluting with a gradient of n-hexane/diethyl ether to isolate the whole fraction containing the Ehrlich positive spots. This fraction was further purified on AgNO3−silica gel column (n-hexane/diethyl ether gradient) to give purified compounds 1–3, identified by comparison of spectroscopic data with the literature (7, 10, 13).

TLC was performed on precoated silica gel plates (Merck Kieselgel 60 F254, 0.2 mm). Silica gel column chromatography was performed using Merck Kieselgel 60 powder (0.063 mm to 0.200 mm) treated with AgNO3. The NMR spectra were acquired in benzene-d6, and the chemical shifts were reported in parts per million referenced to benzene-d6 (δ 7.15 for proton and δ 128.0 for carbon), on a Bruker Avance-400 spectrometer using an inverse probe fitted with a gradient along the z axis, and on a DRX 600-MHz Bruker spectrometer equipped with a TXI CryoProbeTM. Optical rotation values were measured using a Jasco DIP 370 digital polarimeter.

Quantification of the Metabolites by GC-MS.

The wet weights of three individuals of T. striata and three small colonies of M. edwardsi were measured. The samples were subsequently frozen at −80 °C. Dimethylfumarate (Sigma Aldrich) (0.2 mg for T. striata and 0.4 mg for M. edwardsi) was added to frozen samples before extraction with acetone as an internal standard. The acetone extracts were concentrated and resuspended in 1 mL of n-hexane. GC-MS analyses were performed on an ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with EI source (70 eV) (Polaris Q; ThermoScientific) coupled with a GC system (GCQ; ThermoScientific) with a 5% phenyl column (Trace TR-5, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm; ThermoScientific) and using helium as a gas carrier. Elution of volatile sesquiterpenoids required a temperature program starting at 60 °C for 3 min, followed by a 4 °C min−1 gradient up to 165 °C, then 1 °C min−1 up to 180 °C, and, finally, 35 °C min−1 up to 310 °C, holding for 5 min. Samples were directly injected (2 µL) in split (1:10) mode, with a blink window of 3 min, inlet temperature of 210 °C, transfer line set at 250 °C, and ion source temperature of 230 °C. A calibration curve was prepared by using calibration points at 18.75, 37.5, 75, and 150 µg/mL of the natural (−)-atractylon (2). Mean concentrations from the three different samples (colonies/individuals) of each species ± SD were calculated.

Quantification of the Metabolites by 1H NMR.

The volumes of three individuals of T. striata and three small colonies of M. edwardsi were measured by displacement of the solvent and then directly extracted with benzene-d6 by using dimethylfumarate as an internal standard (0.5 mg). The benzene-d6 soluble part of all extracts was separated from the pellets by centrifugation (13,680 × g for 2 min) at room temperature, and the supernatant was subjected to 1H NMR quantification. The 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX 600-MHz spectrometer. The dimethylfumarate signals in the 1H NMR spectra of the crude extracts were used for integration to quantify metabolites 1–3 in comparison with their diagnostic signals, by using the Bruker software package (Bruker; BioSpin GmbH). The amount of the analyte of interest was calculated according to

| [S1] |

where Qx is the amount of the analyte in milligrams, Ix is the integral value for a single proton of the analyte, Istd is the integral value for a single proton of the internal standard, EWx is the equivalent weight of the compound (molecular weight), EWstd is the equivalent weight of the internal standard, and Qstd is the amount, in milligrams, of the internal standard. Natural volumetric concentrations were determined by dividing the calculated amount of a single compound by the respective tissue volume extracted (milligrams per milliliter). Mean concentrations from three different samples (colonies/individuals) of each species ± SD were calculated.

Food Preparation for the Assay with P. Elegans.

Food pellets were treated with the different compounds at concentrations ranging from 0 mg/mL (control food) to 3 mg/mL Individual compounds, dissolved in 0.5 mL of acetone, were added to a mixture of alginic acid (30 mg), ground freeze-dried squid mantle (50 mg), and purified sea sand (30 mg; granular size 0.1 mm to 0.3 mm). To minimize evaporation of volatile compounds 1–3, the solvent was then carefully removed under vacuum at low temperature. After evaporation of the solvent, one drop of food coloring (E124 and E110) and distilled water was added to give a final volume of 1 mL. Food coloring was added for easy detection of the ingested food in the digestive tract of the shrimp. The mixture was stirred, loaded into a 5-mL syringe, and extruded into 0.25 M calcium chloride solution for 2 min to harden. The resulting spaghetti-like red strand was cut into 10-mm-long pellets. Control foods were made in the same manner, with the addition of 0.5 mL of acetone but without the purified metabolites.

Food Preparation for the Assay with D. Rerio.

The artificial food for the zebrafish was prepared by using, as the main ingredient, the commercial pellets (granular food) to which fish were accustomed in captivity. The granular food (NOVO Bits; JBL) was ground into powder. The powder (50 mg) was then added to alginic acid (30 mg) and pure compound 3, dissolved in corn oil (100 μL). After mixing the mixture thoroughly with a spatula in a glass vial, one drop of food coloring (E124 and E110) and distilled water were added to give a final volume of 1 mL The mixture was extruded into 0.25 M calcium chloride solution to harden, finally obtaining pellets about 6 mm to 8 mm long. Control plain food was made in the same manner, with the addition of corn oil but without the purified metabolite 3.

Brine Shrimp Toxicity Assay.

The toxicity of compounds 1–3 was evaluated using the brine shrimp (A. salina) lethality test. The compounds were dissolved in DMSO and then serially diluted in artificial seawater to the desired concentrations (1, 5, 50, and 100 μg/mL). Dilutions were made in 24-well plates in triplicate for each concentration, taking into account that a further volume of seawater needed to be added subsequently together with the larvae to give a final volume of 2 mL. Further amounts of DMSO were added to the diluted solutions to ensure the presence of the same amount of vehicle (20 μL) in each well (1% solution). Brine shrimp eggs were hatched in artificial seawater (38 g/L) in a vessel. After a 24- to 28-h hatching period at room temperature, the nauplii were ready for the experiment. Ten nauplii in 100 μL of artificial seawater were added to each well, and incubated in the dark. After 24 h, the survivors were counted in each well under the microscope and recorded. Nauplii were considered dead if they did not exhibit any movement during 30 s of observation. Given that deaths also occurred in the solvent/vehicle controls, the percentage of deaths for each treatment was corrected using Abbott’s equation,

| [S2] |

where m is mean percentage of dead larvae in treated wells, M is mean percentage of dead larvae in solvent controls, and S is mean percentage of living larvae in solvent controls. The toxicity of each concentration was determined from the 50% lethality dose (LC50). The general toxicity activity was considered weak when the LC50 was between 500 and 1,000 μg/mL, moderate when the LC50 was between 100 and 500 μg/mL, and strong when the LC50 ranged from 0 to 100 μg/mL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the administrations of the Marine Protected Areas of Punta Campanella and Santa Maria di Castellabate (Italy) for allowing access, fieldwork, and sampling in the protected areas. We acknowledge D. Melck and V. Mirra for acquiring NMR data. C.Z. thanks the European Commission for a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship (CHIMICAMARINAANAPOLI–624519).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1614655114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Smith CUM. Biology of Sensory Systems. 2nd Ed Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerlach G, Atema J, Kingsford MJ, Black KP, Miller-Sims V. Smelling home can prevent dispersal of reef fish larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(3):858–863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606777104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brönmark C, Hansson LA. Chemical Ecology in Aquatic Systems. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mollo E, et al. Sensing marine biomolecules: Smell, taste, and the evolutionary transition from aquatic to terrestrial life. Front Chem. 2014;2:92. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bifulco G, Bruno I, Gomez Paloma L, Riccio R. Edwardsolides A, B and C. New sesquiterpenoid lactones from the Mediterranean octocoral Maasella edwardsi. Nat Prod Lett. 1993;3:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maggi F, et al. A forgotten vegetable (Smyrnium olusatrum L., Apiaceae) as a rich source of isofuranodiene. Food Chem. 2012;135(4):2852–2862. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavagnin M, Mollo E, Castelluccio F, Crispino A, Cimino G. Sesquiterpene metabolites of the Antarctic gorgonian Dasystenella acanthina. J Nat Prod. 2003;66(11):1517–1519. doi: 10.1021/np030201r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan WR, Tinto WF, Moore R. New germacrane derivatives from gorgonian octocorals of the genus Pseudopterogorgia. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:1499–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokke WCMC, et al. On the origin of terpenes in symbiotic associations between marine invertebrates and algae (zooxanthellae). Culture studies and an application of 13C/12C isotope ratio mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 1984;259(13):8168–8173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowden BF, Braekman J, Mitchell SJ. Studies of Australian soft corals. XX. A new sesquiterpene furan from soft corals of the family Xeniidae and an examination of Clavularia inflata from north Queensland waters. Aust J Chem. 1980;33:927–932. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapustina II, Kalinovskii AI, Grebnev BB, Savina AS, Stonik VA. Sesquiterpenoids from the far-eastern Gorgonaria Stenogorgia sp. Chem Nat Compd. 2009;45:916–917. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McPhail KL, Davies-Coleman MT, Starmer J. Sequestered chemistry of the Arminacean nudibranch Leminda millecra in Algoa Bay, South Africa. J Nat Prod. 2001;64(9):1183–1190. doi: 10.1021/np010085x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hikino H, Hikino Y, Yosioka I. Structure and autoxidation of atractylon. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1962;10:641–642. doi: 10.1248/cpb.10.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwasa M, Iwasaki T, Ono T, Miyazawa M. Chemical composition and major odor-active compounds of essential oil from PINELLIA TUBER (dried rhizome of Pinellia ternata) as crude drug. J Oleo Sci. 2014;63(2):127–135. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess13092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong Z, et al. Furanodiene, a natural product, inhibits breast cancer growth both in vitro and in vivo. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30(3):778–790. doi: 10.1159/000341457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong ZF, et al. Anti-angiogenic effect of furanodiene on HUVECs in vitro and on zebrafish in vivo. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;141(2):721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong Z, Tan W, Chen X, Wang Y. Furanodiene, a natural small molecule suppresses metastatic breast cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;737:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu WS, Dang YY, Chen XP, Lu JJ, Wang YT. Furanodiene presents synergistic anti-proliferative activity with paclitaxel via altering cell cycle and integrin signaling in 95-D lung cancer cells. Phytother Res. 2014;28(2):296–299. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buccioni M, et al. Antiproliferative evaluation of isofuranodiene on breast and prostate cancer cell lines. Sci World J. 2014;2014:264829. doi: 10.1155/2014/264829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ba Z, Zheng Y, Zhang H, Sun X, Lin D. Potential anti-cancer activity of furanodiene. Chin J Cancer Res. 2009;21:154–158. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, et al. Furanodiene blocks NF-kB-dependent MMP-9 and VEGF activation and inhibits cellular invasiveness and angiogenesis of breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Biomed Res. 2012;23:231–237. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong ZF, et al. Furanodiene enhances tamoxifen-induced growth inhibitory activity of ERa-positive breast cancer cells in a PPARγ independent manner. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(8):2643–2651. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolara P, et al. Analgesic effects of myrrh. Nature. 1996;379(6560):29. doi: 10.1038/379029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prieto JM, et al. Influence of traditional Chinese anti-inflammatory medicinal plants on leukocyte and platelet functions. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2003;55(9):1275–1282. doi: 10.1211/0022357021620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang CC, Chen LG, Yang LL. Cytotoxic activity of sesquiterpenoids from Atractylodes ovata on leukemia cell lines. Planta Med. 2002;68(3):204–208. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang KT, et al. Analysis of the sesquiterpenoids in processed Atractylodis Rhizoma. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2007;55(1):50–56. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HK, Yun YK, Ahn YJ. Toxicity of atractylon and atractylenolide III Identified in Atractylodes ovata rhizome to Dermatophagoides farinae and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55(15):6027–6031. doi: 10.1021/jf0708802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satoh K, Nagai F, Ushiyama K, Kano I. Specific inhibition of Na+,K(+)-ATPase activity by atractylon, a major component of byaku-jutsu, by interaction with enzyme in the E2 state. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51(3):339–343. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawlik JR, McFall G, Zea S. Does the odor from sponges of the genus Ircinia protect them from fish predators? J Chem Ecol. 2002;28(6):1103–1115. doi: 10.1023/a:1016221415028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritson-Williams R, Paul VJ. Marine benthic invertebrates use multimodal cues for defense against reef fish. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2007;340:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mollo E, et al. Factors promoting marine invasions: A chemoecological approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(12):4582–4586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709355105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carbone M, et al. Packaging and delivery of chemical weapons: A defensive trojan horse stratagem in chromodorid nudibranchs. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haber M, et al. Coloration and defense in the nudibranch gastropod Hypselodoris fontandraui. Biol Bull. 2010;218(2):181–188. doi: 10.1086/BBLv218n2p181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mudianta IW, et al. Chemoecological studies on marine natural products: Terpene chemistry from marine mollusks. Pure Appl Chem. 2014;86:995–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheney KL, et al. Choose your weaponry: Selective storage of a single toxic compound, latrunculin A, by closely related nudibranch molluscs. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0145134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wight K, Francis L, Eldridge D. Food aversion learning by the hermit crab Pagurus granosimanus. Biol Bull. 1990;178:205–209. doi: 10.2307/1541820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feld M, Dimant B, Delorenzi A, Coso O, Romano A. Phosphorylation of extra-nuclear ERK/MAPK is required for long-term memory consolidation in the crab Chasmagnathus. Behav Brain Res. 2005;158(2):251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorgeloos P, Remiche-Van Der Wielen C, Persoone G. The use of Artemia nauplii for toxicity tests—A critical analysis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1978;2(3-4):249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0147-6513(78)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ache BW, Young JM. Olfaction: Diverse species, conserved principles. Neuron. 2005;48(3):417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caprio J, Derby C. 2008. Aquatic animal models in the study of chemoreception. Olfaction & Taste, The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference, eds Firestein S, Beauchamp G (Academic, San Diego), Vol 4, pp 97−134.

- 41.Grode SH, Cardellina JH., II Sesquiterpenes from the sponge Dysidea etheria and the nudibranch Hypselodoris zebra. J Nat Prod. 1984;47:76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carté B, et al. Metabolites of the nudibranch Chromodoris funerea and the singlet oxygen oxidation products of furodysin and furodysinin. J Org Chem. 1986;51:3528–3532. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gohli J, Högstedt G. Explaining the evolution of warning coloration: Secreted secondary defence chemicals may facilitate the evolution of visual aposematic signals. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eisner T, Grant RP. Toxicity, odor aversion, and “olfactory aposematism.”. Science. 1981;213(4506):476. doi: 10.1126/science.7244647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lev-Yadun S. Defensive (Anti-Herbivory) Coloration in Land Plants. Springer; New York: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothschild M. Defensive odours and Müllerian mimicry among insects. Trans R Entomol Soc Lond. 1961;113:101–121. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niimura Y. Olfactory receptor multigene family in vertebrates: From the viewpoint of evolutionary genomics. Curr Genomics. 2012;13(2):103–114. doi: 10.2174/138920212799860706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. US EPA (2012) Estimation Programs Interface Suite™ for Microsoft® Windows (United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC), Version 4.11.

- 49.Janas U, Zarzycki T, Kozik P. Palaemon elegans—A new component of the Gulf of Gdańsk macrofauna. Oceanologia. 2004;46:143–146. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Padmaja R, et al. Brine shrimp lethality bioassay of selected Indian medicinal plants. Fitoterapia. 2002;73(6):508–510. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canales M, et al. Antimicrobial and general toxicity activities of Gymnosperma glutinosum: A comparative study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110(2):343–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abbott WS. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J Econ Entomol. 1925;18:265–267. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.