Significance

Molecular oxygen is an inert species, unable to enter chemical reactions. Activation occurs through the acceptance of an extra electron; this catalytic step plays a major role in applications such as heterogeneous catalysis and fuel cells. It is also used by all living organisms. We show that the two different charge states of O2 can be easily distinguished by atomic force microscopy (AFM). We directly injected or removed electrons into/from the O2 molecule by the AFM tip, switching the O2 reactivity. These results open new possibilities for studying catalytic and photocatalytic processes.

Keywords: TiO2, anatase, AFM, O2, adsorption

Abstract

Activation of molecular oxygen is a key step in converting fuels into energy, but there is precious little experimental insight into how the process proceeds at the atomic scale. Here, we show that a combined atomic force microscopy/scanning tunneling microscopy (AFM/STM) experiment can both distinguish neutral O2 molecules in the triplet state from negatively charged (O2)− radicals and charge and discharge the molecules at will. By measuring the chemical forces above the different species adsorbed on an anatase TiO2 surface, we show that the tip-generated (O2)− radicals are identical to those created when (i) an O2 molecule accepts an electron from a near-surface dopant or (ii) when a photo-generated electron is transferred following irradiation of the anatase sample with UV light. Kelvin probe spectroscopy measurements indicate that electron transfer between the TiO2 and the adsorbed molecules is governed by competition between electron affinity of the physisorbed (triplet) O2 and band bending induced by the (O2)− radicals. Temperature–programmed desorption and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy data provide information about thermal stability of the species, and confirm the chemical identification inferred from AFM/STM.

Neutral O2 molecules have a triplet spin configuration (1) and cannot form chemical bonds or enter chemical reactions with species in a singlet state (the vast majority of compounds). To become reactive, O2 molecules need to be excited to the singlet state. Because this state lies 0.98 eV higher in energy (2), excitation is inefficient at room temperature but occurs, e.g., in combustion. Alternatively, O2 can accept an electron. This process is not temperature-limited and is used by living organisms (via enzymes) (3, 4) and in technologies such as fuel cells and catalysis. Electron transfer into normally inert molecules (such as O2, CO2, or CH4) is a key step toward their activation (5), yet direct experimental insights into this process are scarce, and appropriate theoretical tools are just under development (6, 7).

In recent years, combined atomic force microscopy/scanning tunneling microscopy (AFM/STM) has emerged as a powerful technique for investigating and manipulating the charge state of atoms and molecules. Gross et al. (8) have shown that the charge state of single Au atoms can be determined from Kelvin spectroscopy, and that electrons can be deliberately injected and removed using the AFM/STM tip. Similar tip-induced charging/discharging processes have subsequently been demonstrated for other adsorbates, including organic molecules (9). In this work, we applied this approach to an anatase TiO2 (101) surface covered with small amounts of molecular O2.

A mixture of neutral and charged O2 molecules form upon adsorption. The charge of the latter originates from near-surface dopants, albeit the resulting (O2)− is not necessarily directly located directly above these dopants. The charged and uncharged molecules are clearly distinguished by their characteristic fingerprints in Kelvin probe spectroscopy. We directly measure chemical forces; the charged (O2)− readily forms a chemical bond with the AFM tip, whereas neutral O2 interacts only weakly. The charging of (O2)− can also be achieved by injection of electrons from the tip, or by exposing this model photocatalytic system (10) to UV light. The microscopy results are complemented by area-averaging spectroscopy data, which reveal that the neutral O2 species is present in the triplet state and desorbs at 64 K. Activated (O2)−, however, is chemisorbed and stable above room temperature. The band bending induced by the adsorbed (O2)− species is determined from core-level peak shifts in X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). We discuss our results with respect to previous work on the prototypical rutile TiO2 (110) surface (11–24).

Results

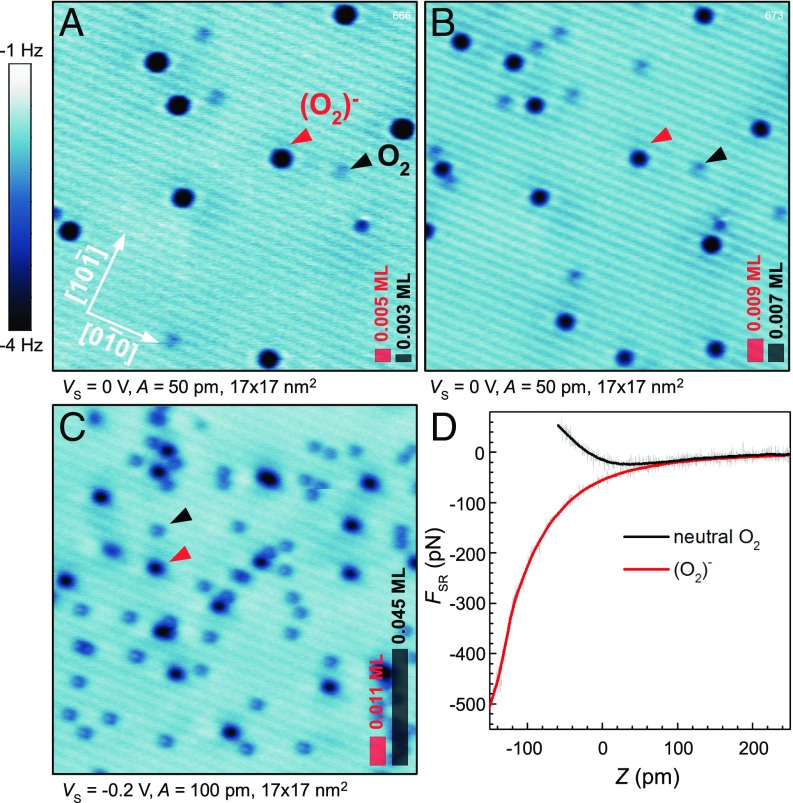

When an anatase (101) surface is exposed to molecular O2 at low temperature two types of adsorbates appear. Representative AFM images in Fig. 1 show faint, gray together with pronounced, dark spots; these are marked by black and red arrows, respectively. We will show that the faint spots are neutral O2 molecules, and the dark spots are molecules that have spontaneously accepted an electron from the substrate. Throughout this paper we refer to the latter species as (O2)− because our measurements are more consistent with the singly-charged (superoxo) than doubly charged (peroxo) state (25, 26). We note, however, that the experimental methods used here do not allow a precise quantification of the charge localized at a molecule. The (O2)− are dominant at low coverages (Fig. 1A), but their concentration saturates at 1 to 2% of a monolayer (ML). All further O2 molecules adsorb in neutral form (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of neutral and charged O2 molecules by AFM. (A–C) Constant-height AFM images of O2 adsorbed on the anatase (101) surface at = 5.5 K. The total O2 coverages are 0.008, 0.016, and 0.056 ML, respectively. Black arrows mark neutral O2 molecules, and red arrows mark negatively charged (O2)− species. Scale bars in the lower right corner reflect the concentration of the O2 and (O2)− in the imaged area. (D) Short-range chemical forces measured above the neutral and the charged O2 molecules.

The strong AFM contrast between the two species arises from their chemical reactivity. The (O2)− readily forms a chemical bond with the tip, whereas the neutral O2 is inert. Short-range chemical forces measured above these species are plotted in Fig. 1D. The maximum attractive force above the neutral O2 is of the order 20 pN, a weak interaction. The force measured above the (O2)− is more than an order of magnitude higher and can be classified as a chemical bond with the tip. With most tips the minimum of the attractive force above the (O2)− could not be reached because the molecule either dissociated or reacted with the tip.

All AFM images in this work are measured in the constant-height mode, where darker color reflects higher attractive force. This is necessary to avoid unintended interactions with the weakly adsorbed neutral O2 species, for example pulling it across the surface or picking it up with the tip. The contrast in AFM images is tip-dependent, and throughout this paper we present images acquired with reactive tips, likely Ti-terminated (27). Other tip terminations are discussed in Supporting Information (Fig. S1), along with AFM images of the clean anatase substrate (Fig. S2). The scale shown next to Fig. 1A is similar in all further AFM images in the main text. Precise scale bars are shown in Supporting Information.

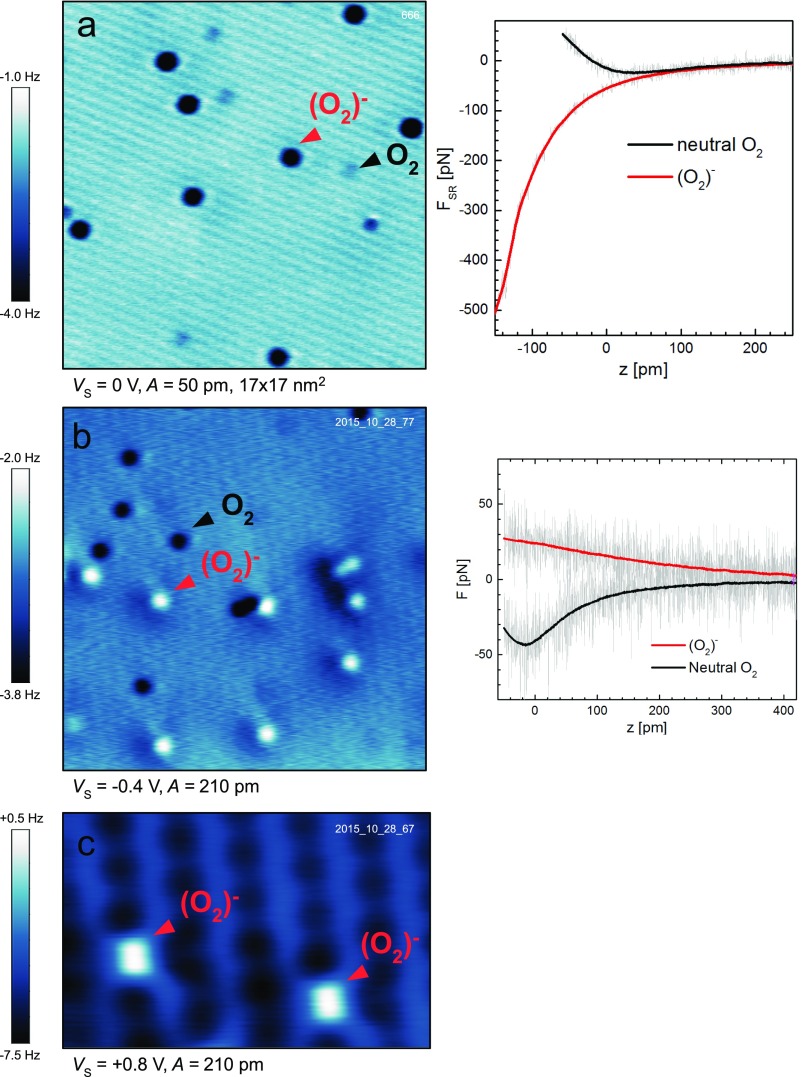

Fig. S1.

AFM contrasts obtained with different tip terminations, and corresponding short-range forces. (A) Reactive tip termination. (B) Tip terminated by an molecule. (C) Tip terminated by an O adatom. Different areas were imaged in each case.

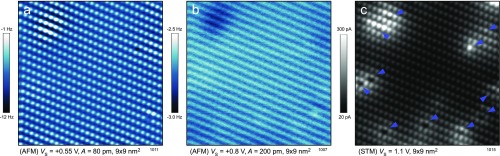

Fig. S2.

Combined STM/AFM imaging of the clean anatase (101) substrate. (A) A constant-height AFM image showing repulsion on the oxygen lattice. (B) The same area; the tip–sample distance is 280 pm larger than in A. (C) Constant-height STM image of the same area. The tip–sample distance is comparable to B. Blue arrows mark subsurface dopants.

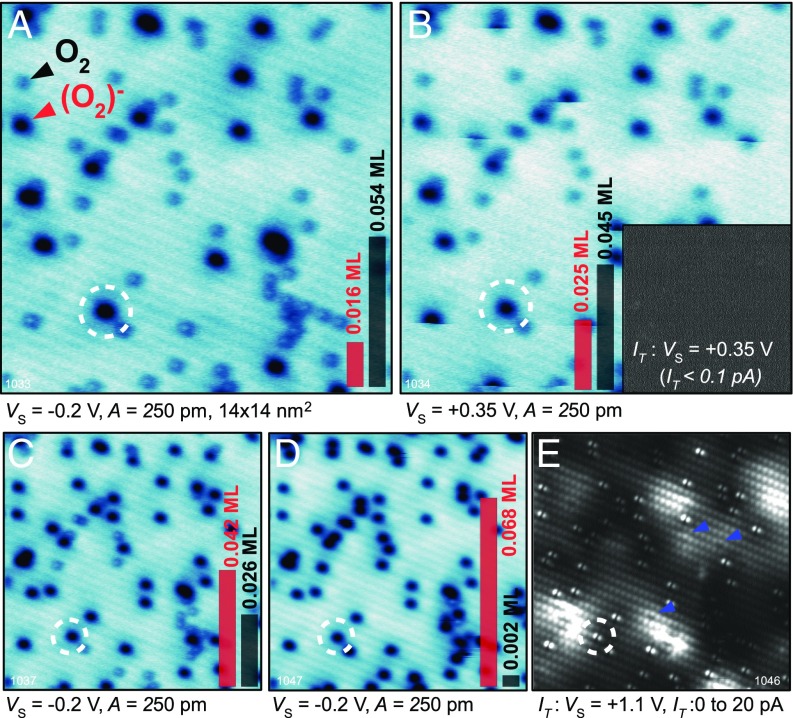

When imaging the surface it is important to avoid electron tunneling from the tip into the sample, because this results in charging the neutral O2. Therefore, all AFM images in Fig. 1 were acquired at either zero or slightly negative sample bias (i.e., at a located within the band gap of the -type semiconducting TiO2). The effect of tip-induced charging is shown in Fig. 2. Fig. 2A shows the anatase (101) surface after exposure to O2 at K. The same area was imaged in Fig. 2B but now a positive sample bias of +0.35 V was applied. The slow scanning direction is bottom-to-top and horizontal streaks in the image originate from tip-induced changes. Here the tip injects electrons into the neutral O2 molecules and converts them to (O2)−. The resulting (O2)− configuration is stable over the timescale of the experiment (many hours), even though the substrate is electrically conducting. A tunneling current image recorded simultaneously with Fig. 2B is shown in the inset. The tunneling current due to the charging of the neutral O2 was below the detection limit of 0.1 pA.

Fig. 2.

Injecting electrons into O2 by the STM tip. (A) AFM image of the anatase (101) surface after exposure to O2. Note that no electron injection occurs at a negative sample bias of = −0.2 V. (B) Scanning the same region at a positive sample bias of +0.35 V. (Inset) The simultaneously recorded tunneling current. (C and D) The same area following scans at = +0.44 V and +1.1 V, respectively. (E) Constant-height STM image of the same region. Blue arrows mark subsurface Nb+ dopants. Dashed circles mark the same position in all panels.

The maximum concentration of the (O2)− species that can be obtained by direct electron injection from the tip depends on the applied sample bias. This is shown in Fig. 2 C and D, where the same surface area is imaged after one scan at a bias of +0.44 and +1.1 V, respectively (an extended dataset is shown in Fig. S3). Fig. 2D shows that, after applying +1.1 V, almost all O2 molecules are charged. A constant-height STM image ( V) of the same region is presented in Fig. 2E. It shows the molecular orbitals of the (O2)− species as reported in a previous STM study (28), together with the signature of subsurface dopants (blue arrows). Based on our previous work, we attribute these dopant defects to Nb+ donors located in the first subsurface layer (28), because this model fits best with the observed surface chemistry (28, 29) and electronic structure (30) of the surface. When comparing the position of the originally charged (O2)− in Fig. 2A with the location of the dopants, it is obvious that the electron transfer into the O2 molecule is not limited to the defect site but readily occurs in defect-free regions as well. In our previous work, where oxygen dosing was performed at K, we found that all (O2)− adsorbed directly above the dopant site (28). We conclude that the activated (O2)− species diffuse toward the Nb+ dopants at elevated temperatures due to an electrostatic interaction.

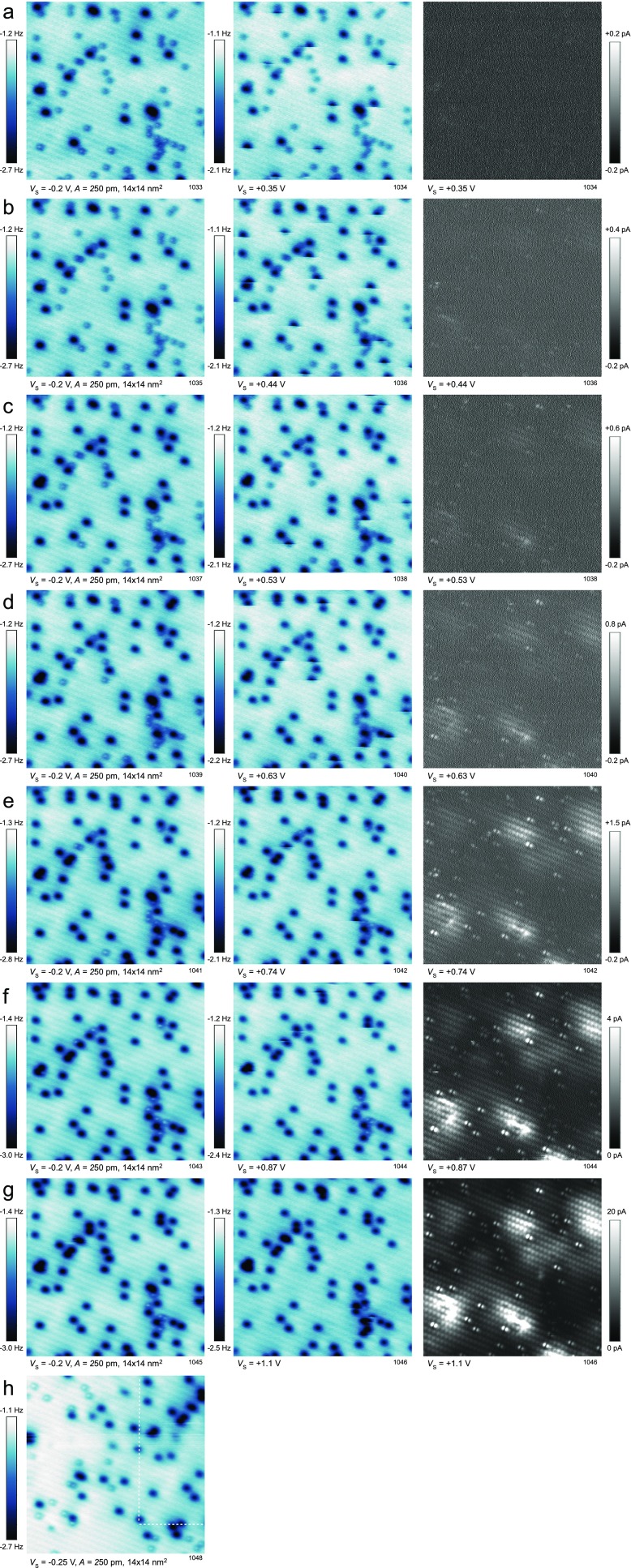

Fig. S3.

A full dataset of the experiment shown in Fig. 2. A surface with a mixture of neutral and charged was imaged with a sample bias increased step by step: (A) +0.35 V, (B) +0.44 V, (C) +0.53 V, (D) +0.63 V, (E) +0.74 V, (F) +0.87 V, and (G) +1.1 V. The left column shows the surface before the charging, the middle column is an AFM image obtained during the charging. The right column shows the tunneling current recorded simultaneously. (H) The scan area was partially moved out of the region shown in A–G; the previously scanned region is marked by the dashed line. The band bending and its lateral extension beyond the area of high-bias scanning are apparent in the image.

Temperature-Programmed Desorption and XPS.

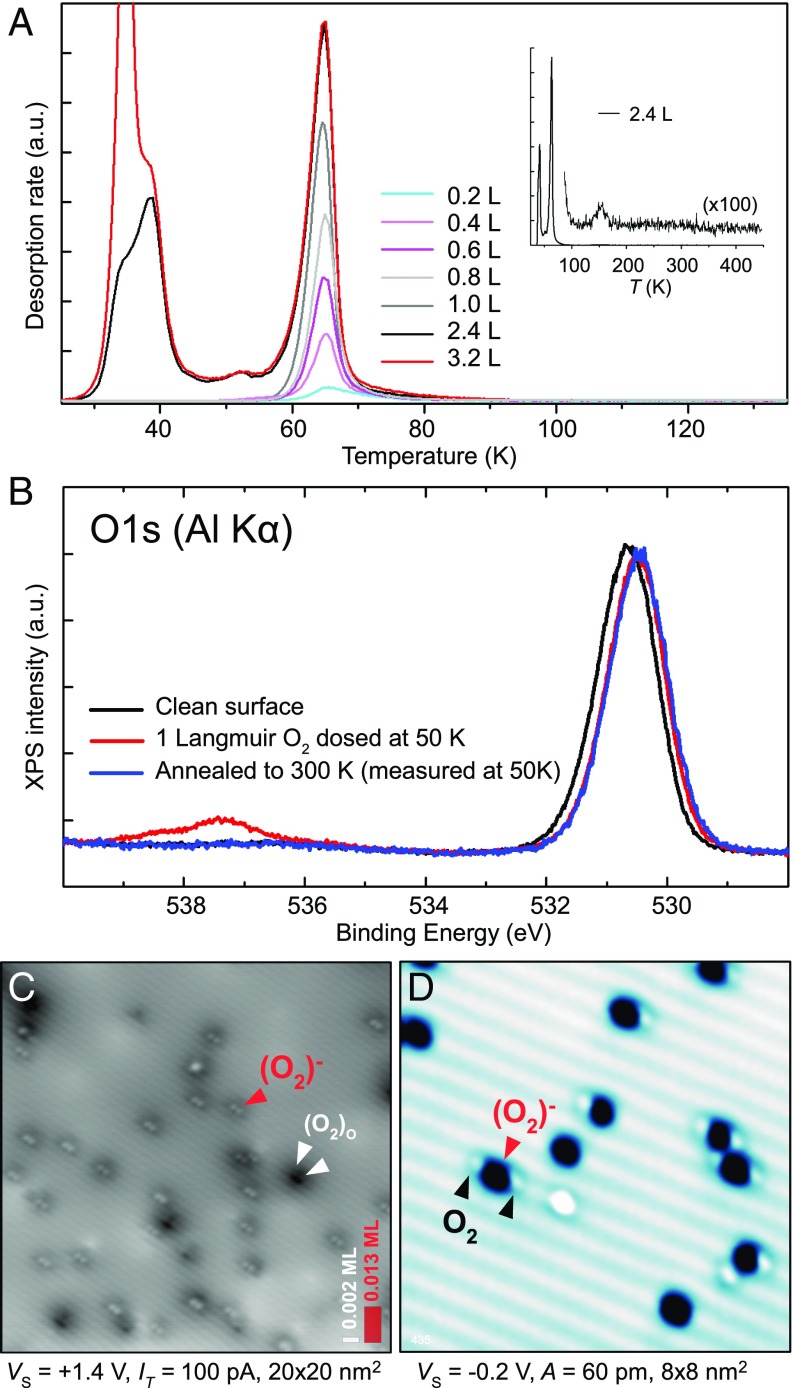

To assess thermal stability and charge state of the two O2 species we resort to area-averaging spectroscopies. Fig. 3A shows temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) spectra with increasing O2 exposure. The desorption peak at 64 K saturates at a coverage corresponding to a full monolayer, then a multilayer peak appears at 34 K. The monolayer peak shows first-order behavior with a desorption temperature corresponding to an adsorption energy of eV (assuming a prefactor of s−1). The only other desorption peak occurs at 150 K (Fig. 3A, Inset); it corresponds to just 0.003 ML O2. This peak might be related to O2 adsorbed at step sites (31).

Fig. 3.

Temperature-dependent behavior. (A) TPD spectra of O2 from the anatase (101) surface. (Inset) A larger temperature range. (B) XPS spectra of the O1s peak for a clean anatase (101) surface and after exposure to 1 Langmuir (L) of oxygen. (C) STM image of the anatase (101) surface after dosing 1 ML O2 at T < 15 K and subsequent annealing to room temperature. The red arrow marks an (O2)− molecule; the pair of white arrows mark a dissociated O2. (D) AFM image of the surface after dosing 0.04 ML O2 and annealing to 35 K. Neutral O2 diffused toward the (O2)−.

Whereas TPD suggests no O2 desorption above 150 K, STM imaging clearly shows that the (O2)− species are stable even above room temperature. Fig. 3C shows an STM image of the anatase surface following exposure to 1 L O2 at K, and subsequent annealing to 300 K. An (O2)− density of 0.013 ML is observed (red arrows), with the same STM appearance as the (O2)− in Fig. 2E. A few molecules dissociate at room temperature (marked by white arrows) and split into pairs of bridging oxygen dimers [referred to as (O2)O in previous work (28)]. It is interesting to note that the neutral O2 molecules can diffuse across the surface at temperatures above 25 K and are attracted to the (O2)− (Fig. 3D). Such clustering was also reported to occur in the gas phase (32).

XPS provides independent confirmation of the charge state of the adsorbed O2 species (Fig. 3B). The black curve in Fig. 3B shows XPS of the O1s state on the clean surface, with a peak at eV originating from lattice oxygen. Exposing the surface to 1 L O2 at 50 K (red curve) results in a new feature at 537.3 eV; this double peak is due to final state effects and a characteristic of physisorbed oxygen in the triplet state (33). In addition, the peak of the lattice oxygen shifts toward lower binding energies due to an upward band bending of 0.19 eV. Annealing the surface to room temperature (blue curve) results in desorption of the triplet O2 and the disappearance of the peak at 537.3 eV. The band bending remains, however, because it is induced by the 0.013 ML of chemisorbed (O2)− (estimated from Fig. 3C). The entire monolayer of triplet O2 therefore does not contribute to the band bending, which confirms their neutral charge state.

Kelvin Probe Spectroscopy and Charge Manipulation.

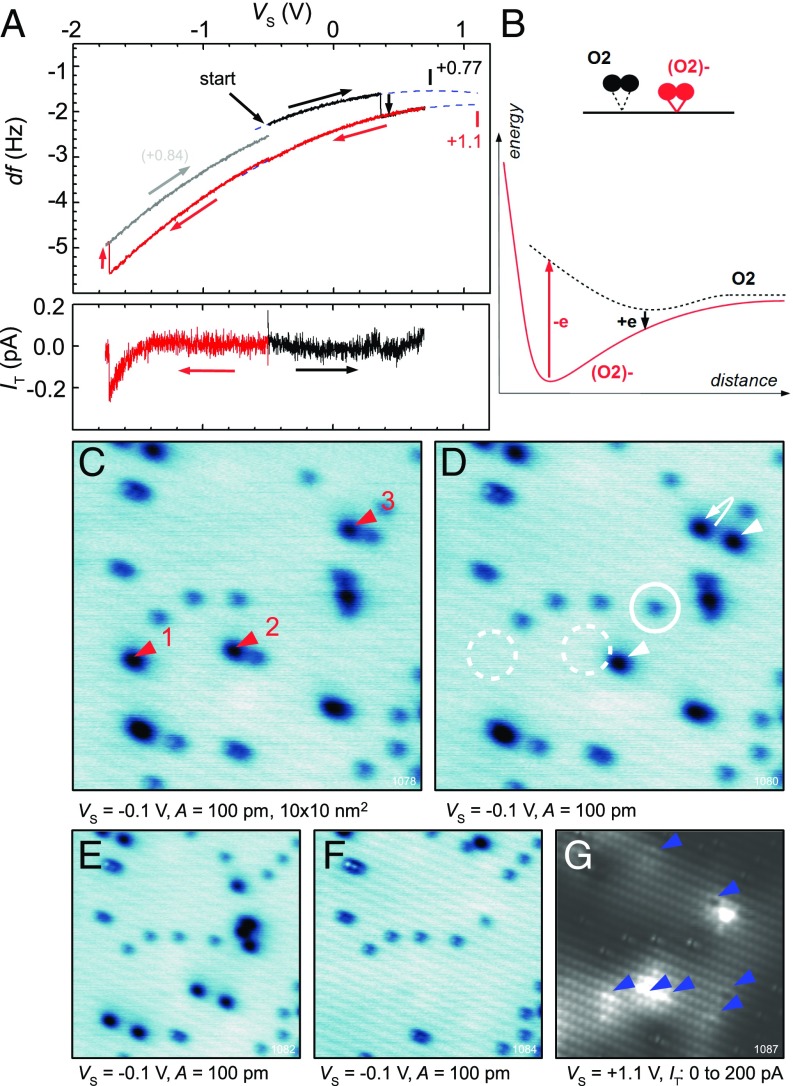

For a quantitative evaluation of charging the neutral O2, and the reverse process of removing an electron from the (O2)−, we used point Kelvin probe spectroscopy (34). We positioned the tip above a single, neutral O2 molecule and ramped up the , to switch its charge state to (O2)−. The corresponding Kelvin parabola is shown as the black curve in Fig. 4A. The step at V corresponds to the charging event, and a simultaneous jump to a different parabola with its maximum shifted toward a higher . Such a change in the local contact potential difference (LCPD) reflects upward band bending induced by negative charge localized at the molecule. The typical LCPD shift due to charging is 0.2 to 0.5 eV. The vertical jump in frequency shift (black curve in Fig. 4A) is induced by the chemical activation of the molecule; the attractive force is significantly higher after switching to the (O2)− state.

Fig. 4.

Point spectroscopy. (A) Kelvin parabolas showing charging and discharging an O2 molecule (Upper) and the simultaneously recorded tunneling current (Lower). (B) Schematic potential-energy curves for adsorbed O2 and (O2)−. (C) Surface with adsorbed O2; bias sweeps down to −1.8 V were applied above the marked molecules. (D) The same area afterward; see the text for a description of the changes. (E and F) The same area after applying further negative-bias sweeps above all (O2)−. (G) STM image of the same region as in F; blue arrows mark Nb+ dopants.

When ramping the down to negative values a discharging occurs typically at V (red curve). During this process molecules often move away, as discussed in the context of Fig. 4 C–F. They desorb, hop by several adsorption positions, or jump to the tip apex. We attribute this mobility to the sudden transition between the chemisorbed and physisorbed states, that is, a Newns–Anderson process (35) as sketched in Fig. 4B. The physisorbed molecule has a shallow potential minimum far from the surface, whereas the chemisorbed state has a much deeper minimum nearer to the surface. Electron removal from the (O2)− results in a neutral molecule too close to the surface, which is immediately and strongly repelled. We note that for all tip-induced charging and discharging events throughout this work we retracted the tip by z = +50 pm compared with normal imaging conditions. This reduces the probability of transferring the molecule to the tip apex. Further, we note that the (O2)− molecule used in Fig. 4A hopped by two lattice constants during the discharging process; the gray parabola is therefore still affected by this molecule.

Fig. 4 C–F focus on discharging the (O2)− and its consequent motion at the surface. The surface in Fig. 4C contains a mixture of O2 and (O2)−. Bias sweeps down to −1.8 V were applied above three (O2)− molecules (red arrows), and Fig. 4D shows the same region afterward. Molecules 1 and 2 have disappeared. During this process the substrate gains the excess electrons back, and this charge is accepted by other neutral molecules adsorbed nearby (white arrows). Molecule 3 moved by one adsorption site after the discharging, and one neighboring, neutral molecule has become charged. Finally, one new, neutral O2 has appeared in the region (marked by a circle), which is likely molecule 1 or 2.

The negative bias sweeps were applied above all (O2)− species in Fig. 4D, which resulted in further desorption and charge rearrangement in the area (see Fig. 4E). The same action was repeated once again, and the result is shown in Fig. 4F. Here the neutral O2 species do not spontaneously accept the electrons any further. We attribute it to the excess electrons being spatially confined around subsurface Nb+ dopants (30). The dopants (blue arrows) within the region are clearly visible in STM (Fig. 4G); spontaneous charging events in Fig. 4 C–F occurred exclusively in their vicinity.

The tunneling current was recorded simultaneously with the Kelvin parabola measurements (Fig. 4a, Lower). The charging is typically accompanied with a negligible tunneling current. Before the discharging event, however, we reproducibly detect a small current of the order 1 pA, which abruptly stops. We attribute this to a tunneling from an occupied orbital of the (O2)− molecule. The excess electron of the (O2)− therefore has an energy in the middle of the band gap and facilitates chemical bonding with the substrate. This bond is broken when the electron is removed.

Charge-Transfer Limitation.

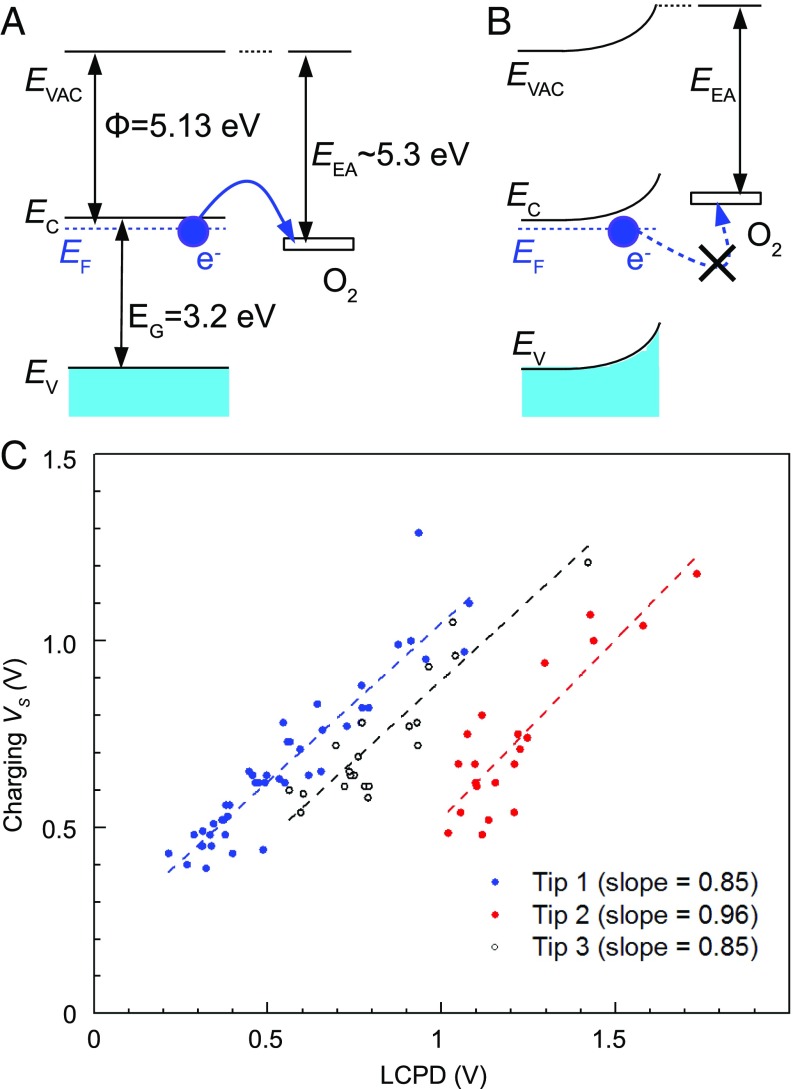

The concentration of intrinsic (O2)−, in the absence of tip-induced charging, is only 0.01 ML. Charge transfer between the substrate and adsorbed molecules is a decisive factor in catalytic processes such as the oxygen reduction reaction (38, 39), so it is worthwhile investigating why so few molecules become charged. In Fig. 5 we propose a simple model. For a clean surface (Fig. 5A), the adsorbed, neutral O2 molecule has its lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) state slightly below the anatase Fermi level (); spontaneous charging can occur. Formation of the first (O2)− species induces upward band bending, which shifts the LUMO of subsequently adsorbed, neutral O2 molecules above and prevents the charging of additional molecules.

Fig. 5.

Limitation to charge transfer. (A and B) Model of the electron transfer based on band bending. In A the O2 affinity level for accepting an electron lies below the Fermi level of anatase, and thus electron transfer is possible. In B adsorbed (O2)− induce upward band bending; the empty O2 level shifts above the anatase Fermi level and electron transfer to further neutral O2 molecules is blocked. Experimental values of the work function and the band gap Eg are adopted from refs. 36 and 37. (C) Measured relation between the LCPD and required for charging a molecule. For details see the text.

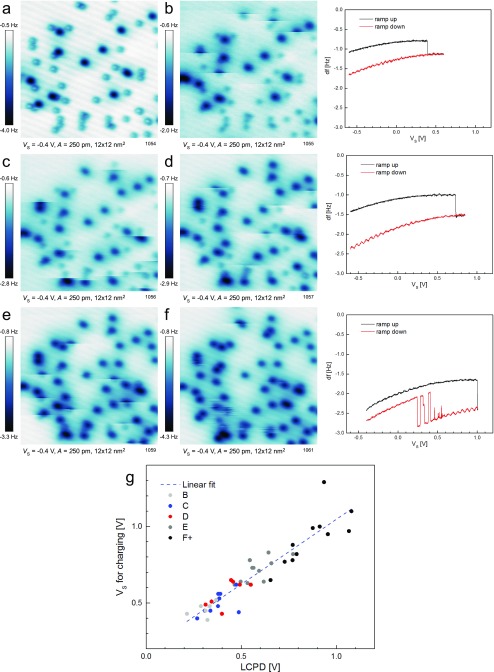

Despite this intrinsic limitation electrons can still be injected using the tip, but it is necessary to overcome the energy barrier due to built-up band bending by applying an increasingly positive sample bias . To test this model, we have investigated the tip-induced charging in detail. We selected an area with a relatively high concentration of adsorbed neutral O2 (such as in Fig. 2A). As the molecules were charged one by one we measured Kelvin parabolas above each of them, as in Fig. 4A. Fitting the parabola provides the LCPD, which is directly proportional to the band bending. For each parabola we can also determine the value of where the charging event occurs. There is clearly a linear correlation between these two quantities as plotted in Fig. 5C. In other words, the LCPD shifts to positive values with increasing (O2)− concentration (an indication of upward band bending). The bias necessary for charging the neutral molecules shifts in proportion. The experiment was repeated with three different tips (different colors in Fig. 5C); in all cases a linear correlation with a slope close to unity was observed. The offsets of the LCPD result from different tip work functions. The LCPD plotted on the x axis corresponds to the value before the charging event (i.e., the black parabola in Fig. 4A). A more detailed description of the experiment is given in the Fig. S4.

Fig. S4.

Detailed information about the experiment in Fig. 5. (A) A surface with O2 and . (B–F) The neutral molecules were charged by measuring point KPFM spectroscopy. Examples of Kelvin parabolas measured at low, medium, and high coverages are shown on the right side. (G) A plot of LCPD vs. for the charging. Points taken in B–E are distinguished by different colors. Black points (F+) were taken through several images, where F is a representative one. The concentration of is (A) 0.015 ML, (B) 0.023 ML, (C) 0.038 ML, (D) 0.052 ML, and (E) 0.071 ML (including the molecules charged in the specified image). (G) The correlation between the LCPD and the sample voltage required for charging a molecule.

From the band bending observed upon O2 adsorption (XPS data in Fig. 3) we deduce that the LUMO state of the neutral O2 is initially not more than 0.19 eV below the anatase EF. Assuming an anatase work function of 5.1 eV (36), this corresponds to an electron affinity of 5.1 to 5.3 eV (Fig. 5A). Considering that the triplet O2 is only physisorbed, its electron affinity is strikingly different from an O2 molecule in the gas phase, where the affinity is 0.45 eV (40). Upon approaching toward solid surfaces, molecular electron affinities are increased due to effects such the image charge (41), Madelung potential (42), surface electric dipoles, and quantum-mechanical interaction with the surface. Our results indicate that the electron affinity of the physisorbed molecule, and thus the exact physisorbed configuration, play a key role in the charge transfer.

UV Light.

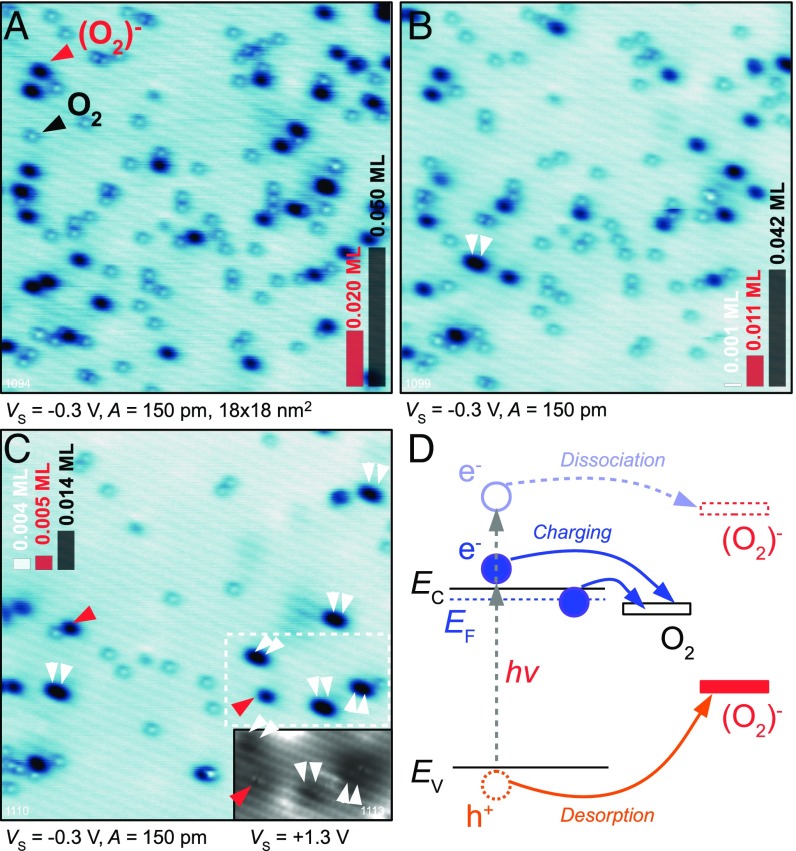

In this section we show that exposing the sample to UV irradiation induces dis/charging events identical to those achieved by STM/AFM manipulation. We started with an anatase (101) surface containing a mixture of O2 and (O2)− (Fig. 6A) and irradiated the sample for 10 min (T < 12 K). Fig. 6B shows the same area after the UV exposure, and Fig. 6C after an additional 80 min of UV light. The overall coverage decreases; the red and black bars in Fig. 6 A–C give the amount of charged and uncharged O2 molecules, respectively. In addition, some dissociation occurred (discussed below).

Fig. 6.

Illuminating the sample by UV light. (A) Anatase (101) surface with adsorbed O2. (B) The same region after exposing to UV light for 10 min. (C) The same region after another 80 min of UV illumination. (D) Schematic drawings of the processes occurring during the UV illumination.

A sketch of possible events is outlined in Fig. 6D. UV illumination introduces holes in the valence band and excess electrons in the conduction band. It is known (13, 20) that holes induce the desorption of (O2)−. This process is akin to removing the electron by the STM tip at negative biases. Neutral O2 molecules can accept electrons, either the ones photoexcited by the UV light or provided by dopants. The latter process becomes possible once the other (O2)− species are photodesorbed. Some dissociated O2 are highlighted by white arrows in Fig. 6C. These appear as a pair of adjacent, negatively charged species in AFM images. Using STM (dashed region and inset in Fig. 6C) we can clearly identify them based on our previous work (28, 43). Earlier (28) we found that the (O2)− species dissociate upon scanning at V; we thus attribute the photodissociation in Fig. 6C to hot electrons excited higher into the conduction band.

Discussion

We have observed that exposing the anatase (101) surface to molecular oxygen results in the activation of ML O2 and a concomitant upward band bending of 0.19 eV in the substrate. The amount of charged (i.e., activated) oxygen could be increased approximately by a factor of five via tip-induced electron injection, resulting in a band bending up to 0.9 eV (Fig. 5C). The adsorption of O2 has been studied in detail on the prototypical rutile (110) surface (11), and it is well accepted that an electron transfer is a prerequisite for O2 chemisorption. This was first proved by integral techniques, mainly a combination of TPD, photodesorption, and electron-stimulated desorption (12, 14–19). The excess electrons on the rutile (110) surface are mainly provided by surface oxygen vacancies (22, 23, 44), although subsurface Ti interstitials also play a role (21). The anatase (101) surface typically does not contain any oxygen vacancies (45, 46), and the electrons are provided solely by subsurface dopants. The substrate -type doping level then determines the concentration of adsorbed (O2)− species through band bending (47).

Although the integral methods clearly prove the presence of molecular O2 at the rutile (110) surface, STM studies have mainly focused on dissociated oxygen, that is, O adatoms (22, 23). The key problem in using STM for O2 adsorption is its sensitivity to injected electrons. We have shown that STM imaging converts neutral O2 molecules into (O2)−. The (O2)− species may be further dissociated by the tip; the exact conditions vary with the substrate (24, 28, 48). AFM can image all of the species with atomic resolution without the need of tunneling current, which makes this method an invaluable tool for studying systems sensitive to electron injection.

AFM experiments with molecule charging have previously been performed on insulating materials, typically NaCl thin films (8, 49, 50), which decouple the adsorbate from a metal substrate. Even though the anatase sample is electrically conducting, two stable charge states of O2 could be observed. This is due to the large hysteresis between the charging and discharging events (Fig. 4A), a special property of the O2 molecule. The charging/discharging is accompanied with a large structural relaxation, that is, a transition between the physisorbed and chemisorbed state (6, 25).

The tip-induced discharging is accompanied by a measurable tunneling current (Fig. 4A), which we explain in the following way. After removing the excess electron from the (O2)−, the molecule must relax away from the surface. The excess electron can be replenished from the conducting substrate during this period. The quantum efficiency of the tip-induced discharging is of the order ; this estimate comes from integrating the tunneling current under the red curve in Fig. 4A. The UV illumination in Fig. 6 has a comparable quantum efficiency, as estimated from the incident photon flux, illumination time, and number of photodesorption events. Comparable quantum efficiencies support the picture that the tip-induced and light-induced events have the same origin.

Conclusions

We have shown that AFM can resolve different chemical states of a single O2 molecule, as well as switch the chemical state by injecting or removing an electron. The tip-induced charging transitions are identical to those occurring when the surface is illuminated by UV light, or when electrons are spontaneously transferred from subsurface dopants. The methodology presented here opens a pathway for investigating and understanding key processes in photocatalysis, electrochemistry, or redox chemistry. Our results indicate that the physisorbed molecular state, in particular its electron affinity, plays a key role in the electron transfer. The concentration of activated (O2)− species is limited by a counteracting mechanism, which originates from band bending induced by electric charge localized at these species. The dopant (defect) sites have little direct influence on the charge transfer and only enter the process indirectly by providing the excess charge.

Materials and Methods

Combined STM/AFM measurements were performed at K in an ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) chamber with a base pressure below Pa, equipped with a commercial Omicron q-Plus LT head. O2 was dosed directly into the cryostat at K. Tuning-fork-based AFM sensors with a separate wire for the tunneling current were used (51) ( N/m, Hz, ). Electrochemically etched W tips were glued to the tuning fork and cleaned in situ by field emission and self-sputtering in Pa Ar (52). The reactive tip termination was reproducibly obtained by touching the anatase surface and applying a high tunneling current (53). The short-range chemical forces in Fig. 1D were determined by measuring curves above the O2 molecules, subtracting the long-range contribution (54) and converting the frequency shift to force (55). We used a single-crystalline mineral anatase TiO2 (101) sample, naturally doped by 1% Nb. The surface was prepared by ex situ cleaving and subsequent cleaning in vacuum by cycles of Ar+ sputtering (1 keV) and annealing to 950 K (56).

The TPD and XPS measurements were carried out in a UHV system with a base pressure of Pa. The anatase sample was mounted on a Ta back plate, cooled by a Janis ST-400 UHV liquid-He flow cryostat, and heated by direct current through the back plate. The temperature was measured by a K-type thermocouple spot-welded to the sample plate; the temperatures are accurate within ±3 K. O2 was dosed by an effusive molecular beam with a hat-shape profile (57). A linear temperature ramp of 1 K/s was used. A HIDEN quadrupole mass spectrometer in a line-of-sight configuration was used for detection of the TPD flux. The amount of dosed gases was calibrated according to the method described in ref. 58. One monolayer is defined as 1 molecule per surface 5-coordinated titanium atom and corresponds to an exposure of 1.6 Langmuir (L; 1 L = 1.33 Pas). The calibration includes a sticking coefficient of 0.9. Analysis of TPD spectra was done according to the procedure in ref. 59. XPS spectra were measured with a hemispherical electrostatic energy analyzer (SPECS Phoibos 150), using a monochromatized Al K X-ray source (SPECS Focus 500) at a sample temperature of K. XPS was measured under a 60∘ exit angle off normal. An Hg discharge lamp was used for illuminating the sample by UV light. The incident photon flux was cm−2s−1. UV illumination was introduced to the UHV chamber via a quartz window. The sample temperature during the illumination was below 12 K.

Different AFM Contrasts

Whereas STM imaging typically shows very little dependence on the tip termination, the influence of the tip termination is much stronger in AFM, where images are formed by short-range chemical forces. During the course of this work we encountered several reproducible AFM contrasts; these are summarized in Fig. S1.

Throughout the main text we used tips that gave the contrast shown in Fig. S1A. Here the negatively charged species are imaged as dark spots, as they form a chemical bond with the tip. The neutral interacts only interact weakly, albeit still attractively, with the tip, and neutral are imaged as faint, less dark spots. At closer tip–sample distances we can see repulsion above the neutral molecules; for an example see Fig. 3D. This contrast is achieved with the vast majority of tips. We prepare the tips by controlled touching the anatase surface, while applying a sample bias of ≈+5 V and using a high tunneling current (53). The tips are therefore TiOx-terminated; we assume that the attractive force is facilitated via a Ti atom at the tip apex.

The second type of contrast that is typically encountered is exemplified in Fig. S1B; we attribute this situation to an molecule located at the tip apex. It forms when neutral molecules are picked up while scanning with a reactive AFM tip. We assume that the molecule chemisorbs at the tip as . Such tips show attractive interaction toward the neutral and repulsion toward the . Both interactions are weak, in order of tens of piconewtons (Fig. S1B, Right). The maximum force measured above the neutral molecule is × stronger than in the previous case; we attribute this effect to the polarizability of the neutral . The stronger coupling between neutral and charged is also apparent for adsorbed species. As shown in Fig. 3D, upon annealing above 25 K diffusion of neutral becomes possible and these species are attracted toward the charged molecules.

The third, reproducible tip termination was achieved by dissociating an molecule and transferring a single O atom to the tip. This contrast was achieved rarely. Such tips allow imaging the in repulsion and directly show the adsorption configuration. By comparing with published DFT calculations of different terminations of oxide tips (27, 53, 60, 61) we tentatively attribute this tip to a termination by a single O adatom (i.e., single-coordinated O atom).

AFM Imaging of the Clean Anatase (101) Substrate

All AFM images in the main text were measured in the constant-height mode at a relatively large tip–sample distance. In this case, the contrast is formed by long-range forces, and the images show rows along the [010] direction (Fig. S2B). Here the dark rows correspond to rows of surface atoms, which protrude from the surface and provide a long-range contribution to the force.

Atomically resolved AFM imaging of the anatase substrate is strongly tip-dependent. Fig. S2 shows one specific contrast achieved with an O-terminated tip. The same area is shown in all panels of Fig. S2. Fig. S2A shows repulsion on the surface atoms and was acquired at a tip–sample distance 280 pm closer compared with Fig. S2B. This atomically resolved image conclusively shows that the surface does not contain a significant amount of oxygen vacancies (45).

Fig. S2C shows a constant-height STM image of the same area. The blue arrows mark subsurface dopants, which we attribute to donors.

Details of Tip-Induced Charging

To provide more insight into the process of electron injection into the neutral , we included more detailed data than presented in Figs. 2 and 5. Fig. S3 shows a full documentation of the experiment shown in Fig. 2. Here a region with a mixture of neutral and charged molecules was chosen (Fig. S3A, Left). This region was scanned with a positive bias (Fig. S3A, Middle). This bias was increased step by step, up to (Fig. S3G). The left column of Fig. S3 always shows a constant-height AFM image at (i.e., conditions that do not affect the adsorbed ). The middle column shows an AFM image measured at a positive sample bias (i.e., charging the neutral ). The right column shows the tunneling current recorded simultaneously.

In Fig. S3H we moved the scan region out of this area, left and down. Here we see the border between the region with all species charged (the region is marked by a dashed line) and the unperturbed region. The f-contrast above the bare surface illustrates the band bending and its characteristic range.

Fig. S4 provides additional documentation of the experiment shown in Fig. 5. Here we show a detail of the largest dataset. We chose an area with a mixture of and (Fig. S4A) and measured point Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) spectra above all neutral molecules in the region. The spectra were taken through several AFM images (Fig. S4 B–F), and we tried to keep the species homogeneously distributed through the image. This allows us to gain insights into the relation between the LCPD shift and the concentration. Fig. S4G shows the plot of LCPD vs. for charging—the same plot as the blue dataset in Fig. 5. Here the points are divided into five groups marked by different colors; the corresponding spectra were taken in the images in Fig. S4 B–F. Group F+ (black points) was taken through several images, where Fig. S4F is a representative one. The right column of Fig. S4 shows representative Kelvin parabolas measured at a very low concentration (Upper), medium concentration (Middle), and a very high concentration (Lower). The LCPD gradually shifts toward higher values, as well as the charging step in the parabola. When the local concentration is very high (the last parabola), the final state of the becomes unstable. This is apparent also in the AFM image (Fig. S4F), where certain regions appear fuzzy. This behavior appears when the concentration reaches approximately five times the initial concentration.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) advanced grant “Oxide Surfaces” (ERC-2011-ADG-20110209), by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project Wittgenstein Prize (Z 250), and FWF START Grant Y847-N20.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1618723114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hayyan M, Hashim MA, AlNashef IM. Superoxide ion: Generation and chemical implications. Chem Rev. 2016;116:3029–3085. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schweitzer C, Schmidt R. Physical mechanisms of generation and deactivation of singlet oxygen. Chem Rev. 2003;103:1685–1757. doi: 10.1021/cr010371d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bugg TH. Dioxygenase enzymes: Catalytic mechanisms and chemical models. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:7075–7101. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L. Dioxygen activation at mononuclear nonheme iron active sites: Enzymes, models, and intermediates. Chem Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freund HJ, Roberts MW. Surface chemistry of carbon dioxide. Surf Sci Rep. 1996;25:225–273. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libisch F, Huang C, Liao P, Pavone M, Carter EA. Origin of the energy barrier to chemical reactions of O2 on Al(111): Evidence for charge transfer, not spin selection. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109:198303. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.198303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann OT, Rinke P, Scheffler M, Heimel G. Integer versus fractional charge transfer at metal(/insulator)/organic interfaces: Cu(/NaCl)/TCNE. ACS Nano. 2015;9:5391–5404. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross L, Mohn F, Liljeroth P, Giessibl FJ, Meyer G. Measuring the charge state of an adatom with noncontact atomic force microscopy. Science. 2009;324:1428–1431. doi: 10.1126/science.1172273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steurer W, Fatayer S, Gross L, Meyer G. Probe-based measurement of lateral single-electron transfer between individual molecules. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8353. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linsebigler AL, Lu G, Yates JT. Photocatalysis on TiO2 surfaces: Principles, mechanisms, and selected results. Chem Rev. 1995;95:735–758. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dohnalek Z, Lyubinetsky I, Rousseau R. Thermally-driven processes on rutile TiO2 (110)-(1 1): A direct view at the atomic scale. Prog Surf Sci. 2010;85:161–205. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson MA, Epling WS, Perkins CL, Peden CHF, Diebold U. Interaction of molecular oxygen with the vacuum-annealed TiO2(110) surface: Molecular and dissociative channels. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:5328–5338. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson TL, Yates JT. Monitoring hole trapping in photoexcited TiO2(110) using a surface photoreaction. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:18230–18236. doi: 10.1021/jp0530451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimmel GA, Petrik N. Tetraoxygen on reduced TiO2(110): Oxygen adsorption and reactions with bridging oxygen vacancies. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:196102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.196102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrik NG, Kimmel GA. Photoinduced dissociation of O2 on rutile TiO2(110) J Phys Chem Lett. 2010;1:1758–1762. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrik NG, Kimmel G. Electron- and hole-mediated reactions in UV-irradiated O2 adsorbed on reduced rutile TiO2(110) J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:152–164. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z, Yates JT. Effect of adsorbed donor and acceptor molecules on electron stimulated desorption: O2/TiO2(110) J Phys Chem Lett. 2010;1:2185–2188. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson MA, Shen M, Wang ZT, Lyubinetsky I. Characterization of the active surface species responsible for UV-induced desorption of O2 from the rutile TiO2(110) surface. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117:5774–5784. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang ZT, Deskins NA, Lyubinetsky I. Direct imaging of site-specific photocatalytical reactions of O2 on TiO2(110) J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3:102–106. doi: 10.1021/jz2014055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson TL, Yates JT. Surface science studies of the photoactivation of TiO2 – New photochemical processes. Chem Rev. 2006;106:4428–4453. doi: 10.1021/cr050172k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wendt S, et al. The role of interstitial sites in the Ti3d defect state in the band gap of titania. Science. 2008;320:1755–1759. doi: 10.1126/science.1159846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lira E, et al. Dissociative and molecular oxygen chemisorption channels on reduced rutile TiO2(110): An STM and TPD study. Surf Sci. 2010;604:1945–1960. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lira E, et al. Effects of the crystal reduction state on the interaction of oxygen with rutile TiO2 (110) Catal Today. 2012;182:25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan S, et al. Molecular oxygen adsorption behaviors on the rutile TiO2(110)-11 surface: An in situ study with low-temperature scanning tunneling microscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2002–2009. doi: 10.1021/ja110375n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li YF, Aschauer U, Chen J, Selloni A. Adsorption and reactions of O2 on anatase TiO2. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:3361–3368. doi: 10.1021/ar400312t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li YF, Selloni A. Theoretical study of interfacial electron transfer from reduced anatase TiO2 (101) to adsorbed O2. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9195–9199. doi: 10.1021/ja404044t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yurtsever A, et al. Understanding image contrast formation in TiO2 with force spectroscopy. Phys Rev B. 2012;85:125416. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Setvin M, et al. Reaction of O2 with subsurface oxygen vacancies on TiO2 anatase (101) Science. 2013;341:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.1239879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setvin M, et al. A multitechnique study of CO adsorption on the TiO2 anatase (101) surface. J Phys Chem C. 2015;119:21044–21052. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Setvin M, et al. Direct view at excess electrons in TiO2 rutile and anatase. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;113:086402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.086402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Setvin M, et al. Charge trapping at the step edges of TiO2 anatase (101) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:4714–4716. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeLuca MJ, Han CC, Johnson MA. Photoabsorption of negative cluster ions near the electron detachment threshold: A study of the (O2n)− system. J Chem Phys. 1990;93:268. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puglia C, et al. Physisorbed, chemisorbed and dissociated O2 on Pt(111) studied by different core level spectroscopy methods. Surf Sci. 1995;342:119–133. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadewasser S, Glatzel T. Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy. Springer; Berlin: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newns DM. Self-consistent model of hydrogen chemisorption. Phys Rev. 1969;178:1123–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong G, et al. Photoemission electron microscopy of TiO2 anatase films embedded with rutile nanocrystals. Adv Func Mater. 2007;17:2133–2138. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scanlon DO, et al. Band alignment of rutile and anatase TiO2. Nat Mater. 2013;12:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nmat3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang B. Recent development of non-platinum catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. J Power Sources. 2005;152:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Setvin M, et al. Following the reduction of oxygen on TiO2 anatase (101) step by step. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:9565–9571. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sulka M, Pitonak M, Neogrady P, Urban M. Electron affinity of the O2 molecule: CCSD(T) calculations using the optimized virtual orbitals space approach. Int J Quant Chem. 2008;108:2159–2171. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundqvist BI, et al. Theoretical studies of molecular adsorption on metal surfaces. Int J Quant Chem. 1983;23:1083–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borisov AG, Sidis V. Theory of negative-ion conversion of neutral atoms in grazing scattering from alkali halide surfaces. Phys Rev B. 1997;56:10628–10643. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Setvin M, et al. Identification of adsorbed molecules via STM tip manipulation: CO, H2O, and O2 on TiO2 anatase(101) Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:21524–21530. doi: 10.1039/c4cp03212h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diebold U. The surface science of titanium dioxide. Surf Sci Rep. 2003;48:53–299. [Google Scholar]

- 45.He Y, Dulub O, Cheng HZ, Selloni A, Diebold U. Evidence of the predominance of the subsurface defects on reduced anatase TiO2(101) Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102:106105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.106105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scheiber P, et al. (Sub)Surface mobility of oxygen vacancies at the TiO2 anatase(101) surface. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109:136103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.136103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z, Yates JT. Band bending in semiconductors: Chemical and physical consequences at surfaces and interfaces. Chem Rev. 2012;112:5520–5551. doi: 10.1021/cr3000626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui Y, et al. Adsorption, activation, and dissociation of oxygen on doped oxides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:11385–11387. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steurer W, et al. Manipulation of the charge state of single Au atoms on insulating multilayer films. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114:036801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.036801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Repp J, et al. Charge-state-dependent diffusion of individual gold adatoms on ionic thin NaCl films. Phys Rev Lett. 2016;117:146102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.146102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giessibl FJ. 2012. Sensor for noncontact profiling of a surface. US Patent 2012/0131704 A1.

- 52.Setvin M, et al. Ultrasharp tungsten tips—Characterization and nondestructive cleaning. Ultramicroscopy. 2012;113:152–157. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stetsovych O, et al. Atomic species identification at the (101) anatase surface by simultaneous scanning tunnelling and atomic force microscopy. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7265. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lantz MA, et al. Quantitative measurement of short-range chemical bonding forces. Science. 2001;291:2580–2583. doi: 10.1126/science.1057824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sader JE, Jarvis SP. Accurate formulas for interaction force and energy in frequency modulation force spectroscopy. Appl Phys Lett. 2004;84:1801–1803. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Setvin M, et al. Surface preparation of TiO2 anatase (101): Pitfalls and how to avoid them. Surf Sci. 2014;626:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Halwidl D. Springer; Berlin: 2016. Development of an effusive molecular beam apparatus. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pavelec J, et al. A multi-technique study of CO2 adsorption on Fe3O4 magnetite. J Phys Chem C. 2017;146:014701. doi: 10.1063/1.4973241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tait SL, Dohnalek Z, Campbell CT, Kay BD. n-alkanes on MgO(100). I. Coverage-dependent desorption kinetics of n-butane. J Chem Phys. 2005;122:164707. doi: 10.1063/1.1883629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanchez-Sanchez C, et al. Understanding atomic-resolved STM images on TiO2(110)-(11) surface by DFT calculations. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:405702. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/40/405702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Enevoldsen GH, Glatzel T, Christensen MC, Lauritsen JV, Besenbacher F. Atomic scale kelvin probe force microscopy studies of the surface potential variations on the TiO2(110) surface. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:236104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.236104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]