Abstract

Purpose of review

The aim of the present review was to discuss the challenges around clinical decision-making for hospitalization of children with acute asthma exacerbations and the development, internal validation and future potential of the Asthma Prediction Rule (APR) to provide meaningful clinical decision-support that might decrease unnecessary hospitalizations.

Recent findings

The APR was developed and internally validated using predictor variables available before treatment in the ED, and performed well to predict need-for-hospitalization. Oxygen saturation on room air and expiratory phase prolongation were most strongly associated with need-for-hospitalization.

Summary

Research on prediction rules in pediatric asthma is rare. We developed and internally validated the APR using clinically intuitive predictor variables that are available at the bedside. Before incorporation in to electronic decision-support the APR must undergo external validation and an impact analysis to determine if use of this tool will change clinician behavior and improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: Asthma exacerbations, asthma hospitalization, clinical prediction rule, asthma prediction rule, clinical decision-support

INTRODUCTION

Asthma prevalence is among the most common and costly chronic diseases of U.S. children.[1, 2] Annual U.S. health care costs for asthma are $56 billion, with as much as 50% of directs costs attributable to hospitalizations.[3]

Acute asthma exacerbations are among the most frequent reasons for emergency department (ED) visits and are the most frequent reason for hospitalization of children in the U.S.[4–8] Acute exacerbations result in 640,000 ED visits yearly among children, and 24% of these visits result in hospitalization.[6] Of note, we have reported a similar rate of hospitalization (23%) in our population, but only 16.5% of those with exacerbations meet recognized need-for-hospitalization outcome criteria defined as either length-of-stay > 24 hours if admitted to hospital or relapse within 48 hours if discharged to home.[9–12]

Acute asthma exacerbations are variable in presentation and response to therapy, reflecting the heterogeneity of this complex genetic and environmental disease.[13] This heterogeneity may contribute to the difficulty ED clinicians face in deciding which children with exacerbations need to be hospitalized.[14–18*] Hospitalization decision-making may be challenging even for children with mild exacerbations; we have found that approximately 40% of asthma admissions from our children’s hospital ED do not meet the definition of need-for-hospitalization. Finally, we have demonstrated that most asthma hospitalization decisions can be made in the first 2 hours of ED care, yet this decision-making is prolonged, with median time to decision of 4.8 Hr. (SD 5.1 Hr.).[19]

The purpose of this review is to examine the literature pertaining to modeling and validating clinical prediction rules (CPRs). Further, we discuss how implementation of this decision-support instrument within computerized clinical decision-support (CDS) may decrease unnecessary asthma hospitalizations, thereby reducing the direct and indirect costs of hospitalization on patients, payers and providers.

DIAGNOSTIC UNCERTAINTY IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

Commercial aviation, an industry at the forefront of safety, recognized that the majority of adverse incidents involve human error. Further, no matter how careful and well-trained health care providers are, individuals will make mistakes both because they are human and because of systems problems predisposing to error.[20, 21]

The ED practice environment is characterized by several risk factors predictive of error. ED clinicians encounter undifferentiated problems of varying acuity and must deal with high decision density and cognitive loading. ED clinicians face varying levels of experience in their care team, frequent hand-offs of care, and numerous distractions and interruptions.[22] In the context of these practice environment risk factors, ED clinicians also often lack standardized tools for translating ever-changing best medical evidence into bedside decision making for potential complex and high-risk diseases.[20]

Without standardized decision support tools tailored to the practice environment, ED clinicians’ decisions are prone to cognitive errors, many of which stem from clinicians’ use of use heuristics, a strategy of problem solving in which clinical experience leads to cognitive short-cuts that include mnemonics, acronyms and other ‘rules of thumb.”[23, 24] Two strategies have been suggested to avoid the cognitive errors that occur when heuristics fail. The first, metacognition, is “a reflective approach to problem solving that involves stepping back from the immediate problem to examine and reflect on the thinking process.”[25] Cognitive forcing, the second strategy, “implies a deliberate, conscious selection of a particular strategy in a specific situation to optimize decision making and avoid error.”[23] Cognitive forcing strategies include tools such as CPRs to facilitate evidence-based clinical judgment through increasing the degree of specification and providing a rapid and accurate response to individual clinical problems.

ACUTE ASTHMA EXACERBATION SEVERITY SCORES

Among the numerous acute asthma severity scores proposed or in use, only two have been internally validated using an objective and accurate measure of airway obstruction such as FEV1 or airway resistance.[26,27,28] Inter-observer reliability has received little attention in the development of most scoring systems and scores have been largely comprised of subjective criteria.[29, 30] With these limitations in mind, a systematic review of asthma severity scores concluded that the predictive validity of existing bedside severity scores was inadequate to justify their use for the decision to admit or discharge a patient.[29]

In addition, severity scores have been validated using the hospitalization decision of the clinical team as a criterion measure. This may result in circular reasoning because the score components are used by clinicians to make hospitalization decisions, yet the hospitalization decision is used to ‘validate’ the score. [28, 31, 32] Biostatistical standards for prediction rule modeling and validation circumvent this limitation by masking individuals making clinical decisions from knowledge of the value of predictor variables used in prediction rule modeling. As a result, each patient’s outcome is determined without knowledge of the measured predictor variables.[33] These model building strategies are fundamental to CPRs but have not been incorporated into studies of bedside severity scores.[34*]

This principle is illustrated by the divergence of variables that remain in the reduced-form APR (discussed below) with those of the Acute Asthma Intensity Research Score (AAIRS, Table 1), a bedside severity score validated against %-predicted FEV1. Whereas bedside severity scores may assist the clinical team in calibrating treatment intensity to exacerbation severity, they may not be assumed to predict outcomes with the validity of the APR.

Table 1.

Acute Asthma Intensity Research Score (AAIRS) and Asthma Prediction Rule (APR) components

| Component | AAIRS Bedside severity score |

APR Clinical prediction rule |

|---|---|---|

| Age | − | + |

| Gender | ||

| Need for albuterol > 2/week | ||

| Air entry | + | − |

| Accessory muscle use | ||

| Wheezing | ||

| SpO2 on room air | + | + |

| Expiratory phase prolongation |

Abbreviations: AAIRS, Acute Asthma Intensity Research Score; APR, Asthma Prediction Rule; SpO2, oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry on room air.

CLINICAL PREDICTION RULES

A CPR is “a decision-making tool, which is derived from original research and incorporates three or more variables from the history, physical examination, or simple bedside tests.”[35, 36] A CPR is developed by applying statistical techniques to determine weighted combinations of predictor variables that categorize heterogeneous groups of patients into risk groups.[33,36,37**,38**] As such, CPRs assist clinicians in dealing with uncertainty in clinical decision making, as well as in predicting prognosis and enhancing the efficiency of resource utilization.[33, 39**]

CPRs are intended to augment rather than supplant clinician decision-making. They do not replace clinicians’ qualitative reasoning or dictate an evaluation or management algorithm.[33, 40*] Indeed, during the modeling and validation phase, CPRs must be compared to clinicians’ quantitative suspicion of the outcome of interest.[40]

A CPR can provide clinical decision-support to risk-stratify patients. Additionally, a CPR may identify patients for whom more resource-intensive interventions and the potential for adverse effects of these interventions may reasonably be avoided. In addition, clinicians are generally concerned more about a rule’s sensitivity than specificity because greater value is appropriately assigned to true-positive decisions to provide correct care when patients need it.[41*] Nonetheless, avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations for children with acute asthma exacerbations is important to improve resource utilization, for which high specificity and true-negative decisions are also desirable.

Significant contributions to the refinement of CPRs included clinical and biostatistical methodological standards for their development. Clinical standards were first enumerated by Wasson and colleagues.[35, 42] These include standards for derivation and validation as well as a four-level hierarchy of evidence (Tables 2 and 3) based upon the manner and extent of clinical validation to which a CPR has been subjected.[43] Optimally, CPRs achieve level one hierarchy and “can be used in a wide variety of settings with confidence that they can change clinician behavior and improve patient outcomes.”

Table 2.

Process of CPR Development1

| Steps in Development of a CPR |

|

|

| Step 1. Derivation: Identify factors with predictive power Step 2. Validation: a. Narrow validation: Apply the CPR in a clinical setting and population as in Step 1. b. Broad validation: Apply the CPR in multiple clinical setting with varying prevalence and spectrum of disease. Step 3. Impact Analysis: Provide evidence that the rule changes physician behavior and improves outcome and/or reduces costs. |

|

|

| Standards for Derivation of a CPR |

|

|

| 1. All important predictors are included in the derivation process. 2. All important predictors are present in a significant proportion of the study population. 3. All outcome events and predictors are clearly defined. 4. Those assessing the outcome event are blinded to the presence of the predictors and vice versa. 5. Sample size is adequate. 6. The CPR makes clinical sense (sensibility). |

|

|

| Standards for Validation of a CPR |

|

|

| 1. Subjects are chosen in an unbiased manner and represent a wide spectrum of disease severity. 2. There is a blinded assessment of the criterion standard for all subjects. 3. There is an explicit and accurate interpretation of the predictor variables and the CPR without knowledge of the outcome. 4. There is 100% follow up of enrolled subjects. |

Based on: McGinn TG et al.43

Table 3.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Clinical Prediction Rules

| Strength of Evidence | Evidence required |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Level 1: Rules that can be used in a wide variety of settings with confidence that they can change clinician behavior and improve patient outcomes | At least 1 prospective validation in a different population and 1 impact analysis, demonstrating change in clinician behavior with beneficial consequences |

| Level 2: Rules that can be used in various settings with confidence in their accuracy | Demonstrated accuracy in either 1 large prospective study including a broad spectrum of patients and clinicians or validated in several smaller settings that differ from one another |

|

| |

| Level 3: Rules that clinicians may consider using with caution and only if patients in the study are similar to those in the clinician’s clinical setting | Validated in only 1 narrow prospective sample |

| Level 4: Rules that need further evaluation before they can be applied clinically | Derived but not validated or validated only in split samples, large retrospective databases, or by statistical techniques |

Based on: McGinn TG et al.43

CPR DEVELOPMENT

Biostatistical standards for CPR development have been advanced by Harrell, Moons, and Steyerberg.[44, 45–51] Moons and colleagues recently summarized key principles and standards for CPR development, internal validation, implementation, impact analysis and external validation in a new setting.[37**, 39**, 52**, 53**, 54] Additionally, a recent advance is the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) standards.[34, 55, 56]

Predictive performance of CPRs is assessed using calibration and discrimination.[33, 44, 52**, 57] Calibration measures the accuracy of the predicted probability of the outcome provided by the model with the observed frequency of the outcome, assessed graphically using a plot of observed outcome frequencies against predicted outcome probabilities across a range of individual predicted risks. Discrimination is the ability of the model to distinguish between patients with different outcomes, quantified using the rank-order c-index that can assume values of 0 – 1, with a value of 1 indicating perfect discrimination.

Predictor variables for CPR modeling should be clearly defined, be clinically available, and enter the scoring system consistent with the manner in which each predictor becomes available in the clinical setting.[35, 46, 58] Stability and face validity are optimized by pre-selection of a limited set of candidate predictor variables based on clinical and biological plausibility.

The outcome to be predicted must be clinically relevant, important to stakeholders, and clearly defined.[35, 59] Identifying an outcome meeting these criteria may be challenging. For example, death from respiratory failure is clearly defined and of great concern but too infrequent to justify the expense of developing a CPR.[60]

With this in mind, an NIH expert panel convened to standardize asthma outcomes included hospitalizations on their list of recommended asthma-related healthcare outcome measures, with hospitalization for ≤ 23-hours be reported separately.[61] For stakeholders in broader clinical contexts (e.g., population health or preventive care) asthma-related hospitalizations have a universally negative value. However, for stakeholders relevant to the clinical context in which a CPR is implemented (i.e., patients presenting to the ED for an acute asthma exacerbation) hospitalizations may or may not indicate a worse outcome. Unnecessary hospital admission results in wasted resources, missed school/work and the risk of iatrogenic injury, whereas failure to admit when necessary results in delayed care and avoidable complications.

The other aforementioned criterion for a CPR outcome measure is that it is clearly defined. Most ED encounters result in one of two dispositions–discharge or hospitalization. In defining the correctness of ED discharge decisions, the most common measure is the absence of a return ED visit or other unscheduled visit (relapse) within 48 or 72 hours, although the construct validity of this measure is controversial.[20, 62–64] In defining the necessity of hospitalization, prior study has used the presence of medications or interventions that could not be provided in an outpatient context.[65] The medications or interventions available in an outpatient context vary widely, based on patient factors (e.g., access to care), hospital characteristics (e.g., asthma education provided) and community characteristics (e.g., air quality).[66–68]

Thus, we sought to define the necessity of an asthma hospitalization by length of stay (LOS), as it is easier to define clearly and uniformly than the presence of medications or interventions not available in an outpatient context. Asthma hospitalizations are typically brief, with mean length of stay (LOS) of 1.9 days in a national cohort of 44 children’s hospitals,[69] 3 days in New York State hospitals[12] and 2 days in 18 hospitals in King County, WA.[9] Moreover, 42% of the Washington children were hospitalized for only 1 day, and these children are likely those in whom the decision to admit to hospital is influenced by subjective and situational factors rather than medical indications for admission.[9] With these considerations in mind, LOS of greater than 24 hours or relapse within 48 hours was chosen as the outcome measure, need-for-hospitalization, for APR development.

CPR EXTERNAL VALIDATION AND IMPACT ANALYSIS

Before implementing a CPR in practice, it is necessary to externally validate the CPR in a new stream of patients in order to assess whether predictor variables perform as well in a new population as in the development population.[37**, 39**] Indeed, there has been a lack of external validation in published CPR studies.[54]

Additionally, an underlying assumption when a CPR is implemented in practice is that by accurately estimating the probability of the outcome of interest, clinicians’ decision-making and their patients’ outcomes will improve. This must be assessed by performing an impact analysis in which the effect of using the CPR on clinician behavior, clinical outcomes and/or cost of care is quantified. In contrast to external validation, this requires a comparative study, for example one in which clinicians are cluster randomized to receive CPR output or not.[38**] An additional feature of these studies is that they should incorporate clinicians’ input on the method of implementation.

Finally, a critical implementation feature is whether the CPR is directive or assistive for translating predictions into decisions.[41] A directive prediction rule explicitly recommends a specific decision, whereas an assistive prediction rule provides the probability of the outcome of interest without a specific recommendation. For some clinical encounters clinicians may prefer a directive rule that is based on a cut-point, for example the Ottawa Ankle Rule for obtaining x-rays.[70] However, hospitalization decision-making for pediatric acute asthma exacerbations is complex and includes consideration of the social situation, ability of the parent-child dyad to comply with outpatient treatment, and ability to return if necessary, in addition to the probability of need-for-hospitalization based on physiologic exacerbation severity. With this in mind, we believe that assistive APR implementation is most appropriate, in which the clinician will use the APR probability of need-for-hospitalization as one data point amongst others to be considered.

THE ROLE OF PREDICTION RULES IN CLINICAL DECISION-SUPPORT

The “Meaningful Use” incentive program as part of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) is intended to spur “significant improvements in care” through implementation of electronic health records.[71] The breadth of computerized decision support efforts to date in the EHR is beyond scope for this review, but it is important to highlight efforts in the domain of pediatric asthma. Prior asthma-related CDS includes aids for diagnosis of clinical deterioration through patient electronic self-report,[72] providing evidence based guidelines on asthma action plans at point of care,[73, 74] and asthma self-management applications built for mobile devices.[75] A Cochrane review of the latter category in 2013 demonstrated insufficient evidence regarding integration of mobile device-enabled asthma self-management applications into the clinical workflow.[75] Tools such as “asthma kiosks” to collect disease-specific data from parents during ED visits have been assessed with small effects on quality measures.[76]

The literature on CDS to impact decision-making on clinical disposition is less well-studied. It includes a randomized controlled trial by Dexheimer et al in which a probabilistic model intended to detect the diagnosis of an asthma exacerbation was evaluated in a trial in the context of an asthma management system in the EHR; the primary process measure of time to disposition decision was not significantly different between intervention and control arms of the trial.[77*] A number of predictive risk scores examining “need for hospitalization” have been validated in the literature but have not been implemented as CDS in a trial design to our knowledge.

THE ASTHMA PREDICTION RULE (APR)

The features of pediatric acute asthma exacerbations fulfill Stiell’s criteria for need of a CPR:[58]

The high prevalence of and expense to our health care system of acute asthma exacerbations;[3–8]

The existence of expert-panel guidelines for asthma that advocate assessment of signs, symptoms and functional tests of lung function that contrast with the limited availability of spirometry and other tests of lung function available to clinicians in acute care settings;[78]

The variation in practice and limited adherence to expert-panel guidelines;[79, 80]

The perspective of some clinicians that recommended diagnostic tests such as spirometry are unnecessary;[81, 82] and

That clinicians’ accuracy of exacerbation assessment is highly variable.[14, 83, 84]

Computerized clinical decision support (CDS) has been effective in providing clinician alerts for primary preventive care.[85] For example, a personalized chronic asthma management system reduced the rate of exacerbations among patients with poorly controlled asthma.[86] To our knowledge there have not been CPRs or CDS directed toward hospitalization decision-making for acute asthma exacerbations in pediatric patients.

An initial step in developing the APR was to identify candidate predictor variables suitable for inclusion in APR modeling.[87–90] We then developed the multivariable APR in a population of children with acute asthma exacerbations in accordance with clinical and biostatistical standards for CPR development.[19, 44, 49, 51, 57, 91] The full-model APR included 15 variables available at the time of triage (before treatment in the ED), and displayed high prognostic performance to predict need-for-hospitalization, measured using the widely accepted criterion measures calibration and discrimination.[46, 92] Calibration of the APR was high and discrimination good with c-index measured 0.74.

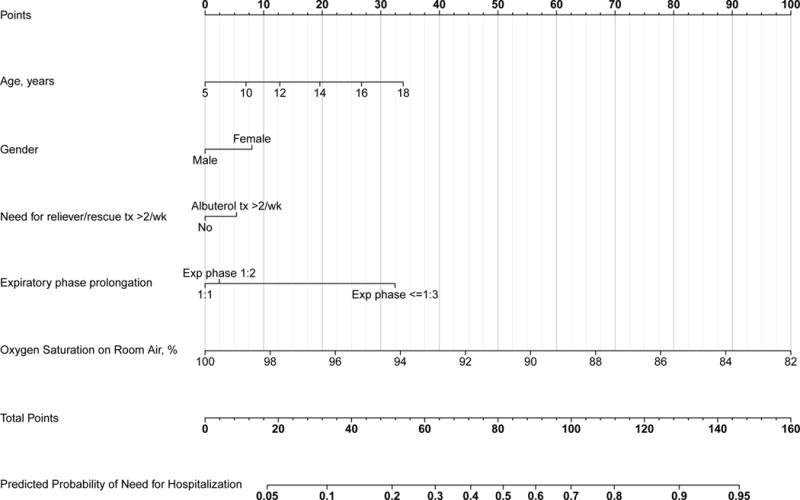

An APR with fewer variables and decreased complexity that can be incorporated within normal ED workflow will increase the uptake and usability of the prediction rule for clinicians.[37**] An APR developed in this way will be of use only if it performs comparably to the full-model APR. With these principles in mind, we modeled a reduced-form APR using backward step-down variable selection in accordance with biostatistical principles for CPR modeling.[11*, 57] The reduced-form model comprises 5 variables (Table 4) and displayed high calibration and discrimination (c-index 0.73). Of note, oxygen saturation on room air and expiratory phase prolongation were most strongly associated with need-for-hospitalization. A nomogram (Figure 1) may facilitate use of the APR at the bedside, and the underlying algebraic formula may be incorporated in to electronic decision-making tools.

Table 4.

Reduced-model Asthma Prediction Rule modeled in 928 patients aged 5–17 years with acute asthma exacerbations.

| Predictor variable | aOR (95%CI) for need-for-hospitalization |

|---|---|

| Age (change from 6.9 to 11 years) | 1.5 (1.0 – 2.1) |

| Female gender | 1.4 (1.0 – 2.1) |

| SpO2 (change from 98% to 94%) | 2.8 (2.1 – 3.6) |

| Need for albuterol > 2/week | 1.3 (0.9 – 1.9) |

| Inspiratory to Expiratory ratio (<=1:3 vs. 1:1) | 4.4 (2.3 – 8.6) |

Abbreviations: aOR (95%CI), adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval); SpO2, oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry on room air.

Adapted from Arnold et al.11

Figure 1.

Asthma Prediction Rule need-for-hospitalization reduced-form nomogram. For an individual patient, the points (top grid-line) for each predictor variable are assigned and the total points for all predictor variables are calculated. A vertical line from this value on the Total Points grid-line to the bottom-most grid provides probability of need-for-hospitalization.

Abbreviations: Exp, expiratory; Ins, inspiratory. Taken from (11).

FUTURE STEPS FOR THE APR: REDUCING ASTHMA HOSPITALIZATIONS

As noted, we have reported a rate of hospitalization (23%) in our investigation of children presenting to the ED with acute exacerbations, yet only 16.5% met recognized need-for-hospitalization outcome criteria defined as length-of-stay > 24 hours if admitted to hospital or relapse within 48 hours if discharged to home.[6, 9–12] We believe that the APR has potential to decrease unnecessary hospitalizations for asthma. Whether this can be accomplished effectively and safely will at least in part be determined by the manner of APR implementation.

As noted, a CPR may be implemented as an assistive or a directive decision-making tool. Although we believe an assistive approach is appropriate, we intend to obtain input from clinicians prior to a randomized trial to externally validate the APR and to measure impact on relevant outcomes. To assess whether APR implementation is safe will necessitate careful follow-up of parent-child dyads who are discharged to home after use of the APR.

A final consideration is whether to provide APR-calculated probability of need-for-hospitalization for all patients with exacerbations or to target the intervention to patients at greater risk of unnecessary hospitalization. With this in mind, patients who present to the ED with mild exacerbations are at greatest risk of unnecessary hospitalization and at least risk of an adverse outcome if discharged to home. Specifically, these patients are likely to return for care should the exacerbation not respond as expected or become more severe at home. Moreover, we have found that the rate of unnecessary hospitalizations is has high as 40% among patients with mild exacerbations.

CONCLUSION

Clinical prediction rules augment the judgment of clinicians, and this decision-support may facilitate improved care and resource utilization for common diseases for which there is unnecessary variability in assessment and treatment. The APR has been developed and internally validated using predictor variables that are clinically intuitive and available at the bedside before treatment. Before incorporation in to electronic decision-support the APR must undergo external validation and an impact analysis to determine if use of this decision-support will change clinician behavior and improve patient outcomes.

KEY POINTS.

Acute asthma exacerbations are the most frequent reason for hospitalization of children in the U.S.

Clinicians have limited decision-support tools to inform the decision whether to hospitalize a child with an exacerbation.

There is great variability in decision-making for treatment and hospitalization of children with exacerbations.

The Asthma Prediction Rule (APR) has the potential to provide clinical decision-support for asthma hospitalization and to improve resource utilization and decrease the burden of this disease on children and families.

External validation and an impact analysis are needed before incorporation of the APR into clinical decision-support.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt Emergency Department for their cooperation and assistance in the research discussed in this review.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

This research presented in this review was supported by the National Institutes of Health: [K23 HL80005] (Dr. Arnold); and NIH/NCRR [UL1 RR024975] (Vanderbilt CTSA).

Research support: This work was performed at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37232.

Abbreviations

- APR

Asthma Prediction Rule

- CDS

Computerized decision support

- CPR

Clinical Prediction Rule

- ED

Emergency department

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Soni A. Top Five Most Costly Conditions among Children, Ages 0–17, 2012 Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population. Statistical Brief #472April, 2015 October 14, 2015. Available from: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st472/stat472.shtml. [PubMed]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(5):483–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett SB, Nurmagambetov TA. Costs of asthma in the United States: 2002–2007. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011;127(1):145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, et al. Surveillance for asthma–United States, 1980–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newacheck PW, Halfon N. Prevalence, impact, and trends in childhood disability due to asthma. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2000;154(3):287–93. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. National health statistics reports. 2011;(32):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malveaux FJ. The state of childhood asthma: introduction. Pediatrics. 2009;123(Suppl 3):S129–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merrill C, Owens PL. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (US); 2006. Reasons for Being Admitted to the Hospital through the Emergency Department for Children and Adolescents, 2004: Statistical Brief #33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuels BN, Novack AH, Martin DP, et al. Comparison of length of stay for asthma by hospital type. Pediatrics. 1998;101(4):E13. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.4.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merenstein D, Egleston B, Diener-West M. Lengths of stay and costs associated with children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):839–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Moons KG, et al. Development and Internal Validation of a Pediatric Acute Asthma Prediction Rule for Hospitalization. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology In Practice. 2015;3(3):228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.09.017. Report of development and internal validation of the Asthma Prediction Rule. The report includes discussion of biostatistical and clinical standards for modeling and validation of clinical prediction rules. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang ZJ, LaFleur BJ, Chamberlain JM, et al. Inpatient childhood asthma treatment: relationship of hospital characteristics to length of stay and cost: analyses of New York State discharge data, 1995. ArchPediatr AdolescMed. 2002;156(1):67–72. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13*.Lemanske RF, Jr, Busse WW. Asthma: clinical expression and molecular mechanisms. JAllergy ClinImmunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.047. Discussion of the heterogeneity of clinical asthma phenotpyes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor MGAS, Saville BR, Hartert TV, Arnold DH. Pediatric Academic Societies. Washington, DC: May, 2013. Treatment Variability of Acute Asthma Exacerbations in a Pediatric Emergency Department with Defined Severity-Based Management Protocol. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emerman CL, Cydulka RK. Factors associated with relapse after emergency department treatment for acute asthma. AnnEmergMed. 1995;26(1):6–11. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ducharme FM, Kramer MS. Relapse following emergency treatment for acute asthma: can it be predicted or prevented? JClinEpidemiol. 1993;46(12):1395–402. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90139-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyle YM, Hynan LS, Gruchalla RS, et al. Predictors of short-term clinical response to acute asthma care in adults. IntJQualHealth Care. 2002;14(1):69–75. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/14.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Biagini Myers JM, Simmons JM, Kercsmar CM, et al. Heterogeneity in asthma care in a statewide collaborative: the Ohio Pediatric Asthma Repository. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):271–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2230. An examination of variability in asthma care at children’s hospitals using statewide repository data with notable differences in hospital practice, discharge criteria and length-of-stay. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Hartert TV. Spirometry and PRAM Severity Score Changes During Pediatric Acute Asthma Exacerbation Treatment in a Pediatric Emergency Department. The Journal of asthma : official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2012 doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.752503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenkel S. Promoting patient safety and preventing medical error in emergency departments. AcadEmergMed. 2000;7(11):1204–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IOM. Institute Of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. 2001 https://iom.nationalacademies.org/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf Landmark report on patient safety and medical care of common but sometimes critical illnesses. [PubMed]

- 22*.Croskerry P, Sinclair D. Emergency medicine: A practice prone to error? Cjem. 2001;3(4):271–6. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500005765. Croskerry’s report on cognitive biases, cognitive error and debiasing techniques to decrease medical error is notable. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Croskerry P. Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decisionmaking. Annals of emergency medicine. 2003;41(1):110–20. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.22. Croskerry’s report on debiasing techniques to decrease medical error is a notable contribution. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Croskerry P. Achieving quality in clinical decision making: cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2002;9(11):1184–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01574.x. Croskerry’s report on cognitive biases and debiasing strategies to decrease medical error is a notable contribution to the medical literature. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2003;78(8):775–80. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00003. Croskerry’s report on detecting and minimizing cognitive errors in a notable contribution. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chalut DS, Ducharme FM, Davis GM. The Preschool Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM): a responsive index of acute asthma severity. JPediatr. 2000;137(6):762–8. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.110121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Arnold DH, Saville BR, Wang W, et al. Performance of the Acute Asthma Intensity Research Score (AAIRS) for acute asthma research protocols. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2012;109(1):78–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.05.007. Performance evaluation of a comprehensive bedside acute asthma severity score validated against forced expiratory volume in 1-second and airway resistance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Arnold DH, O’Connor MG, Hartert TV. Acute Asthma Intensity Research Score: updated performance characteristics for prediction of hospitalization and lung function. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2015;115(1):69–70. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.03.020. Update of performance characteristics of the AAIRS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Windt DA, Nagelkerke AF, Bouter LM, et al. Clinical scores for acute asthma in pre-school children. A review of the literature. JClinEpidemiol. 1994;47(6):635–46. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor MG, Berg K, Stack LB, et al. Variability of the Acute Asthma Intensity Research Score in the pediatric emergency department. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2015;115(3):244–5. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ducharme FM, Chalut D, Plotnick L, et al. The Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure: A Valid Clinical Score for Assessing Acute Asthma Severity from Toddlers to Teenagers. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008;152(4):476–80.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorelick MH, Stevens MW, Schultz TR, et al. Performance of a novel clinical score, the Pediatric Asthma Severity Score (PASS), in the evaluation of acute asthma. AcadEmergMed. 2004;11(1):10–8. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2003.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moons KG, Kengne AP, Woodward M, et al. Risk prediction models: I. Development, internal validation, and assessing the incremental value of a new (bio)marker. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2012;98(9):683–90. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2015;68(2):134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.010. Report on development of standards for reporting prediction models. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laupacis A, Sekar N, Stiell IG. Clinical prediction rules. A review and suggested modifications of methodological standards. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277(6):488–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maguire JL, Kulik DM, Laupacis A, et al. Clinical prediction rules for children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e666–77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Moons KG, Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, et al. Prognosis and prognostic research: application and impact of prognostic models in clinical practice. Bmj. 2009;338:b606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b606. Moons and colleagues have contributed notably to the clinical and biostatistical standards for development, validation and implementation of clinical prediction rules. This begins a series of review articles from this group that are essential reading for those involved in development or implementation of clinical prediction rules. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38**.Moons KG, Kengne AP, Grobbee DE, et al. Risk prediction models: II. External validation, model updating, and impact assessment. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2012;98(9):691–8. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301247. A review of clinical prediction rule methodology that is essential reading for those involved in development or implementation of clinical prediction rules. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39**.Moons KG, Royston P, Vergouwe Y, et al. Prognosis and prognostic research: what, why, and how? Bmj. 2009;338:b375. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b375. This is one of a series of review articles from this group that are essential reading for those involved in development or implementation of clinical prediction rules. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Schriger DL, Newman DH. Medical decisionmaking: let’s not forget the physician. Annals of emergency medicine. 2012;59(3):219–20. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.08.015. Important discussion that development and implementation of clinical prediction rules must include clinicians’ insights and preferences. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41*.Reilly BM, Evans AT. Translating clinical research into clinical practice: impact of using prediction rules to make decisions. Annals of internal medicine. 2006;144(3):201–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00009. Nice review of clinical prediction rule implementation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wasson JH, Sox HC, Neff RK, et al. Clinical prediction rules. Applications and methodological standards. The New England journal of medicine. 1985;313(13):793–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509263131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGinn TG, Guyatt GH, Wyer PC, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXII: how to use articles about clinical decision rules. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(1):79–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Harrell F. Regression modeling strategies : with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. p. 568. Definitive text that comprises Dr. Harrell’s extensive work and prior reports in this area. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Califf RM, et al. Regression modelling strategies for improved prognostic prediction. Statistics in medicine. 1984;3(2):143–52. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Statistics in medicine. 1996;15(4):361–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Matchar DB, et al. Regression models for prognostic prediction: advantages, problems, and suggested solutions. Cancer treatment reports. 1985;69(10):1071–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrell FE, Jr, Shih YC. Using full probability models to compute probabilities of actual interest to decision makers. International journal of technology assessment in health care. 2001;17(1):17–26. doi: 10.1017/s0266462301104034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Harrell FE, Jr, et al. Prognostic modeling with logistic regression analysis: in search of a sensible strategy in small data sets. Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 2001;21(1):45–56. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJC, Harrell FE, et al. Prognostic modelling with logistic regression analysis: a comparison of selection and estimation methods in small data sets. Statistics in medicine. 2000;19(8):1059–79. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000430)19:8<1059::aid-sim412>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE, Jr, Borsboom GJ, et al. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2001;54(8):774–81. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52**.Royston P, Moons KG, Altman DG, et al. Prognosis and prognostic research: Developing a prognostic model. Bmj. 2009;338:b604. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b604. Moons and colleagues have contributed notably to the clinical and biostatistical standards for development; this is a concise review of prediction rule development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53**.Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P, et al. Prognosis and prognostic research: validating a prognostic model. Bmj. 2009;338:b605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b605. This is a concise review of prediction rule validation methodology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collins GS, de Groot JA, Dutton S, et al. External validation of multivariable prediction models: a systematic review of methodological conduct and reporting. BMC medical research methodology. 2014;14:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knottnerus JA, Tugwell P. The reporting of prediction rules must be more predictable. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2015;68(2):109–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bouwmeester W, Zuithoff NP, Mallett S, et al. Reporting and methods in clinical prediction research: a systematic review. PLoS medicine. 2012;9(5):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57*.Steyerberg EW. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Spproach to Development, Validation, and Updating. New York: Springer; 2009. p. 497. Definitive text on clinical prediction models. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stiell IG. The Development of Clinical Decision Rules for Injury Care Injury control: research and program evaluation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 217–35. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stiell IG, Wells GA. Methodologic standards for the development of clinical decision rules in emergency medicine. AnnEmergMed. 1999;33(4):437–47. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Abramo TJ, et al. The Acute Asthma Severity Assessment Protocol (AASAP) study: objectives and methods of a study to develop an acute asthma clinical prediction rule. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2012;29(6):444–50. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.110957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akinbami LJ, Sullivan SD, Campbell JD, et al. Asthma outcomes: healthcare utilization and costs. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2012;129(3 Suppl):S49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pham JC, Kirsch TD, Hill PM, et al. Seventy-two-hour returns may not be a good indicator of safety in the emergency department: a national study. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2011;18(4):390–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shy BD, Shapiro JS, Shearer PL, et al. A conceptual framework for improved analyses of 72-hour return cases. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2015;33(1):104–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rayner J, Trespalacios F, Machan J, et al. Continuous noninvasive measurement of pulsus paradoxus complements medical decision making in assessment of acute asthma severity. Chest. 2006;130(3):754–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chamberlain JM, Patel KM, Pollack MM, et al. Recalibration of the pediatric risk of admission score using a multi-institutional sample. Annals of emergency medicine. 2004;43(4):461–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flores G, Snowden-Bridon C, Torres S, et al. Urban minority children with asthma: substantial morbidity, compromised quality and access to specialists, and the importance of poverty and specialty care. J Asthma. 2009 May;46(4):392–8. doi: 10.1080/02770900802712971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boyd M, Lasserson TJ, McKean MC, et al. Interventions for educating children who are at risk of asthma-related emergency department attendance. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 2009;(2):CD001290. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001290.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grineski SE, Staniswalis JG, Peng Y, et al. Children’s asthma hospitalizations and relative risk due to nitrogen dioxide (NO2): effect modification by race, ethnicity, and insurance status. Environmental research. 2010;110(2):178–88. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shanley LA, Lin H, Flores G. Factors associated with length of stay for pediatric asthma hospitalizations. The Journal of asthma : official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2015;52(5):471–7. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.984843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, et al. Decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Refinement and prospective validation. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269(9):1127–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.269.9.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(6):501–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006114. Describes the history and significance of meaningful use of electronic health records. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Menezes J, Jr, Gusmao C. Development of a Mobile System Decision-support for Medical Diagnosis of Asthma in Primary Healthcare - InteliMED. Studies in health technology and informatics. 2015;216:959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuhn L, Reeves K, Taylor Y, et al. Planning for Action: The Impact of an Asthma Action Plan Decision Support Tool Integrated into an Electronic Health Record (EHR) at a Large Health Care System. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2015;28(3):382–93. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.03.140248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Licskai C, Sands TW, Ferrone M. Development and pilot testing of a mobile health solution for asthma self-management: asthma action plan smartphone application pilot study. Can Respir J. 2013 Jul-Aug;20(4):301–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/906710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marcano Belisario JS, Huckvale K, Greenfield G, et al. Smartphone and tablet self management apps for asthma. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 2013;11:CD010013. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010013.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Porter SC, Forbes P, Feldman HA, et al. Impact of patient-centered decision support on quality of asthma care in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e33–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77*.Dexheimer JW, Abramo TJ, Arnold DH, et al. Implementation and evaluation of an integrated computerized asthma management system in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. International journal of medical informatics. 2014;83(11):805–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.07.008. Innovative implementation of electronic asthma management system in a pediatric emergency department. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.National Heart L, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Shulruff R, et al. Self-reported physician practices for children with asthma: are national guidelines followed? Pediatrics. 2000;106(4 Suppl):886–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Powell CV, Kelly AM, Kerr D. Lack of agreement in classification of the severity of acute asthma between emergency physician assessment and classification using the National Asthma Council Australia guidelines (1998) Emergency medicine (Fremantle, WA) 2003;15(1):49–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2003.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Canny GJ, Reisman J, Healy R, et al. Acute asthma: observations regarding the management of a pediatric emergency room. Pediatrics. 1989;83(4):507–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Dowd LC, Fife D, Tenhave T, et al. Attitudes of physicians toward objective measures of airway function in asthma. The American journal of medicine. 2003;114(5):391–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spiteri MA, Cook DG, Clarke SW. Reliability of eliciting physical signs in examination of the chest. Lancet. 1988;1(8590):873–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Holleman DR, Jr, Simel DL. Does the clinical examination predict airflow limitation? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273(4):313–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roshanov PS, Misra S, Gerstein HC, et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for chronic disease management: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. Implementation science : IS. 2011;6:92. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tamblyn R, Ernst P, Winslade N, et al. Evaluating the impact of an integrated computer-based decision support with person-centered analytics for the management of asthma in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2015;22(4):773–83. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocu009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arnold D, Gebretsadik T, Minton P, et al. Clinical Measures Associated with FEV1 in persons with asthma requiring hospital admission. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Minton PA, et al. Assessment of severity measures for acute asthma outcomes: a first step in developing an asthma clinical prediction rule. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2008;26(4):473–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Minton PA, et al. Clinical measures associated with FEV1 in persons with asthma requiring hospital admission. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2007;25(4):425–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Sheller JR, et al. Accessory muscle use in pediatric patients with acute asthma exacerbations. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2011;106(4):344–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Moons KG, et al. Development and internal validation of a pediatric acute asthma prediction rule for hospitalization. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice. 2015;3(2):228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92*.Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA. Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Annals of internal medicine. 1999;130(6):515–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00016. Well-written and thoughtful discussion of performance measures and external validation for prognostic systems such as clinical prediction rules and the heirarchy of prediction rules based on these principles. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]